Abstract

Introduction

Depression is commonly comorbid with chronic physical illnesses and is associated with a range of adverse clinical outcomes. Currently, the literature on the role of depression in determining the course and outcome of tuberculosis (TB) is very limited.

Aim

Our aim is to examine the relationship between depression and TB among people newly diagnosed and accessing care for TB in a rural Ethiopian setting. Our objectives are to investigate: the prevalence and determinants of probable depression, the role of depression in influencing pathways to treatment of TB, the incidence of depression during treatment, the impact of anti-TB treatment on the prognosis of depression and the impact of depression on the outcomes of TB treatment.

Methods and analysis

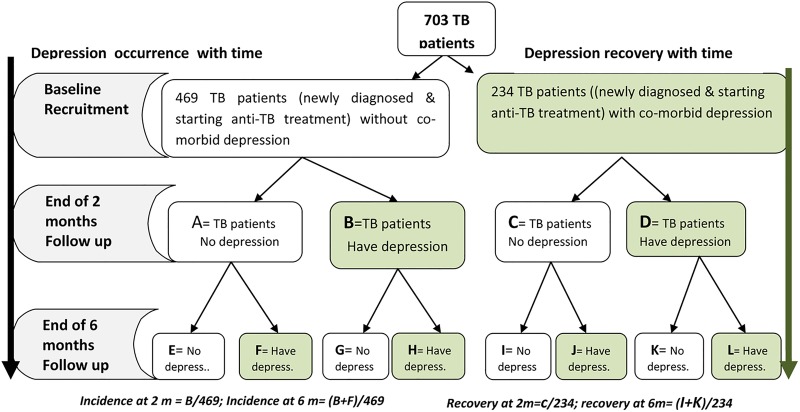

We will use a prospective cohort design. 703 newly diagnosed cases of TB (469 without depression and 234 with depression) will be consecutively recruited from primary care health centres. Data collection will take place at baseline, 2 and 6 months after treatment initiation. The primary exposure variable is probable depression measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9. Outcome variables include: pathways to treatment, classical outcomes for anti-TB treatment quality of life and disability. Descriptive statistics, logistic regression and multilevel mixed-effect analysis will be used to test the study hypotheses.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval has been obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the College of Health Sciences, Addis Ababa University. Findings will be disseminated through scientific publications, conference presentations, community meetings and policy briefs.

Anticipated impact

Findings will contribute to a sparse evidence base on comorbidity of depression and TB. We hope the dissemination of findings will raise awareness of comorbidity among clinicians and service providers, and contribute to ongoing debates regarding the delivery of mental healthcare in primary care in Ethiopia.

Keywords: EPIDEMIOLOGY, PRIMARY CARE

Introduction

The relationship between depression and chronic physical illnesses is bidirectional. Comorbidity is associated with a range of adverse outcomes, including functional impairment, increased medical costs, poor adherence to medication and self-care regimens, increased medical symptom burden and increased mortality.1 2 Individually, depression3 4 and tuberculosis (TB)4 5 are recognised as important public health concerns, contributing to 2.5–2.0% of disability adjusted life years (DALYs) worldwide in 2010, respectively.6 In Ethiopia, the prevalence of depression was found to be 9.1% in a nationally representative sample;7 and in a population-based survey carried out in southern Ethiopia, depression was found to be the seventh leading cause of disease burden contributing to 6.5% of the DALYs in 1998.8 TB is a key public health concern in Ethiopia: in 2009/2010, it was the second most important cause of death.9 Ethiopia is ranked seventh among the 22 high-burden countries that account for 81% of all cases of TB and 80% of all TB deaths worldwide. Ethiopia is also one of 27 countries identified as having a high prevalence of multidrug resistant TB (MDR-TB). The burden of MDR-TB in these countries accounts for 86% of cases worldwide.9 10

Evidence from cross-sectional studies (some of which were carried out in hospital settings in African countries) indicate a very high prevalence of comorbid depression (ranging from 10% to 52%) among patients with TB.11–18 However, because longitudinal research on TB and depression is scarce, the nature of the relationship and trajectory of comorbidity is little understood. Most high-quality studies examining the prevalence and impact of comorbid depression in the context of chronic physical diseases were conducted among people with diabetes mellitus, ischaemic heart diseases, cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases.1 2 19 The extent to which the impact of comorbid depression in the context of TB is comparable to depression comorbid with other non-communicable chronic conditions is unclear. TB is a curable condition with relatively shorter treatment duration and therefore has the potential for more favourable outcomes than many non-communicable chronic diseases.16 However, TB remains a debilitating, stigmatised communicable disease requiring complex and aggressive treatment. Similar to depression in the context of HIV/AIDS, the potential for depression to impair adherence to complex TB medication regimens is not only problematic in terms of individual patient outcomes but also poses a threat to public health through the potential for the development of multidrug resistance.20 For now, the literature on the role of depression in determining TB treatment outcomes (treatment default, interruption, completion, failure, death) and treatment pathways (routes of help seeking for TB treatment within modern or traditional care systems) is very limited.

Possible mechanisms for the association between TB and depression

It is likely that pathways for associations between TB and depression are complex and multidirectional. Biological and psychosocial pathways may be responsible for observed associations. The extent to which different pathways contribute to the burden of comorbidity is currently unclear. For example, some researchers have suggested that patients with TB may develop depression as a result of chronic infection or related psychosocioeconomic stressors21 or due to the effects of treatment such as isoniazid.22 An alternative pathway may be that TB is contracted as a result of compromised immunity and neglected self-care associated with depression.23 Finally, there is evidence to suggest that TB and depression may share risk factors.2 23 24

Immunological responses have been implicated in the association between chronic disease and depression. Chronic infectious conditions may lead to overproduction of proinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin 6, which facilitate cascades of endocrine reactions that are suggested to result in depressive symptoms.24 However, there is growing evidence that depression itself enhances the production of proinflammatory cytokines and directly minimises the immunological competence of patients by downregulating cellular and humoral responses.1 2 23 24 In addition, in chronic pulmonary conditions with hypoxia, the hypoxic condition can act directly to make patients anxious and depressed. Likewise, general factors associated with chronic disease such as weight loss, fatigue, psychological and social losses may trigger depressive reactions.21

There is a consensus among experts that people who have chronic diseases and comorbid depression can benefit from treatments for depression, including treatment with antidepressants.1 14 19 25 26 If depression in the context of TB is associated with a biological pathway or is a response to the burden of chronic infection, it might be expected that treatment of TB may lead to reduced symptoms of depression, perhaps without the need for further intervention. As intervention for depression among patients with TB is likely to incur additional costs, pill burden and potential stress, it is important to understand to what extent TB treatment alone may be an effective intervention for depressive symptoms. In addition, anti-TB medications, especially isoniazid, the first of the monoamine oxidase inhibitors to be considered for the treatment of mental disorders in the 1950s,27 and now a core drug in anti-TB treatment,28 may have significant interactions with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors,27 which are WHO-recommended drugs for the treatment of depression in the mental health gap action programme (mhGAP) guideline.29 The integration of mental healthcare into primary care settings is currently being scaled up in Ethiopia,29 30 with depression as one of the priority disorders. The results of the proposed study will help to inform the targeting and delivery of mental health services in the context of TB in Ethiopia.

Aims and objectives

Our overall aim is to carry out a longitudinal study of depression in the context of TB, in order to determine the impact of comorbid depression on TB outcomes. In this way, we hope to contribute to a sparse evidence base that lacks high-quality evidence from African countries, where the highest rates of cases and deaths relative to population size occur.31 Our study has five objectives:

To determine the prevalence of depression in people with TB at the time of anti-TB treatment initiation,

To assess factors associated with baseline depression,

To determine the incidence (risk) of depression in patients with TB at 2 and 6 months after starting anti-TB treatment,

To assess the impact of depression on anti-TB treatment outcomes (classical treatment outcomes: treatment default, interruption, completion, failure, death, disability score and health-related quality of life) at 2 and 6 months, and to explore the moderating effect of mhGAP depression interventions delivered in routine settings,

To assess whether depression is associated independently with longer pathways to anti-TB treatment (after adjusting for sociodemographic variables).

Hypotheses

People with TB who have depression at the time-of-treatment initiation (baseline) will have worse treatment outcomes of TB (classical treatment outcomes, disability score and health-related quality of life) at the end of 2 and 6 months follow-up when compared with those without depression at baseline.

Anti-TB treatment will progressively reduce depressive symptoms so that those with depression at baseline will have reduced severity of depression (Patient Health Questionnaire-9; PHQ-9 scores) or no depression after 2 and 6 months treatment for TB.

Methods and analysis

Study setting

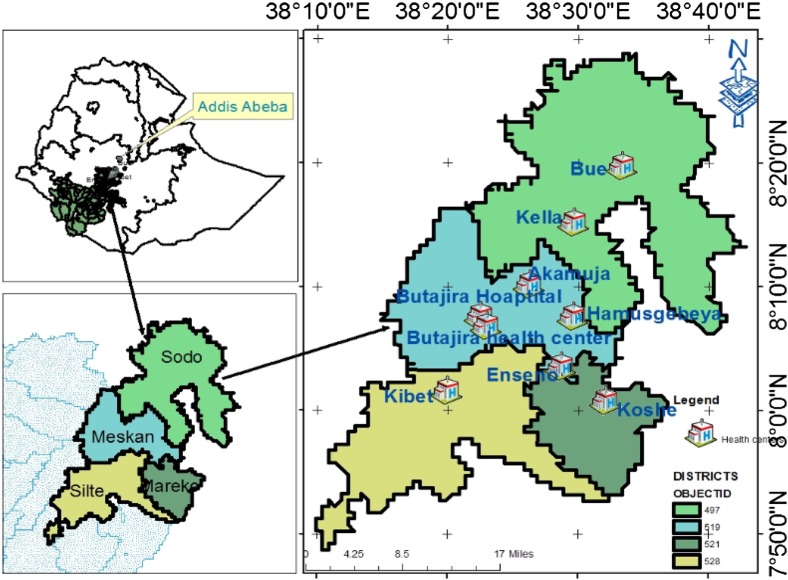

The study will be conducted from December 2014 to December 2015 in nine primary care facilities in Butajira town, Mareko district, Meskan district, Sodo district and Silte district of the Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples’ Region (SNNPR) of Ethiopia (figure 2). Farming is the main economic activity in the area. In 2012/2013, there were 2742 people with TB in the zone. Directly observed treatment short-course (DOTS) for TB is being implemented in all health facilities.9 In 2011, the anti-TB treatment defaulter rate, death rate and treatment success rate were 2.5%, 2.0% and 82.3%, respectively, in SNNPR.32

Figure 2.

Map of the study area.

Delivery of anti-TB treatment and care in rural Ethiopia

The DOT for new patients with TB lasts for 6 months, and consists of two phases: intensive and continuation. The intensive phase consists of treatment with a combination of four medications (rifampicin, ethambutol, isoniazid and pyrazinamide) for the first 2 months, and the continuation phase consists of a combination of two medications (rifampicin and isoniazid), to be taken for 4 months immediately after the intensive phase. A health worker or community-based anti-TB treatment supporter has to observe the patient swallow the medications once a day. Currently, anti-TB treatment is being delivered in health centres, hospitals (by health workers) and at health posts (by trained community-based ‘health extension workers’).9 Health posts are the lowest level of healthcare in Ethiopia, serving 5000 people. The flow of patients with TB in each of the health facilities selected for this study is above 5/month (figures 1 and 2).

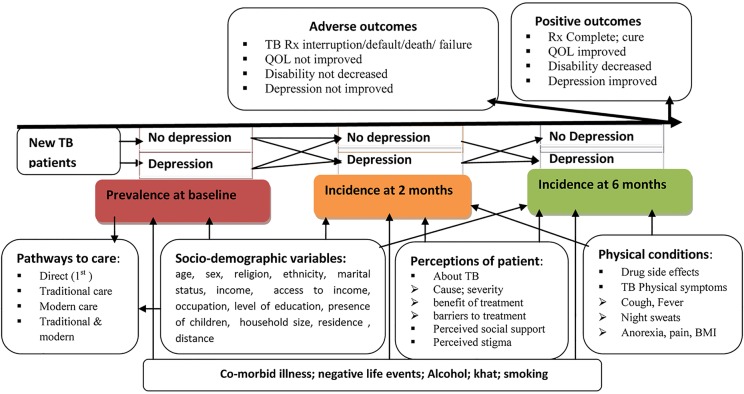

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of the study (BMI. body mass index; QOL, Quality of life; Rx, treatment; TB, tuberculosis).

Study design

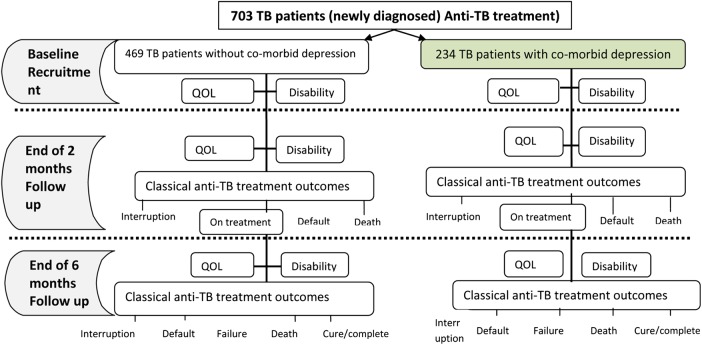

The study is a prospective cohort in which adults with newly diagnosed TB will be recruited at the time of initiating treatment and followed up to the end of treatment (6 months after initiation) (figure 1). Data collection will occur at three time-points: baseline (before anti-TB treatment), at 2 months (end of intensive phase) and at 6 months (end of continuation phase; table 1). Figure 3 shows the approach to investigation of the effect of TB on depression and figure 4 shows the approach to investigation of the effect of depression on TB.

Table 1.

Variables of the study and their plan of measurement

| Number | Variables | Measurement time |

Variable category | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | End of 2nd month | End of 6th month | |||

| 1 | Depression | √ | √ | √ | Exposure |

| 2 | Treatment outcomes of TB (complete, cure, failure, default, death, interruption) | √* | √ | Outcome | |

| 3 | Quality of life | √ | √ | √ | Outcome |

| 4 | Disability | √ | √ | √ | Outcome |

| 5 | Pathways to TB healthcare | √ | Outcome | ||

| 6 | Severity of signs and symptoms of TB | √ | √ | √ | Predictor |

| 7 | Sociodemographic variables | √ | Predictor | ||

| 8 | Substance use | √ | √ | √ | Predictor |

| 9 | Comorbid illness/negative life event | √ | √ | √ | Predictor |

| 10 | perceived social support | √ | √ | √ | Predictor |

| 11 | Perceptions of patients about TB | √ | Predictor | ||

| 12 | Medication side effects | √ | √ | Predictor | |

| 13 | Tuberculosis related stigma | √ | √ | Predictor | |

√*=Only the presence/absence of treatment interruption, death and default will be measured.

Figure 3.

Schematic illustration for analysing the effect of tuberculosis on depression.

Figure 4.

Schematic illustration for analysing the effect of depression on tuberculosis (QOL, Quality of life; TB, tuberculosis).

Inclusion criteria:

Patients attending the selected health centres who have started their anti-TB treatment within the last 1 month

Those aged over 17 years.

Exclusion criteria:

Patients with a known plan to be transferred out of the study sites

Those too ill to be interviewed at baseline as perceived by the interviewer or the patient

Those patients admitted to the in-patient unit for more than 5 days in the last 1 month

Patients with MDR-TB, who constitute a different population because their treatment is different (more toxic medications for a much longer duration). MDR-TB is a much more feared and stigmatised condition with patients probably told that no further treatment is available. In addition, only one of the study health institutions has recently started the service for patients with MDR-TB

Patients on re-treatment, who have experiences of previous failures and usually have MDR-TB. When we try to see “What happens to the depression at baseline when the TB is treated?” we are assuming that the treatment for the TB works well. Therefore, this group of patients will be excluded.

Sample size determination

The sample size was calculated using STATA V.12.0.33 We used the following parameters: 80% power, 95% confidence (one sided). We estimated that the prevalence of treatment default among patients with TB without depression will be 2.5% (estimate for the SNNPR).32 We used an estimate of a 5% increase in prevalence of defaulting among comorbid patients (ie, a prevalence of treatment default of 7.5% among people with TB and comorbid depression). Given the risk of death and drug resistance among treatment defaulters, a 5% difference could be a clinically important effect.34 We estimate that we will find a ratio of 2:1 of non-exposed (not depressed) to exposed (depressed) participants. With these assumptions, the required sample size is 639. After adding 10% contingency to account for potential loss to follow-up, the total sample size is 703, of which 234 will be exposed (with depression) and 469 will be non-exposed (without baseline depression). In a recent cross-sectional study carried out in outpatient healthcare settings in Northern Ethiopia, the ratio of non-exposed (patients with TB without depression) to exposed (patients with TB with depression) was approximately 2:1. In the same study, 31% of the patients with TB had depression, as measured using both SRQ-20 (cut-off 7 or above) and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (cut-off eight or above) (Ambaw F. Convergence validity of the Amharic-HADS among tuberculosis patients in Bahir Dar and West Gojam Zone, Ethiopia(un published manuscript). 2013).

Recruitment and data collection

The health professionals (usually BSc nurses and health officers) running the TB clinic at each site will identify the study participants who meet the inclusion criteria consecutively until a total of 703 participants is reached, and link them to experienced and trained diploma holder nurse research assistants employed to collect data full time. The health professionals in the TB clinics will also have a role in helping the research assistants in reviewing the patients’ charts for TB treatment outcomes, comorbid illness and drug side effects. The research assistants will provide information about the study to the patient and seek informed written consent. They will enrol patients who consent and arrange appointment dates for the next interviews, and carry out interviews at the health institutes. When patients do not consent to participate in the study, the research assistant will request permission to record sex, age, level of education and occupation of the patient. The list of variables and timing of data collection is described in table 1.

Measurement

The primary exposure variable

Depression will be measured using PHQ-9.35 36 The PHQ-9 has been validated and used in Ethiopia.37 Patients scoring 10 or more will be classified as having high depressive symptoms (exposed). Symptoms will be categorised using established cut-points 5, 10, 15 and 20 (mild, moderate, moderately severe and severe depression, respectively)35 36 to determine the different severities of exposure, and interval level scoring will be computed to examine changes in intensity of depression when the comorbid TB is treated.

Outcome variables

Primary outcome variable

Classical TB outcomes as defined by WHO28 and Federal Ministry of Health of Ethiopia:9 treatment defaulted, interrupted, failure, completed, cured or death. Data on the patients’ status on the primary outcome variable will be extracted from the TB register.

Secondary outcome variables

Quality of life (QOL): measured using a single item “How would you rate your quality of life?”, with a continuous numerical scale with values ranging from zero (worst possible quality of life) to 10 (highest possible quality of life) as recommended by de Boer et al38 and WHO.39

Disability: will be measured using the interviewer administered version of the 12-item WHO Disability Assessment Schedule V.2.0 (WHODAS V.2.0)40 with scores ranging from 12 to 60, where higher scores will represent worse levels of disability. WHODAS V.2.0 has been used previously in Ethiopia and found to have convergent validity.41 42

Pathways to healthcare: We are interested in finding out which other care providers (ie, traditional healers, other modern medicine providers) patients with TB have visited in relation to symptoms related to the present illness before attending the TB clinic. This will be measured at baseline using a modified version of the WHO encounter form for mental disorders.43

Independent variables

Signs and symptoms of TB: Body mass index (weight in kg/height in m2), fever, night sweats, cough, pain, perceived weakness and anorexia will be measured using single-item numerical indicator with scores ranging from 0 to 10, where 0 means absence of a symptom. The items will be as follows: “How is your cough this week”, “how is your fever this week”, “how are your night sweats this week”, “how is your pain this week”, “how weak do you feel this week”, and “how is your appetite this week?”.

Sociodemographic variables: will include age, sex, marital status, level of education, religion, ethnicity, average household monthly income, perceived access to the household income for the purpose of healthcare (no access, only some access, adequate access), household size, occupation, place of residence (urban vs rural), distance of the residence from health institute (estimates in kilometres) and presence of dependent children. Data on sociodemographic variables will be collected at baseline using a structured questionnaire administered by interviewers.

Substance use: The use of alcohol, tobacco and khat among the study participants will be measured using the Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) (V.3.1)44 at the three time-points. ASSIST consists of eight items for each of alcohol and khat use and seven items for tobacco products. It is a valid and reliable scale in primary care settings in low-income and middle-income countries.44–47

Comorbid illness and major life events: Data on the presence of comorbid illnesses such as HIV co-infection, cardiovascular diseases, chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases, diabetes mellitus and mental illnesses, including previously diagnosed depression, will be collected by asking the patient “Do you have another (other than TB) diagnosed health problem(s)? Please specify”, at all three time-points. If reported, the type of comorbid illness, time of diagnosis and treatment being taken (if any) will be specified by reviewing the participants’ medical records. Similarly, major life events of clients over the last 2 months will be captured by asking the question “Did you have an event (events) that you think has negatively affected your life over the last 2 months (eg, death of a family member, divorce, loss of property?”.

Perceived social support: the individual's evaluation of whether and to what extent relationships are helpful48 and the expectation of whether support will be provided within one's social network.49 These two domains will be measured using the three-item Oslo Scale of Perceived Social Support,50 with scores ranging from 3 to 14, with higher scores indicating better perceived social support.

Perceptions of patients about TB: perceived causes, severity, benefits of anti-TB treatment and barriers to anti-TB treatment will be measured using open-ended semistructured interviews that will be coded thematically, categorised and quantified so that responses may be included in the quantitative analysis as categorical variables. The guiding questions will be ‘What do you think causes TB?’ ‘How severe do you think TB can be?’ ‘How helpful do you think the treatments of TB would be?’ ‘What do you think your barriers may be to completing your treatment’. Measurement will be taken at the second month to minimise the burden of items at baseline, when patients may be most ill.

Medication side effects: Information about medication side effects will be extracted from the patient's chart.

TB-related stigma: will be measured using a 10-item TB stigma scale adopted from Macq et al51 in Nicaragua. This instrument has been piloted on 68 patients with TB, who will be excluded from the main study, and was found to be understandable (except for one of the items, which has been modified after the pilot), acceptable to the respondents and data collectors, and to have an internal consistency coefficient (α value) of 0.78. The translation of the instrument into the local language was made using the mixed methods translation and consensus generation approach. This is a three-step process. In step 1, panelists independently translate all items and then independently rate every translation so that the translations are categorised into inappropriate, modifiable and appropriate. In step 2, modifiable translations are modified, rated independently and categorised into inappropriate or appropriate translation. In step-three, a consensus discussion is made on items categorised as appropriately translated in step-one and step-two, and ranked to get the best translations.52

TB-related stigma will be measured at the end of the second month and at the end of the sixth month, to provide time for social interaction after diagnosis and to distinguish between stigmatising attitudes or behaviours from appropriate precautions to prevent TB transmission. A patient with smear positive pulmonary TB becomes non-infectious usually within 2–3 weeks except in the case of drug resistance.9

Treatment for depression: For patients with depression diagnosed by the health system, the appropriateness of their treatments (for the depression) will be coded as appropriate if they are in accordance with mhGAP interventions guidelines and inappropriate if they do not follow the recommended treatment approaches. According to this guideline, an adult endorsing at least two of the three core depression symptoms (depressed mood, loss of interest in activities and decreased energy), three other features of depression (reduced concentration and attention, reduced self-esteem and self-confidence, ideas of guilt and unworthiness, bleak and pessimistic view of the future, ideas or acts of self-harm or suicide, disturbed sleep, diminished appetite) and having difficulties carrying out usual work, school, domestic, or social activities over the same last 2 weeks period in the absence of bereavement or other major loss in prior 2 months, is identified as likely to have moderate–severe depression.29

The recommended treatment is: providing psychoeducation, addressing existing psychosocial stressors, reactivating social networks, a structured physical activity programme, offering regular follow-up and considering antidepressants (fluoxetine and amitriptyline, as well as other tricyclic antidepressants).29 The nurses and health officers of the health facilities, who are the main care providers, have been trained by the health system and the drugs are given to patients free of charge.

Data management

Data will be checked for consistency and completeness by supervisors, double-checked by the principal investigator and double entered to EpiData 3.1 by experienced data entry clerks. Then, it will be exported to SPSS V.20 for cleaning and analysis. Hard copies of the data will be stored in a locked cabinet and consent forms will be separated from the data.

Data analysis

Data will be analysed using SPSS V.20. Descriptive statistics will be computed to describe the sociodemographic characteristics of participants and to summarise the distribution of each of the dependent (outcome) and independent variables. We will check to see whether refusal or losses to follow-up is associated with sociodemographic characteristics by testing the statistical significance of differences between refusals and consenters, and those lost to follow-up versus those retained at 6 months in terms of age, sex and level of education.

The prevalence of probable depression among patients with TB at baseline will be determined by computing the proportion of patients scoring 10 and above on the PHQ-9 scale. The same analysis will be carried out at endline and the magnitude of the difference between the two measurements (baseline and endline) will be calculated and the statistical significance tested using McNemar test for repeated measures. Determinants of depression at baseline will be examined using logistic regression with depression as a dependent variable, and sociodemographic characteristics, symptoms of TB, perceived social support and substance use included as predictors. The proportion of patients with TB that scored below 10 on PHQ-9 at baseline but who had scores of 10 and above at the end of the second month will be computed to determine incidence (risk) of depression at 2 months. This will be repeated at 6 months.

The change in depressive symptoms (PHQ-9 scores) over the three data collection points will be analysed using multilevel mixed effect model by setting measurement occasions as level 1 and individual patients with TB as level 2 of the analysis. Level of disability, substance use, presence of additional chronic illnesses, level of perceived social support, perceptions of patients about TB and appropriateness of depression treatment will be predictors at level-1; sociodemographic characteristics of the individual will be predictors at level-2. We have selected this analysis approach as it does not require complete data over measurement occasions, equal interval of measurement for each case, or sphericity assumptions.53–56

The effect of depression on the treatment pathways of patients with TB will be analysed using binary logistic regression. The pathways followed by participants to access care will be entered as separate-dependent variables; after coding each of the different pathways as zero (if the specific pathway is not followed) or one (if the specific pathway is followed), depression will be included as an independent variable. We will adjust for sociodemographic characteristics.

To determine the effect of depression on the classical outcomes of anti-TB treatment, logistic regression will be carried out at the end of sixth months, with the treatment outcomes (interrupted, defaulted, completed) as dependent variables and depression as an independent variable. We will adjust for substance use, stigma, comorbid illnesses, sociodemographic factors, medication side effects, perceived social support and perceptions of the patient about TB. Although multinomial logistic regression could handle the mutually exclusive treatment outcomes as values of one dependent variable with more than two categories, we have elected to use logistic regression in order to simplify the interpretation of our results.

The change in quality of life and disability levels over time will be modelled by setting measurement occasions as level-1 and individual patients as level-2. In this analysis, PHQ-9 scores, substance use, presence of additional chronic illnesses, level of perceived social support, appropriateness of depression treatment, level of TB stigma, medication side effects and perceptions of patients about TB will be modelled as level-1 predictors and sociodemographic characteristics of the individual will be predictors at level-2.

All the necessary assumptions will be tested and the findings will be reported before inferential statistics are calculated. Statistical tests will be considered significant when p values are less than 0.05, and 95% CIs will be presented throughout.

Ethical considerations

The proposal has been ethically cleared by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of College of Health Sciences, Addis Ababa University, on 23 July 2014, number 027/14/Psy. Informed written consent will be obtained from every participant. Fingerprint impressions will be taken from consenting illiterate participants. Patients identified as having PHQ-9 scores 10 or above or endorsing the suicide item of PHQ-9, will be referred to nurses trained in mental health interventions by another project working in collaboration with the Ministry of Health of Ethiopia. We will give each participant 30.00 Birr ($1.50) to compensate them for the time they spend with us. This amount of money is enough to cover breakfast and a soft drink. We will not give any other incentives.

Dissemination plan

Findings will be disseminated through publications in peer-reviewed journals and conference presentations. Summary reports will be submitted to the health institutions and policymakers concerned. Community meetings will be held to disseminate findings to the local community, including study participants.

Limitations of the study

We have used PHQ-9 (a screening tool) to measure depression, which may lead to error of categorising patients into exposed and not exposed at baseline. However, this will not compromise the work of capturing the change in depression scores over time.

Currently, health institutes are actively strengthening tracing mechanisms in order to decrease treatment default and treatment interruption. This work may mean that those who are otherwise more likely to default or interrupt treatment may complete their treatment, which may, in turn, weaken any association between the exposure and these outcome variables. There may also conceivably be a ‘treatment effect’ of study participation in terms of improving depressive symptoms and encouraging people to adhere to treatment. In this low-income setting, people may have undiagnosed comorbid illnesses and our method of capturing comorbid illnesses may not be strong. Quality of life will be measured using a single item and we will therefore not obtain detailed information on the various dimensions that make up this construct. In addition, our conclusions cannot be applied to patients with MDR-TB and patients on re-treatment for TB.

Strengths of the study

The study will provide much needed evidence about the impact of comorbid depression on the course and outcome of TB. The longitudinal study design will allow us to estimate the incidence of depression among people engaged with TB treatment. The observation of depression TB comorbid patients from treatment initiation to completion date will allow us to investigate whether TB treatment alone may be sufficient to reduce depressive symptoms. The study will enable us to investigate the impact of depression in determining the course and outcome of TB, independent of the effects of other factors such as sociodemographic variables, stigma, perceived social support, substance use and comorbid illnesses such as HIV. As far as we are aware, this study will be the first in Ethiopia, or in any African setting, to examine the potentially important role of depression in determining pathways to TB care.

Expected benefits of the findings

Our findings will contribute to a sparse evidence base on mental health, TB and other chronic diseases in low-income and middle-income countries. We hope that other researchers will be encouraged to investigate important questions in this area. We anticipate that our study findings will contribute to raising awareness among Ethiopian clinicians and service providers about the potential impact of comorbid depression on the course and management of chronic disease, as well as informing future plans and policies related to the delivery of mental healthcare in primary care and other healthcare settings in Ethiopia.

Footnotes

Contributors: FA, RM, CH and AA contributed equally to the design of the study. FA drafted the manuscript and all the authors revised and approved the manuscript.

Funding: The research is funded by the European Union, Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013) under the Emerald grant agreement number 305968.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Institutional review board (IRB) of College of Health Sciences, Addis Ababa University.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The data will be available from the authors, with permission from the Department of Psychiatry, Addis Ababa University.

References

- 1.Katon WJ. Epidemiology and treatment of depression in patients with chronic medical illness. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2011;13:7–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katon W, Lin EH, Kroenke K. The association of depression and anxiety with medical symptom burden in patients with chronic medical illness. Gen Hosp Psychiat 2007;29:147–55. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ustun TB, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Chatterji S et al. Global burden of depressive disorders in the year 2000. Brit J Psychiatr 2004;184:386–92. 10.1192/bjp.184.5.386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO. The world health report: mental health: new understanding, new hope. 2001.

- 5.WHO. The effectiveness of mental health services in primary care: the view from the developing world. 2001;WHO/MSD/MPS/01.1. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012;380:2197–223. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hailemariam S, Tessema F, Asefa M et al. The prevalence of depression and associated factros in Ethiopia: findings from the National Health Survey. Int J Ment Health 2012;6:23 10.1186/1752-4458-6-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abdulahi H. Burden of disease analysis in rural Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J 2001;39:271–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Federal Ministry of Health of Ethiopia. Guidelines for clinical and programmatic managment of TB, Leprosy and TB/HIV in Ethiopia. 5th edn Addis Ababa: Falcon Printing, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 10.WHO. Global tuberculosis control report. 2011.

- 11.Issa BA, Yussuf AD, Kuranga SI. Depression comorbidity among patients with tuberculosis in a university teaching hospital outpatient clinic in Nigeria. Ment Health Fam Med 2009;6:133–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Panchal SL. Correlation with duration and depression in TB patients in rural Jaipur district (NIMS Hospital). Int J Pharm Bio Sci 2011;2:263–7. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sulehri MA, Dogar IA, Sohail H et al. Prevalence of depression among tubercolosis patients. APMC 2010;4:133–7. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aydin IO, Ulusahin A. Depression, anxiety comorbidity, and disability in tuberculosis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients: applicability of GHQ-12. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2001;23:77–83. 10.1016/S0163-8343(01)00116-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iga OM, Lasebikan VO. Prevalence of depression in tuberculosis patients in comparison with non-tubercolosis family contacts visiting the DOTS clinic in a Nigerian tertiary care hospital and its correlation with disease pattern. Ment Health Fam Med 2011;8:235–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trenton AJ, Currier GW. Treatment of comorbid tuberculosis and depression. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2001;3: 236–43. 10.4088/PCC.v03n0610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moussas G, Tselebis A, Karkanias A et al. A comparative study of anxiety and depression in patients with bronchial asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and tuberculosis in a general hospital of chest diseases. Ann Gen Psychiatry 2008;7:7 10.1186/1744-859X-7-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deribew A, Tesfaye M, Hailmichael Y et al. Common mental disorders in TB/HIV co-infected patients in Ethiopia. BMC Infect Dis 2010;10:201 10.1186/1471-2334-10-201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simon GE, Von Korff M, Lin E. Clinical and functional outcomes of depression treatment in patients with and without chronic medical illness. Psychol Med 2005;35:271–9. 10.1017/S0033291704003071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sweetland A, Oquendo M, Wickramaratne P et al. Depression: a silent driver of the global tuberculosis epidemic. World Psychiatry 2014;13:325–6. 10.1002/wps.20134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mikkelsen RL, Middelboe T, Pisinger C et al. Anxiety and depression in patients with chronic onstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): A review. Nord J Psychiat 2004;58:65–70. 10.1080/08039480310000824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vega P, Sweetland A, Acha J et al. Psychiatric issues in the management of patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2004;8:749–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reiche EM, Nunes SO, Morimoto HK. Stress, depression, the immune system, and cancer. Lancet Oncol 2004;5:617–25. 10.1016/S1470-2045(04)01597-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Glaser R. Depression and immune function: central pathways to morbidity and mortality. J Psychosom Res 2002;53:873–6. 10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00309-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rayner L, Price A, Evance A et al. Antidepressants for depression in physically ill people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;(3):CD007503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodin G, Voshart K. Depression in the medically ill: an overview. Am J Psychiat 1986;143:696–705. 10.1176/ajp.143.6.696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Doherty AM, Kelly J, McDonald C et al. A review of the interplay between tuberculosis and mental health. Gen Hosp Psychiat 2013;35:398–406. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.WHO. Treatment of tuberculosis: guidelines. 4th edn WHO/HTM/TB/2009.420 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.WHO. Mental health gap action programme intervention guide for mental, neurological and substance use disorders in non-specialized health settings 2010. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241548069_eng.pdf (accessed Dec 2012).

- 30.Fedeal Ministry of Health of Ethiopia. Ethiopian mental health strategy 2012. http://www.centreforglobalmentalhealth.org/sites/www.centreforglobalmentalhealth.org/files/uploads/documents/ETHIOP~2.pdf (accessed Jan 2013).

- 31.WHO. Global tuberculosis report. 2012.

- 32.Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Health. Health and Health Related Indicators 2011. http://www.dktethiopia.org/sites/default/files/PublicationFiles/Health%20and%20Health%20Related%20Indicators%202003%20E.C.pdf (accessed Dec 2013).

- 33.StataCorp LP. USA: 2011. http://www.stata.com/stata11/ [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ferguson CJ. An effect size primer: a guide to clinicians and researchers. Prof Psychol Res Pr 2009;40:532–8. 10.1037/a0015808 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:606–13. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB et al. The patient health questionnaire somatic, anxiety, and depressive symptom scales: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiat 2010;32:345–59. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gelaye B, Williams MA, Lemma S et al. Validity of the patient health questionnaire-9 for depression screening and diagnosis in East Africa. Psychiat Res 2013;210:653–61. 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.07.015i [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Boer AG, van Lanschot JJ, Stalmeier PF et al. Is a single-item visual analogue scale as valid, reliable and responsive as multi-item scales in measuring quality of life? Qual Life Res 2004;13:311–20. 10.1023/B:QURE.0000018499.64574.1f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.WHO Regional Office for Europe (EUROHIS). Developing common instruments for health surveys 2003.

- 40.WHO. Measuring Health and Disability: Manual for WHO Disability Assessment Schedule, WHODAS 2.0 2010. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241547598_eng.pdf (accessed 23 Oct 2013).

- 41.Mogga S, Prince M, Alem A et al. Outcome of major depression in Ethiopia: population-based study. Br J Psychiatry 2006;189:241–6. 10.1192/bjp.bp.105.013417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Senturk V, Hanlon C, Medhin G et al. Impact of perinatal somatic and common mental disorder symptoms on functioning in Ethiopian women: the P-MaMiE population-based cohort study. J Affect Disord 2012;136:340–9. 10.1016/j.jad.2011.11.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.WHO. Pathways of patients with mental disorders 1987. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/1987/MNH_NAT_87.1.pdf (accessed 24 Nov2013).

- 44.WHO. The Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST): Manual for use in primary care 2010.

- 45.Humeniuk R, Ali R, Babor TF et al. Validation of the Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST). Addiction 2008;103:1039–47. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02114.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Newcombe DA, Humeniuk RE, Ali R. Validation of the World Health Organization Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST): report of results from the Australian site. Drug Alcohol Rev 2005;24:217–26. 10.1080/09595230500170266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.WHO ASSIST Working Group. The Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST): development, reliability and feasibility. Addiction 2002;97:1183–94. 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00185.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schaefer C, Coyne JC, Lazarus RS. The health-related functions of social support. J Behav Med 1981;4:381–406. 10.1007/BF00846149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Seidlecki KL, Salthouse TA, Oishi S et al. The relationship between social support and subjective well-being across age. Soc Indic Res 2014;117:561–76. 10.1007/s11205-013-0361-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Meltzer H. Development of a common instrument for mental health. In: Nosikov A, Gudex C, eds. EUROHIS: developing common instruments for health surveys. Amsterdam: IOS Press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Macq J, Solis A, Martinez G et al. Tackling tuberculosis patients’ internalized social stigma through patient centred care: an intervention study in rural Nicaragua. BMC Public Health 2008;8:154. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-8-154 10.1186/1471-2458-8-154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sumathipala A, Murray J. New approach to translating instruments for cross-cultural research: a combined qualitative and quantitative approach for translation and consensus generation. Int J Meth Psych Res 2000;9:87–95. 10.1002/mpr.83 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Blackwell E, de Leon CF, Miller GE. Applying mixed regression models to the analysis of repeated-measures data in psychosomatic medicine. Psychosom Med 2006;68:870–8. 10.1097/01.psy.0000239144.91689.ca [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Burton P, Gurrin L, Sly P. Extending the simple linear regression model to account for correlated responses: an introduction to generalized estimating equations and multi-level mixed modelling. Stat Med 1998;17:1261–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Heck R, Thomas S, Tabata L. Multilevel and longitudinal modeling with IBM SPSS. 2nd edn USA: Taylor & Francis, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tabachnic BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. 5th edn: Pearson Educ. Inc., 2007. [Google Scholar]