Most children will have a skin infection at some time. Skin infections are a common reason for consultation in primary care and in dermatology practice.1-3 We review four common skin infections in children and describe their epidemiology, clinical features, and treatment, focusing on treatments with best evidence.

Sources and selection criteria

We searched Medline and the Cochrane Library using the terms “molluscum,” “warts,” “impetigo,” and “tinea.” We included randomised trials, meta-analyses, and clinical guidelines.

Molluscum contagiosum

Molluscum contagiosum is a common, benign, self limiting viral infection of the skin. It generally affects children and is caused by a human specific poxvirus. Infection is rare in children under 1 year of age and typically occurs in the 2-5 year age group.4 Although the prevalence of molluscum contagiosum is not known, one of six Dutch children have visited their doctor for the condition.5

Infection follows autoinoculation or contact with affected people.6 The incubation period is from two weeks to six months. The condition is more common in young children and in children who swim, who bathe together, and who are immunosuppressed. Little evidence supports the view that lesions (mollusca) are more common in children with atopic dermatitis.

Mollusca present as multiple dome shaped pearly or flesh coloured papules with a central depression (umbilication), which usually appear on the trunk and flexural areas (fig 1). They vary in size from 1 mm to 10 mm, with growth occurring over several weeks.4 In patients who are immunocompetent, lesions may persist for six to eight weeks. The mean duration is at least eight months when new lesions appear due to continuous autoinoculation.6 Resolution is often preceded by inflammation. Uncomplicated lesions heal without scarring.

Fig 1.

Typical multiple dome shaped pearly or flesh coloured papules of mollluscum contagiosum, with a central depression (umbilication)

Credit: DOIA

Whether doctors should treat molluscum contagiosum is controversial. As the condition is benign and typically resolves spontaneously, treatment is usually not necessary. Advocates of treatment state that intervention speeds resolution, reduces self inoculation and symptoms, limits spread, and prevents scarring. Often there is pressure from parents to treat their otherwise healthy children because of the stigma of visible lesions.7

Summary points

Molluscum contagiosum is a common, self limiting condition

Topical salicylic acid should be regarded as first line treatment for cutaneous viral warts

Mild impetigo is effectively treated with topical mupirocin or fusidic acid for seven days

Oral antibiotics should be reserved for recalcitrant, extensive impetigo with systemic symptoms

Tinea capitis should be considered in every child with a scaly scalp as the infection is common and the presentation diverse

Tinea capitis should be confirmed by mycological analysis before an eight week course of griseofulvin is started

Treatment

Many treatments for molluscum contagiosum have been reported, including physical destruction or manual extrusion of the lesions, cryotherapy, and curettage. Treatments are painful, and there is limited evidence that they are more effective than watchful waiting. One study found no difference in resolution of lesions after extrusion of the umbilicated core compared with destruction of the lesion using phenol, although treatment with phenol produced notably more scarring.6 Acidified nitrite cream has been reported as effective and painless.8 Topical imiquimod cream may be useful in widespread or recalcitrant mollusca, but it has not been tested in controlled trials.9

A Cochrane review is under way to evaluate treatments for molluscum contagiosum. Until there is clear evidence of safety and efficacy of active intervention, we recommend watchful waiting and reassurance of patients and parents.

Viral warts

Cutaneous viral warts are discrete benign epithelial proliferations caused by the human papillomavirus. Several types occur (box 1).

Viral warts are common.10 Prevalence increases during childhood, peaks in adolescence, and declines thereafter.11 In healthy children, warts resolve spontaneously; 93% of children with warts at age 11 showed resolution by age 16.12 Resolution can be preceded by the appearance of blackened thrombosed capillary loops. Warts may be widespread and persistent in patients who are immunocompromised. The clinical appearance of warts depends on their location. The hands and feet are most commonly affected (fig 2).

Fig 2.

Cutaneous viral wart showing characteristic hyperkeratotic “warty” surface with capillary loops (black dots)

Box 1: Types of viral warts

Common warts

Common warts begin as smooth flesh coloured papules that enlarge and develop a characteristic hyperkeratotic surface of grossly thickened keratin. They can occur at sites of injury (Koebner phenomenon)

Plantar warts (verrucae)

Plantar warts occur on the soles of the feet and can be painful. They protrude only slightly from the surface of the skin and often have a surrounding collar of keratin

Mosaic warts

Mosaic warts occur as collections of small, discrete and densely packed individual warts. They are often resistant to treatment

Plane warts

Plane warts are flat topped papules, typically scattered over the face, arms, and legs

Treatment

Although most warts resolve spontaneously within two years, some persist and become large and painful. For this reason many parents present their children for medical treatment. Treatment in children should be simple, cheap, effective, safe, and relatively painless.

Salicylic acid

Topical salicylic acid has been shown to be beneficial in treating viral warts. Data pooled from six randomised trials gave a cure rate of 75% in cases compared with 48% in controls (odds ratio 3.91, 95% confidence interval 2.40 to 6.36).11,13 Preparations containing salicylic acid include creams, ointments, paints, gels, and colloids, with concentrations of the active ingredient varying from 11% to 50%. Salicylic acid breaks down hyperkeratotic skin but does irritate children's skin. Topical salicylic acid should be regarded as first line treatment.

Cryotherapy

Systematic reviews show that cryotherapy is no better than topical salicylic acid.11,13 Cryotherapy is best avoided in young children, as parents consider the side effects of pain, swelling, and blistering excessive for a benign self limiting condition. Aggressive cryotherapy scars children's skin.

Other treatments

Although silver nitrate pencils and glutaraldehyde and formaldehyde preparations are licensed in the United Kingdom for treating warts, there is currently insufficient evidence of their benefit. Intralesional bleomycin, topical immunotherapy, photodynamic therapy, and pulsed dye laser treatment are best confined to research centres or resistant cases.

Impetigo

Cutaneous staphylococcal and streptococcal infections are important in children. They cause a wide spectrum of illness depending on the site of infection, the organism, and the host's immunity.14 Impetigo is a superficial skin infection characterised by golden crusts (fig 3). It is caused by Staphylococcus aureus or Streptococcus pyogenes.

Fig 3.

Impetigo, showing classic golden coloured crust

Credit: DOIA

Impetigo is the third most common skin disease in children, after dermatitis and viral warts, with a peak incidence at 2-6 years of age.15,16 Lesions are highly contagious and can spread rapidly by direct contact, through a family, nursery, or class.17 The condition is more common in children with atopic dermatitis, in those living in tropical climates, and in conditions of overcrowding and poor hygiene. Nasal carriage of organisms may predispose to recurrent infection in an individual.

Impetigo can occur either as a primary infection or secondary to another condition, such as atopic dermatitis or scabies, which disrupts the skin barrier. It can be classified clinically as impetigo contagiosa (non-bullous impetigo) or bullous impetigo. Impetigo contagiosa is caused by S aureus or S pyogenes. Bullous impetigo is invariably caused by toxin-producing S aureus.

Impetigo contagiosa

Impetigo contagiosa is the most common form of impetigo. Lesions begin as vesicles or pustules that rapidly evolve into gold-crusted plaques, often 2 cm in diameter. They usually affect the face and extremities and heal without scarring. Constitutional symptoms are absent. Satellite lesions may occur due to autoinoculation.

Bullous impetigo

Bullous impetigo is characterised by flaccid, fluid filled vesicles and blisters (bullae). These are painful, spread rapidly, and produce systemic symptoms. Lesions are often multiple, particularly around the oronasal orifices, and grouped in body folds. To confirm the diagnosis and to target treatment, Gram's stain, culture, and sensitivity testing should be carried out on the exudate from lesions.

Treatment

Treatments for impetigo include topical and systemic antibiotics and topical antiseptics.18 Good evidence shows that topical mupirocin and fusidic acid are safe and effective treatments for mild impetigo.18 In mild cases they are probably as effective as oral antibiotics.18 To minimise the development of resistant organisms, use topical antibiotics that are available in cream form only, which are not available as systemic preparations.

Oral antibiotics

Oral antibiotics may be better than topical preparations for more serious or extensive disease; they are easier to use but have more side effects than topical agents. Flucloxacillin is considered the treatment of choice for impetigo.19 Macrolides, cephalosporins, and coamoxiclav are also reported to be effective, but evidence is limited because the studies have not been performed.18 Selection of systemic antibiotic is determined by factors such as local epidemiology of resistance, patients' allergy or intolerance, and proved bacterial sensitivity after microbiological assessment.

If oral antibiotics are needed, we recommend as first line treatment a seven day course of flucloxacillin. In cases of allergy to penicillin, erythromycin (or similar macrolide) is suitable, but in some patients this causes gastrointestinal disturbance, and resistance to erythromycin is increasing. For impetigo caused by erythromycin resistant organisms, cephalosporins such as cephalexin are effective, although 10% of patients who are sensitive to penicillin are also sensitive to cephalosporins. Coamoxiclav (amoxicillin and clavulanic acid) is effective in infections caused by β lactamase producing strains of S aureus. Bacteriological culture is important before changing to this drug.

Topical antiseptics

Although no clear evidence supports the role of topical antiseptics in impetigo, they do help to soften crusts and clear exudate in mild disease. In more severe cases they may be a useful adjunct to antibiotics.

We suggest using topical mupirocin or fusidic acid for seven days in clinically mild impetigo. Oral antibiotics should be reserved for recalcitrant, extensive, systemic disease.

Tinea capitis (scalp ringworm)

Tinea capitis (scalp ringworm) is a highly contagious infection of the scalp and hair caused by dermatophyte fungi. It occurs in all age groups, but predominately children. It is endemic in some of the poorest countries.20 The commonest cause of tinea capitis worldwide is Microsporum canis.21

The epidemiology of tinea capitis in the United Kingdom has recently changed dramatically,22 reflecting a similar trend in the United States 20 years ago.23 In the United Kingdom it is becoming a major public health problem, and Afro-Caribbean children are particularly affected.24 The predominant organism was M canis, but now Trichophyton tonsurans causes 90% of cases in the United Kingdom and the United States.22 T tonsurans is an anthropophilic fungus, which spreads from person to person. The reason for this change is unclear, but hairdressing practices such as shaving the scalp, plaiting, and using hair oils may increase spread.22

Tinea capitis causes patchy alopecia, but specific clinical patterns can be varied. Six main patterns are recognised (box 2).25

Box 2: Main patterns of tinea capitis, listed according to occurrence (commonest first)

Grey type—circular patches of alopecia with marked scaling (fig 4)

Moth eaten—patchy alopecia with generalised scale

Kerion—boggy tumour studded with pustules; lymphadenopathy usually present (fig 5)

Black dot—patches of alopecia with broken hairs stubs

Diffuse scale—widespread scaling giving dandruff-like appearance

Pustular type—alopecia with scattered pustules; lymphadenopathy usually present

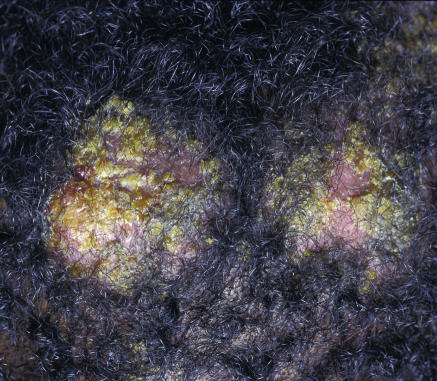

Fig 4.

Grey type tinea capitis, with inflammation, erythema, scaling, pustules, and crusting

Fig 5.

Kerion pattern of tinea capitis, showing large boggy nodules with superficial pustules and crusting

Additional educational resources

Review articles

Gibbs S, Harvey I, Sterling J, Stark R. Local treatments for cutaneous warts: systematic review. BMJ 2002,325: 461

Fuller LC, Child FJ, Midgley G, Higgins EM. Diagnosis and management of scalp ringworm. BMJ 2003;326: 539-41

George A, Rubin G. A systematic review and meta-analysis of treatments for impetigo. Br J Gen Pract 2003;53: 480-7

Clinical references

Harper J, Oranje A, Prose N, eds. Textbook of pediatric dermatology. Oxford: Blackwell, 2000—Prime chapters on cutaneous infections of childhood

Kane K, Ryder JB, Johnson RA, Baden HP, Stratigos A. Color atlas and synopsis of pediatric dermatology. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002—Excellent picture book aid to paediatric dermatology

Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, Austen KF, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, eds. Fitzpatrick's dermatology in general medicine. 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2004—Flagship textbook with excellent chapters on cutaneous infections

Williams H, Bigby M, Diepgen T, Herxheimer A, Naldi L, Rzany B. Evidence-based dermatology. London: BMJ Publishing Group, 2003—Review of evidence based treatment of skin disease

Useful websites

British Association of Dermatologists (www.bad.org.uk/doctors/guidelines/)—Information and guidelines on management of common skin disease

NHS National Electronic Library for Health (www.nelh.nhs.uk/cochrane.asp)—Details of evidence based medicine and research methods, with up to date information on evidence based treatment of skin disease (http://rms.nelh.nhs.uk/guidelinesfinder/) gives details of over 800 UK national guidelines and is updated weekly

Centers for Disease Control (www.cdc.gov/ncidod/hip/Aresist/mrsa.htm)—Up to date information from the United States, featuring fact sheets, frequently asked questions, and practical steps to control infection

Information for patients

British Association of Dermatologists (www.bad.org.uk/patients/)—Contains information on the skin and how it works, as well as skin diseases lp;&3qmerican Academy of Dermatology (www.aad.org/pamphlets/index.html)—Contains patient information

Skin Care Campaign (www.skincarecampaign.org/)—An umbrella organisation representing the interests of all people with skin diseases in the United Kingdom

UKs' Gateway to High Quality Internet Resources (omni.ac.uk/)—Free access to a searchable catalogue of internet sites covering health and medicine

Dermatology.co.uk (www.dermatology.co.uk/index.asp)—Educational resource for skin conditions and their treatment

The differential diagnosis for tinea capitis includes seborrhoeic dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, alopecia areata, and alopecia folliculitis. Tinea capitis should be considered in every child with a scaly scalp because the infection is common and the presentation diverse. Only 7% of children receive appropriate treatment for tinea capitis before referral to dermatology practice.25

Treatment

If tinea capitis is suspected, specimens of hair and scale should be examined to confirm the diagnosis. The aim of treatment is to provide a quick clinical and mycological cure, with minimal adverse effects and spread of disease. This requires oral antifungal agents, although topical treatment may reduce the risk of transmission at the start of systemic therapy.

Griseofulvin is the only treatment for tinea capitis licensed in the United Kingdom. It has been the treatment of choice for 40 years, with good evidence of efficacy in infections caused by T tonsurans and M canis.26-28 The recommended dose in children is 10 mg/kg/day, although some authors advocate up to 25 mg/kg/day. Treatment is taken until clinical and mycological cure is documented, usually about eight weeks. Side effects include nausea and rashes (about 10%); griseofulvin is contraindicated in pregnancy.

Good evidence supports the use of terbinafine for treating tinea capitis caused by T tonsurans26-28; it may be less effective for M canis. The dose ranges between 3 and 6 mg/kg/day, given for four weeks. Side effects include gastrointestinal upset and rashes (about 5%). Itraconazole, fluconazole, and ketoconazole are reported to be effective in tinea capitis, but there is less supportive evidence.

We thank Julie Sladden for reading and reviewing the manuscript.

Contributors: MJS and GAJ contributed equally to the academic content of this review. Both will act as guarantors for the paper.

Competing interests: MJS has been coinvestigator in trials sponsored by Merck, Sharp, and Dohme; this included speaker's honorariums and travel expenses. GAJ has received speakers' honorariums and travel expenses from Galderma, UCB Pharma, Shire, Leo, and Steifel. He has acted as a consultant to Novartis in a peer review of drug trial protocols. He has been coinvestigator in a trial sponsored by 3M Pharmaceuticals.

References

- 1.Hayden GF. Skin diseases encountered in a pediatric clinic. A one-year prospective study. Am J Dis Childhood 1985;139: 36-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tunnessen WW. A survey of skin disorders seen in pediatric general and dermatology clinics. Pediatr Dermatol 1984;1: 219-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Findlay GH, Vismer HF, Sophianos T. The spectrum of pediatric dermatology. Analysis 10,000 cases. Br J Dermatol 1974;91: 379-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rogers M, Barnetson RSC. Diseases of the skin. In: Campbell AGM, McIntosh N, eds. Forfar and Arneil's textbook of pediatrics. 5 th ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1998: 1633-5.

- 5.Koning S, Bruijnzeels MA, van Suijlekom-Smit LWA, van der Wouden JC. Molluscum contagiosum in Dutch general practice. Br J Gen Pract 1994;44: 417-9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weller R, O'Callaghan CJ, MacSween RM, White MI. Scarring in molluscum contagiosum: comparison of physical expression and phenol ablation. BMJ 1999;319: 1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van der Wouden JC, Gajadin S, Berger MY, Butler CC, Koning S, Menke J, et al. Interventions for molluscum contagiosum in children. Cochrane Library: 2004, Issue 2. Chichester: Wiley.

- 8.Ormerod AD, White MI, Shah SA, Benjamin N. Molluscum contagiosum effectively treated with a topical acidified nitrite, nitric oxide liberating cream. Br J Dermatol 1999;141; 1051-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bayerl C, Feller G, Goerdt S. Experience in treating molluscum contagiosum in children with imiquimod 5% cream. Br J Dermatol 2003;149(suppl): 25-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sterling JC, Kurtz JB. Viral infections. In: Champion RH, Burton JL, Burns DA, Breathnach SM, eds. Rook textbook of dermatology. 6th ed. Oxford: Blackwell, 1998.

- 11.Gibbs S, Harvey I, Sterling JC, Stark R. Local treatments for cutaneous warts. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003;(3): CD001781. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Williams HC, Pottier A, Strachan D. The descriptive epidemiology of warts in British schoolchildren. Br J Dermatol 1993;128: 504-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gibbs S, Harvey I, Sterling J, Stark R. Local treatments for cutaneous warts: systematic review. BMJ 2002;325: 461. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Resnick S. Staphylococcal and streptococcal skin infections: pyodermas and toxin-mediated syndromes. In: Harper JO, A. Prose N, eds. Textbook of pediatric dermatology. Oxford: Blackwell, 2000: 369-77.

- 15.Dagan R. Impetigo in childhood: changing epidemiology and new treatments. Ped Annals 1993;22: 235-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bruijnzeels MA, van Suijlekom-Smit LWA, van der Velden J, van der Wouden JC. The child in general practice. Dutch national survey of morbidity and interventions in general practice. Rotterdam: Erasmus University Rotterdam, 1993.

- 17.Hlady WG, Middaugh JP. An epidemic of bullous impetigo in a newborn nursery due to Staphylococcus aureus: epidemiology and control measures. Alaska Med 1986;28: 99-103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koning S, Verhagen AP, van Suijlekom-Smit LWA, Morris A, Butler CC, van der Wouden JC. Interventions for impetigo. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;2: CD003261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feingold DS. Staphylococcal and streptococcal pyodermas. Semin Dermatol 1993;12: 331-5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.González U, Seaton T, Bergus G, Torres JM, Jacobson J. Systemic antifungal therapy for tinea capitis in children. Cochrane Library, 2004: Issue 2. Chichester: Wiley. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Aly R. Ecology and epidemiology of dermatophyte infections. J Am Acad Dermatol 1994;31: S21-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Higgins EM, Fuller LC, Smith CH. Guidelines for the management of tinea capitis. Br J Dermatol 2000;143: 53-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bronson DM, Desai DR, Barskey S. An epidemic of infection with Trichophyton tonsurans revealed in a twenty year survey of fungal pathogens in Chicago. J Am Acad Dermatol 1983;8: 322-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fuller LC, Child FJ, Midgley G, Higgins EM. Diagnosis and management of scalp ringworm. BMJ 2003;326: 539-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fuller LC, Child FC, Midgley G, Higgins EM. Scalp ringworm in south-east London and an analysis of a cohort of patients from a paediatric dermatology department. Br J Dermatol 2003;148: 985-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caceres-Rios H, Rueda M, Ballona R, Bustamante B. Comparison of terbinafine and griseofulvin in the treatment of tinea capitis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000;42: 80-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fuller LC, Smith CH, Cerio R, Marsden RA, Midgley G, Beard AL, et al. A randomized comparison of 4 weeks of terbinafine vs. 8 weeks of griseofulvin for the treatment of tinea capitis. Br J Dermatol 2001;144: 321-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gupta AK, Adam P, Dlova N, Lynde CW, Hofstader S, Morar N, et al. Therapeutic options for the treatment of tinea capitis caused by Trichophyton species: griseofulvin versus the new oral antifungal agents, terbinafine, itraconazole, and fluconazole. Pediatr Dermatol 2001;18: 433-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]