Abstract

The ability of personality traits to predict important life outcomes has traditionally been questioned because of the putative small effects of personality. In this article, we compare the predictive validity of personality traits with that of socioeconomic status (SES) and cognitive ability to test the relative contribution of personality traits to predictions of three critical outcomes: mortality, divorce, and occupational attainment. Only evidence from prospective longitudinal studies was considered. In addition, an attempt was made to limit the review to studies that controlled for important background factors. Results showed that the magnitude of the effects of personality traits on mortality, divorce, and occupational attainment was indistinguishable from the effects of SES and cognitive ability on these outcomes. These results demonstrate the influence of personality traits on important life outcomes, highlight the need to more routinely incorporate measures of personality into quality of life surveys, and encourage further research about the developmental origins of personality traits and the processes by which these traits influence diverse life outcomes.

Starting in the 1980s, personality psychology began a profound renaissance and has now become an extraordinarily diverse and intellectually stimulating field (Pervin & John, 1999). However, just because a field of inquiry is vibrant does not mean it is practical or useful—one would need to show that personality traits predict important life outcomes, such as health and longevity, marital success, and educational and occupational attainment. In fact, two recent reviews have shown that different personality traits are associated with outcomes in each of these domains (Caspi, Roberts, & Shiner, 2005; Ozer & Benet-Martinez, 2006). But simply showing that personality traits are related to health, love, and attainment is not a stringent test of the utility of personality traits. These associations could be the result of “third” variables, such as socioeconomic status (SES), that account for the patterns but have not been controlled for in the studies reviewed. In addition, many of the studies reviewed were cross-sectional and therefore lacked the methodological rigor to show the predictive validity of personality traits. A more stringent test of the importance of personality traits can be found in prospective longitudinal studies that show the incremental validity of personality traits over and above other factors.

The analyses reported in this article test whether personality traits are important, practical predictors of significant life outcomes. We focus on three domains: longevity/mortality, divorce, and occupational attainment in work. Within each domain, we evaluate empirical evidence using the gold standard of prospective longitudinal studies—that is, those studies that can provide data about whether personality traits predict life outcomes above and beyond well-known factors such as SES and cognitive abilities. To guide the interpretation drawn from the results of these prospective longitudinal studies, we provide benchmark relations of SES and cognitive ability with outcomes from these three domains. The review proceeds in three sections. First, we address some misperceptions about personality traits that are, in part, responsible for the idea that personality does not predict important life outcomes. Second, we present a review of the evidence for the predictive validity of personality traits. Third, we conclude with a discussion of the implications of our findings and recommendations for future work in this area.

THE “PERSONALITY COEFFICIENT”: AN UNFORTUNATE LEGACY OF THE PERSON-SITUATION DEBATE

Before we embark on our review, it is necessary to lay to rest a myth perpetrated by the 1960s manifestation of the person–situation debate; this myth is often at the root of the perspective that personality traits do not predict outcomes well, if at all. Specifically, in his highly influential book, Walter Mischel (1968) argued that personality traits had limited utility in predicting behavior because their correlational upper limit appeared to be about .30. Subsequently, this .30 value became derided as the “personality coefficient.” Two conclusions were inferred from this argument. First, personality traits have little predictive validity. Second, if personality traits do not predict much, then other factors, such as the situation, must be responsible for the vast amounts of variance that are left unaccounted for. The idea that personality traits are the validity weaklings of the predictive panoply has been reiterated in unmitigated form to this day (e.g., Bandura, 1999; Lewis, 2001; Paul, 2004; Ross & Nisbett, 1991). In fact, this position is so widely accepted that personality psychologists often apologize for correlations in the range of .20 to .30 (e.g., Bornstein, 1999).

Should personality psychologists be apologetic for their modest validity coefficients? Apparently not, according to Meyer and his colleagues (Meyer et al., 2001), who did psychological science a service by tabling the effect sizes for a wide variety of psychological investigations and placing them side-by-side with comparable effect sizes from medicine and everyday life. These investigators made several important points. First, the modal effect size on a correlational scale for psychology as a whole is between .10 and .40, including that seen in experimental investigations (see also Hemphill, 2003). It appears that the .30 barrier applies to most phenomena in psychology and not just to those in the realm of personality psychology. Second, the very largest effects for any variables in psychology are in the .50 to .60 range, and these are quite rare (e.g., the effect of increasing age on declining speed of information processing in adults). Third, effect sizes for assessment measures and therapeutic interventions in psychology are similar to those found in medicine. It is sobering to see that the effect sizes for many medical interventions—like consuming aspirin to treat heart disease or using chemotherapy to treat breast cancer—translate into correlations of .02 or .03. Taken together, the data presented by Meyer and colleagues make clear that our standards for effect sizes need to be established in light of what is typical for psychology and for other fields concerned with human functioning.

In the decades since Mischel’s (1968) critique, researchers have also directly addressed the claim that situations have a stronger influence on behavior than they do on personality traits. Social psychological research on the effects of situations typically involves experimental manipulation of the situation, and the results are analyzed to establish whether the situational manipulation has yielded a statistically significant difference in the outcome. When the effects of situations are converted into the same metric as that used in personality research (typically the correlation coefficient, which conveys both the direction and the size of an effect), the effects of personality traits are generally as strong as the effects of situations (Funder & Ozer, 1983; Sarason, Smith, & Diener, 1975). Overall, it is the moderate position that is correct: Both the person and the situation are necessary for explaining human behavior, given that both have comparable relations with important outcomes.

As research on the relative magnitude of effects has documented, personality psychologists should not apologize for correlations between .10 and .30, given that the effect sizes found in personality psychology are no different than those found in other fields of inquiry. In addition, the importance of a predictor lies not only in the magnitude of its association with the outcome, but also in the nature of the outcome being predicted. A large association between two self-report measures of extraversion and positive affect may be theoretically interesting but may not offer much solace to the researcher searching for proof that extraversion is an important predictor for outcomes that society values. In contrast, a modest correlation between a personality trait and mortality or some other medical outcome, such as Alzheimer’s disease, would be quite important. Moreover, when attempting to predict these critical life outcomes, even relatively small effects can be important because of their pragmatic effects and because of their cumulative effects across a person’s life (Abelson, 1985; Funder, 2004; Rosenthal, 1990). In terms of practicality, the −.03 association between taking aspirin and reducing heart attacks provides an excellent example. In one study, this surprisingly small association resulted in 85 fewer heart attacks among the patients of 10,845 physicians (Rosenthal, 2000). Because of its practical significance, this type of association should not be ignored because of the small effect size. In terms of cumulative effects, a seemingly small effect that moves a person away from pursuing his or her education early in life can have monumental consequences for that person’s health and well-being later in life (Hardarson et al., 2001). In other words, psychological processes with a statistically small or moderate effect can have important effects on individuals’ lives depending on the outcomes with which they are associated and depending on whether those effects get cumulated across a person’s life.

PERSONALITY EFFECTS ON MORTALITY, DIVORCE, AND OCCUPATIONAL ATTAINMENT

Selection of Predictors, Outcomes, and Studies for This Review

To provide the most stringent test of the predictive validity of personality traits, we chose to focus on three objective outcomes: mortality, divorce, and occupational attainment. Although we could have chosen many different outcomes to examine, we selected these three because they are socially valued; they are measured in similar ways across studies; and they have been assessed as outcomes in studies of SES, cognitive ability, and personality traits. Mortality needs little justification as an outcome, as most individuals value a long life. Divorce and marital stability are important outcomes for several reasons. Divorce is a significant source of depression and distress for many individuals and can have negative consequences for children, whereas a happy marriage is one of the most important predictors of life satisfaction (Myers, 2000). Divorce is also linked to disproportionate drops in economic status, especially for women (Kuh & Maclean, 1990), and it can undermine men’s health (e.g., Lund, Holstein, & Osler, 2004). An intact marriage can also preserve cognitive function into old age for both men and women, particularly for those married to a high-ability spouse (Schaie, 1994).

Educational and occupational attainment are also highly prized (Roisman, Masten, Coatsworth, & Tellegen, 2004). Research on subjective well-being has shown that occupational attainment and its important correlate, income, are not as critical for happiness as many assume them to be (Myers, 2000). Nonetheless, educational and occupational attainment are associated with greater access to many resources that can improve the quality of life (e.g., medical care, education) and with greater “social capital” (i.e., greater access to various resources through connections with others; Bradley & Corwyn, 2002; Conger & Donnellan, 2007). The greater income resulting from high educational and occupational attainment may also enable individuals to maintain strong life satisfaction when faced with difficult life circumstances (Johnson & Krueger, 2006).

To better interpret the significance of the relations between personality traits and these outcomes, we have provided comparative information concerning the effect of SES and cognitive ability on each of these outcomes. We chose to use SES as a comparison because it is widely accepted to be one of the most important contributors to a more successful life, including better health and higher occupational attainment (e.g., Adler et al., 1994; Gallo & Mathews, 2003; Galobardes, Lynch, & Smith, 2004; Sapolsky, 2005). In addition, we chose cognitive ability as a comparison variable because, like SES, it is a widely accepted predictor of longevity and occupational success (Deary, Batty, & Gottfredson, 2005; Schmidt & Hunter, 1998). In this article, we compare the effect sizes of personality traits with these two predictors in order to understand the relative contribution of personality to a long, stable, and successful life. We also required that the studies in this review make some attempt to control for background variables. For example, in the case of mortality, we looked for prospective longitudinal studies that controlled for previous medical conditions, gender, age, and other relevant variables.

We are not assuming that personality traits are direct causes of the outcomes under study. Rather, we were exclusively interested in whether personality traits predict mortality, divorce, and occupational attainment and in their modal effect sizes. If found to be robust, these patterns of statistical association then invite the question of why and how personality traits might cause these outcomes, and we have provided several examples in each section of potential mechanisms and causal steps involved in the process.

The Measurement of Effect Sizes in Prospective Longitudinal Studies

Before turning to the specific findings for personality, SES, and cognitive ability, we must first address the measurement of effect sizes in the studies reviewed here. Most of the studies that we reviewed used some form of regression analysis for either continuous or categorical outcomes. In studies with continuous outcomes, findings were typically reported as standardized regression weights (beta coefficients). In studies of categorical outcomes, the most common effect size indicators are odds ratios, relative risk ratios, or hazard ratios. Because many psychologists may be less familiar with these ratio statistics, a brief discussion of them is in order. In the context of individual differences, ratio statistics quantify the likelihood of an event (e.g., divorce, mortality) for a higher scoring group versus the likelihood of the same event for a lower scoring group (e.g., persons high in negative affect versus those low in negative affect). An odds ratio is the ratio of the odds of the event for one group over the odds of the same event for the second group. The risk ratio compares the probabilities of the event occurring for the two groups. The hazard ratio assesses the probability of an event occurring for a group over a specific window of time. For these statistics, a value of 1.0 equals no difference in odds or probabilities. Values above 1.0 indicate increased likelihood (odds or probabilities) for the experimental (or numerator) group, with the reverse being true for values below 1.0 (down to a lower limit of zero). Because of this asymmetry, the log of these statistics is often taken.

The primary advantage of ratio statistics in general, and the risk ratio in particular, is their ease of interpretation in applied settings. It is easier to understand that death is three times as likely to occur for one group than for another than it is to make sense out of a point-biserial correlation. However, there are also some disadvantages that should be understood. First, ratio statistics can make effects that are actually very small in absolute magnitude appear to be large when in fact they are very rare events. For example, although it is technically correct that one is three times as likely (risk ratio = 3.0) to win the lottery when buying three tickets instead of one ticket, the improved chances of winning are trivial in an absolute sense.

Second, there is no accepted practice for how to divide continuous predictor variables when computing odds, risk, and hazard ratios. Some predictors are naturally dichotomous (e.g., gender), but many are continuous (e.g., cognitive ability, SES). Researchers often divide continuous variables into some arbitrary set of categories in order to use the odds, rate, or hazard metrics. For example, instead of reporting an association between SES and mortality using a point-biserial correlation, a researcher may use proportional hazards models using some arbitrary categorization of SES, such as quartile estimates (e.g., lowest versus highest quartiles). This permits the researcher to draw conclusions such as “individuals from the highest category of SES are four times as likely to live longer than are groups lowest in SES.” Although more intuitively appealing, the odds statements derived from categorizing continuous variables makes it difficult to deduce the true effect size of a relation, especially across studies. Researchers with very large samples may have the luxury of carving a continuous variable into very fine-grained categories (e.g., 10 categories of SES), which may lead to seemingly huge hazard ratios. In contrast, researchers with smaller samples may only dichotomize or trichotomize the same variables, thus resulting in smaller hazard ratios and what appear to be smaller effects for identical predictors. Finally, many researchers may not categorize their continuous variables at all, which can result in hazard ratios very close to 1.0 that are nonetheless still statistically significant. These procedures for analyzing odds, rate, and hazard ratios produce a haphazard array of results from which it is almost impossible to discern a meaningful average effect size.1

One of the primary tasks of this review is to transform the results from different studies into a common metric so that a fair comparison could be made across the predictors and outcomes. For this purpose, we chose the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient. We used a variety of techniques to arrive at an accurate estimate of the effect size from each study. When transforming relative risk ratios into the correlation metric, we used several methods to arrive at the most appropriate estimate of the effect size. For example, the correlation coefficient can be estimated from reported significance levels (p values) and from test statistics such as the t test or chi-square, as well as from other effect size indicators such as d scores (Rosenthal, 1991). Also, the correlation coefficient can be estimated directly from relative risk ratios and hazard ratios using the generic inverse variance approach (The Cochrane Collaboration, 2005). In this procedure, the relative risk ratio and confidence intervals (CIs) are first transformed into z scores, and the z scores are then transformed into the correlation metric.

For most studies, the effect size correlation was estimated from information on relative risk ratios and p values. For the latter, we used the requivalent effect size indicator (Rosenthal & Rubin, 2003), which is computed from the sample size and p value associated with specific effects. All of these techniques transform the effect size information to a common correlational metric, making the results of the studies comparable across different analytical methods. After compiling effect sizes, meta-analytic techniques were used to estimate population effect sizes in both the risk ratio and correlation metric (Hedges & Olkin, 1985). Specifically, a random-effects model with no moderators was used to estimate population effect sizes for both the rate ratio and correlation metrics.2 When appropriate, we first averaged multiple nonindependent effects from studies that reported more than one relevant effect size.

The Predictive Validity of Personality Traits for Mortality

Before considering the role of personality traits in health and longevity, we reviewed a selection of studies linking SES and cognitive ability to these same outcomes. This information provides a point of reference to understand the relative contribution of personality. Table 1 presents the findings from 33 studies examining the prospective relations of low SES and low cognitive ability with mortality.3 SES was measured using measures or composites of typical SES variables including income, education, and occupational status. Total IQ scores were commonly used in analyses of cognitive ability. Most studies demonstrated that being born into a low-SES household or achieving low SES in adulthood resulted in a higher risk of mortality (e.g., Deary & Der, 2005; Hart et al., 2003; Osler et al., 2002; Steenland, Henley, & Thun, 2002). The relative risk ratios and hazard ratios ranged from a low of 0.57 to a high of 1.30 and averaged 1.24 (CIs = 1.19 and 1.29). When translated into the correlation metric, the effect sizes for low SES ranged from −.02 to .08 and averaged .02 (CIs = .017 and .026).

TABLE 1.

SES and IQ Effects on Mortality/Longevity

| Study | N | Outcome | Years | Controls | Predictors | Outcome | Est. r |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abas et al., 2002 | 2,584 members of the Medical Research Council Elderly Hypertension Trial |

All-cause mortality |

11 years | Low scores on the New Adult Reading Test (IQ) Low scores on Raven’s Progressive Matrices (IQ) |

HR = 0.94 (0.86, 1.02) p = .16 HR = 0.97 (0.88, 1.06) p = .53 |

rhr = .03a re = .03a rhr = .01a re = .01a |

|

| Bassuk, Berkman, & Amick, 2002 | 9,025 men from Boston |

All-cause mortality |

9 years | Age, smoking, BMI, alcohol consumption, activity level, social ties, having a regular health care provider, number of chronic conditions, depressive symptoms, cognitive function, physical function, health status |

Low adult education Low adult income Low adult occupational prestige |

HR = 1.32 (0.95, 1.83) HR = 0.94 (0.65, 1.34) HR = 1.09 (0.86, 1.39) |

rhr = .02 rhr = .00 rhr = .01 |

| 6,518 women from Boston |

All-cause mortality |

9 years | Age, smoking, BMI, alcohol consumption, activity level, social ties, having a regular health care provider, number of chronic conditions, depressive symptoms, cognitive function, physical function, health status |

Low adult education Low adult income Low adult occupational prestige |

HR = 0.74 (0.53, 1.04) p < .10 HR = 0.80 (0.52, 1.23) HR = 0.74 (0.57, 0.98) p < .05 |

rhr = −.02 re = −.02 rhr = −.01 rhr = −.03 re = −.02 |

|

| 12,235 men from Iowa |

All-cause mortality |

9 years | Age, smoking, BMI, alcohol consumption, activity level, social ties, having a regular health care provider, number of chronic conditions, depressive symptoms, cognitive function, physical function, health status |

Low adult education Low adult income Low adult occupational prestige |

HR = .77 (.56, 1.07) HR = 1.18 (0.89, 1.58) HR = 0.93 (0.69, 1.27) |

rhr = −.01 rhr = .01 rhr = .00 |

|

| 9,248 women from Iowa |

All-cause mortality |

9 years | Age, smoking, BMI, alcohol consumption, activity level, social ties, having a regular health care provider, number of chronic conditions, depressive symptoms, cognitive function, physical function, health status |

Low adult education Low adult income Low adult occupational prestige |

HR = 0.87 (0.61, 1.23) HR = 1.03 (.76, 1.41) HR = .57 (.36, .92) p < .05 |

rhr = −.01 rhr = .00 rhr = −.02 re = −.02 |

|

| 10,081 men from Connecticut |

All-cause mortality |

9 years | Age, race, smoking, BMI, alcohol consumption, activity level, social ties, having a regular health care provider, number of chronic conditions, depressive symptoms, cognitive function, physical function, health status |

Low adult education Low adult income Low adult occupational prestige |

HR = 1.30 (0.96, 1.75) p < .10 HR = 1.62 (1.17, 2.23) p < .005 HR = 1.20 (0.94, 1.53) |

rhr = .02 re = .02 rhr = .03 re = .03 rhr = .01 |

|

| 7,331 women from Connecticut |

All-cause mortality |

9 years | Age, race, smoking, BMI, alcohol consumption, activity level, social ties, having a regular health care provider, number of chronic conditions, depressive symptoms, cognitive function, physical function, health status |

Low adult education Low adult income Low adult occupational prestige |

HR = 0.96 (0.64, 1.44) HR = 1.90 (1.09, 3.32) p < .05 HR = 1.15 (0.83, 1.59) |

rhr = .00 rhr = .03 re = .02 rhr = .01 |

|

| 11,977 men from North Carolina |

All-cause mortality |

9 years | age, race, smoking, degree of urbanization, BMI, alcohol consumption, social ties, having a regular health care provider, number of chronic conditions, depressive symptoms, cognitive function, physical function, health status |

Low adult education Low adult income Low adult occupational prestige |

HR = 1.18 (0.84, 1.64) HR = 1.42 (1.01, 1.84) p < .01 HR = 1.01 (.78, 1.32) |

rhr = .01 rhr = .02 re = .02 rhr = .00 |

|

| 8,836 women from North Carolina |

All-cause mortality |

9 years | Age, race, smoking, BMI, alcohol consumption, social ties, having a regular health care provider, number of chronic conditions, depressive symptoms, cognitive function, physical function, health status |

Low adult education Low adult income Low adult occupational prestige |

HR = 1.04 (0.84, 1.30) HR = 1.52 (1.11, 2.08) p < .01 HR = 1.21 (0.97, 1.51) p < .10 |

rhr = .00 rhr = .03 re = .03 rhr = .02 re = .02 |

|

| Beebe-Dimmer et al, 2004 | 3,087 women from the Alameda County Study |

All-cause mortality |

30 years | Age, income, education, occupation, smoking, BMI, physical activity |

Low childhood SES Low adult education Manual occupation Low adult income |

HR = 1.12 (0.99, 1.27) HR = 1.17 (0.99, 1.39) HR = 1.06 (0.87, 1.30) HR = 1.35 (1.14, 1.60) |

rhr = .03 rhr = .03 rhr = .01 rhr = .06 |

| Bosworth & Schaie, 1999 | 1,218 members of the Seattle Longitudinal Study |

All-cause mortality |

7 years | Sex, age, education | Low verbal IQ Low math IQ Low spatial IQ |

F(1, 1,174) = 17.58, p < .001 F(1, 1,198) = 3.75, p < .05 F(1, 1,119) = 3.72, p <.05 |

rF = .12 re = .10 rF = .06 re = .06 rF = .06 re = .06 |

| Bucher & Ragland, 1995 | 3,154 middle-aged men from the Western Collaborative Group Study |

All-cause mortality |

22 years | Systolic blood pressure, cholesterol, smoking, height |

Low adult SES | RR = 1.45 (1.17, 1.81) | rrr = .06 |

| Clausen, Davey-Smith, & Thelle, 2003 | 128,723 Oslo natives |

All-cause mortality |

30 years | Age, adult income | Low index of inequality | RR men = 2.48 (1.94, 3.16) RR women = 1.47 (1.06, 2.04) |

rrr = .03 rrr = .01 |

| Curtis, Southall, Congdon, & Dodgeon, 2004 | 23,311 men and 35,295 women of the National Statistics Longitudinal Study |

All-cause mortality |

10 years | Age, sex, marital status, employment status |

Low adult social class | OR men = 1.26 (1.10, 1.46) OR women = .90 (.77, 1.06) |

ror = .02 ror = −.01 |

| Davey Smith, Hart, Blane, & Hole, 1998 | 5,766 men aged 35– 64 in 1970 |

All-cause mortality |

25 years | Age, adult SES, deprivation, car, risk factors |

Low father’s social class | HR = 1.19 (1.04, 1.37) p = .042 |

rhr = .03 re = .03 |

| Deary & Der, 2005 | 898 members of the Twenty-07 Study |

All-cause mortality |

24 years | Sex, smoking, social class, years of education |

Low IQ | HR = 1.38 (1.15, 1.67) p = .0006 |

rhr = .15 re = .11 |

| Sex, smoking, years of education, IQ |

Low social class | HR = 1.13 (1.01, 1.26) p = .027 |

rhr = .07 re = .07 |

||||

| Sex, smoking, social class, IQ | Low education | HR = 1.06 (0.97, 1.12) p = .20 |

rhr = .04 re = .04 |

||||

| Doornbos & Kromhout, 1990 | 78,505 Dutch Nationals |

All-cause mortality |

32 years | Height, health | High education level | RR = 0.69a (0.57, 0.81) p < .0001 |

rhr = −.01a re = −.01a |

| Fiscella & Franks, 2000 | 13,332 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey participants |

All-cause mortality |

12 years | Age, sex, morbidity, income inequality, depression, self-rated health |

High income | HR = 0.80a (0.77, 0.83) | rhr = −.10a |

| Ganguli et al, 2002 | 1,064 members of the Monongahela Valley Independent Elders Survey |

All-cause mortality |

10 years | Age, sex, education, functional disability, self-rated health, depression, Number of drugs taken, depression × self-rated health interaction |

Low education Low cognitive functioning (MMSE score) |

RR = .99 p = .94 RR = 1.55, p = .002 |

re = .002 re = .09 |

| Hardarson et al., 2001 | 9,773 women and 9,139 men from the Reykjavik Study |

All-cause mortality |

3–30 years |

Height, weight, cholesterol, triglycerides, systolic blood pressure, blood sugar, smoking |

High education High education |

Men’s HR = 0.77 (0.66, 0.88) Women’s HR = 1.29 (.56, 1.35) |

rhr = −.05 rhr = .01 |

| Hart et al, 2003 | 922 members of the Midspan Study who also participated in the Scottish Mental Survey of 1932 |

All-cause mortality |

25 years | Sex, social class, deprivation Sex, IQ, deprivation |

Low IQ Low social class |

RR = 1.26 (0.94, 1.70) p = .038 RR = 1.22 (0.88, 1.68) p = .35 |

rhr = .05 re = .07 rhr = .04 re = .03 |

| Heslop, Smith, Macleod, & Hart, 2001 | 958 Women from Western Scotland |

All-cause mortality |

25 years | Age, blood pressure, cholesterol, BMI, FEV, smoking, exercise, alcohol |

Low lifetime social class | HR = 1.48 (1.04, 2.09) p = .037 |

rhr = .07 re = .07 |

| Hosegood & Campbell, 2003 | 1,888 women from rural Bangladesh |

All-cause mortality |

19 years | Age | No education | p = .005 | re = .06 |

| Khang & Kim, 2005 | 5,437 South Koreans aged 30 years and older |

All-cause mortality |

5 years | Age, gender, urbanization, number of family members, biological risk factors |

Low annual household income |

RR = 2.24 (1.40, 3.60) | rrr = .05 |

| Korten et al., 1999 | 897 subjects aged 70 years and older |

All-cause mortality |

3.5 years | Age, sex, general health, ADLs, illness, blood pressure, Symbol- Letter Modalities Test |

Low IQ | HR = 2.42 (1.27, 4.62) |

rhr = .09 |

| Kuh, Hardy, Langenberg, Richards, & Wadsworth, 2002 | 2,547 women and 2,812 men from the Medical Research Council national survey |

All-cause mortality |

46 years | Sex, adult SES, education | Low father’s social class | HR = 1.90 (1.30, 2.70) p < .001 |

rhr = .06 re = .05 |

| Kuh, Richards, Hardy, Butterworth, & Wadsworth, 2004 | 2,547 women and 2,812 men from the Medical Res. |

All-cause mortality |

46 years | Sex, adult SES, education | Low IQ | HR men = 1.80 (1.10, 2.70) p < .013 |

rhr = .05 re = .05 |

| Council national survey |

Low IQ | HR women = 0.90 (0.52, 1.60) p = .70 |

rhr = −.01 re = −.01 |

||||

| Lantz et al, 1998 | 3,617 subjects aged 25 years and older |

All-cause mortality |

7.5 years | Age, sex, race, residence | Low education Low income |

HR = 1.08 (0.76, 1.54) HR = 3.22 (2.01, 5.16) |

rhr = .01 rhr = .08 |

| Lynch et al, 1994 | 2,636 Finnish men | All-cause mortality |

8 years | Age | Low childhood SES | RR = 2.39 (1.28, 4.44) | rrr = .05 |

| Maier & Smith, 1999 | 513 members of the Berlin Aging Study aged 70 years and older |

All-cause mortality |

4.5 years | Age, SES, health | Low perceptual speed Low reasoning Low memory Low knowledge Low fluency |

RR = 1.53 (1.29, 1.81) RR = 1.37 (1.19, 1.71) RR = 1.39 (1.19, 1.63) RR = 1.33 (1.15, 1.54) RR = 1.50 (1.27, 1.78) |

rrr = .22 rrr = .15 rrr = .18 rrr = .17 rrr = .21 |

| Martin & Kubzansky, 2005 | 659 gifted children from Terman Life Cycle Study |

All-cause mortality |

48 years | Father’s occupation, poor health in childhood, Sex |

Less high IQb Father’s occupation |

HR = 0.73 (0.59, 0.90) HR = 0.99 (0.90, 1.08) |

rhr = .11 rhr = .01 |

| Osler et al, 2003 | 7,308 members of Project Metropolit in Copenhagen |

All-cause mortality |

49 years | IQ, birth weight SES, birth weight |

Working class status Low Harnquist IQ test |

HR = 1.30 (1.08,1.57) HR = 1.53 (1.19, 1.97) |

rhr = .03 rhr = .04 |

| Osler et al, 2002 | 25,728 citizens of Copenhagen (12,715 men & 13,013 women) |

All-cause mortality |

24–34 years |

Smoking status, activity level, BMI, alcohol consumption, education, household structure, Percent of households with children |

High household income | Men’s HR = 0.64a (0.57, 0.73) p < .01 Women’s HR = 0.68a (0.65, 0.89) p < .01 |

rhr = −.06a re = −.02a rhr = −.04a re = −.02a |

| Pudaric, Sundquist, & Johansson, 2003 | 8,959 members of the Swedish Survey of Living Conditions |

All-cause mortality |

7–12 years |

Age, health status | Low education | RR = 1.22 (1.07, 1.38) | rhr = .03 |

| Shipley, Der, Taylor, & Deary, 2006 | 6,424 members of the UK Health and Lifestyle Survey |

All-cause mortality |

19 years | Age, sex, social class, education, health behaviors, FEV, blood pressure, BMI |

High verbal memory High visual spatial ability |

HR = 0.95 (0.92, 0.99) p < .0052 HR = 0.99 (0.96, 1.03) p = .66 |

rhr = −.03 re = −.03 rhr = −.01 re = .00 |

| Steenland et al., 2002 | 550,888 men from the CPS-I cohort |

All-cause mortality |

26 years | Age, smoking, BMI, diet, alcohol, hypertension, menopausal status (women) |

Low education level | Men’s RR = 1.14 (1.12, 1.16) |

rrr = .02 |

| 553,959 women from the CPS-I cohort |

Women’s RR = 1.24 (1.21, 1.28) |

rrr = .02 | |||||

| 625,663 men from the CPS-II cohort |

All-cause mortality |

16 years | Age, smoking, BMI, diet, alcohol, hypertension, menopausal status (women) |

Low education level | Men’s RR = 1.28 (1.25, 1.31) |

rrr = .03 | |

| 767,472 women from the CPS-II cohort |

Women’s RR = 1.18 (1.15, 1.22) |

rrr = .01 | |||||

| St. John et al., 2002 | 8,099 Seniors from the Canadian Study of Health and Aging |

Mortality | 5 years | Age, sex, education, marital status, functional status, self-rated health |

High MMSE scores | OR = 0.95 (0.93, 0.97) | ror = −.05a |

| Tenconi, Devoti, Comelli, & RIFLE Research Group, 2000 | 12,361 Italian men from the RIFLE pooling project |

All-cause mortality |

7 years | Age, systolic blood pressure, cholesterol, smoking |

Low adult education level Low adult occupational level |

RR = 0.76 (0.56, 1.01) p = .122 RR = 1.30 (1.04, 1.63) p = .022 |

rrr = −.02 re = −.01 rrr = .02 re = .02 |

| Vagero & Leon, 1994 | 404,450 Swedish men born in 1946– 1955 |

Mortality | 36 years | Adulthood social class | Low childhood social class |

OR = 1.52 (1.32, 1.76) | ror = .01 |

| Whalley & Deary, 2001 | 722 Members of the Scottish mental survey of 1932 |

Life expectancy |

76 years | Father’s SES, overcrowding | High Moray House test scores (IQ) |

Partial r = .19 | r = .19 |

Note. Confidence intervals are given in parentheses. SES = socioeconomic status; HR = hazard ratio; RR = relative risk ratio; OR = odds ratio; rrr = Correlation estimated from the rate ratio; rhr = correlation estimated from the hazard ratio; ror = correlation estimated from the odds ratio; rF = correlation estimated from F test; re = requivalent—correlation estimated from the reported p value and sample size; BMI = body mass index; FEV = forced expiratory volume; ADLs = activities of daily living; MMSE = Mini Mental State Examination; CPS = Cancer Prevention Study; RIFLE = risk factors and life expectancy.

The sign of the ratios and correlations based on high SES and high IQ were reversed before these effect sizes were aggregated with remaining effect sizes.

IQ scores are referred to as “less high” because the lowest IQ score in the sample was 135.

Through the use of the relative risk metric, we determined that the effect of low IQ on mortality was similar to that of SES, ranging from a modest 0.74 to 2.42 and averaging 1.19 (CIs = 1.10 and 1.30). When translated into the correlation metric, however, the effect of low IQ on mortality was equivalent to a correlation of .06 (CIs = .03 and .09), which was three times larger than the effect of SES on mortality. The discrepancy between the relative risk and correlation metrics most likely resulted because some studies reported the relative risks in terms of continuous measures of IQ, which resulted in smaller relative risk ratios (e.g., St. John, Montgomery, Kristjansson, & McDowell, 2002). Merging relative risk ratios from these studies with those that carve the continuous variables into subgroups appears to underestimate the effect of IQ on mortality, at least in terms of the relative risk metric. The most telling comparison of IQ and SES comes from the five studies that include both variables in the prediction of mortality. Consistent with the aggregate results, IQ was a stronger predictor of mortality in each case (i.e., Deary & Der, 2005; Ganguli, Dodge, & Mulsant, 2002; Hart et al., 2003; Osler et al., 2002; Wilson, Bienia, Mendes de Leon, Evans, & Bennet, 2003).

Table 2 lists 34 studies that link personality traits to mortality/longevity.4 In most of these studies, multiple factors such as SES, cognitive ability, gender, and disease severity were controlled for. We organized our review roughly around the Big Five taxonomy of personality traits (e.g., Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Neuroticism, Agreeableness, and Openness to Experience; Goldberg, 1993b). For example, research drawn from the Terman Longitudinal Study showed that children who were more conscientious tended to live longer (Friedman et al., 1993). This effect held even after controlling for gender and parental divorce, two known contributors to shorter lifespans. Moreover, a number of other factors, such as SES and childhood health difficulties, were unrelated to longevity in this study. The protective effect of Conscientiousness has now been replicated across several studies and more heterogeneous samples. Conscientiousness was found to be a rather strong protective factor in an elderly sample participating in a Medicare training program (Weiss & Costa, 2005), even when controlling for education level, cardiovascular disease, and smoking, among other factors. Similarly, Conscientiousness predicted decreased rates of mortality in a sample of individuals suffering from chronic renal insufficiency, even after controlling for age, diabetic status, and hemoglobin count (Christensen et al., 2002).

TABLE 2.

Personality Traits and Mortality

| Study | N | Outcome | Length of study | Controls | Predictors | Outcome | Est. ra |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allison et al., 2003 | 101 survivors of head and neck cancer |

Mortality | 1 year | Age, disease stage, cohabitation status |

High Optimism | OR = 1.12 (1.01, 1.24) | ror = −.22 |

| Almada et al., 1991 | 1,871 members of the Western Electric Study |

All-cause mortality | 25 years | Age, blood pressure, smoking, cholesterol, alcohol consumption |

High Neuroticism High Cynicism |

RR = 1.20 (1.00, 1.40) RR = 1.4 (1.2, 1.7) |

rrr = .05 rrr = .09 |

| Barefoot, Dahlstrom, & Williams, 1983 | 255 medical students | All-cause mortality | 25 years | High Hostility | p = .005 | re = .18 | |

| Barefoot, Dodge, Peterson, Dahlstrom, & Williams, 1989 | 128 law Students | 29 years | Age | High Hostility | p = .012 | re = .22 | |

| Barefoot, Larsen, von der Lieth, & Schroll, 1995 | 730 residents of Glostrup born in 1914 |

All-cause mortality | 27 years | Age, sex, blood pressure, smoking, triglycerid, FEV |

High Hostility | RR = 1.36 (1.06, 1.75) | rrr = .09 |

| Barefoot et al., 1998 | 100 Older men and women | All-cause mortality | 14 years | Sex, age | High Trust | RR = 0.46 (0.24, 0.91) p < .03 |

rrr = −.23 re = −.22 |

| Barefoot et al., 1987 | 500 members of the second Duke longitudinal study |

All-cause mortality | 15 years | Age, sex, cholesterol levels, smoking, physician ratings of health |

Suspiciousness | p = .02 | re = .10 |

| Boyle et al., 2005 | 1,328 Duke University Medical Center patients |

All-cause mortality | 15 years | Sex, age, tobacco consumption, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, number of coronary arteries narrowed, left ventricular ejection fraction, artery bypass surgery |

High Hostility | HR = 1.25 (1.06, 1.47) p < .007 |

rhr = .07 re = .07 |

| Boyle et al., 2004 | 936 Duke University Medical Center patients |

All-cause mortality | 15 years | Sex, age, tobacco consumption, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, number of coronary arteries narrowed, left ventricular ejection fraction, artery bypass surgery |

High Hostility | HR = 1.28 (1.06, 1.55) p <. 02 |

rhr = .08 re = .08 |

| Christensen et al., 2002 | 174 chronic renal insufficiency patients |

Mortality | 4 years | Age, diabetic status, hemoglobin |

High Conscientiousness | HR = 0.94, B = −.066 (.03) p < .05 |

rB = −.17 re = −.15 |

| High Neuroticism | HR = 1.05, B = .047 (.023) p <. 05 |

rhr = .15 re = .15 |

|||||

| Danner et al, 2001 | 180 nuns | Longevity | 63 years | Age, education, linguistic ability |

High Positive Emotion (sentences) High Positive Emotion (words) |

HR = 2.50 (1.20, 5.30) p < .01 HR = 3.20 (1.50, 6.80) p < .01 |

rhr = .18 re = .19 rhr = .22 re = .19 |

| Different Positive Emotions | HR = 4.30 (1.70, 10.40) p < .01 |

rhr = .24 re = .19 |

|||||

| Denollet et al, 1996 | 303 CHD patients | Mortality | 8 years | CHD, age, social alienation, depression, use of benzodiazepines |

Type D personalityb | HR = 4.10 (1.90, 8.80) p = .0004 |

rhr = .21 re = .20 |

| Everson et al., 1997 | 2,125 men from the Kuopio Eschemic Heart Disease Risk Factor Study |

All-cause mortality | 9 years | Age, SES | Cynical distrust | HR = 1.97 (1.26, 3.09) | rhr = .06 |

| Friedman et al., 1993 | 1,178 members of the Terman Lifecycle Study |

Longevity | 71 years | Sex, IQ | High Conscientiousness | HR = .33, B = −1.11 (0.37) p < .01 |

rhr = .09 re = .08 |

| High Cheerfulnessc | HR = 1.21, B = .19 (.07) p < .05 |

rhr = −.08 re = −.06 |

|||||

| Giltay, Geleijnse, Zitman, Hoekstra, & Schouten, 2004 | 397 men and 418 women of the Arnhem Elderly Study |

All-cause mortality | 9 years | Age, smoking, alcohol, education, activity level, SES, and marital status |

Dispositional optimism | Men’s HR = 0.58 (0.37, 0.91) p = .01 |

rhr = −.12 re = −.13 |

| Women’s HR = 0.80 (0.51–1.25) p = .39 |

rhr = −.05 re = −.04 |

||||||

| Grossarth-Maticek, Bastianns, & Kanazir, 1985 | 1,335 inhabitants of Crvenka, Yugoslavia |

Mortality | 10 years | Age | High Rationalityd | p < .001 | re = .09 |

| Hearn, Murray, & Luepker, 1989 | 1,313 University of Minnesota students |

All-cause mortality | 33 years | Age | High Hostility | p = .72 | re = .01 |

| Hirokawa, Nagata, Takatsuka, & Shimizu, 2004 | 12,417 males and 14,133 females of the Takayama Study |

7 years | Age, smoking, marital status, BMI, exercise, alcohol, education, and number of children |

High Rationalityd | Men’s HR = 0.96 (0.83, 1.09) Women’s HR = 0.82, (0.70, 0.96) p < .05 |

rhr = −.01 rhr = −.02 re = −.02 |

|

| Hollis, Connett, Stevens, & Greenlick, 1990 | 12,866 men from the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial |

All-cause mortality | 6 years | Study group assignment, age, cigarettes, blood pressure, cholesterol |

High Type A personality | RR = 0.94 (0.89, 0.99) p < .01 |

rhr = −.02 re = −.02 |

| Iribarren et al., 2005 | 5,115 members of the CARDIA study |

Non-AIDS, non- homicide-related mortality |

16 years | Age, sex, race | High Hostility | RR = 2.02 (1.07, 3.81) | rrr = .03 |

| Kaplan et al, 1994 | 2,464 men from the Kuopio Eschemic Heart Disease Risk Factor Study |

All-cause mortality | 6 years | Age, income | Shyness | HR = 1.01 (0.63, 1.62) | rhr = .00 |

| Korten et al., 1999 | 897 subjects aged 70 years and older |

Mortality | 4 years | Age, sex, general health, ADLs, illness, blood pressure, Symbol-Letter Modalities Test, MMSE |

High Neuroticism | HR = 0.53 (0.31, 0.90) | rhr = −.08 |

| Kuskenvuo et al., 1988 | 3,750 Finnish male twins | All-cause mortality | 3 years | Age | High Hostility | RR = 2.98 (1.31, 6.77) | rrr = .04 |

| Maruta, Colligan, Malinchoc, & Offard, 2000 | 839 patients from the Mayo Clinic |

All-cause mortality | 29 years | Sex, age, expected survival | Pessimism | HR = 1.20 (1.04, 1.38) p = .01 |

rhr = .09 re = .09 |

| Maruta et al, 1993 | 620 from the Mayo Clinic | All-cause mortality | 20 years | Age, sex, hypertension, weight |

High Hostility | p = .069 | re = .07 |

| McCarron, Gunnell, Harrison, Okasha, & Davey-Smith, 2003 | 8,385 former male students | All-cause mortality | 41 years 25 years | Smoking, father’s SES, BMI, maternal and paternal vital status |

Mental instability | RR = 2.05 (1.36–3.09) p < .01 |

rrr = .04 re = .03 |

| McCranie, Watkins, Brandsma, & Sisson, 1986 | 478 physicians | All-cause mortality | 25 years | High Hostility | p = .789 | re = −.01 | |

| Murberg, Bru, & Aarsland, 2001 | 119 heart failure patients | Mortality | 2 years | Age, sex, disease severity | Neuroticism | HR = 1.140 (1.027, 1.265) p = .01 |

rhr = .23 re = .24 |

| Osler et al, 2003 | 7,308 members of Project Metropolit in Copenhagen, Denmark |

All-cause mortality | 49 years | IQ, birth weight, SES | Creativity | HR = 1.17 (0.89, 1.54) | rhr = .01 |

| C. Peterson, Seligman, Yurko, Martin, & Friedman, 1998 | 1,179 members of the Terman Lifecycle Study |

Mortality | 51 Years | Global pessimism | OR = 1.26, p < .01 | re = .08 | |

| Schulz et al., 1996 | 238 cancer patients | Cancer mortality | 8 months | Site of cancer, physical symptoms, age |

Pessimism | OR = 1.07, B = .07 (.05) |

rB = .08 |

| Pessimism × Age interaction |

OR = 0.88, B = −.12 (.06), p < .05 |

rB = −11 re = .13 |

|||||

| Surtees, Wainwright, Luben, Day, & Khaw, 2005 | 20,550 members of the EPIC-Norfolk study (8,950 men and 11,600 women) |

Mortality | 6 years | Age, disease, cigarette smoking history |

Hostility | Men’s RR = 1.06 (0.99, 1.14) Women’s RR = 1.00 (.91, 1.09) |

rrr = .02 rrr = .00 |

| Surtees, Wainwright, Luben, Khaw, & Day, 2003 | 18,248 members of the EPIC-Norfolk study |

Mortality | 6 years | Age, disease, social class, cigarette smoking history |

Strong sense of coherence | RR = 0.76 (0.65, 0.87) p < .0001 (taken from abstract) |

rhr = −.03 re = −.03 |

| Weiss & Costa, 2005e | 1,076 members of the Medicare Primary and Consumer-Directed Care Demonstration |

All-cause mortality | 5 years | Gender, age, education, diabetic status, cardiovascular disease, functional limitations, self- rated health, cigarette smoking, depression, Neuroticism, Agreeableness |

Conscientiousness | HR = 0.51 (0.31, 0.85) p < .05 |

rhr = −.08 re = −.06 |

| Gender, age, education diabetic status, cardiovascular disease, functional limitations, self- rated health, cigarette smoking, depression, Conscientiousness, Agreeableness |

Neuroticism | HR = 0.99 (0.97, 1.00) p < .05 |

rhr = −.04 re = −.06 |

||||

| Gender, age, education, diabetic status, cardiovascular disease, functional limitations, self- rated health, cigarette smoking, depression, Neuroticism, Conscientiousness |

Agreeableness | HR = 0.99 (0.98, 1.00) | rhr = −.06 | ||||

| Wilson et al., 2003 | 851 members of the Religious Orders Study |

All-cause mortality | 5 years | Age, sex, education, health | Trait anxiety | RR = 1.04 (0.99, 1.09) p = .01 (unadjusted) |

rrr = .05 re = .09 |

| Trait anger | RR = 1.03 (0.95, 1.12) p = .64 (unadjusted) |

rrr= .02 re = .02 |

|||||

| Wilson et al., 2005 | 6,158 members (aged 65 years and older) of the Chicago Health and Aging Project |

All-cause mortality | 6 years | Age, sex, race, education | Neuroticism Extraversion |

RR = 1.016 (1.010, 1.020) RR = 0.984 (0.978, 0.991) |

rrr= .07 rrr = −.05 |

| Wilson et al., 2004 | 883 members of the Religious Orders Study |

All-cause mortality | 5 years | Age, gender, education, remaining personality traits |

Neuroticism | RR = 1.04 (1.02, 1.08) p < .02 (unadjusted) |

rrr= .12 re = .09 |

| Extraversion | RR = 0.96 (0.94, 0.99) p < .001 (unadjusted) |

rrr= −.08 re = −.11 |

|||||

| Openness | RR = 1.005 (0.970, 1.040) p = .014 |

rrr= .01 re = .08 |

|||||

| Agreeableness | RR = 0.964 (0.930, 1.000) p = .011 |

rrr= −.06 re = −.09 |

|||||

| Conscientiousness | RR = 0.968 (0.94, 0.99) p < .001 |

rrr= −.07 re = −.11 |

Note. Confidence intervals are given in parentheses. HR = hazard ratio; RR = relative risk ratio; OR = odds ratio; rrr = correlation estimated from the rate ratio; rhr = correlation estimated from the hazard ratio; ror = correlation estimated from the odds ratio; rB = correlation estimated from a beta weight and standard error; re = requivalent (correlation estimated from the reported p value and sample size); FEV = forced expiratory volume; CHD = coronary heart disease; SES =socioeconomic status; BMI =body-ass index; ADLs =activities of daily living; MMSE =Mini Mental State Examination.

The direction of the correlation was derived by choosing a positive pole for each dimension (high Extraversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Neuroticism, and Openness) and assuming that each dimension, with the exception of Neuroticism, would be negatively related to mortality in its positive manifestation.

Type D personality was categorized as a Neuroticism measure as it correlates more consistently with high Neuroticism (De Fruyt & Denollet, 2002), though it should be noted that it has strong correlations with low Extraversion, low Agreeableness, and low Conscientiousness.

On the basis of the correlations presented in Martin and Friedman (2000), cheerfulness was categorized as a measure of Agreeableness.

Rationality was not categorized into the Big Five because it measures suppression of aggression, which does not easily fall into one of the five broad domains.

The discrepancy in the Hazard ratios results from the fact that the Neuroticism scores were continuous and the Conscientiousness scores were trichotomized.

Similarly, several studies have shown that dispositions reflecting Positive Emotionality or Extraversion were associated with longevity. For example, nuns who scored higher on an index of Positive Emotionality in young adulthood tended to live longer, even when controlling for age, education, and linguistic ability (an aspect of cognitive ability; Danner, Snowden, & Friesen, 2001). Similarly, Optimism was related to higher rates of survival following head and neck cancer (Allison, Guichard, Fung, & Gilain, 2003). In contrast, several studies reported that Neuroticism and Pessimism were associated with increases in one’s risk for premature mortality (Abas, Hotopf, & Prince, 2002; Denollet et al., 1996; Schulz, Bookwala, Knapp, Scheier, & Williamson, 1996; Wilson, Mendes de Leon, Bienias, Evans, & Bennett, 2004). It should be noted, however, that two studies reported a protective effect of high Neuroticism (Korten et al., 1999; Weiss & Costa, 2005).

The domain of Agreeableness showed a less clear association to mortality, with some studies showing a protective effect of high Agreeableness (Wilson et al., 2004) and others showing that high Agreeableness contributed to mortality (Friedman et al., 1993). With respect to the domain of Openness to Experience, two studies showed that Openness or facets of Openness, such as creativity, had little or no relation to mortality (Osler et al., 2002; Wilson et al., 2004).

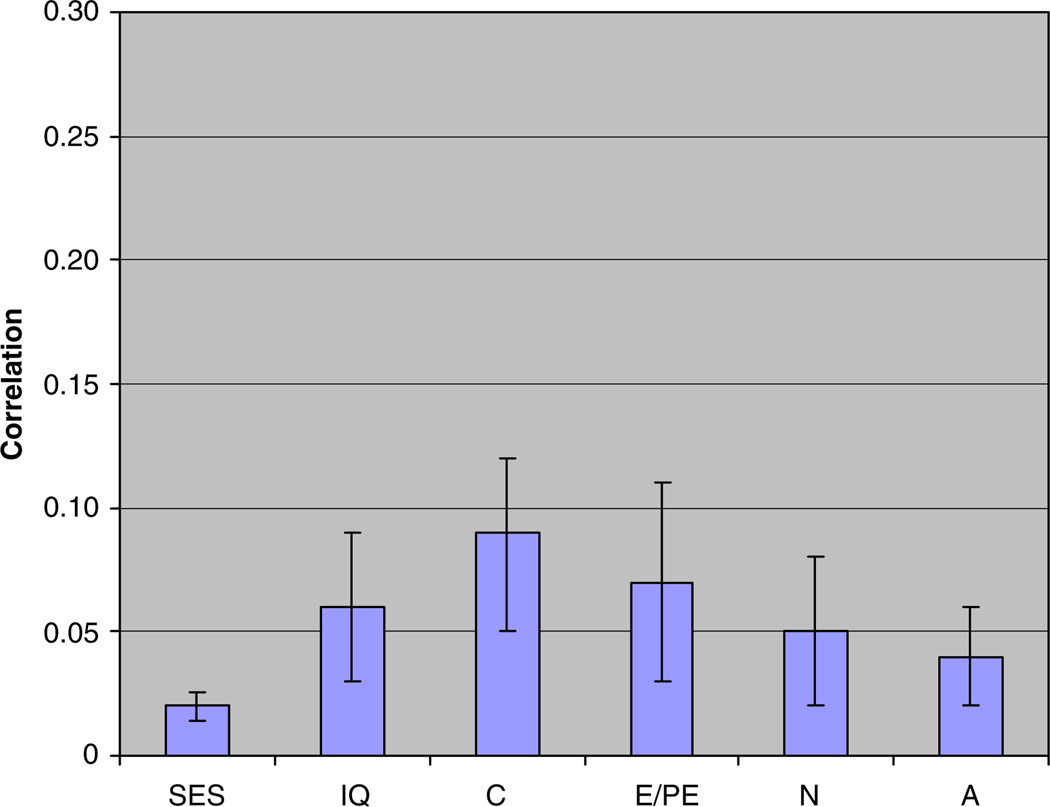

Because aggregating all personality traits into one overall effect size washes out important distinctions among different trait domains, we examined the effect of specific trait domains by aggregating studies within four categories: Conscientiousness, Positive Emotion/Extraversion, Neuroticism/Negative Emotion, and Hostility/Disagreeableness.5 Our Conscientiousness domain included four studies that linked Conscientiousness to mortality. Because only two of these studies reported the information necessary to compute an average relative risk ratio, we only examined the correlation metric. When translated into a correlation metric, the average effect size for Conscientiousness was −.09 (CIs = −.12 and −.05), indicating a protective effect. Our Extraversion/Positive Emotion domain included six studies that examined the effect of extraversion, positive emotion, and optimism. The average relative risk ratio for the low Extraversion/Positive Emotion was 1.04 (CIs = 1.00 and 1.10) with a corresponding correlation effect size for high Extraversion/Positive Emotion being −.07 (−.11, −.03), with the latter showing a statistically significant protective effect of Extraversion/Positive Emotion. Our Negative Emotionality domain included twelve studies that examined the effect of neuroticism, pessimism, mental instability, and sense of coherence. The average relative risk ratio for the Negative Emotionality domain was 1.15 (CIs = 1.04 and 1.26), and the corresponding correlation effect size was .05 (CIs = .02 and .08). Thus, Neuroticism was associated with a diminished life span. Nineteen studies reported relations between Hostility/Disagreeableness and all-cause mortality, with notable heterogeneity in the effects across studies. The risk ratio population estimate showed an effect equivalent to, if not larger than, the remaining personality domains (risk ratio = 1.14; CIs = 1.06 and 1.23). With the correlation metric, this effect translated into a small but statistically significant effect of .04 (CIs = .02 and .06), indicating that hostility was positively associated with mortality. Thus, the specific personality traits of Conscientiousness, Positive Emotionality/Extraversion, Neuroticism, and Hostility/Disagreeableness were stronger predictors of mortality than was SES when effects were translated into a correlation metric. The effect of personality traits on mortality appears to be equivalent to IQ, although the additive effect of multiple trait domains on mortality may well exceed that of IQ.

Why would personality traits predict mortality? Personality traits may affect health and ultimately longevity through at least three distinct processes (Contrada, Cather, & O’Leary, 1999; Pressman & Cohen, 2005; Rozanski, Blumenthal, & Kaplan, 1999; T.W. Smith, 2006). First, personality differences may be related to pathogenesis or mechanisms that promote disease. This has been evaluated most directly in studies relating various facets of Hostility/Disagreeableness to greater reactivity in response to stressful experiences (T.W. Smith & Gallo, 2001) and in studies relating low Extraversion to neuroendocrine and immune functioning (Miller, Cohen, Rabin, Skoner, & Doyle, 1999) and greater susceptibility to colds (Cohen, Doyle, Turner, Alper, & Skoner, 2003a, 2003b). Second, personality traits may be related to physical-health outcomes because they are associated with health-promoting or health-damaging behaviors. For example, individuals high in Extraversion may foster social relationships, social support, and social integration, all of which are positively associated with health outcomes (Berkman, Glass, Brissette, & Seeman, 2000). In contrast, individuals low in Conscientiousness may engage in a variety of health-risk behaviors such as smoking, unhealthy eating habits, lack of exercise, unprotected sexual intercourse, and dangerous driving habits (Bogg & Roberts, 2004). Third, personality differences may be related to reactions to illness. This includes a wide class of behaviors, such as the ways individuals cope with illness (e.g., Scheier & Carver, 1993), reduce stress, and adhere to prescribed treatments (Kenford et al., 2002).

These processes linking personality traits to physical health are not mutually exclusive. Moreover, different personality traits may affect physical health via different processes. For example, facets of Disagreeableness may be most directly linked to disease processes, facets of low Conscientiousness may be implicated in health-damaging behaviors, and facets of Neuroticism may contribute to ill-health by shaping reactions to illness. In addition, it is likely that the impact of personality differences on health varies across the life course. For example, Neuroticism may have a protective effect on mortality in young adulthood, as individuals who are more neurotic tend to avoid accidents in adolescence and young adulthood (Lee, Wadsworth, & Hotopf, 2006). It is apparent from the extant research that personality traits influence outcomes at all stages of the health process, but much more work remains to be done to specify the processes that account for these effects.

The Predictive Validity of Personality Traits for Divorce

Next, we considered the role that SES, cognitive ability, and personality traits play in divorce. Because there were fewer studies examining these issues, we included prospective studies of SES, IQ, and personality that did not control for many background variables.

In terms of SES and IQ, we found 11 studies that showed a wide range of associations with divorce and marriage (see Table 3).6 For example, the SES of the couple in one study was unsystematically related to divorce (Tzeng & Mare, 1995). In contrast, Kurdek (1993) reported relatively large, protective effects for education and income for both men and women. Because not all these studies reported relative risk ratios, we computed an aggregate using the correlation metric and found the relation between SES and divorce was −.05 (CIs = −.08 and − .02), which indicates a significant protective effect of SES on divorce across these studies. Contradictory patterns were found for the two studies that predicted divorce and marital patterns from measures of cognitive ability. Taylor et al. (2005) reported that IQ was positively related to the possibility of male participants ever marrying but was negatively related to the possibility of female participants ever marrying. Data drawn from the Mills Longitudinal study (Helson, 2006) showed conflicting patterns of associations between verbal and mathematical aptitude and divorce. Because there were only two studies, we did not examine the average effects of IQ on divorce.

TABLE 3.

SES and IQ Effects on Divorce

| Study | N | Outcome | Length of study |

Control variables | Predictor | Results | Est. r |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amato & Rogers, 1997 | 1,742 couples from the Panel Study of Marital Instability over the Life Course |

Divorce | 12 years | Age at marriage, prior cohabitation, ethnicity, years married, church attendance, education, employment, husband’s income, remarriage, parents divorced |

Wife’s income | p = .01 | re = .06 |

| Bentler & Newcomb, 1978 | 77 couples (53 males, 24 females) |

Divorce | 4 years | Women’s education occupation |

p = .05 p = .05 |

re = −.22 re = −.22 |

|

| Fergusson, Horwood, & Shannon, 1984 | 1,002 families from the Christchurch Child Development Study |

Family breakdown | 5 years | Maternal age, family size, church attendance, marriage type, length of marriage, planning of pregnancy |

SES | T = 2.86 | rt = −.09 |

| Helson, 2006 | 98 women | Divorce | 31 years | SAT Verbal SAT Math |

r = −.06 r = .08 |

||

| Holley, Yabiku, & Benin, 2006 | 670 mothers from the Intergenerational Study of Parents and Children |

Divorce | 13 years | Age at marriage, religion, church attendance, previous cohabitation, number of children |

Similarities subtest from WAIS |

t = −3.02 | rt = −.12 |

| Jalovaara, 2001 | 766,637 first marriages from Finland |

Divorce | 2 years | Duration of marriage, wife’s age at marriage, family composition, degree of urbanization |

Wife’s high education Wife’s low occupational class Wife’s high income |

HR = 0.69 (0.66, 0.73) HR = 1.34 (1.27, 1.42) HR = 1.03 (0.92, 1.14) |

rhr = −.02 rhr = .01 rhr = .00 |

| Husband’s high education Husband’s low occupational class Husband’s high income |

HR = 0.66 (0.63, 0.69) HR = 1.51 (1.44, 1.58) HR = 0.55 (0.51, 0.58) |

rhr = −.02 rhr = .02 rhr = −.02 |

|||||

| Kurdek, 1993 | 286 couples | Divorce | 5 years | High education (husband) |

F(1, 284) = 30.28, p < .0000000008 |

rF = −.31 re = −.34 |

|

| High income (husband) |

F(1, 284) = 9.32, p = .0025 |

rF = −.18 re = −.18 |

|||||

| High income (wife) |

F(1, 284) = 5.11, p = .025 |

rF = −.13 re = −.13 |

|||||

| Orbuch, Veroff, Hassan, & Horrocks, 2002 | 373 couples |

Divorce |

14 years |

Race |

Years education (wife) Household income Years of education (husband) |

B = −.33 (.06) p = .001 B = .00 (.01) B = −.20 (.06) p = .001 |

rB = −.28 re = −.17 rB = .00 rB = −.17 re = −.17 |

| A.W. Smith & Meitz, 1985 | 3,737 families from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics |

Divorce | 10 years | Education level | p = .001 | re = −.05 | |

| Taylor et al, 2005 | 883 from the Scottish Mental Survey and Midspan studies |

Ever married | 39 years | Social class | IQ | OR men = 1.21 (0.85–1.73) p = .23 |

ror = .04 re = .04 |

| OR women = 0.50 (0.32–0.78) p = .002 |

ror = −.17 re = −.17 |

||||||

| IQ | Social class | OR men = 1.25 (0.92–1.68) p = .15 |

ror = .06 re = .06 |

||||

| OR women = 0.67 (0.49–0.92) p = .015 |

ror = −.14 re = −.13 |

||||||

| Tzeng & Mare, 1995 | 17,024 from NLSY, NLSYM, and NLSYW studies |

Annual probability of marital disruption |

9–15 Years | Age at marriage, presence of children, family status while growing up, number of marriages, race, cohort |

Couple education | Z = −6.8 | rz = −.05 |

| Couple income | Z = .51 | rz = .00 |

Note. Confidence intervals are given in parentheses. SES = socioeconomic status; HR = hazard ratio; RR = relative risk ratio; OR = odds ratio; rz = correlation estimated from the z score and sample size; ror = correlation estimated from the odds ratio; rF = correlation estimated from F test; rB = correlation estimated from the reported unstandardized beta weight and standard error; re = requivalent (correlation estimated from the reported p value and sample size); WAIS = Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale; NLSY = National Longitudinal Study of Youth; NLSYM = National Longitudinal Study of Young Men; NLSYW = National Longitudinal Study of Young Women.

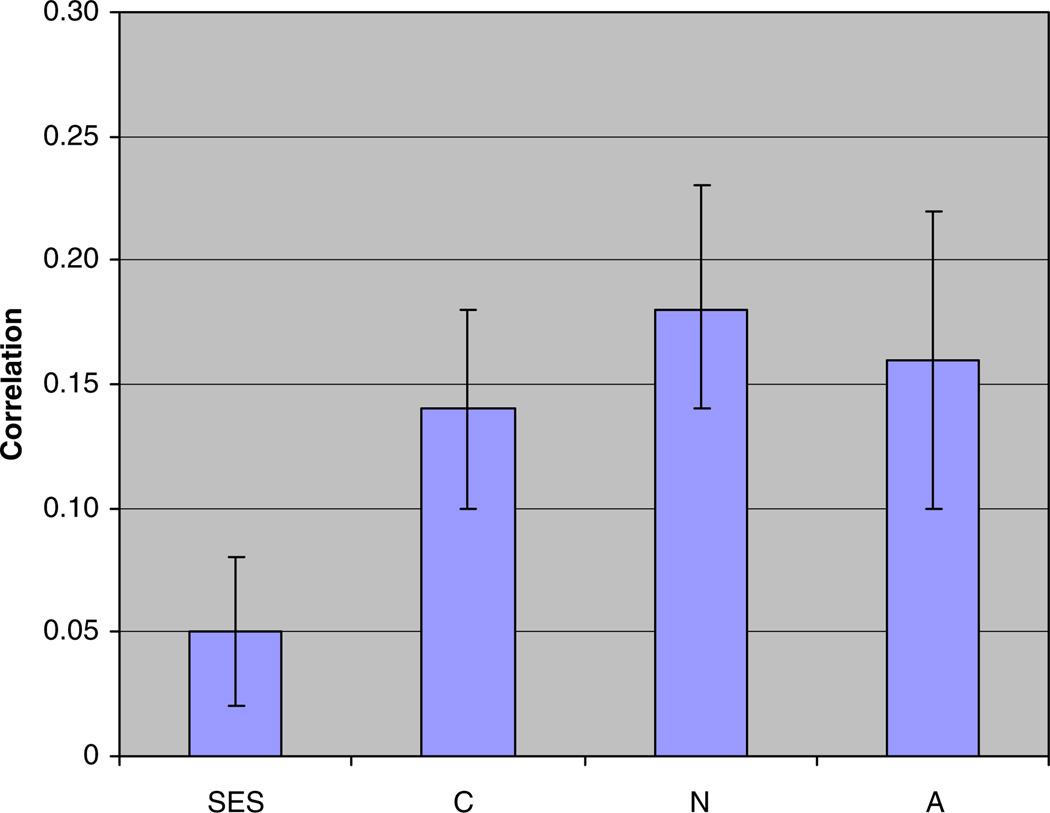

Table 4 shows the data from thirteen prospective studies testing whether personality traits predicted divorce. Traits associated with the domain of Neuroticism, such as being anxious and overly sensitive, increased the probability of experiencing divorce (Kelly & Conley, 1987; Tucker, Kressin, Spiro, & Ruscio, 1998). In contrast, those individuals who were more conscientious and agreeable tended to remain longer in their marriages and avoided divorce (Kelly & Conley, 1987; Kinnunen & Pulkkenin, 2003; Roberts & Bogg, 2004). Although these studies did not control for as many factors as the health studies, the time spans over which the studies were carried out were impressive (e.g., 45 years). We aggregated effects across these studies for the trait domains of Neuroticism, Agreeableness, and Conscientiousness with the correlation metric, as too few studies reported relative risk outcomes to warrant aggregating. When so aggregated, the effect of Neuroticism on divorce was .17 (CIs = .12 and .22), the effect of Agreeableness was − .18 (CIs = −.27 and −.09), and the effect of Conscientiousness on divorce was −.13 (CIs = −.17 and −.09). Thus, the predictive effects of these three personality traits on divorce were greater than those found for SES.

TABLE 4.

Personality Traits and Marital Outcomes

| Study | N | Outcome | Time | Controls | Predictors | Results | Est. r |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bentler & Newcomb, 1978 | 77 couples (53 males, 24 females) |

Divorce | 4 years | Men’s extraversion orderliness Women’s clothes consciousness Congeniality |

p = .05 p = .05 p = .05 p = .05 |

re = .27 re = .27 re = −.40 re = −.40 |

|

| Caspi, Elder, & Bern, 1987 | 87 men from the Berkeley Guidance Study |

Divorce | 31 years | Childhood ill-temperedness | p = .02 | re = .25 | |

| Huston, Caughlin, Houts, Smith, & George, 2001 | 152 couples | Early divorce | Few months after marriage |

Gender, affectional expression, love, contrariness, ambivalence, negativity Gender, affectional expression, love, contrariness, ambivalence, negativity |

Responsiveness (Agreeableness) Contrariness (Neuroticism) |

F(4, 147) = 4.49, p <.01 F(4, 147) = 1.29, (p values not available) |

rF = −.17 re = −.21 rF = .09 |

| Jockin, McGue, & Lykken, 1996 | 1,490 female and 696 male twins |

Ever divorced | Cross-sectional | Positive Emotionality (women) Positive Emotionality (men) Negative Emotionality (women) Negative Emotionality (men) Constraint (women) Constraint (men) |

d = .23 p < .01 d = .21 p < .01 d = .21 p < .01 d = .20 p < .01 d = −.34 p < .01 d = −.20 p < .01 |

rd = .11 re = .07 rd = .10 re = .10 rd = .10 re = .10 rd = .10 re = .10 rd = −.17 re = −.10 rd = −.10 re = −.10 |

|

| Kelly & Conley, 1987 | 556 married men and women |

Marital compatibility (divorced versus happily married) |

45 years | Husband’s Neuroticism Husband’s impulse control Wife’s Neuroticism |

r = .27 r = −.25 r = .38 |

r = .27 r = −.25 r = .38 |

|

| Kinnunen & Pulkkinen, 2003 | 108 women and 109 men from the Jyvaskyla Longitudinal Study of Personality and Social Development |

Divorced versus intact marriage at age 36 |

28, 22, or 9 years | Women’s age 8 Aggression Women’s age 8 Lability Women’s age 27 Conscientiousness Women’s age 27 Agreeableness Men’s age 8 Aggression Men’s age 8 Compliance Men’s age 14 Aggression Men’s age 14 Compliance Men’s age 27 Conscientiousness Men’s age 27 Agreeableness |

d =.69 d = .43 d = −.12 d = −.54 d = .68 d = .59 d = .57 d = .74 d = .82 d = .61 |

rd = .30 rd = .19 rd = −.05 rd = −.24 rd = .26 rd = .23 rd = .22 rd = .28 rd = .31 rd = .24 |

|

| Kurdek, 1993 | 286 couples | Divorce | 5 years | Neuroticism (husband) Neuroticism (wife) Conscientiousness (husband) Conscientiousness (wife) Positive Emotionality (husband) |

F(1, 284) = 17.34, p = .000005 F(1, 284) = 14.21, p = .0002 F(1, 284) = −2.78, p = .096 F(1, 284) = −4.16, p = 042 d = .21 p < .01 |

rF = .25 re = .24 re = .22 rF = .22 re = −.10 rF = −.10 rF = −.12 re = −.12 rd = .10 re = .10 |

|

| Lawrence & Bradbury, 2001 | 60 couples from Los Angeles |

Divorce | 4 years | Aggressiveness | OR = 2.37 p = .06 |

re = .24 ro = .23 |

|

| Loeb, 1966 | 639 college students | Divorce | 13 years | Women’s MMPI psychopathic deviancy Men’s MMPI psychopathic deviancy Men’s MMPI hypochondriasis Men’s MMPI hysteria Men’s MMPI schizophrenia |

p < .025 p < .025 p < .005 p < .025 p < .05 |

re = .13 re = .13 re = .16 re = .13 re = .11 |

|

| McCranie & Kahan, 1986 | 431 physicians | Number of divorces |

25 years | MMPI psychopathic deviancy | r = .13 | r = .13 | |

| Roberts & Bogg, 2004 | 99 women from the Mills Longitudinal Study |

Ever divorced | 22 years | Responsibility | r = −.21 | r = −.21 | |

| Skolnick, 1981 | 122 members of the IHD longitudinal studies |

Divorce versus satisfied marriage |

Cognitively invested Emotionally aggressive Nurturant Under controlled |

p = .06 p = .08 p = .06 p = .008 |

re = −.17 re = .16 re = −.17 re = .24 |

||

| Tucker et al., 1998 | 773 from the Normative Aging Study |

Divorce | 26 years | Age at marriage, education |

Inadequacy Anxiety Sensitivity Anger Tension |

OR = 2.40 (1.36, 4.35) p < .01 OR = 2.80 (1.55, 5.15) p < .001 OR = 2.80 (1.50, 5.25) p < .01 OR = 2.70 (1.54, 4.71) p < .001 OR = 1.20 (0.61, 2.51) |

ror = .11 re = .09 ror = .12 re = .12 ror = .12 re = .09 ror = .13 re = .12 ror = .02 |

| 968 members of the Terman Life Cycle Study |

Divorce | 53 to 78 years | Sex, education, age at marriage |

Conscientiousness Perseverance Sympathy Not egotistical |

OR parent rating = 0.92 (0.84, 1.01) OR teacher rating = 0.92 (0.83, 1.01) OR parent rating = 1.01 (0.92, 1.11) OR teacher rating = 0.95 (0.86, 1.05) OR parent rating = 0.94 (0.85, 1.02) OR teacher rating = 0.95 (0.84, 1.07) OR parent rating = 0.95 (0.87,1.03) OR teacher rating = 0.96 (0.87, 1.05) |

ror = −.07 ror = −.08 ror = .01 ror = −.05 ror = −.06 ror = −.04 ror = −.05 ror = −.04 |

Note. Confidence intervals are given in parentheses. HR = hazard ratio; RR = relative risk ratio; OR = odds ratio; rd = Correlation estimated from the d score; ror = correlation estimated from the odds ratio; rF = correlation estimated from F test; re = requivalent (correlation estimated from the reported p value and sample size); MMPI = Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory; IHS = Institute of Human Development.

Why would personality traits lead to divorce or conversely marital stability? The most likely reason is because personality traits help shape the quality of long-term relationships. For example, Neuroticism is one of the strongest and most consistent personality predictors of relationship dissatisfaction, conflict, abuse, and ultimately dissolution (Karney & Bradbury, 1995). Sophisticated studies that include dyads (not just individuals) and multiple methods (not just self reports) increasingly demonstrate that the links between personality traits and relationship processes are more than simply an artifact of shared method variance in the assessment of these two domains (Donnellan, Conger, & Bryant, 2004; Robins, Caspi, & Moffitt, 2000; Watson, Hubbard, & Wiese, 2000). One study that followed a sample of young adults across their multiple relationships in early adulthood discovered that the influence of Negative Emotionality on relationship quality showed cross-relationship generalization; that is, it predicted the same kinds of experiences across relationships with different partners (Robins, Caspi, & Moffitt, 2002).

An important goal for future research will be to uncover the proximal relationship-specific processes that mediate personality effects on relationship outcomes (Reiss, Capobianco, & Tsai, 2002). Three processes merit attention. First, personality traits influence people’s exposure to relationship events. For example, people high in Neuroticism may be more likely to be exposed to daily conflicts in their relationships (Bolger & Zuckerman, 1995; Suls & Martin, 2005). Second, personality traits shape people’s reactions to the behavior of their partners. For example, disagreeable individuals may escalate negative affect during conflict (e.g., Gottman, Coan, Carrere, & Swanson, 1998). Similarly, agreeable people may be better able to regulate emotions during interpersonal conflicts (Jensen-Campbell & Graziano, 2001). Cognitive processes also factor in creating trait-correlated experiences (Snyder & Stukas, 1999). For example, highly neurotic individuals may overreact to minor criticism from their partner, believe they are no longer loved when their partner does not call, or assume infidelity on the basis of mere flirtation. Third, personality traits evoke behaviors from partners that contribute to relationship quality. For example, people high in Neuroticism and low in Agreeableness may be more likely to express behaviors identified as detrimental to relationships such as criticism, contempt, defensiveness, and stonewalling (Gottman, 1994).

The Predictive Validity of Personality Traits for Educational and Occupational Attainment

The role of personality traits in occupational attainment has been studied sporadically in longitudinal studies over the last few decades. In contrast, the roles of SES and IQ have been studied exhaustively by sociologists in their programmatic research on the antecedents to status attainment. In their seminal work, Blau and Duncan (1967) conceptualized a model of status attainment as a function of the SES of an individual’s father. Researchers at the University of Wisconsin added what they considered social-psychological factors (Sewell, Haller, & Portes, 1969). In this Wisconsin model, attainment is a function of parental SES, cognitive abilities, academic performance, occupational and educational aspirations, and the role of significant others (Haller & Portes, 1973). Each factor in the model has been found to be positively related to occupational attainment (Hauser, Tsai, & Sewell, 1983). The key question here is to what extent SES and IQ predict educational and occupational attainment holding constant the remaining factors.

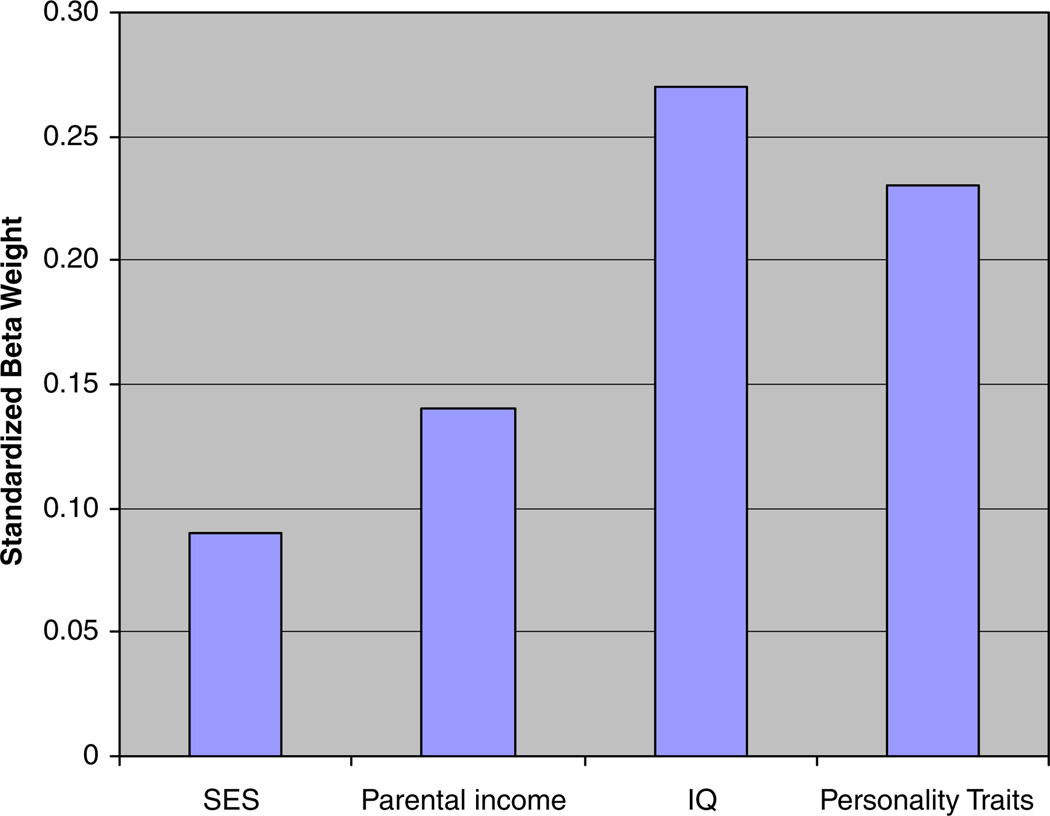

A great deal of research has validated the structure and content of the Wisconsin model (Sewell & Hauser, 1980; Sewell & Hauser, 1992), and rather than compiling these studies, which are highly similar in structure and findings, we provide representative findings from a study that includes three replications of the model (Jencks, Crouse, & Mueser, 1983). As can be seen in Table 5, childhood socioeconomic indicators, such as father’s occupational status and mother’s education, are related to outcomes, such as grades, educational attainment, and eventual occupational attainment, even after controlling for the remaining variables in the Wisconsin model. The average beta weight of SES and education was .09.7 Parental income had a stronger effect, with an average beta weight of .14 across these three studies. Cognitive abilities were even more powerful predictors of occupational attainment, with an average beta weight of .27.

TABLE 5.

SES, IQ, and Status Attainment

| Study | N | Outcome | Time span | Control variables | Predictor | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jencks, Crouse, & Meuser, 1983 | 1,789 | Occupational attainment |

7 years | Father and mother’s SES, earnings, aptitude, grades, friends education plans, educational and occupational aspirations, education |

Father’s SES Mother’s education Parental income IQ |

β = .15 β = .09 β = .11 β = .31 |

| Earnings Education |

Father’s SES Mother’s education Parent’s income IQ Father’s SES Mothers education Parent’s income IQ |

β = −.01 β = .01 β = .16 β = .14 β = .13 β = .13 β = .14 β = .37 |

Note. SES = socioeconomic status.

Do personality traits contribute to the prediction of occupational attainment even when intelligence and socioeconomic background are taken into account? As there are far fewer studies linking personality traits directly to indices of occupational attainment, such as prestige and income, we also included prospective studies examining the impact of personality traits on related outcomes such as long-term unemployment and occupational stability. The studies listed in Table 6 attest to the fact that personality traits predict all of these work-related outcomes. For example, adolescent ratings of Neuroticism, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Conscientiousness predicted occupational status 46 years later, even after controlling for childhood IQ (Judge, Higgins, Thoresen, & Barrick, 1999). The weighted-average beta weight across the studies in Table 6 was .23 (CIs = .14 and .32), indicating that the modal effect size of personality traits was comparable with the effect of childhood SES and IQ on similar outcomes.8

TABLE 6.

Personality Traits and Occupational Attainment

| Study | N | Outcome | Time span | Control variables | Predictor | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caspi et al, 1987 | 182 members of the Berkeley Guidance Study |

Occupational attainment Erratic work life |

31 years 31 years |

IQ, education IQ, education, occupational attainment |

Childhood ill- temperedness Childhood ill- temperedness |

β = −.10 β = .45 |

| Caspi, Elder, & Bern, 1988 | 73 men from the Berkeley Guidance Study 83 women from the Berkeley Guidance Study |

Age at entry into a stable career Occupational attainment Stable participation in the labor market |

11 years 11 years 11 years |

SES, education, childhood ill- temperedness Age at entry into stable career, education, childhood ill- temperedness SES, education, childhood ill- temperedness |

Childhood shyness Childhood shyness Childhood shyness |

β = .27 β = −.05 β = −.19 |

| Helson & Roberts, 1992 | 63 women from the Mills Longitudinal Study |

Occupational attainment | 16 years | Work aspirations, husband’s individuality |

Individuality | β = .34 |

| Helson, Roberts, & Agronick, 1995 | 120 women from the Mills Longitudinal Study |

Occupational creativity | 31 years | SAT Verbal scores, status aspirations |

Creative temperament | β = .44 |

| Judge et al., 1999 | 118 Members from the IHD longitudinal studies |

Extrinsic career success | 46 years | IQ | Neuroticism Extraversion Agreeableness Conscientiousness |

β = −.21 β = .27 β = −.32 β = .44 |

| Kokko & Pulkkinen, 2000 | 311 members of the Jyvaskyla Longitudinal Study |

Long-term unemployment between ages 27 and 36 |

19 years | Aggression, child- centered parenting, school maladjustment, problem drinking, lack of occupational alternatives at age 27 |

Age 8 prosociality (emotionally stable, reliable, friendly) |

β = −.37 |

| Luster & McAdoo, 1996 | 123 members of the Perry Preschool sample |

Age 27 income | 22 years | Mother’s education, maternal involvement in kindergarten, preschool attendance, academic motivation, IQ score, 8th grade achievement, educational attainment at age 27 |

Age 5 personal behavior (teacher ratings of not lying and cheating, not using obscene words) |

β = .23 |

| Roberts, Caspi, & Moffitt, 2003a | 859 members of the Dunedin Longitudinal Study |

Occupational attainment | 8 years | IQ, SES | Negative Emotionality Constraint Positive Emotionality |

β = −.17 β = .18 β = .13 |

|

Seibert, Kraimer, & Crant, 2001 Tharenou, 2001 |