Abstract

Changes in gene expression form a crucial part of the plant response to infection. In the last decade, whole-leaf expression profiling has played a valuable role in identifying genes and processes that contribute to the interactions between the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana and a diverse range of pathogens. However, with some pathogens such as downy mildew caused by the biotrophic oomycete pathogen Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis (Hpa), whole-leaf profiling may fail to capture the complete Arabidopsis response encompassing responses of non-infected as well as infected cells within the leaf. Highly localized expression changes that occur in infected cells may be diluted by the comparative abundance of non-infected cells. Furthermore, local and systemic Hpa responses of a differing nature may become conflated. To address this we applied the technique of Fluorescence Activated Cell Sorting (FACS), typically used for analyzing plant abiotic responses, to the study of plant-pathogen interactions. We isolated haustoriated (Hpa-proximal) and non-haustoriated (Hpa-distal) cells from infected seedling samples using FACS, and measured global gene expression. When compared with an uninfected control, 278 transcripts were identified as significantly differentially expressed, the vast majority of which were differentially expressed specifically in Hpa-proximal cells. By comparing our data to previous, whole organ studies, we discovered many highly locally regulated genes that can be implicated as novel in the Hpa response, and that were uncovered for the first time using our sensitive FACS technique.

Keywords: plant-pathogen interactions, oomycete pathogens, biotrophic infection, cell type-specific transcriptomics, Fluorescence Activated Cell Sorting

Introduction

Unlike mammals, plants do not develop specialized immune cells. Instead, they rely on Pattern-Recognition Receptors (PRRs), which detect conserved molecules or motifs associated with foreign micro-organisms (Zipfel, 2014), and cytoplasmic NOD-Like Receptors (NLRs), which detect more specific pathogen-derived effectors that are delivered into the plant cell (Jones and Dangl, 2006). Perception of a pathogen by these receptors triggers a cascade of cellular signaling events, which culminate at the cell nucleus where transcriptional reprogramming occurs (Tsuda and Somssich, 2015).

Transcriptional reprogramming is a crucial part of the immune response, and this makes it a potential target for interference from pathogens. Manipulation of host gene expression may be particularly important for biotrophic pathogens, which must keep their host cells alive while effectively suppressing the immune system and extracting nutrients. A number of pathogenic effectors from Pseudomonas syringae and Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis (Hpa) have been shown to localize to the host cell nucleus, or to physically interact with transcriptional machinery (Mukhtar et al., 2011; Caillaud et al., 2012, 2013). Several endogenous Arabidopsis genes have been shown to be involved in disease susceptibility (Lapin and Van den Ackerveken, 2013; Zeilmaker et al., 2015) and expression of these may be induced by a pathogen to aid infection. Thus, being able to understand the transcriptional response to infection is not only important to understand the mechanisms by which plants resist pathogens, but also those by which pathogens suppress the plant immune system and exploit the endogenous molecular machinery of the plant for their own gain.

The pathosystem of Arabidopsis and its downy mildew pathogen Hpa has been an invaluable model in plant pathology over the past two decades for a number of reasons (Coates and Beynon, 2010). Firstly, Hpa is an oomycete, making it phylogenetically distinct from the many bacterial and fungal pathogens that have received extensive study, but more closely related to the agriculturally important potato blight, Phytophthora infestans. Additionally, the remarkable number of Hpa isolates, along with the number of differentially susceptible and resistant Arabidopsis ecotypes, available for study has made the pathosystem a useful tool for studying gene-for-gene resistance (Holub, 2007). Following this, advancements in genomics have shifted the focus toward large-scale identification of Hpa's RxLR effectors and unraveling their effects on the host (Baxter et al., 2010; Fabro et al., 2011; Mukhtar et al., 2011; Caillaud et al., 2013).

Finally, the pathosystem is perhaps the clearest example of obligate biotrophy in Arabidopsis. Upon landing on a leaf surface, an asexual Hpa conidiospore germinates and forms an appressorium to penetrate the leaf surface. As early as 1 day post-infection, Hpa grows intercellularly as hyphae, before forming lobe-shaped structures called haustoria in almost every cell it contacts during a compatible interaction. These haustoria are invaginations of the plant cell that, while keeping the cell membrane intact, form an intimate interface between host and pathogen that aids nutrient acquisition and the delivery of effectors. Assuming successful infection, Hpa completes its life cycle within around 7 days, producing both asexual spores, which are carried by the tree-like conidiophores that emerge from the stomata, and sexual oospores (Coates and Beynon, 2010).

Whereas, progress is being made in identifying the key determinants of pathogenicity in Hpa and their effect on the host Arabidopsis, this progress is limited in comparison to other pathogens such as P. syringae, most notably because Hpa cannot be genetically manipulated. Several studies have looked at transcriptional change in response to Hpa infection (Huibers et al., 2009; Hok et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2011a; Asai et al., 2014), but it has been suggested that many of the key transcriptional events, which may occur exclusively in haustoriated cells, are often diluted by the comparative abundance of non-haustoriated cells when taking whole-organ samples (Huibers et al., 2009; Asai et al., 2014). Moreover, very little is known about the localization of Arabidopsis responses to Hpa, and how events which occur in haustoriated cells may differ from more systemic signaling events on a genome-wide scale. Making this distinction may be crucial in understanding how the haustorial environment influences the behavior of host cells.

In order to identify plant gene expression responses specifically in haustoriated cells, and to compare these to more systemic changes in gene expression during Hpa infection, we developed a method of isolating haustoriated cells from seedlings infected with the compatible Hpa isolate Noks1. The issue of dilution of highly localized pathogen responses has been previously overcome in the Arabidopsis-powdery mildew interaction in one published study, where by isolating infected cells through laser capture microdissection sensitivity of transcriptomic analysis was greatly increased (Chandran et al., 2010). Here, however, we chose to use Fluorescence Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) as it is a rapid way of isolating a large number of cells for gene expression analysis (Karve and Iyer-Pascuzzi, 2015). FACS is a flow cytometry technique that allows sorting of individual cells according to their fluorescence properties (Rogers et al., 2012), and has been a valuable tool for profiling the changing transcriptome of Arabidopsis roots during development at high spatial and temporal resolution (Brady et al., 2007). It has also been used extensively to characterize the cell type-specificity of root response to environmental/abiotic factors such as nitrogen content (Gifford et al., 2008) and salinity (Dinneny et al., 2008). FACS has also seen limited application to leaves (Grønlund et al., 2012) and analyzing the shoot apical meristem (Yadav et al., 2009), but has not been used before to study plant-pathogen interactions.

Here we used FACS to isolate haustoriated (Hpa-proximal) and non-haustoriated (Hpa-distal) cells from Hpa Noks1-inoculated Arabidopsis seedlings using the Hpa-responsive transgene ProDMR6:GFP at two time points. We demonstrated that the FACS-isolated cells can be used for transcriptional analysis, and identified 278 transcripts that are differentially expressed between the cell types, relative to uninfected controls or between the two time points. Included in these transcripts were many novel responses which may give us new insight into how infection-site-specific events may influence the outcome of downy mildew infection in Arabidopsis.

Materials and methods

Plant material and growth conditions

A 2.5 kb fragment of the DMR6 [At5g24530, Downy Mildew Resistant 6 (van Damme et al., 2008)] promoter was PCR-amplified from Arabidopsis (ecotype Col-0) using the primers proDMR-F (AAAAAGCAGGCTTCACCGACTCTGTCTGAGTCTGAAGTCCCAAACCATG) and proDMR-R (CAAGAAAGCTGGGTGCCGCCATTTGATGTCAGAAAATTGAAGAAG), followed by a second amplification with pAttB1 (GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCT) and pAttB2 (GGGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGGT), and cloned into the pDONRZeo plasmid (Invitrogen). The entry clone was then recombined with the binary vector pBGWFS7 (Karimi et al., 2002). The resulting plasmid was then introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101. Arabidopsis thaliana Col-0 plants were transformed using the Agrobacterium-mediated floral dipping technique (Clough and Bent, 1998), and successful transformant seeds selected on BASTA. Homozygous T3 plants with single insertions were used for all experiments. ProDMR6:GFP and Col-0 seeds were stratified for a minimum of 24 h before sowing onto soil, and were loosely covered with plastic film to retain moisture for the first 4 days after sowing. Plants were grown in a growth chamber (Weiss Technik, Vejle, Denmark) at 20°C with 10 h of light. The whole experiment was carried out in triplicate.

Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis (Hpa) propagation and inoculation

Hpa isolate Noks1 (Rehmany et al., 2005) was maintained on Arabidopsis Col-0 by weekly transfer to 7-day-old seedlings. Inoculum was collected from seedlings and sprayed at a concentration of 30,000–60,000 spores ml−1 onto new hosts according to Tomé et al. (2014). Spores were applied to 7-day-old seedlings carrying the ProDMR6:GFP transgene, or Col-0 wild type. These plants were then placed in water-tight propagator trays and incubated in a growth chamber (Weiss Technik, Vejle, Denmark) at 18°C with 10 h of light.

Imaging and microscopy

Images were acquired using a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope, in conjunction with the Zeiss ZEM software.

Protoplast generation and fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS)

Protoplasts were generated from seedling leaves according to Grønlund et al. (2012), but with the following alterations: (i) ProtectRNA and Actinomycin D were not used, (ii) vacuum infiltration was omitted, (iii) petri dishes were rotated on orbital shaker for only 45–60 min, and (iv) only one wash and centrifugation step was performed. FACS was performed according to Grønlund et al. (2012), using a workspace derived from Figure 3 of the publication. Cells were sorted directly into tubes containing 1 ml RLT cell lysis buffer (Qiagen) containing 1% β-mercaptoethanol, then samples stored at −80°C.

RNA extraction, cDNA amplification, and labeling

RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Plant Mini Kit according to manufacturers instructions (Qiagen). DNase treatment was performed on-column using TURBO DNase (Life Technologies), with dose dependent on the approximate number of sorted cells in the sample, as manufacturers instructions: GFP-positive samples, which typically contained ~20,000 cells, were treated with one unit of TURBO DNase and incubated at 37°C for 20 min; all other samples, which contained >100,000 cells, were given a second equal round of DNase I treatment. cDNA was amplified using the Ovation Pico WTA System (NuGen), then labeled with Cy3 using the One-Color DNA Labeling Kit (NimbleGen) according to manufacturers instructions. RNA integrity was measured using a 2100 Bioanalyzer Picochip (Agilent). cDNA and Cy3-labeled cDNA were quantified using a NanoDrop Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific).

Microarray hybridization and data normalization

Labeled cDNA samples were randomized and hybridized for 18 h on a 12x135k expression array custom designed for the TAIR10 A. thaliana genome annotation (Design ID OID37507; see GEO GSE58046, NimbleGen), then the arrays were washed, dried and scanned according to manufacturers instructions. The scanned microarray images were imported into DEVA software, and data outputted as raw.xys files. The data were then imported into R (R Development Core Team, 2008). The Robust Multichip Average (RMA) algorithm was used to normalize the data, taking outlier probes into account, and to summarize expression at the transcript level using median polish (Irizarry et al., 2003). All raw and normalized microarray data has been deposited in GEO (GSE67100).

Microarray data analysis

Linear Models for Microarray Data (package limma in R) was used to fit linear models to pairs of samples (Figure S3), identifying genes that contrasted the most between the experimental pairs (Smyth, 2004). Transcripts were differentially expressed if they showed an absolute log2 fold-change of ≥0.75 [a threshold previously used by Huibers et al. (2009)] and a Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted p ≤ 0.05 in at least one comparison. Published data was processed in the same way, except for the data from Huibers et al. (2009), which had been previously normalized. The Cytoscape plugin BiNGO was used to identify gene ontology (GO) terms overrepresented in transcript groups, using the default settings and the “GO full” database, and a significance threshold of Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted p ≤ 0.05. For grouping, transcripts found to be differentially expressed in any pairwise comparison between sample types at either 5 or 7 days post-inoculation (d.p.i.) were placed in order of their ratio of proximal change to distal change, measured as log2(ExpressionProximal/ExpressionControl)/log2(ExpressionDistal/ExpressionControl) and divided evenly into the final number of groups.

Results

ProDMR6::GFP as a fluorescent reporter for host cells containing Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis haustoria

In order to identify transcriptional events in A. thaliana that occur specifically in cells containing Hpa haustoria, we developed a method of using FACS to isolate haustoriated cells and non-haustoriated cells from Hpa-infected plants. This required a fluorescent reporter that is expressed specifically in haustoriated cells. van Damme et al. (2008) recently characterized the Arabidopsis gene Downy Mildew Resistant 6 (DMR6), which encodes a 2-oxoglutarate (2OG)-Fe(II) oxygenase and is required for susceptibility to Hpa isolate Waco9. By expressing a GUS reporter under the control of the DMR6 promoter they demonstrated that DMR6 expression is induced specifically in haustoriated cells, in both compatible and incompatible interactions with Hpa (van Damme et al., 2008). In order to assess ProDMR6 as a marker for isolating haustoriated cells using FACS, a construct containing 2.5 kb upstream of DMR6 was fused to the GFP coding sequence and used to transform Arabidopsis Col-0 plants.

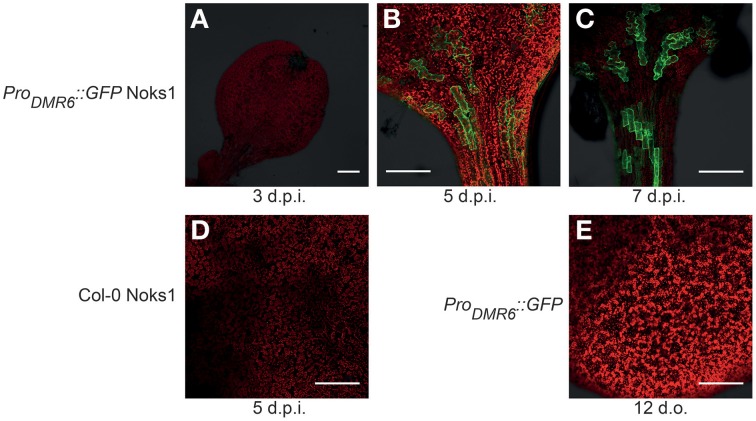

To investigate ProDMR6::GFP expression we screened 10-to-14-day-old T3 seedlings of four independent transformants using confocal microscopy. GFP expression was observed consistently in all transformants upon inoculation with the compatible Hpa isolate Noks1, and all transgenic lines behaved as Col-0 in terms of growth and development. Although van Damme et al. (2008) reported expression of ProDMR6::GUS as early as 2 d.p.i., we observed little or no fluorescence at 3 d.p.i. (Figure 1A). Instead, we observed strong fluorescence at 5 (Figure 1B) and 7 d.p.i. (Figure 1C). Fluorescent cells were observed adjacent to each other, suggestive of the pattern of Hpa infection (Figure S1), and this was confirmed to correlate with the visibility of conidiophores on the cotyledon surface at 7 d.p.i. (data not shown). We did not observe green fluorescence in Noks1-infected Col-0 seedlings (Figure 1D), or uninoculated ProDMR6::GFP seedlings (Figure 1E), at any time point, confirming that the GFP was expressed specifically upon Hpa infection in the marker line.

Figure 1.

Confocal microscopy images of Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis infection marker ProDMR6::GFP expression in Arabidopsis seedlings. Scale bar represents 0.25 mm. (A) Absence of GFP expression in ProDMR6::GFP seedlings infected with Hpa isolate Noks1, 3 d.p.i. (B,C) GFP expression in ProDMR6::GFP seedlings infected with Noks1 at (B) 5 d.p.i. and (C) 7 d.p.i. (D) Absence of GFP expression in a Noks1-inoculated Col-0 seedling, 5 d.p.i. (E) Absence of GFP expression in uninfected ProDMR6::GFP transgenic seedling; seedling is 12 days old, an equivalent age to a 5 d.p.i. seedlings.

Fluorescence activated cell sorting to isolate haustoriated and non-haustoriated cells from infected tissues

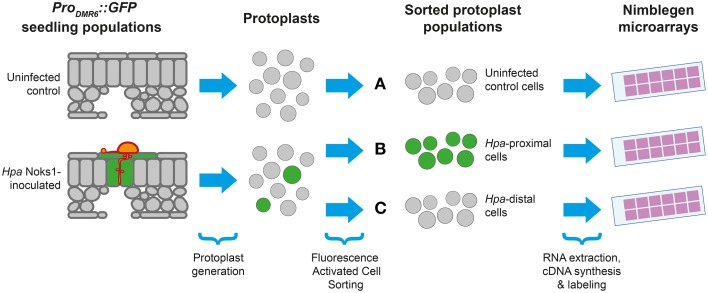

Having isolated an effective and specific marker of Hpa haustoriated cells, we designed an experiment allowing us to study the transcriptional response of Arabidopsis to Hpa Noks1 on a spatial scale (Figure 2). Seven-day-old ProDMR6::GFP seedlings were inoculated with Hpa isolate Noks1 and cotyledons sampled at 5 and 7 d.p.i. in three biological replicates. We chose 5 d.p.i., as this was when we could first observe GFP expression under the microscope, and 7 d.p.i., as it represents a point where the Hpa life cycle has completed (Coates and Beynon, 2010). Protoplasts were generated from these samples and cells sorted using FACS to obtain two cell populations: GFP-expressing cells, representing the haustoriated cell population and hereon referred to as “Hpa-proximal cells,” and non-GFP-expressing cells, representing the non-haustoriated cell population from infected plants, hereon be referred to as “Hpa-distal cells.” As a control and baseline for comparison, uninfected ProDMR6::GFP seedlings of the same age were also sampled at both time points, protoplasts generated and sorted through FACS.

Figure 2.

Experimental design for studying the Arabidopsis response to Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis (Hpa). Protoplasts were generated from populations of seedlings containing the ProDMR6::GFP transgene, with or without Hpa Noks1 infection, and sorted using Fluorescence Activated Cell Sorting to yield three types of cell population: (A) uninfected control cells, (B) GFP-positive cells from infected plants (Hpa-proximal cells), and (C) GFP-negative cells from infected plants (Hpa-distal cells). Whole genome expression profiling was performed from isolated cells at two time points (5 and 7 d.p.i), each with three biological replicates.

Protoplasts were generated using a recent protocol for FACS of leaf cells by Grønlund et al. (2012). Immediately prior to FACS, a small subset of the protoplasts derived from infected seedlings express GFP, consistent with the proportion of GFP expressing cells in infected seedling leaves. This GFP expression was detected upon FACS analysis (Figure S2). In contrast, GFP expressing cells were not observed in protoplasts from uninfected seedlings prior to FACS. From the 18 protoplast samples collected (three cell populations × two time points × three biological replicates), RNA was extracted, converted to cDNA, labeled, and hybridized to whole genome oligonucleotide Arabidopsis microarrays.

Differential expression of genes in Hpa-proximal and Hpa-distal cells gives insight local and systemic responses to the pathogen

Microarray gene expression was summarized at the transcript level and normalized using the RMA algorithm (Irizarry et al., 2003) (Table S1). In order to identify transcripts which were differentially expressed (DE) in Hpa-proximal cells, and to differentiate these from systemic signaling observed in cells distal to the infection site, we performed pairwise comparisons (Figure S3) across cell populations and time points using Linear Models for Microarray Data (LIMMA) (Smyth, 2004). A total of 278 transcripts were identified as differentially expressed at a cutoff of absolute log2 fold-change ≥0.75 and a Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted p-value ≤ 0.05 in at least one pairwise comparison (Table S2).

As a confirmation that the cells isolated by FACS were those that were Hpa-associated, among the 278 DE transcripts was DMR6 (At5g24530), which showed ~seven-fold upregulation in Hpa-proximal cells relative to uninfected control cells at 7 d.p.i. (Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted p = 0.035), and at 5 d.p.i. (Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted p = 0.061). We also observed upregulation of several other genes which have been previously implicated in the Hpa response, or as more general regulators of plant-pathogen interactions. These include Impaired Oomycete Susceptibility 1 (IOS1, At1g51800), Pathogenesis-Related 4 (PR4, At3g04720), Pathogen and Circadian Controlled 1 (PCC1, At3g22231), Flg22-induced Receptor-like Kinase 1 (FLK1, At2g19190) and WRKY8 (At5g46350) (Table S2).

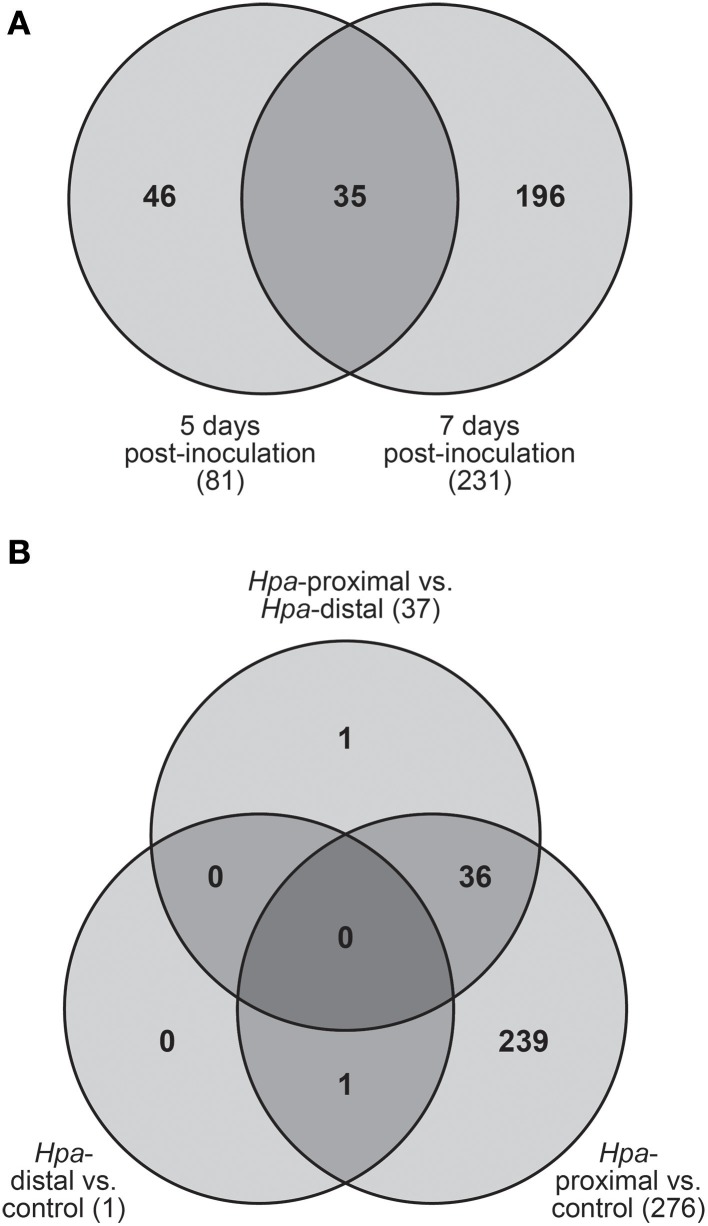

Of the 278 total DE transcripts, 81 and 231 transcripts were DE between the three cell types at 5 d.p.i. and 7 d.p.i. respectively, with 35 transcripts being DE over both time points (Figure 3A). 276 transcripts were DE between Hpa-proximal cells and uninfected control cells from the same time point, with 37 transcripts found to be DE between Hpa-proximal and Hpa-distal cells at the same time point (Figure 3B). A single transcript, At2g18660.1 (Plant Natriuretic Peptide A, PNP-A), was found to be DE between GFP-negative (Hpa-distal) cells from infected plants and cells from uninfected plants. Together with the detection of previously characterized Hpa responsive genes, the observation that the vast majority of transcriptional responses are being identified in the Hpa-proximal populations, rather than the Hpa-distal populations, from infected plants confirms that Hpa-responsive cells can be isolated using FACS.

Figure 3.

Transcripts found to be differentially expressed (DE) using pairwise contrasts in LIMMA. (A) Distribution of DE transcripts across the two time points. The vast majority of transcripts were found to be DE at 7 d.p.i. (B) Number of DE transcripts identified when making pairwise contrasts between cell types, taking into account both 5 and 7 d.p.i. The vast majority of transcripts were DE between Hpa-proximal cells and control cells from uninfected plants.

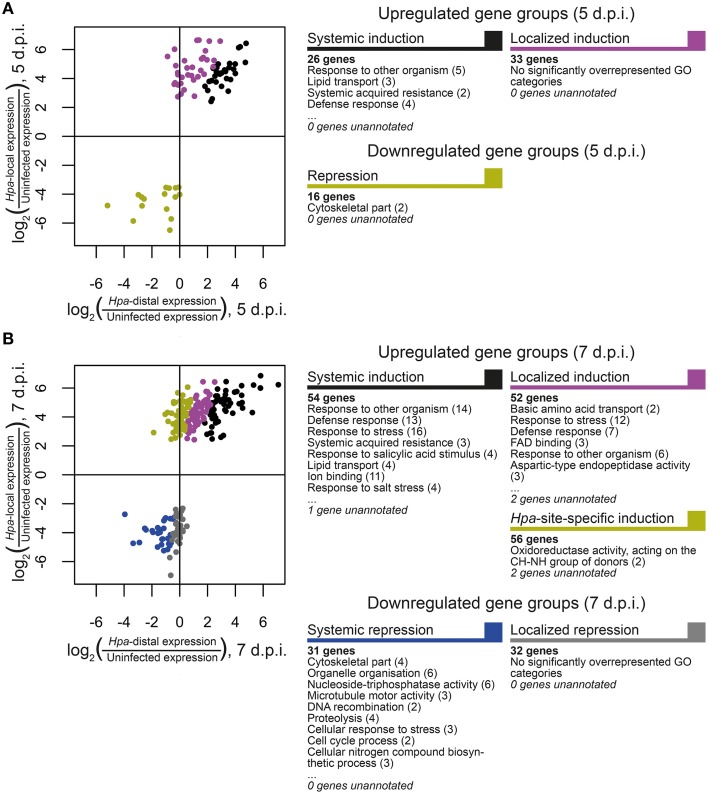

In order to discover what types of genes are responding locally vs. systemically, i.e., specifically in Hpa-proximal cells vs. more generally in both Hpa-proximal and Hpa-distal cells, the 278 DE transcripts were grouped according to the localization of their response at each of the time points, and these groups were searched for overrepresentation of GO terms using the Cytoscape plugin BiNGO (Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted p ≤ 0.05, Maere et al., 2005, Figure 4, Table S3). To take a more granular view of response location we chose to differentiate local and systemic genes based on the ratio of their Hpa-proximal response (log2 fold-change relative to uninfected control) to their Hpa-distal response; for a list of the genes within each group, see Table 1, Table S2.

Figure 4.

Grouping of differentially expressed Arabidopsis genes according to the direction and localization of response. Genes were grouped at (A) 5 d.p.i. and (B) 7 d.p.i. according to the nature of their response at that time point. Scatterplots display the ratio of Hpa-local and Hpa-distal expression to expression in uninfected control cells for each gene in each group. Selected GO categories that are overrepresented (Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted p ≤ 0.05) in each gene group are also displayed, with the number of associated genes in parentheses. A full list of overrepresented GO terms, their number IDs, with cluster and genomic frequencies and Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted p-values can be seen in Table S3.

Table 1.

Differentially expressed genes grouped according to the direction and localization of their response at 5 and 7 d.p.i.

At 5 and 7 d.p.i., transcripts were classified as either “upregulated” or “downregulated,” then split into groups according to the ratio of a Hpa-local response (measured as the log2 fold-change between Hpa-local cells and uninfected cells at that time point) and a Hpa-distal response (the fold-change between Hpa-distal and uninfected cells). See Figure 4 for a graphical representation of their expression pattern, Table S2 for expression values, and Table S3 for GO term analysis details.

The 81 transcripts DE at 5 d.p.i. were split into three groups (Figure 4A). For upregulated genes, we were interested in broadly comparing local and systemic responses, so we split the transcripts found to be upregulated at this time point into two groups—one representing systemic induction (almost equal proximal and distal response), and one representing localized induction (strong proximal response, weak distal response). The systemic induction group showed overrepresentation of pathology-related GO terms such as “response to other organism” and “defense response,” as well as “systemic acquired resistance,” fitting to the systemic expression pattern of the genes in this group. This suggests that, despite the lack of genes DE in Hpa-distal cells relative to the control, this population of cells is capturing systemic signaling in response to Hpa. Genes involved in lipid transport and localization were also overrepresented in this group. Individual genes represented in this group include Enhanced Disease Susceptibility to Erysiphe orontii (EDS16, At1g74710) and AVRPPHB Susceptible 3 (PBS3, At5g13320), which have both been implicated in salicylic acid accumulation in plant defense (Wildermuth et al., 2001; Nobuta et al., 2007), and Lysine Histidine Transporter 1 (LHT1, At5g40780), which has been shown to influence plant defense in a salicylic acid-mediated manner (Liu et al., 2010). The defense genes Pathogenesis-Related 4 (PR4, At3g04720) and Pathogen and Circadian Controlled 1 (PCC1, At3g22231) also fell into this group.

In contrast localized induction group did not show overrepresentation of any GO terms, suggesting a diversity of genes within this group. Individual genes represented in this group include the transcription factor WRKY29 (At4g23550), a terpene synthase (TPS4, At1g61120) and a peroxidase superfamily protein (At5g39580). The group also includes cysteine-rich receptor-like protein kinases ARCK1 (At1g11890) and CRK26 (At4g38830), and a monodehydroascorbate reductase (AtMDAR3, At3g09940) that is crucial for colonization of Arabidopsis by the mutualistic fungus Piriformospora indica (Vadassery et al., 2009).

Due to the small number of transcripts at this time point, downregulated genes could not effectively be split into “systemic” and “local” responding and were thus considered as one group. This group showed overrepresentation for only one GO term: “cytoskeletal part.” Downregulated genes include Callose Synthase 3 (At5g13000), peroxidase 12 (At1g71695) and a pathogenesis-related thaumatin superfamily protein (At1g73620).

The larger number (231) of transcripts DE at 7 d.p.i. allowed us to split them into more groups (Figure 4B). Transcripts upregulated at this time point were this time split into three gene groups—systemic induction, local induction and infection-site-specific induction, representing increasing localization of their response, such that genes in the infection-site-specific induction group showed a negligible Hpa-distal response. As with the systemic induction group at 5 d.p.i., the systemic induction group at 7 d.p.i. showed overrepresentation for the GO terms “lipid transport,” “systemic acquired resistance” and a number of generic defense-related terms such as “defense response.” The GO terms “response to salicylic acid stimulus” and “response to stress” were also additionally overrepresented in this group. Individual genes within this group include Pathogenesis-Related 4 (PR4, At3g04720) and 5 (PR5, At1g75040), WRKY59 (At2g21900), WRKY62 (At5g01900) and WRKY8 (At5g46350), Accelerated Cell Death 6 (ACD6, At4g14400), Plant Natriuretic Peptide A (PNP-A, At2g18660) and Late Upregulated in Response to Hyaloperonospora parasitica (LURP1, At2g14560). Surprisingly, DMR6 fell into this group, despite being used as our marker for Hpa-local cells. This could be due to weaker, more systemic signaling of DMR6 that was beyond detection using a GFP marker. As this data set is enriched for responses predominantly in Hpa-local cells, this too may also been an indication that even the most systemic responses captured remain fairly localized to the infection site.

The local induction group showed similar GO term enrichment to the systemic induction group at 7 d.p.i., such as the pathology-related terms “response to other organism” and “defense response” and the more generic “response to stress.” A number of receptor-like proteins were present in this group, including Flg22-induced Receptor-like Kinase 1 (FRK1, At2g19190), Cysteine-rich Receptor-like Kinase 13 (CRK13, At4g23210), Receptor Like Proteins 9 (AtRLP9, At1g58190) and 52 (AtRLP52, At5g25910) a putative CC-NBS-LRR class disease resistance protein (At1g58400) and a putative TIR-NBS class disease resistance protein (At4g09420). WRKY47, (At4g01720), WRKY72 (At5g15130) and WRKY38 (At5g22570) were also in this group.

Infection-site-specific induced, representing the most localized genes upregulated at 7 d.p.i., showed overrepresentation of only the GO term “oxidoreductase activity, acting on the CH-NH group of donors.” Genes in this group include the transcription factors WRKY36 (At1g69810), NAC3 (At3g29035) and NAC087 (At5g18270), as well as an RNA-binding Suppressor-of-White-APricot (SWAP) protein (At5g06520).

The larger number of downregulated genes at 7 d.p.i., relative to 5 d.p.i., allowed us to split them into two groups representing systemic and local repression. Genes that showed systemic repression were overrepresented for a number of cellular functions such as “cytoskeletal part,” “organelle organization,” “cell cycle process,” and “nucleoside-triphosphatase activity.” Genes in this group include a histone H1/H5 family member (At1g48620), metacaspase 3 (MC3, At5g64240) and A. thaliana Kinesins 1 (ATK1, At4g21270) and 12B (ATK12B, At3g23670).

Finally, there was no overrepresentation of GO terms in the localized repression group. Genes in this group included peroxidase 12 (PER12, At1g71695), the receptor protein kinase ERECTA (At2g26330), microtubule-associated protein 65-4 (MAP65-4, At3g60840) and Starch Synthase 3 (ATSS3, At1g11720).

Comparison with published data sets

To ask if the FACS approach identifies novel genes in the Arabidopsis response to Hpa infection, we compared our list of differentially expressed genes to previously published microarray data from Huibers et al. (2009), Wang et al. (2011a) and Hok et al. (2011). Data from these publications was retrieved from the relevant public databases and processed in a similar manner to the data we present here, i.e., differentially expressed genes identified by making pairwise contrasts in LIMMA. From each published dataset we considered only samples and direct comparisons that were most relevant to our experimental design here. Huibers et al. (2009) used two-color CATMA arrays to profile expression in a compatible Arabidopsis-Hpa interaction (Landsberg erecta (Ler) and Cala2) and an incompatible interaction (Ler and Waco9), relative to uninfected controls, at 3 d.p.i. Wang et al. (2011a) performed a 6-day timecourse of infection with the incompatible strain Emwa1, in Col-0 and the susceptible mutant rpp4. Finally, Hok et al. (2011) measured gene expression in Arabidopsis Wassilewskija (WS) seedlings after mock treatment, and treatment with the compatible isolate Emwa, at an early time point (8 and 24 h post-inoculation) and at a late time point (4 and 6 d.p.i.). For the former two datasets, we considered only the Cala2 interaction and the rpp4 interaction, respectively, as they represented compatible interactions that result in a similar outcome to the Col-0 and Noks1 interaction, i.e., completion of the Hpa lifecycle. For the latter two datasets, which have multiple time points, we considered all time points as to capture as much of the Hpa response as possible.

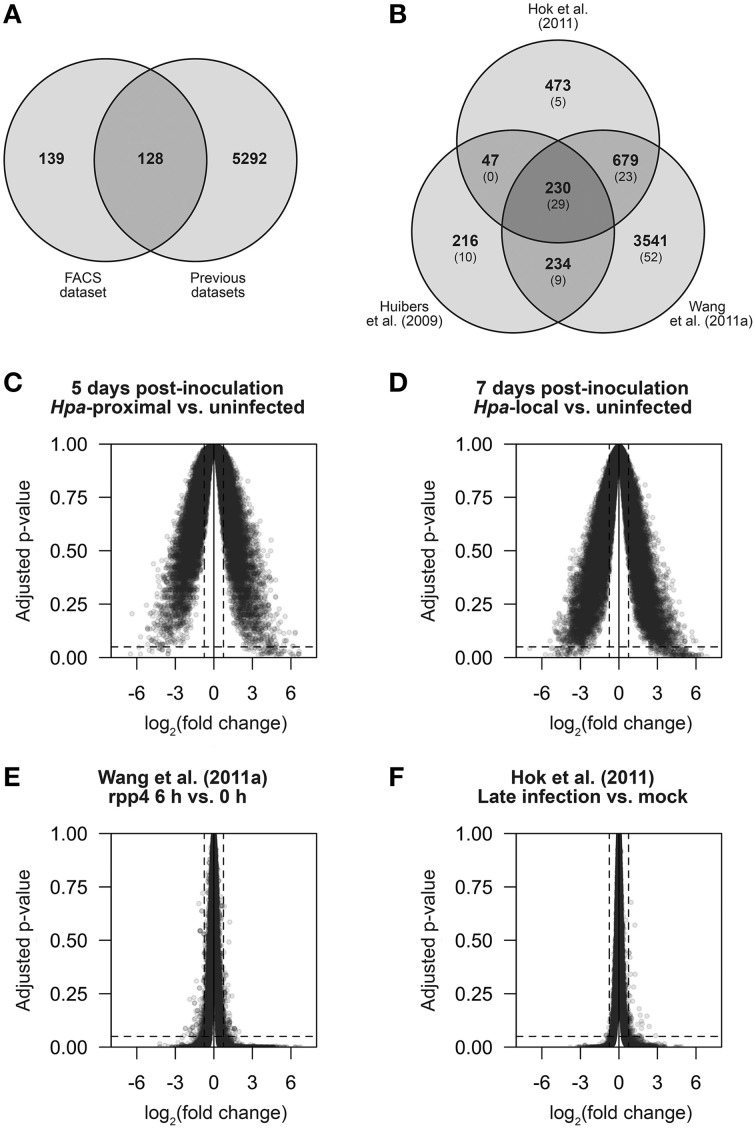

Our 278 differentially expressed transcripts represent 267 different genes—128 of which could be detected in the previously published datasets based on our analysis (Figure 5A). The remaining 139 genes are thus novel Hpa responses identified by our FACS-based cell response type specific approach. However, ~5300 transcripts were previously detected as differentially expressed in one or more of the datasets outlined above, but not differentially expressed in our dataset. A comparison between previous datasets shows that only a small proportion of these are common between datasets (Figure 5B), suggesting that these DE genes arose as differences in experimental design, Hpa strain used or otherwise may be false positives.

Figure 5.

The strength and specificity of Hpa-responsive gene detection in multiple datasets. In order to make direct comparisons, published data from Huibers et al. (2009), Wang et al. (2011a) and Hok et al. (2011) was processed in a similar manner to the data we present here. (A,B) Comparison of genes found to be differentially expressed (DE) using LIMMA. (A) Gene overlap of genes DE in our FACS dataset and genes found to be DE based on the previously published data. Of the 267 DE genes identified in our FACS dataset, 128 were previously detectable and 139 were novel. (B) Gene overlap between the three previously published datasets. In parentheses is the number of genes in each group that also overlap with our FACS dataset. (C–F) Average log2 fold change against Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted p-values for all measured transcripts (determined by LIMMA) in the comparisons: (C) Hpa-proximal vs. uninfected cells, 5 d.p.i. (D) Hpa-proximal vs. uninfected cells, 7 d.p.i. (E) Wang et al. (2011a) rpp4 Emwa1 6 d.p.i. vs. 0 d.p.i., (F) Hok et al. (2011) Emwa vs. Mock (late infection). Dotted lines represent the differential expression significance thresholds of absolute log2 fold change ≥0.75 and adjusted p ≤ 0.05.

In order to compare the sensitivity and specificity of our approach to the previously published data, we compared the average fold-change and Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted p-values for all genes for a number of pairwise comparisons across different datasets (Figures 5C–F). We found that our dataset had a larger proportion of genes with significant (≥0.75) log2 fold changes relative to an uninfected control than in the previously published datasets, and those identified as DE showed DE of a higher magnitude, highlighting that by specifically analyzing Hpa-proximal cells, we observe greater sensitivity in expression changes during infection (compare the width of plots in Figures 5C,D to Figures 5E,F). Conversely, the published datasets had a larger proportion of genes within the significance threshold of adjusted p ≤ 0.05, but with almost-zero fold-changes (Figures 5E,F). This suggests that, relative to the published datasets, although our data shows higher sensitivity, in this instance noise may be a limiting factor in Hpa-responsive gene detection.

Discussion

Here we present the novel use of FACS to isolate A. thaliana cells infected by the downy mildew pathogen Hpa. To our knowledge, this is the first use of FACS to specifically isolate plant cells responding to infection, although this has previously been achieved in animal systems (Richman et al., 2002; Thöne et al., 2007).

We demonstrate that cells isolated by FACS of Hpa-infected seedlings can be used for transcriptomic analysis of the local vs. systemic response to Hpa infection. Consistent with expectations that the majority of transcriptional events would occur at the infection site, all differentially expressed genes were either significantly upregulated or downregulated in the Hpa-proximal cell population, over time, or relative to an uninfected control or Hpa-distal cells from infection plants at the same time point. In contrast, only a single transcript showed significant differential expression between Hpa-distal cells and uninfected control cells. The identity of this transcript as Plant Natriuretic Peptide A (PNP-A, At2g18660) is assuring as PNP-A has been previously described as a secreted signal working systemically during both abiotic and biotic stress (Wang et al., 2011b). Ideally we would have identified further genes to be significantly differentially expressed in the Hpa-distal population, representing systemic signaling. However, as the Hpa-distal cell population was simply a collection of cells not expressing the haustoriated cell marker ProDMR6::GFP, we might expect this population to be heterogeneous, containing cells at varying proximity to the pathogen, many of which may not be responding to the pathogen at all. To address this potential dilution of systemic responses, we considered that many of the genes differentially expressed in Hpa-proximal cells may also be responding more systemically, and grouped these into the “Systemic Induction” and “Systemic Repression” groups in Figure 4. Several of the genes and GO terms associated with these groups are consistent with what is already known about defense signaling in Arabidopsis, such as the role of salicylic acid and salicylic acid-responsive gene expression in systemic acquired resistance (Durrant and Dong, 2004). However, no firm conclusions can currently be made from the analysis in Figure 4 and further experiments are needed to validate the localization of these responses, and to unravel their significance in the Hpa-Arabidopsis interaction.

The use of FACS to study cells specifically at the site of infection has potential to increase the sensitivity of transcriptomic or other high-throughput analyses, such as proteomics. We have shown that in general, the magnitude of up- or down-regulation of genes is greater in our FACS-isolated Hpa-proximal cells than in previous whole-leaf datasets, relative to uninfected controls (Figures 5C–F). We have also identified a number of genes that are differentially expressed in Hpa-proximal cells not previously detected in microarray studies (Figure 5A). However, we have also failed to detected many genes previously associated with Hpa infection. While many of these could potentially be attributed to differences in experimental design or the Hpa isolate used, it seems that noise is largely a contributing factor. Greater optimization of the FACS protocol will hopefully help to overcome this in the future.

A crucial development in the use of FACS for studying local vs. systemic signaling during Arabidopsis infection will be the development of new cell markers. A key challenge, particularly for the Hpa pathosystem, is that the pathogen and the proteins that it delivers into host cells cannot currently be fluorescently labeled through genetic manipulation. As such, isolation of Hpa-contacting cells relies entirely on pathogen-responsive Arabidopsis promoters, which may not be induced immediately and are likely to show changes in expression over the course of infection. This seems to be an issue with the DMR6 promoter, from which we could not detect GFP expression until 5 d.p.i. This prevented us from studying earlier stages of infection, which is unfortunate as it is at these stages that the use of FACS will be most informative, as the limited spread of the pathogen precludes the use of whole tissue microarrays. An additional caveat more relevant to this dataset, is that, at the later time points (e.g., 5 and 7 d.p.i.), recently haustoriated cells may not fluoresce, and may instead be interpreted as Hpa-distal cells. Characterizations of new, early-induced haustoriated cell markers, as well as an in-depth study of their expression patterns will be crucial in developing a refined FACS approach. Furthermore, to avoid dilution of the systemic response, one could use a second fluorophore to mark cells within a certain range of the pathogen. This could potentially be complex as signals and responses spread over space. In addition to developing new methods to study pathogen signaling at a cell-specific resolution, we must in turn develop theoretical methods to understand the data being generated, and perhaps take into account some of the assumptions and limitations of the FACS approach. As these methods develop, we can better understand the events that occur specifically at the Arabidopsis-Hpa interface, and how these might influence more widespread signaling in the plant.

Author contributions

TC, MG, and JB contributed to design of the experiment and interpretation of the data. VC generated the ProDMR6::GFP construct and plant lines, and TC and VC performed microscopy of these plants. Protoplast generation, FACS and microarray analysis was performed by TC. All authors wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank D. Tomé and J. Steinbrenner for maintenance of Hpa cultures and inoculation of experimental plants. We also thank D. Patel and J. Hulsmans for technical support with FACS. This work was supported by a BBSRC New Investigator grant BB/H109502/1 to MG, a BBSRC grant BB/F001347 to JB and the EPSRC/BBSRC funded Warwick Systems Biology Doctoral Training Centre to TLRC. All microarray data have been deposited in GEO (Series GSE58046), released upon publication.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpls.2015.00527

Confocal microscopy images of Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis (Hpa) infection marker ProDMR6::GFP expression in an Arabidopsis cotyledon, 7 d.p.i. with compatible Hpa isolate Noks1. (A,B) Expression of the marker follows the pattern of pathogen spread across the cotyledon. (C–E) Cells expressing the marker appear to contain haustoria.

Fluorescence expression profiles for cells analyzed and sorted with FACS. (A,B) Dot plots of output from the 580/30 nm vs. 530/40 nm bandpass filters on the BD Influx, using a workspace derived from Grønlund et al. (2012). (A) Protoplasts generated from uninfected, 14-day-old ProDMR6::GFP seedlings, where cells were collected exclusively from the low 580/low 530 (GFP-negative) fate. (B) Protoplasts generated from ProDMR6::GFP inoculated with Hpa isolate Noks1, at 7 d.p.i., where cells were collected from both the low 580/low 530 (GFP-negative) and low 580/high 530 (GFP-positive, ~0.5%) gates. The high 580/low 530 gate represents cell debris.

Pair-wise comparisons used to identify differentially expressed genes. Expression at 7 d.p.i. and 5 d.p.i. was compared for each cell type. Genes significantly differentially expressed in either Hpa-distal or Hpa-proximal cells, but not uninfected control cells, over time were considered as differentially expressed. To investigate differential expression between cell types, six comparisons were performed: Hpa-distal cells vs. uninfected control cells, Hpa-proximal cells vs. uninfected control cells, and Hpa-proximal cells vs. Hpa-distal cells, independently for each time point.

Normalized log2 expression data for uninfected control, Hpa-proximal, and Hpa-distal cells at 5 and 7 d.p.i. Gene IDs, names, and descriptions are given based on the TAIR10 genome annotation. Column names are given in the format “Cell type, time point, replicate,” where “Control5a” is control cells at 5 d.p.i., replicate 1.

Transcripts differentially expressed between uninfected control, Hpa-proximal, and Hpa-distal cells at 5 and 7 d.p.i. Gene IDs, names and descriptions are given based on the TAIR10 genome annotation. Mean log2 expression values are given in columns D-I–the names of these columns are given in the format “Cell type, time point,” where “Control5” is control cells at 5 d.p.i. Columns J-M are fold-changes for distal and proximal cells at 5 d.p.i. and 7 d.p.i., relative to uninfected controls at the respective time points. Columns N (“Group@5dpi”) and O (“Group@7dpi”) give the names of the groups which that transcript belonged to (see Figure 4), or state “Not DE” if not differentially expressed at that time point. Column P (“Newly detected?”) states “Yes” or “No” as to whether the gene is newly detected in our dataset, based on the analysis in Figure 5A.

Overrepresentation of Gene Ontology (GO) terms in Hpa-responsive gene groups. Hpa-responsive genes were grouped according to the localization of their response at 5 and 7 d.p.i. (see Table S2, Figure 4). All GO terms found to be overrepresented (Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted p ≤ 0.05) in the groups are included, other than those that were only represented by a single gene in a group, which were excluded. The percentage frequency of each GO term in the cluster and in the Arabidopsis thaliana genome (of the 27,594 GO-annotated genes), as well as a list of genes annotated with the GO term are included.

References

- Asai S., Rallapalli G., Piquerez S. J. M., Caillaud M. C., Furzer O. J., Ishaque N., et al. (2014). Expression profiling during Arabidopsis/downy mildew interaction reveals a highly-expressed effector that attenuates responses to salicylic acid. PLoS Pathog. 10:e1004443. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter L., Tripathy S., Ishaque N., Boot N., Cabral A., Kemen E., et al. (2010). Signatures of adaptation to obligate biotrophy in the Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis genome. Science 330, 1549–1551. 10.1126/science.1195203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady S. M., Orlando D. A., Lee J. Y., Wang J. Y., Koch J., Dinneny J. R., et al. (2007). A high-resolution root spatiotemporal map reveals dominant expression patterns. Science 318, 801–806. 10.1126/science.1146265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caillaud M. C., Asai S., Rallapalli G., Piquerez S., Fabro G., Jones J. D. G. (2013). A downy mildew effector attenuates salicylic acid-triggered immunity in Arabidopsis by interacting with the host mediator complex. PLoS Biol. 11:e1001732. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caillaud M. C., Piquerez S. J., Fabro G., Steinbrenner J., Ishaque N., Beynon J., et al. (2012). Subcellular localization of the Hpa RxLR effector repertoire identifies a tonoplast-associated protein HaRxL17 that confers enhanced plant susceptibility. Plant J. 69, 252–265. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04787.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandran D., Inada N., Hather G., Kleindt C. K., Wildermuth M. C. (2010). Laser microdissection of Arabidopsis cells at the powdery mildew infection site reveals site-specific processes and regulators. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 460–465. 10.1073/pnas.0912492107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough S. J., Bent A. F. (1998). Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 16, 735–743. 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coates M. E., Beynon J. L. (2010). Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis as a pathogen model. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 48, 329–345. 10.1146/annurev-phyto-080508-094422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinneny J. R., Long T. A., Wang J. Y., Mace D., Pointer S., Barran C., et al. (2008). Cell identity mediates the response of Arabidopsis roots to salinity and iron stress. Science 320, 942–945. 10.1126/science.1153795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durrant W. E., Dong X. (2004). Systemic acquired resistance. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 42, 185–209. 10.1146/annurev.phyto.42.040803.140421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabro G., Steinbrenner J., Coates M., Ishaque N., Baxter L., Studholme D. J., et al. (2011). Multiple candidate effectors from the oomycete pathogen Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis suppress host plant immunity. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1002348. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gifford M. L., Dean A., Gutierrez R. A., Coruzzi G. M., Birnbaum K. D. (2008). Cell-specific nitrogen responses mediate developmental plasticity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 803–808. 10.1073/pnas.0709559105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grønlund J. T., Eyres A., Kumar S., Buchanan-Wollaston V., Gifford M. L. (2012). Cell specific analysis of Arabidopsis leaves using fluorescence activated cell sorting. J. Vis. Exp. 4:4214 10.3791/4214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hok S., Danchin E. G. J., Allasia V., Panabieres F., Attard A., Keller H. (2011). An Arabidopsis (malectin-like) leucine-rich repeat receptor-like kinase contributes to downy mildew disease. Plant Cell Environ. 34, 1944–1957. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2011.02390.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holub E. B. (2007). Natural variation in innate immunity of a pioneer species. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 10, 415–424. 10.1016/j.pbi.2007.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huibers R. P., de Jong M., Dekter R. W., Van den Ackerveken G. (2009). Disease-specific expression of host genes during downy mildew infection of Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 22, 1104–1115. 10.1094/MPMI-22-9-1104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irizarry R. A., Hobbs B., Collin F., Beazer-Barclay Y. D., Antonellis K. J., Scherf U., et al. (2003). Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics 4, 249–264. 10.1093/biostatistics/4.2.249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones J. D. G., Dangl J. L. (2006). The plant immune system. Nature 444, 323–329. 10.1038/nature05286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimi M., Inze D., Depicker A. (2002). GATEWAY vectors for Agrobacterium-mediated plant transformation. Trends Plant Sci. 7, 193–195. 10.1016/S1360-1385(02)02251-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karve R., Iyer-Pascuzzi A. S. (2015). Digging deeper: high-resolution genome-scale data yields new insights into root biology. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 24, 24–30. 10.1016/j.pbi.2015.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapin D., Van den Ackerveken G. (2013). Susceptibility to plant disease: more than a failure of host immunity. Trends Plant Sci. 18, 546–554. 10.1016/j.tplants.2013.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G., Ji Y., Bhuiyan N. H., Pilot G., Selvaraj G., Zou J., et al. (2010). Amino acid homeostasis modulates salicylic acid-associated defense responses in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 22, 3845–3863. 10.1105/tpc.110.079392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maere S., Heymans K., Kuiper M. (2005). BiNGO: a cytoscape plugin to assess overrepresentation of gene ontology categories in biological networks. Bioinformatics 21, 3448–3449. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhtar M. S., Carvunis A. R., Dreze M., Epple P., Steinbrenner J., Moore J., et al. (2011). Independently evolved virulence effectors converge onto hubs in a plant immune system network. Science 333, 596–601. 10.1126/science.1203659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobuta K., Okrent R. A., Stoutemyer M., Rodibaugh N., Kempema L., Wildermuth M. C., et al. (2007). The GH3 acyl adenylase family member PBS3 regulates salicylic acid-dependent defense responses in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 144, 1144–1156. 10.1104/pp.107.097691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. (2008). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Available online at: URL http://www.R-project.org [Google Scholar]

- Rehmany A. P., Gordon A., Rose L. E., Allen R. L., Armstrong M., Whisson S. C., et al. (2005). Differential recognition of highly divergent downy mildew avirulence gene alleles by RPP1 resistance genes from two Arabidopsis lines. Plant Cell 17, 1839–1850. 10.1105/tpc.105.031807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richman L., Meylan P. R., Munoz M., Pinaud S., Mirkovitch J. (2002). An adenovirus-based fluorescent report vector to identify and isolate HIV-infected cells. J. Virol. Methods 99, 9–21. 10.1016/S0166-0934(01)00375-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers E. D., Jackson T., Moussaieff A., Sharoni A., Benfey P. N. (2012). Cell type-specific transcriptional profiling: implications for metabolite profiling. Plant J. 70, 5–17. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.04888.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth G. K. (2004). Linear models and empirical Bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat. Appl. Genet. Mol. Biol. 3, Article 3. 10.2202/1544-6115.1027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thöne F., Schwanhausser B., Becker D., Ballmaier M., Bumann D. (2007). FACS-isolation of Salmonella-infected cells with defined bacterial load from mouse spleen. J. Microbiol. Methods 71, 220–224. 10.1016/j.mimet.2007.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomé D. F., Steinbrenner J., Beynon J. L. (2014). A growth quantification assay for Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis isolates in Arabidopsis thaliana. Methods Mol. Biol. 1127, 145–158. 10.1007/978-1-62703-986-4_12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuda K., Somssich I. E. (2015). Transcriptional networks in plant immunity. New Phytol. 206, 932–947. 10.1111/nph.13286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vadassery J., Tripathi S., Prasad R., Varma A., Oelmüller R. (2009). Monodehydroascorbate reductase 2 and dehydroascorbate reductase 5 are crucial for a mutualistic interaction between Piriformospora indica and Arabidopsis. J. Plant Physiol. 166, 1263–1274. 10.1016/j.jplph.2008.12.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Damme M., Huibers R. P., Elberse J., Van den Ackerveken G. (2008). Arabidopsis DMR6 encodes a putative 2OG-Fe(II) oxygenase that is defense-associated but required for susceptibility to downy mildew. Plant J. 54, 785–793. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03427.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Barnaby J. Y., Tada Y., Li H., Tor M., Caldelari D., et al. (2011a). Timing of plant immune responses by a central circadian regulator. Nature 470, 110–115. 10.1038/nature09766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. H., Gehring C., Irving H. R. (2011b). Plant natriuretic peptides are apoplastic and paracrine stress responses molecules. Plant Cell Physiol. 52, 837–850. 10.1093/pcp/pcr036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildermuth M. C., Dewdney J., Wu G., Ausubel F. M. (2001). Isochorismate synthase is required to synthesize salicylic acid for plant defence. Nature 414, 562–565. 10.1038/35107108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav R. K., Girke T., Pasala S., Xie M., Reddy G. V. (2009). Gene expression map of the Arabidopsis shoot apical meristem stem cell niche. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 4941–4946. 10.1073/pnas.0900843106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeilmaker T., Ludwig N. R., Elberse J., Seidl M. F., Berke L., Van Doorn A., et al. (2015). DOWNY MILDEW RESISTANT 6 and DMR6-LIKE OXYGENASE 1 are partially redundant but distinct suppressors of immunity in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 81, 210–222. 10.1111/tpj.12719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zipfel C. (2014). Plant pattern-recognition receptors. Trends Immunol. 35, 345–351. 10.1016/j.it.2014.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Confocal microscopy images of Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis (Hpa) infection marker ProDMR6::GFP expression in an Arabidopsis cotyledon, 7 d.p.i. with compatible Hpa isolate Noks1. (A,B) Expression of the marker follows the pattern of pathogen spread across the cotyledon. (C–E) Cells expressing the marker appear to contain haustoria.

Fluorescence expression profiles for cells analyzed and sorted with FACS. (A,B) Dot plots of output from the 580/30 nm vs. 530/40 nm bandpass filters on the BD Influx, using a workspace derived from Grønlund et al. (2012). (A) Protoplasts generated from uninfected, 14-day-old ProDMR6::GFP seedlings, where cells were collected exclusively from the low 580/low 530 (GFP-negative) fate. (B) Protoplasts generated from ProDMR6::GFP inoculated with Hpa isolate Noks1, at 7 d.p.i., where cells were collected from both the low 580/low 530 (GFP-negative) and low 580/high 530 (GFP-positive, ~0.5%) gates. The high 580/low 530 gate represents cell debris.

Pair-wise comparisons used to identify differentially expressed genes. Expression at 7 d.p.i. and 5 d.p.i. was compared for each cell type. Genes significantly differentially expressed in either Hpa-distal or Hpa-proximal cells, but not uninfected control cells, over time were considered as differentially expressed. To investigate differential expression between cell types, six comparisons were performed: Hpa-distal cells vs. uninfected control cells, Hpa-proximal cells vs. uninfected control cells, and Hpa-proximal cells vs. Hpa-distal cells, independently for each time point.

Normalized log2 expression data for uninfected control, Hpa-proximal, and Hpa-distal cells at 5 and 7 d.p.i. Gene IDs, names, and descriptions are given based on the TAIR10 genome annotation. Column names are given in the format “Cell type, time point, replicate,” where “Control5a” is control cells at 5 d.p.i., replicate 1.

Transcripts differentially expressed between uninfected control, Hpa-proximal, and Hpa-distal cells at 5 and 7 d.p.i. Gene IDs, names and descriptions are given based on the TAIR10 genome annotation. Mean log2 expression values are given in columns D-I–the names of these columns are given in the format “Cell type, time point,” where “Control5” is control cells at 5 d.p.i. Columns J-M are fold-changes for distal and proximal cells at 5 d.p.i. and 7 d.p.i., relative to uninfected controls at the respective time points. Columns N (“Group@5dpi”) and O (“Group@7dpi”) give the names of the groups which that transcript belonged to (see Figure 4), or state “Not DE” if not differentially expressed at that time point. Column P (“Newly detected?”) states “Yes” or “No” as to whether the gene is newly detected in our dataset, based on the analysis in Figure 5A.

Overrepresentation of Gene Ontology (GO) terms in Hpa-responsive gene groups. Hpa-responsive genes were grouped according to the localization of their response at 5 and 7 d.p.i. (see Table S2, Figure 4). All GO terms found to be overrepresented (Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted p ≤ 0.05) in the groups are included, other than those that were only represented by a single gene in a group, which were excluded. The percentage frequency of each GO term in the cluster and in the Arabidopsis thaliana genome (of the 27,594 GO-annotated genes), as well as a list of genes annotated with the GO term are included.