Abstract

Solid-state NMR-based structure determination of membrane proteins and large protein complexes faces the challenge of limited spectral resolution when the proteins are uniformly 13C-labeled. A strategy to meet this challenge is chemical ligation combined with site-specific or segmental labeling. While chemical ligation has been adopted in NMR studies of water-soluble proteins, it has not been demonstrated for membrane proteins. Here we show chemical ligation of the influenza M2 protein, which contains a transmembrane (TM) domain and two extra-membrane domains. The cytoplasmic domain, which contains an amphipathic helix (AH) and a cytoplasmic tail, is important for regulating virus assembly, virus budding, and the proton channel activity. A recent study of uniformly 13C-labeled full-length M2 by spectral simulation suggested that the cytoplasmic tail is unstructured. To further test this hypothesis, we conducted native chemical ligation of the TM segment and part of the cytoplasmic domain. Solid-phase peptide synthesis of the two segments allowed several residues to be labeled in each segment. The post-AH cytoplasmic residues exhibit random-coil chemical shifts, low bond order parameters, and a surface-bound location, thus indicating that this domain is a dynamic random coil on the membrane surface. Interestingly, the protein spectra are similar between a model membrane and a virus-mimetic membrane, indicating that the structure and dynamics of the post-AH segment is insensitive to the lipid composition. This chemical ligation approach is generally applicable to medium-sized membrane proteins to provide site-specific structural constraints, which complement the information obtained from uniformly 13C, 15N-labeled proteins.

Keywords: chemical ligation, random coil, intrinsically disordered proteins, total protein synthesis

Introduction

Multidimensional magic-angle-spinning (MAS) solid-state NMR (SSNMR) spectroscopy is a powerful atomic-resolution technique to elucidate the structure and dynamics of non-crystalline and disordered proteins bound to phospholipid membranes.1–4 However, many membrane proteins exhibit conformational disorder and plasticity, thus giving partially overlapping resonances that are difficult to assign completely, which preclude the determination of their three-dimensional (3D) structures. In addition, the high concentration of a few types of hydrophobic residues with relatively uniform (ϕ, Ψ) torsion angles in membrane proteins reduces the chemical shift dispersion of the NMR spectra. As a result, multidimensional SSNMR spectra of recombinant and uniformly 13C-labeled membrane proteins are challenging to analyze. Biosynthetic sparse 13C labeling using specifically 13C-labeled glucose or glycerol alleviates this difficulty by skipping the labeling of some of the carbons in the amino acid residues.5–8 However, resonance assignment of such selectively labeled proteins usually requires the same two-dimensional (2D) and 3D experiments as those developed for uniformly labeled proteins, thus multiple labeled samples are necessary to piece together the complete assignment. In addition to disordered membrane proteins, many membrane proteins contain large water-soluble domains whose crystal structures have been determined and small hydrophobic domains whose structures are unknown. These small hydrophobic domains often play important roles in the biological function of the intact protein. NMR-based structural studies may provide the greatest mechanistic insights by focusing on these hydrophobic domains. Recombinant expression of these large proteins not only is challenging but also limits the options of isotopic labeling, making it difficult to selectively detect the hydrophobic domains.

The challenges in assigning the SSNMR spectra of disordered and large membrane proteins can in principle be met by chemical ligation of two or more protein segments,9–12 in which either one of the segments is labeled or both segments are labeled but only at specific residues. The individual segments can be produced by solid-phase peptide synthesis (SPPS) when they are sufficiently small or by recombinant protein expression when they are large. One of the most common ligation mechanisms is thiolate-thioester exchange between an N-terminal cysteine residue of segment 2 and a C-terminal thioester of segment 1 to form the requisite peptide bond.11 This so-called native chemical ligation approach uses unprotected peptide segments and is carried out under neutral aqueous conditions. The same ligation chemistry can also be mediated by inteins, which are naturally occurring proteins that catalyze their own excision from the precursor proteins.

Ligation-based segmental isotopic labeling has been applied to some extent in solution NMR studies of water-soluble multi-domain proteins and glycoproteins,13,14 and has recently been demonstrated for an amyloid protein.15 However, to our knowledge, ligation-based isotopic labeling has not been demonstrated in SSNMR studies of membrane proteins. This is likely due to the difficulties of producing and solubilizing sufficient quantities of hydrophobic membrane peptides and proteins. For low-resolution biophysical and biochemical characterizations that do not require a large quantity of proteins, chemical ligation has been achieved for several membrane proteins such as potassium channels,16–19 mechanosensitive channels,20 HIV-1 Vpu,21 and the influenza M2 protein.22 Full-length influenza M2 was synthesized by ligating M2(1–49) and M2(50–97), each produced by Boc-chemistry SPPS.22 The resulting synthetic full-length M2 was used to investigate the thermodynamic stability of the tetrameric assembly of the intact protein compared to that of the transmembrane (TM) peptide. However, no site-specific structural information was obtained from this study.

In this work, we adopt Fmoc SPPS and native chemical ligation to produce a M2 construct that includes the TM domain and part of the cytoplasmic domain, in order to investigate the site-specific conformation and dynamics of the cytoplasmic tail of this protein by SSNMR. The full cytoplasmic domain of M2 spans residues 47–97, and plays important roles in infectious virus production,23 viral morphogenesis,24 binding to other influenza virus proteins such as the matrix protein 1 (M1),25,26 and regulation of the proton-channel activity.27 The first 16-residues of the cytoplasmic domain (residues 47–62) forms a membrane-surface-bound amphipathic helix (AH)28–33 and is responsible for membrane scission during virus release.34 However, the structure of the post-AH cytoplasmic tail is still elusive. In a recent study of recombinant uniformly 13C-labeled full-length M2,35 we reported chemical shift analysis of the cytoplasmic domain without complete resonance assignment. The protein was reconstituted into two lipid membranes, 1,2-dimyristoyl-snglycero-3-phosphocholine (DMPC) and a complex virus-mimetic (VM+) membrane containing cholesterol, sphingomyelin in addition to phospholipids. The DMPC-bound full-length M2 exhibited a significant number of overlapped peaks at random-coil chemical shifts, and spectral simulation by calculating the chemical shifts of various conformational models suggested that the cytoplasmic domain is unstructured. The spectra of the VM + bound protein have broader linewidths than the DMPC-bound protein, thus no structural conclusion was made. To understand the M2 cytoplasmic structure in a site-specific fashion and how it depends on the membrane composition, we have now conducted total chemical synthesis of M2(22–71), by ligating M2(22–49)-thioester with M2(50–71). We show that the yield of native chemical ligation is sufficiently high to enable SSNMR characterization of the ligated protein in DMPC and VM + membranes. We find that the post-AH cytoplasmic tail up to residue 71 is unstructured, highly dynamic, and bound to the membrane surface, thus validating the previous chemical-shift analysis. Interestingly, the chemical shifts of the cytoplasmic residues are similar between the two membranes, thus ruling out substantial conformational changes of this post-AH cytoplasmic segment by cholesterol and sphingomyelin.

Results

Native chemical ligation of M2(22–71)

The M2(22–71) construct was chosen because it is short enough to be amenable to synthesis yet long enough to show full proton channel activity27,36 and partial virus-assembly activity.25 The protein was synthesized by assembling M2(22–49)-thioester and M2(50–71) using thio-ligation chemistry [Fig. 1(b)]. Although the 50-residue construct may be synthesizable without ligation, the yield would be much less than 1% if we assume an average coupling efficiency of 90% per residue, considering the hydrophobic nature of the N-terminal half of this protein. The chemoselective ligation reaction between the two peptides was initiated by the N-terminal cysteine residue of M2(50–71) attacking the M2(22–49) thioester, giving rise to a thioester-linked intermediate.9,11 This thiol-thioester exchange is reversible at neutral pH in the presence of the catalyst 4-mercapto-phenylacetic acid (MPAA), but is followed by a rapid, irreversible intramolecular S-to-N acyl shift reaction to create the thermodynamically favored peptide bond at the ligation site.37

Figure 1.

(a) Amino acid sequence of M2(22–71). The 13C, 15N-labeled residues (A30, G34, I35, S64, T65, E66, and V68) are bolded and underlined. The naturally occurring Cys50 provides the ligation site. (b) Native chemical ligation strategy for M2. Synthetic M2(22–49)-thioester and M2(50–71) are coupled together by MPAA-catalyzed transthioesterification and an irreversible amide-bond-forming rearrangement.

One of the major obstacles of membrane protein chemical ligation is solubilizing the hydrophobic segments in the solution for the ligation reaction. We first tested a 48 mM dodecylphosphocholine (DPC) and 8M urea solution to solubilize the hydrophobic M2(22–49). HPLC and electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) analysis showed that the ligation reaction proceeded in this solution, but DPC was difficult to remove completely from the product. We next tested 100 mM octyl-β-D-glucopyranoside for solubilizing M2(22–49), but the ligation reaction did not proceed in this solution, as shown by HPLC (data not shown). A TFE/guanidinium chloride solution similarly did not allow ligation to proceed. Finally, we carried out the ligation reaction in a 60% TFE solution containing 5.4 M urea at 35 °C, which enabled both efficient solubilization of the M2(22–49)-thioester and the ligation reaction.

The combined synthesis and purification yields were ∼10% for the hydrophobic M2(22–49)-thioester and ∼30% for the more polar M2(50–71). Once the two segments were successfully synthesized, as verified by HPLC and ESI-MS (Fig. 2), we monitored the progress of the ligation reaction by analytical HPLC. At 4 h, the M2(22–49)-thioester peak at 24.3 min was dominant, while the M2(22–71) peak appeared at 20.5 min. The elution time difference is similar to that reported between full-length M2 and M2(1–49)-thioester.22 The M2(22–49)-thioester peak intensity decreased over time while the M2(22–71) intensity increased. The reaction reached completion after 18 h. Longer reaction times did not increase the yield of the ligation product further.

Figure 2.

Purification and characterization of (a, d) M2(22–49)-thioester, (b, e) M2(50–71), and (c, f) M2(22–71) by reverse-phase HPLC (a–c), and ESI-MS (d–f). HPLC shows that the ligation product's concentration increased with time over ∼18 h whereas the M2(22–49)-thioester concentration decreased. The purified product (red trace) eluted as a single peak at ∼21 min.

Conformation of membrane-bound M2(50–71) and M2(22–71)

The main purpose of this study is to measure site-specific conformation of the cytoplasmic tail C-terminal to the AH. Previous 2D 13C-13C correlation spectra of uniformly 13C-labeled full-length M2 suggested that the cytoplasmic tail may be a random coil. However, the broad linewidths of the spectra at low temperature precluded full resonance assignment, and chemical shift prediction and spectral simulation were used instead to obtain this information.35,38 With the ability to synthesize the cytoplasmic peptide, we can now obtain site-specific conformation of the post-AH cytoplasmic residues from chemical shifts. We incorporated four 13C, 15N-labeled residues in the region S64–V68. In addition, several structurally known TM residues were labeled to monitor the conformation of the TM domain.

Figure 3 shows 1D 13C cross-polarization (CP) and direct-polarization (DP) spectra of M2(50–71) and M2(22–71) in various lipid membranes. The spectra were measured in both the gel phase and liquid-crystalline phase of the membranes to detect the rigid-limit conformation and dynamics of the peptides, respectively. Resonance assignments were confirmed from 2D 13C-13C correlation spectra (Fig. 4). At high temperature, 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phophocholine (POPC)/POPG-bound M2(50–71) exhibits narrow but weak 13C signals in the CP spectrum and much stronger signals in the DP spectrum, indicating that this cytoplasmic peptide is highly mobile. The peptide 13C signals in the CP spectrum are much weaker than the lipid signals despite 13C labeling, indicating that M2(50–71) motion interferes with dipolar-based CP transfer. The resolved V68 and S64 Cα peaks in the DP spectrum both appear at random-coil chemical shifts, suggesting that this segment is unstructured. In the gel-phase membrane, all backbone Cα signals become severely broadened, indicating a large conformational distribution. The combination of narrow linewidths at high temperature and line broadening at low temperature resembles the behavior of HIV TAT(48–60), a cell-penetrating peptide that also exhibits a random coil conformation.39

Figure 3.

Variable-temperature 1D 13C MAS spectra of site-specifically labeled M2 peptides in lipid bilayers. (a) POPC/POPG (3:1)-bound M2(50–71). At 298 K, the peptide signals are weak in the CP spectrum but much stronger in the DP spectrum, indicating high mobility. At 253 K, the spectrum is severely broadened, consistent with the unstructured nature of this peptide. (b) DMPC-bound M2(22–71). The low-temperature spectrum shows narrow linewidths for the TM residues but broad linewidths for the cytoplasmic residues. At high temperature, the TM residues give high signals in the CP spectrum but low intensities in the DP spectrum, indicating their relative rigidity. (c) VM + bound M2(22–71). The chemical shifts and linewidths are similar to the DMPC-bound M2(22–71).

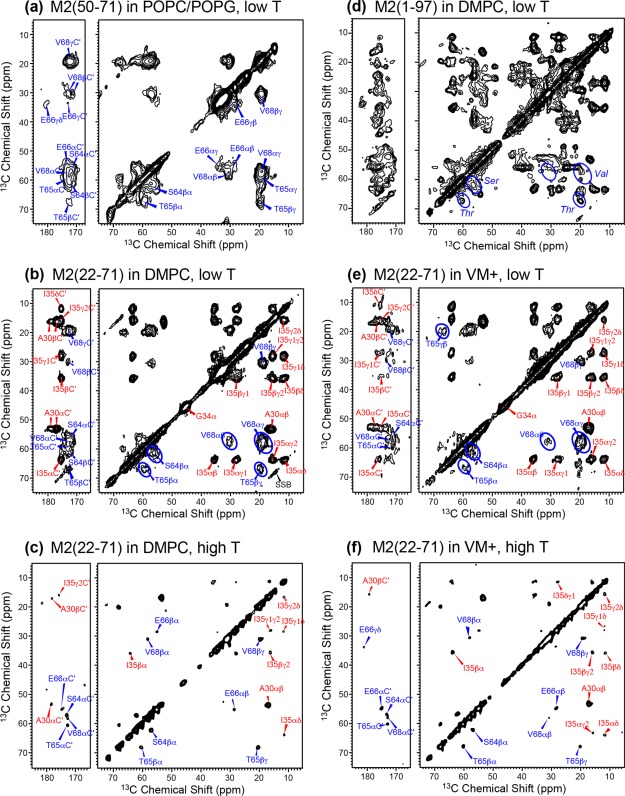

Figure 4.

2D 13C-13C correlation spectra of various M2 construct at low and high temperatures (T). TM and cytoplasmic residues are assigned in red and blue, respectively. Most spectra were measured with a spin diffusion mixing time of 100 ms except where otherwise noted. (a) 2D spectrum of POPC/POPG (3:1)-bound M2(50–71) measured at 253 K. The labeled residues show random coil chemical shifts. (b) 2D spectrum of DMPC-bound M2(22–71) measured between 245 and 263 K. A30, G34, and I35 exhibit α-helical chemical shifts whereas S64, T65, and V68 show random-coil chemical shifts that are consistent with those in M2(50–71). (c) 2D DP-DARR spectrum of DMPC-bound M2(22–71) at 298 K. The cytoplasmic residues show much sharper signals than at low temperature. (d) 2D spectrum of DMPC-bound full-length M2 with 15 ms mixing, measured between 253 and 273 K.35 (e) 2D spectrum of VM + bound M2(22–71) at 253 K. (f) 2D DP-DARR spectrum of VM + bound M2(22–71) at 298 K. The VM + spectra are similar to the DMPC spectra at similar temperatures.

Compared to M2(50–71), DMPC-bound M2(22–71) gave better resolved 13C CP spectra at low temperature, but all resolved 13C signals come from the TM residues A30, G34, and I35 [Fig. 3(b)], while the signals of the labeled cytoplasmic residues remain narrow at high temperature and severely broadened at low temperature. Thus, the post-AH cytoplasmic tail adopts the same disordered conformation in the ligated product as in the M2(50–71) peptide. The TM residues' Cα and Cβ chemical shifts are similar to those found in the TM peptide,40,41 and indicate well defined α-helical conformation, confirming that chemical ligation does not perturb the TM helix structure.

To investigate if the lipid composition affects the M2(22–71) conformation, we also reconstituted the ligated protein into the VM + membrane, which contains cholesterol and sphingomyelin in addition to phospholipids.42 Recently reported 2D 13C-13C correlation spectra of uniformly 13C-labeled M2FL showed moderate differences in some of the correlation peaks,35 suggesting that the membrane composition may induce small conformational changes of the protein between a non-cholesterol and a cholesterol-containing membrane. However, Figure 3(c) shows that the membrane composition change did not cause noticeable differences to the 1D 13C spectra compared to the DMPC data, suggesting that the lipid composition may not cause significant conformational changes to the TM domain and the post-AH cytoplasmic tail up to residue 71.

2D 13C-13C correlation spectra (Fig. 4) allowed the 13C chemical shifts to be fully resolved and assigned. For POPC/POPG-bound M2(50–71) at low temperature, S64 shows a Cα-Cβ cross peak well away from the diagonal, with a chemical shift difference of 5.3 ppm (Table1), consistent with a random-coil conformation.38 The T65, E66, and V68 Cα and Cβ chemical shifts are generally indicative of coil and sheet secondary structures.38 The low-temperature 2D spectra of DMPC- and VM+ bound M2(22–71) [Fig. 4(b,e)] highlight the challenges of studying membrane proteins that contains a well-structured domain together with a disordered domain. The three TM residues exhibit relatively narrow linewidths and high intensities while the cytoplasmic residues give much broader and weaker peaks. The 13C chemical shifts of A30, G34, and I35 are consistent with those of the TM peptide40,41,43 while the cytoplasmic residues' chemical shifts are identical to those of M2(50–71). The similarity of TM residues' chemical shifts between the long peptide and the short TM constructs is also verified in 2D 15N-13C correlation spectra (Fig. 5).

Table 1.

13C and 15N Chemical Shifts of the Labeled Residues in Membrane-Bound M2(22–71) Obtained from Total Chemical Synthesis

| Residue | Site | Chemical shifts (ppm)a |

|---|---|---|

| A30 | Cα | 52.6 |

| Cβ | 16.1 (16.7) | |

| CO | 178.1 | |

| N | 118.6 | |

| G34 | Cα | 45.4 (44.9) |

| CO | Not labeled | |

| N | 107.6 | |

| I35 | Cα | 63.4 |

| Cβ | 35.7 | |

| Cγ1 | 28.0 (27.0) | |

| Cγ2 | 15.6 | |

| Cδ | 11.6 | |

| CO | 175.3 | |

| N | 121.7 | |

| S64 | Cα | 56.2 |

| Cβ | 61.5 | |

| CO | 172.9 | |

| N | – | |

| T65 | Cα | 60.1 |

| Cβ | 67.8 | |

| Cγ | 19.9 | |

| CO | 172.9 | |

| N | – | |

| E66 | Cα | 54.8 |

| Cβ | 28.4 | |

| Cγ | 33.5 | |

| Cδ | −,(180.9) | |

| CO | 174.5 | |

| V68 | Cα | 57.9 |

| Cβ | 30.8 | |

| Cγ1, γ2 | 19.6, 18.6 | |

| CO | 172.6 | |

| N | 120.9 |

13C chemical shifts are reported on the TMS scale. Values in brackets are those measured in the VM + membrane that differ by more than 0.5 ppm from the chemical shifts in the DMPC membrane. Chemical shifts of the TM A30, G34, and I35 were obtained from low-temperature 2D correlation spectra whereas those of the cytoplasmic S64, T65, E66, and V68 residues were obtained from high-temperature 2D spectra.

Figure 5.

2D 15N-13C correlation spectra of (a) DMPC-bound M2(22–71) and (b) DLPC-bound M2(22–46).40 The similarity of the 15N and 13C chemical shifts for the common TM residues G34 and I35 indicates that the TM domain adopts the same conformation in the ligated protein and in the isolated TM peptide.

The similarity of the chemical shifts of the S64–V68 segment in M2(50–71) and M2(22–71) indicates that membrane anchoring by the TM helix and anionic lipids do not affect the unstructured nature of the post-AH segment, thus the random coil conformation is likely intrinsic to the amino acid sequence of this domain. Increasing the temperature to the liquid-crystalline phase and using direct 13C polarization gave rise to much narrower peaks for the cytoplasmic residues in the 2D spectra [Fig. 4(c,f)], consistent with the 1D 13C DP spectra. The average Cα and Cβ linewidths of the four labeled cytoplasmic residues are 1.5 and 2.2 ppm in the gel-phase DMPC and VM + membranes, respectively, but decrease to 0.8 ppm in the liquid-crystalline phase of both membranes.

The chemical shifts of DMPC-bound M2(22–71) can also be compared to those of DMPC-bound M2FL [Fig. 4(d)].35 It can be seen that the α-helical chemical shifts are well matched between the synthetic M2(22–71) and the recombinant full-length protein, and the S64, T65, and V68 peaks also fit within the Ser, Thr, and Val regions of the M2FL spectrum.

The 2D correlation spectra of VM+ bound M2(22–71) mirror those of the DMPC-bound protein, with the same chemical shifts for most sites except for some of the A30 and I35 sidechain peaks (Table1). Thus, the membrane composition has a minor effect on the TM helix conformation and no effect on the cytoplasmic conformation up to residue 71. The latter is consistent with the notion that the cytoplasmic tail is predominantly influenced by the aqueous environment, and is thus relatively insensitive to changes in the membrane fluidity, lateral pressure and other physical properties.

Depth of insertion of M2(22–71) in the lipid membrane

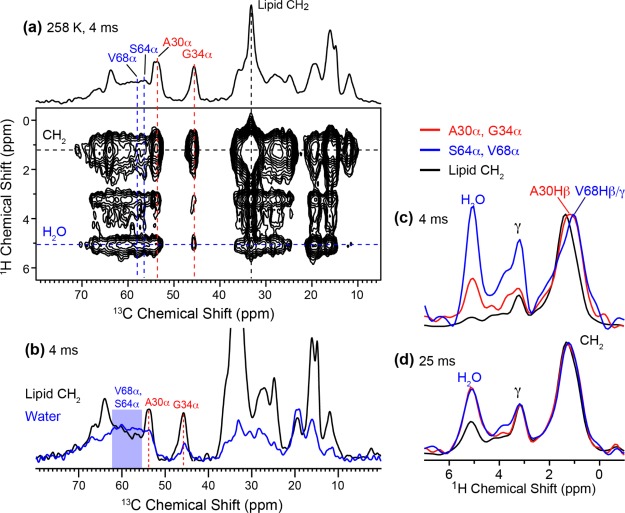

To investigate if the post-AH cytoplasmic segment lies on the membrane surface, we measured the depth of insertion of M2(22–71) in a site-specific manner using the gel-phase 2D 1H-13C correlation experiment44 [Fig. 6(a)] with 1H spin diffusion mixing times of 4 and 25 ms. At 4 ms, A30 and G34 Cα peaks show much higher lipid CH2 cross peaks than water cross peaks [Fig. 6(b)], indicating the membrane-embedded nature of these residues.45 Viewed along the 1H cross sections, S64 and V68 show a dominant water cross peak, followed by the lipid CH2 and headgroup Hγ peaks, indicating that these residues are much closer to water than the membrane interior. When the 1H cross sections of various 13C signals are normalized to the lipid CH2 cross-peak at 1.4 ppm, S64 and V68 exhibit the highest water cross peak, followed by A30 and G34, while the lipid acyl chains have negligible water intensity. Thus, the TM residues have more water contact than lipids, consistent with the fact that they surround a water-filled pore, but the water exposure of the TM residues is much lower than that of S64–V68, indicating that the cytoplasmic tail is exposed to the large aqueous environment on the membrane surface. When the 1H spin diffusion mixing time increased to 25 ms, the TM and cytoplasmic residues show the same relative lipid and water cross-peak intensities, indicating that the water magnetization has equilibrated in the protein by this time.

Figure 6.

Depth of insertion of DMPC-bound M2(22–71) by gel-phase 2D 1H-13C correlation. (a) 2D spectrum with 4 ms 1H spin diffusion, measured at 258 K. (b) 13C cross sections at the lipid CH2 (black) and water (blue) 1H chemical shifts. A30α and G34α exhibit higher lipid/water intensity ratios than S64α and V68α. (c) 1H cross section with 4 ms mixing. The 1.4-ppm peak of lipid CH2 is resolved from the A30 and V68 sidechain 1H signals. The higher water and headgroup Hγ cross peaks with S64α and V68α (blue) compared to those with A30α and G34α (red) indicates that the cytoplasmic residues are in closer contact with the membrane-surface water than the TM residues. The lipid CH2 (black) cross section has the lowest water cross peak intensity, as expected. (d) 1H cross sections measured with 25 ms 1H spin diffusion. The water cross peaks of the TM and cytoplasmic residues have equilibrated by this time.

Mobility of membrane-bound M2(22–71)

An implication of the random coil conformation is the presence of large-amplitude motion. To quantitatively determine the motional amplitudes of the cytoplasmic residues, we measured the 13C-1H dipolar order parameters of DMPC-bound M2(22–71) at 303 K using the 2D dipolar chemical-shift (DIPSHIFT) experiment. The TM helix is expected to be immobilized and have large order parameters, while the post-AH cytoplasmic residues are expected to have low order parameters. Figure 7 shows representative C—H dipolar dephasing curves of the TM and cytoplasmic residues. Since the individual cross sections of residues within each domain do not differ within experimental uncertainty, we summed the relevant cross sections to obtain higher sensitivity. The Cα sites of the TM residues exhibits deep dephasing curves that translate to order parameters of 0.94–1.0, while the cytoplasmic residues exhibit shallower dephasing curves that correspond to order parameters of 0.44–0.50. Therefore, the cytoplasmic segment is indeed highly dynamic, consistent with its random coil chemical shifts.

Figure 7.

13C-1H dipolar couplings of DMPC-bound M2(22–71) at 303 K from the DIPSHIFT experiment. Solid lines are best-fit simulations without T2 decays. (a) 13C dimensions of the 2D spectrum. (b) Sum of the A30 and I35 Cα cross sections. (c) G34 Cα cross section. The order parameters are close to 1, indicating that the TM domain is immobilized in the membrane at 303 K. (d) Sum of the S64, E66, and V68 Cα cross sections. (e) S64 Cβ cross section. Low C-H order parameters of 0.50 and 0.44 are obtained, indicating that the cytoplasmic residues undergo large-amplitude motion.

Discussion

Structural studies of the influenza M2 protein has so far largely focused on the TM domain, to understand the tetrameric assembly, lipid- and detergent-bound structures, the drug binding site, and the proton conduction mechanism (for reviews, see Refs. 46–50. In comparison, the N-terminal ectodomain and the C-terminal cytoplasmic domain are structurally mostly unknown. These two domains are involved in a number of functions such as antibody binding, M1 binding, regulation of virus morphology and virus budding.24,25,27,51–53 The best available structural information so far about these extra-membrane regions concerns the AH immediately C-terminal to the TM helix. 15N orientational NMR constraints showed that this AH domain lies on the membrane surface after a tight turn from the TM helix.28,29 This conserved AH domain causes high membrane curvature, which is necessary for membrane scission and virus release.34,54 However, the rest of the cytoplasmic domain is structurally unknown.

Recently, a 2D SSNMR study of uniformly 13C-labeled full-length M2 was conducted that suggested that the post-AH cytoplasmic domain and the ectodomain are mostly unstructured.35 This conclusion came from chemical shift prediction38 and simulations of overlapped 2D 13C-13C correlation spectra, thus it is limited by the fact that alternative conformational models may also explain the measured spectra. This motivated us to explore chemical ligation to obtain site-specific structural constraints about the cytoplasmic domain. M2 is an excellent target for native chemical ligation: it has a naturally occurring Cys50 at the junction between the TM and cytoplasmic domains; the TM domain, while hydrophobic, is synthetically more accessible than many other membrane-spanning helices; and the cytoplasmic domain is relatively polar and amenable to synthesis. We obtained synthesis and purification yields of ∼10 and ∼30% for the two segments and a ligation yield of 14%. These values correspond to a total protein yield of ∼1.4%. For comparison, a 25-residue hydrophobic membrane peptide typically shows synthesis and purification yields of ∼5%. If the same efficiency is assumed for a 50-residue peptide, then the total yield would drop to ∼0.2%. Thus, the protein yield from native chemical ligation is not inferior to, and may be comparable to or even better than, the yield of direct synthesis of hydrophobic peptides without ligation. Solubilization of the hydrophobic TM segment, which is usually the limiting factor in chemical ligation, was achieved here using a TFE solution.

The SSNMR spectra of both DMPC- and VM + membrane-bound M2(22–71) provide clear evidence that the post-AH cytoplasmic tail up to residue 71 is unstructured, exposed to the aqueous environment on the membrane surface, and highly mobile. These results significantly validate the previous conformational analysis of the full-length protein.35 The large-amplitude dynamics of the post-AH cytoplasmic segment, with backbone Cα-Hα order parameters of ∼0.5, suggests that this segment may only interact weakly with the membrane surface. Comparative studies of the AH domain would be interesting to test this hypothesis. The random coil conformation and dynamics of the post-AH 10-residue segment may be functionally relevant, as they may allow this domain to bind to other influenza virus proteins. For example, M2 binding to M1 is implicated in the regulation of virion morphology. The M1 binding site has been variously suggested to lie within residues 45–69 or residues 70–79 of M2.25,51 Since M1 is entirely helical,55,56 if the binding site lies in the post-AH 10-residue segment, then coil-to-helix conformational changes may occur to enable M1 binding. Structural studies of M2 in the absence and presence of M1 will be useful for answering this question. For such studies, it will be important to extend the cytoplasmic segment towards the C-terminus. The high synthesis yield of M2(50–71) suggests that this should be feasible, since C-terminal extension should not affect the solubility of this polar domain nor the spatial accessibility of the ligation site at Cys50 and the thioester-linked Lys49. In principle, it is possible that the last 26 residues of M2 may contain small regions of hydrogen-bonded secondary structure elements. Total synthesis of the entire cytoplasmic domain will be important for providing more complete structural information of this domain. Analogous chemical ligation approaches, whether by total synthesis or by semi-synthesis involving protein splicing, are expected to be useful for site-resolved structural studies of functionally important residues in membrane proteins as well as complementing 3D structure determination based on uniformly 13C-labeled proteins.

Materials and Methods

SPPS of M2(22–49)-thioester and M2(50–71)

Peptides corresponding to residues M2(22–49) and M2(50–71) of the influenza A/Udorn/72 strain of M2 were synthesized by Fmoc SPPS. M2(22–49)-thioester contained 13C, 15N-labeled A30, G34, and I35 while M2(50–71) contained 13C, 15N-labeled S64, T65, E66, and V68 [Fig. 1(a)].

M2(22–49) was synthesized on a Lys-preloaded thioester-generating resin, H-Lys(Boc)-sulfamylbutyryl NovaSyn® TG resin. 0.12 mmol resin (0.6 g at 0.2 mmol/g loading size) was swelled for 1 h in 2 mL N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF). Stepwise addition of Fmoc-protected amino acids (0.48 mmol, 4 eq.) was carried out with double coupling using 1-[Bis(dimethylamino)methylene]-1H-1,2,3-triazolo[4,5-b]pyridinium 3-oxid hexafluorophosphate (HATU) (0.48 mmol, 4 eq.) and N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA) (0.96 mmol, 8 eq.) in 2 mL of DMF for 0.5–1 h each. After the double coupling, Fmoc cleavage was performed twice with 20% piperidine in DMF (2 mL) for 5 and 15 min. After the last Fmoc cleavage step, the α-nitrogen of Ser22 was Boc-protected by dissolving the resin-bound peptide in 0.5 mL DMF with DIPEA (1.2 mmol, 10 eq.), then adding di-tert-butyl dicarbonate (0.6 mmol, 5 eq.) in DMF (1 mL) to the solution and stirring for 2 h. After Boc protection, the resin-bound M2(22–49) was methylated at the sulfonamide group to ensure that the thiolate acts as a nucleophile rather than a base, which would deactivate the resin towards cleavage. The resin-bound peptide was swelled for 2 h in 2 mL tetrahydrofuran (THF), then a 4 mL solution (1:1 v/v THF:hexane) of 1M (trimethylsilyl)-diazomethane was added and stirred for 2 h at room temperature. Thioester formation and peptide cleavage were induced by adding sodium thiophenolate (0.336 mmol, 2.8 eq.) and 100-fold excess methyl 3-mercaptopropionate (33.6 mmol, 280 eq.).57 The solution was stirred at room temperature for 24 h, and then filtered to remove the cleaved resin. The filtrate containing the unbound peptide was collected and dried using a rotary evaporator.

Sidechain deprotection of M2(22–49)-thioester was carried out by dissolving the peptide in 3 mL of a 88:5:2:5 (by volume) mixture of trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), water, triisopropylsilane (TIPS), and phenol and shaking for 2 h. The peptide was precipitated and triturated three times with cold diethyl ether. The crude peptide was dissolved in a 30% acetonitrile solution containing 0.1% TFA, then purified by preparative reversed-phase (RP) HPLC on a Varian ProStar 210 System using a Vydac C18 column (10 μm particle size, 2.2 × 25 cm2) with a linear gradient of 80–99% acetonitrile over 60 min at a flow rate of 10 mL/min [Fig. 2(a)]. The peaks were assigned by ESI-MS [Fig. 2(d)]. The observed mass of 3264.9 ± 0.1 Da was in good agreement with the calculated mass of 3265.0 Da. The synthesis and purification yield of M2(22–49)-thioester was ∼10%.

M2(50–71) was synthesized on a rink amide MBHA resin. 0.05 mmol resin (0.063 g with a 0.79 mmol/g loading size) was swelled for 2 h in 2 mL DMF and activated by cleaving the terminal Fmoc group using 2 mL of 20% piperidine in DMF. After the last coupling step, the peptide was deprotected and cleaved from the resin by addition of a TFA/TIPS/H2O solution (95:2.5:2.5 by volume) for 2 h. The resin was filtered off, and the crude peptide was precipitated and triturated three times with cold diethyl ether and dissolved in 30% acetonitrile solution containing 0.1% TFA. Crude peptide was purified by preparative RP-HPLC using a Vydac C18 column with a linear gradient of 20–43% acetonitrile over 60 min at a flow rate of 10 mL/min [Fig. 2(b)]. ESI-MS analysis showed a mass of 2529.3 ± 0.1 Da, in good agreement with the calculated mass of 2528.9 Da [Fig. 2(e)]. The total synthesis and purification yield of M2(50–71) was ∼30%.

Native chemical ligation of M2(22–71)

M2(22–71) was ligated by adding 50% molar excess of 45.2 mM M2(50–71) in 0.1 mL of 60% TFE (v/v) solution to 0.72 mM M2(22–49)-thioester in 4.2 mL of ligation buffer. The ligation buffer consists of 60% TFE (v/v), 5.4M urea, 67 mM sodium phosphate, 50 mM MPAA, and 20 mM Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride. The pH 4.5 solution was stirred at 35 °C, then the reaction was initiated by increasing the pH to 7.0 with 4M NaOH. The reaction was monitored by analytical RP-HPLC using a Vydac C4 column (5 μm particle size, 0.46 × 15 cm2) with a 40–99% acetonitrile gradient over 30 min. Unreacted M2(22–49)-thioester and M2(50–71) peptides appeared at 24.3 min and 6 min, respectively, while the ligation product appeared at 20.5 min [Fig. 2(c)]. The ligation was complete after 18 h. M2(22–71) was purified by preparative RP-HPLC using a linear gradient of 70–99% acetonitrile over 60 min. ESI-MS showed a mass of 5675.2 ± 0.2 Da, in good agreement with the calculated mass of 5675.7 Da [Fig. 2(f)]. About 2.5 mg of purified ligation product was obtained from starting materials of ∼10 mg each of the two peptides. The ligation yield, calculated as the ratio of the number of moles of the product with the number of moles of the M2(22–49)-thioester, which is the limiting reagent, is ∼14%.

Membrane reconstitution of M2(22–71) and M2(50–71)

Three membrane samples were prepared. M2(22–71) was reconstituted into the DMPC and VM + membranes using an organic solution mixing protocol. 4.3 mg M2(22–71) in 200 μL TFE was mixed with 12.9 mg DMPC in 500 μL chloroform, while 2 mg of M2(22–71) was mixed with 4 mg VM + lipid mixture. These correspond to peptide:lipid molar ratios (P:L) of 1:25 for the DMPC sample and 1:18 for the VM + sample. The organic solvents were removed by a stream of nitrogen gas and the mixture was lyophilized overnight. The protein-lipid mixture was suspended in a pH 7.5 Tris buffer (10 mM Tris base, 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, and 0.1 mM sodium azide) and centrifuged at 55,000 rpm at 4 °C for 4 h to obtain a homogeneous membrane pellet. The pellet was equilibrated to a hydration level of ∼40% by mass, packed into a 3.2 mm MAS rotor and stored at −30 °C until the NMR experiments. The VM + membrane consists of an equimolar mixture of POPC, 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine, egg sphingomyelin, and cholesterol. The presence of cholesterol and sphingomyelin immobilizes the whole-body uniaxial rotational diffusion of the M2 TM peptide so that protein internal dynamics can be investigated at physiological temperature.50,58 5 mg M2(50–71) was reconstituted into 20 mg of a POPC/POPG (3:1) membrane (P:L = 1:13). This negatively charged membrane was chosen to maximize the electrostatic attraction with M2(50–71).

SSNMR experiments

Most SSNMR spectra were measured on a 900 MHz (21.1 Tesla) Bruker NMR spectrometer using a 3.2 mm 1H/13C/15N MAS probe. Typical radiofrequency field strengths were 71.4 kHz and 62.5 kHz for 1H and 13C, respectively. Spectra were measured in both gel-phase and liquid-crystalline membranes to investigate the conformation and dynamics of the protein. 13C chemical shifts were externally referenced to the CH2 signal of adamantane at 38.48 ppm on the TMS scale.

2D 13C-13C correlation spectra were measured using a dipolar-assisted rotational resonance (DARR)59 experiment with a 100 ms mixing time to obtain 13C chemical shifts. 2D 15N-13C correlation spectra were measured on a 400 MHz (9.4 Tesla) Bruker NMR spectrometer using a REDOR pulse train for polarization transfer.60,61 Gel-phase 13C-1H heteronuclear correlation spectra44 were measured under 7 kHz MAS between 248 and 258 K. The frequency-switched Lee-Goldburg (FSLG) sequence62 was used to suppress the 1H-1H dipolar coupling during the 1H evolution period. The 1H spin diffusion mixing time was 4 and 25 ms, and Lee-Goldburg cross polarization63–65 was used to transfer the 1H magnetization to 13C. 13C-1H dipolar couplings were measured using the DIPSHIFT correlation experiment66 under 7 kHz MAS at 303 K. The FSLG sequence was used for 1H homonuclear decoupling during t1. The dipolar oscillation was simulated using a Fortran program to obtain the couplings, which were then divided by the FSLG scaling factor of 0.577 to obtain the real couplings. The order parameter was calculated as the ratio of the real couplings to the rigid-limit value of 22.7 kHz.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Tuo Wang for experimental help.

References

- McDermott AE. Structure and dynamics of membrane proteins by magic angle spinning solid-state NMR. Annu Rev Biophys. 2009;38:385–403. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.050708.133719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong M, Zhang Y, Hu F. Membrane protein structure and dynamics from NMR spectroscopy. Annu Rev Phys Chem. 2012;63:1–24. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physchem-032511-143731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comellas G, Rienstra CM. Protein structure determination by magic-angle spinning solid-state NMR, and insights into the formation, structure, and stability of amyloid fibrils. Annu Rev Biophys. 2013;42:515–536. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-083012-130356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joh NH, Wang T, Bhate MP, Acharya R, Wu Y, Grabe M, Hong M, Grigoryan G, DeGrado WF. De novo design of a transmembrane Zn(2)(+)-transporting four-helix bundle. Science. 2014;346:1520–1524. doi: 10.1126/science.1261172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong M, Jakes K. Selective and extensive 13C labeling of a membrane protein for solid-state NMR investigation. J Biomol NMR. 1999;14:71–74. doi: 10.1023/a:1008334930603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong M. Determination of multiple phi torsion angles in solid proteins by selective and extensive 13C labeling and two-dimensional solid-state NMR. J Magn Reson. 1999;139:389–401. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1999.1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellani F, vanRossum B, Diehl A, Schubert M, Rehbein K, Oschkinat H. Structure of a protein determined by solid-state magic-angle spinning NMR spectroscopy. Nature. 2002;420:98–102. doi: 10.1038/nature01070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loquet A, Lv G, Giller K, Becker S, Lange A. 13C spin dilution for simplified and complete solid-state NMR resonance assignment of insoluble biological assemblies. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:4722–4725. doi: 10.1021/ja200066s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson PE, Muir TW, Clark-Lewis I, Kent SB. Synthesis of proteins by native chemical ligation. Science. 1994;266:776–779. doi: 10.1126/science.7973629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muir TW, Sondhi D, Cole PA. Expressed protein ligation: a general method for protein engineering. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6705–6710. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent SB. Total chemical synthesis of proteins. Chem Soc Rev. 2009;38:338–351. doi: 10.1039/b700141j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muir TW. Semisynthesis of proteins by expressed protein ligation. Annu Rev Biochem. 2003;72:249–289. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skrisovska L, Schubert M, Allain FH. Recent advances in segmental isotope labeling of proteins: NMR applications to large proteins and glycoproteins. J Biomol NMR. 2010;46:51–65. doi: 10.1007/s10858-009-9362-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowburn D, Shekhtman A, Xu R, Ottesen JJ, Muir TW. Segmental isotopic labeling for structural biological applications of NMR. Methods Mol Biol. 2004;278:47–56. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-809-9:047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubeis T, Luhrs T, Ritter C. Unambiguous assignment of short- and long-range structural restraints by solid-state NMR spectroscopy with segmental isotope labeling. Chembiochem. 2015;16:51–54. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201402446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devaraneni PK, Komarov AG, Costantino CA, Devereaux JJ, Matulef K, Valiyaveetil FI. Semisynthetic K + channels show that the constricted conformation of the selectivity filter is not the C-type inactivated state. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:15698–15703. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1308699110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matulef K, Komarov AG, Costantino CA, Valiyaveetil FI. Using protein backbone mutagenesis to dissect the link between ion occupancy and C-type inactivation in K + channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:17886–17891. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1314356110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valiyaveetil FI, MacKinnon R, Muir TW. Semisynthesis and folding of the potassium channel KcsA. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:9113–9120. doi: 10.1021/ja0266722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komarov AG, Linn KM, Devereaux JJ, Valiyaveetil FI. Modular strategy for the semisynthesis of a K + channel: investigating interactions of the pore helix. ACS Chem Biol. 2009;4:1029–1038. doi: 10.1021/cb900210r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton D, Shapovalov G, Maurer JA, Dougherty DA, Lester HA, Kochendoerfer GG. Total chemical synthesis and electrophysiological characterization of mechanosensitive channels from Escherichia coli and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:4764–4769. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305693101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochendoerfer GG, Jones DH, Lee S, Oblatt-Montal M, Opella SJ, Montal M. Functional characterization and NMR spectroscopy on full-length Vpu from HIV-1 prepared by total chemical synthesis. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:2439–2446. doi: 10.1021/ja038985i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochendoerfer GG, Salom D, Lear JD, Wilk-Orescan R, Kent SB, DeGrado WF. Total chemical synthesis of the integral membrane protein influenza A virus M2: role of its C-terminal domain in tetramer assembly. Biochemistry. 1999;38:11905–11913. doi: 10.1021/bi990720m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCown MF, Pekosz A. The influenza A virus M2 cytoplasmic tail is required for infectious virus production and efficient genome packaging. J Virol. 2005;79:3595–3605. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.6.3595-3605.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwatsuki-Horimoto K, Horimoto T, Noda T, Kiso M, Maeda J, Watanabe S, Muramoto Y, Fujii K, Kawaoka Y. The cytoplasmic tail of the influenza A virus M2 protein plays a role in viral assembly. J Virol. 2006;80:5233–5240. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00049-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCown MF, Pekosz A. Distinct domains of the influenza a virus M2 protein cytoplasmic tail mediate binding to the M1 protein and facilitate infectious virus production. J Virol. 2006;80:8178–8189. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00627-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beale R, Wise H, Stuart A, Ravenhill BJ, Digard P, Randow F. A LC3-interacting motif in the influenza A virus M2 protein is required to subvert autophagy and maintain virion stability. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;15:239–247. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobler K, Kelly ML, Pinto LH, Lamb RA. Effect of cytoplasmic tail truncations on the activity of the M2 ion channel of influenza A virus. J Virol. 1999;73:9695–9701. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.12.9695-9701.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma M, Yi M, Dong H, Qin H, Peterson E, Busath D, Zhou HX, Cross TA. Insight into the mechanism of the influenza A proton channel from a structure in a lipid bilayer. Science. 2010;330:509–512. doi: 10.1126/science.1191750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian C, Gao PF, Pinto LH, Lamb RA, Cross TA. Initial structural and dynamic characterization of the M2 protein transmembrane and amphipathic helices in lipid bilayers. Protein Sci. 2003;12:2597–2605. doi: 10.1110/ps.03168503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnell JR, Chou JJ. Structure and mechanism of the M2 proton channel of influenza A virus. Nature. 2008;451:591–595. doi: 10.1038/nature06531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreas LB, Eddy MT, Chou JJ, Griffin RG. Magic-angle-spinning NMR of the drug resistant S31N M2 proton transporter from influenza A. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:7215–7218. doi: 10.1021/ja3003606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colvin MT, Andreas LB, Chou JJ, Griffin RG. Proton association constants of His 37 in the influenza-A M218-60 dimer-of-dimers. Biochemistry. 2014;53:5987–5994. doi: 10.1021/bi5005393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao Y, Qin H, Fu R, Sharma M, Can TV, Hung I, Luca S, Gor'kov PL, Brey WW, Cross TA. M2 proton channel structural validation from full-length protein samples in synthetic bilayers and E. coli membranes. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2012;51:8383–8386. doi: 10.1002/anie.201204666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossman JS, Jing XH, Leser GP, Lamb RA. Influenza virus M2 protein mediates ESCRT-independent membrane scission. Cell. 2010;142:902–913. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao SY, Fritzsching KJ, Hong M. Conformational analysis of the full-length M2 protein of the influenza A virus using solid-state NMR. Protein Sci. 2013;22:1623–1638. doi: 10.1002/pro.2368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma C, Polishchuk AL, Ohigashi Y, Stouffer AL, Schoön A, Magavern E, Jing X, Lear JD, Freire E, Lamb RA, DeGrado WF, Pinto LH. Identification of the functional core of the influenza A virus A/M2 proton-selective ion channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:12283–12288. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905726106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson PE, Churchill MJ, Ghadiri MR, Kent SBH. Modulation of reactivity in native chemical ligation through the use of thiol additives. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:4325–4329. [Google Scholar]

- Fritzsching KJ, Yang Y, Schmidt-Rohr K, Hong M. Practical use of chemical shift databases for protein solid-state NMR: 2D chemical shift maps and amino-acid assignment with secondary-structure information. J Biomol NMR. 2013;56:155–167. doi: 10.1007/s10858-013-9732-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su Y, Waring AJ, Ruchala P, Hong M. Membrane-bound dynamic structure of an arginine-rich cell-penetrating peptide, the protein transduction domain of HIV TAT, from solid-state NMR. Biochemistry. 2010;49:6009–6020. doi: 10.1021/bi100642n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cady SD, Hong M. Amantadine-induced conformational and dynamical changes of the influenza M2 transmembrane proton channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:1483–1488. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711500105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cady SD, Mishanina TV, Hong M. Structure of amantadine-bound M2 transmembrane peptide of influenza A in lipid bilayers from magic-angle-spinning solid-state NMR: the role of Ser31 in amantadine binding. J Mol Biol. 2009;385:1127–1141. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cady SD, Wang T, Hong M. Membrane-dependent effects of a cytoplasmic helix on the structure and drug binding of the influenza virus M2 protein. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:11572–11579. doi: 10.1021/ja202051n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cady SD, Schmidt-Rohr K, Wang J, Soto CS, Degrado WF, Hong M. Structure of the amantadine binding site of influenza M2 proton channels in lipid bilayers. Nature. 2010;463:689–692. doi: 10.1038/nature08722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T, Yao H, Hong M. Determining the depth of insertion of dynamically invisible membrane peptides by gel-phase 1H spin diffusion heteronuclear correlation NMR. J Biomol NMR. 2013;56:139–148. doi: 10.1007/s10858-013-9730-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JK, Hong M. Probing membrane protein structure using water polarization transfer solid-state NMR. J Magn Reson. 2014;247:118–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2014.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto LH, Lamb RA. Controlling influenza virus replication by inhibiting its proton flow. Mol Biosyst. 2007;3:18–23. doi: 10.1039/b611613m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Qiu JX, Soto CS, DeGrado WF. Structural and dynamic mechanisms for the function and inhibition of the M2 proton channel from influenza A virus. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2011;21:68–80. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou HX, Cross TA. Modeling the membrane environment has implications for membrane protein structure and function: influenza A M2 protein. Protein Sci. 2013;22:381–394. doi: 10.1002/pro.2232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong M, Degrado WF. Structural basis for proton conduction and inhibition by the influenza M2 protein. Protein Sci. 2012;21:1620–1633. doi: 10.1002/pro.2158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo W, Cady SD, Hong M. Immobilization of the influenza A M2 transmembrane peptide in virus-envelope mimetic lipid membranes: a solid-state NMR investigation. Biochemistry. 2009;48:6361–6368. doi: 10.1021/bi900716s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen BJ, Leser GP, Jackson D, Lamb RA. The influenza virus M2 protein cytoplasmic tail interacts with the M1 protein and influences virus assembly at the site of virus budding. J Virol. 2008;82:10059–10070. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01184-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zebedee SL, Lamb RA. Influenza A virus M2 protein: monoclonal antibody restriction of virus growth and detection of M2 in virions. J Virol. 1988;62:2762–2772. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.8.2762-2772.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Zhou L, Shi H, Xu H, Yao H, Xi XG, Toyoda T, Wang X, Wang T. Monoclonal antibody recognizing SLLTEVET epitope of M2 protein potently inhibited the replication of influenza A viruses in MDCK cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;385:118–122. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.04.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts KL, Leser GP, Ma CL, Lamb RA. The amphipathic helix of influenza A virus M2 protein is required for filamentous bud formation and scission of filamentous and spherical particles. J Virol. 2013;87:9973–9982. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01363-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris A, Forouhar F, Qiu SH, Sha BD, Luo M. The crystal structure of the influenza matrix protein M1 at neutral pH: M1-M1 protein interfaces can rotate in the oligomeric structures of M1. Virology. 2001;289:34–44. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sha B, Luo M. Structure of a bifunctional membrane-RNA binding protein, influenza virus matrix protein M1. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:239–244. doi: 10.1038/nsb0397-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson ECB, Kent SBH. Insights into the mechanism and catalysis of the native chemical ligation reaction. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:6640–6646. doi: 10.1021/ja058344i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu F, Luo W, Hong M. Mechanisms of proton conduction and gating by influenza M2 proton channels from solid-state NMR. Science. 2010;330:505–508. doi: 10.1126/science.1191714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takegoshi K, Nakamura S, Terao T. C-13-H-1 dipolar-assisted rotational resonance in magic-angle spinning NMR. Chem Phys Lett. 2001;344:631–637. [Google Scholar]

- Hong M, Griffin RG. Resonance assignment for solid peptides by dipolar-mediated 13C/15N correlation solid-state NMR. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:7113–7114. [Google Scholar]

- Gullion T, Schaefer J. Rotational echo double resonance NMR. J Magn Reson. 1989;81:196–200. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielecki A, Kolbert AC, Levitt MH. Frequency-switched pulse sequences: homonuclear decoupling and dilute spin NMR in solids. Chem Phys Lett. 1989;155:341–346. [Google Scholar]

- Lee M, Goldburg WI. Nuclear-magnetic-resonance line narrowing by a rotating Rf field. Phys Rev. 1965;140:1261–&. [Google Scholar]

- Hong M, Yao XL, Jakes K, Huster D. Investigation of molecular motions by Lee-Goldburg cross-polarization NMR spectroscopy. J Phys Chem B. 2002;106:7355–7364. [Google Scholar]

- van Rossum BJ, de Groot CP, Ladizhansky V, Vega S, de Groot HJM. A method for measuring heteronuclear (H-1-C-13) distances in high speed MAS NMR. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:3465–3472. [Google Scholar]

- Munowitz MG, Griffin RG, Bodenhausen G, Huang TH. Two-dimensional rotational spin-echo nuclear magnetic-resonance in solids: correlation of chemical-shift and dipolar interactions. J Am Chem Soc. 1981;103:2529–2533. [Google Scholar]