Abstract

Deficits in emotional clarity, the understanding and awareness of one’s own emotions and the ability to label them appropriately, are associated with increased depressive symptoms. Surprisingly, few studies have examined factors associated with reduction in emotional clarity for adolescents, such as depressed mood and ruminative response styles. The present study examined rumination as a potential mediator of the relationship between depressive symptoms and changes in emotional clarity, focusing on sex differences. Participants included 223 adolescents (51.60% female, Mean age = 12.39). Controlling for baseline levels of emotional clarity, initial depressive symptoms predicted decreases in emotional clarity. Further, rumination prospectively mediated the relationship between baseline depressive symptoms and follow-up emotional clarity for girls, but not boys. Findings suggest that depressive symptoms may increase girls’ tendencies to engage in repetitive, negative thinking, which may reduce the ability to understand and label emotions, a potentially cyclical process that confers vulnerability to future depression.

Keywords: emotional clarity, rumination, depression, adolescence

Adolescence is a unique time marked by rapid change, growth, and dramatic increases in depressive symptoms (Hankin, Mermelstein, Roesch, 2007). At the start of adolescence, depressive symptoms begin to increase, and they continue to develop throughout this period (Ge, Lorenz, Conger, Elder, & Simons, 1994). From ages 13 to 18, about 20% of adolescents will experience a depressive episode (Hankin et al., 1998) and others will have subclinical depressive symptoms that may lead to negative outcomes and impair functioning (Gotlib, Lewinsohn, & Seeley, 1995). Sex differences in depression also emerge during this time, in which females are more vulnerable to developing depression than their male peers (Hankin et al., 1998). Depression in cyclical in nature, such that depressive symptoms precede the onset of depressive episodes (van Lang, Ferdinand, & Verhulst, 2007), and depressive episodes predict subsequent bouts of depression over time (Gelenberg, 2010; Lewinsohn, Clarke, Seeley, & Rohde, 1994). Although much research has documented this building cycle of depression, the manner in which emotional and cognitive risk factors impact, and are impacted by, depression during adolescence is less clear (Abela & Hankin, 2008). Inasmuch as depression leads to many negative consequences, including interpersonal instability, academic problems, impaired cognitive and affective functioning, and future depression (Avenevoli, Knight, Kessler, & Merikangas, 2008), it is crucial to clarify how depressive symptoms may lead to impaired emotional experiences and whether negative cognitive strategies may impact this relationship.

One chief vulnerability and potential consequence of having high levels of depressed mood is the tendency to ruminate, or repetitively focus on the potential meaning, causes, and consequences of negative mood. According to the Response Styles Theory (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991), the way in which people respond to dysphoric mood can impact the severity and course of depressive symptoms. Rumination (i.e., repetitively focusing on the potential meaning, causes, and consequences of negative mood) can lead to many negative outcomes, including impaired problem solving, enhanced negative thinking, and increased depressive symptoms (Nolen-Hoeksema, Wisco, & Lyubomirsky, 2008). Past research indicates that responding to negative affect with rumination is a risk factor for the onset of a depressive episode during adolescence (Abela & Hankin, 2011; Spasojevic & Alloy, 2001). Additionally, pronounced sex differences in rumination develop during adolescence, such that girls tend to ruminate more than boys (e.g., Nolen-Hoeksema, Larson, & Grayson, 1999; Jose & Brown, 2008). This sex difference in rumination may be due in part to female adolescents’ increased exposure to stressful life events and affinities to engage in passive coping strategies (Hamilton, Stange, Abramson, & Alloy, in press; Jose & Brown, 2008). Girls’ tendencies to ruminate may be one factor that contributes to the marked sex difference in depression that emerges during adolescence (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 1999).

Although rumination has received considerable attention as a cognitive vulnerability for depression, few studies have focused on how depressive symptoms may predict changes in these negative cognitions. Given that Response Styles Theory (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991) suggests that the ways in which individuals respond to negative mood states may impact psychosocial functioning, it is also important to consider how initial depressive affect can contribute to the development and maintenance of a ruminative response style, which may perpetuate future depression. Research has shown that rumination and depression may exist in a maladaptive cycle, in which rumination is both a risk factor and a result of depressive affect (Calvete, Orue, & Hankin, 2013). Nolen-Hoeksema and colleagues (1999) tested several models that address this cycle, finding that rumination predicts increased depressive symptoms (feedback effects model) and also depressive symptoms predict increases in rumination over time (depression effects model). The latter model indicates that increased rumination may be a consequence, as well as a vulnerability factor, for individuals experiencing high levels of depressive symptoms. However, support for both models is indicative of the cyclical nature of depression

Just as rumination may be a precursor and a result of depressed mood, other affective vulnerability factors for depression also may be related to depression and contribute to its iterative pattern. Specifically, one important and understudied risk factor in adolescence is poor emotional clarity, a component of emotional intelligence. Emotional clarity encompasses the understanding and awareness of one’s own emotional experiences and the ability to label them appropriately (Gohm & Clore, 2002). Like other facets of emotional intelligence, emotional clarity is adaptive for everyday coping, problem solving, and general mental health (Salovey & Mayer, 1990). High emotional clarity is associated with conscientiousness, active coping strategies, positive reinterpretation of stressful events, and increases in well-being among adults (Gohm & Clore, 2002). Emotional clarity is hypothesized to be adaptive because the ability to discriminate among and comprehend one’s own emotions allows for resources to be allocated towards goal-directed behaviors and cognitions rather than towards recognizing one’s own emotional experiences (Flynn & Rudolph, 2010; Gohm & Clore, 2000).

Past research has consistently reported an inverse relationship between emotional clarity and depression, and much research documents emotional clarity deficits as a precursor to depressed mood. For example, deficits in emotional clarity were found to predict increases in depressive symptoms over time in children (Flynn & Rudolph, 2010), and high levels of emotional clarity were found to protect older adults who were experiencing chronic pain from increases in depressive symptoms (Kennedy et al., 2010). However, relatively few studies have examined the role of emotional clarity in adolescent mood and cognition. In adolescents, high emotional clarity has been found to protect against the influence of negative cognitive styles on increases in depressive symptoms, including after exposure to stressful life events (Stange, Alloy, Flynn, & Abramson, 2013a; Stange et al., 2013b). Low emotional clarity also has been found to be associated with other negative outcomes in adolescents, such as anxiety, poor life satisfaction, and high levels of perceived stress (Extremera & Fernandez-Berrocal, 2005; 2006).

Although there is support for the link between low levels of emotional clarity and increases in depressive symptoms, few studies have examined factors that predict changes in emotional clarity over time for adolescents, such as depressed mood and responses to depressed mood (i.e., rumination). Just as emotional clarity deficits may be associated with increases in depressive symptoms, the cyclical nature of depression may contribute to poor emotional intelligence over time. Given that adolescence is a time of abundant and rapid change, considering changes in emotional clarity during this period of development may be beneficial for revealing the overlapping relationships between emotions, cognitive processes, and mood states. Throughout puberty, adolescents generally become more adept at identifying complex social emotions (Burnett, Thompson, Bird, & Blakemore, 2011), indicating that this ability generally improves over time. Adolescence also is considered a time when emotional lability is likely to occur, including increases in mood disruptions, volatile moods, and mood swings (Arnett, 1999). Thus, adolescents who experience increases in emotional clarity may benefit over time and become resilient to fluctuating mood states, including depressed mood. Specifically, emotional clarity is associated with both a belief that negative moods can be easily repaired and the ability to recover quickly from negative affective states (Gohm & Clore, 2000; Salovey, Mayer, Goldman, Turvey, & Palfai, 1995). However, depressed mood may not only be associated with lower emotional clarity, but also may impair the prospective development of emotional clarity. Depression has been associated with various information processing biases, including dysfunctional attention, memory, and interpretation of events (for review, see Everaert, Koster, & Derakshan, 2012). Depressed individuals are more likely to have difficulty inhibiting negative information, report overgeneral, negative memories over specific, positive memories, and construe emotionally ambiguous information as negative (Gotlib & Joorman, 2010). Thus, depression also may impair the processing of emotional information and further compromise individuals’ abilities to develop emotional understanding.

To elucidate the connection between depression and emotional intelligence, it is important to consider potential pathways that connect high levels of depressive symptoms to low emotional clarity, such as ruminative response styles to depressed mood. A few studies have begun to examine the inverse relationship between emotional clarity and rumination. Foremost, individuals with high emotional clarity experience a swift decline in ruminative thought following exposure to a negative event (Salovey et al., 1995). In depressed individuals, rumination as a cognitive emotion regulation strategy has been found to increase emotional suppression, acting in an opposite manner as emotional acceptance and understanding (Liverant, Kamholz, Sloan, & Brown, 2011). Given that rumination can increase emotional suppression, this process may, in turn, lead individuals to have increased difficulties recognizing, labeling, and distinguishing between emotions. Further, the negative thoughts that comprise rumination may deplete cognitive abilities that would otherwise aid in executive functioning, such as concentration and problem-solving abilities (Connolly et al. 2014; Levens, Muhtadie, & Gotlib, 2009). Therefore, it is possible that rumination may employ cognitive resources that subsequently detract from individuals’ abilities to process complex information, such as emotions.

The Present Study

The present study sought to understand and predict change in emotional clarity during adolescence. Whereas emotional clarity generally has been studied as a risk factor for depression (e.g., Stange et al., 2013a), the current investigation aimed instead to understand the development of emotional clarity in adolescence as a consequence of depressive symptoms. Additionally, to evaluate the role of cognitive processes in this relationship, we examined whether rumination as a maladaptive response style may serve as a mediating factor between depressive symptoms and decreases in emotional clarity. Further, given research documenting that girls are more vulnerable to depressed mood and ruminative strategies (Hankin et al., 1998; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 1999), we examined whether adolescent girls were particularly vulnerable to experiencing decreases in emotional clarity as a result of a greater likelihood of ruminating following depressed mood. Based on past research documenting the inverse relationship between emotional clarity and depression (e.g., Flynn & Rudolph, 2010; Stange et al., 2013a,b), we hypothesized that depressive symptoms would predict decreases in emotional clarity over time. Furthermore, we hypothesized that sex would moderate the impact of depressive symptoms on rumination, such that depression would lead to increases in ruminative response styles for adolescent girls, which would, in turn, predict decreases in emotional clarity over time.

Methods

Participants

Participants were individuals recruited to participate in Project XXX, which was approved by the XX Institutional Review Board. Project XXX is a prospective, longitudinal examination of the development of depressive and anxiety disorders in adolescence. Participants were recruited from public and private middle schools in the XX area with the permission of the XX School District through mailings and follow-up phone calls (approximately 68% of the sample), as well as through advertisements in local newspapers (approximately 32% of the sample).

Inclusion criteria in the study included being 12 or 13 years of age, self-identifying as Caucasian/White, African American/Black, or Biracial, and having a mother or primary female caregiver who was willing to participate. Exclusion criteria for the study included having no mother or primary female caregiver who agreed to participate, not being competent in reading or speaking English, and having a mother or adolescent with mental retardation, a severe learning disability or other cognitive impairment, a severe developmental disorder, a psychotic disorder, or any other psychiatric or medical problem that would not allow mothers or adolescents to complete the study. These criteria were developed because some of the larger aims of this longitudinal study involve examining how potential racial differences, maternal/caregiver factors, and mothers’/caregivers’ reports about their children may be involved in the onset and course of psychopathology during adolescence. (For a comprehensive description of Project XXX, see XX et al., 2012.)

The participants for the current study include Project XXX adolescents who completed Time 1 assessments and at least two follow-up assessments to date (follow-ups are ongoing). The participants in the current study are 223 racially diverse adolescents (51.57% female; 48.43% Caucasian, 46.64% African American, 4.93% Biracial; Mean age = 12.39, SD = 0.62). The average length of time for participants between Times 1 and 2 was 16.20 months (SD = 4.81) and between Times 2 and 3 was 11.07 months (SD = 4.28). Further, the average age of participants at Time 2 was 13.76 years (SD = 0.76) and the average age at Time 3 was 14.72 years (SD = 0.78). Participants in Project XXX who completed Time 1 assessments but only completed one follow-up assessment (N = 97) or no follow-up assessments (N = 117) as of the time of these analyses were excluded from the present study. Adolescents from Project XXX included in the current study did not significantly differ from those who did not yet complete two follow-up sessions on demographic information, or levels of depressive symptoms, rumination, or emotional clarity at Time 1.

Procedure

All assessments took place at XX in the Project XXX laboratory. Time 1 consisted of two sessions that took place approximately 30 days apart for 2-3 hours each. During these sessions, the adolescents completed behavioral tasks and both the adolescents and their mothers completed questionnaires and diagnostic interviews. At the Time 1 assessment, adolescent participants completed measures of depressive symptoms, emotional clarity, and rumination. At all follow-up sessions, adolescents completed additional measures of rumination and emotional clarity. The present study used data only from the adolescents, including questionnaires at Time 1 and two follow-up sessions (Times 2 and 3). Adolescents and their mothers were compensated for their participation at each study assessment.

Measures

Depressive Symptoms

The Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 1985) is a 27-item, self-report measure of current (i.e., over the past two weeks) depressive symptomatology for children and adolescents. It is the most commonly used self-report measure to assess depressive symptoms in youth and is designed for individuals ages 7 to 17 years old. The items include cognitive, affective, and behavioral depressive symptoms, which are scored from 0-2 with higher scores indicating higher levels of depressive symptoms. The total score for all items was used; scores ranged from 0 to 32. The current study used the CDI from Time 1. Internal consistency for the CDI in the current sample was α = .85.

Rumination

The Children’s Response Styles Questionnaire (CRSQ; Abela, Vanderbilt, & Rochon, 2004) is a 25-item, self-report measure that captures youth’s cognitive responses to depressed or sad mood. The CRSQ contains three subscales to measure response styles: rumination, distraction, and problem-solving. Participants are asked to rate the frequency of their feelings and thoughts when they are sad on a scale of 1 to 4 (never, sometimes, often, almost always). Higher scores within each subscale indicate a greater tendency to engage in each response style when experiencing a depressed mood. The present study only used scores from the rumination subscale at Times 1 and 2. Past research has indicated that the CRSQ has good internal validity (Abela et al., 2004). In the current study, internal consistency of the rumination subscale of the CRSQ was good at Time 1 (α = .87) and Time 2 (α = .90).

Emotional Clarity

The Emotional Clarity Questionnaire (ECQ; Flynn & Rudolph, 2010) is a 7-item, self-report measure that has been adapted for use with youth (Salovey et al., 1995). This scale is designed to measure perceived emotional clarity by asking youth to rate their responses on a 5-point Likert scale from not at all to very much. Items involve how youth experience their feelings, such as “I usually know how I am feeling,” “My feelings usually make sense to me,” and “I am often confused about my feelings” (reverse-scored). ECQ scores are calculated by summing item scores, and total scores can range from 5-35. Higher scores on this measure indicate greater levels of emotional clarity. Flynn and Rudolph (2010) demonstrated that the ECQ has good internal consistency and convergent validity through significant correlations with congruent behavioral measures that assess emotional processing abilities, such as identifying affect through facial expressions. The ECQ also demonstrated adequate internal consistency for the current sample (Time 1, α = .81; Time 3, α = .88).

Data Analysis Approach

To examine the relationship between depressive symptoms and decreases in emotional clarity, we conducted hierarchical linear regressions predicting Time 3 emotional clarity, while statistically controlling for Time 1 emotional clarity. In the first step of the regression, Time 1 emotional clarity was entered, and in the second step, Time 1 depressive symptoms were entered. Thus, regression was used to analyze the unique effects of depressive symptoms at baseline on changes in emotional clarity from baseline to the final follow-up assessment.

Further, to examine rumination as a potential mediator of the association between depressive symptoms and changes over time in emotional clarity, and to examine whether this was different for girls versus boys, we conducted moderated mediation analyses using a bootstrapping approach. Bootstrapping is a nonparametric resampling procedure that is used to approximate the sampling distribution of a statistic from the available data. To utilize this technique, we employed the SPSS macro PROCESS to test the significance of the indirect effects of Time 1 depressive symptoms on Time 3 emotional clarity via Time 2 rumination, with a 95% confidence interval and N = 10,000 bootstrap resamples (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). Sampling distributions of indirect effects are created by taking a sample, with replacement, of size N from the full data set and calculating the indirect effects in the resamples (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). Further, sex was investigated as a moderator of the first path of the mediation analysis, to examine whether girls were more likely than boys to experiences increases in rumination following depressive symptoms, and whether the rumination was a significant mediator between depressive symptoms and emotional clarity differentially for girls versus boys. Race was controlled for in the regression and moderated mediation analyses.

Results

Descriptive Analyses and Sex Differences

Descriptive statistics for Times 1, 2, and 3 by sex are displayed in Table 1. Analyses were conducted to determine whether there were any significant sex differences on study variables. Sex differences in Time 1 depressive symptoms and rumination at both Times 1 and 2 were present, in which girls reported higher levels of both constructs than boys. Although there were no differences in emotional clarity between boys and girls at Time 1, sex differences in emotional clarity emerged at Time 3, with girls reporting significantly lower levels of emotional clarity than boys (Table 1). There were no significant racial differences in any of the study variables under investigation. Table 2 presents correlations among study variables. As expected, depressive symptoms at Time 1 were positively correlated with rumination at Times 1 and 2. Additionally, depressive symptoms at Time 1were negatively associated with emotional clarity at Times 1 and 3. Finally, rumination at Times 1 and 2 was negatively correlated with emotional clarity at Times 1 and 3.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Sex Differences in Study Variables

| Measure | Overall Sample N = 223 |

Boys N = 108 |

Girls N = 115 |

Sex Difference |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | t | |

| Time 1 | |||||||

| CDI | 6.82 | 5.83 | 5.85 | 5.06 | 7.73 | 6.37 | −2.45* |

| CRSQ-R | 24.85 | 7.67 | 23.48 | 6.61 | 26.14 | 8.37 | −2.65** |

| ECQ | 24.57 | 4.13 | 24.96 | 4.07 | 24.20 | 4.17 | 1.39 |

| Time 2 | |||||||

| CRSQ-R | 23.24 | 9.01 | 20.18 | 7.05 | 26.11 | 9.71 | −5.25*** |

| Time 3 | |||||||

| ECQ | 27.63 | 5.45 | 29.26 | 5.21 | 26.10 | 5.25 | 4.51*** |

Note.

p < .01,

p < .001;

CDI = Children’s Depression Inventory; ECQ = Emotional Clarity Questionnaire; CRSQ-R = Children’s Response Styles Questionnaire-Ruminative Response Subscale.

Table 2.

Bivariate Correlations of Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Time 1 CDI | — | |||

| 2 | Time 1 CRSQ-R | .44*** | — | ||

| 3 | Time 1 ECQ | −.43*** | −.20** | — | |

| 4 | Time 2 CRSQ-R | .29*** | .49*** | −.07 | — |

| 5 | Time 3 ECQ | −.32*** | −.17* | .44*** | −.29*** |

Note.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

CDI = Children’s Depression Inventory; ECQ = Emotional Clarity Questionnaire; CRSQ-R = Children’s Response Styles Questionnaire-Ruminative Response Subscale.

Prospective Analyses

To examine potential changes in emotional clarity over the course of the study for our group of adolescents, we conducted a paired-samples t-test to compare levels of this construct at Time 1 and Time 3. Results indicated that emotional clarity significantly increased from Time 1 (M = 24.57, SD = 4.13) to Time 3 (M = 27.63, SD = 5.45) for the overall sample (t (222) = −8.83, p < .001). Further, in accordance with hypotheses, hierarchical regression analyses indicated that depressive symptoms at Time 1 significantly predicted decreases in emotional clarity from Time 1 to Time 3, (β = −.16, p = .02).

Moderated Mediation Analyses

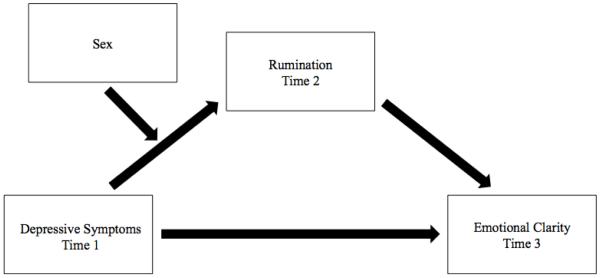

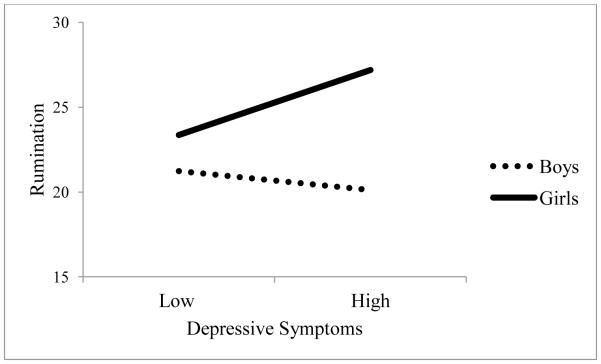

We examined whether rumination mediated the relationship between Time 1 depressive symptoms and Time 3 emotional clarity, and whether sex moderated the first path of the mediation analysis, controlling for Time 1 emotional clarity and rumination (see Figure 1). Consistent with hypotheses, there was a significant interaction between sex and Time 1 depressive symptoms predicting Time 2 rumination (Figure 2), such that depressive symptoms predicted higher levels of rumination for girls (t = 2.52, p = .01) but not for boys (t = −0.59, p = .56). Furthermore, there was a significant indirect effect of Time 1 depressive symptoms on decreases in emotional clarity at Time 3 through Time 2 rumination, controlling for Time 1 emotional clarity and rumination, only for adolescent girls (Table 3). Thus, rumination mediated the relationship between depressive symptoms and decreases in emotional clarity among adolescent girls, but not adolescent boys.

Figure 1.

Prospective moderated mediation model. Race, emotional clarity, and rumination at Time 1 were included as covariates in analyses.

Figure 2.

Sex moderates the relationship between depressive symptoms at Time 1 and rumination at Time 2. Significant CDI x sex interaction (model R2 = .33, ΔR2 = .02, F = 4.94, B = 0.42, SE = 0.18, p = .02). Depressive symptoms measured by Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI); Rumination measured by Children’s Response Styles Questionnaire-Ruminative Response Subscale (CRSQ-R); Emotional clarity and rumination at Time 1 included as a covariates in analyses.

Table 3.

Moderated mediation analyses: Sex moderates the relationship between depressive symptoms and emotional clarity via rumination.

| Sex Moderation of Depressive Symptoms at Time 1 as a Predictor of Rumination at Time 2 (a path) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Predictor | B | SE | t | |

|

| ||||

| Time 1 CDI | −0.09 | 0.15 | −0.57 | |

| Time 1 ECQ | 0.17 | 0.13 | 1.26 | |

| Time 1 CRSQ- R | 0.47 | 0.07 | 6.40*** | |

| Sex | 1.81 | 1.57 | 1.16 | |

| Race | −0.46 | 0.87 | −0.54 | |

| Time 1 CDI x Sex | 0.41 | 0.18 | 2.22* | |

|

| ||||

| Model R-Square = 0.33, F = 17.65, p < .001. | ||||

| Rumination at Time 2 Predicting Emotional Clarity at Time 3 (b path) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Predictor | B | SE | t | |

|

| ||||

| Time 1 CDI | −0.10 | 0.07 | −1.50 | |

| Time 1 ECQ | 0.53 | 0.08 | 6.22*** | |

| Time 1 CRSQ- R | 0.07 | 0.05 | 1.33 | |

| Time 2 CRSQ-R | −0.17 | 0.04 | −4.19*** | |

| Race | −0.17 | 0.53 | −0.32 | |

|

| ||||

| Model R-Square = 0.28, F = 16.51, p< .001. | ||||

| Conditional Indirect Effect of Depressive Symptoms at Time 1 on Emotional Clarity at Time 3 via Rumination at Time 2 by Sex (c’ path) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Indirect Effect | SE | CI (lower) | CI (upper) | |

|

| ||||

| Boys | 0.02 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.07 |

| Girls | −0.05 | 0.03 | −0.13 | −0.004 |

Note.

p < .05,

p < .001;

B = Coefficient, SE = Standard Error, t = student’s t-test; CDI = Children’s Depression Inventory; ECQ = Emotional Clarity Questionnaire; CRSQ-R = Children’s Response Styles Questionnaire-Ruminative Response Subscale; Sex, 0 = Male, 1 = Female; Confidence intervals that do not contain 0 are statistically significant, implying mediation.

Discussion

Emotional clarity typically has been conceptualized as a trait-like characteristic, and deficits in this ability have been found to place adolescents at risk for depression (Flynn & Rudolph, 2010; Stange et al., 2013a). However, the results of the current study indicate that emotional clarity has the capacity to change across adolescence, and depressive symptoms predict decreases in the ability to understand and label one’s own emotions. Over approximately a two-year interval, initial depressive symptoms in early adolescence predicted decreases in emotional clarity later in adolescence. Further, changes in rumination, as a maladaptive response style to depressed mood, significantly mediated this relationship among girls, but not for boys. Thus, our results indicate that the process through which depressive symptoms predict decreases in emotional clarity via rumination may only be true for adolescent girls and not for their male peers. Thus, these findings suggest that depressive symptoms may increase female adolescents’ tendencies to engage in repetitive, negative self-focused thinking, which lessens the ability to understand and label one’s emotions.

Inasmuch as the current results suggest that emotional clarity is malleable during adolescence, we analyzed how depressive symptoms might contribute to these fluctuations. Experiencing symptoms of depression is extremely common for young people, and understanding how depressive symptoms may lead to deficits in emotional clarity is important for a broader conceptualization of how adolescents comprehend their own emotions in the face of dysphoria. Using a prospective design, we found that depressive symptoms during early adolescence predicted deficits in emotional clarity about two years later, after taking into account initial levels of emotional clarity. This finding suggests that early experiences of depression can have lasting consequences that persist throughout adolescent development and involve perception of emotional experiences.

Most notably in the present study, increases in rumination were the crucial link that connected depressive symptoms to decreases in emotional clarity over time for girls. The connection between depressive symptoms and rumination for female adolescents is not surprising. Rumination is considered a maladaptive response style to depression that is consistently more common in females beginning in adolescence, and depressive symptoms can lead to increases in ruminative thinking (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 1999). However, this study bridges the gap between rumination, a cognitive vulnerability, and emotional clarity, a facet of emotional intelligence, which has received less attention.

Several factors may drive this association between increased rumination and decreased emotional clarity for girls during adolescence. Rumination involves repetitive, passive focus on the causes and consequences of distressing symptoms (i.e., depression), without taking any action to relieve these symptoms (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008). As a cognitive strategy, rumination may deplete executive functions such as attention, block effective problem-solving strategies, increase pessimism, and prolong distress (Lyubomirsky & Nolen-Hoeksema, 1995; Lyubomirsky, Kasri, & Zehm, 2003). Further, adolescents who ruminate tend to passively focus their thought processes on negative affect rather than on the broad range of positive and negative emotional experiences that may be accessible to others, and they also may engage in emotional suppression (Liverant et al., 2011; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008). By repetitively focusing on only negative emotions and their associated distress, adolescents who ruminate may forgo the opportunity to develop an adequate understanding of a wide range of emotional experiences.

Thus, girls, who are especially vulnerable to rumination (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 1999), might also experience emotional clarity deficits due to their persistent, repetitive focus on negative affect. Rumination may decrease the ability to clearly identify emotions by maintaining negative mood states and contributing to a misperception about the emotions an individual is experiencing. At the root of these vulnerabilities, depressive symptoms may be responsible for perpetuating rumination and initiating the connection between rumination and lower emotional clarity in adolescent girls. Furthermore, initial depressive symptoms may contribute to a cyclic effect of increasing rumination and decreasing emotional clarity, which could further increase vulnerability to depression over time. However, this relationship may not be true for adolescent boys, who are less prone to rumination than their female peers. Thus, future research is needed to examine what factors might contribute to decreases emotional clarity among adolescent boys.

In addition to clarifying the relationship between depressive symptoms and emotional clarity, the present study also contributes to a broader understanding that emotional clarity during adolescence is not a stable trait. Generally, we found that emotional clarity tended to increase over time in our sample of adolescents. Overall, from ages 12 to 14, adolescents became significantly better at identifying and labeling their own emotional experiences. This finding is in line with research on emotional development (i.e. Burnett et al., 2011), which indicates that as adolescents develop, their awareness and understanding of emotions increases. Interestingly, we found that during middle adolescence, boys experienced higher levels of emotional clarity than their female peers. This finding is inconsistent with research indicating that adolescent girls typically rate their emotional intelligence higher than boys (Ciarrochi, Chan, & Bajgar, 2001). However, adolescent girls may be more vulnerable to having lower emotional clarity than boys, just as girls are more susceptible to developing depression, experiencing stressful life events, engaging in passive coping strategies, and utilizing rumination as a response style to depressed mood (Hankin et al., 1998; Jose & Brown, 2008; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 1999). If adolescent girls are experiencing more stress and confusion surrounding emotions, it may be more difficult to understand and label how they are feeling.

The present study has several key strengths that enhance the research findings. Foremost, the current investigation utilizes a prospective design that chronicles adolescents throughout development at three time points over approximately a two-year period. Assessing individuals throughout early and middle adolescence allows for a more comprehensive analysis of the study variables over time, in order to determine how development impacts each of the measures in this study. Additionally, the study design allows for a fully prospective test of mediation that analyzes how the main study variables are related temporally. Further, this study involved a large, diverse sample of adolescents, which contributes to the generalizability of the findings in the overall population.

Along with these strengths, the current study could be improved in several ways. First, we chose to examine depression at the symptom level as a predictor in our analyses. Future research could examine depression at the diagnostic level to understand how depressive episodes might contribute to the connection between rumination and emotional clarity. Additionally, this study employed self-report measures to capture adolescent experiences of depressive symptoms, rumination, and emotional clarity. Thus, these measures are all based on adolescents’ own perceptions of their thoughts and feelings and could be subject to shared method variance. Further studies could involve semi-structured clinical interviews to capture depressive symptoms/diagnoses, along with more comprehensive assessments of rumination and emotional clarity. Additionally, the current study used a measure of rumination (CRSQ) that does not parse apart the two sub-dimensions of rumination, brooding and reflection, that have been identified with other scales, such as the Ruminative Response Scale of the Response Styles Questionnaire (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991). Thus, future research could utilize a different measure to examine how these sub-dimensions may differentially impact the relationship between depression and emotional clarity development. Subsequent studies also could analyze how depression leads to increased reliance on other response styles that are maladaptive (e.g., emotion suppression) or inflexible (e.g., Aldao, Sheppes, & Gross, in press), or decreased reliance on adaptive response styles (e.g., distraction, problem-solving, cognitive reappraisal) and further, how depression impacts changes in other facets of emotional experience (e.g., attention, expression, intensity; Gohm & Clore, 2002). Finally, future investigation should consider other factors in development that may impact the development of emotional clarity during adolescence, such as pubertal timing.

Ultimately, the current study aimed to identify factors that confer risk for decreases in emotional clarity during adolescence, particularly among adolescent girls. Based on our model, levels of depressive symptoms in early adolescence predicted decreases in emotional clarity two years later, via high levels of ruminative response styles for girls. The present results suggest that although emotional clarity may generally increase during adolescence, individuals who experience depressive symptoms during this time may be susceptible to experiencing decreases in the ability to label and identify their emotions. For girls, rumination may explain this link, by creating maladaptive cognitions in which girls focus exclusively on negative affect and subsequently fail to gain clarity about their emotional experiences. These findings have important implications about the nature of emotional clarity development in adolescence. Specifically, experiences of depression can lead to deficits in emotional understanding over time through the maladaptive cognitive strategy of rumination for girls. Thus, potential prevention programs for depression during adolescence might aim to enhance emotional clarity and consider how cognitive vulnerabilities such as rumination may contribute to deficits in understanding emotional experiences. Inasmuch as depressive symptoms are widespread and dramatically increase throughout adolescence, pinpointing how depression can lead to adverse cognitive and emotional processes will contribute to an overall understanding of adolescent mood and mental health.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Institute of Mental Health grants MH79369 and MH101168 to Lauren B. Alloy. Jessica L. Hamilton was supported by National Research Service Award 1F31MH106184 from NIMH. Jonathan P. Stange was supported by National Research Service Award 1F31MH099761 from NIMH.

Footnotes

Journal of Adolescence, in press.

References

- Abela JRZ, Hankin BL. Cognitive vulnerability to depression in children and adolescents: A developmental psychopathology perspective. In: Abela JRZ, Hankin BL, editors. Handbook of Depression in Children and Adolescents. Guilford; New York: 2008. pp. 35–78. [Google Scholar]

- Abela JRZ, Hankin BL. Rumination as a vulnerability factor to depression during the transition from early to middle adolescence: A multiwave longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2011;120(2):259–271. doi: 10.1037/a0022796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abela JRZ, Vanderbilt E, Rochon A. A test of the integration of the response styles and social support theories of depression in third and seventh grade children. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2004;23(5):653–674. [Google Scholar]

- Aldao A, Sheppes G, Gross JJ. Emotion regulation flexibility. Cognitive Therapy and Research. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Black SK, Young ME, Goldstein KE, Shapero BG, Stange JP, et al. Cognitive vulnerabilities and depression versus other psychopathology symptoms and diagnoses in early adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2012;41(5):539–560. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.703123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Adolescent storm and stress, reconsidered. The American Psychologist. 1999;54(5):317–326. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.5.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avenevoli S, Knight E, Kessler RC, Merikangas KR. Epidemiology of depression in children and adolescents. In: Abela JRZ, Hankin BL, editors. Handbook of depression in children and adolescents. Guilford; New York: 2008. pp. 6–32. [Google Scholar]

- Burnett S, Thompson S, Bird G, Blakemore SJ. Pubertal development of the understanding of social emotions: Implications for education. Learning and Individual Differences. 2011;21(6):681–689. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvete E, Orue I, Hankin BL. Transactional relationships among cognitive vulnerabilities, stressors, and depressive symptoms in adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2013;41(3):399–410. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9691-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciarrochi J, Chan AYC, Bajgar J. Measuring emotional intelligence in adolescence. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;31:1105–1119. [Google Scholar]

- Connolly SL, Wagner CA, Shapero BG, Pendergast LL, Abramson LY, Alloy LB. Rumination prospectively predicts executive functioning impairments in adolescents. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2014;45:46–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2013.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everaert J, Koster EHW, Derakshan N. The combined cognitive bias hypothesis in depression. Clinical Psychology Review. 2012;32:413–424. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Extremera N, Fernandez-Berrocal P. Perceived emotional intelligence and life satisfaction: Predictive and incremental validity using the Trait Meta-Mood Scale. Personality and Individual Differences. 2005;39(5):937–948. [Google Scholar]

- Extremera N, Fernandez-Berrocal P. Emotional intelligence as predictor of mental, social, and physical health in university students. The Spanish Journal of Psychology. 2006;9(1):45–51. doi: 10.1017/s1138741600005965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn M, Rudolph KD. The contribution of deficits in emotional clarity to stress responses and depression. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2010;31(4):291–297. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge XJ, Lorenz FO, Conger RD, Elder GH, Simons RL. Trajectories of stressful life events and depressive symptoms during adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 1994;30(4):467–483. [Google Scholar]

- Gelenberg AJ. The prevalence and impact of depression. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2010;71(3):e06–e06. doi: 10.4088/JCP.8001tx17c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gohm CL, Clore GL. Individual differences in emotional experience: Mapping available scales to processes. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2000;26(6):679–697. [Google Scholar]

- Gohm CL, Clore GL. Four latent traits of emotional experience and their involvement in well-being, coping, and attributional style. Cognition and Emotion. 2002;16(4):495–518. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Tejera G, Canino G, Ramirez R, Chavez L, Shrout P, Bird H, et al. Examining minor and major depression in adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;46(8):888–899. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.00370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotlib IH, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR. Symptoms versus a diagnosis of depression: Differences in psychosocial functioning. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63(1):90–100. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton JL, Stange JP, Abramson LY, Alloy LB. Stress and the development of cognitive vulnerabilities to depression explain sex differences in depressive symptoms during adolescence. Clinical Psychological Science. doi: 10.1177/2167702614545479. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abramson LY, Moffitt TE, Silva PA, McGee R, Angell KE. Development of depression from preadolescence to young adulthood: Emerging gender differences in a 10-year longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:128–40. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.1.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Mermelstein R, Roesch L. Sex differences in adolescent depression: stress exposure and reactivity models. Child Development. 2007;78:279–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.00997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jose PE, Brown I. When does the gender difference in rumination begin? Gender and age differences in the use of rumination by adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2008;37:180–192. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy LA, Cohen TR, Panter AT, Devellis BM, Yamanis TJ, Jordan JM, Devellis RF. Buffering against the emotional impact of pain: Mood clarity reduces depressive symptoms in older adults. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2010;29(9):975–987. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. The Children’s Depression, Inventory (CDI) Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1985;21(4):995–998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levens SM, Muhtadie L, Gotlib IH. Rumination and impaired resource allocation in depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118:757–766. doi: 10.1037/a0017206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Clarke GN, Seeley JR, Rohde P. Major depression in community adolescents: Age at onset, episode duration, and time to recurrence. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1994;33:809–818. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199407000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liverant GI, Kamholz BW, Sloan DM, Brown TA. Rumination in clinical depression: A type of emotional suppression? Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2011;35(5):253–265. [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S, Kasri F, Zehm K. Dysphoric rumination impairs concentration on academic tasks. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2003;27(3):309–330. [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Effects of self-focused rumination on negative thinking and interpersonal problem solving. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69(1):176–190. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.1.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100(4):569–582. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Larson J, Grayson C. Explaining the gender difference in depressive symptoms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;77(5):1061–1072. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.77.5.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Wisco BE, Lyubomirsky S. Rethinking rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2008;3(5):400–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salovey P, Mayer JD. Emotional intelligence. Imagination, Cognition and Personality. 1990;9:185–211. [Google Scholar]

- Salovey P, Mayer JD, Goldman SL, Turvey C, Palfai TP. Emotional attention, clarity, and repair: Exploring emotional intelligence using the trait meta-mood scale. In: Pennebaker J, editor. Emotion, disclosure, and health. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Spasojevic J, Alloy LB. Rumination as a common mechanism relating depressive risk factors to depression. Emotion. 2001;1(1):25–37. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.1.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stange JP, Alloy LB, Flynn M, Abramson LY. Negative inferential style, emotional clarity, and life stress: integrating vulnerabilities to depression in adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2013a;42(4):508–518. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.743104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stange JP, Boccia AS, Shapero BG, Molz AR, Flynn M, Matt LM, et al. Emotional regulation characteristics and cognitive vulnerabilities interact to predict depressive symptoms in individuals at risk for bipolar disorder: A prospective behavioural high-risk study. Cognition and Emotion. 2013b;27(1):63–84. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2012.689758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Lang ND, Ferdinand RF, Verhulst FC. Predictors of future depression in early and late adolescence. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2007;97(1):137–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]