Summary

Inhibition of the type I IGF receptor (IGF1R) has been the focus of numerous clinical trials. Two reports in this issue describe the results of phase I trials of an IGF1R tyrosine kinase inhibitor OSI-906. This commentary will describe the complex endocrine changes induced by these types of agents.

In this issue of Clinical Cancer Research, two phase I studies of the type I IGF receptor and insulin receptor inhibitor OSI-906 are presented (1, 2). In A Tale of Two Cities, Charles Dickens wrote, “we had everything before us, we had nothing before us”. This phrase describes the past several years in the development of the type I insulin-like growth factor receptor (IGF1R) inhibitors. Fueled by abundant preclinical and population data implicating IGF1R in cancer biology, strategies to target this transmembrane tyrosine kinase inhibitor were developed. A burst of clinical trials involving at least five monoclonal antibodies (moAbs) and three tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) directed against IGF1R were planned and completed.

To date, the development of the IGF1R moAbs has largely ended. While there was some evidence of single agent activity, the majority of combination therapy trials were failures (reviewed in 3). Initially, the most promising published phase II report of IGF1R combination therapy in non-small cell lung cancer was retracted due to errors in determining response. The recently reported phase III trials showed a trend toward harm for patients receiving chemotherapy and the IGF1R monoclonal antibody (moAb) figitumumab (4).

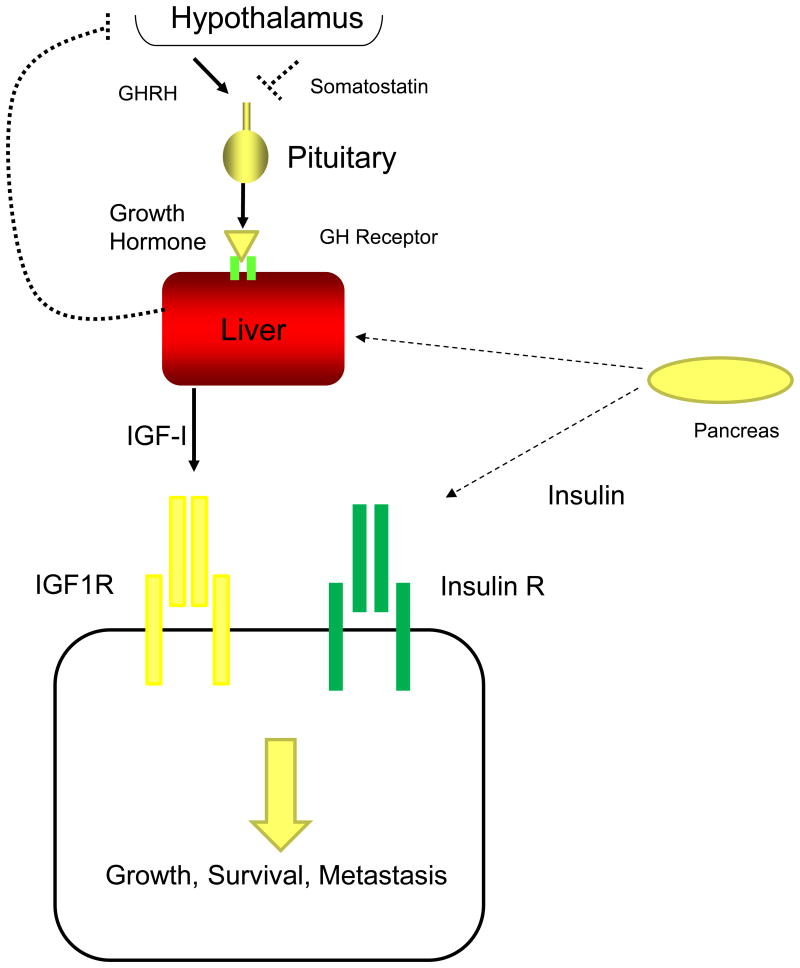

Was IGF1R the right target? As the name suggests, “insulin-like” growth factors are highly related to insulin (Figure 1A). Both the ligands and receptors have significant homology, yet we have tended to think of the two ligand and receptor systems as having separate physiologic roles. Insulin's role in glucose homeostasis is well understood. IGF-I regulates growth; it is produced at the time of puberty in response to pituitary release of growth hormone (GH). Thus, these two highly regulated endocrine systems have been linked to metabolism (insulin) and growth (IGF-I), but it is clear the two systems overlap in their physiologic functions. IGF-I clearly has metabolic functions and has been used to treat type 2 diabetes (5). Insulin enhances tumor growth in animal models of type 2 diabetes (6). In the development of the IGF1R moAbs, there was an intentional effort to avoid cross-reactivity with the insulin receptor in order to maintain glucose homeostasis.

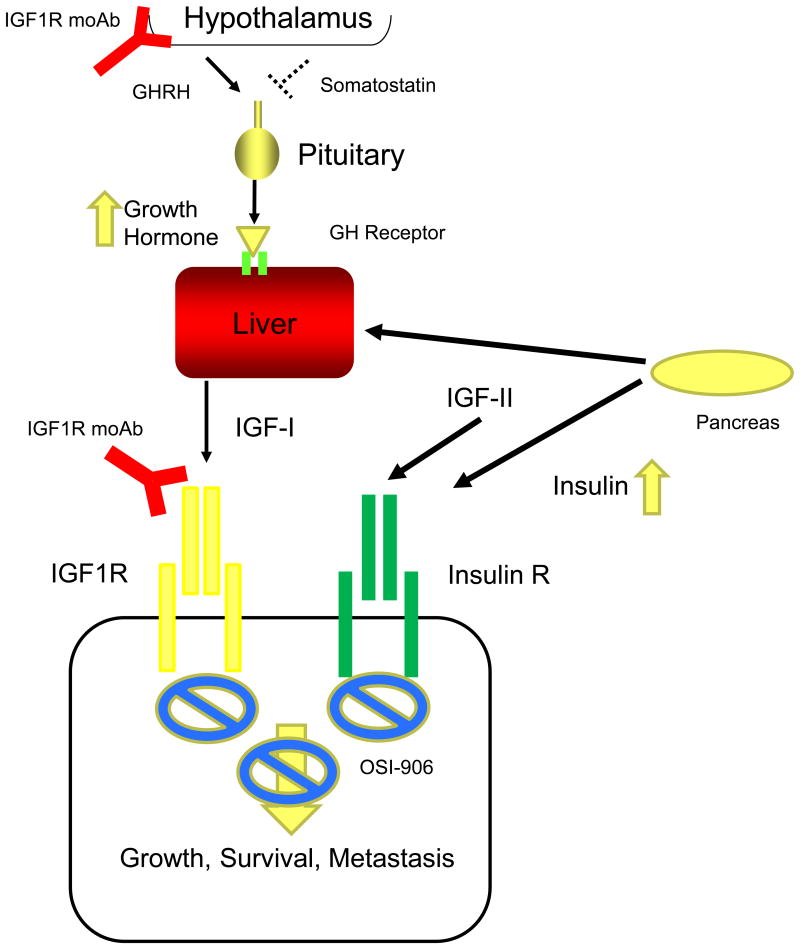

Figure 1.

Coordination of IGF-I and insulin signaling. A, In normal conditions, the hypothalamus produces Growth Hormone Releasing Hormone (GHRH) and Somatostatin to regulate Growth Hormone production by the pituitary. Growth Hormone interacts with Growth Hormone receptor in the liver resulting in increased serum levels of IGF-I. IGF-I stimulates growth in normal cells by stimulating IGF1R, but also regulates cancer cell growth, survival and metastasis. Insulin produced by the pancreas interacts with several tissues to maintain glucose homeostatsis including the liver. While most cancer cells also express insulin receptor and under normal physiologic conditions, insulin levels are low (dotted lines) except in response to a meal. IGF-II is produced from many different tissues and binds both receptors.

B, When IGF1R signaling is disrupted by a monoclonal antibody (red symbol), negative endocrine Growth Hormone feedback is disrupted as the brain does not sense IGF-I levels. Elevated Growth Hormone (orange arrow) levels result in insulin resistance (partially due to increased free fatty acid efflux from the liver) in peripheral tissues resulting in enhanced insulin production by the pancreas (thick lines, orange arrow). These elevated insulin levels may stimulate tumor growth. OSI-906 is not specific for insulin or IGF signaling and may be a more effective drug to block both IGF-I, IGF-II, and insulin signaling than IGF1R monoclonal antibodies.

It was well understood in the early development of IGF1R moAbs insulin and glucose homeostasis was also disrupted with this class of drugs. Phase I trials with figitumumab demonstrated increased levels of growth hormone, IGF-I, insulin, and glucose (7). Figure 1B demonstrates how this occurs. IGF1R moAbs block the endocrine feedback system regulating the production of IGF-I. When patients receive IGF1R moAbs, GH levels increase because the antibodies disrupt the brain's ability to sense the levels of IGF-I. This disruption of a pituitary endocrine system is exactly analogous to pre-menopausal women receiving tamoxifen. When estrogen receptor-α (ER) is inhibited by tamoxifen, blood levels of estradiol increase because of the disruption of the feedback system (8). However, tamoxifen is still effective in pre-menopausal women with functioning ovaries because the estradiol/ER interaction is effectively inhibited despite the elevation of blood estradiol.

This is not the case in IGF1R moAb therapy. First, supraphysiologic levels of IGF-I induced by the antibody might be able to stimulate the insulin receptor. Indeed, insulin receptor can be stimulated by IGF ligands. The IGFs exist in two isoforms; IGF-II is structurally related to IGF-I and interacts with insulin receptor with high affinity. Supraphysiologic concentrations of IGF-I may also stimulate insulin receptor. Second, elevated levels of GH result in insulin resistance and elevated levels of insulin (9). IGF-II, a homologous ligand to IGF-I is also found in adult human blood and has high affinity for the insulin receptor (3). Thus, IGF1R moAbs could result in harm via the elevation of ligands stimulating insulin receptor while leaving the insulin receptor uninhibited. Indeed, we have shown sole inhibition of IGF1R results in enhanced signaling through insulin receptor (10). These data would argue disruption of both receptors would be necessary for tumor growth inhibition.

Fortunately, the tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) are biochemical inhibitors of both receptors' kinase function. Given the high degree of homology of the two receptors, an “IGF1R” specific TKI has not been possible to develop; existing drugs inhibit both receptors equally. In this issue, the results of two phase I studies of the IGF1R TKI OSI-906 are reported. The first of these reports studied an intermittent dosing regimen; 3 or 7 daily doses out of a 14 day cycle. There are potentially several reasons for the benefit of intermittent dosing including a reduction in toxicity. In addition, preclinical data suggest continuous suppression of IGF1R signaling might not be the best strategy to combine with chemotherapy (11, 12). The other report used continuous daily dosing. Both studies reported hyperglycemia, but there was a slightly lower incidence in the intermittent dosing schedules. Conversely, nausea was slightly higher when given intermittently.

The continuous dosing regimen also included a cohort with type 2 diabetes. Mouse models of type 2 diabetes showed a TKI inhibited tumor growth in these diabetic animals (6). In this study, there was a modest further elevation of glucose which was also seen in this human study. Notably, marked elevations of serum insulin in these diabetic animals were seen as an endocrine response to further insulin resistance. Insulin levels in the human phase I trials were not reported.

All of the regimens demonstrated evidence of clinical benefit as reflected by disease control rates (percent of patients with stable disease compared to total number of patients) of about 40%. While objective responses were rare, a number of patients achieved more than 6 months of disease stability. In the intermittent dosing study, 7 of 66 evaluable patients had stability for more than 6 months. For the continuous dosing regimen, 2 of 30 patients remained on therapy for more than 39 weeks. Remarkably, a patient with metastatic melanoma achieved a pathological complete response on the continuous regimen. The authors conclude that OSI-906, as a single agent, has activity in cancer and the intermittent regimens suggest the potential for combination therapy.

These promising phase I results suggest a role for the dual tyrosine kinase inhibition of insulin and IGF1R. This dual inhibition may overcome the potential limitation of elevated serum levels after IGF1R moAb therapy. While hyperinsulinemia was very likely in the OSI-906 treated patients, the drug can suppress any physiologic effects of insulin on tumor cells as shown in the mouse models of hyperinsulinemia (6).

While the overall response rate was low for this therapy, it is remarkable any responses were documented in this phase I study in the absence of biomarker selection. While we believe we understand the targets for this dual kinase inhibitor, we have not been successful in identifying cancers dependent upon insulin/IGF signaling. Notably, insulin and IGF1R activation require ligand binding and it has been suggested serum levels of the ligands might play a role in predicting response to an IGF1R moAb (13). This study did not measure serum insulin levels and future studies should measure this other ligand when developing predictive biomarkers.

In the end, the failure of the IGF1R moAbs have shed light onto the putative importance of insulin receptor signaling in cancer. In A Tale of Two Cities two very similar appearing men with different properties are the focus of the story. In this novel, Sydney Carton dies in order to save Charles Darnay. Perhaps the “death” of IGF1R moAbs could pave a way forward for the IGF1R/insulin receptor TKIs.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: This work was supported by the NCI of the NIH under award numbers P30CA077598 and P50CA116201, and a Susan G. Komen research grant (SAC110039).

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest: No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Jones RL, Kim ES, Nava-Parada P, Alam S, Johnson FM, Stephens AW, et al. Phase I study of intermittent oral dosing of the insulin-like growth factor-1 and insulin receptors inhibitor OSI-906 in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 21:xxx–xxx. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Puzanov I, Lindsay CR, Goff L, Sosman J, Gilbert J, Berlinn J, et al. A Phase I study of continuous oral cosing of OSI-906, a dual inhibitor of insulin-like growth factor-1 and insulin receptors in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 21:xxx–xxx. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yee D. Insulin-like growth factor receptor inhibitors: baby or the bathwater? J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:975–81. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Langer CJ, Novello S, Park K, Krzakowski M, Karp DD, Mok T, et al. Randomized, phase III trial of first-line figitumumab in combination with paclitaxel and carboplatin versus paclitaxel and carboplatin alone in patients with advanced non–small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2059–66. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.4932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clemmons DR. Metabolic actions of insulin-like growth factor-I in normal physiology and diabetes. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2012;41:425–43. viii. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2012.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Novosyadlyy R, Lann DE, Vijayakumar A, Rowzee A, Lazzarino DA, Fierz Y, et al. Insulin-mediated acceleration of breast cancer development and progression in a nonobese model of type 2 diabetes. Cancer Res. 2010;70:741–51. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haluska P, Shaw HM, Batzel GN, Yin D, Molina JR, Molife LR, et al. Phase I dose escalation study of the anti insulin-like growth factor-I receptor monoclonal antibody CP-751,871 in patients with refractory solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:5834–40. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ravdin PM, Fritz NF, Tormey DC, Jordan VC. Endocrine status of premenopausal node-positive breast cancer patients following adjuvant chemotherapy and long-term tamoxifen. Cancer Res. 1988;48:1026–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vijayakumar A, Novosyadlyy R, Wu Y, Yakar S, LeRoith D. Biological effects of growth hormone on carbohydrate and lipid metabolism. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2010;20:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ghir.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang H, Pelzer AM, Kiang DT, Yee D. Down-regulation of type I insulin-like growth factor receptor increases sensitivity of breast cancer cells to insulin. Cancer Res. 2007;67:391–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zeng X, Sachdev D, Zhang H, Gaillard-Kelly M, Yee D. Sequencing of type I insulin-like growth factor receptor inhibition affects chemotherapy response in vitro and in vivo. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:2840–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zeng X, Zhang H, Oh A, Zhang Y, Yee D. Enhancement of doxorubicin cytotoxicity of human cancer cells by tyrosine kinase inhibition of insulin receptor and type I IGF receptor. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;133:117–26. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1713-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCaffery I, Tudor Y, Deng H, Tang R, Suzuki S, Badola S, et al. Putative predictive biomarkers of survival in patients with metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma treated with gemcitabine and ganitumab, an IGF1R inhibitor. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:4282–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]