Abstract

Human cysticercosis most commonly affects the subcutaneous tissues, skeletal muscles, lungs, brain, eyes, liver and, rarely, the heart, thyroid and pancreas. Owing to vague clinical presentation and unfamiliarity of clinicians with this entity, it is difficult to diagnosis when seen as an isolated cyst. We present a case of a 16-year-old boy who presented with an upper abdominal lump and jaundice. Ultrasonography (USG) and MRI of the abdomen were carried out, which revealed a cystic mass (8.5×7×7 cm) in the pancreas. No evidence of solid component or papillary projections was noted within the lesion. Tumour markers carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and cancer antigen (CA 19-9) were normal. Fine needle aspiration cytology was performed, which revealed the presence of cysticercus larvae, along with a foreign body giant cell reaction. The patient was treated with therapeutic aspiration and antihelminthic therapy. Since then, he has been symptom free and under regular follow-up for the last 1 year. A diagnosis of cysticercal cyst at atypical sites is very rare and depends mainly on histopathological examination, which, along with USG and MRI, can give an accurate analysis. These cysts can be very well treated non-surgically with antihelminthics and aspiration.

Background

Cysticercosis in humans is infection from the larval form (cysticercus cellulosae) of the pork tapeworm Taenia solium.1 The occurrence of cysts in humans, in order of frequency, is: in the central nervous system, vitreous humour of the eye, striated muscle, subcutaneous tissue and, rarely, in other tissues.2 Most muscular disease is associated with central nervous system involvement, presence of multiple muscular cysts or both. There is a paucity of literature regarding isolated pancreatic cysticercal cysts.

Case presentation

A 16-year-old boy in India, belonging to a low socioeconomic strata, presented with abdominal pain and swelling in the upper abdomen for a period of 2 months along with jaundice, which was progressively increasing. There was no history of seizure disorder or muscular pain. On examination, a single 7×6 cm lump was present in the epigastrium and extending into the umbilical region; the lump was soft to firm in consistency, with a smooth surface and well-defined margins.

Laboratory findings revealed eosinophilia (18%, absolute eosinophil count of 1360) and elevated bilirubin levels; the remaining blood investigations were normal, including tumour markers carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and cancer antigen (CA) 19-9. Routine stool examination did not reveal parasitic infestation.

USG revealed a large 7.6×7×9 cm cystic lesion mass seen anterior to the body of the pancreas, showing multiple internal septations with a wall thickness of approximately 5 mm with dilated common bile duct (CBD).

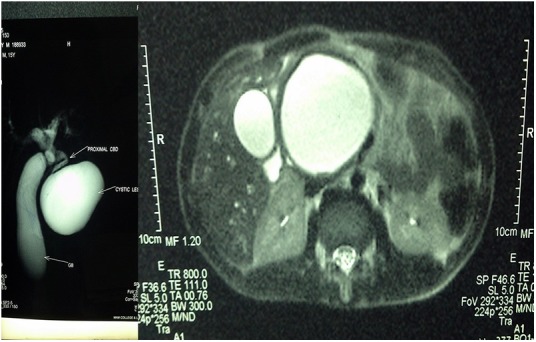

MRI/MR cholangiopancreatography (figure 1) was suggestive of a well-defined encapsulated cystic lesion measuring 8.5×7×7 cm, in relation to the head and neck of the pancreas, showing hypointense signals on T1-weighted images (T1W1) and hyperintense signals on T2-weighted images (T2W1). The lesion showed no significant enhancement and was seen to cause displacement of the pancreatic head posteriorly and inferiorly, causing mass effect in the suprapancreatic section of the CBD, which was dilated (1.2 cm in diameter), with evidence of consequent marked distension of the gallbladder and intrahepatic biliary radicles. The distal intrapancreatic section of the CBD was narrow and draped along the right lateral aspect of the cyst. No evidence of solid component or papillary projections was noted within the lesion. Features were suggestive of cystic lesion of the pancreas causing obstructive biliopathy.

Figure 1.

MRI of the abdomen showing a cystic lesion in the pancreas.

MRI of the brain was suggestive of a normal study.

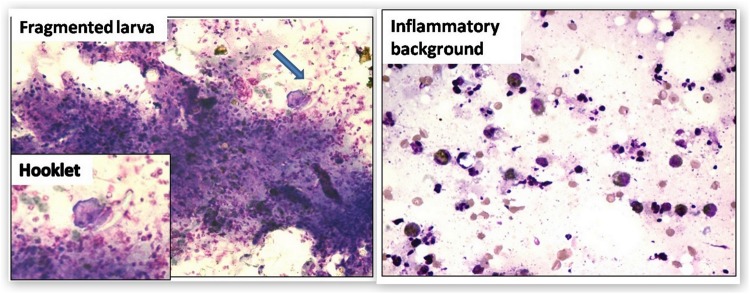

Fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) (figure 2) was performed from the swelling and was suggestive of occasional fragmented larvae of Cysticercosis with inflammatory background.

Figure 2.

Fine needle aspiration cytology of cystic swelling showing fragmented larva of cysticercosis, with inflammatory background.

The cystic fluid was clear and serous in nature, tumour markers CA 19-9 and CEA were not elevated in the cyst fluids, and cyst fluid amylase and lipase levels were normal.

The patient was treated with albendazole 15 mg/kg body weight for 6 weeks and therapeutic aspiration was carried out. There was a significant reduction in the bilirubin level and lump size, and the lump gradually disappeared. The patient is currently asymptomatic and has been under regular follow-up for the last 1 year, and a repeat USG study proved to be normal.

Investigations

Laboratory investigations showed eosinophilia with elevated bilirubin and alkaline phosphate levels (suggestive of obstructive jaundice).

Features on USG of the abdomen was suggestive of a large 7.6×7×9 cm cystic lesion mass seen anterior to the body of the pancreas, showing multiple internal septations with a wall thickness of approximately 5 mm.

MRI/MRCP: There was evidence of a well-defined encapsulated cystic lesion measuring ∼8.5×7×7 cm in relation to the head and neck of the pancreas, showing hypointense signals on T1W1 and hyperintense signals on T2W1. The lesion showed no significant enhancement and was seen to cause displacement of the pancreatic head posteriorly and inferiorly. The cyst caused a mass effect in the suprapancreatic section of the CBD, which was dilated (1.2 cm in diameter), with evidence of consequent marked distension of the gallbladder and intrahepatic biliary radicles. The distal intrapancreatic section of the CBD was narrow and draped along the right lateral aspect of the cyst. No evidence of solid component or papillary projections was noted within the lesion. USG correlation revealed a well-defined thick wall (∼4 cm) with fine internal septations and no internal vascularity. Features were suggestive of cystic lesion of the pancreas causing obstructive biliopathy.

FNAC was suggestive of occasional fragmented larvae of cysticercosis with inflammatory background.

The cystic fluid was clear and serous in nature, tumour markers CA 19-9 and CEA were not elevated in the cyst fluids, and cyst fluid amylase and lipase levels were normal.

Differential diagnosis

Isolated pancreatic cysticercal cyst with obstructive biliopathy.

Treatment

The patient was treated with albendazole 15 mg/kg body weight for 6 weeks and therapeutic aspiration was performed.

Outcome and follow-up

There was a significant reduction in the bilirubin level and lump size, and the lump gradually disappeared. The patient was discharged from the hospital after making sure he had no side effects. He is currently asymptomatic and has been under regular follow-up for the last 1 year, and a repeat USG proved to be normal.

Discussion

Human cysticercosis is caused by the dissemination of the embryo of T. solium from the intestine, via the hepatoportal system, to the tissues and organs of the body. Ingested eggs pass into the bloodstream, disseminate into various organs, and form cysts, which characterise cysticercosis.3 4 T. solium is present worldwide, but is most prevalent in Mexico, Africa, South-East Asia, Eastern Europe and South America.4 As early as in 1912, widespread dissemination of cysticerci throughout the human body was reported by British Army medical officers stationed in India.5 Widespread dissemination of the cysticerci can result in the involvement of almost any organ in the body. Most commonly affected organs are the subcutaneous tissues, skeletal muscles, lungs, brain, eyes, liver and, occasionally, the heart. The clinical features depend on the location of cyst, cyst burden and host reaction.6

Humans are the only definitive host for this parasite. When raw or undercooked infected meat is ingested, stomach enzymes lyses the outer shell of the parasite cyst, leaving the scolex (head) behind. The scolex has suckers and hooks (rostellum) that aid in attachment to the intestinal wall. Once the parasite has attached itself to the intestinal wall, the scolex proliferates and, over the next 2 months, becomes an adult tapeworm; these tapeworms can survive 4 years within the human intestines. They may reach 2–7 m in length. Adult tapeworms produce eggs (proglottids), which mature, become gravid, detach from the tapeworm and migrate to the anus or are passed in the stool. When pigs ingest the eggs from infected soil, the cycle begins anew.7 8 Normally, pigs are intermediate hosts in the life cycle of these cystodes. However, though rarely, man acts as intermediate host and that manifests as cysticercosis. It is transmitted to humans by ingestion of eggs from contaminated water and vegetables, or, very rarely, by internal regurgitation of eggs into the stomach due to reverse peristalsis, when the intestine harbours a gravid worm.9 10 The eggs lyse in the stomach, releasing oncospheres in the small intestine, which penetrate the bowel mucosa and enter the bloodstream to reach various tissues such as those of the brain, muscles and eyes, and subcutaneous and other tissue. In these organs, they develop to form cysticercus cellulosae, which are the encysted larval forms of T. solium. In humans, these can remain viable in this stage for as long as 10 years.11

Cystic lesions of the pancreas (CLPs) have a heterogeneous appearance on imaging and frequently share many overlapping morphological features. Although endoscopic ultrasound with fine-needle aspirate (EUSFNA) has been increasingly demonstrated to improve the preoperative diagnosis of CLP, the widespread adoption of this modality has been restricted by its invasiveness and the limited availability of technical expertise. Furthermore, EUS has an accuracy of no greater than 80%.12–14

When evaluating a cystic lesion of the pancreas, the viscosity, pancreatic enzyme levels and tumour marker expression in the fluid can all aid in refining the differential diagnosis. Non-mucinous cyst fluid has a lower relative viscosity compared to serum, whereas mucinous cysts consistently have a higher relative viscosity. In the distinction between pseudocysts and neoplastic cysts, three enzyme tests have demonstrated use. Fluid amylase, lipase and leucocyte esterase levels tend to be high in pseudocysts and low in neoplastic cysts. A variety of tumour markers, such as CEA, CA125, CA72-4, CA19–9 and CA15-3, have been studied for their value in discriminating among the major types of cystic neoplasms, particularly between mucinous and non mucinous cysts. Of these, the CEA level is the most accurate.15 16

Although tumour marker levels tend to be higher in malignant cystic neoplasms (both ductal adenocarcinoma with cystic degeneration and mucinous cystadenocarcinoma), the distinction between benign and malignant mucinous cysts cannot be made on the results of this test alone.

Blood counts are not helpful apart from assessing the elevation of eosinophils, which are occasionally seen. However, raised eosinophils are only a vague indicator of helminthic infestation.

CT scans and MRI are useful in anatomical localisation of the cysts. An MRI is more sensitive than a CT, as it identifies scolex and live cysts in cisternal spaces and ventricles, and identifies the response to treatment.3 6

On MRI, cysticercosis lesions appear hyperintense, with well-defined edges that show a hypointense eccentric nodule within, representing the dead parasite’s head, which is called the scolex. The presence of a scolex in a cystic lesion usually suggests the diagnosis of cysticercosis.17

FNAC also plays an important role in diagnosing cysticercosis, but it is limited by the varying cytomorphological features of cysticercosis.18 The host tissue response is extremely variable and ranges from an insignificant response to a markedly cellular response, which consists of epithelioid cell granulomas and histiocytes.

Sendai Consensus Guidelines and Fukuoka Consensus Guidelines were designed specifically for the management of cystic mucinous neoplasms such as mucinous cystic neoplasms (MCNs) and intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs), and a major assumption in their formulation was that all types, namely, main duct (MD) and mixed duct types (MT), as well as MD/MT-IPMNs and MCNs, should be resected, whereas selected non-malignant branch duct BD-IPMNs could be observed. However, the clinical application of these guidelines remains limited, especially in the initial triage of patients.

This is mainly because a definitive preoperative diagnosis of an MCN or IPMN is frequently impossible to make, especially via cross-sectional imaging features alone. It is widely recognised that it is not only difficult to distinguish between MCNs and IPMNs, but also difficult to do so between mucinous CLPs and other CLPs, such as serous cystic neoplasms or pseudocysts.19 20

There is a paucity of literature regarding the management of isolated pancreatic cysticercal cysts.

Management includes symptomatic treatment, antihelminthic drugs and therapeutic aspiration.

Antihelminthic drugs praziquantel (10–15 mg/kg/day for 6–21 days) and albendazole (15 mg/kg/day for 30 days) are indicated, as they help by reducing the parasite burden. These drugs hasten the death of the cysts; cyst death may occur even in the absence of such treatment.

Learning points.

Isolated pancreatic cysticercal cysts are extremely rare and often difficult to diagnose.

CT scans and MRI are useful in anatomical localisation of the cysts and fine needle aspiration cytology plays an important role in diagnosing cysticercosis.

These patients can be managed non-surgically with antihelminthics and therapeutic aspiration.

Footnotes

Contributors: This unusual case was diagnosed and managed by SN and RS. The article was researched and written by RS and edited by SN.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Evans CAW, Garcia HH, Gilman RH. Cysticercosis. In: Strickland GT, ed Hunter's tropical medicine. 8th edn Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders Co, 2000:862. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mittal A, Das D, Iyer N et al. Masseter cysticercosis—a rare case diagnosed on ultrasound. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2008;37:113–16. 10.1259/dmfr/31885135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhalla A, Sood A, Sachdev A et al. Disseminated cysticercosis: a case report and review of literature. J Med Case Rep 2008;2:137 10.1186/1752-1947-2-137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jain BK, Sankhe SS, Agrawal MD et al. Disseminated cysticercosis with pulmonary and cardiac involvement. Indian J Radiol Imaging 2010;20:310–13. 10.4103/0971-3026.73532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krishnaswami CS. Case of cysticercuscellulose. Ind Med Gaz 1912;27:43–4. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumar A, Bhagwani DK, Sharma RK et al. Disseminated cysticercosis. Indian Pediatr 1996;33:337–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamashita P, Kelsey J, Henderson SO. Subcutaneous cysticercosis. J Emerg Med 1998;16:583–6. 10.1016/S0736-4679(98)00039-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Botero D, Tonawitz HB, Weiss LM et al. Taeniasis and cysticercosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am 1993;7:683–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horton J. Biology of tapeworm disease. Lancet 1996;348:481 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)64584-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Del Brutto OA, Sotelo J. Neurocysticercosis: an update. Rev Infect Dis 1988;10:1075–87. 10.1093/clinids/10.6.1075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Despommier DD. Tapeworm infection: the long and the short of it. N Engl J Med 1992;327:727–8. 10.1056/NEJM199209033271011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goh BK, Tan YM, Thng CH et al. How useful are clinical, biochemical, and cross-sectional imaging features in predicting potentially malignant and malignant cystic lesions of the pancreas? Results from a single institution experience with 220 surgically treated patients. J Am Coll Surg 2008;206:17–27. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.06.312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sawhney MS, Al-Bashir S, Cury MS et al. International consensus guidelines for surgical resection of mucinous neoplasms cannot be applied to all cystic lesions of the pancreas. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;7:1373–6. 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.06.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brugge WR. Evaluation of pancreatic cystic lesions with EUS. Gastrointest Endosc 2004;59:698–707. 10.1016/S0016-5107(04)00175-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van der Waaij LA, van Dullemen HM, Porte RJ. Cyst fluid analysis in the differential diagnosis of pancreatic cystic lesions: a pooled analysis. Gastrointest Endosc 2005;62:383–9. 10.1016/S0016-5107(05)01581-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brugge WR, Lewandrowski K, Lee-Lewandrowski E et al. Diagnosis of pancreatic cystic neoplasms: a report of the cooperative pancreatic cyst study. Gastroenterology 2004;126:1330–6. 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Del Brutto OH, Rajshekhar V, White AC et al. Proposed diagnostic criteria for neurocysticercosis. Neurology 2001;57:177–83. 10.1212/WNL.57.2.177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sahai K, Kapila K, Verma K. Parasites in fine needle breast aspirates Assessment of the host tissue response. Postgrad Med J 2002;78:165–7. 10.1136/pmj.78.917.165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanaka M, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Adsay V et al. International consensus guidelines 2012 for the management of IPMN and MCN of the pancreas. Pancreatology 2012;12:183–97. 10.1016/j.pan.2012.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goh BK, Tan YM, Chung YF et al. A review of mucinous cystic neoplasms defined by ovarian type stroma: clinicopahologic feature of 344 patients. World J Surg 2006;30:2236–45. 10.1007/s00268-006-0126-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]