Abstract

Diabetes mellitus significantly increases the risk of cardiovascular disease and heart failure in patients. Independent of hypertension and coronary artery disease, diabetes is associated with a specific cardiomyopathy, known as diabetic cardiomyopathy (DCM). Four decades of research in experimental animal models and advances in clinical imaging techniques suggest that DCM is a progressive disease, beginning early after the onset of type 1 and type 2 diabetes, ahead of left ventricular remodeling and overt diastolic dysfunction. Although the molecular pathogenesis of early DCM still remains largely unclear, activation of protein kinase C appears to be central in driving the oxidative stress dependent and independent pathways in the development of contractile dysfunction. Multiple subcellular alterations to the cardiomyocyte are now being highlighted as critical events in the early changes to the rate of force development, relaxation and stability under pathophysiological stresses. These changes include perturbed calcium handling, suppressed activity of aerobic energy producing enzymes, altered transcriptional and posttranslational modification of membrane and sarcomeric cytoskeletal proteins, reduced actin-myosin cross-bridge cycling and dynamics, and changed myofilament calcium sensitivity. In this review, we will present and discuss novel aspects of the molecular pathogenesis of early DCM, with a special focus on the sarcomeric contractile apparatus.

Keywords: Diabetes, Prediabetes, Insulin resistance, Myocardium, Sarcomere, Protein kinase C, Rho kinase

Core tip: Pathological changes in cardiac muscle underlie diabetic cardiomyopathy (DCM) independent of hypertension and atherosclerosis. In advanced diabetes, fibrosis, hypertrophy and apoptosis, reduce myocardial compliance, which leads to increased diastolic filling pressures and overt left ventricular diastolic dysfunction. However, detrimental changes in sarcomeric and other cytoskeletal proteins in the cardiomyocytes of animal models of diabetes precede remodeling of the cardiac extracellular matrix, which has until now been considered the main contributor to diabetic diastolic dysfunction. An important target for preventing early DCM are the protein kinase C/rho-kinase pathways that drive oxidative stress and reduce myosin head cycling and prolong Ca2+ transients.

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes mellitus is a rapidly escalating global epidemic with the International Diabetes Federation predicting that the incidence of diabetes will rise to 552 million people worldwide by 2030[1]. Diabetes is a metabolic disorder characterized by hyperglycemia, insulin deficiency and or resistance. Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) is triggered by an autoimmune mechanism and accounts for approximately 5%-10% of diabetes cases. Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) represents 90%-95% of diabetes cases and is initiated by the interaction of genetic, environmental and lifestyle factors[2].

Diabetes is associated with a number of complications such as retinopathy[3], nephropathy[4], peripheral neuropathy[5] and cardiovascular disease, which are similar in their pathophysiological mechanisms in both T1DM and T2DM. Cardiovascular disease is the most common complication of diabetes and a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in patients[6]. Several lines of evidence have established that chronic diabetes is associated with pathological changes to the cardiac muscle[7-9], coronary vasculature[10-12] and cardiac autonomic nerves[13-15], all of which contribute to the increased risk of cardiovascular disease[16,17].

Independent of other cardiovascular complications, a large body of evidence indicates that diabetes is associated with a specific cardiomyopathy known as diabetic cardiomyopathy (DCM)[18-20]. In the long term, people with diabetes more frequently have cardiovascular complications and double the mortality rate[21]. Moreover, we have known for some time from the Framingham Heart study that diabetic men and women are 2 and 5 times more likely to develop heart failure respectively, independent of hypertension and coronary artery disease[22].

Initially, DCM was recognized by impaired myocardial relaxation and left ventricle (LV) stiffening with progressive development of LV interstitial fibrosis and cardiomyocyte hypertrophy[23]. Although the natural history of DCM has never been directly studied, extensive research utilizing experimental animal models of T1DM and T2DM and advances in clinical cardiac imaging over the past four decades support the notion that DCM is a progressive disease, beginning in the early time course of diabetes[24].

Clinical investigations indicate that features of DCM are present early after the onset of T1DM. In T1DM patients, early DCM is identified by subtly reduced peak myocardial systolic velocity and early diastolic velocity preceding overt diastolic dysfunction[25]. Early abnormalities in diastolic function are also apparent in patients with well-controlled T2DM in the absence of LV hypertrophy[26]. Similarly, in one of the most common animal models, the streptozotocin (STZ) induced diabetic rat, depressed rates of pressure development and decay, reduced end systolic developed pressure and prolonged relaxation times are evident as early as 2-3 wk post diabetes induction[27,28], prior to LV remodeling[28].

In the advanced stages of diabetes, a myriad of cellular signaling pathways are chronically activated within the heart, leading to fibrosis, hypertrophy and apoptosis, resulting in inadequate myocardial compliance, increased diastolic filling pressures and the development of overt LV diastolic dysfunction[24]. There is strong evidence from prevention and intervention studies using animal models that specifically targeting the structural manifestations of advanced DCM improves LV function[29-31]. However, in the clinical setting, there is still uncertainty as to whether structural remodeling is a cause or consequence of DCM[32]. Functional abnormalities in isovolumetric contraction and relaxation rates, as well as reduced systolic developed pressure are common to both early and advanced DCM. Moreover, it is not easy to diagnose when structural change has occurred. As these cardiac indices reflect the functional status of mechanisms regulating intracellular events within cardiomyocytes including the initiation and regulation of contraction and relaxation, there is sufficient evidence that demonstrates that subcellular changes to the cardiomyocytes can account for the functional abnormalities observed in early DCM.

In this review, we will focus on and discuss the multiple cellular biochemical derangements, intracellular signaling cascades as well as the structural and functional changes to the cardiomyocyte and sarcomere that establish the beginnings of contractile dysfunction in DCM ahead of myocardial remodeling and overt LV diastolic dysfunction.

EARLY BIOCHEMICAL DYSFUNCTION AND THE CELLULAR SIGNALING PATHWAYS INVOLVED IN DCM

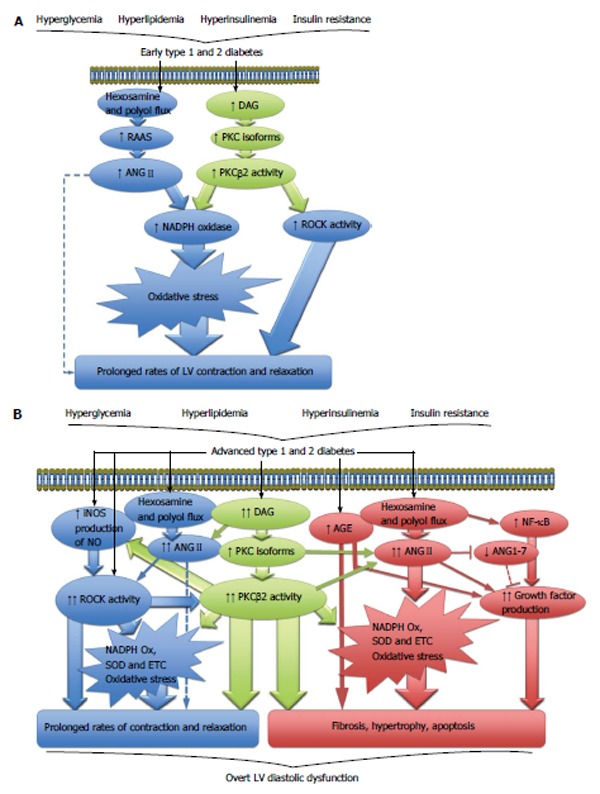

Diabetes is associated with hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia, hyperinsulinemia and or insulin resistance. However, unlike T1DM, abnormal glucose homeostasis, hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance frequently precede development of T2DM[33]. Regardless of the etiology of the disease, diabetes results in multiple cellular metabolic derangements, including increased production and accumulation of advanced glycation end-products in the extracellular space, increased polyol and hexosamine pathway flux and activation of various protein kinase C (PKC) isoforms[34] (Figure 1). In the myocardium, these biochemical derangements drive the generation of oxidative stress, a key contributor to the development of DCM[35] (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Cellular signaling pathways. A: Cellular signaling pathways driving contractile dysfunction in early diabetic cardiomyopathy; B: Cellular signaling pathways involved in the development of overt LV diastolic dysfunction in diabetes. ANGII: Angiotensin II; DAG: Diacylglycerol; NADPH: Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate; PKC: Protein kinase C; RAAS: Renin angiotensin aldosterone system; ROCK: Rho kinase; AGE: Advanced glycation end products; ANG1-7: Angiotensin 1-7; ETC: Electron transport chain; iNOS: Inducible nitric oxide synthase; NF-κB: Nuclear factor-κB; NO: Nitric oxide; SOD: Superoxide dismutase; LV: Left ventricle.

Oxidative stress

The development of oxidative stress has long been recognized as a cardinal molecular event in the initiation and progression of DCM. Importantly, in the long-term, diabetes and insulin resistance induce myocardial oxidative stress from a number of sources leading to enhanced production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species, whilst also diminishing the heart’s antioxidant defense system (reviewed by[36]). The specific mechanisms of how each of these sources generate oxidative stress are beyond the scope of this review and are described in detail by Huynh et al[37].

In the setting of chronic experimental diabetes, oxidative stress has been consistently implicated in myocardial remodeling and diastolic dysfunction. Studies conducted by our group and others demonstrate that elevated ROS expression and compromised antioxidant defense are associated with myocardial fibrosis, hypertrophy and diastolic dysfunction in STZ induced T1DM rats[38,39]. Similar findings have been reported in genetic models of advanced T2DM including the db/db mouse[40], the Goto Kakizaki (GK) rat[38] and the Otsuka Long-Evans Tokushima Fatty (OLETF) rat[41].

A role for oxidative stress in the initiation of DCM has also been shown to occur early after the induction of diabetes in animals. One source of myocardial oxidative stress that certainly plays a role in early DCM is nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase. Inhibition of NADPH oxidase shortly after the onset of diabetes attenuates subsequent interstitial fibrosis and completely restores systolic and diastolic function in diabetic rats[42]. Three to five weeks post induction of diabetes in rats, there is a significant increase in myocardial oxidative stress (nitrotyrosine and lipid peroxidation), which is associated with contractile dysfunction[43,44]. Antioxidant treatment with N-acetylcystine (NAC) significantly improved the prolonged rates of LV pressure decay, but not the rates of pressure development[43]. While myocardial remodeling was not directly assessed by Cheng et al[43], the improvements in LV diastolic indices they observed are most likely caused through actions on cardiomyocyte and sarcomeric function (Figure 1A).

Oxidative stress has been widely reported to induce posttranslational modifications of a large variety of contractile proteins within the sarcomere with redox modifications of such proteins playing a pivotal role in the evolution of heart failure (reviewed extensively by references[45,46]). Therefore, in early DCM, cardiac contractile dysfunction is likely to arise in some part as a consequence of oxidative stress, through posttranslational modifications of contractile proteins as opposed to myocardial structural alterations derived from the increasing burden of chronic oxidative stress associated with advanced DCM. Two distinct cellular signaling cascades that drive generation of oxidative stress through NADPH production are the renin angiotensin aldosterone system (RAAS)[47,48] and the PKCβ2 pathway[49,50] (Figure 1A). Both have been implicated in the early pathogenesis of DCM.

RAAS

It has been known for many years that the RAAS is a key contributor to the development and progression of renal[51], vascular[52] and cardiac[53] complications in diabetic patients, mainly by its effector molecule, angiotensin II (ANGII). Since systemic RAAS activity is unchanged or downregulated in diabetes[54,55], local RAAS in the heart is thought to be responsible for the local production of ANGII. All the components of the classic RAAS have been identified in the heart including renin, angiotensinogen, ANGI, angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE), ANGII and ANGII type 1 receptors (AT1R)[56]. Traditionally, it is accepted that chronic activation of the RAAS in advanced T1DM and T2DM diabetes increases myocardial levels of ANGII. In addition to its potent vasoconstrictor actions, ANGII promotes myocardial remodeling by driving collagen production, extracellular matrix protein accumulation[57], fibrosis, myocyte hypertrophy, apoptosis, impaired calcium handling, myofibrillar dysfunction and oxidative stress, all of which combine to evoke overt LV diastolic dysfunction[48,58-65] (Figure 1B). Newer evidence suggests that in addition to the activation of classic RAAS, diabetes sequesters the activity of the cardiac ACE2-ANG-(1-7)-Mas receptor axis (Figure 1B), which opposes the pressor, fibrotic and hypertrophic effects of ANGII (reviewed in references[66-68]). Although RAAS research in the context of DCM is in its infancy, the few studies conducted have reinforced the notion that diabetes suppresses cardiac ACE2-ANG-(1-7)-Mas receptor pathway in the hearts of rodents with chronic T1DM[58,69] and T2DM[62], resulting in myocardial remodeling and diastolic dysfunction in the long term (Figure 1B). Therefore, restoring the balance of the pathological and cardioprotective arms of local RAAS in chronic DCM has been proposed as a novel and more effective therapeutic strategy[66,68].

In prediabetic, insulin resistant and early T1DM animal models, there is also a potential role for elevated myocardial ANGII and activation of the classic RAAS arm in the initiation of cardiomyopathy. AT1R-dependent NADPH oxidase-mediated oxidative stress is apparent in the hearts of insulin resistant, prediabetic OLETF rats[70]. Normal myocardial nitric oxide production is restored after AT1R blockade in a dietary induced rat model of obesity and insulin resistance[71]. Moreover, one week of STZ diabetes in rats significantly increases intracellular ANGII content in cardiomyocytes and is associated with myocardial oxidative stress and apoptosis[72]. Unfortunately, as cardiac function was not assessed in these studies, it is not possible to say if the activation of the classic RAAS is responsible for LV contractile dysfunction documented in these early stages of diabetes. However, in support of this possibility, other studies have shown that increased RAAS activity in the hearts of diabetic animals is associated with impaired calcium handling[60,73] and reduced myofibrillar ATPase activity[64]. Thus, there is a strong possibility for an early involvement of the RAAS in the pathogenesis of DCM as these subcellular alterations are often associated with early LV contractile dysfunction in diabetes (Figure 1A, broken line). Further studies are needed to clarify the involvement of classic RAAS and the ACE2-ANG-(1-7)-Mas receptor axis in contractile dysfunction at this time point, and if other angiotensin peptides[74] and the AT2R have any role in DCM development.

PKCβ2 pathway

There are multiple PKC isoforms in existence (α, β1, β2, γ, δ, ε, η, θ, ξ, ι/λ), which all regulate a large variety of cellular functions. In diabetes, hyperglycemia causes de novo synthesis of diacylglycerols, in turn activating several PKC isoforms in various tissues including the eye, kidney, vasculature and heart (reviewed extensively elsewhere[75,76]) (Figure 1A). Of particular interest is the PKCβ2 isoform, which is found in the right and left ventricles of the heart[77]. In rodent models of chronic STZ-induced T1DM, increased PKCβ2 expression and activity results in cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, fibrosis and impaired cardiomyocyte calcium handling capabilities, ultimately prolonging active diastolic relaxation and reducing passive compliance[78-81] (Figure 1B). Elevated myocardial PKCβ2 expression levels are also reported in a rat model of dietary induced insulin resistance and T2DM[82].

In the context of early DCM, one month after STZ induced diabetes in pigs, both cardiac PKCβ2 mRNA and protein expression is significantly increased compared to euglycemic controls[83]. Consistent with this finding, two weeks post STZ diabetes induction, PKCβ2 protein activity is significantly increased in the hearts of rats[84]. Furthermore, selective PKCβ2 inhibition from shortly after the onset of STZ diabetes prevented cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and NADPH oxidase mediated oxidative stress and thereby restored cardiac function to that of control rats[85]. A significant finding of that study was antioxidant treatment with NAC had comparable effects to PKCβ2 inhibition in attenuating NADPH induced myocardial oxidative stress and hypertrophy. However, PKCβ2 inhibition was superior in preventing cardiac dysfunction by completely restoring isovolumetric relaxation times[85]. This suggests that PKCβ2 also acts through oxidative stress independent pathways in the development of LV contractile dysfunction in early diabetes.

The Rhoa/Rho kinase pathway axis - a possible mechanism for oxidative stress independent contractile dysfunction in early DCM

The Rho Kinases (ROCK), ROCK1 and ROCK2, are Rho-associated kinases activated by the small GTP-binding protein RhoA. ROCK1 is ubiquitously expressed, whereas ROCK2 appears to be brain and cardiac specific[86]. The RhoA/ROCK pathway controls a diverse range of cellular processes in the cardiovascular system (see review[87]), but primary actions of ROCK that are pertinent to this review are the regulation of actin-myosin interactions[88] and maintenance of cytoskeletal structure[89].

A large body of evidence has established that ROCK is a key mediator of diastolic dysfunction in various rodent models of heart disease including hypertensive cardiomyopathy[90-93], pressure-overload hypertrophy[94] and myocardial infarction in mice[95], as well as in patients with chronic heart failure[96]. As a consequence, ROCK has gained attention as a promising therapeutic target for diabetic patients with diastolic dysfunction and preserved ejection fraction[97]. In a small cohort of T2DM patients, daily administration of fasudil, a specific ROCK inhibitor, for two weeks significantly improved isovolumetric relaxation time, deceleration time, E/A wave ratio and E/e’ wave ratio in comparison to baseline measures and placebo treated patients[97]. Although not specifically identified in the aforementioned clinical study, elevated ROCK activity leads to diastolic dysfunction in chronic diabetes by inducing fibrosis, hypertrophy and cardiac ultrastructural remodeling[98,99]. However, considering that ROCK is pivotal in regulating contractility at the level of the sarcomere and given the marked improvement in active diastolic indices in patients treated with fasudil, we speculate that elevated ROCK activity primarily drives diastolic dysfunction by modulation of sarcomeric proteins.

Early ROCK activation may also contribute to the initiation of DCM. Acute inhibition of ROCK in diabetic rats rapidly alleviates cardiac contractile dysfunction and increases developed force[100], confirming ROCK has a direct interaction with the cardiomyocyte’s contractile apparatus. Work conducted by our group demonstrates depressed actin-myosin dynamics and LV contractile dysfunction[101] is associated with modestly elevated myocardial ROCK1 and ROCK2 expression[102] suggesting that in the early diabetic rat heart, ROCK may drive contractile dysfunction by impairing actin-myosin interaction. Interestingly, we found all of these changes to occur largely independent of oxidative stress[102]. Given the recent studies describing complex interactions between PKCβ2 and ROCK in chronic experimental DCM[103,104] and the hypothesis that PKCβ2 is able to modulate cardiac function by oxidative stress independent mechanisms[85], it is conceivable that PKCβ2 may indeed be acting through ROCK to prolong diastolic relaxation times (Figure 1A). Thus, there is strong evidence that implicates the PKCβ2/RhoA/ROCK pathway in the pathogenesis and progression of DCM[104]. Future investigations that examine the roles of ROCK at the level of the sarcomere in early diabetes may provide a clearer understanding of the initiating factors involved in DCM.

EARLY STRUCTURAL AND FUNCTIONAL CHANGES TO THE CONTRACTILE APPARATUS IN DCM

It has been widely held for some time that the diastolic dysfunction associated with DCM is primarily attributed to increased LV fibrosis and hypertrophy, causing stiffening of the myocardium. However, a growing number of research findings provide evidence that insulin resistance and hyperglycemia also alter cardiomyocyte intracellular processes responsible for initiating and regulating cardiac contraction and force development on a beat-to-beat basis (see reviews[105,106]). These include declines in cardiomyocyte calcium handling abilities, aerobic energy producing enzyme activity, integrity of cytoskeletal structures as well as sarcomeric dysfunction (Figure 2). In the following section we will discuss how all of these subcellular alterations contribute to contractile dysfunction in early DCM in both T1DM and T2DM (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Subcellular alterations in various compartments of the cardiomyocyte in diabetic cardiomyopathy. PLB: Phospholamban; SERCA: Sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase; SR: Sarcoplasmic reticulum; RyR: Ryanodine receptor.

Table 1.

Reported subcellular alterations to cardiomyocyte structure and function in early type 1 and type 2 diabetes and gaps in our current knowledge

| Cardiomyocyte function change | Type 1 diabetes | Type 2 diabetes | |

| Excitation-contraction | (-) ↑ | ↑↑ cTnI phosphorylation[181] | ↑ Ca2+ transient times[113] |

| coupling, calcium release- | (-) cTnI phosphorylation, Ca2+ sensitivity[123] | ↑ SERCA expression, SR Ca2+ reuptake[115] | |

| reuptake and calcium | ↓ | ↑ PKCβ2 mediated AGE increase, Ca2+ release[50] | ↓ SERCA, RyR expression[111,112] |

| sensitivity | ↓ SERCA activity[107,109,110] | ↑ SR Ca2+ reuptake time[111,112] | |

| ↓ SERCA and RyR expression[110] | |||

| ↓ Diastolic Ca2+ extrusion[109] | |||

| ↑ SR Ca2+ reuptake time[108,109] | |||

| Aerobic energy production | (-) | (-) ATP turnover1[125] | ? |

| Sarcomere organization | (-) Myofibrillar, sarcomeric order[130] | ? | |

| Contractile force development | (-) | ↑ Systolic LV pressure, CB formation[139] | |

| ↓ | ↓ Myosin, myofibrillar ATPase activity[117-120,143] | ? | |

| ↓ CB cycling, myosin-actin proximity[101,123,124] | |||

| ↓ MLC2 phosphorylation, (-) cMyBP-C phosphorylation[123] | |||

| ↑ ROCK expression, (-) nitrosylation[102] | |||

| Contractile force transmission, | ↓ | ↑ V3 myosin isozyme expression[117,122-124] | ↑ Diastolic myosin head separation[139] |

| sliding velocity and | ↓ Myosin head extension[101] | ↑ Ventricular, myocyte relaxation[111,112] | |

| compliance | ↓ Relaxation rate[101,123,124] | ↑ Shortening time[113] | |

| ↓ MLC2 phosphorylation, (-) cMyBP-C phosphorylation[123] | ↑ Relaxation time[114] | ||

| ↑ Nitrosylation, lipid peroxidation, prolonged relaxation[43,44] | |||

| Cardiomyocyte hypertrophy | ↑ | ↑ ANGII mediated oxidative stress[72] | ↑ ANGII mediated NADPH Ox[70] |

| and apoptosis | ↑ PKCβ2 mediated oxidative stress, apoptosis[50] | ||

| ↑ PKCβ2 mediated oxidative stress, hypertrophy[85] | |||

References quoted as they appear in text. 1Study conducted in humans; (-): No change compared to controls; AGE: Advanced glycation endproducts; ANGII: Angiotensin II; CB: Cross-bridge; cMyBP-C: Cardiac myosin binding protein C; cTnI: Cardiac troponin I; MLC2: Myosin light chain 2; NADPH Ox: Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase; PKC: Protein kinase C; ROCK: Rho kinase; RyR: Ryanodine receptor; SERCA: Sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase; SR: Sarcoplasmic reticulum; LV: Left ventricle.

Alterations in calcium handling proteins and excitation-contraction coupling

Sufficient and timely transport of calcium ions (Ca2+) in and out of the cardiomyocyte and sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) is vital for the maintenance of normal cardiac function. During systole, Ca2+ enters through sarcolemma L-type Ca2+ channels and Ca2+ clusters are released spontaneously from the SR Ca2+ stores via the ryanodine receptor (RyR). The release of Ca2+ clusters causes Ca2+ sparks and initiates contraction by excitation-contraction coupling. In diastole, Ca2+ is pumped back into the SR via SR Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) and out of the cytosolic spaces by the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger, driving myocardial relaxation.

Systolic and diastolic Ca2+ handling impairment is characteristic of T1DM, even in the early stages. Three weeks post STZ, SR Ca2+ reuptake is prolonged and SERCA activity is decreased in comparison to the control group of normoglycemic rats[107]. Slowed rates of contraction and relaxation in diabetic rats were attributed to prolonged Ca2+ transients and SR reuptake in isolated papillary muscle preparations[108]. In the whole heart, Takeda et al[109] also reported that prolonged myocardial relaxation in early diabetes was associated with depressed sarcolemma Ca2+ extrusion and SR Ca2+ reuptake, and reduced SERCA activity. More recently, it has been demonstrated that a progressive loss of cardiomyocyte Ca2+ handling abilities occurs ahead of LV contractile dysfunction in diabetic rats[110].

Whether impaired Ca2+ handling is also an early event in the insulin resistant state and early T2DM is unclear. For example, in sucrose fed rats with insulin resistance[111] and early T2DM[112], impaired ventricular and cardiomyocyte relaxation is associated with decreases in SERCA and RyR expression and prolonged SR Ca2+ reuptake. However, in young prediabetic GK rats, appreciable changes in gene expression of Ca2+ handling proteins only resulted in moderate prolongation of shortening and a slower decay of Ca2+ transients[113]. Similarly, in cardiomyocytes from young Zucker diabetic fatty (ZDF) rats, prolonged relaxation times cannot be fully explained by disruptions in Ca2+ handling[114]. In stark contrast, Fredersdorf et al[115] have reported increased SERCA expression and Ca2+ sequestration in ZDF rats with early DCM, suggesting enhanced Ca2+ handling capabilities may be a compensatory mechanism to preserve cardiac function in the presence of hyperglycemia. Thus, subtle or moderately compromised cardiac contractile performance is not always attributable to changes in Ca2+ handling, except in early T1DM. Altered Ca2+ handling appears to be more important later in the course of diabetes.

Myosin heavy chain, myofibrillar/myosin ATPases and energy depletion

For cardiac contraction to occur, ATP bound to myosin must be hydrolysed to ADP and phosphate. Once the phosphate is released, ADP causes myosin to be strongly bound to actin and induces the force-producing power stroke. Therefore, the rate-limiting step of cardiac contraction is ATP hydrolysis by myofibrillar and myosin ATPase[116]. It has been known for several decades now that reduced myosin and myofibrillar ATPase activity is associated with contractile dysfunction in early diabetes. Three to four weeks post induction of T1DM, myosin and myofibrillar ATPase activities are significantly reduced in diabetic rats compared to normoglycemic, age-matched controls[117,118]. Other studies have demonstrated that decreased myosin and myofibrillar ATPase activity is associated with in vivo contractile dysfunction in early diabetes in rats[119] and reduced force development in isolated muscle preparations[120]. Depression of myosin and myofibrillar ATPase activity in the diabetic heart is due to myosin isozyme switching from V1 to V3. Myosin isozyme expression is determined by the predominant myosin heavy chain (MHC) dimer[121]. In the adult rodent heart, the V1 (MHCαα homodimer, α-MHC) is present[105], however isozyme switching to the V3 (MHCββ homodimer, β-MHC) is commonly exhibited in diabetic rodents. Such a V3 isozyme shift has been reported along with depressed myosin ATPase activity in early diabetic rats, with some demonstrating a concomitant prolongation of tension development (without change in net tension development) and contraction times in isolated papillary muscle preparations[117,122]. Notably, it has been shown that marked expression of β-MHC slows actin-myosin kinetics and thereby contributes to contractile dysfunction in early diabetes[123,124].

Despite these convincing studies using animal models, clinical experiments utilizing phosphorus magnetic resonance spectroscopy in T2DM patients with early DCM have found no association between diastolic dysfunction and ATP turnover[125]. Thus, it is unclear if altered energetics of contraction is a cause or consequence of diabetes.

Changes in the structural compliance and order of the cardiomyocyte cytoskeleton network

The cardiomyocyte cytoskeleton is a highly organized and complex subcellular structure. The cytoskeleton can be divided into four main structures, this being the sarcomeric, extra-sarcomeric, membrane-submembrane and nuclear cytoskeleton[126]. Although the cytoskeleton is considered a unified structure throughout the cardiomyocyte, there is a clear functional division between the contractile part, the sarcomere, and the non-contractile parts that transmit the developed power and ensures structural integrity of the cell and the functional syncytium[127]. Arguably, the extra-sarcomeric cytoskeleton, comprising of microtubules, actin myofilaments and intermediate desmin filaments are as important for myocyte contraction as the sarcomeres, since these structures transfer the power produced by the sarcomeres through tethering of the sarcomere at the Z-disc to the submembrane skeleton and sarcolemma.

In the diabetic heart, there are inconsistent findings concerning the possible involvement of structural alterations to the sarcomere in the development of contractile dysfunction. One study using electron microscopy reported that hearts with advanced DCM exhibited disarray of normal sarcomeric order, which was associated with contractile dysfunction[128]. However, others have been unable to corroborate this finding. In contrast, ventricular ultrastructure, and especially the contractile apparatus, remained largely unchanged 8 mo post T1DM induction in rats[129]. Jackson et al[130] demonstrated that in the initial stages of DCM sarcomeric and myofibrillar assembly remain unchanged from that of age-matched, normoglycemic controls, despite depressed contractile function. A unique feature of the sarcomeric cytoskeleton is the interaction of a myriad of proteins that provide exceptional stability. One of the major scaffolding proteins within the sarcomere is titin, a giant protein that spans half of the sarcomere from the Z-disc to the M-line, which provides spring-like recoil of the sarcomere to its relaxed length and facilitates power transmission of the sarcomere through the Z-disc. Titin exists in two isoforms; the stiffer N2B and the more elastic N2BA[131]. The expression ratio and phosphorylation state of both isoforms are tightly controlled to regulate myocyte compliance and sarcomeric order[132]. In the adult heart, the N2B isoform is predominantly expressed[133], although a transition toward the N2BA isoform has been observed during the progression to heart failure[134]. Indeed, titin isoform switching from N2B to N2BA has been demonstrated in the hearts of rats with advanced T1DM and diastolic dysfunction[135]. Interestingly, in obese rats with T2DM, titin N2B hypophosphorylation contributes to contractile dysfunction in the absence of a change of isoform composition[136]. Nevertheless, it is plausible that changes in composition and or phosphorylation of sarcomeric cytoskeletal proteins may be more responsible for contractile dysfunction in diabetes as opposed to overt disruption of sarcomeric order and organization.

Diabetes also affects microtubule function in the extra-sarcomeric compartment of the cytoskeleton. Microtubules are hollow protein cylinders created by the polymerization of α and β tubulin heterodimers. Amongst other functions, microtubules regulate the flexibility of the cytoskeleton and thus the contractile capacity[127]. In the hearts of diabetic rats, microtubule flexibility is diminished[137,138]. The lack of microtubule flexibility impedes adequate transfer of the power generated by the sarcomere and thus, contributes to contractile dysfunction[137,138]. Polymerization of cytoskeletal actin filaments is increased in diabetes and essential for activation of the PKCβ2/RhoA/ROCK pathways[104]. The contribution of the extra-sarcomeric cytoskeleton is commonly overlooked in the pathogenesis of DCM and warrants further investigation, not only in areas of mechanical power translation but signal transduction between the sarcolemma, sarcomeres and the nucleus.

Actin-myosin cross-bridge dysregulation

The formation and dissociation of the actin-myosin cross-bridges (CBs) in the cardiac sarcomere is a pivotal determinant of force development and contractility. Various experimental approaches including X-ray diffraction[139], simultaneous recording of heat generation[140] and the measurement of the work of isolated muscle[141] have been used to investigate cardiac performance at the level of the sarcomere and cardiomyocyte. These approaches show that impaired cyclic transfer of myosin heads to actin filaments contributes to contractile dysfunction at the sarcomere level at the onset of diabetes. Moreover, CB dysregulation is also observed in the prediabetic state in the heart of insulin resistant animals.

A significant reduction in CB cycling has been reported in isolated cardiac muscle from early diabetic rats, due to a preferential shift to the less efficient β-MHC isoform[123,124]. Indeed the time required for CB detachment is inversely related to the proportion of α-MHC expression in isolated ferret papillary muscle, attesting to a clear role for β-MHC content in prolonging CB kinetics[142]. Joseph et al[143] demonstrated a reduced rate of CB attachment and detachment due to diabetes in ex vivo papillary muscle, as well as a significant reduction in the total number of CBs recruited, without a change in force developed per CB. Impaired CB dynamics in this preparation was attributed to a slower myosin ATPase turnover[143]. Accordingly, T1DM is claimed to have no discernible effect on CB mechanical efficiency in isolated trabeculae from rats[144]. Although it is important to recognize that in contrast to Joseph et al[143], the estimated number of CBs attached during contraction did not differ between control and diabetic rats in the study of Han et al[144]. Recent X-ray diffraction studies conducted by our group affirm these previous findings when CB dynamics are determined across the different layers of the ventricular muscle in situ, in the hearts of early diabetic[101] and prediabetic insulin resistant rats[139]. We demonstrated significant myosin head displacement from actin filaments throughout the cardiac cycle, but especially at end diastole, in the rat heart three weeks post STZ induction[101]. Reduction in the proximity of myosin heads to actin filaments at end diastole was directly correlated with a prolonged LV pressure decay rate in diabetic rats. Further, a transmural gradient was found in actin-myosin separation, being most pronounced in the deeper subendocardial layer[101]. However, we also found that the change in CB transfer to actin under β-adrenergic stimulation was comparable in control and diabetic rats suggesting that the impairment of the contractile apparatus precedes that of the β-adrenoceptor signaling[101]. In young prediabetic GK rats, we also found significant myosin head displacement from actin at end diastole in the subendocardial layer of the LV wall[139]. It is still unclear if these altered CB dynamics translate to significant LV dysfunction, but fiber shortening and Ca2+ transients are reported to be more prolonged in young GK rats[113].

It is noteworthy that X-ray diffraction recordings from the in situ beating heart demonstrate in both STZ induced diabetic rats and young prediabetic GK rats that myosin-myosin separation (interfilament spacing) does not differ from that of controls, and therefore altered myosin head distribution cannot be explained by a difference in sarcomere length[101]. Since alterations in thin filament complex cannot explain changes in myosin head extension (despite being a critical determinant of Ca2+ sensitivity and CB cycling rates), this implies that modifications to thick filament proteins that regulate myosin head extension are likely to be involved in the impaired CB dynamics and contractile dysfunction in early DCM.

The thick filament accessory proteins - regulators of myosin head extension

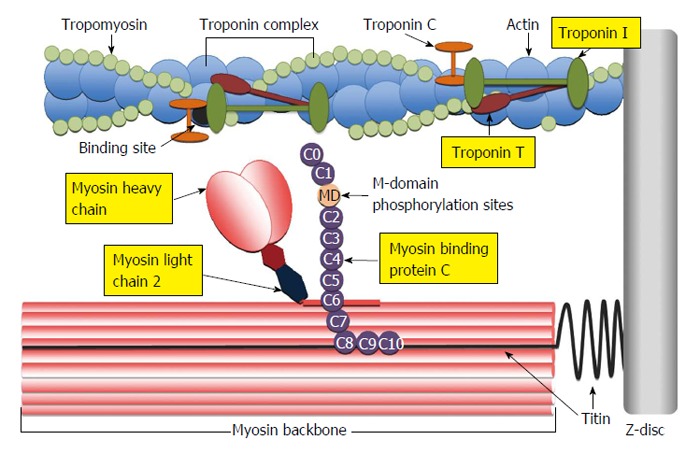

Two major proteins reside within the myosin thick filament complex that regulate myosin head extension, namely myosin light chain-2 (MLC2), otherwise known as regulatory light chain and cardiac myosin binding protein-C (cMyBP-C) (Figure 3). Detailed information on the complex molecular structure and broader physiological functions of both these proteins is beyond the scope of this paper but has been reviewed extensively by others (see reviews[145-149]).

Figure 3.

Illustration of the cardiac sarcomere indicating the location of actin thin-filament and myosin thick-filament accessory proteins involved in the regulation of actin-myosin cross-bridge dynamics and kinetics. C0-C10: Immunoglobulin-like and fibronectin-like domains of myosin binding protein C; MD: M-domain of myosin binding protein C containing protein kinase phosphorylation sites.

It is well accepted that MLC2 and cMyBP-C regulate myosin head extension by means of kinase phosphorylation. In the case of MLC2, phosphorylation is tightly regulated by MLC kinase and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaMK), and is dephosphorylated by MLC phosphatase (see review[150]). X-ray diffraction experiments conducted by Colson et al[151] reveal that the negative charge created on the myosin neck when MLC2 is phosphorylated, repels the negative charge of the myosin backbone and thus, subsequently the myosin heads are displaced toward the actin filament.

cMyBP-C is a multifunctional protein within the sarcomere that is primarily involved in the regulation of contractility[152-155] and the organization and structural maintenance of the sarcomere[156-158]. cMyBP-C prevents myosin head projection toward actin by a “tethering” mechanism[159], however, upon phosphorylation, the molecular tether mechanism is released and myosin heads are freed to be displaced towards actin[160,161]. As protein kinase A (PKA) is the primary kinase that phosphorylates cMyBP-C, it is thought that under β-adrenergic stimulation, cMyBP-C works in cooperation with the troponin complex to maintain force development and adequate relaxation and LV filling at higher heart rates[151]. In support of this proposed role, cMyBP-C phosphorylation by PKA evokes radial displacement of myosin heads toward actin in isolated cardiac muscle[162]. To date, seventeen phosphorylation sites have been identified on cMyBP-C[163], however three (Ser273, Ser282, Ser302)[164] have been identified as crucial regulators of contractility, which are all located within the M-domain of cMyBP-C (Figure 3). CaMK is also able to phosphorylate cMyBP-C at these sites in a Ca2+ dependent manner and thereby play a potentially important role in regulating contractile function independent of changes in intracellular Ca2+ transients[165,166].

Several studies have demonstrated diminished phosphorylation of cMyBP-C in experimental[167,168] and human[163,168,169] non-diabetic cardiac disease. Although there is paucity of information in the literature, some evidence suggests that MLC2 and cMyBP-C phosphorylation are also reduced in DCM. In the hearts of diabetic rats, a significant depression of MLC2 phosphorylation is reported, accompanied by prolonged LV pressure development and decay rates[170]. Diabetic swine also exhibit significantly reduced cMyBP-C phosphorylation[171]. Most recently, in a rat model of early DCM, MLC2 phosphorylation was significantly reduced in comparison to normoglycemic controls while cMyBP-C phosphorylation remained unchanged[123].

It should also be appreciated that other kinases including PKCβ2 and ROCK can directly phosphorylate cMyBP-C, and thus, potentially impact on contractile function, without appreciably altering pan phosphorylation state. In isolated rat cardiomyocytes, increased PKCβ2 expression did not change pan phosphorylation of cMyBP-C despite prolonging rates of shortening and relaxation, but phosphorylation of Ser302 in particular was significantly increased[172]. Taken together with the finding that phosphorylation Ser302 on cMyBP-C modulates CB kinetics[173], this suggests that the contractile dysfunction observed in the isolated cardiomyocytes may, in part, be a result of altered CB dynamics. Others have also demonstrated active ROCK directly phosphorylates cMyBP-C in cardiomyocytes[174]. Therefore, it is possible that cMyBP-C phosphorylation by PKCβ2 and ROCK may not alter pan phosphorylation, but may indeed impair CB dynamics by displacing myosin heads from the thin filaments and slowing rates of CB attachment and detachment. At the very least, thick filament accessory proteins probably play a role in contractile dysfunction in early DCM, although this requires further investigation.

The actin thin filament troponin complex-could changes in calcium sensitivity contribute to early DCM?

Much of our previous discussion has focused on diabetes impact on the myosin thick filament, however we cannot overlook the importance of the actin thin filament in modulating cardiac contractile properties. The hetero-trimeric cardiac troponin (cTn) complex is comprised of cTnC (Ca2+ reception site), cTnT and cTnI, the latter two are involved in the transduction of the Ca2+-binding signal (Figure 3). The multiple interactions of cTnI and cTnT with actin and tropomyosin regulate CB kinetics and the number of recruited CBs (reviewed in[175]) (Figure 3).

cTnI is widely recognized to be the principle regulator of CB kinetics and myofilament sensitivity of the thin filament. Under physiological conditions, increased cTnI phosphorylation at Ser23/24 by PKA (which usually occurs under β-adrenergic stimulation) leads to decreased myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity and accelerated CB dissociation, and thus hastened relaxation[176]. However, under pathophysiological conditions when expression and activity of PKC isoforms are elevated, PKC rather than PKA predominantly phosphorylates cTnI[177]. Ca2+ sensitivity is decreased by PKC phosphorylation at Ser23/24 of cTnI in a manner similar to physiological phosphorylation by PKA, but in contrast, phosphorylation of other sites (Ser44/45 and Thr144) slow CB cycling and sliding velocity and impair relaxation[176]. Thus, PKC-mediated phosphorylation of cTnI may partly explain contractile dysfunction in advanced DCM. Many studies have demonstrated that depressed myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity and PKC-induced increases in cTnI phosphorylation are observed in the hearts of rats after eight to twelve weeks of T1DM[178-180].

In early DCM however, there are some conflicting findings regarding the contribution of cTnI. One study found that cellular PKCε translocation paralleled a 5-fold increase in cTnI phosphorylation[181]. Importantly, neither cardiomyocyte function nor myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity was examined in this study. Conversely, others reported no changes in cTnI phosphorylation or myofilament calcium sensitivity four weeks post T1DM induction[123]. Therefore, there are some uncertainties as to the role of cTnI changes in early DCM. Given the strong evidence implicating cTnI in chronic diabetes models, this may only be a prominent driver of contractile dysfunction in the advanced stages of DCM.

Interestingly, ROCK is able to phosphorylate multiple sarcomeric proteins. Vahebi et al[174] revealed a direct role for ROCK activation in depressing myofilament tension development and ATPase activity via phosphorylation of cTnT of the thin filament complex, independent of MLC2 phosphorylation. A possible limitation of these findings is that the authors used constitutively active ROCK2, and whilst many other studies have demonstrated functional changes in diabetes with selective ROCK inhibition, not all have found an increase in ROCK phosphorylation[102,182]. Nonetheless, there is evidence to suggest an increase in ROCK activation in diabetes could contribute to reduced CB cycling through modulation of the thin filament, as well as the thick filament.

OTHER EXACERBATING RISK FACTORS OF DCM

In the clinical setting, DCM is rarely diagnosed independent of any additional risk factors, however, the cumulative effects of multiple risk factors in insulin resistance and diabetes has been rarely considered in preclinical studies. Risk factors that have been shown to exacerbate these disease states include hypertension and obesity, both commonly present with T2DM in patients (reviewed by reference[183]). Hypertension alone is a serious risk factor for the development of diastolic heart failure. Raised systolic blood pressure associated with hypertension evokes an increase in cardiac afterload and accordingly, vascular remodeling and LV hypertrophy ensue as pathophysiological adaptations to maintain cardiac output. Several decades earlier, Factor et al[184] showed that diabetes combined with hypertension increased microvessel tortuosity, microaneurysms and focal constrictions more than either disease state alone, which would increase the risk of myocardial ischemia. Activation of the RAAS and sympathetic nervous system (SNS) in the hypertensive state leads to fibrosis and cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, ultimately leading to diastolic dysfunction (see review[185]). In the context of early DCM where LV structural remodeling is normally absent, the additive effect of hypertension may accelerate cardiomyocyte subcellular dysfunction. Jeong et al[186] have demonstrated that diastolic dysfunction in deoxycorticosterone acetate treated hypertensive mice is driven by oxidative stress modifications to cMyBP-C, which subsequently suppresses CB kinetics[186]. Further, chronic activation of ROCK plays a central role in most forms of hypertension and diabetic coronary dysfunction[87,102]. Thus, hypertension may exacerbate the development of cardiac dysfunction in early DCM by redox modifications of various sarcomeric proteins, disturbed CB dynamics and increased oxidative stress.

Obesity (in particular abdominal obesity) is a risk factor for the development cardiac dysfunction and heart failure, independent of diabetes[187]. Several metabolic and neurohormonal mechanisms have been postulated to contribute to obesity-induced cardiomyopathy (see review[188]). Of particular interest, is the interplay of the SNS and the RAAS, which occurs during obesity[189,190]. Classically, obesity leads to activation of the SNS, which in turn rapidly activates the production of renin from the renal juxtaglomerular apparatus as well as angiotensinogen from adipocytes and thus, promotes the excessive production of ANGII. Consequently, systemic hypertension ensues (reviewed in[189]). Given our previous discussion on hypertension-induced modulation of sarcomeric proteins leading to diastolic dysfunction[186], it is plausible that obesity may exacerbate DCM in patients via the promotion of systemic hypertension. On the other hand, obesity may also exacerbate DCM by directly increasing SNS outflow to the heart. In normotensive obese patients, increased LV mass correlates with elevated cardiac SNS activity[191]. Considering the hypertrophic and fibrotic actions of ANGII, elevated local RAAS activity driven by activation of the cardiac SNS could, in part, explain increased LV mass in obese patients. In addition, one study has shown that a high fat diet induced mitochondrial lesions and depressed mitochondrial density in the hearts of GK rats[192]. Therefore, obesity induced activation of the SNS in combination with diabetes may indeed exacerbate DCM.

Lastly, gender must also be considered as an additional risk factor for the development, progression and severity of DCM (reviewed in detail by[193]). Indeed, the Framingham Heart study revealed that diabetic women had twice the frequency of heart failure in comparison to diabetic men[22]. More recent clinical evidence suggests that although non-diabetic women appear to have more pronounced endothelium-mediated dilation (due to higher rates of nitric oxide production), T2DM abrogates these sex differences in vascular function[194]. Female mice also lose this vascular protection with T2DM[182]. Although, similar vascular dysfunction is observed in both sexes, the molecular mechanisms underlying this dysfunction in males appears to be elevated ROCK activity, however this does not appear to be the case in female mice[182]. The impact of sex on myocardial function in diabetes is less clear. Early in the time course of experimental T1DM, it appears that male rats are more vulnerable to cardiac dysfunction. Five to six weeks of STZ induced diabetes in rats caused greater prolongation of the rates of pressure development and decay in diabetic male rats in comparison to their female counterparts[195-197]. However, others have demonstrated that female rats after four weeks from STZ induction exhibit significantly lower MLC2 phosphorylation compared to diabetic males despite equivalent impairment in cardiac muscle tension development in both male and female diabetic rats[123]. Sex differences in the loss of cardiomyocytes may contribute to differential changes in contractile function in diabetes. Females respond to metabolic stresses with greater myocardial glycogen accumulation and elevated glycogen-induced autophagy than males[198,199]. Thus, the underlying mechanisms of sex differences in DCM require a great deal of research to appreciate which of the factors we have identified in this review differ between sexes and how the pathophysiology of diabetes might be compounded by other risk factors in females.

CONCLUSION

In summary, DCM is a progressive disease beginning with contractile dysfunction ahead of LV remodeling. A number of subcellular alterations to the cardiomyocyte contribute to contractile dysfunction in early DCM. While changes in Ca2+ handling protein expressions are evident and likely contribute to the prolongation of systole and relaxation, diminished intracellular Ca2+ transients appear to be associated only with advanced DCM. Diastolic LV dysfunction has its origins in changes in sarcomeric and other cytoskeletal proteins, both due to transcription and posttranslation changes. Upregulation of PKCβ2 activity is proposed as a central factor in the development of DCM, promoting the activity of both oxidative stress dependent and independent pathways to drive contractile dysfunction in early DCM. Independent of oxidative stress we suggest that hyperglycemia alters modulation of the sarcomeric thick-thin filaments through PKCβ2/ROCK activation. It is not known if any of these pathological changes in sarcomere function are exacerbated by other risk factors such as hypertension and obesity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge experiments performed at SPring-8 contributed to the formation of this reviews hypothesized mechanisms (proposal 2013B1759).

Footnotes

P- Reviewer: Kusmic C, Mu JS S- Editor: Gong XM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

Supported by The research funding from the International Synchrotron Access Program (AS/IA133) of the Australian Synchrotron (to Pearson JT); A Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (#E056, 26670413) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Sciences and Technology of Japan (to Shirai M).

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: August 28, 2014

First decision: December 17, 2014

Article in press: March 9, 2015

References

- 1.Whiting DR, Guariguata L, Weil C, Shaw J. IDF diabetes atlas: global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2011 and 2030. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2011;94:311–321. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2011.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laakso M, Kuusisto J. Insulin resistance and hyperglycaemia in cardiovascular disease development. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014;10:293–302. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2014.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilkinson-Berka JL, Miller AG. Update on the treatment of diabetic retinopathy. ScientificWorldJournal. 2008;8:98–120. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2008.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Molitch ME, DeFronzo RA, Franz MJ, Keane WF, Mogensen CE, Parving HH. Diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes Care. 2003;26 Suppl 1:S94–S98. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.2007.s94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mehra M, Merchant S, Gupta S, Potluri RC. Diabetic peripheral neuropathy: resource utilization and burden of illness. J Med Econ. 2014;17:637–645. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2014.928639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Candido R, Srivastava P, Cooper ME, Burrell LM. Diabetes mellitus: a cardiovascular disease. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2003;4:1088–1094. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Heerebeek L, Hamdani N, Handoko ML, Falcao-Pires I, Musters RJ, Kupreishvili K, Ijsselmuiden AJ, Schalkwijk CG, Bronzwaer JG, Diamant M, et al. Diastolic stiffness of the failing diabetic heart: importance of fibrosis, advanced glycation end products, and myocyte resting tension. Circulation. 2008;117:43–51. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.728550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Devereux RB, Roman MJ, Paranicas M, O’Grady MJ, Lee ET, Welty TK, Fabsitz RR, Robbins D, Rhoades ER, Howard BV. Impact of diabetes on cardiac structure and function: the strong heart study. Circulation. 2000;101:2271–2276. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.19.2271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Simone G, Mureddu GF, Vaccaro O, Greco R, Sacco M, Rivellese A, Contaldo F, Riccardi G. Cardiac abnormalities in type 1 diabetes. Ital Heart J. 2000;1:493–499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Vriese AS, Verbeuren TJ, Van de Voorde J, Lameire NH, Vanhoutte PM. Endothelial dysfunction in diabetes. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;130:963–974. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lumsden NG, Andrews KL, Bobadilla M, Moore XL, Sampson AK, Shaw JA, Mizrahi J, Kaye DM, Dart AM, Chin-Dusting JP. Endothelial dysfunction in patients with type 2 diabetes post acute coronary syndrome. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2013;10:368–374. doi: 10.1177/1479164113482593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Llauradó G, Ceperuelo-Mallafré V, Vilardell C, Simó R, Albert L, Berlanga E, Vendrell J, González-Clemente JM. Impaired endothelial function is not associated with arterial stiffness in adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Metab. 2013;39:355–362. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dimitropoulos G, Tahrani AA, Stevens MJ. Cardiac autonomic neuropathy in patients with diabetes mellitus. World J Diabetes. 2014;5:17–39. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v5.i1.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosengård-Bärlund M, Bernardi L, Fagerudd J, Mäntysaari M, Af Björkesten CG, Lindholm H, Forsblom C, Wadén J, Groop PH. Early autonomic dysfunction in type 1 diabetes: a reversible disorder? Diabetologia. 2009;52:1164–1172. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1340-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sacre JW, Franjic B, Jellis CL, Jenkins C, Coombes JS, Marwick TH. Association of cardiac autonomic neuropathy with subclinical myocardial dysfunction in type 2 diabetes. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;3:1207–1215. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2010.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kannel WB, McGee DL. Diabetes and cardiovascular disease. The Framingham study. JAMA. 1979;241:2035–2038. doi: 10.1001/jama.241.19.2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barr EL, Zimmet PZ, Welborn TA, Jolley D, Magliano DJ, Dunstan DW, Cameron AJ, Dwyer T, Taylor HR, Tonkin AM, et al. Risk of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in individuals with diabetes mellitus, impaired fasting glucose, and impaired glucose tolerance: the Australian Diabetes, Obesity, and Lifestyle Study (AusDiab) Circulation. 2007;116:151–157. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.685628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Battiprolu PK, Lopez-Crisosto C, Wang ZV, Nemchenko A, Lavandero S, Hill JA. Diabetic cardiomyopathy and metabolic remodeling of the heart. Life Sci. 2013;92:609–615. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2012.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boudina S, Abel ED. Diabetic cardiomyopathy revisited. Circulation. 2007;115:3213–3223. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.679597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poornima IG, Parikh P, Shannon RP. Diabetic cardiomyopathy: the search for a unifying hypothesis. Circ Res. 2006;98:596–605. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000207406.94146.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Preis SR, Pencina MJ, Hwang SJ, D’Agostino RB, Savage PJ, Levy D, Fox CS. Trends in cardiovascular disease risk factors in individuals with and without diabetes mellitus in the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2009;120:212–220. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.846519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kannel WB, Hjortland M, Castelli WP. Role of diabetes in congestive heart failure: the Framingham study. Am J Cardiol. 1974;34:29–34. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(74)90089-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rubler S, Dlugash J, Yuceoglu YZ, Kumral T, Branwood AW, Grishman A. New type of cardiomyopathy associated with diabetic glomerulosclerosis. Am J Cardiol. 1972;30:595–602. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(72)90595-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fang ZY, Prins JB, Marwick TH. Diabetic cardiomyopathy: evidence, mechanisms, and therapeutic implications. Endocr Rev. 2004;25:543–567. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fang ZY, Najos-Valencia O, Leano R, Marwick TH. Patients with early diabetic heart disease demonstrate a normal myocardial response to dobutamine. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:446–453. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00654-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Diamant M, Lamb HJ, Groeneveld Y, Endert EL, Smit JW, Bax JJ, Romijn JA, de Roos A, Radder JK. Diastolic dysfunction is associated with altered myocardial metabolism in asymptomatic normotensive patients with well-controlled type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:328–335. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00625-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borges GR, de Oliveira M, Salgado HC, Fazan R. Myocardial performance in conscious streptozotocin diabetic rats. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2006;5:26. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-5-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Litwin SE, Raya TE, Anderson PG, Daugherty S, Goldman S. Abnormal cardiac function in the streptozotocin-diabetic rat. Changes in active and passive properties of the left ventricle. J Clin Invest. 1990;86:481–488. doi: 10.1172/JCI114734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kelly DJ, Zhang Y, Connelly K, Cox AJ, Martin J, Krum H, Gilbert RE. Tranilast attenuates diastolic dysfunction and structural injury in experimental diabetic cardiomyopathy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H2860–H2869. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01167.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tan SM, Zhang Y, Wang B, Tan CY, Zammit SC, Williams SJ, Krum H, Kelly DJ. FT23, an orally active antifibrotic compound, attenuates structural and functional abnormalities in an experimental model of diabetic cardiomyopathy. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2012;39:650–656. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2012.05726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang Y, Edgley AJ, Cox AJ, Powell AK, Wang B, Kompa AR, Stapleton DI, Zammit SC, Williams SJ, Krum H, et al. FT011, a new anti-fibrotic drug, attenuates fibrosis and chronic heart failure in experimental diabetic cardiomyopathy. Eur J Heart Fail. 2012;14:549–562. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfs011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Campbell DJ, Somaratne JB, Jenkins AJ, Prior DL, Yii M, Kenny JF, Newcomb AE, Schalkwijk CG, Black MJ, Kelly DJ. Impact of type 2 diabetes and the metabolic syndrome on myocardial structure and microvasculature of men with coronary artery disease. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2011;10:80. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-10-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Freeman JS. A physiologic and pharmacological basis for implementation of incretin hormones in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85:S5–S14. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2010.0467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brownlee M. Biochemistry and molecular cell biology of diabetic complications. Nature. 2001;414:813–820. doi: 10.1038/414813a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cai L, Kang YJ. Oxidative stress and diabetic cardiomyopathy: a brief review. Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2001;1:181–193. doi: 10.1385/ct:1:3:181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Varga ZV, Giricz Z, Liaudet L, Haskó G, Ferdinandy P, Pacher P. Interplay of oxidative, nitrosative/nitrative stress, inflammation, cell death and autophagy in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1852:232–242. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huynh K, Bernardo BC, McMullen JR, Ritchie RH. Diabetic cardiomyopathy: mechanisms and new treatment strategies targeting antioxidant signaling pathways. Pharmacol Ther. 2014;142:375–415. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Connelly KA, Advani A, Advani SL, Zhang Y, Kim YM, Shen V, Thai K, Kelly DJ, Gilbert RE. Impaired cardiac anti-oxidant activity in diabetes: human and correlative experimental studies. Acta Diabetol. 2014;51:771–782. doi: 10.1007/s00592-014-0608-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Khong FL, Zhang Y, Edgley AJ, Qi W, Connelly KA, Woodman OL, Krum H, Kelly DJ. 3’,4’-Dihydroxyflavonol antioxidant attenuates diastolic dysfunction and cardiac remodeling in streptozotocin-induced diabetic m(Ren2)27 rats. PLoS One. 2011;6:e22777. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huynh K, Kiriazis H, Du XJ, Love JE, Jandeleit-Dahm KA, Forbes JM, McMullen JR, Ritchie RH. Coenzyme Q10 attenuates diastolic dysfunction, cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and cardiac fibrosis in the db/db mouse model of type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2012;55:1544–1553. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2495-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee JE, Yi CO, Jeon BT, Shin HJ, Kim SK, Jung TS, Choi JY, Roh GS. α-Lipoic acid attenuates cardiac fibrosis in Otsuka Long-Evans Tokushima Fatty rats. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2012;11:111. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-11-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maalouf RM, Eid AA, Gorin YC, Block K, Escobar GP, Bailey S, Abboud HE. Nox4-derived reactive oxygen species mediate cardiomyocyte injury in early type 1 diabetes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2012;302:C597–C604. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00331.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cheng X, Xia Z, Leo JM, Pang CC. The effect of N-acetylcysteine on cardiac contractility to dobutamine in rats with streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;519:118–126. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gao X, Xu Y, Xu B, Liu Y, Cai J, Liu HM, Lei S, Zhong YQ, Irwin MG, Xia Z. Allopurinol attenuates left ventricular dysfunction in rats with early stages of streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2012;28:409–417. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Steinberg SF. Oxidative stress and sarcomeric proteins. Circ Res. 2013;112:393–405. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.300496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sumandea MP, Steinberg SF. Redox signaling and cardiac sarcomeres. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:9921–9927. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R110.175489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Privratsky JR, Wold LE, Sowers JR, Quinn MT, Ren J. AT1 blockade prevents glucose-induced cardiac dysfunction in ventricular myocytes: role of the AT1 receptor and NADPH oxidase. Hypertension. 2003;42:206–212. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000082814.62655.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maeda Y, Inoguchi T, Takei R, Hendarto H, Ide M, Inoue T, Kobayashi K, Urata H, Nishiyama A, Takayanagi R. Chymase inhibition prevents myocardial fibrosis through the attenuation of NOX4-associated oxidative stress in diabetic hamsters. J Diabetes Investig. 2012;3:354–361. doi: 10.1111/j.2040-1124.2012.00202.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang Z, Zhang Y, Guo J, Jin K, Li J, Guo X, Scott GI, Zheng Q, Ren J. Inhibition of protein kinase C βII isoform rescues glucose toxicity-induced cardiomyocyte contractile dysfunction: role of mitochondria. Life Sci. 2013;93:116–124. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2013.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang L, Huang D, Shen D, Zhang C, Ma Y, Babcock SA, Chen B, Ren J. Inhibition of protein kinase C βII isoform ameliorates methylglyoxal advanced glycation endproduct-induced cardiomyocyte contractile dysfunction. Life Sci. 2014;94:83–91. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2013.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kobori H, Kamiyama M, Harrison-Bernard LM, Navar LG. Cardinal role of the intrarenal renin-angiotensin system in the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy. J Investig Med. 2013;61:256–264. doi: 10.231/JIM.0b013e31827c28bb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schmieder RE, Hilgers KF, Schlaich MP, Schmidt BM. Renin-angiotensin system and cardiovascular risk. Lancet. 2007;369:1208–1219. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60242-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kumar R, Yong QC, Thomas CM, Baker KM. Intracardiac intracellular angiotensin system in diabetes. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2012;302:R510–R517. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00512.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cassis LA. Downregulation of the renin-angiotensin system in streptozotocin-diabetic rats. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:E105–E109. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1992.262.1.E105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Giacchetti G, Sechi LA, Rilli S, Carey RM. The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, glucose metabolism and diabetes. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2005;16:120–126. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dostal DE, Baker KM. The cardiac renin-angiotensin system: conceptual, or a regulator of cardiac function? Circ Res. 1999;85:643–650. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.7.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wong TC, Piehler KM, Kang IA, Kadakkal A, Kellman P, Schwartzman DS, Mulukutla SR, Simon MA, Shroff SG, Kuller LH, et al. Myocardial extracellular volume fraction quantified by cardiovascular magnetic resonance is increased in diabetes and associated with mortality and incident heart failure admission. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:657–664. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dong B, Yu QT, Dai HY, Gao YY, Zhou ZL, Zhang L, Jiang H, Gao F, Li SY, Zhang YH, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 overexpression improves left ventricular remodeling and function in a rat model of diabetic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:739–747. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.09.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kajstura J, Fiordaliso F, Andreoli AM, Li B, Chimenti S, Medow MS, Limana F, Nadal-Ginard B, Leri A, Anversa P. IGF-1 overexpression inhibits the development of diabetic cardiomyopathy and angiotensin II-mediated oxidative stress. Diabetes. 2001;50:1414–1424. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.6.1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liu X, Suzuki H, Sethi R, Tappia PS, Takeda N, Dhalla NS. Blockade of the renin-angiotensin system attenuates sarcolemma and sarcoplasmic reticulum remodeling in chronic diabetes. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1084:141–154. doi: 10.1196/annals.1372.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Westermann D, Rutschow S, Jäger S, Linderer A, Anker S, Riad A, Unger T, Schultheiss HP, Pauschinger M, Tschöpe C. Contributions of inflammation and cardiac matrix metalloproteinase activity to cardiac failure in diabetic cardiomyopathy: the role of angiotensin type 1 receptor antagonism. Diabetes. 2007;56:641–646. doi: 10.2337/db06-1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mori J, Patel VB, Abo Alrob O, Basu R, Altamimi T, Desaulniers J, Wagg CS, Kassiri Z, Lopaschuk GD, Oudit GY. Angiotensin 1-7 ameliorates diabetic cardiomyopathy and diastolic dysfunction in db/db mice by reducing lipotoxicity and inflammation. Circ Heart Fail. 2014;7:327–339. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.113.000672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Guo Z, Zheng C, Qin Z, Wei P. Effect of telmisartan on the expression of cardiac adiponectin and its receptor 1 in type 2 diabetic rats. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2011;63:87–94. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.2010.01157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Machackova J, Liu X, Lukas A, Dhalla NS. Renin-angiotensin blockade attenuates cardiac myofibrillar remodelling in chronic diabetes. Mol Cell Biochem. 2004;261:271–278. doi: 10.1023/b:mcbi.0000028765.89855.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Connelly KA, Kelly DJ, Zhang Y, Prior DL, Martin J, Cox AJ, Thai K, Feneley MP, Tsoporis J, White KE, et al. Functional, structural and molecular aspects of diastolic heart failure in the diabetic (mRen-2)27 rat. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;76:280–291. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Keidar S, Kaplan M, Gamliel-Lazarovich A. ACE2 of the heart: From angiotensin I to angiotensin (1-7) Cardiovasc Res. 2007;73:463–469. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Greenberg B, Cowling RT. An ACE for my sweet heart. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:748–750. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tikellis C, Bernardi S, Burns WC. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a key modulator of the renin-angiotensin system in cardiovascular and renal disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2011;20:62–68. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e328341164a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Singh K, Singh T, Sharma PL. Beneficial effects of angiotensin (1-7) in diabetic rats with cardiomyopathy. Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis. 2011;5:159–167. doi: 10.1177/1753944711409281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vázquez-Medina JP, Popovich I, Thorwald MA, Viscarra JA, Rodriguez R, Sonanez-Organis JG, Lam L, Peti-Peterdi J, Nakano D, Nishiyama A, et al. Angiotensin receptor-mediated oxidative stress is associated with impaired cardiac redox signaling and mitochondrial function in insulin-resistant rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2013;305:H599–H607. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00101.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Huisamen B, Pêrel SJ, Friedrich SO, Salie R, Strijdom H, Lochner A. ANG II type I receptor antagonism improved nitric oxide production and enhanced eNOS and PKB/Akt expression in hearts from a rat model of insulin resistance. Mol Cell Biochem. 2011;349:21–31. doi: 10.1007/s11010-010-0656-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Singh VP, Le B, Khode R, Baker KM, Kumar R. Intracellular angiotensin II production in diabetic rats is correlated with cardiomyocyte apoptosis, oxidative stress, and cardiac fibrosis. Diabetes. 2008;57:3297–3306. doi: 10.2337/db08-0805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yaras N, Bilginoglu A, Vassort G, Turan B. Restoration of diabetes-induced abnormal local Ca2+ release in cardiomyocytes by angiotensin II receptor blockade. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H912–H920. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00824.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yugandhar VG, Clark MA. Angiotensin III: a physiological relevant peptide of the renin angiotensin system. Peptides. 2013;46:26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2013.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Geraldes P, King GL. Activation of protein kinase C isoforms and its impact on diabetic complications. Circ Res. 2010;106:1319–1331. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.217117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Koya D, King GL. Protein kinase C activation and the development of diabetic complications. Diabetes. 1998;47:859–866. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.47.6.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shin HG, Barnett JV, Chang P, Reddy S, Drinkwater DC, Pierson RN, Wiley RG, Murray KT. Molecular heterogeneity of protein kinase C expression in human ventricle. Cardiovasc Res. 2000;48:285–299. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00185-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Connelly KA, Kelly DJ, Zhang Y, Prior DL, Advani A, Cox AJ, Thai K, Krum H, Gilbert RE. Inhibition of protein kinase C-beta by ruboxistaurin preserves cardiac function and reduces extracellular matrix production in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Circ Heart Fail. 2009;2:129–137. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.108.765750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Way KJ, Isshiki K, Suzuma K, Yokota T, Zvagelsky D, Schoen FJ, Sandusky GE, Pechous PA, Vlahos CJ, Wakasaki H, et al. Expression of connective tissue growth factor is increased in injured myocardium associated with protein kinase C beta2 activation and diabetes. Diabetes. 2002;51:2709–2718. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.9.2709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Xia Z, Kuo KH, Nagareddy PR, Wang F, Guo Z, Guo T, Jiang J, McNeill JH. N-acetylcysteine attenuates PKCbeta2 overexpression and myocardial hypertrophy in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;73:770–782. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wang M, Zhang WB, Zhu JH, Fu GS, Zhou BQ. Breviscapine ameliorates hypertrophy of cardiomyocytes induced by high glucose in diabetic rats via the PKC signaling pathway. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2009;30:1081–1091. doi: 10.1038/aps.2009.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Latha R, Shanthi P, Sachdanandam P. Kalpaamruthaa modulates oxidative stress in cardiovascular complication associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus through PKC-β/Akt signaling. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2013;91:901–912. doi: 10.1139/cjpp-2012-0443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Guo M, Wu MH, Korompai F, Yuan SY. Upregulation of PKC genes and isozymes in cardiovascular tissues during early stages of experimental diabetes. Physiol Genomics. 2003;12:139–146. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00125.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Inoguchi T, Battan R, Handler E, Sportsman JR, Heath W, King GL. Preferential elevation of protein kinase C isoform beta II and diacylglycerol levels in the aorta and heart of diabetic rats: differential reversibility to glycemic control by islet cell transplantation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:11059–11063. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.11059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Liu Y, Lei S, Gao X, Mao X, Wang T, Wong GT, Vanhoutte PM, Irwin MG, Xia Z. PKCβ inhibition with ruboxistaurin reduces oxidative stress and attenuates left ventricular hypertrophy and dysfunction in rats with streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Clin Sci (Lond) 2012;122:161–173. doi: 10.1042/CS20110176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Shimokawa H, Rashid M. Development of Rho-kinase inhibitors for cardiovascular medicine. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28:296–302. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Noma K, Oyama N, Liao JK. Physiological role of ROCKs in the cardiovascular system. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2006;290:C661–C668. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00459.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kureishi Y, Kobayashi S, Amano M, Kimura K, Kanaide H, Nakano T, Kaibuchi K, Ito M. Rho-associated kinase directly induces smooth muscle contraction through myosin light chain phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:12257–12260. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.19.12257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Pulinilkunnil T, An D, Ghosh S, Qi D, Kewalramani G, Yuen G, Virk N, Abrahani A, Rodrigues B. Lysophosphatidic acid-mediated augmentation of cardiomyocyte lipoprotein lipase involves actin cytoskeleton reorganization. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H2802–H2810. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01162.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Akahori H, Tsujino T, Naito Y, Matsumoto M, Sasaki N, Iwasaku T, Eguchi A, Sawada H, Hirotani S, Masuyama T. Atorvastatin ameliorates cardiac fibrosis and improves left ventricular diastolic function in hypertensive diastolic heart failure model rats. J Hypertens. 2014;32:1534–1541; discussion 1541. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Fukui S, Fukumoto Y, Suzuki J, Saji K, Nawata J, Tawara S, Shinozaki T, Kagaya Y, Shimokawa H. Long-term inhibition of Rho-kinase ameliorates diastolic heart failure in hypertensive rats. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2008;51:317–326. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e31816533b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kobayashi N, Horinaka S, Mita S, Nakano S, Honda T, Yoshida K, Kobayashi T, Matsuoka H. Critical role of Rho-kinase pathway for cardiac performance and remodeling in failing rat hearts. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;55:757–767. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00457-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Satoh S, Ueda Y, Koyanagi M, Kadokami T, Sugano M, Yoshikawa Y, Makino N. Chronic inhibition of Rho kinase blunts the process of left ventricular hypertrophy leading to cardiac contractile dysfunction in hypertension-induced heart failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2003;35:59–70. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(02)00278-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Phrommintikul A, Tran L, Kompa A, Wang B, Adrahtas A, Cantwell D, Kelly DJ, Krum H. Effects of a Rho kinase inhibitor on pressure overload induced cardiac hypertrophy and associated diastolic dysfunction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294:H1804–H1814. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01078.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hattori T, Shimokawa H, Higashi M, Hiroki J, Mukai Y, Tsutsui H, Kaibuchi K, Takeshita A. Long-term inhibition of Rho-kinase suppresses left ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction in mice. Circulation. 2004;109:2234–2239. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000127939.16111.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]