Spatial associations with abstract concepts--such as thinking of future events as occurring in a forward direction (Boroditsky, 2000), power as ascending vertically (Schubert, 2005), or numbers as increasing from left-to-right (Hubbard et al., 2005)--permeate our mental life. Today, research in developmental psychology is beginning to shed new light on where these associations come from, how they change over time, and what functions they might serve.

In this review, we examine the development of spatial-numerical associations (SNAs), that is, how the parts of the mind that underlie spatial and numerical ability interact throughout development. A central question surrounding the development of SNAs concerns the role of experience in shaping the mental number line. On one side is the theory that brain networks specialized for space and number are intertwined at birth; experience, in this view, differentiates these streams of information. One version of this view is Walsh’s (2003) A Theory of Magnitude, in which space, time, and number are represented at birth by a single system that calculates a generic sense of quantity, or “how much” (rather than discrete number per se). The competing theory proposes that representations of space and number are distinct at birth and related throughout development; experience, in this view, integrates these streams of information by highlighting the underlying similarity of space and number through repeated exposure, linguistic prompts, and motor plans (for a review, see Lourenco & Longo, 2011).

These two theories lead to quite different expectations about the course of development. If experience creates spatial-numeric associations, we should find that young children (ideally newborns, a population with minimal experience in the world) harbor no expectations about whether numeric value is linked to spatial extent, or a particular spatial direction (e.g., leftward vs. rightward), or some combination of the two. On the other hand, if spatial-numeric associations exist because space and number are not initially differentiated, it should be possible to find very young children with symmetric expectations about space and number (i.e., that spatial extent, direction, or their combination predicts numeric value as well as the opposite) and who appear to generalize about one space-number pairing to another space-number pairing.

INNATE MECHANISMS LINKING SPACE AND NON-SYMBOLIC NUMBER

Might the links between space and number develop from the innate design characteristics of the brain? Evidence addressing this question comes from a wide array of sources, including behavioral research on learning biases in human infants, neural recordings of non-human primates, and studies of animals reared without previous visual experience.

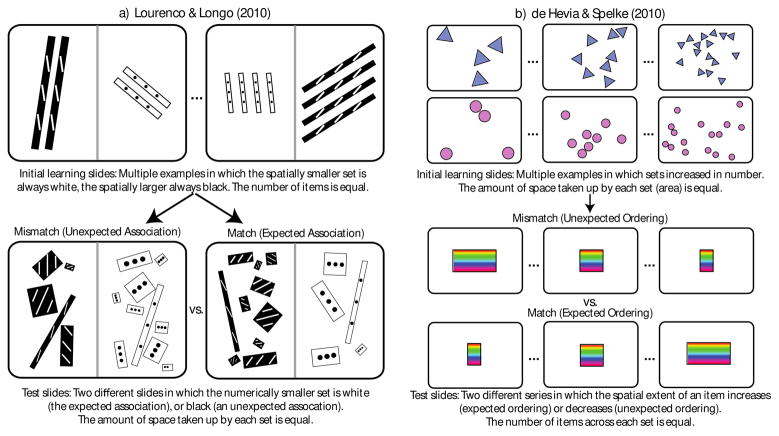

First, do human infants spontaneously relate spatial and numerical dimensions? To address this issue, Lourenco and Longo (2010) taught 9-month-olds an arbitrary rule across either a spatial or numerical dimension to discover whether they spontaneously applied the rule to the other (untrained) dimension (Fig. 1a). For example, infants were trained with the rule that objects in two different number arrays – such as 2 and 4 – had unique characteristics: the less-numerous set was always white and the more-numerous set always black. Infants easily learned this rule and generalized it to a new set of numerical arrays (e.g., 5 and 10), thus looking longer during test if the rule had been violated (e.g., if the less-numerous set was black and the more-numerous white). More intriguingly, infants made this generalization to sets of a new size as well. Shown a test slide that had two sets of two objects, infants expected the previous rule to hold, looking longer if the set that had a smaller overall size was black and the larger-sized set was white. Another group of infants exhibited similar prowess at this task when the learning dimension was size-based, and the testing dimension number-based. Thus, infants applied a learned rule involving “more-than” and “less-than” across spatial and numerical dimensions symmetrically, even when trained in only one dimension.

Figure 1.

Schematic of habituation and test stimuli used by a) Lourenco and Longo (2010) and b) de Hevia and Spelke (2010) to demonstrate early preverbal spontaneous associations between spatial and numerical representations in infants.

If infants spontaneously relate number and size, how do they relate number to other spatial dimensions (such as length) and non-spatial dimensions (such as brightness)? To address this, de Hevia and Spelke (2010) showed 8-month-olds slides depicting an increasing or decreasing number of objects (e.g., a set of circles that increased in number). As infants watched these slides, their looking times decreased – a process referred to as habituation – and they were then shown test slides of a spatial stimulus (a line) that either increased or decreased in length (Fig. 1b). Infants who were initially exposed to increasing number looked longer to test slides of a shrinking line, whereas infants who habituated to decreasing number looked longer to a growing line. More importantly, the infants could readily learn a consistent positive relation between number and line length, but could not learn a negative relation. Indeed, when infants were shown slides of a positive relation between numerical and spatial quantity (e.g., numerous arrays paired with long lines), infants spontaneously preferred positive spatial-numeric pairings over negative pairings (e.g., long lines paired with sparse arrays: Fig. 1). In a series of follow-up studies, de Hevia and Spelke (2013) found that while infants could learn number-brightness relations if shown repeated pairings, this link was more tenuous than that of number to space: they did not spontaneously relate ‘more’ to ‘brighter’, and there was not the clear distinction between the enhanced learning of positive compared to inverse relations found with number-space pairings. Recent work by de Hevia et al. (2014) has established that even newborns are selectively sensitive to positive relationships between space and number. Thus we see that infants not only can learn spatial-numeric associations, but already prefer “numerically larger goes with spatially larger” to “numerically larger goes with spatially smaller”, and do so preferentially to spatial dimensions. Intriguingly, preschoolers’ abilities to link space and number seem no more flexible than those of infants. de Hevia, Vanderslice, and Spelke (2012) found that preschoolers also reliably matched number and space (e.g., less-numerous arrays with shorter lines, and more-numerous arrays with longer lines), although they failed to do so when stimuli exhibited a negative relation. Further, these preschoolers also failed to match number with another continuous dimension, brightness.

Together, the pattern that emerges from these studies is one in which newborns, infants and very young children spontaneously associate spatial and numerical information, but this pairing is biased in a manner consistent with a number line, wherein the space between two numbers increases with their difference in value. Infants’ first bias is for spatial magnitude; number and space are more readily associated than number and brightness. Infants’ second bias is for preserving congruent magnitude; infants more readily learn to associate ‘more’ with ‘more’ and ‘less’ with ‘less’ than they can learn to associate ‘more’ with ‘less’. Because it is difficult to explain newborns’ biases as a result of experience with the world, these results are consistent with a developmental trajectory in which space and number are integrated at birth and become distinct. On the other hand, direct evidence for the proposed unfolding of this differentiation account is lacking. For example, no evidence exists that experience makes it more difficult for children to transfer from space to number (or vice versa) – a testable prediction from this theory.

What mechanisms might link space and number in newborns? Insights from studies of animal learning shed light on this question. In one such study, Tudusciuc and Nieder (2007) required monkeys to indicate whether two line lengths or numerical magnitudes matched, and they recorded the electrical activity of 400 single brain cells in and around the primate version of the intraparietal sulcus (a brain region that in humans encodes both symbolic and non-symbolic number). The authors found three distinct types of neurons in this region: neurons that encoded number exclusively, neurons that encoded space exclusively, and neurons that encoded both space and number. These results yield an existence proof that, for species along the same limb of the evolutionary tree as humans, space and number share a common neural code, but leave open the possible role of experience in linking them.

Studies of dark-reared newborn chicks address the role of experience more directly (Rugani et al., 2010), though they speak to the relation of number to spatial position rather than spatial extent. During a training phase, hatchlings were shown 16 containers extending vertically in front of them, and reinforced with food at the 4th or 6th container. At test, the experimenters rotated the line of containers by 90°, into a horizontal line, and measured where the hatchlings pecked. Remarkably, the birds exhibited a clear preference to peck at the 4th and 6th location from the left, indicating a) an ability to approximately encode 4 and 6 items, and b) a preference for asymmetric encoding of the order of items starting with the left side of space. These results are not a quirk of the avian brain; monkeys given a similar task show a similar preference for encoding number starting with the left side of space (Drucker & Brannon, 2014), and chimpanzees trained to order the Arabic numerals 1–9 also show a spontaneous preference for 9 appearing on the right and 1 appearing on the left (Adachi, 2014). These findings are suggestive of a spontaneous and unlearned link between spatial extent and number, as well as spatial location and numeric order, although whether humans inherit these links is not addressed in these studies.

INFLUENCE OF MOTOR BEHAVIOR IN REFINING SPATIAL-NUMERICAL ASSOCIATIONS

In addition to evidence for innate mechanisms linking space and number, there is also growing evidence that children’s motor behavior refines their pre-existing spatial-numeric associations. For example, while infants seem to expect number and space to be congruently associated, mappings between number and space become more linear (rather than logarithmic) with age and experience (Siegler & Opfer, 2003). One reason motor behavior might refine spatial-numeric associations in this way is that control of motor behavior (e.g., picking up a full versus empty suitcase) requires a quantitative calibration of distinct magnitudes, one of which is potentially spatial and the other numerical.

A good illustration of this potential benefit comes from Fischer et al. (2011). They found that kindergarteners’ ability to estimate the positions of numbers on number lines benefited more from practice using full-body movement on a physical number line than from practice using a similar, computer-based number line. Another example of this physical link between space and number is the finger-counting behavior observed in very young children. Theoretically, the one-to-one correspondence between fingers and objects in a set may act as a useful tool to map something symbolic (a list of number words) to something non-symbolic (an array of physical objects or fingers). Although an influential relationship between the hands and mathematical skills exists in adulthood (“manumerical cognition”; Fischer & Brugger, 2011), more developmental data is needed to determine whether finger counting causes SNAs. If anything, research on early finger counting finds children start with small numbers on their right hand (due to dominant handedness: Sato & Lalain, 2008; for a review see Previtali et al., 2011).

The visual system is sometimes proposed as yet another ‘embodied’ route through which SNAs develop, and there are several noted interactions between the visual system and SNAs in adulthood. For example, adults asked to randomly generate numbers will look left when they provide small numbers, and right for large numbers (Loetscher et al., 2010), and the part of the brain that is active when making horizontal eye movements – as if along a number line - is recruited when calculating outcomes to addition or subtraction problems (Knops et al., 2009). By preschool, children comparing numbers respond more quickly to small numbers appearing on the left side of their visual field and large numbers appearing on the right side than the reverse (Patro & Haman, 2012). Certain types of visual attention are linked to SNAs by the time children enter into formal arithmetic instruction; Knops et al. (2013) found that 6- and 7-year-olds who are more proficient at switching their attention from an irrelevant to a relevant location exhibited more adult-like SNAs.

Could the developing visual system act as an interface between spatial and numerical representations in childhood, especially with respect to the lateralization of SNAs into a conventional number line (e.g., small=left, large=right)? Perhaps most telling is work on visually-impaired individuals; some types of SNAs are not obtained by the same age as in sighted individuals (Bachot et al. 2005). However, Crollen et al. (2013) found that early-blind individuals still possess SNAs, although they mapped numbers to their personal space (e.g., associated small numbers with their left hand, even when that left hand was crossed to their right side) instead of external space (e.g., small numbers with the left side of their visual field, as sighted adults do). This suggests that damage to the visual system in development alters the nature and timeline of SNAs, but not their overall presence.

INFLUENCE OF CULTURAL ACTIVITY IN LINKING SPACE TO SYMBOLIC NUMBER

A final influence on the development of SNAs is the culturally-specific experience that children encounter at home and in school. Indeed, the first explanations of SNAs were cultural, pointing to late-developing and increasingly automatized reading and writing behaviors as the founding link between spatial and numerical processing. Dehaene et al.’s (1993) seminal set of experiments on SNAs in adulthood found that length of time spent in a Westernized society correlated with the degree to which the mental number line was oriented in a left-to-right fashion, leading the authors to speculate that SNAs were determined by the direction of writing. In another study, Berch et al. (1999) found that a classic form of SNAs was late-emerging (around 9 years) and interpreted this finding as reflective of formal schooling practices. Moreover, illiterate populations do not show classic forms of SNAs (Shaki et al., 2012; Zebian, 2005).

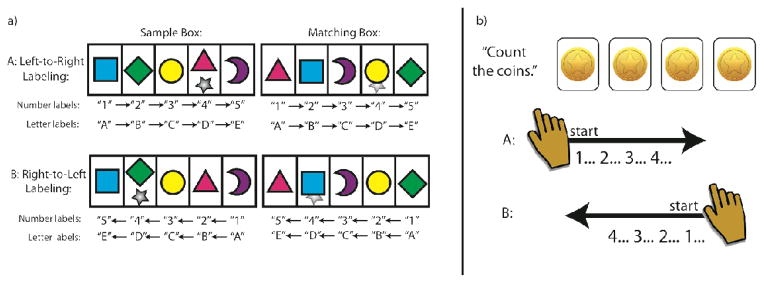

One problem for the idea that spatial-numeric associations come from reading practice is that even pre-reading preschoolers show spatial-numerical associations (Opfer et al., 2010). For example, when searching for an object in the 4th of 5 compartments, preschoolers were faster and more accurate when the compartments had been labeled from left-to-right than labeled from right-to-left (Fig. 2a: McCrink et al., 2014; Opfer et al., 2010). Further, this benefit was mediated not by sensitivity to reading direction, but by children’s counting behavior; those who spontaneously counted objects in a left-to-right manner were most likely to benefit when presented with left-to-right labels (Opfer & Furlong, 2011).

Figure 2.

Examples of paradigms used to assess different types of spatial-numerical associations in early childhood. a) Schematic from a task used in Opfer et al. (2010; and Opfer & Furlong [2011]) and adapted by McCrink et al. (2014). Preschoolers hear several marked spatial compartments labeled numerically or alphabetically. They are then shown a prize hidden in one of the compartments of the sample box, and asked to retrieve it from the matching box. U.S. preschoolers, especially those who count from left-to-right, perform better when labels are left-to-right (Panel A). Israeli preschoolers perform the task better when the labels are presented right-to-left (Panel B). b) Schematic of task in Shaki et al. (2012) and Opfer et al. (2010). When asked to count an array, preschoolers in England and the USA do so from left-to-right (LR), as do Israeli preschoolers (Panel A). Preschoolers from Palestine counted from right-to-left (RL, Panel B). Post-schooling, children and adults whose cultures maintain consistent reading direction for numbers and letters (England, LR: Palestine, RL) exhibited the same counting direction. Israeli children and adults, whose culture reads letters RL and numbers LR, exhibit no counting direction preference post-schooling.

While directional biases in counting do appear before children learn to read and write, they are also impacted by schooling. In one study of British, Palestinian, and Israeli children and adults, Shaki et al. (2012: Fig. 2b) found that the youngest children in all groups counted with some directional preference, and this preference was later exacerbated or eliminated depending on the nature of their formal schooling. Preschoolers growing up in England, for example, preferred left-to-right counting, whereas those who grew up in Palestine and Israel counted from right-to-left. For both Palestinian `and British children, these counting patterns grew more prevalent after they entered into an educational system in which numbers and words were written in the same direction. However, Israeli children received a mixed message at the advent of schooling - numbers and words were read in differing directions. As a result, their counting shifted from directional to nondirectional.

Taken together, developmental research suggests that individual children-- like the dark-reared chicks in Rugani et al (2010)-- are highly likely to show directional biases in their SNAs, but these directional biases come to conform to cultural conventions (such as L-R in England, R-L in Palestine) due to cultural biases in pre-reading activities (such as counting) and reading habits as well. Still other sources of these biases may include exposure to linguistic metaphors (e.g., hearing “the winter is behind us”; Nuñez, 2011), though these influences remain to be tested.

CONCLUSIONS

From the earliest measurement tools, to the Cartesian coordinates of the plane, to the proof of Fermat’s Last Theorem, the history of mathematics has been advanced by links between space and number (Hubbard et al., 2005). The growth of mathematical knowledge in children as well is predicted by the ability to map numbers to space (Booth & Siegler, 2008; Gunderson et al., 2012), a finding that has led to successful interventions that train children on space-number relations (Ramani & Siegler, 2011).

In this review, we examined evidence on the origins of spatial-numeric associations, as well as their refinement with experience. Our review points to an early and potentially innate bias to encode number and space in an undifferentiated manner which makes the acquisition of a mental number line -- where number increases congruently with space -- probable, but (at least in humans) with no particular directional bias (e.g., associating small numbers with the left) and without space and number being associated linearly. Beyond these origins, motor activities (such as the finger and eye movements involved in counting) appear to calibrate spatial-numeric associations, but these activities differ among cultures, such that some count from right-to-left and others from left-to-right. Seen in this way, the development of SNAs reflects a pattern seen in many domains – evolution attunes expectations from birth, and enculturation exploits and shifts these expectations as children adapt to their cultural environment.

Contributor Information

Koleen McCrink, Barnard College, Columbia University.

John E. Opfer, The Ohio State University

References

- Adachi I. Spontaneous spatial mapping of learned sequence in chimpanzees: Evidence for a SNARC-like effect. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(3):e90373. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachot J, Gevers W, Fias W, Roeyers H. Number sense in children with visuospatial disabilities: Orientation of the mental number line. Psychology Science. 2005;47:172–183. [Google Scholar]

- Berch DB, Foley EJ, Hill RJ, Ryan PM. Extracting parity and magnitude from Arabic numerals: Developmental changes in number processing and mental representation. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 1999;74:286–308. doi: 10.1006/jecp.1999.2518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth JL, Siegler RS. Numerical magnitude representations influence arithmetic learning. Child Development. 2008;79:1016–1031. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boroditsky L. Metaphoric structuring: understanding time through spatial metaphors. Cognition. 2000;75:1–28. doi: 10.1016/s0010-0277(99)00073-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crollen V, Dormal G, Seron X, Lepore F, Collignon O. Embodied numbers: The role of vision in the development of number-space interactions. Cortex. 2013;49:276–283. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2011.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Hevia MD, Izard V, Coubart A, Spelke E, Streri A. Representations of space, time, and number in neonates. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2014 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323628111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Hevia MD, Spelke ES. Number-space mapping in human infants. Psychological Science. 2010;21:653–660. doi: 10.1177/0956797610366091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Hevia MD, Spelke ES. Not all continuous dimensions map equally: Number-brightness mapping in human infants. PLoS ONE. 2013;8 (11):e81241. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Hevia MD, Vanderslice M, Spelke ES. Cross-Dimensional Mapping of Number, Length and Brightness by Preschool Children. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(4):e35530. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehaene S, Bossini S, Giraux P. The mental representations of parity and number magnitude. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 1993;123:371–396. [Google Scholar]

- Drucker CB, Brannon EM. Rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) map number onto space. Cognition. 2014;132:57–67. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2014.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer MH, Brugger P. When digits help digits: Spatial-numerical associations point to finger counting as prime example of embodied cognition. Frontiers in Psychology. 2011;2:1–7. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer U, Moeller K, Bientzle M, Cress U, Nuerk HC. Sensori-motor spatial training of number magnitude representation. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review. 2011;18:177–183. doi: 10.3758/s13423-010-0031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson EA, Ramirez G, Beilock SL, Levine SC. The relation between spatial skill and early number knowledge: The role of the linear number line. Developmental Psychology. 2012;48:1229–1241. doi: 10.1037/a0027433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard EM, Piazza M, Pinel P, Dehaene S. Interactions between number and space in parietal cortex. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2005;6:435–448. doi: 10.1038/nrn1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knops A, Thirion B, Hubbard EM, Michel V, Dehaene S. Recruitment of an area involved in eye movements during mental arithmetic. Science. 2009;324:1583–1585. doi: 10.1126/science.1171599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knops A, Zitzmann S, McCrink K. Examining the presence and determinants of operational momentum in childhood. Frontiers in Psychology. 2013;4:325. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loetscher T, Bockisch C, Nicholls M, Brugger P. Eye position predicts what number you have in mind. Current Biology. 2010;20(6):R264–265. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lourenco SF, Longo MR. General magnitude representation in human infants. Psychological Science. 2010;21:873–881. doi: 10.1177/0956797610370158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lourenco SF, Longo MR. Origins and development of generalized magnitude representation. In: Dehaene S, Brannon E, editors. Space, time, and number in the brain: Searching for the foundations of mathematical thought. New York: Academic Press; 2011. pp. 225–244. [Google Scholar]

- McCrink K, Shaki S, Berkowitz T. Culturally driven biases in preschoolers’ spatial search strategies for ordinal and non-ordinal dimensions. Cognitive Development. 2014;30:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.cogdev.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunez R. No innate number line in the human brain. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2011;42:651–668. [Google Scholar]

- Opfer JE, Furlong EE. How numbers bias preschoolers’ spatial search. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2011;42:682–695. [Google Scholar]

- Opfer JE, Thompson CA, Furlong EE. Early development of spatial-numeric associations: Evidence from spatial and quantitative performance of preschoolers. Developmental Science. 2010;13:761–771. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2009.00934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patro K, Haman M. The spatial-numerical congruity effect in preschoolers. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2012;111:534–542. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Previtali P, Rinaldi L, Girelli L. Nature or nurture in finger counting: a review on the determinants of the direction of number-finger mapping. Frontiers in Psychology. 2011;2:363. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramani GB, Siegler RS. Playing linear numerical board games promotes low-income children’s numerical development. Developmental Science. 2011;11:655–661. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2008.00714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rugani R, Kelly DM, Szelest I, Regolin L, Vallortigara Is it only humans that count from left to right? Biology Letters. 2010;6:290–292. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2009.0960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato M, Lalain M. On the relationship between handedness and hand-digit mapping in finger counting. Cortex. 2008;44:393–399. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert T. Your highness: Vertical positions as perceptual symbols of power. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;89(1):1–21. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.89.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaki S, Fischer M, Gobel S. Direction counts: A comparative study of spatially directional counting biases in cultures with different reading directions. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2012;112(2):275–281. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegler RS, Opfer JE. The development of numerical estimation: Evidence for multiple representations of numerical quantity. Psychological Science. 2003;14:237–243. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.02438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tudusciuc O, Nieder A. Neuronal population coding of continuous and discrete quantity in the primate posterior parietal cortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2007;104:14513–14518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705495104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh V. A theory of magnitude: Common cortical metrics of time, space, and quantity. Trends in Cognitive Science. 2003;7:483–488. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zebian S. Linkages between number concepts, spatial thinking, and directionality of writing: the SNARC effect and the reverse SNARC effect in English and Arabic monoliterates, biliterates, and illiterate Arabic speakers. Journal of Cognition and Culture. 2005;5:165–190. [Google Scholar]