Abstract

Endogenous regeneration has been demonstrated in the mammalian heart after ischemic injury. However, approximately one-third of cases of heart failure are secondary to nonischemic heart disease and cardiac regeneration in these cases remains relatively unexplored. We, therefore, aimed at quantifying the rate of new cardiomyocyte formation at different stages of nonischemic cardiomyopathy. Six-, 12-, 29-, and 44-week-old mdx mice received a 7 day pulse of BrdU. Quantification of isolated cardiomyocyte nuclei was undertaken using cytometric analysis to exclude nondiploid nuclei. Between 6–7 and 12–13 weeks, there was a statistically significant increase in the number of BrdU-labeled nuclei in the mdx hearts compared with wild-type controls. This difference was lost by the 29–30 week time point, and a significant decrease in cardiomyocyte generation was observed in both the control and mdx hearts by 44–45 weeks. Immunohistochemical analysis demonstrated BrdU-labeled nuclei exclusively in mononucleated cardiomyocytes. This study demonstrates cardiomyocyte regeneration in a nonischemic model of mammalian cardiomyopathy, controlling for changes in nuclear ploidy, which is lost with age, and confirms a decrease in baseline rates of cardiomyocyte regeneration with aging. While not attempting to address the cellular source of regeneration, it confirms the potential utility of innate regeneration as a therapeutic target.

Introduction

Although demonstrated in the mammalian heart after ischemic injury, cardiac regeneration remains relatively poorly investigated in nonischemic cardiomyopathies. These represent 30% of cases of clinical heart failure. The mdx mouse is a model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy with myocyte loss, leading to skeletal muscle wasting and a well-characterized progressive dilated cardiomyopathy [1]. In response to continuous myocyte loss, skeletal muscle undergoes cycles of myocyte regeneration, initially maintaining skeletal muscle function. We investigated whether the heart responds in a similar manner with the generation of new cardiomyocytes [2].

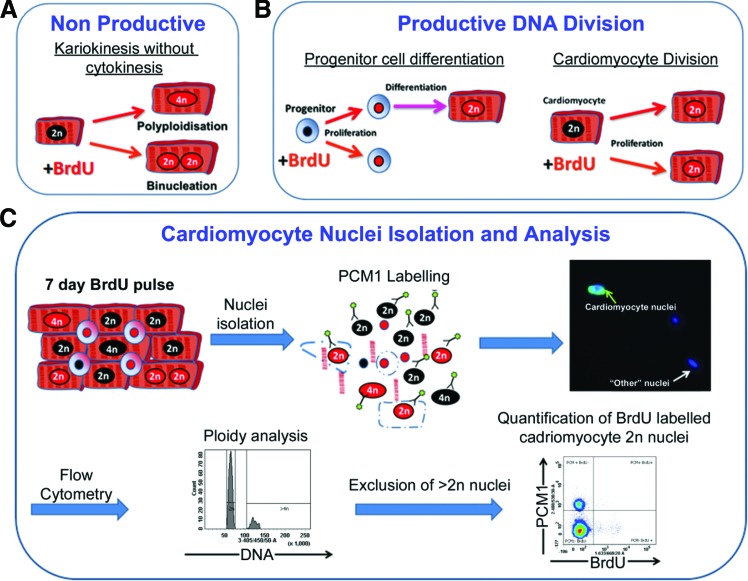

While the heart has some capacity to replace cardiomyocytes during normal aging and after acute injury, the degree of this potential remains controversial with disparate rates of cardiomyocyte turnover reported [3–8]. The source of such cardiomyocyte renewal remains unclear with evidence for both proliferation of pre-existing cardiomyocytes and contribution from an indeterminate progenitor population [8,9]. While conflicting data may be attributed to differences in methodology, other challenges include accurately identifying and quantifying very low levels of cardiomyoctye turnover against a background of cells with greater proliferative rates [10]. Furthermore, as cardiomyocytes have the potential for karyokinesis in the absence of cytokinesis, resulting in increased polyploidy or binucleation, nucleoside-labeling methods must account for the DNA replication occurring during these events, as such cells will incorporate the label into their nuclei (Fig. 1A). Previous studies have used cell-cycle markers to quantify cardiomyocyte turnover and regeneration, but it is increasingly accepted that they have a number of limitations [10]. Proteins such as Ki67 and the majority of cyclin-dependent kinases are expressed during the S, G1 S, and G2 phases of the cell cycle [11] and therefore by cells undergoing nonproductive DNA replication. Quantifying cardiomyocyte mitosis via expression of proteins required for cytokinesis, including Aurora B, is an attractive option, the subcellular localization of which is dependent on cell-cycle phase, and, as such, it can be used to distinguish between potential outcomes of progression into M while distinguishing between productive and nonproductive events [12]. Unfortunately, the undefined source of cardiomyocyte generation in the adult and the limited time period of expression during the cell cycle, the M phase accounts for 2% of the cell cycle [13], make such markers unsuitable for this study. In addition, as expression of Aurora B alone does not identify cytokinesis but rather the location of protein expression, histological analysis would be required for quantification, a technique that is criticized due to difficulties in cardiomyocyte identification [13–16]. Given the controversy regarding the cells responsible for regeneration and the potential rarity of cardiomyocyte generation, we used a BrdU-labeling strategy to quantify cumulative cardiomyocyte renewal irrespective of source (Fig. 1B). Recognizing the issues surrounding nonproductive DNA replication, we employed cytometric analysis of isolated cardiomyocyte nuclei to accurately quantify BrdU incorporation within the cardiomyocyte population while simultaneously analyzing ploidy, enabling exclusion of cardiomyocytes that underwent DNA replication due to polyploidation (Fig. 1C). Histological and confocal analysis enabled discrimination between mononucleated and binucleated cardiomyocytes.

FIG. 1.

Challenges and strategy for quantifying cardiomyocyte renewal. (A) Cardiomyocytes have the potential to undergo “nonproductive” DNA replication. (B) Continuous pulsing of BrdU has the potential to label the cardiomyocyte generation regardless of the cellular source. (C) Isolation of nuclei allows accurate quantification of BrdU labeling of cardiomyocyte nuclei and discrimination of BrdU incorporation due to polyploidy. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

Materials and Methods

Animal ethics and BrdU pulse

Animal work was authorized and approved by the Newcastle University Ethics review board. All animal procedures were performed conforming to the guidelines from Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes. Only male animals were used. The experimental group were C57BL/10 mice hemizygous for the mdx mutation (mdx) and C57BL/10 (wild type) mice used as controls. Six, 12, 29 and 45-week-old mdx and C57BL/10 control mice were injected (intraperitoneal) with BrdU (100 μg/g body weight) [17] once daily every 24 h for 7 consecutive days. After the final injection, mice were allowed to age for a further 24 h. Animal euthanasia was performed by cervical dislocation, and hearts were removed immediately. More than four animals were studied for each protocol. Analysis was carried out in a blinded fashion. A Supplementary and Methods section is available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

Cardiomyocyte nuclei isolation and cytometric analysis

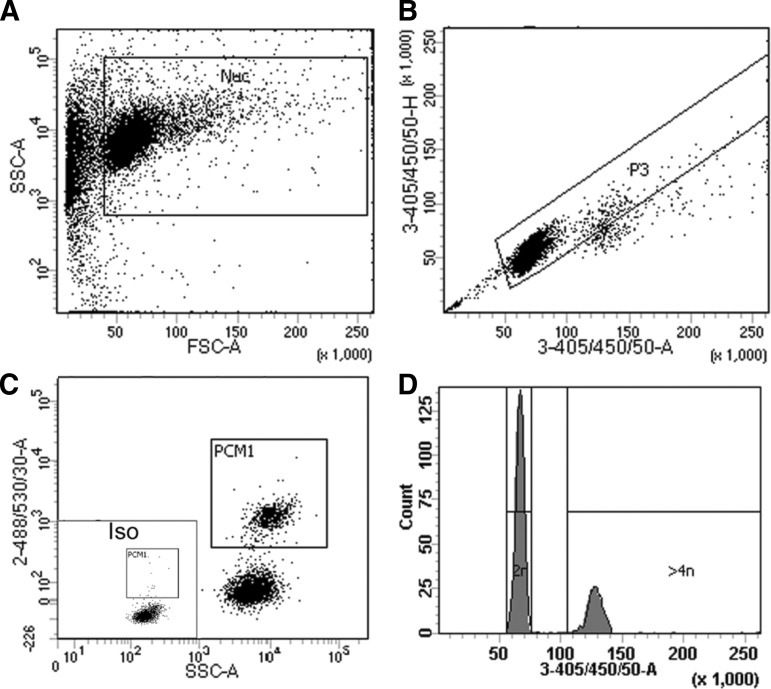

Nuclei were isolated as described [4]. Flow cytometry experiments were performed using an FACScanto (BD Biosystems). More than 10,000 events were collected, and analysis was performed as in Fig. 2 with FACdiva (Beckman Coulter, Inc.). BrdU detection was performed with anti-BrdU antibody kit (BD Pharmingen). Cardiomyocyte nuclei were identified with anti-pericentriolar material 1 (PCM1; Atlas Antibodies) [4,18,19]. DNA content was determined by 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining.

FIG. 2.

Gating strategy for cardiomyocyte nuclei and analysis of ploidy. (A) Cardiomyocyte nuclei are distinguished from debris using a plot of forward scatter versus side scatter. (B) As it is important that only single nuclei are included in subsequent analysis, single nuclei are identified based on 3-355/405/50-area versus 3-355/405/50-height [after 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) labeling]. (C) Isotype control allows gating for the identification of pericentriolar material 1-positive (PCM1+) cardiomyocyte nuclei and PCM1− noncardiomyocyte nuclei. (D) A histogram plot was created using 3-355/405/50-area on a linear scale for the analysis of the ploidy of each individual nucleus. As DAPI binding to DNA is stoichiometric, the fluorescence intensity is proportional to the amount of DNA. The majority of cardiomyocytes are 2N as expected; 4N nuclei have a fluorescent intensity twice that of the 2N population, and 8N nuclei are twice as intense again. All nuclei with an intensity greater than that of the 2N population were excluded from the analysis of cardiomyocyte renewal.

Immunohistochemistry

Ten or 40 μm sections were labeled with primary antibodies specific to BrdU (Abcam), PCM1 (Atlas Antibodies), Vimentin (Abcam), or cardiac Troponin-C (Abcam) and analyzed with a Leica SP5 laser scanning confocal system. Co-localization was verified by Z-stack imaging; cells were only considered co-expressing if signals localized to a single DAPI-labeled nucleus throughout the Z-stack. Quantification of BrdU-labeled cardiomyocytes was performed in a manner similar to the cellular counting method previously described [20]. Myocardial tissue was cryosectioned laterally in 40 μM sections. Sections were separated by intervals of 200 μM, and all BrdU-labeled cardiomyocytes (CTnC+/PCM1+) were counted in each section, creating a representative cross-section that included all regions of the heart to ascertain the total number of BrdU-labeled cardiomyocytes in the heart experimental group. For each BrdU-labeled cardiomyocyte, the location was also recorded as being in the left ventricle, right ventricle, or apex. The percentage of BrdU-labeled cardiomyocytes was obtained by dividing the total number of BrdU-labeled cardiomyocytes cells per section by the total number of cardiomyocyte nuclei, based on the expression of PCM1, in each section. Quantification of total nuclei was obtained by multiplying cell density by section area. Both the density of nuclei and area of the section were quantified using digital image analysis (ImageJ; U.S. National Institutes of Health; http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/). The results are presented as means±standard error. This method enables extensive co-expression analyses, while still demonstrating relative proportions of cell types and changes in them, if not absolute numbers in individual hearts.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance followed by a post hoc t-test. A value of P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

BrdU labeling of the diploid cardiomyocyte population is increased in young mdx hearts

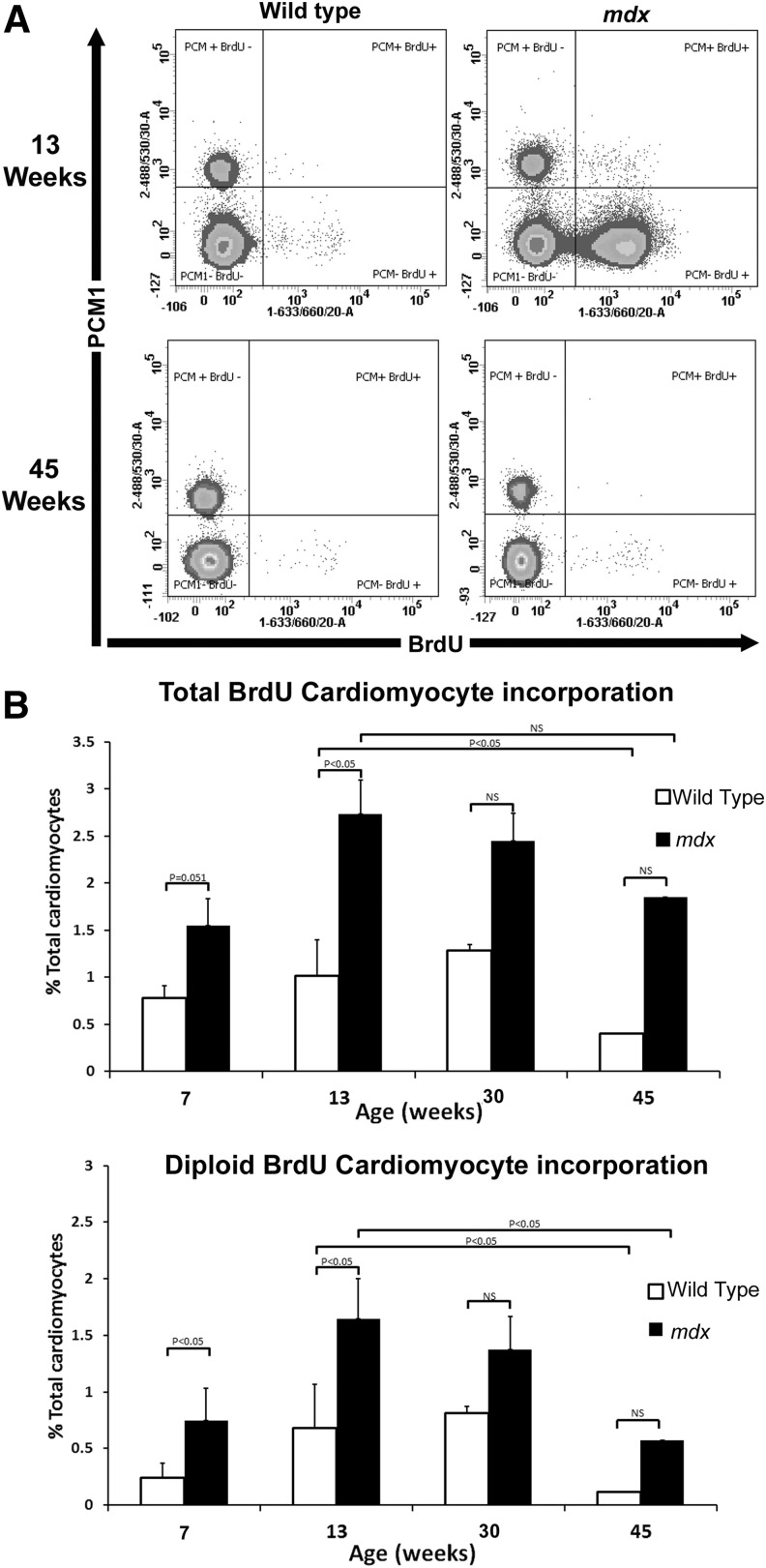

While cardiomyocyte loss occurs in the mdx mice from embryogenesis [21], cardiac function remains normal until ∼14 weeks of age (Supplementary Fig. S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd) [1]. In mdx hearts between 6–7 and 12–13 weeks, 1.55%±0.51% and 2.73%±1.9% of cardiomyocytes were labeled with BrdU, respectively. Between the same ages in the control, 0.78%±0.3% (6–7 weeks) and 1.01%±0.3% (12–13 weeks) of cardiomyocytes had incorporated BrdU (Fig. 3). Assuming that all BrdU incorporation in nuclei with a ploidy of >2N is due to polyploidization and not cardiomyocyte generation, we excluded this population from our calculations. This demonstrated a significant, 3.14-fold increase in diploid cardiomyocytes (0.75%±0.13%) in the mdx hearts compared with controls (0.24%±0.05%) between 6 and 7 weeks. A significant 2.4-fold increase in BrdU diploid cardiomyocytes was also observed in the mdx hearts between 12 and 13 weeks when compared with the control (1.64%±0.75% vs. 0.68%±0.30%). These data indicate that there is an increase in cardiomyocyte regeneration in the mdx model of cardiomyopathy due to chronic cardiomyocyte loss at ages before the described physiological changes associated with the disease progression. Furthermore, our data adds weight to the argument that cardiomyocyte turnover maintains the myocardium during cardiac homoeostasis as previously suggested [9,17].

FIG. 3.

Quantification of BrdU-labeled cardiomyocytes. (A) Flow cytometry of isolated nuclei showing representative plots from the 12–13 and 44–45 aged mice. (B) Graphs showing total BrdU incorporation in the total cardiomyocyte population (2N and >4N) or diploid cardiomyocytes only (2N only). n=4 animals used for each experimental group. Error bars±standard error of the mean.

The difference in BrdU incorporation is lost with increased age

We quantified BrdU labeling of cardiomyocytes in mice between 29 and 30 weeks, an age when histological evidence of the cardiovascular disease can be observed and between 44 and 45 weeks of age when mdx mice have been reported to have reduced cardiac function (Supplementary Fig. S1) [1,22]. At 30 weeks in the mdx hearts, 2.45%±1.0% of cardiomyocytes were BrdU labeled and 1.3%±1.0% were labeled in the control. At 45 weeks in mdx hearts, 1.85%±1.8% of cardiomyocytes were BrdU labeled whereas only 0.4%±0.06% were labeled in controls (Fig. 3). On excluding polyploid cardiomyocytes from calculations, no significant difference in the number of BrdU-labeled, diploid cardiomyocytes was observed between the mdx and the control at either 30 or 45 weeks (1.37%±0.62% vs. 0.81%±0.67%) (0.57%±0.40% vs. 0.11%±0.1%), respectively. These data demonstrate a significant (P<0.05) reduction in the number of BrdU-labeled diploid cardiomyocytes with age from 13 to 45 weeks in both the mdx (∼3-fold) and control (∼6-fold) and suggest that cardiomyocyte regeneration and turnover declines with age.

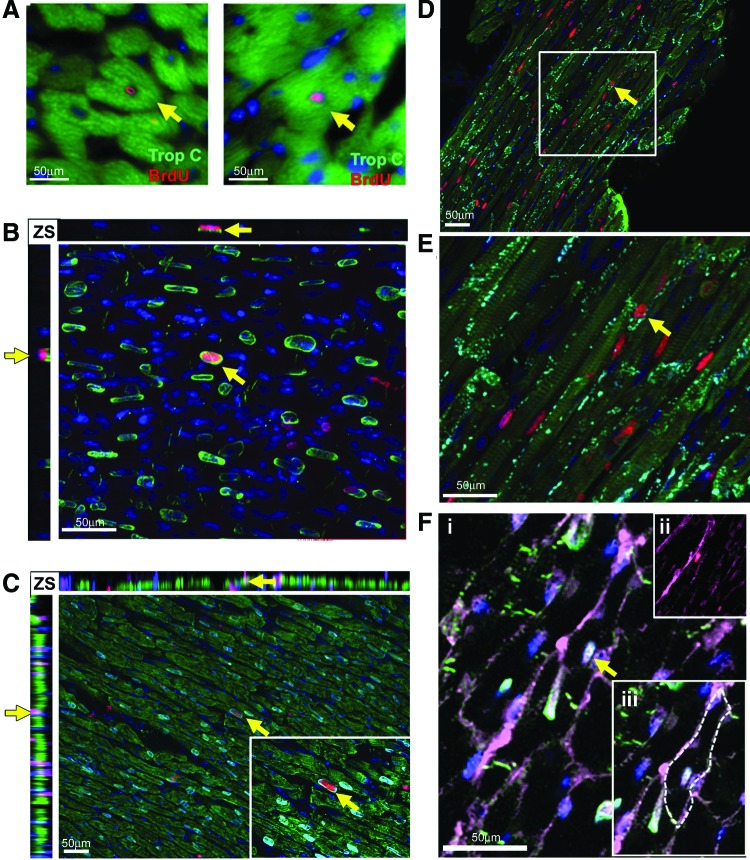

Increased incorporation of BrdU is associated with functional and integrated cardiomyocytes of young mdx mice and is not a result of bi-nucleation

The 12–13 week mdx animals demonstrated the most frequent cardiomyocyte generation and the 44–45 indicated the least; therefore, to validate the flow cytometry data and investigate the nucleation state of the BrdU-labeled cardiomyocyte population, we focused our immunohistological studies on these ages. As expected, the 13 weeks mdx hearts contained a larger number of BrdU cells than the 13 week control; a representative example is shown in Fig. 4A. In both the 13 and 45 week control hearts, rare BrdU cells were observed in the myocardium; these cells were not cardiomyocytes—all lacked expression of cardiac Troponin-C and PCM1. BrdU-labeled cells in the control heart comprised a heterogeneous population and were found expressing either CD31 or Vimentin, markers of endothelial cells or cardiac fibroblasts, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S2). Cells expressing the hematopoietic lineage marker CD45 were also observed in the control hearts but were restricted to the ventricle chambers (Supplementary Fig. S2). In the mdx hearts at 13 and 45 weeks, the majority of BrdU-labeled cells were located among interstitial cells of the myocardium and not of cardiomyocyte lineage, predominantly including cells expressing the fibroblast marker vimentin representing a fibrotic response (Fig. 4B and Supplementary Figs S3 and S4). BrdU-labeled cells expressing the hematopoietic marker CD45 were also observed within the myocardium in the mdx hearts, indicative of the previously documented immune infiltration that occurs in this model (Supplementary Figs S1, S3 and S4). BrdU incorporation was also observed in the endothelial population as demonstrated by CD31 co-expression, as in the control hearts (Supplementary Figs S3 and S4). More than 3,000 individual cardiomyocytes were analyzed per individual heart (Fig. 5A–F) and, in the 13 week mdx hearts, rare BrdU-labeled cardiomyocytes were observed throughout the myocardium of both ventricles and labeled nuclei were located within cardiomyocytes expressing the sarcomeric protein cardiac Troponin-C (CTnC) (Fig. 5A). The challenges of identification of cardiomyocyte nuclei using standard epifluorescence techniques are well documented. To alleviate these problems and to allow accurate identification of the nucleation state of the labeled cardiomyocytes, we used confocal Z-stack analysis of 40 μm-thick sections. These techniques were applied using combinations of antibodies specific to PCM1, CTnC, and the gap junction protein connexin 43 (Fig. 5B–F and Supplementary Videos S1a, b–S3a, b). We identified that BrdU was indeed incorporated into cardiomyocyte nuclei (expression of PCM1 with sarcomeric expression of CTnC). The expression of functional proteins CTnC and connexion 43 strongly suggests these cells represent components of the functional myocardium. In all observed cases, BrdU-labeled cardiomyocytes were identified as mononuclear, as all labeled cardiomyocyte nuclei were observed in isolation. The use of wheat germ agglutinin, a plasma membrane marker, further supported the mononuclear nature of these cardiomyocytes (Fig. 5F and Supplementary Video S3a, b). To validate our flow cytometry data, we quantified the BrdU-labeled cardiomyocyte population in these histological sections using confocal microscopy. BrdU-labeled cells were only considered cardiomyocytes if co-expressing both Troponin-C and PCM1. Using these strict criteria, we observed that 0.6%±0.1% of cardiomyocytes had incorporated BrdU at 13 weeks. BrdU-labeled cardiomyocytes were found in both left and right ventricles and the apex of the heart, with no evidence of regional clustering. In the control hearts at 13 and 45 weeks and mdx hearts at 45 weeks of age, no BrdU-labeled cardiomyocytes were observed (data not shown). This supports the flow cytometry data and demonstrates an increase in cardiomyocyte generation in the 13 week mdx hearts. The differences in the absolute frequency of BrdU-labeled cardiomyocytes in the 13-week-old mdx hearts when using the two methods and the inability to detect the rare population of BrdU-labeled cardiomyocytes in the 13-week-old control or the 45-week-old mdx, using immunohistological-based techniques, highlights the difficulties in the use of histological studies to identify and quantify rare cell populations. These data, however, demonstrate increased BrdU incorporation in the cardiomyocyte population in the 13-week-old mdx hearts. Furthermore, it demonstrates that this BrdU incorporation is not due to increased binucleation of the cardiomyocyte population. Together, this provides further evidence or a regenerative response in the mdx animals.

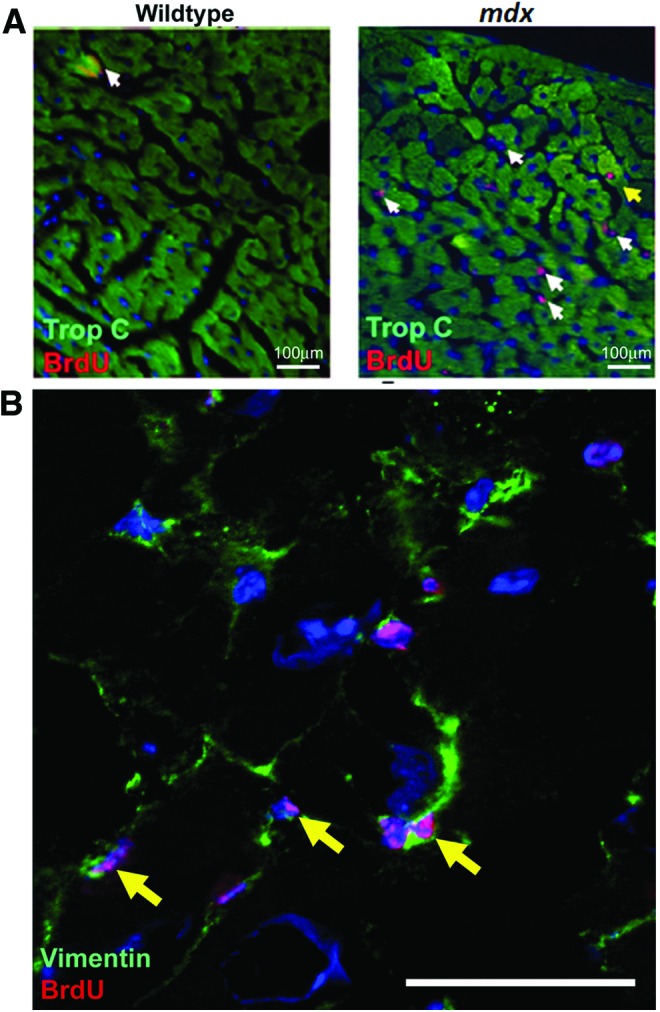

FIG. 4.

BrdU labeling between 12 and 13 weeks of age. (A) Anti-BrdU antibody (red) and anti-cardiac Troponin-C (CTnC) (green). BrdU-labeled cells lacking expression of CTnC (white arrows). Cardiomyocytes expressing CTnC and labeled with BrdU were observed only in mdx hearts (yellow arrows). (B) Representative example of Vimentin expressing noncardiomyocytes that had incorporated BrdU, anti-BrdU antibody (red), and anti-Vimentin (green). n=3 animals used for each experimental group. Cells expressing Vimentin which are also labeled with BrdU are indicated by yellow arrows. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

FIG. 5.

BrdU-labeled cardiomyocytes in mdx hearts between 12 and 13 weeks of age. (A) Higher power image of BrdU+-labeled cardiomyocytes in mdx hearts using 10 μm-thick sections. Cardiomyocytes identified with Anti-CTnC (green) Anti-BrdU (red). (B–F) Images are Z-stack projections taken from 40 μm-thick sections. (B) Solitary PCM1 expressing cardiomyocyte nuclei (green) that have incorporated BrdU (red), demonstrating BrdU incorporation in a mononuclear cardiomyocyte (C) PCM1 expressing nuclei (cyan) within a CTnC expressing mononucleated cardiomyocyte (green) that has incorporated BrdU (red). (D) Mononuclear, BrdU-labeled (red), CTnC expressing cardiomyocytes (green) also express gap junction protein Connexin 43. (E) Higher magnification image of cardiomyocyte in (E). (F, i) Demonstrates the mononuclear nature PCM1 expressing cardiomyocyte nuclei (cyan) that has incorporated BrdU (red) using wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) to label cell plasma membrane (magenta). (F, ii) PCM1 and DAPI removed to highlight BrdU labeling. (F, iii) Image highlights WGA-labeled plasma membrane with a dotted line. In all images, yellow arrows indicate co-labeled cardiomyocytes. Z-stacks (ZS), yellow arrows in ZS highlight the cell identified in the main image within the Z and X axis, used to demonstrate co-labeling is within a single cell and not due to labeling of overlaying cells. In all images, DAPI is used to label nuclei blue. n=3 animals used for each experimental group. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

There is a trend to polyploidy with increasing age

In 13 week animals, there was no significant difference in the proportion of polyploid BrdU-labeled cardiomyocytes (BrdU+, PCM1+>4N) between mdx and control (34.21%±11.4% vs. 33.52%±15.53%). Interestingly, at the 45 week ages, both control and mdx mice demonstrated a significant increase in the proportion of BrdU-labeled polyploid cardiomyocytes (BrdU+, PCM1+>4N) compared with 13 weeks (34.21%±11.4% vs. 66.0%±11.16% for the mdx and 33.52%±15.53% vs. 71.5%±6.13% for control). The difference between mdx and control animals at the latter time point was not significant. Similarly, both the mdx and control mice displayed a trend toward an increase in total (BrdU+ and BrdU−, PCM1+, >4N) cardiomyocyte ploidy with age, although not at a significant level. It has previously been demonstrated that increased ploidy within the cardiomyocyte population is associated with cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and remodeling of the myocardium [23]. Further, increased ploidy has been associated with age and a reduced potential for cardiomocyte turnover in humans [24]. These data together with our own suggest a shift from a regeneration and turnover to that of myocardial remodeling that is associated with cardiac aging.

Discussion

This study provides further evidence of mammalian cardiomyocyte renewal, declining with age, and an increase in cardiomyocyte regeneration after chronic myocyte loss, previously only demonstrated in acute ischemia. It demonstrates evidence of cardiomyocyte renewal in a model of cardiomyopathy at a stage preceding physiological changes, suggesting that cardiomyocyte regeneration may initially help maintain cardiac function despite a constant loss of cardiomyocytes (Supplementary Fig. S1). Our data also demonstrate that the histological changes of cardiac disease occur sooner than previously described [1,22,25–27], providing novel insight into the disease progression in this model. Moreover, we have demonstrated that increased cellular turnover likely plays a role in the pathophysiological process, predominantly through proliferation in the fibroblastic populations. Cognizant of the problems associated with cardiomyocytes undergoing karyokinesis in the absence of cytokinesis, we eliminated nondiploid nuclei from our final results. While not altering the overall conclusions or statistical significance of our results, it is worth noting that more than 30% of BrdU labeling could have been the result of karyokinesis, and not taking this into account would lead to this being erroneously considered representative of new cardiomyocytes.

It has previously been suggested that dysfunction in cardiac regenerative potential may be associated with chronic cardiac disease and aging [28]. However, evidence to support this has been limited to indirect assays demonstrating a reduction in markers associated with proliferation in the cardiomyocyte population; observations that are confounded by the kinetics of cardiomyocyte growth as changes in the rates of binulceation and ploidy will also directly affect the expression of these markers, or by a reduction in the “health” of putative cardiac stem cell populations [5,29–32]. Such observations are difficult to interpret due to the lack of consensus on the cardiac stem cell phenotype and the more recent observation that during normal aging cardiomyocyte proliferation and not stem cell differentiation is the primary mechanism of cardiomyocyte turnover [8,9]. This study is the first demonstration of a direct reduction in cardiomyocyte generation with age and disease using techniques that overcome these potential caveats.

Exhaustion of regenerative potential has been implicated in the pathophysiology of the skeletal disease of mdx mice as demonstrated by the exacerbated disease phenotype of mdx mice that have reduced stem cell function due to a lack of telomerase activity (mdx/Terc−/−) [28]. As mdx/Terc−/− mice developed more severe functional cardiac deficits compared with mdx/Terc+/+ littermates [33], it is intriguing to speculate that this may reflect a similar mechanism occurring in the heart, supported by our demonstration of a loss of regeneration at later disease stages. Indeed, it has been reported that cardiac stem cell function may decline in end-stage cardiomyopathy in the mdx model [34], although it is important to highlight the caveat of the yet undefined nature of any “true” cardiac stem cell population.

This study was not designed to address the cellular source of cardiomyocyte renewal—future lineage tracing and knock-out models will further quantify this regenerative capacity and demonstrate whether the later decline represents changes within differentiated cardiomyocytes or depletion of a progenitor cell population.

A better understanding of the process of regeneration in chronic cardiac disease is needed to address two important questions—to what degree is heart failure fundamentally a regenerative disease and does the failing heart still contain a population of cells that retains regenerative potential, providing a therapeutic target?

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the British Heart Foundation, project grant PG/13/69/30454.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Quinlan JG, Hahn HS, Wong BL, Lorenz JN, Wenisch AS. and Levin LS. (2004). Evolution of the mdx mouse cardiomyopathy: physiological and morphological findings. Neuromuscul Disord 14:491–496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turk R, Sterrenburg E, de Meijer EJ, van Ommen GJ, den Dunnen JT. and ‘t Hoen PA. (2005). Muscle regeneration in dystrophin-deficient mdx mice studied by gene expression profiling. BMC Genomics 6:98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergmann O, Bhardwaj RD, Bernard S, Zdunek S, Barnabe-Heider F, Walsh S, Zupicich J, Alkass K, Buchholz BA, et al. (2009). Evidence for cardiomyocyte renewal in humans. Science 324:98–102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bergmann O, Zdunek S, Alkass K, Druid H, Bernard S. and Frisen J. (2011). Identification of cardiomyocyte nuclei and assessment of ploidy for the analysis of cell turnover. Exp Cell Res 317:188–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kajstura J, Gurusamy N, Ogorek B, Goichberg P, Clavo-Rondon C, Hosoda T, D'Amario D, Bardelli S, Beltrami AP, et al. (2010). Myocyte turnover in the aging human heart. Circ Res 107:1374–1386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kajstura J, Urbanek K, Perl S, Hosoda T, Zheng H, Ogorek B, Ferreira-Martins J, Goichberg P, Rondon-Clavo C, et al. (2010). Cardiomyogenesis in the adult human heart. Circ Res 107:305–315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 7.Leri A, Quaini F, Kajstura J. and Anversa P. (2001). Myocyte death and myocyte regeneration in the failing human heart. Ital Heart J 2 (Suppl 3):12S–14S [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walsh S, Ponten A, Fleischmann BK. and Jovinge S. (2010). Cardiomyocyte cell cycle control and growth estimation in vivo—an analysis based on cardiomyocyte nuclei. Cardiovasc Res 86:365–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Senyo SE, Steinhauser ML, Pizzimenti CL, Yang VK, Cai L, Wang M, Wu TD, Guerquin-Kern JL, Lechene CP. and Lee RT. (2013). Mammalian heart renewal by pre-existing cardiomyocytes. Nature 493:433–436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soonpaa MH, Rubart M. and Field LJ. (2013). Challenges measuring cardiomyocyte renewal. Biochim Biophys Acta 1833:799–803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scholzen T. and Gerdes J. (2000). The Ki-67 protein: from the known and the unknown. J Cell Physiol 182:311–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carmena M. and Earnshaw WC. (2003). The cellular geography of aurora kinases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 4:842–854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laflamme MA. and Murry CE. (2011). Heart regeneration. Nature 473:326–335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laflamme MA. and Murry CE. (2005). Regenerating the heart. Nat Biotechnol 23:845–856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soonpaa MH. and Field LJ. (1997). Assessment of cardiomyocyte DNA synthesis in normal and injured adult mouse hearts. Am J Physiol 272:H220–H226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soonpaa MH. and Field LJ. (1998). Survey of studies examining mammalian cardiomyocyte DNA synthesis. Circ Res 83:15–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malliaras K, Zhang Y, Seinfeld J, Galang G, Tseliou E, Cheng K, Sun B, Aminzadeh M. and Marban E. (2013). Cardiomyocyte proliferation and progenitor cell recruitment underlie therapeutic regeneration after myocardial infarction in the adult mouse heart. EMBO Mol Med 5:191–209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bergmann O. and Jovinge S. (2012). Isolation of cardiomyocyte nuclei from post-mortem tissue. J Vis Exp. DOI: 10.3791/4205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bergmann O, Zdunek S, Frisen J, Bernard S, Druid H. and Jovinge S. (2012). Cardiomyocyte renewal in humans. Circ Res 110:e17–e18; author reply e19–e21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richardson GD, Breault D, Horrocks G, Cormack S, Hole N, Owens W.A. (2012). Telomerase expression marks putative stem cell populations in the mammalian heart. FASEB J 26:4832–4840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Merrick D, Stadler LK, Larner D. and Smith J. (2009). Muscular dystrophy begins early in embryonic development deriving from stem cell loss and disrupted skeletal muscle formation. Dis Model Mech 2:374–388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greally E, Davison BJ, Blain A, Laval S, Blamire A, Straub V. and MacGowan GA. (2013). Heterogeneous abnormalities of in-vivo left ventricular calcium influx and function in mouse models of muscular dystrophy cardiomyopathy. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 15:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Herget GW, Neuburger M, Plagwitz R. and Adler CP. (1997). DNA content, ploidy level and number of nuclei in the human heart after myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res 36:45–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mollova M, Bersell K, Walsh S, Savla J, Das LT, Park SY, Silberstein LE, Dos Remedios CG, Graham D, Colan S. and Kuhn B. (2013). Cardiomyocyte proliferation contributes to heart growth in young humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:1446–1451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li W, Liu W, Zhong J. and Yu X. (2009). Early manifestation of alteration in cardiac function in dystrophin deficient mdx mouse using 3D CMR tagging. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 11:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakamura A, Yoshida K, Takeda S, Dohi N. and Ikeda S. (2002). Progression of dystrophic features and activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases and calcineurin by physical exercise, in hearts of mdx mice. FEBS Lett 520:18–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stuckey DJ, Carr CA, Camelliti P, Tyler DJ, Davies KE. and Clarke K. (2012). In vivo MRI characterization of progressive cardiac dysfunction in the mdx mouse model of muscular dystrophy. PLoS One 7:e28569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sacco A, Mourkioti F, Tran R, Choi J, Llewellyn M, Kraft P, Shkreli M, Delp S, Pomerantz JH, Artandi SE. and Blau HM. (2010). Short telomeres and stem cell exhaustion model Duchenne muscular dystrophy in mdx/mTR mice. Cell 143:1059–1071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Torella D, Rota M, Nurzynska D, Musso E, Monsen A, Shiraishi I, Zias E, Walsh K, Rosenzweig A, et al. (2004). Cardiac stem cell and myocyte aging, heart failure, and insulin-like growth factor-1 overexpression. Circ Res 94:514–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anversa P, Rota M, Urbanek K, Hosoda T, Sonnenblick EH, Leri A, Kajstura J. and Bolli R. (2005). Myocardial aging—a stem cell problem. Basic Res Cardiol 100:482–493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anversa P, Fitzpatrick D, Argani S. and Capasso JM. (1991). Myocyte mitotic division in the aging mammalian rat heart. Circ Res 69:1159–1164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sussman MA. and Anversa P. (2004). Myocardial aging and senescence: where have the stem cells gone?. Annu Rev Physiol 66:29–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mourkioti F, Kustan J, Kraft P, Day JW, Zhao MM, Kost-Alimova M, Protopopov A, DePinho RA, Bernstein D, Meeker AK. and Blau HM. (2013). Role of telomere dysfunction in cardiac failure in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nat Cell Biol 15:895–904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chun JL, O'Brien R, Song MH, Wondrasch BF. and Berry SE. (2013). Injection of vessel-derived stem cells prevents dilated cardiomyopathy and promotes angiogenesis and endogenous cardiac stem cell proliferation in mdx/utrn-/- but not aged mdx mouse models for duchenne muscular dystrophy. Stem Cells Transl Med 2:68–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.