Abstract

Low-grade diffuse gliomas are a heterogeneous group of primary glial brain tumors with highly variable survival. Currently, patients with low grade diffuse gliomas are stratified into risk subgroups by subjective histopathologic criteria with significant interobserver variability. Several key molecular signatures have emerged as diagnostic, prognostic, and predictor biomarkers for tumor classification and patient risk stratification. In this review, we will discuss the impact of the most critical molecular alterations described in diffuse (IDH1/2, 1p/19q co-deletion, ATRX, TERT, CIC, FUBP1) and circumscribed (BRAF-KIAA1549, BRAFV600E, C11orf95–RELA fusion) gliomas. These molecular features reflect tumor heterogeneity and have specific associations with patient outcome that determine appropriate patient management. This has led to an important, fundamental shift towards developing a molecular classification of WHO grade II-III diffuse glioma.

Introduction

In the United States 28% of all primary brain and central nervous system (CNS) tumors are diagnosed as gliomas 1. Based on their infiltrative behavior, gliomas are subdivided into two main subgroups: circumscribed and diffuse. The circumscribed gliomas are generally amenable to total surgical resection and patients with these tumors have improved outcomes compared to patients with diffuse gliomas. The aggressive phenotype of diffuse gliomas is attributed to the tendency of the malignant glioma cells to infiltrate the neuropil along axons and travel far away from the primary tumor site (Figure 1). A malignant glioma cell may travel to the opposite cerebral hemisphere. For this reason diffuse gliomas cannot be completely surgically resected (Figure 1c). Diffuse gliomas encompass two main histological subtypes (astrocytoma and oligodendroglioma) of which a third subtype is derived (mixed oligoastroytoma). Histological criteria established by the World Health Organization (WHO), further stratify gliomas into four grades of aggressiveness (WHO I-IV) 2. WHO grade I is reserved for circumscribed glial and glio-neuronal entities usually with favorable prognosis, while diffuse gliomas comprise the more aggressive WHO grades II-IV (Table 1) 2. Patients with astrocytomas generally have worse outcomes than patients with oligodendrogliomas (Table 2) 1.

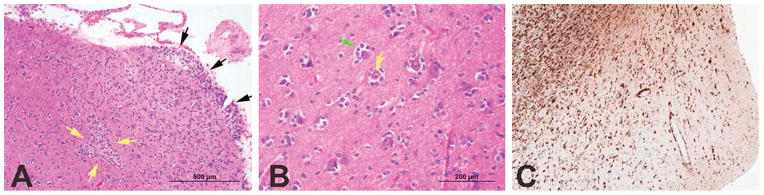

Figure 1.

Diffuse gliomas are aggressive neoplasms that tend to infiltrate along dendrites and axons and travel long distances from the primary site of origin. Malignant glioma cells are shown infiltrating the cortex and forming aggregates along a blood vessel (yellow arrows) extending all the way to the leptomeningeal surface (black arrows) (A – H&E, Obj: 100X). A higher power of the cortex highlights neoplastic glioma cells (green arrow) surrounding the neurons (yellow arrow) (B – H&E, Obj: 200X). A special immunohistochemical stain for the mutated IDH-R132H protein highlights (in brown) malignant glioma cells infiltrating the normal (pale) subcortical and cortical tissue – note how the subcortex has an incresed density of glioma cells (left upper corner) compared to the superficial cortex (right lower corner) (C – IDH1-R132H, Obj: 40X, scale not available).

Table 1.

Classification and assigned grading of gliomas after the current WHO system 2.

| WHO grade | ||

|---|---|---|

| Circumscribed | Astrocytic | |

| Subependymal giant cell astrocytoma | I | |

| Pilocytic astrocytoma | I | |

| Pilomyxoid astrocytoma | II | |

| Pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma | II | |

| Ependymal | ||

| Subependymoma | I | |

| Myxopapillary ependymoma | I | |

| Ependymoma | II | |

| Anaplastic ependymoma | III | |

| Diffuse | Diffuse astrocytoma | II |

| Oligodendroglioma | II | |

| Mixed oligoastrocytoma | II | |

| Anaplastic astrocytoma | III | |

| Anaplastic oligodendroglioma | III | |

| Anaplastic mixed oligoatrocytoma | III | |

| Glioblastoma | IV | |

| Other | Angiocentric glioma | I |

| Desmoplastic infantile astrocytoma | I | |

| Chordoid glioma of the third ventricle | II | |

| Mixed glio-neuronal tumors | Ganglioglioma | I |

| Anaplastic ganglioglioma | III | |

| Desmoplastic infantile ganglioglioma | I | |

| Papillary glioneuronal tumour | I | |

| Rosette-forming glioneuronal tumour of the fourth ventricle | I | |

| Dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumour | I | |

Table 2.

Five-year relative survival rates for patients with diffuse glioma 1.

| Diffuse glioma (WHO grade) | 5-Year relative survival rate (%)(95% Confidence Interval) |

|---|---|

| Oligodendroglioma (II) | 79.5 (77.9–81) |

| Mixed oligoastrocytoma (II-III) | 61.1 (58.6–63.6) |

| Anaplastic oligodendroglioma (III) | 52.2 (49.1–55.1) |

| Astocytoma (II) | 47.4 (46–48.8) |

| Anaplastic astrocytoma (III) | 27.3 (25.6–28.9) |

| Glioblastoma (IV) | 5 (4.8–5.4) |

While histologic criteria for diagnosing the most aggressive diffuse glioma (i.e. glioblastoma) are clear, there is extreme variability in interpretation of current morphological criteria and in diagnostic reproducibility for grade II and III diffuse glioma among pathologists 3–6. Several molecular signatures have now been identified in gliomas, with important diagnostic, prognostic, and/or predictive roles. These genetic alterations have led to further stratification of gliomas into several distinct subgroups. The addition of genetic markers offer better prognostic patient stratification compared to WHO grading alone. Guidelines for a combined molecular-morphologic approach to glioma diagnosis are under development 7.

The treatment of WHO grade II-III diffuse gliomas continues to evolve. Retrospective molecular analysis of tumors from patients enrolled in randomized clinical trials have called into question the use of standard histologic grading and have emphasized the relevance of key molecular alterations as important predictive biomarkers with implications for determining appropriate tumor management.

Histopathological classification of WHO grade II-III diffuse glioma

Since Bailey and Cushing’s initial attempt at brain tumor classification in 1926 8, 9, histological examination has been the mainstay method for risk class assignment, patient outcome stratification, therapy guidelines, and stratification for clinical trials 2, 3, 10. Several potential issues arising during histological examination are responsible for the significant inter-observer variability in achieving diagnostic reproducibility. For example, the current WHO criterion for grade III designation of astrocytomas (i.e. “brisk mitotic activity” 2) does not clearly specify any mitotic figure cutoffs and is, therefore, ambiguous and subjective and often based on the pathologist’s individual experience and bias. Similarly, the criteria for the “mixed oligoastrocytoma” category (i.e. “recognition of neoplastic glial cells with convincing astrocytic or oligodendroglial phenotypes” 2) are subjective. The pathologist’s expertise and experience in neuropathology also significantly impacts accuracy of diagnosis. In a large oncologic center study investigating the rate of diagnosis disagreement after expert neuropathology review, approximately 40% of case reviews had some type of disagreement with the original diagnosis, of which about 9% were serious with immediate impact on treatment 11. Another potential problem in interpretation can be caused by mistakenly omitting foci of high-grade histology (i.e. missing slides from the resection specimen or alternatively, limited surgical sampling in subtotal resections or biopsies and/or suboptimal specimen sampling of the resected specimen) 3–6, 11. Due to one or several of these issues, the histopathologic consensus among neuropathologists after a single review is reached in only approximately 50% of cases 5. Although this number could be improved after several case reviews, 5 it is imperative to implement more objective criteria and/or incorporate ancillary modalities alongside histological parameters in order to significantly improve the high rate of inter-observer variability in histopathologic diagnosis and classification of diffuse gliomas.

Molecular features of WHO II-III diffuse gliomas

The current WHO classification does not comprehensively reflect diffuse glioma biology and patient outcome. There is extensive evidence that tumors from different patients that have indistinguishable morphology under the microscope do not necessarily share the same biology and do not necessarily reflect similar patient outcomes 12–16. Molecular subgroups of diffuse glioma, heterogeneous in WHO grade, with different survival outcomes have been described. The use of molecular stratification was superior in predicting outcome compared to the WHO grade alone 15.

Isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) mutations in diffuse gliomas

Key molecular markers in WHO grade II-III diffuse glioma include IDH 1 and 2 (IDH1/2) mutations. These genes encode the Krebs/citric acid cycle family of metabolic enzymes 17. IDH mutations in diffuse glioma were initially described in 2008 18 but occur at lower frequencies in other malignancies 19–24. In diffuse glioma IDH1 mutations occur more commonly (>90%) than IDH2 mutations and are mutually exclusive. IDH mutations are common in grade II-III diffuse glioma (~65–80%) and secondary glioblastoma (~80%) (i.e. glioblastoma that arise following progression from a grade II or III diffuse glioma) while primary glioblastomas usually lack or show a very low frequency of IDH mutations (~5%) 25–32. IDH gene family mutations, the most common of which are IDH1R132H and IDH2R172K, confer both loss and gain of function that impacts epigenetic regulation through accumulation of 2-hydroxyglutarate and inhibition of α-ketoglutarate-dependent deoxygenases 17, 33–35. The impact of mutant IDH induces a hypermethylator phenotype 36, the glioma-CpG island methylator phenotype (G-CIMP) 37. G-CIMP is characteristic of grade II-III diffuse glioma, is associated with improved prognosis, and with a proneural molecular gene expression signature 38, 39.

IDH family mutations are early 25, 40 and consistent 40, 41 molecular events in the development of a glioma and are complemented by subsequent mutually exclusive glioma lineage specific genetic alterations, such as TP53 and alpha thalassemia/mental retardation syndrome X-linked (ATRX) mutations. These latter mutations are associated with the astrocytic phenotype 42–47. On the other hand, 1p/19q co-deletion 39, 43, 46 is associated with mutations in the homolog of Drosophila capicua gene (CIC) 42, 48 and/or far-upstream binding protein 1 gene (FUBP1) and with the oligodendroglial phenotype 42, 49. These molecular markers strongly support the predominant monoclonal origin of mixed oligoastrocytomas demonstrated by microdissection studies. 41, 50, 51 These molecular markers may help to further classify this controversial mixed glioma category into specific subclasses of either astrocytoma or oligodendroglioma 52.

In addition to its important diagnostic role, IDH mutations also have a significant prognostic role in high-grade diffuse glioma (WHO grade III and IV) independent of WHO grade in some instances 29, 30, 32, 42, 53–56. On the other hand, the prognostic role of IDH mutations in WHO grade II diffuse glioma has not been completely elucidated 40, 57–63. These mutations do not appear to have prognostic significance in non-CNS malignancies 21, 23. Similarly, the predictive role of IDH mutations has not been clarified. Very few studies suggest a potential advantage of the use of IDH mutations for determining treatment response in anaplastic diffuse gliomas. Two randomized phase III clinical trials [Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) 9402 and European Organisation for the Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) 26951] have now reported a similar improved overall survival benefit to a combined regimen using radiotherapy and PCV specifically in patients with anaplastic gliomas that are IDH mutant and 1p/19q non-co-deleted 64, 65. The predictive role of IDH mutations remains to be further investigated along with the possible prognostic implication of the IDH driven G-CIMP in grade II-III gliomas 37, 38, 66, 67. Of note, a promising IDH1R132H specific inhibitor drug (AGI-5198) has shown significant activity in pre-clinical models 68 and is currently in phase 1 clinical trials for solid tumors 69, 7069, 7069, 7069, 70(69, 70)(69, 70)69, 70,29, 84. Multiple other agents targeting mutant IDH are also under investigation.

IDHR132H mutation can be easily detected clinically by immunohistochemistry (Figure 1C). The expression of mutated IDH1R132H protein confirms mutation. Cases that are IDH1R132H immunonegative can be further interrogated by DNA sequencing for other IDH1 or IDH2 mutations. Since mutations are mainly present in codons 132 and 172 respectively, sequencing can be limited to these codons 17. At our institution all grade II-III diffuse gliomas and glioblastomas in young patients (less than age 50) are interrogated in this manner 71.

Chromosomes 1p/19q loss of heterozygosity in diffuse gliomas

Another important molecular marker in diffuse glioma is the presence of 1p/19q co-deletion, the molecular signature of oligodendroglioma, initially described in 1994 4, 39, 48, 72–74. The proposed mechanism of formation of this chromosomal abnormality is a translocation between 1p and 19q leading to the derivative chromosome, der(1;19)(q10;p10). This derivative chromosome was demonstrated in a small number of tumors leading to the hypothesis that subsequent der(1;19)(p10;q10) formation leads to 1p/19q loss of heterozygosity 75, 76. Importantly, 1p/19q co-deletion is only present if IDH mutations are present 77; therefore, this implies an association with the G-CIMP and proneural expression phenotypes 38, 39, an association that was demonstrated in grade II-III oligodendrogliomas 39, 66. Several studies showed that 1p/19q co-deletion can aid in risk stratification of IDH mutant gliomas with IDH mutant, 1p/19q co-deleted gliomas having the best prognosis, followed by IDH mutant, 1p/19q non-co-deleted gliomas and lastly by IDH wild-type, 1p/19q non-co-deleted tumors with the worst outcome 39, 57, 63, 64, 78.

Besides prognostic significance, 1p/19q co-deletion is a marker of chemotherapeutic response 79–83. Patients with 1p/19q co-deleted diffuse gliomas responded better to adjuvant chemotherapy [either procarbazine (Matulane®, Sigma Tau Pharmaceuticals, Gaithersburg, MD)/lomustine (CCNU) (CeeNU®, Bristal-Myers Squib Company, Princeton, NJ)/vincristine (Oncovin®, Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, IN) (PCV) regimen; or temozolomide (TMZ)] 79, 81–90. The mechanism for the associated chemosensitivity remains unknown and whether 1p/19q co-deletion leads to loss of a chemoresistant gene(s) or is merely a marker of more chemosensitive clones remains to be determined.

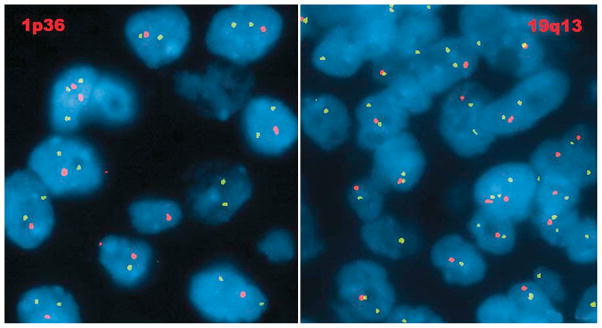

One of the most popular methods for detection of 1p/19q co-deletion is fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH). FISH permits pathologists to correlate chromosomal arm copy number findings with tissue morphology and does not require the use of normal control samples (Figure 2). Polymerase chain reaction-based loss of heterozygosity assays or array comparative genomic hydridization (CGH) are also utilized in different laboratory settings 91, 92.

Figure 2.

Diffuse glioma with 1p/19q co-deletion. The locus-specific identifier (LSI) probe, 1p36 (SpectrumOrange) and corresponding LSI 1q25 (SpectrumGreen) show two normal green signals and single abnormal orange signal in a subpopulation of interphase cells suggestive of 1p loss (left). LSI probe, 19q13 (SpectrumOrange) and corresponding LSI 19p13 (SpectrumGreen) show two normal green signals and single abnormal orange signal in a subpopulation of oligodendroglioma interphase cells suggestive of 19q loss (right) (Photographs courtesy of Prof. Dr. Adekunle Adesina, Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, TX, USA).

ATRX and telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) promoter mutations in gliomas

Two distinct telomere maintenance mechanisms have been recently described mainly in IDH mutant grade II-III diffuse glioma and primary glioblastoma. Telomeres are repetitive guanine-rich nucleotide sequences situated at each chromatid end. They are required for chromosome stability and shorten with each cell division. 93 In cancer, the length of telomere sequences is maintained either by telomerase enzyme activity or by a mechanism independent of telomerase activity called alternative lengthening of telomeres (ALT). 94, 95 Two mutually exclusive telomere maintenance mechanisms appear associated with IDH mutant WHO grade II-III diffuse gliomas. An ALT mechanism may be triggered by loss of the normal ATRX protein function of maintaining chromatin integrity for DNA replication. ATRX or death-associated protein 6 (DAXX) mutations cause dysfunctional ATRX-DAXX protein complexes that are unable to carry their normal histone chaperone function, leading to chromatin breakage, and abnormal DNA replication. 96–98 Telomeric DNA double-strand breakage may trigger ALT.43, 99–102 This mechanism is encountered in IDH mutant, 1p/19q non co-deleted grade II-III diffuse glioma 43, 44, 46, 103.

The other telomere maintenance mechanism involves point mutations in the TERT promoter. TERT encodes the catalytic subunit of telomerase. Telomerase is a RNA-dependent polymerase composed of two subunits: TERT (the catalytic subunit) and TERC (the telomerase RNA component which serves as a template for telomere extension) 104, 105. Two consistent and mutually exclusive TERT promoter point mutations (C228T and C250T) have been described in gliomas 77, 106. These mutations have been also frequently found in other non-CNS tumors, with C228T being by far more common (~80%) than C250T (~20%) overall 103, 107, 108. Point mutations in the TERT promoter region create binding sites for the E-twenty-six (Ets) family of transcription factors, 107–110 which upon binding cause two to four fold increase in transcriptional activity 107 with subsequent increased TERT mRNA expression 77. This increased mRNA expression seems to be positively correlated with the tumor’s CIC mutational status 77, likely because CIC regulates the Ets family of transcription factors 111. Chen et al. demonstrated in vitro that the increase in TERT transcriptional activity is maintained under hypoxic conditions and under treatment with TMZ 112. This second telomere maintenance mechanism is also characteristic of IDH mutant, 1p/19q co-deleted grade II-III diffuse glioma (and therefore of molecular oligodendroglioma) 103, 106, 113. In the diffuse glioma category, it is not yet clear if TERT promoter mutations confer additional prognostic benefit to the presence of IDH mutations and 1p/19q co-deletion. Most studies demonstrate improved survival in patients with IDH mutant, TERT promoter mutated grade II-III diffuse gliomas 77, 113, 114 ; however after stratification for 1p/19q co-deletion status, TERT promoter mutations demonstrate a prognostic advantage only to the 1p/19q non-co-deleted subset 114. Interestingly, TERT promoter mutations are negative prognostic biomarkers in the IDH wild-type grade II-III diffuse gliomas subset 77, 113, 114 and in primary glioblastoma 77, 103, 112, 113. In addition to obtaining IDH mutation and 1p/19q co-deletion status, identifying ATRX and TERT promoter mutations status should further enhance the stratification of diffuse gliomas.

IDH mutation– driven subgroups of WHO grade II-III diffuse glioma

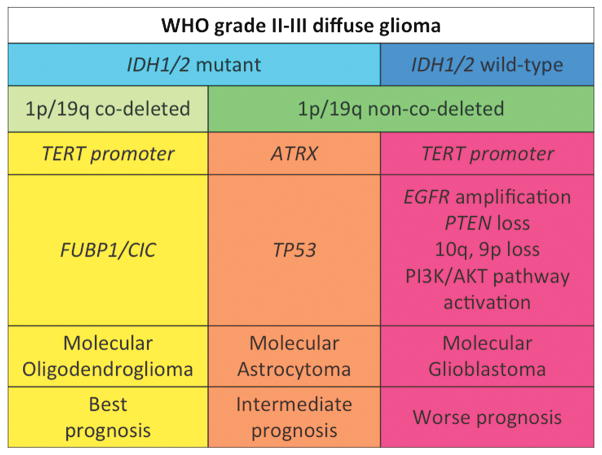

There is evidence that the presence or absence of IDH mutation is an important branch point towards grade II-III diffuse glioma subclassification. Gorovets et al. subclassified 101 grade II and III diffuse gliomas of astrocytic morphology by IDH mutation status. IDH mutant tumors were enriched in TP53 mutations, PTEN promoter methylation, and gains of 8q. Based on expression signatures, IDH mutant grade II-III astrocytomas were also subdivided into two subgroups: neuroblastic and early progenitor-like, the former enriched in mature neuronal and the latter enriched in developmental gene signatures. The early progenitor-like subgroup components were associated with TP53 mutations and several chromosomal copy number abnormalities (gains of 7p and 15q, and losses of 4q34.3, 9p23, 11p, 12q21.33, 13q, and 19q).

On the other hand IDH wild-type grade II-III astrocytomas shared EGFR amplifications, PTEN losses, PI3K/AKT molecular pathway activation, and gains of 7p and losses of 9p and 10q 15. Partial or total loss of 10q and 9p loss have been previously associated with dismal prognosis in WHO II-III diffuse glioma 115–117. This is important because the latter signatures are characteristic molecular markers of primary glioblastoma 18, 118–120. This suggests that a subgroup of grade II-III astrocytomas confined to the IDH wild-type genetic subclass is biologically identical to glioblastoma. This same group also demonstrated that these specific tumors clustered within a separate, heterogeneous subgroup defined based on expression profiling that, not surprisingly, was called pre-glioblastoma 15. Similarly Yan et al., defined an IDH wild-type subgroup based on expression profiling that was also predominantly composed of primary glioblastomas and also clustered several grade II-III diffuse gliomas 16.

A proposed classification scheme based on a summary of the molecular analysis to date for WHO II-III diffuse gliomas is shown in Figure 3. This schema may more accurately reflect underlying biology and be more representative of patient outcome than the WHO grade alone. The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) 121 group is currently working on analyzing a large cohort of WHO grade II-III diffuse gliomas of all morphologies. Extensive data derived from multiple molecular platforms were analyzed and their results are expected shortly. We can speculate that similar molecular findings will be reported as have been reported previously and that emphasize a significant difference between groups of tumors that are primarily separated by the IDH mutation status.

Figure 3.

Proposed molecular classification of WHO grade II-III diffuse glioma.

Susceptibility loci for the development of diffuse glioma

Several large genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have been performed to identify genetic variants associated with the risk of development of a glioma. These GWAS studies have identified several risk single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) loci. The reported loci with the strongest glioma risk association were rs78378222 (TP53, 17p13), rs4295627 and rs55705857 (CCDC26, 8q24.21), rs2736100 (TERT, 5p15.33), rs1920116 (TERC, 3q26.2), rs4977756 (CDKN2B, 9p21.3), rs6010620 and rs2297440 (RTEL1, 20q13.33), and rs498872 (PHLDB1, 11q23.3) 122–131. Of these, rs4295627, rs55705857 (CCDC26, 8q24.21) and rs498872 (PHLDB1, 11q23.3) are strongly associated with low-grade disease, IDH mutations 132 and 1p/19q co-deletions 127. For the former two SNPs, the risk for developing oligodendroglioma was also shown by Jenkins et al 128, 129. High-grade disease, IDH wild-type, EGFR amplification, CDKN2A p16INK4a homozygous deletion, 9p and 10q loss were linked to rs2736100 (TERT, 5p15.33) and rs6010620 (RTEL1, 20q13.33) 127. An additional SNP locus associated with high-grade glioma was rs2297440 (RTEL1, 20q13.33) 128.

Molecular features of well-circumscribed gliomas

BRAF genetic alterations are shared by pilocytic astrocytoma, ganglioglioma, and pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma. BRAF-KIAA1549 fusion-duplication, a possibly prognostic marker 133, is frequent in younger patients 134 with cerebellar pilocytic astrocytomas (~60–80%), intermediate in frequency for brainstem, hypothalamic, and optic pathway tumors (~60%) 135, and low (~20%) in supratentorial cortical tumors 136. BRAFV600E mutations are common in pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma (~60–80%) involving the temporal lobes, ganglioglioma (~30–50%) 137–139, and less commonly found in pilocytic astrocytoma (~2 to 30% depending on location). Most common locations include diencephalon, followed by cerebral cortex and brainstem, and least common in cerebellar tumors) 137.

Location-specific subgroups of ependymomas with characteristic genetic signatures have been described. Supratentorial ependymomas (~70–75%) are enriched in C11orf95–RELA fusion, driver of NF-kB cell signaling 140, 141. Posterior fossa ependymomas are comprised of two genetically and clinically distinct subgroups, group A (PFA) and B (PFB). The more aggressive PFA group is enriched in cancer-related signal transduction pathway gene signatures, exhibits the CIMP phenotype (distinct from G-CIMP), while the PFB group is CIMP negative and enriched in chromosomal number aberrations 142–144.

Conclusions

Grade II-III diffuse gliomas are heterogeneous tumors. Based on current published data, IDH mutations and 1p/19q co-deletion are major drivers of gliomagenesis and in determining outcome for grade II-III diffuse gliomas. Diffuse glioma subgroups defined based on these two molecular alterations will require further characterization in order to identify additional important biomarkers as well as for therapeutic target discovery. Continued endeavors to further characterize grade II-III glioma characterization should not only offer important information regarding many accepted clinical observations but also provide mechanisms regarding these observations. For example, why are 1p/19q co-deleted tumors more chemosensitive? Why is the improved overall survival in those patients receiving chemoradiation observed late after the median overall survival has already been reached? How should 1p/19q non-co-deleted tumors be treated? It is anticipated in the near future that preclinical/laboratory efforts paired with clinical results obtained from large collaborative studies and clinical trials will likely provide answers to these important questions regarding appropriate patient management. In the near future, the use of combined molecular-histopathological criteria will improve glioma risk stratification, aid in trial design, and ultimately be used to guide therapy for patients with diffuse gliomas.

Acknowledgments

EPS was supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute (SPORE Grant No. P50CA127001, R01CA190121). AO was supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute (Training Grant No. 5T32CA163185).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: none.

References

- 1.Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Liao P, et al. CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2007–2011. Neuro-oncology. 2014;16(Suppl 4):iv1–iv63. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nou223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, et al. WHO Classification of tumors of the central nervous system. Lyon (France): IARC; 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van den Bent MJ. Interobserver variation of the histopathological diagnosis in clinical trials on glioma: a clinician’s perspective. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;120(3):297–304. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0725-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aldape K, Burger PC, Perry A. Clinicopathologic aspects of 1p/19q loss and the diagnosis of oligodendroglioma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131(2):242–51. doi: 10.5858/2007-131-242-CAOQLA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coons SW, Johnson PC, Scheithauer BW, et al. Improving diagnostic accuracy and interobserver concordance in the classification and grading of primary gliomas. Cancer. 1997;79(7):1381–93. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19970401)79:7<1381::aid-cncr16>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kros JM, Gorlia T, Kouwenhoven MC, et al. Panel review of anaplastic oligodendroglioma from European Organization For Research and Treatment of Cancer Trial 26951: assessment of consensus in diagnosis, influence of 1p/19q loss, and correlations with outcome. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2007;66(6):545–51. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000263869.84188.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Louis DN, Perry A, Burger P, et al. International Society of Neuropathology-Haarlem Consensus Guidelines for Nervous System Tumor Classification and Grading. Brain Pathol. 2014 doi: 10.1111/bpa.12171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MacKenzie DJ. A Classification of the Tumours of the Glioma Group on a Histogenetic Basis With a Correlated Study of Prognosis. Can Med Assoc J. 1926;16(7):872. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bailey P, Cushing H. A Classification of the Tumours of the Glioma Group on a Histogenetic Basis With a Correlated Study of Prognosis. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Co; 1926. [Google Scholar]

- 10.NCCN. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Central Nervous System Cancers. Version 2. 2014 [updated 3/11/2014; cited 2014 9/1/2014]. Available from: http://www.nccn.org.

- 11.Bruner JM, Inouye L, Fuller GN, et al. Diagnostic discrepancies and their clinical impact in a neuropathology referral practice. Cancer. 1997;79(4):796–803. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19970215)79:4<796::aid-cncr17>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li A, Walling J, Ahn S, et al. Unsupervised analysis of transcriptomic profiles reveals six glioma subtypes. Cancer Res. 2009;69(5):2091–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gravendeel LA, Kouwenhoven MC, Gevaert O, et al. Intrinsic gene expression profiles of gliomas are a better predictor of survival than histology. Cancer Res. 2009;69(23):9065–72. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vitucci M, Hayes DN, Miller CR. Gene expression profiling of gliomas: merging genomic and histopathological classification for personalised therapy. Br J Cancer. 2011;104(4):545–53. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6606031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gorovets D, Kannan K, Shen R, et al. IDH mutation and neuroglial developmental features define clinically distinct subclasses of lower grade diffuse astrocytic glioma. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(9):2490–501. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yan W, Zhang W, You G, et al. Molecular classification of gliomas based on whole genome gene expression: a systematic report of 225 samples from the Chinese Glioma Cooperative Group. Neuro-oncology. 2012;14(12):1432–40. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nos263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ichimura K. Molecular pathogenesis of IDH mutations in gliomas. Brain Tumor Pathol. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s10014-012-0090-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parsons DW, Jones S, Zhang X, et al. An integrated genomic analysis of human glioblastoma multiforme. Science. 2008;321(5897):1807–12. doi: 10.1126/science.1164382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shibata T, Kokubu A, Miyamoto M, et al. Mutant IDH1 confers an in vivo growth in a melanoma cell line with BRAF mutation. Am J Pathol. 2011;178(3):1395–402. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kang MR, Kim MS, Oh JE, et al. Mutational analysis of IDH1 codon 132 in glioblastomas and other common cancers. Int J Cancer. 2009;125(2):353–5. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boissel N, Nibourel O, Renneville A, et al. Prognostic impact of isocitrate dehydrogenase enzyme isoforms 1 and 2 mutations in acute myeloid leukemia: a study by the Acute Leukemia French Association group. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(23):3717–23. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.2285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Borger DR, Tanabe KK, Fan KC, et al. Frequent mutation of isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH)1 and IDH2 in cholangiocarcinoma identified through broad-based tumor genotyping. Oncologist. 2012;17(1):72–9. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amary MF, Bacsi K, Maggiani F, et al. IDH1 and IDH2 mutations are frequent events in central chondrosarcoma and central and periosteal chondromas but not in other mesenchymal tumours. J Pathol. 2011;224(3):334–43. doi: 10.1002/path.2913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hartman DJ, Binion D, Regueiro M, et al. Isocitrate dehydrogenase-1 is mutated in inflammatory bowel disease-associated intestinal adenocarcinoma with low-grade tubuloglandular histology but not in sporadic intestinal adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38(8):1147–56. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watanabe T, Nobusawa S, Kleihues P, et al. IDH1 mutations are early events in the development of astrocytomas and oligodendrogliomas. Am J Pathol. 2009;174(4):1149–53. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nobusawa S, Watanabe T, Kleihues P, et al. IDH1 mutations as molecular signature and predictive factor of secondary glioblastomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(19):6002–7. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hartmann C, Meyer J, Balss J, et al. Type and frequency of IDH1 and IDH2 mutations are related to astrocytic and oligodendroglial differentiation and age: a study of 1,010 diffuse gliomas. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;118(4):469–74. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0561-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Horbinski C, Kofler J, Kelly LM, et al. Diagnostic use of IDH1/2 mutation analysis in routine clinical testing of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded glioma tissues. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2009;68(12):1319–25. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181c391be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yan H, Parsons DW, Jin G, et al. IDH1 and IDH2 mutations in gliomas. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(8):765–73. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sonoda Y, Kumabe T, Nakamura T, et al. Analysis of IDH1 and IDH2 mutations in Japanese glioma patients. Cancer science. 2009;100(10):1996–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01270.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sanson M, Marie Y, Paris S, et al. Isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 codon 132 mutation is an important prognostic biomarker in gliomas. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(25):4150–4. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.21.9832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hartmann C, Hentschel B, Wick W, et al. Patients with IDH1 wild type anaplastic astrocytomas exhibit worse prognosis than IDH1-mutated glioblastomas, and IDH1 mutation status accounts for the unfavorable prognostic effect of higher age: implications for classification of gliomas. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;120(6):707–18. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0781-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Olar A, Raghunathan A, Albarracin CT, et al. Absence of IDH1-R132H mutation predicts rapid progression of nonenhancing diffuse glioma in older adults. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2011.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu W, Yang H, Liu Y, et al. Oncometabolite 2-hydroxyglutarate is a competitive inhibitor of alpha-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases. Cancer cell. 2011;19(1):17–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chowdhury R, Yeoh KK, Tian YM, et al. The oncometabolite 2-hydroxyglutarate inhibits histone lysine demethylases. EMBO reports. 2011;12(5):463–9. doi: 10.1038/embor.2011.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Figueroa ME, Abdel-Wahab O, Lu C, et al. Leukemic IDH1 and IDH2 mutations result in a hypermethylation phenotype, disrupt TET2 function, and impair hematopoietic differentiation. Cancer cell. 2010;18(6):553–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Turcan S, Rohle D, Goenka A, et al. IDH1 mutation is sufficient to establish the glioma hypermethylator phenotype. Nature. 2012;483(7390):479–83. doi: 10.1038/nature10866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Noushmehr H, Weisenberger DJ, Diefes K, et al. Identification of a CpG island methylator phenotype that defines a distinct subgroup of glioma. Cancer cell. 2010;17(5):510–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mur P, Mollejo M, Ruano Y, et al. Codeletion of 1p and 19q determines distinct gene methylation and expression profiles in IDH-mutated oligodendroglial tumors. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;126(2):277–89. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Juratli TA, Kirsch M, Robel K, et al. IDH mutations as an early and consistent marker in low-grade astrocytomas WHO grade II and their consecutive secondary high-grade gliomas. J Neurooncol. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s11060-012-0844-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lass U, Numann A, von Eckardstein K, et al. Clonal analysis in recurrent astrocytic, oligoastrocytic and oligodendroglial tumors implicates IDH1- mutation as common tumor initiating event. PloS one. 2012;7(7):e41298. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jiao Y, Killela PJ, Reitman ZJ, et al. Frequent ATRX, CIC, FUBP1 and IDH1 mutations refine the classification of malignant gliomas. Oncotarget. 2012;3(7):709–22. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kannan K, Inagaki A, Silber J, et al. Whole-exome sequencing identifies ATRX mutation as a key molecular determinant in lower-grade glioma. Oncotarget. 2012;3(10):1194–203. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Killela PJ, Pirozzi CJ, Reitman ZJ, et al. The genetic landscape of anaplastic astrocytoma. Oncotarget. 2013 doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu XY, Gerges N, Korshunov A, et al. Frequent ATRX mutations and loss of expression in adult diffuse astrocytic tumors carrying IDH1/IDH2 and TP53 mutations. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;124(5):615–25. doi: 10.1007/s00401-012-1031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wiestler B, Capper D, Holland-Letz T, et al. ATRX loss refines the classification of anaplastic gliomas and identifies a subgroup of IDH mutant astrocytic tumors with better prognosis. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;126(3):443–51. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1156-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cai J, Yang P, Zhang C, et al. ATRX mRNA expression combined with IDH1/2 mutational status and Ki-67 expression refines the molecular classification of astrocytic tumors: evidence from the whole transcriptome sequencing of 169 samples samples. Oncotarget. 2014 doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yip S, Butterfield YS, Morozova O, et al. Concurrent CIC mutations, IDH mutations, and 1p/19q loss distinguish oligodendrogliomas from other cancers. J Pathol. 2012;226(1):7–16. doi: 10.1002/path.2995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sahm F, Koelsche C, Meyer J, et al. CIC and FUBP1 mutations in oligodendrogliomas, oligoastrocytomas and astrocytomas. Acta Neuropathol. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s00401-012-0993-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dong ZQ, Pang JC, Tong CY, et al. Clonality of oligoastrocytomas. Hum Pathol. 2002;33(5):528–35. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2002.124784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Qu M, Olofsson T, Sigurdardottir S, et al. Genetically distinct astrocytic and oligodendroglial components in oligoastrocytomas. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;113(2):129–36. doi: 10.1007/s00401-006-0142-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sahm F, Reuss D, Koelsche C, et al. Farewell to oligoastrocytoma: in situ molecular genetics favor classification as either oligodendroglioma or astrocytoma. Acta Neuropathol. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00401-014-1326-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Beiko J, Suki D, Hess KR, et al. IDH1 mutant malignant astrocytomas are more amenable to surgical resection and have a survival benefit associated with maximal surgical resection. Neuro-oncology. 2014;16(1):81–91. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/not159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van den Bent MJ, Dubbink HJ, Marie Y, et al. IDH1 and IDH2 mutations are prognostic but not predictive for outcome in anaplastic oligodendroglial tumors: a report of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Brain Tumor Group. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(5):1597–604. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weller M, Felsberg J, Hartmann C, et al. Molecular predictors of progression-free and overall survival in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma: a prospective translational study of the German Glioma Network. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(34):5743–50. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.0805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wick W, Hartmann C, Engel C, et al. NOA-04 randomized phase III trial of sequential radiochemotherapy of anaplastic glioma with procarbazine, lomustine, and vincristine or temozolomide. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(35):5874–80. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.6497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Houillier C, Wang X, Kaloshi G, et al. IDH1 or IDH2 mutations predict longer survival and response to temozolomide in low-grade gliomas. Neurology. 2010;75(17):1560–6. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181f96282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mukasa A, Takayanagi S, Saito K, et al. Significance of IDH mutations varies with tumor histology, grade, and genetics in Japanese glioma patients. Cancer science. 2012;103(3):587–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.02175.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kim YH, Nobusawa S, Mittelbronn M, et al. Molecular classification of low-grade diffuse gliomas. Am J Pathol. 2010;177(6):2708–14. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Metellus P, Coulibaly B, Colin C, et al. Absence of IDH mutation identifies a novel radiologic and molecular subtype of WHO grade II gliomas with dismal prognosis. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;120(6):719–29. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0777-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ahmadi R, Stockhammer F, Becker N, et al. No prognostic value of IDH1 mutations in a series of 100 WHO grade II astrocytomas. J Neurooncol. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s11060-012-0863-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Okita Y, Narita Y, Miyakita Y, et al. IDH1/2 mutation is a prognostic marker for survival and predicts response to chemotherapy for grade II gliomas concomitantly treated with radiation therapy. Int J Oncol. 2012;41(4):1325–36. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2012.1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hartmann C, Hentschel B, Tatagiba M, et al. Molecular markers in low-grade gliomas: predictive or prognostic? Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(13):4588–99. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-3194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cairncross JG, Wang M, Jenkins RB, et al. Benefit from procarbazine, lomustine, and vincristine in oligodendroglial tumors is associated with mutation of IDH. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(8):783–90. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.3726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Erdem-Eraslan L, Gravendeel LA, de Rooi J, et al. Intrinsic molecular subtypes of glioma are prognostic and predict benefit from adjuvant procarbazine, lomustine, and vincristine chemotherapy in combination with other prognostic factors in anaplastic oligodendroglial brain tumors: a report from EORTC study 26951. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(3):328–36. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.1444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.van den Bent MJ, Gravendeel LA, Gorlia T, et al. A hypermethylated phenotype is a better predictor of survival than MGMT methylation in anaplastic oligodendroglial brain tumors: a report from EORTC study 26951. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(22):7148–55. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Christensen BC, Smith AA, Zheng S, et al. DNA methylation, isocitrate dehydrogenase mutation, and survival in glioma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(2):143–53. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rohle D, Popovici-Muller J, Palaskas N, et al. An inhibitor of mutant IDH1 delays growth and promotes differentiation of glioma cells. Science. 2013;340(6132):626–30. doi: 10.1126/science.1236062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Clinical trials website. [cited 2014 October 22]. Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov.

- 70.Agios pharmaceuticals website. [cited 2014 October 22]. Available from: http://www.agios.com/pipeline-idh.php.

- 71.Olar A, Aldape KD. Biomarkers classification and therapeutic decision-making for malignant gliomas. Current treatment options in oncology. 2012;13(4):417–36. doi: 10.1007/s11864-012-0210-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Reifenberger J, Reifenberger G, Liu L, et al. Molecular genetic analysis of oligodendroglial tumors shows preferential allelic deletions on 19q and 1p. Am J Pathol. 1994;145(5):1175–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Scheie D, Cvancarova M, Mork S, et al. Can morphology predict 1p/19q loss in oligodendroglial tumours? Histopathology. 2008;53(5):578–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2008.03160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cairncross G, Jenkins R. Gliomas with 1p/19q codeletion: a.k.a. oligodendroglioma. Cancer J. 2008;14(6):352–7. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e31818d8178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jenkins RB, Blair H, Ballman KV, et al. A t(1;19)(q10;p10) mediates the combined deletions of 1p and 19q and predicts a better prognosis of patients with oligodendroglioma. Cancer Res. 2006;66(20):9852–61. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Griffin CA, Burger P, Morsberger L, et al. Identification of der(1;19)(q10;p10) in five oligodendrogliomas suggests mechanism of concurrent 1p and 19q loss. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2006;65(10):988–94. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000235122.98052.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Labussiere M, Di Stefano AL, Gleize V, et al. TERT promoter mutations in gliomas, genetic associations and clinico-pathological correlations. Br J Cancer. 2014 doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Frenel JS, Leux C, Loussouarn D, et al. Combining two biomarkers, IDH1/2 mutations and 1p/19q codeletion, to stratify anaplastic oligodendroglioma in three groups: a single-center experience. J Neurooncol. 2013;114(1):85–91. doi: 10.1007/s11060-013-1152-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cairncross G, Berkey B, Shaw E, et al. Phase III trial of chemotherapy plus radiotherapy compared with radiotherapy alone for pure and mixed anaplastic oligodendroglioma: Intergroup Radiation Therapy Oncology Group Trial 9402. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(18):2707–14. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.3414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cairncross JG, Ueki K, Zlatescu MC, et al. Specific genetic predictors of chemotherapeutic response and survival in patients with anaplastic oligodendrogliomas. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90(19):1473–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.19.1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cairncross G, Wang M, Shaw E, et al. Phase III trial of chemoradiotherapy for anaplastic oligodendroglioma: long-term results of RTOG 9402. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(3):337–43. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.2674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.van den Bent MJ, Carpentier AF, Brandes AA, et al. Adjuvant procarbazine, lomustine, and vincristine improves progression-free survival but not overall survival in newly diagnosed anaplastic oligodendrogliomas and oligoastrocytomas: a randomized European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(18):2715–22. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.6078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.van den Bent MJ, Brandes AA, Taphoorn MJ, et al. Adjuvant procarbazine, lomustine, and vincristine chemotherapy in newly diagnosed anaplastic oligodendroglioma: long-term follow-up of EORTC brain tumor group study 26951. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(3):344–50. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kaloshi G, Benouaich-Amiel A, Diakite F, et al. Temozolomide for low-grade gliomas: predictive impact of 1p/19q loss on response and outcome. Neurology. 2007;68(21):1831–6. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000262034.26310.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kesari S, Schiff D, Drappatz J, et al. Phase II study of protracted daily temozolomide for low-grade gliomas in adults. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(1):330–7. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tosoni A, Franceschi E, Ermani M, et al. Temozolomide three weeks on and one week off as first line therapy for patients with recurrent or progressive low grade gliomas. J Neurooncol. 2008;89(2):179–85. doi: 10.1007/s11060-008-9600-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chinot OL, Honore S, Dufour H, et al. Safety and efficacy of temozolomide in patients with recurrent anaplastic oligodendrogliomas after standard radiotherapy and chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(9):2449–55. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.9.2449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hoang-Xuan K, Capelle L, Kujas M, et al. Temozolomide as initial treatment for adults with low-grade oligodendrogliomas or oligoastrocytomas and correlation with chromosome 1p deletions. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(15):3133–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.10.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.van den Bent MJ, Taphoorn MJ, Brandes AA, et al. Phase II study of first-line chemotherapy with temozolomide in recurrent oligodendroglial tumors: the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Brain Tumor Group Study 26971. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(13):2525–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lassman AB, Iwamoto FM, Cloughesy TF, et al. International retrospective study of over 1000 adults with anaplastic oligodendroglial tumors. Neuro-oncology. 2011;13(6):649–59. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nor040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Jansen M, Yip S, Louis DN. Molecular pathology in adult gliomas: diagnostic, prognostic, and predictive markers. Lancet neurology. 2010;9(7):717–26. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70105-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yip S, Iafrate AJ, Louis DN. Molecular diagnostic testing in malignant gliomas: a practical update on predictive markers. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2008;67(1):1–15. doi: 10.1097/nen.0b013e31815f65fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Aubert G, Lansdorp PM. Telomeres and aging. Physiol Rev. 2008;88(2):557–79. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00026.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bryan TM, Englezou A, Dalla-Pozza L, et al. Evidence for an alternative mechanism for maintaining telomere length in human tumors and tumor-derived cell lines. Nat Med. 1997;3(11):1271–4. doi: 10.1038/nm1197-1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Heaphy CM, Subhawong AP, Hong SM, et al. Prevalence of the alternative lengthening of telomeres telomere maintenance mechanism in human cancer subtypes. Am J Pathol. 2011;179(4):1608–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Drane P, Ouararhni K, Depaux A, et al. The death-associated protein DAXX is a novel histone chaperone involved in the replication-independent deposition of H3.3. Genes Dev. 2010;24(12):1253–65. doi: 10.1101/gad.566910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lewis PW, Elsaesser SJ, Noh KM, et al. Daxx is an H3.3-specific histone chaperone and cooperates with ATRX in replication-independent chromatin assembly at telomeres. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(32):14075–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008850107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Goldberg AD, Banaszynski LA, Noh KM, et al. Distinct factors control histone variant H3.3 localization at specific genomic regions. Cell. 2010;140(5):678–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lovejoy CA, Li W, Reisenweber S, et al. Loss of ATRX, genome instability, and an altered DNA damage response are hallmarks of the alternative lengthening of telomeres pathway. PLoS genetics. 2012;8(7):e1002772. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bower K, Napier CE, Cole SL, et al. Loss of wild-type ATRX expression in somatic cell hybrids segregates with activation of Alternative Lengthening of Telomeres. PloS one. 2012;7(11):e50062. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Heaphy CM, de Wilde RF, Jiao Y, et al. Altered telomeres in tumors with ATRX and DAXX mutations. Science. 2011;333(6041):425. doi: 10.1126/science.1207313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Abedalthagafi M, Phillips JJ, Kim GE, et al. The alternative lengthening of telomere phenotype is significantly associated with loss of ATRX expression in high-grade pediatric and adult astrocytomas: a multi-institutional study of 214 astrocytomas. Mod Pathol. 2013;26(11):1425–32. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2013.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Killela PJ, Reitman ZJ, Jiao Y, et al. TERT promoter mutations occur frequently in gliomas and a subset of tumors derived from cells with low rates of self-renewal. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(15):6021–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1303607110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Theimer CA, Feigon J. Structure and function of telomerase RNA. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2006;16(3):307–18. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Weinrich SL, Pruzan R, Ma L, et al. Reconstitution of human telomerase with the template RNA component hTR and the catalytic protein subunit hTRT. Nat Genet. 1997;17(4):498–502. doi: 10.1038/ng1297-498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Arita H, Narita Y, Fukushima S, et al. Upregulating mutations in the TERT promoter commonly occur in adult malignant gliomas and are strongly associated with total 1p19q loss. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;126(2):267–76. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1141-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Huang FW, Hodis E, Xu MJ, et al. Highly recurrent TERT promoter mutations in human melanoma. Science. 2013;339(6122):957–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1229259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Rachakonda PS, Hosen I, de Verdier PJ, et al. TERT promoter mutations in bladder cancer affect patient survival and disease recurrence through modification by a common polymorphism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(43):17426–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1310522110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Horn S, Figl A, Rachakonda PS, et al. TERT promoter mutations in familial and sporadic melanoma. Science. 2013;339(6122):959–61. doi: 10.1126/science.1230062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Nault JC, Mallet M, Pilati C, et al. High frequency of telomerase reverse-transcriptase promoter somatic mutations in hepatocellular carcinoma and preneoplastic lesions. Nature communications. 2013;4:2218. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Dissanayake K, Toth R, Blakey J, et al. ERK/p90(RSK)/14-3-3 signalling has an impact on expression of PEA3 Ets transcription factors via the transcriptional repressor capicua. Biochem J. 2011;433(3):515–25. doi: 10.1042/BJ20101562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Chen C, Han S, Meng L, et al. TERT promoter mutations lead to high transcriptional activity under hypoxia and temozolomide treatment and predict poor prognosis in gliomas. PloS one. 2014;9(6):e100297. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Killela PJ, Pirozzi CJ, Healy P, et al. Mutations in IDH1, IDH2, and in the TERT promoter define clinically distinct subgroups of adult malignant gliomas. Oncotarget. 2014;5(6):1515–25. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Chan AK, Yao Y, Zhang Z, et al. TERT promoter mutations contribute to subset prognostication of lower-grade gliomas. Mod Pathol. 2014 doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2014.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.van Thuijl HF, Scheinin I, Sie D, et al. Spatial and temporal evolution of distal 10q deletion, a prognostically unfavorable event in diffuse low-grade gliomas. Genome biology. 2014;15(9):471. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0471-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Houillier C, Mokhtari K, Carpentier C, et al. Chromosome 9p and 10q losses predict unfavorable outcome in low-grade gliomas. Neuro-oncology. 2010;12(1):2–6. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nop002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Bissola L, Eoli M, Pollo B, et al. Association of chromosome 10 losses and negative prognosis in oligoastrocytomas. Ann Neurol. 2002;52(6):842–5. doi: 10.1002/ana.10405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Cancer, Genome, Atlas, et al. Comprehensive genomic characterization defines human glioblastoma genes and core pathways. Nature. 2008;455(7216):1061–8. doi: 10.1038/nature07385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Olar A, Aldape KD. Using the molecular classification of glioblastoma to inform personalized treatment. J Pathol. 2014;232(2):165–77. doi: 10.1002/path.4282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Ohgaki H, Kleihues P. The definition of primary and secondary glioblastoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(4):764–72. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Chin L, Hahn WC, Getz G, et al. Making sense of cancer genomic data. Genes Dev. 2011;25(6):534–55. doi: 10.1101/gad.2017311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Shete S, Hosking FJ, Robertson LB, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies five susceptibility loci for glioma. Nat Genet. 2009;41(8):899–904. doi: 10.1038/ng.407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Chen H, Chen Y, Zhao Y, et al. Association of sequence variants on chromosomes 20, 11, and 5 (20q13.33, 11q23.3, and 5p15.33) with glioma susceptibility in a Chinese population. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(8):915–22. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Egan KM, Thompson RC, Nabors LB, et al. Cancer susceptibility variants and the risk of adult glioma in a US case-control study. J Neurooncol. 2011;104(2):535–42. doi: 10.1007/s11060-010-0506-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Rajaraman P, Melin BS, Wang Z, et al. Genome-wide association study of glioma and meta-analysis. Hum Genet. 2012;131(12):1877–88. doi: 10.1007/s00439-012-1212-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Melin B, Dahlin AM, Andersson U, et al. Known glioma risk loci are associated with glioma with a family history of brain tumours -- a case-control gene association study. Int J Cancer. 2013;132(10):2464–8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Di Stefano AL, Enciso-Mora V, Marie Y, et al. Association between glioma susceptibility loci and tumour pathology defines specific molecular etiologies. Neuro-oncology. 2013;15(5):542–7. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nos284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Jenkins RB, Wrensch MR, Johnson D, et al. Distinct germ line polymorphisms underlie glioma morphologic heterogeneity. Cancer genetics. 2011;204(1):13–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Jenkins RB, Xiao Y, Sicotte H, et al. A low-frequency variant at 8q24.21 is strongly associated with risk of oligodendroglial tumors and astrocytomas with IDH1 or IDH2 mutation. Nat Genet. 2012;44(10):1122–5. doi: 10.1038/ng.2388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Walsh KM, Codd V, Smirnov IV, et al. Variants near TERT and TERC influencing telomere length are associated with high-grade glioma risk. Nat Genet. 2014;46(7):731–5. doi: 10.1038/ng.3004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Stacey SN, Sulem P, Jonasdottir A, et al. A germline variant in the TP53 polyadenylation signal confers cancer susceptibility. Nat Genet. 2011;43(11):1098–103. doi: 10.1038/ng.926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Rice T, Zheng S, Decker PA, et al. Inherited variant on chromosome 11q23 increases susceptibility to IDH-mutated but not IDH-normal gliomas regardless of grade or histology. Neuro-oncology. 2013;15(5):535–41. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nos324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Hawkins C, Walker E, Mohamed N, et al. BRAF-KIAA1549 fusion predicts better clinical outcome in pediatric low-grade astrocytoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(14):4790–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Hasselblatt M, Riesmeier B, Lechtape B, et al. BRAF-KIAA1549 fusion transcripts are less frequent in pilocytic astrocytomas diagnosed in adults. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2011;37(7):803–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2011.01193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Jacob K, Albrecht S, Sollier C, et al. Duplication of 7q34 is specific to juvenile pilocytic astrocytomas and a hallmark of cerebellar and optic pathway tumours. Br J Cancer. 2009;101(4):722–33. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Lin A, Rodriguez FJ, Karajannis MA, et al. BRAF alterations in primary glial and glioneuronal neoplasms of the central nervous system with identification of 2 novel KIAA1549:BRAF fusion variants. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2012;71(1):66–72. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e31823f2cb0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Schindler G, Capper D, Meyer J, et al. Analysis of BRAF V600E mutation in 1,320 nervous system tumors reveals high mutation frequencies in pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma, ganglioglioma and extra-cerebellar pilocytic astrocytoma. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;121(3):397–405. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0802-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Dias-Santagata D, Lam Q, Vernovsky K, et al. BRAF V600E mutations are common in pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma: diagnostic and therapeutic implications. PloS one. 2011;6(3):e17948. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Koelsche C, Sahm F, Wohrer A, et al. BRAF-mutated pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma is associated with temporal location, reticulin fiber deposition and CD34 expression. Brain Pathol. 2014;24(3):221–9. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Parker M, Mohankumar KM, Punchihewa C, et al. C11orf95-RELA fusions drive oncogenic NF-kappaB signalling in ependymoma. Nature. 2014;506(7489):451–5. doi: 10.1038/nature13109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Pietsch T, Wohlers I, Goschzik T, et al. Supratentorial ependymomas of childhood carry C11orf95-RELA fusions leading to pathological activation of the NF-kappaB signaling pathway. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;127(4):609–11. doi: 10.1007/s00401-014-1264-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Witt H, Mack SC, Ryzhova M, et al. Delineation of two clinically and molecularly distinct subgroups of posterior fossa ependymoma. Cancer cell. 2011;20(2):143–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Wani K, Armstrong TS, Vera-Bolanos E, et al. A prognostic gene expression signature in infratentorial ependymoma. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;123(5):727–38. doi: 10.1007/s00401-012-0941-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Hoffman LM, Donson AM, Nakachi I, et al. Molecular sub-group-specific immunophenotypic changes are associated with outcome in recurrent posterior fossa ependymoma. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;127(5):731–45. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1212-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]