Abstract

Background

We examined baseline age and combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) as determinants of CD4+T-cell recovery during six months of tuberculosis (TB) therapy with/without cART. We determined whether this association was modified by patient sex and nutritional status.

Methods

This longitudinal analysis included 208 immune-competent, non-pregnant, ART-naive HIV-positive patients from Uganda with a first episode of pulmonary TB. CD4+T-cell count was measured using flow cytometry. Age was defined as ≤24, 25–29, 30–34, 35–39 vs. ≥ 40 years. Nutritional status was defined as normal (>18.5kg/m2) vs. underweight (≤18.5kg/m2) using body mass index (BMI). Multivariate random-effects linear mixed models were fitted to estimate differences in CD4+T-cell recovery in relation to specified determinants.

Results

cART was associated with a monthly rise of 15.7 cells/μL (p<0.001). Overall, age was not associated with CD4+T-cell recovery during TB therapy (p=0.655). However, among patients on cART, age-associated CD4+T-cell recovery rate varied by sex and nutritional status such that age <40 vs. ≥ 40 years predicted superior absolute CD4+T-cell recovery among females (p=0.006) and among patients with BMI≥18.5kg/m2 (p<0.001).

Conclusions

TB infected HIV-positive patients ≥ 40 years have a slower rate of immune restoration given cART-particularly if BMI>18.5kg/m2 or female. They may benefit from increased monitoring and nutritional support during cART.

Keywords: HIV, Nutritional Status, Immune-competence, Aging, HAART

INTRODUCTION

With expanded access to combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) for people living with HIV (PLWH), the goal of HIV disease management has shifted from delaying death to maintaining a high quality of life. The effectiveness of cART in PLWH is directly linked to its proven capacity to reverse HIV-associated immune deficiency as measured by the post-treatment rise in CD4+T-cells[1]. However, immune recovery is seldom complete for PLWH on cART[2]. The drivers of incomplete immune reconstitution given cART are poorly elucidated. In general, immunity is impacted by age, nutritional status, comorbid health conditions and lifestyle factors.

The impact of aging on immune function has been described[3]. With advancing age, the thymus involutes contributing to reductions in the population of naïve T-cellT-cells and a peripheral T-cell receptor repertoire that is skewed toward memory T-cellT-cells[4]. These functional changes in T-cell populations are compounded by a reduced capacity for generating T-cell precursors to seed the thymus and fewer naïve B-cell production at in the bone marrow, a lower quality of naïve T-cells produced from the thymus of older individuals, less potent antibodies to foreign antigens and a generalized chronic inflammatory state that develops with advancing age. Malnutrition is a driver of immune suppression and dysregulation[5], that may interact with age to interfere with immune responsiveness. Micro and macro nutrient deficiencies weaken the immune system partly through accelerated atrophy of the thymic and lymphoid tissue, alteration of T-cell subsets and cytokine response[6, 7].

Some epidemiologic studies have associated older age at HIV infection with faster progression to AIDS in the pre-ART era[8, 9]. However, results of investigations of age-associated differences in CD4+T-cell response for HIV-infected adults on HAART have been more variable in the context of cART[10, 11]. Some studies have found evidence for slower rate of CD4 recovery or lower magnitude of CD4+T-cell recovery in older compared to younger HIV-infected adults on HAART[12–18]. Others have found no age-related differences in CD4+T-cell recovery following ART initiation[19–22]and at least one study has reported a positive association between advanced age and enhanced CD4+T-cell recovery[23].

In areas of high HIV prevalence, malnutrition and food-insecurity overlap[5] even as those infected with HIV make the same survival gains with cART described in resource affluent settings[24]. These nutritional and age-related immune dysregulations may be both accelerated and magnified in HIV-infected populations due to HIV-related immune deficiency[25], age-related decline in thymic output[26, 27] and the high frequency of comorbid conditions that further aggravates immune alterations[28]. Yet, in spite of the biologically plausible expectation that malnutrition and advanced age in HIV-infected persons will unfavorably alter immune response to cART[29], there is limited empirical evidence that this occurs in PLWH provided cART.

How immune recovery following cART initiation is impacted by nutritional deficits and advanced age at cART initiation in sub-Saharan Africa where the burden of HIV lies is unclear[30]. CD4+T-cell recovery in African PLWH may be materially different from HIV-infected adults in developed countries due to a high frequency of comorbid infections[30–32], malnutrition and lower overall quality of supportive clinical services. Of note, as many as 33% of PLWH in resource limited high HIV prevalence SSA settings have comorbid TB disease[33]. Concurrent TB and HIV up-regulates immune activation and inflammation, complicates the diagnosis, presentation and clinical management of respective diseases [34]. A recent study from South Africa suggests that CD4+T-cell recovery rate is comparable for HIV-infected persons with and without TB[35]. However, the understanding of age-related differences in immune recovery for HIV and TB co-infected persons is limited. Therefore, we examine the age-related differences in the rate of immune recovery in HIV and TB co-infected adults observed during tuberculosis treatment with or without cART. Secondarily, we examine sex and nutritional status as candidate modifiers of age-associated change in CD4+T-Cell count during TB therapy to inform current understanding of immune recovery in TB and HIV-infected adults on cART. We hypothesize that immune recovery following ART initiation will decline with increasing age and may be contingent on nutritional status.

METHODS

Study Design, Parent Study & Population

This is a secondary analysis of differences in CD4+T-cell recovery rate among 13 – 60 years old HIV and TB co-infected patients during the time of pulmonary TB therapy with or without cART in Kampala, Uganda. Details of the design and findings of the parent study has been reported elsewhere[36]. Briefly, an open label randomized trial of simultaneous cART and TB treatment vs. immediate TB treatment with delayed cART till clinically indicated per standard of care was implemented between October 2004 and October 2008. At the time, the standard for TB care in HIV-infection included immediate TB treatment with ART initiated upon the development of an AIDS defining opportunistic infection and/or when absolute CD4+T-cell count dropped below 200 cells/μL. All participants were cART naïve, non-pregnant, without history of TB, free of World Health Organization (WHO) stage IV AIDS-defining condition and immune competent (i.e. CD4+T-cell count was ≥ 350 cells/μL) at enrollment. The present analysis includes all patients with two or more CD4 assessment (n=208) within the six months of follow-up from enrollment through the end of TB therapy.

Ethical Approval

The protocol for the parent study was approved by the institutional review boards of the University of Georgia, Case Western Reserve University, University of California, San Francisco, the Joint Clinical Research Center and the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology. The sponsors of the parent study were not involved in the design, implementation and interpretation of results for this analysis.

Follow-up, Measurements & Variable Definitions

At enrollment, standardized questionnaires were used to collect socio-demographic and health data. Study participants were evaluated monthly. Microscopic evaluation of TB disease clearance was done for each patient as needed and for all regardless of indication at months 0, 1, 2 and 5. HIV-1 RNA levels were measured using Roche Amplicor assay with a minimum detection level of 400 copies/μL at months 0, 1, 2 and 5.

Primary Outcome

Absolute CD4+T-cell count was measured monthly via flow cytometry and is the primary indicator of immune recovery. Absolute CD4+T-cell counts (in cells/μL) were evaluated as a linear variable with the outcome matrix including all repeated measures of CD4 for each patient given our observational study design[37].

Determinants: cART, age, malnutrition

cART status was defined on the basis of randomization to concurrent combination ART vs. placebo during TB treatment. Baseline age was defined categories (< =24, 25 – 29, 30 – 34, 35 – 39 and >= 40 years) and was used as an indicator of differences in thymus function at cART initiation. Malnutrition was defined as underweight, BMI <18.5, or normal, BMI ≥ 18.5 kg/m2. Viral load was defined as a time-varying covariate using the lag of log10 transformed RNA values. Time was defined in months and analyzed as a linear variable.

Confounders/Modifiers

Baseline factors considered potential confounders in this study included: sex (male vs. female), employment (yes vs. no), smoking (current, former vs. never), marital status (never married, divorced/separated/widowed vs. married) and baseline functional status defined using Karnofsky score ≥ 90 (i.e. able to normally function with minor signs of disease) vs. <90 (i.e. lower functional status).

Statistical Analyses

Multivariable random effects mixed linear regression models were fitted in Statistical Analyses Software (SAS) version 9.2. We assumed an unstructured covariance matrix to account for non-independence of repeated CD4+T-cell measurements within individuals and accounted for potential within-subject differences in the trajectory of CD4+T-cell change over time by including random intercept for individual patients. Empirical standard errors were used for all estimations to ensure that significance tests were robust to any mis-specification of the covariance matrix.

We considered an extensive array of potential confounders of the relationship between age and change in CD4 values. In addition to specified potential confounders, we adjusted for cART status, malnutrition, viral load, and time. Lack of information on any confounding covariate was addressed analytically using the missing indicator method. We examined the potential for modification in the association between age and change in CD4 during follow-up by patient sex and baseline underweight status. For this assessment, we used differences in likelihood ratio tests between nested models to determine the contribution of these factors – included in multivariate models as three-way interaction (age*time*sex or age*time*underweight) to improvement of the overall model fit and hence the presence of significant heterogeneity. When the p-value associated difference in likelihood ratio test between nested models is <0.05, we stratified by levels of the effect modifier.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

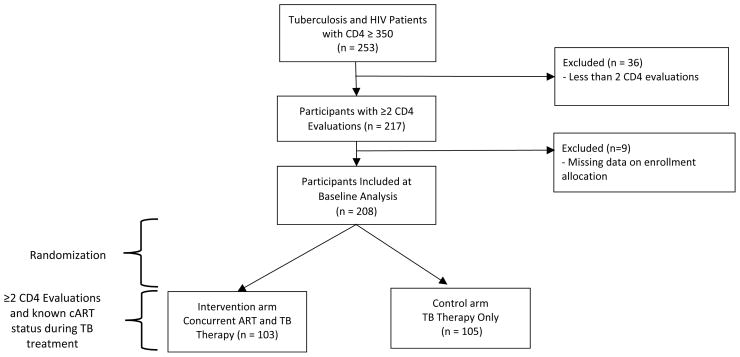

The parent study screened 253 HIV and TB co-infected patients for inclusion. Of these, 45 were excluded from this secondary analysis due to non-repeated CD4+T-cell assessment and inability to determine whether patient was allocated concurrent vs. non-concurrent cART in the parent study (Figure 1). The analytic sample included 208 individuals with slightly more males (57%) than females all with WHO HIV-HIV disease stage one or two at baseline. The average participant was 31.8 years old and the mean absolute CD4+T-cell count at enrollment was 573 cells/μL. At enrollment, 23.6%, 26.9%, 21.2%, 16.8% and 11.5% of the sample was <25, 25 – 29, 30 – 34, 35 – 39 and ≥40 years old respectively. The majority of participants (64.7%) were employed, 27% were current drinkers, 11% self-identified as current smokers and 40.8% had more than seven years of education (Table 1). There were no differences by age-group with respect to baseline health status indicators including: hemoglobin levels, CD4+T-cell count, log viral load, and body mass index. However, the proportion of female patients declined significantly with increasing age category (Table 2). The WHO HIV disease stage did not differ by age categories at enrollment (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Secondary Analysis Study of Randomized Clinical Trial of TB Therapy only versus Concurrent Antiretroviral and TB Therapy in HIV (CD4 ≥ 350) and TB infected Participants in Kampala, Uganda. 2004–2008.

Table 1.

Baseline Socio-demographic, Immunologic and Health Status of 208 HIV and Pulmonary Tuberculosis Infected Ugandans

| Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 31.8 | 7.9 |

| Baseline BMI (kg/m2) | 19.8 | 2.5 |

| Viral Load | 127708 | 195021 |

| Log Viral Load | 4.53 | 0.87 |

| Absolute CD4 cell count (cells/μL) | 572.3 | 243.4 |

| CD4 percent | 30.1 | 9.93 |

| Absolute CD8 cell count (cells/μL) | 877 | 476 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.1 | 1.8 |

| Baseline Alanine Serum Transferase | 31.4 | 22.3 |

| CD4:CD8 Ratio | 0.8 | 0.5 |

| n | % | |

| Randomized to HAART | 103 | 49.5 |

| Age categories (years) | ||

| <25 | 49 | 23.6 |

| 25 – 29 | 56 | 26.9 |

| 30 – 34 | 44 | 21.2 |

| 35 –39 | 35 | 16.8 |

| 40 + | 24 | 11.5 |

| Underweight (BMI <= 18.5 kg/m2) | 69 | 33.2 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Single/never Married | 30 | 14.6 |

| Currently Married | 98 | 47.6 |

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 78 | 37.8 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 118 | 56.7 |

| Female | 90 | 43.3 |

| Employed | 134 | 64.7 |

| Educational Status | ||

| 0 - P5 education | 57 | 30.1 |

| P6 - P7 education | 55 | 29.1 |

| S1 - S3 education | 36 | 18.9 |

| S4 - S6 education | 42 | 21.8 |

| Above Secondary Education | 18 | 9.4 |

| Behavioral Risk Factors | ||

| Current Alcohol drinker | 56 | 27.2 |

| Smoking status | ||

| Never | 146 | 70.2 |

| Former | 40 | 19.2 |

| Current | 22 | 10.6 |

| Baseline Health Status | ||

| Abnormal Indication on General Physical Exam | 130 | 62.5 |

| Normal Blood Pressure | 157 | 75.5 |

| Karnofsky score >= 90 | 83 | 39.9 |

| Presence of a Comorbid Dx | 82 | 40.0 |

| HIV WHO Stage | ||

| 1 | 4 | 2.1 |

| 2 | 188 | 97.9 |

Table 2.

Baseline Description of HIV and Pulmonary Tuberculosis Infected Study Participants By Age at Enrollment

| < 25 Years N = 49 |

25 – 29 Years N = 56 |

30 – 34 Years N = 44 |

35 – 39 Years N = 35 |

40+ Years N = 24 |

P-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute CD4+T-cell (Mean, SD) | 572 (250) | 558 (248) | 627 (251) | 561 (243) | 524 (206) | 0.6854 |

| Body Mass Index (Mean, SD) | 19.9 (2.7) | 20.0 (2.7) | 19.6 (2.5) | 19.7 (2.0) | 20 (2.8) | 0.8077 |

| Log Viral Load (Mean, SD) | 4.39 (0.85) | 4.58 (0.85) | 4.64 (0.85) | 4.64 (0.79) | 4.36 (1.1) | 0.6671 |

| Female n (%) | 29 (59.2) | 33 (58.9) | 14 (31.8) | 9 (25.7) | 5 (20.8) | <0.0001 |

| cART n (%) | 24 (49.0) | 32 (57.1) | 20 (45.5) | 17 (48.6) | 10 (42.7) | 0.4088 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 11.7 (1.7) | 11.9 (1.6) | 12.3 (1.8) | 12.4 (1.7) | 11.7 (2.1) | 0.3479 |

P-values are based on t-test of difference in means for continuous variables and chi-square test of difference in proportions for categorical variables.

During the six months of TB therapy, CD4+T-cell count increased by approximately 2 CD4+T-cells each month. However, among patients on TB therapy without cART, a net decline of 2.5 CD4+T-cells per month was observed whereas patients on concomitant TB therapy and cART gained approximately 8 CD4+T-cells each month in the overall group. Overall, and within treatment strata, nutritional status was not independently associated with CD4+T-cell recovery although underweight patients gained more cells per month in comparison to patients of normal weight at enrollment. Each log increment in HIV RNA viral load was associated with a net deficit in monthly absolute CD4+T-cell recovered but this association was not statistically significant overall or within strata of concurrent vs. delayed cART. Over the study period, women on average gained more CD4+T-cells per month compared to men in the overall sample. The magnitude and direction of sex-associated change in CD4+Tcells differed by cART status. Among study participants on concurrent cART and TB treatment, women gained nearly 24 more CD4+T-cells per month compared to men. On the other hand, among patients on TB treatment without cART, women in comparison to men lost approximately 7 CD4+ cells/μL per month (Table 3).

Table 3.

Monthly Change in Absolute CD4 cell count among HIV and Tuberculosis Co-infected Ugandan Adults During six-months of Tuberculosis Treatment in Relationship to Age, Concurrent cART, Sex, Nutritional status, Time and viral load

| ENTIRE SAMPLE (N = 208)** | TB Therapy Only, No ART N = 105 | Concurrent ART and TB Therapy; N = 103 | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Risk Difference (95% CI) | Risk Difference (95% CI) | Risk Difference (95% CI) | |

| Time (per month increment) | 1.87 (−6.7,10.5) | −2.5(−11.2, 6.1) | 8.2 (−5.0, 21.5) |

| BMI <18.5 vs. >=18.5 kg/m2 | 8.3 (−5.0, 27.0) | 8.7 (−10.8, 28.1) | 3.9 (−12.6, 20.4) |

| Female vs. male Sex | 10.7 (−3.72, 23.9) | −3.32 (−21.5, 15.0) | 23.7(−3.0, 50.4) |

| Viral Load (per log10 increment) | −3.54 (−7.7, 0.6) | −3.3 (−8.2, 1.6) | −2.0 (−7.2, 3.2) |

| Punctuated ART vs. standard of care | 16.3 (4.8, 27.8) | n/a | n/a |

| Age Categories (in Years) | P-value: age*time: 0.362 | P-value: age*time: 0.495 | P-value: age*time: 0.378 |

| <25 | 16.1 (−2.18, 34.4) | −2.9 (−23.9, 18.0) | 33.2 (4.25, 62.2) |

| 25 – 29 | 12.4 (−3.3, 28.0) | −1.8 (−20.7, 17.1) | 21.8(−1.0, 44.6) |

| 30 – 34 | 12.7 (−3.8, 29.3) | 9.2 (−11.8, 30.2) | 4.34 (−19.2, 27.9) |

| 35 – 39 | −5.3 (−27.1, 16.5) | −21.7(−51.0, 7.7) | 4.91 (−36.5, 46.3) |

| 40+ | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Interaction: age*time*ART; P-value = 0.0575 | |||

sample size in each column is based on unique individuals included in multi-variate analyses; numbers within age strata is derived from baseline file.

CI= confidence intervals. All effects are estimated from mixed general linear models using PROC Mixed in SAS version 9.2. Risk differences represent the average monthly change in absolute CD4 values in relation to shown predictors.

Age Effects are derived from the following model: [CD4it] = α + β1Time + β2Age + β3Time*Age + β4sex + β5baseline underweight status + β6lag viral load + β7*marital status + β8employment + β9smoking status.

BMI effect is derived from the following model: [CD4it] = α + β1Time + β2baseline underweight status + β3Time* baseline underweight status + β4sex + β5Age + β6lag viral load + β7*marital status + β8employment + β9smoking status.

: p-value, time*ART (entire cohort) <0.0001;

Effect of Age, Anti-Retroviral Therapy and Interactions with Sex and BMI

In the entire sample, cART use during TB treatment was associated with an average gain of 16 CD4+T-cell per month. Overall CD4+T-cell recovery rate was higher for 3 of 4 younger age categories in comparison to patients 40 years or older but these age-associated differences were not statistically significant. However, the magnitude and direction of age-associated differences in immune recovery may varied based on concurrent cART status (P-value = 0.027 from likelihood ratio test of differences in nested models with and without age*time*ART interaction; data not shown). Similarly, cART stratified find marginally significant qualitative age-associated interaction in CD4+T-cell recovery (Table 3, Age*time*ART interaction; P-value = 0.058). Among patients on concurrent cART and TB therapy, absolute CD4+T-cell count increased from enrollment through the end of 6 months of TB therapy by an average value of 8 CD4+T-cells/μL per month and patients in younger age-strata all gained more CD4+T-cells than those 40 years or older. The magnitude of CD4+T-cells recovered in patients on cART and TB treatment increased with younger age at enrollment. Conversely HIV-infected patients on solo TB therapy lost an average of 2.5 CD4+T-cells/μL monthly and the age-associated change in CD4 values was variable with a slower rate of recovery noted for only 1 of 4 younger vs. the oldest age-category.

The age-associated rate of immune-recovery during 6 months of TB treatment was dependent on baseline nutritional status (P-value: age*time*BMI: <0.0358) and sex (P-value: age*time*sex< 0.0001) among patients on concurrent TB and cART. Specifically, a faster rate of CD4 cell count recovery was noted for patients in the four younger age strata compared to oldest age category among female patients and among normally nourished patients at enrollment. As in the overall sample, the magnitude of CD4+T-cells recovered during TB therapy was inversely proportional patient age at enrollment. Conversely, the association between age and CD4+T-cell recovery was variable and non-significant for male patients and for patients underweight at enrollment (Table 4).

Table 4.

Nutritional Status and Sex Dependent Age-Related Monthly Increase in Absolute CD4 count in Tuberculosis and HIV Co-infected Patients on Concurrent Antiretroviral during Six Months of Tuberculosis treatments in Kampala, Uganda.

| Baseline Nutritional Status | Sex | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| BMI < 18.5 kg/m2 (n=36) | BMI >=18.5 kg/m2 (n =67) | Female (n = 50) | Males (n = 53) | |

| Risk Difference (95% CI) | Risk Difference (95% CI) | Risk Difference (95% CI) | Risk Difference (95% CI) | |

| Age Categories (Years) | Age*time: p = 0.954 | Age*time: p <0.001 | Age*time: p = 0.006 | Age*time: p = 0.795 |

| <25 | −1.5 (−30.9, 28.0) | 56.0 (22.8, 83.4) | 52.8 (18.7, 86.9) | 14.6 (−15.6, 44.7) |

| 25 – 29 | 17.3(−16.6, 49.2) | 50.2 (21.0, 73.2) | 53.7 (25.8, 81.4) | 5.2 (−19.6, 30.0) |

| 30 – 34 | 0.1(−41.1, 41.2) | 36.7 (8.2, 57.2) | 47.0 (11.6, 82.4) | 6.5 (−19.0, 32.1) |

| 35 – 39 | 14.6 (−21.6, 50.8) | 30.1 (−0.3, 60.4) | 26.5 (−21.7, 74.8) | −0.2 (−32.3, 31.9) |

| 40+ | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| P-value: age*time*BMI: =0.036 | P-value: age*time*sex = <0.001 | |||

Estimates are derived from linear mixed models implemented via SAS PROC Mixed. Model assumed an unstructured covariance for within subject repeated measures of CD4 values. All estimates are adjusted for time, patient sex and lag viral load.

DISCUSSION

In this sample of immune competent TB and HIV co-infected adult men and women followed through the end of anti-tuberculosis therapy -with or without ART, we found age-associated differential rise in CD4 during six months of TB therapy among patients on concurrent anti-tuberculosis and antiretroviral therapy but not in patients on tuberculosis treatment without cART. For patients on simultaneous TB and ART therapies, the average monthly CD4+T-cell gain was inversely proportional to age at enrollment. This inverse association between age at enrollment and in the absolute number of CD4+T-cells recovered was particularly strong and statistically significant among females HIV and TB co-infected adults whose BMI was ≥ 18.5 kg/m2 at enrollment.

In line with our study hypothesis age ≥ 40 years at ART initiation was associated with sub-optimal immune recovery rate relative to younger age-groups. Our results confirm the age-related sub-optimal immune recovery observed in adult HIV-infected patients from West Africa and South Africa[35, 38] as well as similar findings in several developed country settings[14, 16–18]. None of these prior studies have been done in HIV and TB co-infected patients. Thus our results corroborate these previous reports and suggests that co-infection with TB maynot alter the age-associated absolute CD4+T-cell recovery deficits previously reported.

Our data confirms the previously reported age-associated immune recovery deficits in mostly immune compromised HIV-infected adults and extends this observation to immune competent HIV-infected populations. Of note, there was no age-related difference in CD4+T-cell count at enrollment thus excluding the presence of lower CD4+T-cell count in older persons with HIV at the beginning of cART as an alternative explanations for this finding. The pattern of associations observed is in line with previous reports that CD4+T-cell immune recovery rate given cART may be more effective in younger PLWH in part due to relatively more preserved of thymic function[14].

Our finding of significant age-related differences in immune recovery is not corroborated by investigations among HIV-infected adults from Uganda [30, 31] and Barbados[39]. We note important methodological differences between these studies and ours that may partially explain this inferential divergence. Our study includes HIV and TB co-infected adults with adjustment for major known confounders/modifiers of immune function including: nutritional status and several socio-demographic factors. Further, we control for coincident TB infection by design allowing us to derive more thoroughly adjusted estimates of effect compared to these previous reports [30, 31].

Neither sex nor nutritional status were independent predictors of over-all immune recovery in this study. However, both factors modified the age-associated differentials in immune recovery rate. Our observation of age-related differences in immune recovery among nutritionally adequate but not underweight adults at ART initiation is noteworthy and suggests that any age-related immune recovery advantage conferred by preserved thymic function in younger HIV-infected adults is over-ridden by immune dysregulation due to nutritional impairment. The significance of stronger age-related deficits in immune recovery among women is less clear and warrants further elucidation in future studies. On the one hand, female sex may be a surrogate indicator of greater compliance or generally better health seeking behavior or health status at cART initiation that favorably impacts immune recovery rate during TB therapy. Several African studies have associated female sex with greater magnitude of immune recovery and greater overall adherence on ART[40, 41] suggesting that sex differentials in adherence to cART may be important.

In the present study, however, adherence to both TB and ART was similarly high for men and women because all were given directly observed therapy but underweight status was more prevalent in men than women at enrollment. We have previously reported sex differences in adiposity, TB-associated lean tissue wasting, and relationships to mortality among Ugandan adults[42]. The relative contribution of sex-related differences in metabolic dysregulation and of sex-related behavioral differences such as adherence drive the observed age-related differentials in CD4-recovery deserves further elucidation in future studies to inform effective intervention strategies.

Our study is subject to important limitations that should lead to cautious interpretation of our findings. First, the observational design of this study limits our ability to conclude that advanced age at enrollment leads to poor immune recovery. Second, our analysis includes a small sample of HIV and TB co-infected patients on concurrent ART and TB therapy. Consequently between 10 and 32 patients were in the five age-strata specified. Third, the significant association between advanced age and lower immune recovery rate noted in this study was evident in sub-group analyses. However, given smaller sample sizes in sub-group analyses, one would have expected less power to detect significant associations; this did not materialize in our study. Future studies are needed from resource limited settings with careful consideration of nutritional status and patient socio-demographic factors to confirm or refute these findings. The strengths of this study include: rigorous control for important confounders, evaluation of effect modification, and the use of a sample of HIV and TB infected adults that allows us to simultaneously contrast the differential impact of age on immune responses in the context of TB treatment only versus concomitant TB and ART.

In conclusion, we found that given cART, recovery of CD4+T-cells was age-dependent and that younger patients recovered their CD4+T-cells at a higher rate than older counterparts. Moreover, the rate of immune recovery was affected by gender and nutritional status. These findings suggest that age, sex, and nutritional status may be important determinants of health outcomes in HIV and TB co-infected adults. As a result, therapeutic approaches may need to be tailored by these factors. Our data suggests that increased monitoring and nutritional support as adjunct therapy should be considered for HIV-positive patients with TB and that those starting cART at older age may benefit from this intervention. The mitigation of malnutrition in TB and HIV co-infected patients is modifiable risk factors that may enhance immune recovery in adult PLWH on cART.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS FOR REVIEW.

Age was examined in relation to CD4+T-Cell rise in HIV-TB coinfected adults during cART.

Given cART, age-related CD4+T-cell recovery rate depended on sex and nutritional status.

Young age predicted CD4+T-cell rise among women and normally nourished patients.

Optimal nutrition in TB-HIV co-infected patients may enhance CD4+ T-cell recovery given cART.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (grant number AI51219) and Fogarty International Center, (grant number TW 00011) for the implementation of this study.

Drs. Maria Walusimbi-Nanteza and Harriet Mayanja-Kizza, and the PART study team for their conduct of the clinical trial upon which this analysis is based.

Dr. Alphonse Okwera and the Tuberculosis Clinic of the National Tuberculosis and Leprosy Control Programme, Wards 5&6, Mulago Hospital.

Footnotes

This work has been presented at the 2014 American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene conference in New Orleans, Louisiana.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

We declare no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Effros RB, Fletcher CV, Gebo K, Halter JB, Hazzard WR, Horne FM, et al. Aging and infectious diseases: workshop on HIV infection and aging: what is known and future research directions. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:542–553. doi: 10.1086/590150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaardbo JC, Hartling HJ, Gerstoft J, Nielsen SD. Incomplete immune recovery in HIV infection: mechanisms, relevance for clinical care, and possible solutions. Clin Dev Immunol. 2012;2012:670957. doi: 10.1155/2012/670957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dock JN, Effros RB. Role of CD8 T Cell Replicative Senescence in Human Aging and in HIV-mediated Immunosenescence. Aging Dis. 2011;2:382–397. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Justice AC. HIV and aging: time for a new paradigm. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 7:69–76. doi: 10.1007/s11904-010-0041-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sicotte M, Langlois EV, Aho J, Ziegler D, Zunzunegui MV. Association between nutritional status and the immune response in HIV + patients under HAART: protocol for a systematic review. Syst Rev. 2014;3:9. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-3-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cunningham-Rundles S, McNeeley DF, Moon A. Mechanisms of nutrient modulation of the immune response. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:1119–1128. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.04.036. quiz 1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marcos A, Nova E, Montero A. Changes in the immune system are conditioned by nutrition. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2003;57(Suppl 1):S66–69. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Belanger F, Meyer L, Carre N, Coutellier A, Deveau C. Influence of age at infection on human immunodeficiency virus disease progression to different clinical endpoints: the SEROCO cohort (1988–1994). The Seroco Study Group. Int J Epidemiol. 1997;26:1340–1345. doi: 10.1093/ije/26.6.1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Operskalski EA, Stram DO, Lee H, Zhou Y, Donegan E, Busch MP, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection: relationship of risk group and age to rate of progression to AIDS. Transfusion Safety Study Group. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:648–655. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.3.648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gebo KA. Managing HIV infection in middle aged and older populations. Aging Health. 2005;1:395–407. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silverberg MJ, Leyden W, Horberg MA, DeLorenze GN, Klein D, Quesenberry CP., Jr Older age and the response to and tolerability of antiretroviral therapy. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:684–691. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.7.684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goetz MB, Boscardin WJ, Wiley D, Alkasspooles S. Decreased recovery of CD4 lymphocytes in older HIV-infected patients beginning highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2001;15:1576–1579. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200108170-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manfredi R, Chiodo F. A case-control study of virological and immunological effects of highly active antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected patients with advanced age. AIDS. 2000;14:1475–1477. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200007070-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Viard JP, Mocroft A, Chiesi A, Kirk O, Roge B, Panos G, et al. Influence of age on CD4 cell recovery in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy: evidence from the EuroSIDA study. J Infect Dis. 2001;183:1290–1294. doi: 10.1086/319678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamashita TE, Phair JP, Munoz A, Margolick JB, Detels R, O’Brien SJ, et al. Immunologic and virologic response to highly active antiretroviral therapy in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. AIDS. 2001;15:735–746. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200104130-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grabar S, Kousignian I, Sobel A, Le Bras P, Gasnault J, Enel P, et al. Immunologic and clinical responses to highly active antiretroviral therapy over 50 years of age. Results from the French Hospital Database on HIV. AIDS. 2004;18:2029–2038. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200410210-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nogueras M, Navarro G, Anton E, Sala M, Cervantes M, Amengual M, et al. Epidemiological and clinical features, response to HAART, and survival in HIV-infected patients diagnosed at the age of 50 or more. BMC Infect Dis. 2006;6:159. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-6-159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bosch RJ, Bennett K, Collier AC, Zackin R, Benson CA. Pretreatment factors associated with 3-year (144-week) virologic and immunologic responses to potent antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;44:268–277. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31802c7e20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Orlando G, Meraviglia P, Cordier L, Meroni L, Landonio S, Giorgi R, et al. Antiretroviral treatment and age-related comorbidities in a cohort of older HIV-infected patients. HIV Med. 2006;7:549–557. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2006.00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cuzin L, Delpierre C, Gerard S, Massip P, Marchou B. Immunologic and clinical responses to highly active antiretroviral therapy in patients with HIV infection aged >50 years. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:654–657. doi: 10.1086/520652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patterson K, Napravnik S, Eron J, Keruly J, Moore R. Effects of age and sex on immunological and virological responses to initial highly active antiretroviral therapy. HIV Med. 2007;8:406–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2007.00485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greenbaum AH, Wilson LE, Keruly JC, Moore RD, Gebo KA. Effect of age and HAART regimen on clinical response in an urban cohort of HIV-infected individuals. AIDS. 2008;22:2331–2339. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32831883f9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knobel H, Guelar A, Valldecillo G, Carmona A, Gonzalez A, Lopez-Colomes JL, et al. Response to highly active antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected patients aged 60 years or older after 24 months follow-up. AIDS. 2001;15:1591–1593. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200108170-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bhavan KP, Kampalath VN, Overton ET. The aging of the HIV epidemic. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2008;5:150–158. doi: 10.1007/s11904-008-0023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.High KP, Brennan-Ing M, Clifford DB, Cohen MH, Currier J, Deeks SG, et al. HIV and aging: state of knowledge and areas of critical need for research. A report to the NIH Office of AIDS Research by the HIV and Aging Working Group. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;60(Suppl 1):S1–18. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31825a3668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gui J, Mustachio LM, Su DM, Craig RW. Thymus Size and Age-related Thymic Involution: Early Programming, Sexual Dimorphism, Progenitors and Stroma. Aging Dis. 2012;3:280–290. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kraft R, Fankhauser G, Gerber H, Hess MW, Cottier H. Age-related involution and terminal disorganization of the human thymus. Int J Radiat Biol Relat Stud Phys Chem Med. 1988;53:169–176. doi: 10.1080/09553008814550521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scrimshaw NS, SanGiovanni JP. Synergism of nutrition, infection, and immunity: an overview. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;66:464S–477S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/66.2.464S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adolfsson O, Meydani SN. Nutrition and the aging immune response. Nestle Nutr Workshop Ser Clin Perform Programme. 2002;6:207–220. doi: 10.1159/000061860. discussion 220–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hermans SM, van Leth F, Kiragga AN, Hoepelman AI, Lange JM, Manabe YC. Unrecognised tuberculosis at antiretroviral therapy initiation is associated with lower CD4+ T cell recovery. Trop Med Int Health. 2012;17:1527–1533. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hermans SM, Kiragga AN, Schaefer P, Kambugu A, Hoepelman AI, Manabe YC. Incident tuberculosis during antiretroviral therapy contributes to suboptimal immune reconstitution in a large urban HIV clinic in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10527. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seyler C, Anglaret X, Dakoury-Dogbo N, Messou E, Toure S, Danel C, et al. Medium-term survival, morbidity and immunovirological evolution in HIV-infected adults receiving antiretroviral therapy, Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire. Antivir Ther. 2003;8:385–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bruchfeld J, Correia-Neves M, Kallenius G. Tuberculosis and HIV Coinfection. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2015 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a017871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shankar EM, Vignesh R, Ellegard R, Barathan M, Chong YK, Bador MK, et al. HIV-Mycobacterium tuberculosis co-infection: a ‘danger-couple model’ of disease pathogenesis. Pathog Dis. 2014;70:110–118. doi: 10.1111/2049-632X.12108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schomaker M, Egger M, Maskew M, Garone D, Prozesky H, Hoffmann CJ, et al. Immune recovery after starting ART in HIV-infected patients presenting and not presenting with tuberculosis in South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;63:142–145. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318288b39d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nanteza MW, Mayanja-Kizza H, Charlebois E, Srikantiah P, Lin R, Mupere E, et al. A randomized trial of punctuated antiretroviral therapy in Ugandan HIV-seropositive adults with pulmonary tuberculosis and CD4(+) T-cell counts of >/= 350 cells/muL. J Infect Dis. 2011;204:884–892. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fitzmaurice GM, Laird NM, Ware JH. Modelling the Mean: Analyzing Response Profiles. Applied Longitudinal Analysis. 2004:122–132. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Balestre E, Eholie SP, Lokossue A, Sow PS, Charurat M, Minga A, et al. Effect of age on immunological response in the first year of antiretroviral therapy in HIV-1-infected adults in West Africa. AIDS. 2012;26:951–957. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283528ad4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kilaru KR, Kumar A, Sippy N, Carter AO, Roach TC. Immunological and virological responses to highly active antiretroviral therapy in a non-clinical trial setting in a developing Caribbean country. HIV Med. 2006;7:99–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2006.00347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sempa JB, Kiragga AN, Castelnuovo B, Kamya MR, Manabe YC. Among patients with sustained viral suppression in a resource-limited setting, CD4 gains are continuous although gender-based differences occur. PLoS One. 2013;8:e73190. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Muya AN, Geldsetzer P, Hertzmark E, Ezeamama AE, Kawawa H, Hawkins C, et al. Predictors of Nonadherence to Antiretroviral Therapy among HIV-Infected Adults in Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2014 doi: 10.1177/2325957414539193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mupere E, Malone L, Zalwango S, Chiunda A, Okwera A, Parraga I, et al. Lean tissue mass wasting is associated with increased risk of mortality among women with pulmonary tuberculosis in urban Uganda. Ann Epidemiol. 2012;22:466–473. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2012.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]