Abstract

Fatty liver can present as focal, diffuse, heterogeneous, and multinodular forms. Being familiar with various patterns of steatosis can enable correct diagnosis. In patients with equivocal findings on ultrasonography, magnetic resonance imaging can be used as a problem solving tool. New techniques are promising for diagnosis and follow-up. We review imaging patterns of steatosis and new quantitative methods such as proton density fat fraction and magnetic resonance elastography for diagnosis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in children.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is as widely encountered in children as in adults, with an estimated prevalence of 9.6% (1). It occurs due to accumulation of triglyceride in hepatocytes without alcohol ingestion. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) was first defined in children in 1983 (2). NAFLD includes a broad range of clinicopathologic features ranging from simple steatosis (fat with inflammation and/or fibrosis), steatohepatitis/NASH to cirrhosis. Some other diseases of liver can also cause hepatic steatosis including hepatitis B and C, Wilson’s disease, α-1-antitrypsin deficiency, autoimmune hepatitis, drug-induced liver injury (valproate, methotrexate, tetracycline, amiodarone, and prednisone), and total parenteral nutrition (3). Furthermore, fatty liver is a risk factor for cirrhosis, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.

In clinical practice, the diagnosis of NAFLD is made by increased serum ALT and/or presence of enlarged echogenic liver in ultrasonography. Being overweight or obese, and/or insulin resistance are highly indicative but not absolutely necessary for diagnosing NAFLD (4). The gold standard for diagnosis is liver biopsy, which additionally provides semi-quantitative analysis of NASH damage in children (5). It is an expensive, invasive procedure with a risk of morbidity (0.06%–0.35%) and mortality (0.01%–0.1%) (6).

The evaluation of liver fat in children via noninvasive imaging modalities is needed to avoid complications of biopsy and for follow-up. Main imaging modalities for the assessment of pediatric NAFLD are ultrasonography (US) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Computed tomography is the other imaging method for liver fat assessment, but ionizing radiation is a major drawback in children (7). Assessment of fat accumulation may cause diagnostic dilemmas and confusion due to manifestations with unusual structural patterns and imaging appearance of the liver. This article reviews the histopathology of pediatric NAFLD, radiologic evaluation and different structural patterns of childhood NAFLD/NASH on US and MRI. We also discuss diagnostic pitfalls and briefly review new imaging techniques.

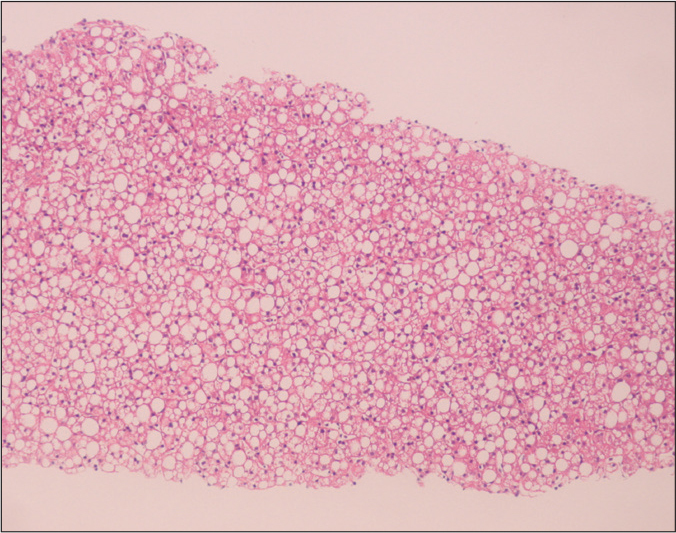

Histopathology of pediatric fatty liver

Pediatric studies of NAFLD/NASH have described significantly different histopathologic findings from the adult disease (8). The general findings in adulthood, which are designated in children as “type 1” includes macrovesicular steatosis, lobular inflammation, and ballooning degeneration, usually with poorly formed Mallory hyaline with or without perisinusoidal fibrosis with a zone 3 (perivenular) distribution. Pediatric “type 2” NASH is characterized by macrovesicular steatosis with portal inflammation and/or fibrosis. Perisinusoidal fibrosis or evidence of ballooning degeneration is not present (Fig. 1). Schwimmer et al. (5) characterized the liver biopsy results of pediatric patients with NAFLD and formed histologic definition of pediatric NASH. In contrast with adult patients, NASH in pediatric patients occurred with more portal inflammation (70%) and more portal fibrosis (60%) in biopsies. Type 2 NASH was detected in 51% and type 1 NASH in 17% of the study population. In type 2, children were younger, severity of obesity was greater, and advanced fibrosis was more common compared with type 1 NASH. Boys were significantly more likely to have type 2 NASH than girls.

Figure 1.

An 11-month-old girl liver biopsy shows type 2 nonalcoholic steatohepatitis with macrovesicular steatosis (hematoxylin-eosin staining, original magnification ×40).

Radiologic evaluation of pediatric fatty liver

Ultrasonography

US is the most preferred imaging technique for the assessment of hepatic steatosis due to low cost, easy accessibility, and outstanding safety. Normal liver echogenicity is similar to renal cortex or spleen echogenicity. Normal liver has intrahepatic vessels that are plainly demarcated and posterior parts are clearly illustrated. On the other hand, fat accumulation in the liver increases echogenicity and this can lead to indistinction of vessels and bile ducts and blurring of the diaphragm due to depth-dependent signal reduction (9). Despite mentioned advantages of US, operator and machine dependency, lack of objective quantification and significant decrease in sensitivity and specificity in morbid obesity are the major limitations for evaluation of hepatic steatosis (10). Furthermore, when biopsy-proven steatosis ratio is less than 30%, the sensitivity of US diminishes remarkably (7). Pathologic conditions such as fibrosis and inflammation may intensify liver echogenicity and can result in misinterpretations (11, 12). Given all these limitations, US evaluation of hepatic steatosis should be performed with attention and interpreted cautiously, and should not be recommended routinely as a sole diagnostic or monitoring tool for NAFLD in children.

Magnetic resonance imaging

Different methods are applied for the evaluation of liver fat by MRI, but the most widely preferred method is 2-point Dixon technique, also known as chemical shift imaging or dual-echo method (13, 14). In this technique, two sets of gradient-echo images of the liver are obtained and echo-time-dependent signal interference between fat and water is considered. On in-phase echo-time, water and fat signals add up and therefore, the total signal intensity is higher. On out-of-phase echo-time, water and fat signals cancel each other and consequently the total signal intensity diminishes. Healthy liver has no difference in signal intensities between the in-phase and out-of-phase images, however, in case of fat accumulation, the liver signal intensity decreases on the out-of-phase image. This imaging method is reliable in the absence of magnetic field inhomogeneity and iron deposition. The main drawback is that the quantity of water and fat affects the signals from fat and water; this can be managed by acquiring new images with variable T1-weighting by applying two flip angles (15). High-flip-angle imaging is desirable for uncovering small amounts of fat in tissues that include mainly water; low-flip-angle imaging should be applied for revealing small amounts of water in fat-rich tissues (14).

Magnetic resonance spectroscopy and proton density fat fraction

Magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) is established as the most reliable technique for the evaluation of hepatic steatosis, as it can detect the amount of water and fat in the liver. The prevailing frequency of hydrogen protons in water molecules in the MRI spectrum is at 4.7 ppm, while hydrogen protons in triglyceride molecules have lower values, 1.2 ppm. However, hydrogen protons in other triglyceride moieties have extra peaks at other frequencies (16). Accordingly, water has a single large peak in contrast to triglyceride, which has multiple frequency peaks. In normal cases, the dominant water peak is clear, and no triglyceride peaks are present. Existence of liver fat permits evaluation of a hepatic fat fraction via the area-under-water peak versus the area-under-fat peaks (17).

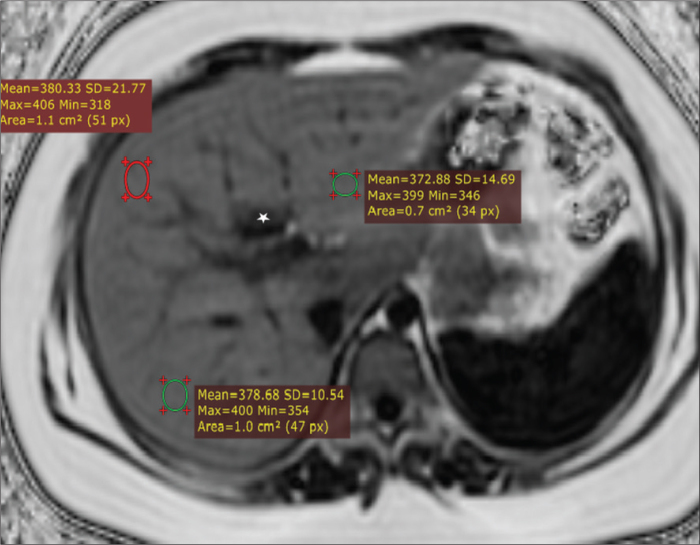

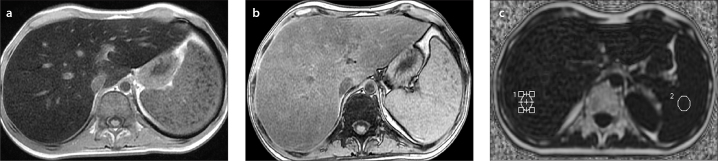

Proton density fat fraction (PDFF) measurement by MRI appears to be the most objective test for fat tissue quantification, as it removes T2* effect, T1 bias, spectral complexity of fat, eddy currents, noise bias, and magnetic inhomogeneity from the image and measures six peaks of fat. PDFF is the ratio of density of mobile fat protons (primarily triglycerides) and the total density of protons from mobile fat and mobile water. Moreover, it allows objective fat quantification and grading similar to MRS in a breath-hold time in patients with NAFLD (18). The practical strength of PDFF is recording of PDFF values from PDFF maps (Fig. 2). MRI-based PDFF maps or MRS-based PDFF values can be rapidly produced within seconds. Above all, it is very easy and practical for fat fraction measurement. In pediatric patients comparison of biopsy and PDFF showed promising results (19). PDFF is an unconfounded and fundamental property of tissue, and it is insensitive to changes in acquisition parameters which makes it a robust quantitative biomarker (20). PDFF is stable across scanner platform, scanner manufacturer, imaging center, and even field strength and can standardize MRI-based fat quantification (19). Moreover, simultaneous calculation of R2* and T2* maps from the same MRI sequence enables estimation of hepatic iron content, which can be important for diagnosis of coexisting fatty liver and hepatic iron overload (Fig. 3) (21, 22).

Figure 2.

A 13-year-old boy with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Axial proton density fat fraction (PDFF) map obtained by IDEAL-IQ sequence shows fat fraction of 38%. IDEAL-IQ is a three-dimensional volumetric imaging sequence used to create T2* and triglyceride fat fraction maps from a single breath-hold acquisition. The technique was used to estimate R2* (1/T2*) and PDFF (water-triglyceride fat separation) in the liver in a single simultaneous sequence. Note that fat fraction can be measured in any part of the liver (three different regions of interest with similar results). Fat spared area at the posterior aspect of segment 4 appears dark due to absence of fat (asterisk).

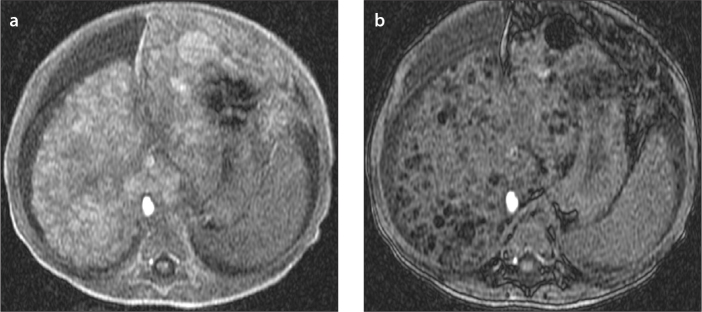

Figure 3.

a–c. A 17-year-old boy with non-Hodgkin lymphoma who presented with elevated liver enzymes and echogenic liver on US. In-phase (a) and out-of-phase (b) T1-weighted images show signal loss on in-phase images consistent with iron overload. Proton density fat fraction was calculated as 7% and T2* was 2 ms by IDEAL-IQ sequence (c), confirming coexisting mild steatosis and severe iron overload, which was not perceptible on in-phase and out-of-phase images.

Magnetic resonance elastography

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease has the potential to progress into hepatic fibrosis. Early diagnosis of fibrosis is important because, if treated, the degree of fibrosis can be minimized or reversed. Magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) is suggested to evaluate the stiffness of liver parenchyma. The technique depends on measuring propagation of shear waves through the hepatic parenchyma (23). It allows detection of fibrosis and differentiation of low-grade fibrosis from high-grade and also it may be feasible to distinguish steatosis from steatohepatitis (24, 25). The MRE pulse sequences developed for adults have been modified for pediatric patients. The absorption rate and field of view are adopted for pediatric age group; additionally, the power of driver is decreased by about 20% for patients between five and 18 years of age and by 40%–50% for patients younger than two years, compared with the settings used in adult patients (26). The reason to decrease power is to reduce the abdominal pain. Normal values of stiffness for pediatric age group have not been suggested for MRE, because liver stiffness was found to be not related with age by the ultrasound-based transient elastography. The success rate and accuracy of MRE is higher than ultrasound-based transient elastography (27). Furthermore, more of the liver can be evaluated with deep penetration, and ascites and obesity are not obstacles for examination with MRE. The drawbacks are higher cost and presence of iron load that makes detection of shear waves very difficult.

Patterns of fat deposition

Diffuse homogeneous and heterogeneous deposition

Diffuse fat deposition is the most frequently encountered pattern in the liver, and the distribution of fat is generally homogeneous (Fig. 4). Multifocal sparing can be seen in patients with diffuse steatosis (Fig. 5). Sometimes diffuse heterogeneous steatosis can be seen on US as scattered echogenic areas, which can be mild, moderate, or severe. MRI may be required to diagnose this condition (Figs. 6 and 7). Also areas of fat sparing in diffuse steatosis can mimic lesions, and MRI can allow diagnosis in patients with equivocal findings on US (Fig. 4b).

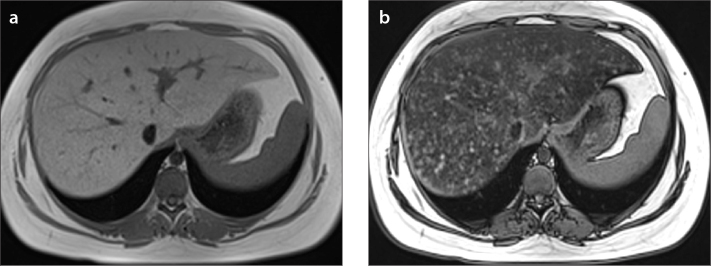

Figure 4.

a, b. An 11-year-old boy with diffuse liver steatosis. In-phase (a) and out-of-phase (b) images show diffuse heterogeneous signal drop is seen on out-of-phase image, consistent with steatosis. Note the focal sparing area in segments 2–3 within the diffuse steatosis (arrow in b), which is usually due to presence of aberrant left gastric vein.

Figure 5.

a, b. A 15-year-old girl with diffuse heterogeneous liver and subtle hypoechoic areas on US. In-phase (a) and out-of-phase (b) images show diffuse heterogeneous liver steatosis. Diffuse heterogeneous signal drop is seen on out-of-phase image consistent with steatosis. Note the submillimeter focal sparing areas within the heterogeneous steatosis consistent with multifocal fat sparing.

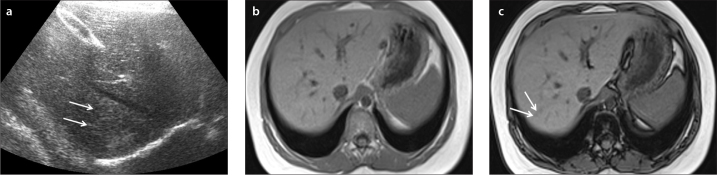

Figure 6.

a–c. US image (a) shows focal hyperechogenic areas in segments 7–8 of a 10-year-old boy (arrows). In-phase (b) and out-of-phase (c) images show mild heterogeneous liver steatosis. Out-of-phase image shows subtle signal drop compared with in-phase image confirming mild heterogeneous steatosis (arrows in c).

Figure 7.

a–c. US image (a) shows multiple hyperechoic lesions in the right liver lobe of a six-year-old boy. In-phase (b) and out-of-phase (c) images show severe heterogeneous liver steatosis. Out-of-phase image shows multiple lesions with signal drop compared with in-phase image consistent with severe heterogeneous steatosis (arrows in c).

Focal fat deposition

Focal fat deposition is the second most common involvement. Focal fat accumulation generally exists adjacent to the falciform ligament, in the porta hepatis, and in the gallbladder fossa. This distribution has been linked with variant venous circulation, such as anomalous gastric venous and pancreaticoduodenal venous drainage (28, 29). Focal fat depositions have been noticed emerging next to insulinoma metastases and they may cause diagnostic confusion by mimicking mass lesions. This appearance was hypothesized to be related to local insulin activity on hepatocyte triglyceride synthesis (30, 31). Specific location and chemical shift MRI are key findings for overcoming diagnostic dilemmas and hurdles.

Multifocal fat deposition

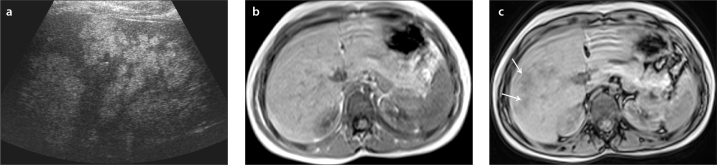

Multifocal fat deposition is an unusual distribution in childhood (Fig. 8). Multiple foci of fat accumulation are scattered in atypical locations all around the liver (32, 33). The fat centers mimic true nodules, which can be the source of diagnostic confusion especially in preexisting malignancy. Under such conditions, in-phase and out-of-phase MRI is superior to computed tomography and US. Absence of a mass effect, lack of hypointensity on in-phase image, absence of restriction on diffusion-weighted images and stability in size during follow-up are distinguishing features of multifocal fat areas.

Figure 8.

a–c. US image (a) shows multiple hyperechoic lesions in the liver of a nine-year-old boy. In-phase (b) and out-of-phase (c) images show multifocal liver steatosis. Out-of-phase image shows multiple lesions with signal drop compared with in-phase image consistent with multifocal steatosis.

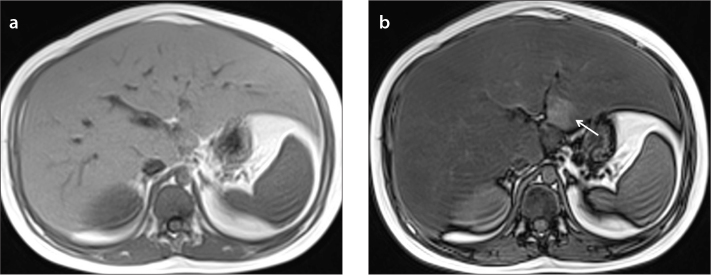

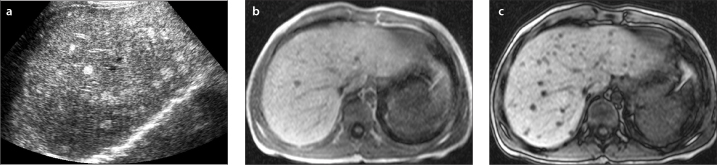

Pitfalls: fat-containing hepatic tumors

Hepatic adenomas, hepatocellular carcinomas, and regenerative nodules may have intracellular lipid (Fig. 9) (34, 35). However, postcontrast imaging features of these lesions allow differentiation from areas of focal steatosis.

Figure 9.

a, b. A one-year-old girl with tyrosinemia type 1. In-phase (a) and out-of-phase (b) images show multifocal fat containing lesions. Out-of-phase image shows multiple lesions with signal drop compared with in-phase image consistent with multifocal fat containing lesions diagnosed as multiple regenerative nodules, which were stable in size during the follow-up.

Conclusion

Fatty liver is a common clinical problem for children and adolescents. NAFLD constitutes a risk for diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cirrhosis, and end-stage liver disease. Currently, liver biopsy is the clinical standard for diagnosing and grading NAFLD. Noninvasive imaging modalities to assess liver fat in children have gained importance for avoiding invasive procedures and were proven to be reliable. The available evidence does not suggest the use of US as a sole method for the diagnosis or grading of fatty liver in children. Chemical shift GRE MRI is more trustworthy than US for evaluation and diagnosis of steatosis. The most common imaging pattern of steatosis is diffuse homogeneous fat deposition. Less common patterns include focal deposition, diffuse heterogeneous deposition, and multifocal deposition. These patterns may mimic neoplasms, leading to confusion and unnecessary diagnostic invasive procedures. Assessment of the fat content of the lesion, location, morphologic features, contrast enhancement, and mass effect usually permits a correct diagnosis.

Main points.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is a common clinical problem for children and adolescents.

The available evidence does not suggest the use of ultrasound as a sole method for the diagnosis or grading of fatty liver in children. Chemical shift GRE MRI is more trustworthy than US for evaluation and diagnosis of steatosis.

Most common imaging pattern of steatosis is diffuse homogeneous fat deposition. Less common patterns include focal deposition, diffuse heterogeneous deposition and multifocal deposition.

These patterns may mimic neoplasms, leading to confusion and unnecessary diagnostic invasive procedures.

Assessment of the fat content of the lesion, location, morphologic features, contrast enhancement, and mass effect usually permits a correct diagnosis.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest disclosure

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Schwimmer JB, Deutsch R, Kahen T, Lavine JE, Stanley C, Behling C. Prevalence of fatty liver in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2006;118:1388–1393. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1212. http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2006-1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moran JR, Ghishan FK, Halter SA, Greene HL. Steatohepatitis in obese children: a cause of chronic liver dysfunction. Am J Gastroenterol. 1983;78:374–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barshop NJ, Sırlin CB, Schwimmer JB, Lavine JE. Review article: epidemiology, pathogenesis and potential treatments of paediatric non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:13–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03703.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Widhalm K, Ghods E. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a challenge for pediatricians. Int J Obes. 2010;34:1451–1467. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.185. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2010.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwimmer HB, Behling C, Newbury R, et al. Histopathology of pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2005;42:641–649. doi: 10.1002/hep.20842. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/hep.20842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brunt EM. Pathology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;7:195–203. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2010.21. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrgastro.2010.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saadeh S, Younossi ZM, Remer EM, et al. The utility of radiological imaging in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:745–750. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.35354. http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/gast.2002.35354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwimmer JB, Deutsch R, Rauch JB, Behling C, Newbury R, Lavine JE. Obesity, insulin resistance, and other clinicopathological correlates of pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Pediatr. 2003;143:500–505. doi: 10.1067/S0022-3476(03)00325-1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1067/S0022-3476(03)00325-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quinn SF, Gosink BB. Characteristic sonographic signs of hepatic fatty infiltration. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1985;145:753–755. doi: 10.2214/ajr.145.4.753. http://dx.doi.org/10.2214/ajr.145.4.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ali R, Cusi K. New diagnostic and treatment approaches in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) Ann Med. 2009;41:265–278. doi: 10.1080/07853890802552437. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07853890802552437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mathiesen UL, Franzen LE, Aselius H, et al. Increased liver echogenicity at ultrasound examination reflects degree of steatosis but not of fibrosis in asymptomatic patients with mild/moderate abnormalities of liver transaminases. Dig Liver Dis. 2002;34:516–522. doi: 10.1016/s1590-8658(02)80111-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1590-8658(02)80111-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joseph AE, Saverymuttu SH, Al-Sam S, Cook MG, Maxwell JD. Comparison of liver histology with ultrasonography in assessing diffuse parenchymal liver disease. Clin Radiol. 1991;43:26–31. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(05)80350-2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0009-9260(05)80350-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Venkataraman S, Braga L, Semelka RC. Imaging the fatty liver. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2002;39:619–625. doi: 10.1016/s1064-9689(03)00051-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s1064-9689(03)00051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cassidy HF, Yokoo T, Aganovic L, et al. Fatty liver disease: MR imaging techniques for the detection and quantification of liver steatosis. Radiographics. 2009;29:231–260. doi: 10.1148/rg.291075123. http://dx.doi.org/10.1148/rg.291075123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bydder M, Yokoo T, Hamilton G, et al. Relaxation effects in the quantification of fat using gradient echo imaging. Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;26:347–359. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2007.08.012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.mri.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reeder SB, Cruite I, Hamilton G, Sirlin CB. Quantitative assessment of liver fat with magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2011;34:729–749. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22580. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jmri.22580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindback SM, Gabbert C, Johnson BL, et al. Pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a comprehensive review. Adv Pediatr. 2010;57:85–140. doi: 10.1016/j.yapd.2010.08.006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.yapd.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Idilman IS, Aniktar H, Idilman R, et al. Hepatic steatosis: quantification by proton density fat fraction with MR imaging versus liver biopsy. Radiology. 2013;267:767–775. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13121360. http://dx.doi.org/10.1148/radiol.13121360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tang A, Tan J, Sun M, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: MR imaging of liver proton density fat fraction to assess hepatic steatosis. Radiology. 2013;267:422–431. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12120896. http://dx.doi.org/10.1148/radiol.12120896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reeder SB, Hu HH, Sirlin CB. Proton density fat-fraction: a standardized MR-based biomarker of tissue fat concentration. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2012;36:1011–1014. doi: 10.1002/jmri.23741. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jmri.23741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vasanawala SS, Yu H, Shimakawa A, et al. Estimation of liver T2* in transfusion-related iron overload in patients with weighted least squares T2* IDEAL. Magn Reson Med. 2012;67:183–190. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22986. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/mrm.22986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hernando D, Levin YS, Sirlin CB, Reeder SB. Quantification of liver iron with MRI: State of the art and remaining challenges. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2014;40:1003–1021. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24584. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jmri.24584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Talwalkar JA, Yin M, Fidler JL, Sanderson SO, Kamath PS, Ehman RL. Magnetic resonance imaging of hepatic fibrosis: emerging clinical applications. Hepatology. 2008;47:332–342. doi: 10.1002/hep.21972. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/hep.21972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang Y, Ganger DR, Levitsky J, et al. Assessment of chronic hepatitis and fibrosis: comparison of MR elastography and diffusion-weighted imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196:553–651. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.4580. http://dx.doi.org/10.2214/AJR.10.4580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen J, Talwalkar JA, Yin M, et al. Early detection of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease by using MR elastography. Radiology. 2011;259:749–756. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11101942. http://dx.doi.org/10.1148/radiol.11101942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Serai SD, Towbin AJ, Podberesky DJ. Pediatric liver MR elastography. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:2713–2719. doi: 10.1007/s10620-012-2196-2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10620-012-2196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Towbin AJ, Serai SD, Podberesky DJ. Magnetic resonance imaging of the pediatric liver: Imaging of steatosis, iron deposition and fibrosis. Magn Reson Clin N Am. 2013;21:669–680. doi: 10.1016/j.mric.2013.05.001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.mric.2013.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsui O, Kadoya M, Takahashi S, et al. Focal sparing of segment IV in fatty livers shown by sonography and CT: correlation with aberrant gastric venous drainage. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;164:1137–1140. doi: 10.2214/ajr.164.5.7717220. http://dx.doi.org/10.2214/ajr.164.5.7717220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gabata T, Matsui O, Kadoya M, et al. Aberrant gastric venous drainage in a focal spared area of segment IV in fatty liver: demonstration with color Doppler sonography. Radiology. 1997;203:461–463. doi: 10.1148/radiology.203.2.9114105. http://dx.doi.org/10.1148/radiology.203.2.9114105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fregeville A, Couvelard A, Paradis V, Vilgrain V, Warshauer DM. Metastatic insulinoma and glucagonoma from the pancreas responsible for specific peritumoral patterns of hepatic steatosis secondary to local effects of insulin and glucagon on hepatocytes. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1150–1365. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.08.033. http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2005.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sohn J, Siegelman E, Osiason A. Unusual patterns of hepatic steatosis caused by the local effect of insulin revealed on chemical shift MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176:471–474. doi: 10.2214/ajr.176.2.1760471. http://dx.doi.org/10.2214/ajr.176.2.1760471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kroncke TJ, Taupitz M, Kivelitz D, et al. Multifocal nodular fatty infiltration of the liver mimicking metastatic disease on CT: imaging findings and diagnosis using MR imaging. Eur Radiol. 2000;10:1095–1100. doi: 10.1007/s003300000360. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s003300000360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kemper J, Jung G, Poll LW, Jonkmanns C, Luthen R, Moedder U. CT and MRI findings of multifocal hepatic steatosis mimicking malignancy. Abdom Imaging. 2002;27:708–710. doi: 10.1007/s00261-002-0019-1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00261-002-0019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Basaran C, Karcaaltincaba M, Akata D, et al. Fat-containing lesions of the liver: cross-sectional imaging findings with emphasis on MRI. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184:1103–10. doi: 10.2214/ajr.184.4.01841103. http://dx.doi.org/10.2214/ajr.184.4.01841103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karcaaltincaba M, Akhan O. Imaging of hepatic steatosis and fatty sparing. Eur J Radiol. 2007;61:33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2006.11.005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrad.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]