SUMMARY

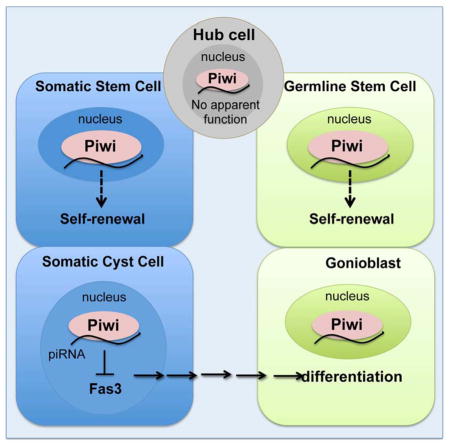

The Piwi-piRNA pathway is well known for its germline function, yet its somatic role remains elusive. We show here that Piwi is required autonomously not only for germline stem cell (GSC) but also for somatic cyst stem cell (CySC) maintenance in the Drosophila testis. Reducing Piwi activity in the testis caused defects in CySC differentiation. Accompanying this, GSC daughters expanded beyond the vicinity of the hub but failed to differentiate further. Moreover, Piwi deficient in nuclear localization caused similar defects in somatic and germ cell differentiation, which was rescued by somatic Piwi expression. To explore the underlying molecular mechanism, we identified Piwi-bound piRNAs that uniquely map to a gene key for gonadal development, Fasciclin 3, and demonstrate that Piwi regulates its expression in somatic cyst cells. Our work reveals the cell-autonomous function of Piwi in both somatic and germline stem cell types, with somatic function possibly via its epigenetic mechanism.

Keywords: Piwi, stem cell, somatic, germline, spermatogenesis

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Adult stem cells have the unique ability to self-renew and to differentiate into specific cell lineages. The balance between self-renewal and differentiation is controlled by both intra- and extracellular mechanisms (Lin, 2008). Studies on extracellular mechanisms in model systems have revealed the crucial role of the microenvironment of stem cells, termed stem cell niche, in stem cell self-renewal (Morrison and Spradling, 2008). The study on the niche in most tissues, however, has been hampered by the difficulty in defining its location, structure and function.

The Drosophila testis provides a genetically tractable model for studying adult stem cells and their respective niche, in part due to its well-defined spatial organization of stem cells and their microenvironment (de Cuevas and Matunis, 2011). At the most anterior tip of the testis, two stem cell populations can be found: germline stem cells (GSCs) and somatic cyst stem cells (CySCs). Both types of stem cells share a single niche that is composed of a group of somatic cells, called hub cells. The stem cells divide asymmetrically, such that the daughter stem cell maintains its contact with the hub, while the other daughter moves away and initiates differentiation. The immediate daughters produced by GSCs and CySCs are referred to as gonialblasts (GBs) and somatic cyst cells, respectively. As a GB migrates away from the niche, it undergoes four rounds of incomplete mitosis to produce a germline cyst containing 16 interconnected spermatogonia, followed by spermatocyte growth. Unlike GBs, somatic cyst cells are post-mitotic cells, whose sole function is to support germline cysts through their path to mature sperm (Kiger et al., 2000). Although recent work has provided insight into the crosstalk between somatic cyst cells and germ cells, the mechanisms remain poorly understood.

Piwi was initially discovered as a gene required for GSC maintenance in the Drosophila ovary (Lin and Spradling, 1997). It is the founding member of the evolutionary conserved Argonaute protein family (Cox et al., 1998), which is composed of Argonaute (Ago) and Piwi subfamilies. The Ago subfamily binds to siRNAs and miRNAs that ubiquitously exist in many tissues, whereas the Piwi subfamily binds to yet another class of small non-coding RNAs known as Piwi-interacting RNAs (piRNAs) that are generally regarded to function only in the germline (Juliano et al., 2011). A number of reports have shown that the Piwi subfamily is essential for transposon repression and genomic stability (Carmell et al., 2007; Sienski et al., 2012). Recently, high-throughput sequence analysis of piRNAs in Drosophila, murine testes, and Xenopus eggs, have revealed that a significant portion of piRNAs uniquely map to the 3′UTRs of specific genes, suggesting that Piwi activities may be extended to gene-coding regions (Robine et al., 2009; Saito et al., 2009). Furthermore, the Piwi-piRNA mechanism has been shown to regulate mRNAs at the post-transcriptional level (Rouget et al., 2010; Watanabe et al., 2014). All these advances, however, have underscored the germline-specific function of Piwi. Although Piwi and other piRNA components in Drosophila have been demonstrated to be involved in epigenetic programming in somatic cells (Brower-Toland et al., 2007; Huang et al., 2013; Yin and Lin, 2007) and in somatic signaling that maintains GSCs in the ovary (Cox et al., 1998; Qi et al., 2011), it remains unclear whether Piwi or the piRNA pathway have a developmental and/or physiological function in a somatic tissue.

To further explore the function of Piwi in somatic and germline tissues, we extended our analysis to the Drosophila testis. Here, we report that Piwi is required cell-autonomously not only for GSC but also for CySC maintenance. These analyses clearly demonstrate the function of a Piwi subfamily protein in somatic stem cells. In addition, we show that compromising Piwi function in the somatic cyst cell lineage causes an accumulation of early germ cells. This supports an important interaction between the somatic and germline stem cell lineages. Interestingly, reducing Piwi activity in hub cells did not affect stem cell maintenance or differentiation. Moreover, the nuclear localization of Piwi in cyst cells is required for somatic and germ cell differentiation, suggesting that Piwi may exert its function through an epigenetic mechanism. Finally, we show that Piwi exerts its somatic function at least by regulating the expression of Fasciclin 3 (Fas3), a gene important for somatic cell development in the gonad (Li et al., 2003), via Fas3-targeting piRNAs.

RESULTS

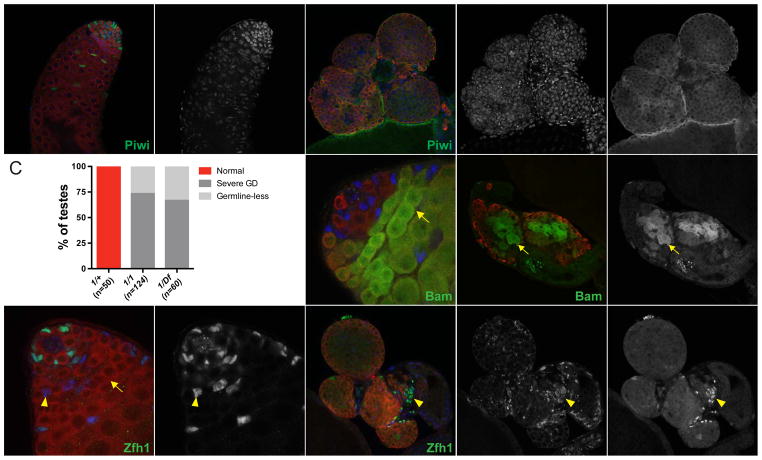

piwi mutants display defects in both somatic and germ cell lineages

Previous work has shown that piwi mutants display severe gonadal defects in both sexes (Cox et al., 1998; Lin and Spradling, 1997). To further characterize the piwi mutant testicular phenotype, we focused on a loss-of-function mutant allele, piwi1. In contrast to the piwi1/piwi+ control (Figure 1A–A′), we frequently observed an accumulation of early germ cells in homozygous piwi1 mutant adult testes (73%, n=124), as indicated by Vasa (a germline marker) and DNA staining (Figure 1B–B″). In addition, a minor population (27%) of piwi1 mutant animals was completely devoid of germ cells (germline-less) (Figure 1C). Interestingly, these persisting early germ cells expressed variable levels of Bam-GFP, which is normally repressed in GSCs/GBs but induced in transit amplifying spermatogonia (Figures 1D–E′). This finding implicates that piwi mutation results in defect in differentiation of amplifying spermatogonia. Contrary to GSCs, somatic cells are typically found in clusters and randomly distributed away from the germ cells, as judged by somatic lineage markers Zfh1 and Traffic jam (Tj, Figures 1F–G″). We ruled out the possibility that these phenotypic consequences were due to background mutations because piwi1/Df(2L)BSC mutants displayed pleiotropic defects similar to homozygous piwi1 mutants (Figure 1C). We also examined heteroallelic mutants that carried a hypomorphic allele, known as piwi2, in combination with piwi1. Interestingly, piwi1/piwi2 mutant animals rarely displayed an accumulation of early germ cells (18%, n=107; Figures S1C–D′). Instead the majority (51%) of mutant testes appeared unperturbed despite Piwi deficiency (Figures S1B–C), likely due to the hypomorphic nature of piwi2 allele. Similar to homozygous piwi1 mutants, a minor population (31%) of mutant testes was germline-less (Figures S1C, S1E–E′). Moreover, somatic cells were maintained in the absence of germ cells, but typically formed irregular clusters. These results suggest that hypomorphic mutations of piwi can alter the penetrance of germ cell differentiation defects in male gonads. Taken together, these data indicate that Piwi functions are essential for the earliest steps of spermatogenesis.

Figure 1. piwi mutants display defects in both somatic and germ cell lineages.

(A) Sibling control (piwi1/+). Piwi (green) is expressed in somatic and germ cell lineages. Note that DNA-bright cells are restricted to the apical end of testis (white bar). (B) a piwi1/piwi1 testis accumulates DNA-bright, Vasa-positive germ cells (red); Piwi expression is negligible in all cells (green, B″). (C) Frequency of testes from 0–5 day old adult flies that display a specified phenotype [germline defect, GD] in a given genotype. (D) piwi1/+; Bam-GFP/+ testis. Bam (green) accumulates in spermatogonia (yellow arrow), but not in GSCs/GBs (white arrows). (E) piwi1/piwi1; Bam-GFP/+ testis. Bam-negative and positive germ cells (white and yellow arrow, respectively in E′) accumulate throughout the testis. (F) Sibling control (piwi1/+). Zfh1 (green) accumulates at high levels in CySCs (white arrowhead) and Tj (blue, F′) accumulates in CySCs and early cyst cells. (G) piwi1/piwi1 testes typically have persisting Tj (blue, G′) and Zfh1-expressing somatic cells (green, G″) that are segregated from germ cells (yellow arrowhead). Tj marks the hub, CySCs and early cyst cells (blue in A–G, except B and E). Vasa marks germ cells (red in A–G). DAPI marks DNA (blue in A–B). Asterisk denotes the hub and the apical end of testes in piwi1/CyO and piwi1/piwi1, respectively. Scale bars: A, B, E, G, 25 μm and D, F, 10 μm. See also Figure S1.

Piwi expression in hub cells does not appear be essential for stem cell maintenance or differentiation

To begin to dissect the cell-type specific function of Piwi, we examined the expression of Piwi protein in adult testes. As reported previously (Cox et al., 2000), Piwi is a nuclear protein that is expressed in multiple somatic and germline cell types in the testes (Figures 2A–A′). Previous work in our lab demonstrated that, in the Drosophila ovary, Piwi exerts its niche signaling functions in the terminal filament and cap cells to maintain GSCs (Cox et al., 1998; Szakmary et al., 2005). Interestingly, Piwi expression appears the highest in hub cells (Figures 2A–A′) – the equivalent of cap cells in the Drosophila ovary. Hub cells have been shown to be niche signaling cells essential for GSC maintenance in the testis (Kiger et al., 2001). We therefore examined whether Piwi expression in hub cells is required for GSC self-renewal.

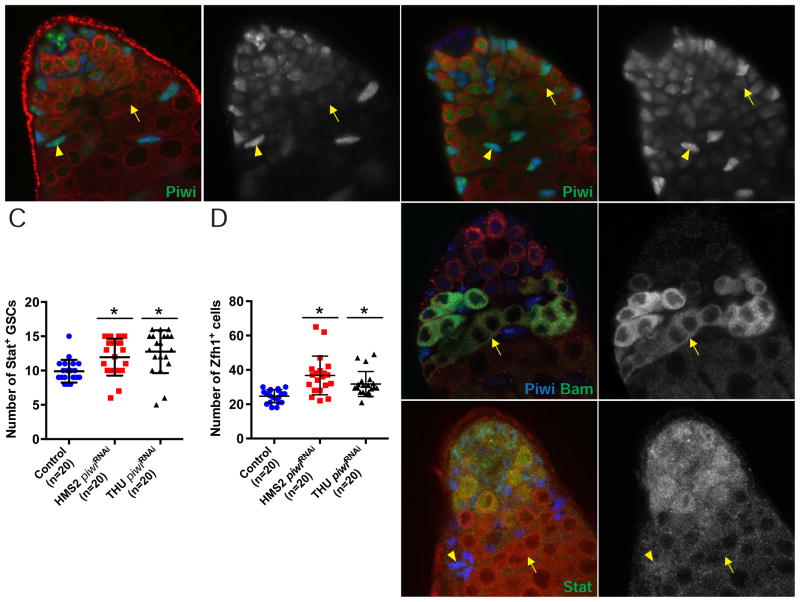

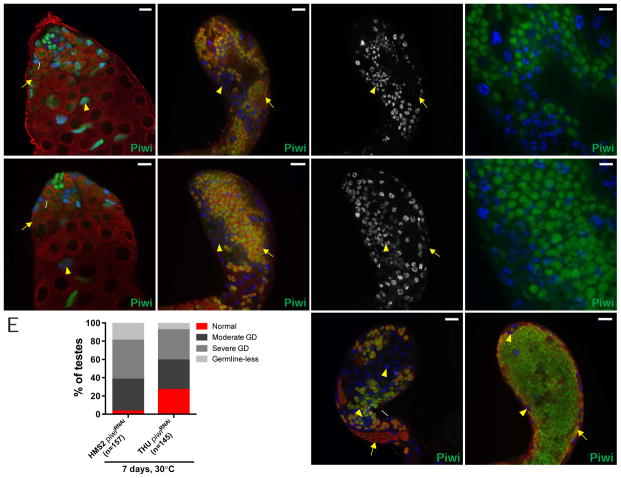

Figure 2. Knockdown of Piwi in the hub does not affect stem cell maintenance or differentiation.

(A) Control testes (Upd-Gal4; gfpRNAi) and (B, E) HMS2 piwiRNAi testes (Upd-Gal4; HMS2 piwiRNAi) from 7-day-old flies. (A) Piwi (green, A′) is expressed at high levels in the hub, GSCs (white arrow) and CySCs (white arrowhead). (B) Piwi expression (green, B′) is reduced in hub cells but levels remain unaffected in GSCs (white arrow) and CySCs (white arrowhead), including their daughter cells (yellow arrow and arrowhead, respectively). (C) Quantification of Stat-positive GSCs and (D) Zfh1-positive cells in testes with Piwi KD in hub cells (*p < 0.005). (E) Bam (green, E′) marks spermatogonia (yellow arrow) but not GSCs/GBs (white arrows) despite reduced levels of Piwi (blue) in hub cells. (F) 21-day-old flies. Stat (green, F′) accumulates in GSCs (arrow) and CySCs (arrowhead), but not their daughters (yellow arrow and arrowhead, respectively), despite Piwi KD in hub cells. Arrowheads and arrows mark the somatic and germ cells, respectively. Tj marks the hub, CySCs and early cyst cells (blue). Vasa marks germ cells (red). Asterisk denotes the hub. Scale bars: A–D, 10 μm. Error bars represent SD for each genotype.

We knocked down Piwi expression in hub cells using transgenic lines in each of which a UAS-piwi RNAi construct (HMS2 or THU, see Experimental Procedures) was driven by Unpaired (Upd)-Gal4. The Upd-Gal4 driver promotes expression of UAS constructs specifically in hub cells of the embryonic and adult gonad (Le Bras and Van Doren, 2006) (Figure S2A–A′). Both piwi RNAi constructs in combination with Upd-Gal4 was capable of efficiently knocking down Piwi protein in hub cells (Figures 2B–B′). Despite efficient Piwi reduction in the hub, spermatogenesis remained unperturbed. In 7-day-old males, resident stem cells were found adjacent to the hub and their differentiated progeny at the basal end of testes (Figure 2B–E′). In addition, the expression of Bam, a gene that is necessary and sufficient for germ cell differentiation (Gonczy et al., 1997), is suppressed in GSCs and GBs but induced in transit amplifying spermatogonia (Figures 2E–E′). These data indicate that germ cell differentiation progressed normally when Piwi level is greatly reduced in hub cells.

To closely examine whether Piwi reduction in the hub affects stem cell maintenance, we counted the number of Stat-positive GSCs and Zfh1-positive CySCs adjacent to the hub under Upd-Gal4 knockdown conditions. The average number of both GSCs and CySCs moderately increased 1.2- to 1.5- fold relative to that of controls (Figures 2C–D), indicating that stem cells populations are maintained despite Piwi knockdown in the hub. In 21-day-old males, KD testes were still morphologically normal and undergo spermatogenesis (87% of HMS2, n=46; 100% of THU, n=55) (Figure 2F). Moreover, the transcriptional activator of JAK-STAT signaling, pStat, accumulated in germline and somatic cells adjacent to the hub (Figure 2F–F′) (Kiger et al., 2001), indicating that resident stem cells were able to respond to the self-renewal signals emanating from the niche. Taken together, these results indicate that Piwi expression in hub cells is not required to support spermatogenesis.

Piwi is required autonomously for GSC and CySC maintenance

We next investigated the biological function of Piwi in GSCs and CySCs. To test whether Piwi is required autonomously in GSC maintenance, we generated negatively marked (GFP−) piwi mutant clones in adult testes using the FLP/FRT-mediated mitotic recombination. We counted the number of piwi mutant GSC clones over a time course post clonal induction (pci). Marked control GSC clones were observed adjacent to the hub in 43% (n=28), 36% (n=50), 30% (n=30), and 30% (n=33) of testes examined at 2, 4, 8, and 16 days post clonal induction (pci), respectively, indicating that control GSCs are maintained (Figure S2D–D′). In contrast, GSCs homozygous mutant for piwi1 were observed in 49% (n=68), 27% (n=64), 20% (n=79), and 3.5% (n=86) of testes examined over the same period of time, indicating that mutant GSC clones are gradually lost overtime (Figures S2E–F). In addition, piwi mutant germline clones that are located away from the hub appear to progress normally through differentiation without any apparent defects (Figure S2E–E′). These results indicate that Piwi is required autonomously for GSC maintenance, but may be dispensable at later developmental stages.

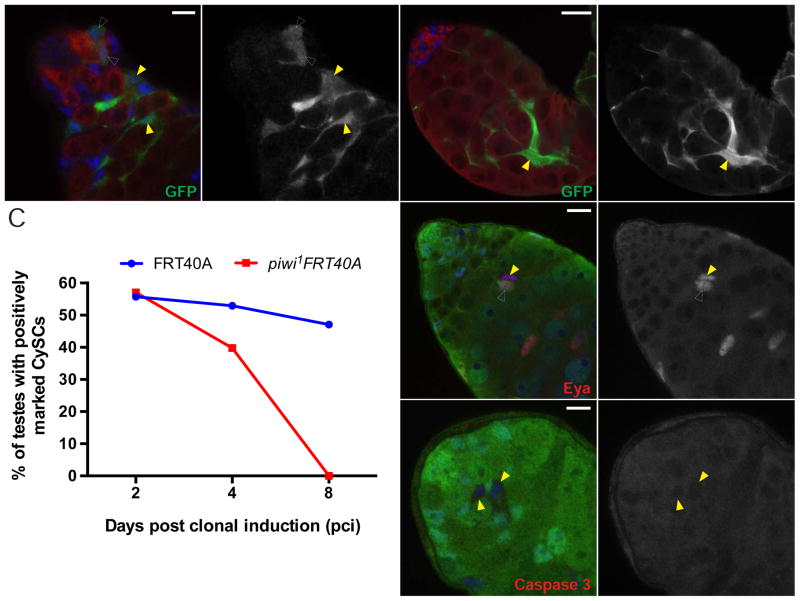

To address whether Piwi is required for CySC maintenance, we generated GFP-positive piwi mutant clones by using a mosaic technique known as MARCM. Marked control CySC clones were observed in 56% (n=61), 53% (n=87) and 47% (n=102) of testes examined at 2, 4, and 8 days pci, respectively (Figure 3C). In contrast, CySCs homozygous mutant for piwi1 were decreased by 4 days pci (40%, n=83), and no piwi1 mutant CySCs were identified 8 days pci (n=91) onwards (Figures 3A–C). Interestingly, marked piwi mutant cyst cells maintained their close association with germ cells (90%, n=50 at 8 days pci), suggesting that CySCs lacking Piwi do not die but rather differentiate. In support of this hypothesis, mutant cyst cell clones express Eyes absent (Eya), a marker for late cyst cell differentiation (Figure 3D–D′) (Fabrizio et al., 2003) but do not express activated Caspase 3, a marker for cells undergoing active apoptosis (Figure 3E–E′). Together, these results indicate that Piwi is required autonomously for CySC maintenance in adult testes.

Figure 3. Piwi is required autonomously for CySC maintenance in adult testes.

(A and B) MARCM piwi1 mutant clones can be identified by GFP (green). (A) Representative image at 2 days pci. Tj-positive CySCs mutant for piwi1 (white arrowheads) can be found next to the hub. Differentiated piwi1 mutant clones associate normally with Vasa-positive germ cells (yellow arrowheads). (B) Representative image at 8 days pci. piwi1 CySCs cannot be found in the niche, rather late cyst cells lacking piwi1 (yellow arrowhead) are found far from hub. (C) the percentage of control and piwi1 mutant CySC clones maintained at the niche post clonal induction (pci). (D and E) piwi1 mutant clones can be identified by lack of GFP (green). (D) Representative image at 4 days pci. piwi1 mutant clones found distal to the hub (yellow arrowhead) express Eya (red, D′), similar to unmarked clones (white arrowhead). (E) Representative image at 4 days pci. piwi1 mutant clones (yellow arrowheads) do not accumulate activated Caspase 3 (red, E). Tj marks the hub, CySCs and early cyst cells (blue in A–E). Vasa marks germ cells (red in A and B). Asterisk denotes the hub. Scale bars: A, 7.5μm; B, 25 μm; D, E, 10 μm. See also Figure S2 and S6.

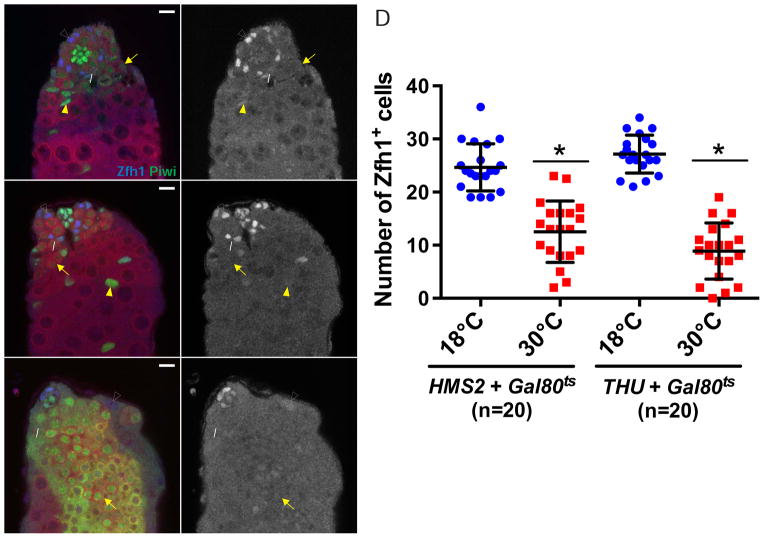

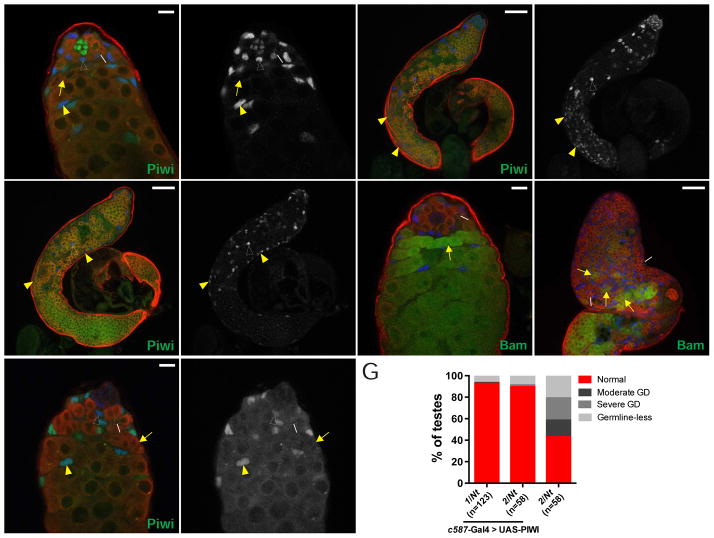

To further validate the intrinsic requirement for Piwi in CySCs, we used a temperature-sensitive allele of Gal80, a Gal4 inhibitor, to temporally control the expression of piwi RNAi constructs during adulthood (Lee and Luo, 1999). Gal80ts inhibits Gal4 activity at 18°C, but becomes inactive at 30°C. Thus, only when adult males were shifted to 30°C, piwiRNAi occurs in CySCs and their daughters as driven by Traffic jam (Tj)-Gal4 (Figure S2B–B′). As expected, testes of sibling controls maintained at either 18°C or 30°C were indistinguishable from those in wild-type (Figures 4A–B′). In contrast, testes from two different piwiRNAi fly strains (HMS2 and THU) that were shifted to 30°C for 20 days displayed a 2- to 3- fold reduction in the number of Zfh1-positive cells, a marker for CySCs and their immediate daughters (Leatherman and Dinardo, 2008), as compared with sibling controls (Figures 4C–D). These data also indicate that Piwi is required autonomously for CySC maintenance in adult testes.

Figure 4. Knockdown of Piwi in adult CySCs causes defects in somatic stem cell maintenance.

(A) Sibling control (18°C, Tj-Gal4/+; HMS2 piwiRNAi/Gal80ts). Zfh1-positive somatic cells (blue, A′) are found adjacent to the hub. Note that Piwi expression remains unaffected in CySCs and early cyst cells (white and yellow arrowhead, respectively). (B) Sibling control (+/+; HMS2 piwiRNAi/Gal80ts) at 20 days post temperature shift (pts). Same as (A). (C) Piwi KD in CySCs results in decrease of Zfh1-positive cells (blue, white arrowhead) adjacent to hub. Piwi-positive germ cells accumulate away from hub (green, yellow arrow), while GSCs are typically maintained adjacent to hub (white arrow). (D) Quantification of Zfh1-positive somatic cells in aged-matched sibling control (blue circles) and HMS2/THU piwiRNAi flies (red squares) maintained at 18°C or shifted to 30°C for 20 days, respectively (*p < 0.0001). Arrowheads and arrows mark the somatic and germ cells, respectively. Zfh1 marks CySCs and early cyst cells (blue). Vasa marks germ cells (red). Asterisk denotes the hub. Scale bars: A–F, 10 μm. Error bars represent SD for each genotype. See also Figures S4–S6.

Interestingly, Piwi-depleted adult cyst cells ectopically express Zfh1 far from the hub in a small fraction of testes examined (16% of HMS2, n=73; 19% of THU, n=52). However, the majority of KD testes maintained the organizational pattern of somatic lineage markers Zfh1, Tj, and Eya relative to sibling controls (81–84%). Moreover, Piwi-depleted adult cyst cells intermingled normally with germ cells in 94–98% of testes examined (Figure S4K–K′). Consistent with our previous findings (Figure 3), these data indicate that Piwi is not absolutely required for cyst cell differentiation in adult testes.

Piwi is also required for testicular formation prior to spermatogenesis

To further investigate the function of Piwi in the entire gonadal somatic lineage, piwi RNAi constructs were expressed starting in the precursors of CySCs before testicular formation using Tj-Gal4, which expresses Gal4 specifically in all somatic gonadal cells from embryonic to adult stages (Li et al., 2003) (Figure S2B–B′). Tj deficiency severely affects gonadogenesis, resulting in testes that contain only a few groups of pre-spermatocyte germ cells yet are filled with somatic cells that are segregated from the germ cells (Li et al., 2003). Similar to this phenotype, testes from Tj-Gal4 driven HMS2 and THU piwiRNAi flies typically become filled with Tj-positive somatic cells and Vasa-positive early germ cells (Figure 5). The association between cyst cells and germ cells was disrupted; the majority of Piwi-depleted cyst cells were located near the surface of the gonad and the interior was filled with Piwi-positive germ cells in 38% (HM2, n=157) and 44% (THU, n=145) of testes examined (Figures 5B′, 5D′, 5G). In 7-day-old piwiRNAi flies, Zfh1-positive cells were found far away from the hub in 73% (HM2, n=44) and 79% (THU, n=92) of testes examined (Figures S3B′, S3D′, S3F). We frequently observed Tj-positive cells proliferating far from the hub, as indicated by drastic increase in both EdU (Figures S3G–S3J′) and PH3 staining (Figures S3K–S3L′). Only at a low frequency, we were able to identify Eya-positive somatic cells, a marker for late cyst cell differentiation (Figures S3E–F′). This Tj-like phenotype indicates that Piwi has an important role in testicular morphogenesis.

Figure 5. Knockdown of Piwi in early somatic gonadal cells disrupts cyst cell and germ cell development.

(A) Control testes (Tj-Gal4; gfpRNAi). In the presence of gfp RNAi, Piwi expression (green) remains unaffected in somatic (blue, arrowheads) and germ cell (red, arrows) lineages. (B) HM2 piwiRNAi (Tj-Gal4; HMS2 piwiRNAi/+). Surface view of KD testis shows the accumulation of Tj-positive somatic cells (blue, arrowheads) and Vasa-positive germ cells (red, arrows) far from apical end. Persisting somatic cells are segregated from germ cells (blue, B′). Note that Piwi protein is undetectable in Tj-positive cells, but remains unaffected in germ cells. (B″) is a magnification of (B). (C) Sibling control (THU piwiRNAi/+). Same as (A). (D) THU piwiRNAi (Tj-Gal4/THU piwiRNAi). Same as (B). (D″) is a magnification of (D). ((E) Frequency of testes from 7-day-old flies that display a specific phenotype (germline defect, GD) in a given genotype. (F and G) Piwi KD testes displaying a moderate (F) and severe (G) germline defect phenotype, respectively. Note that the majority of Piwi-positive germ cells are found in the lumen of testis, whereas Piwi-negative somatic cells are located along the periphery. Arrowheads and arrows mark the somatic and germ cells, respectively. Tj marks the hub, CySCs and early cyst cells (blue). Vasa marks germ cells (red). Asterisk denotes the hub and apical end of testes in A, C and B, D, respectively. Scale bars: B″, D″, 10 μm; A–G, 25 μm. See also Figures S3–S6.

Piwi functions in CySCs and early cyst cells non-autonomously promote germ cell differentiation

It has been previously shown that defects in germline encystment by the CySC lineage can block the progression of spermatogonial cells, ultimately leading to the accumulation of early-stage germ cells (Lim and Fuller, 2012; Sarkar et al., 2007). Given that Piwi is required for adult CySC maintenance (Figures 3 and 4), we examined whether the loss of Piwi in the CySC lineage blocks early germ cell differentiation. Indeed, testes from piwiRNAi flies displayed an accumulation of early germ cells far from the hub, as judged by Piwi expression (Figures 5F–G). Moreover, analysis of various markers for germ cell differentiation supports that persisting germ cells display defective differentiation (Figure S4A–F′). For clarity, we classified piwiRNAi phenotypes into four categories based on the severity of germline defects: normal, moderate, severe, or germline-less. In 7-day-old piwiRNAi flies, early germ cells accumulated and occupied the bulk of the lumen in 43% (HMS2, n=157) and 33% (THU, n=145) of testes examined (Figures 5E and 5G). Among these testes, variable Bam expression and abnormal fusomes were observed in 100% of them (Figure S4A–D′). Within one week, the frequency modestly increased to 45% (HMS2, n=112) and 37% (THU, n=148), indicating that the severity of such defects may progress overtime. In addition, moderate germ cell differentiation defects were observed in 32–35% of testes examined, such that distinct clusters of Piwi-positive germ cells were found far from the hub, but spermatocytes were still present (Figures 5E–F). Similar to piwi1 mutant animals, germ cells were completely absent in 8–19% of testes examined (Figure 5E). Together, these data indicate that Piwi functions in the CySC lineage non-autonomously control germ cell differentiation and possibly GSC maintenance.

To confirm the above conclusion, we examined testes from flies carrying piwiRNAi in combination with Gal80ts shifted to 30°C for 10 or more days. Indeed, KD testes displayed various degrees of defects in germ cell differentiation, as judged by Piwi expression (Figure S4G–L). For example, at 15 days, moderate germ cell differentiation defects were evident in 36% of testes examined (HMS2, n=69) (Figure S4I, S4L), whereas 6% displayed severe germ cell differentiation defects (Figures S4K–L). Within the subsequent five days, the frequency of testes displaying severe germ cell differentiation defects increased substantially to 28% (Figure S4L), indicating that the severity of such defects progress overtime. Moreover, 10% and 5% of testes examined at 15 and 20 days, respectively, displayed complete loss of germ cells (Figures S4J, S4L). Similar results were obtained from THU piwiRNAi testes (Figure S4L). These data confirm that Piwi functions are required in adult CySCs and early cyst cells to promote germ cell differentiation.

Expression of Piwi in CySCs and early cyst cells rescues differentiation defects found in piwi1 mutants

To further validate that Piwi is required in CySCs and early cyst cells to promote germ cell differentiation, we examined whether Piwi expression is sufficient to rescue the piwi mutant phenotype. A wild-type Piwi construct was expressed specifically in hub cells, cyst cells, or germ cells in the piwi1 mutant background (Figure S2A–C′). Expectedly, Piwi expression in CySCs and early cyst cells, but not in the hub or germline, was sufficient to rescue both somatic and germ cell differentiation defects found in piwi1 mutant testes (Figure S5). 95% of rescued testes displayed a wildtype-like morphology (n=146; Figures S5B–C), as judged by Nomarski microscopy, DAPI staining, and the organizational pattern of Zfh1 and Eya3-expressing cells intermingling with germ cells (Figures S5D–E′). Furthermore, sibling controls that lacked wild-type Piwi displayed defects resembling homozygous piwi1 mutants (Figures S5A–A′, S5C). Together, these results indicate that Piwi expression in the CySC lineage is sufficient to control germ cell differentiation.

Piwi-mediated somatic induction of germ cell differentiation is independent of the EGFR signaling pathway

Since EGFR signaling in somatic cyst cells has been shown to regulate germline differentiation (Sarkar et al., 2007), we investigated whether Piwi functions through EGFR signaling. We examined the expression of pERK, an active form of MAPK, in Piwi KD somatic cyst cells. In control testes, pERK is expressed in most, but not all, somatic cyst cells (Figures S6A, S6C). Similarly, pERK expression is maintained in Piwi-deficient cyst cells despite the presence of germline defects (Figures S6B–B′, S6D–D′). Moreover, pERK expression is maintained in mutant cyst cells clones comparable to wild-type clones (Figures S6E–E″). Together, these data suggests that somatic Piwi function regulates germ cell differentiation independent of the EGFR/MAPK signaling pathway. These results are consistent with ovarian Piwi analysis (Ma et al., 2014).

Piwi nuclear localization in cyst cells is required for somatic and germ cell differentiation

Piwi proteins are known to regulate gene expression at epigenetic and post-transcriptional levels (Peng and Lin, 2013). To explore the mechanism underlying the spermatogenic function of Piwi, we took advantage of a mutation, piwiNt, that mislocalizes Piwi to the cytoplasm of Drosophila ovaries (Klenov et al., 2011). We verified that nuclear localization of PiwiNt protein is lost in all Piwi-expressing cells from male flies carrying heteroallelic combinations of piwiNt with piwi1 or piwi2 mutant alleles (Figures S7A–B′). Interestingly, as piwiNt mutant animals were aged to 10–15 days old, the entire testes become filled with Tj-positive cells, suggesting that cyst cells do not differentiate properly (Figures 6A–C′). Moreover, Tjpositive cells were found in large clusters segregated away from germ cells in 18% (piwi1/piwiNt, n=90) or 17% (piwi2/piwiNt, n=124) of testes examined (Figures 6B–C′), strikingly similar to the phenotypes described in piwi1 mutant and piwiRNAi animals. Thus, these data suggest that Piwi nuclear localization, likely reflecting its function in epigenetic regulation, is required for cyst cell differentiation, and possibly to facilitate somatic and germ cell interactions.

Figure 6. Piwi nuclear localization in cyst cells is required for somatic and germ cell differentiation.

(A) Sibling control (piwiNt/+) and (B and C) piwi1/piwiNt testis from 10–15 day old flies. (A) Piwi protein (green) localizes in the nuclei of somatic and germ cells (arrows and arrowheads). (B) Surface view of mutant testis shows accumulation of Tj-positive somatic cells far from apical end (blue, B′). Small clusters of germ cells (red) are typically found near surface of the gonad. (C) Cross section of mutant testis shows accumulation of Vasa-positive germ cells (red) in the lumen. Majority of Tj-positive somatic cells are located along the periphery (C′, yellow arrowheads); however, Tj-positive cells can be found associated with germ cells (white arrowhead). (D) Sibling control (piwiNt/+; Bam-GFP/+). (E) piwi2/piwiNt; Bam-GFP/+. Bam-GFP (green) accumulates in most excess germ cells (yellow arrows), but large grouping of germ cells that do not express Bam protein are present (white arrows). (F) Rescued testis (c587-Gal4; piwi1/piwiNt; UAS-PIWI/+) from 20–25 day old flies. Forced expression of wild-type Piwi in cyst cells rescues somatic and germ cell differentiation defects found in piwiNt mutant testes. (G) Frequency of testes that display a specified phenotype (GD: germline defect) in a given genotype from 20–25 day old flies. In all panels, arrowheads and arrows mark the somatic and germ cells, respectively. Tj marks the hub, CySCs and early cyst cells (blue). Vasa marks germ cells (red). Asterisk denotes the hub and apical end of testis in A, D and B, C, respectively. Scale bars: A, D, F, 10 μm; B, C, E, 50μm. See also Figure S7.

In the germline, DNA-bright early germ cells occupied the bulk of the lumen in piwiNt mutants (Figure S7F–F′). More specifically, 34% (piwi1/piwiNt, n=90) or 37% (piwi2/piwiNt, n=124) of mutant testes examined displayed severe germ cell differentiation defects (Figure S7C). Persisting germ cells expressed variable levels of Bam-GFP, indicative of defective germ cell differentiation (Figure 6E). In addition, 32% of testes examined displayed moderate germ cell differentiation defects (Figures S7C–D). Moreover, 8–10% of mutant testes were devoid of germ cells (Figures S7C, S7E). These data indicate that Piwi nuclear localization in somatic and/or germ cells is required for germ cell differentiation and possibly GSC maintenance.

The pleotropic defects observed in piwiNt mutants closely resemble testes from Tj-Gal4 driven piwiRNAi flies (cf. Figure S7 and Figure 5). This raised the possibility that differentiation defects may be due to the loss of somatic Piwi function. To test this hypothesis, wild-type Piwi was expressed specifically in cyst cells of the piwiNt mutant background (Figure S2C–C′). As expected, rescue of the piwiNt phenotype was observed in 98% (piwi1/piwiNt, n=63; piwi2/piwiNt, n=107) of testes examined from 10–15 day old flies. Moreover, rescue of piwiNt phenotypes was still observed in 93% (piwi1/piwiNt, n=123) or 90% (piwi2/piwiNt, n=58) of testes examined from 20–25 day old flies (Figures 6F–G), indicating that the rescued phenotype was maintained through adulthood. In contrast, testes from sibling controls that do not contain wild-type Piwi display pleiotropic defects similar to piwiNt flies (piwi2, n=58; Figure 6G). Together, these data indicate that Piwi nuclear localization in somatic cyst cells is sufficient for somatic and germ cell differentiation.

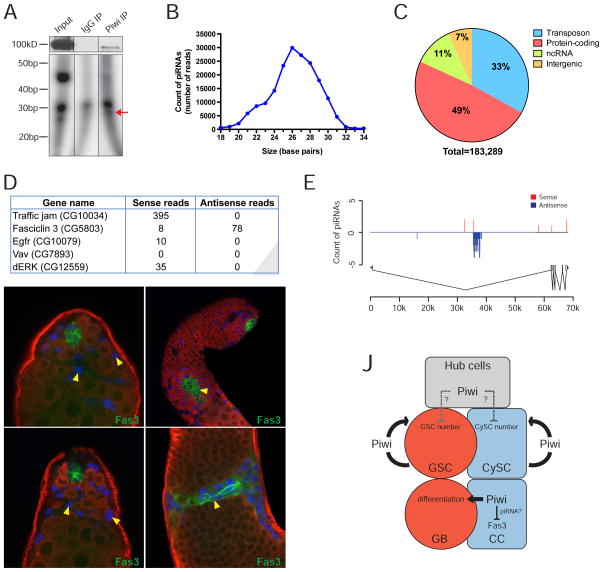

Piwi and piRNAs regulate Fas3 in somatic cyst cells

To explore the molecular mechanism underlying Piwi function in the testis, piRNAs bound to Piwi were isolated by immunoprecipitation using an anti-Piwi antibody (Figure 7A), followed by deep sequencing (see Supplementary Information). The length of Piwi-associated piRNAs in the testis peaks at 26 nt (Figure 7B), similar to Piwi-associated piRNAs in ovaries (Brennecke et al., 2007) and from whole flies (Yin and Lin, 2007). While the majority of piRNAs associated with Piwi in ovaries and whole flies are derived from retrotransposons (Brennecke et al., 2007), only 33% of the testicular piRNAs are derived from transposable elements in testes (Figure 7C). Interestingly, many Piwi-associated piRNAs in the testis were derived from protein-coding genes (49%), including Tj (Figure 7C–D). Particularly, we found that the first intron of Fas3, a gene that encodes for an adhesion molecule, generates piRNAs that are antisense to, and therefore may target, the Fas3 mRNA (Figure 7D–E). However, no anti-sense piRNA was found to target the key components of the EGFR signaling pathway (Figure 7D), consistent with our observation that somatic Piwi signaling to the germline is independent of the pathway (Figure S6).

Figure 7. Piwi and piRNAs regulate Fas3 in somatic cyst cells.

(A) Small RNAs associated with Piwi in adult testes were immunoprecipitated (IP) using anti-Piwi antibody. RNA molecules extracted from the immunoprecipitated complexes were visualized by 32P-ATP labeling on denaturing acrylamide gel. Piwi-bound small RNAs is visualized (red arrow). (B) Size profile of all mapped small RNAs, excluding miRNAs and abundant cellular RNAs, such as rRNA and tRNA. (C) Pie-chart for the annotation of all mapped small RNAs, excluding abundant cellular RNAs and miRNAs. (D) Summary of piRNA targeting for selected genes. Up to 1 mismatch was allowed. (E) piRNA distribution along Fas3 gene. Red and blue signal represents sense and antisense piRNAs, respectively. Up to 1 mismatch was allowed. UTR, CDS, and intron of Fas3 are shown. (F) Control testes (Tj-Gal4; gfpRNAi). Fas3 is expressed in hub cells (*), but not in cyst cells (arrowheads). (G) Tj-Gal4/+; HMS2 piwiRNAi/+. Piwi-depleted cyst cells ectopically express Fas3 far from the hub (arrowhead). Note that Fas3 is still maintained in hub cells (*). (H) Sibling control (piwiNt/+). Same as (F). (I) piwi1/piwiNt testis. Same (G). Scale bars: F, H, I, 10 μm; G, 50μm. (J) Model for Piwi function in the testicular stem cell niche. Piwi is required cell-autonomously for GSC and CySC maintenance. Piwi in the hub might regulate stem cell numbers (dotted-dash lines). Piwi in cyst cells (CC) non-autonomously control germ cell differentiation (arrow). Piwi and possibly piRNAs regulate Fas3 in cyst cells. See also Figure S6.

Fas3 has been shown to mediate cell sorting (Chiba et al., 1995; Elkins et al., 1990) yet piwi mutants display failure of cell mixing between somatic and germ cell lineages (Figures 1 and 5). We therefore examined whether Fas3 is regulated by Piwi in the testis. We took advantage of piwiRNAi to knockdown Piwi in somatic cyst cells and assessed Fas3 protein levels in these cells. In wild-type testis, Fas3 is expressed in the hub, but is undetectable in cyst cells (Figure 7F). Remarkably, the majority of KD testes (65%, n=54) displayed ectopic Fas3 expression in cyst cells found far from the hub (Figure 7G). This indicates that Piwi suppresses Fas3 expression in somatic cyst cells, presumably via the Fas3-targeting piRNAs. Moreover, 40% of piwiNt mutant testes also displayed ectopic Fas3 expression in cyst cells (n=147; Figure 7I). This further suggests that Piwi nuclear localization may be required for repression of Fas3 expression.

DISCUSSION

Over the past decade, much effort has been focused on identifying the molecular activities of Piwi in the germline of Drosophila and vertebrate model organisms, yet its somatic function remains elusive. The work presented here highlights the essential function of Piwi as a cell-autonomous regulator for the self-renewal of a somatic stem cell type and its parallel function for GSCs (Figure 7J). In addition, it reveals that somatic Piwi function regulates Fas3 expression, likely through the Piwi-piRNA pathway. This might be a mechanism to ensure the coordinated division, differentiation, and interaction of two stem cell lineages within an organ for proper organogenesis.

Piwi appears to be dispensable in hub cells for stem cell maintenance and differentiation

Previously, we have reported that Piwi functions in the niche cells of the Drosophila ovary to promote GSC maintenance (Cox et al., 1998; Szakmary et al., 2005). Surprisingly, we found that Piwi reduction in hub cells did not affect the maintenance of resident stem cells or their differentiation. We cannot rule out the possibility that Piwi KD is insufficient to disrupt its function. However, this is unlikely, considering that Upd-Gal4 begins its expression in the embryonic gonad (Le Bras and Van Doren, 2006); thus, the hub has experienced reduced levels of Piwi as soon as it is formed. Moreover, restoring wild-type Piwi solely in the hub was insufficient for rescuing differentiation defects found in mutant testes. Thus, it is quite possible that Piwi functions are not essential in the hub for stem cell maintenance or differentiation.

Cell-autonomous function of Piwi in stem cell maintenance

Our data indicate that Piwi is required autonomously for stem cell maintenance. Using clonal analysis, we show that piwi1 mutant GSCs and CySCs cannot be maintained at the hub. Furthermore, temporal-specific knockdown of Piwi in adult CySCs causes a significant reduction in somatic stem cell populations. Thus, this study clearly demonstrates the cell-autonomous role of Piwi in adult stem cells. Our data complement previous studies with respect to GSCs, because in the Drosophila ovarian system, Piwi was known to be required autonomously for GSC self-renewal (Ma et al., 2014). Moreover, this cell-autonomous function is particularly novel with respect to CySCs, since it represents the clear demonstration of a developmental function of Piwi in a somatic stem cell type. The somatic function of Piwi proteins has been recently reported in Hydra, a basal eukaryote (Juliano et al., 2014). A number of reports have also correlated Piwi proteins with cancer cell proliferation in various somatic tissues (Ross et al., 2014), yet the causal relationship or underlying mechanism has not been demonstrated. Given the highly conserved molecular mechanism mediated by Piwi proteins during evolution, the cell-autonomous function of Piwi in stem cells may also be conserved for human somatic stem cells, with implications in cancer.

Cell-autonomous function of Piwi in somatic cyst cell development

This study revealed a critical role for Piwi in regulating four distinct aspects of somatic cyst cell development. First, when Piwi was knocked down starting from somatic gonadal cells, the testis display defects in cyst cell development that closely resemble the testicular phenotype of Tj, a gene in the Piwi-piRNA pathway (Li et al., 2003; Saito et al., 2009). As the Tj phenotype is due to its function in gonadogenesis, our results indicate that Piwi functions are critical in somatic gonadal cells prior to spermatogenesis. Second, Piwi is required in CySCs for their maintenance, as mosaic analysis (Figure 3) and piwi RNAi (Figure 4) result in loss of somatic stem cell populations. Third, Piwi regulates cyst cell differentiation, as Piwi-depleted cyst cells retain stem cell characteristics far from the hub (Figure S3). Fourth, Piwi may promote the intermingling of cyst cells and germ cells, as Piwi-depleted cyst cells typically did not mix with germ cells (Figure 5). Our analysis suggests that the latter two Piwi functions may be restricted to the developing male gonad and might be interrelated. Thus, Piwi may have different biological roles during different stages of testicular development and spermatogenesis.

Piwi acts in somatic cyst cells to control germ cell differentiation via an EGFR-independent pathway

Several reports have demonstrated that defects in germline encystment causes spermatogenic arrest (Sarkar et al., 2007). Interestingly, loss of Piwi functions in cyst cells during development and adulthood results in the accumulation of mitotically active germ cells. Moreover, Piwi expression in somatic cyst cells, but not in the hub or germline, was capable of rescuing somatic and germ cell differentiation defects of piwi mutants. Our analysis suggest that Piwi-mediated somatic induction of germ cell differentiation appears to be independent of EGFR signaling, similar to fly ovaries (Ma et al., 2014). Recently, Piwi was shown to be required in ovarian escort cells, the functional equivalence of somatic cyst cells in Drosophila testes, to promote ovarian germline cyst differentiation (Jin et al., 2013; Ma et al., 2014), even though testicular somatic cyst cells are replenished via stem cell division whereas ovarian escort cells are replaced by self-duplication (Kirilly et al., 2011). These results suggest that Piwi is a critical somatic factor capable of controlling germ cell behavior in both sexes.

Piwi appears to epigenetically regulate cyst cells to instruct germ cell differentiation

Among the three Drosophila Piwi proteins, Piwi is the only nuclear protein, the only protein that is expressed in both somatic and germ cell lineages, and the only protein implicated in epigenetic regulation (Cox et al., 2000; Huang et al., 2013; Yin and Lin, 2007). The differentiation defects observed in approximately two-thirds of testes from piwiNt mutants indicate the crucial requirement of Piwi nuclear localization for somatic and germ cell differentiation. Since the known mechanism of Piwi in the nucleus is epigenetic regulation, our findings suggest that Piwi achieves its function in the somatic cells likely via epigenetic regulation. This is in contrast to its role during oogenesis, which does not require the nuclear localization of Piwi (Klenov et al., 2011). However, the analysis by Klenov et al. (2011) only covered 1–5 day old female flies, which might be too soon to reveal similar oogenic defects.

The pleiotropic defects observed in piwiNt mutants were nearly identical to the phenotypic consequence of Tj-Gal4 driven Piwi knockdown, indicating that the epigenetic regulation of Piwi may occur in early somatic gonadal cells during gonadogenesis. As Piwi expression in somatic gonadal cells of the piwiNt mutant background was sufficient to restore spermatogenesis to wildtype-like condition, this study uncovers the nuclear, and thus likely epigenetic, function of Piwi in gonadogenesis and spermatogenesis.

Piwi and piRNA association in fly testes

Piwi proteins associate with a variety of piRNAs in Drosophila and mammalian testes, including transposon and non-transposon piRNAs (Nishida et al., 2007; Watanabe et al., 2015). In Drosophila ovarian somatic cells, piRNAs derived from 3′UTR of Traffic jam has been proposed to target Fas3, suggesting a connection between Piwi and silencing of the Fas3 gene (Saito et al., 2009). Our work further demonstrates that Piwi is associated with Fas3-targeting piRNAs and that Piwi regulates Fas3 in somatic cyst cells in vivo, which in turn might be important for gonadogenesis and spermatogenesis. It has been suggested that Piwi achieves epigenetic programming of euchromatic genes by forming Piwi-piRNA complexes that bind to the nascent transcripts of target genes, which in turn recruits epigenetic factors such as Heterochromatin Protein 1a and Su(var)3-9 histone methyltransferase (Brower-Toland et al., 2007; Huang et al, 2013). Because the nuclear localization of Piwi is required to suppress Fas3 expression, we speculate that this suppression may be achieved by epigenetic regulation of the Fas3 gene via the nuclear Piwi-piRNA complex targeting of the Fas3 nascent transcript that is still tethered to the gene. This targeting would require antisense piRNAs and is quite specific because we were unable to find an antisense piRNA that maps to genes involved in EGFR signaling (Figure 7D). This is consistent with our observation that Piwi deficiency does not affect the EGFR signaling pathway. Given the well conserved molecular mechanism of Piwi, its known function in somatic cells in lower eukaryotes, and the correlation between ectopic expression of Piwi proteins and human cancers (Juliano et al., 2014; Rajasethupathy et al., 2012; Ross et al., 2014), it is tempting to speculate that the biological functions of Piwi reported here both in the soma and in the germline may be conserved during evolution.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

RNAi of piwi

For piwi RNAi, transgenic flies carrying three different RNAi constructs (HMS1, HMS2, and THU) were expressed specifically in somatic gonadal cells during gonadogenesis throughout adulthood using Traffic (Tj)-Gal4 (Li et al., 2003) (Figure S3B). Testes from Tj-Gal4 driven HMS2 and THU piwiRNAi flies displayed a Tj-like phenotype (see Results), indicating that Piwi has an earlier role in gonadogenesis. However, testes from Tj-Gal4 driven HMS1 flies were typically devoid of Zfh1-positive somatic cells, indicating that somatic expression of HMS1 piwiRNAi causes cell-lethality. As HMS1 driven by Upd-Gal4 also resulted in lethality, more severe than strong piwi mutant phenotype, HMS1 likely has a side genetic effect beyond reducing piwi expression. Thus, we used HMS2 and THU but not HMS1 flies for piwi RNAi.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank E. Bach, S. DiNardo, D. McKearin, T. Xie, and the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center for flies; R. Lehmann, M. Siomi, D. Godt, and the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank for antibodies; J. Peng and V. Gangaraju for valuable comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by NIH grant DP1CA174416 and the Mathers Foundation.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.G. and H.L. planned the experiments. J.G. performed the experiments. H.Q. performed Piwi-IP and prepared RNA for deep sequencing. N.L. performed bioinformatic analysis. J.G. and H.L. analyzed data and wrote the manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Brennecke J, Aravin AA, Stark A, Dus M, Kellis M, Sachidanandam R, Hannon GJ. Discrete small RNA-generating loci as master regulators of transposon activity in Drosophila. Cell. 2007;128:1089–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brower-Toland B, Findley SD, Jiang L, Liu L, Yin H, Dus M, Zhou P, Elgin SC, Lin H. Drosophila PIWI associates with chromatin and interacts directly with HP1a. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2300–2311. doi: 10.1101/gad.1564307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmell MA, Girard A, van de Kant HJ, Bourc’his D, Bestor TH, de Rooij DG, Hannon GJ. MIWI2 is essential for spermatogenesis and repression of transposons in the mouse male germline. Dev Cell. 2007;12:503–514. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiba A, Snow P, Keshishian H, Hotta Y. Fasciclin III as a synaptic target recognition molecule in Drosophila. Nature. 1995;374:166–168. doi: 10.1038/374166a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox DN, Chao A, Baker J, Chang L, Qiao D, Lin H. A novel class of evolutionarily conserved genes defined by piwi are essential for stem cell self-renewal. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3715–3727. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.23.3715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox DN, Chao A, Lin H. piwi encodes a nucleoplasmic factor whose activity modulates the number and division rate of germline stem cells. Development. 2000;127:503–514. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.3.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Cuevas M, Matunis EL. The stem cell niche: lessons from the Drosophila testis. Development. 2011;138:2861–2869. doi: 10.1242/dev.056242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkins T, Hortsch M, Bieber AJ, Snow PM, Goodman CS. Drosophila fasciclin I is a novel homophilic adhesion molecule that along with fasciclin III can mediate cell sorting. The Journal of cell biology. 1990;110:1825–1832. doi: 10.1083/jcb.110.5.1825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabrizio JJ, Boyle M, DiNardo S. A somatic role for eyes absent (eya) and sine oculis (so) in Drosophila spermatocyte development. Developmental biology. 2003;258:117–128. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00127-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonczy P, Matunis E, DiNardo S. bag-of-marbles and benign gonial cell neoplasm act in the germline to restrict proliferation during Drosophila spermatogenesis. Development. 1997;124:4361–4371. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.21.4361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang XA, Yin H, Sweeney S, Raha D, Snyder M, Lin H. A major epigenetic programming mechanism guided by piRNAs. Dev Cell. 2013;24:502–516. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Z, Flynt AS, Lai EC. Drosophila piwi mutants exhibit germline stem cell tumors that are sustained by elevated Dpp signaling. Curr Biol. 2013;23:1442–1448. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juliano C, Wang J, Lin H. Uniting germline and stem cells: the function of Piwi proteins and the piRNA pathway in diverse organisms. Annu Rev Genet. 2011;45:447–469. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110410-132541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juliano CE, Reich A, Liu N, Gotzfried J, Zhong M, Uman S, Reenan RA, Wessel GM, Steele RE, Lin H. PIWI proteins and PIWI-interacting RNAs function in Hydra somatic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:337–342. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320965111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiger AA, Jones DL, Schulz C, Rogers MB, Fuller MT. Stem cell self-renewal specified by JAK-STAT activation in response to a support cell cue. Science. 2001;294:2542–2545. doi: 10.1126/science.1066707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiger AA, White-Cooper H, Fuller MT. Somatic support cells restrict germline stem cell self-renewal and promote differentiation. Nature. 2000;407:750–754. doi: 10.1038/35037606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirilly D, Wang S, Xie T. Self-maintained escort cells form a germline stem cell differentiation niche. Development. 2011;138:5087–5097. doi: 10.1242/dev.067850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klenov MS, Sokolova OA, Yakushev EY, Stolyarenko AD, Mikhaleva EA, Lavrov SA, Gvozdev VA. Separation of stem cell maintenance and transposon silencing functions of Piwi protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:18760–18765. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106676108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Bras S, Van Doren M. Development of the male germline stem cell niche in Drosophila. Developmental biology. 2006;294:92–103. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leatherman JL, Dinardo S. Zfh-1 controls somatic stem cell self-renewal in the Drosophila testis and nonautonomously influences germline stem cell self-renewal. Cell stem cell. 2008;3:44–54. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee T, Luo L. Mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker for studies of gene function in neuronal morphogenesis. Neuron. 1999;22:451–461. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80701-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li MA, Alls JD, Avancini RM, Koo K, Godt D. The large Maf factor Traffic Jam controls gonad morphogenesis in Drosophila. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:994–1000. doi: 10.1038/ncb1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim JG, Fuller MT. Somatic cell lineage is required for differentiation and not maintenance of germline stem cells in Drosophila testes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:18477–18481. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215516109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H. Cell biology of stem cells: an enigma of asymmetry and self-renewal. J Cell Biol. 2008;180:257–260. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200712159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H, Spradling AC. A novel group of pumilio mutations affects the asymmetric division of germline stem cells in the Drosophila ovary. Development. 1997;124:2463–2476. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.12.2463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X, Wang S, Do T, Song X, Inaba M, Nishimoto Y, Liu LP, Gao Y, Mao Y, Li H, et al. Piwi is required in multiple cell types to control germline stem cell lineage development in the Drosophila ovary. PloS one. 2014;9:e90267. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison SJ, Spradling AC. Stem cells and niches: mechanisms that promote stem cell maintenance throughout life. Cell. 2008;132:598–611. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida KM, Saito K, Mori T, Kawamura Y, Nagami-Okada T, Inagaki S, Siomi H, Siomi MC. Gene silencing mechanisms mediated by Aubergine piRNA complexes in Drosophila male gonad. RNA. 2007;13:1911–1922. doi: 10.1261/rna.744307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng JC, Lin H. Beyond transposons: the epigenetic and somatic functions of the Piwi-piRNA mechanism. Current opinion in cell biology. 2013;25:190–194. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2013.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi H, Watanabe T, Ku HY, Liu N, Zhong M, Lin H. The Yb body, a major site for Piwi-associated RNA biogenesis and a gateway for Piwi expression and transport to the nucleus in somatic cells. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2011;286:3789–3797. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.193888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajasethupathy P, Antonov I, Sheridan R, Frey S, Sander C, Tuschl T, Kandel ER. A role for neuronal piRNAs in the epigenetic control of memory-related synaptic plasticity. Cell. 2012;149:693–707. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robine N, Lau NC, Balla S, Jin Z, Okamura K, Kuramochi-Miyagawa S, Blower MD, Lai EC. A broadly conserved pathway generates 3′UTR-directed primary piRNAs. Current biology: CB. 2009;19:2066–2076. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.11.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross RJ, Weiner MM, Lin H. PIWI proteins and PIWI-interacting RNAs in the soma. Nature. 2014;505:353–359. doi: 10.1038/nature12987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouget C, Papin C, Boureux A, Meunier AC, Franco B, Robine N, Lai EC, Pelisson A, Simonelig M. Maternal mRNA deadenylation and decay by the piRNA pathway in the early Drosophila embryo. Nature. 2010;467:1128–1132. doi: 10.1038/nature09465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito K, Inagaki S, Mituyama T, Kawamura Y, Ono Y, Sakota E, Kotani H, Asai K, Siomi H, Siomi MC. A regulatory circuit for piwi by the large Maf gene traffic jam in Drosophila. Nature. 2009;461:1296–1299. doi: 10.1038/nature08501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar A, Parikh N, Hearn SA, Fuller MT, Tazuke SI, Schulz C. Antagonistic roles of Rac and Rho in organizing the germ cell microenvironment. Current biology: CB. 2007;17:1253–1258. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sienski G, Donertas D, Brennecke J. Transcriptional silencing of transposons by Piwi and maelstrom and its impact on chromatin state and gene expression. Cell. 2012;151:964–980. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.10.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szakmary A, Cox DN, Wang Z, Lin H. Regulatory relationship among piwi, pumilio, and bag-of-marbles in Drosophila germline stem cell self-renewal and differentiation. Current biology: CB. 2005;15:171–178. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe T, Cheng EC, Zhong M, Lin H. Retrotransposons and pseudogenes regulate mRNAs and lncRNAs via the piRNA pathway in the germline. Genome research. 2014 doi: 10.1101/gr.180802.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe T, Cheng EC, Zhong M, Lin H. Retrotransposons and pseudogenes regulate mRNAs and lncRNAs via the piRNA pathway in the germline. Genome research. 2015;25:368–380. doi: 10.1101/gr.180802.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin H, Lin H. An epigenetic activation role of Piwi and a Piwi-associated piRNA in Drosophila melanogaster. Nature. 2007;450:304–308. doi: 10.1038/nature06263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.