Key Clinical Message

We report a case of a 9-year-old female with known end-stage kidney disease who presented with sudden onset tongue swelling. A diagnosis of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced angioedema related to bradykinin accumulation was made. Her symptoms resolved shortly after discontinuation of captopril. Early diagnosis can save patients from severe upper airway obstruction.

Keywords: Adverse reaction, angioedema, angiotensinogen-converting enzyme inhibitor, captopril

Introduction

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi) are a well-known cause of angioedema in adults. Angioedema is characterized by edema or erythema, and it most commonly occurs in the orofacial and/ or perioral region and/or upper respiratory tract. While numerous cases of ACEi-induced angioedema in adults have been published 1, there are few reported cases in children 2–5. In this report, we present the case of a 9-year-old girl who developed angioedema after ACEi administration. We emphasize the importance of early diagnosis and management of such cases.

Case Presentation

The patient was a 9-year-old Somalian girl who was followed up for end-stage renal disease of unknown etiology that was diagnosed 6 months prior to presentation. Her history was remarkable for:

Hemodialysis thrice weekly (in another hospital), of which the last session was conducted 1 day prior to her presentation at our hospital

Lower limb deep vein thrombosis, 4 months previous to presentation

Global developmental delay

Tricuspid regurgitation and dilatation of the left atrium and ventricle

Her medications in the previous 6 months included: Oral warfarin 5 mg once daily, oral captopril 12.5 mg three times daily, oral atenolol 25 mg twice daily, oral calcium carbonate 600 mg three times daily, oral amlodipine 10 mg once daily, oral sodium bicarbonate 20 mEq four times daily, intravenous recombinant human erythropoietin 4000 IU three times weekly, oral alfacalcidol 0.25 mcg once daily, and oral folic acid 5 mg once daily

Renal diet following diagnosis of ESRD, and she had not had a new diet since then

Consanguinity between parents and seven other healthy siblings

The patient presented to the Emergency Room of King Abdulaziz University Hospital with a 3-day history of fever and cough. She reported waking up with lingual swelling, which gradually increased over 4 h. She had no complaint of previous allergic manifestations or reactions and no recent insect bite.

The patient's initial vital signs were as follows: temperature, 38.5°C; heart rate, 90 beats per minute; blood pressure, 112/65 mm/Hg; and oxygen saturation, 95% on room air. On examination she was conscious and alert (Glasgow Coma Scale, 15/15). She had mild respiratory distress, palpable pulses, good perfusion, and pitting edema of both lower extremities, which extended up to her thighs. She had lingual swelling and mild periorbital swelling and no signs of inflammation (Fig.1A and B).

Figure 1.

Lingual and orofacial angioedema due to captopril (A). Three-dimensional reconstruction image of the patient by volume rendering technique (B). Complete resolution of the angioedema 7 days after initiation of treatment (C).

Chest examination revealed fine crepitation over both lung fields. Her abdomen was distended, and further examination was suggestive of ascites. A provisional diagnosis of angioedema due to captopril use was made, and the medication was discontinued as a result.

She was immediately started on oxygen (6 L per minute), and she was seen by an otolaryngologist, the pediatric intensivist and nephrology teams. She was admitted to the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit for observation, and consent for possible intubation was obtained from her family. The patient was started on intravenous epinephrine 0.01 mL/kg (1:1000) and dexamethasone 0.5 mg/Kg every six hours, ceftriaxone, and clindamycin.

Initial laboratory results showed: white blood cells, 12.6 × 109 (4.5–13.5 × 109 cells/L); red blood cells, 3.57 × 1012 (4–5.4 × 1012 cells/L); hemoglobin, 9.8 g/dL (12–15 g/dL); platelets, 361 × 103/μL (150–450 × 103/μL); C-reactive protein, 8.67 mg/dL (0–3 mg/dL); erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 37 (1–20 mm/h); urea, 12.3 (2.5–7.1 mmol/L); and serum creatinine, 731 (53–115 Umol/L). Serum electrolytes were within normal range.

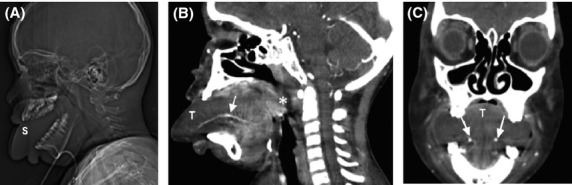

Further investigations included a chest X-ray and computed tomography (CT) scan of the neck and soft tissue (without contrast). The CT scan revealed a marked enlargement of the tongue, with obliteration of the oral cavity (Fig.2A, B and C). This enlargement was associated with mucosal thickening of the oropharyngeal mucosa and pharyngeal space, causing marked narrowing of the oropharyngeal airway.

Figure 2.

Computed tomography scan of the neck and soft tissue without contrast revealed marked enlargement of the tongue (T), with complete filling of the oral cavity. It was associated with mucosal thickening of the oropharyngeal mucosa and pharyngeal space, causing marked narrowing of the oropharyngeal airway (A, B, and C).

Total parenteral feeding was administered for 2 days due to the presence of edema, which precluded placement of a nasogastric tube; in addition, her tongue was covered with gauze soaked in normal saline. Her condition improved over the next 48 h, and her tongue returned to its anatomical position. By the seventh day, the patient's symptoms had resolved completely (Fig.1C). She was discharged on oral amlodipine, amiodarone, and furosemide 10 days following admission.

Discussion

Angioedema is a nonpitting, nonpruritic edema caused by extravasation of fluid into the deep layers of the dermis and subcutaneous tissue. Angioedema is classified according to its etiology into two types: mast cell (IgE) mediated angioedema, which is more common in pediatrics, involves the release of vasoactive substances from mast cells that can be triggered by infection (most common), drugs, food, insect bite, and physical factors 6. Another mechanism is the accumulation of bradykinin, a potent vasodilator. This accumulation occurs either due inhibition of its degradation or a genetic deficiency of C1 inhibitor.

Our patient had fever and cough prior to her presentation with angioedema suggesting that infection is a possible trigger factor for her angioedema development. Both viral and bacterial infections are well-known trigger factors for the development of urticaria and angioedema 7.

The exact mechanism of ACEi-induced angioedema remains unknown. It is suggested that bradykinin, a potent vasodilator, is degraded by angiotensin-converting enzyme into an inactive peptide. It is postulated that ACEis inhibit angiotensin-converting enzyme, which converts bradykinin to an inactive peptide, leading to accumulation of bradykinin in the blood stream 8,9.

The incidence of ACEi-induced angioedema in adults varies in clinical cohorts from 0.68 to 11% 1,10. ACEi-induced angioedema is less common in children, and only five cases have been reported in the literature 2–5. Table1 summarizes the clinical and demographic data of these cases. Hom et al. reported two cases, but one of them was 18 years old and therefore we did not consider him a child 5.

Table 1.

Summary of the demographic and clinical data of pediatric cases with angiotensin-converting enzyme-induced angioedema

| Reference and year of publication | Age | Race | Gender | Past medical history | Site of swelling | Respiratory distress | ACEi | Duration of ACEi |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Assadi et al., 1999) 2 | 7 years | Hispanic | Female | Lupus nephritis | Face Lips Oropharynx Neck Tongue | Yes | Enalapril | 4 years |

| (Assadi et al., 1999) 2 | 14 years | African-American | Male | Lupus Nephritis | Lips Tongue Neck | No | Enalapril | 3 years |

| (Quintana and Attia, 2001) 3 | 14 years | African-American | Male | SLE HTN Polyneuritis | Submandibular Neck | Yes | Enalapril | 3 years |

| (El Koraichi et al., 2011) 4 | 2 years | Female | ESRD secondary to HUS on dialysis | Isolated lingual swelling | No | Enalapril | 2 days | |

| (Hom et al., 2012) 5 | 1 year 11 month | African-American | Male | Mitral valve insufficiency after septal defect repair HTN | Face Oropharynx Neck | Yes | Enalapril | 1 year 7 month |

ACEI, Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitor; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; HTN, hypertension; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; HUS, hemolytic uremic syndrome.

It was reported that black race, female gender, a history of drug rash, smoking, age > 65 years, allergy, recent ACEi use (first week of treatment), obesity, upper respiratory tract surgery or trauma, sleep apnea, and renal transplantation are risk factors for ACEi-induced angioedema 11. The patient in our case presented some risk factors for angioedema, namely black race and female gender. In addition to the fact that she was on captopril, our patient's characteristics were consistent with angioedema, which typically affects the orofacial and/ or perioral area and/ or upper airways 1.

The issue of adverse reactions of ACEi in children is clinically relevant because these drugs were recently approved for use in children and young adults 11. Because angioedema is a drug class effect 6, physicians, especially those working at emergency departments, should identify and consider ACEis in their differential diagnosis and take the necessary steps to treat this potentially life-threatening condition. Further considerations should include advising the patient to avoid all ACEis 12.

Our patient had severe angioedema owing to the severity and degree of compromise of her airway. Symptoms such as drooling, stridor, hoarseness of the voice, or aphonia warrant immediate action and securing of the airway 1. While the patient in our case did not develop any of these symptoms, measures were taken to prepare for these issues, including transferring the patient to the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit and obtaining consent for possible intubation from her family.

Our patient received epinephrine and corticosteroids. However, these medications have no role in the management of ACEi-induced angioedema as the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms are not related to mast-cell-medicated reactions (IgE).

The most important recommendation in the management of patients with ACEi-induced angioedema, besides avoiding ACEis, is to modify the patient's treatment 11. Drugs from other pharmacologic categories should be recommended. In our patient, a calcium channel blocker was prescribed. Although an angiotensin-receptor blocker (ARB) may have been suitable in our patient, cases of angioedema following ARB administration have been reported in patients who had previously developed angioedema due to ACEis 11.

Icatibant is a bradykinin receptor and has been shown to be effective in the treatment of ACEi-induced angioedema in case series study 13. More studies are needed to recommend the use of Icatibant for treatment of ACEi-induced angioedema. A recent case report noted that C1 inhibitor concentrate was effective in the treatment of ACEi-induced angioedema. A case report from Germany showed C1 esterase inhibitor concentrate treatment was successful for treatment of ACEi-induced angioedema 14.

Conclusion

ACEi-induced angioedema is a fatal complication and early diagnosis is essential to give appropriate therapeutic measurements. The management relies on stopping ACEi and close monitoring. The possible pathophysiological mechanism is related to the accumulation of bradykinin which is a potent vasodilator. Other possible pharmacological management includes: Icatibant, a bradykinin receptor antagonist and C1 esterase inhibitor. However, more studies are needed before recommending these therapies for ACEi-induced angioedema.

Acknowledgments

Our special thanks to Rayan Ahyad, MBBS who drew the diagram. The authors appreciate his kind help and effort.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- Rasmussen ER, Mey K. Bygum A. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced angioedema – a dangerous new epidemic. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2014;94:260–264. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assadi FK, Wang HE, Lawless S, McKay CP, Hopp L. Fattori D. Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor-induced angioedema: a report of two cases. Pediatr. Nephrol. 1999;13:917–919. doi: 10.1007/s004670050727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintana EC. Attia MW. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor angioedema in a pediatric patient: a case report and discussion. Pediatr. Emerg. Care. 2001;17:438–440. doi: 10.1097/00006565-200112000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Koraichi A, Tadili J, Benjelloun MY, Benafitou R, El Kharraz H, Lahlou J, et al. Enapranil-induced angioedema in a 2-year-old infant: case report. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2011;11:382–384. doi: 10.1007/s12012-011-9130-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hom KA, Hirsch R. Elluru RG. Antihypertensive drug-induced angioedema causing upper airway obstruction in children. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2012;76:14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2011.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sackesen C, Sekerel BE, Orhan F, Kocabas CN, Tuncer A. Adalioglu G. The etiology of different forms of urticaria in childhood. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2004;21:102–108. doi: 10.1111/j.0736-8046.2004.21202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wedi B, Raap U, Wieczorek D. Kapp A. Urticaria and infections. Allergy Asthma Clin. Immunol. 2009;5:10. doi: 10.1186/1710-1492-5-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tai S, Mascaro M. Goldstein NA. Angioedema: a review of 367 episodes presenting to three tertiary care hospitals. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2010;119:836–841. doi: 10.1177/000348941011901208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney EJ. Devaiah AK. Angioedema and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors: are demographics a risk? Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2008;139:105–108. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2008.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zingale LC, Beltrami L, Zanichelli A, Maggioni L, Pappalardo E, Cicardi B, et al. Angioedema without urticaria: a large clinical survey. CMAJ. 2006;175:1065–1070. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.060535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Borges M. Gonzalez-Aveledo LA. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angioedema. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 2010;2:195–198. doi: 10.4168/aair.2010.2.3.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamurthy A, Naguwa SM. Gershwin ME. Pediatric angioedema. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2008;34:250–259. doi: 10.1007/s12016-007-8037-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bas M, Greve J, Stelter K, Bier H, Stark T, Hoffmann TK, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of icatibant in angioedema induced by angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors: a case series. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2010;56:278–282. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinbach O, Schweder R. Freitag B. C1-esterase inhibitor in ACE inhibitor-induced severe angioedema of the tongue. Anaesthesiol. Reanim. 2001;26:133–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]