Key Clinical Message

Here, we present a 53-year-old man with angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma accompanied by skin lesions (vesicles, papulovesicles, and miliary papules symmetrically distributed on extremities and trunk, with more distal lesions increasing in severity). Routine blood tests showed a white blood cell count of 58.97 × 109/L (Neutrophils% 91.64%).

Keywords: Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma, neutrophilic leukemoid reaction, papulovesicular, skin lesions, vesicles

Introduction

Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL) is categorized as a peripheral T-cell lymphoma and is clinically characterized by a sudden onset of constitutional symptoms, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, immune disease (hyperactivity of the immune system and immunodeficiency) and pleural effusion, ascites, and edema 1–3. Up to approximate half of patients have skin lesions but vesicles directly caused by AITL are rare 1,3–5. Elevated white blood cells (usually eosinophilia) are also often observed in laboratory investigations but to our knowledge, neutrophilic leukemoid reaction caused by AITL was not reported, yet 1–3,6,7.

Here, we present an AITL case presenting with rare skin lesions (including vesicles, papulovesicles, and miliary papules) symmetrically distributed on the extremities and trunk, with more distal lesions increasing in severity and neutrophilic leukemoid reaction.

Case Report

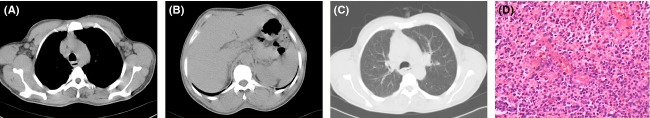

A 53-year-old Asian man was referred to our hospital for evaluation of lymphadenopathy and skin lesions. The patient's symptom history was detailed as follows: a dry cough for 3 months, lymphadenopathy for 1 month, skin lesions (started from the extremities) accompanied by pruritus for 3 weeks, dyspnea, and a mild fever for 1 week. At the time of admittance to our hospital, the patient endured severe pain of vesicles on hands and feet. Upon examination, the skin lesions were symmetrically distributed, with more distal lesions increasing in severity. Some large vesicles containing dark reddish exudate were distributed on both fingers and feet (Fig.1A and B). Some vesicles (large and small) and papulovesicles containing clear transparent exudate were distributed on the extremities (Fig.1A and C). Miliary papules were distributed on the upper chest and lower abdomen. Few lesions were found in the face while skin lesions were not found in the palms, soles, genitalia, scalp, around the mouth, or oral mucosa. There were palpable superficial lymph nodes in the neck, axillary fossae, and inguinas. The temperature of the skin was between 37.0 and 38.5°C during his hospitalization. The routine blood test showed a white blood cell count of 44.43 × 109/L, red blood cell count of 5.02 × 1012/L, and platelet count of 214 × 109/L. The cytological study of bone marrow showed hypergranulopoiesis. A computed tomography scan of the chest revealed lymphadenopathy in the mediastinum and axillary fossae (Fig.2A–C). Immunochemistry of biopsy from cervical lymphadenopathy showed CD3 was diffuse strong positive, CD20 and CD8 was scattered positive, CD21 and Bcl-2 were focally positive, and Ki67 positive cells ratio was higher than 80%. Based on the cytological study of bone marrow, peripheral blood, immunochemistry and hematoxylin & eosin staining of lymphadenopathy (Fig.2D), the pathologic diagnosis was AITL.

Figure 1.

Skin lesions.

Figure 2.

Computed tomography (A–C) and hematoxylin & eosin staining of lymphadenopathy (D). Diffuse infiltration of immunoblasts, abnormal lymphoid cells, clear/pale cells, and proliferation of high endothelial venules are observed in hematoxylin & eosin staining of lymphadenopathy.

Both morphine and tramadol were used to control pain. After 4 days of intravenous latamoxef sodium and isepamicin treatment, the routine blood test showed a white blood cell count of 58.97 × 109/L (neutrophils% 91.64%, lymphocytes% 5.24%, monocytes% 2.44%, and eosinophils% 0.42%), red blood cell count of 4.50 × 1012/L, and platelet count of 177 × 109/L. Manifestations progressively aggravated. Then chemotherapy consisting of cyclophosphamide, epirubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP-like therapy) was administered. After chemotherapy, there was abatement of clinical manifestations. The number of skin lesions increased during his 9 days of hospitalization. Some vesicles were blisters in the beginning, without erythematous or hemorrhagic base. Some papules on extremities slowly became papulovesicles and it usually took 1 week. None of papules on the trunk became papulovesicles or vesicles. The patient abandoned further treatment.

Discussion

AITL is a rare malignancy accounting for about 2% of all non-Hodgkin lymphoma and a highly aggressive neoplasm of the elderly 1–3,8. The median patients’ age is approximate 65 years 1–3,8,9. It generally presents with lymphadenopathy and is almost always accompanied by concomitant symptoms, including B symptoms, skin lesions, splenomegaly, hepatomegaly, effusion/edema/ascites, anemia, thrombocytopenia, elevated LDH, hypergammaglobulinemia and so on (Table1).

Table 1.

Clinical manifestations of AITL (numbers are presented as % except Patient number and Age)

| Authors | Federico 1 | Tokunaga 2 | Mourad 3 | Lachenal 9 | Siegert 4 | Aozasa 25 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient number | 243 | 207 | 157 | 77 | 62 | 44 |

| Age, years | ||||||

| Mean | 65 | 67 | 62 | 64.5 | 64 | 64 |

| Range | 20–86 | 34–91 | 20–89 | 30–91 | 21–87 | 25–84 |

| Male sex | 56 | 64 | 56 | 58 | 55 | |

| Lymphadenopathy | ||||||

| Generalized | 76 | 90 | 84 | |||

| Localized | 24 | 9 | 16 | |||

| Skin rash | 21 | 44 | 45 | 49 | 27 | |

| B symptoms | 69 | 60 | 72 | 77 | 68 | |

| Splenomegaly | 35 | 51 | 39 | |||

| Hepatomegaly | 26 | 26 | 52 | |||

| Effusion/edema/ascites | 14 | 26 | 25 | >38 | ||

| Bone marrow involvement | 28 | 29 | 47 | |||

| Extranodal sites, >1 | 27 | 23 | 46 | |||

| Anemia | 33 | 61 | 65 | 51 | 57 | 20 |

| Platelet count <150 × 109/L | 25 | 34 | 20 | 20 | ||

| Elevated LDH | 60 | 75 | 66 | 71 | 70 | |

| Elevated C-reactive protein | 35 | 46 | 67 | |||

| Hypergammaglobulinemia | 30 | 50 | 51 | 51 | 64 | |

| Positive Coombs test | 13 | 46 | 33 | 58 | 32 | |

LDH, Lactate dehydrogenase.

Nearly half of AITL patients have skin lesions 1,3–5,8. Skin lesions can precede, follow or be concurrent to lymphadenopathy 5,10,11. AITL skin lesions do not have characteristics to enable it to be distinguished from other skin eruptions, especially from drug eruptions. Therefore, misdiagnosis is not rare 5,12–14. Since AITL is almost always accompanied by concomitant symptoms (Table1), to be familiar with the common clinical characteristics and types of skin lesions is greatly helpful to avoid misdiagnosis.

Skin lesions in AITL usually accompany pruritus 1–5,8. Typical lesions are usually a generalized morbilliform or maculopapular eruptions on the trunk mimicking toxic erythema 2,4,5,8. In the literature, uncommon skin lesions of AITL are mostly described in case reports or review articles (Table2). It is not rare that the patient has a generalized pleomorphic rash composed of several types of rashes, such as macula, papules, maculopapules, nodules, erythroderma, urticaria, petechiae, purpura and so on. Necrotic purpura, polyarthritis, gingival ulceration, erythematous plaques (sometimes annular), toxic epidermal necrolysis, and hemorragic/necrotic nodules are also reported. Two cases of vesicles (one is pruritic papulovesicular (prurigo-like) lesion and the other is a pale erythematous eruption and violaceous plaques with bullae containing pale yellow exude.) were reported but they are apparently different from our case 5,15.

Table 2.

Uncommon skin lesions of AITL

| Authors | Age/Gender | Skin lesions | Duration of skin lesions before/after onset of lymphadenopathy | Prognosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wechsler 29 | 53/F | Erythematous macules; petechiae; purpura | 1 month after | Died (23 month) |

| Matloff 30 | 77/M | Macules; petechiae; purpura | 1 year before | Alive (4 month) |

| Seehafer 10 | 74/M | Petechiae | Concurrent | Died (3 month) |

| Seehafer 10 | 61/M | Erythroderma and purpura | Concurrent | Alive (48 month) |

| Seehafer 10 | 57/M | Petechiae | 10 month before | Alive (48 month) |

| Schmuth 31 | 73/F | Macules; petechiae; purpura | 4 week before | Alive (4 month) |

| Martel 15 | Necrotic purpura, maculopapules and urticaria | Died (26 day) | ||

| Martel 15 | Pruritic papulovesicular (prurigo-like) lesion | Alive (96 month) | ||

| Hashefi 32 | Maculopapules, petechiae | 3 month before | Died (23 month) | |

| Suarez-Vilela 33 | 67/F | Sarcoidosis | 1 month before | |

| Huang 34 | 62//M | Erythroderma; plaques; nodules | 3 year after | Died (3 year) |

| Jones 35 | 67/M | Erythroderma, toxic epidermal necrolysis | Concurrent | Died (5 month) |

| Tsochatzis 36 | 50/M | Polyarthritis, subcutaneous nodules | Concurrent | Died (2 month) |

| Jayaraman 11 | 61/M | Macules, papules, plaques, and nodules | Concurrent | Alive (5 year) |

| Ortonne 37 | 63/F | Nodules, gingival ulceration | ||

| Ortonne 37 | 54/M | Maculopapules, hemorragic/necrotic nodules | ||

| Nassar 5 | M/47 | Erythematous eruption; violaceous plaques with bullae containing pale yellow exude | 3 month before | Alive (4 month) |

| Smithberger 38 | 79/F | Cutaneous tumors and ulcerated nodules | No lymphadenopathy | |

| Ponciano 39 | 36/M | Erythematous plaques, sometimes annular | 5 year before | Alive (2 year) |

Vesicles caused by virus infection (such as HSV, VZV) in AITL patients were sporadically reported 12–14,16,17. Five AITL patients with VZV infection were reported in the literature and are summarized in Table3 12–14,16,17. The skin lesions of varicella appear on the trunk and face, and rapidly spread centrifugally to involve other areas of the body. Manifestations consist of maculopapules, vesicles, and scabs in varying stages of evolution. Skin rashes become papules within 12 h then become vesicles within 2 days. Over a very short period of time they scab. This rapid progression from stage to stage characterizes the clinical syndrome of varicella and enables it to be distinguished from certain other vesicular eruptions 12,18,19. Each skin vesicle appears on an erythematous base and immunocompromised patients have more numerous lesions, often with a hemorrhagic base 18,19. Since lesions in this patient were not symptoms of herpes zoster because of distribution of lesions and were quite unlike varicella 12,14,16–19, lesions are more likely caused by AITL than VZV infection. Further laboratory investigations (assessing for the presence of Epstein–Barr virus infected B cells, VZV in the lesional tissue, pathological examination of the lesional tissue, serological test and so on) can confirm the diagnosis but regretfully, the patient abandoned them.

Table 3.

VZV infection in AITL patients

| Authors | Age/Gender | Skin lesions of AITL | Duration1 | Manifestations of VZV infection | Duration2 | Prognosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kaneko 14 | 49/F | Maculopapule | Concurrent | Disseminated herpes zoster | 13 month | Died (15 month) |

| Zelickson 16 | 73/F | Hyperkeratotic papules | 1 week after | Hemorrhagic vesicles and bullae | Concurrent | Alive (4 month) |

| Boni 17 | 81/M | Maculopapule | 2 month before | Unilateral necrotizing herpes zoster | 2.5 month | Died (16 month) |

| Kanzaki 13 | 67/M | No | Not applied | An pharyngeal wall ulcer3 | Concurrent | Alive (18 week) |

| Imafuku 12 | 67/M | Maculopapule | 40 day before | Varicella | 1 month | Alive |

Duration of skin lesions before/after onset of lymphadenopathy.

Duration of herpes zoster infection after onset of AITL.

Elevation of antibodies against HSV and VZV were observed in the patient but the ulcer was unlikely caused by VZV.

As mentioned before, hematological changes including anemia, lymphopenia, leukocytosis, neutrophilia, eosinophilia, and thrombocytopenia, are often observed on laboratory investigations but leukemoid reaction is rare. Several cases mimicking plasma cell leukemia and one case of eosinophilic leukemoid reaction were reported by computer-based searches in PUBMED 6,7,20. The routine blood test of this case showed a white blood cell count of 58.97 × 109/L (neutrophils% 91.64%, lymphocytes% 5.24%, monocytes% 2.44%, eosinophils% 0.42%). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of neutrophilic leukemoid reaction in AITL.

Treatments to AITL are similar to other noncutaneous peripheral T-cell lymphoma but results are often unsatisfactory. The majority of cases are treated with chemotherapy (CHOP, CHOEP, and CHOP followed by ICE, CHOP followed by IVE, dose-adjusted EPOCH and HyperCVAD are the first line chemotherapies), stem cell transplantation, radiotherapy, and molecular targeted therapy 3,8,21. Folate antagonists (methotrexate, pralatrexate), purine analogs (fludarabine, azathioprine), prednisone, cyclosporine A, lenalidomide/thalidomide, interferon, and denileukin diftitox are reported to be effective in treating AITL 1,8,22. Alemtuzumab and bortezomib are promising therapy options that have been explored recently and warrant 8,22.

Though about two thirds of patients can achieve a complete remission, only half survive longer than 2 years 3,8. International prognostic index (based on age, stage, serum LDH, ECOG/Zubrod performance status, and extranodal site) and prognostic index for peripheral T-cell lymphoma (based on age, performance status, serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels, and bone marrow involvement) are widely accepted and used 2. Skin rashes imply poor prognosis 4,23,24. Other factors, such as male sex, B symptoms, edema, ascites, mediastinal lymphadenopathy, anemia, thrombocytopenia, lymphocytopenia, elevated white blood cell, decreased hemoglobin, elevated IgA levels, lymph node eosinophilia, the presence of clear and convoluted cells, high microvessel density measured in the microenvironment, higher ratio of M2 macrophages, failure to achieve complete remission, and drug exposure are reported to correlate with poor prognosis 2,3,23–28. So far, due to limited data available, prognostic factors in AITL sometimes yield controversial results.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no competing interest.

References

- Federico M, Rudiger T, Bellei M, Nathwani BN, Luminari S, Coiffier B, et al. Clinicopathologic characteristics of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma: analysis of the international peripheral T-cell lymphoma project. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013;31:240–246. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.3647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokunaga T, Shimada K, Yamamoto K, Chihara D, Ichihashi T, Oshima R, et al. Retrospective analysis of prognostic factors for angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma: a multicenter cooperative study in Japan. Blood. 2012;119:2837–2843. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-08-374371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mourad N, Mounier N, Briere J, Raffoux E, Delmer A, Feller A, et al. Clinical, biologic, and pathologic features in 157 patients with angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma treated within the Groupe d'Etude des Lymphomes de l'Adulte (GELA) trials. Blood. 2008;111:4463–4470. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-105759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegert W, Nerl C, Agthe A, Engelhard M, Brittinger G, Tiemann M, et al. Angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy (AILD)-type T-cell lymphoma: prognostic impact of clinical observations and laboratory findings at presentation. The Kiel Lymphoma Study Group. Ann. Oncol. 1995;6:659–664. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.annonc.a059281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nassar D, Gabillot-Carre M, Ortonne N, Belhadj K, Allanore L, Roujeau JC, et al. Atypical linear IgA dermatosis revealing angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. Arch. Dermatol. 2009;145:342–343. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2008.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahsanuddin AN, Brynes RK. Li S. Peripheral blood polyclonal plasmacytosis mimicking plasma cell leukemia in patients with angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma: report of 3 cases and review of the literature. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2011;4:416–420. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardais J, Fanello S, Joubaud F. Simard C. [Leukemoid eosinophilic reaction in angioimmunoblastic adenopathy] Rev. Med. Interne. 1984;5:309–314. doi: 10.1016/s0248-8663(84)80007-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iannitto E, Ferreri AJ, Minardi V, Tripodo C. Kreipe HH. Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2008;68:264–271. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2008.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachenal F, Berger F, Ghesquieres H, Biron P, Hot A, Callet-Bauchu E, et al. Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma: clinical and laboratory features at diagnosis in 77 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2007;86:282–292. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e3181573059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seehafer JR, Goldberg NC, Dicken CH. Su WP. Cutaneous manifestations of angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy. Arch. Dermatol. 1980;116:41–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayaraman AG, Cassarino D, Advani R, Kim YH, Tsai E. Kohler S. Cutaneous involvement by angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma: a unique histologic presentation, mimicking an infectious etiology. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2006;33(Suppl. 2):6–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2006.00489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imafuku S, Yoshimura D, Moroi Y, Urabe K. Furue M. Systemic varicella zoster virus reinfection in a case of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. J. Dermatol. 2007;34:387–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2007.00294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanzaki Y, Eura M, Chikamatsu K, Yoshida M, Masuyama K, Nishimura H, et al. Angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy-like T-cell lymphoma. A case report and immunologic study. Auris Nasus Larynx. 1997;24:199–206. doi: 10.1016/S0385-8146(96)00021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko Y, Larson RA, Variakojis D, Haren JM. Rowley JD. Nonrandom chromosome abnormalities in angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy. Blood. 1982;60:877–887. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martel P, Laroche L, Courville P, Larroche C, Wechsler J, Lenormand B, et al. Cutaneous involvement in patients with angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy with dysproteinemia: a clinical, immunohistological, and molecular analysis. Arch. Dermatol. 2000;136:881–886. doi: 10.1001/archderm.136.7.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelickson BD, Tefferi A, Gertz MA, Banks PM. Pittelkow MR. Transient acantholytic dermatosis associated with lymphomatous angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy. Acta Derm. Venereol. 1989;69:445–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boni R, Dummer R, Dommann-Scherrer C, Dommann S, Zimmermann DR, Joller-Jemelka H, et al. Necrotizing herpes zoster mimicking relapse of vasculitis in angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy with dysproteinaemia. Br. J. Dermatol. 1995;133:978–982. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1995.tb06937.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaia AJ. Grose C. Varicella and herpes zoster. In: Gorbach LS, Bartlett GJ, Blacklow RN, editors; Infectious disease. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004. pp. 1195–1207. [Google Scholar]

- Whitley JR. Varicella-zoster virus. In: Mandell LG, Bennett EJ, Dolin R, editors. Principles and practice of infectious diseases. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2010. pp. 1963–1969. [Google Scholar]

- Klajman A, Yaretzky A, Schneider M, Holoshitz Y, Shneur A. Griffel B. Angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy with paraproteinemia: a T- and B-cell disorder. Cancer. 1981;48:2433–2437. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19811201)48:11<2433::aid-cncr2820481116>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunleavy K, Wilson WH. Jaffe ES. Angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphoma: pathobiological insights and clinical implications. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2007;14:348–353. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e328186ffbf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SJ, Yoon DH, Kang HJ, Kim JS, Park SK, Kim HJ, et al. Bortezomib in combination with CHOP as first-line treatment for patients with stage III/IV peripheral T-cell lymphomas: a multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Eur. J. Cancer. 2012;48:3223–3231. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegert W, Agthe A, Griesser H, Schwerdtfeger R, Brittinger G, Engelhard M, et al. Treatment of angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy (AILD)-type T-cell lymphoma using prednisone with or without the COPBLAM/IMVP-16 regimen. A multicenter study. Kiel Lymphoma Study Group. Ann. Intern. Med. 1992;117:364–370. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-117-5-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archimbaud E, Coiffier B, Bryon PA, Vasselon C, Brizard CP. Viala JJ. Prognostic factors in angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy. Cancer. 1987;59:208–212. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19870115)59:2<208::aid-cncr2820590205>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aozasa K, Ohsawa M, Fujita MQ, Kanayama Y, Tominaga N, Yonezawa T, et al. Angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy. Review of 44 patients with emphasis on prognostic behavior. Cancer. 1989;63:1625–1629. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19890415)63:8<1625::aid-cncr2820630832>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ch'ang HJ, Su IJ, Chen CL, Chiang IP, Chen YC, Wang CH, et al. Angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy with dysproteinemia–lack of a prognostic value of clear cell morphology. Oncology. 1997;54:193–198. doi: 10.1159/000227687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao S, Zhang L, Zhang M, Yao G, Zhang X, Zhao W, et al. Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma: the effect of initial treatment and microvascular density in 31 patients. Med. Oncol. 2012;29:2311–2316. doi: 10.1007/s12032-011-0094-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niino D, Komohara Y, Murayama T, Aoki R, Kimura Y, Hashikawa K, et al. Ratio of M2 macrophage expression is closely associated with poor prognosis for Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL) Pathol. Int. 2010;60:278–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2010.02514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler HL. Stavrides A. Immunoblastic lymphadenopathy with purpura and cryoglobulinemia. Arch. Dermatol. 1977;113:636–641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matloff RB. Neiman RS. Angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy. A generalized lymphoproliferative disorder with cutaneous manifestations. Arch. Dermatol. 1978;114:92–94. doi: 10.1001/archderm.114.1.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmuth M, Ramaker J, Trautmann C, Hummel M, Schmitt-Graff A, Stein H, et al. Cutaneous involvement in prelymphomatous angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1997;36:290–295. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(97)80401-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashefi M, McHugh TR, Smith GP, Elwing TJ, Burns RW. Walker SE. Seropositive rheumatoid arthritis with dermatomyositis sine myositis, angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy with dysproteinemia-type T cell lymphoma, and B cell lymphoma of the oropharynx. J. Rheumatol. 2000;27:1087–1090. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez-Vilela D. Izquierdo-Garcia FM. Angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy-like T-cell lymphoma: cutaneous clinical onset with prominent granulomatous reaction. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2003;27:699–700. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200305000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang CT. Chuang SS. Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma with cutaneous involvement: a case report with subtle histologic changes and clonal T-cell proliferation. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2004;128:e122–e124. doi: 10.5858/2004-128-e122-ATLWCI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones B, Vun Y, Sabah M. Egan CA. Toxic epidermal necrolysis secondary to angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. Australas. J. Dermatol. 2005;46:187–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.2005.00177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsochatzis E, Vassilopoulos D, Deutsch M, Filiotou A, Tasidou A. Archimandritis AJ. Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma-associated arthritis: case report and literature review. J. Clin. Rheumatol. 2005;11:326–328. doi: 10.1097/01.rhu.0000195105.20029.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortonne N, Dupuis J, Plonquet A, Martin N, Copie-Bergman C, Bagot M, et al. Characterization of CXCL13+ neoplastic t cells in cutaneous lesions of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL) Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2007;31:1068–1076. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31802df4ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smithberger ES, Rezania D, Chavan RN, Lien MH, Cualing HD. Messina JL. Primary cutaneous angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma histologically mimicking an inflammatory dermatosis. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:851–855. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponciano A, de Muret A, Machet L, Gyan E, Monegier du Sorbier C, Molinier-Frenkel V, et al. Epidermotropic secondary cutaneous involvement by relapsed angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma mimicking mycosis fungoides: a case report. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2012;39:1119–1124. doi: 10.1111/cup.12022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]