Abstract

AIM: To demonstrate that caudate lobectomy is a valid treatment in cases of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) rupture in the caudate lobe based on our experience with the largest case series reported to date.

METHODS: A retrospective study of eight patients presenting with spontaneous rupture and hemorrhage of HCC in the caudate lobe was conducted. Two patients underwent ineffective transarterial embolization preoperatively. Caudate lobectomy was performed in all eight patients. Bilateral approach was taken in seven cases for isolated complete caudate lobectomy. Left-sided approach was employed in one case for isolated partial caudate lobectomy. Transarterial chemoembolization was performed postoperatively in all patients.

RESULTS: Caudate lobectomy was successfully completed in all eight cases. The median time delay from the diagnosis to operation was 5 d (range: 0.25-9). Median operating time was 200 min (range: 120-310) with a median blood loss of 900 mL (range: 300-1500). Five patient remained in long-term follow-up, with one patient becoming lost to follow-up at 3 years and two patients currently alive at 7 and 19 mo. One patient required reoperation due to recurrence. Gamma knife intervention was performed for brain metastasis in another case. Two patients survived for 10 and 84 mo postoperatively, ultimately succumbing to multiple organ metastases.

CONCLUSION: Caudate lobectomy is the salvage choice for HCC rupture in the caudate lobe. Local anatomy and physiologic features of the disease render caudate lobectomy a technically difficult operation. Postponement of surgical intervention is thus recommended while the rupture remains hemodynamically stable until an experienced surgeon becomes available. Prognosis is confounded by numerous factors, but long-term survival can be expected in the majority of cases.

Keywords: Caudate lobectomy, Hepatocellular carcinoma, Emergency, Rupture, Transarterial embolization

Core tip: Management of spontaneous rupture and hemorrhage of hepatocellular carcinoma is seldom reported due to its rareness and severity. This article demonstrates that caudate lobectomy is a valid treatment as well as the salvage choice for management in such cases based on our experience with the largest case series reported to date. Based on limited long-term follow-up data, overall 1-year and 3-year survival rates have been achieved. In addition, delayed surgery is advised over prudent resection until an experienced surgical team becomes available.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection remains a major public health problem with more than 350 million chronic HBV sufferers worldwide[1]. Chronic HBV infection is the cause of approximately one third of all cases of liver cirrhosis and more than three quarters of all hepatocelluar carcinoma (HCC) cases worldwide[2,3]. Longstanding history of hepatitis B infection and liver cirrhosis prior to HCC confirmation comprise the typical pathological process for HCC patients in China.

Spontaneous tumor rupture is one of the most severe complications of HCC. Incidence of rupture is reported at rates varying from 3% to 15% of all HCC cases, with approximately 10% of HCC patients dying of this complication annually in Asia[4]. Spontaneous rupture and hemorrhage of HCC at the caudate lobe is especially rare and catastrophic[5]. Rupture is mainly a consequence of increased tension from tumor progression, central necrosis, malacosis, or liquefaction. Although transarterial embolization (TAE) is the first choice in the treatment algorithm, the outcome is not always satisfactory and hepatectomy cannot be avoided. Management of tumor rupture in the caudate lobe necessitates caudate lobectomy - a technically challenging operation confounded by caudate lobe anatomy and complicated further by intricate vasculature of the main organ[6]. The multitude of branches from both right and left hepatic arteries makes inflow occlusion to the tumor and hemostasis of the caudate lobe equally difficult to achieve. These factors explain the insufficiency and ineffectiveness of TAE, and warrant special considerations for surgical management of these cases.

Caudate lobectomy is the primary salvage treatment for spontaneous HCC rupture in the caudate lobe. Our team has accumulated significant experience with surgical management of the caudate lobe, detailing relevant anatomy and methodology in publication for better global understanding of caudate lobectomy[5]. The cases are sparse, however, leaving few medical centers with necessary exposure. Comprehensive case reporting remains pivotal to systematic validation of surgical treatment. We present our experience with eight cases of spontaneous rupture and hemorrhage of HCC in the caudate lobe, constituting the largest case series reported to date.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A retrospective study of eight patients presenting with spontaneous rupture and hemorrhage of HCC in the caudate lobe was conducted. Patients were evaluated at admission to our center between January 2010 and July 2013 and were managed surgically by caudate lobectomy. Patient demographics and disease profiles are summarized in Table 1. All patients were male with a median age of 41.5 years (range: 33 to 47 years). Previous interventions included left hepatectomy for HCC resection in one patient two years prior to our involvement, and two cases of prior TAE. Seven patients presented Child-Pugh A liver function, with one patient classified as Child-Pugh C. Portal vein thrombus was absent in all eight patients and no other medical co-morbidities were identified. Seven patients were haemodynamically stable on admission and underwent planned hepatectomy. Emergency surgery was performed on admission in one haemodynamically unstable patient with confirmed rupture of the lesser sac and intra-abdominal bleeding. Postoperative pathology confirmed liver cirrhosis and HCC in all eight subjects.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and disease history

| Patient number | Age | Gender | Liver function Child-Pugh classification | Hepatitis | Cirrhosis | Preoperative TAE | Intact lesser sac | Intact liver capsule | Tumor size (cm) | Time delayed for operation (d) |

| 1 | 46 | M | A | B | Y | N | Y | Y | 7 × 8 × 6 | 93 |

| 2 | 33 | M | C | B | Y | N | N | N | 9 × 10 × 9 | 0.25 |

| 3 | 47 | M | A | B | N | N | Y | Y | 5 × 4 × 8 | 1 |

| 4 | 41 | M | A | B | Y | Y | Y | Y | 3 × 3 × 3 | 1 |

| 5 | 42 | M | A | B | Y | Y | Y | N | 10 × 6 × 6 | 5 |

| 6 | 45 | M | A | B | Y | N | Y | Y | 7 × 7 × 6 | 8 |

| 7 | 39 | M | A | B | Y | N | Y | N | 4 × 5 × 6 | 6 |

| 8 | 40 | M | A | B | Y | N | Y | Y | 5 × 6 × 6 | 5 |

Surgical procedure

Surgical repair occurred on average 9 d after symptom onset (range, 6 h to 93 d). Tumor size and location dictated the choice of procedure. Isolated caudate lobectomy was performed in seven cases. Patient 2 underwent partial caudate lobectomy. A reversed L-shaped incision was made in seven cases. A roof incision overlaying the existing incision line was made in the patient with a prior history of hepatectomy.

Procedure details are summarized in Table 2. The liver was mobilized by dissection of hepatic ligaments. The hilum was exposed and hepatoduodenal ligament was encircled with a No. 8 urine catheter in preparation for Pringle’s maneuver. Infrahepatic inferior vena cava (IVC) was exposed by parting overlying retroperitoneum and encircled with an additional urine catheter in preparation for inflow and outflow control (Figure 1). Both controls were applied immediately if the lesser sac was found damaged and active bleeding was confirmed. Dissection was then performed along the anterior surface of the retrohepatic IVC. To facilitate this process, several short hepatic veins draining the caudate lobe were identified, ligated, and divided. Left hepatic lobe was thus mobilized and rotated to the right. With the caudate process exposed, the hepatoduodenal ligament became available for mobilization to the right, revealing the portal triad of the caudate lobe and opening it to transection. The stump was closed with 4-0 prolene suture. Attention was then shifted to short hepatic veins supplying the IVC from the caudate lobe. Both were ligated and divided, marking separation and cauterization of the connection between right and left portions of the liver. Finally, the caudate lobe containing the tumor became open to resection (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Surgical findings and outcomes

| Patient number | Surgical approach | Operating time (min) | Intraoperative blood loss (mL) | Intraoperative blood transfusion (RBC: U; plasma: mL) | Complications | Survival time (mo) |

| 1 | Combined complete | 210 | 1000 | 3.5; 800 | N | 10 |

| 2 | Left partial | 190 | 1500 | 12; 2540 | Wound infection | 19 |

| 3 | Combined complete | 310 | 1200 | 7; 1100 | Wound infection | 361 |

| 4 | Combined complete | 270 | 1000 | 8; 1600 | N | 84 |

| 5 | Combined complete | 150 | 300 | None | N | 7 |

| 6 | Combined complete | 160 | 500 | 2; 200 | N | Lost to follow-up |

| 7 | Combined complete | 290 | 800 | 3; 400 | N | Lost to follow-up |

| 8 | Combined complete | 120 | 350 | None | N | Lost to follow-up |

Patient was lost to follow-up after 3 years. Survival time taken at 36 mo.

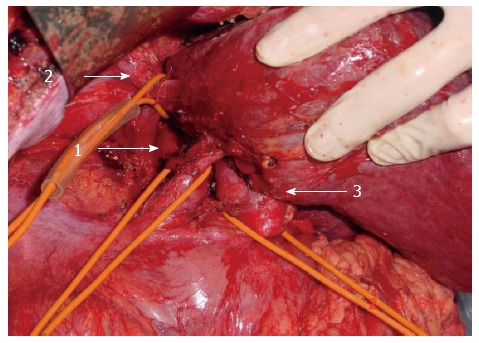

Figure 1.

Inflow and outflow control during combined bilateral approach. Control of infrahepatic inferior vena cava (IVC) (arrow 1), suprahepatic IVC (arrow 2), and hepatoduodenal ligament (arrow 3) during bilateral approach for ruptured hepatocellular carcinoma repair.

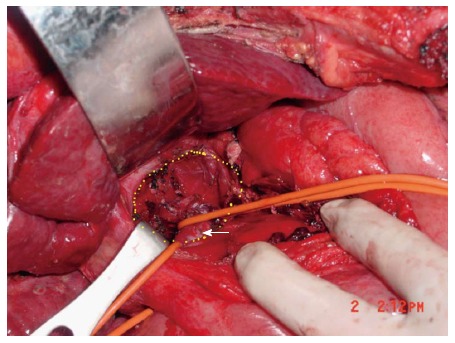

Figure 2.

Rupture site access during left-sided approach. Left-sided approach for ruptured hepatocellular carcinoma repair in Spiegel lobe. Rupture site is shown (white arrow).

Resection was completed under intermittent inflow occlusion with Pringle’s maneuver. Occlusion time limit was 10 min with 2 min reperfusion. The liver parenchyma was transected by means of curettage and aspiration[1] using Peng’s Multifunctional Operative Dissector (PMOD). Figure 3 shows the anatomy of caudate lobe fossa and IVC. The abdomen was irrigated with large volumes of hypoosmotic fluids. One gram of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) was administered intra-abdominally. Two to three abdominal drainages were placed for each patient and subsequently removed 3 to 5 d following confirmation by abdominal ultrasound.

Figure 3.

Anatomy of caudate lobe fossa and inferior vena cava. Caudate lobe fossa (circumscribed by yellow dotted zone) and inferior vena cava (arrow) following removal of caudate lobe.

RESULTS

All eight patients underwent caudate lobectomy between 0.25 and 9 d following diagnosis of HCC rupture. Median operating time was 200 min (range: 120 to 310 min) with a median blood loss of 900 mL (range: 300 to 1500 mL). Two to four RBC units and 400 mL plasma were transfused. Surgical findings are detailed in Table 2. Three cases were characterized by an intact lesser sac in the presence of ruptured hepatic capsule. Resected specimens showed blood clots and caudate lobe tissue resembling that of a compromised lesser sac. Encapsulated clot and liver tissue samples were obtained from the caudate lobe in patients presenting intact hepatic capsules. All patients underwent transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) postoperatively as necessitated by liver function, presence of recurrence on radiologic findings, and serum AFP.

Zero mortality was observed in the early postoperative period (Table 2). Postoperative complications were limited to two incidences of incision infection. Patients 6-8 became unavailable for further postoperative follow-up.

Two patients expired in the course of long-term follow-up. Patient 1 underwent gastric endoscopy 9 mo after caudate lobectomy due to upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Patient 4 was treated conservatively for a month until death due to tumor metastasis. Patient 4 developed multiple organ metastases; brain metastasis was found 4 years after caudate lobectomy and treated with gamma knife therapy, succeeded by a liver recurrence 2 years later and treated with TACE. Patient 3 had a recurrence of HCC on the left liver 8 mo after the operation, receiving RF treatment and ultimately becoming lost to follow-up at 3 years.

Two patients remain in follow-up. Patient 2 was found with a mass in the perigastric region just lateral to the liver at 8 mo postoperatively. The mass was removed by reoperation revealing multiple intraabdominal and abdominal wall metastases. Pathology confirmed metastatic infiltrative HCC. This individual received regular chemotherapy and one TACE treatment. Tumor progression was noted with a growing number of metastatic lymph nodes and portal tumor thrombi. Patient 5 is currently on the 7th mo of postoperative observation, having undergone two TACE treatments during that time. Patient’s recent CT and laboratory findings show no recurrence or metastasis.

DISCUSSION

While HCC occurrence in the caudate lobe is not uncommon[7,8], rupture of the tumor is exceptionally rare. The diagnosis is not difficult, typically characterized by clinical symptoms of sudden-onset upper abdominal pain and imaging revealing hematoma lesion in the lesser sac tracing from the caudate lobe[9]. TAE is recommended as initial treatment. However, its efficacy suffers tremendously from the multitude of venous branches draining the caudate lobe and its proximity to major vessels[5,10].

The caudate lobe of the liver is notable for its anatomic location - easily identified as the segment straddling right and left lobes of the liver[11] and fundamentally difficult to approach surgically. It lies between major vascular structures - the IVC posteriorly, the portal triads inferiorly, and the hepatic venous confluence superiorly[12], - all carrying great volume and posing tremendous danger during the operation. These anatomic and physiologic circumstances render caudate lobectomy a formidable technical challenge, and demand substantial experience to guarantee safe surgical management. As a major regional institution, our center treats numerous cases of HCC rupture and accepts transfers from outside hospitals, affording our team critical exposure to this scarce population. A comprehensive text was published introducing our findings and providing a detailed account of surgical interventions for the hepatic caudate lobe[6]. While the body of experience and the volume of published work detailing tumor rupture management have earned our team expert recognition in this methodology, continued discussion of notable surgical cases will inevitably advance global understanding of caudate lobectomy.

Caudate lobectomy remains the salvage procedure in many cases following TAE failure[5] despite its technical challenges, associated mortality rate of 5.3%-14%[6], and inadvertent lack of surgeons wielding necessary expertise. Since the caudate lobe resides within the lesser sac, post tumor rupture hemorrhage is contained by the lesser sac for as long as it remains intact. The bleeding of ruptured tumors in the caudate lobe thus becomes a secondary problem, not subject to immediate nor aggressive management. This explains the relative haemodynamic stability in seven cases observed at the time of admission to our center. Once the lesser sac does undergo rupture, the emergent bleeding becomes fatal if it is not controlled.

All eight cases in this series were initially haemodynamically stable as confirmed by imaging studies and intraoperative findings due to anatomically benevolent circumstances. One patient presenting for emergent surgical management at transfer to our hospital delivers a comprehensive lesson in management of HCC rupture in the caudate lobe. His clinical course vividly demonstrates the role of proper treatment algorithm, timing, and surgical specialization in the setting of a rare medical catastrophe. This individual initially presented in stable condition to a local hospital with the diagnosis of HCC rupture in the caudate lobe confirmed by CT scan, as attributable to the intact lesser sac. Transfer to another medical center for further management entailed an 8 h transit by train and immediate surgical intervention was necessary at the time of arrival. Unfortunately, the admitting surgeon was not sufficiently experienced in caudate lobectomy and the IVC was accidently injured. Massive hemorrhage resulted in hemorrhagic shock, driving the decision for fast track surgery. A local gauze packing was applied and the patient was temporarily stabilized for transfer to our center. Emergency surgery was performed immediately on admission to our hospital and the patient was successfully repaired. Since the start of the second operation, the patient sustained three instances of cardiac arrest and massive blood loss. Another notable issue in this patient’s course is the prompt recovery of liver function despite preoperative classification as Child-Pugh C. This is largely attributable to low serum protein level caused by sustained hemorrhage.

Optimal timing for caudate lobectomy following HCC rupture in the caudate lobe is subject to critical evaluation. While the lesser sac is intact, conservative treatment is preferred until an experienced surgical team becomes available. However, in emergency conditions instigated by lesser sac rupture, ongoing uncontrolled hemorrhage, and unsuccessful TAE, fast track surgery must be considered even if a specialized hepatobiliary surgeon is unavailable. In this series, every patient undergoing caudate lobectomy at our center had previously undergone surgical intervention that should have been avoided. Nevertheless, secondary fast track surgical strategy proved to be an appropriate and necessary salvage choice.

Four types of lobectomy approaches have been described[13-19]: Left-sided, right-sided, anterior transhepatic, and bilateral, combining left and right-sided approaches. In this series, left-sided approach was taken in the case of ruptured HCC in Spiegel lobe (Figure 2). This patient underwent isolated partial caudate lobectomy. Bilateral approach was elected in seven cases for an isolated complete caudate lobectomy. Anterior transhepatic approach was unnecessary as the tumors were not exceedingly large.

As is ubiquitous to all oncology practices, surgical outcomes correlate closely with several patient-specific variables. Physiological profile of HCC and anatomical complexity of the caudate lobe put this patient population at a particularly high risk of postoperative recurrence. An accurate postoperative prognosis is therefore difficult to deliver, and the disease often warrants continued aggressive treatment following removal of the ruptured tumor.

An intact lesser sac may prevent peritoneal dispersion of ruptured HCC. Among cases treated at our center, the patient whose lesser sac did rupture was found to have a recurrence at the original tumor site 8 mo postoperatively. Analogously, the patient with a prior history of HCC and left hepatectomy presenting to us with a tumor recurrence at the caudate lobe appreciated the shortest survival time of 10 mo. The patient with the longest survival (84 mo) had the smallest caudate lobe tumor in the series, measuring 3 cm3. He underwent six TACE treatments following the first surgery and seven subsequent rounds of radiotherapy for brain metastasis spanning 48 and 80 mo, respectively. Three patients in this series expired in the course of postoperative treatment. Long-term evaluation of the remaining five patients revealed metastasis or recurrence. These patients underwent TACE postoperatively on a minimum of two occasions.

This case series underscores another notable issue: the prevalence of hepatitis B infection and liver cirrhosis in patients prior to HCC confirmation. This is a typical pathological process for HCC patients in China[20-27]. Impaired liver function and possible hypersplenism secondary to cirrhotic liver are evident in these cases. Resultant coagulopathy predisposes to uncontrolled bleeding and multiplies the risks and technical demands of surgery[28]. In this report, all patients presented abnormalities in coagulation function preoperatively. The median blood loss was 900 mL (range: 300-1500 mL) - a relatively large volume. The fact that minimal blood loss closely correlates with better HCC prognosis augments the challenges of surgical involvement in the caudate lobe. However, in the context of varying time from symptom onset to surgical repair, these data are revealed to be less influential to surgical decision making and prognosis.

The experience summarized in this report constitutes the largest case series presented to date. Published findings regarding caudate lobectomy are sparse[6,29] relative to publications depicting other types of hepatectomy[30]. While our group has accumulated significant experience with caudate lobectomy and detailed relevant anatomy and techniques, surgical management of HCC tumor rupture in the caudate lobe remains an isolated domain. Equally obscure, caudate lobe rupture of non-oncologic etiology presents another extreme for the application of caudate lobectomy techniques, as do giant caudate lobe tumors. Clinical considerations and intraoperative recommendations applicable to HCC rupture in the caudate lobe may be extended to the management of these rare and complex cases. For improved understanding and mastery of caudate lobectomy, the efforts to document these cases must be continued.

Caudate lobectomy is the salvage choice for management of spontaneous rupture and hemorrhage of HCC in the caudate lobe. Anatomic and physiologic circumstances render caudate lobectomy a remarkable technical challenge. Delayed surgery is advised over prudent resection until an experienced surgical team becomes available. Hepatitis infection, cirrhosis, and HCC recurrence can be expected to compound the treatment algorithm and postoperative course. Sustained blood loss should be considered as the underlying cause of low serum protein in the evaluation of liver function.

The majority of reviewed cases presenting with HCC rupture in the caudate lobe demonstrated no hemodynamic instability and were managed conservatively until caudate lobectomy was performed by an experienced hepatobiliary surgeon. Based on limited long-term follow-up data, overall 1-year and 3-year survival rates have been achieved.

COMMENTS

Background

Spontaneous rupture and hemorrhage of the hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) at the caudate lobe is especially rare and catastrophic.

Research frontiers

Management of spontaneous rupture and hemorrhage of HCC is seldom reported due to its rareness and severity.

Innovations and breakthroughs

The authors present the experience with eight cases of spontaneous rupture and hemorrhage of the HCC in the caudate lobe, constituting the largest case series reported to date. This experience shows that caudate lobectomy is a valid treatment as well as the salvage choice for management in such cases based on our experience with the largest case series reported to date. Based on limited long-term follow-up data, overall 1-year and 3-year survival rates have been achieved. In addition, delayed surgery is advised over prudent resection until an experienced surgical team becomes available.

Applications

This article provides important issues to consider in the situation of such cases. Among the advices, postponement of surgical intervention while the rupture remains hemodynamically stable until an experienced surgeon becomes available, is the key suggested principle.

Peer-review

The authors present a case series on a rare clinical condition, the management of which cannot be examined in higher-level studies because of low incidence. The approach they suggest is well accepted and is presented with all necessary details. The paper is well written and provides a sound basis for further discussion.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: This work has been improved by the ethics committee of Zhejiang Provincial People’s Hospital.

Informed consent statement: Informed consent was obtained from all the patients at the admission to the hospital.

Conflict-of-interest statement: There is no conflict-of-interest in this clinical study.

Data sharing statement: No additional unpublished data are available.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: January 1, 2015

First decision: January 22, 2015

Article in press: April 28, 2015

P- Reviewer: Chok KSH, Lykoudis PM, Slotta JE S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Liu XM

References

- 1.Lavanchy D. Worldwide epidemiology of HBV infection, disease burden, and vaccine prevention. J Clin Virol. 2005;34 Suppl 1:S1–S3. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6532(05)00384-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perz JF, Armstrong GL, Farrington LA, Hutin YJ, Bell BP. The contributions of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infections to cirrhosis and primary liver cancer worldwide. J Hepatol. 2006;45:529–538. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tanaka M, Katayama F, Kato H, Tanaka H, Wang J, Qiao YL, Inoue M. Hepatitis B and C virus infection and hepatocellular carcinoma in China: a review of epidemiology and control measures. J Epidemiol. 2011;21:401–416. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20100190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vergara V, Muratore A, Bouzari H, Polastri R, Ferrero A, Galatola G, Capussotti L. Spontaneous rupture of hepatocelluar carcinoma: surgical resection and long-term survival. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2000;26:770–772. doi: 10.1053/ejso.2000.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakao A, Matsuda T, Koguchi K, Funabiki S, Mori T, Kobashi K, Takakura N, Isozaki H, Tanaka N. Spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma of the caudate lobe. Anticancer Res. 2000;20:2223–2227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peng SY. Hepatic Caudate Lobe Resection, First Edition. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer-verlag; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ikegami T, Ezaki T, Ishida T, Aimitsu S, Fujihara M, Mori M. Limited hepatic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma in the caudate lobe. World J Surg. 2004;28:697–701. doi: 10.1007/s00268-004-7341-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fujimori M, Takaki H, Nakatsuka A, Uraki J, Yamanaka T, Hasegawa T, Shiraki K, Takei Y, Yamakado K. Combination therapy of chemoembolization and radiofrequency ablation for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma in the caudate lobe. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2012;23:1622–1628. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2012.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iwasaki Y, Tani I, Nakajima Y, Ishikawa T, Umeda S, Kusano S. Lesser sac hematoma as a sign of rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma in the caudate lobe. Eur Radiol. 2001;11:422–426. doi: 10.1007/s003300000628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miyayama S, Yamashiro M, Yoshie Y, Nakashima Y, Ikeno H, Orito N, Yoshida M, Matsui O. Hepatocellular carcinoma in the caudate lobe of the liver: variations of its feeding branches on arteriography. Jpn J Radiol. 2010;28:555–562. doi: 10.1007/s11604-010-0471-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dodds WJ, Erickson SJ, Taylor AJ, Lawson TL, Stewart ET. Caudate lobe of the liver: anatomy, embryology, and pathology. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1990;154:87–93. doi: 10.2214/ajr.154.1.2104732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim HC, Yang DM, Jin W, Park SJ. The various manifestations of ruptured hepatocellular carcinoma: CT imaging findings. Abdom Imaging. 2008;33:633–642. doi: 10.1007/s00261-007-9353-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wahab MA, Fathy O, Elhanafy E, Atif E, Sultan AM, Salah T, Elshoubary M, Anwar N, Sultan A. Caudate lobe resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 2011;58:1904–1908. doi: 10.5754/hge11324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peng SY, Li JT, Mou YP, Liu YB, Wu YL, Fang HQ, Cao LP, Chen L, Cai XJ, Peng CH. Different approaches to caudate lobectomy with “curettage and aspiration” technique using a special instrument PMOD: a report of 76 cases. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:2169–2173. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i10.2169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu P, Qiu BA, Bai G, Bai HW, Xia NX, Yang YX, Zhu JY, An Y, Hu B. Choice of approach for hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma located in the caudate lobe: isolated or combined lobectomy? World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:3904–3909. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i29.3904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu X, Miao X, Zhong D, Dai W, Hu J, Liu G. [Application of liver hanging maneuver in anterior approach for isolated complete liver caudate lobectomy] Zhongnan Daxue Xuebao Yixueban. 2014;39:879–882. doi: 10.11817/j.issn.1672-7347.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tian G, Chen Q, Guo Y, Teng M, Li J. Surgical strategy for isolated caudate lobectomy: experience with 16 cases. HPB Surg. 2014;2014:983684. doi: 10.1155/2014/983684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheung TT, Yuen WK, Poon RT, Chan SC, Fan ST, Lo CM. Improved anterior hepatic transection for isolated hepatocellular carcinoma in the caudate. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2014;13:219–222. doi: 10.1016/s1499-3872(14)60035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamamoto T, Kubo S, Shuto T, Ichikawa T, Ogawa M, Hai S, Sakabe K, Tanaka S, Uenishi T, Ikebe T, et al. Surgical strategy for hepatocellular carcinoma originating in the caudate lobe. Surgery. 2004;135:595–603. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2003.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Y, Zhang Z, Shi J, Jin L, Wang L, Xu D, Wang FS. Risk factors for naturally-occurring early-onset hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with HBV-associated liver cirrhosis in China. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:1205–1212. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lertpipopmetha K, Auewarakul CU. High incidence of hepatitis B infection-associated cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in the Southeast Asian patients with portal vein thrombosis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2011;11:66. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-11-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zeng Z, Guan L, An P, Sun S, O’Brien SJ, Winkler CA. A population-based study to investigate host genetic factors associated with hepatitis B infection and pathogenesis in the Chinese population. BMC Infect Dis. 2008;8:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-8-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shimakawa Y, Yan HJ, Tsuchiya N, Bottomley C, Hall AJ. Association of early age at establishment of chronic hepatitis B infection with persistent viral replication, liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2013;8:e69430. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chau GY. Resection of hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma: evolving strategies and emerging therapies to improve outcome. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:12473–12484. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i35.12473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Han YF, Zhao J, Ma LY, Yin JH, Chang WJ, Zhang HW, Cao GW. Factors predicting occurrence and prognosis of hepatitis-B-virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:4258–4270. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i38.4258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang P, Markowitz GJ, Wang XF. The hepatitis B virus-associated tumor microenvironment in hepatocellular carcinoma. Natl Sci Rev. 2014;1:396–412. doi: 10.1093/nsr/nwu038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nusbaum JD, Smirniotopoulos J, Wright HC, Dash C, Parpia T, Shechtel J, Chang Y, Loffredo C, Shetty K. The Effect of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Surveillance in an Urban Population With Liver Cirrhosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015:Epub ahead of print. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ono F, Hiraga M, Omura N, Sato M, Yamamura A, Obara M, Sato J, Onochi S. Hemothorax caused by spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. World J Surg Oncol. 2012;10:215. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-10-215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang ZG, Lau W, Fu SY, Liu H, Pan ZY, Yang Y, Zhang J, Wu MC, Zhou WP. Anterior hepatic parenchymal transection for complete caudate lobectomy to treat liver cancer situated in or involving the paracaval portion of the caudate lobe. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19:880–886. doi: 10.1007/s11605-015-2793-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Isetani M, Morise Z, Kawabe N, Tomishige H, Nagata H, Kawase J, Arakawa S. Pure laparoscopic hepatectomy as repeat surgery and repeat hepatectomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:961–968. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i3.961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]