Abstract

Background

A hospital admission provides an opportunity to help people stop smoking. Providing smoking cessation advice, counselling, or medication is now a quality-of-care measure for U.S. hospitals. We assessed the effectiveness of smoking cessation interventions initiated during a hospital stay.

Methods

We searched the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Review Group's register for randomized and quasi-randomized controlled trials of smoking cessation interventions (behavioral counselling and/or pharmacotherapy) that began during hospitalization and had a minimum of 6 months follow-up. Two authors independently extracted data from each paper, with disagreements resolved by consensus.

Results

33 trials met inclusion criteria. Smoking counselling that began during hospitalization and included supportive contacts for >1 month after discharge increased smoking cessation rates at 6-12 months (pooled OR 1.65, 95% CI 1.44-1.90). No benefit was found for interventions with less post-discharge contact. Counselling was effective when offered to all hospitalized smokers and to the subset admitted for cardiovascular disease. Adding nicotine replacement therapy to counselling produced a trend toward efficacy over counseling alone (OR 1.47, 95% CI 0.92-2.35). One study added bupropion to counselling. It had a nonsignificant result (OR 1.56, 95% CI 0.79-3.06).

Conclusions

Offering smoking cessation counselling to all hospitalized smokers is effective as long as supportive contacts continue for >1 month after discharge. Adding NRT to counselling may further increase smoking cessation rates and should be offered when clinically indicated, especially to hospitalized smokers with nicotine withdrawal symptoms.

Introduction

Tobacco smoking remains the leading preventable cause of death in the United States.1 Smoking-attributable morbidity and mortality are reduced by smoking cessation, even when it occurs after the onset of a smoking-related disease.2 Smokers who are hospitalized have an opportunity to initiate cessation because U.S. hospitals are smoke-free.3 Smokers must abstain temporarily from tobacco use while hospitalized, allowing them to experience tobacco abstinence away from environmental cues to smoke. Hospitalisation may also increase a smoker's motivation to quit because illness, especially if tobacco-related, increases a smokers’ perceived vulnerability to the harms of tobacco use, providing a ‘teachable moment’ for change. Finally, illness brings smokers to the healthcare setting, where smoking cessation interventions can be provided. For these reasons, providing or initiating tobacco dependence treatments in hospitals may be an effective preventive health strategy.

Hospital quality-of-care standards set by the Joint Commission (JCAHO) and Medicare (CMS) now include a tobacco measure.4 It assesses the proportion of current or past-year smokers who received smoking advice, counseling, or medication during a hospitalization for acute myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, or pneumonia. This measure is reported quarterly on a public website and is included in pay-for-performance reimbursement programs.5 This development stimulated interest in providing hospital-based smoking intervention. It is critical that programs designed to meet the new quality standard effectively promote smoking cessation after hospital discharge.

Smoking cessation interventions that have been provided in the hospital setting include behavioral counselling of varying intensity, pharmacotherapy with nicotine replacement (NRT) or bupropion, and combinations of the two. This systematic review aims to summarize the evidence about the efficacy of smoking cessation interventions for hospitalized patients. An extended version is published and regularly updated in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.

Methods

Search strategy

We searched the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Review Group register of trials, which includes the results of systematic searches, updated quarterly, of MEDLINE, PsycINFO, EMBASE and conference abstracts. Searches for the register cover smoking cessation, nicotine dependence, nicotine addiction and tobacco use. We identified studies mentioning hospital or inpatient or admission in the title, abstract, or keywords. The most recent search was in January 2007. We identified one additional paper from current contents alerting.6

Inclusion criteria

We included randomized or quasi-randomized controlled trials that enrolled patients who were hospitalized and were current smokers (defined as having smoked in the month before admission) or recent quitters (defined as having quit from one month to one year before admission) and had at least 6 months of follow-up after randomization. We excluded secondary prevention or cardiac rehabilitation trials that did not recruit on the basis of smoking history, and trials in patients hospitalized for psychiatric disorders or substance abuse (including inpatient tobacco addiction programs). We included trials that recruited hospitalized smokers regardless of their intention to quit smoking and trials that recruited only smokers who planned to quit after discharge.

We included any intervention that was initiated during hospitalization and aimed to increase motivation to quit, assist a quit attempt, or avoid relapse. The intervention could include advice to quit, behavioral counseling, or pharmacotherapy, with or without continued contact after hospital discharge. We developed a priori four categories of counselling intensity based on the duration of contact in the hospital and the duration of follow-up contact after discharge:

1 contact in hospital lasting ≤ 15 minutes and no post-discharge support.

≥1 contact in hospital lasting >15 minutes total and no post-discharge support.

Any hospital contact plus post-discharge support lasting ≤1 month.

Any hospital contact plus post-discharge support lasting > 1 month.

The intervention could be delivered by physicians, nursing staff, psychologists, smoking cessation counsellors or other hospital staff. The control intervention could be any less intensive intervention or usual care. The principal outcome measure was abstinence from smoking at least 6 months after randomization

Data extraction

Studies identified by search strategies were checked for relevance. Two authors extracted data independently from selected studies, resolving disagreements by consensus. Authors agreed about study inclusion or exclusion for approximately 95% of studies reviewed. We extracted data on study setting, recruitment criteria (including types of admission diagnoses, smoking status at admission, and willingness to make a quit attempt), participant characteristics, method of randomization and allocation concealment, intervention and control conditions (including therapist types, duration of contact and/or medication in hospital and after discharge), and outcome measures (length of follow-up, definition of abstinence, validation of self-reported smoking status).

Data synthesis

To assess outcome, we used the most conservative measure of quitting at the longest follow up. When multiple outcomes were reported, we preferred a biochemically validated quit rate to self-reported abstinence, continuous or sustained abstinence to point prevalence abstinence, and 12-month follow-up to 6-month follow-up. We calculated quit rates based on the numbers of randomized patients, excluding deaths and counting as smokers all patients who dropped out, were lost to follow-up or failed to provide biochemical validation of nonsmoking status. We pooled study outcomes using Mantel-Haenszel fixed-effect model7 and expressed results as an odds ratio (OR) for smoking abstinence with a 95% confidence interval. We assessed statistical heterogeneity among studies with the I2 statistic8; where it exceeded 50%, we explored possible reasons using subgroup analyses or considered the impact of outliers. Where studies were judged by quality criteria to be more prone to bias, we planned sensitivity analyses to assess whether their inclusion altered our findings.

Data were analyzed using the pre-determined four-level classification of intervention intensity. We did a subgroup analysis based on patients’ admitting diagnosis: cardiovascular, respiratory, and cancer. Another subgroup analysis assessed the effects of interventions designed to be delivered to all smokers who were admitted, regardless of the admitting diagnosis.

Description of studies

Thirty-three trials conducted in 9 countries between 1990 and 2007 met inclusion criteria and contributed to the review. (Tables 1, 2) We excluded 51 studies which appeared relevant but did not meet all inclusion criteria.

Table 1.

Trials of Smoking Cessation Counseling

| Source |

Setting -country/ -# of hospitals |

Subjects n, diagnoses -smoking status -willingness to quit |

Study design # of arms |

Counseling Intervention Inpatient Post-discharge |

Control condition | Pharmacotherapy? |

Outcome -Abstinence type, -longest f/u, -validation method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bolman 200240 | Netherlands 11 hospitals | 789 current smokers (smoked in past week) Admitted to cardiac ward. Willingness to quit not reported |

Quasi-experimental, by hospital. 2 arms | MD advice, counseling by staff nurse (15-30 min), self-help material Post-discharge: none [Intensity 2] | Usual care | No | Sustained abstinence. at 12 months No validation |

| CASIS 199210 | USA 3 hospitals | 267 current smokers or recent quitters (smoke in past 2 mo). Inpatients with CAD enrolled post-catheterization. Not selected by willingness to quit. |

RCT 2 arms |

Counseling (40 min) by health educator, self-help material. Post-discharge: telephone calls (at 1, 3 wks and 3m) [Intensity 4] |

Advice only | No | Sustained abstinence at 6 mo, 12 mo Validation: CO. |

| Chouinard 200525 | Canada (# hospitals not reported) | 168 current smokers (in past month) Inpatients with CVD (MI, angina, CHF) or PVD Not selected by motivation to quit | RCT 3 arms |

Group 1: Stage-based counseling by research nurse (10-60 mins, average, 40 min). [Intensity 2] Group 2. Same as group 1 + 6 telephone calls over 2 mo post-discharge [Intensity 4] |

Advice only | NRT in 23%, not allocated by study arm | Sustained abstinence at 2 & 6 months Validation: Urine cotinine or CO |

| Croghan 200536 | USA 1 hospital |

30 smokers Inpatients having surgery for newly diagnosed lung or esophageal cancer. Willingness to quit not reported. | RCT 2 arms |

MD advice + stage-based counseling by trained counselor (45 min) + NRT Post-discharge: none [Intensity 2] |

Physician advice only | NRT | 7-day point-prevalence abstinence at 6m Validation: CO or saliva tobacco alkaloid |

| De Busk 199412 | USA 5 hospitals |

252 current smokers or recent quitters (smoked in past 6m) Inpatients with acute MI. Willing to make a quit attempt |

RCT 2 arms |

Physician advice + behavioral counseling by research nurse; + self-help material, relaxation tapes). Post-discharge: 8 telephone calls (at 48 hr, 1 wk, and monthly for 6m) [Intensity 4] | Advice only | NRT: Yes (partial) ('reserved for highly-addicted patients'); | Sustained abstinence at 6m, 12m. Validation: CO and plasma cotinine. |

| Dornelas 200018 | USA 1 hospital |

100 current smokers (smoked in past month). Inpatients with acute MI. Not selected by willingness to quit. | RCT 2 arms |

Behavioral counseling (total 20 min); 7 telephone calls post-discharge (at <1, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, 26 wk) [Intensity 4] | Advice only | No | 7-day point-prevalence abstinence at 12m. Validation by significant other (only in 70%). |

| Feeney 200137 | Australia 1 hospital |

198 current smokers (smoked in past week). Inpatients with acute MI admitted to CCU. Willingness to quit not reported. | RCT 2 arms |

Physician advice to quit + behavioral counseling by nurse (time not specified)); 8 telephone calls post-discharge (at 1,2,3,4 wks and 2,3,6,12m) [Intensity 4] nurse. | Same as intervention in hospital but no follow up after discharge [Intensity 2] | No | Sustained abstinence at 1m,3m, 12m. Validation: Urinary cotinine |

| Froelicher 200423 | USA 10 hospitals |

277 female current smokers or recent quitters (smoked in past month), Inpatients with CVD or PVD. Willing to make quit attempt at discharge. | RCT 2 arms |

Physician advice, cognitive/behavioural and relapse prevention counseling (30-45 min) by nurse; 5 telephone calls after discharge (at 2,7,21,28,90 days, 5-10 min/call) [Intensity 4] | Modified usual care (physician advice + booklet) | NRT offered after discharge to relapsers who wanted to quit (used by 20% of intervention, 23% of controls). | 7-day point-prevalence abstinence at 12m. Validation: Saliva cotinine or family/friend verification |

| Hajek 200238 | UK 17 hospitals |

540 current smokers. Inpatients with acute MI who were. willing to stop smoking entirely. | RCT 2 arms |

Nurse counseling (20-30 min) + self-help materials. [Intensity 2] | Brief advice + booklet | No | 7-day point-prevalence abstinence at 12m. Validation: CO and salivary cotinine. |

| Hasuo 200424 | Japan 1 hospital |

120 current smokers or recent quitters (smoked in past month) Inpatients (all diagnoses) Intend to quit at discharge | RCT 2 arms |

Nurse counseling (3 × 20 min sessions) + 3 telephone calls after discharge (at 7, 21, 42 days, 5 min/call) [intensity 4] | Same as intervention in hospital but no post-discharge contact [Intensity 2] | No | Abstinence (type not stated) at 12m Validation: urinary cotinine at 12m |

| Hennrikus 200526 | USA 4 hospitals |

2095 current smokers (smoked in past week) Inpatients with all diagnoses, not selected by willingness to quit. | RCT 3 arms |

Group 1. Physician advice + nurse counseling (motivational interviewing and relapse prevention) for 20 min. (43% of counseling done after discharge, not at bedside). Follow up: 3-6 phone calls over 6m (10 min/call median). [Intensity 4] Group 2: Physician advice + smoking cessation booklet + additional mailed booklet after discharge. [Intensity 1] |

Modified usual care (smoking cessation booklet) | No | 7-day point-prevalence abstinence at 12m. Validation: Saliva cotinine |

| Miller 199714 | USA 4 hospitals |

1942 current smokers. All inpatients (32% cardiovascular, 12% pulmonary diagnoses) Prepared to make quit attempt and willing to get help | RCT 3 arms |

Group 1. Physician advice + behavioural counseling (30 min) + self-help material, relaxation tapes, video. Post-discharge: 4 telephone calls (at 48hr, 1, 3 wks, 3m [Intensity 4] Group 2. Physician advice + behavioural counseling (30 min) + self-help material, relaxation tapes, video. Post-discharge: 1 telephone call (at 48 hr) [Intensity 3] |

Advice only | No | Sustained abstinence at 3, 6 & 12 months. Validation: Plasma cotinine or family member corroboration. |

| Mohiuddin 20076 | USA 1 hospital |

209 current smokers CCU inpatients with MI or acute coronary syndrome or decompensated CHF. Not selected by willingness to quit. | RCT 2 arms |

Intervention: Counseling (30 mins) + self-help booklet + free NRT and/or bupropion. Follow up: weekly group meetings (60 min each for up to 3m) with trained tobacco counselor [Intensity 4] |

Inpatient: same as intervention group, but no post-discharge contact [Intensity 2] | NRT or bupropion offered on individual basis to both groups | Sustained abstinence at 3m, 6m, 12m. (note: sustained abstinence to 24m reported but not used in pooling) Validation: CO |

| Nagle 200534 | Australia 1 hospital |

1422 current smokers or quitters (smoked in past 12m). Inpatients (all diagnoses) excluding intensive care units. Not selected by willingness to quit |

RCT 2 arms |

Nurse counseling (20 min, withdrawal symptom management, coping skills) + booklet + offer of NRT Follow up: none. [Intensity 2] |

Modified usual care (Physician advice + booklet) | NRT in hospital (3% received) and for 5 days after discharge | 7-day point-prevalence abstinence at 12m. Validation: Saliva cotinine |

| Ortigosa 200019 | Spain 2 hospitals |

90 current smokers. Inpatients with acute MI. Not selected by willingness to quit | RCT 2 arms |

Physician advice. Follow up: 3 telephone calls (at 2,3,4 wks). [Intensity 3] | Usual care | No | 7-day point-prevalence abstinence at 12m.. Validation: CO |

| Pedersen 200530 | Denmark 1 hospital |

105 current smokers Inpatients with cardiac disease, not selected by willingness to quit. | RCT 2 arms |

Usual hospital care (advice to quit + information about NRT + NRT available) Follow up: 5 visits after discharge (30 min/meeting); [Intensity 4] |

Usual care (advice to quit + NRT available) | NRT (partial) | Abstinence (probably point-prevalence) at 12m. Validation: no. |

| Pederson 199135 | USA 1 hospital |

74 current smokers. Inpatients with COPD, not selected by willingness to quit. | RCT 2 arms |

Counseling (total 45-160 mins), self-help materials. Post-discharge: none [Intensity 2] |

Advice only | No | 7-day point-prevalence abstinence at 6m. Validation: Serum COHb (in a sample). |

| Pelletier 199839 | Canada 3 hospitals |

504 current smokers. Inpatients with acute MI who were willing to quit | Quasi-experimental, allocation by hospital | Physician advice. Self-help materials. [Intensity 2] | Usual care | No | Abstinence: self-reported PP at 12m Validation: None. |

| Quist-Paulsen 200321 | Norway 1 hospital |

240 current smokers Cardiac ward inpatients with MI, unstable angina, post-CABG care. Not selected by willingness to quit. | RCT 2 arms |

Nurse counseling (1-2 times, time not specified), advice on using NRT). Post-discharge: 5 telephone calls (2,7,21, days, 3m, 5m) , clinic visit to cardiac nurse at 6 wk); NRT encouraged for subjects with strong urges to smoke in hospital. [Intensity 4] | Usual care (advice + booklet) | NRT | 7-day point-prevalence abstinence at 12m. Validation: Urine cotinine. |

| Reid 200332 | Canada 1 hospital |

254 current smokers (smoked in past month) Inpatients with MI, CABG, PTCA, coronary angiography Motivated to quit | RCT 2 arms |

Nurse counseling (5-10 mins) + booklet . Follow up: nurse call at 4 wks; if smoking, offered 3 × 20 min in-person counseling sessions (wks 4,8,12) and NRT patch recommended for 8 wks. [Intensity 4] | Same as intervention group but no contact after discharge | NRT if relapse after discharge | Abstinence: 7-day PP at 12m. Validation: CO requested in random 25 self-reported non-smokers |

| Rigotti 199413 | USA 1 hospital |

87 current smokers or recent quitters (past 6 mo) Inpatients scheduled for CABG surgery. Not selected by willingness to quit. | RCT 2 arms |

Behavioral counseling (60 min) by nurse, self-help materials, video. Post-discharge: 1 telephone call (at 1 wk) [Intensity 3] | Advice only | No | Sustained abstinence at 4m, 8m, 12m. Validation: Salivary cotinine. |

| Rigotti 199715 | USA 1 hospital |

650 current smokers or recent quitters (smoked in past month) Inpatients with all diagnoses. Not selected by willingness to quit. | RCT 2 arms |

MD advice, behavioral counseling (total 15 min) by trained counselor; booklet. Post-discharge: 3 telephone calls (1,2,3 wks) [Intensity 3] |

Usual care | NRT in 4% | Abstinence: PP at 6m. Validation: Salivary cotinine. |

| Simon 199716 | USA 1 hospital |

299 current smokers. Inpatients undergoing non-cardiac surgery. Prepared to make quit attempt. | RCT 2 arms |

Behavioral counseling (30-60 min) by health educator; self-help materials, video. NRT gum for 3 m. if no contraindications. Post-discharge: 5 telephone calls (1-3 wks, 2m, 3m). [Intensity 4] | Advice only | NRT in 65% of intervention, 17% of control | Abstinence: PP at 12m Validation: Serum or saliva cotinine or corroboration by significant other. |

| Simon 200322 | USA 1 hospital |

223 current smokers (smoked in past week), in contemplation or action stage, able to use NRT. Inpatients (all diagnoses) | RCT 2 arms (NRT in both arms) |

Cognitive/behavioural counseling (30-60 min) by nurse or health educator + booklet Post-discharge: 5 telephone calls at 1,3 wks and 1m, 2m, 3m (<30 min/call); [Intensity 4] | Brief counseling (10 min) | NRT patches × 8 wks to all patients in both groups | Abstinence: 7-day PP at 12m. Validation: Saliva cotinine <15 ng/ml OR spousal corroboration. |

| Stevens 199311 | USA 2 hospitals |

1119 current smokers or recent quitters (smoked in past 3 months) Inpatients with all diagnoses. Not selected by willingness to quit. | Not random (allocation alternated between hospitals monthly). |

Behavioral counseling (20 min) by masters level counsellor, self-help materials, video. Postdischarge: 1-2 telephone calls (at 1-3 wks) [Intensity 3] | Usual care | No | Sustained abstinence at 3m, 12m. Validation: None |

| Stevens 200020 | USA 2 hospitals |

1173 current smokers or recent quitters (smoked in past 3 months) Inpatients with all diagnoses. Not selected by willingness to quit. | Not random (alternated between hospitals monthly). | Behavioral counseling (20 min) by respiratory therapist, self-help materials, video. Post-discharge: 1 telephone call at 1 wk [Intensity 3] | Usual care | No | Sustained abstinence at 6m, 12m Validation: None. |

| Taylor 19909 | USA 4 hospitals |

173 current smokers or recent quitters (smoked in past 6 mo) Inpatients with acute MI. Prepared to make a quit attempt. | RCT 2 arms |

Behavioral counseling (time not stated) by nurse, self-help materials, relaxation tapes. Post-discharge: 6-7 telephone calls at 1-3 wks + very month for 4m) [Intensity 4] | Usual care | NRT gum given to 5 patients. | Sustained abstinence at 3m, 12m. Validation: Serum thiocyanate, expired air CO. |

Table 2.

Trials of Pharmacotherapy

| Source |

Setting Country # of hospitals |

Subjects N, Diagnoses Smoking status Willingness to quit |

Study design # of arms |

Pharmacotherapy: Intervention, Control |

Counseling provided |

Outcome Longest f/u, Type of abstinence, Validation method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nicotine replacement therapy | ||||||

| Campbell 199128 | UK 1 hospital |

212 current smokers. Inpatients with smoking-related diseases (heart disease, lung disease, other). Willingness to quit not stated. | RCT 2 arms |

Intervention: Nicotine gum 2-4 mg, × 3mo Control: Placebo gum × 3 mo |

MD advice, counseling (time not stated).by trained counnselor Post-discharge: 5 clinic visits (2, 3, 5 wks, 3m, 6m) with counselor [Intensity 4] |

Sustained abstinence at 6m, 12m. Validation: CO. |

| Campbell 199629 | UK 1 hospital |

62 current smokers. Inpatients with respiratory or cardiovascular disease who were prepared to make a quit attempt | RCT 2 arms |

Intervention: Nicotine patch, 17.5-35 mg, × 12 wk) Control: Placebo patch × 12 mo. |

MD advice., counselling (30-60 min) by trained counsellor Post-discharge: 4 clinic visits at 2,4,8,12 wk with counselor [Intensity 4] |

Sustained abstinence at 3, 6, 12m. Validation: CO. |

| Molyneux 200333 | UK 1 hospital |

274 current smokers (smoked in past month). Medical and surgical inpatients. Not selected by willingness to quit. | RCT 3 arms |

Group 1: offer of open label NRT × 6 wks (choice of gum, patch, inhalator, lozenge, nasal spray); 96% used some NRT. Group 2: no NRT, counseling only Group 3: no NRT, usual care. |

Groups 1 & 2: Brief counseling (20 min) + booklet. Post-discharge: no contact [Intensity 2] Group 3: usual care |

Sustained abstinence at 3m, 12m. Validation: CO |

| Lewis 199817 | USA 1 hospital. |

185 current smokers. Inpatients excluding cardiac conditions. Prepared to make quit attempt. | RCT 3 arms |

Group 1: Nicotine patch (22 mg for 3 wk + 11 mg for 3 wk) Group 2: Placebo patch Group 3: No NRT |

Groups 1 & 2: MD advice, counseling (2-3 mins), self-help materials. Post-discharge: 4 telephone calls at 1,3,6 wks, 6m). [Intensity 4] Group 3: Advice only |

7-day point-prevalence abstinence at 6m. Validation: CO. |

| Vial 200231 | Australia 1 hospital |

102 current smokers Inpatients (medical and surgical wards) Willing to stop smoking | RCT 3 arms |

Groups 1 & 2: Nicotine patches for up to 16 wks Group 3 No NRT |

Group 1: Pharmacist consultation about NRT use (30-45 mins) + booklet Post-discharge: up to 16 weekly visits to get patches from hospital pharmacist. [Intensity 4] Group 2: Same as above, but post-discharge visits made to a community pharmacist Group 3: usual care (advice to quit + booklet) |

Sustained abstinence at 3m, 6m, 12m. Validation: CO test ‘whenever possible’ - frequency not stated |

| Bupropion | ||||||

| Rigotti 200627 | USA 5 hospitals |

254 current smokers (smoked in past month) Inpatients with cardiovascular disease (MI, unstable angina, CHF) or PVD Willing to consider smoking cessation. |

RCT 2 arms |

Intervention: Bupropion SR 300 mg/day × 12 wk, started in hospital. Control: Placebo × 12 wk |

Both groups: Cgnitive/behavioural counseling (30-45 min) by nurse + booklet + videotape. Post-discharge: 5 telephone calls (10 min/call) at 2,7,21 days, 2 mo, 3 mo) Total counseling: 85-90 min |

Continuous abstinence at 2,4,12, 52 wks. Validation: Saliva cotinine at 12 and 52 wks, CO at 2 and 4 wks. |

All 33 included studies provided stop-smoking advice and/or behavioral counselling in the hospital. The duration of counselling ranged from less than 5 minutes to one hour. A nurse or trained counsellor provided the intervention in 32 studies. Eleven studies included physician advice to quit. Most studies also included self-help materials such as booklets, audiotapes, or videotapes. Follow-up support after hospital discharge was provided in 25 studies; 19 studies provided it by telephone9-27, while 6 studies had in-person visits.6, 28-32 The duration of extended support ranged from one week to 6 months after discharge.

Pharmacotherapy with nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) or bupropion was an optional addition to counselling in many studies, but only 6 studies tested the efficacy of pharmacotherapy independent of counselling. Five of these studies tested the efficacy of adding NRT to counselling,17, 28, 29, 31, 33 while one study tested the efficacy of adding bupropion to counselling.27 One other trial tested the efficacy of adding counselling to NRT. 22 No study tested the efficacy of pharmacotherapy versus placebo in the absence of counselling. Pharmacotherapy was allowed as part of the intervention in a number of other studies but the pharmacotherapy was not systematically assigned by group. Ten studies reported providing NRT to a subgroup of patients or did not specify the extent of its use,9, 12, 15, 16, 21-23, 25, 30, 32 , while two studies included bupropion in a similar fashion.6, 25

All studies included adults who smoked cigarettes currently or within the past month, but 6 studies also included recent quitters as well as current smokers. 10-13, 20, 34 Twenty-eight of 33 studies assessed cigarette abstinence 12 months after hospital discharge. Five studies had only a 6-month follow-up.15, 17, 30, 35, 36

Methodological quality of included studies

Study design and randomization

Twenty-nine of the 33 studies randomized individual patients to experimental condition; 15 of these reported a procedure for random assignment and allocation concealment that we judged likely to avoid recruitment bias.9, 14, 16-18, 21, 23, 24, 27, 30-32, 34, 37, 38 Fourteen studies did not report the method of randomization and concealment in sufficient detail to judge the quality. Four studies allocated treatment by hospital rather than by patient; none of these randomly assigned hospitals to condition 11, 20, 39, 40 Two allocated treatment by alternating between hospitals over time,11, 20 one study used a quasi-experimental design39 and one study40 randomly assigned 7 of 11 hospitals to condition but allowed 4 hospitals to choose their condition. Because these 4 studies have the potential problem of recruitment bias and underestimation of confidence limits due to intra-cluster correlation, we conducted a sensitivity analysis on the effect of excluding them.

Definition and validation of tobacco abstinence

Sixteen of 33 studies used the preferred measure, sustained abstinence, to assess outcome. 6, 9-14, 20, 25, 27-29, 31, 33, 37, 40 The other 17 studies used point-prevalence abstinence. To avoid over-estimation of treatment effects in smoking cessation studies, self-reported tobacco abstinence should be biochemically validated and patients lost to follow-up counted as smokers.41 Twenty-seven of 33 studies validated subjects’ self-reports of quitting at the follow-up assessment. Biochemical validation of smoking status was done in 26 studies, by expired air carbon monoxide in 13,6, 9, 10, 12, 17, 19, 28, 29, 31-33, 36, 38 and by plasma, salivary, or urinary cotinine in 15 studies.12-16, 21-27, 34, 37, 38 One study used corroboration by significant other as the only validation method.18 Four other studies used “corroboration by significant other” in cases where a plasma or salivary cotinine measure was not available.14, 17, 22, 23 Five studies did not validate self-reported quitting at the follow-up assessment.11, 20, 30, 39, 40 Most studies recorded those lost to follow-up as continuing smokers.

Results

Effect of counselling interventions

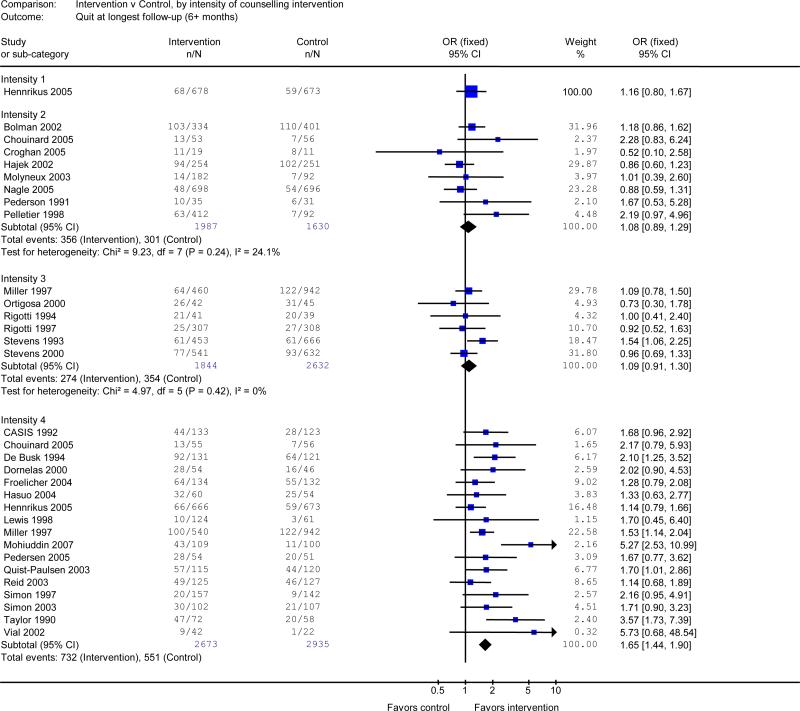

Counseling interventions were analyzed using the pre-determined four-level classification of intervention intensity. Only one study assessed a brief inpatient intervention with no subsequent support (intensity 1).26 This was not more effective than usual care (OR 1.16, 95% CI 0.80 to 1.67). Eight studies tested a longer inpatient intervention with no contact after discharge (intensity 2).25, 33-36, 38-40 There was no benefit in the pooled analysis of these studies (OR 1.08, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.29). Similarly, no statistically significant benefit was found in a pooled analysis of 6 studies that tested an inpatient intervention with contacts continuing for up to 1 month after discharge (intensity 3)11, 13-15, 19, 20 (OR 1.09, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.31). There was substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 53%) in the results of 18 studies that tested the highest intensity intervention (intensity 4), consisting of inpatient counselling that continued for more than 1 month after discharge. 6, 9, 10, 12, 14, 16-18, 21-26, 30-32 However, one study was an extreme outlier. 37 It reported a very large effect (OR 49) due to an unusually low cessation rate in the control condition. It also had a very high dropout rate across conditions. Excluding this trial from the meta-analysis reduced the heterogeneity (I2 = 35%). The level 4 intervention increased quit rates in the pooled estimate (OR 1.65, 95% CI 1.44 to 1.90).

Sensitivity analyses

Thirteen of the studies testing intensive counselling (intensity 4) included the option of pharmacotherapy, principally NRT.6, 9, 12, 14, 16, 17, 21-23, 25, 30-32 The odds ratio for the effect of counselling remained statistically significant when these studies were excluded (OR 1.36, 95% CI 1.04-1.77), suggesting that the efficacy of the intensive counselling interventions was not due to the use of NRT.

Nine of the 17 studies that delivered the highest intervention intensity (intensity 4) only included smokers who were willing to attempt cessation after discharge.9, 12, 14, 16, 17, 23, 24, 31, 32 An intervention effect persisted in a pooled analysis of the remaining 8 studies that recruited subjects regardless of their interest in quitting after discharge (OR 1.70, 95% CI 1.38-2.09). Another sensitivity analysis excluded studies that had included subjects who had not smoked for more than one month before admission. 9-13, 20, 34 Limiting the analysis to studies that recruited only current smokers (e.g., smoked in the past month) did not change the results (intensity 3: OR 1.01, 95% CI 0.77-1.32; intensity 4, OR 1.57, 95% CI 1.35-1.82).

Pre-planned sensitivity analyses excluded studies with methodological limitations. Excluding the four studies that did not randomly assign treatment by patient did not change the results.11,20,39, 40 Excluding the five studies that did not validate self-reported smoking cessation outcomes11, 20, 30, 39, 40 did not alter the results (intensity 2: OR 0.94, 95% CI 0.74-1.20; intensity 3, OR 1.01, 95% CI 0.78-1.31; intensity 4: OR 1.65, 95% CI 1.44-1.90).

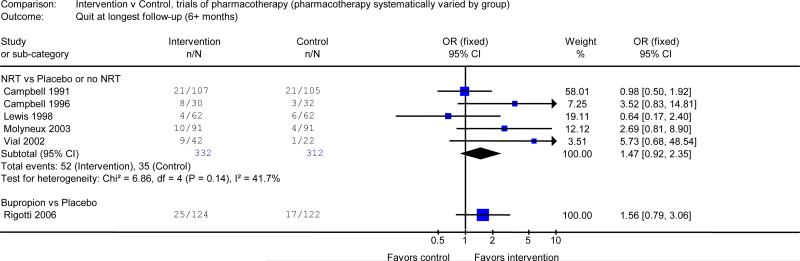

Effect of pharmacotherapy

No study compared pharmacotherapy to placebo as a single intervention without counselling. Trials of pharmacotherapy either tested the effect of adding pharmacotherapy to counselling or, conversely, the effect of adding counselling to pharmacotherapy. Five trials17, 28, 29, 31, 33 tested the effect of adding NRT to counselling. In these trials, NRT was compared with placebo NRT or no NRT. Pooled analysis of these studies produced an OR of 1.47,(95% CI 0.92 to 2.35). One trial offered NRT to all subjects and tested the additional benefit of intensive vs. minimal counselling.22 The OR was 1.71 for sustained abstinence (95% CI 0.90 to 3.23). The result was consistent with the impact of intensive counselling observed in the absence of pharmacotherapy.

One study27 systematically compared the use of bupropion with placebo. It did not detect a statistically significant effect of the drug over intensive counselling alone (OR 1.56, 95% CI 0.79 to 3.06) but the confidence limits were broad.

Effect of intervention by diagnosis

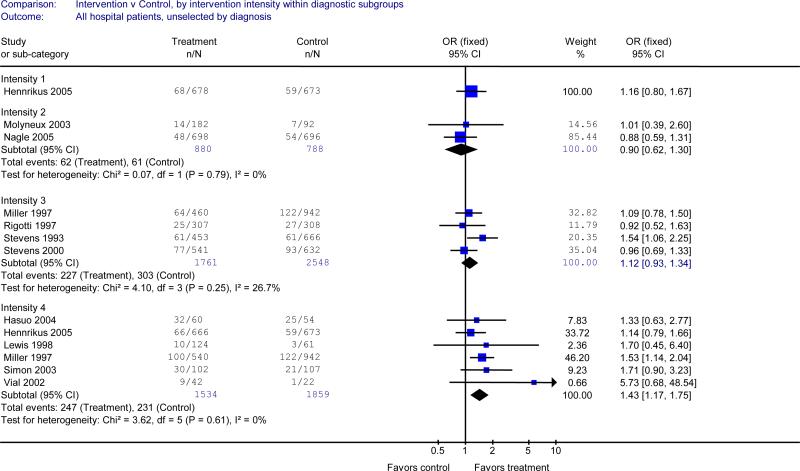

Eleven studies enrolled hospitalized smokers regardless of their admitting diagnosis.11, 14, 15, 17, 20, 22, 24, 26, 31, 33, 34 The results in this subgroup were similar to the results for the main analysis. Interventions with the highest category of intensity (counselling in hospital and >1 month of support after discharge) were effective in a pooled analysis of 6 studies (OR 1.43, 95% CI 1.17 to 1.75). 14, 17, 22, 24, 26, 31 Less intensive interventions demonstrated no effect (Table 2A).

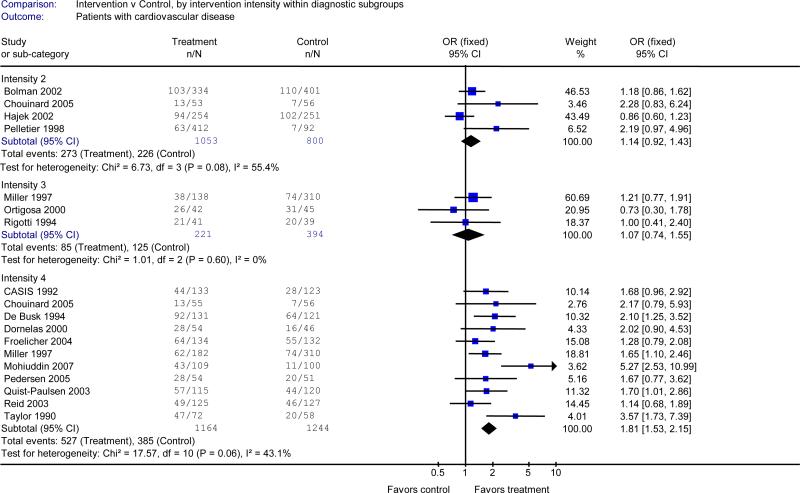

Eighteen studies limited enrollment to smokers with a cardiovascular admitting diagnosis. 6, 9, 10, 12-14, 18, 19, 21, 23, 25, 27, 28, 30, 32, 38-40 The result of this subgroup analysis resembled the main analysis. There was a significant effect on quitting in the pooled analysis of 11 studies testing the most intensive intervention (intensity 4, OR 1.81, 95% CI 1.53-2.15) 6, 9, 10, 12, 14, 18, 21, 23, 25, 30, 32, but not for studies testing less intensive interventions (Table 2B).

Four studies enrolled only patients with respiratory admitting diagnoses.14, 28, 29, 35 None of the studies found a significant effect of the interventions tested. We did not estimate a pooled effect because the interventions were heterogeneous. One very small pilot study tested a hospital intervention for patients with cancer 36 and found no evidence of efficacy.

Comment

This systematic review finds that smoking cessation counselling that begins during hospitalization and provides supportive contacts for over 1 month after discharge increases the odds of smoking cessation by 65% at 6-12 months over what is achieved by hospitalization alone. There is no evidence that less intensive counselling interventions, particularly those that do not continue after hospital discharge, are effective in promoting smoking cessation. The intensive counselling intervention is effective when provided to all hospitalized smokers, regardless of admitting diagnosis.

These finding were robust, remaining statistically significant in a series of sensitivity analyses that excluded studies of lower methodological quality and studies that that allowed the use of NRT as part of the intervention, only enrolled smokers who planned to quit, or included recent quitters along with current smokers. While only 5 of the 17 studies with the sustained intervention continuing for over 1 month after discharge found a significant intervention effect, once they are pooled, the actual impact of this level of intervention is substantial, increasing the odds of quitting by 65%. The effect sizes observed in all these studies may be artificially modest because in many cases the “control” condition was more intensive than usual care or simply brief advice. However, even relatively modest effects can have substantial public health impact when applied at the population level.

While the analysis supports providing the counselling intervention to all hospitalized smokers, it also demonstrates strong benefit for smokers who are admitted for cardiovascular disease. This subgroup of smokers generally achieved higher absolute cessation rates than did smokers in studies that included a broad range of diagnoses. In the pooled analysis, the relative effect of the intensive counselling intervention for patients admitted with cardiovascular diagnoses (OR 1.81, 95% CI 1.53-2.15) was slightly higher than it was when provided to all patients (OR 1.43, 95% CI 1.17-1.75), but the confidence limits overlapped, precluding a conclusion that the relative effect is larger for patients with cardiovascular disease. There is insufficient evidence to conclude that counselling interventions are effective for smokers admitted to hospital with a respiratory diagnosis. However, there is no reason to exclude this group of smokers in interventions that target all hospitalized smokers, which have a strong evidence base.

The effect of pharmacotherapy in hospitalized patients was more difficult to assess because NRT and bupropion have only been tested along with counselling. Adding NRT to counselling in hospitalized smokers produced a 47% increase in the odds of quitting compared to placebo or no drug in the pooled analysis. Although this was not statistically significant (OR 1.47, 95% CI 0.92 to 2.35), there was a clear trend, and the odds ratio and confidence limits were compatible with the effect of NRT in other settings.42 Furthermore, NRT is used in hospitalized smokers to treat acute nicotine withdrawal symptoms as well as to promote smoking cessation. Overall, these data support including NRT in interventions for hospitalized smokers.

The evidence regarding the benefit of adding bupropion to counselling in hospitalized patients is limited to one study, in which bupropion was not more effective than placebo.27 However, the confidence limits were broad and the effect size was consistent with evidence from other populations that bupropion is effective for smoking cessation.43 No trial has assessed varenicline, a newer smoking cessation drug, in the hospital setting.

The existing evidence provides stronger support for the benefit of counselling than for pharmacotherapy. In part, this reflects a smaller evidence base of trials testing pharmacotherapy in the hospital setting. Furthermore, counseling and pharmacotherapy may be synergistic. In addition to providing psychological support to quitting, counselling after discharge may also help increase quit rates by improving adherence to cessation medications that were started in the hospital. This conclusion is supported by the single study that compared pharmacotherapy alone with pharmacotherapy plus counselling.22 In that study, the addition of counselling to nicotine replacement increased quit rates.

The counselling intervention in these studies was generally delivered by a research nurse or trained smoking cessation counsellor, not by staff responsible for the patients’ clinical care. The effectiveness of these interventions in routine clinical practice, where interventions will be delivered by clinical staff, needs to be demonstrated. The challenge is illustrated by two studies included in this review that provided a similar intervention in a similar setting.11, 20 Counselling was effective when delivered by research staff (masters-level psychologists) in one study but not when delivered by clinical staff (trained respiratory therapists) in the second study.

Determining how to translate these findings effectively and consistently into routine clinical practice is the next task. Studies need to demonstrate the feasibility and effectiveness of hospital-initiated smoking cessation interventions in clinical practice. For example, one of the studies in this review14 was followed by a report that the program's effectiveness was maintained for the 3 years after the end of a clinical trial.44 During that time, approximately half of the admitted smokers accepted the offer of intervention, and those smokers had a cessation rate comparable to that achieved in the randomized trial.

Additional research should assess the cost-effectiveness of the intensive counselling intervention and to explore the impact of counselling on health and healthcare utilization outcomes. One study in this review assessed health care utilization and mortality outcomes in smokers hospitalized with cardiovascular disease.6 The intervention produced a large increase in smoking cessation and at two-year follow-up, a substantial decline in hospital readmissions and all-cause mortality. The result was potentially confounded by better blood pressure and cholesterol control and better medication compliance in the intervention group, but it is an example of the type of evidence that could help to promote the broader adoption of hospital-based smoking intervention.

Finally, the results of this review support the JCAHO/CMS decision to include a tobacco measure in the national hospital quality-of-care standards.4 The review provides a rationale for expanding the current measure to apply to all hospitalized smokers, rather than just to smokers with MI, CHF, and pneumonia. It also suggests that the current tobacco measure should be strengthened to include an assessment of whether a smoking intervention begun during a hospital stay is linked to support after discharge. This is essential to ensure that the quality standard achieves the goal of promoting smoking cessation after hospital discharge.

Figure 1.

Efficacy of smoking cessation counselling, by intensity of counselling intervention.

Outcome is number quit at longest follow-up (≥6 months) Intensity 1= contact in hospital of ≤ 15 minutes and no post-discharge support. Intensity 2= contact in hospital of >15 minutes and no post-discharge support; Intensity 3= any hospital contact plus post-discharge support lasting ≤1 month. Intensity 4=any hospital contact plus post-discharge support lasting >1 month. I2 measures statistical heterogeneity among studies.8

Figure 2A.

Efficacy of smoking cessation counselling, by intensity of counselling, in studies that enrolled hospitalized smokers with all admission diagnoses

Outcome: number quit at longest follow-up (≥6 months). See Figure 1 legend for definition of levels of counselling intensity. I2 measures statistical heterogeneity among studies.8

Figure 2B.

Efficacy of smoking cessation counselling, by intensity of counselling, in studies that enrolled patients who were admitted for cardiovascular disease.

Outcome: number quit at longest follow-up (≥6 months). See Figure 1 legend for definition of levels of counselling intensity. I2 measures statistical heterogeneity among studies.8

Figure 3.

Efficacy of adding smoking cessation pharmacotherapy to counselling.

Outcome: number quit at longest follow-up (≥6 months). NRT=nicotine replacement therapy. I2 measures statistical heterogeneity among studies.8

Acknowledgements

Funding: The Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Review Group is supported by the National Health Service of the United Kingdom. Dr. Rigotti was supported by a Midcareer Investigator Award in Patient Oriented Research from the NIH/NHLBI (#2 K24 HL04440).

Footnotes

Presented in abstract form at the Annual Meeting of the Society for Research in Nicotine and Tobacco–Europe, Madrid, Spain, October 5, 2007

Potential conflict of interest

Dr Rigotti was the co-author of three studies included in the review. Dr. Rigotti's research is funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health, by private nonprofit foundations, and by the pharmaceutical companies that make investigational or approved smoking cessation products.

REFERENCES

- 1.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . The health consequences of smoking: A report of the surgeon general. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; Atlanta, GA: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . Reducing tobacco use: A report of the surgeon general. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; Atlanta, GA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Longo DR, Brownson RC, Kruse RL. Smoking bans in US hospitals. results of a national survey. JAMA. 1995;274:488–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations . A comprehensive review of development and testing for national implementation of hospital core measures. [September, 2007]. Available at: http://www.jointcommission.org/NR/rdonlyres/48DFC95A-9C05-4A44-AB05-1769D5253014/0/AComprehensiveReviewofDevelopmentforCoreMeasures.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [September 6, 2007];Hospital compare- a quality tool for adults, including people with medicare. Available at: http://www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov/Hospital.

- 6.Mohiuddin SM, Mooss AN, Hunter CB, Grollmes TL, Cloutier DA, Hilleman DE. Intensive smoking cessation intervention reduces mortality in high-risk smokers with cardiovascular disease. Chest. 2007;131:446–452. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yusuf S, Peto R, Lewis J, Collins R, Sleight P. Beta blockade during and after myocardial infarction: An overview of the randomized trials. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1985;27:335–371. doi: 10.1016/s0033-0620(85)80003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taylor CB, Houston-Miller N, Killen JD, DeBusk RF. Smoking cessation after acute myocardial infarction: Effects of a nurse-managed intervention. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113:118–123. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-2-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ockene J, Kristeller JL, Goldberg R, et al. Smoking cessation and severity of disease: The coronary artery smoking intervention study. Health Psychol. 1992;11:119–126. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.11.2.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stevens VJ, Glasgow RE, Hollis JF, Lichtenstein E, Vogt TM. A smoking-cessation intervention for hospital patients. Med Care. 1993;31:65–72. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199301000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeBusk RF, Miller NH, Superko HR, et al. A case-management system for coronary risk factor modification after acute myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120:721–729. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-120-9-199405010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rigotti NA, McKool KM, Shiffman S. Predictors of smoking cessation after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. results of a randomized trial with 5-year follow-up. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120:287–293. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-120-4-199402150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller NH, Smith PM, DeBusk RF, Sobel DS, Taylor CB. Smoking cessation in hospitalized patients. results of a randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:409–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rigotti NA, Arnsten JH, McKool KM, Wood-Reid KM, Pasternak RC, Singer DE. Efficacy of a smoking cessation program for hospital patients. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:2653–2660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simon JA, Solkowitz SN, Carmody TP, Browner WS. Smoking cessation after surgery. A randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:1371–1376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lewis SF, Piasecki TM, Fiore MC, Anderson JE, Baker TB. Transdermal nicotine replacement for hospitalized patients: A randomized clinical trial. Prev Med. 1998;27:296–303. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1998.0266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dornelas EA, Sampson RA, Gray JF, Waters D, Thompson PD. A randomized controlled trial of smoking cessation counseling after myocardial infarction. Prev Med. 2000;30:261–268. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moreno Ortigosa A, Ochoa Gomez FJ, Ramalle-Gomara E, Saralegui Reta I, Fernandez Esteban MV, Quintana Diaz M. Efficacy of an intervention in smoking cessation in patients with myocardial infarction. Med Clin (Barc) 2000;114:209–210. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7753(00)71246-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stevens VJ, Glasgow RE, Hollis JF, Mount K. Implementation and effectiveness of a brief smoking-cessation intervention for hospital patients. Med Care. 2000;38:451–459. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200005000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quist-Paulsen P, Gallefoss F. Randomised controlled trial of smoking cessation intervention after admission for coronary heart disease. BMJ. 2003;327:1254–1257. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7426.1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simon JA, Carmody TP, Hudes ES, Snyder E, Murray J. Intensive smoking cessation counseling versus minimal counseling among hospitalized smokers treated with transdermal nicotine replacement: A randomized trial. Am J Med. 2003;114:555–562. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(03)00081-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sivarajan Froelicher ES, Miller NH, Christopherson DJ, et al. High rates of sustained smoking cessation in women hospitalized with cardiovascular disease: The women's initiative for nonsmoking (WINS). Circulation. 2004;109:587–593. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000115310.36419.9E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hasuo S, Tanaka H, Oshima A. Efficacy of a smoking relapse prevention program by postdischarge telephone contacts: A randomized trial. Nippon Koshu Eisei Zasshi. 2004;51:403–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chouinard MC, Robichaud-Ekstrand S. The effectiveness of a nursing inpatient smoking cessation program in individuals with cardiovascular disease. Nurs Res. 2005;54:243–254. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200507000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hennrikus DJ, Lando HA, McCarty MC, et al. The TEAM project: The effectiveness of smoking cessation intervention with hospital patients. Prev Med. 2005;40:249–258. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rigotti NA, Thorndike AN, Regan S, et al. Bupropion for smokers hospitalized with acute cardiovascular disease. Am J Med. 2006;119:1080–1087. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Campbell IA, Prescott RJ, Tjeder-Burton SM. Smoking cessation in hospital patients given repeated advice plus nicotine or placebo chewing gum. Respir Med. 1991;85:155–157. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(06)80295-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Campbell IA, Prescott RJ, Tjeder-Burton SM. Transdermal nicotine plus support in patients attending hospital with smoking-related diseases: A placebo-controlled study. Respir Med. 1996;90:47–51. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(96)90244-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pedersen L, Johansen S, Eksten L. Smoking cessation among patients with acute heart disease. A randomised intervention project. Ugeskr Laeger. 2005;167:3044–3047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vial RJ, Jones TE, Ruffin RE, Gilbert AL. Smoking cessation program using nicotine patches linking hospital to the community. Journal of Pharmacy Practice and Research. 2002;32:57–62. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reid R, Pipe A, Higginson L, et al. Stepped care approach to smoking cessation in patients hospitalized for coronary artery disease. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2003;23:176–182. doi: 10.1097/00008483-200305000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Molyneux A, Lewis S, Leivers U, et al. Clinical trial comparing nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) plus brief counselling, brief counselling alone, and minimal intervention on smoking cessation in hospital inpatients. Thorax. 2003;58:484–488. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.6.484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nagle AL, Hensley MJ, Schofield MJ, Koschel AJ. A randomised controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy of a nurse-provided intervention for hospitalised smokers. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2005;29:285–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2005.tb00770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pederson LL, Wanklin JM, Lefcoe NM. The effects of counseling on smoking cessation among patients hospitalized with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A randomized clinical trial. Int J Addict. 1991;26:107–119. doi: 10.3109/10826089109056242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Croghan G, Croghan I, Frost M, et al. Smoking cessation interventions and postoperative outcomes in esophageal and lung cancer patients.. Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco 11th Annual Meeting; Prague, Czech Republic. March 20-23, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Feeney GF, McPherson A, Connor JP, McAlister A, Young MR, Garrahy P. Randomized controlled trial of two cigarette quit programmes in coronary care patients after acute myocardial infarction. Intern Med J. 2001;31:470–475. doi: 10.1046/j.1445-5994.2001.00110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hajek P, Taylor TZ, Mills P. Brief intervention during hospital admission to help patients to give up smoking after myocardial infarction and bypass surgery: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2002;324:87–89. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7329.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pelletier JG, Moisan JT. Smoking cessation for hospitalized patients: A quasi-experimental study in quebec. Can J Public Health. 1998;89:264–269. doi: 10.1007/BF03403933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bolman C, de Vries H, van Breukelen G. A minimal-contact intervention for cardiac inpatients: Long-term effects on smoking cessation. Prev Med. 2002;35:181–192. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2002.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hughes JR, Keely JP, Niaura RS, Ossip-Klein DJ, Richmond RL, Swan GE. Measures of abstinence in clinical trials: Issues and recommendations. Nicotine Tob Res. 2003;5:13–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Silagy C, Lancaster T, Stead L, Mant D, Fowler G. Nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(3):CD000146. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000146.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hughes JR, Stead LF, Lancaster T. Antidepressants for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(1):CD000031. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000031.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smith PM, Reilly KR, Houston Miller N, DeBusk RF, Taylor CB. Application of a nurse-managed inpatient smoking cessation program. Nicotine Tob Res. 2002;4:211–222. doi: 10.1080/14622200210123590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]