Significance

To meet environmental and developmental needs, the monolignol biosynthetic pathway for lignification in plant cell walls is regulated by complex mechanisms involving transcriptional, posttranscriptional, and metabolic controls. However, posttranslational modification by protein phosphorylation had not been demonstrated in the regulation of monolignol biosynthesis. Here, we show that reversible monophosphorylation at Ser123 or Ser125 acts as an on/off switch for the activity of 5-hydroxyconiferaldehyde O-methyltransferase 2 (PtrAldOMT2). Phosphorylation induces a loss of function of PtrAldOMT2, which directly affects metabolic flux for syringyl monolignol biosynthesis. The Ser123/Ser125 phosphorylation sites are conserved across 98% of AldOMTs from 46 diverse plant species. Protein phosphorylation provides a rapid and energetically efficient mode of regulating PtrAldOMT2 activity for syringyl monolignol biosynthesis and represents an additional level of control for this important pathway.

Keywords: AldOMT, COMT, lignin, phosphoproteomics, phosphoregulation

Abstract

Although phosphorylation has long been known to be an important regulatory modification of proteins, no unequivocal evidence has been presented to show functional control by phosphorylation for the plant monolignol biosynthetic pathway. Here, we present the discovery of phosphorylation-mediated on/off regulation of enzyme activity for 5-hydroxyconiferaldehyde O-methyltransferase 2 (PtrAldOMT2), an enzyme central to monolignol biosynthesis for lignification in stem-differentiating xylem (SDX) of Populus trichocarpa. Phosphorylation turned off the PtrAldOMT2 activity, as demonstrated in vitro by using purified phosphorylated and unphosphorylated recombinant PtrAldOMT2. Protein extracts of P. trichocarpa SDX, which contains endogenous kinases, also phosphorylated recombinant PtrAldOMT2 and turned off the recombinant protein activity. Similarly, ATP/Mn2+-activated phosphorylation of SDX protein extracts reduced the endogenous SDX PtrAldOMT2 activity by ∼60%, and dephosphorylation fully restored the activity. Global shotgun proteomic analysis of phosphopeptide-enriched P. trichocarpa SDX protein fractions identified PtrAldOMT2 monophosphorylation at Ser123 or Ser125 in vivo. Phosphorylation-site mutagenesis verified the PtrAldOMT2 phosphorylation at Ser123 or Ser125 and confirmed the functional importance of these phosphorylation sites for O-methyltransferase activity. The PtrAldOMT2 Ser123 phosphorylation site is conserved across 93% of AldOMTs from 46 diverse plant species, and 98% of the AldOMTs have either Ser123 or Ser125. PtrAldOMT2 is a homodimeric cytosolic enzyme expressed more abundantly in syringyl lignin-rich fiber cells than in guaiacyl lignin-rich vessel cells. The reversible phosphorylation of PtrAldOMT2 is likely to have an important role in regulating syringyl monolignol biosynthesis of P. trichocarpa.

Lignin is one of the most abundant biological polymers on the planet (1). This phenolic polymer is deposited in secondary cell walls of vascular plants and confers hydrophobicity for water transport, compressive strength, and resistance to pests and pathogens (2–4). Lignin is formed by the free-radical polymerization of monolignols, products of the highly regulated monolignol biosynthetic pathway. Monolignol biosynthesis is regulated by transcriptional activation and suppression by wood-associated NAC (NAM, ATAF1/2, and CUC2) domain factors and alternative splicing (5–7). At the metabolic level, monolignol biosynthesis is regulated by protein interactions (8, 9) and a complex network of feed-forward and -back enzyme inhibitions (10–13).

Little is known of the potential impact of posttranslational modification by protein phosphorylation in monolignol biosynthesis. Protein phosphorylation is one of the most widespread posttranslational modifications that regulates protein function in response to developmental and environmental stimuli in prokaryotes and eukaryotes (14). Phosphorylation may regulate protein activity, location, stability, or interactions. Protein modification by phosphorylation is critical for plants, regulating processes such as cellular metabolism, signal transduction, and stress responses (15–17).

The involvement of protein phosphorylation in monolignol biosynthesis was proposed more than two decades ago, because degradation products of elicitor-induced French bean phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) could be radiolabeled by [32P]orthophosphate in vivo (18). Subsequently a synthetic peptide of PAL and a recombinant poplar PAL were shown to be phosphorylated by protein fractions of elicitor-induced French bean cell suspension cultures (19). The same synthetic peptide and poplar recombinant PAL was later shown to be phosphorylated by an Arabidopsis thaliana calcium-dependent kinase (AtCPK1) (20, 21). PAL catalytic efficiency was unaffected by this phosphorylation (19). Instead, the phosphorylation was predicted to mark particular PAL subunits for turnover or to target them for specific subcellular compartments (19, 20). No evidence of protein phosphorylation was presented for the remaining monolignol biosynthetic enzymes.

In the monolignol biosynthetic pathway, most enzymes are produced in excess of what is required for a normal lignin phenotype (12). This characteristic is particularly true for 5-hydroxyconiferaldehyde O-methyltransferase 2 (PtrAldOMT2), an enzyme central to syringyl monolignol biosynthesis in Populus trichocarpa. A reduction in PtrAldOMT2 abundance to a near complete absence is predicted necessary to modify metabolic-flux for syringyl monolignol biosynthesis (12). PtrAldOMT2 has the most abundant monolignol biosynthetic gene transcript in stem-differentiating xylem (SDX) of P. trichocarpa and is the third highest transcribed gene in the whole SDX transcriptome (7). PtrAldOMT2 protein abundance is also the highest of all monolignol biosynthetic enzymes and accounts for 5.9% of the SDX proteome (22). Given the abundance of transcript and protein, regulation of PtrAldOMT2 activity by transcriptional control should be energy-intensive and slow. Posttranslational modifications such as protein phosphorylation may provide a mechanism for regulating PtrAldOMT2 activity without needing to synthesize/degrade protein, thus providing a rapid and energetically efficient mode of regulating O-methyltransferase activity for syringyl monolignol biosynthesis.

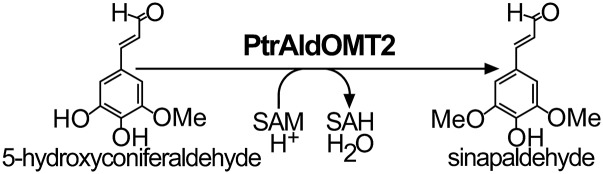

In this study, we describe the discovery of phosphorylation-mediated regulation of activity for PtrAldOMT2. AldOMT (EC 2.1.1.68) catalyzes the S-adenosyl-l-methionine (SAM)-dependent methylation of 3- and 5-hydroxyl groups of precursors for syringyl monolignol biosynthesis (12). A total of 25 gene models encode putative AldOMTs in the genome of P. trichocarpa. However, only PtrAldOMT2 is abundantly and specifically expressed in SDX and therefore is the major AldOMT for monolignol biosynthesis in P. trichocarpa (Fig. 1) (23). Knowledge of how modification by protein phosphorylation regulates the activity of PtrAldOMT2 is needed for a more comprehensive understanding of the regulation of metabolic flux in monolignol biosynthesis.

Fig. 1.

PtrAldOMT2 converts 5-hydroxyconiferaldehyde to sinapaldehyde for syringyl monolignol biosynthesis. SAH, S-adenosyl-l-homocysteine.

Results

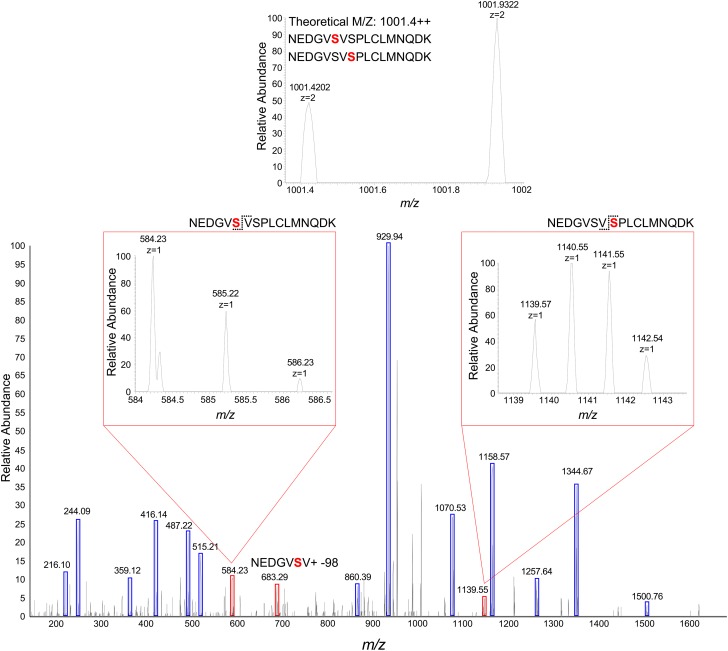

Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry Phosphoproteomic Analysis Revealed PtrAldOMT2 Monophosphorylation at Ser123 or Ser125 In Vivo.

We analyzed the phosphoproteome of P. trichocarpa SDX to investigate in vivo posttranslational protein phosphorylation of monolignol biosynthetic enzymes. We used affinity chromatography-based phosphopeptide enrichment of tryptic peptides to facilitate the identification of phosphoproteins by nanoflow reverse-phase liquid chromatography (LC)-tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS). Phosphopeptides were enriched based on the affinity of phosphate groups to ferric metal ions. The enrichment is necessary because phosphorylated peptides are often present in low abundance relative to their more abundant unphosphorylated isoforms with which they coexist (24).

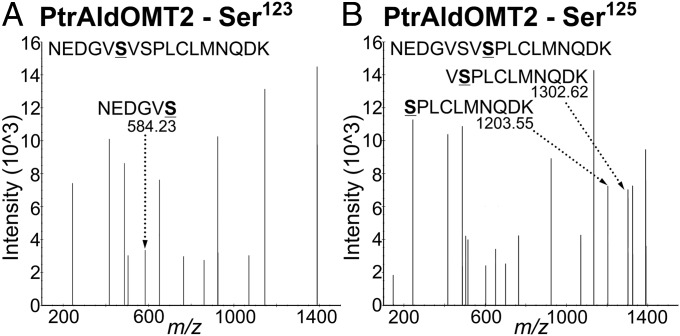

The phosphoproteomic analysis of phosphopeptide enriched SDX protein fractions yielded 1,439 protein groups and 4,836 unique tryptic peptides at a 1% protein false discovery rate (FDR) (Dataset S1). Of the total enriched proteins and peptides, 1,392 proteins (96.7%) and 4,728 (97.8%) peptides were phosphorylated, indicating successful enrichment. Two phosphopeptides mapping to PtrAldOMT2 were identified. Monophosphorylation at the Ser123 or Ser125 residue was identified for the peptides NEDGV(pS)VSPLCLMNQDK and NEDGVSV(pS)PLCLMNQDK (Fig. 2 A and B). These phosphorylated peptides also mapped to one protein other than PtrAldOMT2, an ankyrin repeat protein with an unknown function (GenBank accession no. POPTR_0015s15550). The transcripts of this ankyrin repeat protein were not xylem-specific, and its protein was not detected in any of our shotgun proteomic analyses of P. trichocarpa SDX (22, 23). In contrast, PtrAldOMT2, one of the most abundant proteins in SDX (22), was uniquely identified by other peptides in the same experiment. Therefore, these phosphopeptides identified are most likely specific to PtrAldOMT2. Phosphopeptides for PtrAldOMT2 with double phosphorylation of both Ser123 and Ser125 were undetected. Two other phosphorylated monolignol biosynthetic pathway peptides were identified: NGYQNG(pS)SESLCTQR for PtrPAL1 (Fig. S1A) and IG(pS)FEEELK, shared by PtrPAL4 and PtrPAL5 (Fig. S1B). PtrPAL4 and PtrPAL5 are xylem-specific and abundant and therefore are the key PALs involved in monolignol biosynthesis (12, 23). PtrPAL1 is shoot-specific, suggesting its involvement in other pathways (23). Identification of additional phosphoproteins involved with secondary cell-wall biosynthesis included five currently known secondary cell-wall-specific cellulose synthases (PtrCesA7, PtrCesA17, PtrCesA4, PtrCesA8, and PtrCesA18) (25), one putative family 43 glycosyltransferase (PtrIRX9), one cytochrome P450 reductase (PtrCPR1), and four transcription factors (PtrLIM1, PtrLIM2, PtrSND2/3-B1, and PtrSND2/3-B2) (Dataset S1). Given the clear presence of phosphoproteins involved in lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose biosynthesis in SDX of P. trichocarpa, our results imply that protein phosphorylation has a role in secondary cell-wall formation. We next focused on the cellular and subcellular expression patterns and protein stoichiometry of PtrAldOMT2.

Fig. 2.

PtrAldOMT2 phosphopeptides identified by LC-MS/MS–based shotgun proteomic analysis of phosphopeptide-enriched P. trichocarpa SDX protein fractions. MS spectra: Ser123 (A) and Ser125 (B) phosphorylation. Underlined S represents phosphorylated serine residues. Fragment ions showing serine phosphorylation are labeled by dashed arrows. Numbers denote m/z values.

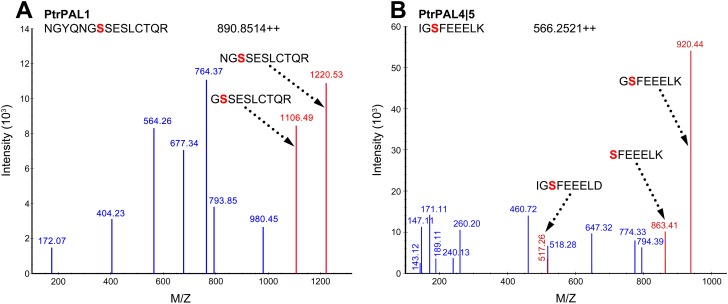

Fig. S1.

PtrPAL1 and PtrPAL4|5 phosphopeptides identified by LC-MS/MS–based shotgun proteomic analysis of phosphopeptide enriched P. trichocarpa SDX protein fractions. MS spectra: PtrPAL1 (A) and PtrPAL4|5 (B) phosphorylation. Red S represents phosphorylated serine residues. Fragment ions showing serine phosphorylation are labeled by dashed arrows. Numbers next to peaks denote m/z values.

PtrAldOMT2 Is a Homodimeric Cytosolic Enzyme Expressed More Abundantly in Fiber Cells than in Vessel Cells of P. trichocarpa SDX.

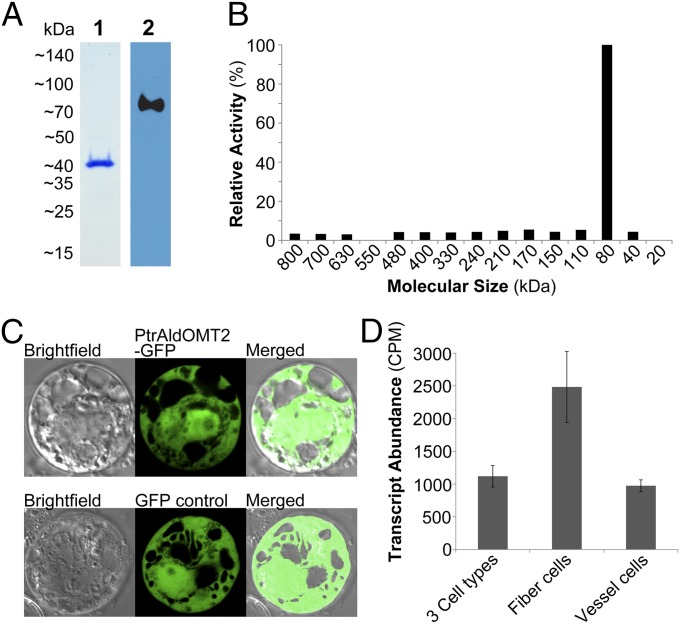

The homodimeric state of AldOMT has been demonstrated in Populus tremuloides, Medicago sativa L., and Sorghum bicolor (26–28). To verify whether PtrAldOMT2 forms a homodimer, we investigated the size of recombinant PtrAldOMT2 fused at the C terminus to a 6×His-tag (PtrAldOMT2-6×His) by blue native-PAGE (BN-PAGE). The anionic dye in BN-PAGE binds to the native PtrAldOMT2-6×His and preserves its physiological protein associations. The dye also imposes a charge shift that facilitates its migration according to protein mass as opposed to charge/mass ratio, therefore revealing its native size and protein stoichiometry. BN-PAGE of the native PtrAldOMT2-6×His showed a single protein band of ∼80 kDa (lane 2, Fig. 3A), consistent with the mass of two molecules of the monomeric protein (∼40 kDa), as determined by peptide sequence and SDS/PAGE (lane 1, Fig. 3A). To further verify that the homodimer is the physiological state of PtrAldOMT2 in vivo, we analyzed native SDX protein extracts by BN-PAGE coupled with in-gel AldOMT activity assays. AldOMT activity for the conversion of caffeic acid to ferulic acid was 10-fold higher in the ∼80-kDa gel fragment of the BN-PAGE (Fig. 3B), compared with the gel fragments containing other-sized proteins (Fig. 3B). The homodimer is the physiological and functional state of PtrAldOMT2 in P. trichocarpa SDX.

Fig. 3.

(A) Purified recombinant PtrAldOMT2-6×His analyzed by SDS/PAGE (lane 1) stained with Coomassie-blue and BN-PAGE (lane 2) immunodetected by anti-His antibody. (B) P. trichocarpa SDX protein extracts separated by BN-PAGE and analyzed by in-gel activity assays using caffeic acid as substrate. (C) Confocal fluorescence imaging of P. trichocarpa SDX protoplasts expressing PtrAldOMT2–GFP or GFP-only control. (D) PtrAldOMT2 transcript abundance in fiber cells, vessel cells, and mixtures of three cell types (fiber, vessel, and ray cells). Error bars represent one SE of three technical replicates.

We then determined the subcellular location of PtrAldOMT2. An expression vector containing a cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter and the PtrAldOMT2 gene fused at its C terminus with an sGFP coding sequence was overexpressed in P. trichocarpa SDX protoplasts, using our protocol (7, 29). The transformed SDX protoplasts exhibited uniform green fluorescence consistent with the expression of a cytosolic enzyme (Fig. 3C).

We next focused on the cellular localization of PtrAldOMT2 transcript in P. trichocarpa SDX. Differentiating fiber and vessel cells and groups of fiber, vessel, and ray cells were isolated by laser capture microdissection from stem cross-sections between internodes 15 and 20 of P. trichocarpa (9). Total RNAs were isolated from the cell samples, amplified, and analyzed by whole-transcriptome RNA sequencing (29). PtrAldOMT2 transcript relative abundance was 2.5-fold higher in the fiber cells compared with the vessel cells (Fig. 3D) and 2.2-fold higher in abundance in the fiber cells compared with the samples containing fiber, vessel, and ray cells (Fig. 3D). PtrAldOMT2 converts guaiacyl monolignol precursors for syringyl monolignol biosynthesis (10). The preferential expression of PtrAldOMT2 in fiber cells is therefore consistent with the observation that fiber cells are enriched in syringyl lignin, whereas vessel cells enriched with guaiacyl lignin would be expected to have lower PtrAldOMT2 expression (30–32). We then tested the impact of PtrAldOMT2 protein phosphorylation on its enzyme function.

P. trichocarpa SDX Contains Necessary Kinases for Monophosphorylation of PtrAldOMT2.

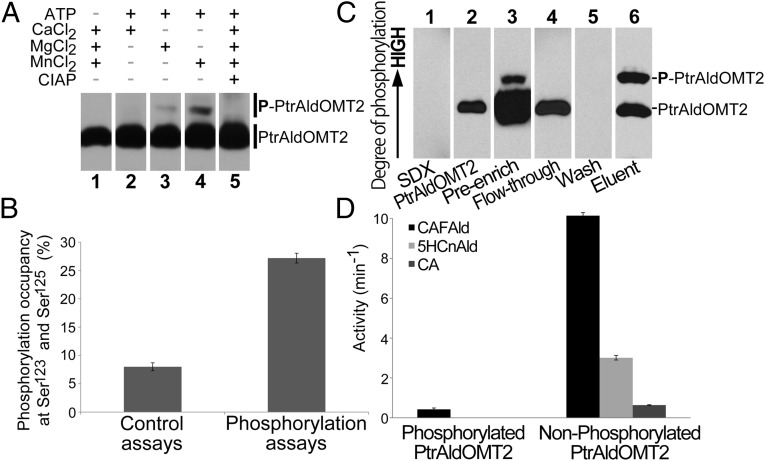

Characterizing the physiological impact of PtrAldOMT2 phosphorylation required the isolation of proteins with high levels of this posttranslational modification. Because nothing is known of the kinase that phosphorylates PtrAldOMT2, we developed an in vitro phosphorylation system using protein extracts of P. trichocarpa SDX, which contains all of the endogenous kinases. To develop this system, we tested various cofactors and substrates associated with protein phosphorylation, and monitored them by Phos-tag SDS/PAGE and Western blotting. Phos-tags bind to phosphate groups on proteins and reduce their anionic mobility, enabling the separation of phosphorylated proteins from their unphosphorylated isoforms. PtrAldOMT2-6×His phosphorylation was most active when Mn2+ and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) were added to the SDX protein extracts (lane 4, Fig. 4A); the addition of Mg2+ and ATP to SDX protein extracts only weakly activated PtrAldOMT2-6×His phosphorylation (lane 3, Fig. 4A); no phosphorylation was detected for the addition of Ca2+ and ATP to SDX protein extracts or in reactions without ATP (lanes 1 and 2, Fig. 4A). We used Mn2+ and ATP for the remaining experiments. We next tested the reversibility of PtrAldOMT2 phosphorylation. Treatment of phosphorylated PtrAldOMT2-6×His with calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase (CIAP) resulted in the complete dephosphorylation of the recombinant protein (lane 5, Fig. 4A). Recombinant PtrAldOMT2-6×His can be monophosphorylated in vitro, by incubation in P. trichocarpa SDX protein extracts containing ATP and Mn2+ (lane 4, Fig. 4A). Complete dephosphorylation of phosphorylated PtrAldOMT2 can be readily achieved, suggesting plasticity in this posttranslational modification.

Fig. 4.

(A) Recombinant PtrAldOMT2-6×His in vitro phosphorylation. (Lane 1) ATP is necessary for PtrAldOMT2 phosphorylation. (Lane 2) Ca2+ cannot facilitate PtrAldOMT2 phosphorylation. (Lane 3) Mg2+ weakly activates PtrAldOMT2 phosphorylation. (Lane 4) Mn2+ effectively activates PtrAldOMT2 phosphorylation. (Lane 5) CIAP dephosphorylates PtrAldOMT2. (B) P. trichocarpa SDX protein extracts activated recombinant PtrAldOMT2-6×His phosphorylation. Control assays, incubation at 0 °C; phosphorylation assays, incubation at 30 °C. Error bars represent one SE of five technical replicates. (C) Phos-tag SDS/PAGE of phospho-enrichment of recombinant PtrAldOMT2 phosphorylated by P. trichocarpa SDX, immunodetected by using anti-His antibody. (Lane 1) SDX-only control. (Lane 2) PtrAldOMT2-6×His only control. (Lane 3) Preenriched sample containing PtrAldOMT2-6×His and SDX. (Lane 4) Flow-through. (Lane 5) Wash buffer. (Lane 6) Enriched sample containing phosphorylated PtrAldOMT2-6×His and phosphorylated SDX proteins. (D) Activity of unphosphorylated and phosphorylated PtrAldOMT2-6×His, with caffeic acid (CA), caffealdehyde (CAFAld), or 5-hydroxyconiferaldehyde (5HCnAld) as substrate. Error bars represent one SE of three technical replicates.

To confirm that the phosphorylation events introduced by our in vitro system are representative of the endogenous phosphorylation in vivo, and are not due to nonspecific phosphorylation, we next characterized the phosphorylation site location and occupancy of our in vitro phosphorylation system. Recombinant PtrAldOMT2-6×His was incubated in SDX protein extracts with Mn2+ and ATP, and the reaction products were analyzed by high-resolution MS/MS. PtrAldOMT2-6×His incubated in SDX protein extracts at 0 °C was included as a negative control. Monophosphorylation at Ser123 or Ser125 was confirmed for recombinant PtrAldOMT2-6×His incubated for phosphorylation, by the detection of phosphopeptides NEDGV(pS)VPLCLMNQDK and NEDGVSV(pS)PLCLMNQDK (Fig. S2). These peptides are identical to those phosphopeptides identified in our global shotgun phosphoproteomics analysis of P. trichocarpa SDX (Fig. 2 A and B). The relative retention time of the phosphorylated and unphosphorylated peptides, accurate intact mass (<2 ppm), and fragment ion spectra were all consistent with global data and expected values. Consistent with the results of the global phosphoproteomics analysis was the lack of detectable PtrAldOMT2-derived peptides with phosphorylation at both Ser123 and Ser125 residues. The monophosphorylation is reasonable because the two phosphorylation sites are too close together to allow for concurrent phosphorylation at both sites.

Fig. S2.

TSIM-ddMS/MS analysis of phosphorylated recombinant PtrAldOMT2 protein. Red S represents the phosphorylated serine residues. Accurate MS1 within 2 ppm along with high sequence coverage by several MS/MS fragment ions within 0.02 Da allows for confident identification of phosphorylated peptides. Blue bars represent fragment ions corresponding to both PtrAldOMT2 phosphopeptides. Red bars indicate specific fragment ions that uniquely identify S123 and S125 phosphorylation.

With the phosphorylation sites confirmed for the recombinant PtrAldOMT2, we next quantified the levels of phosphorylation introduced by SDX protein extracts. Total phosphorylation occupancy at Ser123 and Ser125 was increased 3.45-fold from 7.88 ± 0.71% in the 0 °C controls to 27.16 ± 0.86% by in vitro phosphorylation (Fig. 4B). Phosphorylation observed for the controls is likely due to residual kinase activity at 0 °C. Our in vitro phosphorylation system can effectively increase the levels of phosphorylation of recombinant PtrAldOMT2, and the sites of phosphorylation induced are consistent with the endogenous phosphorylation sites in P. trichocarpa SDX. Using this in vitro phosphorylation system, we then produced purified phosphorylated recombinant PtrAldOMT2-6×His for enzyme functional analysis.

Purified Phosphorylated Recombinant PtrAldOMT2 Has Essentially No O-Methyltransferase Activity.

To determine how phosphorylation affects the O-methyltransferase function, we produced purified phosphorylated recombinant PtrAldOMT2-6×His, using our in vitro phosphorylation system and phosphate-specific affinity chromatography. Protein fractions were analyzed by Phos-tag SDS/PAGE and Western blotting using anti-His-antibody (Fig. 4C). P. trichocarpa SDX protein extracts phosphorylated 9% of the total recombinant protein (preenrichment, Fig. 4C). Using affinity chromatography, we increased phosphorylation to 45% of the total PtrAldOMT2-6×His (eluent, Fig. 4C). The absence of a protein band in the wash buffer (wash, Fig. 4C) indicates a complete separation of unphosphorylated PtrAldOMT2-6×His from their phosphorylated counterparts. The flow-through shows only a single band corresponding to the unphosphorylated PtrAldOMT2-6×His (flow-through, Fig. 4C), indicating successful retention of all phosphorylated PtrAldOMT2-6×His by affinity chromatography. We then assayed the activity of the purified phosphorylated PtrAldOMT2-6×His using caffeic acid, caffealdehyde, or 5-hydroxyconiferaldehyde as the substrate.

When phosphorylated, the rate of conversion of caffealdehyde to coniferaldehyde was reduced to 4% of the unphosphorylated PtrAldOMT2-6×His control (Fig. 4D). No activity was detected for the phosphorylated PtrAldOMT2-6×His when either caffeic acid or 5-hydroxyconiferaldehyde was the substrate (Fig. 4D). These results showed that modification by phosphorylation inhibits PtrAldOMT2 enzyme activity. The presence of two bands of approximately equal proportions in the eluent (eluent, Fig. 4C) suggests that phosphorylation of only one subunit of the dimeric PtrAldOMT2 is sufficient for inactivation. To confirm the phosphorylation-mediated inhibition of PtrAldOMT2 in vivo, we next investigated how O-methyltransferase activity in P. trichocarpa SDX protein extracts is affected by phosphorylation.

Phosphorylation Inhibits Endogenous PtrAldOMT2 Activity in P. trichocarpa SDX Protein Extracts.

To confirm the phosphorylation-induced inhibition of PtrAldOMT2 enzyme activity, total protein extracts of P. trichocarpa SDX were treated with ATP and Mn2+ to promote phosphorylation of the endogenous SDX proteins (Fig. 5A). Unphosphorylated native SDX protein extracts were included as a control. When phosphorylated, AldOMT activity in SDX was reduced to 44% of the control for conversion of caffeic acid to ferulic acid (Fig. 5B) and to 49% of the control for conversion of caffealdehyde to coniferaldehyde (Fig. 5B). The reduced AldOMT activity in SDX was not due to protein degradation, because the abundance of endogenous PtrAldOMT2 in SDX protein extracts was not reduced by phosphorylation (Fig. 5A). CIAP treatment to remove phosphorylation restored AldOMT activity to the levels of the native SDX control (Fig. 5B). We also assayed changes in PAL activity in the SDX protein extracts. Phosphorylation and CIAP treatments did not alter the PAL activity in SDX compared with the control (Fig. 5B), consistent with the observation that recombinant PAL catalytic efficiency (Vmax/Km) was unaffected by phosphorylation (19). Having confirmed the phosphorylation-mediated inhibition of PtrAldOMT2 activity, we next focused on the functional roles of the individual PtrAldOMT2 phosphorylation sites.

Fig. 5.

(A) ATP/Mn2+-activated phosphorylation of P. trichocarpa SDX protein extracts, analyzed by Phos-tag SDS/PAGE and immunodetected by using polyclonal anti-PtrAldOMT2 antibody. Control “C” denotes PtrAldOMT2-6×His. (B) AldOMT and PAL activities in phosphorylated, CIAP-treated, and untreated native P. trichocarpa SDX protein extracts. CA, caffeic acid; CAFAld, caffealdehyde; CiA, cinnamic acid; CnAld, coniferaldehyde; FA, ferulic acid; Phe, phenylalanine. Error bars represent one SE of three technical replicates. (C) Phos-tag SDS/PAGE of unphosphorylated recombinant PtrAldOMT2-6×His site-directed mutagenesis at Ser123 (S123N), Ser125 (S125N), and both Ser123 and Ser125 (S123N:S125N). (D) Phos-tag SDS/PAGE of in vitro phosphorylation of native and mutated PtrAldOMT2-6×His immunodetected by anti-His antibody. (Lane 1) PtrAldOMT2-6×His only control. (Lane 2) PtrAldOMT2-6×His in SDX. (Lane 3) S123N in SDX. (Lane 4) S125N in SDX. (Lane 5) S123N:S125N in SDX. (E) O-methyltransferase activity of native PtrAldOMT2-6×His, S123N, S125N, and S123N:S125N with caffeic acid, caffealdehyde, or 5-hydroxyconiferaldehyde as substrates. Activities are single measurement determinations.

Site-Directed Mutagenesis at Ser123 and Ser125 Verified PtrAldOMT2 Phosphorylation Sites and Their Functional Significance.

To further verify the identity of the Ser123 and Ser125 phosphorylation sites in PtrAldOMT2, and to directly assess the functional roles played by these serine residues, we used site-directed mutagenesis to convert Ser123 and Ser125 either singly or doubly to asparagine to produce S123N, S125N, and S123N:S125N recombinant PtrAldOMT2-6×His. Asparagine is a nonphosphorylatable amino acid that mimics the polar uncharged serine in the unphosphorylated PtrAldOMT2 (33). Recombinant proteins of S123N, S125N, and S123N:S125N were produced in Escherichia coli, purified to near homogeneity (Fig. 5C), and analyzed for phosphorylation by SDX protein extracts. As expected, monophosphorylation was observed when S123N or S125N was assayed for phosphorylation (lanes 3 and 4, Fig. 5D). No phosphorylation was observed when the double-mutant S123N:S125N was incubated in SDX protein extracts with Mn2+ and ATP (lane 5, Fig. 5D). Therefore, the phosphorylation of PtrAldOMT2 is exclusively limited to the Ser123 and Ser125 residues, and their mutation prohibited phosphorylation of PtrAldOMT2 by P. trichocarpa SDX protein extracts (lane 5, Fig. 5D). We next assessed their biochemical functions.

We analyzed the O-methyltransferase activities of recombinant S123N, S125N, and S123N:S125N using caffeic acid, caffealdehyde, or 5-hydroxyconiferaldehyde as substrates. When Ser123 was converted to asparagine, O-methyltransferase activity was reduced to 6.9% of the unmodified PtrAldOMT2 control for caffeic acid (Fig. 5E), to 15.2% of the control for caffealdehyde (Fig. 5E), and to 9.5% of the control for 5-hydroxyconiferaldehyde (Fig. 5E). Inhibition of O-methyltransferase activity was less severe when Ser125 was converted to asparagine. S125N activity was 35.9% of control for caffeic acid (Fig. 5E), 39.8% of control for caffealdehyde, and 26.2% of control for 5-hydroxyconiferaldehyde (Fig. 5E). When both Ser123 and Ser125 were converted to asparagine, as in S123N:S125N, O-methyltransferase activity for all three substrates was below the level of detection (Fig. 5E). The significant reduction in O-methyltransferase activity when Ser123 and/or Ser125 was modified confirmed that these serine residues are important for maintaining PtrAldOMT2 function and that modifications to either one or both of these residues will drastically affect O-methyltransferase activity. In addition, the more severe inhibition observed for a modification of Ser123 compared with Ser125 suggests that the Ser123 phosphorylation site plays a more important role for PtrAldOMT2 O-methyltransferase activity. The question is then whether these phosphorylation sites are conserved in plant AldOMTs.

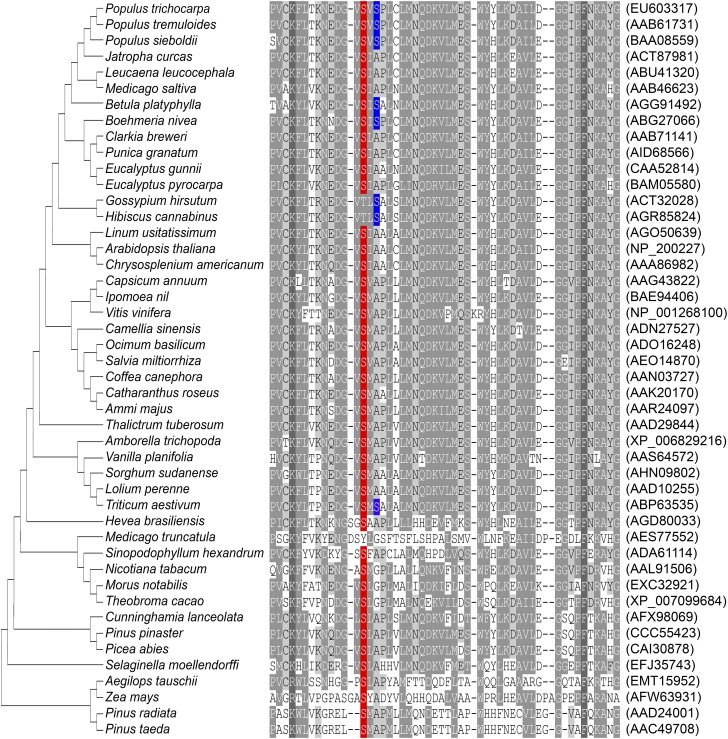

The Ser123 Phosphorylation Site Is Highly Conserved in AldOMTs from Diverse Plant Species.

To elucidate the conservation of the Ser123 and Ser125 phosphorylation sites in plants, we aligned AldOMT protein sequences from 46 diverse vascular plant species (Fig. S3). AldOMTs in 45 of 46 (98%) plant species have either one or both PtrAldOMT2 phosphorylation sites (Fig. S3). Medicago truncatula is the species without either serine residues. The Ser123 phosphorylation site is conserved across 43 of 46 (93%) AldOMTs (Fig. S3). The three plant species (Gossypium hirsutum, Hibiscus cannabinus, and M. truncatula) without Ser123 retained a phosphorylatable threonine or tyrosine residue in place of Ser123. In contrast, the PtrAldOMT2 Ser125 residue is only found in 8 of 46 (17%) AldOMTs, with small nonpolar alanine or glycine residues in place of serine (Fig. S3). The highly conserved PtrAldOMT2 Ser123 phosphorylation site strongly suggests that such posttranslational modification is evolutionally important functional regulation of the O-methyltransferase in the monolignol biosynthetic pathway.

Fig. S3.

Neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree and alignment of PtrAldOMT2 Ser123 and Ser125 residues to AldOMT from diverse plant species. AldOMT protein sequences of 46 plant species were obtained from NCBI (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) and aligned (110th to 160th residues of PtrAldOMT2 shown). Red highlights represent alignment to Ser123 of PtrAldOMT2, and blue highlights represent alignment to Ser125 of PtrAldOMT2. The GenBank accession numbers are listed in parentheses.

Discussion

Suppression of enzyme activity by protein phosphorylation represents an important regulatory process in the control of plant metabolism (14). Key metabolic pathways, such as in sucrose and nitrogen metabolism, are regulated by phosphorylation-mediated enzyme suppression. For example, reversible phosphorylation of Ser158 converts sucrose phosphate synthase to a low-activity form (34); similarly, the phosphorylated form of nitrate reductase is inactive, whereas the dephosphorylated form is active (35). Reversible phosphorylation may also activate plant metabolic enzyme activities. Phosphorylation of Ser15 in vitro activates sucrose synthase, by increasing substrate affinities (36). Although protein phosphorylation/dephosphorylation-dependent regulation is essential and ubiquitous in plant metabolism, the involvement of this posttranslational modification in regulating monolignol biosynthesis had remained largely undefined.

With the advent of phosphopeptide enrichment and high-throughput MS, large-scale global phosphoproteomic analysis has been applied to 20 plant species, and >31,000 plant phosphoproteins have been identified (37). These data revealed phosphopeptides mapping to 4 of 10 monolignol biosynthetic enzyme families: a PAL of Zea mays and M. truncatula; a cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase of A. thaliana, M. truncatula, and Brachypodium distachyon; and a cinnamoyl-CoA reductase and an AldOMT of A. thaliana (37). However, no evidence has been presented to show functional regulation by protein phosphorylation for these monolignol pathway enzymes.

Protein phosphorylation acts as an on/off regulatory switch for PtrAldOMT2 activity in monolignol biosynthesis of P. trichocarpa, providing an additional level of regulation for this important pathway. PtrAldOMT2 is monophosphorylated at Ser123 or Ser125 residues in wild-type SDX of P. trichocarpa. The monophosphorylation of recombinant PtrAldOMT2 could be activated by P. trichocarpa SDX extracts containing endogenous kinases (Fig. 4A). An important regulatory function of protein phosphorylation is the modulation (activation or suppression) of enzyme activity. Phosphorylation of PtrAldOMT2 results in the loss of function of the O-methyltransferase activity, which is essential for syringyl monolignol biosynthesis (10). On–off PtrAldOMT2 switching may be an efficient way to regulate syringyl monolignol metabolic flux in the pathway (12). The serine phosphorylation sites in PtrAldOMT2 are adjacent to Met130, an important residue for phenylpropanoid binding by sequestering the phenyl ring that presents a reactive hydroxyl group to SAM (27). The addition of the strong negative charge of a phosphate group to Ser123 or Ser125 could induce a conformational change in the PtrAldOMT2 protein structure, preventing substrate binding. Using site-directed mutagenesis, we confirmed Ser123 and Ser125 as important regulatory sites for PtrAldOMT2 activity (Fig. 5E).

Regulating protein-turnover is also a physiological role of phosphorylation in plant metabolism (38). Phosphorylation in plants is known to affect the stability of proteins, such as the D1 and D2 proteins of photosystem II (39). Phosphorylation also triggers both protein synthesis and degradation. For example, DELLA protein regulation of gibberellin-dependent growth processes and their degradation rate is controlled by phosphorylation status (40), and plant TOR kinase stimulates protein synthesis through its impact on phosphorylation of the translational activator S6 kinase (41). In the monolignol biosynthetic pathway, phosphorylation has been suggested to affect the stability of poplar PAL (19). On the contrary, we observed no reduction in PtrAldOMT2 abundance in the ATP/Mn2+–activated protein phosphorylation of P. trichocarpa SDX protein extracts (Fig. 5A), suggesting that PtrAldOMT2 protein stability is not regulated by protein phosphorylation.

Early reports of protein phosphorylation in monolignol biosynthesis demonstrated that PAL of hybrid poplar could be phosphorylated in vitro (19, 20). Subsequently, two poplar phosphoproteomic studies identified 151 and 147 phosphoproteins in dormant terminal buds of the hybrid Populus simonii × Populus nigra (42) and in differentiating xylem of P. trichocarpa (13), respectively. None of these phosphoproteins were associated with monolignol biosynthesis. Whether protein phosphorylation was involved in monolignol biosynthesis of poplar species could not be answered by these previous studies.

Our large scale phosphoproteomic analysis using MS/MS of phosphopeptide-enriched tryptic fractions identified 1,392 specific phosphoproteins in the SDX of P. trichocarpa. Improved analytical and bioinformatics methods, coupled with buffers that inhibit dephosphorylation, have enhanced the sensitivity and coverage of our analysis of the SDX phosphoproteome (SI Materials and Methods). In addition to PtrAldOMT2, several other secondary-cell-wall–associated enzymes and transcription factors were found to be phosphorylated (Dataset S1). The presence of these phosphoproteins in SDX suggests that protein phosphorylation may regulate the biosynthesis of cellulose, hemicelluloses, and lignin and, therefore, secondary cell wall formation.

Sequence alignment of 46 AldOMTs from diverse plant species showed phosphorylation sites that have been conserved or have diverged over evolutionary time. The Ser123 phosphorylation site is highly conserved across 93% of all AldOMTs (Fig. S3). Given the presence of the Ser123 phosphorylation site, this regulatory mechanism is likely to be of general occurrence in plants. This finding suggests strong selection of AldOMT phosphorylation for regulation. The presence of a second phosphorylatable serine (Ser125) in AldOMT of P. trichocarpa and several other plant species suggests the emergence of redundancy for a vital function of phosphorylation. In support of redundant functions of Ser123 and Ser125 is the evidence that either site can undergo phosphorylation independently (Fig. 5D). Ser123 and Ser125 may also act as independent docking sites for distinct kinases and signaling pathways. Defining the temporal regulation of PtrAldOMT2 phosphorylation should yield new insights into the regulation of monolignol biosynthesis.

SI Materials and Methods

Plant Materials.

P. trichocarpa (genotype: Nisqually-1) was maintained in a greenhouse as described (11). SDX from 6-mo-old trees was harvested as described (11, 23) for protein and protoplast isolation.

Crude Protein Isolation from P. trichocarpa SDX.

A total of 1.5 g of freshly harvested SDX was ground in liquid nitrogen using a mortar and pestle. The powdered SDX was resuspended in 5 mL of ice-cold extraction buffer containing 50 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.5), 20 mM sodium ascorbate, 0.4 M sucrose, 100 mM sodium chloride, 5 mM DTT, 10% (wt/wt) polyvinylpolypyrrolidone, 1 mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride, 9 µg/mL pepstatin, 9 µg/mL leupeptin, 1× PhosSTOP (Roche), and 10% (vol/vol) glycerol. The mixture was homogenized on ice with an electric homogenizer (IKA) for 15 min, filtered through two layers of miracloth (EMD Millipore), and centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was used immediately for proteomic analysis, immunodetection, and enzyme assays.

Production of PtrAldOMT2 Recombinant Protein.

The full-length coding region of the PtrAldOMT2 gene was previously cloned and sequenced (23). Recombinant PtrAldOMT2 protein with a C terminus 6xHis-tag was expressed in E. coli and purified by using Ni-NTA (Life Technology) His-tag affinity as described in ref. 23.

BN-PAGE.

BN-PAGE with a 4–16%, 1.5-mm-thick gradient gel was prepared by using the Hoefer Mighty Small SE-200 gel caster (Hoefer). Purified recombinant PtrAldOMT2 protein fused with C terminus 6×His-tag or total SDX proteins of P. trichocarpa was loaded into the wells of the vertical gel, and cathode buffer with 0.1% Coomassie G 250 was added. Electrophoresis was performed at 100 V for 5 h, and the proteins were transferred to a PAD membrane (Thermo Scientific) and Western blotted using anti-His antibody (Sigma Aldrich) as described in ref. 9.

Laser Capture Microdissection.

Cell samples containing fiber cells, vessel cells, or a mixture of these three different cell types (fiber, vessel, and ray) were collected from 6-mo-old greenhouse-grown P. trichocarpa by using a LMD7000 (Leica) as described in ref. 9. Total RNA from the three samples was isolated, amplified, and analyzed by full-transcriptome RNA-sequencing following procedures described in ref. 7. The sequencing reads were mapped to the P. trichocarpa genome (Version 2.2) (Phytozome Version 7.0; phytozome.jgi.doe.gov/pz/portal.html) using TOPHAT and normalized as described in ref. 7.

Filter-Aided Sample Preparation and Immobilized Metal-Affinity Chromatography for Phosphopeptide Enrichment.

A total of 750 µg of SDX protein was processed by using filter-aided sample preparation (FASP) as described (22), using two 10-kDa-molecular-mass cutoff filters (Millipore). Samples were digested overnight using modified porcine trypsin with previously optimized parameters for shotgun proteomic analysis (22). Recombinant PtrAldOMT2 samples were processed using the same FASP protocol. Digested recombinant protein samples were then lyophilized and reconstituted immediately before LC-MS/MS analysis in 50 µL of 0.001% zwittergent 3-16 (Calbiochem).

Phosphopeptide enrichment was carried out using iron(III)-immobilized metal-affinity chromatography (Fe-IMAC) as described (13). An aliquot of 400 µL of nitrilotriacetic acid agarose resin (Qiagen) was transferred to a 1.5-mL microcentrifuge tube and centrifuged at 425 × g for 30 s, and the supernatant was removed. This centrifugation was repeated twice. The resin was then washed three times with 1 mL of H2O and centrifuged for 30 s, and the supernatant was removed. The resin was then washed three times with 1 mL of 1% glacial acetic acid, vortexed, and then centrifuged, removing the supernatant. Finally, 1 mL of 100 mM FeCl3 in 1% acetic acid was added, and the centrifuge tube was wrapped in aluminum foil to prevent exposure to light and placed on a rocker for 4 h. An aliquot of 100 µL of Fe-IMAC slurry was added to a 200-µL gel loader pipette tip (USA Scientific) plugged with ultrahigh-molecular-weight polyethylene sheet disks of 7-µm pore size and 0.025-inch thickness (Interstate Specialty Products) to retain the resin. The pipette tip was precut and adapted to fit a standard 5-mL syringe. The resin was then washed twice with 100 µL of 2% (vol/vol) acetic acid. A total of 750 µg of digested protein was then dissolved in 100 µL of 2% (vol/vol) acetic acid and added to the pipette tip. The flow-through was collected and reloaded onto the pipette tip. The tip was then washed three times with 100 µL of 2% (vol/vol) acetic acid, then three times with 100 µL of 74/25/1 (100 mM NaCl/acetonitrile/glacial acetic acid), and finally three times with 100 µL of H2O. A total of 100 µL of 5% (vol/vol) ammonium hydroxide was added and mixed into the pipette tip for at least 2 min, and the eluent was collected. This was done three times. The eluent was acidified with 5 µL of 100% formic acid, dried down, and dissolved in 100 µL of 0.001% zwittergent immediately before analysis.

LC-MS/MS Analysis of Phosphorylated Peptides.

Phospho-enriched SDX samples were analyzed in triplicate by using a Thermo Scientific EASY nLC II operated in a trap-and-elute configuration and directly coupled to a quadruple orbitrap benchtop mass spectrometer (Q Exactive; Thermo Scientific). An injection of 10 µL was performed to a NanoFlex Chip-LC trap column, 200 µm × 0.5 mm in-line with an analytical column, 75 µm × 15 cm (Eksigent) both packed with Chrom XP C18-CL (3-μm particle size, 120-Å pore size). A 100-min elution was performed at a flow rate of 350 nL/min, by using a 5–30% B gradient. Mobile phases A and B were composed of water/acetonitrile/formic acid [98%/2%/0.2% (vol/vol) and 2%/98%/0.2% (vol/vol), respectively]. Q Exactive instrument parameters, previously optimized for global proteomics, were implemented for MS analysis (9, 22). The mass spectrometer was operated in the data-dependent mode in which a full-scan MS (from 400 to 1,600 m/z) with resolving power of 70,000 full width at half-maximum (FWHM; height at 200 m/z) was followed by up to 12 MS/MS scans [top 12 data-dependent MS/MS (ddMS/MS)] with a resolving power of 17,500 FWHM. In addition, two injections using a neutral loss method were performed with neutral losses for phosphorylation 98 Da (∆48.988 m/z, ∆35.658 m/z, and ∆24.494 m/z). An automatic gain control (AGC) target for MS scans was set to 1E6, with a maximum ion injection time (IT) of 60 ms for full MS and an AGC target of 2E4 for MS/MS scans with a maximum IT of 120 ms. Unassigned ions and ions with +1 charge state were rejected from MS/MS isolation and activation. Dynamic exclusion time was set to 30 s. A normalized collision energy of 27 was used with an isolation window of 2.0 m/z. A capillary voltage of +2.0 kV was used, and the temperature was set to 275 °C.

To confirm the phosphorylation site of in vitro-phosphorylated PtrAldOMT2-6×His, a top-12 ddMS/MS method was performed using the same parameters as performed with phospho-enriched SDX protein extract and included an inclusion list containing all m/z values of peptides identified during shotgun phosphoproteomic analysis of phospho-enriched SDX extracts. Phosphorylated PtrAldOMT2-6×His samples were analyzed by four injections (three data-dependent and one targeted method). If an m/z contained in the inclusion list were present above a threshold abundance, it would be selectively fragmented to obtain an MS2 spectrum. In addition, to ensure consistent monitoring of phosphopeptides of interest and to quantify the site occupancy of the phosphopeptide, a targeted selected ion-monitoring (TSIM)-ddMS/MS method, which increases the sensitivity and reproducibility of phosphopeptide detection by targeted monitoring of specific m/z ratios, and selective fragmentation was also implemented. TSIM parameters were analogous to ddMS/MS, with the exception of no dynamic exclusion to collect continuous MS/MS spectra when the precursor is above the threshold abundance.

Peptide Identification and Site Occupancy Calculations.

Raw files obtained from phospho-enriched SDX protein extract and phosphorylated PtrAldOMT2-6×His samples were converted to “.mgf” files by using Proteome Discoverer (Thermo Scientific). Resulting “.mgf” files were searched by using Mascot Daemon against a concatenated target-reverse P. trichocarpa database, JGI P. trichocarpa (Version 2.2; Joint Genome Institute, U.S. Department of Energy) containing 45,134 target sequences, including corrected sequences recently cloned from P. trichocarpa (23).The database search was performed with tryptic in silico digestion and allowed a maximum of two missed cleavages on the peptides analyzed from the sequence database. The database search criteria included a fixed modification of cysteine residues for carbamidomethyl modification and variable modification of other residues to include oxidation of methionine, deamidation of asparagine and glutamine, and phosphorylation at serine, tyrosine, or threonine for the identification of phosphorylation sites. Peptide precursor mass tolerance was set at 5 ppm, and MS/MS tolerance was set at 0.02 Da for data collected on the Q Exactive. Finally, the search results (“.dat” files) obtained from Mascot were imported into ProteoIQ (Version 2.3.08; Premier Biosoft) to obtain a final peptide/protein identification list at a protein FDR of 1% and a minimum peptide length of 5 amino acids. Search results (“.dat” files) were also imported into Skyline (Version 2.5.0.6079) by building a spectral library, where peptides were filtered at a 0.9 probability. Site occupancy was calculated by using a ratio of the peak area of the phosphorylated peptide to the sum total peak area of the phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated peptides. Peaks were integrated by using the ICIS algorithm in Xcalibur (Version 2.2; Thermo Scientific).

Phos-Tag Immunodetection of Phosphorylated PtrAldOMT2.

The phosphorylated PtrAldOMT2-6×His was desalted with 50 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 6.8), 50 mM NaCl, and 10% (vol/vol) glycerol using a 0.5-mL 30-kDa-molecular-mass cutoff filter (EMD Millipore) at 4 °C to remove ATP and salts before Phos-tag SDS/PAGE electrophoresis. The desalted phosphorylated SDX-recombinant protein mixtures were run on a Phosphate Affinity SDS/PAGE containing acrylamide-pendant Phos-tag (WAKO) using 100 V for 3 h at 4 °C. The Phos-tag SDS/PAGE was prepared according to the protocol from WAKO with minor modifications. After electrophoresis, the Phos-tag SDS/PAGE was soaked in 4 mM EDTA containing transfer buffer [50 mM Tris⋅HCl pH 8, 192 mM glycine, 20% (vol/vol) methanol] for 30 min to eliminate manganese ion in the gel and then soaked in transfer buffer without EDTA for an additional 30 min before transfer to a PVDF membrane. The transferred PVDF membrane was blocked with 5% (wt/vol) nonfat milk in TBST [20 mM Tris, pH 8, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% (vol/vol) Tween 20] for 2 h at room temperature. For detection of PtrAldOMT2 recombinant protein, the PVDF membrane was incubated with 1:3,000 mouse monoclonal His-tag specific antibody (Sigma Aldrich) in TBST at 4 °C overnight. After washing with TBST, the membrane was incubated with rabbit monoclonal anti-mouse antibody (Promega) at room temperature for 4 h.

Endogenous PtrAldOMT2 in SDX was immunodetected by rabbit polyclonal PtrAldOMT2-specific antibody, and PtrAldOMT2 recombinant protein was detected by mouse monoclonal His-tag–specific antibody. The secondary antibodies for endogenous PtrAldOMT2 and PtrAldOMT2-6×His were horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse and -rabbit antibody, respectively. The enhanced chemiluminescent (Thermo) substrate was used for signal visualization.

In Vitro Phosphorylation of Recombinant PtrAldOMT2.

For analysis of recombinant PtrAldOMT2 phosphorylation, PtrAldOMT2-6×His was mixed into a fresh SDX extract with 5 mM ATP and 5 mM CaCl2, 5 mM MgCl2, or 5 mM MnCl2, and incubated at 30 °C for 3 h. For phosphorylated PtrAldOMT2 enrichment, the in vitro phosphorylation assay was conducted by mixing PtrAldOMT2-6×His into fresh SDX extract with 10 mM ATP and 5 mM MnCl2, then incubated at 30 °C for 3 h.

For LC-MS/MS phosphorylated PtrAldOMT2 sample preparation, PtrAldOMT2-6×His was bound to Ni-NTA resin (Life Technology). The resin-bound PtrAldOMT2-6×His was mixed into a protein extract of SDX with 10 mM ATP, 10 mM CaCl2, 10 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM MnCl2 and then incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. After washing three times with buffer [50 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 60 mM imidazole, 20 mM beta-mercaptoethanol, 10% (vol/vol) glycerol], PtrAldOMT2-6×His was recovered with elution buffer [50 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 250 mM imidazole, 20 mM beta-mercaptoethanol, 10% (vol/vol) glycerol].

Targeted Phosphoserine Mutagenesis in PtrAldOMT2.

The serines at PtrAldOMT2 peptide loci 123 (Ser123) and 125 (Ser125) were singly or doubly mutated by site-directed mutagenesis of the native pET28-PtrAldOMT2-His construct. Asparagine was used as the replacement for the phosphorylated serine residues. The mutagenesis was performed by using the QuikChange II Kit (Stratagene) with the following primer sets: OMT2-S123MF and OMT2-S123MR, OMT2-S125MF and OMT2-S125MR, OMT2-S123/125MF, and OMT2-S123/125MR (Table S1). The resulting mutant plasmids were verified by DNA sequencing.

Table S1.

Primers used for site-directed mutagenesis of PtrAldOMT2

| Primer name | Sequence |

| OMT2-S123MF | GACAGAGAGGGCTGACATTGACACCATCCTCGTTCT |

| OMT2-S123MR | AGAACGAGGATGGTGTCAATGTCAGCCCTCTCTGTC |

| OMT2-S125MF | GACAGAGAGGGTTGACAGAGACACCATCCTCGT |

| OMT2-S125MR | ACGAGGATGGTGTCTCTGTCAACCCTCTCTGTC |

| OMT2-S123125MF | GTTCATGAGACAGAGAGGGTTGACATTGACACCATCCTCGTTCTTG |

| OMT2-S123125MR | CAAGAACGAGGATGGTGTCAATGTCAACCCTCTCTGTCTCATGAAC |

Enrichment of Phosphorylated Recombinant PtrAldOMT2.

A phosphoprotein purification kit (QIAGEN) was used for enrichment of phosphorylated recombinant PtrAldOMT2 without modification. After phosphorylation, the phosphorylated recombinant PtrAldOMT2 was buffer-exchanged by using 5 mL of lysis buffer, 1 tablet of protease inhibitor, and 10 μL of Benzonase provided by the QIAGEN kit with 100 μL of phosphatase inhibitor mixture III (Sigma). A 0.5-mL, 30-kDa Amicon column (EMD Millipore) was used to desalt and concentrate the samples. The enrichment procedure was exactly as described in the QIAGEN kit. After enrichment, all of the eluted fractions were buffer-exchanged by using repurification binding buffer [50 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 8.0, 400 mM NaCl, 10% (vol/vol) glycerol] phosphatase inhibitor (Sigma), and protease inhibitor (QIAGEN). For His-tagged recombinant protein purification, the desalted samples were resuspended in repurification binding buffer and added onto a 2-mL Ni-NTA resin (Life Technology) packed column. The protein-bound resin was then washed with repurification washing buffer [50 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 30 mM imidazole, 20 mM beta-mercaptoethanol, 10% (vol/vol) glycerol, phosphatase inhibitor (Sigma)]. The purified recombinant protein was eluted by using repurification elution buffer (50 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 250 mM imidazole, pH 8.0, 20 mM beta-mercaptoethanol, 10% glycerol), and then buffer was exchanged, and the sample was concentrated in Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.5) and 20% (vol/vol) glycerol for protein storage and enzyme assays.

Enzyme Assays.

The enzyme activity assays of phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated PtrAldOMT2 recombinant protein were performed by using three substrates involved in monolignol biosynthesis (caffeic acid, caffealdehyde, and 5-hydroxyconiferaldehyde). Caffeic acid was purchased from Sigma Aldrich. Caffealdehyde and 5-hydroxyconiferaldehyde were biochemically or chemically synthesized as described by ref. 12. Each substrate (final concentration of 100 μM) was mixed with the assay solution containing buffer and cofactors (50 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.5, 2 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM SAM) to a final volume of 100 μL (12). The reactions were performed in three replicates. The reaction mixtures were held at 30 °C for 1 min, followed by the addition of PtrAldOMT2 or SDX extract to initiate enzymatic reactions at 30 °C for 30 min. The reactions were terminated by addition of 40 μL of 5% (vol/vol) trichloroacetic acid/40% (vol/vol) acetonitrile. The reaction mixture was then centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 20 min to remove debris. A total of 100 μL of supernatant was used for HPLC analysis on an Agilent Zorbax SB-C3 5 μm, 4.6 × 150 mm column as described in ref. 12.

Phylogenetic Analysis of PtrAldOMT2 Phosphorylation Sites.

The ClustalW program was used to align full-length protein sequences of AldOMT from 46 plant species from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI; www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). The phylogenetic analysis was performed with MEGA (Version 6), and an unrooted tree was generated by neighbor-joining.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials, crude SDX protein isolation, recombinant protein production, BN-PAGE, laser capture microdissection, filter-aided sample preparation, immobilized metal-affinity chromatography, LC-MS/MS, phosphoprotein enrichment, in vitro phosphorylation and dephosphorylation, site-directed mutagenesis, and enzyme assays, are described in detail in SI Materials and Methods. Primer sequences are listed in Table S1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation, Plant Genome Research Program Grant DBI-0922391; the North Carolina State University Jordan Family Distinguished Professor Endowment; the NC State University Forest Biotechnology Industrial Research Consortium; and National Natural Science Foundation of China Grants 31470672 and 3140093.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1510473112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Sarkanen KV. Renewable resources for the production of fuels and chemicals. Science. 1976;191(4228):773–776. doi: 10.1126/science.191.4228.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sarkanen KV, Ludwig CH. Lignins, Occurrence, Formation, Structure and Reactions. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eriksson KE, Blanchette RA, Ander P. In: Microbial and Enzymatic Degradation of Wood and Wood Components. Timell TE, editor. Springer; New York: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Higuchi T. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology of Wood. Springer; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhong R, Lee C, Ye ZH. Evolutionary conservation of the transcriptional network regulating secondary cell wall biosynthesis. Trends Plant Sci. 2010;15(11):625–632. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li Q, et al. Splice variant of the SND1 transcription factor is a dominant negative of SND1 members and their regulation in Populus trichocarpa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(36):14699–14704. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1212977109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin YC, et al. SND1 transcription factor-directed quantitative functional hierarchical genetic regulatory network in wood formation in Populus trichocarpa. Plant Cell. 2013;25(11):4324–4341. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.117697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen HC, et al. Membrane protein complexes catalyze both 4- and 3-hydroxylation of cinnamic acid derivatives in monolignol biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(52):21253–21258. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116416109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen HC, et al. Systems biology of lignin biosynthesis in Populus trichocarpa: Heteromeric 4-coumaric acid:coenzyme A ligase protein complex formation, regulation, and numerical modeling. Plant Cell. 2014;26(3):876–893. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.119685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Osakabe K, et al. Coniferyl aldehyde 5-hydroxylation and methylation direct syringyl lignin biosynthesis in angiosperms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(16):8955–8960. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.8955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang JP, et al. Functional redundancy of the two 5-hydroxylases in monolignol biosynthesis of Populus trichocarpa: LC-MS/MS based protein quantification and metabolic flux analysis. Planta. 2012;236(3):795–808. doi: 10.1007/s00425-012-1663-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang JP, et al. Complete proteomic-based enzyme reaction and inhibition kinetics reveal how monolignol biosynthetic enzyme families affect metabolic flux and lignin in Populus trichocarpa. Plant Cell. 2014;26(3):894–914. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.120881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen HC, et al. Monolignol pathway 4-coumaric acid:coenzyme A ligases in Populus trichocarpa: Novel specificity, metabolic regulation, and simulation of coenzyme A ligation fluxes. Plant Physiol. 2013;161(3):1501–1516. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.210971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson LN, Lewis RJ. Structural basis for control by phosphorylation. Chem Rev. 2001;101(8):2209–2242. doi: 10.1021/cr000225s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guérinier T, et al. Phosphorylation of p27(KIP1) homologs KRP6 and 7 by SNF1-related protein kinase-1 links plant energy homeostasis and cell proliferation. Plant J. 2013;75(3):515–525. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Umezawa T, et al. Genetics and phosphoproteomics reveal a protein phosphorylation network in the abscisic acid signaling pathway in Arabidopsis thaliana. Sci Signal. 2013;6(270):rs8. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2003509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meng X, et al. Phosphorylation of an ERF transcription factor by Arabidopsis MPK3/MPK6 regulates plant defense gene induction and fungal resistance. Plant Cell. 2013;25(3):1126–1142. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.109074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bolwell GP. A role for phosphorylation in the down-regulation of phenylalanine ammonia-lyase in suspension-cultured cells of French bean. Phytochemistry. 1992;31(12):4081–4086. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allwood EG, Davies DR, Gerrish C, Ellis BE, Bolwell GP. Phosphorylation of phenylalanine ammonia-lyase: Evidence for a novel protein kinase and identification of the phosphorylated residue. FEBS Lett. 1999;457(1):47–52. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00998-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheng SH, Sheen J, Gerrish C, Bolwell GP. Molecular identification of phenylalanine ammonia-lyase as a substrate of a specific constitutively active Arabidopsis CDPK expressed in maize protoplasts. FEBS Lett. 2001;503(2-3):185–188. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02732-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allwood EG, Davies DR, Gerrish C, Bolwell GP. Regulation of CDPKs, including identification of PAL kinase, in biotically stressed cells of French bean. Plant Mol Biol. 2002;49(5):533–544. doi: 10.1023/a:1015502117870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shuford CM, et al. Comprehensive quantification of monolignol-pathway enzymes in Populus trichocarpa by protein cleavage isotope dilution mass spectrometry. J Proteome Res. 2012;11(6):3390–3404. doi: 10.1021/pr300205a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shi R, et al. Towards a systems approach for lignin biosynthesis in Populus trichocarpa: Transcript abundance and specificity of the monolignol biosynthetic genes. Plant Cell Physiol. 2010;51(1):144–163. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcp175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fíla J, Honys D. Enrichment techniques employed in phosphoproteomics. Amino Acids. 2012;43(3):1025–1047. doi: 10.1007/s00726-011-1111-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suzuki S, Li L, Sun YH, Chiang VL. The cellulose synthase gene superfamily and biochemical functions of xylem-specific cellulose synthase-like genes in Populus trichocarpa. Plant Physiol. 2006;142(3):1233–1245. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.086678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meng H, Campbell WH. Characterization and site-directed mutagenesis of aspen lignin-specific O-methyltransferase expressed in Escherichia coli. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1996;330(2):329–341. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1996.0260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zubieta C, Kota P, Ferrer JL, Dixon RA, Noel JP. Structural basis for the modulation of lignin monomer methylation by caffeic acid/5-hydroxyferulic acid 3/5-O-methyltransferase. Plant Cell. 2002;14(6):1265–1277. doi: 10.1105/tpc.001412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Green AR, et al. Determination of the structure and catalytic mechanism of Sorghum bicolor caffeic acid O-methyltransferase and the structural impact of three brown midrib mutations. Plant Physiol. 2014;165(4):1440–1456. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.241729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin YC, et al. A simple improved-throughput xylem protoplast system for studying wood formation. Nat Protoc. 2014;9(9):2194–2205. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fergus BJ, Goring DAI. The location of guaiacyl and syringyl lignins in birch xylem tissue. Holzforschung. 1970;24(4):113–117. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Musha Y, Goring DAI. Distribution of syringyl and guaiacyl moieties in hardwoods as indicated by ultraviolet microscopy. Wood Sci Technol. 1975;9(1):45–48. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li L, et al. The last step of syringyl monolignol biosynthesis in angiosperms is regulated by a novel gene encoding sinapyl alcohol dehydrogenase. Plant Cell. 2001;13(7):1567–1586. doi: 10.1105/TPC.010111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Betts MJ, Russell RB. In: Bioinformatics for Geneticists. Barnes MR, Gray IC, editors. John Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, NJ: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huber SC. Exploring the role of protein phosphorylation in plants: From signalling to metabolism. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;35(Pt 1):28–32. doi: 10.1042/BST0350028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bachmann M, et al. 14-3-3 proteins associate with the regulatory phosphorylation site of spinach leaf nitrate reductase in an isoform-specific manner and reduce dephosphorylation of Ser-543 by endogenous protein phosphatases. FEBS Lett. 1996;398(1):26–30. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01188-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huber SC, et al. Phosphorylation of serine-15 of maize leaf sucrose synthase. Occurrence in vivo and possible regulatory significance. Plant Physiol. 1996;112(2):793–802. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.2.793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheng H, et al. dbPPT: A comprehensive database of protein phosphorylation in plants. Database (Oxford) 2014;2014:bau121. doi: 10.1093/database/bau121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nelson CJ, Millar AH. Protein turnover in plant biology. Nature Plants. 2015 doi: 10.1038/nplants.2015.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tikkanen M, Aro EM. Thylakoid protein phosphorylation in dynamic regulation of photosystem II in higher plants. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1817(1):232–238. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pal SK, et al. Diurnal changes of polysome loading track sucrose content in the rosette of wild-type arabidopsis and the starchless pgm mutant. Plant Physiol. 2013;162(3):1246–1265. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.212258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xiong Y, et al. Glucose-TOR signalling reprograms the transcriptome and activates meristems. Nature. 2013;496(7444):181–186. doi: 10.1038/nature12030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu CC, et al. Identification and analysis of phosphorylation status of proteins in dormant terminal buds of poplar. BMC Plant Biol. 2011;11(1):158. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-11-158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.