Abstract

Inflammation is a beneficial host response to infection but can contribute to inflammatory disease if unregulated. The TH17 lineage of T helper (TH) cells can cause severe human inflammatory diseases. These cells exhibit both instability (they can cease to express their signature cytokine, IL-17A)1 and plasticity (they can start expressing cytokines typical of other lineages)1,2 upon in vitro re-stimulation. However, technical limitations have prevented the transcriptional profiling of pre- and post-conversion TH17 cells ex vivo during immune responses. Thus, it is unknown whether TH17 cell plasticity merely reflects change in expression of a few cytokines, or if TH17 cells physiologically undergo global genetic reprogramming driving their conversion from one T helper cell type to another, a process known as transdifferentiation3,4. Furthermore, although TH17 cell instability/plasticity has been associated with pathogenicity1,2,5, it is unknown whether this could present a therapeutic opportunity, whereby formerly pathogenic TH17 cells could adopt an anti-inflammatory fate. Here we used two new fate-mapping mouse models to track TH17 cells during immune responses to show that CD4+ T cells that formerly expressed IL-17A go on to acquire an anti-inflammatory phenotype. The transdifferentiation of TH17 into regulatory T cells was illustrated by a change in their signature transcriptional profile and the acquisition of potent regulatory capacity. Comparisons of the transcriptional profiles of pre- and postconversion TH17 cells also revealed a role for canonical TGF-β signalling and consequently for the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) in conversion. Thus, TH17 cells transdifferentiate into regulatory cells, and contribute to the resolution of inflammation. Our data suggest that TH17 cell instability and plasticity is a therapeutic opportunity for inflammatory diseases.

TH17 cells are characterized by secretion of IL-17A, expression of chemokine receptor CCR6 and transcriptional factor RORγt6. Their pathogenicity is limited by Foxp3+ TReg and T regulatory type 1 (TR1) cells7,8. Foxp3+ TReg cells are characterized by the transcription factor Foxp3, whereas TR1 cells secrete high levels of the anti-inflammatory IL-10 and express cell-surface markers CD49b and LAG-3 (refs 7, 9–11). Although TH17, Foxp3+ TReg and TR1 cells are functionally distinct subsets, they share some features. They are abundant in the intestine, their differentiation is promoted by transforming growth factor β (TGF-β)12, and both TH17 and TR1 cells express CD49b and high levels of the transcription factor AhR9,13. Moreover TH17 cells can transiently co-express RORγt with Foxp3 (refs 14, 15), and IL-17A with IL-10 (refs 10, 16–18).

Despite these similarities, it is unclear if TH17 cells transiently co-express a limited number of genes that are typically associated with regulatory CD4 T cells, or if they can undergo genetic and functional reprogramming resulting in transdifferentiation from one TH type to another.

To track TH17 cell fate towards regulatory states in vivo, we crossed IL-17A fate reporter mouse (IL-17ACRE × Rosa26 STOPfl/fl YFP (R26YFP))1 with IL-17AKatushka IL-10eGFP Foxp3RFP triple reporter mouse model9,19. We call the resulting mouse model Fate+ (Methods, Extended Data Fig. 1a, b) in which, cells that have previously expressed high level of Il17a, delete the stop cassette preceding R26YFP and are permanently marked by YFP expression. This enabled us to test if YFP+ cells express IL-17A, IL-10 and Foxp3 ex vivo without in vitro restimulation.

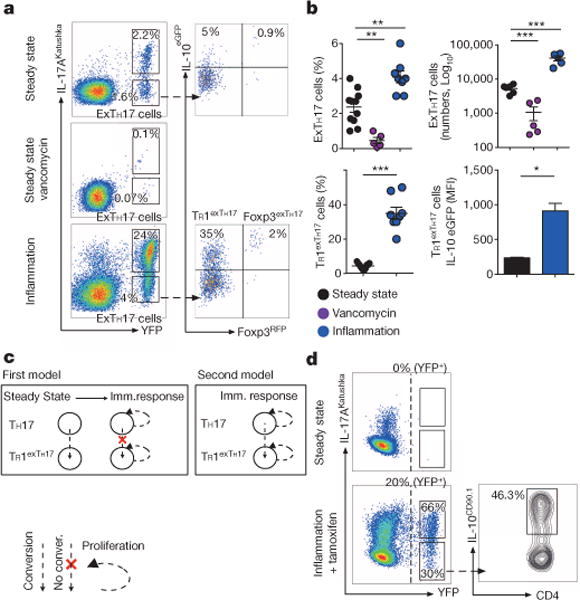

In steady state TH17 cells are mainly in the small intestine due to the presence of segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB)12. Among intestinal CD4Tcells approximately half (48% ± 2.7,n = 18)of the cells that had expressed IL-17A no longer expressed this cytokine. We call these cells exTH17 cells (IL-17AKatushka− YFP+). Some (4.3% ± 0.3, n = 18) intestinal exTH17 cells expressed IL-10eGFP, and some (1% ± 0.2, n = 18) of them were Foxp3RFP positive (Fig. 1a, b). ExTH17 IL-10eGFP+ cells were distinct from TH1, TH2 and TH17 cells since they expressed trace amounts of IFN-γ, were negative for IL-4, and expressed low levels of RORγt and CCR6 respectively (Extended Data Fig. 1c–e). Finally, to test if the presence of TH17 and consequently exTH17 was due to SFB, we treated the mice with vancomycin; both populations were reduced (Fig. 1a, b). Thus under homeostatic conditions, intestinal TH17 cells lose IL-17A expression and a fraction of these exTH17 cells express regulatory features but not characteristic signatures of TH1, TH2 and TH17 cells.

Figure 1. TH17 cells lose IL-17A and acquire IL-10 in vivo.

a, Flow cytometric analysis of small intestinal CD4+ T cells. Steady state, vancomycin-treated, or treated with anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody (inflammation) depicted. b, Number and frequencies of exTH17 cells (gated on CD4+ T cells) and TR1exTH17 cells (gated on exTH17 cells) are cumulative of two and three independent experiments respectively. IL-10 mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) data (n = 3 biological replicates) of one representative experiment out of three are shown. Mean ± s.e.m.; *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.005, ***P ≤ 0.0005 by ANOVA (Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test) or by t-test for percentage (MannWhitney U-test, two tailed) and MFI (paired t-test, two-tailed) of TR1exTH17 cells. c, Hypotheses: first model, expansion of pre-existing TR1exTH17; second model, conversion of TH17 cells expanded/induced over the course of immune response. d, Flow cytometric analysis of small intestinal CD4+ T cells isolated from iFate mice in steady state, and upon anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody and tamoxifen (Inflammation + tamoxifen) treatment. Frequencies of YFP+ cells, TH17 and exTH17 (gated on YFP+ cells), and of IL-10+ cells (gated on exTH17) are representative of two experiments (n = 6 biological replicates).

We next analysed TH17 cell plasticity during a self-limiting inflammatory response induced by the injection of anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody8. Intestinal TH17 cell expansion was followed by increased exTH17 cells expressing high IL-10eGFP (Fig. 1a, b), although few (2% ± 0.2, n = 8) of these cells co-expressed IL-10eGFP and Foxp3RFP. The low number of Foxp3+ exTH17 cells prevented, at the time, further studies on these cells.

As exTH17 IL-10eGFP+ cells resembled TR1 rather than TH17 cells, we examined them for cell-surface markers that identify TR1 and TH17 cells – LAG-3 (ref. 9), and CCR6 (ref. 12). A high percentage of exTH17 IL-10eGFP+ cells were LAG-3 positive but CCR6 negative. Interestingly, in contrast to chronically activated and colitogenic TH17 cells, which are LAG-3 negative9, TH17 cells expressed low levels of LAG-3 cells during this self-limiting immune response, supporting the idea of an ongoing maturation towards a TR1 cell phenotype. As expected9 CD49b was equally expressed among the three populations (Extended Data Fig. 2a–c). Like TR1, exTH17 IL-10eGFP+ cells expressed low levels of RORγt (Extended Data Fig. 2d) and only trace levels of characteristic TH1 and TH2 genes (Extended Data Fig. 2e). In conclusion, during a self-limiting response, some exTH17 cells resemble TR1 (hereafter named TR1exTH17) rather than TH17 cells.

We next determined TH17 fate during a non-resolving immune response. DNIL-10R transgenic mice have an impairment in IL-10R signalling in CD4 T cells and when treated with anti-CD3 the inflammation does not resolve, but leads to TH17-associated mortality8. We found that in Fate DNIL-10R mice, in which immune response cannot be terminated, exTH17 cells tend to acquire a TH1-like phenotype rather than a TR1-like phenotype (Extended Data Fig. 3a–c).

The presence of TR1exTH17 cells under steady state conditions suggests two models to explain TR1exTH17 cell formation during an immune response. First, TH17 might convert to TR1 cells in steady state and during an immune response, such cells expand (Fig. 1c). Alternatively, TH17 cells might convert to TR1 cells over the course of the response (Fig. 1c). To distinguish these possibilities, we generated a tamoxifen inducible IL-17AeGFP fate mouse model ((iFate) Methods, Extended Data Fig. 4a–c) in which TH17 cells become YFP+ only after tamoxifen treatment (Fig. 1d and Extended Data Fig. 4d). Through the use of the iFate model we observed that TH17 still convert into TR1 cells, specifically during the immune response (anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody + tamoxifen; Fig. 1d).

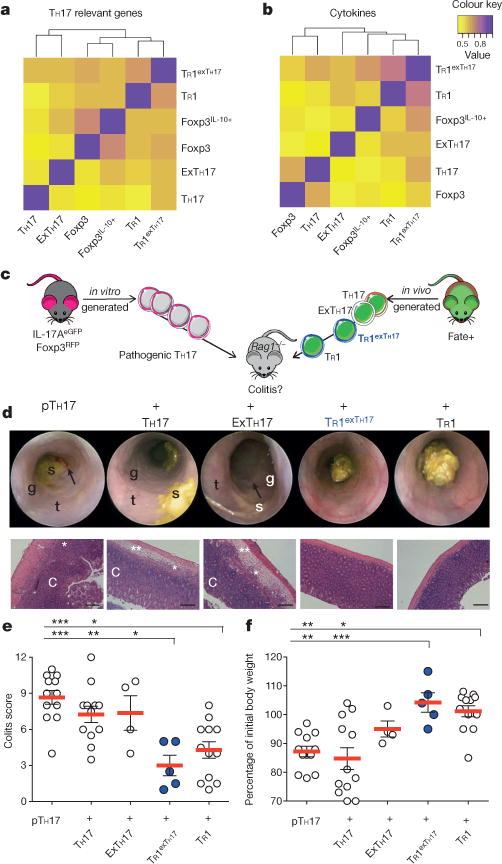

We next examined whether TR1exTH17 cells undergo transcriptional reprogramming during their conversion from Trh17 into TR1 cells. We sequenced the transcriptome of intestinal TR1exTH17 cells and compared it to the transcriptomes of bona fide TR1 and TH17 cells isolated from the same mice (Extended Data Fig. 5a, b). As controls, we used exTH17 IL-10−, Foxp3+ TReg and Foxp3+ Treg IL-10+ cells, again isolated from the same mice. To determine the relatedness of these subsets, we performed hierarchical clustering based on the expression of literature-search curated TH17-relevant genes20,21 (Supplementary Table 1). Clustering analyses revealed first that TR1 are a distinct T-cell subset, as different to TH17 or Foxp3+ TReg cells as the latter two cell types differ from each other and second that TR1exTH17 cells cluster together with TR1 rather than with TH17 cells (Fig. 2a). We also performed cytokine-restricted cluster analysis (Supplementary Table 2) showing that TR1 and TR1exTH17 cluster together (Fig. 2b). Thus, conversion of TH17 into TR1 cells is determined and/or followed by a reprogramming of the TH17-relevant transcriptional profile, a process previously described as transdifferentiation3,4.

Figure 2. TR1exTH17 cells have a similar gene expression profile and function compare with TR1 cells.

a, b, Correlative heatmaps based on the expression of TH17 related genes (n = 97) (a) and cytokine genes (n = 191) (b). The indicated cell populations were isolated from the small intestine of 10 anti-CD3 treated Fate+ mice from two independent experiments. c, Pathogenic (p)TH17 were differentiated in vitro and then injected alone or in combination with the depicted populations into Rag1−/− mice. TH17, exTH17, TR1exTH17 and TR1 cells (YFP−) were isolated from the small intestine of Fate+ mice treated with anti-CD3 mAb. d, Endoscopic and histological pictures. Scale bars: 200 μm. Endoscopy pictures show stool inconsistency (s), increased mucosal granularity (g), lack of translucency (t) and bleeding (arrow). The histological pictures show oedema (**), inflammation (*) and crypt loss (C). e, f, Endoscopic colitis score (e) and percentage of initial body weight (f). Each dot represents one mouse. Mean and s.e.m. are indicated. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.005, ***P ≤ 0.0005 by ANOVA (Tukey’s multiple comparison test).

As a final test of whether TR1exTH17 cells had completed their functional trans-differentiation from TH17 into regulatory TR1 cells, we used a TH17 cell-mediated colitis model8. We found that TR1exTH17 cells had completed their functional reprogramming since they prevented TH17 cell-mediated colitis (Fig. 2c–f).

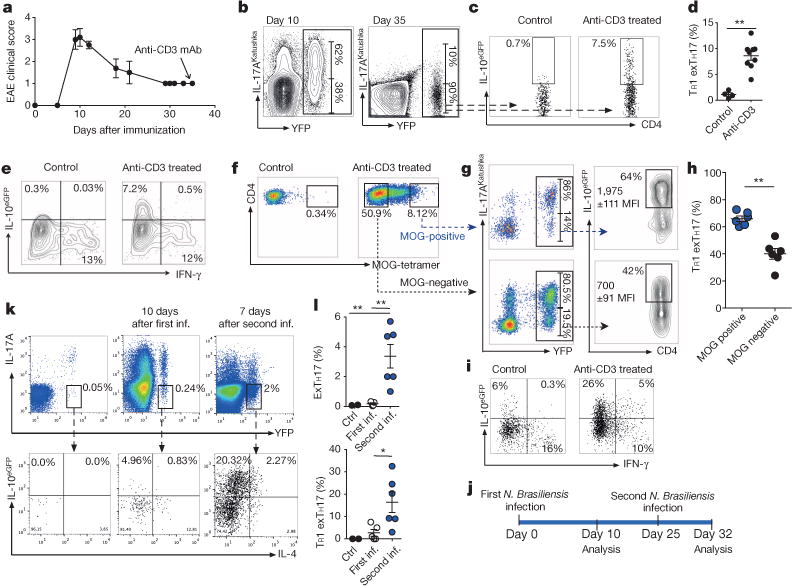

TH17 cells can also differentiate into TH1-like cells in a TH17 mediated-mouse model for multiple sclerosis (EAE) (Fig. 3a–e)1,22. We next wondered whether autoimmune-derived TH17 cells would be able to acquire a regulatory fate. Of note, after anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody treatment, which can block EAE development17, a fraction of exTH17 cells acquired IL-10, not IFN-γ (Fig. 3a–e). Thus, some exTH17 cells, which developed during an autoimmune response, can still convert into TR1 cells.

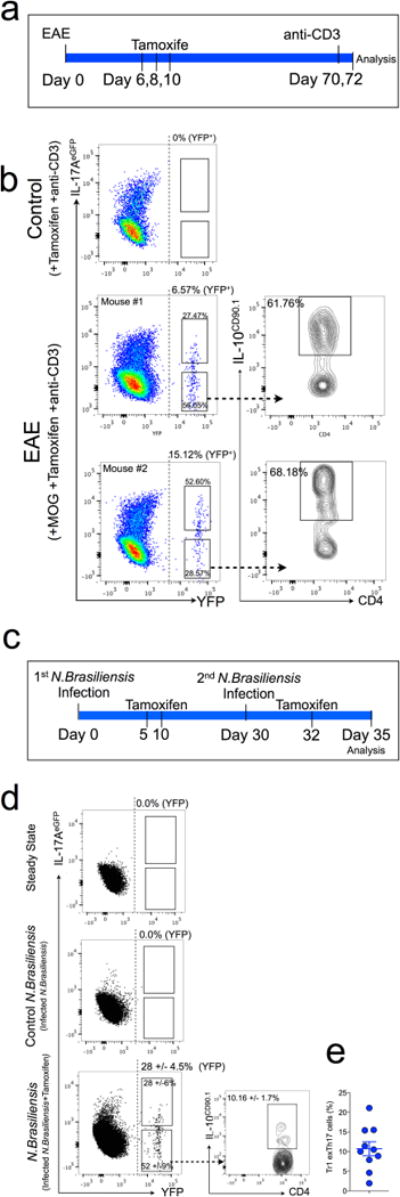

Figure 3. TR1exTH17 cell development in EAE and helminth infection.

a, Clinical EAE-score.Anti-CD3 was injected 35 days after MOG-immunization. b, Flow cytometric analysis of TH17 and exTH17 (gated on YFP+ cells) cells in dLNs. c, d, Flow cytometric analysis (c)and percentages of TR1exTH17 cells (gated on exTH17)in dLNs (d). e, IFN-γ/IL-10eGFP expression of exTH17 cells. a–e, Representative of three independent experiments. f, Flow cytometric analysis of MOG-tetramer staining of intestinal CD4 cells of EAE mice left untreated (control) or treated with anti-CD3. g, h, Representative flow cytometric analysis (g) and frequencies of TR1exTH17 (gated on MOG ± cells) (h). Each dot represents one mouse. IL-10 MFIs (average of three mice ± s.e.m.) are reported. **P ≤ 0.05 by Mann–Whitney U-test, two tailed. i, IFN-γ/IL-10eGFP expression of exTH17 isolated from small intestine of EAE mice. f–i, Representative of two independent experiments. j, Schematic of the experiment. k, l, Flow cytometric analysis and frequencies of exTH17 and TR1exTH17 from the lung (upper panel: gatedonCD4+ T cells; lower panel: gated on exTH17 cells). One experiment of three is shown. Mean ± s.e.m., *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.005 by ANOVA (Tukey’s multiple comparison test).

Furthermore, encephalitogenic TH17 cells can be recruited to the small intestine after anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody treatment17. In our current studies some intestinal T cells specific for the disease-driving antigen of EAE (myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG)) were TR1exTH17 cells. We also observed that MOG-specific exTH17 cells express IL-10 to a greater extent than non-MOG-specific exTH17 cells (Fig. 3f–i). Likewise, in iFate mice TH17 cells labelled during EAE onset converted to TR1 cells (Extended Data Fig. 6a, b). Thus pathogenic autoantigen-specific TH17 cells can convert to TR1exTH17 cells.

We next addressed if TH17 cells convert to TR1 cells during an immune response, which physiologically promotes host tolerance to infection23. Nippostrongylus brasiliensis infection elicits a type-2 immune response that drives worm expulsion24. In addition to TH2 cells, TH17 and TR1 also expand in response to N. brasiliensis9 and while IL-17 contributes to tissue damage, IL-10 prevents tissue damage24. We therefore asked if TH17 cells convert to Th2 cells25 or to TR1 cells during N. brasiliensis infection. During the primary immune response to N. brasiliensis, TH17 cells lost IL-17A expression and some showed a Th2 phenotype25. However, when we re-infected the mice with N. brasiliensis we observed TH17 conversion into a TR1 cell-phenotype (Fig. 3j–l). We confirmed these findings in iFate mice (Extended Data Fig. 6c–e). Thus, TH17 cells can become TR1 cells during the secondary response to N. brasiliensis infection and this may limit potentially destructive type 1 immune responses.

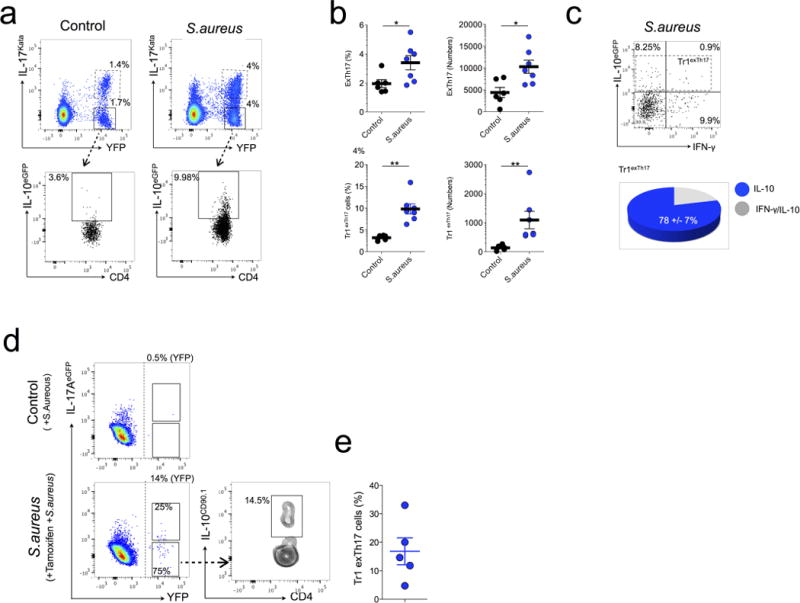

Finally we asked if TH17 conversion to TR1 cells occurs in response to acute bacterial infection. S. aureus causes sepsis in human and patients with TH17 associated gene deficiency suffer recurrent S. aureus infections26. Intravenously S. aureus infected Fate+ mice (Extended Data Fig. 7a–c) and iFate mice (Extended Data Fig. 7d, e) accumulated TH17 cells in the small intestine, as we previously showed17, and in both models TH17 cells acquired a TR1 cell phenotype.

Thus, conversion of TH17 into TR1 cells is a physiological mechanism, occurring in steady state and favoured during worm and bacterial infection.

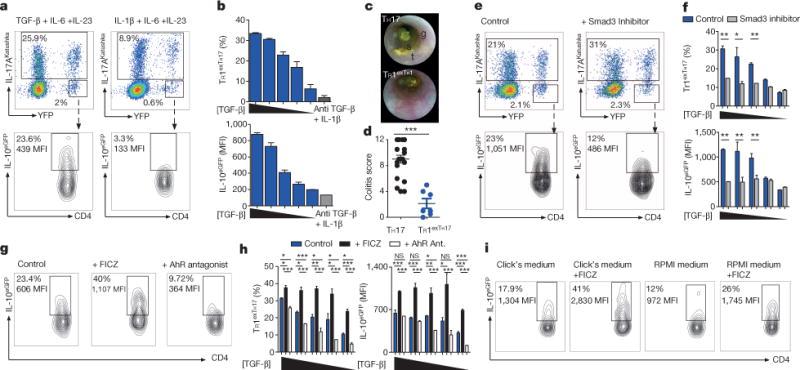

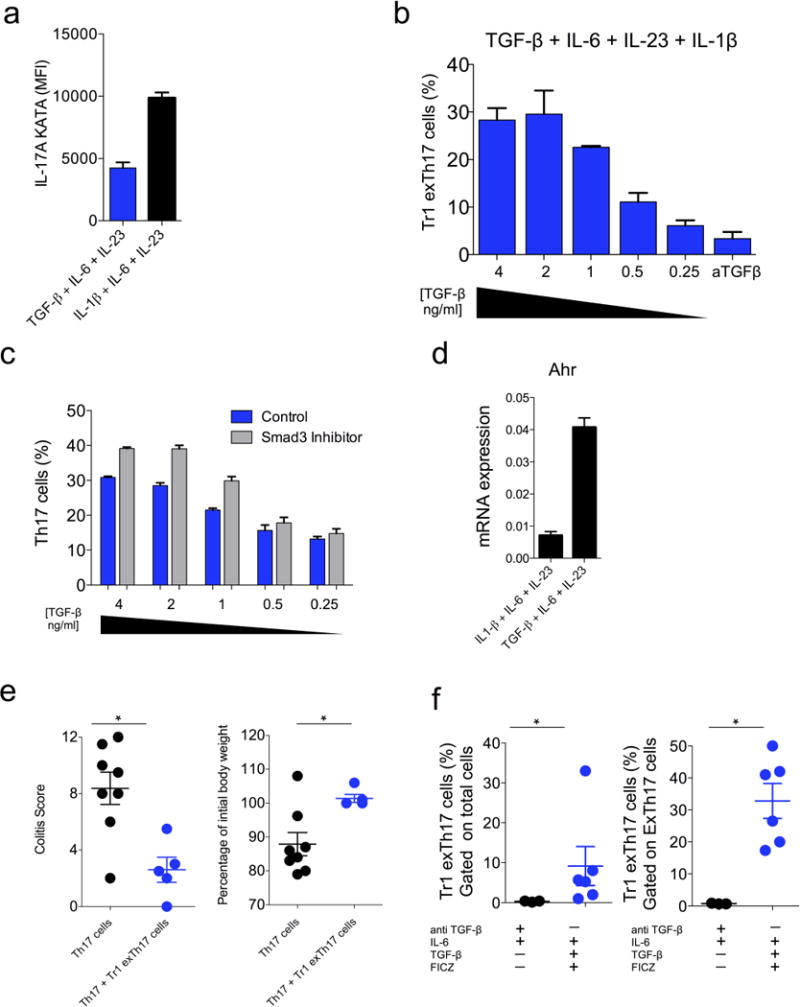

We sought candidate pathways that drive TH17 conversion into TR1 cells. Expression of twelve genes from our list of TH17-relevant genes appeared to be higher in both TR1 and TR1exTH17 cells, than in TH17 cells with 9 of them being associated with TGF-β signalling (Extended Data Fig. 8a, b). TGF-β1, in combination with IL-6 and IL-23, promotes in vitro development of potentially pathogenic TH17 cells16,27. Some of these TH17 cells expressed IL-10 (ref. 16). We found that TGF-β1, in contrast to IL-1β, which is known to induce IL-10Negative TH17 cells18,28, promoted TH17 cell plasticity and conversion to TR1 cells in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4a, b and Extended Data Fig. 9a). Since in vivo T cells are likely exposed to both TGF-β1 and IL-1β simultaneously we tested TR1exTH17 cell development in the presence of both cytokines and found that TR1exTH17 cells mature normally. However neutralizing TGF-β monoclonal antibody impaired the development of TR1exTH17 cells (Extended Data Fig. 9b). Importantly, while TH17 cells generated with TGF-β1/IL-6/IL-23 are able to promote colitis, TR1exTH17 cells generated under the same conditions failed to induce disease. Thus, TGF-β1 is important for TR1exTH17 development and despite TGF-β1, TH17 cells remain colitogenic as long as they do not convert into TR1 cells (Fig. 4c, d).

Figure 4. TGF-β1 via Smad3, and AhR support the conversion of TH17 to TR1.

TH17 cells were differentiated in vitro in the presence of IL-6, IL-23 with TGF-β1 or with IL-1β and anti-TGF-β monoclonal antibody. TGF-β1 was diluted 1:2 starting from 4 ng ml−1. a, Flow cytometric analysis of TH17, exTH17 and TR1exTH17 (gated on exTH17). b, Percentages and IL-10 MFI of TR1exTH17 cells. Technical replicates (n = 2) of one experiment out of seven. c, d, Endoscopic pictures and score of mice injected with TH17 or TR1exTH17 cells polarized with TGF-β1. Stool inconsistency (s), increased mucosal granularity (g) and a lack of translucency (t). Each dot denotes one biological replicate. Mean and s.e.m., ***P ≤ 0.0005 by Mann Whitney U-test, two tailed. e, Flow cytometric analysis of TH17, exTH17 and TR1exTH17 cells cultured in the presence of TGF-β1 (diluted as above), IL-6, IL-23 ± Smad3 inhibitor. f, Percentages and IL-10 MFI of TR1exTH17 cells. Technical replicates (n = 3) of one experiment out of five are shown. Mean and s.e.m., *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.005 by paired t-test. g, Flow cytometric analysis of TR1exTH17 (gated on exTH17) cultured in the presence of TGF-β1 (diluted as above), IL-6, IL-23 ± AhR ligand (FICZ) or AhR antagonist. h, Percentages and IL-10 MFI of TR1exTH17 (gated on exTH17). Technical replicates (n = 3) of one experiment out of five are shown. Mean and s.e.m.; *P ≤ 0.005, **P ≤ 0.005, ***P ≤ 0.0005 by ANOVA (Tukey’s multiple comparison test). NS, non-significant. i, Flow cytometric analysis of TR1exTH17 cells cultured in the presence of TGF-β1, IL-6, IL-23 ± FICZ in the indicated medias. One experiment of two is shown.

Among the TGF-β signalling pathway molecules, Smad3 decreases RORγt activity and therefore reduces TH17 cell development29. We asked if TGF-β1 promotes TH17 to TR1 conversion by modulating Smad3. Thus, when we blocked Smad3 during in vitro TH17 differentiation, induction of TR1exTH17 cells was reduced (Fig. 4e, f and Extended Data Fig. 9c). Thus, TGF-β1, likely through Smad3, promotes TH17 to TR1 conversion.

TH17 and TR1 cells differentiated in the presence of TGF-β1 express a high level of AhR13,28. AhR promotes Il10 transactivation and TR1 generation is defective in mutant Ahrd mice13. Thus, the role of Ahr expression in potentially inflammatory TH17 cells could be to enable a switch to a regulatory fate and terminate the immune response30. Indeed, as reported28 CD4 T cells, skewed towards TH17 in the presence of TGF-β1, express high levels of AHR (Extended Data Fig. 9d). Finally, to test whether AhR activation influences TH17 to TR1exTH17 conversion we added an AhR ligand (FICZ) or AhR antagonist to the culture. FICZ significantly enhanced the development of TR1exTH17 cells while the AhR antagonist reduced the conversion (Fig. 4g, h). Moreover, when replacing Click’s medium, which is rich in AhR ligands, with RPMI, poor in AhR ligands, the development of TR1exTH17 was reduced. Adding FICZ to RPMI medium rescued the conversion (Fig. 4i). These in vitro generated TR1exTH17 cells also exhibited regulatory function (Extended Data Fig. 9e). Finally we purified intestinal TH17 cells and showed that some of these cells when re-stimulated in vitro with TGF-β1 and FICZ convert into TR1 cells (Extended Data Fig. 9f).

Overall our study shows TH17 cells can transdifferentiate to TR1 cells during an immune response and in the presence of TGF-β1, AhR activation promotes this conversion. We believe that TH17 cell plasticity might be exploited to develop new and more effective therapies that restore immune tolerance in chronic inflammatory/autoimmune diseases without incurring the deleterious side-effects associated with current systemic immunosuppressive therapies.

METHODS

Mice

C57BL/6 Rag1−/− and Rosa26floxSTOPflox eYFP mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratories. IL-17ACRE and IL-10Th1.1 (CD90.1) mice were kindly provided from B. Stockinger and C. Weaver respectively1,31. IL-17-IGCE iFate mice, Foxp3RFP, IL-10eGFP, IL-17AKatushka, IFN-γKatushka reporter mice and CD4dnIL-10Rα (DNIL-10R) were generated and breed in our laboratory. reporter mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory. The Fate+ mice results from the breeding of the original Foxp3RFP IL-10eGFP IL-17AKata mice9,17,19 with IL-17ACRE R26YFP mice1. In this model, only high level of Il17a transcription induces the expression of Cre recombinase, which deletes the stop sequence 5′ to YFP. In this mouse, cells that have previously expressed high level of Il17a, delete the stop cassette and are thus permanently marked by the expression of YFP. Importantly it has been previously described that this IL-17A fate reporter allele faithfully marks TH17 cells that have acquired full effector function1. Of note, we observed that all IL-17A bright cells are YFP+, whereas IL-17A dim cells remain YFP negative, confirming the data already published whereby only IL-17A high expressing cells, fully differentiated TH17 cells, are permanently marked with YFP1.

To generate the DNIL-10R FATE, the CD4-DNIL-10R were crossed with IL-17ACRE R26YFP IL-10eGFP Foxp3RFP.

All mice were kept under specific pathogen-free (SPF) conditions in the animal facility at Yale University. We used age- and sex-matched littermates between 12 and 20 weeks of age. Animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Yale University. Both female and male mice were used in experiments. Wherever possible, preliminary experiments were performed to determine requirements for sample size, taking into account resources available and ethical use. Exclusion criteria such as inadequate staining or low cell yield due to technical problems were pre-determined. Animals were assigned randomly to experimental groups. Each cage contained animals of all the different experimental groups expected for the mice treated with antibiotic.

Generation of inducible Fate mice

The IL-17A IRES-eGFP-CRE-ERT2 mice (iFate) mice were generated following the same targeting strategy used previously to generate the IL-17AeGFP mice17. Briefly, a cassette encoding for a fusion protein consisting of the Internal Ribosome Entry Site (IRES), eGFP, Cre and human modified Oestrogen Receptor (ERT2) (IGCE) was linked to a Frt-flanked neomycin (NEO) encoding cassette. The IGCE-NEO construct was cloned into a plasmid containing two homology arms on the Il17a gene: the 5′ homology arm corresponds to a 4,445-bp fragment of the Il17a gene to the fourteenth base pairs after the stop codon of the gene using an Asc cloning site while the 3′ homology arm of the targeting construct consists of the genomic sequence of 3,258 bp spacing from fifteenth base pairs after the stop codon of the Il17a gene using a Not cloning site.

Drug-resistant ES cell clones were screened for homologous recombination by PCR. To obtain chimeric mice, correctly targeted ES clones were injected into C57BL/6 blastocysts, which were then implanted into CD1 pseudopregnant foster mothers. Male chimaeras were bred with C57BL/6 to screen for germline transmitted offspring. Germline transmitted mice were bred with germline Flippase expressing transgenic mice to remove the neomycin gene.

Mice bearing the construct were screened by PCR and bred with germline Flp expressing transgenic mice to remove the neomycin gene. After removal of the NEO cassette, IL-17A iFate mice were crossed with R26eYFP and all of the cells that actively express IL-17A were eGFP+ but still YFP+ negative. However, unlike in Fate+ mice, IL-17A expressing cells become permanently marked as YFP+ after treatment with tamoxifen as ERT2 sequesters the Cre in the cytoplasm until tamoxifen binds to ERT2.

The efficiency of CRE-mediated recombination after tamoxifien is reported as frequencies of YFP+ cells (YFP)in Fig. 1d and Extended Data Fig. 4, 6 and 7 and is the result of the following calculation: YFP+ cells (Gate2+3)/(IL-17AeGFP+ YFP− cells (Gate 1) + YFP+ cells(Gate2+3).

Anti-CD3, antibiotic and tamoxifen treatments

Mice were injected with anti-CD3 mAb (2C11,15–50 mg per mouse) intra-peritoneally two times every other day. Usually the mice were sacrificed 4 h after the last injection, unless differently indicated. Vancomycin was dissolved in water to a final concentration of 0.5 gl−1 and administered in drinking water for 4 weeks before starting the experiment. Tamoxifen (Sigma) was dissolved in corn oil (Fluka, Sigma) to a final concentration of 20 mg ml−1. Mice were injected with tamoxifen (4 mg each) one day before each anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody injection or as depicted in the scheme of the other experiments. To avoid to interfere with the effect of anti-CD3 mAb and/or the migration of cells to the intestine, the oil + tamoxifen was injected subcutaneously. Only for the experiments involving N. brasiliensis infection we injected tamoxifen intraperitoneally (i.p.).

Lymphocyte isolation from small intestine

After removal of the Peyer’s patches, we isolated intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs) and lamina propria lymphocytes (LPLs) by incubation with 1 mM DTE at 37°C for 30 min (for IEL), followed by further digestion with collagenase from Clostridium Histolyticum (#2139 SIGMA) and DNase at 37°C for 1 h (for LPL). We then further separated cells with a Percoll gradient. Unless otherwise indicated, we isolated cells from the small intestine (duodenum, ileum and jejunum) of mice treated with antibodies to CD3.

Flow cytometry antibodies and intracellular cytokine staining

We stained mouse T cells with monoclonal antibodies to CD4 (GK1.5, Cat # 100428 or RM4-5 Cat # 100536), CD8 (53-6.7 Cat # 100722), NK1.1 (RM4-5 Cat # 100536), CD19 (6D5 Cat # 115508), CD11b (M1/70 Cat # 101216), CD11c (N418 Cat # 117318), cdTCR (GL3 Cat # 118123), CD210 (BD Bioscience, Cat # 559914), LAG-3 (C9B7W Cat # 125209), CD49b (HMa2 Cat # 103506) and CCR6 (29-2L17 Cat # 129817), all antibodies expected where indicated are purchased from eBiolegend. Importantly, CD49b and LAG-3 staining were performed at 37°C for 45 min. Although in the figure legends we referred only to CD4+ T cells, in each FACS related experiment and FACS-sorting experiment we have specifically analysed CD4+ T cells CD8−, NK1.1−, CD19−, CD11b−, CD11c−, λδTCR−. For intracellular cytokine staining the cells were re-stimulated for 3 h at 37°C with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) (Sigma, 50 ng ml−1) and ionomycin (Sigma, 1 μg ml−1) in the presence of Golgistop (BD Bioscience). Cells were then fixed in paraformaldehyde for 20 min at room temperature. After washing, the cells have been permeabilized (NP40) and stained at 4°C with anti-IL-17A (TC11-18H10.1 Cat # 506925), anti-IFNγ (BD Bioscience, Cat # 554412), anti-IL-4 (BD Bioscience, Cat # 554435) and anti-Rorγt (BD Bioscience Cat # 553178) antibodies for 30 min. Lymphocytes were re-suspended in PBS, 0.5% FBS, 5 mM EDTA and acquired with an LSRII cytometer (BD Bioscience).

In vitro TR1exTH17 cell differentiation

We FACS sorted CD4+ Foxp3RFP−IL-17AKatushka− IL-10eGFP− R26YFP− cells with FACSAria II Cell Sorter (BD Biosciences) and activated them with plate-bound monoclonal antibodies to CD3 (10 μg ml−1, 145-2C11) and CD28 (1–2 μg ml−1, PV-1) in the presence of mouse recombinant TGF-β (0.25–4 ng ml−1), IL-6 (20 ng ml−1), IL-23 (20 ng ml−1), and antibodies to IFN-γ (XMG1.2, 10 μg ml−1) and IL-4 (11B11, 10μg ml−1). When specified, IL-1β (50 ngml−1), antibodies to TGF-β(5 μg ml−1, 1D11,) and FICZ (100 nM; Enzo Life Sciences), Smad3 inhibitor (SIS3, 3 μM, EDM Millipore)32 or AhR antagonist (10 μM, EDM Millipore), were added to the culturing media. All cytokines were purchased from R&D. Click’s (Irvine Scientific) or RPMI (SIGMA-ALDRICH) (when indicated) media were supplemented with 10% FBS, L-glutammine (2 mM), penicillin (100 U ml−1) and β-mercaptoethanol (40 nM). After 4–5 days of culture, the cells were acquired at the FACS.

Foxp3RFP IL-17AKatushka IL-10eGFP triple reporter were injected with anti-CD3 mAb and 12 h after the first injection or 4 h after the third injection a pure population of intestinal CD4+ Foxp3RFP− IL-17AKatushka+ IL-10eGFP− cells were FACS sorted and restimulated in vitro in the presence of irradiated splenocytes (1:4 ratio). The cells were stimulated for 5 days in the presence of soluble anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody (2 μg ml−1), IL-6 (20 ng ml−1) and where indicated anti-TGF-β (5 μg ml−1), TGF-β (0.25 ng) and FICZ (100 nM).

RNA amplification, extraction and sequencing

We isolated intestinal lymphocytes from two independent experiments, each using 5 mice injected with anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody. The cell populations indicated in Fig. 2 were FACS-sorted from these two independent experiments and the cells of each population were pooled before the RNA extraction, amplification and sequencing. Around 5,000 cells for each population were processed. After sorting, the cells were washed 2 times (1,500 r.p.m., 2 min, 4°C) with 1 ml phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and finally suspendedin2.5 μl PBS (containing 0.5 μl RNaseOut (Invitrogen) and 0.5μl dithiothreitol (DDT) (Invitrogen)). After that, the cytoplasm RNA was isolated as described previously33,34. Briefly, 2.5 μl of 2× selected cytoplasm lysis buffer (SCLB) was added and the cells were lysed by pipetting up and down for 5 times. The entire lysate solution was spun at 8,000 r.p.m. for 5 min in a chilled centrifuge (4°C) and the supernatant (~5 μl), which contained the total cytoplasm RNA, was transferred to a PCR tube strip with individually attached dome caps (USA Scientific). The mRNA selection, reverse transcription and cDNA amplification was performed as described previously with some modifications33,34. Briefly, 5′-phosphorylated oligo-GdT24 (pGdT24) primer was used to selectively reverse transcribe mRNAs. The first strand cDNA was synthesized with Superscript Reverse Transcriptase III (Invitrogen). Then, the double-stranded cDNA (dscDNA) was generated. The cDNA was purified with the Genomic DNA Clean & Concentrator kit (Zymo). Afterwards, several steps including DNA end-blunting, 5′-end phosphorylation and ligation were performed with The End-It DNA End-Repair Kit (Epicentre) with T4 DNA ligase (Epicentre). The product was directly amplified using REPLI-g UltraFast Mini Kit (QIAGEN) and purified using the same Genomic DNA Clean & Concentrator kit (Zymo) column. Finally, 3 to 5 μg (up to 8 μg) of amplified cDNA derived from mature mRNA was obtained, which was then evaluated by PCR and fragmented to construct sequencing library.

We follow the standard Illumina HiSeq2000 protocol to make the library. Briefly, the amplicon was fragmented to an approximately 200–500 bp size range by a Bioruptor Sonicator (Diagenode). After purification with DNA Clean & Concentrator kit (Zymo), end-repairing, 3′-A tailing and ligation with adaptor was performed. Then, a 50 bp range DNA (250–300 bp) was selected by gel electrophoresis (E-gel EX 2%, Invitrogen) and barcode added by PCR using Phusion High-Fidelity DNA polymerase (NEB) for 8 cycles. The product was size selected again and the DNA concentration was quantitated by a Bioanalyzer (Agilent). Multiple samples were mixed and loaded to the Hi-Seq2000 for sequencing performed with 50 bp single-end reads.

RNA-Seq data were aligned to the Mus musculus GRCm37 genome using Tophat2 and default settings35. Duplicate reads were removed with samtools rmdup command36. Count data was generated using HTSeq-count and FPKM data was generated with Cufflinks37,38. To determine genes important for the TR1 exTH17 conversion we performed a differential expression test using DESeq2 comparing TH17 cells with TR1 exTH17 and TR1 cells. To determine which cell populations were more closely related, pearson correlation values between samples were calculated on log2 FPKM data after a maximum filter of FPKM. 1, based on the subset of genes listed in Supplementary Table 1 and 2. In order to determine the grouping of cell populations, hierarchical cluster analysis was performed on the distances based on correlation or gene expression. The linkage criteria complete was used for clustering analysis.

Real time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cells using TRIzol reagent. To synthetize the cDNA we then used the High Capacity cDNA Sythesis Kit (Applied Biosystem) and RT–PCR was performed using the TaqMan Fast Universal PCR Master Mix and TaqMan Gene Probes (Applied Biosystems) on a 7500 Fast Realtime PCR system machine (Applied Biosystem). Samples were run in duplicate or triplicate and expression levels were calculated as relative to the expression of endogenous HPRT or Polr2a.

Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and tetramers staining

Mice were immunized sub-cutaneously with an emulsion of 250 mg of MOG35–55 peptide (Yale Keck facility) and CFA (BD Difco). At the time of immunization and 48 h after, mice received 200 ng pertussis toxin (PTx, List Biological Laboratories) per each injection. The clinical score of EAE development was addressed daily according to guidelines: 0, no signs of disease; 0,5, tail weakness; 1, complete tail paralysis; 2, partial hind limb paralysis; 2,5, unilateral complete hind limb paralysis; 3, complete bilateral hind limb paralysis; 3,5, complete hind limb paralysis and partial forelimb paralysis; 4, total paralysis of forelimbs and hind limbs, moribund. All mice experiments were conduced according to IACUC policies. To identify MOG38–49 (mouse myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein 38–49, “GWYRSPFSRWH”) specific T-cells, 107 cells per ml were incubated with neauraminidase (0.5 U ml−1, neuraminidase type X from Clostridium perfringens, Sigma) in serum-free DMEM at 37°C/5% CO2 for 25min. After this, the cells were stained with the MOG38–49/I-A(b)-tetramer allophycocyanin (APC)-labelled (NIH Tetramer Facility) for 4 h, at room temperature in DMEM, 2%FBS. Cells were then stained for surface antigens and acquired at the FACS.

Nippostrongylus brasiliensis infection and isolation of lymphocytes from the lung

Third-stage larvae (L3) of N. brasiliensis were recovered from coprocultures of infected mice. We infected mice by injecting subcutaneously 625 parasites in 0.2 ml PBS at the base of the tail, as previously described9. Mice were euthanized at different time points, as described, and lymphocytes were isolated from lungs. Cell suspensions from lungs were obtained digesting the organs, previously cut in small pieces, in 10% FBS RPMI media in the presence of DNase and collagenase D, as previously described9. After digestion, cell suspensions were processed onto a Percoll gradient (40% on 100%) and lymphocytes were then processed for FACS analysis.

Staphylococcus aureus infections

S. aureus (ATCC 14458, SEB+ TSST-1−) was injected intravenously (1010 colony-forming units per mouse) into Fate+ mice not older than 7 weeks. Mice were killed 3–4 days after the injection, at a time when they displayed severe clinical symptoms of sepsis (weight loss, dehydration, lethargy) and the presence of TH17, exTH17 and TR1exTH17 cells was tested in the small intestine by FACS.

TH17 transfer colitis, endoscopic and histologic analysis

CD4+ were isolated from the IL-17AeGFP Foxp3RFP double report mice and cultured with irradiated antigen presenting cells (1:4 ratio), in the presence of soluble anti-CD3 mAb (2C11, 1 μg ml−1), IL-6 (20 ng ml−1), IL-23 (50 ng ml−1) and TGF-β1 (0.25 ng ml−1) along with neutralizing antibodies for IFN-γ (XMG1.2 clone, 10 μg ml−1) and IL-4 (11B11 clone, 10 μg ml−1). After 5 days of in vitro culture, a pure population of 10,000 pathogenic (p) TH17 cells (FACS sorted as CD4+ IL-17eGFP+ Foxp3RFP−) were injected intra peritoneally into Rag1−/− mice at 1:1 ratio with the following cell populations: TH17, exTH17, TR1 exTH17 and TR1 cells. These later populations were FACS sorted from the intestine of Fate+ 4 h after the second injections of anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody.

When indicated (Fig. 4c, d) both TH17 and TR1exTH17 cells were generated in vitro under the same condition (CD3 (10 μg ml−1) and CD28 (1–2 μg ml−1); TGF-β1 (0.25–0.5 ng ml−1), IL-6 (20 ng ml−1), IL-23 (20 ng ml−1), and antibodies to IFN-γ (10 μg ml−1) and IL-4 (10 μg ml−1)) and then sorted and transferred (n = 10,000 to 20,000 cells) into Rag-1−/− mice.

When indicated (Extended Data Fig. 9), the TR1exTH17 cells were generated in vitro in the presenceof TGF-β1 (1 ng ml−1), IL-6 (20 ng ml−1), IL-23 (20 ng ml−1), and antibodies to IFN-γ (XMG1.2, 10 mg ml−1) and IL-4 (11B11, 10 μg ml−1) and FICZ (100 nM; Enzo Life Sciences), FACS sorted and transferred (n = 10,000 cells) into Rag1−/− mice at 1:1 ratio with pTH17 cells.

Colonoscopy was performed in a blinded fashion using the Coloview system (Karl Storz, Germany). Briefly, colitis score was addressed considering the consistence of stools, granularity of the mucosal surface, translucency of the colon, fibrin deposit and vascularization of the mucosa (0–3 points for each parameter). Haematoxilin and eosin staining were performed on paraffin sections of colon previously fixed in Bouin’s fixative solutions.

Statistical analysis and FACS analysis

Statistical analysis were performed using Prism 5.0 (Graphpad Software) Paired t test, Non parametric Mann–Whitney U-test, ANOVA (post test Tukey, Bonferroni or Dunnet) were used according to the type of experiments. Log10-transformed values for cell counts were used in Fig. 1. P-values ≤ 0.05 were considered significant (*: P < 0.05; **: P < 0.005; ***: P < 0.0005); P values > 0.05; non-significant (NS). All flow cytometry data have been analysed with FlowJo (Treestar). No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample size.

Extended Data

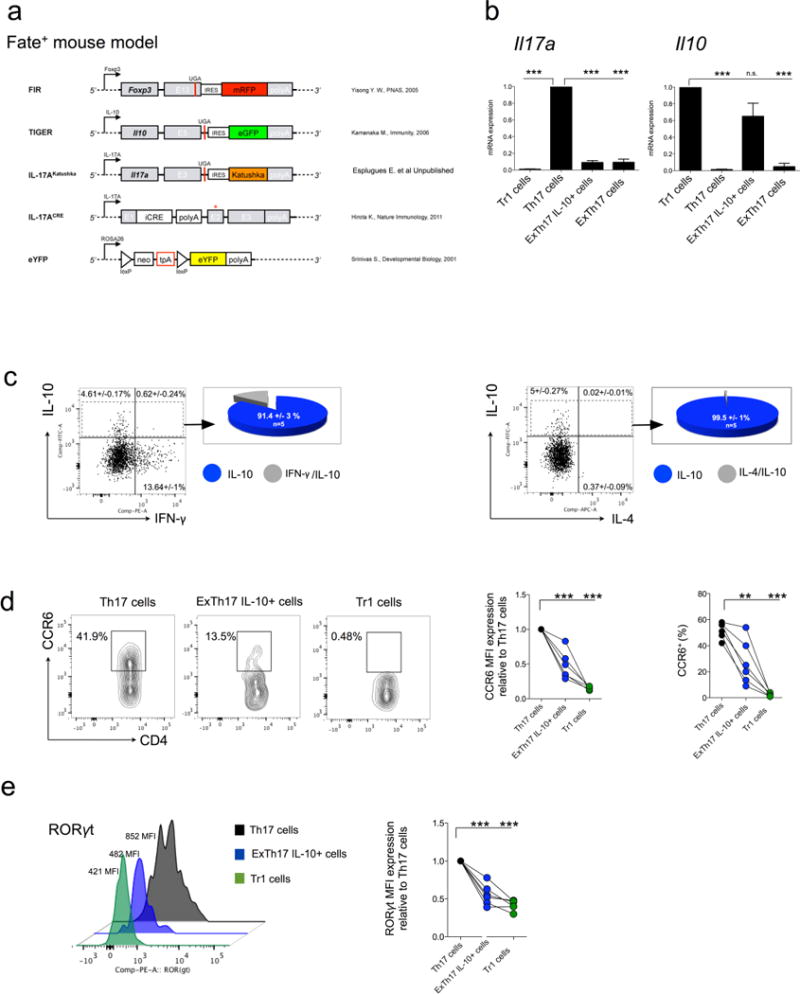

Extended Data Figure 1. Description of Fate+ mice and characterization of exTH17 IL-10eGFP+ cells under steady state condition.

a, Constructs contained in the Fate+ mice. b, During anti-CD3 mAb induced transient inflammation in the S.I., a sufficient number of exTH17 IL-10eGFP+ was generated to test whether Fate+ mice faithfully report IL17A and IL-10 expression. In particular, TR1 (CD4+ IL-17AKatushka− YFP− IL-10eGFP+ Foxp3RFP−), TH17 (CD4+ IL-17AKatushka+ YFP+ IL-10eGFP− Foxp3RFP−), exTH17 IL-10eGFP+ (CD4+ IL-17AKatushka− YFP+ IL-10eGFP+ Foxp3RFP−) and exTH17 (CD4+ IL-17AKatushka− YFP+ IL-10eGFP− Foxp3RFP−) were FACS sorted from the small intestine of anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody treated Fate+ mice and mRNA expression relative to TH17 cells for Il17a and relative to TR1 for Il10 is reported. ExTH17 IL-10eGFP+ express Il10dim/high and Il17alow. Data are cumulative of three independent experiments. In each experiment we pooled cells from at least 7 mice. Mean and s.e.m., ***P ≤ 0.0005 by ANOVA (Tukey’s multiple comparison test). c–e, Under steady state conditions, intestinal lymphocytes were isolated and re-stimulated in vitro for 3 h with PMA/ionomycin for the intracellular staining of IFN-γ and IL-4, while they were freshly analysed for the expression of CCR6 and RORγt. c, Frequencies of IFN-γ and IL-4 among the exTH17 cells is shown. Pie chart reports the frequencies of the indicated cytokine among the exTH17 IL-10eGFP+. One biological replicates out of five is shown. d, e, Frequencies and MFI of CCR6 (d) and MFI of RORγt are reported for TR1 (CD4+ IL-17AKatushka− YFP− IL-10eGFP+), TH17 (CD4+ IL-17AKatushka+ YFP+/− IL-10eGFP−), exTH17 IL-10+ (CD4+ IL-17AKatushka− YFP+ IL-10eGFP+) (e). Each dot represents one biological replicate. Mean and s.e.m., **P ≤ 0.005, ***P ≤ 0.0005 by ANOVA (Dunnett’s multiple comparison test, comparison all columns vs control (TH17 cells)).

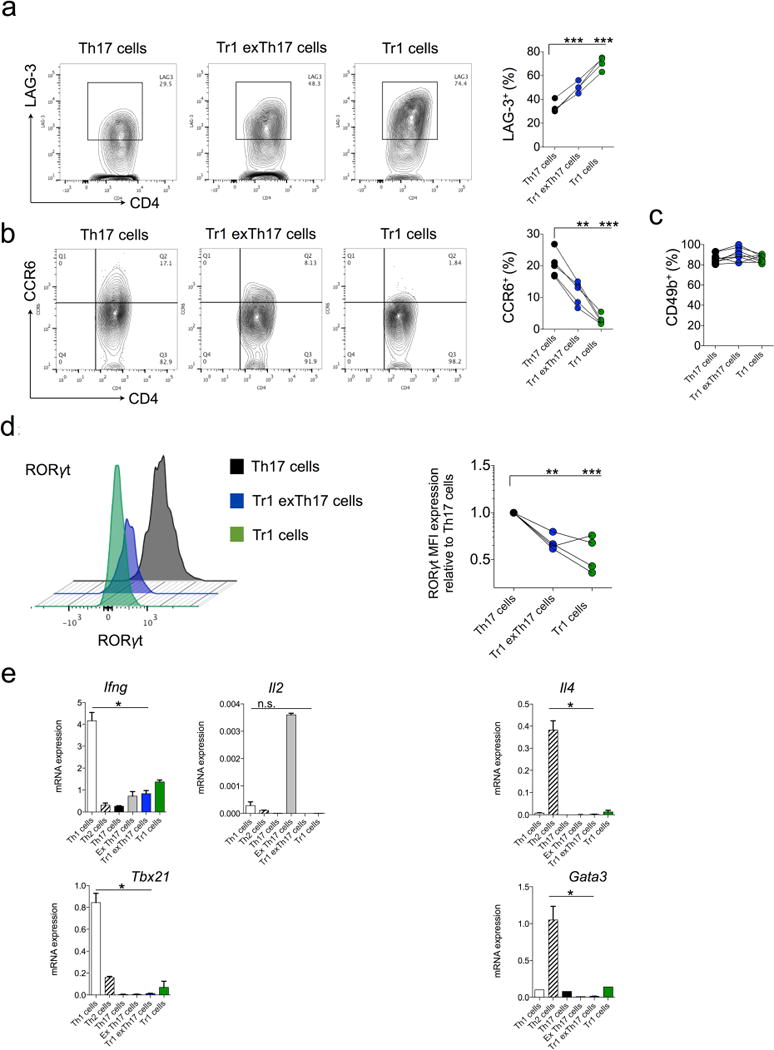

Extended Data Figure 2. Characterization of TR1exTH17 cells.

TR1 (CD4+ IL-17AKatushka− YFP− IL-10eGFP+), TH17 (CD4+ IL-17AKatushka+ YFP+/− IL-10eGFP−), TR1exTH17 (CD4+ IL-17AKatushka− YFP+ IL-10eGFP+) were isolated from the small intestine of anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody treated-Fate+ mice and analysed by FACS. a–d, Frequencies of LAG-3 (a), CCR6 (b), CD49b (c) and MFI of RORγt (d) are reported. Each dot represents one biological replicate. Mean and s.e.m., **P ≤ 0.005, ***P ≤ 0.0005 by ANOVA (Dunnett’s multiple comparison test, Comparison all columns vs control (TH17 cells)). e, TH1 (CD4+ IFN- γKatushka+ Foxp3RFP−), TH2 (CD4+ IL-4GFP+ Foxp3RFP−), TR1 (CD4+ IL-17AKatushk− IL-10eGFP+ Foxp3RFP−), TH17 (CD4+ IL-17AKatushka+ Foxp3RFP−), TR1exTH17 (CD4+ IL-17AKatushka− YFP+ IL-10eGFP+ Foxp3RFP−) and exTH17 (CD4+ IL-17AKatushk− YFP+ IL-10eGFP− Foxp3RFP−) were FACS sorted from the small intestine of anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody treated mice. mRNA expression relative to HPRT of Ifng, Il2, Tbx21, Il4 and Gata3 of the indicated populations is reported. Mean and s.e.m., *P ≤ 0.05, by Mann–Whitney U-test, two tailed.

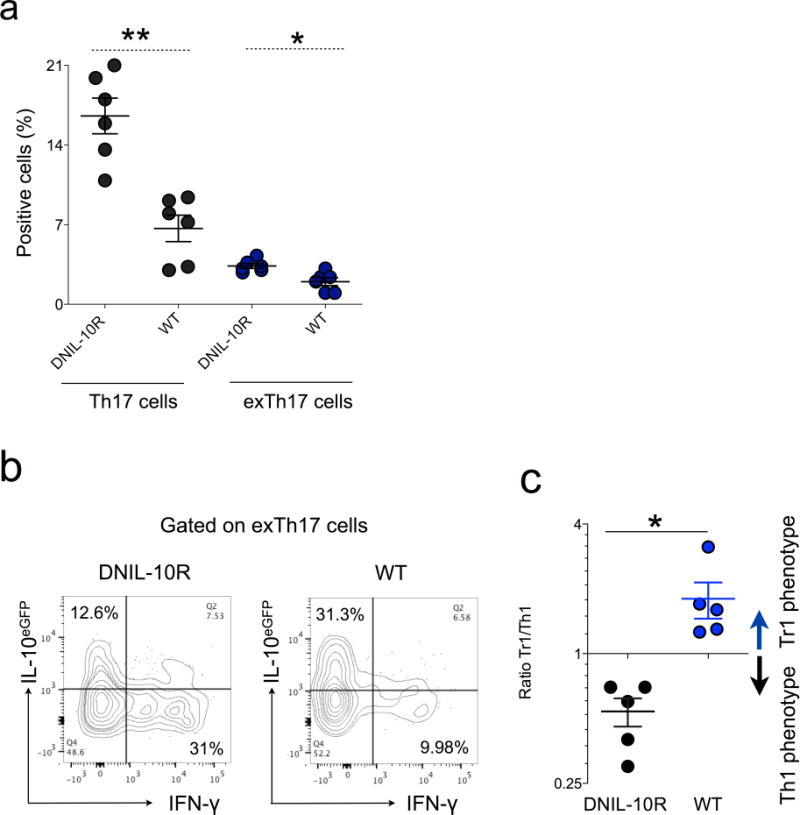

Extended Data Figure 3. TH17 fate in DNIL-10R Fate mice.

Fate (WT) and Fate dominant negative IL-10R (DNIL-10R) were injected with anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody and the fate of small intestinal TH17 cells analysed. a, Frequencies of TH17 and exTH17 gated on CD4+ T cells are reported. b, Representative flow cytometric analysis of the IL-10 and IFN-γ expression in exTH17 cells. c, Ratio between TR1exTH17 (CD4+ IL-17A− YFP+ IL-10eGFP+ IFN-γ−) and Th1exTH17 (CD4+ IL-17A− YFP+ IL-10eGFP− IFN-γ+) in WT and DNIL-10R mice. Mean ± s.e.m. Each dot represents one biological replicate. *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.005 by Mann–Whitney U-test, two tailed.

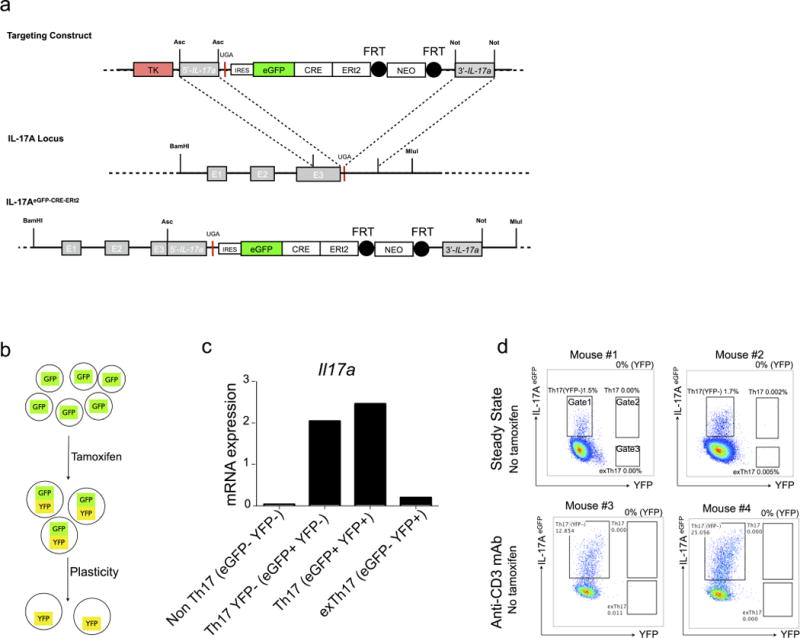

Extended Data Figure 4. Constructs and validation of iFate mice.

a, Targeting strategy and constructs of IL-17AeGFP-CRE-ERT2 mice (iFate). Black circles represent Flp recombinase target (FRT) sites. b, Schematic of TH17 cell development in iFate showing that TH17 cell plasticity can be tested only after tamoxifen treatment. c, iFate mice were injected with tamoxifen and anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody and non TH17 cells (IL-17AGFP−YFP−), TH17 YFP+ cells (IL-17AeGFP+ YFP−), TH17 cells (IL-17AeGFP+ YFP+) and exTH17 cells (IL-17AeGFP− YFP+) were FACS sorted. Il17a mRNA expression in the indicated populations is reported. The mRNA expression is normalized to HPRT. One representative experiment out of two is shown. d, Representative flow cytometric analysis of intestinal TH17 cells under steady state condition or after anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody (aCD3) in the absence of tamoxifen treatment. The efficiency of CRE-mediated recombination after tamoxifen is reported as frequencies of YFP+ cells (YFP) and is the result of the following calculation: YFP+ cells (gate 2 + 3)/(IL-17AeGFP+ YFP− cells (gate 1) + YFP+ cells (gate 2 + 3).

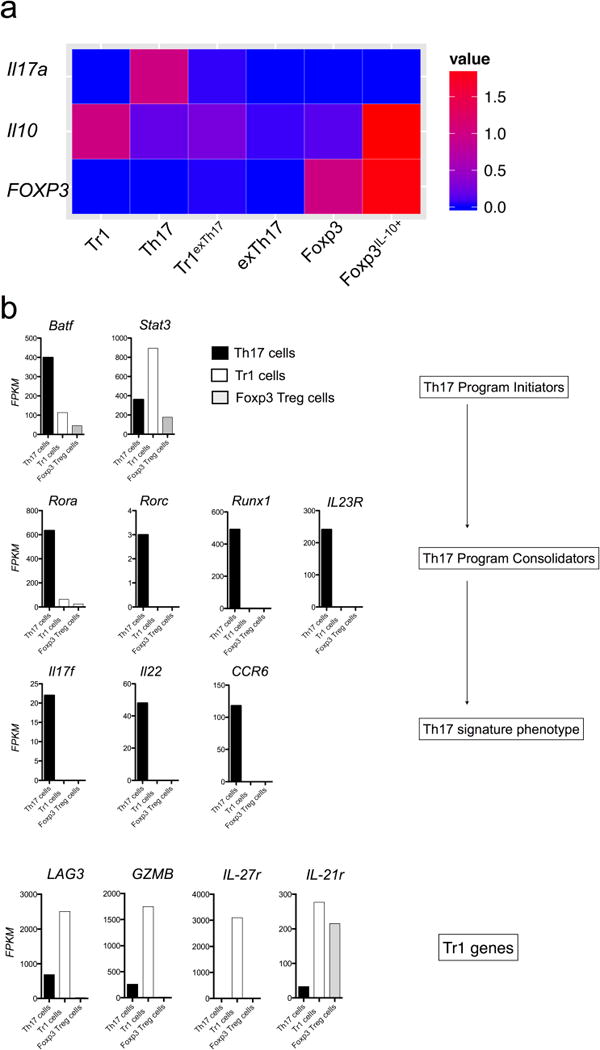

Extended Data Figure 5. Relative expression of Il17a, Il10 and Foxp3 and FPKM values of signature genes of bona fide TH17 and TR1 cells.

a, TR1 (CD4+ IL-17AKatushka− YFP− IL-10eGFP+ Foxp3RFP−) TH17 (CD4+ IL-17AKatushka+ YFP+/− IL-10eGFP+/− Foxp3RFP−), TR1exTH17 (CD4+ IL-17AKatushka− YFP+ IL-10eGFP+ Foxp3RFP−), exTH17 (CD4+ IL-17AKatushka− YFP+ IL-10eGFP− Foxp3RFP−) Foxp3+ TReg (CD4+ IL-17AKatushka− YFP–IL- 10eGFP− Foxp3RFP+) and Foxp3+ TReg IL-10+ (CD4+ IL-17AKatushka− YFP− IL-10eGFP+ Foxp3RFP+) cells were isolated from the small intestine of Fate+ mice after anti-CD3 monoclonal anttibody injections. The transcriptome of these populations was sequenced and the relative FPKM expressions of Il10, Il17a and Foxp3 compared to TR1, TH17 and Foxp3+ TReg cells are reported. b, FPKM values of the indicated populations of the reported genes are shown.

Extended Data Figure 6. TR1exTH17 cell development in EAE and during helminth infection using iFate mice.

a, Schematic of the experiment, showing iFate+ mice immunized with MOG, treated for 3 times with tamoxifen and then injected with anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody 70 and 72 days after MOG immunization. The intestinal lymphocytes were analysed 4 h after the second injection of anti-CD3 monclonal antibody. b, Representative flow cytometric analysis of TH17 and exTH17 (gated on YFP+ cells) and TR1exTH17 cells (gated on exTH17). The YFP+ percentages (YFP) shown on the dot plots report the efficiency of tamoxifen-induced CRE-recombination. Three representative biological replicates out of six are shown. c, Schematic of the experiment, showing iFate mice infected with N. brasiliensis and injected i.p. with tamoxifen at the indicated time points.d, Representative flow cytometric analysis of CD4+ T cells isolated from the lung of iFate mice before (steady state) and after the second infection ± tamoxifen (control N. brasiliensis (no tamoxifen) and N. brasiliensis (+ tamoxifen) respectively)). Cumulative dot plots of 3 biological replicates are shown. One representative experiments out of 3 is shown. The YFP+ percentages (YFP) shown on the dot plots report the efficiency of tamoxifen-induced CRE-recombination. The frequencies within the cumulative dot/density plot report the percentage of TH17 and exTH17 among the YFP+ cells, and the frequency of IL-10+ cells among the exTH17 cells. e, Frequencies of TR1exTH17 cells (gated on exTH17). Each dot represents a biological replicates. Results are cumulative from three independent experiments.

Extended Data Figure 7. Conversion of TH17 cells into TR1 over the course of S. aureus infection using Fate and iFate mice.

a, Fate+ mice were left untreated (control) or injected i.v. with S. aureus (S. aureus). Representative flow cytometric analysis of intestinal TH17 and exTH17 (gated on CD4+ Foxp3RFP−) and TrlexTH17 cells (CD4+ IL-17AKatushka− YFP+ IL-10eGFP+; gated on exTH17) are shown. One representative experiment out of three is shown. b, Frequencies and numbers of the indicated populationin the small intestine of untreated (control) and infected mice (S. aureus) are reported. Results are cumulative from three independent experiments. Mean and s.e.m., **P ≤ 0.005, ***P ≤ 0.0005 by Mann–Whitney U-test, two tailed. c, IFN-γ and IL-10eGFP expression of exTH17 cells. Pie chart reports the frequencies of the indicated cytokine among the TR1exTH17 cells. a–c, One representative biological replicate out of three is shown. One representative experiment out of two is shown. d, Representative flow cytometric analysis of intestinal lymphocytes isolated from iFate mice 4 days after S. aureus infection. One representative biological replicate out of 5 is shown. The YFP+ percentages (YFP) shown on the dot plots report the efficiency of tamoxifen-induced CRE-recombination. e, Frequencies of TR1exTH17 cells (CD4+ IL-17AeGFP− YFP+ IL-10CD90.1+; gated on exTH17) are shown. Results are cumulative from two independent experiments.

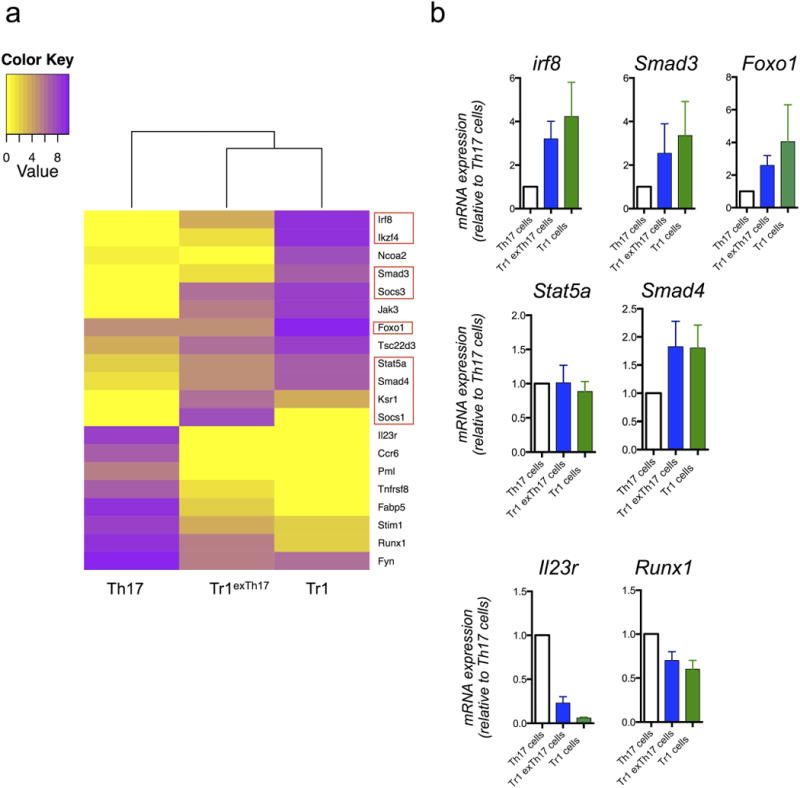

Extended Data Figure 8. Gene expression of TR1, TR1exTH17 and TH17 cells.

a, Heat map of genes selectively expressed in both TR1exTH17 and TR1 compared to TH17 cells. The bioinformatics analysis is based on the genes listed in Supplementary Table 1. Red squares highlight genes linked to TGF-β1 signalling. b, Relative mRNA expression of the indicated genes in TR1, TR1exTH17 and TH17 cells FACS sorted form the intestine of Fate+ mice treated with anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody is shown. Values shown are relative to TH17 cell gene expression. Mean and s.e.m. of biological independent experiments (IRF8 n = 2; SMAD3 n = 4; FOXO1 n = 2; STAT5a n = 3; SMAD4 n = 4) except for IL-23 and Runx1 (n = 2 technical replicates) are shown. In each experiment we pooled intestinal lymphocytes isolated from 7 treated mice before FACS sorting.

Extended Data Figure 9. Characterization of in vitro generated TR1exTH17 cells.

a, IL-1β counteracted TH17 plasticity. IL-17A MFI in TH17 (CD4+ Foxp3RFP− IL-17AKatushka+ YFP+/− IL-10eGFP+/−) differentiated in the presence of TGF-β1, IL-6, IL-23 or IL-1β, IL-6, IL-23. One experiment out of five is shown. Two technical replicates are reported. b, Dose-response effect of TGF-β1onthe inductionofTR1exTH17 cells cultured in the presence of IL-6, IL-23, IL-1β.In the last conditions we added anti-TGF-β1 monoclonal antibody. TGF-β1 was diluted 1:2 starting from the concentration of 4 ng ml−1. One experiment out of five is shown. Two technical replicates are reported. c, In line with the literature29, Smad3 chemical inhibition also favours TH17 cell development. Frequency of TH17 cells cultured in the presence or in the absence Smad3 inhibitor at the indicated different concentrations of TGF-β1 (4–0.25ng ml−1). One experiment out of five is shown. Three technical replicates are reported. d, mRNA expression of Ahr in CD4 T cells cultured in the presence of either TGF-β1, IL-6, IL-23 or IL-1β, IL-6, IL-23. The expression is normalized to HPRT. One experiment out of two is shown. Two technical replicates are reported. e, TR1exTH17 cells were polarized in vitro in the presence of TGF-β1+IL-6+IL-23+FICZ and transferred into Rag1−/− mice ± (p)TH17 cells. Endoscopic colitis score and percentage of initial body weight in the indicated groups are shown. Each dot represents one mouse. Results are cumulative from three independent experiments. Mean and s.e.m.,*P ≤0.05 byMann–Whitney U-test, two-tailed. f, TH17 cells were isolated from the intestine of anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody and then restimulated in vitro in the presence of either anti-TGF-β+IL-6 or IL-6+TGF-β1+FICZ for 5 days. Frequencies of TR1exTH17 cells among total cells (left) and among exTH17 cells (right) are reported. Results are cumulative from three independent experiments. Each dot represents a pool of TH17 cells isolated from five mice treated with anti-CD3. Mean and s.e.m., *P ≤ 0.05, by Mann–Whitney U-test, two tailed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank C. Lieber, P. Musco, E. Hughes-Picard and J. Alderman for expert administrative assistance. J. Stein, L. Evangelisti and C. Hughes for generating the IL-17A IRES-eGFP-CRE-ERT2 constructs, embryonic stem cells and chimaeric mice, respectively. We thank E. Baiocchi for remote key support. LXG is supported by grants K01ES025434 from NIH/BD2K and P20 COBRE GM103457 from NIH/NIGMS. E.E. was supported by the DFG (EXC 257 Neuro Cure and SFB633) and by the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation of America (#311143). N.G. is supported by the Dr. Keith Landesman Memorial Fellowship of the Cancer Research Institute. S.H. is supported by the DFG (HU1714/3) and by Ernst Jung-Stiftung Hamburg and has an endowed Hofschneider-Professorship from the Stiftung Experimentelle Biomedizin. This work was supported, by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, by Cariplo foundation (2013-0937to J.G. and R.A.F.) and by the AbbVie-Yale Collaboration (R.A.F.).

Footnotes

Supplementary Information is available in the online version of the paper.

Author Contributions N.G. designed and performed the experiments, analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. M.C.A.V., A.I., H.X. and L.B. performed the experiments and analysed the data. N.W.P. and M.R.d.Z. optimized the isolation of intestinal cells. P.L-L. provided the expertise and supervised the experiments with N. brasiliensis. T.C. performed bioinformatics analysis and L.X.G. supervised the bioinformatics analysis. C.W. provided the IL-10Thy1.1 mice. X.Z., X.P., R.F. performed and supervised the extraction, amplification and library preparation for RNA sequencing. M.J.C., Y.D. and B.B. assisted with expression profiling and data analysis. M.R.d.Z., P.L.-L., J.G., R.S.P. and E.E. discussed and interpreted the results. N.W.P. discussed and interpreted the results and helped in writing the paper. B.S. provided the IL-17A Cre mice and the protocol for the intracellular staining. R.A.F. and S.H. wrote the manuscript and supervised the project.

Author Information The authors declare no competing financial interests. Readers are welcome to comment on the online versionof the paper.

Online Content Methods, along with any additional Extended Data display items andSource Data, are available in the online version of the paper; references unique to these sections appear only in the online paper.

References

- 1.Hirota K, et al. FatemappingofIL-17-producing T cells in inflammatory responses. Nature Immunol. 2011;12:255–263. doi: 10.1038/ni.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Annunziato F, et al. Phenotypic and functional features of human Th 17 cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1849–1861. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Graf T, Enver T. Forcing cells to change lineages. Nature. 2009;462:587–594. doi: 10.1038/nature08533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Komatsu N, et al. Heterogeneity of natural Foxp3+ T cells: a committed regulatory T-cell lineage and an uncommitted minor population retaining plasticity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:1903–1908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811556106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nylander A, Hafler DA. Multiple sclerosis. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:1180–1188. doi: 10.1172/JCI58649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huber S, Gagliani N, Flavell RA. Life, death, and miracles: TH17 cells in the intestine. Eur J Immunol. 2012;42:2238–2245. doi: 10.1002/eji.201242619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roncarolo MG, Battaglia M. Regulatory T-cell immunotherapy for tolerance to self antigens and alloantigens in humans. Nature Rev Immunol. 2007;7:585–598. doi: 10.1038/nri2138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huber S, et al. TH17 cells express interleukin-10 receptor and are controlled by Foxp3− and Foxp3+ regulatory CD4+ T cells in an interleukin-10-dependent manner. Immunity. 2011;34:554–565. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gagliani N, et al. Coexpression of CD49b and LAG-3 identifies human and mouse T regulatory type 1 cells. Nature Med. 2013;19:739–746. doi: 10.1038/nm.3179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heinemann C, et al. IL-27 and IL-12 oppose pro-inflammatory IL-23 in CD4+ T cells by inducing Blimp1. Nature Commun. 2014;5:3770. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okamura T, et al. TGF-β3-expressing CD4+CD25−LAG3+ regulatory T cells control humoral immune responses. Nature Commun. 2015;6:6329. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Littman DR, Rudensky AY. TH17 and regulatory T cells in mediating and restraining inflammation. Cell. 2010;140:845–858. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Apetoh L, et al. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor interacts with c-Maf to promote the differentiation of type 1 regulatory T cells induced by IL-27. Nature Immunol. 2010;11:854–861. doi: 10.1038/ni.1912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou L, et al. TGF-β-induced Foxp3 inhibits TH17 cell differentiation by antagonizing RORγt function. Nature. 2008;453:236–240. doi: 10.1038/nature06878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beriou G, et al. IL-17-producing human peripheral regulatory T cells retain suppressive function. Blood. 2009;113:4240–4249. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-183251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McGeachy MJ, et al. TGF-β and IL-6 drive the production of IL-17 and IL-10 by T cells and restrain TH-17 cell-mediated pathology. Nature Immunol. 2007;8:1390–1397. doi: 10.1038/ni1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Esplugues E, et al. Control of TH17 cells occurs in the small intestine. Nature. 2011;475:514–518. doi: 10.1038/nature10228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zielinski CE, et al. Pathogen-induced human TH17 cells produce IFN-γ or IL-10 and are regulated by IL-1β. Nature. 2012;484:514–518. doi: 10.1038/nature10957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kamanaka M, et al. Expression of interleukin-10 in intestinal lymphocytes detected by an interleukin-10 reporter knockin tiger mouse. Immunity. 2006;25:941–952. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ciofani M, et al. A validated regulatory network for TH17 cell specification. Cell. 2014;151:289–303. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yosef N, et al. Dynamic regulatory network controlling TH17 cell differentiation. Nature. 2014;496:461–468. doi: 10.1038/nature11981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cua DJ, et al. Interleukin-23 rather than interleukin-12 is the critical cytokine for autoimmune inflammation of the brain. Nature. 2003;421:744–748. doi: 10.1038/nature01355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gause WC, Wynn TA, Allen JE. Type 2 immunity and wound healing: evolutionary refinement of adaptive immunity by helminths. Nature Rev Immunol. 2013;13:607–614. doi: 10.1038/nri3476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen F, et al. An essential role for Th2-type responses in limiting acute tissue damage during experimental helminth infection. Nature Med. 2012;18:260–266. doi: 10.1038/nm.2628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Panzer M, et al. Rapid in vivo conversion of effector T cells into Th2 cells during helminth infection. J Immunol. 2011;188:615–623. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Milner JD, et al. Impaired TH17 cell differentiation in subjects with autosomal dominant hyper-IgE syndrome. Nature. 2008;452:773–776. doi: 10.1038/nature06764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee Y, et al. Induction and molecular signature of pathogenic TH17 cells. Nature Immunol. 2012;13:991–999. doi: 10.1038/ni.2416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ghoreschi K, et al. Generation of pathogenic TH17 cells in the absence of TGF-beta signalling. Nature. 2010;467:967–971. doi: 10.1038/nature09447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martinez GJ, et al. Smad3 differentially regulates the induction of regulatory and inflammatory T cell differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:35283–35286. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C109.078238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stockinger B, Di Meglio P, Gialitakis M, Duarte JH. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor: multitasking in the immune system. Annu Rev Immunol. 2014;32:403–432. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maynard CL, et al. Regulatory T cells expressing interleukin 10 develop from Foxp3+ and Foxp3− precursor cells in the absence of interleukin 10. Nature Immunol. 2007;8:931–941. doi: 10.1038/ni1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jinnin M, Ihn H, Tamaki K. Characterization of SIS3, a novel specific inhibitor of Smad3, and its effect on transforming growth factor-beta1-induced extracellular matrix expression. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69:597–607. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.017483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guo S, et al. Nonstochastic reprogramming from a privileged somatic cell state. Cell. 2014;156:649–662. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pan X, et al. Two methods for full-length RNA sequencing for low quantities of cells and single cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:594–599. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217322109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim D, et al. TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biol. 2013;14:R36. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-4-r36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li H, et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trapnell C, et al. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nature Biotechnol. 2010;28:511–515. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Anders S, Pyl PT, Huber W. HTSeq-a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2014;31:166–169. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.