Abstract

Objectives

To determine functional status and mortality rates after colon cancer surgery in older nursing home residents.

Design

Retrospective cohort study.

Setting and Participants

6822 nursing home residents age 65 and older who underwent surgery for colon cancer in the United States between 1999 and 2005.

Measurements

Changes in functional status were assessed before and after surgery using the Minimum Data Set-Activities of Daily Living (MDS-ADL) summary scale, a 28-point scale in which score increases as functional dependence increases.

Methods

Using the Medicare Inpatient File and the Minimum Data Set for Nursing Homes, we identified the 6822 nursing home residents age 65 and older who underwent surgery for colon cancer. We used regression techniques to identify patient characteristics associated with mortality and functional decline at 1 year after surgery.

Results

On average, residents who underwent colectomy experienced a 3.9 point worsening in MDS-ADL score at one year. One year after surgery, the rates of mortality and sustained functional decline were 53% and 24%, respectively. In multivariate analysis, older age (age 80+ v. age 65–69, adjusted relative risk (ARR 1.53), 95%CI 1.15–2.04, p<0.001), readmission after surgical hospitalization (ARR 1.15), 95%CI 1.03–1.29, p<0.01), surgical complications (ARR 1.11), 95%CI 1.02–1.21, p<0.02), and functional decline before surgery (ARR 1.21, 95%CI 1.11–1.32, p<0.0001) were associated with functional decline at one year.

Conclusion

Mortality and sustained functional decline are very common after colon cancer surgery in nursing home residents. Initiatives aimed at improving surgical outcomes are needed in this vulnerable population.

Keywords: surgery, functional decline, nursing home residents

INTRODUCTION

The decision to undergo major surgery for cancer involves weighing its potential benefit in ameliorating symptoms or prolonging life against its risks. Among frail older patients with limited life expectancy, the benefits of cancer surgery are often unclear, and the use of cancer-directed surgery for technically resectable tumors declines as patients age.1. For this reason, a realistic and comprehensive assessment of surgical outcomes is essential to inform decision-making.

The risks of surgery, however, are often defined in terms of short-term morbidity and mortality and not long-term function. There is evidence that while patients with limited life expectancy are willing to undergo procedures with a high risk of perioperative mortality, they are very reluctant to accept interventions that carry a risk of sustained functional impairment.2 Some studies suggest that functional declines after surgery in the elderly are transient and reversible.3, 4 Other studies using multiple measures of functional independence have found that functional recovery after major surgery among community dwelling elders can be protracted. In a prospective study of functional independence after abdominal surgery among patients age 60 and older, Lawrence et al found that protracted disability after surgery was common.5 Over half of patients had a decrease in objective measures of strength and mobility 6 months after surgery. Functional recovery among the frailest elders – nursing home residents — is likely to be substantially worse.

Currently, functional outcomes after major cancer surgery in nursing home residents are poorly understood. For this reason, we used data from national Medicare claims and the Minimum Data Set for Nursing Homes to assess functional status and survival among elderly nursing home residents in the United States undergoing surgery for colon cancer.

METHODS

Subjects and Databases

To identify a cohort of long term nursing home residents undergoing surgery, we linked data from 100% national Medicare Inpatient Files (2000–2005) with the Minimum Data Set for Nursing Homes (MDS, 1999–2006). The Medicare Inpatient File contains discharge abstracts for all fee-for-service inpatient hospitalizations for Medicare beneficiaries. The MDS is a mandatory assessment of all nursing home residents who reside in facilities participating in Medicare or Medicaid programs. MDS assessments of patient health and function are administered by nursing staff and are completed at the time of admission, readmission, quarterly, and when the resident experiences a change in clinical status.

We examined the functional outcomes of nursing home residents age 65 and older who underwent surgery for colon cancer. This procedure was selected because it is the most frequently performed major cancer operation in the nursing home population (over 6000 performed over the study period) and is associated with substantial morbidity and mortality in the elderly. Subjects were identified by International Classification of Disease, version 9 (ICD-9) diagnosis and procedure codes in the Medicare Inpatient File (Appendix, 1) and classified as long-term nursing home residents if they underwent 2 or more consecutive MDS assessments performed over 90 days apart during the 6 months prior to surgery, indicating a pre-operative nursing home length of stay greater than 90 days.

To compare outcomes of nursing home residents to benchmark mortality and functional decline in residents the general nursing home population, we identified a cohort of nursing home residents who did not undergo surgery during the same period matched on age, gender, race, year of admission, and comorbidity.

Covariates

Resident characteristics were obtained from both the Medicare claims and the MDS. Demographic data was obtained from the Medicare Denominator file. Comorbid diagnoses were obtained both from MDS assessments and from the MEDPAR file. To assess overall comorbid disease burden, comorbidities were compiled into a Charlson score in the multivariate model.6, 7 Residents were defined as having dementia if they had at least one of the 3 criteria: (1) disease diagnosis on MDS assessment, (2) ICD-9 diagnosis code in Medicare claim, or (3) MDS Cognitive Performance Scale (CPS) score >=3. The MDS-CPS is a validated scale of cognitive function8 and a CPS score of 3 indicates moderate cognitive impairment and has been used to define dementia.9

Functional status was measured using MDS assessments of self-performance of the Activities of Daily Living. Data on ADL performance in the MDS include questions about mobility in 7 activities: mobility while in bed, transferring, ambulation, dressing, eating, toileting, and personal hygiene. The resident’s performance of each of these activities is rated using a scoring system of 0 to 4 points, ranging from 0 indicating independence to 4 indicating total dependence. The sum of these 7 scores – the Minimum Data Set-Activities of Daily Living (MDS-ADL) score – has been validated against standardized measures of functional independence.10, 11 Possible total scores range from 0 for independence in all activities to 28 indicating total dependence in all activities. We defined baseline functional status as the MDS-ADL summary score reported on the most recent MDS assessment prior to the surgical hospitalization. To account for the impact of pre-operative functional decline, we categorized residents as experiencing preoperative functional decline if they had a >=2 MDS-ADL score increase prior to their surgical admission. To explore the impact of baseline functional status on death and functional decline, we divided nursing home residents into 4 approximately equal sized groups (quartiles) based on the most recent MDS-ADL summary score prior to their surgical admission.

To assess the impact of perioperative events on 1-year mortality and functional decline, we identified postoperative complications in the MEDPAR file using coding algorithms adapted from previous studies.4 (Appendix, 1)Thirty-day readmission rates were determined using the MEDPAR file.

Outcome Measures

Our primary outcome measures were functional status and mortality. Consistent with prior published studies, we defined functional decline as a MDS-ADL score increase of two or more points.12 Residents who had an increase of 1 point, no change, or a decrease in MDS-ADL score were classified as having maintained ADL function. We measured the proportion of residents who died, maintained ADL function or experienced ADL decline at 4 time intervals: 0–3 months, 3–6 months, 6–9 months, and 9–12 months. Death was determined using date of death information from the Medicare Denominator file.

Statistical Analysis

We fit log Poisson regression models to estimate the relative risks of functional decline among survivors at one year after surgery associated with individual resident characteristics, including an interaction term for age and sex. We initially performed the analyses with functional decline among 1-year survivors as a primary outcome measure. In order to account for the potential impact of the 410 1-year survivors with missing assessments in the final time interval (9–12 months), we performed the multivariate analysis two ways as a sensitivity analysis: classifying the residents missing postoperative assessments as having (1) declined in function and (2) maintained function.

We explored functional trajectories before and after surgery using mixed effects spline models to incorporate the multiple measurements for each subject. Specifically, we used restricted cubic spline models with 5 knots placed at 3 months and 1 month prior to surgery, and 1, 4, and 12 months after surgery. Knots were chosen based on substantive clinical considerations, although the fitted curves were very similar when knots were chosen based on Harrell’s quantile-based recommendations.13 Models included fixed and random effects for the coefficients of the spline, implying that each subject’s measurements were scattered around a subject-specific smooth curve; these subject-specific smooth curves were then departures from the average smooth trajectory for the population. Fixed effects for age, sex, race, and comorbidity, were also included, allowing the population trajectory to shift based on the baseline characteristics. To explore the influence of baseline functional status on functional trajectories after surgery, we compared functional trajectories among residents stratified according to their baseline functional status quartile. To account for the 410 nursing home residents who were alive but did not have ADL assessments in months 9–12, we repeated the analysis using multiple imputations to predict MDS-ADL scores at 12 months.

We used the Kaplan-Meier method to estimate cumulative one-year mortality from the date of surgery. We then used Cox proportional hazards models to estimate the relative risk of mortality associated with individual resident characteristics. Mortality rates were censored at the end of the follow-up period.

In all analyses, the nursing home resident was the unit of analysis. Statistical significance in the Poisson regression and Cox proportional hazards models were defined using a P value of 0.05 using 2-sided significance testing. This study was approved by the University of California, San Francisco Committee on Human Research. The funding organization had no role in the design and conduct of the study, the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data, or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

RESULTS

Resident Characteristics

During the study period, 6822 long-stay nursing home residents nationwide underwent surgery for colon cancer. These residents had a mean age of 82.9 (Table 1). The majority (68%) were female and 86% were white. The mean MDS-ADL summary scale score prior to surgical admission was 12.7 (SD+/−8.2), indicating a more poorly functioning cohort, and 16% of residents had experienced decline in ADL function (>=2 point worsening in MDS-ADL score) in the 6 months prior to surgery. The majority of residents (64%) were admitted to the hospital urgently or emergently. Half of the residents had a diagnosis of dementia before surgery and nearly a third (30%) had a history of congestive heart failure and diabetes.

Table 1.

Characteristics of nursing home residents undergoing surgery for colon cancer

| Characteristic | Cohort |

|---|---|

| Age (mean, SD) | 82.9 ± 7.5 |

| Age group (%) | |

| 65–69 | 6 |

| 70–79 | 26 |

| 80+ | 68 |

| Sex (% female) | 68 |

| Race (%) | |

| White | 86 |

| Black | 12 |

| Other | 3 |

| Baseline MDS-ADL summary score (mean, SD) | 12.7 ± 8.2 |

| Baseline MDS-ADL summary score quartiles (%) | |

| MDS-ADL summary score 0–6 | 24 |

| MDS-ADL summary score 7–13 | 25 |

| MDS-ADL summary score 14–18 | 24 |

| MDS-ADL summary score 19–28 | 27 |

| Functional decline prior to surgery (%) | 16 |

| Comorbid diagnoses (%) | |

| Dementia | 50 |

| Congestive heart failure | 30 |

| Diabetes | 30 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 22 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 21 |

| Coronary artery disease | 18 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 10 |

| Renal failure | 5 |

| Charson score | |

| 0 | 20 |

| 1 | 20 |

| 2 | 19 |

| 3+ | 42 |

| Admission status (%) | |

| Elective | 36 |

| Urgent/emergent | 64 |

One-Year Mortality

Overall, cumulative 1-year mortality was 53%. (Figure 1a) In survival analysis stratified by baseline MDS-ADL score quartile, one-year mortality increased with increasing ADL impairment – 46% for quartile 1, 51% for quartile 2, 53% for quartile 3, and 63% for quartile 4.(Figure 1b) In the matched cohort of nursing home residents undergoing surgery, one year mortality was 31%. (Appendix, 2) In multivariate analysis, age was the strongest predictor of 1-year mortality.(Table 2) One-year mortality was significantly more likely among resident 80 and older than among younger elders (age 65–69) (AHR 1.75, 95%CI 1.38–2.23). The presence of a surgical complication significantly increased the likelihood of 1-year mortality (AHR 1.80, 95%CI 1.65–1.96). Functional decline prior to surgery and Charlson comorbidity score of 3 or greater were also independently associated with death within one year after surgery(AHR 1.16, 95%CI 1.06–1.27 and AHR 1.12, 95%CI 1.01–1.23, respectively).

Figure 1.

1-year mortality and functional trajectories before and after surgery: (a) all residents and (b) residents stratified by baseline MDS-ADL score.

Table 2.

Resident characteristics associated with 1-year mortality

| 1 year mortality (unadjusted) |

Adjusted hazard ratio | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Characteristic | % | P | HR, 95% CI | P |

| Age group | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||

| 65–69 | 38.7 | Referent | ||

| 70–79 | 45.5 | 1.23 (0.96–1.58) | ||

| 80+ | 51.6 | 1.75 (1.38–2.23) | ||

| Sex | 0.004 | |||

| Female | 48.1 | Referent | ||

| Male | 51.8 | 0.98 (0.88–1.09) | 0.68 | |

| Race | <0.0001 | 0.01 | ||

| White | 48.8 | Referent | ||

| Black | 55.7 | 1.08(0.98–1.20) | ||

| Other | 38.2 | 0.75 (0.59–0.95) | ||

| Functional decline prior to surgery | 52.3 | 0.03 | 1.16 (1.06–1.27) | 0.002 |

| Baseline MDS-ADL summary score quartiles | <0.0001 | 0.003 | ||

| Group 1: MDS-ADL summary score 0–6 | 43.8 | Referent | ||

| Group 2: MDS-ADL summary score 7–14 | 47.3 | 1.07 (0.97–1.18) | ||

| Group 3: MDS-ADL summary score 15–18 | 50.0 | 1.19 (1.08–1.32) | ||

| Group 4: MDS-ADL summary score 19–28 | 56.1 | 1.26 (1.14–1.39) | ||

| Charlson score | 0.004 | 0.07 | ||

| 0 | 47.3 | Referent | ||

| 1 | 46.3 | 1.01 (0.90–1.13) | ||

| 2 | 49.1 | 1.08 (0.96–1.20) | ||

| 3+ | 51.7 | 1.12 (1.01–1.23) | ||

| Readmitted after 30 days | 43.6 | <0.0001 | 0.38 (0.35–0.41) | <0.0001 |

| Surgical complication | 56.1 | <0.0001 | 1.80 (1.65–1.96) | <0.0001 |

| Urgent/emergent admission | 54.0 | <0.0001 | 1.39 (1.29–1.50) | <0.0001 |

Functional decline

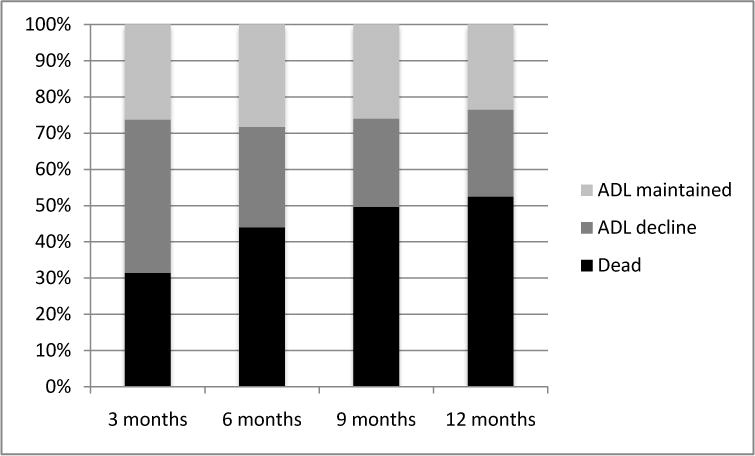

The proportion of residents who experienced functional decline from pre-operative levels was greatest during the first 3 months after surgery – 42% of the entire cohort and 62% of surviving residents. (Figure 2) In the following 3 time intervals, approximately a quarter of residents had MDS-ADL scale scores >=2 points worse than baseline scores – 28% at 6 months, 24% at 9 months, and 24% at 12 months. Among survivors, approximately half had functional decline at 6, 9, and 12 months after surgery. In multivariate analysis, several resident characteristics were associated with functional decline at one year (Table 3). Among 1-year survivors, residents age 80 and older were over 50% more likely than younger residents (age 65–69) to experience functional decline (Adjusted relative risk (ARR) 1.53, 95%CI 1.15–2.04). Residents who had experienced functional decline in the 6 months prior to surgery were more likely to decline after surgery (ARR 1.21, 95%CI 1.11–1.32). In general, nursing home residents in the poorest baseline MDS-ADL functional quartile were less likely than residents who had lower (better) MDS-ADL scores to lose function after surgery (ARR 0.68, 95%CI 0.60–0.76 for MDS-ADL quartiles 4 versus MDS-ADL quartile 1). Surgical complications and hospital readmission after 30 days was also associated with functional decline (ARR 1.11, 95%CI 1.02–1.21 and ARR 1.15, 95%CI 1.03–1.29, respectively). Residents with missing functional status assessments at one year were on average 1 year older, had higher Charlson scores, and were more likely to be in the 2nd and 3rd quartile of functional status than resident with functional assessments at one year. (Appendix, 3). In sensitivity analysis recoding missing residents as having (a) declined or (b) maintained function, point estimates for relative risks of functional decline associated with resident characteristics were similar(Appendix, 4).

Figure 2.

Proportion of residents who experienced ADL decline, maintenance of ADL, and death.

Table 3.

Resident characteristics associated with functional decline among 1-year survivors

| Proportion of residents who experienced functional decline | Adjusted relative risk of functional decline | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Characteristic | % | p-value | RR, 95% CI | p-value |

| Age group | <0.0001 | 0.001 | ||

| 65–69 | 37.8 | Referent | ||

| 70–79 | 48.1 | 1.31 (0.98–1.76) | ||

| 80+ | 52.8 | 1.53 (1.15–2.04) | ||

| Sex | 0.70 | |||

| Female | 50.8 | Referent | ||

| Male | 50.0 | 1.07 (0.96–1.21) | 0.23 | |

| Race | 0.56 | 0.15 | ||

| White | 50.4 | Referent | ||

| Black | 50.0 | 1.08 (0.96–1.21) | ||

| Other | 56.0 | 1.16 (0.97–1.38) | ||

| Functional decline prior to surgery | 59.9 | <0.0001 | 1.21 (1.11–1.32) | <0.0001 |

| Baseline MDS-ADL summary score quartiles | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||

| Group 1: MDS-ADL summary score 0–6 | 54.1 | Referent | ||

| Group 2: MDS-ADL summary score 7–14 | 60.7 | 1.10 (1.01–1.20) | ||

| Group 3: MDS-ADL summary score 15–18 | 48.8 | 0.91 (0.82–1.00) | ||

| Group 4: MDS-ADL summary score 19–28 | 35.9 | 0.68 (0.60–0.76) | ||

| Charlson score | 0.0003 | 0.005 | ||

| 0 | 55.4 | Referent | ||

| 1 | 52.5 | 0.94 (0.85–1.03) | ||

| 2 | 52.8 | 0.92 (0.83–1.02) | ||

| 3+ | 45.7 | 0.84 (0.77–0.93) | ||

| Readmitted after 30 days | 51.8 | 0.001 | 1.15 (1.03–1.29) | 0.02 |

| Surgical complication | 55.3 | 0.01 | 1.11 (1.02–1.21) | 0.01 |

| Urgent/emergent admission | 52.5 | 0.01 | 1.10 (1.03–1.18) | 0.007 |

Functional Status Trajectories

On average, MDS-ADL scale scores increased from 13.4 points (95%CI 13.1–13.8) 1 month before surgery to 17.3 points (95%CI 16.9–17.8) 1 year after surgery, indicating a decline in function from baseline.(Figure 1a) In the mixed-effects model, the greatest increase (worsening) from baseline mean MDS-ADL scores–4.9 points – occurred between the preoperative and 1 month postoperative assessments (13.4 points to 18.3 points). Average MDS-ADL scale scores 4 months after surgery were 16.0 (95%CI 15.6–16.3). Among the matched cohort of nursing home residents undergoing surgery, the average MDS-ADL score increased 1.8 points after one year. (Appendix, 2)

In analysis stratified by pre-operative functional status, the magnitude of decline and recovery was greatest among the residents with MDS-ADL scores between 0 and 6 (quartile 1) (Figure 1). Residents in quartile 1 experienced, on average, an increase in MDS-ADL score from 4.2 points (95%CI 3.8–4.6) before surgery to 13.0 points (95%CI 12.6–13.4) at one month after surgery followed by modest MDS-ADL score improvement to 8.5 points (95%CI 8.1–9.0). At one year, average MDS-ADL scores had worsened to 10.1 point (95%CI 9.5–10.8). Among the most dependent residents (MDS-ADL score 19–28, quartile 4), changes in average MDSADL scores after surgery were small. Baseline MDS-ADL scores (22.7, 95%CI 22.4–23.0) worsened on average by 1.2 points at one month, then improved by 0.5 points at 4 months, and then worsened by 0.6 points.

DISCUSSION

Nursing home residents with colon cancer experience substantial functional decline after surgical resection. One-year mortality is high and the majority of survivors do not return even to baseline levels of ADL functioning one year after surgery. Advanced age, surgical complications, hospital readmission, and pre-operative functional decline were independently associated decline in function after surgery. The magnitude of both worsening and subsequent recovery in MDS-ADL scores after surgery was greatest among residents with the best MDS-ADL scores prior to surgery. Although the magnitude of the recovery from the functional nadir was greatest in residents with the best baseline ADL function, the average decline from baseline at one year was greatest in this group, suggesting that residents most independent in performance of ADLs stand to lose the most functionally after major surgery. Residents with the worst baseline MDS-ADL scores experienced smaller measurable functional decline due to ‘floor effects’. Floor effects occur when scores are grouped at maximal poor functioning which lowers the ability to detect clinically important changes in functional status.

To our knowledge, this is the first population-based study examining functional outcomes in a 100% national sample of elder nursing home residents undergoing major surgery. Our study calls into question findings from recent studies reporting that functional declines after cancer surgery in the very elderly are transient and reversible. In a study of 223 patients age 75 and older undergoing surgery for gastric and colorectal cancer, Amemiya et al found that only 3% of patients had persistent ADL decline 6 months after surgery.4 Similarly, Van Cleave et al reported that functional status was significantly better at 3 and 6 months after surgery than at baseline among community dwelling elders undergoing major cancer surgery.3 Many studies, however, include highly selected healthy elders and rely on self-reported measures of functional status after surgery. In our study, functional status was assessed longitudinally using validated ADL assessment scales that are performed quarterly by trained evaluators, decreasing the likelihood of follow-up bias.

Our study, however, has several limitations. Mortality was high in the first year after surgery and the number of nursing home residents who underwent functional assessments decreased over time. It is likely that average MDS-ADL scale scores improved as more disabled residents died. For this reason, we may have overestimated functional recovery after surgery. Our survival analysis is also limited by the fact that neither the MDS nor Medicare claims have information about cancer stage. Because the Medicare Inpatient file and the MDS do not have information about outpatient services, we do not have information complete about adjuvant cancer treatments that may influence functional status. The use of adjuvant therapy in this frail population, however, is likely infrequent. Prior research has found that only 6% of nursing home residents with cancer receive radiation or chemotherapy.14 Since functional decline is common in general nursing home population15 and among elders hospitalized for medical illnesses16, it is difficult to determine with certainty the contribution of surgery to the functional impairment observed at one year after surgery. However, McConnell et al found that, on average, the change in ADL dependence over 1 year in long-stay nursing home residents is one point or less.17 In our matched benchmark group of nursing home residents, functional decline was 1.8 points. Despite this limitation, our finding that rates of mortality and functional decline are very high among residents selected for surgery – particularly the oldest old – should inform patient selection for surgery and provide realistic expectations about outcomes after surgery. Finally, because our analysis is limited to long stay nursing home residents, our findings may not be generalizable to community dwelling elders.

Our study has important implications for surgical decision-making in nursing home residents. The majority of residents in our study were admitted urgently or emergently for surgery suggesting they presented with an acute complication of their cancer (i.e. bleeding or obstruction). For truly life-limiting conditions, the mortality rates observed in our study are not high enough to suggest that surgery is futile, either to lengthen life or to palliate symptoms–nearly half of the nursing home residents who underwent surgery were alive at one year. Even when not curative, surgery for colon cancer may be an effective palliative procedure. Use of less invasive therapies, however, may be an effective alternative to surgery for patients with limited life expectancy. Endoscopic treatment or embolization of bleeding tumors may be a more appropriate approach than operative therapy. Similarly, selective use of endoluminal stents for large bowel obstruction may be an effective, less invasive option. Further work is needed to determine whether alternative therapeutic options may benefit patients with limited life expectancy and to understand the impact of these therapies on physical functioning.

Information about the expected survival benefits and the likelihood of sustained functional decline after surgery will also help patients and caregivers set realistic expectations for surgical outcomes and inform decisions about whether to undergo surgery. While many patients with limited life expectancy are willing to undergo palliative procedures that carry a high risk of mortality, they are most often reluctant to undergo surgery if there is a high likelihood of protracted postoperative functional decline.2 Knowledge of expected outcomes can also help patients and physicians anticipate and prepare for difficult care decisions about life sustaining interventions after surgery.

For nursing home residents who undergo surgery, quality improvement initiatives targeting surgical care in the elderly may improve outcomes. Because surgical complications and hospital readmission are independently associated with functional decline after surgery, improvements in acute surgical care will likely result in better functional outcomes in this population. Interventions specifically aimed at enhancing post-operative functional recovery mayalsoprevent functional decline after surgery. For elders admitted to the hospital with medical diagnoses, inpatient protocols for rehabilitation and prevention of disability have been shown to improve the ability of older patients to perform ADLs at the time of discharge.18 Similar protocols would likely improve functional recovery in elder surgical patients. The success of “fast track” protocols over the past decade in enhancing recovery in patients undergoing colectomy should serve as a model for “geriatric track” protocols for elder surgical patients.19 Furthermore, our finding that functional recovery is protracted suggests that prolonged rehabilitation and restorative care in the nursing home after hospital discharge is important. Further work is needed to identify interventions targeted at improving functional recovery in nursing home residents after discharge from their surgical hospitalization.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Dr. Finlayson was supported by a National Institute on Aging/Paul B. Beeson Clinical Scientist Development Award in Aging (K08AG028965).

Footnotes

Sponsor’s Role: The funding sources had no role in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collections, analysis and preparation of paper.

Conflict of Interest: The editor in chief has reviewed the conflict of interest checklist provided by the authors and has determined that the authors have no financial or any other kind of personal conflicts with this paper.

References

- 1.O’Connell JB, Maggard MA, Ko CY. Cancer-directed surgery for localized disease: decreased use in the elderly. Ann Surg Oncol. 2004;11:951–2. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2004.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fried TR, Bradley EH, Towle VR, et al. Understanding the treatment preferences of seriously ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1061–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa012528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Cleave JH, Egleston BL, McCorkle R. Factors affecting recovery of functional status in older adults after cancer surgery. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;59:34–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03210.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amemiya T, Oda K, Ando M, et al. Activities of daily living and quality of life after elective surgery for gastric and colorectal cancers. Ann Surg. 2007;246:222–8. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3180caa3fb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lawrence VA, Hazuda HP, Cornell JE, et al. Functional independence after major abdominal surgery in the elderly. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;199:762–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.05.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:613–9. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chron Dis. 1987;40:373–83. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morris JN, Fries BE, Mehr DR, et al. MDS Cognitive Performance Scale. J Gerontol. 1994;49:M174–M82. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.4.m174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Dijk PTM, Mehr DR, Ooms ME, et al. Comorbidity and 1-year mortality risks in nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:660–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carpenter GI, Hastie CL, Morris JN, Fries BE, Ankri J. Measurung change in activities of daily living in nursing home residents with moderate to severe cognitive impairmnent. BMC Geriatr. 2006;6:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-6-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hawes C, Morris JN, Phillips CD, Mor V, Fries BE, Nonemaker S. Reliability estimates for the Minimum Data Set for nursing home resident assessment and care screening (MDS) Gerontologist. 1995;35:172–8. doi: 10.1093/geront/35.2.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tamura M, Covinsky K, Chertow G, Yaffe K, Landefeld C, McCulloch C. Functional status of elderly adults before and after initiation of dialysis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1539–47. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harrell FJ. Regression modeling strategies. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bradley CJ, Clement JP, Lin C. Absence of cancer diagnoses and treatment in elderly Medicaid-insured nursing home residents. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:21–31. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li Y, Cai X, Mukamel DB, Laurent LG. The volume-outcome relationship in nursing home care: An examination of functional decline among long-term care residents. Med Care. 2010;48:52–7. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181bd4603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boyd CM, Landefeld CS, Counsell SR, et al. Recovery of activities of daily living in older adults after hospitalization for acute medical illnesses. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:2171–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02023.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McConnell ES, Branch LG, Sloane RJ, Pieper CF. Natural history of change in physical function among long-stay nursing home residents. Nurs Res. 2003;52:119–26. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200303000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Landefeld CS, Palmer RM, Kresevic DM, Fortinsky RH, Kowal J. A randomized trial of care in hospital medical uit especially designed to improve the functional outcomes of acutely ill older patients. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1338–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505183322006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gouvas N, Tan E, Windsor A, Xynos E, Tekkis PP. Fast-track vs standard care in colorectal surgery: a meta-analysis update. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2009;24:1119–31. doi: 10.1007/s00384-009-0703-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.