Abstract

Disruption of WNT/β-catenin signaling causes muscle developmental defects. However, it has been unclear how WNT/β-catenin signaling regulates each step of myogenesis. The in vitro culture of primary myoblasts and C2C12 cells (a myoblast cell line) has the ability to differentiate into myofibers in culture with differentiation inducers. These in vitro systems are useful to investigate each step of muscle development, ranging from cell proliferation to homeostasis, under the control of experimental conditions. Our recent study shows that WNT/β-catenin signaling can regulate myogenesis in a temporal specific manner by controlling the gene expression of cyclin A2 (Ccna2) and cell division cycle 25C (Cdc25c) during myoblast proliferation and fermitin family homolog 2 (Fermt2) during myoblast fusion and differentiation, respectively. In the well-differentiated myofibers, WNT/β-catenin signaling plays a role in the maintenance of their structure through a cadherin/β-catenin/actin complex formation, which is important for connecting a myofiber’s cytoskeleton to the surrounding extracellular matrix. Thus, our recent study coupled with previous findings indicates that WNT/β-catenin signaling regulates myogenesis in a variety of ways, and any failure of these steps of myogenesis causes muscle developmental defects.

Keywords: WNT signaling, cell cycle, myoblast fusion, muscle homeostasis

Muscle development

Skeletal muscle has extensive metabolic and functional plasticity as well as a robust regenerative capacity. The process of skeletal muscle formation, beginning with muscle progenitor cell activation and ending with myofiber formation, is complex and highly regulated in both development and regeneration [1]. These developmental and regenerative processes are affected by a variety of muscle disorders and atrophy [2,3]. Muscle precursor cells (aka satellite cells in the adult) are the major source of myoblasts for the growth of skeletal muscles [3]. During development and regeneration muscle precursor cells proliferate, at which stage they are referred to as myoblasts, and subsequently differentiate into myofibers [3]. Among skeletal muscles, muscles in the tongue are the most developed muscles at birth for the purpose of suckling, compared with the other craniofacial and trunk muscles [4,5]. There are many lines of evidence for differences between craniofacial and trunk skeletal muscles. For example, the origin of myoblasts and satellite cells, and fibroblasts in the craniofacial region is occipital somites derived from paraxial mesoderm, and cranial neural crest (CNC) cells, respectively. In contrast, the origin of myoblasts and satellite cells, and fibroblasts in the trunk region is somites derived from paraxial mesoderm, and lateral plate mesoderm, respectively [6].

Embryonic myogenesis (aka primary myogenesis) is necessary to establish the basic muscle pattern at embryonic day (E) E11-E14 in mice. The following fetal myogenesis (aka secondary myogenesis) is characterized by growth and maturation of each muscle anlagen and by the onset of innervation at E14.5-E17.5 in mice [7]. PAX3 (paired box 3, a transcription factor) and PAX7 (paired box 7, a paralogue of Pax3) are critical for myogenic potential, survival, and proliferation of muscle progenitor cells, but differentially contribute to myogenic lineages in the craniofacial and trunk regions [8]. PAX3 is required for myogenic specification upstream of myogenic differentiation 1 (MYOD1; aka MEF3) and myogenic factor 5 (MYF5), somite segmentation, dermomyotome formation, and limb musculature development. Interestingly, mice lacking Pax3 and Myf5 fail to develop skeletal muscle in the trunk and limb, although craniofacial muscles form normally [9]. Pax7 is crucial for the specification and survival of muscle satellite cells in adults [10]. Mice with ablation of Pax7 (Pax7−/− mice) exhibit compromised myogenesis and regeneration in adults, but fetal myogenesis is not affected in Pax7−/− mice [7]. In Pax3−/−;Pax7−/− double knockout mice, the early embryonic muscle of the myotome forms, but all subsequent steps of skeletal muscle formation are compromised by a failure of cell survival or cell fate determination of Pax3+ or Pax7+ expressing cells. These studies indicate that PAX3 is essential for embryonic myogenesis and PAX7 is crucial for adult myogenesis in growth and regeneration; however, both PAX3 and PAX7 share redundant functions during fetal myogenesis. Taken together, the source of muscle supporting cells is different between cranial and trunk muscles, and the contribution and distribution of PAX3+ progenitor cells are different between cranial and trunk muscles. These findings suggest that the molecular mechanism of craniofacial muscle development likely differs from that of trunk and limb muscles.

After myogenic specification, the determination and terminal differentiation of muscle cells are regulated by myogenic regulatory factors (MRFs), which are basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factors. MRFs consist of MYF5, muscle-specific regulatory factor 4 (MRF4; aka MYF6), MYOD1, and myogenin (MYOG; aka MYF4) [11]. In parallel, muscle cells (myoblasts, myotubes and myofibers) express myosin heavy chain (MyHC), which is the actin motor protein. The proper MyHC isoform is crucial for specialized muscle function and myofibril stability [12].

WNT/β-catenin signaling

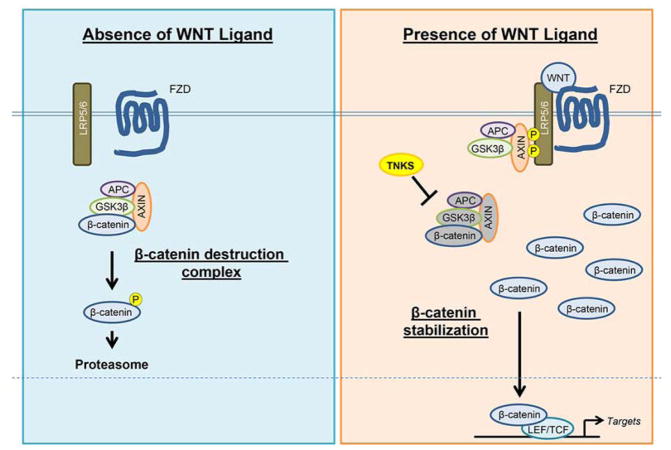

The WNT family consists of 21 secreted glycoprotein ligands that are essential to activate canonical (β-catenin-dependent) and/or non-canonical (β-catenin-independent) pathways in various physiological and pathological conditions [13]. Without WNT ligands, β-catenin is incorporated into a destruction complex containing AXIN, adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) and the serine-threonine kinase glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3β). The destruction complex phosphorylates β-catenin and leads it to be degraded by the ubiquitin-proteasome system [13]. With binding of WNT ligands to a frizzled receptor (FZD) and the low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5/6 (LRP5/6), the destruction complex is inactivated, and β-catenin can be stabilized and translocate into the nucleus [13]. Increased nuclear β-catenin interacts with transcriptional co-activators, such as members of the T-cell factor/Lymphocyte-enhancement factor-1 (TCF/LEF-1) family, and it regulates transcription of target genes [14] (Figure 1). In addition, cytoplasmic β-catenin is involved in cell-cell interactions in combination with cadherin and actin [15]. In chick embryos WNT promotes trunk myogenesis, but blocks myogenesis in the branchial arches [16]. Thus, β-catenin has multiple functions in regulating gene expression and cytoskeletal complex formation; however, the molecular mechanism of WNT/β-catenin signaling during muscle development is still largely unknown.

Figure 1.

WNT/β-catenin signaling pathway. In the absence of WNT ligands, β-catenin is incorporated into a destruction complex containing AXIN, adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) and the serine-threonine kinase glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3β). The destruction complex phosphorylates β-catenin and leads it to be degraded by the proteasome. In the presence of WNT ligands, WNT ligands bind to a Frizzled receptor (FZD) and the low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5/6 (LRP5/6). The destruction complex is inactivated, and then β-catenin can be stabilized and translocate into the nucleus. Increased nuclear β-catenin interacts with transcriptional co-activators such as members of the T-cell factor/Lymphocyte-enhancement factor-1 (TCF/LEF-1) family and regulates transcription of target genes.

Role of WNT/β-catenin signaling in early muscle specification and myoblast proliferation

Mice with deficiency of WNT/β-catenin signaling (Ctnnb1−/− mice) are embryonic lethal by E8.5 with increased cell death [17]. During axial myogenesis, WNT/β-catenin signaling is crucial for dermomyotome and myotome formation [2,18–20]. WNT ligands can positively regulate the number of dermomyotomal Pax3 and Pax7 expressing (Pax3+/Pax7+) progenitors [21–23]. Mice with conditional depletion of β-catenin in muscle precursor Pax7+ cell lineage (Pax7-Cre;Ctnnb1Δ/fl2-6 mice) show reduced formation of slow myofibers during fetal myogenesis [2]. Mice with constitutively activated β-catenin in Pax7+ lineage (Ctnnb1 Δex3;Pax7-Cre mice) exhibit reduced muscle fiber size, excessive nerve defasciculation and branching, and increased number of motor axon at E18.5, resulting in neonatal lethality [2,24]. Thus, the studies of both loss-of-function and gain-of-function of β-catenin indicate that precise amounts of WNT/β-catenin signaling activity is important for myogenesis of Pax7+ progenitor cells.

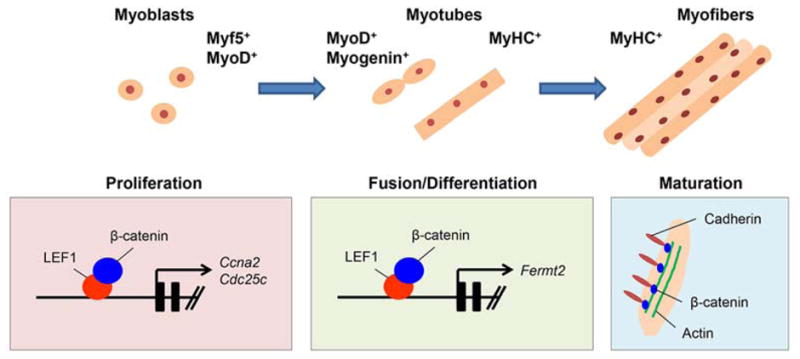

Furthermore, WNT ligands can induce Myf5 and Myod1 expression in vitro [25–28]. WNT ligands regulate both the specification of skeletal myoblasts in the paraxial mesoderm and the induction of location-specific expression of MRFs that govern the determination and terminal differentiation of muscle cells [29]. Our recent study shows that during myoblast proliferation, gene expression of Ccna2 and Cdc25c is specifically downregulated by the inhibition of WNT/β-catenin signaling in both C2C12 cells and primary mouse myoblasts isolated from the tongue and the hind limb muscle [30] (Figure 2). Importantly, WNT/β-catenin activation also induces satellite cell proliferation during skeletal muscle regeneration [31]. Furthermore, treatment with secreted frizzled-related protein 3 (sFRP3), a soluble WNT antagonist, reduces skeletal myogenesis in a dose-dependent fashion in mouse embryos [32]. Altogether, WNT/β-catenin signaling plays a crucial role in myogenic proliferation in both development and regeneration.

Figure 2.

Model of WNT/β-catenin signaling during myogenesis. The schematic diagram depicts our model of the mechanism of WNT/β-catenin signaling pathway during myogenesis. WNT/β-catenin signaling regulates gene expression of Ccna2 and Cdc25c in the cell proliferation stage. WNT/β-catenin signaling regulates gene expression of Fermt2 in the differentiation stage. Beta-catenin forms a complex with cadherin and actin to elongate the myofiber. Disruption of the complex formation results in disorganized myofiber morphology.

Role of WNT/β-catenin signaling in myoblast fusion

Pharmacological activations of WNT/β-catenin signaling can facilitate the differentiation of satellite cells and myoblasts [33–35]. During myoblast fusion, the cell signaling pathway is tightly regulated and controls downstream target molecules involved in membrane fusion and cytoskeletal remodeling [36]. Members of the R-spondin (RSPO) family of secreted cysteine-rich proteins (RSPO1, -2, -3, and -4) and their cognate receptors, members of leucine-rich repeat-containing G protein-coupled receptors 4, 5, and 6 (LGR4/5/6), have emerged as new regulatory components of the WNT signaling pathway [36]. Interestingly, RSPOs activate WNT/β-catenin signaling at the receptor level and promote myogenic differentiation and hypertrophic myotube formation in C2C12 cells through gene expression of the TGFβ antagonist Follistatin (Fst) in C2C12 cells, primary myoblasts from the hind limb muscle, and mouse embryos [37,38]. This suggests that cell signaling network of WNT/β-catenin and TGFβ may be crucial for myogenic differentiation and fusion.

The destruction complex containing AXIN, APC, and GSK3β can regulate the stability of β-catenin and the following WNT/β-catenin signaling activity. In the absence of WNT ligands, GSK3β is activated (phosphorylated) and can phosphorylate β-catenin for ubiquitination and degradation by the proteasome. WNT-mediated GSK3β inactivation by WNT3A or LiCl (lithium chloride; pharmacological WNT/β-catenin signaling inducer) promotes myoblast fusion during muscle differentiation in C2C12 cells [39]. Furthermore, treatment with insulin and a specific inhibitor of GSK3β or WNT/β-catenin signaling activator LiCl leads to enhanced differentiation of C2 myoblasts [35]. These studies indicate that WNT/β-catenin signaling can regulate myoblast differentiation, including fusion of myoblasts.

It is important to identify specific cell signaling cascades and molecules for the fusion of myoblasts. Our recent study shows that gene expression of Fermt2 is regulated by WNT/β-catenin signaling during myogenic differentiation and fusion [30]. RNAi knockdown of Fermt2 in C2C12 cells results in a failure of early myoblast differentiation and/or myoblast fusion [30,40]. These findings indicate that WNT/β-catenin-mediated Fermt2 expression is crucial for myogenic differentiation, including myoblast fusion (Figure 2). This is also supported by the fact that mice with disruption of Fermt2 exhibit early embryonic lethality with musculature developmental defects [41].

Role of WNT/β-catenin signaling in muscle homeostasis

Muscle homeostasis includes maintenance of the number and shape of muscle fibers and the metabolic function and movement. β-catenin is involved in both transcriptional regulation and cell-cell adhesion (aka adherens junction formation) through the formation of cadherin/β-catenin/actin complex. Our recent study shows that a blockade of WNT/β-catenin signaling results in disrupted cell adhesion via loss of cadherin/β-catenin/actin complex formation during muscle maturation/maintenance [30] (Figure 2). The extracellular region of cadherin binds to the extracellular molecules in a Ca2+-dependent manner. Through extracellular interactions, opposing cadherin dimers can integrate the actin cytoskeletons. Stabilization of intracellular adhesion requires the cytoplasmic domain of cadherin, which binds to β-catenin and can be an anchor for a number of cytoskeletal proteins. Thus, β-catenin co-localizes with cadherin in membranes and plays dual roles in WNT/β-catenin signaling and in cadherin-mediated cell adhesion [42,43].

Cadherin family molecules exhibit distinctly regulated tissue distribution and control morphogenesis. Skeletal muscle cells express both N-cadherin (encoded by Cdh2) and M-cadherin (encoded by Cdh15) throughout myogenesis, from progenitors to myofibers, in both development and regeneration [44,45]. Mice with deletion of Cdh2 or Cdh15 (Cdh2−/− or Cdh15−/− mice) exhibit normal myogenesis; therefore, N- and M-cadherins may be functionally redundant. A future study of Cdh2−/−;Cdh15−/− double knockout mice will address this question.

The actin family is categorized into six unique isoforms. Based on their predominant tissue-specific location, actins are categorized into four muscle-specific isoforms (α-skeletal, α-cardiac, α-smooth, and γ-smooth) and two ubiquitously expressed isoforms (β-cytoplasmic and γ-cytoplasmic) [46]. Mice with deficiency of α-skeletal actin (Acta1−/− mice) are indistinguishable from their littermates at birth but die in the early neonatal period (postnatal day 1 to 9) with skeletal muscle defects including reduced muscle strength and growth deficits [47]. This is because most muscles develop postnatally, although tongue muscles are well differentiated in newborns. Therefore, this suggests that the actin complex in the tongue plays a crucial role in muscle homeostasis, but not proliferation and differentiation. However, the actin complex in other muscles may be important for differentiation and maturation.

Altered WNT/β-catenin signaling is implicated in multiple malformations and syndromes including muscle disorders (ex. oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy, facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy, Duchenne muscular dystrophy) in humans [48–51].

Conclusions

WNT/β-catenin signaling plays important roles in muscle development and homeostasis by regulating gene expression of cell cycle regulators and complex formation of cadherin/β-catenin/actin, respectively. This indicates that WNT/β-catenin signaling has unique target molecules in each stage of development. Thus, the in vitro studies with small molecules and genetic manipulation are very useful in determining the step-specific molecular mechanisms during muscle development. Our recent findings on the mechanisms of temporal specific action of WNT/β-catenin signaling may offer several intriguing possibilities into the potential for therapeutic interventions. Genetic approaches in vivo will further validate the functions of target molecules identified in the in vitro studies.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, NIH (DE024759 to J.I.) and faculty start-up funds from the UT Houston School of Dentistry (to J.I).

Abbreviations

- APC

adenomatous polyposis coli

- ChIP

chromatin immunoprecipitation

- FZD

Frizzled receptor

- GSK3β

serine-threonine kinase glycogen synthase kinase-3

- H&E

Hematoxylin and Eosin

- IP

immunoprecipitation

- LEF-1

Lymphocyte-enhancement factor-1

- LRP5/6

low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5/6

- MyHC

myosin heavy chain

- NCBI

National Center for Biotechnology Information

- sFRP3

secreted Frizzled-related protein 3

- TCF

T-cell factor

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: No conflicts declared.

References

- 1.Tajbakhsh S. Skeletal muscle stem cells in developmental versus regenerative myogenesis. J Intern Med. 2009;266:372–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2009.02158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hutcheson DA, Zhao J, Merrell A, Haldar M, Kardon G. Embryonic and fetal limb myogenic cells are derived from developmentally distinct progenitors and have different requirements for beta-catenin. Genes Dev. 2009;23:997–1013. doi: 10.1101/gad.1769009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bentzinger CF, Wang YX, Rudnicki MA. Building muscle: molecular regulation of myogenesis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012:4. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a008342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Noden DM, Francis-West P. The differentiation and morphogenesis of craniofacial muscles. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:1194–1218. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamane A. Embryonic and postnatal development of masticatory and tongue muscles. Cell Tissue Res. 2005;322:183–189. doi: 10.1007/s00441-005-0019-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parada C, Han D, Chai Y. Molecular and cellular regulatory mechanisms of tongue myogenesis. J Dent Res. 2012;91:528–535. doi: 10.1177/0022034511434055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Messina G, Cossu G. The origin of embryonic and fetal myoblasts: a role of Pax3 and Pax7. Genes Dev. 2009;23:902–905. doi: 10.1101/gad.1797009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braun T, Gautel M. Transcriptional mechanisms regulating skeletal muscle differentiation, growth and homeostasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:349–361. doi: 10.1038/nrm3118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tajbakhsh S, Rocancourt D, Cossu G, Buckingham M. Redefining the genetic hierarchies controlling skeletal myogenesis: Pax-3 and Myf-5 act upstream of MyoD. Cell. 1997;89:127–138. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80189-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seale P, Sabourin LA, Girgis-Gabardo A, Mansouri A, Gruss P, et al. Pax7 is required for the specification of myogenic satellite cells. Cell. 2000;102:777–786. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00066-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berkes CA, Tapscott SJ. MyoD and the transcriptional control of myogenesis. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2005;16:585–595. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wells L, Edwards KA, Bernstein SI. Myosin heavy chain isoforms regulate muscle function but not myofibril assembly. EMBO J. 1996;15:4454–4459. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.MacDonald BT, Tamai K, He X. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling: components, mechanisms, and diseases. Dev Cell. 2009;17:9–26. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cisternas P, Henriquez JP, Brandan E, Inestrosa NC. Wnt signaling in skeletal muscle dynamics: myogenesis, neuromuscular synapse and fibrosis. Mol Neurobiol. 2014;49:574–589. doi: 10.1007/s12035-013-8540-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaufmann U, Kirsch J, Irintchev A, Wernig A, Starzinski-Powitz A. The M-cadherin catenin complex interacts with microtubules in skeletal muscle cells: implications for the fusion of myoblasts. J Cell Sci. 1999;112 (Pt 1):55–68. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tzahor E, Kempf H, Mootoosamy RC, Poon AC, Abzhanov A, et al. Antagonists of Wnt and BMP signaling promote the formation of vertebrate head muscle. Genes Dev. 2003;17:3087–3099. doi: 10.1101/gad.1154103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haegel H, Larue L, Ohsugi M, Fedorov L, Herrenknecht K, et al. Lack of beta-catenin affects mouse development at gastrulation. Development. 1995;121:3529–3537. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.11.3529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ikeya M, Takada S. Wnt signaling from the dorsal neural tube is required for the formation of the medial dermomyotome. Development. 1998;125:4969–4976. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.24.4969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Linker C, Lesbros C, Stark MR, Marcelle C. Intrinsic signals regulate the initial steps of myogenesis in vertebrates. Development. 2003;130:4797–4807. doi: 10.1242/dev.00688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmidt M, Patterson M, Farrell E, Munsterberg A. Dynamic expression of Lef/Tcf family members and beta-catenin during chick gastrulation, neurulation, and early limb development. Dev Dyn. 2004;229:703–707. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galli LM, Willert K, Nusse R, Yablonka-Reuveni Z, Nohno T, et al. A proliferative role for Wnt-3a in chick somites. Dev Biol. 2004;269:489–504. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmidt C, Stoeckelhuber M, McKinnell I, Putz R, Christ B, et al. Wnt 6 regulates the epithelialisation process of the segmental plate mesoderm leading to somite formation. Dev Biol. 2004;271:198–209. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Otto A, Schmidt C, Patel K. Pax3 and Pax7 expression and regulation in the avian embryo. Anat Embryol (Berl) 2006;211:293–310. doi: 10.1007/s00429-006-0083-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu Y, Sugiura Y, Wu F, Mi W, Taketo MM, et al. beta-Catenin stabilization in skeletal muscles, but not in motor neurons, leads to aberrant motor innervation of the muscle during neuromuscular development in mice. Dev Biol. 2012;366:255–267. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Munsterberg AE, Kitajewski J, Bumcrot DA, McMahon AP, Lassar AB. Combinatorial signaling by Sonic hedgehog and Wnt family members induces myogenic bHLH gene expression in the somite. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2911–2922. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.23.2911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maroto M, Reshef R, Munsterberg AE, Koester S, Goulding M, et al. Ectopic Pax-3 activates MyoD and Myf-5 expression in embryonic mesoderm and neural tissue. Cell. 1997;89:139–148. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80190-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borello U, Berarducci B, Murphy P, Bajard L, Buffa V, et al. The Wnt/beta-catenin pathway regulates Gli-mediated Myf5 expression during somitogenesis. Development. 2006;133:3723–3732. doi: 10.1242/dev.02517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brunelli S, Relaix F, Baesso S, Buckingham M, Cossu G. Beta catenin-independent activation of MyoD in presomitic mesoderm requires PKC and depends on Pax3 transcriptional activity. Dev Biol. 2007;304:604–614. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cossu G, Borello U. Wnt signaling and the activation of myogenesis in mammals. EMBO J. 1999;18:6867–6872. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.24.6867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suzuki A, Pelikan RC, Iwata J. WNT/beta-Catenin Signaling Regulates Multiple Steps of Myogenesis by Regulating Step-Specific Targets. Mol Cell Biol. 2015;35:1763–1776. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01180-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Otto A, Schmidt C, Luke G, Allen S, Valasek P, et al. Canonical Wnt signalling induces satellite-cell proliferation during adult skeletal muscle regeneration. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:2939–2950. doi: 10.1242/jcs.026534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Borello U, Coletta M, Tajbakhsh S, Leyns L, De Robertis EM, et al. Transplacental delivery of the Wnt antagonist Frzb1 inhibits development of caudal paraxial mesoderm and skeletal myogenesis in mouse embryos. Development. 1999;126:4247–4255. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.19.4247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Polesskaya A, Seale P, Rudnicki MA. Wnt signaling induces the myogenic specification of resident CD45+ adult stem cells during muscle regeneration. Cell. 2003;113:841–852. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00437-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brack AS, Conboy IM, Conboy MJ, Shen J, Rando TA. A temporal switch from notch to Wnt signaling in muscle stem cells is necessary for normal adult myogenesis. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:50–59. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rochat A, Fernandez A, Vandromme M, Moles JP, Bouschet T, et al. Insulin and wnt1 pathways cooperate to induce reserve cell activation in differentiation and myotube hypertrophy. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:4544–4555. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-11-0816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abmayr SM, Pavlath GK. Myoblast fusion: lessons from flies and mice. Development. 2012;139:641–656. doi: 10.1242/dev.068353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Han XH, Jin YR, Seto M, Yoon JK. A WNT/beta-catenin signaling activator, R-spondin, plays positive regulatory roles during skeletal myogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:10649–10659. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.169391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Han XH, Jin YR, Tan L, Kosciuk T, Lee JS, et al. Regulation of the follistatin gene by RSPO-LGR4 signaling via activation of the WNT/beta-catenin pathway in skeletal myogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2014;34:752–764. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01285-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pansters NA, van der Velden JL, Kelders MC, Laeremans H, Schols AM, et al. Segregation of myoblast fusion and muscle-specific gene expression by distinct ligand-dependent inactivation of GSK-3beta. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68:523–535. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0467-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dowling JJ, Vreede AP, Kim S, Golden J, Feldman EL. Kindlin-2 is required for myocyte elongation and is essential for myogenesis. BMC Cell Biol. 2008;9:36. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-9-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dowling JJ, Gibbs E, Russell M, Goldman D, Minarcik J, et al. Kindlin-2 is an essential component of intercalated discs and is required for vertebrate cardiac structure and function. Circ Res. 2008;102:423–431. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.161489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kemler R. From cadherins to catenins: cytoplasmic protein interactions and regulation of cell adhesion. Trends Genet. 1993;9:317–321. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(93)90250-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gates J, Peifer M. Can 1000 reviews be wrong? Actin, alpha-Catenin, and adherens junctions. Cell. 2005;123:769–772. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Krauss RS, Cole F, Gaio U, Takaesu G, Zhang W, et al. Close encounters: regulation of vertebrate skeletal myogenesis by cell-cell contact. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:2355–2362. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krauss RS. Regulation of promyogenic signal transduction by cell-cell contact and adhesion. Exp Cell Res. 2010;316:3042–3049. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jaeger MA, Sonnemann KJ, Fitzsimons DP, Prins KW, Ervasti JM. Context-dependent functional substitution of alpha-skeletal actin by gamma-cytoplasmic actin. FASEB J. 2009;23:2205–2214. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-129783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Crawford K, Flick R, Close L, Shelly D, Paul R, et al. Mice lacking skeletal muscle actin show reduced muscle strength and growth deficits and die during the neonatal period. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:5887–5896. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.16.5887-5896.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Clevers H, Nusse R. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling and disease. Cell. 2012;149:1192–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Abu-Baker A, Laganiere J, Gaudet R, Rochefort D, Brais B, et al. Lithium chloride attenuates cell death in oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy by perturbing Wnt/beta-catenin pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4:e821. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Block GJ, Narayanan D, Amell AM, Petek LM, Davidson KC, et al. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling suppresses DUX4 expression and prevents apoptosis of FSHD muscle cells. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22:4661–4672. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Alexander MS, Kawahara G, Motohashi N, Casar JC, Eisenberg I, et al. MicroRNA-199a is induced in dystrophic muscle and affects WNT signaling, cell proliferation, and myogenic differentiation. Cell Death Differ. 2013;20:1194–1208. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2013.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]