Abstract

Adolescence is an important stage of human life span, which crucial developmental processes occur. Since peers play a critical role in the psychosocial development of most adolescents, peer education is currently considered as a health promotion strategy in adolescents. Peer education is defined as a system of delivering knowledge that improves social learning and provides psychosocial support. As identifying the outcomes of different educational approaches will be beneficial in choosing the most effective programs for training adolescents, the present article reviewed the impact of the peer education approach on adolescents. In this review, databases such as PubMed, EMBASE, ISI, and Iranian databases, from 1999 to 2013, were searched using a number of keywords. Peer education is an effective tool for promoting healthy behaviors among adolescents. The development of this social process depends on the settings, context, and the values and expectations of the participants. Therefore, designing such programs requires proper preparation, training, supervision, and evaluation.

Keywords: Adolescent, Peers, Peer education

Introduction

Adolescence, an important stage of human life (1), involves crucial developmental processes (2) through which a person goes over to adulthood from childhood (3). These changes may potentially pose pressure on adolescents (4) and cause multidimensional problems necessitating a holistic approach. The majority of adolescents experience some level of emotional, behavioral, and social difficulties (2, 5). On the other hand, adolescents naturally tend to resist any dominant source of authority such as parents and prefer to socialize more with their peers than with their families (4, 6). Research suggests that adolescents are more likely to modify their behaviors and attitudes if they receive health messages from peers who face similar concerns and pressures (7).

A peer is a person whose has equal standing with another as in age, background, social status, and interests. Peers play a critical role in the psychosocial development of most adolescents. They, in fact, provide opportunities for personal relationships, social behaviors, and a sense of belonging. Therefore, peer education is considered as a health promotion strategy in adolescents (8, 9).

Adolescents comprise 20% of the world population and live mostly (85%) in developing communities (10). Moreover, about a quarter (25.1%) of Iran’s population belongs to the age group of 11-14 years old. Unfortunately, more than half of this huge population does not develop healthy life skills. Since peers can effect on each other’s feelings of health, habits, and behaviors (11, 12), various studies have indicated peer education to be more effective than traditional methods (e.g. training provision by teachers) when sensitive subjects like sexual relationships and substance abuse are concerned (12). Studies have also evaluated peer education as a mechanism to promote behavior and attitude modification (13). Peer education has been shown beneficial in improving knowledge and the intention to change behavior in human immunodeficiency virus infection/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) prevention programs among high school students (14). It is, hence, a system of delivering knowledge that promotes social skills (15).

As the important role of peers in quality of life of adolescents warrants further research on peer education, the present study reviewed the peer education approach in adolescents. Knowing the outcomes of different educational approaches will help choose the most effective programs in training adolescents.

Searching Method

In this narrative literature review, databases of PubMed, EMBASE, ISI, and Iranian databases including IranMedex and SID were searched to review the relevant literature. A comprehensive search was performed through PubMed and Google scholar using the combinations of the following keywords: adolescent, peer, peer group, peer education, peer intervention, peer educator. All published data from 1999 to 2013 were then included in this review.

Results and Discussion

Peer education (PE)

Peer education is known as sharing of information and experiences among individuals with something in common (16, 17). It aims to assist young people in developing the knowledge, attitudes, and skills that are necessary for positive behavior modification through the establishment of accessible and inexpensive preventive and psychosocial support. Peer education programs mainly focus on harm reduction information, prevention, and early intervention. The youth have accepted peer education as a preferred strategy to reach unreachable populations such as sex workers and to approach and discuss topics that are insufficiently addressed or considered taboo within other contexts (17–19). Sexual health peer education has been found to significantly increase the use of modern contraceptives and methods to prevent sexually transmitted infections (STIs) (20). A systematic review of interventions to prevent the spread of STIs among young people indicated that peer-led interventions were more accepted, and thus more successful in improving sexual knowledge, than teacher-led interventions (21).

Different methods of peer education have been proposed. The audience can be reached through a variety of interactive strategies such as small group presentations, role plays, or games (15). Formal delivery of peer education in highly structured settings such as class teaching in schools is also possible. Other methods may include informal tutoring in unstructured settings during the course of everyday interactions or individual discussions and counseling. Various methods are adopted based on the intended outcomes of the project (e.g. communicating information, behavior modifi-cation, or development of skills) (22).

Peer educator

A peer educator is a member of a peer group that receives special training and information and tries to sustain positive behavior change among the group members (18, 23). The levels of trust and comfort between the peer educator and his/her peer group will facilitate more open discussions on sensitive topics (24). Peer educators can in fact act as role models of attitude and behavior for their peers (25).

Peer educators should receive adequate training enabling them to understand the purpose of the program, be good listeners, provide encouragement, motivation, and support healthy decisions and behaviors. They should also know other sources of information and counseling so as to refer other peers to appropriate help (5).

More attention to the specific personal characteristics, for instance leadership skills of peer educators is important (26). Identification and selection of peer educators with sufficient confidence, technical competency, compassion, and communication skills who are accepted by other peers are crucial aspects of program success (27). Borgia et al. stated that peer educator selection is a crucial and delicate point in the efficacy of peer education interventions (28).

Peer educators should allow that emotions, feelings, attitudes, and beliefs to be expressed and discussed openly (29). They should also be aware of the usefulness of jokes and humor in establishing relationships with the target group (23). Moreover, initiation of trainings at early ages of adolescence will maintain and consolidate a healthy function. Nevertheless, educational outcomes will widely depend on the relationship with peers (29). Sharing socioeconomic conditions with program participants, peer educators are able to make educational material accessible and credible to participants and hence increase the efficacy of a peer education program (15). A variety of financial, intellectual, and emotional reasons leads to the attractiveness of youth peer education. In addition, the participation of unpaid volunteers makes peer education inexpensive (30).

Theories of Peer Education

As a broadly accepted effective behavioral change strategy, peer education relies on several well-known behavioral theories:

The social learning theory asserts that some individuals function as role models of human behavior due to their aptitude for stimulating behavior changes in other individuals (31).

The theory of reasoned action states that a person’s perception of social norms or beliefs about what people, who are important to the individual, do or think about a particular behavior can affect behavior change (32). In other words, people’s attitudes toward changing a behavior is strongly influenced by their view of its positive or negative consequences and what their peer educators would think about it (7).

The diffusion of innovation theory considers an innovation as new information, an attitude, a belief, or a practice that is perceived as novel by an individual and that can be diffused to a particular group. This theory employs ‘opinion leaders’ to propagate information, influence group norms, and finally act as change agents within the population they belong to (27).

The theory of participatory education has also played a key role in the development of peer education. According to participatory or empo-werment models of education, powerlessness at the community or group level along with socioeconomic conditions caused by the lack of power are major risk factors for poor health (7).

The social inoculation theory postulates that people may adopt unhealthy behaviors under social pressures (33).

Other available theories (the role theory, health belief model, and transtheoretical model) imply partnership, ownership, empowerment, and reinforcement as the critical principles of peer education.

Peer education program

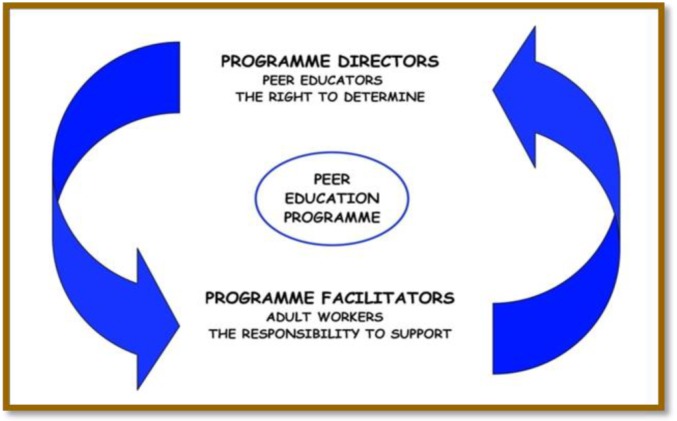

Peer education programs have been used as public health strategies to promote various positive health behaviors such as smoking cessation and vio-lence, substance abuse, and HIV/AIDS prevention. Since such programs seek to produce behavior change in a peer group (the unit of change) by the help of a peer educator or facilitator (the agent of change) (34), they may simultaneously empower the educator and the target group by creating a sense of collective action. In non-hierarchical structure, the management structure of peer education comprises two distinct parallel roles (15), i.e. peer educators and adult support workers. While the first group are the “bosses” and control the direction of the program, the second group (also known as program facilitators) guide and support the peer educators throughout the process (35, 36) (Fig. 1). Peer education programs require careful planning (37), identification and training of peer educators, and follow-up evaluations.

Fig. 1:

Management model of peer education program

Peer educator training, as the most important component of a peer education program, involves:

An introductory meeting to familiarize the peer educators with the concept of peer education and the training needs;

Training the educators with communication, facilitation, research, and evaluation skills;

Providing opportunities for personal development;

Providing access to formal knowledge (13).

The period between the training and the delivery of knowledge to the target group should not be longer than a few weeks (23). After the initial training, peer educators will undoubtedly require continuous supervision and opportunities to give feedback about the program (38).

Peer education strategies engage all five senses and can also improve the participants’ power of thinking and innovation. In fact, the participants will take part in all stages of the program including planning, implementation, and evaluation (12). Studies with more rigorous designs reported peer education programs to increase knowledge and help-seeking about STIs and condom use to prevent HIV infection and to delay first sexual experience (39). Youth peer education programs, whose numbers are growing throughout the world, are extensively used to promote reproductive health. These programs require appropriate technical frameworks, particularly training and supervision, to satisfy the needs of the young and adolescent volunteers (30).

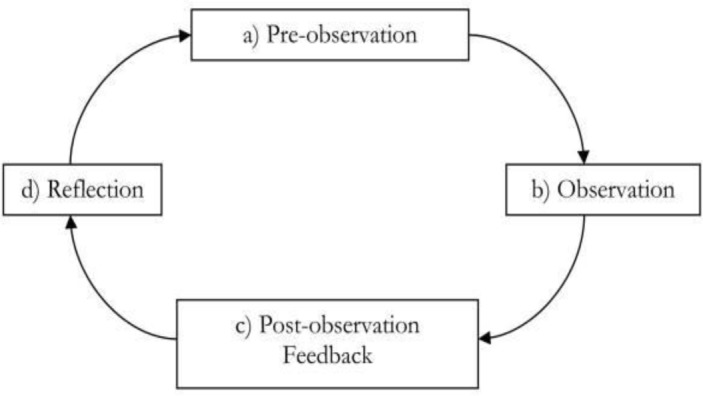

The general approach to peer observation was first described in Bell’s model (Fig. 2) which involved pre-observation meeting, observation, post-observation feedback, and reflection (40).

Fig. 2:

Peer observation process (Bell’s model)

Peer education intervention

Peer education interventions are commonly employed to prevent HIV and other STI (41). By selecting and training peer educators, peer education interventions try to increase the peer group’s knowledge and stimulate behavior change among them. More cost-effective than programs that incorporate highly trained professionals; have been applied in various target populations including the youth, commercial sex workers, and injection drug abusers in developing countries (42, 43). A study in 10 African, Asian, and Latin American countries indicated that peer education interventions can be effective strategies in prevention of risky behaviors and increasing self-esteem and psychosocial aspects (12). According to Merakou and Kourea-Kremastinou, peer education interventions can affect the youth’s behavior about self-protection from HIV infection (25). Similarly, a systematic review suggested peer learning as an efficient method in improving the standing of health science students in clinical placements (44).

Peer education interventions can be used in multiple domains including physical activity, mental health, nutrition, HIV/AIDS and STIs, tobacco and alcohol use, and drug abuse. Visser believed that peer education can postpone the onset of sexual activity and hence play a critical role in the prevention of HIV/AIDS among adolescents (45). Besides, other researchers have identified school-based HIV education as the basis of youth-focused HIV prevention interventions (46). Studies have found the mean score of knowledge regarding breast self-examination to increase in students who receive peer education about breast cancer prevention through the learning of self-examination (29, 47). Rhee et al. showed that a peer-led asthma self-management program can be successfully implemented and absorbed by adolescent learners (48). In addition, the peer education program designed by Karayurt et al. could increase knowledge about breast cancer, enhance the performance of breast self-examination, and improve perceived health beliefs (49). Peer mentorship has also been broadly and successfully used to treat alcohol and substance abuse disorders (50). Finally, some researchers believe that although school-based behavioral interventions which teach sexual health skills can improve the youth’s levels of knowledge and self-efficacy, they may not have great impacts on sexual behavior (51, 52).

Conclusion

We briefly reviewed the impacts of the peer education approach on adolescents. Peer education, which is considered as an effective tool in promoting healthy behaviors among adolescents (53), is a social process affected by the settings, organizational context, key personnel, and the values and expectations of the participants. It requires proper preparation, training, supervision, and evaluation. We found various studies suggesting the success of different peer education programs. We hope that this paper will serve as a starting point in the application of this method in health promotion.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical issues including plagiarism, data falsification, double publication or submission have been completely observed by the authors.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our appreciation to everyone involved in this project. The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Shahhosseini Z, Simbar M, Ramezankhani A, Majd HA (2012). An inventory for assessment of the health needs of Iranian female adolescents. East Mediterr Health J, 18(8):850–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anisi J, Salimi H, Mirzamani M, Reisi F, Niknam m (2007). A Survey Study on Behavioral Problems in Adolescence. Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 1(2):163–170.[Persian] [Google Scholar]

- Alavi Manizheh PK, Khosravi A (2009). Puberty health: knowledge, attitude and practice of the adolescent girls in Tehran, Iran. Payesh, 8(1(29):59–65. [Persian] [Google Scholar]

- Golchin NA, Hamzehgardeshi Z, Fakhri M, Hamzehgardeshi L (2012). The experience of puberty in Iranian adolescent girls: a qualitative content analysis. BMC Public Health, 12:698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2005). Adolescent peer education in formal and non-formal setting. p:1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Akers AY, Gold MA, Bost JE, Adimora AA, Orr DP, Fortenberry JD (2011). Variation in sexual behaviors in a cohort of adolescent females: the role of personal, perceived peer, and perceived family attitudes. J Adolesc Health-, 48(1):87–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wye SQ, Madden A, Poeder F, McGuckin S, Shying K (2006). A framework for peer education by drug-user organizations. Australia, pp:5–39. [Google Scholar]

- Peykari N, Tehrani FR, Malekafzali H, Hashemi Z, Djalalinia Sh (2011). An Experience of Peer Education Model among Medical Science University Students in Iran. Iran J Publ Health, 40(1):57–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochieng BM(2001). Health promotion strategy for adolescents’ sexual behaviour. J Child Health Care, 5(2):77–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahhosseini Z, Simbar M, Ramezankhani A, Alavi Majd H, Moslemizadeh N (2013). The Challenges of Female Adolescents’ Health Needs. Community Ment Health J, May 16. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parvizi S, Ahmadi F (2007). Adolescence health and friendships, a Qualitative study. Feyz,- 10(4):46–51. [Persian] [Google Scholar]

- Noori Sistani M, Merghati K (2010). The impact of peer-based educational approaches on girls’ physicalpractice of pubertal health. Arak Medical University Journal, 12(4):129–135.[Persian] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell C, MacPhail C (2002). Peer education, gender and the development of critical consciousness: participatory HIV prevention by southern African youth. Social Science & Medicine, 55(2), 331–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y, Hong H, Shi R, Ye X, Xu G, Li S, Shen L(2008). Long-term follow-up study on peer-led school-based HIV/AIDS prevention among youths in Shanghai. Int J STD AIDS, 19(12):848–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans DL, Tripp JH (2006). Sex education: the case for primary prevention and peer education. Current Paediatrics, 16(2), 95–99. [Google Scholar]

- Sandhu S, Veinot P, Embuldeniya G, Brooks S, Sale J (2013). Peer-to-peer mentoring for individuals with early inflammatory arthri-tis:feasibility pilot. BMJ Open, 3(3). pii: e002267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peel NM, Warburton J (2009). Using senior volunteers as peer educators: What is the evidence of effectiveness in falls prevention? Australas J Ageing, 28(1):7–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason-Jones AJ, Flisher AJ, Mathews C(2011). Who are the peer educators? HIV prevention in South African schools. Health Educ Res, 26(3):563–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz S, Deutsch C, Makoae M, Michel B, Harding JH, Garzouzie G (2012). Measuring change in vulnerable adolescents: findings from a peer education evaluation in South Africa. SAHARA J, 9(4):242–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speizer IS, Tambashe BO, Tegang SP (2001). An evaluation of the “Entre Nous Jeunes” peereducator program for adolescents in Cameroon. Stud Fam Plann, 32(4):339–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus JV, Sihvonen-Riemenschneider H, Laukamm-Josten U, Wong F, Liljestrand J(2010). Systematic review of interventions to prevent the spread of sexually transmitted infections, including HIV, among young people in Europe. Croat Med J, 51(1):74–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner G, Shepherd J (1999). A method in search of a theory: peer education and health promotion. Health Educ Res, 14(2):235–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strange V, Forrest S, Oakley A (2002). Peer-led sex education--characteristics of peer educators and their perceptions of the impact on them of participation in a peer education programme. Health Educ Res, 17(3):327–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medley A, Kennedy C, O’Reilly K, Sweat M (2009). Effectiveness of peer education interventions for HIV prevention in developing countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Educ Prev, 21(3):181–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merakou K, Kourea-Kremastinou J (2006). Peer education in HIV prevention: an evaluation in schools. Eur J Public Health, 16(2):128–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd J, Kavanagh J, Picot J, Cooper K, Harden A, Barnett-Page E(2010). The effecti-veness and cost-effectiveness of behavioral interventions for the prevention of sexually transmitted infections in young people aged 13–19: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess, 14(7):1–206, iii–iv. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Iryani B, Basaleem H, Al-Sakkaf K, Kok G, van den Borne B(2013). Process evaluation of school-based peer education for HIV prevention among Yemeni adolescents. SAHARA J, 10(1):55–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgia P, Marinacci C, Schifano P, Perucci CA(2005). Is peer education the best approach for HIV prevention in schools? Findings from a randomized controlled trial. J Adolesc Health, 36(6):508–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zangiabadizade M (2012). Comparing The Effect of Peer Education To Health Care Personnel’s on Knowledge of Breast Self-Examination and The Obstacles among Undergraduate Students of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences. Iranian Journal of Medical Education, 12(8):607–615. [Persian] [Google Scholar]

- Svenson G, Burke H (2005). Formative Research on Youth Peer Education Program Productivity and Sustainability. Family health international. FHI Working Paper Series No. WP05–04. [Google Scholar]

- Burke H, Mancuso L(2012). Social cognitive theory, metacognition, and simulation learning in nursing education. J Nurs Educ, 51(10):543–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr MG, Thrush R, Plaut DC(2013). The theory of reasoned action as parallel constraint satisfaction: towards a dynamic computational model of health behavior. PLoS One, 8(5):e62490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banas John A. Rains SA (2010). A Meta-Analysis of Research on Inoculation Theory. Communication Monographs, 77(3):281–311. [Google Scholar]

- Chandan U, Cambanis E, Bhana A, Boyce G, Makoae M, Mukoma W (2008). Evaluation of My Future Is My Choice (MFMC) Peer Education Life Skills Programme in Namibia: Identifying Strengths, Weaknesses, and Areas of Improvement. Windhoek, UNICEF Namibia. [Google Scholar]

- Backett-Milburn K, Wilson S (2000). Understanding peer education: insights from a process evaluation. Health Educ Res, 15(1):85–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellanby AR, Rees JB, Tripp JH (2000). Peer-led and adult-led school health education: a critical review of available comparative research. Health Educ Res, 15(5):533–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers J(2006). Guidance on delivering effective group education. Br J Community Nurs,-11(11):476–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seymour JE, Almack K, Kennedy S, Froggatt K (2013). Peer education for advance care planning: volunteers’ perspectives on training and community engagement activities. Health Expect, 16(1):43–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mash R. Mash RJ (2012). A quasi-experimental evaluation of an HIV prevention programme by peer education in the Anglican Church of the Western Cape, South Africa. BMJ Open, 2(2), 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan PB, Buckle A, Nicky G, Atkinson SH(2012). Peer observation of teaching as a faculty development tool. BMC Med Educ, 12: 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolli MV(2012). Effectiveness of peer education interventions for HIV prevention, adolescentpregnancy prevention and sexual health promotion for young people: a systematic review of European studies. Health Educ Res, 27(5):904–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim CR, Free C (2008). Recent evaluations of the peer-led approach in adolescent sexual health education: a systematic review. Perspect Sex Reprod Health, 40(3):144–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harden A, Oakley A, Oliver S (2001). Peer delivered health promotion for young people: A systematic review of different study designs. Health Education Journal, 60: 339–353. [Google Scholar]

- Secomb J(2008). A systematic review of peer teaching and learning in clinical education. J Clin Nurs, 17(6):703–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visser MJ(2007). HIV/AIDS prevention through peer education and support in secondary schools in South Africa. SAHARA J, 4(3):678–694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denison JA, Tsui S, Bratt J, Torpey K, Weaver MA, Kabaso M(2012). Do peer educators make a difference? An evaluation of a youth-led HIV prevention model in Zambian Schools. Health Educ Res, 27(2):237–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malak AT, Dicle A(2007). Assessing the efficacy of a peer education model in teaching breast self-examination to university students. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev, 8(4):481–484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee H, McQuillan BE, Belyea MJ (2012). Evaluation of a peer-led asthma self-management program and benefits of the program for adolescent peer leaders. Respir Care, 57(12):2082–2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karayurt O, Dicle A, Malak AT (2009). Effects of peer and group education on knowledge, beliefsand breast self-examination practice amonguniversity students in turkey. Turk J Med Sc., 39(1):59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Tracy K, Burton M, Miescher A(2012)-. Mentorship for Alcohol Problems (MAP): a peer to peer modular intervention for outpatients. Alcohol, 47(1):42–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper K, Shepherd J, Picot J, Jones J, Kavanagh J, Harden A(2012). An economic model of school-based behavioral interventions to prevent sexually transmitted infections. Int J Technol Assess Health Care, 28(4):407–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahhosseini Z, Simbar M, Ramezankhani A, Majd HA(2011). Iranian female adolescents reproductive health services needs: A qualitative study. World Applied Sciences Journal, 13(7):1580–1585. [Google Scholar]

- Simbar M, Tehrani F. R, Hashemi Z (2005). Reproductive health knowledge, attitudes and practices of Iranian college students. East Mediterr Health J, 11(5/6):199–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]