Most children in the U.S. grow up with a sibling, and research shows that sibling relationships are both unique and uniquely related to individual development and adjustment (McHale, Updegraff, & Whiteman, 2012). Siblings are often close, developing a common history through their years of shared family experiences and environments (Stocker, Burwell, & Briggs, 2002). Siblings’ frequent contact and companionship can produce relationships characterized by intense conflict and intimacy (Dunn, 1983). Living with a sibling also provides unique opportunities for interaction between individuals who differ in age, gender, and personality. This obligatory exposure may be particularly influential for mixed-gender sibling pairs, as the presence of an opposite-gender sibling can temper the gender segregation that is common in middle childhood, providing natural opportunities to observe and interact with an opposite-gender peer (Maccoby, 1990).

The intensity and duration of sibling bonds make this relationship especially influential: A body of research documents the influences of sibling relationships in areas ranging from friendship to academic engagement and risky behavior (Stocker, 2000; Slomkowski, Conger, Rende, Heylen, Little, & Shebloski, 2009). Although much of the sibling literature focuses on childhood, sibling relationships are the longest lasting relationships in most people’s lives, and their influence is evident across the lifespan (Waldinger, Vaillant, & Orav, 2007). This potential for lifelong influence directs attention to siblings’ role in domains of development that emerge after childhood. This study expands upon the research on sibling influences by examining links between sibling experiences and romantic relationships in late adolescence. Romantic relationships typically begin in adolescence and develop through adulthood (Collins, Welsh, & Furman, 2009). Although connections between sibling and peer relationships in childhood and adolescence have been documented (Kim, McHale, Crouter, & Osgood, 2007; Lockwood, Kitzmann, & Cohen, 2001), we know very little about links between sibling and romantic relationships. Similarities between these relationships, however, give reasons to expect that characteristics of sibling relationships may set the stage for romantic relationships later on.

Just as navigating sibling relationships is considered a normative aspect of youth development, romantic relationships are a normative part of adolescence in Western societies. Romantic relationships often begin in mid-to-late adolescence, with 36% of 13-year-olds, 53% of fifteen-year-olds, and 70% of 17-year-olds reporting involvement in a romantic relationship in the past 18 months (Collins et al., 2009). Like sibling relationships, adolescent romantic experiences are linked to aspects of individual development and adjustment, including identity formation, harmonious peer relationships, and sexual identity development (Collins et al., 2009). Adolescents’ romantic relationships often take place after a period of gender segregation, which serves to emphasize and intensify gender differences—often to the detriment of cross-gender communication and social competence, as girls and boys have developed different approaches toward interpersonal intimacy (Maccoby, 1990). Adolescents must learn to navigate the intricacies of cross-gender relationships, despite this gap in comfort and experience with intimacy. The current study examines whether this task may be easier for adolescents with exposure to an opposite-gender sibling, given early research suggesting that this may reduce gender stereotyping (Koch, 1955; Brim, 1958).

Given the prevalence, intensity, and influence of youth’s sibling and romantic relationships, a better understanding of the potential links between these relationships could enhance our overall understanding of adolescent socioemotional development and well-being. Accordingly, the goals of this study were to: (1) examine whether sibling relationship qualities—conflict, intimacy, and control—measured in middle adolescence, predicted qualities of romantic relationships—specifically intimacy and relative power—in late adolescence, and (2) to examine sibling gender constellation and adolescent gender as potential correlates and moderators of these linkages. Below, we consider some of the similarities between romantic and sibling relationships that give reason to predict these linkages.

Companionship in Sibling and Romantic Relationships

One feature shared by both sibling and romantic relationships is the centrality of each in the lives of adolescents. Sibling relationships are often the first peer-like relationship children experience, and for this reason siblings may be influential in establishing the capacity to form secure relationships (Collins & Sroufe, 1999; Scharf & Mayseless, 2001). Siblings and sibling relationships also play a role in shaping early activities and experiences. Children spend a large portion of their non-school time in the presence of their sibling—allowing for ample interaction and influence (McHale et al., 2012). The amount of time spent with a sibling fluctuates over development, as children gain the ability and independence needed to enter into relationships and activities beyond the family and home (Larson & Verma, 1999). However, adolescents continue to spend significant amounts of time in the presence of their siblings, and these relationships sustain their importance through continued accumulation of shared experiences and understanding. As the meaning and importance of sibling relationships evolve and grow, so does their potential to impact siblings’ individual development and adjustment.

Romantic relationships can also consume large portions of adolescents’ time and companionate activities. Interest in opposite-gender peers begins to increase in early adolescence and is reflected in an increase in time spent within mixed-gender social groups (Richards, Crowe, Larson, & Swarr, 1998). Eventually, romantic partners eclipse family members as the recipients of adolescents’ time and attention, as adolescents spend more of their time with romantic partners than with friends, siblings, or parents (Laursen & Williams, 1997).

Emotional Ties in Sibling and Romantic Relationships

Another prominent and shared feature of romantic and sibling relationships is the intensity of emotion—both positive and negative—that these relationships provoke. Unlike friendships, sibling relationships are non-voluntary in childhood and adolescence. Siblings are often close in age, and may be able to interact with and understand each other in cohort specific ways as they mature and face developmental challenges and milestones in similar micro-environments and as members of the same age cohort in their families. Sibling intimacy can be seen in the emergence of nurturant behaviors between siblings; sibling relationships also play a role in the development of social skills and abilities in childhood, serving as an opportunity to learn and practice relating to others (Lewis, 2005). Sibling relationships characterized by healthful and mutual intimacy have positive implications for subsequent relationships, which benefit from individuals’ enhanced social skills and capacity for intimacy (Lockwood et al., 2001). By influencing the nature of the social scripts and expectations that are internalized, siblings may extend an influence over each other’s romantic relationship qualities.

As adolescents’ social circles expand and their interest in opposite-gender peers increases, their relationship skills are applied to romantic relationships (Lewis, 2005). Romantic relationships in adolescence are thought to fulfill a similar developmental function as sibling relationships do in childhood—providing opportunities to develop understanding of and capacity for intimacy and nurturance (Seiffge-Krenke, & Connolly, 2010). Romantic relationship qualities in adolescence are of theoretical importance due to their association with later romantic relationship experiences and outcomes in early adulthood (Furman & Collins, 2009).

Sibling and romantic relationships can be congruent or compensatory in nature, though we know little about such patterns (Updegraff, McHale, & Crouter, 2002). One study suggested that the relationship skills learned through a positive sibling relationship may enhance capacity for relationship skills and positive peer relationships—a congruent pattern (Lockwood et al., 2001). Although not yet studied, this effect may be pronounced for mixed-gender sibling pairs, as the presence of an opposite-gender sibling during the gender-segregated phase of middle childhood may mitigate awkwardness in interactions with opposite-gender peers in adolescence (Maccoby, 1990). It also seems that sibling and peer relationships can compensate for each other: forming positive peer relationships, including with a romantic partner, has been shown to compensate for the lack of satisfying sibling relationships (Sherman, Lansford, & Volling, 2006).

Power and Control in Sibling and Romantic Relationships

A dimension of sibling relationships that distinguishes them from parent-child relationships with parents is their role structure—which often dictates relational power dynamics. Sibling relationships can be egalitarian, when siblings serve as playmates and companions with equal power, or they can be hierarchical, with one or both siblings striving to achieve dominance. In Western society, the role structure of the sibling dyad is much less proscribed than in other cultures, so sibling pairs must work out power dynamics (McHale et al., 2012). This may involve an ongoing process of negotiation, as the power balance between siblings shifts over time, particularly when age differences reflect progressively smaller developmental differences between siblings in adolescence.

Exposure to and adeptness with ongoing power negotiations in a sibling context may prove influential in later romantic relationships, as negotiation of power and control also occurs in romantic relationships. As with sibling relationships, romantic relationships can be egalitarian, with control being shared between partners (Collins et al., 2009). As gender roles have become more egalitarian in Western societies, adolescents may increasingly form romantic relationships with more egalitarian role structures and power dynamics. Each partner’s social skills may play an important role in helping a couple negotiate and maintain a balance of power that both parties find satisfactory. This process may be particularly evident in romantic relationships that occur in adolescence, when youth explore a range of relational power dynamics before establishing personal patterns of romantic behaviors and roles. Unequal levels of power in a romantic relationship, however, may indicate unhealthful levels of over- or under–investment in a relationship (Rusbult, Martz, & Agnew, 1998; Felmlee, 1994; Sprecher, 1985). By allowing youth to develop a capacity for power negotiation, previous experiences with a sibling may prove influential in the context of a romantic relationship.

Conflict in Sibling and Romantic Relationships

High rates of teasing, arguments, and physical aggression between siblings are common (Shantz & Hobart, 1989; Dunn, 1983), and sibling conflict predicts negative psychological and social outcomes (Stocker et al., 2002; Rinaldi & Howe, 1998). Negative sibling relationships can also lead to coercive patterns of social behavior (Patterson, 1986). These findings are consistent with both social learning and attachment theory predictions, which hold that early relational patterns transfer to later relationships. In contrast, some evidence suggests that conflict between siblings serves to enhance social and communication skills, as well as negotiation, compromise, and perspective-taking abilities (Bedford, Volling, & Avioli, 2000). Successfully negotiating sibling conflict may provide adolescents with the skills needed to resolve conflict in romantic relationships. That is, through repeated experiences of conflict and conflict resolution, siblings may hone these important social competencies. Sibling conflict may also make forming attachments with romantic partners more appealing to adolescents—a compensatory pattern (Updegraff et al., 2002). Thus, paradoxically, experiencing sibling conflict may lead to more positive romantic relationship outcomes.

Romantic relationships often also involve conflict. Although sibling conflicts can be resolved through the assertion of dominance without leading to relationship dissolution, conflicts in romantic relationships require adolescents to balance their own interests with those of their partner to maintain the relationship (Laursen, Finkelstein, & Betts, 2001). In relationships in which conflict is not dealt with effectively, adolescents are at risk for further conflict and even violence (Sadeh, Javdani, Finy, & Verona, 2011). Successfully handling conflict is thus important for sustaining healthful romantic relationships (Shulman, Tuval-Mashiach, Levran, & Anbar, 2006). By providing exposure to and practice with conflict negotiation, sibling relationships may alter the way one approaches conflict in future romantic relationships.

Present Study

In sum, the purpose of this study was to explore the links between sibling and romantic relationships. We examined whether qualities of sibling relationships in middle adolescence, specifically, conflict, intimacy, and control would predict intimacy and relative power in romantic relationships in later adolescence. We also tested the role of sibling gender constellation in romantic relationships and gender constellation and adolescent gender as potential moderators of the associations between sibling and romantic relationship qualities. Given the lack of prior research, we did not advance hypotheses about the direction of the associations, i.e., whether patterns linking relationship qualities would be positive or negative, but based on Maccoby’s (1998) arguments about the implications of gender segregation in middle childhood for later romantic experiences, we did expect that youth from opposite gender sibling dyads would be better able to negotiate romantic relationships and thus would report more positive romantic relationship experiences than those from same gender dyads. Consistent with the literature, we also expected adolescent girls to report higher levels of sibling intimacy than boys. In order to address potential third-variable influences, the analyses also included a number of control variables. Adolescent expressivity was included in an effort to account for variation in personal qualities that could account for more positive experiences in both sibling and romantic relationships; self-rated expressivity also may mark social desirability biases. Parent-adolescent intimacy was included as a control so that we could determine whether effects of sibling relationship characteristics emerged beyond the effects of parent-child relationships.

Method

The data were drawn from a sample of 203 adolescents who participated in a longitudinal study of family relationships. Data collection began in 1995–1996, and follow-up data collection was conducted each year. Data for the current study were drawn from the sixth and eighth waves of the study (referred to as Time 1 and Time 2), in which the measures of interest were collected.

Participants

Families were initially recruited through letters sent home from schools to families of fourth and fifth graders. These letters described the study and criteria for participation, and interested families returned a self-addressed postcard. Of those families that returned postcards and met our criteria, over 90% agreed to participate. Eligible families included always married couples whose two eldest children were no more than four years apart in age. Participating families were primarily middle- and working-class and resided in rural areas, towns, and small cities in a northeastern state. Most (97%) were European American (3% were Asian American or Latino). Although the sample is not representative of U.S. families, it is representative of the racial background of families from the region where data were collected (McHale, Updegraff, Helms-Erikson, & Crouter, 2001).

Nine families had dropped out of the study before phase six, leaving 194 families (95.6%) at Time 1 for this study. An additional 11 adolescents failed to provide information at one of the two phases of interest, prompting their removal from the sample. Given research documenting family and romantic relationship differences between heterosexual youth and lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth (e.g., Patterson & D’Augelli, 1994), six other adolescents were dropped from these analyses because they reported involvement in same-gender romantic relationships. Of the remaining 177 youth, 125 (65 girls, 60 boys) reported at Time 2 that they were involved in a romantic relationship either currently or within the past year and provided data on the characteristics of their most recent, longest lasting, heterosexual romantic relationship. The analyses were based on data from these 125 adolescents. At Time 1, these adolescents averaged16.52 (SD = .77) and at Time 2 they averaged 18.43 years of age (SD = .76). Among girls, 31 had a younger sister and 34 had a younger brother, whereas 28 boys had a younger sister and 32 had a younger brother. On average, adolescents were 2.66 years (SD=.88) older than their siblings. T-tests showed that these 125 adolescents did not differ from adolescents not in romantic relationships on the basis of gender, X2 (1, N=176) = 0.90, age, t (176) = 0.48, or parents’ income, t (166) = 0.55.

Procedure

Individual home interviews were conducted with adolescents and parents, during which parents reported on family background characteristics and their parent-child relationships, and adolescents reported on their personal qualities and their sibling and romantic relationship experiences. At each home interview, informed consent/assent was obtained, and the families were paid an honorarium for their participation.

Measures

Sibling relationship characteristics

Information on sibling relationship characteristics was collected at Time 1. Sibling intimacy was assessed using an eight-item measure developed by Blyth, Hill, and Thiel (1982) on which adolescents used a scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much) to rate items such as, “How much do you share your inner feelings or secrets with your brother/sister?” Cronbach’s alpha was .83. Sibling conflict was assessed using an eight-item scale developed by Stocker and McHale (1992) on which adolescents used a scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much) to rate items such as, “How often do you try to hurt your brother/sister by pushing, punching or hitting him/her?”. Cronbach’s alpha was .72. Perceived control in the sibling relationship was assessed using a nine-item scale developed by Stets (1993) on which adolescents used a scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (very often) to rate items such as, “In our relationship, I am the boss.” Cronbach’s alpha was .75.

Romantic relationship characteristics

At Time 2, adolescents were asked if they had been involved in a romantic relationship lasting at least three months during the past year. If they reported such involvement, they were asked to report on the relationship’s duration, current status, and characteristics. Of those who reported romantic involvement, 82 adolescents stated ongoing involvement, while 43 were no longer in the relationship. These relationships averaged 11.00 months (SD= 9.34) in duration. Although the majority (n = 109, 87.2%) of these relationships began after the sibling relationship data were collected, 16 (12.8%) had begun concurrently or prior to the sibling relationship measurement.

Adolescents’ romantic intimacy was measured with a seven-item scale adapted from Blyth et al. (1982). Again, adolescents used a response scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much) to rate items such as, “How much do/did you share your inner feelings or secrets with your partner?” Cronbach’s alpha was .85. Relative romantic power was measured with a six-item scale adapted from measures developed by Rusbult et al., (1998), Felmlee (1994), and Sprecher (1985). Adolescents used a response scale ranging from 1 (me) to 9 (my partner), to rate items such as, “In general, which of you has/had more power in your relationship? (reverse scored)” with the midpoint (5) representing an egalitarian relationship and high scores reflecting relatively more power held by the adolescent. Cronbach’s alpha was .79.

Control variables

Adolescent expressivity was measured at Time 1 with a six-item subscale from the Antill Trait Questionnaire (Antill, Russell, Goodnow, & Cotton, 1993), on which adolescents used a scale ranging from 1 (Almost never) to 5 (Almost always) to rate how often traits such as sensitivity and kindness described them (e.g., “This is the sort of person who has good manners and is polite to other people”). Cronbach’s alpha was .75. Parent-adolescent acceptance, measured at Time 1, was also treated as a control using the 24 item scale from the parents’ version of the Child’s Report of Parental Behavior Inventory (CRPBI) (Schwarz, Barton-Henry, & Pruzinsky, 1985; Schludermann & Schludermann, 1970). Parents rated such items as (“I am a person who likes to talk with my child and be with him/her much of the time”) on a scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much). Given their correlation (r =.22, p < .01) and in an effort to limit the number of variables in the analyses, mother and father scores were averaged to form a mean score for parent-adolescent acceptance. Cronbach’s alpha was .93.

Results

The results are organized around our research goals: To examine the links between sibling experiences and romantic relationship qualities, and to test the role of sibling gender constellation and adolescent gender as predictors of romantic relationship qualities as moderators and correlates of sibling-romantic relationship quality linkages. Preliminary analyses (see Table 1) showed that scores for each of the sibling relationship indices clustered at about the midpoint of the scales—indicative of sibling relationships involving both warmth and conflict, with both siblings describing themselves as having some degree of control. Adolescents’ romantic relationships were described as high in intimacy and egalitarian, on average, with scores on the romantic power measure clustered around the midpoint (71% averaged between 4 and 6 on this scale, where a 5 represents equal power, and only 9.6% averaged scores higher than 7 or less than 3). Relative romantic power and romantic intimacy were uncorrelated, r = .03.

Table 1.

Means (SDs) and correlations for study variables

| Variables | M (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sibling conflict | 2.59 (.60) | – | ||||

| 2. Sibling intimacy | 2.90 (.63) | −.26** | – | |||

| 3. Sibling control | 2.28 (.60) | .20* | .11 | – | ||

| 4. Romantic intimacy | 4.14 (.61) | −.14 | .11 | .04 | – | |

| 5. Romantic power | 5.08 (1.10) | −.12 | .24** | .11 | .03 | – |

Note. N = 125 for variables 1, 2, 3, and 5. N = 124 for variable 4.

To discern whether and how sibling gender constellation and sibling experiences in middle adolescence predicted romantic relationship qualities in later adolescence, linear regression analyses were conducted. Each of the models included sibling gender constellation and adolescent gender as potential correlates, and we examined interactions between these variables and the sibling relationship measures to determine whether they served as moderators of sibling-romantic relationship linkages. The models also included parent-child acceptance and adolescents’ expressivity as controls. All potential two- and three-way interactions were examined, and those that were non-significant were dropped from the models to avoid inflation of the error term (Aiken & West, 1991). In addition, all models were tested excluding those adolescents whose romantic relationships had begun prior to Time 1. Results did not differ from those found with the larger sample, and thus data for all youth were included in our analyses.

Sibling Intimacy

The model predicting romantic intimacy was significant (see Table 2). The effect of sibling intimacy was non-significant, but gender constellation and adolescent gender were significant predictors, such that adolescents with an opposite-gender sibling and girls reported significantly higher romantic intimacy. No significant interactions emerged in this model. In predicting relative power, the overall model was significant (see Table 2). Here sibling intimacy was a significant positive predictor, but no other effects emerged.

Table 2.

Coefficients (and SEs) for models testing sibling intimacy (age 16) as a predictor of romantic intimacy and power (age 18)

| Variable | Romantic Intimacy | Romantic Power | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| B | SE B | B | SE B | |

| Gender constellation1 | −0.31** | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.19 |

| Adolescent gender2 | −0.28** | 0.11 | 0.28 | 0.21 |

| Intimacy with parent3 | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.26 |

| Expressivity | 0.03† | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.03 |

| Sibling intimacy | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.38* | 0.16 |

| R2 | 0.18 | 0.10 | ||

| F(123) | 5.27*** | |||

| F(124) | 2.32* | |||

p < .1.

p < .05.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .001.

0 = opposite gender and 1 = same gender.

1 = female and 2 = male.

The mean of mother’s and father’s reports of intimacy with their adolescent.

Sibling Conflict

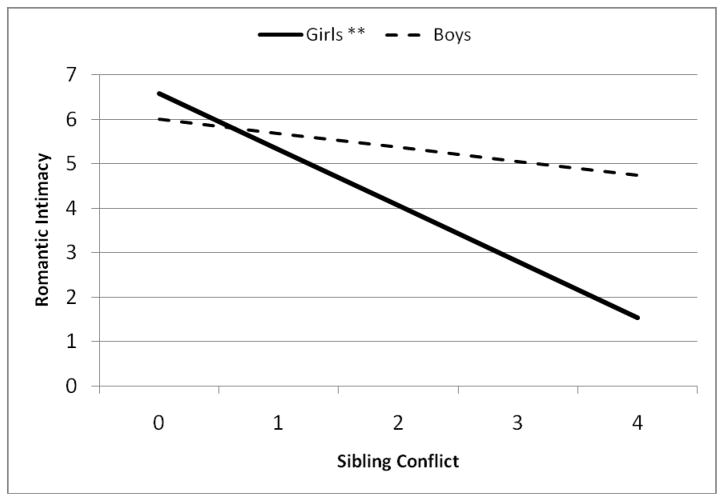

The overall model for romantic intimacy was significant, sibling conflict was a significant negative predictor (see Table 3). An interaction between gender and conflict also emerged (see Figure 1), such that the negative relation between sibling conflict and romantic intimacy was significant for girls, but not for boys. In this model, gender constellation again served as a significant predictor of romantic intimacy. The overall model predicting relative romantic power was not significant (see Table 3), and no significant main effects or interactions emerged.

Table 3.

Coefficients (and SEs) for models testing sibling conflict (age 16) as a predictor of romantic intimacy and power (age 18)

| Variable | Romantic Intimacy | Romantic Power | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| B | SE B | B | SE B | |

| Gender constellation1 | −0.33** | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.20 |

| Adolescent gender2 | −0.29** | 0.10 | 0.20 | 0.21 |

| Intimacy with parent3 | 0.05 | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.27 |

| Expressivity | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.05† | 0.03 |

| Sibling conflict | −0.79** | 0.29 | −0.15 | 0.55 |

| Gender* conflict | 0.48** | 0.17 | 0.02 | 0.34 |

| R2 | 0.23 | 0.05 | ||

| F(123) | 5.92*** | |||

| F(124) | 1.04 | |||

p < .1.

p < .05.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .001.

0 = opposite gender and 1 = same gender.

1 = female and 2 = male.

The mean of mother’s and father’s reports of intimacy with their adolescent.

Figure 1.

Interaction between Sibling Conflict and Adolescent Gender in predicting Romantic Intimacy

Sibling Control

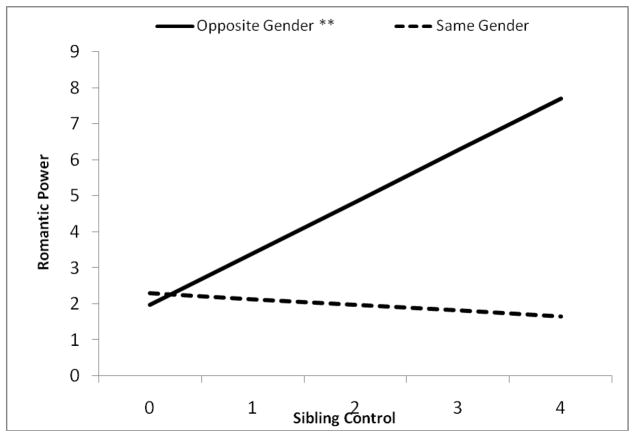

The overall model predicting romantic intimacy was significant (see Table 4); gender constellation and adolescents’ gender, but not sibling control, were significant predictors. The overall model for relative romantic power was also significant, and here, adolescents’ reports of sibling control predicted relatively more power (see Table 4). A gender constellation × sibling control interaction also emerged, however, qualifying the main effect of control. As seen in Figure 2, the positive relation between sibling control and relative romantic power was significant for adolescents from opposite-gender sibling dyads, but not for adolescents from same-gender dyads.

Table 4.

Coefficients (and SEs) for models testing sibling control (age 16) as a predictor of romantic intimacy and power (age 18)

| Variable | Romantic Intimacy | Romantic Power | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| B | SE B | B | SE B | |

| Gender constellation1 | −0.32** | 0.10 | 0.16 | 0.20 |

| Adolescent gender2 | −0.27* | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.21 |

| Intimacy with parent3 | 0.04 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.25 |

| Expressivity | 0.03† | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.03 |

| Sibling control | −0.13 | 0.13 | 0.62** | 0.24 |

| Constellation* control | 0.16 | 0.18 | −0.79* | 0.33 |

| R2 | 0.19 | 0.10 | ||

| F(123) | 4.56** | |||

| F(124) | 2.20* | |||

p < .1.

p < .05.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .001.

0 = opposite gender and 1 = same gender.

1 = female and 2 = male.

The mean of mother’s and father’s reports of intimacy with their adolescent.

Figure 2.

Interaction between Sibling Control and Gender Constellation in predicting Romantic Power

Discussion

This research built on existing literature to examine whether sibling relationship characteristics were linked to romantic relationship qualities in later adolescence and to explore gender constellation and adolescent gender as both predictors of romantic relationship quality and as potential moderators of sibling-romantic relationship linkages. Findings revealed that sibling relationship experiences were related to adolescents’ romantic relationship experiences, explaining variability in romantic relationship qualities after controlling for the effects of parent-child acceptance and youth’s expressivity, which were conceptualized as “third variables” that may have accounted for adolescents’ experiences in both sibling and romantic relationships. Our results revealed no evidence of compensation; instead they suggested that sibling and romantic relationships were congruent: sibling control predicted relative romantic power and sibling conflict was linked to lower levels of romantic intimacy. Results additionally replicated prior research in showing that adolescent gender was linked to romantic relationship qualities—with girls exhibiting higher levels of intimacy. We expanded on this work to show that sibling dyad gender constellation also predicted romantic relationship quality. Consistent with the idea that youth from mixed gender dyads would be advantaged in romantic relationships, youth from mixed gender dyads reported higher levels of intimacy in their romantic relationships. We also expanded on prior research to examine gender moderators of the links between sibling and romantic relationships. We found that sibling control predicted relative romantic power only for youth from mixed gender dyads and that sibling conflict was a negative predictor of romantic intimacy only for girls. Taken together, these results contribute to the literature on sibling influences and also advance understanding of families’ role in a central domain of youth development—romantic relationship experiences.

The Role of Sibling Experiences in Romantic Relationships

Consistent with the idea that youth learn social behaviors in sibling relationships that they can apply in relationships outside the family (Dunn, 1983), adolescents who reported higher levels of sibling intimacy also reported having relatively more power than their partners in romantic relationships. Such findings suggest that close sibling relationships may result in enhanced interpersonal skills and social confidence that are advantageous in forming romantic relationships within which youth feel empowered. Importantly, the modal romantic relationship in this sample was egalitarian, with romantic partners most often described as having equal power, and “high” scores generally reflecting modestly higher levels of power in the target adolescents rather than strongly unbalanced relationships. In other words, high scorers were more likely to feel empowered but not dominant. We also found that sibling control was a significant predictor of relative romantic power—but only for youth from mixed-gender sibling dyads—suggesting that the skills and behaviors that support adolescents’ sense of control in a sibling relationship may also be at work in the context of romantic relationships. That this effect was not significant for adolescents from same-gender sibling pairs suggests that the dynamics related to control learned in same-gender sibling relationships fail to generalize to dyadic relationships with members of the opposite gender.

Of special interest was our finding that sibling gender constellation functioned as a significant predictor of romantic relationship intimacy. Researchers have long speculated about the developmental implications of exposure to an opposite-gender sibling, but these effects are far from being fully understood. Early research suggested, for example, that children with an opposite-gender sibling were more nuanced in their gendered personal traits—a pattern attributed to high levels of exposure, interaction, and role play with an opposite-gender companion (e.g., Koch, 1955; Brim, 1958). Our research yields similar conclusions about the importance of gender constellation in development, but shifts the focus from childhood to adolescence. Given the intensification of gender roles and increased opposite-gender social interaction during adolescence, the impact of sibling gender constellation during this stage of development should be the subject of further research. That adolescents with opposite-gender siblings reported higher levels of romantic intimacy than those from same-gender dyads suggests that adolescents may benefit from long-term social exposure to an opposite-gender sibling, which may temper possible negative impacts of childhood gender segregation on mixed-gender interactions in adolescence (Maccoby, 1990).

Gender differences in romantic relationships in adolescence have been documented in prior research. Our findings showed similar effects, but moved beyond these results to examine adolescent gender as a moderator of the effects of sibling relationship experiences. Findings revealed that there was a negative correlation between sibling conflict and romantic intimacy for girls, but not for boys. Supporting a congruent pattern linking sibling and romantic relationships, this finding implies that high-conflict sibling relationships hinder the development of the social and relational skills needed to form and sustain intimate romantic attachments later on. That the effect of sibling conflict was only significant for girls may be due to girls’ attunement to social relationships—which may make them especially vulnerable to the effects of sibling conflict.

Conclusions

In sum, our research upholds previous research on sibling experiences and their potential impact on adolescent development. At the same time our study expands sibling relationship research in new directions. First, we studied sibling relationship influences in adolescence, a period less frequently examined in the sibling literature. We also expanded on prior work on siblings’ influences to study their effects on romantic relationships. Our conclusions about sibling influences were strengthened by our inclusion of several control variables in the analytic models. By treating parental acceptance as a control variable we were able to conclude that sibling relationship characteristics have predictive value beyond the effects of parent-child relationships, which are known to play a role in both sibling and romantic relationship experiences. Further, including the measure of adolescent expressivity allowed us to account for personal characteristics of youth—sensitivity, kindness, courtesy—that may explain congruence between sibling and romantic relationships, and in addition, to control for social desirability bias in the adolescents’ self-reports. Finally, the use of longitudinal data allowed us to assess sibling relationship qualities as predictors of later romantic relationship qualities. Along these lines, while our research is not experimental in design, the study of gender constellation effects could be construed as a natural experiment in family life. That is, to the extent that the gender of one’s sibling is “randomly assigned,” its effects cannot be attributed to selection factors and thus are suggestive of a causal effect of sibling gender constellation on adolescent development. Our study, however, leaves to future research the investigation of social and family processes set into motion by gender constellation—processes that, for most youth, begin early in life and are the proximal causes of links between gender constellation and romantic relationship outcomes.

In the face of its contributions, several features of our study limit conclusions about the role of sibling experiences in romantic relationships. First, we examined only older adolescents’ reports of their late-adolescent romantic relationships. The processes examined could operate differently for younger siblings—for whom the sibling relationship has been theorized to be more influential (Brim, 1958) —or at different developmental time points, when romantic relationships have different characteristics and significance and when sibling experiences might be more or less influential. Second, including a more diverse sample—both younger and older siblings, a wider range of ages, ethnic groups, and family income levels—would serve to enhance the generalizability of the results, as well as broaden our knowledge of these phenomena.

Although our research represents an important step in exploring how sibling and romantic relationships are linked, much work remains to be done to understand the implications of sibling experiences for adolescent development. Future research should include multiple sources of information about sibling and romantic relationships, thereby minimizing reliance on correlated self-reports. Input from romantic partners would be particularly useful, as two partners may perceive their shared relationship in a different light. Future research should also examine additional parallels and areas of contrast between adolescents’ sibling and romantic relationships, such as the nature of communication styles and patterns, activity involvement, and relationship cognitions. When examining these relationship parallels, it will be important to ensure measurement equivalence across relationships such that correspondent qualities are studied. For example, in this study we used a measure of behavioral control to assess sibling relationships, but an index focused on relative power in the romantic relationship. Measuring the same constructs in both relationships may better illuminate connections between them. It would also be important to examine links across an extended timeframe, as romantic relationships and sibling relationships have been found to fluctuate in intimacy over time (Updegraff et al., 2002), and links between the two may also grow more or less powerful..

Although our research is not conclusive, it represents an important step by documenting the connections that may exist between two fundamental close relationships. As noted, in addition to advancing understanding of sibling relationships, the implications of these findings extend into the family systems and adolescent development literatures. Given the parallels between these two relationships, studying links between sibling and romantic relationship is a promising direction for future research that may illuminate the ways in which family experiences have implications for youth as they turn their attention to the larger social world.

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the Penn State Family Relationships Project for their help in conducting this study and the participating families for their time and insights about their family lives. This work was funded by a grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, RO1-HD32336. Ann C. Crouter and Susan M. McHale were coprincipal investigators.

Contributor Information

Susan E. Doughty, The Pennsylvania State University.

Susan M. McHale, Email: x2u@psu.edu, The Pennsylvania State University, 601 Oswald Tower, University Park, PA 16802, Phone: 814-865-2663, Fax: 814-863-8342

Mark E. Feinberg, Email: mef11@psu.edu, The Pennsylvania State University, 402J Marion Place, State College, PA 16801, Phone: 814-865-8796, Fax: 814-865-6004

References

- Aiken LS, West SG, Reno RR. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Antill JK, Russell G, Goodnow JJ, Cotton S. Measures of children’s sex typing in middle childhood. Australian Journal of Psychology. 1993;45:25–33. doi: 10.1080/00049539308259115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bedford VH, Volling BL, Avioli PS. Positive consequences of sibling conflict in childhood and adulthood. The International Journal of Aging & Human Development. 2000;51:53–69. doi: 10.2190/G6PR-CN8Q-5PVC-5GTV. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blyth DA, Hill JP, Thiel KS. Early adolescents’ significant others: Grade and gender differences in perceived relationships with familial and nonfamilial adults and young people. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1982;11:425–450. doi: 10.1007/BF01538805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchey HA, Shoulberg EK, Jodl KM, Eccles JS. Longitudinal links between older sibling features and younger siblings’ academic adjustment during early adolescence. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2010;102:197–211. doi: 10.1037/a0017487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brim OG. Family structure and sex role learning by children: A further analysis of Helen Koch’s data. Sociometry. 1958;21:1–16. doi: 10.2307/2786054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA, Sroufe LA. Capacity for intimate relationships: A developmental construction. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA, Welsh DP, Furman W. Adolescent romantic relationships. Annual Review of Psychology. 2009;60:631–652. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn J. Sibling relationships in early childhood. Child Development. 1983;54:787–811. doi: 10.2307/1129886. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Felmlee DH. Who’s on top? Power in romantic relationships. Sex Roles. 1994;31:275–295. [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Collins WA. Adolescent romantic relationships and experiences. In: Bukowski W, Laursen B, editors. Handbook of Peer Interactions, Relationships, and Groups. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2009. pp. 341–360. [Google Scholar]

- Gecas V, Longmore MA. Self-esteem. In: Ponzetti JJ Jr, editor. International encyclopedia of marriage and family relationships. 2. New York, NY: Macmillan Reference, USA; 2003. pp. 1419–1424. [Google Scholar]

- Giordano PC, Longmore MA, Manning WD. Gender and the meanings of adolescent romantic relationships: A focus on boys. American Sociological Review. 2006;71:260–287. doi: 10.1177/000312240607100205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, McHale SM, Crouter AC, Osgood DW. Longitudinal linkages between sibling relationships and adjustment from middle childhood through adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43:960–973. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.4.960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch HL. Some personality correlates of sex, sibling position, and sex of sibling among five- and six-year-old children. Genetic Psychology Monographs. 1955;52:3–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson DL, Spreitzer EA, Snyder EE. Social factors in the frequency of romantic involvement among adolescents. Adolescence. 1976;11:7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Larson RW, Verma S. How children and adolescents spend time across the world: Work, play, and developmental opportunities. Psychological Bulletin. 1999;125:701–736. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.125.6.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laursen B, Finkelstein BD, Townsend Betts N. A developmental meta-analysis of peer conflict resolution. Developmental Review. 2001;21:423–449. doi: 10.1006/drev.2000.0531. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laursen B, Williams VA. Perceptions of interdependence and closeness in family and peer relationships among adolescents with and without romantic partners. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis M. The child and its family: The social network model. Human Development. 2005;48:8–27. doi: 10.1159/000083213. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood RL, Kitzmann KM, Cohen R. The impact of sibling warmth and conflict on children’s social competence with peers. Child Study Journal. 2001;31:47–69. [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby EE. Gender and relationships: A developmental account. American Psychologist. 1990;45:513–520. doi: 10.1037//0003-066X.45.4.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHale SM, Updegraff KA, Whiteman SD. Sibling relationships and influences in childhood and adolescence. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2012;74:913–930. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.01011.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHale SM, Updegraff KA, Helms-Erikson H, Crouter AC. Sibling influences on gender development in middle childhood and early adolescence: A longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37:115–125. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.37.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson CJ, D’Augelli AR, editors. Lesbian, gay, and bisexual identities in families. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR. Performance models for antisocial boys. American Psychologist. 1986;41:432–444. doi: 10.1037//0003-066X.41.4.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards MH, Crowe PA, Larson R, Swarr A. Developmental patterns and gender differences in the experience of peer companionship during adolescence. Child Development. 1998;69:154–163. doi: 10.2307/1132077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinaldi C, Howe N. Siblings’ reports of conflict and the quality of their relationships. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly: Journal of Developmental Psychology. 1998;44:404–422. [Google Scholar]

- Rusbult CE, Martz JM, Agnew CR. The investment model scale: Measuring commitment level, satisfaction level, quality of alternatives, and investment size. Personal Relationships. 1998;5:357–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.1998.tb00177.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeh N, Javdani S, Finy MS, Verona E. Gender differences in emotional risk for self- and other-directed violence among externalizing adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011;79:106–117. doi: 10.1037/a0022197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer ES. Children’s reports of parental behavior: An inventory. Child Development. 1965;36:417–424. doi: 10.2307/1126465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharf M, Mayseless O. The capacity for romantic intimacy: Exploring the contribution of best friend and marital and parental relationships. Journal of Adolescence. 2001;24:379–399. doi: 10.1006/jado.2001.0405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schludermann E, Schludermann S. Replicability of factors in Children’s Report of Parent Behavior (CRPBI) Journal of Psychology. 1970;76:239–249. doi: 10.1080/00223980.1970.9916845. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz JC, Barton-Henry ML, Pruzinsky T. Assessing child-rearing behavior: A comparison of ratings made by mother, father, child, and sibling on the CRPBI. Child Development. 1985;56:462–479. doi: 10.2307/1129734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiffge-Krenke I, Connolly J. Adolescent romantic relationships across the globe: Involvement, conflict management, and linkages to parents and peer relationships. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2010;34:97. doi: 10.1177/0165025409360289. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman A, Lansford J, Volling B. Sibling relationships and best friendships in young adulthood: Warmth, conflict, and well-being. Personal Relationships. 2006;13:151–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2006.00110.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shantz CU, Hobart CJ. Social conflict and development: Peers and siblings. In: Berndt TJ, Ladd GW, editors. Peer relationships in child development. Oxford, England: John Wiley & Sons; 1989. pp. 71–94. [Google Scholar]

- Shulman S, Tuval-Mashiach R, Levran E, Anbar S. Conflict resolution patterns and longevity of adolescent romantic couples: A 2-year follow-up study. Journal of Adolescence. 2006;29:575–588. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2005.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slomkowski C, Conger KJ, Rende R, Heylen E, Little WM, Shebloski B. Sibling contagion for drinking in adolescence: A micro process framework. European Journal of Developmental Science. 2009;3:161–174. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprecher S. Sex differences in bases of power in dating relationships. Sex Roles. 1985;12:449–462. doi: 10.1007/BF00287608. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stets JE. Control in dating relationships. Journal of Marriage & the Family. 1993;55:673–685. doi: 10.2307/353348. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stocker CM. Sibling relationships. In: Kazdin AE, editor. Encyclopedia of psychology. Vol. 7. Washington, DC: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 274–279. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stocker CM, Burwell RA, Briggs ML. Sibling conflict in middle childhood predicts children’s adjustment in early adolescence. Journal of Family Psychology. 2002;16:50–57. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.16.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocker CM, McHale SM. The nature and family correlates of preadolescents’ perceptions of their sibling relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1992;9:179–195. doi: 10.1177/0265407592092002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Updegraff KA, McHale SM, Crouter AC. Adolescents’ sibling relationship and friendship experiences: Developmental patterns and relationship linkages. Social Development. 2002;11:182–204. doi: 10.1111/1467-9507.00194. [DOI] [Google Scholar]