Abstract

In deciding on the treatment plan for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), the burden of COPD as experienced by patients should be the core focus. It is therefore important for daily practice to develop a tool that can both assess the burden of COPD and facilitate communication with patients in clinical practice. This paper describes the development of an integrated tool to assess the burden of COPD in daily practice. A definition of the burden of COPD was formulated by a Dutch expert team. Interviews showed that patients and health-care providers agreed on this definition. We found no existing instruments that fully measured burden of disease according to this definition. However, the Clinical COPD Questionnaire meets most requirements, and was therefore used and adapted. The adapted questionnaire is called the Assessment of Burden of COPD (ABC) scale. In addition, the ABC tool was developed, of which the ABC scale is the core part. The ABC tool is a computer program with an algorithm that visualises outcomes and provides treatment advice. The next step in the development of the tool is to test the validity and effectiveness of both the ABC scale and tool in daily practice.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) imposes a great burden on patients and is a major cause of morbidity with a significant impact on the wider economy.1

Airway obstruction used to play an important role in assessing disease severity and in treating COPD. Nowadays, the focus of COPD assessment shifts from merely airway obstruction towards patient-reported outcomes. Hence, the assessment addresses complaints, limitations in daily and social life, the progression of disease, and quality of life from the patients’ perspective.2

Research has shown that multidimensional indicators, such as the Body Mass Index, Airflow Obstruction, Dyspnoea, and Exercise Capacity Index3 and quality of life,4 are better predictors of morbidity, mortality and health-care utilisation than the forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) alone. Agusti and MacNee5 describe the necessity of a more personalised approach.

The development of our novel Assessment of Burden of COPD (ABC) tool intends to contribute to this approach. It allows quantification and visualisation of the burden of COPD, thereby facilitating the integrated approach crucial for assessment and individualised treatment of COPD.

A Dutch expert team was instituted by the Dutch Lung Alliance (in Dutch: Long Alliantie Nederland, LAN) to develop a tool to measure the burden of COPD. Several steps were taken to develop this tool. The first step was to define the burden of COPD. The following definition was formulated:

Burden of disease is the physical, emotional, psychological and/or social experiences of a patient with COPD. These experiences influence the patient´s ability to cope with the consequences of COPD and its treatment.

The second step was to validate this definition with the experiences of patients and health-care providers. Therefore, three focus group interviews with a total of 17 patients, 21 face-to-face interviews with different health-care professionals and three home visits to severely ill, homebound COPD patients were conducted. The interviews confirmed that our definition was in line with the experiences of patients and health-care providers.

The third step was to define the conditions that a burden of COPD instrument should meet. The Dutch expert group formulated nine conditions (Box 1).

Requirements for measuring burden of COPD.

The instrument should meet the following requirements:

- include indicators that provide insight into impairments, disabilities, complaints and quality of life resulting from COPD;

- take no more than a few minutes to complete;

- have an easy score calculation;

- have the potential to be self-administered by patients.

- subscores of the different domains and a total score;

- minimum and maximum length variants.

- measure the physical, emotional, psychological and social experiences of patients with COPD;

- take no more than a few minutes to complete;

- have an easy score calculation;

- have the potential to be self-administered by patients.

- subscores of the different domains and a total score;

- minimum and maximum length variants.

- based on patient input;

- take no more than a few minutes to complete;

- have an easy score calculation;

- have the potential to be self-administered by patients.

- subscores of the different domains and a total score;

- minimum and maximum length variants.

- easy for both patient and caregiver to manage and should therefore:

- take no more than a few minutes to complete;

- have an easy score calculation;

- have the potential to be self-administered by patients.

- subscores of the different domains and a total score;

- minimum and maximum length variants.

- responsive to change in patients;

- subscores of the different domains and a total score;

- minimum and maximum length variants.

- able to measure differences between patients;

- subscores of the different domains and a total score;

- minimum and maximum length variants.

- have a visual display including:

- subscores of the different domains and a total score;

- minimum and maximum length variants.

able to guide treatment;

possibility to connect with generic Quality of Life instruments such as the SF36 (i.e., capable of obtaining and calculating QALYs (Quality Adjusted Life Years; societal perspective)).

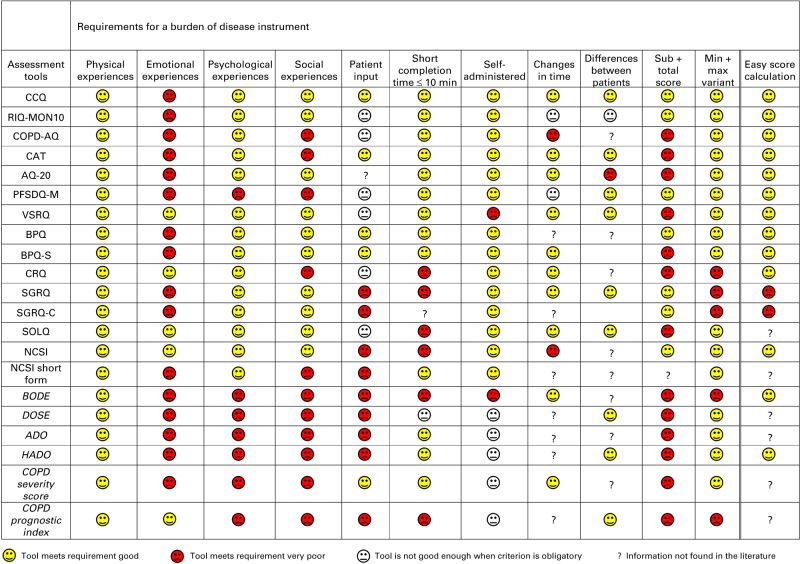

The fourth step was to perform a literature review to search for questionnaires, instruments or indexes that measure the burden of COPD. The literature review revealed that the currently available instruments do not fully measure the burden of disease according to our definition and they do not meet all the formulated requirements (Figure 1). However, the Clinical COPD Questionnaire (CCQ) met most requirements and was therefore considered to be closest to reflecting the concept of burden of COPD. The CCQ has shown good validity, reliability and responsiveness at group and individual levels.6,7

Figure 1.

An overview of assessment tools in relation to requirements for a burden of disease instrument.

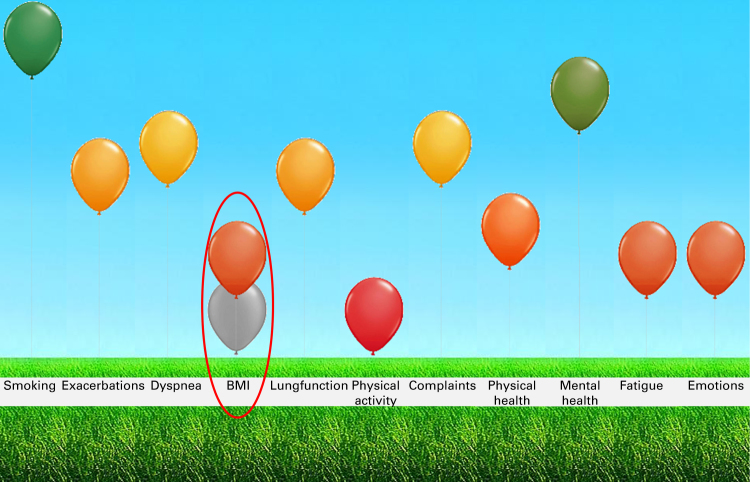

The fifth step was to develop the ABC scale using the CCQ as a basis. This scale is the core part of the ABC tool. The CCQ was adapted by adding questions for the lacking domains of emotions8 and fatigue.9 Three items were added to measure emotional experiences. These items are based on the distress screener of the four-dimensional symptom questionnaire,8 which measures listlessness, worry and feeling tense. The questions from the distress screener were revised to match the format of the CCQ questions. Furthermore, a question was added about fatigue, based on a study by Van Hooff et al. 9 This item was also formulated in the same way as the questions on the CCQ. The 14 items together form the ABC scale (Table 1). The combination of the ABC scale with objective items—such as a patient’s smoking status and body mass index—creates a measure of the integrated health status of an individual COPD patient. We developed a computer program to visualise the integrated health status of a COPD patient, represented as a balloon for each item of the ABC tool (Figure 2). The combination of the ABC scale, the additional indicators and the visualisation of the scores together forms the ABC tool. A high, green balloon indicates that a patient scores well on a particular item. These green balloons can be used to compliment the patient (e.g., not smoking) and to encourage the patient to continue that behaviour. A low, red balloon indicates that the patient experiences problems on that item. Every score in between is indicated with an orange balloon. The red and dark-orange balloons can be the starting point of discussing the options for improvement with the patient during consultations. Hence, it forms the basis for shared decision making (SDM). Furthermore, an algorithm was developed to link the scores on the integrated health status with treatment advices. These were based on (inter)national treatment guidelines. This advice can guide the patient and care provider towards an integrated and personalised therapy. The ABC tool is consistent with SDM principles.10 The patient is considered to have a certain level of responsibility in the treatment that lies within his or her possibilities. The patient and health-care provider together can select one balloon on which to elaborate further (SDM choice phase). Clicking on a balloon gives access to treatment options (SDM option phase). The patient and health-care provider can then decide on the treatment goal by selecting an option and placing it in the patient’s treatment plan (SDM decision phase). This goal can then be adjusted further to the individual patient’s needs and preferences. SDM and a personal goal are important in motivating patients to feel responsible for their own treatment and well-being. When treatment advice is followed and the treatment is effective, the consequence is that the balloon for that particular item (e.g. body mass index) will move to a higher (more green) position or will not further decrease. As shown in Figure 2, patients see both the current balloons and the balloons of the previous consultation, which are made gray. The tool can therefore be used during each consultation to monitor a patient’s integrated health status over time. The next step in the development of the tool is to test its validity, its responsiveness and its effectiveness. Therefore it is important to perform a randomised clinical trial that investigates whether the quality of care and quality of life can be improved by using the ABC tool.

Table 1. The Assessment of Burden of COPD scale.

| Never | Hardly ever | A few times | Several times | Many times | A great many times | Almost all the time | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

On average, during the past week, how often did you feel:

| |||||||

| 1. Short of breath at rest? | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 2. Short of breath doing physical activities? | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 3. Concerned about getting a cold or your breathing getting worse? | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 4. Depressed (down) because of your breathing problems? | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

|

In general, during the past week, how much of the time:

| |||||||

| 5. Did you cough? | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 6. Did you produce phlegm? | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

|

| |||||||

| Not limited at all | Very slightly limited | Slightly limited | Moderately limited | Very limited | Extremely limited | Totally limited/ or unable to do | |

|

On average, during the past week, how limited were you in these activities because of your breathing problems:

| |||||||

| 7. Strenuous physical activities (such as climbing stairs, hurrying, doing sports)? | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 8. Moderate physical activities (such as walking, house work, carrying things)? | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 9. Daily activities at home (such as dressing, washing yourself)? | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 10. Social activities (such as talking, being with children, visiting friends/relatives)? | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

|

| |||||||

| Never | Hardly ever | A few times | Several times | Many times | A great many times | Almost all the time | |

|

How often in the past week did you suffer from:

| |||||||

| 11. Worry? | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 12. Listlessness? | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 13. A tense feeling? | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 14. Fatigue? | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

Figure 2.

Visualisation of the dimensions influencing integrated health status (Assessment of Burden of COPD tool), changed after treatment.

Acknowledgments

The ABC tool was developed under the auspices of the Lung Alliance Netherlands (Dutch: Long Alliantie Nederland, LAN) and prepared by an expert team installed by the LAN. The initiative for the development of the instrument was taken by PICASSO for COPD. We would like to thank Maarten Fisher, who conducted the group interviews with COPD patients. We would also like to thank the patients and health-care providers who participated in the interviews.

OCPvS received several unrestricted institutional grants from Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca and GlaxoSmithKline. OCPvS is an Assistant editor of the PCRJ, but was not involved in the editorial review of, nor the decision to publish, this article. TvdM developed the CCQ, received grants, reimbursement for travel and fees for speaking, and is on the advisory boards of AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, Teva and MSD. The Erasmus University, Institute for Medical Technology Assessment, where MPMHR-vM is employed, has received funding for designing and conducting cost-effectiveness studies of COPD drugs from multiple pharmaceutical companies (Boehringer Ingelheim, Nycomed, Pfizer). MPMHR-vM has received speaker fees and compensation for serving on the advisory boards of GSK, Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, Nycomed and Novartis. MPMHR-vM does not own stock of any pharmaceutical company. PNRD has received reimbursements for attending symposia, fees for speaking and organising educational events, funds for research or fees for consulting from AstraZeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Chiesi, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Mundipharma, Novartis, Takeda, Almirall and Teva. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global strategy for diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD, 2014. Available at http://www.goldcopd.org/ .

- Jones P, Miravitlles M, Van der Molen T, Kulich K. Beyond FEV1 in COPD: a review of patient-reported outcomes and their measurement. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2012;7:697–709. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S32675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celli BR, Cote CG, Marin JM, Casanova C, Montes de Oca M, Mendez RA. The body-mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnea, and exercise capacity index in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1005–1012. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santo Tomas LH, Varkey B. Improving health-related quality of life in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2004;10:120–127. doi: 10.1097/00063198-200403000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agusti A, Macnee W. The COPD control panel: towards personalised medicine in COPD. Thorax. 2013;68:687–690. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocks JW, Asijee GM, Tsiligianni IG, Kerstjens HA, van der Molen T. Functional status measurement in COPD: a review of available methods and their feasibility in primary care. Prim Care Respir J. 2011;20:269–275. doi: 10.4104/pcrj.2011.00031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Molen T, Willemse BW, Schokker S, Ten Hacken NH, Postma DS, Juniper EF.Development, validity and responsiveness of the Clinical COPD Questionnaire Health Qual Life Outcomes 20031 , http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-1-13 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braam C, van Oostrom SH, Terluin B, Vasse R, de Vet HC, Anema JR. Validation study of a distress screener. J Occup Rehabil. 2009;19:231–237. doi: 10.1007/s10926-009-9178-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Hooff ML, Geurts SA, Kompier MA, Taris TW. ‘How fatigued do you currently feel?’ Convergent and discriminant validity of a single-item fatigue measure. J Occup Health. 2007;49:224–234. doi: 10.1539/joh.49.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makoul G, Clayman ML. An integrative model of shared decision making in medical encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;60:301–312. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]