Abstract

Few studies of the food environment have collected primary data, and even fewer have reported reliability of the tool used. This study focused on the development of an innovative electronic data collection tool used to document outdoor food and beverage (FB) advertising and establishments near 43 middle and high schools in the Outdoor MEDIA Study. Tool development used GIS based mapping, an electronic data collection form on handheld devices, and an easily adaptable interface to efficiently collect primary data within the food environment. For the reliability study, two teams of data collectors documented all FB advertising and establishments within one half-mile of six middle schools. Inter-rater reliability was calculated overall and by advertisement or establishment category using percent agreement. A total of 824 advertisements (n=233), establishment advertisements (n=499), and establishments (n=92) were documented (range=8–229 per school). Overall inter-rater reliability of the developed tool ranged from 69–89% for advertisements and establishments. Results suggest that the developed tool is highly reliable and effective for documenting the outdoor FB environment.

Keywords: food environment, outlets, objective data collection, reliability, outdoor food and beverage advertising

1. Introduction

While rates of childhood obesity appear to be slightly decreasing, rates are still significantly higher than they were a generation ago (Ogden et al., 2014). Because of this, research continues to focus on understanding why obesity among our youth persists and how it can be reduced. Of the many factors associated with obesity, a growing evidence base suggests we should consider the food environment (Powell et al., 2007, Larson et al., 2009).

Over the last decade, research on the food environment has grown substantially, particularly in the area of food outlet availability and food and beverage (FB) advertising. Many studies have examined the density of food outlets around schools and its relationship with obesity and diet quality (Austin et al., 2005, Kipke et al., 2007, Simon et al., 2008, Zenk and Powell, 2008, Davis and Carpenter, 2009, Larson and Story, 2009, Walton et al., 2009, Laska et al., 2010, Tester et al., 2010, Babey et al., 2011, Day and Pearce, 2011, Black and Day, 2012, Buck et al., 2013, Pereira et al., 2014, An and Sturm, 2012, Heroux et al., 2012, Laxer and Janssen, 2014, Tang et al., 2014). Schools are often a primary anchor for research related to youth as the environment around schools is likely to be experienced by youth on a daily basis. Therefore, by focusing on food outlets near schools, research may provide indication of food options that youth are exposed to frequently. For example, research examining fast-food restaurants and their distances to kindergartens, primary, and secondary schools in Chicago found that the mean distance from schools to a fast-food restaurant was only 0.52 kilometers, or a 5 minute walk. Furthermore, 78% of the schools examined had at least one fast-food restaurant within 800 meters, about a half-mile (Austin et al., 2005). Given that fast food is typically considered unhealthy, results suggests that youth may be increasingly exposed to unhealthy foods near their school. Similarly, a larger study of 20 cities found that a third of secondary schools have at least one fast-food restaurant or convenience store located within a half mile (Zenk and Powell, 2008). Given the findings from these studies, it is evident there is a need for additional research examining the food environment as youth have ready access to unhealthy foods and beverages.

While the presence of food outlets may have important implications for diet quality and other obesity-related outcomes, an often neglected aspect of food outlets is that they also serve as a form of product promotion (i.e., a McDonalds sign is an important form of branding). Previous research with alcohol advertising suggests increased exposure to alcohol advertising around schools is associated with adolescents’ intentions to use alcohol (Pasch et al., 2007), therefore, it is possible that outdoor food and beverage advertising may influence adolescents’ dietary choices. Specifically for youth, this may happen through repeated daily exposure or peripheral learning while traveling to and from school. While peripheral learning is assumed to have a lower impact on attitude and behavior change when compared to central learning, it is still an important factor to consider in the development and change of attitudes and behavior (Petty and Cacioppo, 1986), as well as food preferences and purchase requests (IOM, 2006). For example, in a review of the literature, among 22 studies that examined the effects of food marketing on food preference, 15 found a positive effect. Similarly, 15 of 17 studies suggested an effect of food marketing on purchase requests and 5 of 8 found an effect on beliefs (IOM, 2006). While results of this review suggest that food and beverage advertising does impact youth food choice behaviors and preferences, few studies within the review focused on outdoor FB advertising.

While numerous studies have used the Nutritional Environment Measure Survey (NEMS) tool to document food and beverage products placement, price, and promotion within stores (Glanz et al., 2007, Saelens et al., 2007, Cannuscio et al., 2013, Pereira et al., 2014), few studies to our knowledge have focused on outdoor FB advertising on outlets and within the community in the United States (Hillier et al., 2009, Yancey et al., 2009, Hosler and Dharssi, 2011, Powell et al., 2012, Rimkus et al., 2013), and only a handful more have focused on areas outside of the United States (Maher et al., 2005, Kelly et al., 2008, Walton et al., 2009, Adams et al., 2011). Findings from this work suggest that there are a large number of unhealthy outdoor advertisements that do not reflect current dietary guidelines, while evidence appears to be mixed if unhealthy advertisements cluster in specific areas or among particular populations. Additionally, little attention has been given to the larger outdoor advertising environment, which incorporates both outlet availability and outdoor advertising in one study.

While current work on FB advertising and outlets has added to the current literature base, a primary limitation of the field is the lack of consistent methodology of data collection and coding across studies. For example, only a few studies have collected primary data on either outlets or advertisements (Bader et al., 2010, Lake et al., 2010, Powell et al., 2011b), with the majority of the studies using secondary data from varying sources (Austin et al., 2005, Kipke et al., 2007, Simon et al., 2008, Zenk and Powell, 2008, Babey et al., 2011). This is problematic as research suggests that use of secondary sources does not appropriately represent the food environment (Powell et al., 2011a, Han et al., 2012). Furthermore, few have reported reliability of the associated data collection or coding tools (Kelly et al., 2008, Glanz, 2009, Hosler and Dharssi, 2011). Specifically, one study reported the inter-rater reliability for coding of advertisements collected around schools (77–96% agreement) (Kelly et al., 2008), one documented outlet type with very high reliability (98% agreement) (Cohen et al., 2007), and one reported the reliability of documentation and coding of ads that were located on outlets (94–99% agreement) (Hosler and Dharssi, 2011). This lack of primary data used within food environment research and limited reported reliability of tools has been discussed in multiple reviews on the food environment literature (Kelly et al., 2011, Caspi et al., 2012, Williams et al., 2014), and is concerning as it has implications for conclusions drawn across studies, which inform policy decisions. Therefore, there is a need for food environment research which uses primary data to measure the food environment and includes detailed information on the development and reliability of associated tools and protocols in order for researchers to be able to replicate findings across studies.

Given the current state of the field and that few measures are designed for primary data collection, the purpose of this study is to provide a detailed description of the development of a tool for documenting and describing primary data collected on outdoor FB advertising and FB outlets. Furthermore, inter-rater reliability of the tool for documenting food and beverage advertisements and outlets will be determined.

2. Methods

2.1. The Outdoor MEDIA Study

The Outdoor MEDIA (Measuring and Evaluating the Determinants and Influence of Advertising) Study was designed to document and describe the prevalence of outdoor FB advertising around Central Texas schools. The Outdoor MEDIA study documented and described FB advertising and establishments within a half-mile of 34 middle schools and 13 high schools. This included all middle and high schools in one district and an additional 14 schools from surrounding districts. To collect data, research staff created maps and driving directions outlining all streets within a half-mile radius of each school. A half-mile radius was chosen for two primary reasons. First, a review of the literature suggested that the mean size of buffers used was 904 meters (Austin et al., 2005, Maher et al., 2005, Kipke et al., 2007, Kelly et al., 2008, Zenk and Powell, 2008, Simon et al., 2008, Walton et al., 2009, Hillier et al., 2009, Davis and Carpenter, 2009, Adams et al., 2011, Day and Pearce, 2011). Given that 904 meters or 0.56 miles is not a practical metric, 800 meters was chosen as it approximates a half-mile. Secondly, recent research related to active transport suggests that youth are more likely to walk to school if they live within 700–800 meters of their school (Timperio et al., 2006, Oliver et al., 2014). This suggests that using 800 meters as a buffer is an acceptable distance as youth are known to walk similar distances to and from school.

Maps were created by drawing a 800 meter circular buffer around geolocated schools in ESRI ArcGIS (ESRI, 2010). School data was obtained from the Texas Education Agency (Texas Education Agency, 2010). During field data collection for each school, teams were provided a grid map of the data collection area in addition to detailed driving directions that would ensure they systematically drove down every street on the map. While in the field, all teams documented the location of each instance of FB advertising or establishment through photographs and global positioning system (GPS) coordinates. Two Garmin eTrex (Garmin, 2010) handheld devices were used to determine advertisement and outlet GPS coordinates. All data collection was completed using an electronic data collection tool created for the project.

2.2. Data Collection Protocol

The data collection protocol was based on a protocol used for Project Northland Chicago (PNC) (Pasch et al., 2007, Pasch et al., 2009), a similar project documenting alcohol advertising around schools. Components of the data collection protocol included the research objective, instructions on what to look for while in the field, key safety concerns, necessary supporting materials, descriptions and directions of supporting materials, a team overview and team member responsibilities, and instructions for use of the data collection tool and handheld Global Positioning System (GPS) device. The last section included a detailed description of how to systematically collect data on food and beverage advertisements and establishments while in the field. Please contact the corresponding author to request the full protocol.

2.3. The Outdoor MEDIA Direct Observation Tool (DOT)

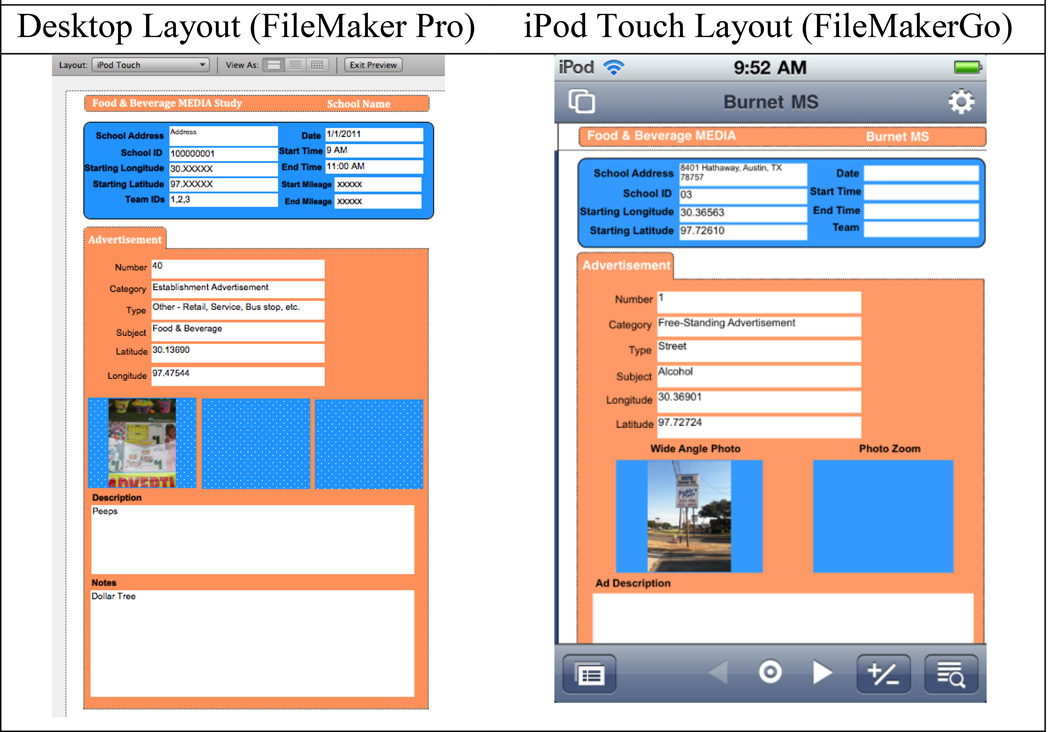

While planning the methods for performing data collection, an electronic data collection tool was chosen as this would minimize manual data entry and, therefore, increase efficiency of data collection while decreasing the chance of human error during data entry. To do this, an iPod Touch® was selected as an appropriate means of data collection. It was selected because it had access to FileMakerGo, an application that allowed for the creation of a customized database. FileMakerGo is also relatively inexpensive, easy to use, and has the ability to accommodate photographs (FileMaker, 2011). Furthermore, FileMakerGo allows for separate databases to be created for each school to maintain data organization, and has the ability to insert photographs taken by the iPod Touch® directly into the file. This was critically important for the project as it removed the problem of manually linking a digital camera photo to the data collection record. Finally, the use of this mobile device to document food and beverage advertising in public areas would limit disruption and would not attract attention when entering data or taking photos.

To create the mobile databases, both FileMaker Pro and FileMakerGo were used. FileMaker Pro allowed for the creation and merging of the databases (FileMaker, 2011), while FileMakerGo served as the mobile, field version of the database. Separate files for each school were created to ensure that only the data for each school would be modified at one time. This also protects all data from being lost if something were to happen while in the field.

Layouts were designed by first creating labels for each measure (See Table 1 for list and definition of each measure) and incorporating the labels into a user friendly layout. At the top of the layout, a header was used as it allowed for key fields to be automatically populated such as school address, school ID, longitude, latitude, date, starting time, ending time, and data collector ID for subsequent added records. Within the body of the layout, all other variables (category, type, subject, latitude, longitude, description, notes) were inserted with drop down boxes or free response boxes for response options. Placing these variables in the body of the layout ensured that the data collector would enter new information for each advertisement, establishment advertisement, and establishment. See figure 1 for visual representation of layout.

Table 1.

Variables included on the Outdoor MEDIA DOT and associated definitions.

| Variable | Definition | |

|---|---|---|

| Category | ||

| Advertisement | Any sign promoting food or beverages that is free-standing or not attached to an establishment. | |

| Establishment Advertisement | Any sign promoting food or beverages that is directly attached to or located on an establishment. | |

| Establishment | Any outlet that sells food or beverages to the public. | |

| Type | ||

| Billboard | Any framed, permanent structure with a changeable sign. | |

| Street Side Sign | Any free-standing sign intended to be seen at the street. | |

| Gas Station/Convenience Store | Any establishment that primarily sells snack foods and drinks. | |

| Directory | A multi-sign board typically found at the entrance of shopping center. | |

| Food Trailer | Any food outlet that sells food out of a vehicle or trailer. | |

| Grocery Store | A store that primarily sells food and beverages. | |

| Liquor Store | A store that primarily sells alcohol including beer, wine, and liquor. | |

| Fast Food Restaurant | Any food outlet that is ordered from a counter. | |

| Quick/Full Service Restaurant | Any food outlet other than fast food. | |

| Other | Any other sign or establishment advertising food or beverage. | |

| Subject | ||

| Food and Beverage | Any sign or outlet that primarily promotes or sells food and beverage. | |

| Tobacco | Any sign or outlet that primarily promotes or sells tobacco. | |

| Alcohol | Any sign or outlet that primarily promotes or sells alcohol. | |

Figure 1.

Outdoor MEDIA DOT Layout Desktop Layout

Categories, types, and subject of advertisement, establishment advertisement, or establishment were determined based on a review of the literature or were created for this study. Categories included advertisements, establishment advertisements, and establishments. An advertisement was defined as any signage promoting a food or beverage that was free standing or not directly placed on the establishment building. Examples of advertisements included signs on gas pumps, sidewalks, A-frames, banners, and billboards. An establishment advertisement was defined as any signage promoting a food or beverage that was directly placed on the windows or walls of the establishment. Examples of establishment advertisements included posters on windows, walls, or doors. The final category was establishment. Teams were instructed to take an overall photo of every outlet that sold food or beverage products. Examples of outlets documented included gas stations, convenience stores, grocery stores, restaurants, food trailers, and farm stands. Additional establishments that are not considering typical food and beverage establishments such as drug stores and dollar stores were also documented and coded as “other.” A similar categorization scheme has been used by previous research examining alcohol outlets and advertising near schools (Pasch et al., 2007, Pasch et al., 2009).

A type variable was also coded while in the field, which indicated where the advertisement was located or what type of establishment was documented. Types included billboard, street side sign, convenience store/gas station, directory, food trailer, neighborhood grocery, supermarket, liquor store, fast food restaurant, quick service/full service restaurant, or other – bus stop, service, etc. A billboard was defined as any framed, permanent structure with a changeable sign, either free standing or attached to a building. Street side signs were defined as advertisements or signs that are located directly on the street for passing cars to see. An example of this is the McDonald’s logo “M” sign that is located directly on the street for cars on both the street below as well as on surrounding streets to see. A convenience store/gas station was defined as any outlet that primarily sells pre-packaged goods and often sells gasoline. Directory was defined as the large framed sign located at the entrance of a shopping center that often has multiple names or logos of businesses located within that area. Food trailers were defined as food outlets that operate out of a small, mobile vending truck that often have a limited menu. Neighborhood grocery stores were defined as grocery stores that were small and intended to primarily serve the surrounding neighborhood. Supermarkets were defined as grocery stores that were much larger and intended to serve a wider range of customers. Liquor stores were defined as outlets that primarily sell liquor, beer, and wine. Fast food restaurants were defined as restaurants at which you order and receive food at the counter. Quick and full service restaurants were defined as food outlets that employ a wait staff to bring food to the table. If an advertisement, establishment advertisement, or establishment did not fall into one of these categories, the “other” category was used (Table 1).

A subject variable was used to define the three different types of products assessed: Food and Beverage, Alcohol, and Tobacco. Food and Beverage was used for advertisement which marketed an item that could be consumed (other than alcohol) or for an establishment which primarily sold foods and beverages. For the present study, all advertisements other than Food and Beverage were removed as the focus of this paper is on the reliability of the tool to document FB advertising and establishments. This resulted in inclusion of 84.5% of all documented advertisements and outlets. Alcohol advertisements and outlets represented 6.9% and tobacco advertisements and outlets represented 8.6% of documented advertisements and outlets. See Table 1 for response options and associated definitions included in layout. See Figure 1 for visual presentation of Outdoor MEDIA DOT layout.

In total, two files were created for each data collection school. A primary data collection file and a backup data collection file. This was done to ensure there was at least one working file for primary data collection while in the field. All files were then synced between the computer and the iPod Touch® FileMakerGo application.

During data collection, data collectors proceeded out of the school grounds to follow the turn-by-turn driving directions down every street within the half-mile buffer. Teams then proceeded down each street until a FB advertisement or establishment was seen. The team would then pull the vehicle over, take a photo and GPS measurements for the advertisement or establishment, and complete the data collection record. This continued until each street in the 800 meter radius around the school was assessed. The radius was determined by use of a previously created grid map, which included the buffer line, as well as driving directions down all streets within the buffer. If it was not clear where the buffer ended, data collection teams were instructed to continue to the next block or appropriate stopping point to ensure that the entire buffer area was assessed.

2.4. Inter-Rater Reliability of Outdoor MEDIA DOT

To examine the reliability of the Outdoor MEDIA DOT, 7 schools were randomly selected, representing 12% of the total Outdoor MEDIA sample and 20% of the middle school sample while also including both urban and suburban schools. Two separate teams each completed a full data collection within 24 hours of each other for all of the seven schools. It was imperative to perform reliability data collection quickly to ensure that advertisements and establishment advertisements would not have changed before the second team performed their data collection.

After data collection and cleaning, files from each team were manually compared to their corresponding school by a graduate student to match appropriate records. To do this, the graduate student compared fields including the photograph, description, and notes of each record from team 1 and team 2. When a matching record was found, a unique number was given to each of the matching records. If a record was unmatched in either file, it was also given a unique number indicating that there was not a match. Assigning unique numbers to records ensured that when comparing records between teams, only one record from each would be used in analysis.

A reliability analysis was performed for each record in its entirety, which included embedded variables such as category (advertisement, establishment advertisement, and establishment), type (billboard, gas station/convenience store, directory, food trailer, grocery store, liquor store, fast food restaurant, other restaurant, street side sign, and other), and subject (food and beverage, alcohol, and tobacco). Definitions of each can be found in Table 1 and in the methods section above.

2.4.1. Statistical Analysis

Percent agreements were determined to be the most appropriate calculations of inter-rater reliability for these data. Percent agreements provide an overall indication of reliability between the different teams across an entire record. Furthermore, percent agreements are easy to understand and easily interpretable (McHugh, 2012). Due to the nature of the data, Cohen’s Kappa, a commonly used measure of reliability, was not chosen as the level of chance agreement varied within each record and each school, which made the use of a Kappa statistic inappropriate.

In order to provide adequate reliability detail, reliability analyses were conducted for the two levels of data that were collected. Level 1 data documented the presence of an advertisement, establishment advertisement, or establishment. As such, Level 1 percent agreement indicated that an advertisement, establishment advertisement, or establishment was documented by both teams. This was done by comparing rates of matched and unmatched records across both data collection teams. Level 2 data documented the details of each advertisement or establishment. Level 2 percent agreement was calculated only if both teams documented the same advertisement, establishment, or establishment advertisement. Each of these variables was incorporated into the percent agreement score, as each record was considered in its entirety. Level 2 percent agreement measures indicated the degree to which the details of the record which included category (advertisement, establishment, or advertisement establishment), type (fast-food, grocery store, convenience store, etc.), and subject (food and beverage, alcohol, or tobacco) were coded similarly across teams. Percent agreements of 100% indicated a perfect match between teams for either documenting (level 1) or coding (level 2) the advertisement or establishment similarly.

Percent agreements were calculated for the overall tool reliability, by each category (advertisement, establishment advertisement, and establishment), and by school. A custom formula was used in FileMaker to determine percent agreement between matched records. Microsoft Excel was used to calculate mean percent agreement and standard deviation of each category reviewed for reliability.

During reliability analyses, one school was dropped due to problematic construction and road closures within the neighborhood that did not allow each team to cover the 800 meter buffer area around the school similarly. Furthermore, records that were determined not to be food or beverage advertising were also dropped. This does not include food and beverage records that were documented differently across teams. Finally, records that provided an obvious indication that advertisements changed overnight were removed from analysis. For example, a convenience store storefront documented by each team within 24 hours of each other had an entirely new set of window advertisements. Because this tool was not designed to capture the rate of changing advertisements, we felt it was not appropriate to include this in reliability analyses (See Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Example of Changing Advertisements

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Characteristics

A total of 824 advertisements, establishment advertisements, and establishments were documented by both teams (range=8–229 per school). Of those, 233 were advertisements, 499 were establishment advertisements, and 92 were establishments. Number of advertisements per school was highly dependent on the location of the school such that urban schools had more total advertisements than suburban schools (e.g., 229 vs. 8 advertisements). The schools used for the reliability analyses had a mean of 906 students per school and represented both urban and suburban schools (n=6 schools). On average, students attending these six schools were 53% male, 18% White, 61% Hispanic, 15% Black, and 6% other, and 73% qualified for free or reduced lunch. When compared to the larger Outdoor MEDIA study, the reliability sample had more percent Hispanic students (61% vs. 52%), fewer White students (18% vs. 28%), and more students who qualified for free or reduced lunch (73% vs. 60%).

3.2. Level 1: Were advertisements, establishment advertisements, and establishments documented similarly across teams?

Level 1 reliability was high overall (0.71, SE=0.45), which indicated that both teams documented 71% of all advertisements or establishments similarly (Table 2). For each category (advertisement, establishment advertisement, or establishment), level 1 reliability ranged from 0.69 to 0.87, meaning that between 69% and 87% of all types of advertisements and outlets were documented similarly across teams. For advertisements, level 1 percent agreement was 0.70 (SE=0.46), suggesting that 70% of advertisements were documented by both teams. For establishment advertisements, level 1 percent agreement was 0.69 (SE=0.46), which indicated that 69% of establishment advertisements were documented by both teams. Establishments had the highest level 1 reliability with 0.87 (SE=0.33), suggesting that 87% of establishment were documented similarly across teams (Table 2).

Table 2.

Reliability of Outdoor MEDIA DOT Overall, by Category, and by School.

| n | Level 1 (SE) | Level 2 (SE) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 824 | 0.71 (0.45) | 0.84 (0.22) | |

| Mean | 137 | |||

| Median | 156 | |||

| By Category | ||||

| Advertisements | 233 | 0.70 (0.46) | 0.73 (0.39) | |

| Establishment Advertisements | 499 | 0.69 (0.46) | 0.89 (0.19) | |

| Establishments | 92 | 0.87 (0.34) | 0.84 (0.23) | |

| By School | ||||

| School 1 | 229 | 0.65 (0.48) | 0.85 (0.22) | |

| School 2 | 232 | 0.63 (0.48) | 0.81 (0.24) | |

| School 3 | 221 | 0.87 (0.34) | 0.80 (0.22) | |

| School 4 | 91 | 0.69 (0.46) | 0.91 (0.16) | |

| School 5 | 43 | 0.74 (0.44) | 0.92 (0.19) | |

| School 6 | 8 | 0.88 (0.35) | 0.90 (0.16) | |

In regard to level 1 reliability by school, percent agreements ranged from 0.63 to 0.88 (SE=0.34–0.48). Refer to Table 2 for detailed school-level reliability results.

3.3. Level 2: If documented by both teams, were advertisements, establishment advertisements, and establishments coded similarly by both teams?

Of the total 824 advertisements and establishments, 164 advertisements, 344 establishment advertisements, and 80 establishments (total n=588) were included in the level 2 reliability analysis as they were documented by both teams. Overall, level 2 reliability was high (0.84, SE=0.22), suggesting that of the advertisements, establishment advertisements, and establishments which were documented by both teams, 84% were coded similarly for category, type, and subject (Table 2).

For each category (advertisement, establishment advertisement, or establishment), level 2 reliability ranged from 0.73 to 0.84, meaning that between 73% and 84% of advertisements, establishment advertisements, and establishments were coded similarly between the two data collection teams. For advertisements, level 2 was 0.73 (SE=0.39), suggesting that 73% of advertisements were coded similarly. Level 2 reliability for establishment advertisements was 0.89 (SE=0.19), the highest reliability by category. This indicated that when an establishment advertisement was documented by both teams, teams coded that particular establishment advertisement similarly 89% of the time. While still high, level 2 reliability of establishments was slightly lower at 0.84 (SE=0.23), indicating that 84% of similarly documented establishments were coded similarly (Table 2). Level 2 reliability by school ranged from 0.80 to 0.92 (SE=0.16–0.24). Refer to Table 2 for detailed school-level reliability results. For information on the usability of the protocol and DOT, please refer to Supplement 1.

4. Discussion

Findings from this study suggest that FB advertisements and outlets can be documented and coded with high reliability by trained data collectors, even though FB advertising is diverse and changes frequently. In comparison with other similar studies, this tool documents outdoor food and beverage advertising with similar reliability (0.69–0.87 vs. 77–80% (Kelly et al., 2007), 25% (Cohen et al., 2007)), yet does so with a tool that is easily adaptable for future research and minimizes data entry thru its innovative, electronic platform. Another study, which reported a higher coding reliability for advertisements (95–99% (Hosler et al., 2001)), only documented window advertisements of specific content, and did not include a census of the food or beverage advertisement found within the area. Given this, our tool maintains a high reliability while being highly adaptable, easy to use, and documenting all food and beverage advertisements,

This study adds to the existing food environment literature as it leverages objective, primary data on FB advertisements and establishments. This is important as previous work has suggested that use of secondary data does not accurately represent the food environment (Powell et al., 2011a, Han et al., 2012). Secondly, it is among the first studies to provide a detailed description of tool development and examine the reliability of a tool used to document the outdoor FB environment, including all food and beverage advertising. Specifically, other studies that have reported reliability of data collection tools, often do so without providing a detailed description of tool creation (Kelly et al., 2007, Cohen et al., 2011).

While reliability was reasonably high given the nature of food and beverage advertising, there were differences in both documentation and coding of advertisements and establishments; however, no team was consistently different than the other. This is likely due to the breadth of FB advertising and subjective nature coding advertisements. For example, before this study began, the extent and sheer number of advertisements data collectors would document was underestimated. This may have led to teams rushing through data collection areas or overlooking advertisements, simply because in the array of other advertising they were missed. In regard to coding advertising, other work found similar differences between coders and suggests that additional training and detailed definitions of key codes would increase reliability (Jones et al., 2010). Reliability among coders may also be improved through group reliability meetings or through the use of frequent reliability checks. Therefore, future work should consider frequent training and reliability checks with discussion of any problematic codes to obtain the highest reliability possible. Lastly, in regard to reliability, the present study used percent agreement which does not take into account agreement by chance. However, given that the possible coding choices varied by each record/advertisement, an overarching measure of reliability such as Cohen’s Kappa would likely produce lower reliability values.

Of the fields included on each record, we found the photographs to be critically important. These photos served as a reminder of the advertisement while doing further coding. For example, photos from the overall Outdoor MEDIA project have been coded for descriptive, informational, nutritional, and thematic content. This would not have been possible if photographs were not taken. Based on our experiences, while photographs of advertisements and establishments are the least likely to be well received by store owners and clerks, they are the most valuable piece of information collected in regard to understanding the food environment.

Given the diversity of the FB environment, we believe that this highly customizable, user-friendly tool can be used in a variety of applications and settings. For example, this tool and protocol can easily be adapted for data collection on a variety of types of advertising including in-store, alcohol, and tobacco. Furthermore, the Outdoor MEDIA DOT was able to document advertisements and outlets with high reliability within both urban and suburban settings as evidence by the difference in school 1 (urban) and 6 (suburban). In addition to advertising, we believe the utility of the tool has many other applications. For example, adaptations of this tool may be useful for community regional planners when assessing public space and walkability as it would allow for key descriptive codes and photos to be taken simultaneously. Researchers focused on the physical activity environment would also be able to benefit from this tool as it would allow for physical documentation of recreation and physical activity resources in an area. Even beyond research, a tool such as the Outdoor MEDIA DOT would allow practitioners a simple and economical way to document and describe neighborhoods and communities.

While there are many aspects of the Outdoor MEDIA protocol and DOT that worked effectively, there are a few key changes we believe would benefit the tool. First, inclusion of additional photo boxes on each record, beyond the three photo boxes included on the original tool, would provide opportunity for clearer or more detailed photos to be taken of a particular advertisement or outlet. In regard to photographs, additional emphasis should also be placed in the protocol and associated training on the need for clear photographs. Without clear photographs detailed coding is difficult as the image is often blurry or difficult to read. However, even with the photos in the current study, we were able to do extensive coding in the lab after field data collection was complete. While carrying the database on a mobile device could result in the loss of data due to equipment/software malfunction or loss of the device, this limitation was minimized for this project as the sample was relatively small and a single school could be redone if necessary. Additionally, this method did not require 3G or wifi data access, making it a cost effective way to collect data. As previously mentioned, comprehensive driving directions were sometimes difficult to follow. To alleviate this problem, data collectors should be asked to create driving directions, which minimized left turns and crossing busy intersections multiple times. Finally, we believe that additional training on how to handle and deal with store owners and managers would benefit the data collection team.

In conclusion, we believe that the Outdoor MEDIA protocol and DOT are highly reliable and appropriate tools to use while documenting the outdoor food and beverage environment. The protocol and DOT were successful in documenting and coding advertisements, establishment advertisements, and establishments, easy to use by data collectors, and provided a format to decrease data entry time while linking photographs with key descriptive information. Future research should consider application of this tool and suggested improvements to determine if reliability across settings and topic areas can be maintained. For example, if used to document tobacco advertising, are photographs received differently by store owners or clerks (particularly if taken within the store), do photographs serve a similar critical importance, or are tobacco advertisements documented consistently between teams? All of these questions are important to consider within many fields of health research as all will help researchers better understand the overall landscape of our environment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research was funded through a grant to Dr. Keryn E. Pasch from the National Cancer Institute, grant # R03CA158962. The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adams J, Ganiti E, White M. Socio-economic differences in outdoor food advertising in a city in Northern England. Public Health Nutr. 2011;14(6):945–950. doi: 10.1017/S1368980010003332. DOI: S1368980010003332 [pii]10.1017/S1368980010003332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An R, Sturm R. School and residential neighborhood food environment and diet among California youth. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(2):129–135. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin SB, Melly SJ, Sanchez BN, Patel A, Buka S, Gortmaker SL. Clustering of fast-food restaurants around schools: a novel application of spatial statistics to the study of food environments. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(9):1575–1581. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.056341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babey SH, Wolstein J, Diamant AL. Food environments near home and school related to consumption of soda and fast food. Policy Brief UCLA Cent Health Policy Res, (PB2011-6) 2011:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bader MD, Ailshire JA, Morenoff JD, House JS. Measurement of the local food environment: a comparison of existing data sources. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171(5):609–617. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp419. DOI: kwp419 [pii]10.1093/aje/kwp419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black JL, Day M. Availability of limited service food outlets surrounding schools in British Columbia. Can J Public Health. 2012;103(4):e255–e259. doi: 10.1007/BF03404230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck C, Bornhorst C, Pohlabeln H, Huybrechts I, Pala V, Reisch L, Pigeot I. Clustering of unhealthy food around German schools and its influence on dietary behavior in school children: a pilot study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2013;10:65. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-10-65. DOI: 1479-5868-10-65 [pii]10.1186/1479-5868-10-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannuscio CC, Tappe K, Hillier A, Buttenheim A, Karpyn A, Glanz K. Urban food environments and residents' shopping behaviors. Am J Prev Med. 2013;45(5):606–614. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi CE, Sorensen G, Subramanian SV, Kawachi I. The local food environment and diet: a systematic review. Health Place. 2012;18(5):1172–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.05.006. DOI: S1353-8292(12)00103-7 [pii]10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen DA, Schoeff D, Farley TA, Bluthenthal R, Scribner R, Overton A. Reliability of a store observation tool in measuring availability of alcohol and selected foods. J Urban Health. 2007;84(6):807–813. doi: 10.1007/s11524-007-9219-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis B, Carpenter C. Proximity of fast-food restaurants to schools and adolescent obesity. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(3):505–510. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.137638. DOI: AJPH.2008.137638 [pii]10.2105/AJPH.2008.137638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day PL, Pearce J. Obesity-promoting food environments and the spatial clustering of food outlets around schools. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40(2):113–121. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.10.018. DOI: S0749-3797(10)00611-2 [pii]10.1016/j.amepre.2010.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esri. ArcGIS ArcMap 10. Redlands, CA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Filemaker. FileMaker Pro 12. Apple Inc; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Garmin. Garmin eTrex Portable GPS Naviagtor. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- Glanz K. Measuring food environments: a historical perspective. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(4 Suppl):S93–S98. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.010. DOI: S0749-3797(09)00018-X [pii]10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glanz K, Sallis JF, Saelens BE, Frank LD. Nutrition Environment Measures Survey in stores (NEMS-S): development and evaluation. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(4):282–289. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han E, Powell LM, Zenk SN, Rimkus L, Ohri-Vachaspati P, Chaloupka FJ. Classification bias in commercial business lists for retail food stores in the U.S. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;9:46. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-9-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heroux M, Iannotti RJ, Currie D, Pickett W, Janssen I. The food retail environment in school neighborhoods and its relation to lunchtime eating behaviors in youth from three countries. Health Place. 2012;18(6):1240–1247. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillier A, Cole BL, Smith TE, Yancey AK, Williams JD, Grier SA, Mccarthy WJ. Clustering of unhealthy outdoor advertisements around child-serving institutions: A comparison of three cities. Health Place. 2009;15:935–945. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosler AS, Dharssi A. Reliability of a survey tool for measuring consumer nutrition environment in urban food stores. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2011;17(5):E1–E8. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3182053d00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine [IOM] National Academy of Sciences, Committee on Food Marketing and the Diets of Children and Youth. In: McGinnins JM, Gootman J, Kraak VI, editors. Food marketing to children and youth: Threat or opportunity? Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine of the National Academies; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jones NR, Jones A, Van Sluijs EM, Panter J, Harrison F, Griffin SJ. School environments and physical activity: The development and testing of an audit tool. Health Place. 2010;16(5):776–783. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly B, Cretikos M, Rogers K, King L. The commercial food landscape: outdoor food advertising around primary schools in Australia. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2008;32(6):522–528. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2008.00303.x. DOI: AZPH303 [pii]10.1111/j.1753-6405.2008.00303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly B, Flood VM, Yeatman H. Measuring local food environments: an overview of available methods and measures. Health Place. 2011;17(6):1284–1293. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.08.014. DOI: S1353-8292(11)00154-7 [pii]10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kipke MD, Iverson E, Moore D, Booker C, Ruelas V, Peters AL, Kaufman F. Food and park environments: neighborhood-level risks for childhood obesity in east Los Angeles. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40(4):325–333. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.10.021. DOI: S1054-139X(06)00427-7 [pii]10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lake AA, Burgoine T, Greenhalgh F, Stamp E, Tyrrell R. The foodscape: classification and field validation of secondary data sources. Health Place. 2010;16(4):666–673. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.02.004. DOI: S1353-8292(10)00014-6 [pii]10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson N, Story M. A review of environmental influences on food choices. Ann Behav Med. 2009;38(Suppl 1):S56–S73. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson NI, Story MT, Nelson MC. Neighborhood environments: disparities in access to healthy foods in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(1):74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.09.025. DOI: S0749-3797(08)00838-6 [pii]10.1016/j.amepre.2008.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laska MN, Hearst MO, Forsyth A, Pasch KE, Lytle L. Neighbourhood food environments: are they associated with adolescent dietary intake, food purchases and weight status? Public Health Nutr. 2010;13(11):1757–1763. doi: 10.1017/S1368980010001564. DOI: S1368980010001564 [pii]10.1017/S1368980010001564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laxer RE, Janssen I. The proportion of excessive fast-food consumption attributable to the neighbourhood food environment among youth living within 1 km of their school. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2014;39(4):480–486. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2013-0208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher A, Wilson N, Signal L. Advertising and availability of 'obesogenic' foods around New Zealand secondary schools: a pilot study. N Z Med J. 2005;118(1218):U1556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mchugh ML. Lessons in biostatistics: Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochemia Medica. 2012;22(3):276–282. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011–2012. JAMA. 2014;311(8):806–814. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver M, Badland H, Mavoa S, Witten K, Kearns R, Ellaway A, Hinckson E, Mackay L, Schluter PJ. Environmental and socio-demographic associates of children's active transport to school: a cross-sectional investigation from the URBAN Study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2014;11:70. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-11-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasch KE, Komro KA, Perry CL, Hearst MO, Farbakhsh K. Outdoor alcohol advertising near schools: what does it advertise and how is it related to intentions and use of alcohol among young adolescents? J Stud Alc Drug. 2007;68(4):587–596. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasch KE, Komro KA, Perry CL, Hearst MO, Farbakhsh K. Does outdoor alcohol advertising around elementary schools vary by the ethnicity of students in the school? Ethnic Health. 2009;14(2):225–236. doi: 10.1080/13557850802307809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira RF, Sidebottom AC, Boucher JL, Lindberg R, Werner R. Assessing the food environment of a rural community: baseline findings from the heart of New Ulm project, Minnesota, 2010–2011. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:E36. doi: 10.5888/pcd11.130291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petty RE, Cacioppo JT. The Elaboration Likeligood Model of Persuasion. Advance Exp Soc Psy. 1986;19:124–192. [Google Scholar]

- Powell LM, Auld MC, Chaloupka FJ, O'malley PM, Johnston LD. Associations between access to food stores and adolescent body mass index. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(4 Suppl):S301–S307. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.07.007. DOI: S0749-3797(07)00433-3 [pii]10.1016/j.amepre.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell LM, Han E, Zenk SN, Khan T, Quinn CM, Gibbs KP, Pugach O, Barker DC, Resnick EA, Myllyluoma J, Chaloupka FJ. Field validation of secondary commercial data sources on the retail food outlet environment in the U.S. Health Place. 2011a;17(5):1122–1131. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell LM, Rimkus LM, Isgor Z, Barker D, Chaloupka FJ. Exterior Marketing Practices of Fast-Food Restaurants. [Accessed March];2012 doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.08.011. Available: http://www.bridgingthegapresearch.org/_asset/2jc2wr/btg_fast_food_pricing_032012.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell LM, Schermbeck RM, Szczypka G, Chaloupka FJ, Braunschweig CL. Trends in the nutritional content of television food advertisements seen by children in the United States: analyses by age, food categories, and companies. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011b;165(12):1078–1086. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.131. DOI: archpediatrics.2011.131 [pii]10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimkus L, Powell LM, Zenk SN, Han E, Ohri-Vachaspati P, Pugach O, Barker DC, Resnick EA, Quinn CM, Myllyluoma J, Chaloupka FJ. Development and reliability testing of a food store observation form. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2013;45(6):540–548. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saelens BE, Glanz K, Sallis JF, Frank LD. Nutrition Environment Measures Study in restaurants (NEMS-R): development and evaluation. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(4):273–281. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon PA, Kwan D, Angelescu A, Shih M, Fielding JE. Proximity of fast food restaurants to schools: Do neighborhood income and type of school matter? Prev Med. 2008;47:284–288. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang X, Ohri-Vachaspati P, Abbott JK, Aggarwal R, Tulloch DL, Lloyd K, Yedidia MJ. Associations between food environment around schools and professionally measured weight status for middle and high school students. Child Obes. 2014;10(6):511–517. doi: 10.1089/chi.2014.0065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tester JM, Yen IH, Laraia B. Mobile food vending and the after-school food environment. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(1):70–73. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.09.030. DOI: S0749-3797(09)00630-8 [pii]10.1016/j.amepre.2009.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Texas Education Agency. School District Locator - Data Download [Online] [Accessed 2011];2010 http://ritter.tea.state.tx.us/SDL/sdldownload.html. [Google Scholar]

- Timperio A, Ball K, Salmon J, Roberts R, Giles-Corti B, Simmons D, Baur LA, Crawford D. Personal, family, social, and environmental correlates of active commuting to school. Am J Prev Med. 2006;30(1):45–51. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.08.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton M, Pearce J, Day P. Examining the interaction between food outlets and outdoor food advertisements with primary school food environments. Health Place. 2009;15(3):811–818. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.02.003. DOI: S1353-8292(09)00012-4 [pii]10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J, Scarborough A, Matthews A, Cowburn G, Foster C, Roberts N, Rayner M. A systematic review of the influence of the retail food environment around schools on obesity-related outcomes. Obes Rev. 2014;15(5):359–374. doi: 10.1111/obr.12142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yancey AK, Cole BL, Brown R, Williams JD, Hillier A, Kline RS, Ashe M, Grier SA, Backman D, Mccarthy WJ. A cross-sectional prevalence study of ethnically targeted and general audience outdoor obesity-related advertising. Milbank Q. 2009;87(1):155–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00551.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zenk SN, Powell LM. US secondary schools and food outlets. Health Place. 2008;14(2):336–346. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2007.08.003. DOI: S1353-8292(07)00066-4 [pii]10.1016/j.healthplace.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.