Abstract

In recent years ‘frustrated Lewis pairs’ (FLPs) have been shown to be effective metal-free catalysts for the hydrogenation of many unsaturated substrates. Even so, limited functional-group tolerance restricts the range of solvents in which FLP-mediated reactions can be performed, with all FLP-mediated hydrogenations reported to date carried out in non-donor hydrocarbon or chlorinated solvents. Herein we report that the bulky Lewis acids B(C6Cl5)x(C6F5)3−x (x=0–3) are capable of heterolytic H2 activation in the strong-donor solvent THF, in the absence of any additional Lewis base. This allows metal-free catalytic hydrogenations to be performed in donor solvent media under mild conditions; these systems are particularly effective for the hydrogenation of weakly basic substrates, including the first examples of metal-free catalytic hydrogenation of furan heterocycles. The air-stability of the most effective borane, B(C6Cl5)(C6F5)2, makes this a practically simple reaction method.

Keywords: boranes, frustrated Lewis pairs, heterocycles, hydrogenation, solvent effects

Since the initial reports into their reactivity by Stephan et al., frustrated Lewis pairs (FLPs) have attracted great interest for their ability to act as metal-free polar hydrogenation catalysts.[1] By rational modification of both the Lewis acidic and Lewis basic components, FLPs have been developed that are effective for the reduction of a wide range of unsaturated substrates, both polar (e.g. imines, enol ethers)[2] and non-polar (e.g. 1,1-diphenylethylene).[3]

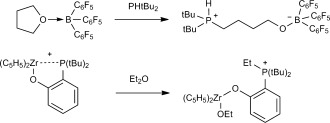

In addition to H2, FLPs have been shown to readily react with a wide variety of other functional groups including ethers,[4] carbonyls,[5] and weakly acidic C=H[6] and N=H bonds.[7] Though impressive, this diverse reactivity has generally rendered FLPs incompatible with many common organic solvents. In particular, the ubiquity in FLP chemistry of very strong, air-sensitive, Lewis acids, such as B(C6F5)3 (1 a) and derivatives thereof, has significantly limited the use of donor solvents, such as ethers, which tend to form strong classical donor–acceptor adducts. For many FLPs this coordination is followed by nucleophilic cleavage of the activated C=O bond (Scheme 1). In particular, ring-opening of THF was one of the first reported FLP-mediated transformations, and as such is often viewed as an archetypal FLP reaction.[4c] Consequently, only a few explicit reports exist of H2 activation by FLPs in donor-solvent media, all of which were based on stoichiometric phosphine or amine bases, and none of which described any subsequent catalytic hydrogenation reactivity.[8]

Scheme 1.

Recent work has shown that near-stoichiometric mixtures of 1 a (Figure 1) and specific ethers (Et2O, crown ethers) are capable of acting as hydrogenation catalysts in non-donor solvents, such as CD2Cl2, neatly demonstrating that such ethers are not fundamentally incompatible with FLP H2 activation chemistry.[9] Meanwhile, Paradies and co-workers have reported use of the THF adduct of B(2,6-F2C6H3)3 as a convenient source of the borane for certain P/B and N/B FLP-catalyzed hydrogenations.[10] These results led us to speculate that, with an appropriate Lewis acid, not only should FLP-mediated hydrogenation be possible in stronger donor ethereal solvents, but such solvents might remove the need for an additional “frustrated” Lewis base, by performing that role themselves.

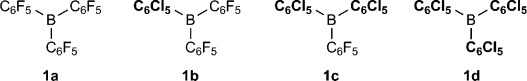

Figure 1.

Boranes 1 a–1 d, studied for hydrogenation efficacy in THF solvent.

The use of reaction media other than hydrocarbons and chlorinated solvents is inherently appealing; the low polarity of the hydrocarbons limits their effectiveness at solubilizing many potential polar substrates (εPhMe=2.38, c.f. εTHF=7.52, εDCM=8.93),[11] while chlorinated solvents have become increasingly unattractive as chemists become more concerned about the ‘greenness’ of their reactions.[12]

Previously, we have investigated the extremely hindered boranes B(C6Cl5)x(C6F5)3−x (x=1–3, Figure 1) and found that although electrophilicity increases with the number of perchlorophenyl groups, Lewis acidity decreases as a result of increasing steric hindrance.[13] Significantly, and unlike 1 a, these boranes were also found to demonstrate appreciable stability to air and moisture. Herein we describe investigations into the behavior of this family of boranes in the donor-solvent THF, and report the ability of such solutions to effectively catalyze the hydrogenation of even weakly basic substrates, using an operationally simple method that does not require the addition of an auxiliary Lewis base.

Although 1 a binds strongly to THF, we envisioned that the strength of this interaction might be reduced by increasing steric bulk. Rational modification of the Lewis acid has been shown to lead to improved functional-group tolerance in FLP-catalyzed hydrogenation reactions.[10], [14] Thus B(C6Cl5)(C6F5)2 (1 b), though more electrophilic than 1 a,[13] is found to bind the solvent only weakly when dissolved in neat THF. The reversibility of the binding is clear from variable-temperature (VT) NMR analysis of THF solutions of 1 b; below 0 °C the 11B NMR shift remains constant at δ=3.8 ppm, consistent with the four-coordinate 1 b⋅THF adduct (c.f. δ=3.3 ppm for 1 a⋅THF in CD2Cl2).[15] Upon warming, however, the resonance signal moves progressively downfield, reaching δ=23.9 ppm at 60 °C, indicative of a shift in the equilibrium towards free, uncoordinated 1 b (c.f. δ=63.6 ppm for free 1 b in PhMe, see Supporting Information). A similar trend is observed in the 19F NMR spectrum over the same temperature range, with the para fluorine resonance signal shifting from δ=−158.0 ppm at 0 °C (Δδm,p=7.1 ppm) to δ=−153.3 ppm (Δδm,p=10.9 ppm) at 60 °C. The increased separation of the meta and para resonances is consistent with a move away from four-coordinate and towards three-coordinate boron (c.f. Δδm,p=18.3 ppm for 1 b in PhMe).[16] Based on these results the 1 b/THF system can be considered to be on the borderline between a classical and a frustrated Lewis pair.[17]

THF solutions of B(C6Cl5)2(C6F5) (1 c), which is bulkier still, show no sign of coordination at all at room temperature (11B δ=63.5 ppm, c.f. δ=64.1 ppm in PhMe). Only upon cooling to −40 °C do signals consistent with a THF adduct become apparent in the 19F NMR (see Supporting Information). We observed no evidence for adduct formation with B(C6Cl5)3 (1 d) in THF between −100 °C and 60 °C.

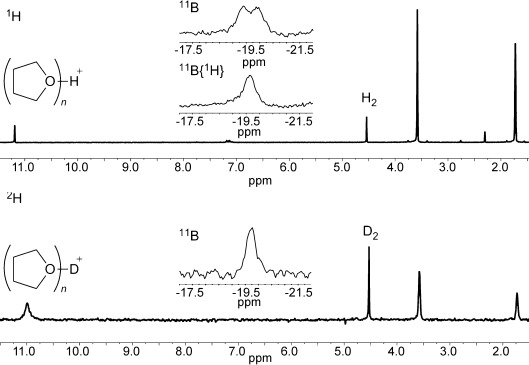

Admission of H2 (4 bar) to a THF solution of 1 b at room temperature leads to immediate appearance of a resonance signal at δ=11.19 ppm in the 1H NMR spectrum. Upon cooling to −25 °C a new doublet (singlet in the 1H-decoupled spectrum) can also be resolved at δ=−19.6 ppm in the 11B NMR spectrum (J=90 Hz). The 11B NMR data is consistent with previous reports of the borohydride anion [1 b⋅H]−,[18] while the new 1H NMR resonance lies within the range reported for protonated THF.[19] These results are therefore consistent with reversible H2 activation by an FLP-type mechanism, with THF acting as the Lewis base (Scheme 2 a).[20] Although no resonance signals attributable to [1 b⋅H]− are apparent in the 1H NMR spectrum, this can be attributed to line broadening as a result of the quadrupolar 10B/11B nuclei, in addition to broadening arising from dynamic dihydrogen bonding, which may be expected in the Brønsted acidic medium.[18], [21] The possibility that [1 b⋅H]− is formed instead as a result of hydride abstraction from the solvent can be discounted based on the observation of the 11B borohydride resonance signal as a doublet in both proteo and deutero THF, as well as the lack of any reaction in the absence of H2 (Scheme 2 b). Conclusive evidence is provided by using D2 in place of H2, which replaces the 11B doublet at δ=−19.6 ppm with a singlet at the same shift, and a comparable signal in the 2H spectrum diagnostic of [THF-D]+, or a solvate thereof (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

1H and 2H NMR spectra of 1 b in [D8]THF under H2, and in proteo THF under D2, respectively (inset: 11B and 11B {1H} spectra at −25 °C).

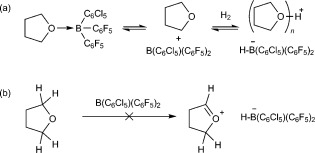

Scheme 2.

a) Reversible H2 activation by B(C6Cl5)(C6F5)2 in THF and b) potential hydride abstraction from THF, which is not observed.

Further evidence for H2 activation is provided by THF solutions of B(C6Cl5)3 (1 d). After heating to 60 °C for 1 h under H2 (4 bar), new resonance signals can clearly be observed at δ=11.34 ppm and δ=−8.7 ppm (d, J=91 Hz)[8c] in the room temperature 1H and 11B NMR spectra, respectively.

Clearly H2 activation in this manner generates a substantially acidic proton (the pKa of protonated THF has been measured as −2.05 in aqueous H2SO4).[22] Strong Brønsted acids can initiate polymerization of THF,[19b,c] as can strong Lewis acids, including 1 a.[23] Nevertheless, during the course of our studies no evidence for borane or proton-catalyzed polymerization of THF was detected for solutions of 1 a–d under H2, even after prolonged heating.[24] Nor, during our subsequent investigations into catalytic hydrogenation, was any FLP-mediated ring-opening of the solvent observed, even in the presence of relatively basic imines.

1 a has been shown to catalyze the hydrogenation of bulky imines in PhMe through a FLP mechanism.[25] However, since the reaction relies on the substrate to act as the frustrated Lewis base for initial H2 activation, it works relatively poorly for less electron-rich, and hence less basic, imines. The bulky electron-deficient N-tosyl imine 2 a, for example, was reported to require forcing conditions, in particular high H2 pressures, to achieve appreciable conversion (Table 1, entries 1 and 2).

Table 1.

FLP-mediated hydrogenation of imines.

| Entry | Substrate | Solvent | T [°C] | [B] (mol %) | t [h] | Yield [%][a] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1[bc] | 2 a | C7H8 | 80 | 1 a (10) | 22 | 7 |

| 2[bd] | 2 a | C7H8 | 80 | 1 a (10) | 22 | 99 |

| 3 | 2 a | [D8]THF | 60 | 1 b (5) | 3 | >99 (98)[e] |

| 4 | 2 b | [D8]THF | 60 | 1 b (5) | 3 | >99 |

| 5 | 2 a | THF | 60 | 1 b (5) | 3 | >99[f] |

| 6 | 2 c | [D8]THF | 60 | 1 b (5) | 8 | >99 (99)[e] |

| 7 | 2 d | [D8]THF | 80 | 1 b (5) | 18 | 71 |

| 8 | 2 e | [D8]THF | 60 | 1 b (15) | 8 | 91 |

| 9 | 2 a | C7D8 | 60 | 1 b (5) | 3 | 0 |

| 10 | 2 b | C7D8 | 60 | 1 b (5) | 3 | 0 |

| 11 | 2 c | C7D8 | 60 | 1 b (5) | 8 | 0 |

| 12 | 2 d | C7D8 | 80 | 1 b (5) | 18 | 79 |

| 13 | 2 e | C7D8 | 60 | 1 b (15) | 8 | 26 |

| 14 | 2 a | Dioxane | 60 | 1 b (5) | 41 | 96 |

| 15 | 2 a | [D8]THF | 60 | 1 c (5) | 72 | 90 |

| 16 | 2 a | [D8]THF | 80 | 1 a (10) | 72 | 84 |

| 17 | 2 a | [D8]THF | 80 | 1 d (5) | 72 | 0 |

Yields measured by in situ 1H NMR spectroscopy, using 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene in C6D6 in a capillary insert as an internal integration standard.

Result reported by Klankermayer and Chen.[25a]

10 bar H2.

30 bar H2.

Number in parentheses is yield isolated after increasing to 1 mmol scale (see Supporting Information).

Initial reaction mixture prepared using pre-dried solvent under air (see Supporting Information).

In contrast, the same imine was rapidly reduced in the presence of 1 b in [D8]THF under much milder conditions (5 mol % 1 b, 60 °C, 4 bar H2, 3 h), as was the related substrate 2 b (Table 1, entries 3 and 4). Furthermore, the air-stability of 1 b meant the initial reaction mixture could be conveniently prepared under air using pre-dried solvent, without the need for use of a glovebox (Table 1, entry 5). In addition to 2 a and 2 b the bulky N-aryl imines 2 c and 2 d were also successfully reduced (Table 1, entries 6 and 7), as was the less bulky N-aryl imine 2 e, although in this final case slightly higher catalyst loadings were necessary to achieve complete conversion, owing to reversible binding of 1 b to the product 3 e (Table 1, entry 8).

Notably, when the hydrogenation experiments were repeated in a non-basic solvent (C7D8) rather than in [D8]THF, under otherwise identical conditions, the weakly basic substrates 2 a and 2 b showed no evidence of hydrogenation (Table 1, entries 9 and 10). Conversely, the relatively basic imines 2 d and 2 e both show appreciable conversions in C7D8 (Table 1, entries 12 and 13). This divergent reactivity is consistent with hydrogenation occurring by two distinct mechanisms. In the first, H2 activation by 1 b/THF is followed by sequential proton and hydride transfer to generate the product amine (Scheme 3, route a). In the second mechanism, H2 is activated instead by a 1 b/substrate FLP in the manner described by Stephan et al., with subsequent transfer of hydride to the protonated imine (Scheme 3, route b).[25b] The reduction of 2 d and 2 e in non-donor solvent (C7D8) clearly demonstrates the feasibility of the route b mechanism. By contrast the lack of reactivity for the more weakly basic substrates 2 a and 2 b in C7D8, suggests that their reduction in THF occurs solely by solvent-mediated hydrogen activation. The different reactivity is consistent with other observations and can be understood intuitively: H2 activation using the substrate as the frustrated Lewis base will become less favorable as the substrate becomes less basic. However, the high Brønsted acidity of protonated THF allows for levelling even to relatively electron-poor substrates. Interestingly, 2 c also fails to undergo hydrogenation in C7D8, despite being of similar basicity to 2 e (Table 1, entry 11). In this case steric shielding of the basic nitrogen atom presumably inhibits direct H2 activation.

Scheme 3.

Proposed mechanisms for hydrogenation of imines by activation of H2 using either a) THF solvent or b) substrate as a frustrated Lewis base.

The hydrogenation mechanism (route a), where H2 activation is mediated by the Lewis acid and the solvent, is also feasible for other ethereal solvents. Solutions of 1 b in 1,4-dioxane catalyze the hydrogenation of 2 d under identical conditions to solutions in [D8]THF, albeit more slowly (Table 1, entry 14). The lower rate is consistent with the lower basicity of 1,4-dioxane (pKaH=−2.92 in aqueous H2SO4),[22], [26] but may also partially be attributed to its reduced polarity relative to THF (εdioxane=2.22, εTHF=7.52),[11] which will make cleavage of H2 into ionic H+/H− adducts less favorable (Scheme 3, route a). Some variation of the borane is also tolerated: use of 1 c leads to a reduction in reaction rate, but otherwise only a minor change in outcome (Table 1, entry 15). In fact, even 1 a is observed to effectively catalyze hydrogenation at slightly higher temperatures (Table 1, entry 16); clearly under these conditions, coordination of THF is sufficiently reversible to allow some H2 activation to occur. No reaction is observed with 1 d, suggesting [1 d⋅H]− to be a much poorer hydride donor. Given that 11B NMR spectroscopic analysis suggests the equilibrium between 1 d and [1 d⋅H]− under H2 favors 1 d, this lack of reactivity is most likely due to kinetic (steric) rather than thermodynamic factors (Table 1, entry 17).

Given the success of 1 b as a hydrogenation catalyst for electron-poor imines we were interested in its ability to effect hydrogenation of other weakly basic substrates. To date the only reported example of FLP-mediated hydrogenation of a weakly basic aromatic heterocycle describes the reduction of indoles under very high pressures of H2.[2] Nevertheless, admission of just 5 bar H2 to a mixture of 1 b and N-methyl pyrrole (4 a) or 2,5-dimethylpyrrole (4 b) in THF led to formation of the reduced species [5⋅H]+[1 b⋅H]− (Scheme 4). No catalytic turnover was observed due to the relatively low acidity of the pyrrolidinium borohydride products (although it should be noted that the reduction of the pyrroles 4 to the corresponding pyrrolidines, 5, does require the use of two equivalents of H2). Similar limitations have been reported for the FLP-mediated hydrogenation of anilines to much more basic cyclohexylamines.[27]

Scheme 4.

B(C6Cl5)(C6F5)2-mediated hydrogenations performed in [D8]THF.

It was anticipated that the use of furans instead of pyrroles might lead to superior results; the substituted tetrahydrofuran products ought to be no more basic than the solvent, and so should not prevent catalytic turnover. Indeed, although attempts to hydrogenate furan itself were unsuccessful, several more electron-rich methyl-substituted furans, 6, did undergo catalytic hydrogenation (Scheme 4), despite the fact that such compounds are extremely weak bases.[28] This represents the first reported example of FLP-catalyzed hydrogenation of aromatic O-heterocyclic rings, and nicely demonstrates the value of the borane/solvent systems described. In addition to these novel results, attempts to reduce compounds from a variety of previously-studied substrate classes were also successful, under similar conditions (Scheme 4).[1b,c]

In conclusion, we have shown that THF solutions of boranes 1 are capable of effecting H2 activation in the absence of any additional Lewis base. Solutions of 1 b in particular are effective catalysts for the metal-free hydrogenation of a variety of substrates by a solvent-assisted mechanism. Compound 1 b shows appreciable stability in air, which further increases the practicality of this system relative to the 1 a-derived alternatives.

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/anie.201405531.

References

- [1].pp. 1124–1126.

- [1a].Welch GC, Juan RRS, Masuda JD, Stephan DW. Science. 314 [Google Scholar]

- [1b].Paradies J. Synlett. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- [1c].Hounjet LJ, Stephan DW. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2013;18 653 Also relevant to this field is earlier work on B(C F -catalyzed hydrosilylation. See: [Google Scholar]

- [1d].Parks DJ, Piers WE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;118 [Google Scholar]

- [1e].Parks DJ, Blackwell JM, Piers WE. J. Org. Chem. 1996;65 doi: 10.1021/jo991828a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [1f].Blackwell JM, Sonmor ER, Scoccitti T, Piers WE. Org. Lett. 2000;2 doi: 10.1021/ol006695q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [1g].Piers WE, Marwitz AJV, Mercier LG. Inorg. Chem. 2000;50 doi: 10.1021/ic2006474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Stephan DW, Greenberg S, Graham TW, Chase P, Hastie JJ, Geier SJ, Farrell JM, Brown CC, Heiden ZM, Welch GC, Ullrich M. Inorg. Chem. 2011;50:12338–12348. doi: 10.1021/ic200663v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].pp. 10311–10315.

- [3a].Greb L, Ona-Burgos P, Schirmer B, Grimme S, Stephan DW, Paradies J. Angew. Chem. 124 doi: 10.1002/anie.201204007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51 [Google Scholar]

- [3b].Segawa Y, Stephan DW. Chem. Commun. 2012;48 doi: 10.1039/c2cc37190a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].pp. 5310–5319.

- [4a].Birkmann B, Voss T, Geier SJ, Ullrich M, Kehr G, Erker G, Stephan DW. Organometallics. 29 [Google Scholar]

- [4b].Chapman AM, Haddow MF, Wass DF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;133 doi: 10.1021/ja207936p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4c].Welch GC, Masuda JD, Stephan DW. Inorg. Chem. 2011;45 doi: 10.1021/ic051713r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4d].Holschumacher D, Bannenberg T, Hrib CG, Jones PG, Tamm M. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;47 doi: 10.1002/anie.200802705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2008;120 [Google Scholar]

- [5].pp. 12280–12289.

- [5a].Mömming CM, Froemel S, Kehr G, Froehlich R, Grimme S, Erker G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131 doi: 10.1021/ja903511s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5b].Mömming CM, Kehr G, Wibbeling B, Froehlich R, Erker G. Dalton Trans. 2009;39 doi: 10.1039/c0dt00015a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5c].Moebs-Sanchez S, Bouhadir G, Saffon N, Maron L, Bourissou D. Chem. Commun. 2010;29 doi: 10.1039/b805161e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5d].Uhl W, Appelt C. Organometallics. 2008;32 [Google Scholar]

- [6].pp. 126–132.

- [6a].Tran SD, Tronic TA, Kaminsky W, Heinekey DM, Mayer JM. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 369 [Google Scholar]

- [6b].Chakraborty D, Chen EYX. Macromolecules. 2011;35 [Google Scholar]

- [7].pp. 7433–7437.

- [7a].Chase PA, Stephan DW. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47 [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2008;120 [Google Scholar]

- [8].pp. 9019–9022.

- [8a].Herrington TJ, Thom AJW, White AJP, Ashley AE. Dalton Trans. 41 doi: 10.1039/c2dt30384a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8b].Lu Z, Cheng Z, Chen Z, Weng L, Li ZH, Wang H. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;50 doi: 10.1002/anie.201104999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2011;123 [Google Scholar]

- [8c].Travis AL, Binding SC, Zaher H, Arnold TAQ, Buffet JC, O’Hare D. Dalton Trans. 2011;42 doi: 10.1039/c2dt32525j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Hounjet LJ, Bannwarth C, Garon CN, Caputo CB, Grimme S, Stephan DW. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52:7492–7495. doi: 10.1002/anie.201303166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2013;125 [Google Scholar]

- [10].Greb L, Daniliuc CG, Bergander K, Paradies J. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52:5876–5879. doi: 10.1002/anie.201210175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2013;125 [Google Scholar]

- [11].Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. 94ed. Boca Raton: CRC; 2013. (Ed.: th ed. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Alfonsi K, Colberg J, Dunn PJ, Fevig T, Jennings S, Johnson TA, Kleine HP, Knight C, Nagy MA, Perry DA, Stefaniak M. Green Chem. 2008;10:31–36. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ashley AE, Herrington TJ, Wildgoose GG, Zaher H, Thompson AL, Rees NH, Kraemer T, O’Hare D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:14727–14740. doi: 10.1021/ja205037t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].pp. 6559–6563.

- [14a].Erős G, Mehdi H, Pápai I, Rokob TA, Király P, Tárkányi G, Soós T. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49 doi: 10.1002/anie.201001518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2010;122 [Google Scholar]

- [14b].Erős G, Nagy K, Mehdi H, Pápai I, Nagy P, Király P, Tárkányi G, Soós T. Chem. Eur. J. 2010;18 doi: 10.1002/chem.201102438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Lorber C, Choukroun R, Vendier L. Organometallics. 2008;27:5017–5024. [Google Scholar]

- [16].pp. 218–225.

- [16a].Massey AG, Park AJ. J. Organomet. Chem. 5 [Google Scholar]

- [16b].Horton AD, de With J, van der Linden AJ, van de Weg H. Organometallics. 1966;15 [Google Scholar]

- [16c].Horton AD, de With J. Chem. Commun. 1996 [Google Scholar]

- [17].Because the limiting 19111 b1 b. F or B resonance signals of free in THF are not known, it is unfortunately not possible to extract thermodynamic activation parameters for the reversible binding of THF to from these spectra.

- [18].Zaher H, Ashley AE, Irwin M, Thompson AL, Gutmann MJ, Kramer T, O’Hare D. Chem. Commun. 2013;49:9755–9757. doi: 10.1039/c3cc45889j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].pp. 1121–1126.

- [19a].Olah GA, Szilagyi PJ. J. Org. Chem. 36 [Google Scholar]

- [19b].Pruckmayr G, Wu TK. Macromolecules. 1971;11 [Google Scholar]

- [19c].Pruckmayr G, Wu TK. Macromolecules. 1978;6 [Google Scholar]

- [20].Although the number of THF molcules coordinated to the proton has not been determined, a coordination number of two would be consistent with previous observations.[9] Krossing I, Reisinger A. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2005:1979–1989. See also:, and references therein. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Schulz F, Sumerin V, Heikkinen S, Pedersen B, Wang C, Atsumi M, Leskelä M, Repo T, Pyykkö P, Petry W, Rieger B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:20245–20257. doi: 10.1021/ja206394w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Arnett E, Wu CY. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1960;82:4999–5000. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Chivers T, Schatte G. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2003:3314–3317. [Google Scholar]

- [24].In fact, it appears that the presence of an atmosphere of H21 a. inhibits polymerization of THF by (see Supporting Information)

- [25].pp. 2130–2131.

- [25a].Chen D, Klankermayer J. Chem. Commun [Google Scholar]

- [25b].Chase PA, Jurca T, Stephan DW. Chem. Commun. 2008 doi: 10.1039/b718598g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].pKa. Greb L, Tussing S, Schirmer B, Oña-Burgos P, Kaupmees K, Lõkov M, Leito I, Grimme S, Paradies J. Chem. Sci. 2013;4:2788–2796. differences of this magnitude have been shown to significantly affect the rate of alkene hydrogenation by FLP catalysts based on weakly basic phosphines. See: [Google Scholar]

- [27].Mahdi T, Heiden ZM, Grimme S, Stephan DW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:4088–4091. doi: 10.1021/ja300228a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Carmody MP, Cook MJ, Tack RD. Tetrahedron. 1976;32:1767–1771. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.