Abstract

The study is to establish a novel method to determine the endothelial function in mouse carotid arteries in vivo by using high-resolution ultrasound images. Atherosclerosis in carotid arteries is induced in ApoE−/− mice with a Western diet. The ultrasound of the ventral neck generates clear pictures of the common carotid arteries. Acetylcholine at the range from 5 to 20 μg/kg/min (iv) is able to induce a dose-dependent relaxation as shown by the increased diameter of these normal mouse carotid arteries, which is impaired in atherosclerotic arteries. The endothelial function determined by ultrasound images in vivo matches well with that determined in isolated carotid arterial rings in vitro. All animals are survival after the endothelial function measurement. In this study, we have established a standard method to determine the mouse endothelial function in vivo. It is a reliable, safe and survival method that could be used repetitively in mouse arteries.

Keywords: Ultrasound image, carotid arteries, mouse, atherosclerosis, endothelial function

Introduction

Endothelial dysfunction most commonly refers to impairment of endothelium-dependent vasodilation and implies presence of widespread abnormalities in endothelial integrity and homeostasis [1, 2]. It is well established that endothelial dysfunction is a major mechanism involved in all the stages of atherosclerotic vascular disease and other chronic vascular disorders such as hypertension, diabetic vascular complication, and vascular aging. The assessment of endothelial function and endothelial dysfunction has therefore become a widely used method for risk analysis, diagnosis, prognosis, and therapeutic evaluation of these vascular diseases [1, 4–6].

Although many methods of endothelial function assessment have been developed in the past decade, invasive method to determine coronary or other artery vasomotion in response to infusion of acetylcholine (Ach), and noninvasive ultrasound assessment of flow-mediated vasodilation (FMD) of peripheral arteries are still the two gold methods for the in vivo endothelial function measurement in human and large animals [7, 8].

Mouse models are still the most often used preclinical models for vascular diseases related to endothelial dysfunction. For example, Apo E knockout (ApoE−/−) mice and LDL receptor knockout mice are still the most popular preclinical models for atherosclerosis, due to their genetic similarity to human, quick development of atherosclerotic lesions, easy induction for transgenic and gene knockout modulation, and relatively low cost [9, 10]. Although the relaxation response of isolated mouse aortic and carotid arterial rings to Ach has been used for many years to determine the endothelial function and endothelial dysfunction in mice, the method is a one-time non-survival assessment and is very limited for many studies on vascular diseases [11, 12].

Due to the small anatomical structure of mouse limbs, noninvasive ultrasound assessment of FMD is very difficult to be applied for mouse endothelial function measurement in vivo. In this study, we are trying to establish a novel method to determine the endothelial function in mouse carotid arteries in vivo by using high-resolution ultrasound images and intravenous delivery of Ach. In addition, the new survival in vivo method will be compared with the non-survival isolated vessel-ring method both in wide-type normal mice with normal endothelial function, and in atherosclerotic ApoE−/− mice with endothelial dysfunction.

Methods

Animals and atherosclerotic model

Male ApoE−/− mice (C57BL/6 background) and wild-type C57BL/6 mice were from Jackson Laboratories. The mice were purchased at 5-week-old. At the beginning of 6-week-old, the animals were divided into the following groups: 1) ApoE−/− mice fed with a standard chow diet for 12 weeks; 2) ApoE−/− mice fed with a Western diet (17.5% protein, 20% fat, and 0.15% cholesterol, TestDiet, Richmond, IN), in which approximate 40.1% energy (kcal) was from fat, for 12 weeks; 3) Wild-type C57BL/6 fed with a standard chow diet for 12 weeks. Each group had 9 mice. Mice were housed in plastic cages in a room at 20°C ± 2°C, with a relative humidity of 55% ± 15%, and on a 12/12 hour light/dark cycle with free access to water and diet. All protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Rush University and were consistent with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (updated (2011) version of the NIH guidelines).

Determination of atherosclerosis in aortas and carotid arteries

The animals were euthanized with over dose of pentobarbital (200mg/kg, ip). Then, the carotid arteries, dissected from bifurcation of external and internal carotid arteries, and the aortas, dissected from the aortic arch to the aorticoiliac bifurcation, were fixed in 10% formalin (Sigma-Aldrich). The arteries were freed of adherent connective tissues and then cut longitudinally and stained with oil-red O (Sigma-Aldrich) to visualize the atherosclerotic plaque area (fatty streaks) as described [13].

Measurement of vascular function in mouse carotid arteries in vivo by using high-resolution ultrasound images and intravenous delivery of Ach and sodium nitroprusside (SNP)

Endothelial function in mouse carotid arteries is evaluated in vivo by determining the endothelium-dependent relaxation to Ach via ultrasound images. Briefly, as shown in Figure 1, the animals were mildly anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of 60 mg/kg ketamine and 6 mg/kg xylazine and were placed in dorsal recumbency on a heater blanket (37°C). Their ventral necks and thigh areas of left hind leg were shaved. A PE 10 catheter was inserted into left femoral vein to deliver the experimental solutions via a constant syringe infusion pump. Transcutaneous vascular ultrasounds were then performed on mouse left carotid arteries using a Vevo 770 High-Resolution Imaging System equipped with a 30-MHz transducer (Visual Sonics). The transducer was lubricated with ultrasound gel and placed laterally to the trachea on the ventral neck. The left carotid artery was visualized on the monitor and the image was frozen at the largest cross-section. In this study, we fixed all the measurement at the site in the common carotid artery, which is 1mm far from the beginning point of the shared vascular wall between internal and external carotid arteries. The maximal width of the cross-sectional diameter at the measuring site was measured. Although ultrasound plane might be adjusted during the whole procedure to have maximal diameter, the measure sites were not changed. The protocol for the reagent delivery and vascular function measurement was described as follow: First, injection of vehicle (0.9% saline) for 5 min (to obtain the basal line of vascular diameter); Second, injection of Ach (5μg/kg/min) for 5 min; Third, injection of Ach (10μg/kg/min) for 5 min; Fourth, injection of Ach (20μg/kg/min) for 5 min. To obtain the maximal relaxation response to Ach, a sub-group of mice were given two more dose of Ach (25μg/kg/min and 30μg/kg/min) for 5 min. At the end of each injection, ultrasound was performed to measure the vascular diameters. Finally, at 30 min washout period after the Ach injection, SNP (20 μg/kg/min) was injected for 10 min to determine the endothelium-independent relaxation. The vascular function was calculated and expressed as % increase in vascular diameter after Ach or SNP injection.

Figure 1.

A schematic diagram to show the survival assessment of mouse endothelial function in vivo via ultrasound images.

Vascular function assessments in isolated mouse carotid arteries in vitro

Isometric tension was measured in isolated mouse carotid artery ring segments as described [14]. In brief, the mice (n=9 in each group) were euthanized with over dose of pentobarbital (200mg/kg, ip) and their carotid arteries were isolated. The vessels were cut into individual ring segments (2–3 mm in width) and suspended from a force-displacement transducer in a tissue bath. Ring segments were bathed in Krebs-Henseleit (K-H) solution. The vessels were contracted to 50–60% of their maximal capacity (50–60% of KCl response) with phenylephrine (3×10−8–10−7 M). When tension development reached a plateau, ACh (10−9–3×10−6 M) was added cumulatively to the bath to stimulate endothelium-dependent relaxation. Endothelium-independent relaxation was tested by cumulative addition of the NO donor SNP (10−6 M).

Statistics

The data are reported as the mean ± SE. SPSS was used to perform the statistical analysis. ANOVA repeated measures were used to assess changes within a group, and one-way ANOVA within groups were used to assess the significance of any change between groups. Comparisons between two groups were performed using the independent samples t-test. Statistical significance was accepted at P < 0.05.

Results

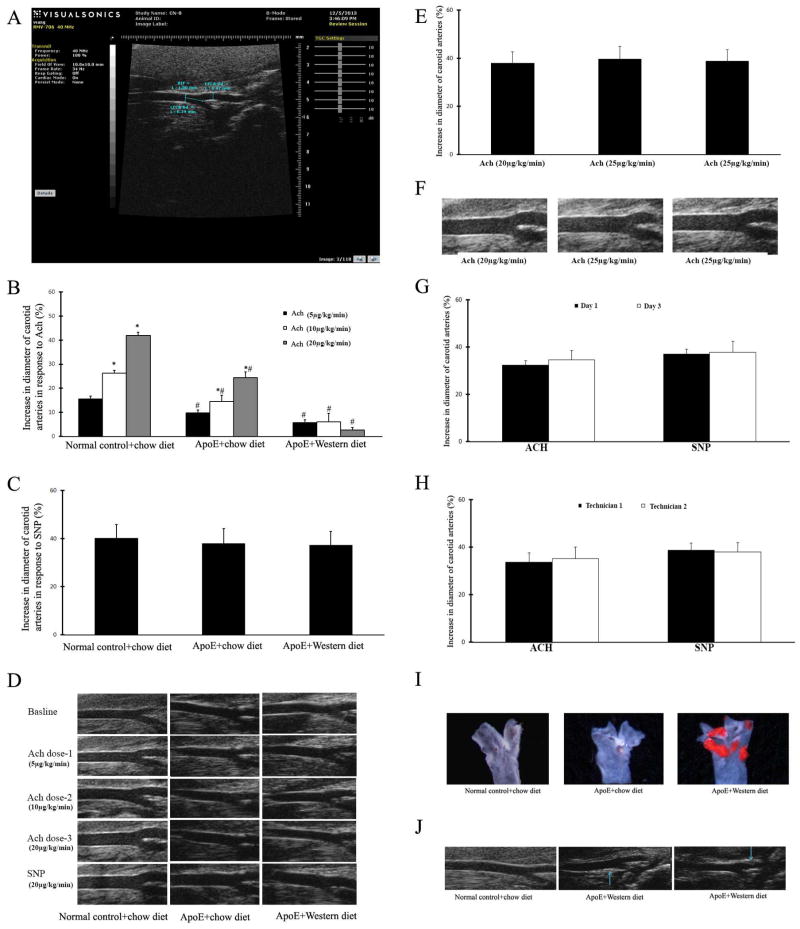

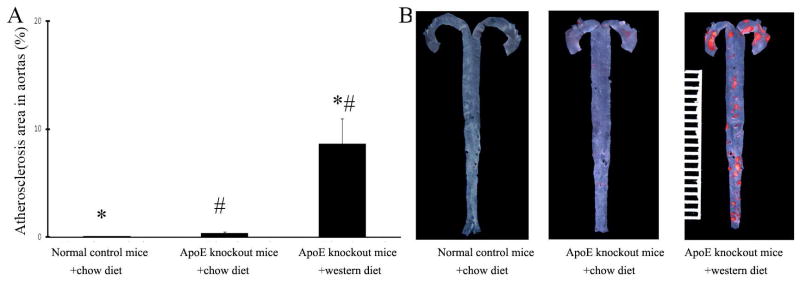

Atherosclerosis is induced in ApoE−/− mice

No oil-red O staining was identified in aortas from wild-type mice with the standard chow diet at 18-week-old. ApoE−/− mice fed with the standard chow diet had small area of atherosclerotic lesions in their aortas. In contrast, atherosclerotic lesions in aortas were clearly demonstrated in the same age of Apo E −/− mice with the 12-week’s Western diet (Figure 2A). Representative Oil-red O stained images of normal control aortas, aortas from ApoE−/− mice fed the standard chow diet, and aortas from ApoE−/− mice fed the western diet were shown in Figure 2B.

Figure 2. Atherosclerosis is induced in ApoE knockout mice with a western diet.

A. Oil-red O stained areas of normal control aortas and in aortas from ApoE knockout mice. Note: n=9; *p<0.05 compared with ApoE knockout mice with chow diet; # p<0.05 compared with wild-type control mice with chow diet. B. Representative Oil-red O stained images of mouse aortas from different groups.

Vascular function in normal mouse carotid arteries determined by ultrasound images

The transcutaneous high-resolution ultrasound of the ventral neck generated clear pictures of the common carotid artery and the bifucation showing internal carotid artery and external carotid artery (Figure 3A). The beginning point of the shared vascular wall between internal and external carotid arteries was then used as a reference location mark for our diameter measurement. In this study, we fixed all the measurement at the site in the common carotid artery, which is 1mm far from the mentioned beginning point as shown in Figure 3A. The depth from the elevational plane of the ultrasound to carotid artery was about 3 mm and the diameter of common carotid artery is about 0.4mm.

Figure 3. Vascular function of mouse carotid arteries determined by using high-resolution ultrasound images in vivo.

A. A ultrasound image showing the left common carotid artery and the bifurcation of internal and external carotid artery. The measuring of diameter at the site in the common carotid artery which is 1mm far from the beginning point of the shared vascular wall between internal and external carotid arteries. B. Increase in diameter of mouse carotid arteries in response to 3 increasing does of Ach. Note: n=9; *p<0.05 compared with lowest dose; # p<0.05 compared with wild-type control mice. C. Increase in diameter of mouse carotid arteries in response to SNP. D. Representative ultrasound images of mouse carotid arteries at baseline, and after different doses of Ach and SNP. E. Ach at any dose higher than 20μg/kg/min could not result in additional increase in vessel diameter in normal mouse carotid arteries. F. Representative ultrasound images of mouse carotid arteries from normal mice treated with Ach at 20μg/kg/min, 25μg/kg/min, or 35μg/kg/min. G. Vascular responses of carotid arteries to Ach and SNP in a same group of normal mice determined at different time (n=6). H. Vascular responses of carotid arteries to Ach and SNP in a same group of normal mice determined by two independent technicians (n=6). I. Representative Oil-red O stained images of mouse carotid arteries from different groups. J. Representative ultrasound images showing normal carotid artery without atherosclerotic lesion from wild type mouse and atherosclerotic carotid artery with atherosclerotic lesion from ApoE knockout mouse with the Western diet.

After 2 min of vehicle injection (0.9% saline) at 1.5 μl/min, carotid arteries would have stable vessel diameter at least for 2 hours. We thus used the vessel diameter at 5 min after vehicle injection as the baseline. Ach at the range from 5μg/kg/min to 20μg/kg/min was able to induce a dose-dependent relaxation as shown by the % increase in the diameter of these common carotid arteries (Figure 3B). As expected, after 30 min washout period of Ach, SNP (20 μg/kg/min) induced an endothelium-independent relaxation in normal mouse carotid arteries (Figure 3C). Representative ultrasound images of normal carotid arteries at baseline, and after different doses of Ach and SNP were shown in Figure 3D. In addition, Ach at any dose higher than 20μg/kg/min could not result in additional increase in vessel diameter (Figure 3E and 3F).

To determine the reproducibility of the functional measurements, vascular function was measured again two days after first measurement in a subgroup of mice. As shown in Figure 3G, no significant difference was identified in vascular function between the two time points of the measurement. To further test the reproducibility of the functional measurements, we arranged two technicians to measure the vascular function in a same group of mice, as shown in Figure 3H, no significant difference was identified in vascular function determined by two independent technicians.

Vascular function in atherosclerotic mouse carotid arteries by ultrasound images

In consistent with the atherosclerotic lesions in aortas, the western diet induced atherosclerosis in mouse carotid arteries of ApoE−/− mice as shown by histology in Figure 3I and ultrasound image in Figure 3J. Accordingly, the endothelium-dependent relaxation to Ach in atherosclerotic carotid arteries was significantly impaired in these ApoE−/− mice fed with the western diet (Figure 3B). In addition, the endothelium-dependent relaxation in carotid arteries of ApoE−/− mice fed with the standard chow diet was mildly impaired, compared with that in normal mice, but it is much better than that in ApoE−/− mice fed with the western diet (Figure 3B). In contrast, the endothelial-independent relaxation to SNP was not changed in these atherosclerotic carotid arteries, compared with that in normal carotid arteries from wild type mice with normal diet (Figure 3C). Representative ultrasound images of ApoE−/− mouse carotid arteries at baseline, and after different doses of Ach and SNP were shown in Figure 3D.

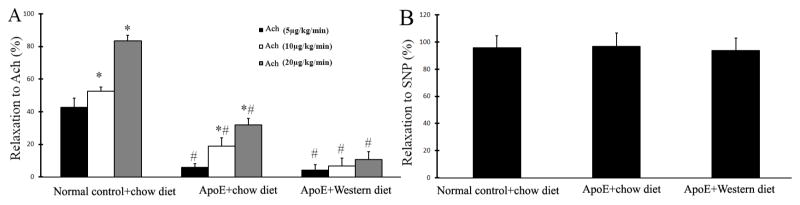

Comparison of vascular functions determined by ultrasound image in vivo and by isometric tension measurement in isolated mouse carotid arteries in vitro

Vascular function was also determined by isometric tension measurement in isolated mouse carotid arteries in vitro. As shown in Figure 4A, in consistent with the result from ultrasound images in vivo, Ach induced a dose-dependent relaxation in normal carotid arteries from wild type mice with the normal diet as shown by the decreased isometric tension. However, the dose-dependent relaxation to Ach was significantly impaired in atherosclerotic carotid arteries from ApoE−/− mice fed with the western diet, which is consistent with that from in vivo measurement by ultrasound images. In addition, the endothelium-dependent relaxation in carotid arteries of ApoE−/− mice fed with the standard chow diet was partially impaired, compared with that in normal mice, but it is much better than that in ApoE−/− mice fed with the western diet (Figure 4A). Again, the endothelium-independent relaxation to SNP was not altered in these atherosclerotic mouse carotid arteries, compared with that in normal mouse carotid arteries (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. Vascular function of mouse carotid arteries determined by isometric tension measurement in isolated mouse carotid arteries in vitro.

A. Relaxation of mouse carotid arteries in response to 3 increasing does of Ach. Note: n=9; *p<0.05 compared with the group of mice treated with the lowest dose of Ach (5μg/kg/min); # p<0.05 compared with the group of normal control mice treated with the same dose of Ach. B. Relaxation of mouse carotid arteries in response to SNP.

Discussion

In vivo survival repetitive assessment of mouse endothelial function is critical for risk analysis, diagnosis, prognosis, and therapeutic evaluation of many vascular disorders such as atherosclerosis, diabetic vascular complication, hypertension and vascular aging [1, 4–6]. Although ultrasound images have been widely used as noninvasive methods to determine endothelial function in vivo in human and large animals, their application in mice is still a challenge due to the small site of the mouse vessels, the limited exposure area of superficial arteries, limited skin area for ultrasound transducer and blood flow modulation, and high heart rate. To the best of our knowledge, no report has been reported thus far to use ultrasound images as the method to determine endothelial function of mouse arteries in vivo, although the quality of ultrasound images in small animals has been significantly improved in the past 10 years.

Carotid arteries are relative big arteries in mice. In addition, the skin area in mouse neck is flat and big enough for an ultrasound transducer of the Vevo 770 High-Resolution Imaging System. Moreover, carotid arteries are well studied arteries of mice in many vascular diseases. Indeed, we found in this study, the atherosclerosis was induced in carotid arteries from ApoE−/− mice fed the western diet. We thus selected carotid artery as the vessel for mouse endothelial function measurement by ultrasound images. To avoid any interference from the drug delivery catheter, we selected femoral vein as our delivery site because it is far away from the neck area.

To test other mouse arteries that might be used for the vascular function measurement by the ultrasound images, we have tried femoral artery and abdominal aorta. Femoral artery is too small to be imaged clearly by the ultrasound. The responses of abdominal aorta to Ach and SNP near the bifurcation of the abdominal aorta and common iliac arteries are as good as these determined in carotid arteries (Data not shown). However, abdominal aorta is difficult to be imaged clearly by the ultrasound due to many tissues such as intestines are located between the ultrasound transducer and the aorta. Thus, carotid artery is the best vessel and the neck area is the best location to determine the vascular function in vivo by the ultrasound images in mice.

The transcutaneous high-resolution ultrasound could generate clear pictures of the common carotid artery and the bifurcation showing internal carotid artery and external carotid artery. Ach induces a dose and endothelium-dependent relaxation, which reflexes normal endothelial function. However, the endothelial function is significant impaired in atherosclerotic mouse carotid arteries as shown by the decreased relaxation to Ach in ultrasound images. SNP, a nitric oxide donor, could induce an endothelium-independent relaxation both in normal and atherosclerotic mouse carotid arteries determined by ultrasound images. The excellent reproducibility of the measurements of vascular function via ultrasound images is confirmed by the consistent results measured at different times and by different technicians in a same group of mice.

Isometric tension measurement of isolated artery rings is a traditional non-survival method to determine the endothelial function in mouse arteries in vitro as described previously [14]. To further evaluate the reliability of the in vivo assessment of mouse endothelial function by ultrasound images, we also measured their isometric tension changed in response to Ach and SNP in these isolated mouse carotid arteries. Our results revealed that the endothelial function determined by ultrasound images in vivo matches very well with the result determined by isometric tension measurement in vitro.

Survival and repetitive assessment of mouse endothelial function is required for some vascular studies. For example, atherosclerosis, hypertensive vascular disease and vascular aging are all chronic vascular disorders, in which endothelial dysfunction is an important marker. The procedures of mild anesthesia (60 mg/kg ketamine and 6 mg/kg xylazine), iv injection, and ultrasound measurement are safe. No animal was died by the measurement procedures. Thus, it is suitable for the survival and repetitive assessment of mouse endothelial function.

In summary, in this study, we have established a standard method to determine the mouse endothelial function in vivo by the transcutaneous high-resolution ultrasound images. It is a reliable, safe and survival method that could be used repetitively in atherosclerotic vascular diseases or other diseases with endothelial dysfunction in mouse models.

Clinical relevance of the study

Endothelial dysfunction is a chronic complex process involved in all the stages of human atherosclerotic vascular disease. Mouse models of endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis are still the most often used preclinical models. A reliable, safe and survival method to repetitively determine endothelial function and dysfunction in mice described in this study will be helpful to evaluate the effects any clinical treatments or preventive interventions on endothelial function and atherosclerosis.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (HL095707, HL109656, and NR013876) to C. Zhang.

Abbreviations

- Ach

Acetylcholine

- FMD

Flow-mediated vasodilation

- SNP

Sodium nitroprusside

Footnotes

Disclosures

None

Human subjects/informed consent statement

No human studies were carried out by the authors for this article

Animal Studies

The work was conducted with the approval and in accordance with the guidelines of the Rush University. All institutional and national guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals were followed and approved by the university institutional committees.

References

- 1.Sima AV, Stancu CS, Simionescu M. Vascular endothelium in atherosclerosis. Cell Tissue Res. 2009;335:191–203. doi: 10.1007/s00441-008-0678-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mudau M, Genis A, Lochner A, Strijdom H. Endothelial dysfunction: the early predictor of atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2012;23:222–231. doi: 10.5830/CVJA-2011-068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garcia MM, Lima PR, Correia LC. Prognostic value of endothelial function in patients with atherosclerosis: systematic review. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2012;99:857–865. doi: 10.1590/s0066-782x2012005000078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Landmesser U, Drexler H. Endothelial function and hypertension. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2007;22:316–320. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e3281ca710d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Georgescu A, Alexandru N, Constantinescu A, Titorencu I, Popov D. The promise of EPC-based therapies on vascular dysfunction in diabetes. Eur J Pharmacol. 2011;669:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Higashi Y, Kihara Y, Noma K. Endothelial dysfunction and hypertension in aging. Hypertens Res. 2012;35:1039–1047. doi: 10.1038/hr.2012.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Faulx MD, Wright AT, Hoit BD. Detection of endothelial dysfunction with brachial artery ultrasound scanning. Am Heart J. 2003;145:943–951. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8703(03)00097-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lockowandt U, Liska J, Franco-Cereceda A. Short ischemia causes endothelial dysfunction in porcine coronary vessels in an in vivo model. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;71:265–269. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(00)02253-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mu Zadelaar S, Kleemann R, Verschuren L, de Vries-Van der Weij J, van der Hoorn J, Princen HM, Kooistra T. Mouse models for atherosclerosis and pharmaceutical modifiers. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:1706–1721. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.142570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jawień J, Nastałek P, Korbut R. Mouse models of experimental atherosclerosis. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2004;55:503–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen X, Zhang H, McAfee S, Zhang C. The reciprocal relationship between adiponectin and LOX-1 in the regulation of endothelial dysfunction in ApoE knockout mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;299:H605–612. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01096.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lesniewski LA, Connell ML, Durrant JR, Folian BJ, Anderson MC, Donato AJ, Seals DR. B6D2F1 Mice are a suitable model of oxidative stress-mediated impaired endothelium-dependent dilation with aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64:9–20. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gln049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang H, Zhang W, Zhu C, Bucher C, Blazar BR, Zhang C, Chen JF, Linden J, Wu C, Huo Y. Inactivation of the Adenosine A2A Receptor Protects Apolipoprotein E-Deficient Mice From Atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:1046–1052. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.188839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guo Y, Zhang C, Nair U, Du X, Yoo TJ. The morphological and functional alterations of the cochlea in apolipoprotein E deficient mice. Hear Res. 2005;208:54–67. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]