The Arabidopsis transcription factor NAC016 activates drought stress responses by inducing NAP transcription and repressing AREB1 transcription by binding to different regions of the AREB1 promoter.

Abstract

Drought and other abiotic stresses negatively affect plant growth and development and thus reduce productivity. The plant-specific NAM/ATAF1/2/CUC2 (NAC) transcription factors have important roles in abiotic stress-responsive signaling. Here, we show that Arabidopsis thaliana NAC016 is involved in drought stress responses; nac016 mutants have high drought tolerance, and NAC016-overexpressing (NAC016-OX) plants have low drought tolerance. Using genome-wide gene expression microarray analysis and MEME motif searches, we identified the NAC016-specific binding motif (NAC16BM), GATTGGAT[AT]CA, in the promoters of genes downregulated in nac016-1 mutants. The NAC16BM sequence does not contain the core NAC binding motif CACG (or its reverse complement CGTG). NAC016 directly binds to the NAC16BM in the promoter of ABSCISIC ACID-RESPONSIVE ELEMENT BINDING PROTEIN1 (AREB1), which encodes a central transcription factor in the stress-responsive abscisic acid signaling pathway and represses AREB1 transcription. We found that knockout mutants of the NAC016 target gene NAC-LIKE, ACTIVATED BY AP3/PI (NAP) also exhibited strong drought tolerance; moreover, NAP binds to the AREB1 promoter and suppresses AREB1 transcription. Taking these results together, we propose that a trifurcate feed-forward pathway involving NAC016, NAP, and AREB1 functions in the drought stress response, in addition to affecting leaf senescence in Arabidopsis.

INTRODUCTION

Drought stress, or water deficit, affects plant growth and can have devastating effects on crop production (Boyer, 1982). Thus, plant breeding to develop drought-tolerant crop plants has emerged as one of the most urgent aims for modern agriculture. Plants have some adaptations to survive water deficit; for example, drought stress triggers the accumulation of the phytohormone abscisic acid (ABA), and some metabolites, including sugar derivatives (ononitol and pinitol) and amino acids (proline and glutamine), for acclimation to drought conditions (Bianchi et al., 1991; Ramanjulu and Sudhakar, 1997; Streeter et al., 2001). Understanding the mechanisms of these adaptations can inform plant breeding approaches. Moreover, drought stress leads to dynamic changes in the expression of drought stress-related genes (Shinozaki and Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, 2007). Thus, identification and functional analysis of drought-responsive genes may help plant breeders to develop drought-tolerant plants (Liu et al., 1998; Fujita et al., 2005).

The NAC (for NAM/ATAF1/2/CUC2) genes encode plant-specific transcription factors (TFs) (Riechmann et al., 2000) and are one of the largest TF families in plants, with 106 NAC genes in Arabidopsis thaliana and 149 in rice (Oryza sativa) (Gong et al., 2004; Xiong et al., 2005). Consistent with their TF functions, the NAC family members commonly harbor a highly conserved DNA binding domain at their N termini (Aida et al., 1997; Ernst et al., 2004). However, NAC family members have different C-terminal regions, suggesting that the C-terminal regions may have critical roles in determining the specific cis-elements that they recognize in their respective target genes (Tran et al., 2010). Furthermore, some NAC TFs contain a transmembrane domain (TMD) in the C-terminal region, which may determine their subcellular localization and conditional TF activity (Seo et al., 2008, 2010).

NAC TFs function in multiple developmental processes, including embryo and shoot meristem development (Souer et al., 1996), lateral root formation (Xie et al., 2000), auxin signaling (Xie et al., 2000), defense (Ren et al., 2000), and leaf senescence (Guo and Gan, 2006; Kim et al., 2009). Recent work also revealed that some NAC TFs function in abiotic stress-responsive signaling, and the molecular mechanisms of this have been extensively studied in Arabidopsis. For instance, ORESARA1 (ORE1) promotes senescence in Arabidopsis (Kim et al., 2009). Also, ore1 mutants are tolerant to high salinity stress, indicating that ORE1 acts as a positive regulator of salt stress-responsive signaling (Balazadeh et al., 2010). In contrast with ORE1, JUNGBRUNNEN1 (JUB1) negatively regulates salt stress-responsive signaling; JUB1-overexpressing (JUB1-OX) plants exhibit a salt-tolerant phenotype, and jub1 knockout mutants are hypersensitive to salt and heat stresses (Wu et al., 2012; Shahnejat-Bushehri et al., 2012). JUB1 directly regulates the expression of DEHYDRATION RESPONSIVE ELEMENT BINDING 2A (DREB2A), which is required for the expression of many other water stress-inducible genes (Sakuma et al., 2006a, 2006b). ORE1 and JUB1 were originally identified as senescence-associated NACs (senNACs); thus, the signals for senescence and abiotic stress responses appear to interact through the coordination of the activities of several senNAC TFs.

In addition to the roles for NAC TFs in other abiotic stresses and senescence, work in Arabidopsis indicated that several NAC TFs affect drought stress responses. For example, NAC019-, NAC055-, and NAC072-OX plants exhibit strong drought tolerance, indicating that these NAC TFs negatively regulate drought stress-responsive signaling (Fujita et al., 2004; Tran et al., 2004). The NAC TFs that contain a C-terminal TMD, NTL6 (NTL for NAC with transmembrane motif 1-like) and NTL4, also function in drought stress signaling. Indeed, NTL6-OX plants and ntl4 null mutants exhibit drought tolerance (Kim et al., 2012; Lee and Park, 2012), indicating that the functions of NTL4 and NTL6 counteract each other in drought stress-responsive signaling. Notably, their C-terminal TMDs conditionally regulate the TF activities of these two NTLs; under water deficit conditions, cleavage of their TMDs allows NTL6 and NTL4 to translocate from the cytoplasm to the nucleus (Kim et al., 2010; Lee and Park, 2012).

Identification of NAC target genes will lead to a deeper understanding of the dual functions of NAC TFs in stress and developmental signaling pathways (Bu et al., 2008; Jensen et al., 2010; Hickman et al., 2013). Recently, Xu et al. (2013) found that NAC096 is associated with the drought stress response and NAC096 specifically binds to the ABA-responsive element in the promoters of several drought stress-responsive genes (Fujita et al., 2005; Xu et al., 2013). Several basic leucine zipper protein (bZIP)-type TFs, such as ABF2 (ABRE binding factor 2) and ABF4, also bind to the ABA-responsive element, indicating that both NAC096 and bZIP-type TFs share target genes and that their transactivation functions are somewhat redundant. Previously, we identified Arabidopsis NAC016 as a senescence-induced TF (Kim et al., 2013). Under senescence-promoting conditions, nac016 mutants exhibit a delayed senescence phenotype and, conversely, NAC016-OX plants senesce rapidly, indicating that NAC016 promotes leaf senescence. By yeast one-hybrid assays, we found that NAC016 can bind to the promoter of NAP, which also encodes a senNAC TF (Guo and Gan, 2006). The stay-green nac016 and nap mutants also have significant tolerance to salt and oxidative stresses.

Here, we show new evidence indicating that NAC016 also functions to promote drought stress responses in Arabidopsis; we also identify the mechanisms by which NAC016 affects drought-responsive signaling. We identified the NAC016-specific binding motif (termed NAC016BM), which does not contain the previously defined core sequence of the NAC binding motif. NAC016 binds to the NAC16BM in the promoter of ABA-RESPONSIVE ELEMENT BINDING PROTEIN1 (AREB1), a key negative regulator of stress-responsive ABA signaling (Fujita et al., 2005), to downregulate AREB1 expression. Moreover, the NAC016 target gene NAP also mediates drought stress-responsive signaling by directly binding to the AREB1 promoter and downregulating its transcription. Based on our results, we propose a trifurcate feed-forward regulatory model involving NAC016, NAP, and AREB1.

RESULTS

Arabidopsis nac016 Mutants Tolerate Drought Stress

Recently, we showed that the Arabidopsis nac016 mutants exhibit a functional stay-green phenotype during senescence (dark-induced and natural) and also have increased tolerance to salt and oxidative stresses (Kim et al., 2013). Since several loss-of-function mutants or constitutively overexpressing (OX) lines of senNACs show significant tolerance to several abiotic stresses (Balazadeh et al., 2010; Wu et al., 2012), we speculated that nac016 mutants likely have significant tolerance to other abiotic stresses. To test this, we first examined the expression levels of NAC016 in the wild type under different abiotic stress conditions, such as dehydration, cold (4°C, 0 to 4 d), and heat (40°C, 0 to 12 h) treatments. We found that, of the stresses tested, dehydration caused rapid increase of NAC016 expression (Figure 1 A), indicating that NAC016 function is associated with drought stress responses, in addition to its previously reported roles in leaf senescence and salt stress responses (Kim et al., 2013). By contrast, cold and heat treatments did not alter NAC016 expression (Supplemental Figure 1).

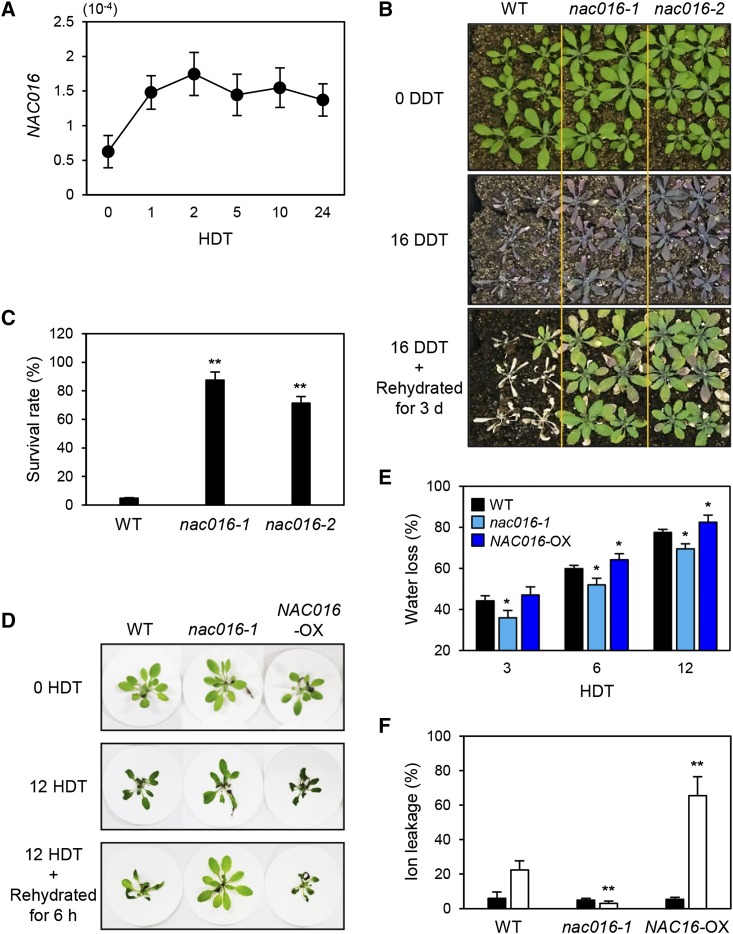

Figure 1.

NAC016 Promotes the Drought Stress Response.

(A) NAC016 expression increases rapidly under drought stress conditions. Three-week-old wild-type plants grown on soil at 22 to 24°C under LD (16 h light/8 h dark) conditions ([B], top panel) were dehydrated on dry filter paper (see [D]), and the rosette leaves were sampled at 0, 1, 2, 5, 10, and 24 HDT. For RT-qPCR, relative expression levels of NAC016 were obtained by normalizing to the mRNA levels of GAPDH (AT1G16300). Mean and sd were obtained from more than three biological replicates.

(B) and (C) Drought tolerance phenotype (B) and survival rate (C) of nac016-1 and nac016-2 mutants on soil. Three-week-old plants (upper panel) were dehydrated for 16 d (middle panel) and then rehydrated for 3 d (lower panel). DDT represents day(s) of dry treatment. Plants were grown on the soil at 22 to 24°C under cool-white fluorescent light (90 to 100 μmol m−2 s−1) under LD (16 h light/8 h dark) conditions. In (C), mean and sd of survival rates were obtained from three replications with 30 plants each

(D) to (F) Drought tolerance assays on dry filter paper.

(D) The 3-week-old plants were placed on dry filter paper (upper panel), dehydrated for 12 h (middle panel), and then rehydrated for 6 h (lower panel).

(E) Water loss rate. Black, green, and brown bars represent wild-type, nac016-1, and NAC016-OX plants, respectively.

(F) Black and white bars indicate 0 and 12 HDT, respectively. Mean and sd ([E] and [F]) were obtained from more than five biological replicates. These experiments were repeated at least three times with similar results. Asterisks ([C], [E], and [F]) indicate significant differences between the wild type and nac016-1 or NAC016-OX (Student’s t test P values, *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01).

We next examined whether nac016 mutants or NAC016-OX plants display tolerant or susceptible phenotypes under drought stress conditions. When 3-week-old wild-type, nac016, and NAC016-OX plants were dehydrated for 14 d, we found that both nac016-1 and nac016-2 mutants (Kim et al., 2013) exhibited strong drought tolerance (Figure 1B), while wild-type and NAC016-OX plants showed severe wilting symptoms (Supplemental Figure 2A). At 3 d after rehydration, almost all wild-type and NAC016-OX plants did not recover, while nac016-1 mutants recovered rapidly (Supplemental Figure 2B). After recovery, ∼90% of nac016-1 mutants survived, in contrast to only 18% of wild-type and 9% of NAC016-OX plants (Figure C; Supplemental Figure 2 B). To examine the effect of nac016 mutation on drought tolerance in more detail, we transferred wild-type, nac016-1, and NAC016-OX plants to dry filter paper. After 12 h of dry treatment (HDT), wild-type and NAC016-OX plants were almost completely wilted, while nac016-1 mutants showed little or no wilting (Figure 1D). Consistent with the visible phenotypes, nac016-1 leaves showed significantly lower water loss and ion leakage rates, compared with wild-type leaves (Figures 1E and 1F). While NAC016-OX and wild-type plants have similar sensitivities to drought stress, the NAC016-OX leaves had significantly higher ion leakage rates than wild-type leaves (Figure 1F), indicating that NAC016-OX plants are more sensitive to dehydration than the wild type.

Some drought-tolerant plants are hypersensitive to ABA (Fujita et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2012). To investigate the ABA sensitivity of nac016-1 mutants, we measured the stomatal aperture in the 10-d-old wild-type and nac016-1 leaves in the presence of ABA (10 μM). After 3 h of ABA treatment, stomatal aperture of nac016-1 leaves decreased much more than that of wild-type leaves (Supplemental Figure 3), suggesting that drought tolerance of nac016-1 mutants could be attributed to increased sensitivity to ABA.

Conditional Nuclear Localization of NAC016 by Cleavage of the C-terminal TMD under Drought Stress or Prolonged Darkness

NAC016 contains a C-terminal TMD (Kim et al., 2013), and the C-terminal TMD determines the subcellular localization of other NACs (Lee and Park, 2012; De Clercq et al., 2013; Ng et al., 2013). Thus, to examine whether the C-terminal TMD of NAC016 controls its conditional nuclear localization, we prepared transgenic plants expressing the full-length NAC016 (N16) or NAC016 without the TMD (N16△C). We tagged these proteins with green fluorescent protein (GFP) at the N terminus and termed the constructs GFP-N16 and GFP-N16△C, respectively (see Methods) (Figure 2A). We generated transgenic plants, used reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) to measure the expression levels of NAC016 in four independent lines for each construct (GFP-N16 and GFP-N16△C), and selected the lines showing the highest expression for each transgene (Supplemental Figure 4). We next used subcellular fractionation to examine the subcellular localization of GFP-N16 and GFP-N16△C proteins under normal conditions. GFP-N16△C was present only in the nuclear protein fractions, whereas GFP-N16 was found only in cytoplasmic protein fractions (Figure 2B), strongly indicating that the C-terminal TMD regulates the spatiotemporal localization of the NAC016 TF.

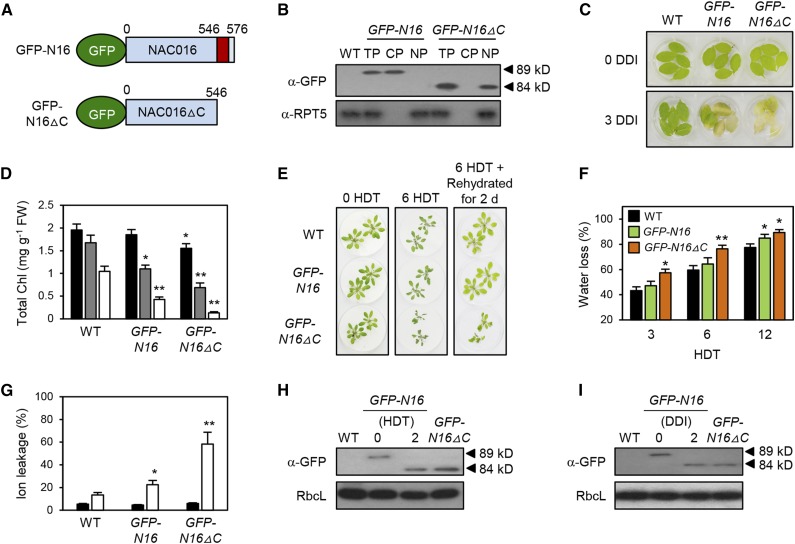

Figure 2.

Cleavage of the C-Terminal TMD Determines Conditional NAC016TF Activity.

(A) The protein structures of the N-terminal GFP-tagged NAC016 (hereafter GFP-N16) and C-terminal TMD-deleted NAC016 (hereafter GFP-N16△C).

(B) Subcellular localization of GFP-N16 and GFP-N16△C proteins. Total protein was extracted from the leaves of 2-week-old GFP-N16 and GFP-N16△C plants grown on soil under normal conditions and separated with a nuclear protein extraction kit (see Methods). The total protein fraction (TP), cytoplasmic protein fraction (CP), and nuclear protein fraction (NP) were subjected to SDS-PAGE.

(C) and (D) Changes in color (C) and total chlorophyll (Chl) levels (D) of rosette leaves detached from the 3-week-old plants during dark-induced senescence. Black, gray, and white bars in (D) indicate 0, 2, and 3 DDI, respectively. FW, fresh weight.

(E) to (G) Drought tolerance assays on dry filter paper. Drought stress tolerance of wild-type, GFP-N16, and GFP-N16△C plants was examined by phenotype (E), water loss rate (F), and ion leakage rate (G). These experiments were repeated three times with similar results for (C) to (G).

(F) Black, green, and brown bars indicate the wild type, GFP-N16, and GFP-N16△C, respectively.

(G) Black and white bars indicate 0 and 6 HDT, respectively.

In (D), (F), and (G) Mean and sd were obtained from more than five biological replicates. Asterisks indicate significant differences between the wild type and GFP-N16 or GFP-N16△C (Student’s t test P values, *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01).

(H) and (I) The C-terminal TMD of NAC016 is cleaved in response to drought stress (H) and extended darkness (I).

(B), (H), and (I) GFP-N16, GFP-N16△C, RbcL (loading control), and RPT5 (loading control) were immunodetected by their respective antibodies (see Methods). These experiments were repeated twice with the same results.

In the NAC TFs that contain a TMD, cleavage of the TMD allows the NAC to translocate to the nucleus; thus, we predicted that the N16△C construct might cause the activation of NAC016-dependent responses. To test this, we examined the phenotypes of the transgenic plants. First, we examined the phenotype of the transgenic plants during dark-induced senescence as well as under drought stress. After 3 d of dark incubation (DDI), the detached leaves of 3-week-old GFP-N16 plants turned yellow faster (Figure 2C), with lower levels of total chlorophyll (Figure 2D) compared with the wild type. Interestingly, before dark incubation, the intact leaves of GFP-N16△C plants showed a slightly pale green color, with lower levels of total chlorophyll than those of wild-type and GFP-N16 plants (see black bars), and the detached leaves of GFP-N16△C plants turned yellow much faster than those of GFP-N16 plants in darkness (see gray and white bars) (Figures 2C and 2D). We thus checked the expression of several senescence-associated genes (SAGs), including NON-YELLOW COLORING1 (Kusaba et al., 2007), WRKY22 (Zhou et al., 2011), ORE1 (Kim et al., 2009), and NAP (Guo and Gan, 2006), and found that these four SAGs were already upregulated in the presenescent leaves of GFP-N16△C plants (Supplemental Figure 5), thus causing the slightly pale-green leaf color under normal growth conditions. GFP-N16△C plants also showed more sensitivity to drought stress than GFP-N16 plants (Figure 2E), with higher water loss (Figure 2F) and ion leakage rates (Figure 2G).

We subsequently examined whether dark incubation or water stress can induce the cleavage of the C-terminal TMD of NAC016. We confirmed the accumulation of constitutively expressed GFP-N16 and GFP-N16△C proteins, identified by their respective molecular weights (MWs), in the leaf tissues under normal conditions (Figures 2H and 2I). After 2 HDT or 2 DDI, the MW of GFP-N16 proteins was reduced to a MW similar to that of GFP-N16△C proteins, demonstrating that the C-terminal TMD was cleaved in response to the signals of prolonged darkness and drought stress.

Genes Differentially Expressed in nac016-1 Mutants under Drought Stress

To examine the regulatory network of NAC016-mediated drought stress-responsive signaling, we conducted a genome-wide microarray analysis to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between the wild type and nac016-1. Three-week-old wild-type and nac016-1 whole plants grown on soil were transferred to and dehydrated on dry filter paper for 2 h (2 HDT) and then the rosette leaves were sampled for microarray analysis (Figure 3A). We identified 40 and 33 genes that were significantly upregulated at 0 and 2 HDT, respectively (nac016-1/WT; >2-fold), and 55 and 64 genes that were downregulated (nac016-1/WT; < 2-fold) (Figures 3B and 3C). The up- and downregulated genes included in the Venn diagrams are listed in Supplemental Tables 1 to 4.

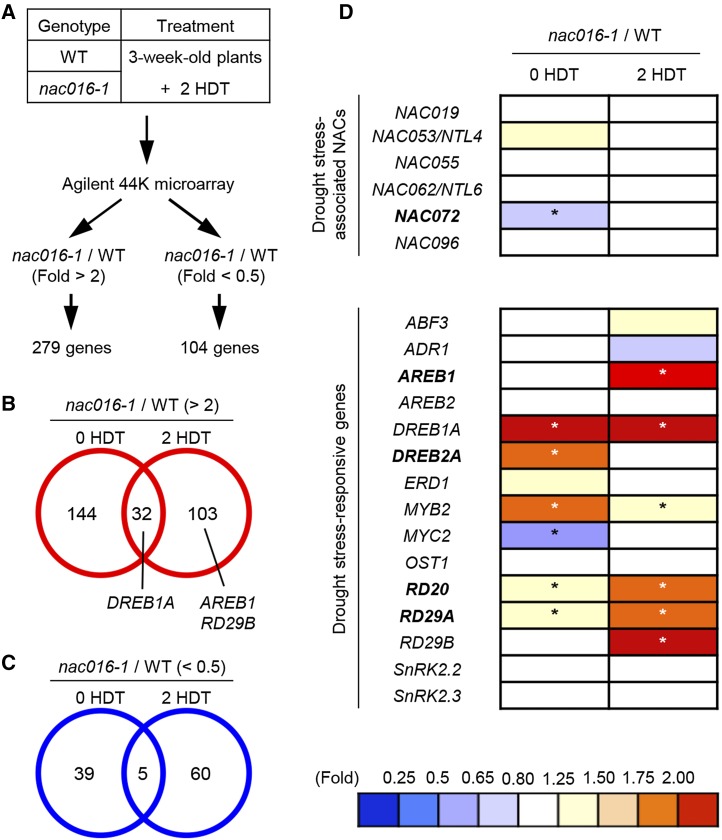

Figure 3.

Differential Expression of Drought Stress-Related Genes in nac016-1 Mutants.

(A) A summary of the microarray analysis (see Methods). A filter for Student t test P value of <0.05 was applied to DEGs.

(B) and (C) Venn diagrams of the number of DEGs in nac016-1 mutants compared with the wild type. The numbers of upregulated (B) and downregulated (C) genes in nac016-1 at 0 and 2 HDT mutants are shown.

(D) The relative expression (nac016-1/WT) of known drought stress-associated genes at 0 and 2 HDT are illustrated. Relative expression value was normalized to the wild type. Asterisks in each column indicate significant differences between wild-type and nac016-1 plants (Student’s t test P value, *P < 0.05). HDT indicates hour(s) of dry treatment.

To date, more than 20 drought stress-responsive genes have been characterized in Arabidopsis (Valliyodan and Nguyen, 2006; Tran et al., 2007; Xu et al., 2013). Thus, we subsequently examined whether these drought stress-responsive genes are differentially expressed in nac016-1 compared with the wild type (nac016-1/WT) at 2 HDT. Our analysis included six drought stress-associated NAC genes (NAC019, NAC053/NTL4, NAC055, NAC064/NTL6, NAC072, and NAC096) and 15 other drought stress-responsive genes. We found that the expression levels of all the NAC genes examined did not significantly differ between nac016-1 mutants and the wild type (Figure 3D). However, several drought stress-responsive genes, including AREB1 (Fujita et al., 2005), DREB1 (Liu et al., 1998), and RESPONSIVE TO DESICCATION 29B (RD29B; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki and Shinozaki, 1994), were significantly upregulated, by more than 2-fold, in nac016-1 mutants at 2 HDT (Figure 3D). Thus, it seems that the altered expression of several key drought stress-responsive genes was associated with drought tolerance in nac016 mutants.

NAC016 Binds to a Unique Motif that Differs from the Core NAC Binding Motif

Previous work defined the 4-bp core sequence of the NAC binding motif as CACG (Olsen et al., 2005). Moreover, studies using binding motif analysis tools and promoter binding assays have identified the specific binding motifs of NAC TFs, and these assays indicate that each NAC TF likely has a specific and different binding motif (Olsen et al., 2005; Yabuta et al., 2010; Zhang and Gan, 2012; De Clercq et al., 2013). To find the specific binding motif for NAC016, we used the MEME motif discovery tool (http://meme-suite.org) (Bailey et al., 2006) and our microarray data; we identified an 11-bp consensus sequence, GATTGGAT[A/T]CA, present in 14 of the 15 genes most downregulated at 0 HDT in nac016-1 mutants (Figures 4A and 4B; Supplemental Figure 6 and Supplemental Table 2).

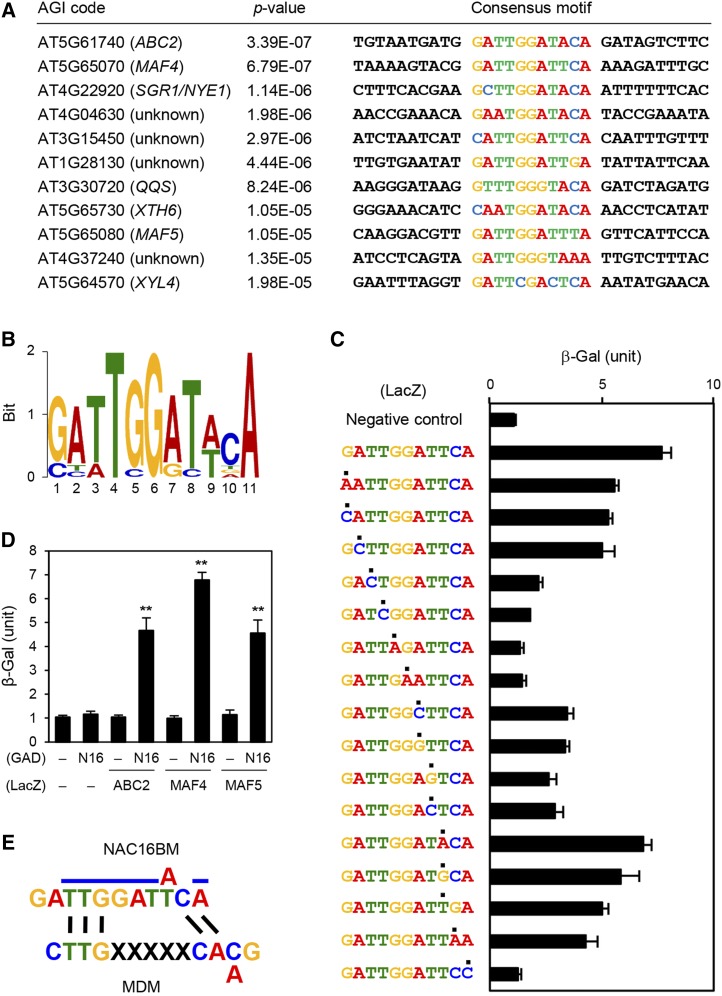

Figure 4.

Identification of the NAC016 Binding Motif (NAC016BM).

(A) and (B) Using MEME motif analysis, conserved sequences were found in the promoter regions of genes downregulated in nac016-1 mutants at 0 HDT (Supplemental Table 2).

(C) Interaction of NAC016 with the NAC16BM and its substituted sequences in yeast one-hybrid assays. The sequences of interest were fused to a promoter fragment of TUB2 that does not contain a NAC016BM. β-Galactosidase (β-Gal) activity was measured by liquid assays using CPRG (see Methods). Filled circles above the sequences indicate the substitution from NAC016BM, which was determined by MEME analysis (shown in [B]).

(D) Analysis of the binding affinity of NAC016 (N16) to the promoters of three candidate NAC016 targets (ABC2, MAF4, and MAF5), which contain the NAC16BM, using yeast one-hybrid assays. Relative β-Gal activity was measured by liquid assays using CPRG (see Methods). Empty bait and prey plasmids, denoted as minus (‒), were used for negative controls.

(C) and (D) Mean and sd of β-Gal unit (104 min−1 mL−1) were obtained from more than four independent colonies. Asterisks indicate significant differences (Student’s t test P values, *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01). These experiments were repeated three times with similar results.

(E) Comparison between the NAC16BM and the MDM. Blue solid lines indicate the core sequences of NAC16BM.

To examine which bases in this candidate sequence (hereafter termed NAC016BM) are vital, we performed point mutation analysis of NAC016BM and tested NAC016 binding to the mutated sequences by yeast one-hybrid assays. Based on the NAC016BM determined by MEME analysis (Figure 4C; GATTGGATTCA), we prepared a series of single-nucleotide substituted sequences and fused them to a DNA fragment of the TUBULIN BETA CHAIN2 (TUB2) promoter, which does not contain the NAC016BM. We first confirmed that NAC016 does not bind to the TUB2 promoter (Figure 4C, negative control). We found that point mutations in 3rd to 8th (TTGGAT) and 11th (A) of the NAC016BM significantly decreased the binding capacity of NAC016, and mutations of other nucleotides, such as 1st (G), 2nd (A), 9th (T), and 10th (C), did not significantly reduce the binding efficiency (Figure 4C), indicating that TTGGAT (3rd to 8th) and A (11th) bases are the core sequence of the NAC016BM and are essential for the DNA binding of NAC016.

We subsequently used yeast one-hybrid assays to examine the binding capacity of NAC016 to the NAC016BM-containing promoters of three genes that are downregulated in nac016-1 mutants, ATP BINDING CASSETTE2 (ABC2; At5g61740), MADS AFFECTING FLOWERING4 (MAF4; At5g65070), and MAF5 (AT5G65080), and have conserved core sequences of NAC016BM in their promoters (Figure 1A). We found that NAC016 has a significant binding affinity to these promoters (Figure 4D), strongly suggesting that NAC016 binds to the 11-bp NAC16BM consensus sequence and directly targets ABC2, MAF4, and MAF5. We also examined whether the core sequence of the NAC16BM exists in the promoters of other up- or downregulated genes. We found the core sequence of the NAC16BM in the promoters of four genes among the most upregulated genes at 0 HDT, four genes among the most upregulated 15 genes at 2 HDT, eight genes among the most downregulated 15 genes at 0 HDT, and five genes among the most downregulated 15 genes at 2 HDT (Supplemental Table 5). Interestingly, the NAC16BM has some sequence similarity to the mitochondrial dysfunction motif (MDM; De Clercq et al., 2013), which also serves as the binding site of many other TMD-containing NAC TFs (Figure 4E).

Examination of the other TMD-containing NACs showed that NAC053/NTL4 positively regulates H2O2-dependent drought stress responses and NAC017 negatively regulates these responses (Lee and Park, 2012; De Clercq et al., 2013). NTL4 activates its target genes by binding to the general NAC binding motif ([TA][TG][TAGC]CGT[GA]) (Olsen et al., 2005). NAC017 also binds to the core sequence of the NAC binding motif, CACG or CAAG (Ng et al., 2013). Our work showed that nac016-1 mutants have lower H2O2 levels and NAC016-OX plants have higher H2O2 levels under drought stress conditions (Supplemental Figure 7). To examine whether NAC016 also affects the NTL4- or NAC017-mediated drought-responsive signaling, we measured the expression levels of target genes of NTL4/NAC053 and NAC017, A. THALIANA RESPIRATORY BURST OXIDASE HOMOLOG C (AtrbohC) and ALTERNATIVE OXIDASE1a (AOX1a), in wild-type, nac016-1, and NAC016-OX plants under drought stress. However, expression of AtrbohC and AOX1a was not significantly altered in nac016-1 or NAC016-OX plants (Supplemental Figures 8A and 8B), and we could not find the NAC16BM sequence in the promoter regions of AtrbohC and AOX1a. This suggests that the drought stress-responsive signaling mediated by NAC016 does not include the core regulatory cascades of NTL4- and NAC017-mediated drought stress-responsive pathways.

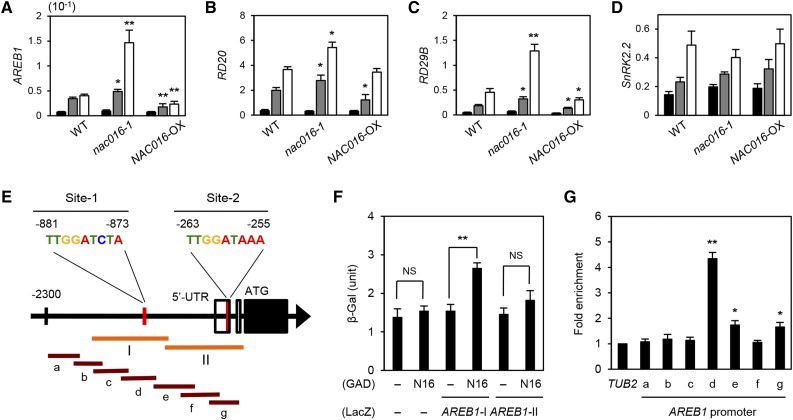

NAC016 Represses AREB1 Expression in Response to Drought Stress

The Arabidopsis AREB1 negatively regulates drought stress-responsive signaling, and AREB1-OX plants show a strong drought tolerance phenotype (Fujita et al., 2005), similar to nac016 mutants (Figure 1; Supplemental Figure 2). Our microarray data showed that AREB1 expression was significantly upregulated in nac016-1 mutants at 2 HDT (Figure 3D; Supplemental Table 3). Like the plant samples used in microarray analysis, 3-week-old wild-type, nac016-1, and NAC016-OX whole plants were dehydrated for 1 or 2 h on dry filter paper, and then the rosette leaves were sampled for RT-qPCR analysis. Consistent with the data from the microarray analysis, AREB1 expression was upregulated in nac016-1 mutants and downregulated in NAC016-OX plants (Figure 5A). We also checked the transcript levels of genes downstream and upstream of AREB1 in wild-type, nac016-1, and NAC016-OX plants before and after drought treatments. The transcript levels of RD29B and RD20, two direct target genes of AREB1 (Shinozaki and Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, 2007), were significantly upregulated in nac016-1 mutants and downregulated in NAC016-OX plants (Figures 5B and 5C). We further confirmed that the expression of AREB1, RD20, and RD29B was upregulated in nac016-1 mutants when they were dehydrated on soil (Supplemental Figures 9A to 9C). However, the nac016-1 and NAC016-OX plants showed no changes in the transcript levels of SnRK2.2, the drought- and ABA-induced gene that encodes a positive regulator of AREB1 expression (Fujita et al., 2009) (Figure 5D), indicating that NAC016 downregulates AREB1 expression independently of the upregulation of SnRK2.2 in response to drought stress.

Figure 5.

NAC016 Directly Binds to the AREB1 Promoter and Downregulates AREB1 Expression.

(A) to (D) Transcript levels of AREB1 (A), RD20 (B), RD29B (C), and SnRK2.2 (D) in wild-type, nac016-1, and NAC016-OX plants during drought stress. The 3-week-old whole plants were dehydrated on dry filter paper, and the rosette leaves were sampled at 0 (black bars), 1 (gray bars), and 2 (white bars) HDT. For RT-qPCR, the gene expression levels were obtained by normalizing to the transcript levels of GAPDH. Mean and sd were obtained from more than three biological replicates. Asterisks indicate significant differences between the wild type and nac016-1 or NAC016-OX (Student’s t test P values, *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01).

(E) Schematic diagram of the AREB1 promoter. Two red vertical lines indicate the possible NAC16BMs. Two orange horizontal lines indicate the bait sequences for yeast one-hybrid assay (I and II) in (C). Brown horizontal lines indicate the PCR amplicons for the ChIP assay (a to g).

(F) Analysis of the binding of NAC016 (N16) to the promoter regions of AREB1, AREB1-I, and AREB1-II in (E) using yeast one-hybrid assays. β-Gal activity was measured by liquid assay using CPRG. Empty bait and prey plasmids (−) were used for negative controls. Mean and sd of β-Gal activity (1 unit = 104 min−1 mL−1) were obtained from more than four independent colonies. Asterisks indicate significant differences (Student’s t test P value, **P < 0.01).

(G) NAC016 binding affinity to the AREB1 promoter regions in planta. Fold enrichment of the promoter fragments of AREB1 was measured by ChIP assay with an anti-GFP antibody (see Methods). Two-week-old wild-type and GFP-N16 plants at 2 HDT were used. TUB2 was used as a negative control. Mean and sd were obtained from more than three biological replicates. Asterisks indicate significant differences compared with TUB2 (Student’s t test P values, *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01). All experiments were repeated at least three times with similar results.

We identified two candidate NAC016 binding sites TTGGATCTA (−881 to −873: Site-1) and TTGGATAAA (−264 to −255; Site-2), in which the core sequence of NAC16BM is conserved, in the AREB1 promoter (Figure 5E). To examine whether NAC016 can bind to the two sites in the AREB1 promoter, we first performed yeast one-hybrid assays. These assays revealed that NAC016 binds to region I, including Site-1, but not to region II containing Site-2 (Figure 5F). We also used quantitative PCR-based chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays to check the binding affinity of NAC016 to the AREB1 promoter. For the ChIP assay, the 2-week-old wild-type and GFP-N16 plants were placed on dry filter paper for 2 h. We found that in the leaves after 2 HDT, NAC016 binds to amplicon-d containing Site-1 (Figure 5G), indicating that NAC016 downregulates AREB1 expression by directly binding to the NAC16BM in the AREB1 promoter. Notably, AREB1 expression was downregulated in GFP-N16△C plants even under normal growth conditions, but expression levels of RD29B and RD20 were not significantly altered (Supplemental Figure 10), indicating that in addition to NAC016, activation of AREB1-dependent drought stress-responsive signaling requires environmental stresses, such as dehydration or ABA treatment, as reported previously (Fujita et al., 2005).

In the microarray and RT-qPCR analyses, we also found that the expression levels of DREB1A, a key regulator of ABA-independent drought stress-responsive signaling (Liu et al., 1998), were also significantly upregulated in nac016-1 mutants both at 0 and 2 HDT (Figure 3D; Supplemental Figure 11A), which may contribute to drought tolerance. Because the DREB1A promoter also contains a sequence (TGGATGGA) similar to the NAC16BM (Supplemental Figure 11B), we performed ChIP assays to examine whether NAC016 binds to the DREB1A promoter. These assays revealed that NAC016 does not bind to the DREB1A promoter (Supplemental Figure 11C), indicating that NAC016 downregulates DREB1A expression indirectly.

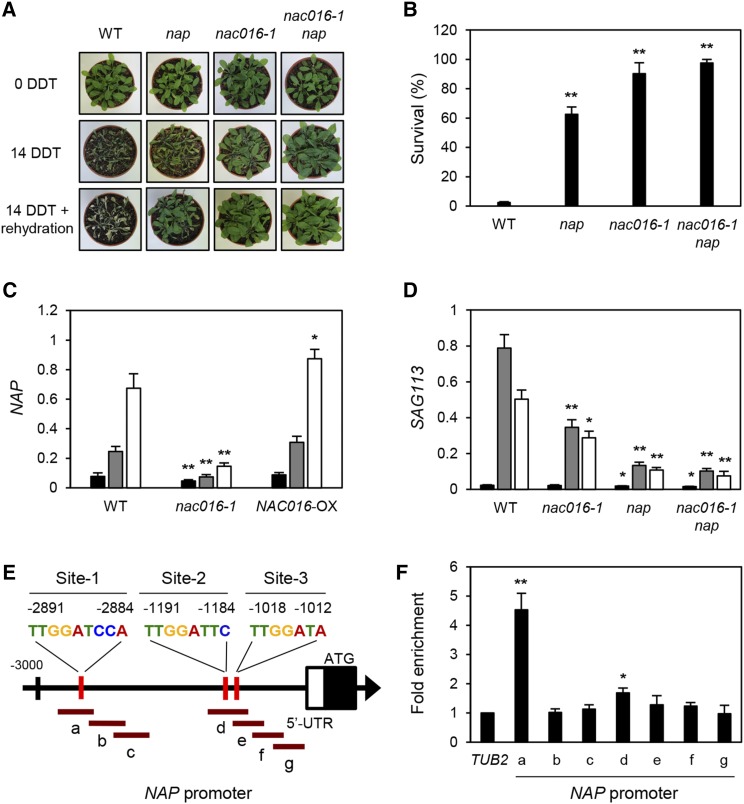

NAC016 and NAP Form a Feed-Forward Loop That Regulates AREB1

Our previous work showed that among the senNACs, NAP/NAC029 is likely one of the target genes of NAC016 (Kim et al., 2013). We found that nap mutants also showed a drought-tolerant phenotype (Figure 6A) with high survival rates (Figure 6B), although this drought tolerance was relatively weak compared with that of the nac016-1 mutants. We also prepared nac016-1 nap double mutants and found that they showed drought tolerance similar to that of the nac016-1 mutants, rather than the nap mutants (Figures 6A and 6B). The expression of NAP was downregulated in nac016-1 mutants and upregulated in NAC016-OX plants on dry filter paper (Figure 6C) and in gradually drying soil (Supplemental Figure 9D). Consistent with this, SAG113, one of the target genes of NAP (Zhang and Gan, 2012; Zhang et al., 2012), was also downregulated in nac016-1 mutants (Figure 6D). By contrast, SAG113 expression was more downregulated in the nac016-1 nap mutants than in the nac016-1 mutants, but it was almost the same as that in the nap single mutants (Figure 6D). These results indicate that NAC016 acts upstream of NAP in the same drought stress-responsive pathway.

Figure 6.

NAP016 TF Binds to the NAP Promoter and Upregulates Its Expression.

(A) and (B) Drought tolerance of nap and nac016-1 nap mutants on soil, similar to nac016-1 mutants. Mean and sd of survival rates (B) were obtained from three replications with 30 plants each. Experimental procedures were the same as in Figure 1B. These experiments were repeated three times with similar results.

(C) and (D) Expression levels of NAP in wild-type, nac016-1, and NAC016-OX (N16-OX) plants (C) and SAG113 in wild-type, nac016-1, nap, and nac016-1 nap plants (D) during drought stress. Three-week-old wild-type, nac016-1, nap, nac016-1 nap, and NAC016-OX whole plants were dehydrated on dry filter paper, and rosette leaves were sampled at 0, 1, and 2 HDT. Black, gray, and white bars indicate 0, 1, and 2 HDT, respectively. Mean and sd were obtained from more than three biological replicates. Asterisks in (B) to (D) indicate significant difference between the wild type and nac016-1, nap, nac016-1 nap, or NAC016-OX (Student’s t test P values, *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01).

(E) The structure of the AREB1 promoter. The possible NAC16BMs (red vertical lines) and PCR amplicons (brown horizontal lines a to g) for ChIP assays are indicated.

(F) NAC016 binding affinity to the NAP promoter regions in planta as shown by ChIP assays. Fold enrichment of the promoter fragments of NAP was measured by ChIP assay with an anti-GFP antibody (see Methods). The two-week-old wild-type and 35S:GFP-NAC016 plants at 2 HDT were used. TUB2 was used as a negative control. Mean and sd were obtained from more than three biological replicates. Asterisks indicate significant differences compared with TUB2 (Student’s t test P values, *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01). All the experiments were repeated at least three times with similar results.

We previously reported that NAC016 binds to the NAP promoter, as shown by yeast one-hybrid assay (Kim et al., 2013). Here, we further performed ChIP assays to identify the exact NAC016 binding sites in the NAP promoter. We identified NAC16BMs, TTGATTCCA (Site-1), and two similar sequences (Site-2 and -3) in the NAP promoter (Figure 6E). We found that NAC016 TF strongly binds to amplicon-a in Site-1, containing the core sequence of NAC16BM, but did not bind to other amplicons (Figure 6F), demonstrating that NAC016 directly binds to the NAP promoter and upregulates NAP expression.

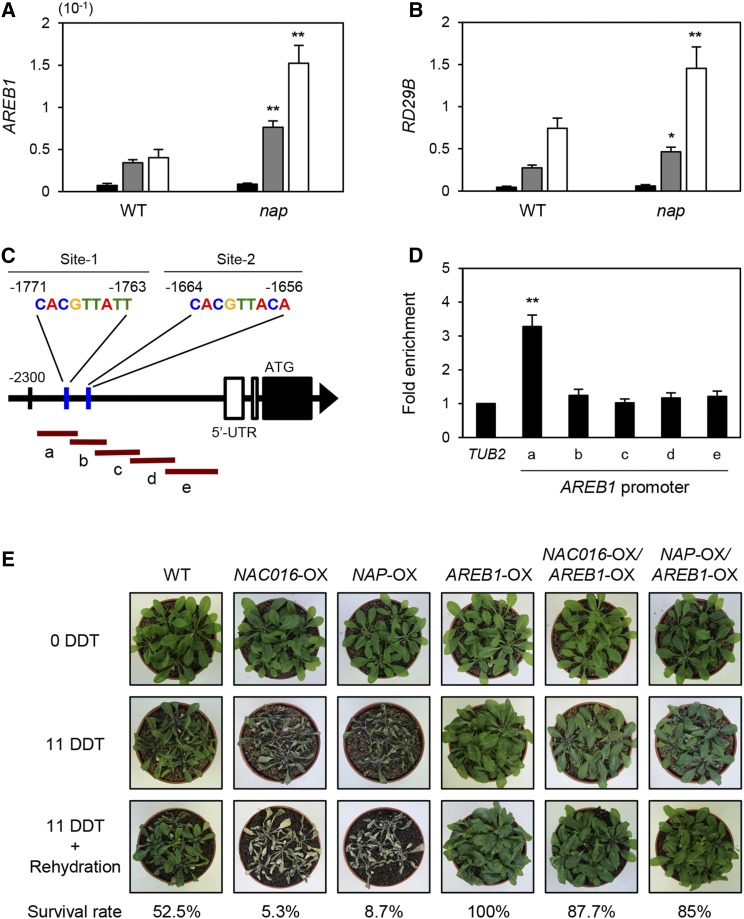

Notably, we found that expression of AREB1 and RD29B was also upregulated in nap mutants under drought stress (Figures 7A and 7B), and the AREB1 promoter contains a sequence similar to the known NAP binding motif, CACGTAAGT (Zhang and Gan, 2012) (Figure 7C). We next used ChIP assays to examine whether NAP binds to the motif in the AREB1 promoter. For the ChIP experiment, we prepared transgenic plants (Columbia-0 [Col-0] ecotype) with a 35S:NAP-GFP transgene and used RT-qPCR to measure the expression levels of NAP in four independent 35S:NAP-GFP lines (Supplemental Figure 12). We found that NAP strongly binds to the region of amplicon-a, including the motif on the AREB1 promoter (Figure 7D), indicating that NAP also binds to the AREB1 promoter and downregulates AREB1 expression.

Figure 7.

NAP Downregulates AREB1 Expression by Directly Binding to the AREB1 Promoter.

(A) and (B) AREB1 (A) and RD29B (B) expression is upregulated in nap mutants during drought stress. Three-week-old wild-type and nap whole plants were dehydrated on dry filter paper, and rosette leaves were sampled at 0, 1, and 2 HDT. Black, gray, and white bars indicate 0, 1, and 2 HDT, respectively. Mean and sd were obtained from more than three biological replicates. Asterisks indicate significant difference between the wild type and nap (Student’s t test P value, **P < 0.01).

(C) The structure of the AREB1 promoter. Two possible NAP binding motifs (blue vertical lines) and PCR amplicons (a to e) for ChIP assays (brown horizontal lines) are indicated.

(D) NAP binding affinity to the AREB1 promoter regions in planta. Fold enrichment of the promoter fragments of NAP was measured by ChIP assay with an anti-GFP antibody (see Methods). Two-week-old wild-type and NAP-GFP plants at 2 HDT were used. TUB2 was used as a negative control. Mean and sd were obtained from more than three biological replicates. Asterisks indicate significant difference compared with TUB2 (Student’s t test P value, **P < 0.01).

(E) Drought tolerance phenotype of NAC016-OX/AREB1-OX and NAP-OX/AREB1-OX mutants on the soil, similar to AREB1-OX mutants.

These experiments were repeated three times with similar results.

We further investigated the drought tolerance of AREB-OX/NAC016-OX and AREB1-OX/NAP-OX plants. We first confirmed the higher expression of AREB1 in four independent AREB1-OX lines by RT-qPCR (Supplemental Figure 13) and showed that all the AREB1-OX lines were tolerant to drought stress (Figure 7D) as previously reported (Fujita et al., 2005). Under drought stress conditions, AREB-OX/NAC016-OX and AREB1-OX/NAP-OX plants showed drought tolerance similar to AREB1-OX plants (Figure 7D). These results indicate that the repression of AREB1 transcription requires both NAC016 and NAC016-induced NAP for drought stress responses in Arabidopsis.

DISCUSSION

NAC016 Selectively Regulates Its Target Genes via Its Binding Motif

Plant genomes encode many NAC TFs, with 106 NACs in Arabidopsis (Riechmann et al., 2000), and each NAC TF likely has its own binding motif, which allows each NAC TF to regulate different target genes in different signaling pathways. Tran et al. (2004) found that the three stress-induced NAC TFs NAC019, NAC055, and NAC072 specifically bind to the CACG sequence in the promoter of EARLY RESPONSIVE TO DEHYDRATION STRESS1. Furthermore, these three NAC TFs also bind to the sequence CGTG (the reverse complement of CACG), in the promoter of the dehydration-induced NAC gene RD26/NAC072. Indeed, the binding motifs of other NACs, including ORE1, NAP, NTL4, and NAC017, contain the CACG or CGTG sequences (Olsen et al., 2005; Lee and Park, 2012; Zhang and Gan, 2012; Ng et al., 2013; Supplemental Table 6). These results indicate that CACG and CGTG constitute the 4-bp core sequence of the NAC binding motif.

NAC016, a C-terminal TMD-containing senNAC, has a close phylogenetic relationship to other TMD-containing NACs (Ooka et al., 2003). Recent work reported that NAC016 and four other TMD-containing NAC TFs (NAC013, NAC017, NAC053/NTL4, and NAC078) specifically bind to the MDM, CTTGXXXXXCA[AC]G (Figure 4E; De Clercq et al., 2013). However, the binding activity of NAC016 to the MDM is relatively weak compared with the binding of the other TMD-containing NACs, such as NAC013 (De Clercq et al., 2013). Similarly, NAC013 strongly upregulates the expression of MDM-containing genes, but NAC016 and NTL4 do not (Ng et al., 2013). Thus, these data show that NAC016 uses other binding motifs to regulate its target genes.

In this study, we used microarray analysis, the MEME motif discovery program, and yeast one-hybrid assays to identify the NAC16BM, GATTGGAT[AT]CA (Figures 4B to 4D). The NAC16BM has some sequence similarity to the MDM (Figure 4E), and our mutation analysis showed that common sequences of NAC16BM and MDM, such as TTG (3rd to 5th) and A (11th) in the NAC016BM, are most essential for the binding activity of NAC016 (Figure 4C). Thus, it is likely that NAC016 can bind to both the NAC16BM and the MDM but that NAC016 regulates only the NAC16BM-containing genes. Notably, the NAC16BM does not contain the CACG or CGTG sequence (Figure 4B). Thus, NAC16BM differs from the previously identified binding motifs for NAC TFs (Supplemental Table 6). Recent work has reported different NAC binding motifs that do not harbor the CACG/CGTG core sequence. For example, Wu et al. (2012) found that the binding motif of NAC042/JUB1, TGCCGTXXXXXXXACG, does not contain the CACG/CGTG sequence. The different binding motifs specific to different NACs have likely evolved to provide further selectivity in regulating their target genes, depending on different internal and external signals, during plant growth and development.

NAC017, a C-terminal TMD-containing senNAC, has ∼70% sequence similarity to NAC016 (Kim et al., 2013). However, the TF functions of the two NACs seem to be quite different from each other; nac016 mutants exhibit a stay-green phenotype during leaf senescence and under salt and H2O2 stresses, but nac017 mutants senesce normally and turn yellow at the same rate as the wild type (Kim et al., 2013). Interestingly, NAC017 also affects the drought stress response. In contrast with the function of NAC016, however, NAC017 inhibits the H2O2-dependent drought stress response, as demonstrated by the dehydration-sensitive phenotype of nac017-1 knockout mutants (Ng et al., 2013). Although NAC017 can bind to the MDM, NAC017 activates its target gene expression by binding to the CACG or CAAG core sequence of the NAC binding motif (Ng et al., 2013). Our RT-qPCR analysis revealed that the expression level of AOX1a, one of the target genes of NAC017 (Ng et al., 2013), was not altered in nac016-1 and NAC016-OX plants (Supplemental Figure 8B), indicating that NAC016 and NAC017 have different target genes and thus regulate different drought stress-responsive pathways.

In this study, we also found other interesting candidate NAC016 targets, including MAF4, MAF5, ABC2, and QUA-QUINE STARCH (QQS). These four NAC016 target genes were strongly downregulated in nac016-1 mutants at 0 and 2 HDT (Figure 4A; Supplemental Tables 2 and 4). MAF4 and MAF5 are classified in the FLOWERING LOCUS C clade, which includes other MAF genes (Ratcliffe et al., 2003). QQS negatively regulates starch accumulation (Li et al., 2009), and QQS-OX plants exhibit severely retarded growth (Seo et al., 2011). However, the flowering time and plant size of nac016 mutants and NAC016-OX plants were almost the same as those of the wild type under normal growth conditions (Kim et al., 2013). Thus, it is so far unclear how these target genes function in the NAC016 regulatory cascade. Further phenome analysis of nac016 mutants and NAC016-OX plants will be required to understand the NAC016-mediated crosstalk among several signaling pathways, including leaf senescence, abiotic stress-responsive (salt, oxidative, and dehydration) pathways, and other developmental signaling.

The Regulatory Network of the NAC016-Dependent Drought Response Pathway

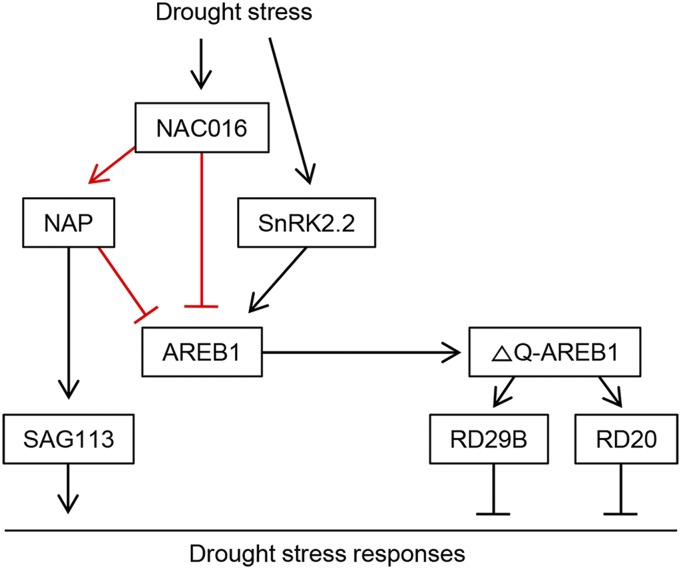

As shown above, AREB1 functions as a key factor in the NAC016-dependent drought stress-responsive pathway. NAC016 binds strongly to the NAC16BM in the AREB1 promoter and downregulates AREB1 expression under drought stress (Figure 5). We found that knockout mutants of NAP, one of the NAC016 targets (Kim et al., 2013), also exhibit drought tolerance (Figure 6). Furthermore, NAP also binds to the NAP binding motif in the AREB1 promoter and directly downregulates AREB1 expression (Figure 7). The drought tolerance of nap mutants likely results from regulation of two important target genes, AREB1 and SAG113. The sag113 knockout mutants show increased sensitivity to exogenous ABA, and detached sag113 leaves have lower water loss rates than wild-type leaves (Zhang et al., 2012). The regulatory modules involving NAC016-AREB1 and NAP-AREB1 were also confirmed by genetic analysis, as AREB1-OX/NAC016-OX and AREB1-OX/NAP-OX plants showed strong drought tolerance, similar to AREB1-OX plants (Figure 7E). Taken together, these results indicate that NAC016, NAP, and AREB1 likely establish coherent feed-forward loops (Figure 8). Similar feed-forward regulatory mechanisms have been previously reported. For example, ETHYLENE INSENSITIVE2 (EIN2), miR164, and ORE1 form similar coherent feed-forward loops, where EIN2, likely through EIN3, activates ORE1 expression and simultaneously inhibits miR164 expression, which inhibits ORE1 expression (Kim et al., 2009; Li et al., 2013). Such coherent feed-forward loops may increase the robustness of biological signaling processes (Mangan and Alon, 2003).

Figure 8.

Model of NAC016-Mediated Drought Stress-Responsive Signaling.

Under drought stress, NAC016 represses the expression of AREB1 by forming coherent feed-forward loops with NAP. Black and red lines indicate the regulation modules that were found previously or in this study, respectively. ∆Q-AREB1 represents the active form of AREB1, induced by a cleavage of the N-terminal Q domain (Fujita et al., 2005).

In addition to NAC016 and NAP, work in Arabidopsis has identified many other NAC genes that regulate the drought stress-responsive pathways. For example, NTL4/NAC053 promotes drought stress responses and ntl4 mutants exhibit drought tolerance (Lee and Park, 2012). By contrast, NAC019, NAC055, NAC072, and NAC096 negatively regulate drought stress responses; plants overexpressing these NACs show drought tolerance (Tran et al., 2004; Xu et al., 2013). Those previous reports, taken together with the results of this study, show that NAC TFs, including NAC016 and NAP, have important roles in fine-tuning the spatiotemporal control of drought stress-responsive signaling. Interestingly, the seven drought stress-associated NAC TFs (NAC016, NAC019, NAP, NAC053/NTL4, NAC055, NAC072, and NAC096) are closely associated with ABA response pathways (Tran et al., 2004; Lee and Park, 2012; Zhang et al., 2012; Xu et al., 2013). Thus, these NAC TFs probably have related functions in fine-tuning ABA-dependent drought stress-responsive pathways. NAC TFs can form homo- and heterodimers (Olsen et al., 2005). In addition, NAC096 forms heterodimers with bZIP-type TFs, such as ABF2 and ABF4, to coactivate their common target genes, including RD29A (Xu et al., 2013). Thus, it is possible that these drought stress-associated NAC TFs form homo- and heterodimers to control transcription. The analysis of transcriptional and posttranslational relationships among these NAC proteins will be necessary to further understand drought stress signaling mechanisms.

One intriguing question is how NAC016 directly downregulates AREB1 expression. The NAC16BM generally occurs in the promoters of the genes that are downregulated in nac016-1 mutants (Supplemental Table 2), and we also found that NAC016 directly activates NAP transcription during both drought stress and leaf senescence (Figure 6; Kim et al., 2013), indicating that NAC016 usually acts as a transcriptional activator. However, NAC016 acts as a direct transcriptional repressor of AREB1 expression. TFs sometimes act as both transcriptional activators and repressors for different target genes. For instance, PHYTOCHROME-INTERACTING FACTOR1 represses the gene for one of the carotenoid biosynthesis enzymes, PHYTOENE SYNTHASE (PSY; Toledo-Ortiz et al. 2010), but it activates transcription of the gene for a chlorophyll biosynthesis enzyme, PROTOCHLOROPHYLLIDE A OXIDOREDUCTASE C (PORC; Moon et al., 2008), by directly binding to the promoters of both PSY and PORC. TF activity often depends on specific cofactors (Glass and Rosenfeld, 2000). In this respect, it is possible that an unknown cofactor(s) controls the TF activity of NAC016 to repress AREB1 expression. Furthermore, NAP directly represses AREB1 expression (Figure 7), indicating that one or more corepressors affect the transcriptional control of AREB1. Identification of these unknown cofactors will improve our understanding of NAC016 TF activity and the NAC016-dependent drought stress-responsive pathway.

METHODS

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

Arabidopsis thaliana (Col-0) was grown on soil at 22 to 24°C under long-day (LD) conditions (16 h light/8 h dark) for 3 weeks and was used in stress treatment experiments prior to bolting. Arabidopsis rosette leaves were harvested from the plants grown on soil and then dehydrated on Whatman 3MM paper at 22°C and 50% humidity under dim light (Yamaguchi-Shinozaki and Shinozaki, 1994). The nac016-1 (SALK_001597C), nac016-2 (SALK_074316), and nap (SALK_005010C) mutants were obtained from the ABRC (Ohio State University). The nac016-1 nap double mutant was prepared by crossing the nac016-1 and nap single mutants. The plants were subjected to stress treatments for various periods and then frozen in liquid nitrogen for further analyses.

Plant Transformation

The full-length NAC016, NAP, and AREB1 cDNAs were amplified by RT-PCR using M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Promega) and PrimeSTAR polymerase (TaKaRa) and cloned into the pCR8/GW/TOPO Gateway vector (Invitrogen). The NAC016 and NAP cDNAs were recombined into the pMDC43 and pMDC85 plasmids (Curtis and Grossniklaus, 2003), thereby introducing the N- and C-terminal GFP tags, respectively. The AREB1 cDNA was recombined into the pMDC32 plasmid for overexpression of AREB1 without an epitope tag. In all cases, transgene expression was driven by the constitutive 35S promoter. The recombinant plasmids were transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens stain GV3101. Agrobacterium-mediated transformation into the wild type (Col-0) was performed by the floral dip method (Zhang et al., 2006). Transgenic T1 seedlings were selected on 0.5× Murashige and Skoog phytoagar medium supplemented with 2 mM MES buffer (pH 5.8) and 15 mg L−1 hygromycin. T1 lines that segregated at a ratio of ∼3:1 on selective agar plates and showed high expression of the transgenes were selected and their T2 seeds harvested. Homozygous T2 lines were identified on selective agar plates and their progenies were used for further analysis. Double OX plants, N16-OX/AREB1-OX and NAP-OX/AREB1-OX, were prepared by crossing homozygous lines of two single OX plants.

Total Chlorophyll Measurement

To measure total chlorophyll levels, photosynthetic pigments were extracted from the leaf tissues with 80% ice-cold acetone. Chlorophyll concentrations were determined using a UV/VIS spectrophotometer as described previously (Lichtenthaler and Buschmann, 1987).

Stomatal Aperture Analysis

The stomatal aperture of abaxial leaf epidermal strips was analyzed as previously described (Zhang et al., 2012) with minor modification. The rosette leaves detached from 3-week-old plants grown under LD were floated in a solution of 3 mM MES (pH 6.15) containing 50 mM KCl (MES-KCl) for 2 h under light at 22°C to open the stomata. The leaves were then transferred to MES-KCl buffer containing 10 μM ABA for 3 h. Stomatal cells were observed using a light microscope (Axio Observer Z.1; Carl Zeiss).

Water Loss Assay

For water loss measurements, 3-week-old plants with roots were weighed at 3-h intervals using a microbalance. Water loss rates were recorded at 12 h after dehydration and measured as a percentage of the initial weight of fully hydrated rosettes.

Immunoblot Analysis

Subcellular localization of GFP-NAC016 and GFP NAC016△C was examined by immunoblot analysis. Total protein, nuclear, and cytoplasmic fractions were extracted from the leaves of 2-week-old GFP-NAC016 and GFP-NAC016△C transgenic plants grown on soil under normal LD conditions using the CelLytic PN isolation/extraction kit (Sigma-Aldrich). The cleavage of the C-terminal TMD of NAC016 was also confirmed by immunoblot analysis. Three-week-old GFP-NAC016 plants were subjected to dehydration on dry filter paper for 2 h or extended darkness (2 d). Total protein extracts were obtained by grinding the leaf tissue in liquid nitrogen followed by resuspension in 2 volumes of extraction buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Nonidet P-40, and 4 M urea) on ice. Total extracts were centrifuged at 15,000g at 4°C for 15 min, and supernatants were mixed with SDS-PAGE sample buffer (125 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 4% SDS, 20% glycerol, 2% β-mercaptoethanol, 0.001% and bromophenol blue). For both experiments, 2 μg protein samples were subjected to 12% (w/v) SDS-PAGE and resolved proteins were electroblotted onto Hybond-P membrane (GE Healthcare). Antibodies against the photosystem proteins GFP (Abcam), RPT5 (Abcam), and RbcL (Agrisera) were used for immunoblot analysis. The level of each protein was examined using the ECL system (Westsave kit; AbFRONTIER) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Microarray Analysis

Three-week-old wild type and nac016-1 plants were dehydrated on dry filter paper for 2 h (2 HDT), and leaves were sampled for RNA purification. Total RNA was extracted from the leaves of 3-week-old soil-grown wild-type plants and nac016 mutants using the TRIzol reagent according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen). Total RNA quality was checked using a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies). Microarray analysis was performed using the Arabidopsis (V4) Gene Expression Microarray, design identifier 021169 (Agilent), containing 43,803 Arabidopsis gene probes and 1417 Agilent control probes. Total RNA (150 ng) was used to prepare Cy3-labeled probes, using the low-RNA-input linear amplification Plus kit (Agilent). Labeled RNA probes were fragmented using the Gene Expression Hybridization buffer kit (Agilent). All microarray experiments, including data analysis, were performed according to the manufacturer’s manual (http://www.chem.agilent.com/scripts/pcol.asp?l-page=494). The arrays were air-dried and scanned using a high-resolution array scanner (Agilent) with the appropriate settings for two-color gene expression arrays. GeneSpring GX (Agilent) was used to calculate the intensity ratio and fold changes. Microarray analysis was performed in two experimental replicates with two different biological replicates of wild-type and nac016-1 plants. The normalized values and t test P values from the two sets were averaged, and then selection criteria of t test P value < 0.05 and normalized values >2 or <0.5 were applied to identify differentially expressed genes, which were then used to prepare Venn diagrams (Figures 3B and 3C; Supplemental Tables 1 to 4).

MEME Analysis

For MEME (Multiple Em for Motif Elicitation) analysis, sequences corresponding to the promoter region (−1500 to 0 from ATG codon) of the downregulated genes (Supplemental Table 2) were obtained from The Arabidopsis Information Resource (www.arabidopsis.org). Upstream DNA sequences were subjected to the MEME program and analyzed using the previously described parameters (Bailey et al., 2006; http://meme.nbcr.net/meme/cgi-bin/meme.cgi)

Yeast One-Hybrid Assays

The NAC016 coding sequence was inserted into the pGAD424 vector (Clontech) as a prey. DNA fragments corresponding to the promoters (250 to 300 bp) of NAC016 target genes (MAF4, MAF5, and ABC2) that include the NAC16BM (Supplemental Figure 6) were cloned into the pLacZi plasmid (Clontech) as baits. For the mutation analysis of the NAC16BM, we prepared a series of one-nucleotide substituted sequences, which were fused to a fragment of the TUBULIN2 (TUB2) promoter (−465 to −214 from start codon); NAC016 did not bind to this fragment of the TUB2 promoter, which does not contain a NAC016BM. These fusions were then cloned into the pLacZi plasmid. Primers used for cloning are listed in Supplemental Table 7. The yeast strain YM4271 was used for bait and prey clones, and β-galactosidase activity (1 unit = 104 min−1 mL−1) was measured by liquid assay using chlorophenol red-β-d-galactopyranoside (CPRG; Roche Applied Science) according to the Yeast Protocol Handbook (Clontech).

Measurement of Ion Leakage Rates

Membrane leakage was measured as described previously (Fan et al., 1997), with minor modifications. Membrane leakage was determined by measurement of electrolytes (or ions) that leaked from detached leaves. Ten leaves from each treatment were immersed in 6 mL 0.4 M mannitol at room temperature with gentle shaking for 3 h, and the solution was measured for conductivity with a conductivity meter (CON6 meter; LaMOTTE). Total conductivity was determined after the sample was incubated at 85°C for 20 min. The rate of ion leakage was expressed as the percentage of initial conductivity divided by total conductivity.

ChIP Assays

The plants overexpressing GFP-NAC016, NAP-GFP, and the wild type were grown for 14 d under LD conditions and then dehydrated for 2 h on filter paper before cross-linking for 20 min with 1% formaldehyde under vacuum. Chromatin complexes were isolated and sonicated as previously described (Saleh et al., 2008) with slight modification. Anti-GFP polyclonal antibody (Abcam) and Protein A agarose/salmon sperm DNA (Millipore) were used for immunoprecipitation. After reverse cross-linking and protein digestion, DNA was purified by QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen). Primer sequences for each gene are listed in Supplemental Table 7.

RT-PCR and Quantitative PCR Analysis

For RT-PCR analysis, total RNA was isolated from rosette leaves using the TRIzol reagent according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen). First-strand cDNAs were prepared with 5 μg total RNA in a 25-μL reaction volume using M-MLV reverse transcriptase and oligo(dT)15 primer (Promega) and diluted with water to 100 μL. The quantitative PCR mixture contained 1 μL cDNA template, 10 μL 2× SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Qiagen) and 0.25 mM forward and reverse primers for each gene. Primer sequences for each gene are listed in Supplemental Table 7. Quantitative PCR was performed using the Light Cycler 480 (Roche Diagnostics). Transcript levels of each gene were normalized to GLYCERALDEHYDE PHOSPHATE DEHYDROGENASE (GAPDH).

Accession Numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in The Arabidopsis Information Resource (http://www.arabidopsis.org/) under the following accession numbers: ABC2 (AT5G61740), AOX1a (AT3G22370), AREB1 (AT1G45249), AtrbohC (AT5G51060), DREB1 (AT4G25480), GAPDH (AT1G16300), MAF4 (AT5G65070), MAF5 (AT5G65080), NAC016 (AT1G34180), NAC029/NAP (AT1G69490), RD20 (AT2G33380), RD29B (AT5G52300), SAG113 (AT5G59220), SnRK2.2 (AT3G50500), and TUB2 (AT5G62690).

Supplemental Data

Supplemental Figure 1. Expression of NAC016 in Wild-Type Leaves during Cold and Heat Treatments.

Supplemental Figure 2. Phenotypes of nac016-1 Mutants and NAC016-OX Plants under Drought Stress.

Supplemental Figure 3. The nac016-1 Mutants Show ABA Hypersensitivity in Stomatal Aperture.

Supplemental Figure 4. Expression of NAC016 in GFP-N16 and GFP-N16△C Transgenic Lines.

Supplemental Figure 5. Expression of SAGs in Wild-Type, GFP-N16, and GFP-N16△C Plants.

Supplemental Figure 6. The Location of NAC16BM in the Promoters of Downregulated Genes in nac016-1 Mutants.

Supplemental Figure 7. Accumulation of H2O2 in Wild-Type, nac016-1, and NAC016-OX Plants under Drought Stress.

Supplemental Figure 8. NAC016 Does Not Regulate the Expression of AtrbohC and AOX1a.

Supplemental Figure 9. Transcript Levels of AREB1, RD29B, RD20, and NAP in Wild-Type and nac016-1 Plants under Drought Stress on Soil.

Supplemental Figure 10. Altered Expression Levels of AREB1, RD29B, and RD20 in Wild-Type, GFP-N16, and GFP-N16△C Plants.

Supplemental Figure 11. NAC016 Does Not Directly Regulate DREB1 Expression.

Supplemental Figure 12. Expression Levels of NAP in NAP-GFP Transgenic Lines.

Supplemental Figure 13. Expression Levels of AREB1 in AREB1-OX Transgenic Lines.

Supplemental Table 1. Upregulated Genes in nac016-1 Mutants at 0 HDT (Fold > 2).

Supplemental Table 2. Downregulated Genes in nac016-1 Mutants at 0 HDT (Fold < 0.5).

Supplemental Table 3. Upregulated Genes in nac016-1 Mutants at 2 HDT (Fold > 2).

Supplemental Table 4. Downregulated Genes in nac016-1 Mutants at 2 HDT (Fold < 0.5).

Supplemental Table 5. NAC16BM in the Promoters of Up- or Downregulated Genes.

Supplemental Table 6. Specific Binding Motifs of Arabidopsis NAC TFs.

Supplemental Table 7. Primers Used in This Study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea grant funded by the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology (NRF-2011-0017308).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Y.S. and N.-C.P. designed the research. Y.S. and Y.-S.K. performed the experiments. S.-H.H. and B.-D.L. assisted the research and generated the transgenic lines. Y.S. and N.-C.P. analyzed the data and wrote the article.

Glossary

- ABA

abscisic acid

- TF

transcription factor

- TMD

transmembrane domain

- senNAC

senescence-associated NAC

- HDT

hours of dry treatment

- RT-qPCR

reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

- DDI

days of dark incubation

- MW

molecular weight

- DEG

differentially expressed gene

- MDM

mitochondrial dysfunction motif

- ChIP

chromatin immunoprecipitation

- Col-0

Columbia-0

- LD

long-day

- CPRG

chlorophenol red-β-d-galactopyranoside

Footnotes

Articles can be viewed online without a subscription.

References

- Aida M., Ishida T., Fukaki H., Fujisawa H., Tasaka M. (1997). Genes involved in organ separation in Arabidopsis: an analysis of the cup-shaped cotyledon mutant. Plant Cell 9: 841–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey T.L., Williams N., Misleh C., Li W.W. (2006). MEME: discovering and analyzing DNA and protein sequence motifs. Nucleic Acids Res. 34: W369–W373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balazadeh S., Siddiqui H., Allu A.D., Matallana-Ramirez L.P., Caldana C., Mehrnia M., Zanor M.I., Köhler B., Mueller-Roeber B. (2010). A gene regulatory network controlled by the NAC transcription factor ANAC092/AtNAC2/ORE1 during salt-promoted senescence. Plant J. 62: 250–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi G., Gamba A., Murelli C., Salamini F., Bartels D. (1991). Novel carbohydrate metabolism in the resurrection plant Craterostigma plantagineum. Plant J. 1: 355–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer J.S. (1982). Plant productivity and environment. Science 218: 443–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bu Q., Jiang H., Li C.B., Zhai Q., Zhang J., Wu X., Sun J., Xie Q., Li C. (2008). Role of the Arabidopsis thaliana NAC transcription factors ANAC019 and ANAC055 in regulating jasmonic acid-signaled defense responses. Cell Res. 18: 756–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis M.D., Grossniklaus U. (2003). A Gateway cloning vector set for high-throughput functional analysis of genes in planta. Plant Physiol. 133: 462–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Clercq I., et al. (2013). The membrane-bound NAC transcription factor ANAC013 functions in mitochondrial retrograde regulation of the oxidative stress response in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 25: 3472–3490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst H.A., Olsen A.N., Larsen S., Lo Leggio L. (2004). Structure of the conserved domain of ANAC, a member of the NAC family of transcription factors. EMBO Rep. 5: 297–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan L., Zheng S., Wang X. (1997). Antisense suppression of phospholipase D alpha retards abscisic acid- and ethylene-promoted senescence of postharvest Arabidopsis leaves. Plant Cell 9: 2183–2196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita M., Fujita Y., Maruyama K., Seki M., Hiratsu K., Ohme-Takagi M., Tran L.S., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K., Shinozaki K. (2004). A dehydration-induced NAC protein, RD26, is involved in a novel ABA-dependent stress-signaling pathway. Plant J. 39: 863–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita Y., Fujita M., Satoh R., Maruyama K., Parvez M.M., Seki M., Hiratsu K., Ohme-Takagi M., Shinozaki K., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. (2005). AREB1 is a transcription activator of novel ABRE-dependent ABA signaling that enhances drought stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 17: 3470–3488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita Y., et al. (2009). Three SnRK2 protein kinases are the main positive regulators of abscisic acid signaling in response to water stress in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 50: 2123–2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass C.K., Rosenfeld M.G. (2000). The coregulator exchange in transcriptional functions of nuclear receptors. Genes Dev. 14: 121–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong W., et al. (2004). Genome-wide ORFeome cloning and analysis of Arabidopsis transcription factor genes. Plant Physiol. 135: 773–782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y., Gan S. (2006). AtNAP, a NAC family transcription factor, has an important role in leaf senescence. Plant J. 46: 601–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickman R., et al. (2013). A local regulatory network around three NAC transcription factors in stress responses and senescence in Arabidopsis leaves. Plant J. 75: 26–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen M.K., Kjaersgaard T., Nielsen M.M., Galberg P., Petersen K., O’Shea C., Skriver K. (2010). The Arabidopsis thaliana NAC transcription factor family: structure-function relationships and determinants of ANAC019 stress signalling. Biochem. J. 426: 183–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.H., Woo H.R., Kim J., Lim P.O., Lee I.C., Choi S.H., Hwang D., Nam H.G. (2009). Trifurcate feed-forward regulation of age-dependent cell death involving miR164 in Arabidopsis. Science 323: 1053–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M.J., Park M.J., Seo P.J., Song J.S., Kim H.J., Park C.M. (2012). Controlled nuclear import of the transcription factor NTL6 reveals a cytoplasmic role of SnRK2.8 in the drought-stress response. Biochem. J. 448: 353–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y.S., Sakuraba Y., Han S.H., Yoo S.C., Paek N.C. (2013). Mutation of the Arabidopsis NAC016 transcription factor delays leaf senescence. Plant Cell Physiol. 54: 1660–1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusaba M., Ito H., Morita R., Iida S., Sato Y., Fujimoto M., Kawasaki S., Tanaka R., Hirochika H., Nishimura M., Tanaka A. (2007). Rice NON-YELLOW COLORING1 is involved in light-harvesting complex II and grana degradation during leaf senescence. Plant Cell 19: 1362–1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S., Park C.M. (2012). Regulation of reactive oxygen species generation under drought conditions in Arabidopsis. Plant Signal. Behav. 7: 599–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Foster C.M., Gan Q., Nettleton D., James M.G., Myers A.M., Wurtele E.S. (2009). Identification of the novel protein QQS as a component of the starch metabolic network in Arabidopsis leaves. Plant J. 58: 485–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Peng J., Wen X., Guo H. (2013). Ethylene-insensitive3 is a senescence-associated gene that accelerates age-dependent leaf senescence by directly repressing miR164 transcription in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 25: 3311–3328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenthaler H.K., Buschmann C. (1987). Chlorophyll fluorescence spectra of green bean leaves. J. Plant Physiol. 129: 137–147. [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q., Kasuga M., Sakuma Y., Abe H., Miura S., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K., Shinozaki K. (1998). Two transcription factors, DREB1 and DREB2, with an EREBP/AP2 DNA binding domain separate two cellular signal transduction pathways in drought- and low-temperature-responsive gene expression, respectively, in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 10: 1391–1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangan S., Alon U. (2003). Structure and function of the feed-forward loop network motif. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100: 11980–11985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon J., Zhu L., Shen H., Huq E. (2008). PIF1 directly and indirectly regulates chlorophyll biosynthesis to optimize the greening process in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105: 9433–9438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng S., et al. (2013). A membrane-bound NAC transcription factor, ANAC017, mediates mitochondrial retrograde signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 25: 3450–3471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen A.N., Ernst H.A., Lo Leggio L., Skriver K. (2005). DNA-binding specificity and molecular functions of NAC transcription factors. Plant Sci. 169: 785–797. [Google Scholar]

- Ooka H., et al. (2003). Comprehensive analysis of NAC family genes in Oryza sativa and Arabidopsis thaliana. DNA Res. 10: 239–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramanjulu S., Sudhakar C. (1997). Drought tolerance is partly related to amino acid accumulation and ammonia assimilation: a comparative study in two mulberry genotypes differing in drought sensitivity. J. Plant Physiol. 150: 345–350. [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliffe O.J., Kumimoto R.W., Wong B.J., Riechmann J.L. (2003). Analysis of the Arabidopsis MADS AFFECTING FLOWERING gene family: MAF2 prevents vernalization by short periods of cold. Plant Cell 15: 1159–1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren T., Qu F., Morris T.J. (2000). HRT gene function requires interaction between a NAC protein and viral capsid protein to confer resistance to turnip crinkle virus. Plant Cell 12: 1917–1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riechmann J.L., et al. (2000). Arabidopsis transcription factors: genome-wide comparative analysis among eukaryotes. Science 290: 2105–2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakuma Y., Maruyama K., Osakabe Y., Qin F., Seki M., Shinozaki K., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. (2006a). Functional analysis of an Arabidopsis transcription factor, DREB2A, involved in drought-responsive gene expression. Plant Cell 18: 1292–1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakuma Y., Maruyama K., Qin F., Osakabe Y., Shinozaki K., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. (2006b). Dual function of an Arabidopsis transcription factor DREB2A in water-stress-responsive and heat-stress-responsive gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103: 18822–18827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleh A., Alvarez-Venegas R., Avramova Z. (2008). An efficient chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) protocol for studying histone modifications in Arabidopsis plants. Nat. Protoc. 3: 1018–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo P.J., Kim M.J., Park J.Y., Kim S.Y., Jeon J., Lee Y.H., Kim J., Park C.M. (2010). Cold activation of a plasma membrane-tethered NAC transcription factor induces a pathogen resistance response in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 61: 661–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo P.J., Kim M.J., Ryu J.Y., Jeong E.Y., Park C.M. (2011). Two splice variants of the IDD14 transcription factor competitively form nonfunctional heterodimers which may regulate starch metabolism. Nat. Commun. 2: 303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo P.J., Kim S.G., Park C.M. (2008). Membrane-bound transcription factors in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 13: 550–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahnejat-Bushehri S., Mueller-Roeber B., Balazadeh S. (2012). Arabidopsis NAC transcription factor JUNGBRUNNEN1 affects thermomemory-associated genes and enhances heat stress tolerance in primed and unprimed conditions. Plant Signal. Behav. 7: 1518–1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinozaki K., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. (2007). Gene networks involved in drought stress response and tolerance. J. Exp. Bot. 58: 221–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souer E., van Houwelingen A., Kloos D., Mol J., Koes R. (1996). The no apical meristem gene of Petunia is required for pattern formation in embryos and flowers and is expressed at meristem and primordia boundaries. Cell 85: 159–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streeter J.G., Lohnes D.G., Fioritto R.J. (2001). Patterns of pinitol accumulation in soybean plants and relationships to drought tolerance. Plant Cell Environ. 24: 429–438. [Google Scholar]

- Toledo-Ortiz G., Huq E., Rodríguez-Concepción M. (2010). Direct regulation of phytoene synthase gene expression and carotenoid biosynthesis by phytochrome-interacting factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107: 11626–11631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran L.S., Nakashima K., Sakuma Y., Simpson S.D., Fujita Y., Maruyama K., Fujita M., Seki M., Shinozaki K., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. (2004). Isolation and functional analysis of Arabidopsis stress-inducible NAC transcription factors that bind to a drought-responsive cis-element in the early responsive to dehydration stress 1 promoter. Plant Cell 16: 2481–2498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran L.S., Nakashima K., Shinozaki K., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. (2007). Plant gene networks in osmotic stress response: from genes to regulatory networks. Methods Enzymol. 428: 109–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran L.S., Nishiyama R., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K., Shinozaki K. (2010). Potential utilization of NAC transcription factors to enhance abiotic stress tolerance in plants by biotechnological approach. GM Crops 1: 32–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valliyodan B., Nguyen H.T. (2006). Understanding regulatory networks and engineering for enhanced drought tolerance in plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 9: 189–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu A., et al. (2012). JUNGBRUNNEN1, a reactive oxygen species-responsive NAC transcription factor, regulates longevity in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 24: 482–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Q., Frugis G., Colgan D., Chua N.H. (2000). Arabidopsis NAC1 transduces auxin signal downstream of TIR1 to promote lateral root development. Genes Dev. 14: 3024–3036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Y., Liu T., Tian C., Sun S., Li J., Chen M. (2005). Transcription factors in rice: a genome-wide comparative analysis between monocots and eudicots. Plant Mol. Biol. 59: 191–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z.Y., Kim S.Y., Hyeon Y., Kim D.H., Dong T., Park Y., Jin J.B., Joo S.H., Kim S.K., Hong J.C., Hwang D., Hwang I. (2013). The Arabidopsis NAC transcription factor ANAC096 cooperates with bZIP-type transcription factors in dehydration and osmotic stress responses. Plant Cell 25: 4708–4724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yabuta Y., Morishita T., Kojima Y., Maruta T., Nishizawa-Yokoi A., Shigeoka S. (2010). Identification of recognition sequence of ANAC078 protein by the cyclic amplification and selection of targets technique. Plant Signal. Behav. 5: 695–697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K., Shinozaki K. (1994). A novel cis-acting element in an Arabidopsis gene is involved in responsiveness to drought, low-temperature, or high-salt stress. Plant Cell 6: 251–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K., Gan S.S. (2012). An abscisic acid-AtNAP transcription factor-SAG113 protein phosphatase 2C regulatory chain for controlling dehydration in senescing Arabidopsis leaves. Plant Physiol. 158: 961–969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K., Xia X., Zhang Y., Gan S.S. (2012). An ABA-regulated and Golgi-localized protein phosphatase controls water loss during leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 69: 667–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Henriques R., Lin S.S., Niu Q.W., Chua N.H. (2006). Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana using the floral dip method. Nat. Protoc. 1: 641–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X., Jiang Y., Yu D. (2011). WRKY22 transcription factor mediates dark-induced leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. Mol. Cells 31: 303–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.