Abstract

The mesolimbic dopamine (DA) system is known to play a role in cue-mediated reward-seeking for natural rewards and drugs of abuse. Specifically, cholinergic and glutamatergic receptors in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) have been shown to regulate cue-induced drug-seeking. However, the potential role of these VTA receptors in regulating cue-induced reward seeking for natural rewards is unknown. Here, we examined whether blockade of VTA acetylcholine receptors (AChRs) and N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDARs) would alter cue-induced sucrose seeking in male Sprague-Dawley rats. Subjects underwent 10 days of sucrose self-administration training (fixed ratio 1 schedule) followed by 7 days of forced abstinence. On withdrawal day 7, rats received bilateral VTA infusion of vehicle, the muscarinic AChR antagonist scopolamine (2.4 or 24 μg/side), the nicotinic AChR antagonist mecamylamine (3 or 30 μg/side), or the NMDAR antagonist AP-5 (0.1 or 1 μg/side) immediately prior to examination of cue-induced sucrose-seeking. Scopolamine infusion led to robust attenuation, but did not completely block, sucrose-seeking behavior. In contrast, VTA administration of mecamylamine or AP-5 did not alter cue-induced sucrose-seeking. Together, the data suggest that VTA muscarinic AChRs, but not nicotinic AChRs nor NMDARs, facilitate the ability of food-associated cues to drive seeking behavior for a food reward.

Cues associated with natural rewards or drugs of abuse can induce craving, reward-seeking and relapse behavior in humans and in animal models [1–3]. While previous research has revealed a critical role of the mesolimbic dopamine system in cue-induced seeking for multiple drugs of abuse [4–6], there is less understanding of the neurobiological processes that underlie cue-induced food-seeking. Recent work has highlighted the role of dopamine signaling as D1 receptor antagonists, administered systemically or directly to the nucleus accumbens (NAc), attenuate cue-induced sucrose-seeking in rats [1]. D1 receptors are low affinity receptors that are preferentially activated by the high concentration, phasic DA release that results from burst firing of DA neurons [7]. Indeed, the presentation of either food rewards or food-associated cues leads to a time-locked increase in DA burst firing in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and a time-locked increase in phasic DA release in the NAc [8, 9]. Thus, VTA processes that regulate DA activity may also play an important role in cue-induced sucrose-seeking.

Both glutamatergic and cholinergic receptors mechanisms in the VTA regulate DA activity and release. Specifically, activation of NMDA receptors induces burst firing in DA neurons [10]. In addition, the VTA contains two classes of AChRs: the ionotropic, nicotinic AChRs (nAChRs) and the metabotropic, muscarinic AChRs (mAChRs). Multiple nAChR and mAChR subtypes, with specific presynaptic and postsynaptic cellular localization, can powerfully modulate phasic DA activity [11]. Our recent work also revealed that VTA acetylcholine receptors (AChRs) powerfully regulate cue-induced drug-seeking behavior in cocaine-withdrawn subjects [6]. However, the role of VTA AChR mechanisms in cue-induced food-seeking behavior is largely unknown. To date, examinations of VTA cholinergic receptor mechanisms for food reward have mainly focused on free feeding behavior and operant learning [12, 13]. In the current study, we sought to determine whether VTA nAChR and mAChR mechanisms mediate cue-induced sucrose-seeking. Given the role of NMDA receptors (NMDARs) in regulating DA responses to cues [14], we also examined the role of VTA NMDARs in cue-induced sucrose-seeking. Our findings suggest that VTA mAChRs, but not nAChRs nor NMDARs, facilitate cue-induced sucrose-seeking during early withdrawal. The understanding gained from this work, together with previous examinations of cue-induced drug-seeking, has important implications for understanding the processes that guide natural reward-seeking and those that guide specific types of drug-seeking behavior. This understanding is important given the emergence of new tobacco products, such as e-cigarettes, which combine sweet flavorants with nicotine delivery.

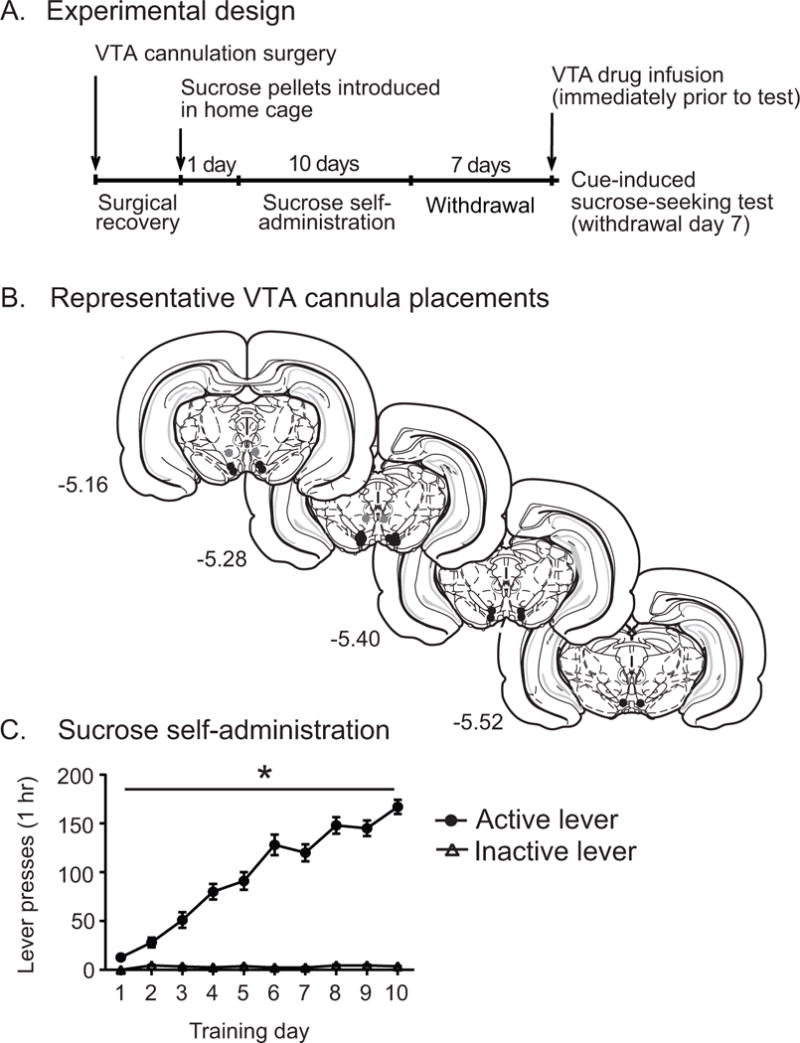

All experiments were performed in Sprague Dawley rats (250–275 g) acquired from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA) that were housed on a 12 hour light/dark cycle (lights on at 7 am). All experiments were conducted according to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Yale University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). After 5 to 7 day acclimation to the housing facility, rats were anesthetized with ketamine HCl (100 mg/kg, i.p.) and xylazine (10 mg/kg, i.p., both from Henry Schein Animal Health, Chicago, IL) and bilateral, 26 gauge cannula were stereotaxically implanted above the VTA (AP −5.3 mm, ML ±0.5 mm, DV −7.0 mm from dura, Fig. 1B). Following 5 to 7 days of surgical recovery, rats were restricted to 90% free feeding levels for 2 to 3 days. One day prior to training, 20 to 30 sucrose pellets (45 mg BioServ pellets, Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) were placed into the home cage to introduce the rats to sucrose.

Fig. 1.

A) Experimental timeline. B) Representative VTA cannula placements. C) Acquisition of sucrose-self administration behavior (FR 1) over 10 days (main effect of lever and training day, p < 0.0001; lever x day interaction, p < 0.0001).

Behavioral data was collected in 3 independently trained cohorts, where vehicle and drug groups were run in parallel on withdrawal day 7 (WD7). All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, Inc, San Diego, CA) and all data are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Analysis of sucrose self-administration training was performed using a two way, repeated measures ANOVA with lever (active versus inactive) and training day as factors. “To be” vehicle and “to be” drug groups for the WD7 experiment were assigned in a non-biased manner, with no between group differences in lever presses on training day 10. Analysis of WD7 data was independently performed for each drug using a two way ANOVA with repeated measures, where lever and treatment as factors. For within session analysis of lever presses for each drug experiment (over the 1 hr session), lever presses were quantified in 5 min bins and analyzed using a two way repeated measures ANOVA. Additional comparisons between specific drug doses (within each drug experiment) were performed using a post-hoc t-test with a Bonferroni correction.

Rats were trained for sucrose self-administration in operant chambers (25.4 cm × 30.48 cm × 30.48 cm, Med Associates, St. Albans, VT) on a fixed ratio 1 (FR1) schedule, where active lever depression led to the delivery of a 45 mg sucrose pellet (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) and the simultaneous presentation of a 6 sec audio-visual cue (tone + cue light presentation), followed by a 10 sec timeout where the lever was retracted. Inactive lever depression had no programmed consequence. Rats received 1 hr training sessions over 10 consecutive days and then underwent a 7 day period of forced abstinence, where they had no exposure to sucrose pellets, the operant chamber, or sucrose-associated contextual or discrete cues. Rats that did not acquire stable sucrose self-administration were excluded from the study. Rats included in the study readily acquired operant behavior for sucrose self-administration as revealed by a main effect of lever (F(1,63) = 327.6, p < 0.0001) and day (F(9,567)=57.79, p < 0.0001), and a significant lever x day interaction (F(9,567) = 62.74, p < 0.0001, Fig. 1C).

VTA infusion of vehicle (0.9% NaCl, saline) or drug (dissolved in saline vehicle) was performed immediately prior to the cue-induced sucrose-seeking test on WD7 using a 25 gauge, 10 μl syringe (Hamilton, Reno, NE) and a micro-infusion pump (Braintree Scientific, Braintree, MA). Saline, mecamylamine (Mec; 3 or 30 μg; Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MS, USA), scopolamine (Scop; 2.4 or 24 μg; Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MS, USA) or AP-5 (0.1 or 1 μg; Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MS, USA) was infused in a 0.5 μL volume over 1 min via a 33 gauge internal cannula (Plastics One, Roanoke, VA) that extended 1 mm beyond the guide cannula to target the VTA (D/V −8.0, Fig 1B). The internal cannula was left in place for 1 additional min after infusion to allow for complete drug absorption. Immediately after infusion, the extinction test was performed, where active lever depression resulted in delivery of the 6 sec audio-visual conditioned stimulus (tone + cue light) in the absence of sucrose pellet delivery. Inactive lever depression again had no programmed consequence. Drug doses were selected based on our previous investigations demonstrating the ability of these doses to alter phasic DA release and behavior [6, 15]. Importantly, we previously showed that VTA infusion of 24 μg Scop, 30 μg Mec, or 1 μg AP-5 did not alter locomotor activity [6, 16].

Scop infusion on WD7 robustly attenuated cue-induced sucrose-seeking behavior, as reveled by a main effect of treatment (F(2,20) = 13.03, p < 0.0005) and a lever x treatment interaction (F(2,20) = 5.67 p < 0.01, Fig 2A). A test of simple effects further revealed a significant Scop effect at the active lever (Sal vs. 2.4 μg Scop, p < 0.0001; Sal vs. 24 μg Scop, p < 0.0001), but no effect of Scop at the inactive lever (Sal vs. 2.4 μg, p > 0.05; Sal vs. 24 μg Scop, p > 0.05). Scop infusion, however, did not completely block cue-induced sucrose-seeking as subjects still discriminated between active and inactive levers (main effect of lever F(1,20) = 253.4, p < 0.0001; 2.4 μg Scop active vs. inactive, p < 0.001; 24 μg Scop active vs. inactive, p < 0.001, Fig 2A). Time dependent analysis of active lever presses in 5 min bins showed Scop attenuation of sucrose-seeking across the 60 min session, as revealed by a significant effect of treatment (F(2,20) = 12.11, p < 0.001) and time (F(11,220) = 36.75, p < 0.0001) and a significant treatment x time interaction (F(22,220) = 4.192, p < 0.0001, Fig. 2B). While the 2.4 μg Scop group showed less active lever pressing than the saline group at multiple time bins, the difference was only statistically significant at the 25 min bin (Sal vs. 2.4 μg Scop, p < 0.001). The 24 μg Scop infusion, in contrast, significantly attenuated active lever responding at multiple time bins (Sal vs. 24 μg Scop, p < 0.0001 at 5 min and 10 min, p < 0.01 at 15 min, p < 0.001 at 25 min, Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Examination of cue-induced sucrose-seeking during VTA infusion of cholinergic receptor or NMDA receptor antagonists. Scopolamine infusion attenuated cue-induced sucrose-seeking (N = 23) A) over a 1 hr period (main effect of treatment p < 0.0005, main effect of lever p < 0.0001, treatment x lever interaction p < 0.01) and B) at specific 5 min bins. In contrast, mecamylamine infusion did not alter sucrose-seeking (N = 22) C) over a 1 hr session or D) at any of the 5 min bins. AP-5 infusion also did not alter sucrose-seeking (N= 24) E) during a 1 hr session or F) at any 5 min bins.

In other subjects, VTA infusion of Mec or AP-5 on WD7 did not alter cue-induced sucrose-seeking behavior, as there was no significant effect of treatment for either Mec (F(2,19) = 0.4297, p > 0.05, Fig 2C) or AP-5 (F(2,21) = 0.2433, p > 0.05, Fig 2E). Analysis of active lever responses in 5 min bins revealed a significant effect of time on lever presses in the Mec (F(11,209) = 24.7, p < 0.01, Fig 2D) and AP-5 (F(11,231) = 29.6; p < 0.01, Fig 2F) groups, but no drug x treatment interaction for Mec (F(21,209) = 0.837, p > 0.05, Fid 2D) nor AP-5 subjects (F(23,231) = 0.597, p > 0.05, Fig. 2F).

At the completion of the experiments, rats were deeply anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (100 mg/kg, i.p. Henry Schein Animal Health, Chicago, IL), perfused with 0.9% saline and 3.2 % paraformaldehyde, and brains were removed and stored in 3.2% paraformaldehyde for 24 hours. Brains were then cyroprotected using a 30% sucrose and sliced into 50 μm coronal sections on a Cryostat (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL). Cannulae placements were examined in Nissel-stained sections under a light microscope and rats with misplaced cannula or extensive tissue damage (13 rats) were excluded from the statistical analysis.

Recent clinical and preclinical findings have highlighted the involvement of the mesolimbic DA system in cue-induced food-craving and food-seeking behavior [1, 17]. However, there is limited understating of VTA mechanisms in this cue-mediated behavior, despite the fact that DA cell bodies are contained within this brain region. Here, we found that blockade of mAChRs, with scopolamine, strongly attenuated cue-induced sucrose-seeking behavior but did not completely block the behavior, as subjects still discriminated between active and inactive levers. These findings suggest that VTA mAChRs facilitate, but are not necessary for, cue-induced sucrose-seeking. Importantly, these Scop findings are not likely due to nonspecific motor effects, as we have previously demonstrated that VTA infusion of 24 μg Scop does not alter general locomotor activity [16]. Previous work also demonstrated that VTA Scop infusion does not alter operant responding in a progressive ratio task in rats that have already undergone operant acquisition training [13]. Thus, we propose that our observed effects of VTA mAChR blockade are likely specific to cue-induced sucrose-seeking and would not be observed in a non-extinction session. These findings build on previous work to further delineate the role of mesolimbic DA mechanisms in cue-mediated food-seeking behavior. Recent investigations have demonstrated that systemic administration of a D1 antagonist is sufficient to attenuate cue-induced sucrose-seeking during sucrose withdrawal [1]. In a separate study, systemic D1 antagonist administration was also shown to inhibit cue-induced food reinstatement, where subjects underwent extinction prior to the D1 antagonist challenge and food seeking test [18]. More specifically, direct infusion of the D1 antagonist into the NAc was also sufficient to attenuate cue-induced sucrose-seeking [1]. Given that D1 receptors are preferentially activated by the large changes in DA concentration associated with phasic DA activity [7], the D1 data suggest that phasic DA release in the NAc likely plays a role in cue-induced sucrose-seeking.

Given the ability of VTA NMDARs to regulate burst firing of DA neurons and the subsequent phasic DA release in DA terminal regions, such as the NAc [10, 19], we hypothesized that VTA NMDARs would mediate cue-induced sucrose-seeking. However, we found no effect with NMDAR blockade. This lack of an NMDAR effect was not likely due to insufficient receptor blockade, as we and others have previously shown that VTA infusions of 1.0 μg AP-5, used in the current study, is sufficient to attenuate both phasic DA release [14, 15] and specific types of cue-mediated behavior [14]. One potential mechanistic explanation for our observed dissociation is that VTA NMDAR blockade may have no effect on phasic DA release in the NAc. While an examination of phasic DA release during sucrose-seeking is outside the scope of the current work, this is an important question that can be addressed in future studies. Indeed, we previously demonstrated that while VTA NMDAR blockade attenuates phasic DA release in drug naïve rats, this ability of NMDAR blockade to attenuate phasic DA and cue-induced cocaine-seeking is greatly diminished in cocaine-withdrawn subjects [6]. A potential underlying mechanism for the lack of an AP5 effect may be a potential shift towards VTA AMPA receptor, rather than NMDAR, regulation of phasic DA release that may occur after stimulus reward learning. Thus far, our current results and the previous findings in the literature suggest that VTA NMDAR mechanisms do not contribute to the expression of cue-mediated reward-seeking behavior during early withdrawal from sucrose or cocaine. Consistent with this interpretation, others have shown that VTA NMDARs are not required for the expression of conditioned approach behavior [20]. Indeed, Zellner and Ranaldi have proposed a model, where VTA NMDAR mechanisms mediate the acquisition, but not expression, of reward-related learning [21] – a model that it consistent with our current NMDAR results. However, the precise role of NMDARS is complex, as a role of VTA NMDARs in reward learning has been demonstrated for some specific operant tasks, including cue-mediated fear conditioning and the acquisition of operant responding for food [22, 23].

We also observed a cholinergic receptor dissociation, where mAChR blockade, but not nAChR blockade, attenuated cue-induced sucrose-seeking. This dissociation is similar to what was previously demonstrated in an operant task where mAChR, but not nAChR, blockade prevented the learning of operant responding for food [13]. Our findings, together with previous work, suggest that VTA mAChR, and not nAChR, mechanisms play a role in the learning of operant food-related tasks and in the expression of cue-mediated food seeking behavior. The evidence also suggests that nAChR VTA mechanisms, in contrast, contribute to cue-mediated behaviors associated with drug exposure. While VTA nAChR blockade did not alter cue-induced sucrose-seeking, we previously demonstrated that VTA nAChR blockade completely disrupted cue-induced cocaine-seeking during early withdrawal [6]. Others have also shown that VTA nAChRs mediate the ability of an ethanol associated cue to act as a conditioned reinforcer [4]. In addition to nAChR mechanisms in drug-cue related behavior, previous work revealed that 14 day nicotine exposure led to a β2 nAChR-dependent enhancement of conditioned reinforcement for a food associated cue [24]. While this previous study in β2 knockout animals did specifically not examine the role of β2 nAChRs in the VTA, this and other studies serve to highlight the involvement of nAChR mechanisms in cue-mediated behavior following exposure to drugs of abuse. Our current findings, together with previous findings, suggest that VTA mAChR mechanisms contribute to cue-mediated food seeking behavior while nAChR mechanisms contribute to drug-mediated behavior – either for food-seeking following drug exposure or for drug-seeking itself. This nAChR specificity for drug-seeking behavior also points to the utility of nAChRs as potential therapeutic targets for preventing cue-induced drug-seeking and relapse. These findings also have implications on our understanding of cue-induced craving and seeking for products that contain both sweet tastant rewards and drugs of abuse, such as oral tobacco products and e-cigarettes. In these tobacco products, drug and sweet food reward cues could potentially recruit both VTA nAChR and mAChR processes to powerfully promote drug-seeking and drug-taking behavior. Findings from the current work and future studies will thus provide valuable scientific understanding that can inform regulatory decisions regarding food flavorants in tobacco products.

We examined cue-induced sucrose-seeking during blockade of VTA AChRs or NMDARs

VTA scopolamine infusion attenuated cue-induced sucrose-seeking

VTA mecamylamine infusion did not alter cue-induced sucrose-seeking

VTA AP5 infusion did not alter cue-induced sucrose-seeking

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants DA036151 (EJN and NAA) and MH014276 (EJN) and by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (RJW). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the National Science Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Grimm JW, Harkness JH, Ratliff C, Barnes J, North K, Collins S. Effects of systemic or nucleus accumbens-directed dopamine D1 receptor antagonism on sucrose seeking in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;216:219–33. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2210-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rohsenow DJ, Niaura RS, Childress AR, Abrams DB, Monti PM. Cue reactivity in addictive behaviors: theoretical and treatment implications. Int J Addict. 1990;25:957–93. doi: 10.3109/10826089109071030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.See RE. Neural substrates of cocaine-cue associations that trigger relapse. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;526:140–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lof E, Olausson P, deBejczy A, Stomberg R, McIntosh JM, Taylor JR, et al. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the ventral tegmental area mediate the dopamine activating and reinforcing properties of ethanol cues. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;195:333–43. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0899-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shaham Y, Hope BT. The role of neuroadaptations in relapse to drug seeking. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1437–9. doi: 10.1038/nn1105-1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Solecki W, Wickham RJ, Behrens S, Wang J, Zwerling B, Mason GF, et al. Differential role of ventral tegmental area acetylcholine and N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors in cocaine-seeking. Neuropharmacology. 2013;75:9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goto Y, Grace AA. Dopamine-dependent interactions between limbic and prefrontal cortical plasticity in the nucleus accumbens: disruption by cocaine sensitization. Neuron. 2005;47:255–66. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Day JJ, Roitman MF, Wightman RM, Carelli RM. Associative learning mediates dynamic shifts in dopamine signaling in the nucleus accumbens. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1020–8. doi: 10.1038/nn1923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schultz W, Dayan P, Montague PR. A neural substrate of prediction and reward. Science. 1997;275:1593–9. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5306.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grace AA, Floresco SB, Goto Y, Lodge DJ. Regulation of firing of dopaminergic neurons and control of goal-directed behaviors. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:220–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maskos U. The cholinergic mesopontine tegmentum is a relatively neglected nicotinic master modulator of the dopaminergic system: relevance to drugs of abuse and pathology. British journal of pharmacology. 2008;153(Suppl 1):S438–45. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rada PV, Mark GP, Yeomans JJ, Hoebel BG. Acetylcholine release in ventral tegmental area by hypothalamic self-stimulation, eating, and drinking. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2000;65:375–9. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(99)00218-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharf R, McKelvey J, Ranaldi R. Blockade of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors in the ventral tegmental area prevents acquisition of food-rewarded operant responding in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;186:113–21. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0352-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sombers LA, Beyene M, Carelli RM, Wightman RM. Synaptic overflow of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens arises from neuronal activity in the ventral tegmental area. J Neurosci. 2009;29:1735–42. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5562-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wickham R, Solecki W, Rathbun L, McIntosh JM, Addy NA. Ventral tegmental area alpha6beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors modulate phasic dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens core. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2013;229:73–82. doi: 10.1007/s00213-013-3082-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Addy NA, Nunes EJ, Wickham RJ. Ventral tegmental area cholinergic mechanisms mediate behavioral responses in the forced swim test. Behav Brain Res. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2015.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jastreboff AM, Sinha R, Lacadie C, Small DM, Sherwin RS, Potenza MN. Neural correlates of stress- and food cue-induced food craving in obesity: association with insulin levels. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:394–402. doi: 10.2337/dc12-1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ball KT, Combs TA, Beyer DN. Opposing roles for dopamine D1- and D2-like receptors in discrete cue-induced reinstatement of food seeking. Behav Brain Res. 2011;222:390–3. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.03.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lester DB, Miller AD, Pate TD, Blaha CD. Midbrain acetylcholine and glutamate receptors modulate accumbal dopamine release. Neuroreport. 2008;19:991–5. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3283036e5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ranaldi R, Kest K, Zellner MR, Lubelski D, Muller J, Cruz Y, et al. The effects of VTA NMDA receptor antagonism on reward-related learning and associated c-fos expression in forebrain. Behav Brain Res. 2011;216:424–32. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zellner MR, Ranaldi R. How conditioned stimuli acquire the ability to activate VTA dopamine cells: a proposed neurobiological component of reward-related learning. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2010;34:769–80. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zellner MR, Kest K, Ranaldi R. NMDA receptor antagonism in the ventral tegmental area impairs acquisition of reward-related learning. Behav Brain Res. 2009;197:442–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zweifel LS, Parker JG, Lobb CJ, Rainwater A, Wall VZ, Fadok JP, et al. Disruption of NMDAR-dependent burst firing by dopamine neurons provides selective assessment of phasic dopamine-dependent behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:7281–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813415106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brunzell DH, Chang JR, Schneider B, Olausson P, Taylor JR, Picciotto MR. beta2-Subunit-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors are involved in nicotine-induced increases in conditioned reinforcement but not progressive ratio responding for food in C57BL/6 mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;184:328–38. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0099-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]