Abstract

BACKGROUND

Vascular endothelial growth factor-B (VEGF-B) activates cytoprotective/antiapoptotic and minimally angiogenic mechanisms via VEGF receptors. Therefore, VEGF-B might prove an ideal candidate for the treatment of dilated cardiomyopathy, which displays modest microvascular rarefaction and increased rate of apoptosis.

OBJECTIVES

We evaluated VEGF-B gene therapy in a canine model of tachypacing-induced dilated cardiomyopathy.

METHODS

Chronically instrumented dogs underwent cardiac tachypacing for 28 days. Adeno-associated-9 viral vectors carrying VEGF-B167 genes were infused intracoronarily at the beginning of the pacing protocol or during compensated heart failure (HF). Moreover, we tested a novel VEGF-B167 transgene controlled by the atrial natriuretic factor (ANF) promoter.

RESULTS

Compared to controls, VEGF-B167 markedly preserved diastolic and contractile function and attenuated ventricular chamber remodeling, halting the progression from compensated to decompensated HF. ANF-VEGF-B167 expression was low in normo-functioning hearts and stimulated by cardiac pacing; thus, it functioned as an ideal therapeutic transgene, active only under pathological conditions.

CONCLUSIONS

Our results, obtained with a standard technique of interventional cardiology in a clinically relevant animal model, support VEGF-B167 gene transfer as an affordable and highly effective new therapy for nonischemic HF.

Keywords: heart failure, gene therapy, translational approach

Gene transfer meets the need for novel molecular therapies targeting known molecular alterations that occur specifically in cardiac cells and cannot be reversed by conventional pharmacological agents. Therefore, despite initial hurdles, gene therapy remains an attractive, highly promising option to treat various pathological conditions, including heart failure (HF), especially as better-suited viral vectors have become available (1–3). One eloquent example is a recent phase II clinical trial demonstrating the great potential of cardiac gene therapy for HF with reduced ejection fraction (4).

Investigators have proposed various cardiac gene therapy strategies, depending on the target enzyme or structural protein they deem to be critically involved in compensatory or maladaptive cellular alterations. Over the past 5 years, we and others have shown the beneficial effects of vascular endothelial growth factor-B (VEGF-B) gene transfer in experimental models of cardiac injury (5–7). VEGF-B, one of the 5 members of the mammalian VEGFs family, is a major pro-survival, rather than pro-angiogenic, factor (8). It selectively binds VEGF receptor-1 (VEGFR-1), whereas the more extensively studied pro-angiogenic VEGF-A binds both VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2 (8). The marked cytoprotective/antiapoptotic (9) and minimally angiogenic action of VEGF-B renders it particularly well-suited for gene therapy of nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), a severe pathological condition not caused by coronary artery disease, in which the increased rate of apoptosis seems to play a major role (10–12). Unfortunately, no specific antiapoptotic pharmacologic agents are currently available to clinicians.

While much less frequent than ischemic disease, DCM remains largely untreatable yet is responsible for most U.S. cardiac transplants (13). VEGF-B-based cytoprotective therapy might prove successful in the fight against this severe pathological condition. Therefore, the present study aimed to: 1) validate a clinically applicable cardio-selective VEGF-B gene therapy in a large animal model of DCM; 2) test the efficacy of a safer approach based on inducible VEGF-B transgenes turned on and off in response to, respectively, the occurrence or remission of the pathological condition; and 3) test the hypothesis that VEGFR-1 is the principal mediator of the cytoprotective action exerted by VEGFs. We delivered VEGF-B167, the prevalent VEGF-B isoform (14), in canine tachypacing-induced HF, which is the best characterized model of DCM, reproducing numerous pathophysiological and molecular alterations of the human disease (7,15–17). Parallel experiments were carried out in cultured cardiomyocytes.

METHODS

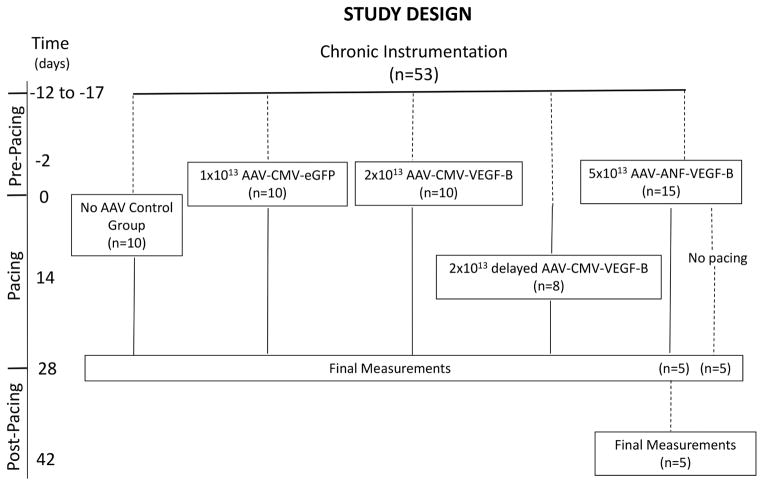

Fifty-three adult male, mongrel dogs (22 to25 kg body weight) were chronically instrumented as previously described (7,17,18, Online Appendix). The dogs were randomly divided into 5 experimental groups (Figure 1). Transgenes were encapsidated into serotype-9 adeno-associated virus (AAV9, henceforth indicated as AAV) and infused in the left coronary artery (anterior descending + circumflex branches) in 4 groups. Ten chronically instrumented dogs did not receive AAV. Intracoronary AAV delivery was performed 10 to 15 days after the surgical procedure or after 2 weeks of pacing (Figure 1). Dogs were lightly anesthetized (10 to 20 mg/kg pentobarbital intravenous); after local anesthesia, a 5-F sheath was inserted percutaneously into the right femoral artery for coronary catheterization. Left circumflex and anterior descending coronary arteries were selectively and alternatively catheterized using a 2.5-F micro-infusion catheter to infuse 20 ml of AAV suspension (1 × 1013 to 5 × 1013 viral particles [Figure 1]) in normal phosphate buffer solution containing 3 ng/kg adenosine and 5 ng/kg of substance P. The AAV suspension was administered slowly over 20 min followed by 10 min of intracoronary infusion of physiological saline solution. Simultaneously with AAV intracoronary delivery, 1 μg/kg/min of nitroglycerin was infused intravenously. Adenosine, substance P, and nitroglycerin were utilized to increase permeability in myocardial capillaries. Hemodynamics were recorded during this procedure until full post-anesthesia recovery.

FIGURE 1. Experimental Groupings.

Transgenes were encapsidated into serotype-9 adeno-associated virus (AAV) and infused in the left coronary artery (anterior descending + circumflex branches) in randomized groups of dogs. ANF = atrial natriuretic factor promoter; CMV = cytomegalovirus promoter; eGFP = enhanced green fluorescent protein; VEGF-B = vascular endothelial growth factor-B.

To induce HF, dogs were subjected to left ventricular (LV) pacing with an external pacemaker set at 210 beats/min for 3 weeks; the pacing rate was increased to 240 beats/min for an additional week. Based on our previous studies, this pacing protocol causes DCM and compensated HF during the first 3 weeks, culminating in severe heart failure at 27 to 30 days (17,18). We euthanized all the dogs at 28 days to compare in vivo and ex vivo data at a fixed time point.

The protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Temple University and conform to the guiding principles for the care and use of laboratory animals published by the National Institutes of Health.

Histological and polymerase chain reaction analysis of cardiac tissue was performed as previously described by us (6,7,19,20, Online Appendix).

To determine cytoprotective effects of VEGF-B167, neonatal rat cardiomyocytes were isolated and cultured with reactive oxygen specie (ROS) production measured as previously described (19,21,22). They were exposed to VEGF-B167, VEGF-A, VEGF-E, and placental growth factor (PlGF) in the absence or in the presence of angiotensin II or norepinephrine (50 M−6) (Online Appendix).

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical analysis was performed with commercially available software (SPSS Statistics, IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York). Hemodynamic, cardiac functional, histological, and molecular changes at different time points were compared by 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for repeated measures and comparisons between groups by 2-way ANOVA, in both cases followed by Student-Newman-Keuls post hoc test. When samples were not normally distributed, a nonparametric test was used and data presented as box plots. For all statistical analyses, significance was accepted at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

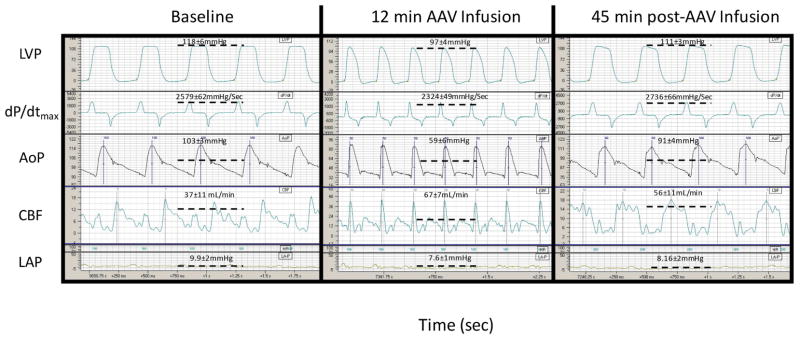

Intracoronary gene delivery was hemodynamically well tolerated. Co-infusion of vasodilators such as adenosine, nitroglycerin, and substance P during intracoronary AAV delivery caused the following reversible changes (Figure 2): increased coronary blood flow, decreased systolic pressure (~20 mm Hg), and altered LV pressure waveform shape during the diastolic phase, reflected by decreased dP/dtmin. Left atrial pressure was not affected.

FIGURE 2. Minor Hemodynamic Changes during Intracoronary AAV Delivery.

Representative hemodynamic tracings simultaneously recorded through chronically implanted probes and catheters before, during, and after AAV intracoronary delivery. The scale was automatically adjusted by the acquisition system and differs in the 3 panels. AoP = aortic pressure (with mean pressure average value); CBF = blood flow in the circumflex coronary artery (with mean flow average value); dP/dt = first derivative of left LV pressure (with dP/dtmax average value); LAP = left atrial pressure (with mean pressure average value); LV = left ventricular; LVP = LV pressure (with systolic pressure average value); other abbreviations as in Figure 1.

Mouse VEGF-B167 (henceforth indicated as VEGF-B) gene or the green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter gene, both controlled by the constitutively active cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter, were delivered to 2 groups (Figure 1). One group received 1 × 1013 AAV9-CMV-GFP (used as control) and the other 2 × 1013 AAV-CMV-VEGF-B. AAV administered 2 days before starting the pacing protocol allowed time for transgene expression, which typically takes ~10 days when carried by this type of viral vector (3). To rule out the possibility that early gene transfer could have exerted a preemptive action, 1 group of dogs received 2 × 1013 AAV-CMV-VEGF-B in the left coronary artery after 2 weeks of pacing, at a stage of compensated HF, thus simulating a more realistic clinical scenario. All the functional measurements were acquired at spontaneous heart rate, with the pacemaker turned off.

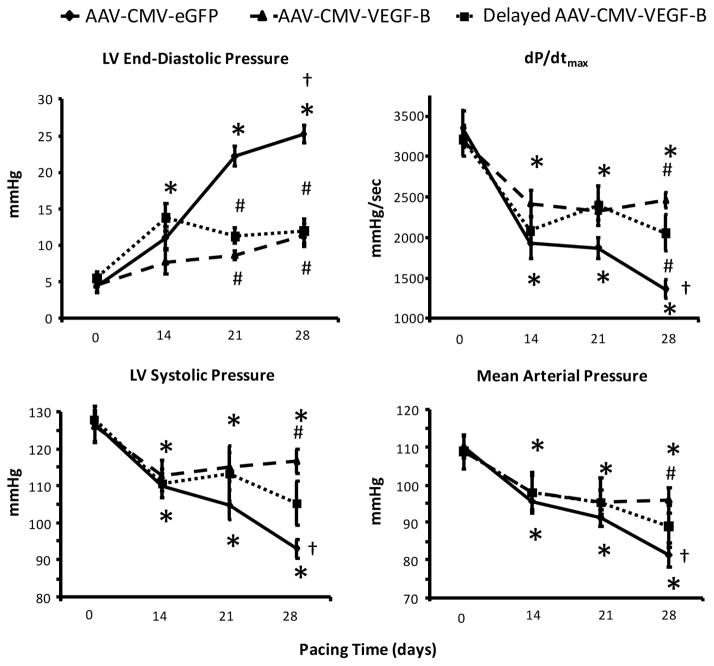

Dogs transduced with GFP displayed the typical progressive deterioration of hemodynamic parameters over 4 weeks (Figure 3), as previously described (17,18); this time course was not significantly different compared to nontransduced dogs undergoing cardiac pacing (Online Figure 1). At 28 days, LV end-diastolic pressure (LVEDP) increased to approximately 25 mm Hg, indicating congestive, decompensated HF. Conversely, cardiac transduction with VEGF-B markedly attenuated the hemodynamic derangement. The most notable effect was no significant change during the entire pacing period in LVEDP in those dogs transduced early; in the delayed-transduction group, further increases were prevented after the second week. LV systolic pressure, mean arterial pressure, and dP/dtmax, although significantly decreased after 2 weeks of pacing compared to baseline, did not display a further significant fall afterwards in the 2 groups transduced with VEGF-B. Finally, coronary blood flow did not change significantly over time in any of the groups (Online Figure 2). Therefore, compared to the control HF group, VEGF-B gene delivery halted the transition from compensated to decompensated HF, even in hearts with significant functional impairment.

FIGURE 3. VEGF-B Gene Transfer Halts the Progression to Decompensated HF.

Gene transfer therapy appears effective in halting heart failure (HF) progression as seen in comparisons between main hemodynamic changes, over 4 weeks of chronic cardiac pacing, in dogs with intracoronary infusion of AAV-CMV-GFP (control, n = 10) or AAV-CMV-VEGF-B. This latter was administered at the beginning of the pacing protocol (n = 10) or after 14 days of pacing (delayed AAV-CMV-VEGF-B, n = 8). *p < 0.05 versus day 0 (baseline) within group; †p < 0.05 versus day 14 within group; #p < 0.05 versus AAV-CMV-GFP at the same time point. Other abbreviations as in Figures 1 and 2.

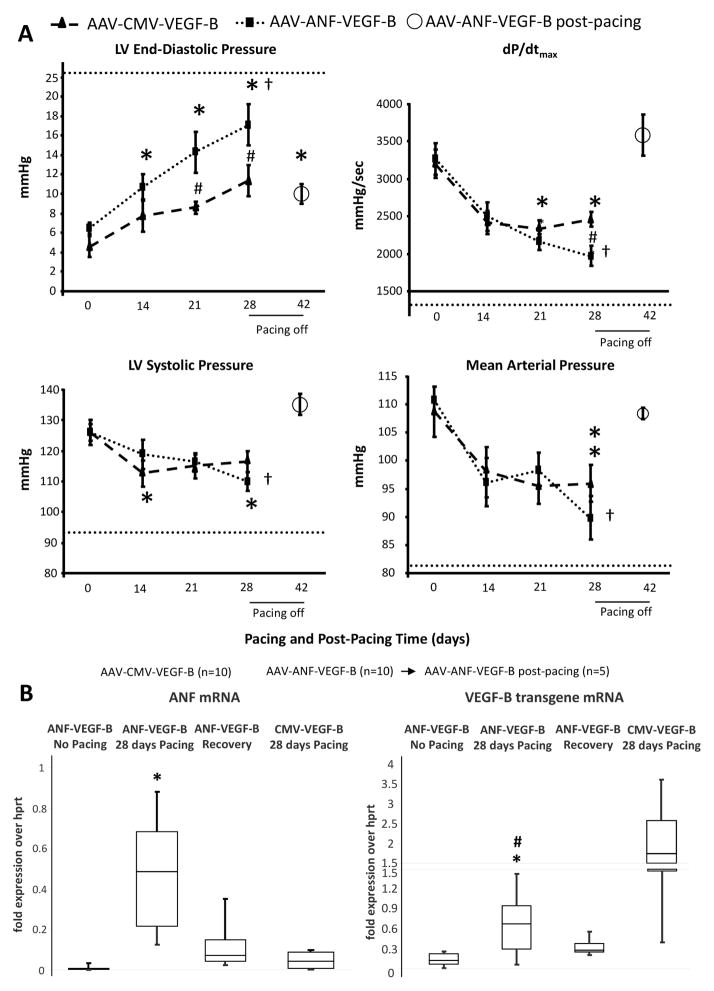

A desirable strategy in gene therapy would be based on inducible transgenes turned on and off in response to, respectively, the occurrence or remission of the pathological condition. We therefore generated a construct consisting of the 5′ flanking region −638/+62 of the rat atrial natriuretic factor (ANF), which includes most of the ANF promoter and enhancer, linked to the VEGF-B gene. Our goal was to obtain VEGF-B expression only in response to intracellular ANF inducers, adopting a previously validated strategy (23,24). ANF is expressed in failing but not normal ventricles (25,26), therefore VEGF-B would be expressed only during HF development. We first tested the responsiveness of the ANF 5′ flanking region −638/+62 linked to GFP in a plasmid to transfect cultured rat neonatal cardiomyocytes stimulated with isoproterenol, a known ANF inducer (27) (Online Figure 3). In response to isoproterenol, the ANF element was able to drive approximately one-third of the GFP expression found in cells transfected with CMV-GFP. To compensate for the weaker promoter in vivo, we delivered 5 × 1013 AAV carrying ANF-VEGF-B in the left coronary artery of 15 dogs, 2 days before starting the pacing protocol (Figure 1). As a control, 5 of these dogs did not undergo cardiac pacing and were sacrificed 28 days later. Figure 4A shows that LVEDP and dP/dtmax were significantly more altered compared to the AAV-CMV-VEGF-B group; however, they remained within levels consistent with moderate/compensated HF. Alternatively, LV systolic and mean arterial pressures were not significantly different between the 2 groups. Nonpaced dogs did not show any significant functional and morphological change over time (data not shown).

FIGURE 4. ANF-VEGF-B: Inducible Therapeutic Transgene.

(A) Comparison between the main hemodynamic changes, over 4 weeks of chronic cardiac pacing, in dogs with intracoronary infusion of AAV-CMV-VEGF-B or AAV-ANF-VEGF-B (n = 10 per group). Five dogs receiving AAV-ANF-VEGF-B where followed for an additional period of 14 days after stopping cardiac pacing (post-pacing). The dotted line in each panel indicates the average value of the respective hemodynamic parameter found in the control group after 28 days of pacing (as in Figure 2). *p < 0.05 versus day 0 (baseline) within group; †p < 0.05 versus day 14 within group; #p < 0.05 versus AAV-CMV-GFP at the same time point.(B) Gene expression of ANF, CMV-VEGF-B and ANF-VEGF-B in LV. Messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) was quantified as fold expression of the housekeeping hypoxanthine phosphoribosyl-transferase (hprt); n= 5 for all groups; data are medians with percentiles; *p < 0.05 versus control (hearts transduced with ANF-VEGF-B, but not undergoing pacing); # p < 0.05 versus CMV-VEGF-B. Other abbreviations as in Figures 1 and 2.

A peculiarity of tachypacing-induced HF is its gradual functional recovery over a few weeks after restoration of spontaneous heart rate (18,28). We exploited this characteristic to test whether ANF-VEGF-B gene expression was silenced after post-failure recovery. In 5 of the 15 dogs transduced with ANF-VEGF-B, the pacemaker was disconnected after 28 days of pacing, the functional parameters monitored, and the animals euthanized 2 weeks later. As expected, these dogs’ hemodynamic values returned to normal or quasi-normal values (Figure 4A). We chose this time point, based on a previous study in a similar dog model, in which circulating ANF was found already normalized 1 week after turning the pacemaker off (28). We found a marked and significant increase in median ANF gene expression (normalized by the housekeeping gene hprt) in HF versus normal LV tissue, 0.86 (range: 0.2 to 1.85) versus 0.03 (range: 0.03 to 0.06). Similarly, ANF expression was very low in hearts not subjected to pacing and transduced with ANF-VEGF-B, although ANF-VEGF-B was mildly expressed in the LV, likely due to some degree of basal transcription, also noticed in vitro (Online Figure 3).

However, ANF-VEGF-B transgene expression markedly increased in LV tissue after 28 days of pacing, consistent with pathological ANF upregulation, returning to almost control levels after post-pacing functional recovery when ANF levels were normalized (Figure 4B). Of note, ANF-VEGF-B gene expression in LV tissue was significantly lower than CMV-VEGF-B expression (Figure 4B), which could explain in part the difference between the effects of the 2 therapeutic approaches on hemodynamics. Furthermore, hearts transduced with CMV-VEGF displayed ANF levels not significantly different from nonpaced hearts (Figure 4B).

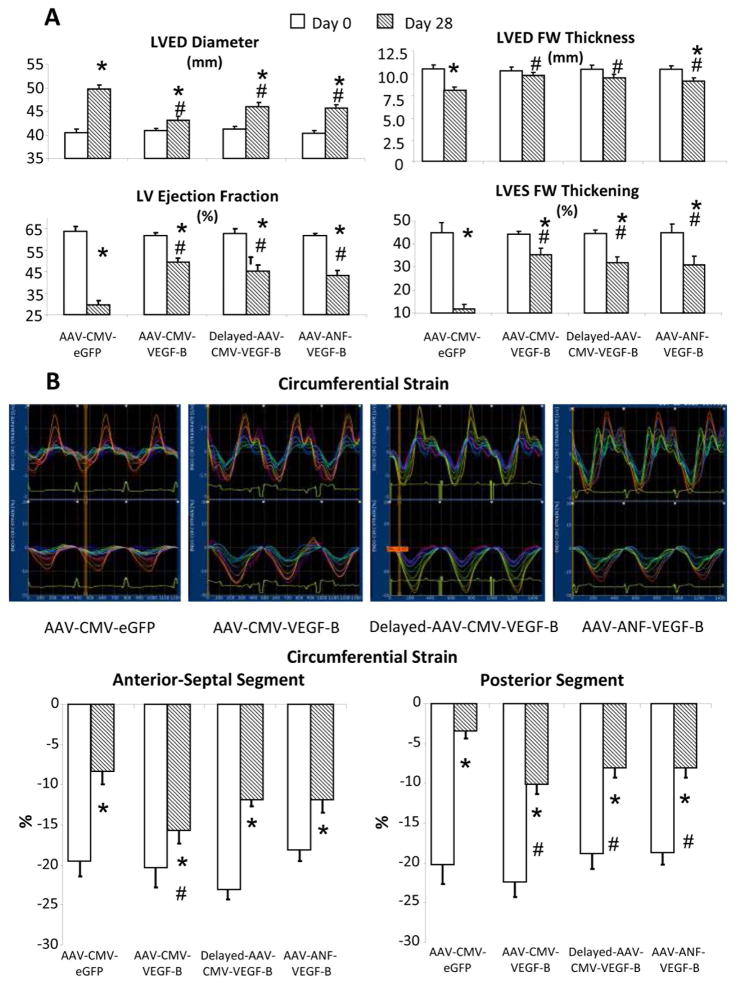

LV end-diastolic diameter increased by approximately 25% and LV end-diastolic thickness decreased by approximately 30% after 28 days of pacing in hearts transduced with GFP, indicating DCM development (Figure 5A) (17,18,28,29). The increase in diameter was significantly attenuated by AAV-CMV-VEGF-B as well as AAV-ANF-VEGF-B administration. Such beneficial effect was even more pronounced on LV end-diastolic thickness. Cardiac remodeling in control HF was associated with >50% reduction in LV ejection fraction (LVEF) and >70% reduction in LV systolic wall thickening, 2 commonly used indexes of contractility. Cardiac transduction with both CMV-VEGF-B and ANF-VEGF-B attenuated these changes, although they remained significant versus baseline. LV tachypacing causes dyssynchronous contraction, leading to an asymmetric contractile impairment, more pronounced in the LV free wall compared to septum (30).

FIGURE 5. VEGF-B Gene Transfer in Chronic Tachypacing.

VEGF-B attenuates cardiac function and morphological derangement as seen in (A) echocardiographic parameters and (B) strain analysis with representative tracings recorded at 28 days of pacing. The latter include strain rate (upper) and circumferential strain (lower). The colored lines indicate different segments of the LV circumference, from the posterior-alter wall (blue lines) to the antero-septal wall (orange lines). Measurements were taken with the pacemaker off. Group sizes as for Figures 1 and 2. *p < 0.05 versus day 0; #p < 0.05 versus AAV-CMV-GFP at 28 days. LVED = end-diastolic; LVES = LV end-systolic; FW= free wall; other abbreviations as in Figures 1 and 2.

In our experiments, we delivered AAV intracoronarily, without targeting specific regions of the heart. Therefore we assessed whether gene therapy was similarly beneficial in the LV free wall and septum. Echocardiography-based strain analysis was employed to assess maximal circumferential shortening of the 2 opposite walls of the LV chamber. We confirmed the asymmetric functional impairment, which was significantly reduced in both LV sites, but circumferential shortening was more preserved in hearts receiving the VEGF-B transgene (Figure 5B). However, the best protective effect in septum occurred in hearts that received AAV-CMV-VEGF-B at the beginning of the pacing protocol.

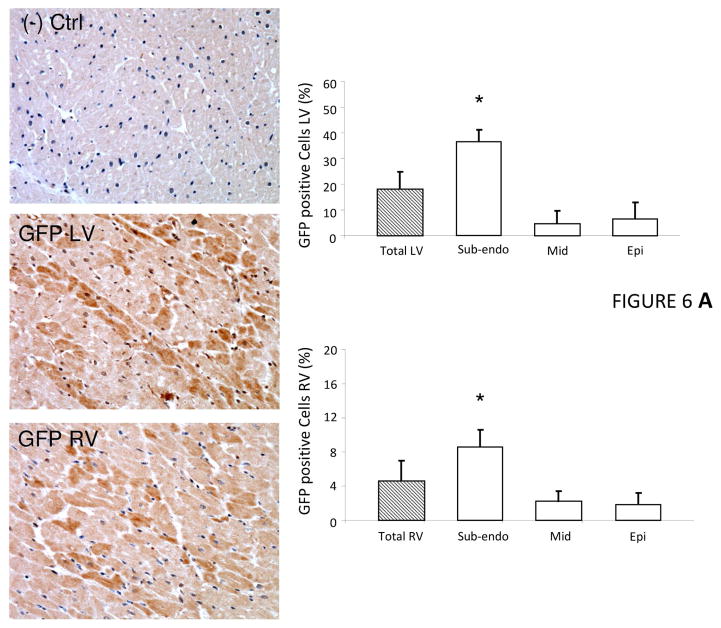

The significant functional effects of VEGF-B gene delivery indicated achievement of an adequate, therapeutic level of myocardial transduction. By localizing the reporter gene GFP expression with immunohistochemistry in the control HF group, we could precisely quantify the percent and topographic distribution of transduced cells after intracoronary gene delivery. In both the LV and right ventricle, transduction efficiency ranged widely from a maximal value in the subendocardial layers of the myocardium to a minimal value in the subepicardial layers (Figure 6A). Normal control, nontransduced cardiac tissue was obtained from chronically instrumented dogs sacrificed for unrelated studies. Overall, expression efficiency was higher in the left versus the right ventricle.

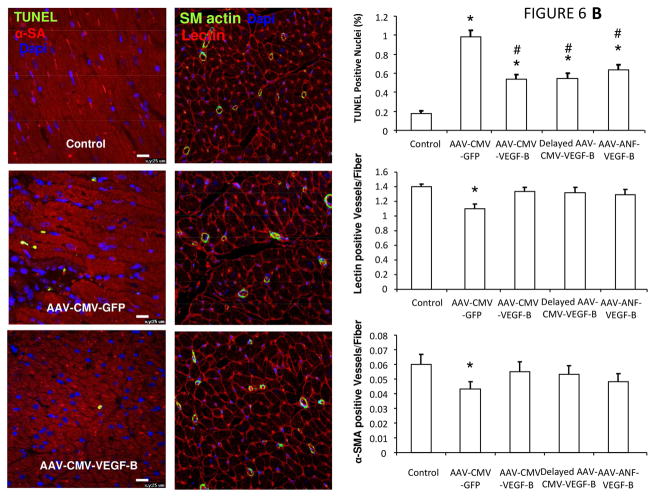

FIGURE 6. Transduction Efficiency.

(A) Immunohistochemical detection of GFP in cardiac tissue demonstrated heterogeneous transduction efficiency after intracoronary AAV delivery. Representative photomicrographs from negative control, left ventricle (LV) and right ventricle (RV); n = 5 per group. (B) VEGF-B gene transfer attenuated myocardial apoptosis and prevented microvascular rarefaction. Nuclei are stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), apoptotic nuclei identified by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL), and cardiomyocytes stained with α-sarcomeric actin (α-SA); n = 5 per group. Microvascular density normalized by the number of cardiomyocyte fibers; total microvessel numbers were quantified by immunofluorescence staining for endothelial cells (lectin positive), whereas microvessels with muscular wall were identified by positive immunofluorescence staining of smooth muscle actin (SM actin). *p <0.05 vs Normal; #p <0.05 vs AAV-CMV-GFP. Epo = subepicardial; Mid = mid-myocardial; Subendo = subepicardial; other abbreviations as in Figures 1 and 2.

Increased myocardial apoptosis is a known hallmark of human and experimental DCM (10–12,15). Histochemical analysis indicated a reduced percentage of apoptotic cells after 28 days of pacing in hearts transduced with CMV-VEGF-B or ANF-VEGF-B compared to control HF (Figure 6B). Another characteristic of DCM, the absence of major lesions of large coronary arteries associated with myocardial microvascular rarefaction (16), was confirmed in our canine HF model, and CMV-VEGF-B or ANF-VEGF-B gene transfer preserved the density of capillaries and smooth muscle actin-positive microvessels (Figure 6B). Finally, the number of T lymphocytes in myocardium did not change significantly in any of the transduced compared to nontransduced hearts after 28 days of pacing (Online Figure 4).

VEGF-B ACTIVATES ANTIOXIDANT DEFENSES

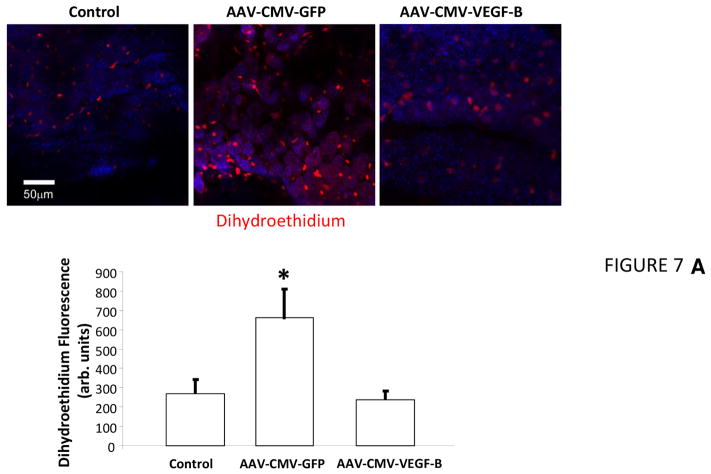

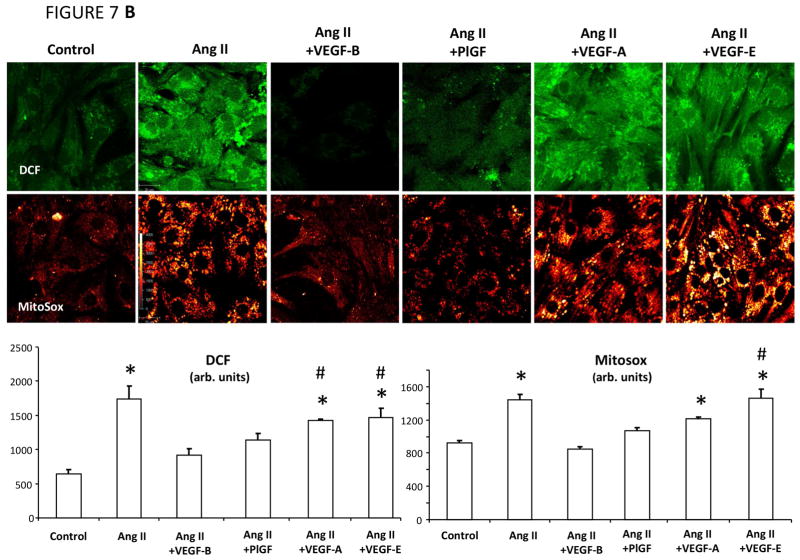

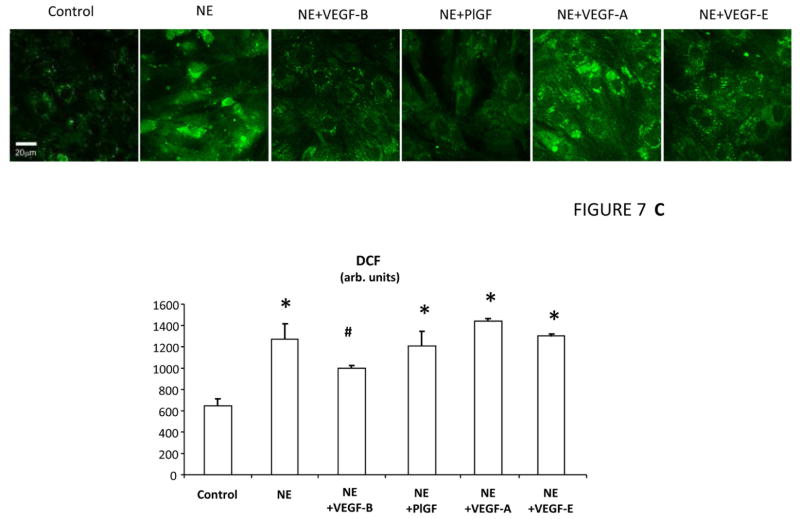

Dihydroethidium staining of cross-sections from freshly harvested LV tissue and subsequent quantification of fluorescence intensity (19) indicated increased ROS production in failing versus normal hearts (Figure 7A). ROS production was significantly lower in tissue slices harvested from paced hearts that had been transduced with VEGF-B. Therefore, we performed experiments in cultured rat neonatal cardiomyocytes to test whether: 1) VEGF-B attenuates ROS generation in response to both of angiotensin II and norepinephrine, 2 major promoters of oxidative stress (31,32); and 2) these effects are specific of VEGF-R1 ligands or shared by VEGF-R2 ligands. We compared VEGF-B with PlGF (another selective VEGF-R1 ligand), VEGF-A (a ligand of both VEGF-R1 and VEGF-R2) (8), and VEGF-E (selective VEGF-R2 ligand) (33). Figure 7B shows that increased mitochondrial superoxide and cytosolic H2O2 production, detected, respectively, by MitoSox red and 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCF), were significantly attenuated only by VEGF-B and PlGF, but not by equivalent concentrations of VEGF-A and -E. Conversely, norepinephrine-induced cytosolic ROS elevation was attenuated in neonatal cardiomyocytes pretreated with VEGF-B, but not PlGF, VEGF-A, or VEGF-E (Figure 7C).

FIGURE 7. VEGFR-1 agonists activate Antioxidant Defenses in Cardiomyocytes.

Panel A. Use of VEGF receptor-1 agonists to activate antioxidant defenses in cardiomyocytes is seen in (A) representative photomicrographs and quantification of superoxide detection by dihydroethdium (DHE) in cardiac tissue slices; n = 3 per group; (B) representative images in angiotensin II (Ang II)-treated cultured neonatal cardiomyocytes showing fluorescence of MitoSox (detecting mitochondrial superoxide) and 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCF, detecting cytosolic H2O2 ) and relative quantifications in the bar graph; n = 5–12 per group; and (C) representative images showing DCF fluorescence in norepinephrine (NE)-treated cultured neonatal cardiomyocyte and relative quantifications in the bar graph; n = 5–12 per group. *p < 0.05 versus control; #p < 0.05 versus VEGF-B; †p < 0.05 versus Ang II + VEGF-B. PlGF = placental growth factor; other abbreviations as in Figures 1 and 2.

Next, we explored the most obvious mechanisms potentially involved in the protection against angiotensin II, namely mitochondrial superoxide dismutase (SOD2) potentiation and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase inhibition. Pretreatment of cultured cardiomyocytes with short-interfering ribonucleic acid (siRNA) against SOD2 enhanced the MitoSox signal in response to angiotensin II (Online Figure 5), confirming the importance of this enzyme as a mitochondrial antioxidant defense. Importantly, the anti-SOD2 siRNA abrogated the beneficial effects of VEGF-B.

The activation of the isoform 2 of the superoxide-generating enzyme NADPH oxidase (NOx2) in response to angiotensin II was tested by quantifying the translocation of the enzyme subunit p47 to plasma membrane rafts, a mandatory step for the assembling of this enzyme complex. Angiotensin II caused a marked translocation of p47 to plasma membrane, as expected, which was largely prevented by VEGF-B but not by VEGF-A (Online Figure 5). However, VEGF-B did not affect the Nox2 catalytic sub-unit gp91phox protein expression (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

We previously provided proof of concept of the beneficial effects of VEGF-B167 gene delivery by direct intramyocardial injections in canine pacing-induced HF, while VEFG-A was ineffective (7). The present study successfully addresses remaining important questions; i.e., whether intracoronary AAV-VEGF-B infusion, more realistic in clinical practice, is similarly effective and whether VEGFR-1 is the sole mediator of cardiomyocyte protection against oxidative stress.

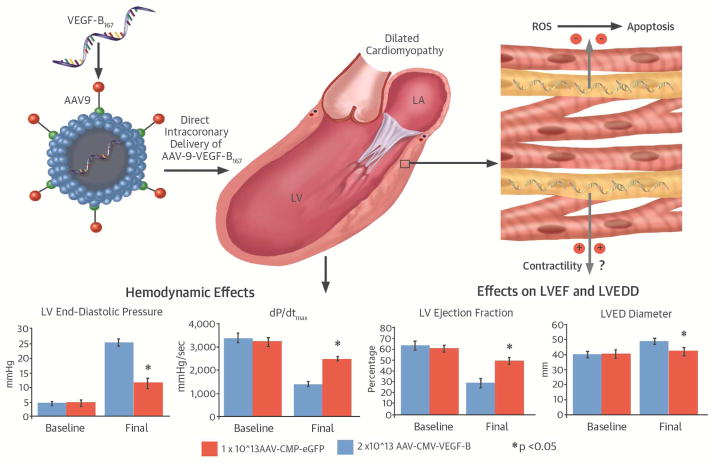

Different from intramyocardial injections, intravascular infusions are challenging, since viral vectors can be rapidly flushed away from the target cells. We found that intracoronary AAV-VEGF-B delivery, carried out with procedures feasible at any coronary catheterization unit, was well tolerated and displayed marked therapeutic efficacy, halting progression towards decompensated HF (Central Illustration). Hemodynamic alterations and cardiac remodeling were blunted if not completely prevented and consistently, at tissue level, the rate of apoptosis (a major DCM pathogenic determinant) was markedly reduced. Of note, LVEDP, an index of central congestion and diastolic dysfunction, remained within the almost physiological range of 6 to 10 mm Hg even after 28 days of tachypacing. Considering the severity and the elevated cardiac stress characterizing this model of HF, such results are promising.

CENTRAL ILLUSTRATION. VEGF-B167 Gene Therapy in Dilated Cardiomyopathy.

Intracoronary infusion of adeno-associated virus serotype 9 (AAV)-vascular endothelial growth factor-B (VEGF-B) delays development of pacing-induced heart failure. A putative cardioprotective mechanism is inhibition of reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, which, in turn would prevent apoptotic cell death (upper panel). This and other potential mechanisms preserve cardiac function in the VEGF-B-treated group compared to the green fluorescent protein (GFP) control group as indicated, for instance, by the left ventricular end-diastolic pressure (LVEDP) and end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD) as well as by the higher dP/dtmax and LV ejection fraction (LVEF; bottom panel).

Another important aspect: the equally high therapeutic efficacy of AAV-VEGF-B delivered to dogs with compensated HF, corresponding to the stage when most patients seek medical care for initial symptoms. In those dogs, gene therapy prevented further worsening of any functional alteration already developed after 2 weeks of pacing. Such rapidly occurring beneficial effect suggests that VEGF-B-mediated cytoprotection may not be the only mechanism involved. Other authors have found that VEGF-R1 agonists stimulate contractility by enhancing cytosolic calcium ion transients in neonatal ventricular myocytes (34); therefore, part of the therapeutic action we found in dogs could be due to direct support of contractile function. It is known that myocardial VEGFR-1 is downregulated in DCM, while VEGF-B does not change significantly (7,16).

Although intracoronary AAV infusion has been previously used in several large animal and human studies, to our knowledge, no detailed description of myocardial transduction efficiency and regional heterogeneities was provided. We chose the serotype AAV9 for its known cardiotropism (3,35). However, by using the GFP reporter, we found that the transduction efficiency was relatively high only in the subendocardial layers of ventricular walls and minimal in others. This finding was surprising; nonetheless, it supported the high efficacy/transduction ratio attained with AAV-VEGF-B. Conceivably, the action of VEGF-B synthesized in transduced cells extended to remote cells in a paracrine fashion.

Dogs with sustained VEGF-B expression were observed for a maximum period of 6 weeks. During that time, we did not detect any clinical or functional change indicative of harmful side effects; cardiac tissue analysis did not reveal specific alterations, including a possible increase in T lymphocyte infiltration. We did not expect any, because other authors found only moderate morphological and no functional alterations in transgenic mice with cardiac-specific VEGF-B overexepression (36). However, definitive conclusions about side effects will require long-term monitoring of dogs transduced with VEGF-B, since this factor has also been implicated in pathological processes (37). In this regard, an important finding of the present study is the curative efficacy achieved with very mild, hence theoretically safe, myocardial transduction. Moreover, we tested the inducible transgene strategy, which renders unnecessary the CMV promoter, further reducing possible risks related to long-term expression. Ideally, therapeutic transgenes should be induced by pathological molecular changes and silenced when the curative effect has been achieved. This strategy is not novel (38,39), but has not been previously applied to cardiac gene therapy in large animal models. The present results are very encouraging, since, similar to ANF, ANF-VEGF-B expression increased in response to chronic pacing and proved at least in part therapeutically efficacious. The reversibility of transgene expression was indicated by the return of ANF-VEGF-B messenger RNA to low control levels after post-pacing recovery, mirroring LV ANF normalization. Additional testing will help refine this strategy and maximize its efficacy.

CYTOPROTECTIVE MECHANISMS

Oxidative stress is increased in HF and has been proposed as a primary pathogenic factor responsible for progressive cardiac tissue damage (31,32,40–43). Angiotensin II and norepinephrine, 2 mediators whose production/release is abnormally upregulated in failing hearts, promote oxidative stress by activating Nox2 (31) and feeding the H2O2-generating enzyme mono amino oxidase (32). The present, novel finding is that only the selective VEGFR-1 ligands VEGF-B and PlGF prevented mitochondrial superoxide and cytosolic H2O2 overproduction in cultured neonatal cardiomyocytes exposed to angiotensin II. VEGF-A, a dual VEGFR-1 and -2 ligand, exerted a smaller, nonsignificant effect, while VEGF-E, a selective VEGFR-2 ligand, was completely ineffective. We further showed, for the first time, that VEGF-B, but not the other members of the VEGF family, could mitigate H2O2 overproduction in cultured cardiomyocytes exposed to norepinephrine. These results strongly suggest that an important mechanism underlying the therapeutic action of VEGF-B, in vivo, might consist of antagonizing the pro-oxidant effects of angiotensin II and norepinephrine.

Our data also suggest that antioxidant effects are exerted only by the VEGFR-1 ligands of the VEGF family, which perhaps can explain why, in our prior study, VEGF-A gene transfer did not prove beneficial in tachypacing-induced HF (7). Redox equilibrium is finely regulated by a conspicuous number of pro- and antioxidant enzymes. However, in view of future investigations, we focused on 2 major enzymes: SOD2, a mitochondrial defense against superoxide generation, and Nox2, the superoxide-generating enzyme activated by angiotensin II. The excess mitochondrial superoxide production in cells exposed to angiotensin II could not be prevented by VEGF-B when SOD2 overexpression was prevented by a specific siRNA, indicating this enzyme’s important involvement. Moreover, VEGF-B blocked the activation of Nox2. We tested these mechanisms in cardiomyocytes, but we cannot exclude that the protective action of VEGF-B in the intact heart benefits other important cell types such as endothelium and fibroblasts.

LIMITATIONS

At least 3 limitations of our study should be acknowledged. First, due to the characteristics of our dog model, we could only test the therapeutic effects of VEGF-B gene transfer over a relatively short period, while human chronic heart failure develops over many years. Second, as other authors, we performed our in vitro studies in neonatal cardiomyocytes since, compared to adult cardiomyocytes, they are easier to obtain in large quantities for numerous experiments and to be stably maintained in culture for days without undergoing degenerative processes. However, we performed some additional tests in isolated adult cardiomyocytes and found similar responses to angiotensin II and VEGF-B, supporting the reliability of our results in neonatal cardiomyocytes. Finally, our experiments aimed at identifying molecular mechanisms responsible for the protective effects of VEGFR-1 ligands against oxidative stress are very preliminary and warrant more in depth studies at cellular level.

CONCLUSIONS

In this preclinical model, VEGF-B gene transfer emerges as an efficacious and safe therapy for DCM. The perspective of blocking with a single intracoronary infusion, at early stages of HF, the malignant evolution of cellular/molecular processes otherwise hardly delayed by chronic poly-pharmacological treatments is very appealing.

Supplementary Material

Measurements were taken with the pacemaker off. n=10 in both groups; *P<0.05 vs day 0 (baseline) within the group; †P<0.05 vs day 14 within the group.

Measurements were taken with the pacemaker off. n=10 in HF control, AAV-GFP and AAV-CMV-VEGF-B and n=5 for the AAV-ANF-VEGF-B. No significant differences were detected.

The transgene was tested in cultured neonatal cardiomyocytes exposed to 100 M−6 isoproterenol. The experiments were performed in triplicates.

The upper panel shows representative photomicrographs from LV tissue samples for each of the experimental conditions. One CD3+ cell per picture is indicated by an arrow. Bar= 50 μm. The lower panel shows the cell quantification. n=4 per group. In each sample, T lymphocytes were counted in 20 randomly selected filed at 10x magnification.

(A). Mitochondrial superoxide dismutase (SOD2) protein expression in cultured neonatal rat cardiomyocytes exposed to VEGF-B and representative images of MitoSox fluorescence in cultured neonatal cardiomyocytes exposed to Ang II without and with short-interfering (si)RNA to knock down SOD2; n=4 per group. *p < 0.05 versus control; #p < 0.05 versus AngII + VEGF-

(B). In cultured neonatal rat cardiomyocytes, Ang II induced translocation of the sub-unit p47 to caveolin 3 (Cav3)-enriched sarcolemmal fractions (lipid rafts, especially fractions 5 to 7) separated by ultracentrifugation, indicating the activation of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate complex. This activation was prevented by VEGF-B.

Perspectives.

Competency in Medical Knowledge

Pharmacological options for treatment of patients with dilated cardiomyopathy are currently limited, but gene delivery of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF-B) can activate cytoprotective mechanisms in myocardium and was efficacious in a pre-clinical model of this disease state.

Translational Outlook

Further research involving large animals are needed to more fully evaluate the potential of therapy with transgenes and using various viral vectors and modalities of delivery for treatment of dilated cardiomyopathy and other myocardial disorders.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the NIH grants P01 HL-74237 and R01 HL-108213 (F.A.R.), HL-33921 and P01 HL-100806 (S.H.), R01 HL086699, R01 HL119306 and 1S10RR 027327-01 (M.M.), HL076799 and HL088626 (A.S.) and from the Advanced Grant 250124 from the European Research Council and the FIRB RBAP11Z4Z9 from the MIUR, Italy (M.G.)

We are grateful to Sandhya Vallem for her valuable assistance with the in vitro ROS detection analysis, and to Dr. John Edwards, New York Medical College, who provided the ANF promoter and enhancer.

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

- AAV

adeno-associated virus serotype 9

- ANF

atrial natriuretic factor/protein

- CMV

cytomegalovirus

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SOD2

mitochondrial superoxide dismutase

- VEGF-B

vascular endothelial growth factor-B

- VEGFR-1

vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1

Footnotes

There are no relationships or financial associations with industry for any of the authors that would pose a conflict of interest in connection with the work.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Pleger ST, Brinks H, Ritterhoff J, et al. Heart failure gene therapy: the path to clinical practice. Circ Res. 2013;113:792–809. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.300269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asokan A, Samulski RJ. An emerging adeno-associated viral vector pipeline for cardiac gene therapy. Hum Gene Ther. 2013;24:906–13. doi: 10.1089/hum.2013.2515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zacchigna S, Zentilin L, Giacca M. Adeno-associated virus vectors as therapeutic and investigational tools in the cardiovascular system. Circ Res. 2014;114:1827–46. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.302331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greenberg B, Yaroshinsky A, Zsebo KM, et al. Design of a phase 2b trial of intracoronary administration of AAV1/SERCA2a in patients with advanced heart failure: the CUPID 2 trial (calcium up-regulation by percutaneous administration of gene therapy in cardiac disease phase 2b) JACC Heart Fail. 2014;2:84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lähteenvuo JE, Lähteenvuo MT, Kivelä A, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor-B induces myocardium-specific angiogenesis and arteriogenesis via vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1- and neuropilin receptor-1-dependent mechanisms. Circulation. 2009;119:845–56. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.816454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zentilin L, Puligadda U, Lionetti V, et al. Cardiomyocyte VEGFR-1 activation by VEGF-B induces compensatory hypertrophy and preserves cardiac function after myocardial infarction. FASEB J. 2010;24:1467–78. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-143180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pepe M, Mamdani M, Zentilin L, et al. Intramyocardial VEGF-B167 gene delivery delays the progression towards congestive failure in dogs with pacing-induced dilated cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 2010;106:1893–903. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.220855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bry M, Kivelä R, Leppänen VM, Alitalo K. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor-B in Physiology and Disease. Physiol Rev. 2014;94:779–94. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00028.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li Y, Zhang F, Nagai N, et al. VEGF-B inhibits apoptosis via VEGFR-1-mediated suppression of the expression of BH3-only protein genes in mice and rats. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:913–23. doi: 10.1172/JCI33673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Narula J, Haider N, Virmani R, et al. Apoptosis in myocytes in end-stage heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1182–89. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199610173351603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olivetti G, Abbi R, Quaini F, et al. Apoptosis in the failing human heart. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1131–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704173361603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saraste A, Pulkki K, Kallajoki M, et al. Cardiomyocyte apoptosis and progression of heart failure to transplantation. Eur J Clin Invest. 1999;29:380–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.1999.00481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Everly MJ. Cardiac transplantation in the United States: an analysis of the UNOS registry. Clin Transpl. 2008:35–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olofsson B, Jeltsch M, Eriksson U, Alitalo K. Current biology of VEGF-B and VEGF-C. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1999;10:528–35. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(99)00024-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cesselli D, Jakoniuk I, Barlucchi L, et al. Oxidative stress-mediated cardiac cell death is a major determinant of ventricular dysfunction and failure in dog dilated cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 2001;89:279–86. doi: 10.1161/hh1501.094115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abraham D, Hofbauer R, Schäfer R, et al. Selective downregulation of VEGFA (165), VEGF-R(1), and decreased capillary density in patients with dilative but not ischemic cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 2000;87:644–7. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.8.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Recchia FA, McConnell PI, Bernstein RD, Vogel TR, Xu X, Hintze TH. Reduced nitric oxide production and altered myocardial metabolism during the decompensation of pacing-induced heart failure in the conscious dog. Circ Res. 1998;83:969–79. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.10.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qanud K, Mamdani M, Pepe M, et al. Reverse changes in cardiac substrate oxidation in dogs recovering from heart failure. Am J Physiol. 2008;295:H2098–105. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00471.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vagnozzi RJ, Gatto GJ, Jr, Kallander LS, et al. Inhibition of the cardiomyocyte-specific kinase TNNI3K limits oxidative stress, injury, and adverse remodeling in the ischemic heart. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:207ra141. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3006479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rafiq K, Kolpakov MA, Seqqat R, et al. c-Cbl inhibition improves cardiac function and survival in response to myocardial ischemia. Circulation. 2014;129:2031–43. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.007004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hawkins BJ, Levin MD, Doonan PJ, et al. Mitochondrial complex II prevents hypoxic but not calcium- and proapoptotic Bcl-2 protein-induced mitochondrial membrane potential loss. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:26494–505. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.143164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang B, Rizzo V. TNF-alpha potentiates protein-tyrosine nitration through activation of NADPH oxidase and eNOS localized in membrane rafts and caveolae of bovine aortic endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H954–62. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00758.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.von Harsdorf R, Edwards JG, Shen YT, et al. Identification of a cis-acting regulatory element conferring inducibility of the atrial natriuretic factor gene in acute pressure overload. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:1294–304. doi: 10.1172/JCI119643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Edwards JG. In Vivo β-Adrenergic Activation of Atrial Natriuretic Factor (ANF) Reporter Expression. Mol Cell Biochem. 2006;29:119–29. doi: 10.1007/s11010-006-9225-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feldman A, Ray P, Silan C, Mercer J, Minobe W, Bristow M. Selective gene expression in failing human heart: quantification of steady-state levels of messenger RNA in endomyocardial biopsies using the polymerase chain reaction. Circulation. 1991;83:1866–72. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.83.6.1866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luchner A1, Borgeson DD, Grantham JA, et al. Relationship between left ventricular wall stress and ANP gene expression during the evolution of rapid ventricular pacing-induced heart failure in the dog. Eur J Heart Fail. 2000;2:379–86. doi: 10.1016/s1388-9842(00)00104-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morisco C, Zebrowski DC, Vatner DE, Vatner SF, Sadoshima J. Beta-adrenergic cardiac hypertrophy is mediated primarily by the beta(1)-subtype in the rat heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2001;33:561–73. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spinale FG, Holzgrefe HH, Mukherjee R, et al. LV and myocyte structure and function after early recovery from tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:H836–47. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.268.2.H836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dixon JA, Spinale FG. Large animal models of heart failure: a critical link in the translation of basic science to clinical practice. Circ Heart Fail. 2009;2:262–71. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.108.814459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lionetti V, Guiducci L, Simioniuc A, et al. Mismatch between uniform increase in cardiac glucose uptake and regional contractile dysfunction in pacing-induced heart failure. Am J Physiol. 2007;293:H2747–56. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00592.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zablocki D, Sadoshima J. Angiotensin II and oxidative stress in the failing heart. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;19:1095–109. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaludercic N, Takimoto E, Nagayama T, et al. Monoamine oxidase A-mediated enhanced catabolism of norepinephrine contributes to adverse remodeling and pump failure in hearts with pressure overload. Circ Res. 2010;106:193–202. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.198366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meyer M, Clauss M, Lepple-Wienhues A, et al. A novel vascular endothelial growth factor encoded by Orf virus, VEGF-E, mediates angiogenesis via signalling through VEGFR-2 (KDR) but not VEGFR-1 (Flt-1) receptor tyrosine kinases. EMBO J. 1999;18:363–74. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.2.363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rottbauer W, Just S, Wessels G, et al. VEGF-PLCgamma1 pathway controls cardiac contractility in the embryonic heart. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1624–34. doi: 10.1101/gad.1319405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pacak CA, Mah CS, Thattaliyath BD, et al. Recombinant adeno-associated virus serotype 9 leads to preferential cardiac transduction in vivo. Circ Res. 2006;99:e3–9. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000237661.18885.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karpanen T, Bry M, Ollila HM, Seppänen-Laakso T, et al. Overexpression of vascular endothelial growth factor-B in mouse heart alters cardiac lipid metabolism and induces myocardial hypertrophy. Circ Res. 2008;103:1018–26. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.178459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hagberg CE, Mehlem A, Falkevall A, et al. Targeting VEGF-B as a novel treatment for insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Nature. 2012;490:426–30. doi: 10.1038/nature11464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Su H, Joho S, Huang Y, et al. Adeno-associated viral vector delivers cardiac-specific and hypoxia-inducible VEGF expression in ischemic mouse hearts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:16280–305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407449101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pachori AS, Melo LG, Hart ML, et al. Hypoxia-regulated therapeutic gene as a preemptive treatment strategy against ischemia/reperfusion tissue injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:12282–307. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404616101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mallat Z, Philip I, Lebret M, Chatel D, Maclouf J, Tedgui A. Elevated levels of 8-iso-prostaglandin F2alpha in pericardial fluid of patients with heart failure: a potential role for in vivo oxidant stress in ventricular dilatation and progression to heart failure. Circulation. 1998;97:1536–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.16.1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maack C, Kartes T, Kilter H, et al. Oxygen free radical release in human failing myocardium is associated with increased activity of rac1-GTPase and represents a target for statin treatment. Circulation. 2003;108:1567–74. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000091084.46500.BB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heymes C, Bendall JK, Ratajczak P, et al. Increased myocardial NADPH oxidase activity in human heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:2164–71. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00471-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Satoh M1, Matter CM, Ogita H, et al. Inhibition of apoptosis-regulated signaling kinase-1 and prevention of congestive heart failure by estrogen. Circulation. 2007;115:3197–204. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.657981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Measurements were taken with the pacemaker off. n=10 in both groups; *P<0.05 vs day 0 (baseline) within the group; †P<0.05 vs day 14 within the group.

Measurements were taken with the pacemaker off. n=10 in HF control, AAV-GFP and AAV-CMV-VEGF-B and n=5 for the AAV-ANF-VEGF-B. No significant differences were detected.

The transgene was tested in cultured neonatal cardiomyocytes exposed to 100 M−6 isoproterenol. The experiments were performed in triplicates.

The upper panel shows representative photomicrographs from LV tissue samples for each of the experimental conditions. One CD3+ cell per picture is indicated by an arrow. Bar= 50 μm. The lower panel shows the cell quantification. n=4 per group. In each sample, T lymphocytes were counted in 20 randomly selected filed at 10x magnification.

(A). Mitochondrial superoxide dismutase (SOD2) protein expression in cultured neonatal rat cardiomyocytes exposed to VEGF-B and representative images of MitoSox fluorescence in cultured neonatal cardiomyocytes exposed to Ang II without and with short-interfering (si)RNA to knock down SOD2; n=4 per group. *p < 0.05 versus control; #p < 0.05 versus AngII + VEGF-

(B). In cultured neonatal rat cardiomyocytes, Ang II induced translocation of the sub-unit p47 to caveolin 3 (Cav3)-enriched sarcolemmal fractions (lipid rafts, especially fractions 5 to 7) separated by ultracentrifugation, indicating the activation of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate complex. This activation was prevented by VEGF-B.