Abstract

Family legal status is a potentially important source of variation in the health of Mexican-origin children. However, a comprehensive understanding of its role has been elusive due to data limitations and inconsistent measurement procedures. Using restricted data from the 2011-2012 California Health Interview Survey, we investigate the implications of measurement strategies for estimating the share of children in undocumented families and inferences about how legal status affects children's health. The results show that inferences are sensitive to how this “fundamental cause” is operationalized under various combinatorial approaches used in previous studies. We recommend alternative procedures with greater capacity to reveal how the statuses of both parents affect children's well-being. The results suggest that the legal statuses of both parents matter, but the status of mothers is especially important for assessments of child health. The investigation concludes with a discussion of possible explanations for these findings.

Keywords: United States, Children, Health, Mexican-origin, Legal status, Immigrants, Undocumented, Measurement

The dramatic long-term growth in immigration to the United States has stimulated numerous studies of the health of immigrants and their children, especially those of Mexican origin. However, legal status remains an unmeasured source of heterogeneity in many studies of foreign-born Mexicans and their offspring. Over half of Mexican immigrants are undocumented and nearly two-thirds of Mexican-origin children have immigrant parents (Passel 2011; Gonzalez-Barrera and Lopez 2013). Thus, attention to legal status is necessary to fully understand how nativity and generation affect the health of this population.

The growth of the Mexican-origin population also underscores the need to understand how international migration and ethnicity intersect as determinants of disparities in children's health that emanate from “fundamental” disadvantages (Link and Phelan 1995; Phelan et al. 2010). National health policy objectives focus on reducing the impact of disadvantage among those who have “systematically experienced greater obstacles to health based on their racial or ethnic group” (www.healthypeople.gov/2020/). Such concerns apply to the Mexican-origin population. Although less than one in five of all Mexicans in the United States are unauthorized (18%), they disproportionately experience disadvantages that stem from the lack of authorization (Gonzalez-Barrera and Lopez 2013). This source of disadvantage is usually hidden from view in efforts to monitor trends and disparities in children's health.

In general, studies of children demarcate legal status as a family construct. This stems from children's dependence on the decisions, actions, and resources of parents who may have diverse migration experiences. This diversity raises measurement issues that have not been addressed systematically in the literature. Prior studies offer numerous strategies, but consensus on how to measure the legal status of families is not apparent. Using the 2011-12 California Health Interview Survey (CHIS), this investigation illuminates measurement strategies for describing family legal status by combining information on parents. This topic is important because numerous approaches can be identified in a literature that lacks both well-established principles for aggregating the statuses of individual family members and assessments of the implications of different principles for findings. We assess “combinatorial” measurement approaches by demonstrating their implications for inferences about the size and health of children in different legal status groups. After introducing legal status as a source of structural disadvantage and discussing its measurement, we show that some strategies obscure the vulnerabilities of Mexican-origin children and offer an alternative procedure to guide future research. It should be emphasized that our objective is to assess measurement strategies. This requires theoretical and conceptual grounding for insights into how legal status operates, but coverage of all factors that affect health is neither possible nor necessary given this aim.

Health, Legal Status and Structural Disadvantage

Health encompasses diseases, conditions and cognitive/non-cognitive capacities that contribute to well-being (NRC/IOM 2004: 33). This emphasis on well-being is one reason why global self-assessments are used to monitor population health (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services). Another reason is that such assessments predict mortality, medical care and lifestyle decisions (Idler and Benyami 1997; Jylhä 2009). Still, subjective assessments are complicated by cultural differences in ideas about what constitutes health, reference points for assessing health, and modes of expressing health status in relation to what is “normal” (Jylhä 2009).

Understanding the linkages between child health and legal status requires attention to fundamental social causes (Link & Phelan 1995; Phelan et al. 2010). Fundamental causes are structurally-rooted disadvantages that have adverse consequences for health and the treatment of disease. Structural disadvantages are reflected in endowments of various forms of capital, including income and wealth-related economic resources, social resources through connections with others, and knowledge acquired through formal education and experience. These resources operate through multiple pathways to affect exposure to risk and risk mitigation. The primacy of such causes is evident from studies demonstrating that social factors are as important as biomedical risk factors for health and health care (Stein et al. 2010).

This framework is useful for highlighting counterintuitive findings regarding nativity as a source of heterogeneity within the Mexican-origin population. Specifically, the “epidemiological paradox” points to better health among the foreign born than their native-born co-ethnics despite greater exposure to disadvantage among the former. Yet, narratives about nativity and generational status typically pay little attention to legal status, which refers to a set of hierarchical categories that are institutionalized through laws, procedures, and practices. Immigration laws that regulate admission/deportation and alienage laws that define the rights of non-citizens segment the foreign-born into: (1) naturalized citizens; (2) “lawful” permanent residents (green card); (3) temporary residents issued a non-immigrant visa for a specific purpose (e.g. to work); and (4) unauthorized residents whose presence is temporary or permanent, but who are deemed “unlawful” because they entered without inspection or have an expired non-immigrant visa (Romero 2009).

Legal status distinctions matter because they affect access to opportunities and public benefits. Naturalized citizens are positioned at the top of the hierarchy by a legal process that renders them indistinguishable from the native born. In the middle position, permanent residents enjoy essentially unrestricted access to economic and educational opportunities along with the right to public benefits after satisfying residency requirements. At the bottom, undocumented persons are marginalized by state policies that restrict their access to public programs and by labor markets that offer low wages to those with low human capital and lack of permission to work in the United States (Duncan et al. 2006; Hall et al. 2010). Undocumented residents also face a negative reception from native-born citizens who may view them as a threat.

Although legal status is a non-redundant form of structural disadvantage, the absence of information beyond citizenship in most widely-used national surveys has hampered progress in identifying health disparities. An exception is Ziol-Guest and Kalil's (2012) analysis of nationally representative samples of children in low-income families using the 1996-2008 panels of the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP). They found that children living with a non-permanent resident parent are less likely than those living with two U.S.-born parents to receive medical care and to be classified as having excellent/very good health. This association was generally robust in models with ethnicity, demographic covariates and insurance, but “Hispanics” were not disaggregated by ancestry so it is unclear whether the findings hold for specific Hispanic subgroups.

Health Care Access and Utilization as Pathways

As a fundamental cause, legal status may affect health through multiple pathways that reflect structural and institutional forces that regulate access to medical care (Aday and Andersen 1974; Andersen and Newman 2005). Although the potential pathways include social networks and environments (neighborhoods, schools, etc.) that families are exposed to, research in this area largely focuses on access to health care as a proximate manifestation of more distal forms of disadvantage (Castañeda et al. 2015; see Yoshikawa 2011). Access to health care reflects a market-based system predicated on the ability to pay, either directly or through a third-party insurer. The federal policy framework for assistance is designed to discourage reliance on the government. Its cornerstone is the distinction between qualified and non-qualified immigrants. Permanent residents are eligible for assistance as qualified immigrants five years after acquiring this status, but visa holders and the undocumented are ineligible. This applies to all federal means-tested programs that potentially influence health, such as the Children's Health Insurance Program and food stamps (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2012). Still, states may pass legislation to lift the five-year ban on public benefits for permanent residents.

The case could be made that attention to such institutional barriers is misplaced for Mexican-origin children given that most are eligible for public benefits as native-born citizens (96.5%, authors' calculations for 0-11 year-old Mexican children in the 2010-12 American Community Surveys). Indeed, Perez et al.'s (2009) comparison of several Latino subgroups with whites using the 1998-2006 National Health Interview Surveys (NHIS) directs attention away from nativity and citizenship towards ethnicity. Although some statistically significant differences are very small, Mexican-origin children are relatively more likely than white children to experience delays in care and less likely to see a physician, to receive well-child care, to have a usual source of care and to use emergency rooms. However, estimates are not shown for a combined nativity-citizenship measure or its intersection with ethnicity. This is understandable because their focus was solely on children's nativity and citizenship, and 92% of Mexican-origin children in their data were U.S. born. Regardless, the absence of detailed information on the legal status of children and parents remains a limitation of the NHIS.

Research on adults in the CHIS demonstrates the potential importance of legal status for children's health. Among native-born and foreign-born Mexican-origin adults, the 2003 survey shows that the likelihood of having health insurance, a usual source of care, and physician visits increased progressively as one moved up the status hierarchy (Ortega et al. 2007). Another analysis of adult Mexican immigrants in the 2007 CHIS shows that non-permanent residents and a combined category of permanent residents and naturalized citizens do not differ on delayed care, but the former are less likely to have a usual place of care and to see health care providers (Vargas Bustamante et al., 2012).

Measurement

The legal status of individuals can be determined with direct and indirect methods. Direct measurement based on specific survey questions about legal status is preferred. When specific questions are unavailable, indirect measurement is possible through imputation. Imputation algorithms employ information on known characteristics of respondents in the survey of interest and on the association between these known characteristics and documentation status from another source (Van Hook et al. 2015). The present research is concerned with strategies that assume family legal status can be directly observed and measured (in contrast, see Bean et al. 2011 for a latent class approach).

Three issues must be considered in determining how family legal status affects children's health. First is deciding whose status counts. At minimum, parents must be considered because of their primary responsibility for children's welfare. Second, family structure is a concern because non-resident parents may or may not provide resources to their children. Third, families are gendered. Women generally have greater responsibility for children than men in both single-parent and two-parent families (Bianchi 2011; Coltrane and Shih 2010; Anonymous 2006; Vargas 2014).

Most studies cannot respond to all of these challenges. Some surveys include information on a focal child and resident parents only (SIPP), while others include both resident and non-resident parents (CHIS). Regardless, analysts employ numerous decisions rules to combine the statuses of all available parents into a single measure to describe the family as a collectivity. This has resulted in combinatorial strategies with different assumptions about the primacy and equivalence of statuses.

Anchoring strategies classify children according to the lowest or the highest positioned parent (Ziol-Guest and Kalil 2012; Guendelman et al. 2005). Low status anchoring assigns children of mixed-status parents to the lowest position. Those with one undocumented parent and those with two undocumented parents are combined into “undocumented” families. Among the remainder, those with one or two non-citizen parents with a green card are classified as “permanent resident” families. Next, those with at least one naturalized citizen parent are combined into “naturalized” families. The top category is reserved for children with two native-born parents.

Under high status anchoring, children of mixed-status parents are classified based on the highest position. This reserves the bottom of the hierarchy for those with two undocumented parents. Children of one undocumented and one green card parent are combined with those who have two green card parents to form “permanent resident” families. Children with a naturalized citizen parent and either a permanent resident parent or an undocumented parent are combined with those who have two naturalized citizen parents to form “naturalized” families. “Native-born” families have either one or two U.S.-born parents.

Alternative approaches conflate adjacent categories or rely on a hybrid strategy. The former typically combines permanent residents and naturalized citizens or naturalized citizens and native-born citizens. Some investigators count children with at least one permanent resident parent or naturalized citizen parent as living in “documented” families (Ortega et al. 2009). Others use a hybrid approach that conflates naturalized and native-born citizenship before applying the low status anchor (Guendelman et al. 2005b; Guendelman et al. 2005a). Still another approach is necessary for users of public-use data that only identify native-born citizens, naturalized citizens, and non-citizens (thereby conflating permanent residents and non-permanent residents). These categories can be used with low status anchoring to illustrate a public-use hybrid measurement approach that emphasizes citizenship status.

Research Issues

Development of the literature on Mexican-origin children has been hindered by the absence of information on legal status in many health surveys and the lack of consensus on measurement strategies to describe family legal status when this information is available for parents. This study extends the literature by using the CHIS to examine whether inferences about the role of family legal status in Mexican-origin children's health are sensitive to the choice of measurement strategy. Our analyses demonstrate that measurement decisions affect estimates of the number of children in different family legal status categories and estimates of the association between family legal status and children's health. Consequently, we evaluate the assumptions of combinatorial strategies and offer a straightforward alternative for consideration in future studies.

Data and Methods

The analysis is based on the 2011-12 CHIS. The CHIS is conducted by Westat for UCLA's Center for Health Policy Research, the California Department of Public Health and the state Department of Health Care Services. This telephone survey employs a multi-stage sampling design with 44 counties/county groups as geographic strata for the random-digit dialing of households with landlines and cell phones. Administered in several languages (including Spanish), information is collected on representative samples of adults (age 18+), adolescents (11-17) and children (0-11). We focus on the latter sample, which consists of one randomly selected child per household. Questions were answered by the adult who was “most knowledgeable” (MKA) about the focal child's health, almost always a biological or adoptive parent (98%).

The analysis is limited to 2,895 Mexican-origin children ages 0-11 who were identified as having “Mexican,” “Mexican American” or “Chicano” ancestry. The weighted sample is representative of Mexican-origin children in California under the age of 12. Missing data are imputed by the CHIS using relational and model-based “hot-deck” procedures.

Dependent Variable: Child Health

The respondents were asked: “In general, would you say (child's) health is excellent, very good, good, fair or poor?” Consistent with prevailing practices, responses are dichotomized into excellent/very good (1) vs. good/fair/poor (0). For ease of presentation, we refer to parent-reported child health as “child health.”

Immigration and Legal Status

Legal status is determined for children, mothers and fathers. After asking for country of birth, the survey asked whether each foreign-born child and parent was a U.S. citizen. A follow-up probed whether each non-citizen was a “permanent resident with a green card.” Thus, native-born citizens, naturalized citizens, permanent residents and non-permanent residents are identified. The latter are referred to as “undocumented”---the status of the vast majority in this category, given that 93% of foreign-born U.S. residents without a green card are undocumented (Gonzalez-Barrera et al. 2013). This figure is undoubtedly higher for those born in Mexico. Prior research shows that questions on legal status are valid (Bachmeier et al. 2014).

Information on the status of both parents permits a comprehensive investigation of two-parent combinatorial measurement strategies. Some previous investigations emphasize parent-child dyads based on a single adult survey respondent and a single child in the household (Stevens et al. 2010). As revealed below, we do not replicate that strategy because the immigration status of children is essentially a constant and it is preferable to use information on both parents.

Covariates

The analysis controls for poverty and education as socioeconomic risk factors that are associated with health and legal status. Poverty is expressed as the ratio of household income to federal thresholds. It is dummy coded to contrast those below (≤.99) with those near (1.0-1.99), somewhat above (2.00-2.99) and well above the threshold (≥3.00). Education is based on the MKA. Those with a college degree, some college and a high school degree are contrasted separately with those without a high school degree (the reference).

Other covariates include language proficiency (MKA speaks English only/very well/well), single vs. two-parent family and the child's age. Access to health care is indicated by insurance coverage during the full year prior to the survey (vs. non-coverage). Health care utilization is indicated by whether the child visited a doctor at least once (vs. not at all) in the past year.

Caveats

Several methodological considerations are worth noting. First, restricted data from the CHIS provide a unique opportunity to assess different measurement strategies, but an overall response rate of less than 20% is low (California Health Interview Survey 2014). This is consistent with a historical decline in survey participation. Indeed, such rates are not atypical for telephone surveys and for comparable efforts such as the California Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey (California Health Interview Survey 2014; Pew Research Center 2012). Non-response bias is not associated with low response rates and analyses of earlier CHIS surveys indicate that this is not a major concern with these data (California Health Interview Survey 2011; Groves 2006; Groves and Peytcheva 2008; Massey and Tourangeau 2013).

A second consideration is the meaning of subjective health measures given ambiguities of language. For example, some suggest that the Spanish term “regular” is not necessarily equivalent to “fair” in English for questions on health. The empirical evidence for such claims using other datasets is mixed at best (Viruell-Fuentes et al. 2011). Also, the cut-point that we use does not rely on precise distinctions at the lower end of the scale.

Third, our objective is to highlight the implications of different ways of measuring legal status in light of other sources of structural disadvantage. Although the included covariates overlap with those emphasized in theories of fundamental causes and in analyses of health care access and utilization, we do not claim to have included an exhaustive set of predictors. Health surveys typically are limited in the range of predictors that can be included (e.g. Stevens et al. 2010). Clearly, further progress might be made if future studies are able to include additional characteristics of parents and families along with measures of home, school, neighborhood and policy-related environments (Yoshikawa and Kalil 2011).

Results

The analysis proceeds in several steps. After describing the legal status distributions of children, mothers and fathers as individuals, we demonstrate the consequences of various combinatorial strategies for estimating the distribution of children across family legal status groups. Next, we show the implications of these strategies for estimates of the percentage of children in excellent or very good health. This is followed by logistic regression models that address whether inferences about the relationship between family legal status and child health are sensitive to the measurement strategy used, including various combinatorial strategies and an alternative approach that considers the mother's and the father's legal statuses separately.

Describing Family Legal Status

Table 1 provides frequencies for the legal status of children and parents. California is the home of 2.8 million Mexican-origin children under age 12, the overwhelming majority of whom are U.S. born (97%). Only 1% of children are naturalized citizens or permanent residents and 2% are undocumented. In contrast, half (53%) have a foreign-born mother, with nearly equal shares unauthorized (25%) and authorized (28% naturalized or permanent residents). As for fathers, 60% are foreign born (30% unauthorized and 30% authorized). These figures indicate that family legal status must be based on parents because children are homogeneous.

Table 1. Legal Status: Mexican-Origin Children Age 0-11 in California (2011-12).

| Percent | NWeighted | NUnweighted | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child | |||

| Native Born (U.S.) | 96.7 | 2,732,531 | 2,768 |

| Naturalized | .6 | 16,450 | 36 |

| Permanent Resident | .6 | 16,430 | 31 |

| Undocumented | 2.1 | 59,745 | 60 |

| Total | 100.0 | 2,825,176 | 2,895 |

| Mother | |||

| Native Born (U.S.) | 46.9 | 1,324,559 | 1,022 |

| Naturalized Citizen | 12.3 | 347,778 | 434 |

| Permanent Resident | 15.6 | 440,891 | 619 |

| Undocumented | 25.2 | 711,948 | 820 |

| Total | 100.0 | 2,825,176 | 2,895 |

| Father | |||

| Native Born (U.S.) | 39.7 | 1,122,269 | 948 |

| Naturalized Citizen | 15.1 | 425,507 | 518 |

| Permanent Resident | 14.8 | 418,302 | 574 |

| Undocumented | 30.4 | 859,097 | 859 |

| Total | 100.0 | 2,825,176 | 2,895 |

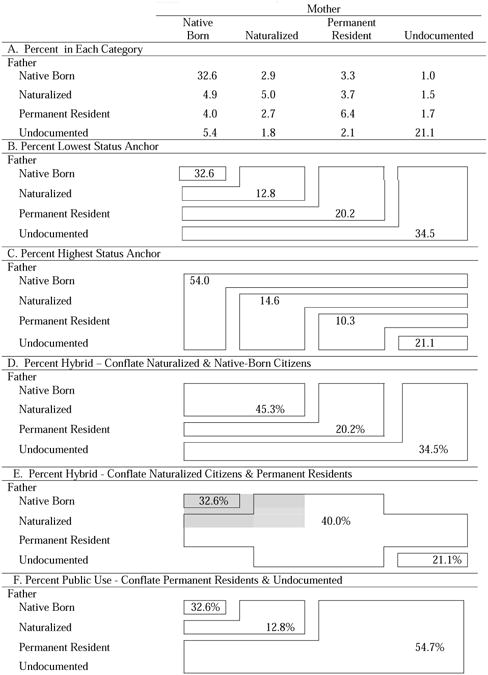

Table 2 shows the intersection of parents' legal statuses under different measurement schemes. The main diagonal in Panel A reveals that a majority of mothers and fathers have the same status, with the largest groups having two native-born parents (33%) or two undocumented parents (21%). Summing the first row and first column reveals that the majority of children have at least one U.S.-born parent (54%). Summing the bottom row and last column reveals that 35% have at least one undocumented parent---nearly one million in total (977,511 = 2,825,176*.346)

Table 2. Percentage of Mexican-Origin Children in California by Family Status Strategy.

|

Note: All values are unadjusted for covariates.

The remaining panels show shares for the combinatorial strategies. Panels B and C indicate that anchoring approaches have major implications for inferences. Under low-status anchoring, 33% are in the top category with two U.S.-born parents, 20% in the next-to-lowest category with a permanent resident parent and 35% in the lowest category with at least one undocumented parent. The high status anchor places 54% in the top category with at least one U.S.-born parent, 10% in the category in which the highest-status parent is a permanent resident and 21% below that with two undocumented parents. Such differences are substantial. The low-status anchor places a million children and the high-status anchor places 600,000 children in the most vulnerable group (596,112=2,825,176*.211).

Hybrid approaches that conflate categories are next. Panel D conflates native-born citizens and naturalized citizens with a low-status anchor. This puts 45% of children in the most advantaged category, a value that lies at the midpoint of the values for high (54%) and low-status (33%) anchoring categories. Panel E conflates naturalized citizens and permanent residents in a manner that is consistent with prior research, but the shaded area and omitted cells reflect uncertainty due to imprecise language in the original source (Ortega et al. 2009). This leaves 40% of children in the middle category, a value twice that in Panel D (20%).

The public-use file with a low-status anchor places 55% of children in the bottom category because permanent residents and the undocumented cannot be distinguished. This is the largest value in the table. Because collapsing these categories for this population is questionable given the prevalence of undocumented parents, the value of public-use data for examining health outcomes that may be associated with parental legal status is limited.

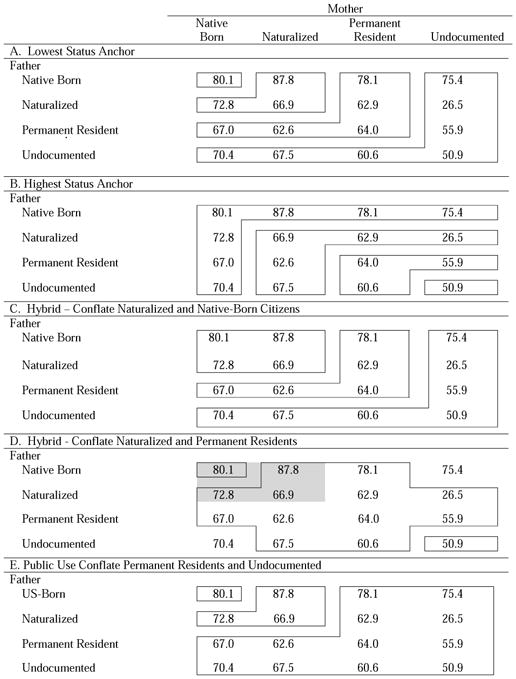

Family Legal Status and Child Health

Table 3 provides point estimates for the percentage of children in excellent or very good health for the 16 combined mother-father statuses to show the impact of combinatorial strategies. Although the point estimates are based on different numbers of observations, the results suggest that differences in reported health may be masked by aggregating categories (interval estimates are available on request). In Panel A, cell percentages range from 51% to 75% for the undocumented group if one anomalous value is disregarded. In particular, combining those with two undocumented parents (51%) and those with one undocumented parent (56% - 75%) elevates the share of “healthy” children in the most disadvantaged category.

Table 3. Percentage of Mexican-Origin Children in Excellent or Very Good Health by Family Status.

|

Note: All values are unadjusted for covariates.

Under high status anchoring, only children with two undocumented parents occupy the bottom position (Panel B). This strategy amplifies their low likelihood (51%) of being in excellent/very good health. The other groups include parents with the same or different legal statuses. Children in a “native-born family” include those with two U.S.-born parents or with one U.S.-born parent and one naturalized, permanent resident, or undocumented parent. The percentage of children in excellent/very good health among these mixed-status families ranges from 67% to 88% in the top row and first column.

Panel C indicates that conflating naturalized and native-born citizens conceals the fact that only 67% of children with two naturalized parents are healthy, compared to 80% of children with two native-born parents. Combining naturalized citizens and permanent residents in Panel D and permanent residents and the undocumented in Panel E also reveals potential for “grouping error.”

Table 4 presents estimates of child health using each combinatorial strategy. Inferences about the existence of an association with legal status are not sensitive to these procedures; each is significant at p<.01 or p<.001. Moreover, differences across strategies are minor at the extremes with 78-80% of those in the top category and 51-55% of those in the bottom category healthy (except for the public-use version at 60%). In contrast, estimates for intermediate categories are more sensitive to the choice of anchoring strategy. For example, 74% are healthy among those whose lowest status parent is naturalized and 61% are healthy among those whose highest status parent is naturalized.

Table 4. Percentage of Children in Excellent/Very Good Health by Status.

| Total % | Health Excellent Very Good % | |

|---|---|---|

| A. Lowest Status Anchor | ||

|

| ||

| Both parents native born (U.S.) | 32.6 | 80.1 |

| Lowest FB parent naturalized | 12.8 | 73.9 |

| Lowest FB parent permanent resident | 20.2 | 66.5 |

| Lowest FB parent undocumented | 34.5 | 55.3 |

|

|

||

| F Rao-Scott | 16.1 | |

| Significance (p<) | .01 | |

|

| ||

| B. Highest Status Anchor | ||

|

| ||

| Highest parent native born (U.S.) | 54.0 | 77.7 |

| Highest parent naturalized | 14.6 | 61.1 |

| Highest parent has permanent resident | 10.3 | 62.0 |

| Both parents undocumented | 21.1 | 50.9 |

|

|

||

| FRao-Scott | 21.05 | |

| Significance (p<) | .001 | |

|

| ||

| C. Hybrid Conflate Naturalization & Nativity | ||

|

| ||

| Both parents naturalized or native born (U.S.) | 45.3 | 78.4 |

| Lowest parent Permanent resident | 20.2 | 66.5 |

| Lowest parent undocumented | 34.5 | 55.3 |

|

|

||

| F Rao-Scott | 26.00 | |

| Significance (p<) | .001 | |

|

| ||

| D. Hybrid Conflate Naturalization & Permanent | ||

|

| ||

| Both parents native born (U.S.) | 32.6 | 80.1 |

| 1+ parent naturalized or permanent resident | 40.0 | 66.7 |

| Both parents undocumented | 21.1 | 50.9 |

| Missing | 6.4 | 71.2 |

|

|

||

| F Rao-Scott | 14.59 | |

| Significance (p<) | .001 | |

|

| ||

| E. Public Use Conflate Permanent & Undocumented | ||

|

| ||

| Both Parents native born (U.S.) | 32.6 | 80.1 |

| At least one parent naturalized | 12.8 | 73.9 |

| Both parents non-citizen | 54.7 | 59.5 |

|

|

||

| F Rao-Scott | 18.55 | |

| Significance (p<) | .001 | |

Note: The “missing” category in Panel D corresponds to cells 4 and 13 in Table 3. All percentages are unadjusted for covariates

Multivariate Models of Child Health

Table 5 shows results for bivariate (Model 1) and multivariate (Model 2) logistic regression models, with the undocumented serving as the reference category. Several similarities in findings are evident. First, Wald χ2's indicate that the overall bivariate relationship between family legal status and child health is highly significant, regardless of approach. Second, health increases with status across all measures, but bivariate odds ratios for contrasts between the top and bottom categories range from 3.0 to 4.0. Third, legal status is inconsequential in models with covariates.

Table 5. Odds Ratios from Logistic Regressions: Child Health on Combinatorial Strategies.

| Bivariate | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | ||

| A. Low Status Anchor | |||

|

| |||

| Both Native Born | 3.25*** | 1.23 | |

| Naturalized | 2.28*** | 1.21 | |

| Permanent Resident | 1.60** | 1.10 | |

| Undocumented | ----- | ----- | |

| Wald χ2 | 54.36*** | 1.01 | |

|

| |||

| B. High Status Anchor | |||

|

| |||

| Native Born (One/Two Parents) | 3.36*** | 1.27 | |

| Naturalized | 1.57* | 1.01 | |

| Permanent Resident | 1.52 | 1.30 | |

| Undocumented | ----- | ----- | |

| Wald χ2 | 61.92*** | 2.49 | |

|

| |||

| C. Hybrid Conflate Naturalized & Native | |||

|

| |||

| Both Native Born or Naturalized | 2.92*** | 1.22 | |

| Low Permanent Resident | 1.60** | 1.10 | |

| Low Undocumented | ----- | ----- | |

| Wald χ2 | 55.08*** | 1.01 | |

|

| |||

| D. Hybrid Conflate Naturalized & Permanent | |||

|

| |||

| Both Native Born | 3.89*** | 1.30 | |

| Naturalized & Permanent | 1.93*** | 1.13 | |

| Both Undocumented | ----- | ----- | |

| Wald χ2 | 44.05*** 1.55 | ||

|

| |||

| E. Public Use Conflate Permanent & Undocumented | |||

|

| |||

| Both Native Born | 2.75*** | 1.17 | |

| Naturalized (Lowest) | 1.93*** | 1.15 | |

| Both Non-Citizens | ------ | ------ | |

| Wald χ2 | 40.34*** | .60 | |

Note: The dependent variable is coded as: (1) excellent/very good vs. (0) good/fair/poor. Estimates are based on weighted data with adjustments for complex sample design. Model 2 includes all covariates.

p < .05;

p< .01;

p< .001.

Although some inferences are not highly sensitive, variation in estimates of the shares of children in categories (Table 3) and children that are in excellent or very good health (Table 4) indicate that alternative procedures should be considered. A major assumption of combinatorial measures is that a single variable constructed from both parents' statuses provides more information than can be obtained from each parent separately. This assumption is evaluated here with tests for interactions based on a model limited to main effects and interaction terms (Wald χ2=7.95, p=.54), as well as a “full” model with all covariates (Wald χ2=11.77, p=.23). The nonsignificant tests suggest that combining mother's and father's status does not necessarily provide more information than considering each separately.

Table 6 presents odds ratios from logistic regressions with each parent's status treated separately. Model 1 presents bivariate estimates and Model 2 presents multivariate estimates from a model with both mother's and father's status, but no other covariates. The remaining models add specific sets of covariates to identify the potential sources of associations.

Table 6. Odds Ratios from Logistic Regressions: Child Health on Separate Statuses.

| Bivariate | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | |

| Mother's Status | |||||||

| Native Born (US) | 3.26*** | 2.24*** | 2.27*** | 2.23*** | 1.84** | 1.21 | 1.17 |

| Naturalized | 2.36*** | 2.25*** | 2.27*** | 2.32*** | 1.89** | 1.57+ | 1.50 |

| Permanent | 1.90*** | 1.82** | 1.84** | 1.83** | 1.70** | 1.65** | 1.63* |

| Undocumented (ref.) | ----- | ----- | ----- | ----- | ----- | ----- | ----- |

| Wald χ2 | 70.95*** | 20.69*** | 21.71*** | 19.77*** | 11.93*** | 22.58*** | 8.23* |

| Father's Status | |||||||

| Native Born (US) | 3.22*** | 1.87** | 1.87** | 1.86** | 1.43 | 1.43 | 1.20 |

| Naturalized | 1.39 | .89 | .89 | .89 | .76 | .81 | .73 |

| Permanent | 1.37 | .92 | .92 | .92 | .82 | .86 | .78 |

| Undocumented (ref.) | ----- | ------ | ---- | ------ | ------ | ------ | ----- |

| Wald χ2 | 46.45*** | 12.99** | 12.90** | 12.55** | 7.96* | 6.25 | 4.99 |

| Visited Doctor | .85 | .69 | |||||

| Insurance | 1.03 | 1.22 | |||||

| Single Parent Family | .79 | .83 | |||||

| Child's Age | .94** | .94** | |||||

| Poverty | |||||||

| ≥300% | 1.37 | 1.29 | |||||

| 200-299% | 1.81* | 1.77* | |||||

| 100-199% | 1.25 | 1.23 | |||||

| ≥99% (ref.) | ----- | ----- | |||||

| Wald χ2 | 5.35 | 5.16 | |||||

| Education | |||||||

| College Grad | 2.32** | 1.95* | |||||

| Some College | 1.24 | 1.03 | |||||

| H.S. Grad | 1.71* | 1.50 | |||||

| Not H.S. (ref.) | ----- | ----- | |||||

| Wald χ2 | 10.62* | 6.43 | |||||

| English Proficient | 2.67*** | 2.39*** | |||||

Note: The dependent variable is coded as: (1) excellent/very good vs. (0) good/fair/poor. Estimates are based on weighted data with adjustments for complex sample design.

p < .05;

p< .01;

p< .001.

Model 1 shows greater variation in health across categories of mother's status than father's status. The odds of being healthy are 1.9 times higher for children of permanent resident mothers and 2.4 times higher for children of naturalized mothers than for those with of undocumented mothers. The odds ratio for native-born mothers is greater still at 3.3, which is similar to that for native-born fathers (3.2). However, the positive bivariate differences between children of undocumented fathers and both naturalized citizen (OR=1.39, p=.082) and permanent resident fathers (OR=1.37, p=.098) are not significant using conventional criteria. These results and the substantial difference in the Wald tests suggest that children's health is most strongly related to mother's status.

In Model 2, mothers' and fathers' statuses remain significant overall when both are included in the same model, but the significance of the latter stems from U.S.-born fathers. All estimates that were significant using the formal .05 criterion in the bivariate models remain significant and substantial despite the reduction of the parameter estimates for the native born.

Insights into the factors that account for these patterns are provided in the remaining models. Starting with mother's status, we see that the estimates are impervious to controls for medical care access and utilization which, in turn, are not associated with child health (Model 3). These estimates are also robust when demographic (child's age and family structure in Model 4) and socioeconomic characteristics (poverty and education in Model 5) are controlled. However, except for difference between children with undocumented and permanent resident mothers, all legal status differences in child health are non-significant when differences in English proficiency are controlled (Model 6). The naturalization process requires English acquisition, and this is positively associated with the reported health of children (OR=2.67).

In contrast, attention to the native born is required to understand why father's status matters. Models 5 and 6 suggest that poverty, education, and language all play a role in this association. The significantly higher likelihood of excellent or very good health among children of native-born fathers relative to children with undocumented fathers becomes non-significant when poverty and parental education (Model 5) and parental English proficiency (Model 6) are taken into account. Although the role of poverty is equivocal (i.e. Wald χ2 = 5.35, p = n.s.), education promotes health independently of its association with English proficiency. The results are insensitive to alternative model specifications. Estimates for mother's status are not affected by father's status (and vice versa) and substituting language of interview for proficiency does not affect inferences.

Model 7 includes all covariates. As in Models 5 and 6, both father's status overall (Wald χ2 = 4.99, p = n.s.) and the specific estimate for native-born fathers (OR=1.20, p = n.s.) are not significant. However, the covariates do not account for all differences among those with foreign-born mothers (Wald χ2 = 8.23, p <.05). The odds ratio of 1.63 for those with permanent resident mothers remains significant (p<.05). Children with “documented” foreign-born mothers are more likely to than those with undocumented mothers to be in very good or excellent health, regardless of the controls.

The implications of these results for combinatorial strategies are important. The significant difference in the odds ratios for the contrast between children of permanent resident mothers and undocumented mothers in all models suggests that schemes that conflate these categories result in a loss of information about how parental legal status affects child health. Also, switching the reference category to the native born indicates that (in Models 1-4) those with permanent resident and undocumented parents, regardless of parent, are less likely than those with native-born parents to be healthy (not shown). This extends to children with naturalized citizen fathers (OR=.43, p<.001), but not naturalized citizen mothers (OR = .72, p = n.s.). Collectively, these results indicate that conflating adjacent citizenship categories (native-born and naturalized citizens) or adjacent non-citizen categories (permanent resident and undocumented) may lead to a loss of information about important differences in child health.

Conclusion

As a legacy of high levels of undocumented immigration from Mexico to the United States, legal status has garnered attention as a potential fundamental cause of inequality in child health. However, the accumulation of evidence has been hampered by the absence of information on legal status in most widely-used surveys. Although noteworthy exceptions support the intuition that legal status is critical for children's health, there is little agreement on measurement. This lack of agreement matters because it affects inferences about the size of different legal status groups and the association between legal status and health. Thus, we investigated linkages between procedures and evidence to guide basic research. These issues are also relevant for policy.

The results show that measurement decisions require scrutiny, including choices about whether to consider children's legal status. For Mexican-origin children ages 0-11 in California, family legal status can be based solely on parents because almost all children are native born (97%). Another decision is whether to limit the child's “family” to co-resident parents or to include non-resident parents. Exclusion of non-resident parents may be undesirable because they can contribute to children's well-being, especially among groups characterized by transnational ties or temporary absences. Although a case could made to exclude absent parents who have no involvement with either the child or the resident parent, most health surveys do not include sufficient information to address this issue. Regardless, this is only a decision to be made when research is based on surveys that include information on resident and non-resident parents.

Our investigation of two-parent combinatorial strategies showed that measurement matters for inferences about the size and reported health of different population segments. The share of Mexican-origin children in the lowest status group ranges from 21% with high-status anchoring to 35% with low-status anchoring among the non-public-use approaches, a difference of nearly 400,000 children. The public-use approach places 55% (600,000 additional children) in the lowest category due to the conflation of permanent residents and the undocumented.

Such differences matter because the prominence of issues on the public agenda and priorities for services often reflect the number of people affected (Best 2001). In this vein, no combinatorial strategy fully reveals the potential vulnerability of children to the deportation of a parent because vulnerability depends in part on the number of parents at risk. Those with one and two undocumented parents are separated under high-status anchoring, a procedure that hides the former by classifying them with the high-status parent. Under low-status anchoring, those with one and two undocumented parents are combined. This obscures understanding if risks reflect the number of undocumented parents. In California, almost 600,000 (21.1%) of Mexican-origin children ages 0-11 have two undocumented parents, 120,000 (4.2%) only have an undocumented mother and 260,000 (9.3%) only have an undocumented father.

Combinatorial strategies may also obscure differences in child health by legal status. Ignoring one idiosyncratic value, the point estimate for the percentage in excellent or very good health among those with at least one undocumented parent ranges from 51% (both undocumented) to 75% (undocumented mother and native-born father). Although children are not distributed evenly across all 16 possible combinations of parents' legal statuses, combinatorial strategies may introduce grouping error by merging categories that have dissimilar outcomes.

This draws attention to alternative procedures, but collapsing categories may still be warranted for some topics. A key theoretical assumption requiring explicit consideration concerns the opportunity structure. Legal status is theoretically important as a determinant of access to opportunities that have cascading effects on resources, health care and health. Low-status anchoring assumes that restricted opportunities for children with an unauthorized parent are paramount. High-status anchoring assumes that expanded opportunities for children with an authorized parent are paramount. These assumptions merit scrutiny.

Another combinatorial assumption is that mothers and fathers are equivalent for classifying families. This is problematic because gender affects access to opportunities and responsibilities in the domestic sphere. Mothers typically have greater responsibility than fathers for caregiving. Thus, measures of legal status that are gender neutral may sacrifice insights by blurring distinctions between mothers and fathers.

These issues must be considered in research on how parental documentation status influences family circumstances. Identifying those who are vulnerable due to their parents' undocumented status is important if citizen (or any) children receive fewer public health care benefits than they are entitled to or if vulnerabilities are exacerbated by fear of parental deportation. Various combinatorial strategies generate different estimates of the population that is “at risk” of being negatively affected by these issues. The low status approach generates larger estimates because it includes children with one or two undocumented parents and the high status approach generates lower estimates because the low status category is restricted to those with two undocumented parents. Both strategies fall short for obscuring segments or hiding segments of the population with different risks.

The decision to blur distinctions should not be made a priori. On the contrary, the decision to combine parents' legal statuses requires tests for interaction to determine whether both variables considered jointly provide more information than both variables considered separately. Nonsignificant tests in our study indicated that separate measures of status for each parent best convey the relationship between parental legal status and child health. Analyses using this strategy suggest that the status of mothers has greater implications than that of fathers and different mechanisms may be involved for each. Thus, genderless combinatorial strategies may obscure facets of relationships.

There is also a need to look beyond health care access and utilization to other pathways from legal status to health, including those that involve school, neighborhood and policy environments. For example, qualitative studies indicate that upsurges in deportations have increased the economic insecurity and isolation of families, along with the stress of daily living for those who fear that a parent may be forcibly removed (Dreby 2012). This may have negative repercussions for children's emotional and physical health. One empirical investigation with a representative sample of Mexican-origin children in Los Angeles indicates that those with undocumented mothers are more likely to be distressed than both their documented and native-born counterparts even after socio-economic, familial and neighborhood characteristics are controlled (Anonymous 2015).

In closing, there are additional avenues for future research. Mexican-origin children in California are important in their own right, but the generalizability of findings across time, place and origin groups remains to be seen. Expanding this line of research to some populations will require the ability to identify those who are unauthorized residents and authorized residents with valid visas, refugee status and Temporary Protected Status. Moreover, attention to English proficiency is needed. English proficiency is a potential indicator of acculturation to mainstream norms for subjectively framing and expressing health, as well as a requirement for naturalization and a skill that expands access to health-related information, facilities and high-quality care along with labor market opportunities (Lara et al. 2005). Language may also be important for different reasons for mothers and fathers. Last, future studies must take the social organization of families into account. For immigrant families, this typically involves mothers caring for children, along with older siblings caring for younger siblings. Such possibilities point to the need to take gender seriously. Gender is a key organizing principle of social life that needs to be brought to the forefront, rather than assumed away, in efforts to illuminate legal status as a fundamental cause of child health in immigrant families.

Measurement of family legal status is typically based on information about parents.

Parent-based combinatorial measurement strategies are evaluated.

Inferences about children in “undocumented families” are sensitive to measurement.

Gender-neutral strategies that treat mothers and fathers the same are questionable.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development to support the “Mexican Children of Immigrants Program Project” (5P01HD062498-04) and the Population Research Institute (R24HD041025).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

R.S. Oropesa, Department of Sociology, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802, phone: (814) 865-1577, fax: (814) 863-7216

Nancy S. Landale, Email: nsl3@psu.edu, Department of Sociology, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802.

Marianne M. Hillemeier, Email: mmh18@psu.edu, Department of Health Policy and Administration, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802.

References

- Aday LA, Andersen R. A framework for the study of access to medical care. Health Serv Res. 1974;9(3):208–220. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen R, Newman JF. Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. Milbank Q. 2005;83(4):1–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachmeier J, Van Hook J, Bean FD. Can we measure immigrants' legal status? Lessons from two U.S. Surveys. Int Migr Rev. 2014;48:538–566. doi: 10.1111/imre.12059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bean FD, Leach MA, Brown SK, Bachmeier JD, Hipp JR. The educational legacy of unauthorized migration: comparisons across U.S.-immigrant groups in how parents' status affects their offspring. Int Migr Rev. 2011;45:348–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-7379.2011.00851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best J. Damned Lies and Statistics. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi SM. Family change and time allocation in American families. Ann Am Acad Polit SS. 2011;638:21–44. [Google Scholar]

- California Health Interview Survey. CHIS 2011-2012 Methodology Series. Los Angeles, CA: UCLA Center for Health Policy Research; 2014. Report 4 – response rates. [Google Scholar]

- Coltrane S, Shih K. Gender and household labor. In: Crisler JS, McCreary DR, editors. Handbook of Gender Research in Psychology. New York: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dreby J. The burden of deportation on children in Mexican immigrant families. J Marriage Fam. 2012;74(7):829–845. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GV, Hotz J, Trejo S. Hispanics in the U.S. labor market. In: Tienda M, Mitchell F, editors. Hispanics and the Future of America. National Research Council; Washington, D.C.: 2006. pp. 228–290. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Barrera A, Lopez MH. Washington, D.C.: Pew Hispanic Center; 2013. [Accessed February 27, 2015]. A demographic portrait of Mexican-Origin Hispanics in the United States. http://www.pewhispanic.org/2013/05/01/a-demographic-portrait-of-mexican-origin-hispanics-in-the-united-states/ [Google Scholar]

- Groves RM. Nonresponse rates and nonresponse bias in household surveys. Public Opin Quart. 2006;70(5):646–675. [Google Scholar]

- Groves RM, Peytcheva E. The impact of nonresponse rates on nonrsponse. Bias Public Opin Quart. 2008;72(2):167–189. [Google Scholar]

- Guendelman S, Angulo V, Wier M, Oman D. Access to health care for children and adolsescents in working poor families: Recent Findings from California. Med Care. 2005a;43(1):68–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guendelman S, Angulo V, Wier M, Oman D. Overcoming the odds: access to care for immigrant children in working poor families in California. Matern Child Hlth J. 2005b;9(4):351–362. doi: 10.1007/s10995-005-0018-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guendelman S, Wier M, Angulo V, Oman D. The effect of child-only insurance coverage and family coverage on health care access and use: recent findings among low-income children in California. Health Serv Res. 2006;41(1):125–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00460.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idler EL, Benyami Y. Self-rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studies. J Health Soc Behav. 1997;38:21–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jylhä M. What is self-rated health and why does it predict mortality? towards a unified conceptual model. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69:307–316. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Omitted for double-blind reviewing 2015 [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Omitted for double-blind reviewing 2006 [Google Scholar]

- Lara M, Gamboa C, Kahramanian MI, Morales LS, Hayes Bautista DE. Acculturation and Latino health in the United States: a review of the literature and sociopolitical context. Annual Review of Public Health. 2005;26:367–97. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Phelan J. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. J Health Soc Behav. 1995:80–94. Extra Issue. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS, Tourangeau R. Where do we go from here? Nonresponse and Social Measurement. Ann Am Acad Polit SS. 2013;645:185–221. doi: 10.1177/0002716212464191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. Children's Health, The Nation's Wealth: Assessing and Improving Child Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega AN, Horwitz S, Fang H, Kuo AA, Wallace SP, Inkelas M. Documentation status and parental concerns about development in young US children of Mexican Origin. Acad Pediatr. 2009;9(4):278–282. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega AN, Fang H, Perez VH, Rizzo JA, Carter-Pokras O, Wallace S, Gelberg L. Health care access, use of services, and experiences among undocumented Mexicans and other. Latinos Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(21):2354–2360. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.21.2354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passel JS. Demography of immigrant youth: past, present, and future. Future Child. 2011;21(1):19–42. doi: 10.1353/foc.2011.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez VH, Fang H, Inkelas M, Kuo A, Ortega AN. Access to and utilization of health care by subgroups of Latino children. Med Care. 2009;47(6):695–699. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318190d9e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. Assessing the representativeness of public opinion surveys. The Pew Research Center for the People & The Press; Wasdhington, D.C: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Phelen JC, Link BG, Tehranifar P. Social conditions as fundamental causes of health inequalities: theory, evidence, and policy implications. J Health Soc Behav. 2010;51(5):s28–s40. doi: 10.1177/0022146510383498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero VC. Everyday Law for Immigrants. Boulder, CO: Paradigm; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Stein REK, Siegel MJ, Bauman LJ. Double jeopardy: what social risk adds to biomedical risk in understanding child health and health care utilization. Acad Pediatr. 2010;10(3):165–171. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens GD, West-Wright CN, Tsai KY. Health insurance and access to care for families with young children in California, 2001-2005: Differences by Immigration Status. J Immigr Minor Health. 2010;12(3):273–281. doi: 10.1007/s10903-008-9185-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. ASPE Issue Brief. Washington, DC: 2012. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. Overview of immigrants' eligibility for SNAP, TANF, Medicaid, and CHIP. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas AJ. Assimilation effects beyond the labor market: time allocations of Mexican immigrants to the US. Rev Econ Household. 2014 Published online June, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas Bustamante A, Fang H, Garza J, Carter-Pokras O, Wallace S, Rizzo J, Ortega A. Variations in healthcare access and utilization among Mexican immigrants: The Role of Documentation Status. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012;14(1):146–155. doi: 10.1007/s10903-010-9406-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Hook J, Bachmeier JD, Coffman DL, Harel O. Can we spin straw into gold? An evaluation of immigrant legal status imputation approaches. Demography. 2015;52:329–354. doi: 10.1007/s13524-014-0358-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viruell-Fuentes EA, Morenoff JD, Williams DR, House JS. Language of interview, self-rated health, and the other Latino health puzzle. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(7):1306–1313. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.175455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa H. Immigrants Raising Citizens: Undocumented Parents and their Young Children. Russel Sage Foundation; New York: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa H, Kalil A. The effects of parental undocumented status on the developmental contexts of young children in immigrant families. Child Dev Perspect. 2011;5(4):291–297. [Google Scholar]

- Ziol-Guest K, Kalil A. Health and medical care among the children of immigrants. Child Dev. 2012;83(5):1494–1500. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]