Abstract

Visual deficits are commonly seen in patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD), but postmortem histology has not found substantial damage in visual cortex regions, leading to the hypothesis that the visual pathway, from eye to the brain, may be damaged in AD. Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) has been used to characterize white matter abnormalities. However, there is a lack of data examining the optic nerves and tracts in patients with AD. In this study, we used DTI to analyze the visual pathway in healthy controls, patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and AD using scans provided by the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI). We found significant increases in the total diffusivity and radial diffusivity and reductions in fractional anisotropy in optic nerves among AD patients. Similar but less extensive changes in these metrics were seen in MCI patients as compared to controls. The differences in DTI metrics between groups mirrored changes in the splenium of the corpus callosum, which has commonly been shown to exhibit white matter damage during AD and MCI. Our findings indicate that white matter damage extends to the visual system, and may help explain the visual deficits experienced by AD patients.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, diffusion tensor imaging, human, mild cognitive impairment, optic nerve, optic tract, visual pathway

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disease characterized clinically by memory loss and cognitive impairment and pathologically by amyloid plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, and brain volume shrinkage [1]. In vivo neuroimaging using positron emission tomography (PET) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are able to reveal amyloid plaques and brain atrophy, which both occur mostly within gray matter regions of AD patients [2]. In white matter though, abnormal MRI signals have been found in patients with AD [3–5] as well as patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) [6–8]. Evidence now indicates that white matter damage coincides with early pathophysiological events in gray matter. This damage may play a critical role in the neurofunctional declines seen in patients with AD.

Among white matter tracts in the brain, the visual pathway is unique in structure. Neurons that compose the optic nerve and tract have their cell bodies (retinal ganglion cells, RGCs) outside the brain within the retina [9]. Despite the relatively isolated RGC location, the visual system like other sensory systems, declines during AD [10]. Many AD patients suffer from complex visual disturbances and have worse color vision and contrast sensitivity when compared to similarly aged controls [11]. Additionally, the severity of these visual deficits is associated with lower clinical dementia rating [10]. Despite impaired visual ability, the visual cortex is relatively protected from atrophy and disease pathology in AD [10, 12–14], leading to the hypothesis that the visual pathway, from eye to the brain, may be damaged in AD.

While abnormal white matter has been found in various brain regions in AD, there is a lack of imaging data for the visual pathway. Direct evaluation of the visual pathway white matter can be accomplished through the use of diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) [15–17]. This novel MRI modality measures the diffusion of water molecules and is sensitive to microstructural changes in live tissue. When applied to the brain, DTI shows white matter as areas with high diffusion anisotropy, due to the organized parallel fiber bundles, in contrast to low anisotropy within the gray matter and ventricles. Disruptions in white matter structure usually lead to a reduction in diffusion anisotropy, as quantified by fractional anisotropy (FA) and relative anisotropy (RA) [15–17]. In addition, DTI-derived axial diffusivity (λII) and radial diffusivity (λ⊥) quantify water diffusion parallel and perpendicular to fiber tracts, respectively. Specific white matter pathologies, such as demyelination and axonal degeneration, have been shown to change λ⊥ and λII, respectively [15,18–22].

DTI studies have previously demonstrated that white matter damage occurs in distinct regions during AD and MCI [5, 6,23]. However, to the best of our knowledge, there is no published study using DTI to examine the visual pathway in AD. In this study we worked on image data provided by the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI). DTI parameters were measured in the optic nerves and tracts of ADNI participants. We also measured DTI changes within the splenium of the corpus callosum, in order to reference our findings against a site commonly seen to exhibit white matter damage during MCI and AD [5, 24]. The findings of this study are of potential relevance to early diagnostic criteria and to gain a greater understanding of the underlying visual problems in AD.

METHODS

Data used in the preparation of this article were obtained from the ADNI database (http://adni.loni.usc.edu). The ADNI was launched in 2003 by the National Institute on Aging (NIA), the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB), the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), private pharmaceutical companies, and non-profit organizations, as a $60 million, 5-year public-private partnership. The primary goal of ADNI has been to test whether serial MRI, PET, other biological markers, and clinical and neuropsychological assessment can be combined to measure the progression of MCI and early AD. Determination of sensitive and specific markers of very early AD progression is intended to aid researchers and clinicians to develop new treatments and monitor their effectiveness, as well as lessen the time and cost of clinical trials.

The Principal Investigator of this initiative is Michael W. Weiner, MD, VA Medical Center and University of California–San Francisco. ADNI is the result of efforts of many co-investigators from a broad range of academic institutions and private corporations, and subjects have been recruited from over 50 sites across the U.S. and Canada. The initial goal of ADNI was to recruit 800 subjects but ADNI has been followed by ADNI-GO and ADNI-2. To date these three protocols have recruited over 1,500 adults, ages 55 to 90, to participate in the research, consisting of cognitively normal older individuals, people with early or late MCI, and people with early AD. The follow up duration of each group is specified in the protocols for ADNI-1, ADNI-2, and ADNI-GO. Subjects originally recruited for ADNI-1 and ADNI-GO had the option to be followed in ADNI-2. For up-to-date information, see http://www.adni-info.org.

Thirty subjects were selected in each cohort made of healthy control, MCI, and AD-classified patients. Within each cohort, subjects were evenly split by gender and were selected based upon similar characteristics between groups (Table 1). Subjects were excluded from selection if they had been diagnosed with any variant of glaucoma, macular degeneration, or complained of blurry vision. Thirty patients per group maximized the use of the ADNI DTI data, while maintaining neutral gender balance. Selection of greater numbers would have necessarily resulted in skewed male/female ratio. Each patient underwent MRI scans on a 3-Tesla GE Medical Systems scanner. For our analysis, we used two sets of scans collected, an anatomical T1-weighted spoiled gradient echo (256 × 256 matrix; 1.2 × 1 × 1 mm3 voxel size; TI = 400 ms; TR = 6.984 ms; TE = 2.848 ms; flip angle= 11°) along with a DTI scan. The DTI includes a group of diffusion-weighted images (256 × 256 matrix; 1.367 × 1.367 × 2.7 mm3 voxel size; 35 mm field of view) comprised of 5 B0 images and 41 diffusion-sensitized images (B = 1000 s/mm2).

Table 1.

Group demographic information

| Control | MCI | AD | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 30 | 30 | 29 | |

| Gender (Male/Female) | 15/15 | 15/15 | 15/14 | |

| Age (y) | 70.9 (5.4) | 71.1 (5.9) | 72.1 (7.2) | 0.727 |

| Education (y) | 16.7 (2.7) | 15.8 (2.6) | 16 (2.5) | 0.328 |

| Body Mass Index | 28 (4.3) | 28 (5.5) | 25.9 (5) | 0.184 |

| Mini-Mental State Exam | 28.7 (1.5) | 27.3 (1.9) | 23.5 (1.7) | <0.0001 |

| p value versus Control | 0.0016 | <0.0001 | ||

| p value versus MCI | <0.0001 | |||

| Mean (SD) |

Bold numbers indicate significant p values (p < 0.05). Group comparisons made with a non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis analysis of variance (ANOVA), pair-wise comparisons made using post-hoc Mann-Whitney U test.

Image processing

MRI scans were downloaded from the ADNI database. Diffusion-weighted scans were processed within DTIPrep to eliminate artifacts from head motion, eddy currents, and gradient distortions [25]. Processed diffusion-weighted images passing DTIPrep quality control were then loaded into 3D slicer (http://www.slicer.org). The B0 images from the diffusion-weighted scan were registered to a stationary T1 scan for anatomical reference. The registration protocol utilized the Brainsfit Module and relied upon rigid, affline, and Bspline transforms. A deformation field from these transforms was then used to register DTI maps. All images were carefully checked to ensure tight correspondence between the T1 and the resulting DTI. Maps for five DTI indices, including FA, trace diffusion (TR), axial (λII), radial (λ⊥) diffusivity and eigen3 (λ3) were generated using 3D slicer [17, 19].

Analysis methods

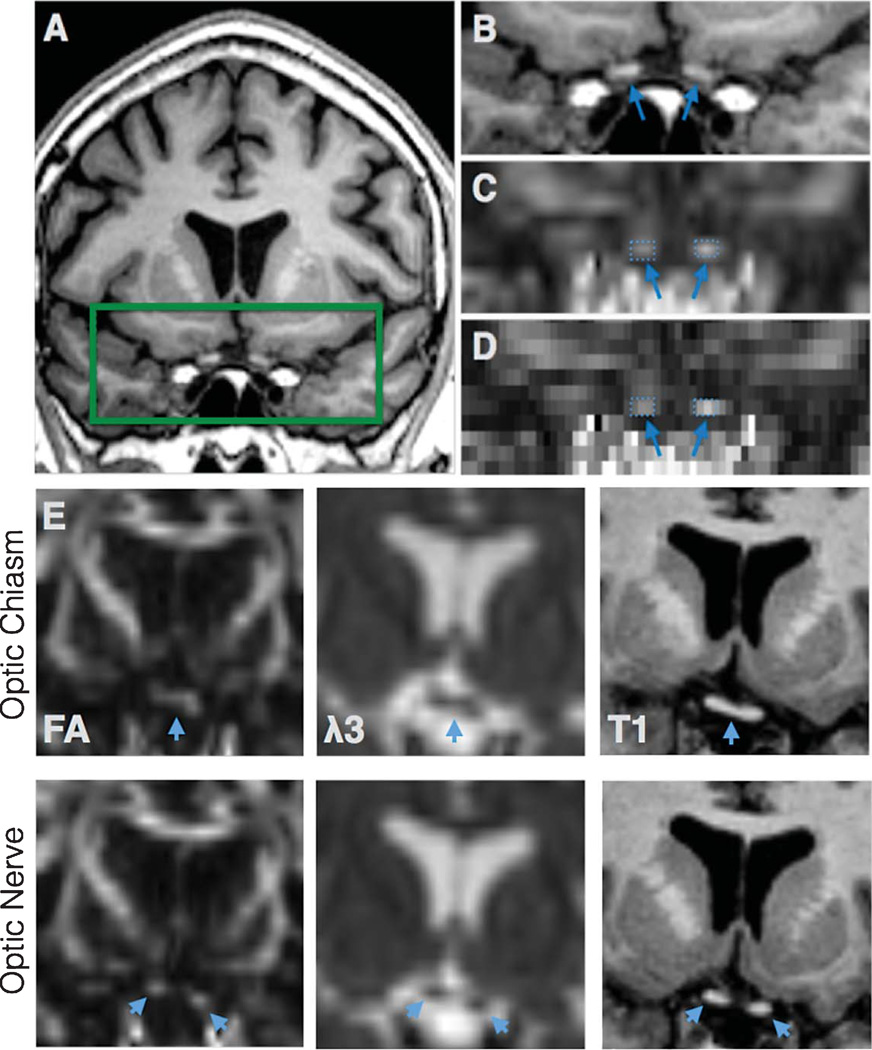

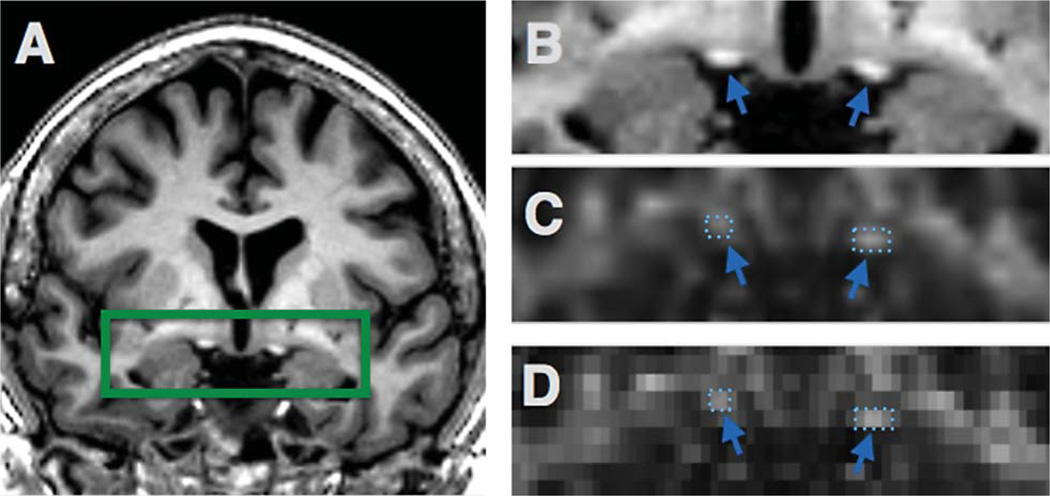

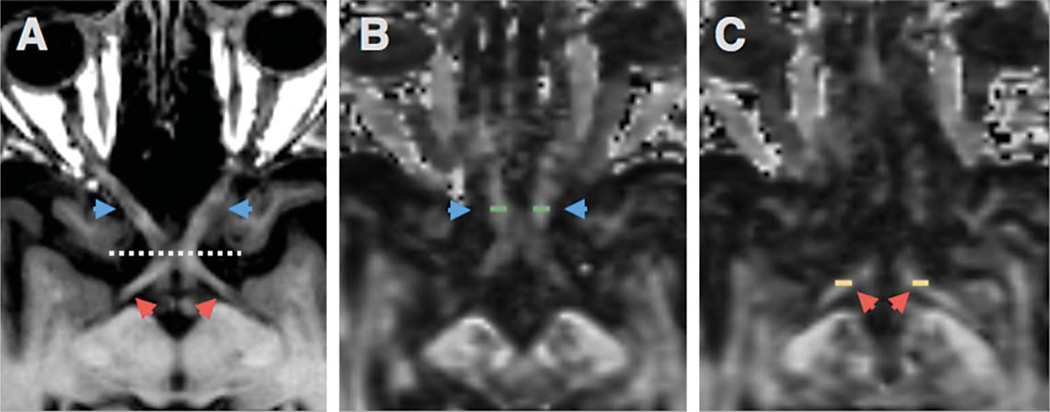

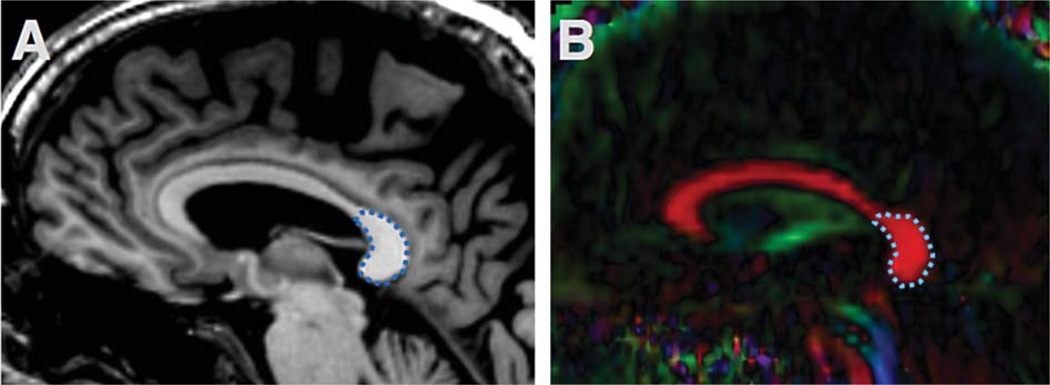

Regions of interest (ROI) were selected from optic nerves (Fig. 1), optic tracts (Figs. 2 and 3), and the splenium of corpus callosum (Fig. 4). The optic nerve approximately 3 mm rostral to the optic chiasm was identified and selected manually using the T1 reference scan in conjunction with the FA and Minimum Eigen (λ3) map (Figs. 1 and 3). This section could be precisely identified in each subject by following the optic chiasm (caudal to rostral) until it split into two optic nerves (Fig. 1E). The optic nerve ROI was selected in the first section showing two separate optic nerves, rostral to the optic chaism. To minimize partial volume effects, ROIs were selected in one coronal slice which showed the transected optic nerve clearly as two round regions (Fig. 1). Using a similar method, the optic tract approximately 14 mm caudal to the optic chiasm was identified as two round areas in coronal section and selected using the T1 scan in combination with the registered FA map (Figs. 2 and 3). These ROIs were chosen based upon their ability to be selected easily and unambiguously. All ROIs for each section are included in the supplementary figures. The splenium was selected using the DTI within 5 midsagittal sections and identified using morphology as the most caudal, enlarged portion of the corpus callosum (Fig. 4). Any scan showing distortion of the optic nerve or tract around the ROI was excluded from analysis. Among the 89 subjects, six optic nerves were excluded from analysis (2 control, 2 MCI, 2 AD), and one optic tract (AD). No corpus callosum scans were excluded.

Fig. 1.

The optic nerve ROI. T1 anatomical scan shows the region of the optic nerve ROI in coronal section (A). The rectangle was expanded (B) with corresponding FA map (with interpolation, C and without, D). Optic nerves identified with arrows, with selected ROIs (comprising 2–3 voxels on each side). Upper row shows the optic chiasm (arrows) in FA, λ3 and T1 section before it splits into two optic nerves in the next slice (lower row) (E).

Fig. 2.

Optic tract ROI. T1 anatomical scan shows the region of the optic tract (A). The green rectangle was expanded in (B), with the registered FA map (C,D) where the optic tract is identified with arrows and selected ROIs.

Fig. 3.

ON and OT ROIs in axial section. Axial T1 section showing the optic nerve (blue arrows) and optic tract (red arrows) separated by the optic chiasm (dotted line) (A). FA map showing the position of the ON ROI (green rectangles) in axial section (B). OT ROI shown on FA map in axial section (C).

Fig. 4.

Splenium of the corpus callosum ROI. The corpus callosum is easily identified with a saggital Tl image (A) and DTI (B). The splenium ROI is outlined in blue dash line.

Statistical analysis

Group comparisons of personal characteristics (age, education, body mass index) and neuropsychological data (MMSE scores) were made by non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis analysis of variance (ANOVA), with post-hoc Mann-Whitney U test. Within each group, collected DTI data was tested for normality using the D’Agostino-Pearson omnibus normality test. The test did not show any significant deviations from normality within the groups. Comparisons of DTI measures (TR, FA, λ⊥, λII) within each ROI were made using a one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test to examine differences between the three patient groups. For each analysis, p < 0.05 was considered significant. Statistics were performed using Prism Graphpad (San Diego, CA).

RESULTS

The MCI, AD, and control groups did not significantly differ in terms of their age, gender bias, years of education, or body mass index. They did significantly differ in terms of their MMSE score, reflecting reduced cognitive ability of the MCI and AD groups compared with controls, as well as a significant difference between MCI and AD patients (Table 1).

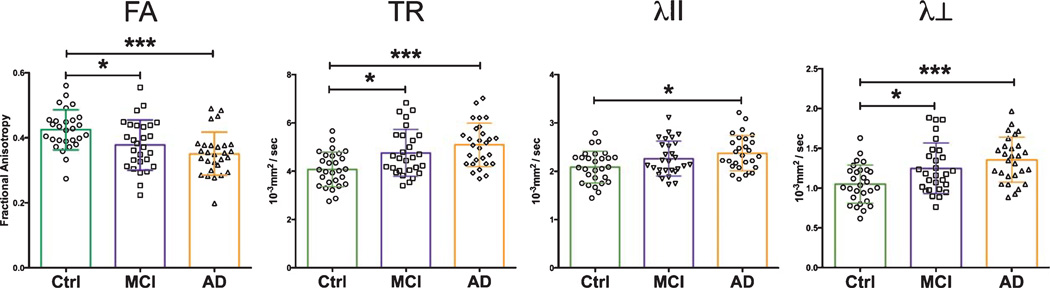

DTI in optic nerves

Analysis of sections from the optic nerves of AD, MCI, and control patients revealed key differences in several DTI indices (Table 2). The AD and MCI patient cohorts showed significant (p < 0.05) increases in TR and λ⊥ when compared with the control group (Fig. 5). The AD group mean TR value was 24.4% higher, while MCI patients’ rose 16.6%. Relative to controls, AD cohort λ⊥ increased by 29.5%, while it rose by 19% among the MCI cohort. FA values among cognitively impaired patients were significantly reduced, 11.6% among MCI patients and 18.6% in the AD cohort. Measures of λII increased among MCI (8.6%) and AD (13.9%) patients relative to controls, but only met statistical significance in the AD patient group.

Table 2.

DTI measures from Control, MCI, and AD cohorts

| Control Mean (SD) |

MCI Mean (SD) |

AD Mean (SD) |

One-way ANOVA p value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ON FA | 0.43 (0.06) | 0.38 (0.08) | 0.35 (0.07) | 0.0005 |

| ON TR | 4.09 (0.72) | 4.77 (0.96) | 5.09 (0.90) | 0.0001 |

| ON λII | 2.09 (0.33) | 2.27 (0.36) | 2.38 (0.36) | 0.0112 |

| ON λ⊥ | 1.05 (0.24) | 1.25 (0.32) | 1.36 (0.28) | 0.0004 |

| OT FA | 0.49 (0.09) | 0.46 (0.09) | 0.45 (0.09) | 0.0946 |

| OT TR | 4.07 (0.97) | 4.31 (0.97) | 4.57 (1.34) | 0.2288 |

| OT λII | 2.16(0.41) | 2.20 (0.36) | 2.31 (0.53) | 0.4169 |

| OT λ⊥ | 0.95 (0.29) | 1.06 (0.31) | 1.13 (0.41) | 0.1449 |

| CC FA | 0.77 (0.03) | 0.73 (0.14) | 0.73 (0.05) | 0.0001 |

| CC TR | 2.42 (0.15) | 2.56 (0.44) | 2.63 (0.27) | 0.0065 |

| CC λII | 1.75 (0.10) | 1.74 (0.28) | 1.78 (0.12) | 0.4128 |

| CC λ⊥ | 0.34 (0.05) | 0.41 (0.10) | 0.43 (0.09) | <0.0001 |

ON, optic nerve; OT, optic tract; CC, splenium of the corpus callosum. TR, λII, λ⊥ measures in units of 10−3 mm2/s. Bold numbers indicate significant p values.

Fig. 5.

Optic nerve DTI measures. Optic nerves from AD and MCI patients show significant changes in FA, TR, and λ⊥ versus healthy controls. Data-points shown with overlapping mean ± SD. Statistical tests between groups performed with Tukey’s post-hoc test after one-way ANOVA (*p < 0.05; *** p < 0.0001).

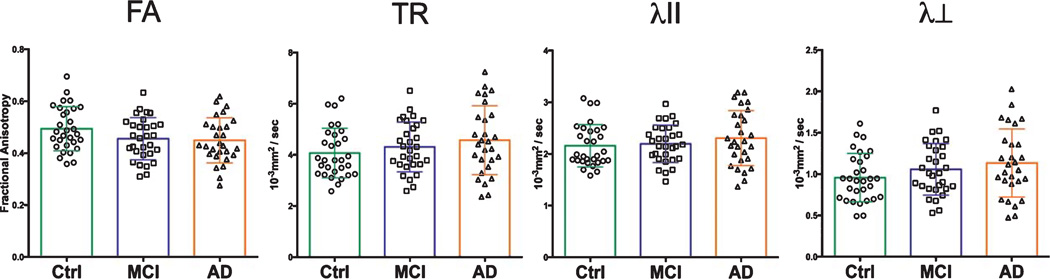

DTI in optic tracts

Within the optic tract, DTI changes among AD and MCI patients (relative to controls) followed similar patterns to that of the optic nerve (Table 2). MCI and AD patient cohorts showed consistent reductions in FA, and increases in TR, λII, and λ⊥ Among AD patients, mean TR, λII, and λ⊥ were increased by 12.3%, 6.9%, and 18.9%, respectively (Fig. 6). Mean FA was reduced by 8.2%, relative to controls. MCI patient group differences followed similar trends, with increases in TR (5.9%) and λ⊥ (11.6%). Mean FA among MCI patients was reduced by 6.1%. These changes between groups, while trending in similar directions as the AD group, did not meet statistical significance either via ANOVA, or with use of Tukey’s post-hoc tests.

Fig. 6.

Optic tract DTI measures. Optic tract measures showed trends toward reductions in FA among AD patients, as well as increases in TR and λ⊥

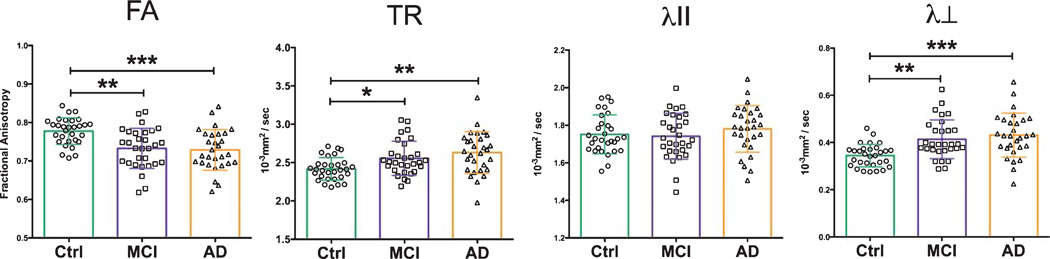

DTI in corpus callosum

The splenium of the corpus callosum exhibited DTI changes consistent with what was seen in the visual white matter tracts (Table 2). The splenium in our MCI and AD patient cohorts had significant changes in FA, TR and λ⊥ values versus controls (Fig. 7). Mean FA was reduced in these cohorts by 5.2% in MCI patients (p < 0.01) and 5.2% in AD patients (p < 0.001). TR increased among MCI (5.8%, p < 0.05) and AD (8.7%, p < 0.01) patients as well as measures of λ⊥, which increased by 20.6% in MCI (p < 0.01) and 26.5% (p < 0.001) in AD cohorts. The λII measure marginally increased in AD (1.7% increase) and decreased in MCI (0.6%) without any significant change.

Fig. 7.

Splenium of the corpus callosum DTI measures. DTI measures of the splenium show significant differences in diffusional metrics between control, MCI and AD patients cohorts. Patients with AD and MCI have significant increases in TR and λ⊥, and significant reductions in FA versus healthy controls. Statistical tests between groups performed with Tukey’s post-hoc test after one-way ANOVA (*p < 0.05; ** p <0.01; *** p < 0.001).

DISCUSSION

Our study demonstrates that the visual pathway from eye to the brain is affected during the degeneration process in AD and MCI. Increases in TR and λ⊥ and reductions in FA were found within optic nerves among the AD and MCI cohort compared to a similarly aged, gender-balanced control group. Similar, but less extensive, changes were also seen in the optic tract. These diffusional differences in the visual pathway mirror those in the splenium of the corpus callosum, which has been shown in previous studies to be affected during MCI and AD [5]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to show DTI-detected visual pathway injury in AD and MCI patients. Our findings raise the possibility that damage within the visual white matter tracts may be responsible for visual deficits experienced by AD patients.

Results from several studies have shown AD patients perform poorly on low-level measures of visual ability. These deficits have been demonstrated in tests of stereo acuity, color discrimination, contrast sensitivity, visual processing speed, and visual field coverage [11, 26]. AD patients also have a significantly slower pupillary light reflex as compared to controls [27]. Evidence from these studies showed clearly that visual problems are widespread among AD patients and in some cases, correlate with the severity of dementia [28].

Atrophy or dysfunction within the primary visual cortex, while apparent in a small (∼5%) subset of patients [29], may not fully account for the general visual problems experienced by AD patients. Evidence from in vivo imaging and postmortem studies largely suggest that the visual cortex is not heavily impacted during AD or MCI. MRI studies measuring cortical thinning show relative sparing of the visual cortex grey matter from atrophy during MCI and early onset AD [12, 13]. Additionally, primary visual cortex glucose metabolism activity is relatively preserved in AD subjects (in contrast to adjacent cortical areas) as measured by [18F] flurodeoxyglucose PET [30]. These data correspond well with autopsy studies showing the visual cortex to be relatively spared by neurofibrillary tangles and amyloid-β plaque pathology [10, 14]. Visual deficits among AD patients are not easily explained by visual cortex dysfunction, which may hint at other mechanisms that contribute to the general visual problems that occur during AD.

Several pieces of evidence from histology studies, as well as recent in vivo imaging data using optical coherence tomography (OCT), may help account for visual deficits in AD. Studies examining retinas from postmortem samples have found that RGC loss occurs during the course of AD, and may be a feature of MCI. A study by Blanks et al. found a 25% total reduction among neurons in the ganglion cell layer in AD, compared to controls [31]. An additional histological study by Hinton et al. found similar reductions in RGCs among AD patient retinas [32]. The use of OCT has made non-invasive measures of the ganglion cell layer in the retina possible [33]. Several studies have utilized this technique to quantify the retinal ganglion nerve fiber layer (RNFL) thickness in patients with AD and MCI. Studies by Parisi et al. and Paquet et al. have used this technique and independently shown reductions in RNFL thickness among AD patients as compared to similarly aged controls [34, 35]. Interestingly, data from Paquet and colleagues demonstrated cognitive decline-dependent reductions in RNFL thickness, with MCI, AD, and severe AD all showing progressively greater degrees of thinning [34]. These lines of evidence demonstrate that cell bodies of optic nerves are lost during AD and MCI, and imply that the degree of loss may correspond to disease severity. Furthermore, loss of cell bodies may be concomitant with a loss of axons and associated myelin sheaths within the white matter of the optic nerve and tract.

Use of DTI allows for interrogation of microstructural change within the white matter. DTI metrics (TR, FA, λII, λ⊥) are each sensitive to different features of white matter pathology, making them ideal to study degeneration within the white matter [15, 18–22]. Studies using DTI in conjunction with histology have validated these associations by using preclinical mouse models of myelin damage [18, 20, 22]. Specifically, cuperizone-induced myelin loss led to reduced diffusion anisotropy and increases in λ⊥ and TR [20]. Our previously used animal models of AD show that reduced diffusion anisotropy and increased λ⊥ appear during white matter degeneration, complete with axonal loss and evidence of demyelination [19]. An additional study using a rat model of glaucoma showed similar diffusion changes in the optic nerve in response to induced RGC loss [36]. Research using human postmortem brains found similar relationships between histological determinations of myelin content, axon counts, and reductions in FA as well as increases in TR. These results indicate that reduced FA and increased TR are associated with reductions in myelin and axon numbers [37]. Although it is difficult to speculate on the potential condition of the optic nerves and tracts in our subject pool of MCI and AD patients, collective evidence supports the possibility that our DTI results reflect gradual axonal loss and myelin disruption in the visual pathway among our MCI and AD patients.

Accumulating evidence suggests that the cognitive decline that defines MCI may stem from the development of early AD pathology [38]. Recognizing the clinical presentation and understanding the pathophysiological changes during the pre-dementia stage is critical to develop a therapeutic strategy for AD. The formal classification of MCI has been recently clarified to define a pre-dementia stage distinct from normal aging, when patients suffer a decline in memory and cognitive faculties [39]. Relative to healthy controls, MCI patients may present significantly lower levels of amyloid-β in cerebrospinal fluid and higher levels of PET amyloid-tracer uptake and binding, reflecting higher levels of accumulation within the brain—a classic hallmark of AD [2]. MCI cohorts also have significant changes in other biomarkers that are associated with AD including levels of tau/phospho-tau in cerebrospinal fluid [2, 38]. All these pieces of evidence support the idea that MCI represents an intermediate state between AD and healthy aging. In addition to the changes in amyloid-β and tau, white matter disruptions may also be present. We saw evidence for this in our study, with increases in TR and λ⊥, and decreases in FA in the optic nerve and splenium of the corpus callosum among the MCI patients. Our findings are in agreement with previously reported studies suggesting white matter disruptions occur during this prodromal stage of AD [6–8]. White matter is composed of axonal bundles and embeds the connectomic features of each individual. Disruption of these connections directly affects neural networks, which may play an important role in causing the clinical presentations of MCI, seen in memory decline and cognitive impairment [40].

Many previous studies have leveraged DTI to identify sites of white matter damage in the brains of AD and MCI patients [6–8], but these studies have largely ignored white matter within the visual pathway. While this pathway makes up a large section of white matter, it lies partially below the brain and is vulnerable to automatic exclusion by MRI pre-processing tools, such as skull-stripping algorithms. The optic nerves are also quite narrow, and their positions vary largely among individuals (see Supplementary Material) making it challenging for voxel-based morphometry approaches to identify it. We also attempted to apply fiber tracking algorithms to identify the whole extent of the visual pathway, but never obtained satisfactory results. This is due in part to the extremely narrow dimensions of the nerves, high angular turning of the fibers in some individuals, crossing fibers in chiasm, and adjacency to various white matter tracts.

Our ROI approach yields reliable and accurate measurements of DTI in optic nerves and tracts. The disadvantage was being more labor intensive and not measuring the whole extent of the optic nerves and tracts. Despite its small size, the optic chiasm has a unique “X” structure and can be easily identified on an axial brain image, which provides a reliable landmark to guide the selection of optic nerves and tracts (Fig. 3). To assure correct selections of these regions, we always reviewed 10–12 contiguous coronal slices anterior and posterior to the chiasm. The left and right optic nerves would merge in the chiasm, then split into left and right optic tracts.

One caveat to this study is the influence of partial volume effects, which reduce the sensitivity of our measurements in characterizing injured nerves. Instead of selecting the ROI on the axial/sagittal views of these nerves, we selected the ROI in the coronal view to minimize the partial volume effect. Optic nerves and tracts are thin. Even with carful ROI selection, partial volume effects could not be completed avoided. For future study, we recommend DTI scans with increased spatial resolution. We believe the trend would be the same but should provide a better sensitivity to characterize abnormality of the visual pathways in AD.

While the ADNI database does contain many more subjects than we analyzed, only a subset of those underwent DTI. Within the datasets we have explored, there were 1,879 subjects recruited in the ADNI database, among which, 49 AD, 133 MCI, and 66 controls had DTI scans. Patients with blurry vision or glaucoma were excluded to avoid the confounding factors to our analysis. We are using the maximum number of subjects available, without a gender imbalance between groups.

In conclusion, white matter damage in AD as detected by DTI extends to the optic pathway. Significant DTI changes including increases in TR and λ⊥, and decreases in FA occur early in MCI cohorts. These changes also occur in AD cohorts, compared to similarly aged, gender-matched controls. This finding may help contextualize OCT data from several studies showing reductions in RGCs among AD patients [34,41] and clinical data demonstrating AD-associated visual deficits [10, 11].

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was partly supported by NIH R01NS062830.

Data collection and sharing for this project was funded by the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) (National Institutes of Health Grant U01 AG024904) and DOD ADNI (Department of Defense award number W81XWH-12-2-0012). ADNI is funded by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bio-engineering, and through generous contributions from the following: Alzheimer’s Association; Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation; BioClinica, Inc.; Biogen Idec Inc.; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; Eisai Inc.; Elan Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd and its affiliated company Genentech, Inc.; GE Healthcare; Innogenetics, N.V.; IXICO Ltd.; Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Research & Development, LLC; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development LLC; Medpace, Inc.; Merck & Co., Inc.; Meso Scale Diagnostics, LLC; NeuroRx Research; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Pfizer Inc.; Piramal Imaging; Servier; Synarc Inc.; and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research is providing funds to support ADNI clinical sites in Canada. Private sector contributions are facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (http://www.fnih.org). The grantee organization is the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and the study is coordinated by the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study at the University of California, San Diego. ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory for Neuro Imaging at the University of Southern California.

Footnotes

Data used in preparation of this article were obtained from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database (adni.loni.usc.edu). As such, the investigators within the ADNI contributed to the design and implementation of ADNI and/or provided data but did not participate in analysis or writing of this report. A complete listing of ADNI investigators can be found at: http://adni.loni.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/how_to_apply/ADNI_Acknowledgement_List.pdf

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

The supplementary material is available in the electronic version of this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3233/JAD-141239.

Authors’ disclosures available online (http://j-alz.com/manuscript-disclosures/14-1239r2).

REFERENCES

- 1.Yankner BA, Mesulam MM. Seminars in medicine of the Beth Israel Hospital, Boston. beta-Amyloid and the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1849–1857. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199112263252605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Risacher SL, Saykin AJ. Neuroimaging and other biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease: The changing landscape of early detection. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2013;9:621–648. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Douaud G, Jbabdi S, Behrens TE, Menke RA, Gass A, Monsch AU, Rao A, Whitcher B, Kindlmann G, Matthews PM, Smith S. DTI measures in crossing-fibre areas: Increased diffusion anisotropy reveals early white matter alteration in MCI and mild Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroimage. 2011;55:880–890. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rowley J, Fonov V, Wu O, Eskildsen SF, Schoemaker D, Wu L, Mohades S, Shin M, Sziklas V, Cheewakriengkrai L, Shmuel A, Dagher A, Gauthier S, Rosa-Neto P. White matter abnormalities and structural hippocampal disconnections in amnestic mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One. 2013;8:e74776. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sexton CE, Kalu UG, Filippini N, Mackay CE, Ebmeier KP. A meta-analysis of diffusion tensor imaging in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2011;32:2322. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.05.019. e2325-2318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agosta F, Pievani M, Sala S, Geroldi C, Galluzzi S, Frisoni GB, Filippi M. White matter damage in Alzheimer disease and its relationship to gray matter atrophy. Radiology. 2011;258:853–863. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10101284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bozzali M, Falini A, Franceschi M, Cercignani M, Zuffi M, Scotti G, Comi G, Filippi M. White matter damage in Alzheimer’s disease assessed in vivo using diffusion tensor magnetic resonance imaging. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;72:742–746. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.72.6.742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Medina D, DeToledo-Morrell L, Urresta F, Gabrieli JD, Moseley M, Fleischman D, Bennett DA, Leurgans S, Turner DA, Stebbins GT. White matter changes in mild cognitive impairment and AD: A diffusion tensor imaging study. Neurobiol Aging. 2006;27:663–672. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Streilein JW. Ocular immune privilege: Therapeutic opportunities from an experiment of nature. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:879–889. doi: 10.1038/nri1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mendez MF, Mendez MA, Martin R, Smyth KA, Whitehouse PJ. Complex visual disturbances in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1990;40:439–443. doi: 10.1212/wnl.40.3_part_1.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cronin-Golomb A, Corkin S, Rizzo JF, Cohen J, Growdon JH, Banks KS. Visual dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease: Relation to normal aging. Ann Neurol. 1991;29:41–52. doi: 10.1002/ana.410290110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frisoni GB, Fox NC, Jack CR, Jr, Scheltens P, Thompson PM. The clinical use of structural MRI in Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2010;6:61–11. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2009.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frisoni GB, Pievani M, Testa C, Sabattoli F, Bresciani L, Bonetti M, Beltramello A, Hayashi KM, Toga AW, Thompson PM. The topography of grey matter involvement in early and late onset Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2007;130:720–730. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pearson RC, Esiri MM, Hiorns RW, Wilcock GK, Powell TP. Anatomical correlates of the distribution of the pathological changes in the neocortex in Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;2:4531–4534. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.13.4531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun SW, Liang HF, Cross AH, Song SK. Evolving Wallerian degeneration after transient retinal ischemiain mice characterized by diffusion tensor imaging. Neuroimage. 2008;40:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.11.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pierpaoli C, Jezzard P, Basser PJ, Barnett A, Di Chiro G. Diffusion tensor MR imaging of the human brain. Radiology. 1996;201:637–648. doi: 10.1148/radiology.201.3.8939209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Basser PJ, Mattiello J, LeBihan D. MR diffusion tensor spectroscopy and imaging. Biophys J. 1994;66:259–267. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80775-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun SW, Liang HF, Trinkaus K, Cross AH, Armstrong RC, Song SK. Noninvasive detection of cuprizone induced axonal damage and demyelination in the mouse corpus callosum. Magn Reson Med. 2006;55:302–308. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun SW, Liang HF, Mei J, Xu D, Shi WX. In vivo diffusion tensor imaging of amyloid-beta-induced white matter damage in mice. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;38:93–101. doi: 10.3233/JAD-130236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Song SK, Yoshino J, Le TQ, Lin SJ, Sun SW, Cross AH, Armstrong RC. Demyelination increases radial diffusivity in corpus callosum of mouse brain. Neuroimage. 2005;26:132–140. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song SK, Sun SW, Ramsbottom MJ, Chang C, Russell J, Cross AH. Dysmyelination revealed through MRI as increased radial (but unchanged axial) diffusion of water. Neuroimage. 2002;17:1429–1436. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Song SK, Sun SW, Ju WK, Lin SJ, Cross AH, Neufeld AH. Diffusion tensor imaging detects and differentiates axon and myelin degeneration in mouse optic nerve after retinal ischemia. Neuroimage. 2003;20:1714–1722. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhuang L, Sachdev PS, Trollor JN, Reppermund S, Kochan NA, Brodaty H, Wen W. Microstructural white matter changes, not hippocampal atrophy, detect early amnestic mild cognitive impairment. PLoS One. 2013;8:e58887. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cho H, Yang DW, Shon YM, Kim BS, Kim YI, Choi YB, Lee KS, Shim YS, Yoon B, Kim W, Ahn KJ. Abnormal integrity of corticocortical tracts in mild cognitive impairment: A diffusion tensor imaging study. J Korean Med Sci. 2008;23:477–483. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2008.23.3.477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oguz I, Farzinfar M, Matsui J, Budin F, Liu Z, Gerig G, Johnson HJ, Styner M. DTIPrep: Quality control of diffusion-weighted images. Front Neuroinform. 2014;8:4. doi: 10.3389/fninf.2014.00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trick GL, Trick LR, Morris P, Wolf M. Visual field loss in senile dementia of the Alzheimer’s type. Neurology. 1995;45:68–74. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fotiou DF, Brozou CG, Haidich AB, Tsiptsios D, Nakou M, Kabitsi A, Giantselidis C, Fotiou F. Pupil reaction to light in Alzheimer’s disease: Evaluation of pupil size changes and mobility. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2007;19:364–371. doi: 10.1007/BF03324716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mendola JD, Cronin-Golomb A, Corkin S, Growdon JH. Prevalence of visual deficits in Alzheimer’s disease. Optom Vis Sci. 1995;72:155–167. doi: 10.1097/00006324-199503000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crutch SJ, Lehmann M, Schott JM, Rabinovici GD, Rossor MN, Fox NC. Posterior cortical atrophy. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11:170–178. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70289-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Minoshima S, Giordani B, Berent S, Frey KA, Foster NL, Kuhl DE. Metabolic reduction in the posterior cingulate cortex in very early Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1997;42:85–94. doi: 10.1002/ana.410420114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blanks JC, Torigoe Y, Hinton DR, Blanks RH. Retinal pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. I. Ganglion cell loss in foveal/parafoveal retina. Neurobiol Aging. 1996;17:377–384. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(96)00010-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hinton DR, Sadun AA, Blanks JC, Miller CA. Optic-nerve degeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 1986;315:485–487. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198608213150804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fujimoto JG, Pitris C, Boppart SA, Brezinski ME. Optical coherence tomography: An emerging technology for biomedical imaging and optical biopsy. Neoplasia. 2000;2:9–25. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paquet C, Boissonnot M, Roger F, Dighiero P, Gil R, Hugon J. Abnormal retinal thickness in patients with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci Lett. 2007;420:97–99. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.02.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parisi V, Restuccia R, Fattapposta F, Mina C, Bucci MG, Pierelli F. Morphological and functional retinal impairment in Alzheimer’s disease patients. Clin Neurophysiol. 2001;112:1860–1867. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(01)00620-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hui ES, Fu QL, So KF, Wu EX. Diffusion tensor MR study of optic nerve degeneration in glaucoma. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2007;2007:4312–4315. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2007.4353290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schmierer K, Wheeler-Kingshott CA, Boulby PA, Scaravilli F, Altmann DR, Barker GJ, Tofts PS, Miller DH. Diffusion tensor imaging of post mortem multiple sclerosis brain. Neuroimage. 2007;35:467–477. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Diniz BS, Pinto Junior JA, Forlenza OV. Do CSF total tau, phosphorylated tau, and beta-amyloid 42 help to predict progression of mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2008;9:172–182. doi: 10.1080/15622970701535502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, Dubois B, Feldman HH, Fox NC, Gamst A, Holtzman DM, Jagust WJ, Petersen RC, Snyder PJ, Carrillo MC, Thies B, Phelps CH. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shu N, Liang Y, Li H, Zhang J, Li X, Wang L, He Y, Wang Y, Zhang Z. Disrupted topological organization in white matter structural networks in amnestic mild cognitive impairment: Relationship to subtype. Radiology. 2012;265:518–527. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12112361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kesler A, Vakhapova V, Korczyn AD, Naftaliev E, Neudorfer M. Retinal thickness in patients with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2011;113:523–526. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2011.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.