Abstract

African Americans are disproportionately affected by prostate cancer, yet less is known about the most salient psychosocial dimensions of quality of life. The purpose of this study was to explore the perceptions of African American prostate cancer survivors and their spouses of psychosocial issues related to quality of life. Twelve African American couples were recruited from a National Cancer Institute Comprehensive Cancer Center registry and a state-based non-profit organization to participate in individual interviews. The study was theoretically based on Ferrell's Quality of Life Conceptual Model. Common themes emerged regarding the psychosocial needs of African American couples. These themes were categorized into behavioral, social, psychological, and spiritual domains. Divergent perspectives were identified between male prostate cancer survivors and their female spouses. This study delineated unmet needs and areas for future in-depth investigations into psychosocial issues. The differing perspectives between patients and their spouses highlight the need for couple-centered interventions.

Keywords: Prostate cancer, Survivorship, Psychosocial factors, African Americans, Quality of life, Qualitative methods

Background

Nearly half of all male cancer survivors in the USA are prostate cancer survivors [1]. The approximate population of men alive today with a history of prostate cancer is 2.2 million [1]. This bourgeoning group of prostate cancer survivors is due in part to the increasing number of men diagnosed annually and the ever improving relative survival rates for prostate cancer [1, 2]. In the context of this emerging population of survivors, African Americans continue to experience higher morbidity and mortality rates from prostate cancer and lower survival rates when compared with men of other ethnic and racial groups [1, 2]. While the incidence and mortality rates for all cancers combined have decreased more among African American men than for any other racial or ethnic group, survival data from the SEER registry, stratified by race and ethnicity and adjusted by age and stage at diagnosis, showed poorer survival for African American (compared with Caucasian and Hispanic) males with prostate cancer [2]. This differential in outcome is likely due to a combination of factors such as stage presentation, tumor biology, and the impact of socio-cultural factors among African American men [2]. Recent research studies have begun to elucidate the role of socio-cultural factors (i.e., access to healthcare services, insurance coverage, lack of prostate cancer knowledge, low levels of awareness of prostate cancer screening, mistrust, fear, lack of cultural appropriate interventions, low health literacy, and inadequate patient–provider communication) in the context of health outcomes among minority populations, particularly African Americans [3–11]. It has been postulated that there is a complex interplay of these factors, ultimately contributing to adverse outcomes among African American prostate cancer patients.

Most men treated for prostate cancer encounter numerous challenges, including the possibility of recurrence/biochemical failure, functional impairments, and social constraints, all of which adversely impact quality of life (QOL) [12]. Commonly reported late and long-term treatment-related functional impairments include sexual dysfunction, incontinence, urinary irritation, fatigue, and bowel problems, all of which have been linked with increased morbidity and decreased QOL of the survivor [12, 13]. While the reporting of these effects are common, several studies have found significantly lower levels of functioning among African Americans when compared with white men [14–16]. After controlling for demographic factors, treatment type, comorbidities, and age, African Americans reported lower physical and emotional functioning [14–16]. Lower emotional functioning has been associated with embarrassment or shame often associated with urinary dysfunction that have been found to lead to a poor self-concept and lower sense of self-esteem among men [17]. Along with the emotional and physical challenges that accompany treatment, the high rates of permanent erectile, urinary, and bowel dysfunction can pose a significant challenge to men's psychosocial well-being [18]. Several studies have concluded that men who develop urinary or bowel-related problems after treatment for prostate cancer may respond by limiting their social activities, resulting in a restricted and isolated lifestyle [18, 19]. In view of this expanding body of literature, less is known about how African American prostate cancer survivors respond and cope with treatment-related physiologic and psychosocial outcomes [13].

As with most cancers, prostate cancer treatment not only impacts the survivor, but also the primary caregiver and family members. Several studies have noted the significant reciprocal relationship between the survivor and caregiver, where as much decreased physical well-being and emotional distress, such as anxiety or depression, is reported among caregivers as compared with survivors [20–22]. Emerging issues related to the survivor and caregivers' marital and social well-being include discussing the illness, sexual intimacy, and changing family roles and responsibilities [23]. These factors cumulatively impact the management of the treatment-related side effects of the patient and decrease the QOL of the caregiver, ultimately having an adverse effect on the marriage and relationships with family and friends [23].

While intervention research studies and clinical trials have attempted to address issues of treatment related side-effects and improve QOL for survivors [12, 17–19, 24–26], these studies have been characterized by one or more methodological limitations. The most often cited limitation is the non-representativeness of the study sample, therefore limiting the generalizability of the findings [27]. It also remains poorly understood if these interventions are able to adequately address the socio-cultural factors germane to African Americans that impact health outcomes [27]. Given the disproportionate impact of this disease on African Americans, it is important to improve upon and expand the current body of science to ensure interventions are developed to specifically address the most salient and unique issues of these survivors. The most common approach to examination of the QOL among prostate cancer survivors in general has primarily been relegated to addressing the physical side effects of prostate cancer treatment, such as incontinence, sexual dysfunction, and bowel problems [28–34]. Several studies have examined these issues in the context of spouses [35–45] but relatively very few have focused exclusively on African Americans and their spouses [27, 46–48].

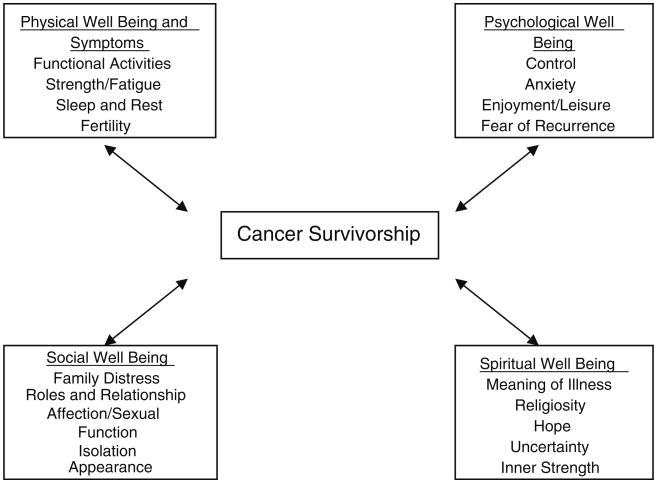

The QOL model for cancer survivors, developed by Ferrell (Fig. 1), posits that the concept of QOL is comprised of multiple domains of well being and the patient's perspective of QOL should be captured across each domain to ensure a proper assessment [49, 50]. The model consists of four domains of QOL: (1) physical well-being (e.g., functional ability, strength and fatigue, aches and pains, fertility, etc.); (2) social well-being (e.g., family distress, affection, sexual function, employment, finances, etc.); (3) psychological well-being (e.g., anxiety, depression, pain distress, fear of recurrence, control, etc.); and (4) spiritual well-being (e.g., meaning of illness, religiosity, hope, uncertainty, etc.) [49, 50]. Thus, the aim of this study was to expand the scientific paradigm of QOL to examine the role of socio-cultural factors on the psychosocial impact among African American prostate cancer survivors.

Fig. 1. QOL model.

Methods

Sample

African American prostate cancer survivors and their spouses were recruited through a purposive sampling strategy from the patient roster of the genitourinary clinic of a major cancer center and the client network of a statewide, nonprofit organization. Eligible study participants were contacted through an introductory letter sent via mail, provided an overview of the study and telephone number to receive additional information. Interested participants completed a pre-screening assessment to assess their eligibility. Inclusionary criteria included: (a) diagnosis and treatment for localized prostate cancer within the last 5 years and at least 1 year post-diagnosis; (b) between 40 and 70 years of age; (c) heterosexual married male; and (d) no diagnosis of recurrent prostate cancer or any other type of cancer. The final enrollment of couples in the study was based on the male participant meeting the inclusion criteria, as well as the willingness of his spouse to participate in the study. For participants and their spouses who expressed willingness to participate in the study, the couples were consented invited to participate in an, in-person interview at a location of their selection.

Design

Prior to initiation of the study, the protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the University of South Florida (IRB number: 105757). Following informed consent procedures, in-person, semi-structured individual interviews were conducted with African American prostate cancer survivors and their spouses at various community-based locations (i.e., Cancer Center, public libraries, and participant residence). The individual interviews with the couples were conducted concurrently and separately to prevent discussion of the interview purpose and content between couples and to improve the validity of the responses. In an effort to address cultural appropriateness and sensitivity during the data collection process, an African American interviewer conducted all interviews, with the assistance of an African American note-taker, both of whom were the same gender as the interviewees. The average length of the interviews was 1.5 h. Interviews were audio-recorded and professionally transcribed verbatim. At the completion of the interview, each interviewee was compensated for his or her time with a $25 gift card redeemable at a popular local discount store.

Instrumentation

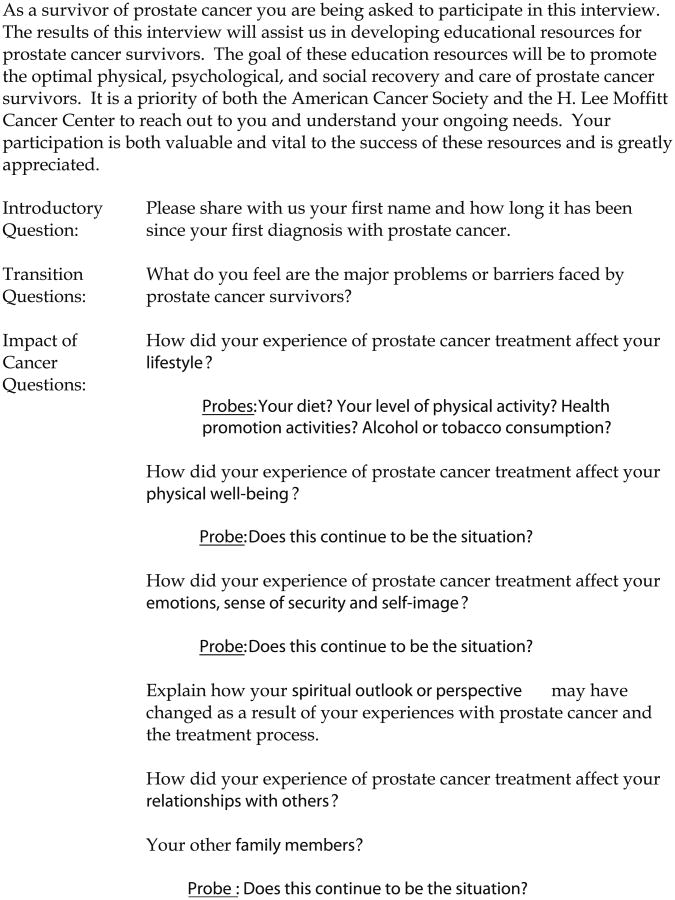

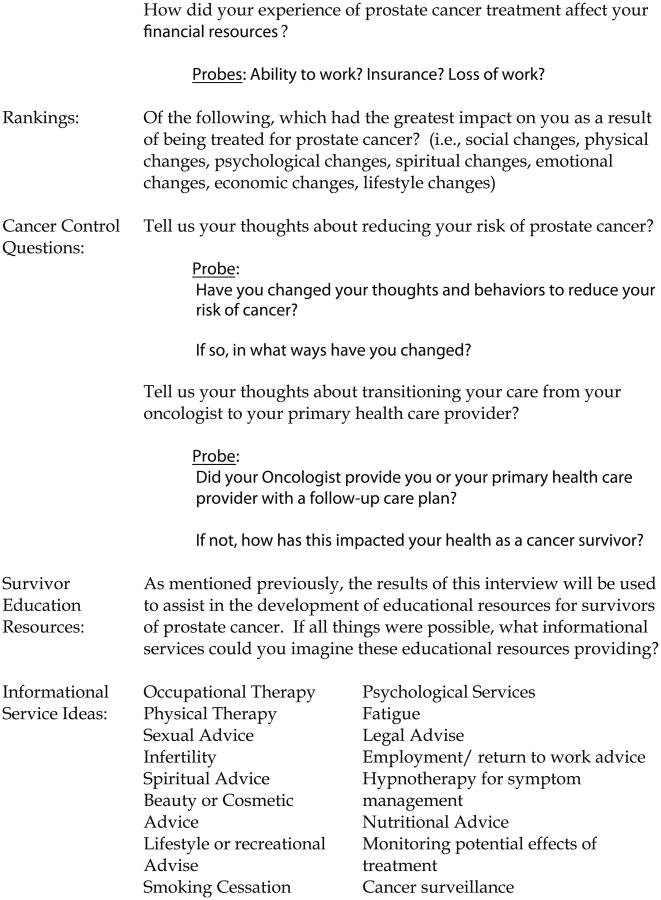

Separate interview guides were developed and utilized for the male and female interviews (Fig. 2). The interview guides were based on the domains of Ferrell's Conceptual Model of QOL [49, 50]. The interview guides were pilot tested with a convenience sample of four African American couples that had completed treatment for prostate cancer to establish content validity and readability. Based on data from the pilot test and additional feedback from medical content experts who were members of the research team, the qualitative interview guide was revised and modified by the study team.

Fig. 2. Semi-structured interview guide for prostate cancer survivor.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using a combination of content analysis and the constant comparison method [51–54]. A priori and emergent codes were used to develop the study codebook. The a priori codes were derived from the study research questions, which were based on existing literature, and emergent codes were added to the codebook as data analysis progressed. Four investigators within the study team formed two paired teams for transcript coding. Each member of a paired team of investigators individually coded each transcript, and the coding results were compared with ensure reliability. Where there were discrepancies between the coders, the PI repeated the analysis and any remaining discrepancies were resolved by discussions with the coding teams. Content analysis was conducted on the data to cull out those aspects most relevant to the research questions. All of the data were independently reviewed twice. During the initial coding pass, the entire text of a transcript was reviewed and hand coded using the initial codes, as well as making notes on possible new codes. After the first round of coding, discussions and notes were reviewed on probable new codes. After consensus was reached, a new codebook was created and coders independently reviewed the data and updated the code categories from the first coding pass. The second coding pass served to “clean up” the codes that were not anticipated in the first coding pass. ATLAS.ti (version 5.2) was used to manage and analyze the text produced during the interviews.

Results

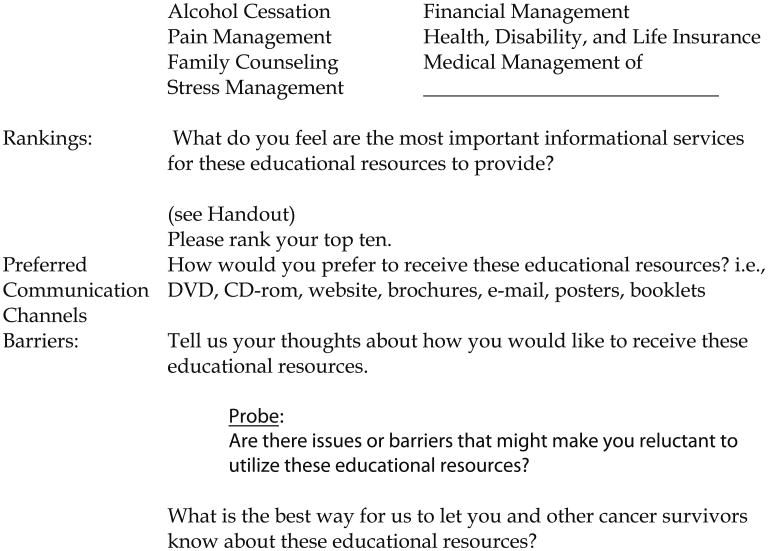

After initial contact and introduction to the study, 32 African American prostate cancer survivors expressed interest in participating and were subsequently screened to determine eligibility for the study. Of those screened, a total of 12 survivors met the eligibility criteria. The primary reasons for ineligibility included: (a) the survivor was over the age of 70; (b) the amount of time since diagnosis and treatment was beyond the study parameters; or (c) there was a change of spouse since the survivor's diagnosis and/or treatment. Male participants ranged in age from 51 to 70 years with a mean age 59.75 years. Among the 12 couples, surgery and radiation were the most common forms of treatment, with 33.3 % (4) reporting surgery, 42 % (5) reporting radiation therapy, and 25 % (3) reporting a combination of surgery and radiation therapy. Of the eight individuals who received radiation therapy, 88 % (7) reported having brachytherapy or seed implants [46]. Couples were married for as briefly as 5 years to as long as 46 years, and all couples had been married throughout prostate cancer diagnosis and treatment. In the following section, an overview of the survivors and their spouse's responses are reported in the context of the four domains of QOL: psychological, social, physical, and spiritual well-being (Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of study participants.

| Couple ID | Survivor's agea | Years since diagnosis | Type of treatment | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Surgery | Radiation | Chemotherapy | |||

| A | 52 | 2 | X | ||

| B | 51 | 4 | X | X | |

| C | 68 | 4 | X | ||

| D | 70 | 3 | X | X | |

| E | 65 | 2 | X | ||

| F | 69 | 5 | X | ||

| G | 67 | 3 | X | X | |

| H | 56 | 5 | X | ||

| I | 51 | 4 | X | ||

| J | 66 | 2 | X | ||

| K | 51 | 3 | X | ||

| L | 51 | 4 | X | X | |

All data are self-reported by the cancer survivor

The survivor's age is presented in years

Psychological Well-being: Fears

The most dominant theme in the domain of psychological functioning, which was expressed by approximately two thirds of the survivors and their spouses, was fears or concerns regarding the recurrence or metastasis of cancer. Several of the survivors and their spouses, mentioned that they worried that the cancer would “spread” or that they might develop cancer elsewhere in the body.

Spouse: “[We're afraid] that it will reoccur again because he's constantly sayin' that every time he go to the doctor, … he be a little upset; he doesn't know what they might tell him.”

Survivor: “… once I found out I had prostate cancer, you wonder is it gonna come back or is it gonna come up, you know, show up somewhere else, that's it.”

Participants, who reported experiencing fear of recurrence, also expressed increased anxiety and stress in the context of everyday functioning and within the context of their marriage. Fear of death was an additional dimension of fear commonly reported among both survivors and their spouses.

Survivor: “Well, it's a very hard road to travel; it's very difficult and when a doctor diagnoses you with cancer, you kinda feel scared, you know … you know, you feel like it's the end of your life, you know.”

Survivor: “I was always thinkin' about it as I'm drivin', as I'm sittin' here by myself, I would be thinkin' about it; wow man, you know, I might die tomorrow, you know, just…I mean, prostate cancer kinda slow anyway but I was thinkin' I'm gonna die tomorrow; that's what I'm initially thinkin' but I came to … back to reality.”

Spouse: “You tend to think death too; that's one of the things that you face that if you're married, you know, like with your mate, your husband, you think that you gonna lose him.”

Spouse: “Sometime I would not even let him see me cry because I know God will take care of me; you know what I'm sayin' I think it would destroy me if somethin' happened to him first.”

Spouse: “I was scared; I was nervous because to me, besides God, he's the best thing that ever happened to me. … and I don't want anything to happen to him.”

These dimensions of fear had far-reaching effects among the survivors, influencing their communication with their spouses and healthcare providers, decisions regarding treatment, emotional well-being, and spirituality. In response to these fears and concerns related to cancer fatalism and to maintain a measurable QOL post treatment, some couples became more determined to manage the discomfort of cancer treatment and take the necessary measures to enhance survival. Furthermore, success stories of others surviving cancer supported this resiliency in couples. Additionally, some participants discussed how stories from family members, friends, and co-workers about their experiences with cancer screening, diagnosis, and treatment incited fear but encouraged regular screening, which resulted in earlier diagnosis, and provided support during treatment.

Social Well-being: Marital Communication

Communication barriers were a recurrent psychosocial theme among both prostate cancer survivors, as well as their spouses. Among the survivors, the majority stated that discussions with their spouse about their feelings related to their cancer diagnosis and treatment were rare. Some survivors reported distancing themselves from their partner, which hindered communication.

Survivor: “Basic problem that arise from the prostate problems is you withdraw from the spouse; in other words, it's almost as though it's a epidemic that might be spreading on to them and they, you know, draw back a little, kinda wonder, you know, like it's always just hard as bein' a husband or a wife of a person and when you don't wanna do something or be around someone, you have that drawback.”

On the other hand, all of the spouses reported a desire to communicate with their husbands about their experiences. In spite of this, roughly two thirds of the spouses felt that their husbands were reluctant to discuss their cancer with them, and they did not want to force the conversation and possibly burden their husbands with more stress and anxiety.

Spouse: “I was stressed when I first … when he first got the diagnosis, yes, because at first he wouldn't talk about it.”

Spouse: “OK, my family normally, they try to be supportive because once … when he first got diagnosed, he didn't want me tell anybody; he wanted to keep it a secret until he could deal with it and then let everybody know so then I had to get him to realize that he needed more support so maybe keepin' it a secret wasn't a good thing, you know;”

Survivor: “Not right off; it's just a matter of being able to communicate, particularly with your wife, about it once you find out that you have the prostate cancer; it's not easy; I found it wasn't very easy for me to go home and discuss it with my wife but then I had to think about it, give it some thought, and once I did, I was able to do it.”

Spouse: “Like I said, my husband's very private with emotional things and I think he just feels like if I keep it inside, I can handle it and I think basically, that's how he did it when he had heart trouble, his daughter was here to support him but I don't think this was something that he discussed with ‘em.”

However, some of the survivors reported that the communication with their spouse had remained consistent and, in some cases, improved. Additionally, some discussed how they worked to improve the lines of communication with their wives.

Spouse: “And, in our case, a lotta times, I do more understandin' than my husband so a lotta times he has me with him cause I can understand it when you sayin' somethin'; he's still like what did they say and I know how to break the questions down and stuff like that so … It's always helpful where everybody take you through those different transitions that you have to go through.”

While general communication between the survivors and spouses was often reported as deficient, conversations related to sexual functioning were almost nonexistent. Although this was a significant issue mentioned separately in almost all interviews, only a few prostate cancer survivors reported discussing either the possibility of loss of sexual functioning or the actual loss of sexual functioning with their wives. However, few of the spouses reported conversations about sexual functioning. Although the spouses were aware of changes in sexual functioning in their husbands, they reported that they were generally unaware of how their husband's really felt about the situation and did not feel comfortable broaching the subject.

Spouse: “He'll say well, we need to sit down and talk but he doesn't really; he wants to sit down and talk about things that's projected for him but when it comes to that, he never really sat down and said well, sit down; let me tell ya what's goin' on with me; this is gonna happen and I know I can't perform so I'm gonna try this and they gonna send me to this doctor and I got this kinda stuff; let me try this. All of a sudden, he's got things you see around the house which he never told you why they're there., who gave it to ya, who gave ‘em to you when he got the prescription and let me try, you know, that kinda stuff so never but he'll swear well, I told you about this so, you know.”

Spouse: “He tries so hard to make me happy and he know … I think he know sometime he fails but, you know, I say nothin' about it; you know, I go ok, you know, and then sometime, he can't do nothin' at all and then when he do, like it don't last.”

Social Well-being: Social Support

Support during the diagnosis and treatment phase of the prostate cancer experience came from a variety of sources outside the marriage including: other family members, friends, co-workers, prostate cancer survivors met through the hospital, and hospital staff. All the respondents, both cancer survivors and their spouses, noted the importance of support from family members. This support ranged from being told they were loved by family to help with transportation to assistance with diet. Because about half of the spouses stated they did not want to burden their husbands with their own sadness, they relied of the support of friends and family. Several respondents also noted support from fellow church members. However, all of the participants did not welcome social support. Some reported being treated differently, and this often resulted in social isolation.

Spouse: “you know you have it and it's all like someone lookin' over your shoulder, watchin' you to see what you gonna do next; it's almost like a paraplegic; you know, everybody look at him instead a speakin' to him, letting him be normal, you know, they get that small eye look, you know, don't wanna touch ‘em or talk to ‘em or whatever cause they scared it might spread”.

The majority of respondents talked about people as a source of support, but a few survivors noted other types of support, such as the Internet to search for information or virtual support groups via the Internet.

Survivor: “No, I guess maybe from the onset, it was kinda scary but then in talking with some … I talked with some individuals; I have a cousin who has gone through it and another guy lives in my neighborhood that was around my age that had gone through it and I sat down and we talked about it, you know, and he shared with me so … and then I looked it up on the … online, on the Internet and got information and then, like I said, the … the clinical staff was very good and … and my doctor … he was very good in explaining all my options and everything to me. I shared more; I share with my family, my male … well, with my family when I go home; I shared with my church and in my community cause there's been several men within my church and in my community that has … that … one person's currently goin' through it now, through prostate cancer, and I … when I found out that he was goin' through it, I went up, you know, we … we sat down and talked about it and so it's … it's made me somewhat of an advocate …”

Physical Well-being: Sexual Functioning

Sexual functioning is frequently affected by its treatment. For prostate cancer survivors, this emerged as an area of primary concern and was experienced by all participants at varying levels.

Survivor: “I think it's one of the biggest problems because once a man finds out that he has prostate cancer, he's thinking that that's the end of his sex life almost and that's the way I felt pretty much when I was diagnosed with prostate cancer.”

The majority of survivors' spouses reported impaired sexual functioning; however, most women were more concerned with their husband's survival. For many of the survivors, their sexuality was intrinsically linked with their sense of masculinity and manhood.

Survivor: “The only problem I have is it seemed like it makes me less than what I thought I was. I mean, being … being a male, you know, you have these male tendencies to think that you all, everything and with the prostate cancer … and see, mine was a major surgery; they took everything so all I have left was just my … my … my regular male genders but there's no function; I mean, there's no … you can't get an erection on your own and this kinda things; you have to have help to do that and that's the only real part … major part I have problems with.”

However, the encouragement and support some survivors received from their spouses counteracted these feelings, decreasing their concern about their reduced sexual capacity. About half of the spouses stated that reduced libido and sexual activity was not considered a problem due to their age and commitment in the relationship.

Survivor: “Self-image, no, I know who I am and the fact of the matter that … that I would change didn't affect who I am; I know I'm more than just my physical part and, of course, my wife and I have a good relationship and communicated with each other; we knew, and we always laugh about it, at the time we could, we did.”

Spouse: “We been married 46 years and support was there and it strengthened him and I could see in him that there was times that I could detect… I knew when it was pressin' on his mind; I could tell that and those were the times that I stepped up to the plate and I gave assurance to him.”

Both the prostate cancer survivors and their spouses felt that they lacked information on the possibility of erectile dysfunction (ED) or other impacts on sexual functioning due to cancer treatment. Most of the spouses did not understand how sexual functioning was associated with prostate cancer and the side effects associated with their husband's cancer treatment. The majority of the survivors reported that they were not provided with counseling or in-depth information on possible options to manage ED.

Spouse: “Well, for me, by me bein' the age I am, … we not engaged like we use to because sometime I feel like it might be a waste of my time; I shouldn't feel like that way because I love my husband and I know what he's goin' through but it's different because as many times I be wantin' to wake him up at night, you know, for that but it … it's just not there; he tries but it just not there like it was and we … we try … we gonna try the Viagra but I'm scared of that because my husband has like a mental problem I think and he … I'm scared of it; I'm just scared of it.”

Both the survivors and spouses desired more information and guidance on techniques and resources to assist in the management of the effects of treatment on sexual functioning.

Physical Well-being: Lifestyle

Following prostate cancer diagnosis and treatment, both survivors and spouses reported marked changes in lifestyle, specifically in diet and exercise, emotional wellness, and bodily functions.

Survivor: “Well, I don't know if it mighta been gonna happen as time goes on but it have altered, you know, my sexual life and also altered my relationship far as bein' able to talk to my spouse or whatever; my lifestyle just changed period.”

Survivor: “I try not to eat as much red meat. You know, from everything I read, maybe you can tell me later; I mean, they don't really know what causes prostate cancer but there are certain gasses that I guess, fatty foods or greasy foods and stuff like that so I try to ease up but I haven't turned into a vegetarian …”

Survivor: “Well, I have to … you have to watch what you eat now because of, you know, your bowels and stuff, they … sometimes they don't act right.”

Depression and feelings of self-consciousness were reported by some of the survivors and were associated with changes in the body, such as sexual dysfunction, incontinence, and fatigue. However, emotional effects of diagnosis and treatment were more commonly voiced by the spouses.

Spouse: “Well, emotional changes, I just … sometime I just sit back and look at him, not tell him what's on my mind or how I feel about it cause I always … I keep sayin' in my mind we can work through this thing, you know, cause like I'm not goin' away; you ain't goin' nowhere either and I think sometime, he do wanna just hold me and caress me like he use to but he's … I guess his feelings, he pullin' it back or something.”

More than half of the participants discussed fatigue, incontinence, sexual dysfunction, and difficulty/pain when urinating. Additionally, a few survivors reported lack of appetite, fluctuating weight (i.e., weight loss and/or gain). To address the physical effects of cancer treatment, some survivors stated that they increased moderate activities for physical wellness (i.e., walking) and strived to maintain a healthy, more balanced diet (e.g., more vegetables, fewer soft drinks, less caffeine, vitamins, and supplements).

Spouse: “He would get very tired after treatment; he would come home and he did a lotta sleeping and laying down. He never really got sick to his stomach but it would drain him so he had to do a lot of resting.”

Survivor: “My prostate at that time had started to swell so the frequency of urination had increased and all the downsides of that which was stop and go urination, slow start, etc.”

Survivor: “My level of physical activity changed; I was quite tired, especially after the treatments; during the day after my treatments … I took the treatments very early in the morning so my … I guess my level of … I can't exactly put it into words but I was tired, more exhausted and tired durin' the day after I had completed my treatments during the day. So, it appears as though I required more rest durin' that time of my treatments … It eventually did return back to normal; I guess I was quite happy about that once it did.”

Spiritual Well-being

Most of the couples identified spirituality or some form of faith as an important coping mechanism through the diagnosis and treatment of prostate cancer.

Survivor: “Well, I'm a church going lady and I pray a lot. I prayed a lot and I read my Bible a lot … and my church, we have him on the prayer list and so do I, on the prayer list and I think by God's mercy, that keep me goin'.”

Survivor: “Like I said, I'm … I'm up here in age and I've found something to fulfill my lifestyle with; in other words, I have grandbabies; I concentrate on those and most of all, I have Jesus Christ, you know …”

Survivor: “I don't know where I'd be and that's the biggest thing … cause spirituality take care of stress; spirituality take care of pain, ok; you put all your worries and care in Jesus and that's the therapy you need, all right; occupational, you tell everybody you know about Jesus Christ; that's your job, all right, and … they gonna look at ya with a small eye but you go into a man house and he not ready take you in, brush your feet off and back out a the door, ok; spirituality relieves everything; if you got Jesus on your side, the health and life insurance, you don't need it.”

Furthermore, many of the cancer survivors and their spouses reported that their faith became stronger after experiencing cancer. At times, survivors reported that they prayer and reliance on their belief in God aided in the alleviation of stress and concern about the disease. Several participants also discussed God's will in their lives, which refers to the belief that events occur because it is what God desires and is, consequently, out of one's individual control. Therefore, prayers were used to express their appreciation to God for support in their healing and recovery.

Survivor: “I don't care what the doctor say; God can cure anything so … I do believe and I feel right now that he will … he's gonna take care of her and I believe he's takin' care of me also so …”

Survivor: “Even with my situation where the doctor say is treatable but not curable and my faith that anything that is treatable, God can cure it, you know, and thinkin' positive is what really keepin' both us goin'.”

Spiritual counseling was suggested by some participants as a valuable service for both cancer survivors and their spouses. Faith-based interventions could be utilized to help couples manage their experience with prostate cancer. Respondents reported seeking out spiritual support through their own networks by attending church services more frequently and becoming more involved in church activities.

Discussion

The purpose of this exploratory study was to systematically explore the psychosocial issues of African American prostate cancer survivors and their spouses. The overarching themes that emerged include: lack of knowledge and limited access to culturally appropriate information regarding management techniques of the treatment-related side effects; the lack of culturally appropriate coping strategies and problem solving skills; and the lack of effective communication strategies in the context of the marriage and with healthcare providers. While these findings elucidate the issues and experiences of African Americans prostate cancer survivors and their spouses, there were several parallels to the existing body of literature, primarily in the domains of communication, social support, and masculinity.

Commensurate with the current literature on the interpersonal communication patterns among prostate cancer survivors and their spouses, barriers to communication in the context of marriage and with healthcare providers emerged as the most common themes in this domain. Most of the couples identified communication as a relevant issue in the diagnosis and treatment of prostate cancer, but their perspectives regarding such varied. Among the survivors, reports of communication with their spouses about their cancer diagnosis and treatment were limited. Most of the spouses reported a desire to communicate with their husbands about their experiences and feelings with cancer. Interestingly, two thirds of the spouses did not force the conversation about cancer with their husbands because they were concerned about increased stress and anxiety within the context of the marriage. The lack of information exchange between the husband and wife often resulted in increased emotional distress, as well as uncertainty regarding the spouse ability to adequately care for and support their husband as they were undergoing treatment for prostate cancer. These findings are confirmatory with other studies examining the role and impact of communication post treatment for prostate cancer [42, 55]. Similar to the studies conducted by Eton et al. [14] and Lepore et al. [56] related to social constraint, there was reluctance among survivors' to discuss the impact of the side effects on their QOL. In a study by Boehmer and Clark [57] they also found, survivors reported not being comfortable disclosing their feelings about ED and other physical changes to their wives. To overcome these communicative barriers, most of the spouses recommended establishing a “communication triangle,” consisting of the healthcare provider, the prostate cancer survivor, and his spouse. While communication about the treatment options and expected health outcomes between the survivor and the healthcare provider was relatively appropriate, communication between the provider–spouse and the survivor–spouse were often limited.

The findings related to the domain of social support were also commensurate with the current body of science. Comparable to the findings of Kunkel et al., participants reported social support as being an integral factor for their psychological wellness and low levels of social support was accompanied by enhanced morbidity [58]. Similarly, participants reported social companionship provided a temporal shift from the stress and anxiety of having cancer [58]. The findings of this study also allowed for a greater understanding of the survivors' social network. Couples reported how involvement in social networks contributed to their social well-being by assisting in the development of feelings of predictability and stability [58]. While the spouse has been cited as the primary source of social support, survivors in this study reported a variety of sources beyond the spouse. These sources included family, church members, friends, co-workers, and other prostate cancer survivors. Dissimilar from previous findings, the nature of the social support ranged from being told they were loved by family members to help with overcoming various socio-cultural factors, such as with transportation, navigation to community-based resources for disease management and other information to assistance with obtaining information related to lifestyle modifications. The findings related to the caregiver burden were commensurate with previous findings. Most of the spouses stated they did not want to burden their spouse with their own sadness, fears, and life issues; thus, they relied on the support of family and friends.

As with previous studies, survivors' concept of masculinity was challenged as a result of changes in their ability to engage in sexual intimacy [46, 59]. Similar to Bokhour et al., participants reported how changes in sexual intimacy negatively impacted their self-image of being a man and ultimately their concept of manhood [59]. While several of the survivors reported receiving support from their spouses to overcome issues related to masculinity, most reported the need for additional information and strategies to manage the effects of treatment on sexual functioning.

The psychological dimension of fear, primarily related to recurrence and/or death from cancer, emerged as a dominant theme among the couples. While survivors were more likely to report fear of recurrence, spouses were more likely to report fear related to having enough information to intervene effectively to reduce treatment-related morbidity. Further investigation should include assessments of the relationship between fear, stress, and anxiety and the role of information, skill acquisition, and effective communication strategies. Similar to the work of Bellizzi et al. [60], fear of recurrence was found to influence mental and physical well-being. Fear of recurrence prompted and encouraged lifestyle and behavior modifications, inclusive of improved dietary consumption patterns, increased physical activity, and decreased tobacco and alcohol consumption. Most of the survivors and spouses indicated that they became more conscious of leading a healthy lifestyle. It was consistently noted by the couples the need for culturally appropriate resources to guide them through the myriad of issues encountered as a result of being treated for prostate cancer and how to best address them.

Several findings from this study that are prescriptive for developing culturally appropriate interventions include the role and impact of spirituality as a coping strategy; dissemination of salient information related to symptom management and effective communication strategies through culturally tested contexts and channels; and the psychological domain of fear and lifestyle modification. Spirituality emerged as a primary coping strategy within the context of the dyad. Most of the couples in this study identified spirituality or some form of faith as an important coping mechanism through the diagnosis, treatment, and disease management of prostate cancer. Many of the couples reported that their faith increased and became stronger after experiencing cancer. At times, survivors reported that prayer and reliance in their belief in God aided in the alleviation of stress and concerns about the disease. Similar to the few studies examining the role of spirituality, survivors reported the importance and centrality of their spirituality to their progression through the cancer continuum. Based on our findings and of other studies, it appears relationship status may influence spirituality, which may be associated with morbidity and overall QOL [34, 61, 62].

In consideration of the study findings, future interventions targeting the late and long term effect of prostate cancer treatment should be expanded in scope and designed within a culturally appropriate framework, incorporating the information and communication needs of diverse populations. Psychosocial interventions should also consider diverse models for addressing caregiver self-care, which support accrual of information, skills, and supported needed to manage their own physical and emotional needs, gain confidence in their caregiving role, maintain their social support system, and access resources to ease caregiving burden. Interventions should also include marital/family care with a focus on the information and skills to help couples to manage family and martial concerns, including communication, teamwork and intimate relationships.

Conclusions

Relatively little is known about the psychosocial effects of prostate cancer on African American men and their spouses [3]. This study is novel in that it: (1) addresses the growing need to examine other dimensions of QOL beyond the physical sequelae; (2) elucidates the role and impact of the psychosocial needs of African American spouses of men treated for prostate cancer; and (3) addresses the role and impact of psychosocial factors shared by African American men and their spouses. The findings from this study will assist with systematically addressing the impact of these psychosocial factors. Additional research should examine relationship quality which has evidenced facilitating adaptation for couples.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by funding from the American Cancer Society, Institutional Research grant #60132530120.

Contributor Information

Brian M. Rivers, Email: brian.rivers@moffitt.org, Health Outcomes & Behavior Program, H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute, 12902 Magnolia Drive, Tampa, FL 33612, USA; College of Medicine, Department of Oncologic Sciences, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL, USA.

Euna M. August, Health Outcomes & Behavior Program, H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute, 12902 Magnolia Drive, Tampa, FL 33612, USA; College of Public Health, Department of Community and Family Health, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL, USA

Gwendolyn P. Quinn, Health Outcomes & Behavior Program, H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute, 12902 Magnolia Drive, Tampa, FL 33612, USA; College of Medicine, Department of Oncologic Sciences, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL, USA

Clement K. Gwede, Health Outcomes & Behavior Program, H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute, 12902 Magnolia Drive, Tampa, FL 33612, USA; College of Medicine, Department of Oncologic Sciences, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL, USA

Julio M. Pow-Sang, Experimental Therapeutics Department, Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute, 12902 Magnolia Drive, Tampa, FL 33612, USA; Genitourinary Oncology Department, Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute, Tampa, FL, USA

B. Lee Green, Health Outcomes & Behavior Program, H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute, 12902 Magnolia Drive, Tampa, FL 33612, USA; College of Medicine, Department of Oncologic Sciences, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL, USA.

Paul B. Jacobsen, Health Outcomes & Behavior Program, H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute, 12902 Magnolia Drive, Tampa, FL 33612, USA

References

- 1.Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Krapcho M, et al., editors. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2007. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: 2010. [Accessed August 1, 2010]. Available from: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2007/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures for African Americans, 2009–2010. American Cancer Society; Atlanta, GA: 2009. [Accessed July 23, 2010]. Available from: http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@nho/documents/document/cffaa20092010pdf.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bennett CL, Ferreira MR, Davis TC, et al. Relation between literacy, race, and stage of presentation among low-income patients with prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:3101–3104. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.9.3101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conlisk EA, Lengerich EJ, Demark-Wahnefried W, Schildkraut JM, Aldrich TE. Prostate cancer: demographic and behavioral correlates of stage at diagnosis among blacks and whites in North Carolina. Urology. 1999;53(6):1194–1199. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(99)00005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cooper LA, Roter DL, Johnson RL, Ford DE, Steinwachs DM, Powe NR. Patient-centered communication, ratings of care, and concordance of patient and physician race. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139(11):907–915. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-11-200312020-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freedland SJ, Isaacs WB. Explaining racial differences in prostate cancer in the United States: sociology or biology? Prostate. 2005;62(3):243–252. doi: 10.1002/pros.20052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Howard G, Anderson RT, Russell G, Howard VJ, Burke GL. Race, socioeconomic status, and cause-specific mortality. Ann Epidemiol. 2000;10(4):214–223. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00038-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Odedina G, Anderson RT, Russell G, Howard VJ, Burke GL. Race, socioeconomic status, and cause-specific mortality. Ann Epidemiol. 2000;10(4):214–223. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00038-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roetzheim RG, Pal N, Tennant C, et al. Effects of health insurance and race on early detection of cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91(16):1409–1415. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.16.1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tarman GJ, Kane CJ, Moul JW, et al. Impact of socioeconomic status and race on clinical parameters of patients undergoing radical prostatectomy in an equal access health care system. Urology. 2000;56:1016–1020. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00808-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vijayakumar S, Weichselbaum R, Vaida F, Dale W, Hellman S. Prostate-specific antigen levels in African-Americans correlate with insurance status as an indicator of socioeconomic status. Cancer J Sci Am. 1996;2(4):225–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2010. American Cancer Society; Atlanta, GA: 2010. [Accessed September 10, 2010]. Available from: http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@nho/documents/document/acspc-024113.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aziz NM, Rowland JH. Trends and advances in cancer survivorship research: challenge and opportunity. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2003;13:248–266. doi: 10.1016/S1053-4296(03)00024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eton DT, Lepore SJ, Helgeson VS. Psychological distress in spouses of men treated for early-stage prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;103(11):2412–2418. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lubeck DP, Kim H, Gorssfeld G, et al. Health related quality of life differences between black and white men with prostate cancer: data from the cancer of the prostate strategic urologic research endeavor. J Urol. 2001;166(6):2281–2285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chhatre S, Wein AJ, Malkowicz SB, Jayadevappa R. Racial differences in well-being and cancer concerns in prostate cancer patients. J Cancer Surviv. 2011;5(2):182–190. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0170-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shavers VL, Brown ML. Racial and ethnic disparities in the receipt of cancer treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94(5):334–357. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.5.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E, editors. From cancer patient to cancer survivor: lost in transition Committee on Cancer Survivorship. National Academies Press; Washington: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Intercultural Cancer Council. 2006 Survivorship Report. Intercultural Cancer Council; Houston: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cliff AM, MacDonagh RP. Psychosocial morbidity in prostate cancer: II. A comparision of patients and partners. BJU Int. 2000;86(7):834–839. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2000.00914.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Given CW, Stommel M, Given BA, Osuch J, Kurtz ME, Kurtz JC. The influence of cancer patients' symptoms and functionalstatus on patients' depression and family caregivers' reaction anddepression. Health Psychol. 1993;12(4):277–285. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.12.4.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kornblith AB, Herr HW, Ofman US, Scher HI, Holland JC. Quality of life of patients with prostate cancer and their spouses. The value of a data base in clinical care. Cancer. 1994;73(11):2791–2802. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940601)73:11<2791::aid-cncr2820731123>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Northouse LL, Katapodi MC, Song L, Zhang L, Mood DW. Interventions with family caregivers of cancer patients: meta-analysis of randomized trials. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60(5):317–339. doi: 10.3322/caac.20081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Merrill RM, Lyon JL. Explaining difference in prostate cancer mortality rates between White and Black men in the United States. Urology. 2000;55(5):730–735. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(99)00564-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harlan L, Brawley O, Pommerenke F, et al. Geographic, age, and racial variation in the treatment of local/regional carcinoma of the prostate. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13(1):93–100. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clark JA, Inui TS, Silliman RA, et al. Patients' perceptions of quality of life after treatment for early prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(20):3777–3784. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Powe BD, Hamilton J, Hancock N, et al. Quality of life of African American cancer survivors. A review of the literature. Cancer. 2007;109(2 suppl):435–445. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bacon CG, Giovannucci E, Testa M, Glass TA, Kawachi I. The association of treatment-related symptoms with quality-of-life outcomes for localized prostate carcinoma patients. Cancer. 2002;94(3):862–871. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davison BJ, Degner LF. Empowerment of men newly diagnosed with prostate cancer. Cancer Nurs. 1997;20:187–196. doi: 10.1097/00002820-199706000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Giesler RB, Given BA, Given CW, Rawl S, Monahan P, Burns D, Azzouz F, Reuille KM, Weinrich S, Koch M, Champion V. Improving the quality of life of patients with prostate carcinoma: a randomized trial testing the efficacy of a nurse-driven intervention. Cancer. 2005;104(4):752–762. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lepore SJ, Helgeson VS. Psychoeducational support group enhances quality of life after prostate cancer. Cancer Res Ther Control. 1991;8:81–91. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mishel MH, Belyea M, Germino BB, Stewart JL, Bailey DE, Jr, Robertson C, Mohler J. Helping patients with localized prostate carcinoma manage uncertainty and treatment side effects: nurse-delivered psychoeducational intervention over the telephone. Cancer. 2002;94(6):1854–1866. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wittman D, Northouse L, Foley S, et al. The psychosocial aspects of sexual recovery after prostate cancer treatment. Int J Impot Res. 2009;21(2):99–106. doi: 10.1038/ijir.2008.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dahn JR, Penedo FJ, Gonzalez JS, et al. Sexual functioning and quality of life after prostate cancer treatment: considering sexual desire. Urology. 2004;63(2):273–277. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2003.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gore JL, Krupski T, Kwan L, Maliski S, Litwin MS. Partnership status influences quality of life in low-income, uninsured men with prostate cancer. Cancer. 2005;104(1):191–198. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baider L, Walach N, Perry S, Kaplan De-Nour A. Cancer in married couples: higher or lower distress? J Psychosom Res. 1998;45(3):239–248. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(98)00016-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sneeuw KC, Albertsen PC, Aaronson NK. Comparison of patient and spouse assessments of health related quality of life in men with metastatic prostate cancer. J Urol. 2001;165(2):478–482. doi: 10.1097/00005392-200102000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Galbraith ME, Arechiga A, Ramirez J, Pedro LW. Prostate cancer survivors' and partners' self-reports of health-related quality of life, treatment symptoms, and martial satisfaction 2.5–5.5 years after treatment. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2005;32(2):E30–E41. doi: 10.1188/05.ONF.E30-E41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harden J, Northouse L, Cimprich B, Pohl JM, Liang J, Kershaw T. The influence of developmental life stage on quality of life in survivors of prostate cancer and their partners. J Cancer Surviv. 2008;2(2):84–94. doi: 10.1007/s11764-008-0048-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harden JK, Northouse LL, Mood DW. Qualitative analysis of couples' experience with prostate cancer by age cohort. Cancer Nurs. 2006;29(5):367–377. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200609000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Badr H, Taylor CL. Sexual dysfunction and spousal communication in couples coping with prostate cancer. Psychooncol-ogy. 2009;18(7):735–746. doi: 10.1002/pon.1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Garos S, Kluck A, Aronoff D. Prostate cancer patients and their partners: differences in satisfaction indices and psychological variables. J Sex Med. 2007;4(5):1394–1403. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harden J, Schafenacker A, Northouse L, et al. Couples' experiences with prostate cancer: focus group research. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2002;29(4):701–709. doi: 10.1188/02.ONF.701-709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Couper J, Bloch S, Love A, et al. Coping patterns and psychosocial distress in female partners of prostate cancer patients. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(4):375–382. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.4.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Manne SL, Badr H, Zaider T, Nelson C, Kissane D. Cancer-related communication, relationship intimacy, and psychological distress among couples coping with localized prostate cancer. J Cancer Surviv. 2010;4(1):74–85. doi: 10.1007/s11764-009-0109-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rivers BM, August EM, Gwede CK, et al. Psychosocial issues related to sexual functioning among African-American prostate cancer survivors and their spouses. Psychooncology. 2011;20(1):106–110. doi: 10.1002/pon.1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Campbell LC, Keefe FJ, Scipio C, et al. Facilitating research participation and improving quality of life for African American prostate cancer survivors and their intimate partners. A pilot study of telephone-based coping skills training. Cancer. 2007;109(2 suppl):414–424. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Campbell LC, Keefe FJ, McKee DC, et al. Prostate cancer in African Americans: relationship of patient and partner self-efficacy to quality of life. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2004;28(5):433–444. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ferrell BR, Dow KH, Grant M. Measurement of the quality of life in cancer survivors. Qual Life Res. 1995;4(6):523–531. doi: 10.1007/BF00634747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ferrell BR, Dow KH, Leigh S, Ly J, Gulasekaram P. Quality of life in long-term cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1995;22(6):915–922. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Patton M. Qualitative evaluation and research methods. Sage; Newbury Park: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stockdale A. An approach to recording, transcribing, and preparing audio data for qualitative analysis. Center for Applied Ethics and Professional Practice; Newton: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Duncan DF. Content analysis in health education research: an introduction to purposes and methods. Health Educ. 1989;20(7):27–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Glaser BG. The constant comparative method of qualitative analysis. Soc Probl. 1965;12(4):436–445. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kershaw TS, Mood DW, Newth G, et al. Longitudinal analysis of a model to predict quality of life in prostate cancer patients and their spouses. Ann Behav Med. 2008;36(2):117–128. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9058-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lepore SJ, Helgeson VS. Social constraints, intrusive thoughts, and mental health after prostate cancer. Cancer Res Ther Control. 1998;17(1):89–106. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Boehmer U, Clark JA. Communication about prostate cancer between men and their wives. J Family Pract. 2001;50(3):226–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kunkel EJS. The assessment and management of anxiety in patients with cancer. In: Thompson TL, editor. Medical-surgical psychiatry: treating psychiatric aspects of physical disorders. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bokhour BG, Clark JA, Inui TS, Silliman RA, Talcott JA. Sexuality after treatment for early prostate cancer: exploring the meanings of “erectile dysfunction”. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(10):649–655. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.00832.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bellizzi KM, Latini DM, Cowan JE, DuChane J, Carroll PR. Fear of recurrence, symptom burden, and health-related quality of life in men with prostate cancer. Urology. 2008;72(6):1269–1273. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.12.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bowie J, Sydnor KD, Granot M. Spirituality and care of prostate cancer patients: a pilot study. J Natl Med Assoc. 2003;95(10):951–954. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brady MJ, Peterman AH, Fitchett G, Mo M, Cella D. A case for including spirituality in quality of life measurement in oncology. Psychooncology. 1999;8(5):417–428. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1611(199909/10)8:5<417::aid-pon398>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]