Abstract

Recess plays an integral role in the social and emotional development of children given the time provided to engage in interactions with others and practice important social skills. Students with ASD, however, typically fail to achieve even minimal benefit from recess due to social and communication impairments as well as a tendency to withdraw. Implementation of evidence-based interventions such as peer-mediated social skills groups, are necessary to ensure recess is an advantageous learning environment for students with ASD. A multiple-baseline design across participants was used to determine if a functional relationship exists between a social skills instructional program combined with peer networks with school staff as implementers and increases in level of communicative acts for participants with ASD at recess. Results indicate all participants demonstrated an immediate increase in the number of communicative acts with the introduction of the intervention. Implications for practice are discussed.

Keywords: Autism Spectrum Disorders, Elementary School, Intervention, Recess, Social Skills, Communication

1. Introduction

The American Academy of Pediatrics recently issued a policy statement on the importance of school recess (www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2012-2993) stating, “Recess promotes social and emotional learning and development for children by offering them a time to engage in peer interactions in which they practice and role play essential social skills.” This type of activity, under adult supervision, extends teaching in the classroom to augment the school’s social climate. Through play at recess, children learn valuable communication skills, including negotiation, cooperation, sharing, and problem solving as well as coping skills, such as perseverance and self-control. These skills become fundamental, lifelong personal tools.” (p.184). This policy statement was issued in reaction to the debate over the role of schools in promoting development of the whole child, and with the increasing pressure to accelerate academic performance which may often preclude social activities. Despite inclusion in recess activities, students with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), generally miss out on the social benefits specific to recess.

ASDs are defined as a group of developmental disabilities characterized by impairments in social interaction and communication and by restricted, repetitive, and stereotyped patterns of behavior (American Psychiatric Association, 2012). Other characteristics include lack of responding to their name, poor eye contact, limited affect and social responsiveness, and language delays or deviances (limited words by 16 months, echolalia, perseveration on topics) (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, 2009). Koegel reported that problems engaging in social interactions for children with autism primarily serve two functions: avoidance of social attention (interaction) or seeking social attention but using inappropriate communication to do so (perseverative topics) (Koegel, Openden, Fredeen, & Koegel, 2006). Children with ASD use fewer toys, and less time playing appropriately with toys, demonstrate fewer functional play acts and symbolic play, show less imitation than typical peers and even actively avoid peers (Stone, 1990 cited in Harper et al., 2008). For school aged children these characteristics impact their ability to interact with teachers and peers across a multitude of settings including the classroom, transition areas, lunchroom, and playground.

Interventions that target social and communication skills thus appear to be pivotal to improving their ability to initiate interactions, reciprocate during social exchanges, and infer the interests and emotions of others. Fortunately, research shows increasing evidence for interventions to address these core deficits for children with autism. Kasari, Paparella, Freeman, and Jahromi (2008) and others (Rogers, 2000) report treatment aimed at joint attention and symbolic play as effective for improving social and communication skills with young children with autism. A recent review of social skills interventions (Reichow & Volkmar, 2009) reported peer training, video modeling, and social skills groups as part of a treatment package as evidenced or emerging evidenced-based practices. Peer mediation or peer networks (Haring & Breen, 1992; Kamps, Potucek, Gonzalez-Lopez, Kravits, & Kemmerer, 1997; Kamps et al., 2002) have also been shown effective for improving social and communication skills. Examples include peer dyads or small groups of peers to support a child with ASD or other disability to assist with specific tasks, for example as social and conversation partners, during transitions, as tutors, or providers of social reinforcement. General recommendations for children with ASD include the use of behavioral interventions with a focus on individual needs, responsiveness to intervention, functional outcomes, and generalization of skill use as key indicators of the effectiveness of interventions (Kasari & Lawton, 2010; Koegel, Kuriakose, Singh, & Koegel, 2012; Rao, Beidel, & Murray, 2008). Recommendations also support children with ASD being taught in more naturalistic settings with typical peers to improve social communication and language development (Koegel, Matos-Freden, Lang, & Koegel, 2012; National Research Council, 2001; Reichow & Volkmar, 2010).

1.1. Recess Interventions

A few studies have successfully targeted social behaviors at recess (Harper, Symon, & Frea, 2008). Lang and colleagues (2011) conducted a review of 15 studies that used recess time to teach target behaviors to students with ASD. In several studies, the perseverative interests or preferred activities of the children were incorporated into the recess or social events with improvements in social/play interactions and affect ratings (Baker et al., 1998; Koegel et al., 2012; Licciardello et al., 2008; Machalicek et al., 2009). Machalicek et al., taught three children with ASD to select pictures of preferred equipment to use on the playground and pictures were then used to create an activity schedule. Challenging behavior decreased, and appropriate play increased. Lang and colleagues decreased severe challenging behavior by increasing teacher attention and praise for appropriate behavior during recess (Lang, O’Reilly, Sigafoos, Machalicek, Rispoli, Shogren et al., 2009, reported in Lang et al., 2011). Licciardello et al. also used teaching assistants to prompt and reinforce interactions between the participant and peers during recess for four, 6–8 year old children with autism resulting in increased social initiations and responses. Zanolli, Daggett, and Adams (1996) implemented a priming session in which 2 4-year old children with autism received a dense schedule of reinforcement with few demands just prior to recess. Peers were taught to respond to social initiations resulting in increases in the number and topography of initiations by the children with autism (reported in Lang et al., 2011). Others have incorporated peer training to increase interactions for children with autism at recess. Owen-Deschryver and colleagues taught peers to initiate and respond to the children with ASD and to consider their interests when playing (Owen-Deschryver, Carr, Cale, & Blakely-Smith, 2008). McGee, Almeida, Sulzer-Azaraff, and Feldman (1992) using incidental strategies, taught peers to reinforce initiations for preferred toys, to praise, and to prompt turn taking with improved reciprocal interactions. Gonzalez-Lopez and Kamps (1997) taught peer mentors to give clear simple instructions, to model appropriate social skills, and to praise kindergarten children with ASD. Results indicated improved frequency and duration of social behaviors, and decreases in disruptive behaviors for participants. Others have used structured activities using music (Kern & Aldridge, 2006) and affection activities (McEvoy, Nordquist, Twardosz, Heckman, Wehby, & Denny, 1988) to increase interactions between peers and young children with autism.

Kasari and colleagues used two interventions to improve social skills for children with autism during recess and lunch time (Kasari, Rotheram-Fuller, Locke, & Gulsrud, 2011). The first program consisted of child-assisted direct instruction using role play and practice with an interventionist until skills were mastered. The second was a peer-mediation procedure with the interventionist training peers to engage the children with autism in social interaction and game playing. Skills were selected based on the individual child’s needs and the setting (e.g., entering and sustaining attention in games, maintaining a conversation, game rules, steps for specific activities, good sportsmanship, etc.). Thirty children participated in the ‘child’ intervention and 30 children in the ‘peer mediation’ intervention, with each lasting 6 weeks with 20-min intervention sessions twice each week. Results included improved class-wide-rated social network status (nominations), improved teacher ratings of social skills, and decreased isolation on the playground for the children with autism. Minimal changes were noted in the percent of interactions with joint attention during recess observations for any of the interventions with a 9% increase during follow-up observations for the children in the peer mediation intervention.

The use of Pivotal Response Training (PRT, Koegel, Schreibman, Good, Cerniglia, Murphy, & Koegel, 1989; Koegel et al, 2006; Pierce & Schreibman, 1995) has been used to improve motivation and responding to increase language use and promote positive interactions for children with autism and their peers. Harper and colleagues taught peers to use naturalistic strategies including PRT during recess to increase initiations and play for children with ASD (Harper et al., 2008). Specific skills included gaining attention, varying activities, narrating play, reinforcing attempts, and turn-taking. Peers were taught to demonstrate each skill with 80% accuracy and to demonstrate providing play opportunities with a classmate. Teaching peers to use naturalistic activities increased initiations and number of turn-taking exchanges for two children with autism. One participant improved from baseline levels of 0–1 to 4.8 bids for attention during 10-min probes. The second participant increased from .89 in baseline to 1.9 during the peer condition and to 3.25 during generalization. Turn-taking exchanges were at zero levels in baseline with increases to 9–16 for participant one and to 1–3 for participant two during intervention.

In a recent study Koegel and colleagues implemented PRT strategies with children with ASD and their peers during recess incorporating the child’s choice of activities and peers. This intervention resulted in improvements in the percent of intervals with social engagement. The addition of initiation training however was necessary to promote improvements in initiation behaviors to peers and generalization in social engagement to recesses when the interventionists were not present (Koegel et al., 2012).

McFadden, Kamps, and Heitzman-Powell (2013) similarly found improved social initiations and responses for children with autism in recess settings following implementation of peer training. Children with ASD and their classmates received training (modeling, priming, prompting, and feedback) in four key skills: (a) playing together and having fun, (b) complimenting and encouraging our friends, (c) talking about what we’re doing and giving ideas, and (d) using names and getting attention. A token system was used during recess to reinforce use of the skills by all participants. The percent of intervals with initiations and/or responses to peers increased from baseline to the peer networks condition for all four participants with ASD (i.e., 9% to 77%, 26% to 81%, 35% to 85%, and 15% to 77%, respectively).

Findings for peer mediated interventions at recess for children with ASD are encouraging but the literature is quite sparse, particularly in elementary school settings. Additional research is needed with well-defined interventions, fidelity of treatment measures, and interventions that are deliverable by school personnel.

1.2 Purpose and Research Questions

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the impact of a peer network package intervention at recess to increase the communicative acts of elementary students with autism spectrum disorder. The specific research question addressed by this study is: Is there a functional relationship between a peer mediated intervention package and increases in the number of communicative acts for participants with ASD at recess?

2. Method

2.1. Participants, Setting and Materials

2.1.1. Participants

Three children diagnosed with autism were chosen from a larger pool of participants who were enrolled in a randomized control trial evaluating the effectiveness of peer networks, following university Institutional Review Board approval for human subjects’ research. Inclusion in the study required a diagnosis of ASD which had previously been determined through educational and/or clinical based assessments. Additional criteria for inclusion in the study included some verbal functional communication including making requests and utilizing 2–3 word phrases as well as the ability to understand and respond to requests and directions. The Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS: Schopler, Reichler, & Renner, 1986) was administered prior to inclusion in the study to confirm the participants met the diagnostic criteria as well as to obtain a measure of severity. Additionally, the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test – 4th Edition (PPVT-4; Dunn & Dunn, 2007) and the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales – Second Edition (VABS-II; Sparrow, Balla, & Cicchetti, 1984) were completed to obtain additional measures of current verbal and social skill levels. The VABS-2 also provided a measure of the overall level of adaptive functioning for the participants. Measures of intellectual functioning level were not available nor administered for the purposes of this study. Descriptive information and assessment results for each participant can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant information

| Participant | Gender | Age | CARS | PPVT | Vineland | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Communication | Adaptive Composite | |||||

| Sam | M | 8 | 35 | 86 | 136 | 125 |

| Ed | M | 6 | 34 | 103 | 95 | 56 |

| Brian | M | 6 | 35 | 92 | 70 | 92 |

Note: CARS – all participants scored in the mild/moderate range of autism; PPVT – all participants scored in the average range; Vineland score descriptions: High – 130 and above, Moderately High – 115–129, Adequate – 86–114, Moderately Low – 71–85, and Low – 70 and belowAll participants had received a peer-mediated social skills intervention. The intervention, which involved a brief lesson about engaging in conversations with peers during play, included visual cues of possible comments and reinforcement for responding and initiating during a structured play activity. Peers were trained to interact with the participants with ASD and prompt the participants to respond and/or initiate communication. The focus of the social skills lessons was “asking and telling about” toys. Participant 1, Sam, was an 8 year old, second grade male student. His receptive language and academic skills were average to above average. During recess, he would attempt to be a part of the group, however he struggled with how to communicate to his peers and rarely initiated peer verbal interaction or responded to their comments.

Participant 2, Ed, was a 7 year old, first grade male who spent the majority of the day in the general education class with the exception of speech therapy. He was verbal, with age-appropriate cognitive skills. Although he was involved in the social skills intervention as described earlier, and making progress on increasing communicative acts during structured social skills groups, he did not initiate social interactions with peers and remained aloof during recess. He would wander the peripheral of the playground, and engaged in make-believe conversations about topics such as pirates. This involved lengthy self-talk, however he did not ever engage peers. Occasionally, he would comment to teachers and other school staff.

Participant 3, Brian, was a 6-year old male diagnosed with autism. His expressive and receptive language abilities were moderately low and he often perseverated on topics of interest. At recess with his first-grade peers, he was accompanied by either his special education teacher or a classroom paraprofessional. During baseline observations, he typically stayed close to his teacher or paraprofessional and rarely engaged with his peers. He would often try to get back into the building or would run to a corner of the playground away from peers or playground equipment. When his teachers prompted him to engage with recess activities or social interactions, he would often respond with physical aggression including hitting, kicking, and pushing.

Four to six neuro-typical peers from each participant’s classroom, who had participated in the initial peer network program were recruited to participate in the recess study. As the peers had previous experience with peer network training, they all had received initial training on prompting procedures. Despite this previous training in a structured setting and that the participants were familiar with the peers at recess as they were from each participant’s general education class, trained interactions did not generalize to settings outside of the structured social skills setting including recess.

2.1.2. Interventionists

The intervention was implemented by typical school staff trained in the scripted procedure for the recess intervention, with the exception of Participant 3. Due to some extraneous circumstances at school, including a new teacher, a member of the research team was the implementer for him. The speech-language pathologist for Participant 2 and a paraprofessional for Participant 3 implemented the recess intervention. Both school-based implementers had previously been trained in the peer network intervention during a 3-hour workshop and had practice implementing this program. As the procedures for the recess intervention was very similar, the process was explained to the interventionists and modeled by research staff. Interventionists were provided with the necessary teaching materials. Performance feedback regarding fidelity of implementation continued as the study proceeded.

2.1.3. Setting and Materials

All sessions took place during recess on the playground that the participants’ class typically used for recess. All playgrounds included concrete areas for playing kickball and foursquare. In addition, swings and playscapes were present. There were also grassy areas in which a ball game, such as soccer or kickball, occurred.

Additional materials included a visual cue card, token card, and a treasure “box.” The visual cue card had the name of the skill (ex. Talk and Share) in addition to an assortment of phrases that could be utilized during recess play such as “Here you go,” “May I have it, “Go” and “Thank you.” The lower half of the card included fill-in-the-blanks so that additional phrases, applicable to the chosen activities, could be added by the participants. The reinforcement card was comprised of 20 blank squares. A dry erase marker was used by the interventionist to make a smiley face or place the initials of the child who commented in a square. The treasure box was filled with small toys, stickers, and trinkets (e.g. erasers, bouncy balls, rings etc.).

2.2. Experimental Design and Measurement

The effect of the intervention was evaluated through the implementation of a multiple-baseline single case design across participants. School-wide events, holidays, and inclement weather caused some variation to the number of sessions delivered per week however, no more than 3 intervention sessions occurred per week. Each session was comprised of an instructional period followed by recess. A member of the research team, trained to reliability in the coding procedure collected data following the instructional period for 10-min recess free play sessions.

2.2.1. Measurement

The dependent measure was the number of communicative acts directed towards a peer. A communicative act was defined as verbal communication clearly directed towards a peer through the use of eye contact, gestures, and/or body orientation. The verbalization must have included a minimum of a meaningful consonant and vowel sound (e.g. “oh”, “ew”). Verbalizations that did not match the current context but were clear attempts to communicate were also coded as a verbalization (e.g. focus child responds to a peer with, “sooo…”, Focus child says, “Greakywish one” and the peer responds, “What”). If the focus child continued to repeat a seemingly nonsensical verbalization, such as “greakywish one,” even if directed towards a peer, it was no longer coded as a verbalization after the third instance. Separate communicative acts were coded for the focus child when a latency of 3 s occurred between the end of a meaningful verbalization and the start of another or when a back-and-forth exchange occurred between the focus child and a peer. For example, if the focus child said, “Can I have the car”, the peer responded with, “Sure”, and the focus child said, “thank you,” 2 communicative acts were coded.

Non-examples of communicative acts included verbal behaviors that were not clearly directed towards a peer through eye contact, body orientation, or gaining attention (e.g. using the person’s name, touching the peer, holding a toy up to direct attention), talking to objects, rotely describing play actions seemingly to no one, and labeling objects. Additionally, communication directed towards an adults were not coded.

Personal digital assistances (PDA) with Noldus Observer XT software (2009) installed were employed by members of the research team, including both investigators and research assistants, to record the frequency count of communicative behaviors during the 10-min observation period.

2.2.2. Reliability

In order to assure accuracy and consistency in coding, inter-rater reliability was collected for a minimum of 20% of data sessions across phases. For the reliability sessions, two trained members of the research team separately, but concurrently, coded the frequency of communicative acts utilizing the Noldus Observer XT (2009) software. Time stamped codes allowed for increased precision in the calculation of inter-observer agreement including nonoccurrence. Agreement was defined as both the primary and secondary observer coding the same number of communicative acts within a 5 s interval. Exact count-per-interval IOA is the most rigorous method for calculating IOA with count measurements (Cooper, Heron, and Heward, 2007). Percent of agreement was calculated by dividing the number of intervals in which there was agreement by the total number of intervals. The overall mean percent of agreement was 85% (range = 82%–90%).

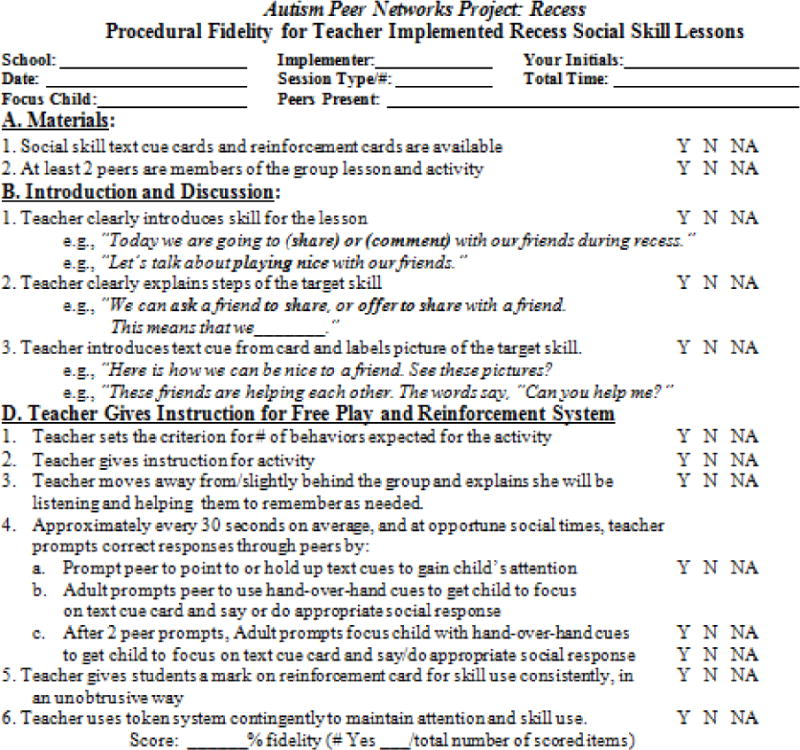

2.2.3. Fidelity of Implementation

A procedural fidelity checklist was completed by trained research staff for 13 of the intervention sessions across participants (see Figure 1). The checklist was comprised of each step of both the instructional and free play procedures including following the script, appropriate levels of prompting, and providing reinforcement. The observer marked “yes” if the step was completed and “no” if the step was not completed. Percent of procedural fidelity was calculated by dividing the number of items completed accurately by the total number of items on the checklist. The mean fidelity of implementation was 94%, ranging from 80% –100%

Figure 1.

Fidelity of Implementation measure for intervention

2.2.4. Social Validity

Each implementer completed a Recess Intervention Satisfaction Survey after the conclusion of the intervention as a measure of social validity. The satisfaction survey was comprised of 6 items that required the implementer to rate the ease of implementation, effectiveness of the intervention in improving participants interactions with trained peers, effectiveness of the intervention in improving participants’ interactions with untrained peers, benefit of the intervention to the peers, enjoyment experienced by both the focus child and the peers in participating in the intervention, and likelihood of continued use of the intervention. For each of the items implementers choose one option: strongly disagree, disagree, somewhat agree, agree, and strongly agree. In addition, the satisfaction survey included three open-ended items to allow the implementers to provide anecdotal information regarding the impact of the intervention. These items included the following: 1) What are some things you really liked or didn’t like about the recess intervention?; 2) What impact do you feel the recess intervention had on the trained peers? Which of these changes continued after the intervention ceased?; 3)What impact do you feel the recess intervention had on the child with autism? Which of these changes continued after the intervention ceased?

2.3. Procedures

2.3.1. Baseline

Baseline data was collected during the focus child’s regular recess. During baseline, the focus child was allowed to play freely without prompting from the research team to interact with others. Peers played freely as well and were not prompted to communicate with the focus child, however they were not discouraged from doing so. Additionally, peers were not prompted to prompt the focus child to communicate.

2.3.2. Intervention

Once the parameters for introducing the independent variable were met, the peer network (PN) recess intervention package was implemented. The intervention began with a priming procedure which involved an introduction of the skill to the focus child and two peers. The interventionist began with, “Today we are going talk and play nice with our friends,” and then explained how this could be done at recess, using several examples, (i.e. “watch this,” “my turn,” “look”). The interventionist then helped the group pick an activity for recess. The interventionist then asked, “What are some things we can say to talk, share, and play nice with our friends?” As members of the group gave responses, the interventionist affirmed good examples by saying things such as, “That’s right, you could say…” and wrote the examples on the blank cue card. If a participant, either the focus child or peer, provided a non-example, the interventionist provided a correction such as, “No that’s not about playing at recess. What else could you say when playing [chosen activity]”. The non-examples were not written on the cue card. Following this the interventionist showed the group the reinforcement card, which consisted of 20 blank squares, and informed them that they would receive a smiley face every time the skill was used, noting that if all 20 squares had a smiley face at the end of recess all group members could choose an item from the treat bag. The interventionist explained that he/she would be listening and helping them to remember to “talk, share, and play nice.” The group was then instructed to play.

While the group was playing, the interventionist moved away from the group. Behavior specific verbal praise was intermittently provided when the focus child correctly delivered a communicative act towards a peer (i.e. eye contact, body orientation, and on topic verbalization). Approximately every 30 s and at opportune social times, if the focus child did not initiate a communicative act, the interventionist would prompt one of the peers to prompt the focus child by pointing to the cue card, verbally saying, “Say…”, and/or using hand-over-hand prompts to get the focus child to point at the text cues and “say or do” the text prompt. If the focus child did not respond after 2 prompts from the peer, the interventionist prompted the focus child.

Following the 10minutes of play, the interventionist offered verbal praise to the group for utilizing the skill, mentioning specific communicative acts that occurred. The reinforcement card was then reviewed and if the pre-established criterion was achieved, each member of the group was allowed to choose a reward from the treat bag.

2.4. Data Analysis

Visual and statistical analyses were implemented to assess the magnitude of change that occurred in the amount of communicative acts emitted by the focus child. For visual analysis, the graphical display of data was examined for changes in variability, mean, and trend. Tau, an effect size suitable for single-case designs (Parker & Vannest, 2012), was calculated to provide a quantified measure of the change that occurred between baseline and intervention. Tau is calculated by comparing each data point in the baseline phase to each data point in the intervention phase to obtain the proportion of all pairs that do not overlap (Parker, Vannest, & Davis, 2011). Tau was calculated between each participant’s baseline and intervention phase. Tau effect size from 0–.49 are interpreted as minimal to no change, whereas Tau measures of .5–.69 are interpreted as moderate and those from .7–1 are interpreted as large (Parker et al., 2011) Each resulting effect size was then combined to obtain an overall Tau for the study.

3. Results

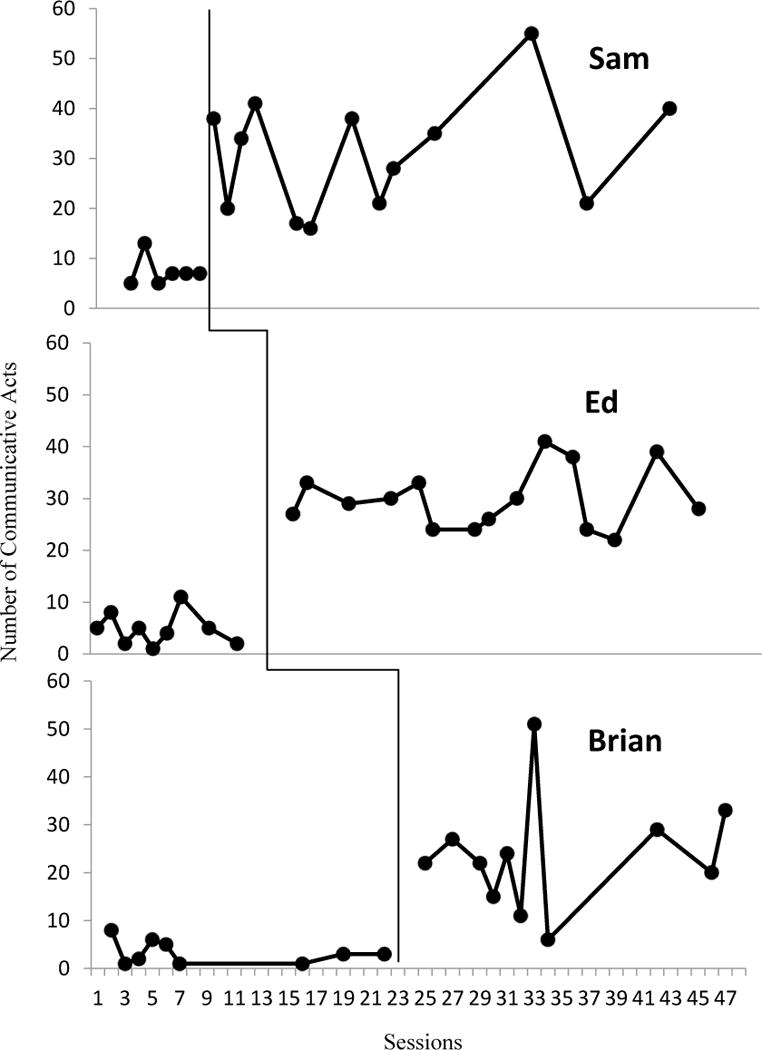

3.1. Intervention

Figure 2 is a graphical display of participants’ data. The y-axis indicates the number of communicative acts per 10-min session. The x-axis indicates the session number. The intervention was methodically introduced across the three participants beginning with Sam (top panel of Figure 2). The study demonstrates experimental control as is evident by systematic introduction of the intervention, three demonstrations of change at different points in time, and immediate increase in communicative acts across all participants (Kratochwill, 2010).

Figure 2.

Graphical display of participants communicative acts for baseline and intervention sessions

Visual analysis of baseline data for Sam indicates a low rate of communicative acts (mean = 7, range 5–13) during the 10-min observation period. Onset of the intervention yielded an immediate increase in communicative acts (mean = 31, range 16–55) directed towards peers. Although visual analysis indicates variability during intervention, the data does not overlap with baseline. Statistical analysis indicates a large magnitude of change (Tau = 1.00) between baseline and intervention (Table 2).

Table 2.

Participant’s Tau effect size and relevant confidence intervals.

| Participant | Tau Effect Size | P-value | 90% CI

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limit | Upper Limit | |||

| Sam | 1.00 | <.00 | .52 | 1.2 |

| Ed | 1.00 | <.00 | .59 | 1.4 |

| Brian | .97 | <.00 | .53 | 1.4 |

| Combined | .99 | .000 | .74 | 1.2 |

The peer networks recess intervention was introduced for Ed following a notable increase in the target behavior for Sam and stable baseline data. As is evident through visual analysis, Ed’s frequency of communicative acts was low and variable (range = 1–11) during baseline. Visual analysis (Figure 2) indicates an immediate mean shift in the frequency of communicative acts with the introduction of the intervention. The mean frequency of communicative acts increased from 4.8 in baseline to 29.9 during intervention. As is visually evident the frequency of communicative acts varied from session to session (range = 22–41), however, there is no overlap of intervention data with baseline data. The resulting Tau (1.00) again indicates a large, magnitude of change with the implementation of the peer network intervention.

Following a clear response from the intervention for Ed and a stable baseline for Brian, Brian was introduced to the intervention. As is evident from review of Figure 2, Brian had a stable, low rate of responding during baseline (mean = 3.8, range 1–8). Brian refused to interact during recess either standing close to the building or eloping from the playground to areas around the school. Introduction of the intervention resulted in an immediate and substantial increase in communicative acts. Brian’s mean frequency of communicative acts increased to an average of 23.6 (range = 6–51). Visual analysis of the data does indicate variability however, overlap with baseline is limited to one data point. The obtained Tau effect size (.97) indicates a large increase in communicative acts from baseline to intervention.

To obtain an overall effect size across all three participants, the individual Tau effect sizes were statistically aggregated, yielding an average weighted Tau. The obtained overall effect size, Tau= .99 (see Table 2) across the three participants indicates a large, statistically significant, magnitude of change between baseline and intervention phases.

3.2 Social validity

All three school-based implementers of the peer mediated intervention completed the Recess Implementer Satisfaction Survey. As previously noted, the implementers for Sam and Ed remained the same throughout the duration of the study, whereas Brian had a change in teacher and, thus implementer, halfway through the study. All 3 raters indicated they agreed to strongly agreed that they observed positive changes in social interactions between the children with autism and their trained peers and that the participants, both the child with autism and the peers, enjoyed and looked forward to the participating in the recess group. Ed’s implementer responded, “I feel that it helped them to be more inclusive in their games and assisted them in their conversations with their peers.” Brian’s implementer indicated the trained peers enjoyed helping and it seemed to “gain self-esteem.” Sam and Ed’s implementers indicated they agreed to strongly agreed, whereas Brian’s implementer indicated she somewhat agreed that: the intervention was easy to learn and effective; they observed positive changes in social interactions between the participant an non-trained peers; the intervention was beneficial for the peers without disabilities; all seemed to enjoy and look forward to participating in the recess group; and they would continue to support or use this intervention in the future.

Although Brian’s implementer noted Brian did not continue to interact with his peers at recess after the study ended, Ed and Sam’s implementers indicated continued social interaction with peers at recess. Ed’s implementer noted the peers are more inclusive and continue to assist him. She stated that although Ed used to wander the perimeter of the playground and not interact with others prior to the implementation of the intervention he now plays with other students and joins in group activities. Sam’s implementer also indicated he continues to be interactive at recess, “more so than ever.” Challenges of the intervention indicated by the implementers included modifying the intervention for indoor recess when there was inclement weather and keeping the size of the group manageable as many wanted to play.

4. Conclusion

4.1. Discussion

Social and communication deficits for children with ASD can severely interfere with the ability of children with ASD to benefit from the social opportunities provided in school settings, including recess. Thus the issue for children with ASD is not only inclusion in social activities such as recess, but ensuring that intervention is in place to promote positive social interactions with peers. Although recess is particularly challenging with limited structure and adult supervision, identifying evidence-based practices that can be integrated into this naturalistic setting is important particularly given the benefits of recess in promoting the development of social-emotional skills.

In the current study, three children with ASD participated in peer network intervention at recess two to three times per week. The intervention consisted of multiple components including: selection of peer partners, instruction in social skills with practice at identifying exemplars with peers at the beginning of recess, praise for use of skills during recess activities, prompting peers to engage the children with ASD in play during recess, and use of rewards at the end of the recess session for maintaining social interactions. Results showed improvements in the total communication acts for all three participants. This multiple baseline design study with three systematic demonstrations of change at different points in time contributes to the evidence of the effectiveness of teaching communication skills with trained peer partners in recess settings. These findings support prior recess interventions using direct instruction of social behaviors and peer mediation in recess settings (Harper et al., 2008; Kasari et al., 2011; Owen-Deschryver et al., 2008). The study also directly confirms the benefits of a peer network or small group of identified children to support the children with ASD through prompting and reinforcing use of skills in the natural settings including recess (Gonzalez & Kamps, 1997; Kamps et al., 1997; Koegel et al., 2012; McFadden et al., 2013). The improvements in communication frequency confirm the recommendations by Lang and colleagues “The presence of peers without disabilities on the playground should be seen as a potential instructional asset” (p. 1303). He states that peers may reduce demands on busy teachers, and further that peer mediation fosters inclusion by increasing the number of socially responsive partners, and opportunities to practice skills with multiple people in a natural environment which may promote generalization of skills.

Consistent with several other studies at recess was the need to provide intervention directly in the target setting and with an interventionist present to prompt the peers to keep the child with ASD responsive to the social demands (McFadden et al., 2013; Owen-Deschryver et al., 2008). Anecdotally, the interventionists noted that prompting was needed in order for children to change activities (when it appeared that the child with ASD or peers may have been losing interest), to give ideas on types of comments or encouragement to use to contextually fit a novel activity (i.e., one not previously used in role plays), or to structure the activity to provide interaction and turn taking opportunities. Other variables contributed to the efforts in implementation. Sam and Ed were highly verbal and interested in their peers. Their teachers and our observations suggested that they just needed instruction in how to interact and respond to peers. They appeared motivated to engage with peers, with the use of an incentive program. Brian however, often preferred to be alone and the playground was an easy environment in which to achieve this isolation. He also exhibited frequent behavior problems in his class which sometimes carried over to recess (e.g., running from the interventionist, refusing to respond, perseverating on the same toy or game). His interventionist provided extra supports including frequent visual reminders of the rewards chart, high levels of praise and frequent physical prompting.

Important features of the intervention included typical agents, school staff, as implementers for two of the children, although with fairly consistent coaching from the researchers for Brian. All of the implementers also assisted with a peer-based social skills group. For Sam, the groups had occurred during kindergarten and first grade, with the current intervention in second grade. For Ed, the speech therapist implemented social skills groups two times per week and one to two of the recess interventions each week. Her schedule didn’t permit consistent availability, so the researcher served as interventionist for approximately half of the intervention sessions at recess. For Brian, his speech therapist implemented social groups two times per week, but was unavailable for recess. His resource room teacher was newly appointed as Brian’s teacher and thus needed more frequent coaching in how to use the peer mediated social intervention. In spite of this variability, fidelity of implementation was strong, lending further evidence that the intervention procedures are rather straightforward promoting ease of implementation.

Another important component of the intervention was use of feedback to participants during the sessions in the form of stars or smiley faces on a chart, and access to the treasure box at the end of the recess sessions. Small prizes (e.g., stickers, small tablets, tops, koosh balls, rings) were rewarding to children over the months of the study. Ed’s teacher decided to tie the incentives into the class-wide rewards program. She had the recess peer network members earn tickets matching the class system which were added to the class counts to earn rewards. This allowed special recognition for children participating as ‘recess buddies’.

4.2. Limitations

In spite of positive findings, there are a number of limitations of the study. The small number of participants restricts the generalizability of the findings. In addition, the interventionist’s presence and prompting was not faded and thus maintenance was not addressed in this study. As the intervention incorporated priming through the pre-teaching component and introduction of the reinforcement, the interventionist served as a discriminative stimulus, priming both the peers and target students to engage in interactions with one another. The lack of maintenance data prohibits analysis of whether the communicative behaviors continued without the presence of the interventionist. Additional features to the intervention or more time might have permitted fading of adult assistance. For all three participants, the use of a structured intervention at recess was a novel experience. Anecdotal data provided by the interventionist several months after the intervention ended did provide some qualitative information that the communicative acts of the participants and interactions with peers did continue after the intervention was withdrawn.

The intervention package consisted of several components including pre-teaching, priming, prompting and reinforcement of communicative acts. This did result in meaningful changes in the number of communicative acts for each participant; however, given the nature of a treatment package, identification of whether or not implementation of just one of the components (e.g. reinforcement) would have yielded the same meaningful change is not feasible. Future research should demonstrate whether or not each component is effective when implemented alone and whether or not the package has added affects above and beyond the individual components.

In addition, there was a great deal of variability in communicative acts across sessions, especially for Sam and Brian. This trend in social data is common across intervention studies for children with autism (e.g., Koegel, Vernon, & Koegel, 2009; Thiemann & Goldstein, 2004), and likely due to a number of variables including activities selected during recess, the opportunity for greater physical movement across large spaces, and different peers in the network on different days.

Finally, additional measures might add to more understanding of the variability of performance and suggestions for future interventions in recess settings. For example, frequency or quality of adult and peer prompts were not measured, nor were inappropriate behaviors or rates of general social engagement assessed.

4.3. Implications for practice

Findings from the study clearly show the benefits of intervention during recess for children with autism. The procedures used in the study further suggest that many practitioners can implement the intervention with positive benefits. First, strategies that comprised the intervention were those commonly used with children with autism including visual text cues, modeling for the children with autism as well as the peers at the beginning of each recess session, prompting during sessions to promote continued engagement, and frequent reinforcement for skill use. It is likely that many school staff are already trained in the use of these strategies, and with planning and accommodations for individual children, the intervention can be replicated for many children with autism. A dense schedule of reinforcement for children with behavior problems may be necessary as was the case for Brian.

The scheduling of staff time to oversee the intervention will require administrative and team support as supervision is generally limited during recess. Scheduling of multiple peers to participate in the intervention is also important to prevent overuse of a small number of peers. Rotating peers from the same class as well as other classes will prevent this problem and likely increase maintenance of interactions for the children with autism as well. In addition, all the participants in the study were also participating in small social groups at times other than recess with their peers. It may be necessary to first teach use of social skills in smaller controlled settings prior to or concurrently with teaching social behaviors at recess. In general, the study suggests that the allocation of time for staff and involvement of multiple groups of peers during social settings in schools is both necessary and beneficial for improving the social competence for the children with autism.

4.4. Implications for future research

The use of peer networks at recess was shown to be an effective intervention and fairly easy to implement. Children were responsive with general improvements in communication over baseline levels. Peers appeared to be comfortable prompting the children with ASD to be socially engaged. Future research is needed to identify strategies for fading adult assistance, and for maintaining the social interactions and communications between children with ASD and their peers. The contextual variables of playgrounds are challenging however and continued interventionist presence may be necessary for the improved social behaviors to be sustained. Additional areas of study might include environmental structures (e.g., types of games, activities that promote increased cooperative play at recess), priming and initiation strategies, and the use of self-management strategies for the children with ASD.

Acknowledgments

The research was funded by the Institute of Education Sciences, Department of Education (R324A090091). Opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the funding agency. We gratefully acknowledge the participating teachers, students, and families for their time and ongoing support.

Contributor Information

Debra Kamps, Email: dkamps@ku.edu.

Amy Turcotte, Email: amyturcotte@ku.edu.

Suzanne Cox, Email: scox@ku.edu.

Sarah Feldmiller, Email: sfeldmiller@ku.edu.

Todd Miller, Email: Tmiller3@ku.edu.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Baker MJ, Koegel RL, Koegel LK. Increasing the social behavior of young children with autism using their obsessive behaviors. Journal of the Association for Persons with Severe Handicaps. 1998;23(4):300–308. [Google Scholar]

- Constantino J. Social Responsiveness Scale. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper JO, Heron TE, Heward WL. Applied behavior analysis. 2. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Lopez A, Kamps DM. Social skills training to increase social interactions between children with autism and their typical peers. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 1997;12(1):2–14. [Google Scholar]

- Haring TG, Breen CG. A peer-mediated social network intervention to enhance the social integration of persons with moderate and severe disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1992;25(2):319–333. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1992.25-319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper CB, Symon JBG, Frea WD. Recess is time-in: Using peers to improve social skills of children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2008;38(5):815–826. doi: 10.1007/s10803-007-0449-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamps D, Potucek J, Gonzalez-Lopez A, Kravits T, Kemmerer K. The use of peer networks across multiple settings to improve interaction for students with autism. Journal of Behavioral Education. 1997;7:335–357. [Google Scholar]

- Kamps D, Royer J, Dugan E, Kravits T, Gonzalez-Lopez A, Garcia J, Garrison-Kane L. Peer training to facilitate social interaction for elementary students with autism and their peers. Exceptional Children. 2002;68(2):175–187. [Google Scholar]

- Kasari C, Lawton K. New directions in behavioral treatment of autism spectrum disorders. Current Opinions in Neurology. 2010;23(2):137–143. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e32833775cd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasari C, Locke J, Gulsrud A, Rotheram-Fuller E. Social networks and friendships at school: Comparing children with and without ASD. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2011;41(5):533–544. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-1076-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasari C, Paparella T, Freeman S, Jahromi LB. Language outcome in autism: Randomized comparison of joint attention and play interventions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008:125–137. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasari C, Rotheram-Fuller E, Locke J, Gulsrud A. Making the connection: Randomized controlled trial of social skills at school for children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2012;53(4):431–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02493.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern P, Aldridge D. Using embedded music therapy interventions to support outdoor play of young children with autism in an inclusive community-based child care program. Journal of Music Therapy. 2006;43(4):270–294. doi: 10.1093/jmt/43.4.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koegel LK, Kuriakose S, Singh AK, Koegel RL. Improving generalization of peer socialization gains in inclusive school settings using initiations. Behavior Modification. 2012;36(3):361–377. doi: 10.1177/0145445512445609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koegel LK, Matos-Freden R, Lang R, Koegel RL. Interventions for children with autism in inclusive school settings. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2012;19:401–412. [Google Scholar]

- Koegel R, Openden D, Fredeen R, Koegel L. The basics of pivotal response treatment. In: Koeger R, Koegel L, editors. Pivotal Response Treatments for Autism: Communication, Social, and Academic Develoment. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co; 2006. pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Koegel LK, Vernon TW, Koegel RL, Koegel BL, Paullin AW. Improving social engagement and initiations between children with autism spectrum disorders and their peers in inclusive settings. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2012;14(4):220–227. doi: 10.1177/1098300712437042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koegel RL, Schreibman L, Good A, Cerniglia L, Murphy C, Koegel LK. How To Teach Pivotal Behaviors to Children with Autism: A Training Manual. Santa Barbara, CA: University of California; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Koegel RL, Vernon T, Koegel LK. Improving social initiations in young children with autism using reinforcers with embedded social interactions. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2009;39:1240–1251. doi: 10.1007/s10803-009-0732-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kratochwill TR, Hitchcock J, Horner RH, Levin JR, Odom SL, Rindskopf DM, Shadish WR. Single-Case design technical documentation. Single-case designs technical documentation. 2010 Retrieved from What Works Clearinghouse website: http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/pdf/wwc_scd.pdf.

- Lang R, Kuriakose S, Lyons G, Mulloy A, Boutot A, Britt C, Caruthers S, Ortega L, O’Reilly M, Lancioni G. Use of school recess time in the education and treatment of children with autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2011;5:1296–1305. [Google Scholar]

- Lang R, O’Reilly MF, Sigafoos J, Machalicek W, Rispoli M, Shogren K, Hopkins S. Review of teacher involvement in the applied intervention research for children with autism spectrum disorders. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disability. 2010;45:268–283. [Google Scholar]

- Licciardello C, Harchik A, Luiselli J. Social skills interventin for children with autism during interactive play at a public elementary school. Education and Treatment of Children. 2008;31:27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Risi S, Lambrecht LEC, Leventhal BL, DiLavore PC, Rutter M. The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule–Generic: A Standard Measure of Social and Communication Deficits Associated with the Spectrum of Autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2000;30(3):206–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Rutter M, DiLavore PC. Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule – Generic. Chicago, IL: Department of Psychiatry, University of Chicago; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Machalicek W, O’Reilly M, Chan J, Rispoli M, Lang R, Davis T, Langthorne P. Using video conferencing to support teachers to conduct preference assessments with students with autism and developmental disabilities. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2009;3:32–41. [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy MA, Nordquist VM, Twardosz S, Heckaman KA, Wehby JH, Denny RK. Promoting autistic children’s peer interaction in an integrated early childhood setting using affection activities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1988;21:193–200. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1988.21-193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFadden B, Kamps D, Heitzman-Powell L. The Effects of a Peer-mediated social skills intervention on the social communication behavior of children with autism at recess. 2013. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGee GG, Almeida MC, Sulzer-Azaroff B, F RS. Promoting reciprocal interactions via peer incidental teaching. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1992;25:117–126. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1992.25-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. NINDS Autism Information Page. 2009 http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/autism/autism.htm.

- National Research Council. Educating Children with Autism. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. Committee on Educational Interventions for Children with Autism Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. [Google Scholar]

- NOLDUS: The Observer XT: The NeXT Generation of Observation Software. Wageningen, The Netherlands: Noldus Information Technology; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Owen-Deschryver JS, Carr EG, Cale SI, Blakeley-Smith A. Promoting social interactions between students with autism spectrum disorders and their peers in inclusive school settings. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 2008;26(3):131–142. [Google Scholar]

- Parker RI, Vannest KJ. Bottom up analysis of single-case research designs. Journal of Behavioral Education. 2012;21(3):254–265. [Google Scholar]

- Parker RI, Vannest KJ, Davis JL. Effect size in single-case research: A review of nine nonoverlap techniques. Behavior Modification. 2011;35(4):303–322. doi: 10.1177/0145445511399147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce K, Screibman L. Increasing complex social behaviors in children with autism: Effects of peer-implemented pivotal response training. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1995;28(3):285–295. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1995.28-285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao P, Beidel D, Murray M. Social skills interventions for children with Asperger’s Syndrome or high-functioning autism: A review and recommendations. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2008;38(2):353–361. doi: 10.1007/s10803-007-0402-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichow B, Volkmar F. Social skills interventions for individuals with autism: Evaluation for evidence-based practices within a best evidence synthesis framework. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2009;40(2):149–166. doi: 10.1007/s10803-009-0842-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers SJ. Interventions that facilitate socialization in children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2000;30:399–409. doi: 10.1023/a:1005543321840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schopler E, Reichler RJ, Renner BR. The Childhood Autism Rating Scale. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow SS, Balla DA, Cicchetti DV. The Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service, Inc; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Stone WL, Caro-Martinez LM. Naturalistic observations of spontaneous communication in autistic children. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1990;20:437–453. doi: 10.1007/BF02216051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiemann KS, Goldstein H. Effects of peer training and written text cueing on social communication of school-age children with pervasive developmental disorder. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2004;41(1):126–144. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2004/012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanolli K, Dagget J, Adams T. Teaching preschool age autistic children to make spontaneous initiations to peers using priming. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1996;26(4):407–422. doi: 10.1007/BF02172826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]