Abstract

AIM: To compare the clinical efficacies of two surgical procedures for hemorrhoid rectal prolapse with outlet obstruction-induced constipation.

METHODS: One hundred eight inpatients who underwent surgery for outlet obstructive constipation caused by internal rectal prolapse and circumferential hemorrhoids at the First Affiliated Hospital of Xinjiang Medical University from June 2012 to June 2013 were prospectively included in the study. The patients with rectal prolapse hemorrhoids with outlet obstruction-induced constipation were randomly divided into two groups to undergo either a procedure for prolapse and hemorrhoids (PPH) (n = 54) or conventional surgery (n = 54; control group). Short-term (operative time, postoperative hospital stay, postoperative urinary retention, postoperative perianal edema, and postoperative pain) and long-term (postoperative anal stenosis, postoperative sensory anal incontinence, postoperative recurrence, and postoperative difficulty in defecation) clinical effects were compared between the two groups. The short- and long-term efficacies of the two procedures were determined.

RESULTS: In terms of short-term clinical effects, operative time and postoperative hospital stay were significantly shorter in the PPH group than in the control group (24.36 ± 5.16 min vs 44.27 ± 6.57 min, 2.1 ± 1.4 d vs 3.6 ± 2.3 d, both P < 0.01). The incidence of postoperative urinary retention was higher in the PPH group than in the control group, but the difference was not statistically significant (48.15% vs 37.04%). The incidence of perianal edema was significantly lower in the PPH group (11.11% vs 42.60%, P < 0.05). The visual analogue scale scores at 24 h after surgery, first defecation, and one week after surgery were significantly lower in the PPH group (2.9 ± 0.9 vs 8.3 ± 1.1, 2.0 ± 0.5 vs 6.5 ± 0.8, and 1.7 ± 0.5 vs 5.0 ± 0.7, respectively, all P < 0.01). With regard to long-term clinical effects, the incidence of anal stenosis was lower in the PPH group than in the control group, but the difference was not significant (1.85% vs 5.56%). The incidence of sensory anal incontinence was significantly lower in the PPH group (3.70% vs 12.96%, P < 0.05). The incidences of recurrent internal rectal prolapse and difficulty in defecation were lower in the PPH group than in the control group, but the differences were not significant (11.11% vs 16.67% and 12.96% vs 24.07%, respectively).

CONCLUSION: PPH is superior to the traditional surgery in the management of outlet obstructive constipation caused by internal rectal prolapse with circumferential hemorrhoids.

Keywords: Internal rectal prolapse, Outlet obstructive constipation, Procedure for prolapse and hemorrhoids, Prospective study, Randomized controlled study

Core tip: This study included 54 patients with rectal prolapse hemorrhoids and compared procedure for prolapse and hemorrhoids (PPH) with a traditional operation. The PPH group had a significantly shorter operative time, shorter hospital stay, and lower incidence of postoperative edema perianal, postoperative pain, and sensory incontinence compared to the group receiving traditional surgical treatment. PPH surgery has an obvious effect that can be widely used in clinical treatment.

INTRODUCTION

Constipation is the most common chronic digestive symptom of many causes. It is characterized by decreased defecation frequency, decreased amount of feces, dry feces, and difficulty in defecation. The incidence of constipation is associated with many factors including sex, age, dietary habit, and occupation. Statistics show that the incidence of constipation is as high as 20% in the general population. In recent years, due to the continuous improvement of living standards, the incidence of constipation has been increasing, and thus has become one of the important factors that seriously affect human health. Based on the dynamics of defecation, constipation can be divided into three types: slow transit constipation, outlet obstructive constipation, and mixed type constipation. Conservative treatment is the main therapy for slow transit constipation, and surgery is not advocated. Outlet obstructive constipation is more common in middle-aged and elderly females and often requires management by surgery. Outlet obstructive constipation may be caused by circumferential hemorrhoids, internal rectal prolapse, rectocele and puborectalis muscle syndrome, with internal rectal prolapse and circumferential hemorrhoids being the most common causes. Currently, there are multiple surgical procedures available for the treatment of outlet obstructive constipation caused by internal rectal prolapse with circumferential hemorrhoids, with traditional ligation of prolapsed rectal mucosa and hemorrhoids and procedure for prolapse and hemorrhoids (PPH) being the most commonly used. The present study was conducted to assess whether PPH is superior to the traditional surgery in the management of outlet obstructive constipation caused by internal rectal prolapse with circumferential hemorrhoids.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

One hundred eight inpatients who underwent surgery for outlet obstructive constipation caused by internal rectal prolapse and circumferential hemorrhoids at the First Affiliated Hospital of Xinjiang Medical University from June 2012 to June 2013 were prospectively included in the study. Hemorrhoids were diagnosed by history, digital rectal examination, and anoscopic examination according to the Diagnostic Criteria for Hemorrhoids formulated in 2004 by the Anorectal Surgery Group of Surgery Branch of China Association of Chinese Medicine[1]. Internal rectal prolapse was graded according to the criteria formulated in 1975 at the National Conference of Anorectal Medicine. The patients were divided into two groups using a randomized block design to undergo either PPH (n = 54) or traditional surgery (ligation of prolapsed rectal mucosa and hemorrhoids; n = 54). The PPH group was comprised of 20 men and 34 women, with a mean age of 55.4 ± 8.5 years; the control group was comprised of 23 men and 31 women, with a mean age of 54.1 ± 9.1 years. For the PPH group, the mean disease duration was 11.4 ± 3.7 years; there were 39 cases of grade III hemorrhoids, 15 cases of grade IV hemorrhoids, 24 cases of grade II internal rectal prolapse, and 30 cases of grade III internal rectal prolapse. For the control group, the mean disease duration was 10.2 ± 4.1 years; there were 37 cases of grade III hemorrhoids, 17 cases of grade IV hemorrhoids, 26 cases of grade II internal rectal prolapse, and 28 cases of grade III internal rectal prolapse. Baseline data including age, sex, grade of hemorrhoids, and grade of internal rectal prolapse were not significantly different between the two groups.

Inclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were: (1) grade III or IV hemorrhoids; (2) age 45-65 years; (3) grade II or III internal rectal prolapse diagnosed by defecography; and (4) clinical manifestations including difficulty in defecation, sensation of anorectal obstruction, anal tenesmus or discomfort, prolonged defecation, and the frequent need of manual maneuvers to facilitate defecations.

Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria were: (1) patients with severe anal stenosis or anal incontinence; (2) patients with a previous history of surgery or injection therapy for hemorrhoids; (3) patients with malignant tumors of the colon, rectum, or anal canal; and (4) patients with severe diseases of the heart, brain, liver, kidney, hematologic or endocrine system, or the disabled.

Operative procedures

For PPH, sacral anesthesia was performed and the patients were placed in the right lateral decubitus position. After the surgical area was disinfected with 0.5% iodophor liquid, the anal canal was expanded to insert a circular anal dilator and obturator. The obturator was then removed to make the prolapsed mucosa fall into the canal dilator. Subsequently, a purse-string anoscope was inserted and used to place a circumferential mucosal/submucosal purse-string suture with 2-0 Prolene 3-4 cm above the dentate line in a clockwise manner. A stapler was opened to its maximum extent, and its anvil was advanced across the purse string. The purse string suture was then cinched closed and tied. The stapler was fired and held closed for approximately 20 s to aid in hemostasis. Finally, the stapler was opened and removed. The anoscope was reinserted into the anal canal to evaluate hemostasis. Any small bleeding areas could be managed by oversewing. Perianal skin tags were finally removed.

For ligation of prolapsed rectal mucosa and hemorrhoids, sacral anesthesia was performed and the patient was placed in the lithotomy or lateral decubitus position. After the perineal area, rectum, and anal canal were disinfected with 0.5% iodophor liquid, and the anal canal was expanded to the extent that three fingers could be placed in. After the anus fully relaxed, a di-wing anoscope was inserted to fully expose the prolapsed rectal mucosa. The ligation of the prolapsed rectal mucosa was then performed, followed by the ligation of hemorrhoids. Sufficient skin and mucosal bridges were retained between adjacent hemorrhoids. After careful detection of possible active bleeding points, Vaseline gauze was placed into the anal canal for compression hemostasis. After aseptic dressing was applied, adhesive tape and T-bandage were used for fixation.

Outcome measures

Both short- and long-term outcome measures were evaluated in this study. Short-term outcome measures were arbitrarily defined as those observed within 3 mo after surgery, whereas long-term outcome measures were those observed 6 mo or longer after surgery. Short-term outcome measures included operative time, postoperative hospital stay, postoperative urinary retention, postoperative perianal edema, and postoperative pain, whereas long-term outcome measures included postoperative anal stenosis, postoperative sensory anal incontinence, postoperative recurrence, and postoperative difficulty in defecation.

Postoperative pain evaluation

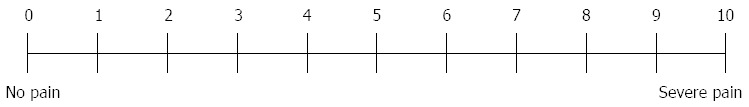

Postoperative pain was evaluated using the visual analogue scale (VAS). The VAS is a 10-cm line with the two ends marked “0” (no pain) and “10” (worst pain) (Figure 1). The patient was asked to place a mark that corresponds to his/her current pain intensity. The mean scores of mild, moderate and severe pain were 2.57 ± 1.04, 5.18 ± 1.41, and 8.41 ± 1.35, respectively.

Figure 1.

Visual analogue scale. Mild pain: 1-3 points; moderate pain: 4-6 points; severe pain: 7-10 points.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 17.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). Numerical data including operative time, postoperative hospital stay, and postoperative pain score are expressed as mean ± SD and were compared using the Student’s t test. Categorical data including the incidences of postoperative urinary retention, perianal edema, anal stenosis, sensory anal incontinence, recurrent internal rectal prolapse and difficulty in defecation were compared using the χ2 test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Short-term efficacy and safety

After surgical treatments, the symptoms improved in patients of both groups. The outcome measures for short-term efficacy and safety are shown in Table 1. The operative time and postoperative hospital stay were significantly shorter in the PPH group than in the control group (both P < 0.01). The incidence of postoperative urinary retention was higher in the PPH group than in the control group, but the difference was not statistically significant. The incidence of perianal edema was significantly lower in the PPH group than in the control group (P < 0.05). The VAS scores at 24 h after surgery, first defecation, and one week after surgery were significantly lower in the PPH group than in the control group (all P < 0.01).

Table 1.

Outcome measures for short-term efficacy and safety

| Outcome measure | PPH group (n = 54) | Control group (n = 54) | χ2 or t value | P value |

| Operative time, min | 24.36 ± 5.16 | 44.27 ± 6.57 | 17.514 | < 0.001 |

| Postoperative hospital stay, d | 2.1 ± 1.4 | 3.6 ± 2.3 | 4.094 | 0.001 |

| Urinary retention, n (%) | 26 (48.15) | 20 (37.04) | 1.363 | 0.243 |

| Perianal edema, n (%) | 12 (11.11) | 23 (42.60) | 5.115 | 0.024 |

| Postoperative VAS score | ||||

| At 24 h | 2.9 ± 0.9 | 8.3 ± 1.1 | 27.923 | < 0.001 |

| At first defecation | 2.0 ± 0.5 | 6.5±0.8 | 35.055 | < 0.001 |

| At one week | 1.7 ± 0.5 | 5.0 ± 0.7 | 28.205 | < 0.001 |

VAS: Visual analogue scale; PPH: Procedure for prolapse and hemorrhoids.

Long-term efficacy and safety

Table 2 shows the outcome measures for short-term efficacy and safety (at one year after surgery). The incidence of anal stenosis was lower in the PPH group than in the control group, but the difference was not significant. The incidences of sensory anal incontinence and anal skin tags (5.56% vs 25.93%) were significantly lower in the PPH group than in the control group (both P < 0.05). The incidence of anal tenesmus was higher in the PPH group than in the control group, but the difference was not significant. The incidence rates of recurrent internal rectal prolapse and difficulty in defecation were lower in the PPH group than in the control group, but the differences were not significant.

Table 2.

Outcome measures for long-term efficacy and safety n (%)

| Outcome measure | PPH group | Control group | χ2 value | P value |

| (n = 54) | (n = 54) | |||

| Anal stenosis | 1 (1.85) | 3 (5.56) | 0.26 | 0.610 |

| Anal tenesmus | 15 (27.78) | 13 (24.07) | 0.193 | 0.661 |

| Sensory anal incontinence | 2 (3.70) | 7 (12.96) | 3.951 | 0.041 |

| Recurrence | 6 (11.11) | 9 (16.67) | 0.697 | 0.404 |

| Difficulty in defecation | 7 (12.96) | 13 (24.07) | 2.209 | 0.137 |

PPH: Procedure for prolapse and hemorrhoids.

DISCUSSION

Constipation is the most common chronic digestive disease[2]. It is characterized by decreased defecation frequency, dry feces, and difficulty in defecation. Over the past decades, the changes in dietary patterns and the impact of mental and social factors have made constipation a disease that seriously affects people’s quality of life. Constipation can lead to digestive system diseases such as colon cancer and hepatic encephalopathy, as well as acute myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular accident, and even death. Therefore, early prevention and reasonable treatment will greatly reduce the potential serious consequences of constipation.

This study shows that compared with the traditional surgery, PPH is associated with less postoperative pain and shorter operative and hospitalization times. There are several possible explanations for this. First, PPH is associated with less trauma and faster recovery[3-9]. Second, PPH is simple and can manage internal rectal prolapse and hemorrhoids simultaneously in one procedure. Finally, PPH is conducted 3-4 cm above the dentate line, and the mucosa above the dentate line is controlled by the plant nerve and is not sensitive to pain. Thus, PPH results in milder postoperative pain. Beattie et al[10] reported that approximately 51% of patients undergoing PPH were completely free from postoperative pain. The advantages of PPH have been verified by many clinical trials. In contrast, the traditional surgery consists of two operative procedures, is relatively complex, and has the disadvantages of more trauma, longer operative time, and slower wound recovery, which lead to prolonged hospital stay. Moreover, the conventional surgery is conducted in the area close to the dentate line and tends to damage the pain-sensitive pudendal nerve, thus resulting in more intense postoperative pain.

The advantages of PPH over the traditional surgery lie not only in the short-term curative effects, but also in the long-term curative effects. The incidences of postoperative anal stenosis, sensory anal incontinence, and recurrence were significantly lower in PPH-treated patients, which is consistent with the results of other studies[11,12]. Ganio et al[13] followed patients receiving either PPH or traditional surgery for 87 mo and found that there was no significant difference in postoperative recurrence between the two groups. During PPH, the mucosa is resected, the anal sphincter is not injured, and the anal cushion and anal transitional zone epithelium are retained. Thus, the intact anal canal is preserved and has good postoperative defecation reflex and fine feeling, and the anal function is not affected. In the conventional surgery, too much skin mucosa is removed and insufficient skin and mucosal bridge is retained, and often results in scar stricture[8,14-22]. Of note, if the anastomotic position is too low in PPH, anal stricture often occurs near the dentate line.

In conclusion, PPH is superior to the traditional surgery in the management of outlet obstructive constipation caused by internal rectal prolapse with circumferential hemorrhoids in terms of both short- and long-term efficacies and safety. PPH is associated with less trauma and postoperative pain, shorter operative time, faster recovery, lower recurrence rate, and fewer postoperative complications[11,12,23-27], representing a better choice for treatment of outlet obstructive constipation caused by internal rectal prolapse with circumferential hemorrhoids.

COMMENTS

Background

Constipation is the most common chronic digestive symptom of many causes. It is characterized by decreased defecation frequency, decreased amount of feces, dry feces, and difficulty in defecation. The incidence of constipation is associated with many factors including sex, age, dietary habit, and occupation. Currently, there are multiple surgical procedures available for the treatment of outlet obstructive constipation caused by internal rectal prolapse with circumferential hemorrhoids, with traditional ligation of prolapsed rectal mucosa and hemorrhoids and procedure for prolapse and hemorrhoids (PPH) being the most commonly used.

Research frontiers

The present study was conducted to assess whether PPH is superior to the traditional surgery in the management of outlet obstructive constipation caused by internal rectal prolapse with circumferential hemorrhoids.

Innovations and breakthroughs

The authors found that PPH is superior to the traditional surgery in the management of outlet obstructive constipation caused by internal rectal prolapse with circumferential hemorrhoids.

Peer-review

This is an interesting manuscript about procedure for prolapse and hemorrhoids and conventional surgery.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: The study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Xinjiang Medical University.

Informed consent statement: All study participants, or their legal guardian, provided informed written consent prior to study enrollment.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare there is no conflict of interest to disclose.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: November 30, 2014

First decision: January 8, 2015

Article in press: March 19, 2015

P- Reviewer: Abdollahi M, Osuga T, Tokunaga Y S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: AmEditor E- Editor: Ma S

References

- 1.Anorectal branch of China association of Chinese medicine. Hemorrhoids, anal rash, anal fissure, rectal prolapse of diagnostic criteria. Zhongguo Gangchang Jibing. 2004;24:42–43. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang Q, He F. Export of surgical treatment for obstructive constipation. Zhongguo Linchuang Yanjiu. 2011;3:101–102. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martinsons A, Narbuts Z, Brunenieks I, Pavars M, Lebedkovs S, Gardovskis J. A comparison of quality of life and postoperative results from combined PPH and conventional haemorrhoidectomy in different cases of haemorrhoidal disease. Colorectal Dis. 2007;9:423–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2006.01169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Senagore AJ, Singer M, Abcarian H, Fleshman J, Corman M, Wexner S, Nivatvongs S. A prospective, randomized, controlled multicenter trial comparing stapled hemorrhoidopexy and Ferguson hemorrhoidectomy: perioperative and one-year results. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:1824–1836. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0694-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hetzer FH, Demartines N, Handschin AE, Clavien PA. Stapled vs excision hemorrhoidectomy: long-term results of a prospective randomized trial. Arch Surg. 2002;137:337–340. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.137.3.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shalaby R, Desoky A. Randomized clinical trial of stapled versus Milligan-Morgan haemorrhoidectomy. Br J Surg. 2001;88:1049–1053. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-1323.2001.01830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mehigan BJ, Monson JR, Hartley JE. Stapling procedure for haemorrhoids versus Milligan-Morgan haemorrhoidectomy: randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2000;355:782–785. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)08362-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rowsell M, Bello M, Hemingway DM. Circumferential mucosectomy (stapled haemorrhoidectomy) versus conventional haemorrhoidectomy: randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2000;355:779–781. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)06122-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tjandra JJ, Chan MK. Systematic review on the procedure for prolapse and hemorrhoids (stapled hemorrhoidopexy) Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:878–892. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0852-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beattie , Lam , Loudon A prospective evaluation of the introduction of circumferential stapled anoplasty in the management of haemorrhoids and mucosal prolapse. Colorectal Dis. 2000;2:137–142. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1318.2000.00125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mattana C, Coco C, Manno A, Verbo A, Rizzo G, Petito L, Sermoneta D. Stapled hemorrhoidopexy and Milligan Morgan hemorrhoidectomy in the cure of fourth-degree hemorrhoids: long-term evaluation and clinical results. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:1770–1775. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-0294-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giordano P, Gravante G, Sorge R, Ovens L, Nastro P. Long-term outcomes of stapled hemorrhoidopexy vs conventional hemorrhoidectomy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Surg. 2009;144:266–272. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2008.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ganio E, Altomare DF, Milito G, Gabrielli F, Canuti S. Long-term outcome of a multicentre randomized clinical trial of stapled haemorrhoidopexy versus Milligan-Morgan haemorrhoidectomy. Br J Surg. 2007;94:1033–1037. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.You SY, Kim SH, Chung CS, Lee DK. Open vs. closed hemorrhoidectomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:108–113. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0794-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arnaud JP, Pessaux P, Huten N, De Manzini N, Tuech JJ, Laurent B, Simone M. Treatment of hemorrhoids with circular stapler, a new alternative to conventional methods: a prospective study of 140 patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;193:161–165. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(01)00973-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Bichere A, Khalil K, Sellu D. Stapled haemorrhoidectomy: pain or gain (Br J Surg 2001; 88: 1-3) Br J Surg. 2001;88:1418–1419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lorenzo-Rivero S. Hemorrhoids: diagnosis and current management. Am Surg. 2009;75:635–642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hosseini SV, Sharifi K, Ahmadfard A, Mosallaei M, Pourahmad S, Bolandparvaz S. Role of internal sphincterotomy in the treatment of hemorrhoids: a randomized clinical trial. Arch Iran Med. 2007;10:504–508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mathai Bcong V. Randomized trial of lateral internal sphincterotomy with hemorrhoidectomy. BJS. 1996;8:380–382. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800830327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khubchandani IT. Internal sphincterotomy with hemorrhoidectomy does not relieve pain: a prospective, randomized study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:1452–1457. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6450-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang NJ. China anorectal epidemiology. Version 1. Ji Nan: Shandong science and technology press; 1996. pp. 620–707. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu M, Shi GY, Wang GQ, Wu Y, Liu Y, Wen H. Milligan-Morgan hemorrhoidectomy with anal cushion suspension and partial internal sphincter resection for circumferential mixed hemorrhoids. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:5011–5015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i30.5011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheetham MJ, Cohen CR, Kamm MA, Phillips RK. A randomized, controlled trial of diathermy hemorrhoidectomy vs. stapled hemorrhoidectomy in an intended day-care setting with longer-term follow-up. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:491–497. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6588-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raahave D, Jepsen LV, Pedersen IK. Primary and repeated stapled hemorrhoidopexy for prolapsing hemorrhoids: follow-up to five years. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:334–341. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-9102-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burch J. Stapled hemorrhoidopexy for the treatment of hemorrhoids: a systematic review. J Burch. :1463–1318. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martellucci J, Papi F, Tanzini G. Double rectal perforation after stapled haemorrhoidectomy. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2009;24:1113–1114. doi: 10.1007/s00384-009-0665-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laughlan K, Jayne DG, Jackson D, Rupprecht F, Ribaric G. Stapled haemorrhoidopexy compared to Milligan-Morgan and Ferguson haemorrhoidectomy: a systematic review. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2009;24:335–344. doi: 10.1007/s00384-008-0611-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]