Abstract

Synthetic ways towards uridine 5′-diphosphate (UDP)-xylose are scarce and not well established, although this compound plays an important role in the glycobiology of various organisms and cell types. We show here how UDP-glucose 6-dehydrogenase (hUGDH) and UDP-xylose synthase 1 (hUXS) from Homo sapiens can be used for the efficient production of pure UDP-α-xylose from UDP-glucose. In a mimic of the natural biosynthetic route, UDP-glucose is converted to UDP-glucuronic acid by hUGDH, followed by subsequent formation of UDP-xylose by hUXS. The nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) required in the hUGDH reaction is continuously regenerated in a three-step chemo-enzymatic cascade. In the first step, reduced NAD+ (NADH) is recycled by xylose reductase from Candida tenuis via reduction of 9,10-phenanthrenequinone (PQ). Radical chemical re-oxidation of this mediator in the second step reduces molecular oxygen to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) that is cleaved by bovine liver catalase in the last step. A comprehensive analysis of the coupled chemo-enzymatic reactions revealed pronounced inhibition of hUGDH by NADH and UDP-xylose as well as an adequate oxygen supply for PQ re-oxidation as major bottlenecks of effective performance of the overall multi-step reaction system. Net oxidation of UDP-glucose to UDP-xylose by hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) could thus be achieved when using an in situ oxygen supply through periodic external feed of H2O2 during the reaction. Engineering of the interrelated reaction parameters finally enabled production of 19.5 mM (10.5 g l−1) UDP-α-xylose. After two-step chromatographic purification the compound was obtained in high purity (>98%) and good overall yield (46%). The results provide a strong case for application of multi-step redox cascades in the synthesis of nucleotide sugar products.

Keywords: biosynthetic cascade, carbohydrates, multi-enzyme catalysis, nucleotide sugars, UDP-glucose dehydrogenase, UDP-xylose synthase, uridine 5′-diphosphate (UDP)

Introduction

Uridine 5′-diphosphate d-xylose (UDP-xylose; UDP-Xyl) is the donor substrate of xylosyltransferases (XylT) that transfer a xylosyl moiety to different acceptor molecules in the biosynthesis of glycoconjugates. Proteoglycan biosynthesis, for example, is initiated through transfer of a xylosyl residue to the protein acceptor. Xylosyl-containing glycoconjugates play central roles in different cellular processes including signalling, virulence or build-up of the cell wall and the extracellular matrix.[1] In nature, UDP-Xyl is produced by UDP-xylose synthase (UXS; EC 4.1.1.35) via oxidative decarboxylation of UDP-glucuronic acid (UDP-GlcUA).[2] UDP-glucose dehydrogenase (UGDH; EC 1.1.1.22) synthesizes UDP-GlcUA in a NAD+-dependent two-step oxidation of UDP-glucose (UDP-Glc).[3] UDP-Glc is ultimately derived from glucose via the glycolytic intermediate glucose 6-phosphate and glucose 1-phosphate.[4]

Besides its important biological function, UDP-Xyl is a valuable chemical that finds use as substrate for XylT in different research applications. UDP-Xyl is needed for enzyme activity profiling and in vitro enzyme characterization. It is also used for in vivo studies of XylT function in cell biology and tissue development. UDP-Xyl is an important ligand and inhibitor of enzymes other than XylT, UGDH, for example.[5] To support the different fields in glycobiology research with UDP-Xyl, therefore, an efficient supply of anomerically pure compound would be desirable.[6] However, while synthesis methods for some nucleotide sugars (e.g., UDP-Glc) are well established, synthetic routes or pathways to UDP-Xyl are rare.[4c,7] Although several research groups have enzymatically prepared UDP-Xyl in vitro, the resulting product was rarely purified and/or isolated.[7,8]

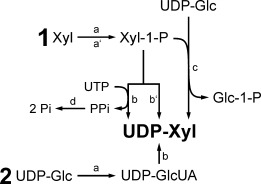

Generic ways of nucleotide sugar synthesis are shown in Scheme 1.[7] Starting from a monosaccharide as in route (1), the product is synthesized enzymatically in two steps, where in the first step (a) a diastereoselective kinase forms an α-configured sugar 1-phosphate using a nucleoside triphosphate donor. The sugar 1-phosphate is then converted into the desired nucleotide sugar via step (b) or (c). Catalytic reaction (b) involves a nucleotidyltransferase where nucleoside triphosphate (here: UTP) is the second substrate. However, use of the nucleotidyltransferase reaction constitutes a potentially critical issue in the overall synthetic route, because transformations are often characterized by a highly unfavorable reaction equilibrium, as well as inhibition by pyrophosphate released from nucleoside triphosphate.[9] Provision of thermodynamic “pull” from a coupled reaction where pyrophosphatase (d) is used to catalyze hydrolysis of the pyrophosphate presents a possible solution, but further enhances complexity of the reaction system. Glycosyl exchange with a nucleotide sugar (c) is another approach, but also depends on a nucleotidyltransferase exhibiting a back reaction.

Scheme 1.

Generic methods of nucleotide sugar synthesis, exemplified for UDP-Xyl preparation (Xyl-1-P: α-d-xylose 1-phosphate, Glc-1-P: α-d-glucose 1-phosphate).

The same synthetic route (1) is also pursued with purely chemical methods (a′–b′)[10] or chemo-enzymatically (e.g., a′–c). A recent example for chemical UDP-Xyl synthesis following route (b) is the strategy by Ishimizu et al.[6] where pure UDP-α-Xyl was prepared from activated UMP and xylose 1-phosphate. A yield of 35% after a relatively long reaction time of five days was reported. Errey et al. showed a chemo-enzymatic method for production of UDP-Xyl and also of other UDP sugars according to route (a′–c).[8h] UDP-Xyl was enzymatically prepared from chemically synthesized xylose 1-phosphate on a small 500 μL scale (37.5 g l−1). Chemical methods for UDP-Xyl synthesis starting from d-xylose have also been established, but they often lead to anomeric mixtures of the product.[11] Additionally, in vivo enzymatic approaches starting from d-glucose have been reported. For example, Yang et al. used engineered Escherichia coli cells for production of various NDP sugars, including UDP-Xyl.[8g]

When an already available nucleotide sugar is used as substrate for UDP-Xyl synthesis, the target molecule is formed either by direct conversion (e.g., sugar oxidation) or in several steps, as shown in route (2).[7] Oka et al. established route (2) in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae where engineered cells synthesized UDP-Xyl from the naturally present UDP-Glc.[8i] From the very limited number of reports about pure UDP-Xyl preparation, the need for an efficient and convenient synthesis is evident. In particular, the preparation of anomerically pure UDP-Xyl is a problem requiring special attention. We present herein a new enzymatic in vitro approach according to route (2) in Scheme 1. In analogy to the natural biosynthetic pathway, UDP-Glc is converted to UDP-Xyl by UGDH and UXS. Both enzymes exhibit no observable back reaction, which presents a clear advantage in having eliminated thermodynamic restrictions of the nucleotidyltransferase-catalyzed conversion. Comprehensive step-by-step reaction analysis and optimization enabled us to set up an effective biocatalytic system for the production of pure UDP-α-Xyl. The results provide a strong case for synthetic use of multi-step redox cascades in the preparation of nucleotide sugar products.

Results and Discussion

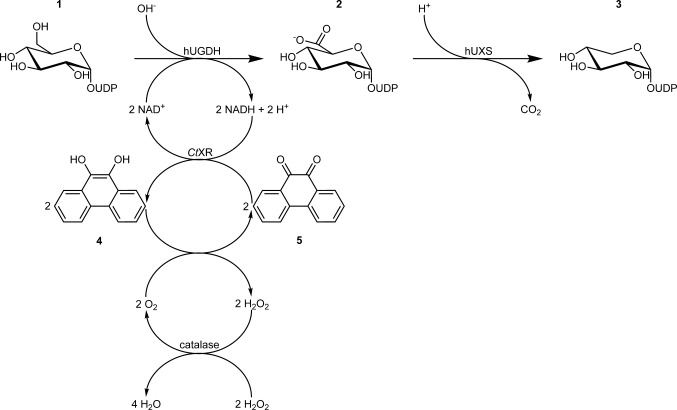

The herein presented system consists of a two-step conversion of UDP-Glc to UDP-Xyl via UDP-GlcUA catalyzed by UGDH and UXS, as shown in Scheme 2. Human enzymes (hUGDH and hUXS) were used to accomplish this task. We coupled the hUGDH reaction to a coenzyme regeneration cascade making use of Candida tenuis xylose reductase (CtXR) and bovine liver catalase.[12] Thermodynamic and kinetic requirements as well as cost considerations had to be taken into account, as regeneration of NAD+ is not well established, compared to NADH.[13] We applied a system originally described by Pival et al., in which CtXR reduces 9,10-phenanthrenequinone (PQ) to 9,10-phenanthrene hydroquinone (PQH2).[12] The NADH produced in UDP-Glc oxidation is recycled to NAD+ during PQ reduction. PQH2 is spontaneously re-oxidized by molecular oxygen in a fast radical chain reaction. Finally, catalase cleaves the thus produced hydrogen peroxide. The thermodynamically highly favorable reduction of oxygen provides a strong driving force that keeps the cycle running.[12] For that purpose, the development of an effective oxygen supply method was crucial.

Scheme 2.

Chemo-enzymatic cascade transformation employed for synthesis of UDP-Xyl (3) from UDP-Glc (1) via UDP-GlcUA (2) through the combined action of hUGDH, hUXS, CtXR and bovine catalase. The coupling of the hUGDH reaction to CtXR-based NAD+ regeneration strongly improves efficiency of the system. Oxidation of PQH2 (4) to PQ (5) is coupled to H2O2 decomposition for in situ O2 supply, leading formally to oxidative decarboxylation of UDP-Glc to UDP-Xyl by H2O2.

The second main task in developing this multi-enzyme multi-reaction system of UDP-Xyl synthesis in one pot was the optimization of various interrelated reaction parameters. Comprehensive analysis of thermodynamic, kinetic and stability effects on each reaction of the overall system was necessary, and it turned out that overcoming inhibition effects was especially important. UXS is inhibited by UDP-Xyl, UGDH is inhibited by UDP-Xyl and also by NADH.[7,14] Till now, these inhibitions constituted a major restriction in enzymatic in vitro synthesis of not only UDP-Xyl, but also UDP-GlcUA.[7]

Engineering of Reaction Parameters

The initial idea was to perform the synthesis as a “one-pot one-step” conversion, where all enzymes are present right from the beginning. However, conversion of 20 mM UDP-Glc stopped after production of only 2 mM UDP-Xyl (data not shown). The most likely cause for the low yield was inhibition of hUGDH, as it has been reported that full inhibition of UGDH can be accomplished by only 50 μM UDP-Xyl.[5] Therefore, we switched to a “one-pot two-step” reaction and separated UDP-GlcUA and UDP-Xyl production by adding hUXS only after UDP-Glc was fully consumed.

The first step (UDP-Glc→UDP-GlcUA) depends on the combined action of hUGDH, CtXR and bovine catalase. It was therefore crucial to find conditions suited for all three enzymes in order to establish an efficient synthetic system. As catalase activity is invariant over a large pH range (4.0–8.5) and the enzyme was employed in large excess, it was readily used in the synthesis without further testing or optimization.[15] Therefore, it was primarily necessary to match hUGDH and CtXR reactions, which was done by adaption of buffer, temperature and pH conditions.

Because potassium phosphate buffer was known to be compatible with both hUGDH and CtXR,[3,12] it was used in the synthesis experiments. Next, we determined the influence of different temperatures on UDP-Glc conversion. The CtXR-based coenzyme recycling system had previously been developed at 25 °C, and stability of the reductase enzyme decreases above 30–35 °C.[11,16] However, an increase in reaction temperature from 25 °C to 37 °C during multi-enzymatic UDP-Glc conversion improved both reaction time and yield (data not shown). Based on these results, 37 °C was used in the UDP-Glc→UDP-GlcUA step.

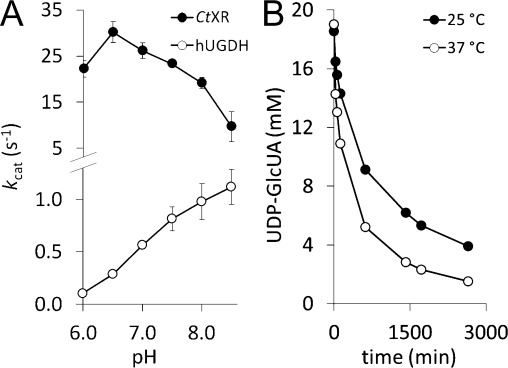

Last, pH-activity dependencies of hUGDH and CtXR at synthesis temperature were examined. We tested activities of both enzymes in the pH range 6.0 to 8.5 at 37 °C (Figure 1A). Although the pH optimum of hUGDH was distinctly higher than that of CtXR, at pH 7.5 both enzymes exhibited sufficiently high activity for the coupled enzymatic conversion.

Figure 1.

A) pH-activity dependencies of CtXR and hUGDH. At pH 7.5 both enzymes show satisfactory activity. B) Comparison of UDP-GlcUA conversion by hUXS (30 μM) at 25 °C and 37 °C, showing the beneficial effect of the higher reaction temperature.

Investigation of hUXS, the only enzyme involved in the second step (UDP-GlcUA→UDP-Xyl), revealed that the enzyme also showed faster conversion and higher yield at 37 °C than at 25 °C using potassium phosphate buffer (Figure 1B). We thus chose to not change the reaction conditions prior to hUXS addition in the complete reaction system.

Engineering of UDP-Glc Conversion

Without efficient regeneration of the coenzyme, the conversion of UDP-Glc to UDP-GlcUA would be unfavorable for synthetic purposes (see Scheme 2). One commonly chosen group of enzymes to accomplish this task are water-forming NADH oxidases that use molecular oxygen to convert NADH to NAD+.[17] However, their operational stability can be an issue under conditions of coenzyme recycling, for example, they are prone to inactivation by oxidizing agents.[12,18] We therefore used a modification of the method described by Pival et al. (Scheme 2), who used an enzymatic cascade to mimic the NADH oxidase reaction, and thus circumvented the known stability problems.[12] In this cascade reaction, the most critical point is an adequate oxygen supply for radical oxidation of PQH2 to PQ (see Scheme 2) that was previously achieved by membrane gassing.[12] We investigated a new approach of oxygenation that is based on the “chemical oxygen source” H2O2. Underlying rationale was to achieve higher efficiency and easier parallelization and handling of the system. High catalase activity (100 U/mL) in combination with periodic feeding of H2O2 was used to realize fast in situ oxygen production (Scheme 2). Fast turnover of H2O2 was also necessary to prevent instability of hUGDH. 20 mM H2O2 led to a 50% reduction in initial activity and inactivation of the enzyme after only 1 min. In contrast, CtXR was not affected by the oxidant, as already described previously.[12]

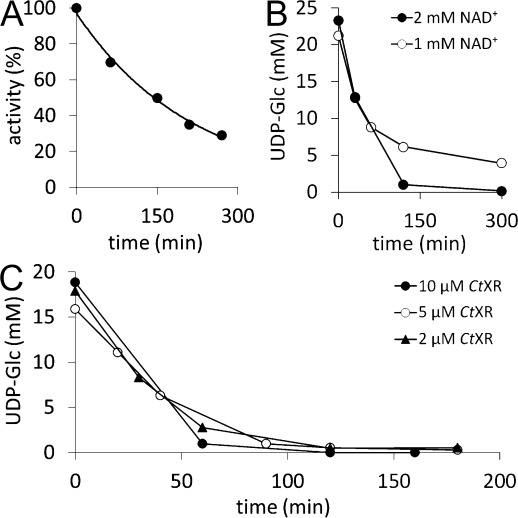

Initially, we investigated the use of 250 μM NAD+ for conversion of 20 mM UDP-Glc. However, with these parameters substrate conversion was below 50%. As the UGDH reaction is considered irreversible in the UDP-GlcUA direction,[7] this effect was not due to equilibrium, but rather due to the Ki of 27 μM for NADH.[14] The low conversion was therefore ascribed tentatively to accumulation of NADH. Inactivation of CtXR during the synthetic reaction (Figure 2A) was a plausible reason for the gradual increase in NADH during the reaction. In combination with the low initial NAD+ concentration, the reaction would quickly come to a halt. However, CtXR was already employed in high excess over hUGDH (12 U/mL vs. 0.9 U/mL initial activity). Therefore, a further increase in CtXR concentration did not seem meaningful and we rather evaluated the influence of higher NAD+ concentrations on overall UDP-Glc conversion to overcome the problem of enzyme inhibition. The use of 1 mM NAD+ still resulted in progressive slowdown of the reaction and incomplete conversion even after 5 h. At 2 mM NAD+, by contrast, UDP-Glc was fully converted after only 3 h (Figure 2B). Therefore, the latter concentration of was used in subsequent syntheses.

Figure 2.

A) CtXR inactivation during biocatalytic synthesis of UDP-GlcUA (t1/2=150 min). B) Effect of NAD+ concentration on conversion of UDP-Glc when 10 μM hUGDH were used. Full conversion was only achieved with 2 mM NAD+, not with 1 mM. C) Effect of CtXR concentration on conversion. No change in UDP-Glc conversion (10 μM hUGDH) was observed regardless of whether 10 μM, 5 μM or 2 μM CtXR were used. The NAD+ concentration was 2 mM.

However, the high excess of CtXR was considered economically unfavorable, and, as shown above, the use of a higher NAD+ concentration seemed more likely to be beneficial for UDP-GlcUA yield. We thus investigated the effect of lowering CtXR concentration with regard to reaction time and completeness of conversion. No significant change in UDP-Glc conversion was noticed upon decreasing the CtXR concentration from 10 μM to 2 μM (Figure 2C). In contrast, lowering the hUGDH concentration by 50% led to incomplete conversion of UDP-Glc (60%) and was not considered in further experiments (Supporting Information, Figure S1).

In all experiments, a UDP-Glc concentration of 20 mM was used. Attempts to use a higher concentration (e.g., 40 mM) failed and only about 50% conversion were reached (Supporting Information, Figure S2). This effect occurred most probably due to a large pH drop during UDP-GlcUA production (about one pH unit per 20 mM UDP-Glc converted), strongly decreasing hUGDH activity (see Figure 1A). Using a higher buffer concentration to maintain a stable pH interfered with activities of both hUGDH and CtXR and was not further pursued (Supporting Information, Figure S3). Automated pH control would constitute a solution when working with larger reaction volumes; however, in the low volume of 1 mL used herein, the approach was not considered to be practical.

Engineering of UDP-GlcUA Conversion

The second part of the biosynthetic reaction consisted of direct conversion of UDP-GlcUA to UDP-Xyl, with the only by-product being CO2 (Scheme 2). The hUXS reaction was not affected by the pH drop from 7.5 to about 6.5–6.7 during UDP-GlcUA synthesis. Even without adjusting the pH prior to addition of the enzyme, UDP-Xyl yield was approximately 90% at the end of the reaction (data not shown). The incomplete UDP-GlcUA conversion was most probably caused by a combination of hUXS inhibition by UDP-Xyl, as already reported for UXS,[7] and enzyme inactivation. We therefore doubled hUXS concentration to 30 μM, which indeed led to full conversion of UDP-GlcUA to UDP-Xyl within 24 h (see the next section).

Preparative UDP-Xyl Synthesis

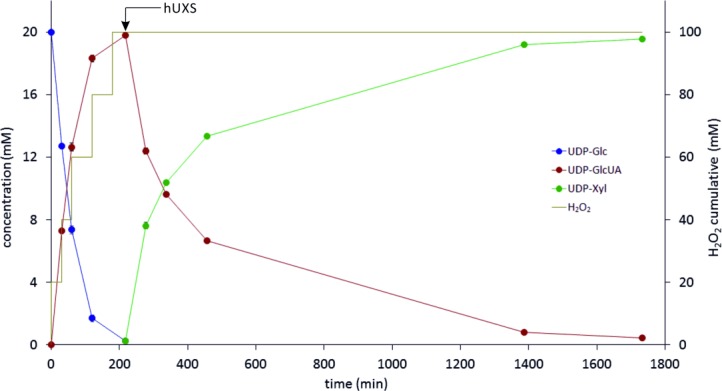

Using the previously optimized parameters and conditions, a highly efficient biocatalytic reaction system for UDP-Xyl production could be set up. The time course of the reaction is depicted in Figure 3, reaction conditions are summarized in Table 1. Twenty millimoles of UDP-Glc/L were nearly fully (> 97.5%) and highly reproducibly (standard deviation in triplicate experiment <3%) converted to UDP-Xyl within 29 h. Already after 3.5 h, residual UDP-Glc concentration was <1% (0.23±0.04 mM), and the UDP-GlcUA produced was readily transformed to UDP-Xyl after addition of hUXS.

Figure 3.

Time course of biocatalytic UDP-Xyl production (data from triplicate experiments). Concentrations of UDP-Glc, UDP-GlcUA and UDP-Xyl are shown (left ordinate). The yellow line depicts the total amount of H2O2 added to the reaction mixture. hUXS was added at the time indicated, after UDP-Glc was consumed.

Table 1.

Reaction conditions of UDP-Xyl production

| UDP-Glc | NAD+ | PQ | H2O2[a] | BSA | hUGDH | hUXS | CtXR | Catalase | V | T | pH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [mM] | [mM] | [μM] | [mM] | [g L−1] | [μM] | [μM] | [μM] | [U] | [mL] | [°C] | |

| 20 | 2 | 25 | 20 | 1 | 10 | 30 | 2 | 100 | 1 | 37 | 7.5 |

[a] Concentration in reaction tube after feeding H2O2 (see text).

H2O2 was added batch-wise, as shown in Figure 3. A total amount corresponding to 100 mM H2O2 was added for full conversion of 20 mM substrate, indicating that 40% of the generated oxygen were consumed in the reaction. Most likely gaseous oxygen was lost through the polypropylene (PP) reaction tube, as PP is highly oxygen permeable.[19] Usage of a tightly sealed, less oxygen permeable reaction vessel (e.g., PVC, PET) could be used to improve efficiency.[19] However, H2O2 does not contribute significantly to UDP-Xyl production costs due to its low price compared to the product (>45 US $/mg).[20] In Figure 3 it is also visible that the hUXS reaction slowed down considerably after reaching about 50% conversion (see before), but still gained 98% conversion within a reasonable time. With this system, a total amount of 10.5 mg UDP-Xyl could be produced in one reaction batch and, due to the simple process set up, numbering up would easily be accomplishable.

We also determined total turnover numbers (TTN) of different compounds in the reaction to facilitate evaluation of the system (Table 2). Pival et al. reached a TTNPQ of 1000 in conversion of 25 mM substrate, which fits well to the value obtained here (TTNPQ=780, csubstrate=20 mM).[12] Therefore, this indicates that the approach of feeding H2O2 is at least equally effective as membrane gassing. TTN values for NAD+ and CtXR are lower than those reported by Pival et al. due to the aforementioned inhibitory effects that occur during reaction. Nevertheless, the system provides a significant improvement over the use of stoichiometric amounts of the coenzyme.

Table 2.

Characteristics of UDP-Xyl production

| hUGDH | hUXS | CtXR | NAD+ | PQ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TTN[a] | TTN | TTN | TTN | Re[b] | TTN | Re |

| 1950 | 650 | 9750 | 10 | 40 | 780 | 40 |

[a] Total turnover number (mM UDP-Xyl produced per mM of compound consumed).

[b] Number of regeneration cycles

Purification and Isolation of UDP-Xyl

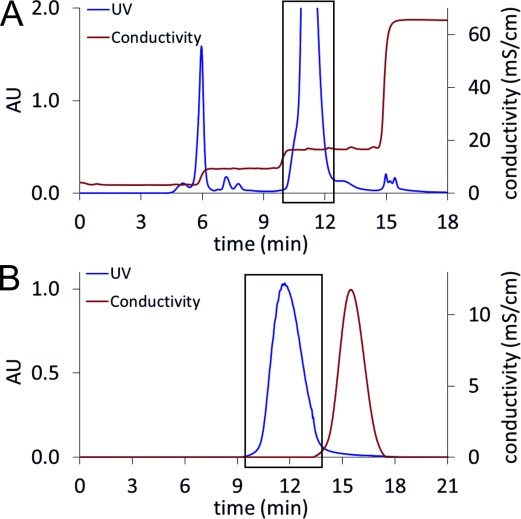

After biocatalytic synthesis, a two-step chromatographic protocol was used to purify UDP-Xyl. In the first step, anion exchange chromatography (AEX) was employed to separate UDP-Xyl from other compounds of the reaction mixture. Subsequently, the salt used for elution was removed by size exclusion chromatography (SEC). To minimize total loading on the column and thereby improve separation and sugar binding capacity, proteins (hUGDH, hUXS, CtXR, BSA and catalase) were removed by membrane filtration prior to AEX, as described in the Experimental Section.

In AEX an ammonium formate (NH4HCO2) buffer (pH 4.2) was used as mobile phase. By applying a step-wise gradient between 20 mM and 500 mM NH4HCO2, resolution of the reaction mixture was possible within 18 min (Figure 4A). UDP-Xyl eluted separately from other compounds at 105 mM NH4HCO2 (σ=17 mS⋅cm−1).

Figure 4.

A) Anion exchange chromatography. The reaction mixture was loaded on a Resource Q column and eluted using a NH4HCO2 gradient. The peak inside the black box is UDP-Xyl. B) Size exclusion chromatography: UDP-Xyl-containing fractions from AEX were concentrated and applied to a Sephadex G-10 column. Elution with deionized water led to pure UDP-Xyl (black box).

For removal of NH4HCO2 and water in one step, lyophilization can be used. However, it is reported that nucleotide sugars are prone to decomposition under such conditions.[21] Therefore, we used SEC to separate NH4HCO2 from UDP-Xyl and evaluated different SEC stationary phases (Bio-Gel P-2 from Bio-Rad; Sephadex G-25 and Sephadex G-10 from GE Healthcare) in combination with elution by deionized water. As UDP-Xyl seemed to adsorb to Bio-Gel P-2 (polyacrylamide), this resin was unsuitable. Sephadex G-25 (dextran) led to good separation, however with some overlap between UDP-Xyl and NH4HCO2 (Supporting Information, Figure S4). In order to improve product recovery, the finer Sephadex G-10 material (exclusion limit=700 Da vs. 1000 Da for G-25) was chosen. With this method, nearly full separation of UDP-Xyl and NH4HCO2 could be achieved (Figure 4B).

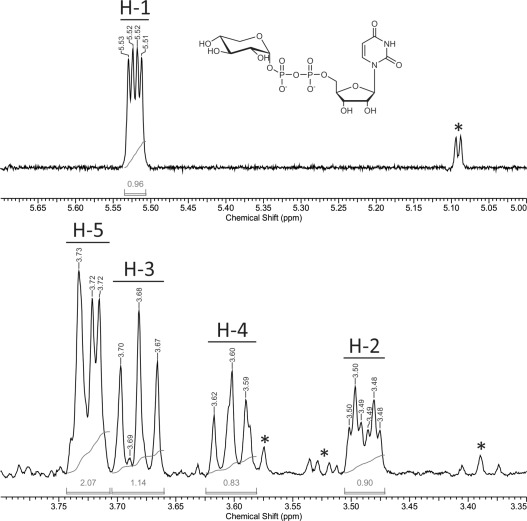

UDP-Xyl was finally isolated from the aqueous solution by removal of water under reduced pressure. It was previously confirmed that the chosen conditions do not lead to decomposition of the product. Within some hours, UDP-α-Xyl was obtained as its ammonium salt (white to yellow powder, see Supporting Information, Figure S5). Identity of the product was confirmed by 1H NMR (Figure 5), and capillary zone electrophoresis (Supporting Information, Figure S6) showed a purity of 98%. The total amount obtained from one reaction batch was 5.3 mg, corresponding to an isolated yield of 46% (compared to the end of biocatalytic synthesis).

Figure 5.

1H NMR spectrum of purified UDP-Xyl. Signals of sugar protons H-1 to H-5 were assigned according to the literature, impurities are indicated by an asterisk.[8a] Only a small formate signal is visible at 8.43 ppm,[22] indicating nearly complete removal of NH4HCO2 during purification (Supporting Information, Figure S7).

Conclusions

We have established a highly efficient multi-enzyme multi-step transformation for the synthesis of the rare and also expensive UDP-Xyl from the well available and comparably expedient substrate UDP-Glc. Conversion of UDP-Glc was achieved by coupling a two-step synthetic reaction cascade to a chemo-enzymatic coenzyme regeneration cascade, as shown in Scheme 2. We show that in-depth analysis of each individual reaction in combination with careful optimization work was important to bring the complex multi-component system to the point of truly effective performance. One key feature of conversion efficiency was in situ O2 production from H2O2 as the actual chemical oxidant supplied to the overall reaction. Separation in time of the catalytic action of hUXS from that of hUGDH was also critical for high synthesis rates and complete conversion. Fast chromatographic work-up of the reaction mixture lead to highly pure UDP-Xyl in good yield.

As there exist several well established systems for UDP-Glc synthesis based on assembly of UDP-Glc from glucose and UTP,[23] our system could be expanded by coupling one of these methods to the herein described UDP-Xyl synthesis. This would reduce the costs of UDP-Xyl synthesis even further. Additionally, our system also offers an efficient way to UDP-GlcUA, a compound whose synthesis was equally difficult to achieve till now.[7] We also believe that synthesis of UDP-Xyl provides a strong case supporting the use of multi-step enzymatic cascades in the preparation of high-value products such as nucleotide sugars.

Experimental Section

Chemicals and Strains

UDP-glucose (>90% purity) was purchased from Carbosynth (Compton, UK), UDP-glucuronic acid (>98% purity), 9,10-phenanthrenequinone (>99% purity), bovine serum album (BSA; >98% purity) and bovine catalase (3809 U/mg) from Sigma–Aldrich (Vienna, Austria). NAD+ (>98% purity) was obtained from Roth (Karlsruhe, Germany). Aspergillus niger glucose oxidase type VII-S (GOD; 246 U/mg) and horseradish peroxidase type II (POD; 181 U/mg) were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich. All other chemicals were purchased either from Sigma–Aldrich or Roth and were of the highest purity available.

Design and assembly of the recombinant Escherichia coli strains for hUGDH, hUXS and CtXR expression are described elsewhere.[2,3,12]

Enzyme Expression and Purification

Expression and purification of the recombinant hUGDH, hUXS and CtXR are described in full detail elsewhere.[2,3,12] Briefly, the enzymes were overexpressed in E. coli Rosetta 2(DE3) using a pBEN- (hUGDH), p11- (hUXS) or pQE-30- (CtXR) derived expression vector. After high-pressure cell disruption, His-tagged hUXS and CtXR were isolated from the crude extract using a Cu2+-loaded IMAC sepharose column (GE Healthcare, Vienna, Austria), while a Strep-Tactin sepharose column (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) was used for Strep-tagged hUGDH. Elution with imidazole (His-tag) or desthiobiotin (Strep-tag) yielded highly pure enzymes (checked by SDS-PAGE). Buffer exchange to remove imidazole or desthiobiotin was done using Vivaspin centrifugal concentrators (Sartorius Stedim, Göttingen, Germany). Enzyme preparations were stored at −70 °C.

Enzymatic Assays

Activities of hUGDH and CtXR were determined by monitoring NADH formation (hUGDH) or consumption (CtXR) on a Beckman-Coulter DU800 spectrophotometer (λ=340 nm) with temperature-controlled sample holder (37 °C). Assays for hUGDH contained 0.1 μM enzyme, 0.5 or 1 mM UDP-Glc and 5 or 10 mM NAD+ in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (PPB) (pH 7.5), for CtXR 0.05 μM enzyme, 50 μM PQ and 250 μM NADH in the same buffer were used. hUXS was assayed using 5 μM enzyme, 5 mM UDP-GlcUA and 0.5 mM NAD+ in 50 mM PPB (pH 7.5). In this case, results were obtained by measuring UDP-GlcUA consumption on HPLC or CE.

Enzyme activities during biocatalytic synthesis were measured by diluting a sample 1:100 (hUGDH) or 1:200 (CtXR) in 50 mM PPB (pH 7.5) containing 5 mM NAD+ (hUGDH) or 50 μM PQ (CtXR). Reactions were started by addition of 1 mM UDP-Glc (hUGDH) or 250 μM NADH (CtXR) and followed by monitoring the change in NADH concentration as described above.

The pH-activity dependencies of hUGDH and CtXR were determined by measuring activity as described above using 50 mM PPB in the pH range 6.0–8.5.

Biocatalytic Synthesis

Unless otherwise stated, reaction mixtures for UDP-Xyl biosynthesis contained 20 mM UDP-Glc, 2 mM NAD+, 25 μM PQ, and 0.1% (w/v) BSA in 50 mM PPB (pH 7.5). Enzymes were added in the following order: 100 U/mL bovine liver catalase, 2 μM CtXR. All experiments were done on a Thermomixer Comfort (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) at 37 °C without agitation. The reaction mixture was incubated for several minutes before reaction was started by addition of 10 μM hUGDH followed by immediate addition of 20 mM H2O2, mixing, and closing of the 1.5-mL Eppendorf reaction tube cap. Total reaction volume was 1 mL.

20 μL samples were taken at the beginning and the indicated time points. After each sample, H2O2 was added to a concentration of 20 mM, until UDP-Glc was fully consumed. 30 μM hUXS were added to the mixture afterwards and the reaction was allowed to proceed to completeness.

High Performance Liquid Chromatography

Samples were analyzed on an Agilent 1200 HPLC system equipped with a 5 μm Zorbax SAX analytical HPLC column (4.6×250 mm; Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and a UV detector (λ=262 nm). Reactions were stopped by heating the samples to 99 °C for 5 min and precipitated enzymes were removed by centrifugation (16000 g for 5 min). The supernatant was diluted 1:20 with 50 mM PPB (pH 7.5) and measured using an injection volume of 10 μL, a temperature of 25 °C and a flow rate of 1.5 mL min−1. Elution was performed with a linear gradient from 5 mM to 300 mM PPB (pH 3.2) over 10 min. The column was washed (3 min each) with 600 mM and 5 mM PPB (pH 3.2) after each analysis. Authentic standards were used for calibration.

Capillary Zone Electrophoresis

Capillary zone electrophoresis analyses were performed at 18 °C on an HP 3D CE system (Hewlett Packard, Palo Alto, CA, USA) equipped with an extended light path fused silica capillary (5.6 μm×56 cm) from Agilent and a diode array detector (λ=262 nm). The electrophoresis buffer was 20 mM sodium tetraborate (pH 9.3). The capillary was conditioned each day using the following protocol: 10 min NaOH 1 M, 10 min NaOH 0.1 M, 10 min H2O, 15 min electrophoresis buffer. Prior to each sample, the capillary was pre-conditioned with 2 min H2O, 2 min NaOH 0.1 M, 3 min H2O and 10 min electrophoresis buffer. Samples were injected by pressure (50 mbar, 5 s) and measured using a protocol with a voltage of 30 kV for 10 min, 15 kV for 3 min and 30 kV for 8 min. Preparation of the samples was done according to HPLC analysis except that caffeine was added as internal standard. Authentic standards were used for calibration.

Proton NMR Spectroscopy

Spectra were recorded on a Bruker DRX-600 AVANCE spectrometer (Bruker, Rheinstetten, Germany) at 600.13 MHz (1H). The 1H NMR spectra were measured at 298.2 K with acquisition of 32 k data points. After zero filling to 64 k data points, spectra were performed with a range of 7200 Hz. 32 1H NMR spectra were recorded in one measurement, using a 5 mm high precision NMR sample tube (Promochem, Wesel, Germany). For evaluation of the spectra ACD/NMR Processor Academic Edition 12.0 (Advanced Chemistry Development Inc., Toronto, Canada) was used.

Photometric Nucleotide Sugar Determination

Assays for UDP-Glc, UDP-GlcUA and UDP-Xyl were linear up to 500 μM of the respective compound, and samples were diluted accordingly prior to analysis.

UDP-Glc was detected using a coupled enzymatic assay of GOD and POD.[24] UDP-Glc was hydrolyzed by addition of glacial acetic acid to the samples, yielding a final concentration of 28.5%, and heating to 99 °C for 10 min. Afterwards, the assay was performed using the hydrolyzed samples containing free glucose. Absorption at λ=420 nm was measured on a Beckman-Coulter DU800 spectrophotometer.

Concentration of UDP-GlcUA was determined using a colorimetric assay described elsewhere.[25] Absorption (λ=525 nm) was measured on a Beckman-Coulter DU800 spectrophotometer.

UDP-Xyl was determined according to the method of Roe and Rice.[26] A hydrolysis step to allow detection of the UDP sugar was performed prior to the colorimetric assay, as described for UDP-Glc. Measurement was done using the same settings as described for UDP-GlcUA.

Preparative Anion Exchange Chromatography

Purification of the produced sugar nucleotide was done using a cooled (4 °C) BioLogic DuoFlow system (Bio-Rad, Vienna, Austria) equipped with a 6-mL Resource Q anion exchange column. A step-wise gradient of 6 mL min−1 NH4HCO2 (buffer A: 20 mM and buffer B: 500 mM) was used for elution of bound compounds. The steps were as follows: 24 mL NH4HCO2 58 mM, 30 mL NH4HCO2 106 mM, 24 mL NH4HCO2 500 mM. Prior to each run, the column was regenerated by flushing with three column volumes buffer B and buffer A, respectively. UV absorption (λ=254 nm) was used to detect the compounds, which were collected in 6 mL fractions.

The total volume of UDP-Xyl-containing fractions was 48 mL from one reaction batch, which was concentrated to 2 mL on a rotary evaporator (40 °C, 20 mbar) before proceeding with size exclusion chromatography.

Preparative Size Exclusion Chromatography

NH4HCO2 was removed from concentrated UDP-Xyl fractions on a BioLogic DuoFlow system (Bio-Rad) using a self-packed Sephadex G-10 (GE Healthcare) column (bed volume=53 mL, H/D ratio=3.8). Elution was performed with deionized water using a flow rate of 2 mL min−1. UDP-Xyl was detected by UV absorption (λ=254 nm), while conductivity measurement was used for NH4HCO2 detection. Automated fraction collection was used to collect 10.5 mL of pure UDP-Xyl solution. The water was finally removed on a rotary evaporator (40 °C, 3 mbar).

Acknowledgments

Financial support from the Austrian Science Fund FWF (Project W901-B05 DK Molecular Enzymology) is gratefully acknowledged. We thank Regina Kratzer from the Institute of Biotechnology and Biochemical Engineering at Graz University of Technology for xylose reductase. We also thank Prof. Lothar Brecker and Claudia Puchner from the Institute of Organic Chemistry at the University of Vienna for NMR analysis. Special thanks go to Silvia Maitz for her contributions to development of the biocatalytic system.

Supporting Information

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/adsc.201400766.

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re-organized for online delivery, but are not copy-edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

miscellaneous_information

References

- 1a.Mega T. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2007;71:2893–2904. doi: 10.1271/bbb.70240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1b.Mulder H, Dideberg F, Schachter H, Spronk BA, De Jong-Brink M, Kamerling JP, Vliegenthart JFG. Eur. J. Biochem. 1995;232:272–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1c.Park J-N, Lee D-J, Kwon O, Oh D-B, Bahn Y-S, Kang HA. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:19501–19515. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.354209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1d.Paul CJ, Lyle EA, Beveridge TJ, Tapping RI, Kropinski AM, Vinogradov E. Glycoconjugate J. 2009;26:1097–1108. doi: 10.1007/s10719-009-9230-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1e.Eames BF, Singer A, Smith GA, Wood ZA, Yan Y-L, He X, Polizzi SJ, Catchen JM, Rodriguez-Mari A, Linbo T, Raible DW, Postlethwait JH. Dev. Biol. 2010;341:400–415. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.02.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eixelsberger T, Sykora S, Egger S, Brunsteiner M, Kavanagh KL, Oppermann U, Brecker L, Nidetzky B. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:31349–31358. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.386706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Egger S, Chaikuad A, Kavanagh KL, Oppermann U, Nidetzky B. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:23877–23887. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.234682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4a.Voet D, Voet JG. Biochemistry. 3rd edn. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 4b.Thibodeaux CJ, Melançon CE, III, Liu H-w. Angew. Chem. 2008;120:9960–10007. doi: 10.1002/anie.200801204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:9814–9859. doi: 10.1002/anie.200801204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4c.Bülter T, Elling L. Glycoconjugate J. 1999;16:147–159. doi: 10.1023/a:1026444726698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neufeld EF, Hall CW. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1965;19:456–461. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(65)90146-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ishimizu T, Uchida T, Sano K, Hase S. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2005;16:309–311. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cai L. J. Carbohydr. Chem. 2012;31:535–552. [Google Scholar]

- 8a.Bar-Peled M, Griffith CL, Doering TL. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:12003–12008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211229198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8b.Polizzi SJ, Walsh RM, Jr, Le Magueres P, Criswell AR, Wood ZA. Biochemistry. 2013;52:3888–3898. doi: 10.1021/bi400294e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8c.Guyett P, Glushka J, Gu X, Bar-Peled M. Carbohydr. Res. 2009;344:1072–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2009.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8d.Fan D-F, Feingold DS. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1972;148:576–580. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(72)90176-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8e.Mølhøj M, Verma R, Reiter W-D. Plant J. 2003;35:693–703. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8f.Gantt RW, Peltier-Pain P, Thorson JS. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2011;28:1811–1853. doi: 10.1039/c1np00045d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8g.Yang T, Bar-Peled Y, Smith JA, Glushka J, Bar-Peled M. Anal. Biochem. 2012;421:691–698. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2011.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8h.Errey JC, Mukhopadhyay B, Ravindranathan Kartha KP, Field RA. Chem. Commun. 2004:2706–2707. doi: 10.1039/b410184g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8i.Oka T, Jigami Y. FEBS J. 2006;273:2645–2657. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9a.Kotake T, Yamaguchi D, Ohzono H, Hojo S, Kaneko S, Ishida H-k, Tsumuraya Y. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:45728–45736. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408716200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9b.Ohashi T, Cramer N, Ishimizu T, Hase S. Anal. Biochem. 2006;352:182–187. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2006.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tanaka H, Yoshimura Y, Jørgensen MR, Cuesta-Seijo JA, Hindsgaul O. Angew. Chem. 2012;124:11699–11702. doi: 10.1002/anie.201205433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:11531–11534. doi: 10.1002/anie.201205433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11a.Arlt M, Hindsgaul O. J. Org. Chem. 1995;60:14–15. [Google Scholar]

- 11b.Wagner GK, Pesnot T, Field RA. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2009;26:1172–1194. doi: 10.1039/b909621n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11c.Ernst C, Klaffke W. J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:5780–5783. doi: 10.1021/jo034379u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pival SL, Klimacek M, Nidetzky B. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2008;350:2305–2312. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petschacher B, Staunig N, Müller M, Schürmann M, Mink D, De Wildeman S, Gruber K, Glieder A. Comput. Struc. Biotechnol. J. 2014;9:e201402005. doi: 10.5936/csbj.201402005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kadirvelraj R, Sennett NC, Custer GS, Phillips RS, Wood ZA. Biochemistry. 2013;52:1456–1465. doi: 10.1021/bi301593c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chance B. J. Biol. Chem. 1952;194:471–481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neuhauser W, Haltrich D, Kulbe KD, Nidetzky B. Biochem. J. 1997;326:683–692. doi: 10.1042/bj3260683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17a.Wu H, Tian C, Song X, Liu C, Yang D, Jiang Z. Green Chem. 2013;15:1773–1789. [Google Scholar]

- 17b.Riebel BR, Gibbs PR, Wellborn WB, Bommarius AS. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2002;344:1156–1168. [Google Scholar]

- 17c.Geueke B, Riebel B, Hummel W. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2003;32:205–211. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Findrik Z, Presečki AV, Vasić-Rački Đ. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2007;104:275–280. doi: 10.1263/jbb.104.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lange J, Wyser Y. Packag. Technol. Sci. 2003;16:149–158. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Complex Carbohydrate Research Center, CarboSource Services product list, 2014.

- 21.Gokhale UB, Hindsgaul O, Palcic MM. Can. J. Chem. 1990;68:1063–1071. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gottlieb HE, Kotlyar V, Nudelman A. J. Org. Chem. 1997;62:7512–7515. doi: 10.1021/jo971176v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ma X, Stöckigt J. Carbohydr. Res. 2001;333:159–163. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(01)00122-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wildberger P, Luley-Goedl C, Nidetzky B. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:499–504. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Filisetti-Cozzi TMCC, Carpita NC. Anal. Biochem. 1991;197:157–162. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(91)90372-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roe JH, Rice EW. J. Biol. Chem. 1948;173:507–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

miscellaneous_information