Abstract

Background:

This study aimed to investigate the additive effects of socio-economic factors, number of psychiatric disorders, and religiosity on suicidal ideation among Blacks, based on the intersection of ethnicity and gender.

Methods:

With a cross-sectional design, data came from the National Survey of American Life, 2001–2003, which included 3570 African-American and 1621 Caribbean Black adults. Socio-demographics, perceived religiosity, number of lifetime psychiatric disorders and lifetime suicidal ideation were measured. Logistic regressions were fitted specific to groups based on the intersection of gender and ethnicity, while socioeconomics, number of life time psychiatric disorders, and subjective religiosity were independent variables, and lifetime serious suicidal ideation was the dependent variable.

Results:

Irrespective of ethnicity and gender, number of lifetime psychiatric disorders was a risk factor for lifetime suicidal ideation (odds ratio [OR] ranging from 2.4 for Caribbean Black women to 6.0 for Caribbean Black men). Only among African-American men (OR = 0.8, 95% confidence interval = 0.7–0.9), perceived religiosity had a residual protective effect against suicidal ideation above and beyond number of lifetime psychiatric disorders. The direction of the effect of education on suicidal ideating also varied based on the group.

Conclusions:

Residual protective effect of subjective religiosity in the presence of psychiatric disorders on suicidal ideation among Blacks depends on ethnicity and gender. African-American men with multiple psychiatric disorders and low religiosity are at very high risk for suicidal ideation.

Keywords: African-Americans, ethnic groups, gender, psychiatric disorder, religion and psychology, suicide

INTRODUCTION

Demographic and socio-economic factors,[1,2,3] psychiatric disorders,[4,5,6,7] and low religiosity[8,9,10,11,12] all have separate effects on suicidal ideation and behaviors. Low socio-economic status indicated by poverty, low education level, single status, and unemployment increases the risk of suicide.[1,2,3] The presence of psychiatric disorders also increases the risk of suicidal ideation and behaviors.[4,5,6,7] Individuals with low religious involvement are also at high risk for suicide.[8,9,10,11,12]

Suicidal ideation and behaviors vary across ethnic groups.[13,14,15,16] Braun et al. argued that suicide variation among ethnic groups may have roots in multiple factors such as culture, life values, and socio-historical experiences.[17] Although racial and ethnic difference in the epidemiology of suicide is known,[18] less is known about ethnic differences in the effects of risk and protective factors on suicide.[19,20] Thus, there is a need to study racial and ethnic variations in vulnerability and resilience to the effect of risk and protective factors such as socio-economics, psychiatric disorders, and religiosity.

Possibly because of lower rates of suicide compared to Whites, few studies have focused on risk and protective factors of suicidality among Blacks.[21,22] Among Blacks in the United States, number of lifetime psychiatric disorders lowers the age of suicidal ideation while subjective religiosity delays the initiation of suicidal thoughts. Interestingly, the effect of psychiatric disorders on the age of onset of suicidal ideation is dose dependent, and the effect of multiple psychiatric disorders on suicidal ideation is most pronounced among those with low religiosity.[23] Among Blacks, low education, residing in the Midwest, and having one or more psychiatric disorders contribute to increase in risk of suicidal attempts.[24]

Among Blacks, ethnicity changes the distribution of suicidal behaviors, as African-Americans may attempt suicide more than Caribbean Blacks.[25] In 2011, Taylor et al. studied differences in the association between certain measures of religiosity and suicidality among African-Americans versus Caribbean Blacks. For instance, among Caribbean Blacks, subjective religiosity, looking to God for strength, and comfort and guidance were protective against suicidal attempts and ideation. These associations could not be found among African-Americans.[18]

This study aimed to investigate if the additive effects of socio-economic factors, number of psychiatric disorders, and subjective religiosity on lifetime serious suicidal ideation among Blacks vary based on the intersection of ethnicity and gender.

METHODS

Study design and participants

Data came from the National Survey of American Life (NSAL), which was conducted as a part of the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys, 2003. The NSAL included 3570 African-American and 1621 Caribbean Black adults. The study was funded by National Institute of Mental Health.

African-Americans were composed of individuals that self-identified as Black, but did not report Caribbean ancestry. Individuals that self-identified as Black were considered Caribbean Blacks, if they met at least one of the following criteria: (a) Being of West Indian or Caribbean descent, (b) being from a Caribbean country, or (c) having parents or grandparents that were born in a Caribbean country.[26]

African-American samples, being the largest portion of NSAL, were selected from 48 neighboring states and included households that contained at least one Black adult. The Caribbean Black sample included 265 samples that were collected from households within the core sample. The remaining samples were collected from households within geographic areas that had a high Caribbean population.[27] Caribbean Blacks were sampled from residential areas that reflect the distribution of the African-American population and from additional metropolitan areas where Caribbean Blacks composed more than 10% of the population.[26]

Study instruments and variables assessment

Age, education level (less than high school, high school graduate, some college, college graduate), marital status (married, previously married, never married), and region (Northeast, Midwest, South, and West Census regions) were measured as controls. Ethnicity (African-American and Caribbean Black) and gender were moderators.

Subjective religiosity

Subjective religiosity is one of the dimensions of religious involvement and is defined as the subjective perception of and attitude toward religion.[28] It can be measured by questions regarding the perceived importance of religion, the role of religious beliefs in one's life, and one's perception of being religious.[29] This dimension is nonbehavioral, as opposed to organizational and nonorganizational religiosity.[30,31] Measures of subjective religiosity have been validated using structural equation modeling procedures among Blacks.[30]

In this study, subjective religiosity was measured using two items: (1) How religious are you? and (2) How spiritual are you? Responses to the first question included: Not religious at all, not too religious, fairly religious, and very religious. Responses to the second question included: Not spiritual at all, not too spiritual, fairly spiritual, and very spiritual. The total score varied from 0 to 6 with a higher score indicating higher subjective religiosity.

Psychiatric disorders

World Mental Health Composite International Diagnostic Interview was used to measure number of lifetime psychiatric disorders based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), Fourth Edition. Psychiatric disorders were classified as: Mood disorders (i.e., major depressive disorder, dysthymia, bipolar I and II disorders); anxiety disorders (i.e., panic disorder, agoraphobia, social phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder); substance use disorders (i.e. alcohol abuse, alcohol dependence, drug abuse, drug dependence); disorders usually diagnosed in childhood (i.e. separation anxiety disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder), and eating disorders (i.e., anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge-eating disorder).[26]

Main outcome

Lifetime serious suicidal ideation was measured using the following single item: Have you ever seriously thought about suicide? Other questions related to suicide were also asked but were not included in this analysis.[18,19,20,24,25]

Statistical analysis

To handle the complex sampling design of the NSAL, Stata 12.0 (StataCorp, TX, USA) was used for data analysis. We estimated standard errors based on the Taylor series linearization to account for the clustered nature of the data. Subpopulation survey logistic regression was used for all inferences. Multicollinearity between the independent variables was ruled out.[32] Odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported. ORs larger than one indicated a positive association between exposure and outcome. P < 0.05 were considered significant. Missing data were not imputed.

RESULTS

Among Blacks, about 44.4% of the participants were male with a mean age of 42.2 (SE = 0.49) years. From all Blacks, 69.3% (95% CI = 67.2–71.3) did not meet criteria for any lifetime psychiatric disorders, 21.8% (95% CI = 20.2–23.4) met criteria for one psychiatric disorder and 8.9% (95% CI = 7.6–10.1) met criteria for at least two psychiatric disorders. 11.7% (95% CI = 10.1–13.4) of all participants had seriously thought about suicide since the mean age of 28.5 years (95% CI = 27.3–29.7).

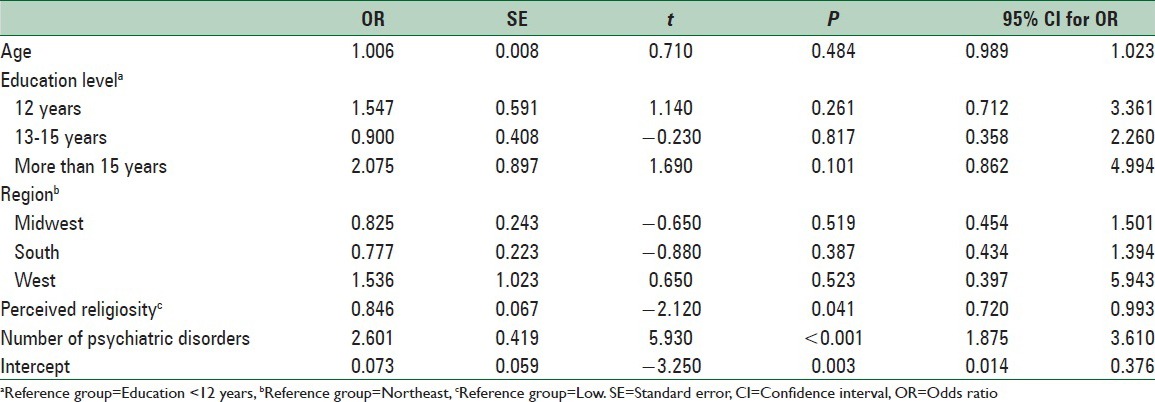

Among African-American men, perceived religiosity and number of psychiatric disorders were associated with lifetime suicidal ideation. In this group, age, education, and country region were not associated with suicidal ideation [Table 1].

Table 1.

Association between socio-economic status, number of psychiatric disorders, perceived religiosity, and suicidal ideation among African-American men

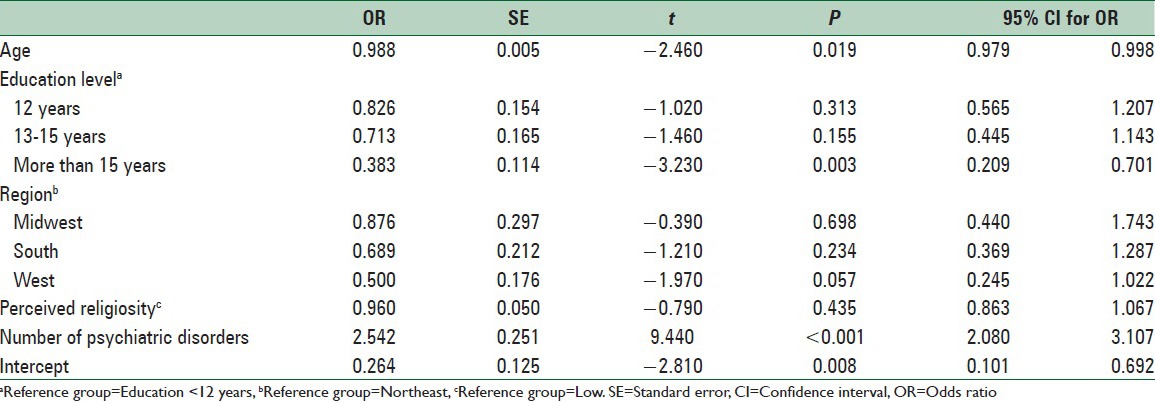

Among African-American women, age, education, and number of psychiatric disorders were associated with lifetime suicidal ideation. In this group, perceived religiosity and country region were not associated with lifetime suicidal ideation [Table 2].

Table 2.

Association between socio-economic status, number of psychiatric disorders, perceived religiosity, and suicidal ideation among African-American women

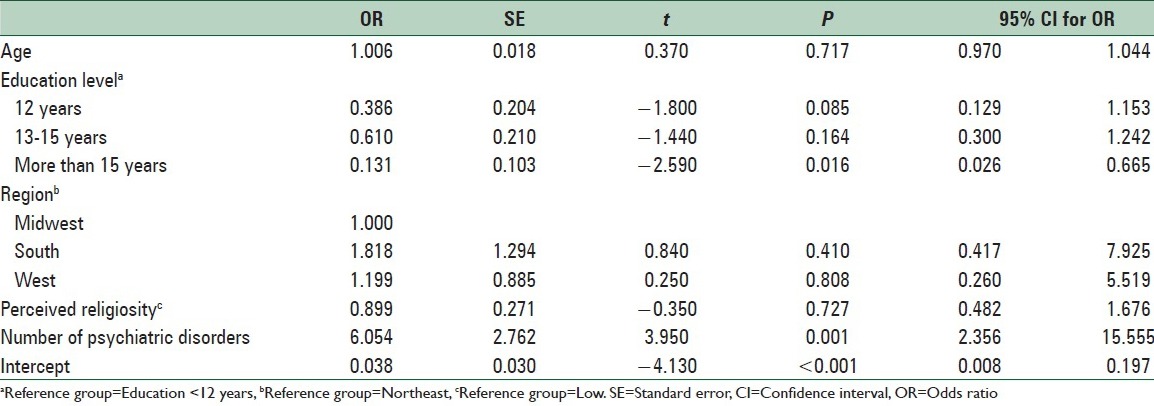

Among Caribbean Black men, education, and number of psychiatric disorders were associated with lifetime suicidal ideation. In this group, age, perceived religiosity, and country region were not associated with lifetime suicidal ideation [Table 3].

Table 3.

Association between socio-economic status, number of psychiatric disorders, perceived religiosity, and suicidal ideation among Caribbean Black men

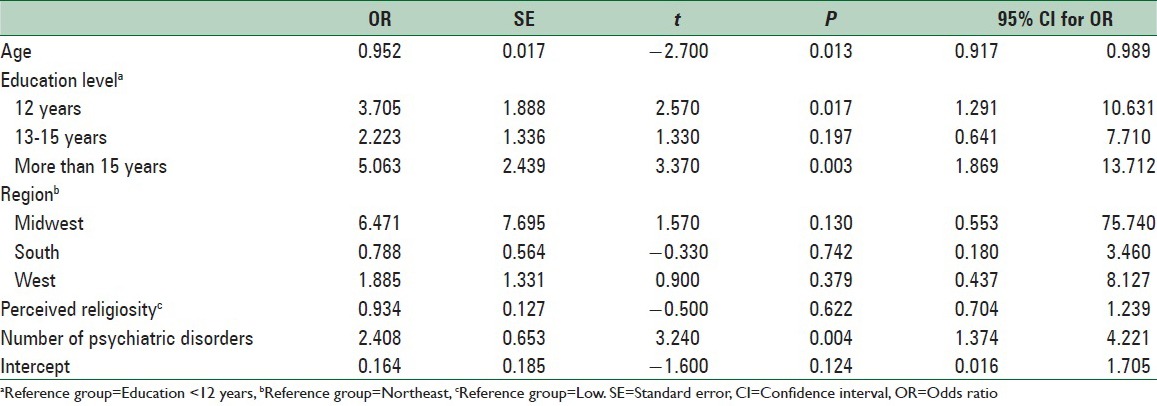

Among Caribbean Black women, age, education, and number of psychiatric disorders were associated with lifetime suicidal ideation. In this group, perceived religiosity and country region were not associated with lifetime suicidal ideation [Table 4].

Table 4.

Association between socio-economic status, number of psychiatric disorders, perceived religiosity, and suicidal ideation among Caribbean Black women

DISCUSSION

Our study showed that after adjustment for the effect of socio-economic status and number of lifetime psychiatric disorders, subjective religiosity protected African-American men against serious suicidal thoughts. Such an effect was not found among Caribbean Black men or women or African-American women.

After controlling the effect of type of psychiatric disorders, Taylor et al. (2011) showed major differences between African-Americans and Caribbean Blacks for the association between various domains of religiosity and suicidal behaviors. Their study showed that some indicators of religiosity were negatively associated with suicidal ideation and attempt; however, there were also positive associations between some aspects of religiosity and suicidality among Caribbean Blacks. Authors argued that there is a need for further qualitative and quantitative research to understand reasons for the differences in these associations across ethnic groups.[31]

In another study, African-Americans and Caribbean Blacks were shown to be very different in additive effects of five psychiatric disorders on suicidal ideation. Among African-Americans, major depressive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder and alcohol abuse disorder were associated with higher odds of suicidal thoughts, while among Caribbean Blacks, major depressive disorder and drug abuse disorder were associated with higher odds of suicidal ideation.[33]

Based on the current study and also previous studies,[18,19,20,34] the additive effects of risk and protective factors of suicidality of Blacks depend on their ethnicity. Our study showed that religiosity is a protective factor with differential effects that depend on the intersection of ethnicity and gender. Although multiple psychiatric disorders are always a risk factor, different types of psychiatric disorders may contribute to the suicide of African-Americans and Caribbean Blacks. This finding is beyond the previous knowledge on the main effects of ethnicity on suicidal ideation among Blacks.[25]

Findings of the current study shed more light on the complex link between race and ethnicity, gender, socio-economic status, psychiatric disorders, religiosity, and suicidal behaviors. Assari had previously shown that the effect of psychiatric disorders among Blacks may be more pronounced among those who report low subjective religiosity. Based on that study, number of psychiatric disorders has a dose-dependent effect on suicidal ideation, with the highest number of comorbid psychiatric disorders having a very strong cumulative effect on suicidal ideation.[23]

Among Blacks, the effect of psychiatric disorders on the age of suicidal ideation may be a dose-response relation.[23] Other studies have also confirmed the dose-response in the effect of number of psychiatric disorders and suicidal behaviors.[35,36,37] In a study by Kessler et al., number of psychiatric disorders was the strongest predictor of suicidal attempt in the population.[38] According to our study, the effect of each additional psychiatric disorder on suicidal ideation is highest for Caribbean Black men (OR = 6.0) and lowest for Caribbean Black women (OR = 2.4).

Although not all,[39] most studies[23,40,41,42] have shown a higher prevalence of suicidal ideation among women.[23] Gender differences in suicidal thought have been partially attributed to social norms and gender expectations.[43] Compared to men, women report more suicidal thoughts but do not act on thoughts (low suicidal attempt).[44] Most studies, however, have focused on the main effects of gender on suicidality,[45,46,47] and our knowledge is very limited on the moderating effect of intersection of gender and ethnicity on factors that contribute to suicide.[48]

Gender differences in suicidality have not been explained by differential exposure to the risk factors.[49] To test the differential vulnerability hypothesis based on gender, a Danish study compared 811 suicide cases with 79,871 controls and showed that unemployment, retirement, being single and sickness absence from work were risk factors for men, while having a young child was protective for women. History of hospitalization due to psychiatric disorder was the most strong suicide risk factor among both genders. The magnitude of the association between suicide and psychiatric admission status also differed between genders.[49]

Based on our results, programs on screening, diagnosis, prevention or treatment of suicidal ideation among Blacks may benefit from tailoring based on ethnicity and gender.[50] Although screening and treatment of psychiatric disorders among Blacks seem crucial across all gender and ethnic groups, African-American men may need additional evaluation if less religious. Suicidal prevention programs may need to reach African-American men with multiple psychiatric disorders and low religiosity. Universal diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric disorders is, however, essential for all gender and ethnic groups of Blacks.

In this study, groups based on the intersection of ethnicity and gender were very different in additive effects of known determinants of suicidal ideation. The moderating effect of race, ethnicity, gender, social class, and other contextual factors on the associations between risk and protective factors and outcomes has been shown for other risk factors and outcomes.[51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62] We, however, still do not know how contextual factors such as gender and ethnicity modify the additive effects of a risk and protective factor, even when separate effects of the same risk and protective factors are constant.[34,51,52,57,58,63,64,65]

This study had a few limitations. Due to the cross-sectional design, causative associations are not plausible. In addition, as this study relied on self-reports, under-reporting of suicidal ideation cannot be ruled out. Moreover, ethnic and gender differences in the validity of the measures of suicidality and religiosity are not known. In addition, statistical power was not identical in different groups of this study. Furthermore, we also did not include any measure of behavioral religiosity. Finally, Caribbean Blacks in this study were composed of a heterogenic group based on nativity and time lived in the USA.

CONCLUSIONS

Based on our findings, while the effect of number of psychiatric disorders is constant across ethnic and gender groups of Blacks, subjective religiosity may only protect African-American men against suicidal ideation. Subjective religiosity may not have a protective effect above and beyond number of psychiatric disorders among African-American women, or Caribbean Black men or women. The direction of the association between education level and suicidal ideation also vary based on the intersection of ethnicity and gender.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nordentoft M. Prevention of suicide and attempted suicide in Denmark. Epidemiological studies of suicide and intervention studies in selected risk groups. Dan Med Bull. 2007;54:306–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Qin P, Agerbo E, Westergård-Nielsen N, Eriksson T, Mortensen PB. Gender differences in risk factors for suicide in Denmark. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:546–50. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.6.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agerbo E, Nordentoft M, Mortensen PB. Familial, psychiatric, and socioeconomic risk factors for suicide in young people: Nested case-control study. BMJ. 2002;325:74. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7355.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.King E. Suicide in the mentally ill. An epidemiological sample and implications for clinicians. Br J Psychiatry. 1994;165:658–63. doi: 10.1192/bjp.165.5.658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alexopoulos GS, Bruce ML, Hull J, Sirey JA, Kakuma T. Clinical determinants of suicidal ideation and behavior in geriatric depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:1048–53. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.11.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Legleye S, Beck F, Peretti-Watel P, Chau N, Firdion JM. Suicidal ideation among young French adults: Association with occupation, family, sexual activity, personal background and drug use. J Affect Disord. 2010;123:108–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agerbo E, Nordentoft M, Mortensen PB. Suicide among young people – Familial, psychiatric and socioeconomic risk factors. A nested case-control study. Ugeskr Laeger. 2002;164:5786–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stack S, Lester D. The effect of religion on suicide ideation. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1991;26:168–70. doi: 10.1007/BF00795209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Durkheim E. Spaulding JA, Simpson G. Illinois: Free Press; 1951. Suicide – A Study in Sociology. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pescosolido BA, Georgianna S. Durkheim, suicide, and religion: Toward a network theory of suicide. Am Sociol Rev. 1989;54:33–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dervic K, Oquendo MA, Grunebaum MF, Ellis S, Burke AK, Mann JJ. Religious affiliation and suicide attempt. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:2303–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clarke CS, Bannon FJ, Denihan A. Suicide and religiosity – Masaryk's theory revisited. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2003;38:502–6. doi: 10.1007/s00127-003-0668-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morris P, Maniam T. Ethnicity and suicidal behaviour in Malaysia: A review of the literature. Transcult Psychiatry. 2001;38:51–62. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ko SM, Kua EH. Ethnicity and elderly suicide in Singapore. Int Psychogeriatr. 1995;7:309–17. doi: 10.1017/s1041610295002067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kua EH, Ko SM, Ng TP. Recent trends in elderly suicide rates in a multi-ethnic Asian city. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;18:533–6. doi: 10.1002/gps.868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Assari S. Synergistic effects of lifetime psychiatric disorders on suicidal ideation among Blacks in the USA. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2014;1:275–82. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Braun KL, Tanji VM, Heck R. Support for physician-assisted suicide: Exploring the impact of ethnicity and attitudes toward planning for death. Gerontologist. 2001;41:51–60. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Joe S. Religious involvement and suicidal behavior among African Americans and Black Caribbeans. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2011;199:478–86. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31822142c7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chatters LM, Taylor RJ, Lincoln KD, Nguyen A, Joe S. Church-based social support and suicidality among African Americans and Black Caribbeans. Arch Suicide Res. 2011;15:337–53. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2011.615703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheref S, Lane R, Polanco-Roman L, Gadol E, Miranda R. Suicidal ideation among racial/ethnic minorities: Moderating effects of rumination and depressive symptoms. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2015;21:31–40. doi: 10.1037/a0037139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anglin D, Gabriel K, Kaslow N. Suicide acceptability and religious well-being: A comparative analysis in African American suicide attempters and non-attempters. J Psychol Theol. 2005;33:140–50. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lichtenstein RL, Alcser KH, Corning AD, Bachman JG, Doukas DJ. Black/white differences in attitudes toward physician-assisted suicide. J Natl Med Assoc. 1997;89:125–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Assari S, Lankarani MM, Moazen B. Religious Beliefs May Reduce the Negative Effect of Psychiatric Disorders on Age of Onset of Suicidal Ideation among Blacks in the United States. Int J Prev Med. 2012;3:358–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Joe S, Baser RE, Breeden G, Neighbors HW, Jackson JS. Prevalence of and risk factors for lifetime suicide attempts among Blacks in the United States. JAMA. 2006;296:2112–23. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.17.2112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joe S, Baser RS, Neighbors HW, Caldwell CH, Jackson JS. 12-month and lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts among Black adolescents in the National Survey of American Life. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48:271–82. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318195bccf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williams DR, Haile R, González HM, Neighbors H, Baser R, Jackson JS. The mental health of Black Caribbean immigrants: Results from the National Survey of American Life. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:52–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.088211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jackson JS, Torres M, Caldwell CH, Neighbors HW, Nesse RM, Taylor RJ, et al. The National Survey of American Life: A study of racial, ethnic and cultural influences on mental disorders and mental health. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:196–207. doi: 10.1002/mpr.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eliassen AH, Taylor J, Lloyd DA. Subjective Religiosity and Depression in the Transition to Adulthood. J Sci Study Relig. 2005;44:187–99. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chatters LM, Levin JS, Taylor RJ. Antecedents and dimensions of religious involvement among older Black adults. J Gerontol. 1992;47:S269–78. doi: 10.1093/geronj/47.6.s269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levin JS, Chatters LM, Taylor RJ. Religious effects on health status and life satisfaction among Black Americans. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1995;50:S154–63. doi: 10.1093/geronb/50b.3.s154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taylor RJ, Mattis J, Chatters LM. Subjective religiosity among African-Americans: A synthesis of findings from five national samples. J Black Psychol. 1999;25:524–43. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nick TG, Campbell KM. Logistic regression. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;404:273–301. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-530-5_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stack S. The effect of religious commitment on suicide: A cross-national analysis. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:362–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Assari S, Lankarani MM, Lankarani RM. Ethnicity Modifies the Additive Effects of Anxiety and Drug Use Disorders on Suicidal Ideation among Black Adults in the United States. Int J Prev Med. 2013;4:1251–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mościcki EK, O’Carroll P, Rae DS, Locke BZ, Roy A, Regier DA. Suicide attempts in the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study? Yale J Biol Med. 1988;61:259–68. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR. Adolescent suicidal ideation and attempts: Prevalence, risk factors, and clinical implications. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 1996;3:25–46. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Petronis KR, Samuels JF, Moscicki EK, Anthony JC. An epidemiologic investigation of potential risk factors for suicide attempts. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1990;25:193–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00782961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kessler RC, Borges G, Walters EE. Prevalence of and risk factors for lifetime suicide attempts in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:617–26. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.7.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang J. Suicides in Beijing, China, 1992-1993. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1996;26:175–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beck AT, Lester D, Kovacs M. Attempted suicide by males and females. Psychol Rep. 1973;33:965–6. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1973.33.3.965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sanborn CJ. Gender socialization and suicide: American Association of Suicidology presidential address, 1989. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1990;20:148–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ang RP, Ooi YP. Impact of gender and parents’ marital status on adolescents’ suicidal ideation. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2004;50:351–60. doi: 10.1177/0020764004050335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murphy GE. Why women are less likely than men to commit suicide. Compr Psychiatry. 1998;39:165–75. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(98)90057-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Langhinrichsen-Rohling J. A Gendered Analysis of Sex Differences in Suicide-Related Behaviors: A National (U.S.) and International Perspective World Health Organization. [Last accessed on 2015 Jan]. Available from: http://www.who.int/gender-equity-rights/en/

- 45.Hawton K. Sex and suicide. Gender differences in suicidal behaviour. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:484–5. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.6.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Qin P, Agerbo E, Westergård-Nielsen N, Eriksson T, Mortensen PB. Gender differences in risk factors for suicide in Denmark. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:546–50. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.6.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hur JW, Lee BH, Lee SW, Shim SH, Han SW, Kim YK. Gender differences in suicidal behavior in Korea. Psychiatry Investig. 2008;5:28–35. doi: 10.4306/pi.2008.5.1.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gore JC. Neuroimaging X. Functional MRI studies of language by sex. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:860. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.7.860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Qin P, Agerbo E, Westergård-Nielsen N, Eriksson T, Mortensen PB. Gender differences in risk factors for suicide in Denmark. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:546–50. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.6.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cummings JR, Ponce NA, Mays VM. Comparing racial/ethnic differences in mental health service use among high-need subpopulations across clinical and school-based settings. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46:603–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.11.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Assari S. Additive Effects of Anxiety and Depression on Body Mass Index among Blacks: Role of Ethnicity and Gender. Int Cardiovasc Res J. 2014;8:44–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Assari S. Chronic Medical Conditions and Major Depressive Disorder: Differential Role of Positive Religious Coping among African Americans, Caribbean Blacks and Non-Hispanic Whites. Int J Prev Med. 2014;5:405–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Assari S. Separate and Combined Effects of Anxiety, Depression and Problem Drinking on Subjective Health among Black, Hispanic and Non-Hispanic White Men. Int J Prev Med. 2014;5:269–79. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Assari S. The link between mental health and obesity: Role of individual and contextual factors. Int J Prev Med. 2014;5:247–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Assari S, Ahmadi K, Kazemi Saleh D. Gender Differences in the Association between Lipid Profile and Sexual Function among Patients with Coronary Artery Disease. Int Cardiovasc Res J. 2014;8:9–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Assari S, Moghani Lankarani M, Kazemi Saleh D, Ahmadi K. Gender modifies the effects of education and income on sleep quality of the patients with coronary artery disease. Int Cardiovasc Res J. 2013;7:141–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Assari S, Lankarani MM, Lankarani RM. Ethnicity Modifies the Additive Effects of Anxiety and Drug Use Disorders on Suicidal Ideation among Black Adults in the United States. Int J Prev Med. 2013;4:1251–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Assari S. Race and Ethnicity, Religion Involvement, Church-based Social Support and Subjective Health in United States: A Case of Moderated Mediation. Int J Prev Med. 2013;4:208–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kazemi-Saleh D, Pishgou B, Farrokhi F, Assari S, Fotros A, Naseri H. Gender impact on the correlation between sexuality and marital relation quality in patients with coronary artery disease. J Sex Med. 2008;5:2100–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kazemi-Saleh D, Pishgoo B, Farrokhi F, Fotros A, Assari S. Sexual function and psychological status among males and females with ischemic heart disease. J Sex Med. 2008;5:2330–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Khooshabi K, Ameneh-Forouzan S, Ghassabian A, Assari S. Is there a gender difference in associates of adolescents’ lifetime illicit drug use in Tehran, Iran? Arch Med Sci. 2010;6:399–406. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2010.14263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mohammadkhani P, Forouzan AS, Khooshabi KS, Assari S, Lankarani MM. Are the predictors of sexual violence the same as those of nonsexual violence. A gender analysis? J Sex Med. 2009;6:2215–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Assari S, Smith JR, Caldwell CH, Zimmerman MA. Gender Differences in Longitudinal Links between Neighborhood Fear, Parental Support, and Depression among African American Emerging Adults. Societies. 2015;5:151–70. doi: 10.3390/soc5010151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Assari S. Cross-country variation in additive effects of socio-economics, health behaviors, and comorbidities on subjective health of patients with diabetes. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2014;13:36. doi: 10.1186/2251-6581-13-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Assari S, Lankarani RM, Lankarani MM. Cross-country differences in the association between diabetes and disability. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2014;13:3. doi: 10.1186/2251-6581-13-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]