Abstract

The most essential properties of ion channels for their physiologically relevant functions are ion-selective permeation and gating. Among the channel species, the potassium channel is primordial and the most ubiquitous in the biological world, and knowledge of this channel underlies the understanding of features of other ion channels. The strategy applied to studying channels changed dramatically after the crystal structure of the potassium channel was resolved. Given the abundant structural information available, we exploited the bacterial KcsA potassium channel as a simple model channel. In the postcrystal age, there are two effective frameworks with which to decipher the functional codes present in the channel structure, namely reconstitution and re-animation. Complex channel proteins are decomposed into essential functional components, and well-examined parts are rebuilt for integrating channel function in the membrane (reconstitution). Permeation and gating are dynamic operations, and one imagines the active channel by breathing life into the ‘frozen’ crystal (re-animation). Capturing the motion of channels at the single-molecule level is necessary to characterize the behaviour of functioning channels. Advanced techniques, including diffracted X-ray tracking, lipid bilayer methods and high-speed atomic force microscopy, have been used. Here, I present dynamic pictures of the KcsA potassium channel from the submolecular conformational changes to the supramolecular collective behaviour of channels in the membrane. These results form an integrated picture of the active channel and offer insights into the processes underlying the physiological function of the channel in the cell membrane.

Introduction

The ion channel is a molecule that has an electrical function, generating the membrane potential and its changes across the cell membrane (Hille, 2001). The most essential processes performed by channel proteins are ion selectivity and the regulation of their permeability (gating), and both processes distinguish channels from other membrane proteins. The goal of my field of study is to elucidate the physiological mechanisms of ion channels (Ashcroft, 2000). The function of ion channels has been studied from both systems and molecular perspectives. The systems function of ion channels involves the interactions of different channel species on the membrane, such as in the generation of action potentials and in signal transduction. In contrast, the molecular function is the stand-alone process of channel molecules, involving structural changes of channel proteins under the influence of relevant stimuli and forming the physicochemical basis of selective ion permeation through the channel. Here, I address the molecular mechanism underlying channel function. How do channels effectively conduct limited species of ions? What underlies the conformational change occurring in response to the various types of stimuli? Hodgkin and Huxley addressed both molecular and systems functions during the early history of the study of channels (Hodgkin & Huxley, 1952). However, these two issues are currently discussed separately from each other, and intimate communications between these areas would support the formation of an integrated picture of channel physiology.

The study of the molecular properties of ion channels is advancing towards atomic resolution. Single-channel current recordings were the first single-molecule measurement technique (Sakmann & Neher, 2009), and the assignment of the functionally relevant parts has become more and more refined from the relevant protein domain towards responsible atoms through hot-spot residues. In parallel, the study of ion channels involves the collective behaviour of channel proteins on the membrane. Two oppositely directed programmes of study along the hierarchy of channel function are merging, producing an integrated understanding of channel physiology at the molecular level.

Here, I present the current status of the study of ion channels. The potassium channels receive particular attention because they are prototypical channels. Among the potassium channels, the KcsA channel of bacterial origin has served as a model based on the presence of crucial information provided by the crystal structure. Various techniques introduced into the study of the KcsA channel have led to a profound understanding of the essential molecular function of permeation and gating. Sharing these basic ideas of molecular mechanism would enrich the basis for interpreting the channel function in cell physiology.

The key words of this review are ‘reconstitution’ and ‘re-animation’. These words are defined here in the context of the molecular study of ion channels. ‘Reconstitution’ has been used frequently in the field of single-channel recordings for the incorporation of a channel into an artificial membrane (Miller, 1986). Here, reconstitution will be used in a broader sense, such that channel function is understood based on the assembly of separate domains. In contrast to ‘reconstitution’, ‘re-animation’ is not commonly used in the field of channel study. Why is re-animation used rather than animation? Physiologists have recognized that functioning channels are not static, but rather move ceaselessly. In fact, electrophysiologists have observed these moving objects through the use of electrical signals. However, the study of channels changed dramatically after their crystal structures became available in 1998 (Doyle et al. 1998). The channel was frozen in beautiful still pictures, allowing all of the structural details to emerge. These images show the building blocks of the channel architecture. After a period of enthusiasm, a physiologist realized that the frozen channel must be re-animated to perform its function. The observation of moving objects is a fundamental principle of many physiologists based on the belief of primitive animism: ‘all moving objects are alive’.

In the postcrystal age, reconstitution and re-animation should provide novel views for examining channel physiology. To illustrate these words in this context, I present a case study of the KcsA potassium channel, which represents the current status of the molecular understanding of ion channels.

Channel structure and function

Channel and membrane

Channel proteins developed during the evolution of life to provide an ion permeation pathway across the hydrophobic bilayer membrane. Without the membrane, the channel loses its raison d’être. On the contrary, with the existence of channels, the membrane becomes highly functional. Given the asymmetric distribution of ion concentrations across the membrane, ion channels mediate passive ion flux across the membrane, enabling the cell membrane to create an electrochemical cell. A membrane potential is generated, and in turn, the membrane potential drives passive ion permeation through the channel. Moreover, the membrane potential is subject to change because of channel gating, and the change of the membrane potential itself becomes a ‘signal’ that is exploited for signal transduction, especially for long-distance, rapid information transfer. Electrophysiologists have investigated this fundamental secret of life since the mid-20th century (McComas, 2011).

The KcsA potassium channel as a model channel

The molecular mechanisms of ion channels have been studied extensively using potassium channels. In the voltage-gated-like ion channel superfamily (Yu & Catterall, 2004), the potassium channel is a primordial and prototypical channel. In addition, potassium channels exist ubiquitously from bacteria to humans. From the functional perspective, the potassium channel is one of the most selective channels, particularly compared with sodium channels and calcium channels. There are several categories of potassium channels, including voltage-gated (Papazian et al. 1987), inward-rectifier (Kubo et al. 1993) and two-pore-domain potassium channels (Ketchum et al. 1995; Fig.1), but the highly K+ selective permeation and the gating mechanism are somehow common among them.

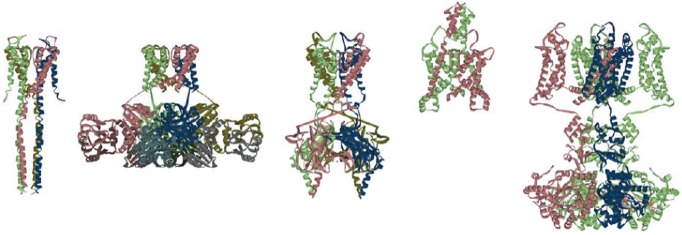

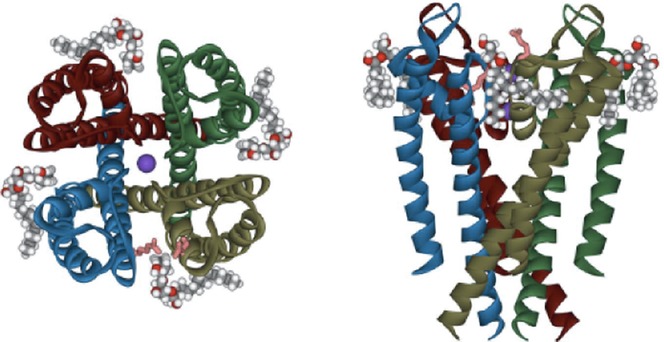

Figure 1.

Crystal structure of potassium channels

Each tetrameric subunit is coloured differently. From left to right: KcsA [protein data bank (PDB) code 3EFF] is a pH-dependent channel from bacteria; MthK (3LDC) is a Ca2+-dependent channel from bacteria; Kir2.2 (3JYC) is an inward rectifier potassium channel from mammals; K2P (4WFE) is a two-pore domain channel from humans; and Kv1.2-2.2 (2R9R) is a voltage-gated Shaker potassium channel.

Historically, model molecules have produced dramatic advances in biological science. In the molecular study of ion channels, researchers found the Shaker potassium channel from Drosophila to be an appropriate object for mutational studies (Jan & Jan, 2012). Since then, huge numbers of mutation–function studies have been performed. After elucidation of its crystal structure, the KcsA potassium channel has been used because it is an archetypical channel that exhibits typical characteristics and shares most properties of potassium channels (MacKinnon, 2003).

The KcsA channel is a channel of bacterial origin (Streptomyces lividans; Schrempf et al. 1995). Each KcsA subunit is 160 amino acids long, making it one of the shortest channels. It contains two transmembrane segments, similar to the inward rectifiers, and the functional channel is formed by tetramerization (homotetramer). This channel is activated by intracellular acidic pH (Heginbotham et al. 1999), but the physiological relevance to the native stimulus in the bacterial membrane remains elusive. The KcsA channel is stable in various experimental conditions, which fulfils the requirements of a model channel.

Potassium channel structure

Since the first crystallisation of the KcsA channel, many crystal structures of ion channels have been registered with the protein data bank (PDB). Some examples of potassium channels are shown in Fig.1. To extract meaningful information, one must observe the structure in both a coarse-grained view (architecture) and a finer view (details of configurations).

Global architecture

Channel proteins are composed of identical subunits (homo-oligomers), similar subunits (hetero-oligomers) or multiple repeats of homologous domains, and these structural units are arranged symmetrically around the central axis. This arrangement is called rotational symmetry, and the pore exists along the axis (Fig.1).

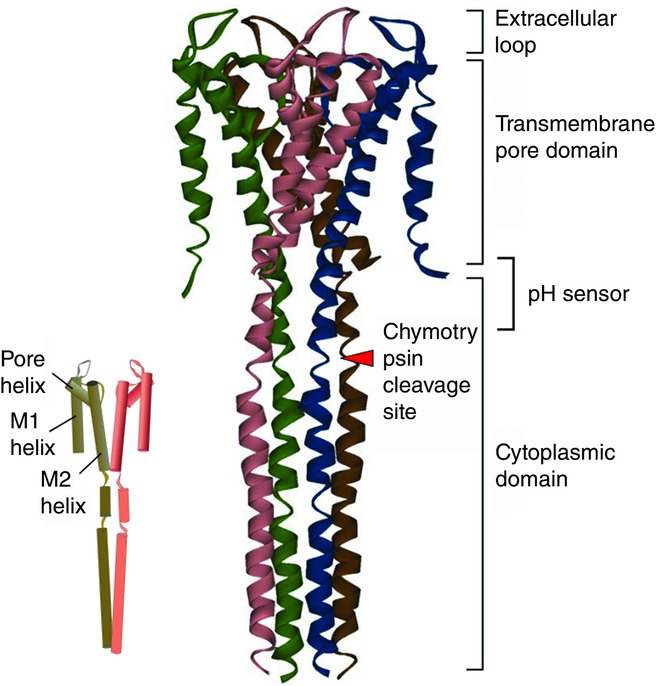

There are two domains within the KcsA channel (Uysal et al. 2011), namely the transmembrane pore domain and the cytoplasmic domain (CPD; Fig.2). The pore domain is most important for ion channels, distinguishing channels from other membrane proteins (Oiki, 2012a). The pore domain of the KcsA channel shows architecture similar to not only other potassium channels but also the superfamily of voltage-gated-like channels (MacKinnon et al. 1998). The compact pore domain is composed of bundles of α-helices (Doyle et al. 1998). There are two membrane-spanning helices, called M1 and M2, and a short helix called the pore helix (Roux & MacKinnon, 1999). The M2 (or inner) helix lines the inner half of the pore.

Figure 2.

The structure of the full-length KcsA channel and domain decomposition (PDB code 3EFF)

Each subunit is coloured differently. The red arrowhead indicates the chymotrypsin cleavage site. The inset indicates the helical arrangement of the subunit and the name of the helices in the pore domain. Only diagonal subunits are shown.

Generally, channels have a CPD with enormously varying size and shape (Fig.1). In the KcsA channel, the CPD is compact, formed by a helical bundle. In some channels, the CPD bears a chemical sensor, but the pH sensor of the KcsA channel is located at the interface between the transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains. Among the sensors, the voltage sensor forms an independent domain (voltage sensor domain) embedded in the membrane, where it senses the changes in the membrane electric field (Catterall, 2010).

Local configuration

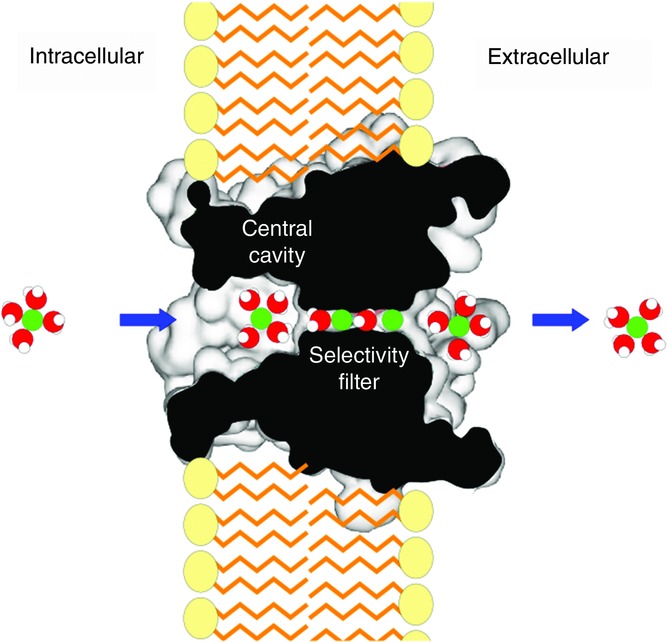

Here, I focus on the most essential pore domain of K+ channels. The ion permeation pathway or the pore exists along the axis of symmetry, but the pore size is not uniform along the pathway (Fig.3). The cytoplasmic side of the pore is wide, moving permeating ions towards the central cavity, and ions are kept fully hydrated in the wide pore, similar to those in the bulk solution. The pore size narrows to 3 Å in diameter for a length of 12 Å, called the selectivity filter, until it reaches the extracellular space. Upon entering the selectivity filter, the permeating ion must shed most of its hydrating water, and the ions and water molecules are aligned in single file. The selectivity filter is sufficiently narrow that the ions interact intimately with the pore-lining structure.

Figure 3.

Ion permeation pathway through the KcsA channel

The longitudinal section of the channel shows the profile of the pore structure. A hydrated ion advances from the intracellular space to the central cavity. Upon entering into the selectivity filter, most of the hydrating water molecules are shed.

Decomposition

Each domain of channel proteins exhibits some structural and functional independence. Closer examination of each domain is required for the subsequent reconstitution of domains for integrated channel activity.

‘Bare’ channels

Channel proteins can be extracted from the native membrane by replacing the surrounding lipids with detergent molecules (detergent-solubilized channels). Even in the absence of the membrane, channel proteins exhibit structural changes upon stimulation. Detergent-solubilized channels have frequently been used for spectroscopic methods, such as fluorescence measurements (Blunck et al. 2006), nuclear magnetic resonance (Chill et al. 2006; Imai et al. 2012), electron paramagnetic resonance (Perozo et al. 1998) and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (Furutani et al. 2012; Yamakata et al. 2013), as well as the surface plasmon resonance (Iwamoto et al. 2006) and diffracted X-ray tracking (DXT) methods (Shimizu et al. 2008). If experiments using bare channels produce different results from those using membrane-embedded channels, the differences should accentuate the influence of membranes on the channel (Imai et al. 2012).

Structural decomposition

Decomposing the channel structure into domains and examining their function represents a valid ‘divide and conquer’ strategy (Oiki et al. 1988). In the KcsA channel, the CPD can be deleted without losing the channel function. Chymotrypsin cuts the channel at residue 125 (Fig.2; Doyle et al. 1998); the N-terminal moiety (CPD-truncated channel) includes the transmembrane pore domain and the pH sensor, and it exhibits similar channel activity to that of the intact (or full-length) channel. The CPD-truncated channel is, thus, the minimal functional unit of the K+ channel. Researchers have frequently used this CPD-truncated channel to characterize the channel features. For example, the first crystal structure was attained using the CPD-truncated channel (Doyle et al. 1998). Retrospectively, the postcrystal age started from the minimal functional pore domain.

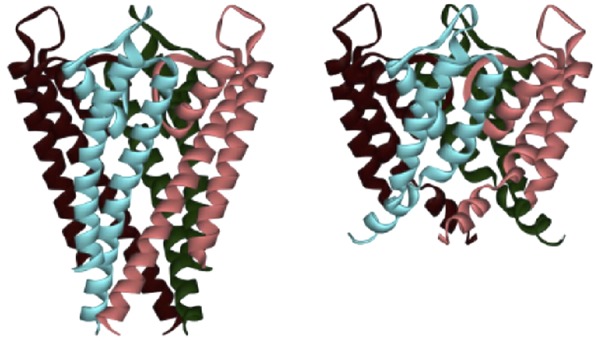

In the BC (before crystal) age, one may imagine the gate as a structural moving part that either leaves open or obstructs the pore. The inactivation gate, especially for the Shaker K+ channel, known as the N-type inactivation ball, is a typical example, and the inactivation is eliminated by removing the ball through cutting the linker to the ball (Hoshi et al. 1990). The Shaker channel exhibits slow inactivation even after removal of the N-type inactivation, which is called the C-type inactivation. The C-type inactivation is modified by extracellular K+ concentration, and involvement of fine conformational changes of the selectivity filter has been suggested (López-Barneo et al. 1993; Shimizu et al. 2003). The C-type inactivation is shared in many K+ channels, including the KcsA channel. The C-type inactivation could not be removed until fine configurations of the selectivity filter were elucidated. Also, the activation gate cannot be eliminated by mutational manipulations. Recent studies indicate that the gate is not simply a moving part attached to an otherwise rigid structure. In order to start understanding the gating, crystal structures for open and closed conformations are prerequisite, and they are now available (Fig.4; Cuello et al. 2010c). The contrasting architectures of the open and closed channels demonstrate the changes responsible.

Figure 4.

Closed and open structure

The bundles of M2 helices are tightly crossed at the cytoplasmic end (bundle crossing) in the closed conformation (left). This tight crossing is relaxed with a slight bending of the M2 helix (right). In the open conformation, the cytoplasmic ends of both M1 and M2 helices are not fully resolved. This structural change is called the activation gating. (PDB code 1K4C and 3F5W.)

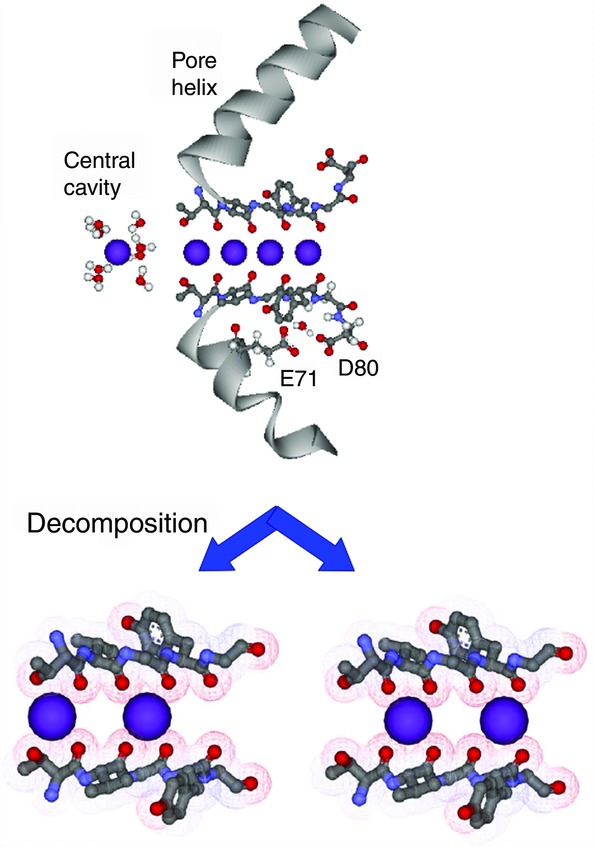

Decomposition of the ion distribution in the selectivity filter

In contrast to the gating, the channel allows millions of ions to permeate through the open pore without substantial changes in the pore structure. Electrophysiologically, permeation through potassium channels has been characterized as a multi-ion pore, bearing multiple ions simultaneously in the pore during permeation (Hodgkin & Keynes, 1955; Hille & Schwarz, 1978). Permeation processes in the selectivity filter are closely related to its fine structure. The selectivity filter is lined with backbone carbonyls, and the side-chains do not contact the permeating ions (Fig.5). Equally spaced carbonyls from four backbone strands provide four nearly equivalent cuboid spaces (Fig.6A). In each space, a K+ ion is co-ordinated by eight carbonyl oxygens, in what is called the cage configuration (Shrivastava et al. 2002), which is similar to hydrating water around ions in the bulk solution. Bare K+ fits in the cage space, realising the classical snag-fit model at the atomic scale (Bezanilla & Armstrong, 1972). A water molecule also occupies the cage site. Upon permeation, it is plausible that K+ occupies one of the cage sites and then jumps to adjacent sites (discrete jumps) rather than continuously advancing through the pore.

Figure 5.

The selectivity filter and K+ ions therein

In the crystal structure of the KcsA channel at high K+ concentration (PDB code 1K4C), four K+ ions are aligned adjacently in the selectivity filter (upper panel). This arrangement is not physically feasible and was decomposed into two alternate arrays (lower panel). Transitions between these two configurations yield net ion flux. To the left of the selectivity filter, K+ occupies the central cavity where it is fully hydrated. The rightward (or outward) shifts of ions generate outward currents.

Figure 6.

Fine configurations of the selectivity filter and the permeation model

A, the cage configuration. The backbone carbonyls from four subunits form four cuboid spaces in series, and these spaces are the right size for co-ordinating a K+ ion (radius, 1.3 Å). B, the eight-state ion permeation model. Eight of ion-distribution states were deduced from the following two requirements: (i) each of the four binding sites is occupied by either an ion or a water molecule; and (ii) ions cannot occupy adjacent sites. Transitions between the states driven by the electrochemical potential gradient generate net ion and water flux.

To examine the processes of ion permeation, snapshots of permeating ions in the cage sites of the selectivity filter are most informative. In the frozen crystal, however, these snapshot ion distributions cannot be resolved; instead, several snapshots are merged in the equilibrium condition, providing superimposed images of multiple different ion distributions in the selectivity filter. In the high-resolution crystal structure of the KcsA channel at high K+ concentration (PDB code 1K4C; Zhou et al. 2001), four K+ ions are aligned adjacently in the selectivity filter (Fig.5).

What can we deduce from this merged ion distribution? Here, this distribution of four adjacent K+ ions is represented as K-K-K-K, indicating an array of K+ distributions on the four cage sites from the intracellular to the extracellular direction. Morais-Cabral et al. (2001) deciphered this distribution into K-w-K-w and w-K-w-K (w, water; Fig.5). This decomposition is the most insightful, leading to a novel mode of ion permeation, as follows: K-w-K-w moves rightwards (or outwards) in unison one step towards w-K-w-K, by which a water molecule is released outside and supplied from inside; in the reverse transition, K+ is supplied from inside and is released outside. Repeated transitions yield a net ion flux. At low K+ concentration, the number of K+-occupied sites decreases, and permeation occurs through one-ion occupied states. Accordingly, the permeation process is decomposed into several ion occupancy states, involving two-ion occupied and one-ion occupied states and transitions among them, which can be described as the discrete-state Markov model (Fig.6B; Morais-Cabral et al. 2001; Ando et al. 2005; Iwamoto & Oiki, 2011; Oiki et al. 2011).

The alternate arrangements of K+ and water and the transitions between these configurations during permeation give one an insight into the fact that distinct numbers of water molecules are carried along with ions (Ando et al. 2005). Moreover, the defined binding sites for ion and water predict a defined flux ratio of ion and water. For example, transitions between K-w-K-w and w-K-w-K yield the net ion and water flux (J; number of ions or water molecules transferred per second) with a flux ratio of one to one (the water–ion coupling ratio, CRw–i; Jw/Ji). It should be noted that the CRw–i value is electrophysiologically measurable as the streaming potential (Levitt et al. 1978; Rosenberg & Finkelstein, 1978; Ando et al. 2005). Our experimental data demonstrated that the CRw–i values of potassium channels (HERG and KcsA channels) were nearly one at high K+ concentrations (Ando et al. 2005; Iwamoto & Oiki, 2011). These experimental data have served to decompose the permeation process into transitions among the snapshot distributions of ions and water in the pore.

Decomposition of the gating status

Functional decomposition

Functionally, activation and inactivation gating are defined from the macroscopic current measurements. Stimuli, such as depolarizing voltage or ligand application, induce increases in ionic currents (activation), and the current decays subsequently, even if the stimuli continue (inactivation). Before stimulation, channels are in the resting, closed state, and start to open upon stimulation. Channels spontaneously enter a non-conductive inactivated state. The activation gate opens when a sensor conveys a message to the activation gate through the conformational change across the channel protein, while the inactivation gate is modified by various factors, such that the rate of the inactivation is accelerated by extracellular low K+ concentration.

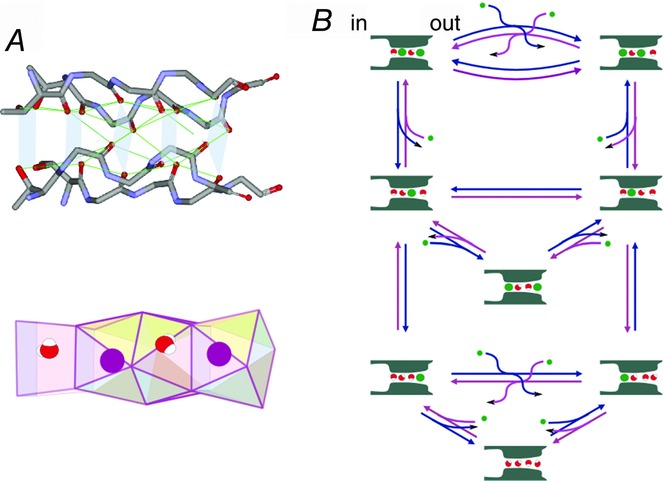

In the KcsA channel, an acidic pH jump at the intracellular side activates the channel, followed by the inactivation (Fig.7). In contrast, a depolarizing pulse induces an ‘apparent’ activation. In the KcsA channel, the inactivation gate rather than the activation gate is voltage dependent (Cordero-Morales et al. 2006a), and more prominent inactivation at negative potentials is recovered to the active state upon depolarization. The recovery from the inactivation is accelerated at low K+ concentration. Additionally, the activation facilitates the inactivation (activation–inactivation coupling; Cuello et al. 2010b). These interactions and modifications of the gating make the K+ channels highly sensitive to environmental changes.

Figure 7.

pH dependence and voltage dependence of the macroscopic KcsA current

Huge numbers of KcsA channels were reconstituted into a lipid bilayer. A, pH-dependent activation followed by inactivation. The pH of the intracellular solution was stepped from 7.5 to 4.0. Very slow inactivation observed in the wild-type channel is completely eliminated in an inactivation-free E71A mutant. B, voltage dependence of the KcsA gating at pH 4.0. The time course of the ‘apparent’ activation depends on the K+ concentration. This is interpreted that the inactivation is more prominent at zero, and the apparent activation represents recovery from inactivation at positive potentials. [Adapted from Iwamoto & Oiki (2011, 2015).]

The activation gate and inactivation gate

For the KcsA channel, the closed, open and inactivated structures have been elucidated (Fig.4; Cuello et al. 2010c). There are several charged residues in and around the pH sensor (Thompson et al. 2008; Cuello et al. 2010a; Posson et al. 2013). At neutral pH, the charged residues form a hydrogen-bonded chain, rendering the M2 helical bundle crossed at the cytoplasmic end. At acidic pH, the bundle crossing is relaxed, and the M2 helix is bent at the middle, leaving a wide opening for ion access into the channel cavity. pH-induced structural changes in the bundle of the M2 helices underlie the activation gating.

The pH sensor of the KcsA channel is located close to the activation gate, and the sensor readily transfers the message to the activation gate. However, in general, a sensor and the activation gate are located apart, in which conformational changes of the sensor upon binding of a ligand are transferred towards the activation gate, leading to opening of the activation gate. During this process, a conformational wave travels across the protein structure, and the route of the conformational wave in the channel protein has been elucidated (Fig.8; Grosman et al. 2000).

Figure 8.

Domains of channel proteins and interdomain signal transfer

Conformational changes inside domains are transferred to other domains, and the messages converge to the pore domain, where signals are converted to the current output.

The channel structure is a result of huge numbers of atomic configurations because of their freedom of motion, but those configurations are degenerated, and we consider that there are countable numbers of conformations. Gating has been successfully described using a limited number of conformational states and transitions among them (discrete-state Markov model; Zagotta et al. 1994; Horrigan & Aldrich, 2002; Chakrapani et al. 2007). This is a kinetic decomposition of the gating conformational change.

The inactivation-free channel

In the case of the KcsA channel, crystal structure revealed that the selectivity filter is collapsed at low K+ concentration, and this non-conductive conformation was suggested to be the inactivated conformation. There are charged residues, E71 and D80, located in the back of the selectivity filter (Fig.5), and the non-conductive, collapsed conformation is induced when the two residues form hydrogen bonds. Thus, by replacing E71 with uncharged residues, the channel maintains its active conductive state at acidic pH, and the inactivation is completely eliminated (Cordero-Morales et al. 2006b). In the absence of the inactivation, the single-channel current traces reflect behaviour of the activation gate, and the pH-dependency of the activation gating has been examined using this mutant channel.

Reconstitution

Reconstitution indicates building from existing parts. In the early days of the study of ion channels, pioneering electrophysiologists measured the ionic current and decomposed the raw current traces into attributes of permeation and gating. Finally, the permeation and gating features were integrated into the Hodgkin–Huxley differential equation to reproduce the action potential (Hodgkin & Huxley, 1952). This represents the most successful example of reconstitution.

Channel proteins have been built out of elimination and consolidation strategy through the process of molecular evolution, which is nature’s reconstitution experiment. Structural units for specific functions were refined, and these refined domains have been swapped among proteins to produce better functional channels (Liu & Eisenberg, 2002; Das et al. 2010). Viewing the channel from molecular evolution respects, one may have an idea of how the present channel is designed and built and may also have an idea of designing a channel from scratch. Ideas of the reconstitution are solidified only when the practical or experimental reconstitution system works.

Channel–membrane reconstitution

The classical term ‘reconstitution’ signifies the incorporation of isolated channel proteins into an artificial membrane, by which purified and solubilized channels are returned to a membrane environment. However, the reconstituted membrane is not identical to the native membrane where the channel originated. In heterogeneous membrane channel function can be examined by varying lipid compositions. This simple, minimal reconstitution system, involving only electrolytes, the membrane and the channel, allows evaluation of the functional outcomes of reconstituted channels.

The reconstitution methods for channel proteins are summarized in Table1. Liposomes are the most popular experimental systems for membrane proteins, and have been used to examine the macroscopic behaviour of huge numbers of channels (Heginbotham et al. 1998; Yanagisawa et al. 2011; Rusinova et al. 2014). In contrast, planar lipid bilayer (PLB) methods allow both macroscopic and single-channel characterization (Fig.9B; Oiki, 2012b). In either the liposome or the PLB, the lipid composition of the bilayer membrane is readily changed, and the effects of lipids on the channels have been examined (Dart, 2010). Recently, nanodiscs have frequently been used (Bayburt & Sligar, 2010). With the diameter of a nanodisc, a single channel is allowed to be incorporated into the membrane (Banerjee & Nimigean, 2011). Nuclear magnetic resonance measurements have been performed using nanodiscs, and the conformational changes in various conditions were revealed (Imai et al. 2010). Additionally, single-particle structural analysis of the KcsA channel embedded in a nanodisc was performed (Banerjee & Nimigean, 2011).

Table 1.

Membrane reconstitution methods

| Methods | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Membrane features | Liposome | Liposome-patch | PLB | Nanodisc | DIB | CBB |

| Varied lipid compositions | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| Asymmetric membrane | ±* | − | + | − | + | + |

| Application of membrane potential | + | + | + | − | + | + |

| Membrane current measurements | − | + | + | − | + | + |

| Electrical background noise | n.a. | Low | High | n.a. | High | Low |

| Perfusion | − | Rapid | Slow | − | Slow | Rapid |

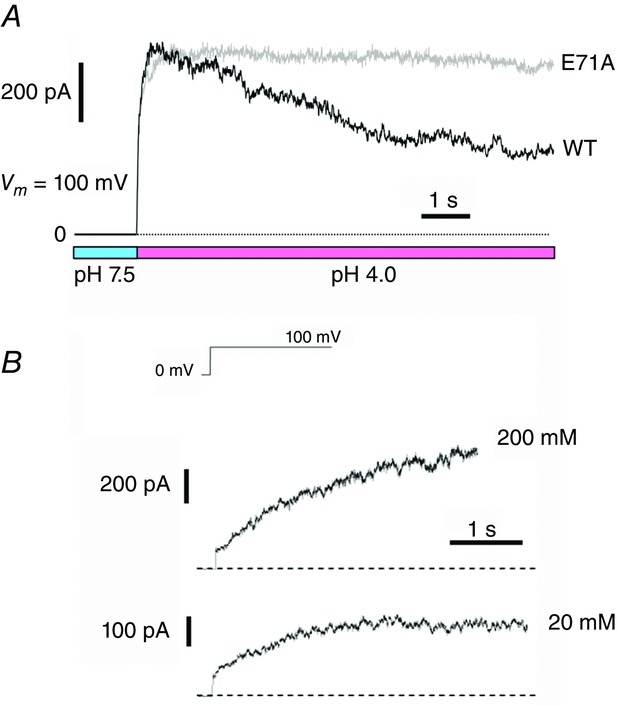

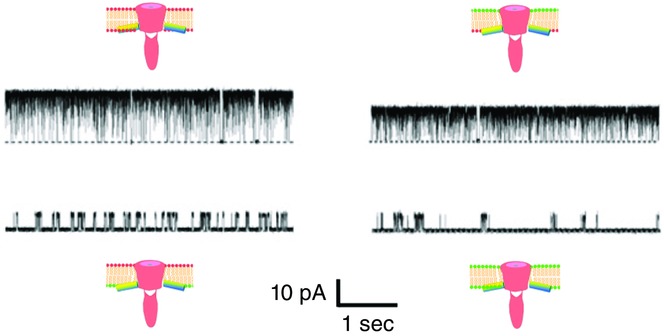

Figure 9.

Asymmetric membranes

A, the cell membrane is characterized by asymmetric compositions of lipids for the inner and outer leaflets of the membrane. B, an asymmetric membrane can be formed in the planar lipid bilayer using the folding method. Two monolayers having different lipid compositions are apposed at the hole made in a hydrophobic septum. C, asymmetric membranes are more readily formed using the recent technique called the contact bubble bilayer method. Water bubbles are blown into the oil phase from glass pipettes, and the lipid monolayer lines the oil–electrolyte interface. Two bubbles are attached to form the bilayer.

In the study of a channel, the membrane potential is the critical factor to be controlled. Planar lipid bilayer methods allow measurements of the single-channel current in voltage-clamp conditions. In contrast, liposomes allow application of the membrane potential in the following ways: (i) by imposing the concentration gradient of an ion across the membrane; and (ii) by incorporating ionophores into the liposome membrane for permeating the relevant ion. Accordingly, a diffusion potential is generated.

Recently, novel bilayer methods have been developed (Funakoshi et al. 2006; Bayley et al. 2008). In the droplet interface bilayer (DIB) method, electrolyte droplets are immersed in the oil phase. Lipid monolayers are formed at the oil–electrolyte interface, and two monolayers are attached to form bilayers. This method requires less elaborate techniques than the conventional PLB method. We have developed another method, called the contact bubble bilayer (CBB) method, by exploiting benefits of the conventional patch-clamp (including the liposome-patch) method and the PLB method (Fig.9C; Iwamoto & Oiki, 2015). The CBB method allows formation of various lipid compositions, even for asymmetric membranes, whereas the pressure-controllable pipettes render the membrane shape manipulable, such that membrane curvature and tension can be controlled. Also, unlike DIB, low-noise recordings under rapid perfusion are attained with the CBB method (Fig. 7A).

Reconstitution strategy

Now, with the practical experimental methods in hand, it is possible to consider the channel reconstitution at three hierarchical levels: channel–membrane reconstitution (see ‘Membrane–channel interaction’); reconstitution of channel parts (see ‘The M0 helix’); and collective channel reconstitution into membrane (see ‘Membrane-embedded structure’). For the KcsA channel, purified proteins are readily incorporated into the membrane and exhibit pH-dependent channel function. In addition to the full-length channel, the CPD-truncated channel also shows similar channel function (Cortes et al. 2001a), making it the starting minimal unit for reconstituting channel function.

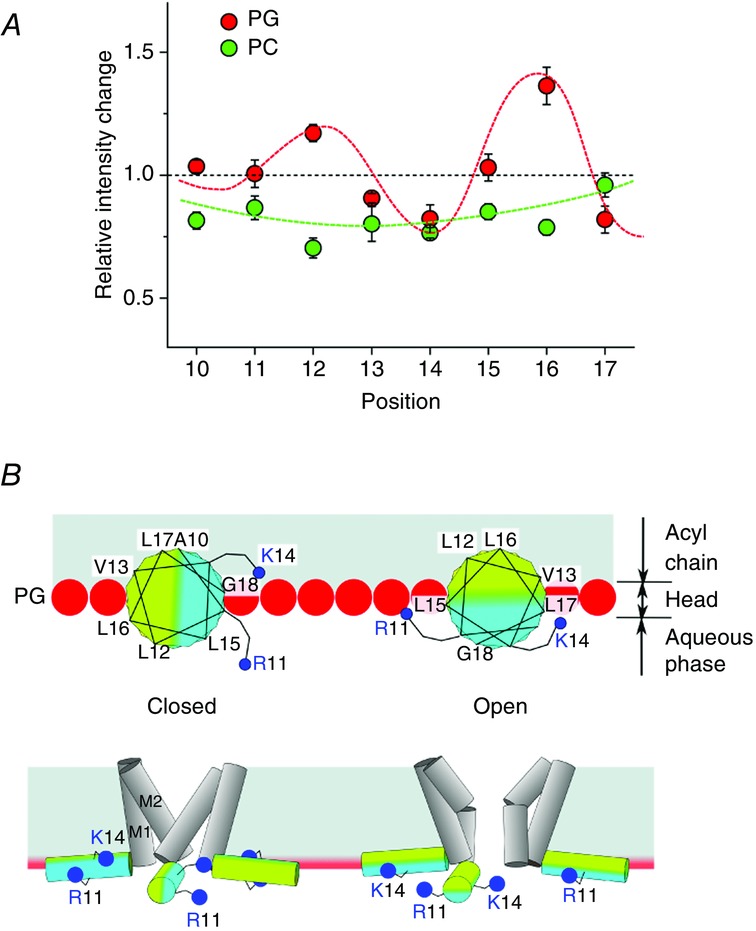

Membrane–channel interaction

The effects of lipids on channel activity have been studied extensively (Dart, 2010; Hoshi et al. 2013; Poveda et al. 2014). Reconstitution methods provide simpler and distinct membrane environments than experiments on the cell membrane. Researchers are motivated to examine the effects of lipids on KcsA channel activity because lipid molecules were co-crystallized with the channel (Fig.10; PDB code 1K4C; Zhou et al. 2001). Generally, the lipids surrounding the membrane proteins are categorized into annular and non-annular lipids (Lee, 2004; Triano et al. 2010; Poveda et al. 2014). In the KcsA channel crystal, four lipid molecules, later identified as phosphatidylglycerol (PG), are intercalated in the grooves between subunits on the outer part of the membrane-facing surface of the transmembrane domain (Fig.10). This apparently long-lived binding of lipids (non-annular) on the channel surface suggests a crucial role of the lipids for channel function.

Figure 10.

The transmembrane pore domain of the KcsA channel co-crystallized with lipids

The acyl ends of phosphatidylglycerol are not resolved (PDB code 1K4C).

Single-channel recordings were performed with defined membrane compositions of the planar lipid bilayer at pH 4. We used the inactivation-free mutant, E71A, to demonstrate the status of the activation gate (Iwamoto & Oiki, 2013). In the pure PG membrane, the KcsA channel keeps the activation gate open nearly 100% of the time (open probability ≈ 100%). In contrast, the channel shows an open probability of 10% in the phosphatidylcholine (PC) membrane (Fig.11). Negatively charged lipids, such as phosphatidylserine and phosphatidic acid, are effective for keeping the activation gate open. The location of the bound PG on the channel crystal has suggested that the PG in the membrane outer leaflet may affect the gating. To examine this possibility, experiments in asymmetric membranes were performed.

Figure 11.

Single-channel current recordings of the non-inactivating E71A mutant in symmetric and asymmetric membranes at +100 mV

The lipid head group coloured red represents phosphatidylglycerol, and that coloured green represents phosphatidylcholine. The open probability is nearly 100% when phosphatidylglycerol exists in the inner leaflet. Different single-channel conductances in different membranes are accounted for by the surface potential rendered by the lipid head groups. The dotted lines indicate the zero-current level. [Adapted from Iwamoto & Oiki (2013).]

Asymmetric membrane

The cell membrane is asymmetric in its composition. PC is enriched in the membrane outer leaflet, whereas negatively charged lipids are present predominantly in the inner leaflet. This general rule, however, does not exclude the presence of PG in the outer leaflet, which is revealed from the crystal structure (Fig.10). Technically, asymmetric lipid bilayers are readily formed by the PLB (Montal & Mueller, 1972), DIB and CBB methods; two monolayers with different lipid compositions are fused to form a bilayer.

When the bilayer membrane is formed with PG in the inner membrane leaflet, the channel maintains high activity whether the outer leaflet contains PC or PG. However, for the opposite asymmetric membrane (PCin and PGout), the channel activity was similar to that of the pure PC membrane (Iwamoto & Oiki, 2013). These results indicate unequivocally that the negatively charged lipids in the membrane inner leaflet are required for maintaining the open gate. Nevertheless, a functional role for the crystallographically found PG on the outer membrane interface remains elusive.

Lipid sensor?

How does the KcsA channel sense the lipid composition in the inner membrane leaflet? The KcsA channel discriminates based on the charged moiety of the lipid head group rather than on its chemical nature; thus, it is plausible that lipid sensing is based on electrostatic interactions. To detect the interaction site, each positively charged residue in the KcsA channel (24 positively charged residues) was mutated to neutral (scanning mutagenesis), and single-channel current recordings were made. Among the mutants, we could localize the relevant part of the channel for the lipid interaction, i.e. the N-terminal region called the M0 helix. With the neutralization of these sites, the mutant channels yielded low open probability (Iwamoto & Oiki, 2013).

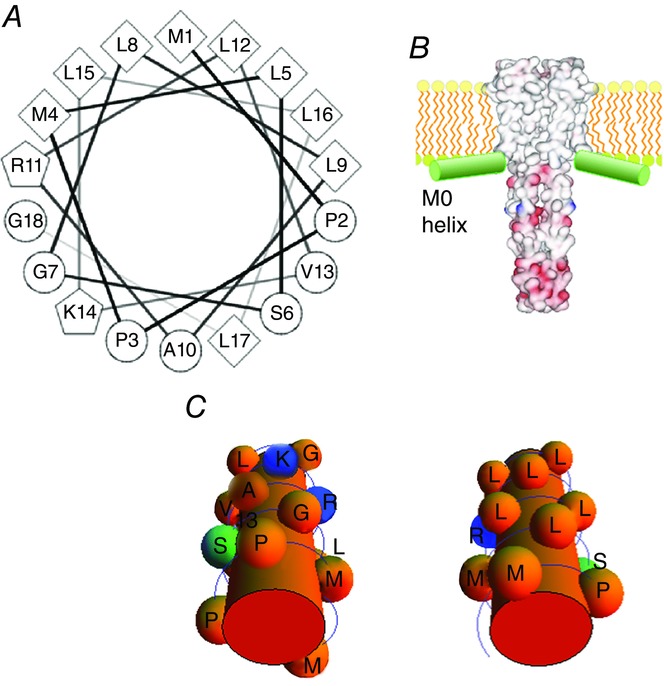

The M0 helix

In the crystal structure, some parts often remained unsolved because of reasons including fluctuation of the relevant structure in the crystallization conditions. In the case of the KcsA channel, the N-terminal M0 helix remained unresolved. Our identification of the important role of the M0 helix reminds us that functions of ‘invisible’ parts are frequently overlooked.

The M0 helix is an amphipathic helix, consisting of hydrophobic residues in one side of the helix, whereas the opposite side includes two positively charged residues (R11 and K14; Fig.12). An electron paramagnetic resonance study revealed that the M0 helix is localized at the membrane interface (Cortes et al. 2001a). Such membrane-anchoring amphipathic helices are frequently observed in membrane proteins (Hansen et al. 2011), and their functional relevance has been reported (Li et al. 2013).

Figure 12.

The amphipathic M0 helix as a lipid-sensing antenna

A, the helical wheel representation of the M0 helix. B, a plausible orientation of the M0 helix in relationship to the KcsA channel structure. C, the hydrophilic and hydrophobic sides of the M0 helix.

Here, we found that the positively charged residues on the M0 helix interact with negatively charged lipids in the membrane inner leaflet to stabilize the open-gate structure. Negatively charged lipids on the inner leaflet should accumulate around the KcsA channel and play an integral role in the channel activity.

Membrane-embedded structure

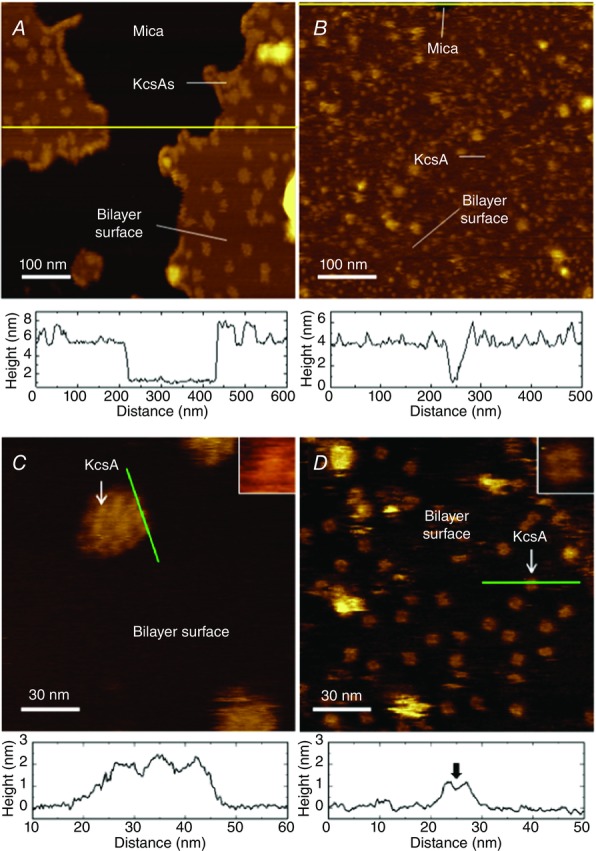

In order to understand in situ channel activity, the membrane-embedded structure is a prerequisite, while structural information is mostly attained without the membrane. Atomic force microscopy (AFM) allows the measurement of the membrane-embedded channel structure at the single-molecule level in more physiological conditions, such as at room temperature (Scheuring et al. 2005; Jarosławski et al. 2007; Shinozaki et al. 2009; Yamashita et al. 2013).

An AFM experiment was performed for the KcsA channel reconstituted into the lipid bilayer (Sumino et al. 2013). First, KcsA was reconstituted into liposomes, in which the channels are embedded in the membrane with the same orientation, facing the cytoplasmic domain inside the liposome. This uniform orientation has been proved by functional measurements (Cortes et al. 2001b). Giant liposomes are formed from KcsA-reconstituted liposomes, and the channel activity is measured with the liposome-patch experiment. Single and macroscopic KcsA currents have revealed that all the membrane-embedded channels are oriented with their pH sensor inside the liposome, because currents are elicited only if the intraliposome solution is rendered acidic.

The channel-reconstituted liposomes are attached to a mica surface, and the broken liposomes spread on the surface; thus, the channels should be oriented with their cytoplasmic side upward. In these experiments, the cytoplasmic domain, which potentially obstructs the view, was deleted to observe the open gate structure. Fragments or irregular islands of the bilayer membrane appear as flat terraces on the mica surface (Fig.13A and B), and AFM showed that the cytoplasmic end of the channel protruded from the membrane surface.

Figure 13.

Structure of the cytoplasmic domain (CPD)-truncated KcsA channel embedded in membranes

Atomic force microscopy images were taken at neutral pH (A and C) and at acidic pH (B and D). The images are colour-coded according to height. A, the bilayer membrane appears as a flat terrace or irregular islands on the atomic-flat mica surface. The height profile (lower panel) along the yellow line shows the thickness of the membrane (4 nm), and the cytoplasmic end of the CPD-truncated channel is protruding from the surface of the membrane. Observed particles on the membrane have a relatively larger size compared with that at acidic pH. B, the KcsA channels are dispersed almost evenly on the membrane surface. The membrane covers almost all the field of view except for the very top, where the height profile is attained. Bright and large spots show very high profile, and their entity cannot be identified. C, with a higher magnification, a particle on the membrane (A) is resolved as a cluster of channels. The profile along the green line indicates the height profile from the membrane surface, indicating three closely located individual channels. Inset, a three times enlarged view of the arrowed KcsA channel. D, at acidic pH, KcsA channels are spontaneously dispersed on the membrane surface with their gate open. The profile along the green line indicates that the channel length was shortened, and a dip is seen at the centre (arrow). Inset, a three times enlarged view of the arrowed KcsA channel, showing a central pore surrounded by four distinct subunits. [Adapted from Sumino et al. (2013).]

At acidic pH, individual channels were resolved, showing the open central pore surrounded by four subunits (Fig.3D). In contrast, the open gate was not resolved at neutral pH (Fig.3C). In addition to the opening of the activation gate at the cytoplasmic end, the profile of the channel in the z-axis or the height from the membrane surface revealed that the longitudinal length of the transmembrane pore domain was shortened substantially upon opening the gate. The AFM result reflects the structure of the KcsA channel in physiological conditions, indicating that the channel undergoes shortening during opening of the activation gate.

Re-animation

Freeze and release

Channels were frozen for detailed structural inspection, and the decomposed functional parts were reconstituted to operate the integrated molecular function. Next, the frozen channel was thawed to allow movement, which was then captured via time-lapse imaging. Single-molecule measurement techniques would provide more insight into the channel dynamics.

Before investigating global structural changes for the gating, I first address the ion permeation process using computer simulations. In the previous section, I decomposed the ion distribution into snapshots. In contrast, the atomistic-scale pore structure permits a bottom-up calculation of the ion permeation process. Given the atomic co-ordinates of the open pore, theoretical and simulation techniques have elucidated interactions between ions and channels (Chung et al. 1999; Phongphanphanee et al. 2014). In particular, molecular dynamics simulations have been used to reproduce the permeation event by solving the Newtonian differential equation, calculating the forces between all the pairs of constituting atoms, hence the motions of the atoms (Berneche & Roux, 2001; Jensen et al. 2010). Insights into the ion permeation and selectivity mechanism have been provided (Fowler et al. 2008; Egwolf & Roux, 2010). For example, the dehydration of ions upon entering into the selectivity filter has been captured at the picosecond time scale. Also, movements of multiple ions in the selectivity filter were examined, leading to understanding of the atomic scale knock-on mechanism (Hodgkin & Keynes, 1955). These elementary motions are integrated into ion distribution states and transitions among them. These mesoscopic levels of description for ion permeation connect elementary steps of ion movements and the single-channel conductance (Oiki et al. 2010; Kasahara et al. 2013).

For the gating, a recently developed molecular dynamics-specialized computer predicted the conformational changes of the voltage-gated potassium channel upon a voltage change (Jensen et al. 2012).

Global conformational changes upon gating

Gating conformational changes involve local configurational changes towards the global architectural changes, encompassing a broad spectrum on the spatial and temporal scales. For inactivation, narrowing the pore size within the ångström range turns the selectivity filter non-permeable. In contrast, opening of the activation gate has been reported to be accompanied by rearrangement of the transmembrane helices of the pore domain.

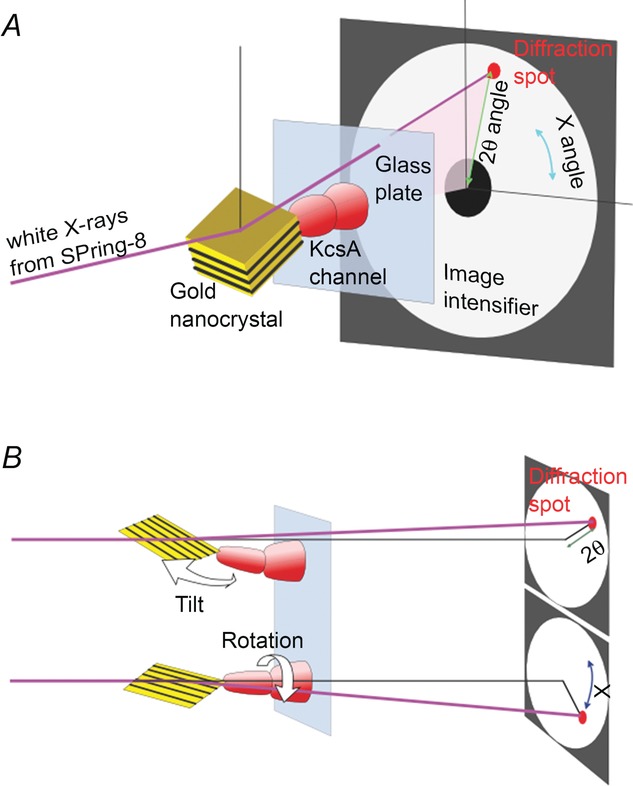

Diffracted X-ray tracking method

To trace dynamics of conformational changes of the channel gating, we have established the DXT method (Shimizu et al. 2008; Oiki et al. 2012). Crystallography is the highest spatial resolution method for the protein structure, and the underlying principle is X-ray diffraction. Huge numbers of channel proteins are aligned on a three-dimensional lattice (crystal), and irradiated X-rays elicit diffraction spots from the lattice planes. Based on the pattern of the diffraction spots, the averaged atomic co-ordinates of the channel proteins are deduced. We have applied this principle to the tracing of channel dynamics, which is generally known as the dynamic Laue method (Šrajer et al. 2001). In the DXT method (Fig.14), however, X-rays are diffracted from a gold nanocrystal attached to a single channel protein rather than from huge numbers of latticed proteins (Sasaki et al. 2000). During gating, each channel protein changes its conformation, and the attached nanocrystal changes its pose and thus casts a diffraction spot in a different position. Therefore, tracing a diffraction spot on the image intensifier in a time-lapse protocol represents orientation changes in the nanocrystal that report the conformational changes of the channel protein.

Figure 14.

The principle of the diffracted X-ray tracking (DXT) method

A, High-flux white X-rays from a synchrotron radiation facility (SPring-8) are used to irradiate the channel. The X-rays are diffracted by the gold nanocrystal attached to the channel. The image intensifier is located downstream, and the centre of the recording plane is masked in order to protect the image intensifier from X-ray damage. The glass surface of the sample is set vertical to the X-ray beam such that the channels fixed on the glass surface are oriented with their longitudinal axis parallel to the X-ray beam. Diffraction spots are recorded by the image intensifier, and the motion of the diffraction spot on the polar co-ordinate represents conformational changes in the channel protein. White X-rays are prerequisite in the DXT method such that a diffraction spot is elicited continuously even when the channel tilts, in which the diffraction spot is yielded only if the relevant wavelength is involved in the X-ray spectrum. B, the modes of motion of the nanocrystal and those of the diffraction spots on the image intensifier. (Reprinted with permission from Shimizu et al. Cell 2008; 132, 67–78. Copyright 2008 Elsevier.)

In a typical sample preparation, KcsA channels are fixed through their four extracellular loops on a chemically modified glass surface. The channels are oriented upright on the surface, while they are allowed to change their conformation freely upon gating. At the C-terminal end of the channel, which is located at the top of the upright-fixed channel, cysteines are introduced, and the four cysteine residues from the tetrameric channel hold a gold nanocrystal with covalent bonds. The heart of the DXT method is based on state-of-the-art technology. A synchrotron radiation facility (SPring-8, Harima, Japan) elicits the highest ever flux of white X-rays. Even if the size of the gold crystal is in the nanometre range, the high flux of X-rays produces detectable diffraction spots, which are recorded with an X-ray image intensifier. Motion of the diffraction spots was recorded through a CCD camera with the video rate (30 frames s−1). An electrolyte solution of an arbitrary composition was overlaid on the sample with a micrometre thickness, which minimizes the background noise.

The position of the diffraction spot on the image plane is expressed as the polar co-ordinate. As the nanocrystal tilts by the angle θ from the channel axis, the diffraction spot moves along the radial direction (the angle 2θ) on the image plane (Fig.4B). When the nanocrystal rotates around the beam direction or the channel axis, the diffraction spot moves circumferentially on the imaging plane (the angle χ). Thus, the position and motion of the diffraction spot on the image plane (the circular polar co-ordinate (angles 2θ and χ) centred on the point of X-ray irradiation) represents posing orientation of the nanocrystal in the three-dimensional space (the spherical polar co-ordinate).

The spatial resolution of the DXT method is of the same order as that of crystallography, and its time resolution depends on the flux of X-rays and the sensitivity of the image intensifier. Originally, we recorded with the video rate, but recently, recording has become much faster. The DXT experiments were performed at room temperature.

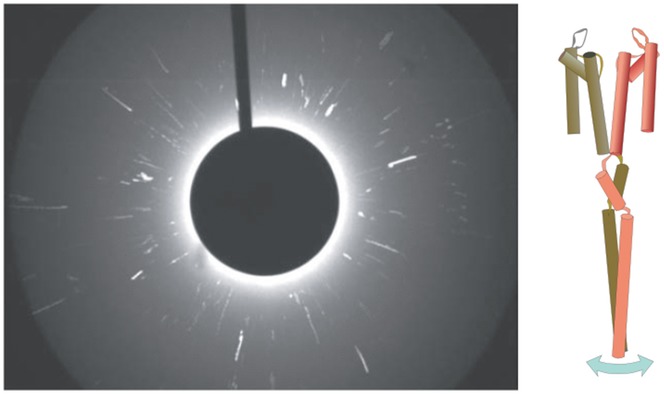

Global twisting motion upon gating

At neutral pH, at which the KcsA channel stays in the resting closed state, the diffraction spots fluctuate slightly along the 2θ axis within a few degrees during the recording time of 3 s. These motions represent slight tilting of the channel, generated by the random fluctuation of the channel structure (Fig.15; Shimizu et al. 2008). At acidic pH, we found that the diffraction spots moved circumferentially along the χ axis on the image plane, with concomitant fluctuations along the 2θ axis (Fig.16). This observation indicates that the channel undergoes rotational conformational changes around the channel axis upon gating. The range of the rotational angle is over several tens of degrees. During the recording time of 3 s, either clockwise or anticlockwise rotational motions were observed, and we call this gating transition the global twisting and untwisting motion. The twisting motions were detected even after deleting the CPD, which indicates that the twisting conformational change originates from the pore domain and that this motion is transferred along the CPD towards the C-terminal end.

Figure 15.

A DXT image for the KcsA channel in the closed state measured at neutral pH

The DXT images recorded in the video rate were superimposed, giving trajectories of the diffraction spots during recordings for 3 s. Most trajectories move radially, indicating that the channel tilts its conformation within a few degrees. Inset, a schematic representation of the KcsA channel, demonstrating two diagonal subunits. (Reprinted with permission from Shimizu et al. Cell 2008; 132, 67–78. Copyright 2008 Elsevier.)

Figure 16.

The global twisting motion upon opening and closing of the activation gate measured at acidic pH

The trajectories move circumferentially, indicating that the rotational motions occur around the channel axis. The range of the twisting was over several tens of degrees. Inset, the KcsA channels in the closed (left) and open conformations (right). The M2 helices form the bundle crossing for the closed conformation, and relaxation of the bundle allows formation of the ion permeation pathway towards the central cavity. This rearrangement of the helical bundle was detected as the global twisting motion by DXT. (Reprinted with permission from Shimizu et al. Cell 2008; 132, 67–78. Copyright 2008 Elsevier.)

Tetrabutylammonium is an open-channel blocker of potassium channels, making the channel non-conductive through binding at the opening of the selectivity filter in the central cavity. In the presence of tetrabutylammonium at acidic pH, DXT revealed that the twisting motions were not detected, indicating that the gating motions were locked by tetrabutylammonium. This result was unexpected because electrophysiological results are readily explained by the blocking of the channel, and events underlying the non-conductive blocked state have not been discussed. Additional information derived from the surface plasmon resonance method indicates that the tetrabutylammonium-blocked channel is locked in the open-gated conformation (Iwamoto et al. 2006).

With spatial resolution at the ångström level, we could trace trajectories of the conformational change of single channel proteins using time-lapse imaging.

Revolution of the M0 helix

We have shown that the amphipathic M0 helix is located at the membrane interface, where it interacts with the negatively charged head group of the lipids in the membrane inner leaflet, by which the open state of the activation gate is stabilized. To examine how the M0–lipid interaction relates to the activation gating, we used a fluorescence method to detect behaviours of the M0 helix.

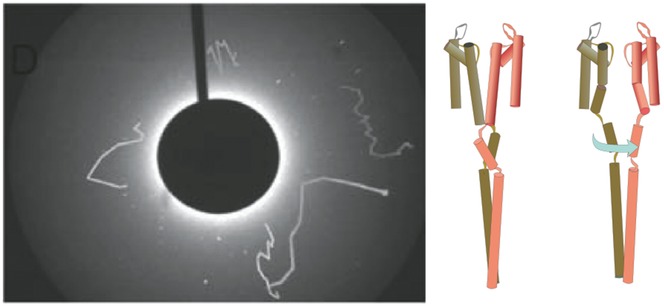

Tetramethylrhodamine (TMR) is a fluorescent probe that elicits more intense fluorescence in hydrophobic environments. Tetramethylrhodamine was introduced into the M0 helix one residue at a time (scanning TMR labelling), and spectroscopic measurements of fluorescence were performed from KcsA-reconstituted liposomes at neutral (closed state) and acidic pH (open state; Iwamoto & Oiki, 2013). The relative intensity changes in fluorescence [fluorescence intensity (FI); FIacid/FIneutral; RFI] indicate changes in the hydrophobic environment of the relevant residue that takes in the open and closed conformations. In Fig.17A, the red symbols indicate the measured RFI values for the TMR-labelled KcsA channels reconstituted in PG liposomes. For example, residue no. 16 shows a high RFI value, indicating that this residue is exposed to the hydrophobic environment at acidic pH but to the hydrophilic environment at neutral pH. In contrast, the opposite is true for the next residue, no. 17. The RFI was plotted along the residues of the M0 helix. Surprisingly, we found that the RFI exhibited a pattern with a periodicity of 3.6 residues per cycle. This periodicity suggests that the M0 helix indeed takes an α-helix structure having 3.6 residues per turn. More importantly, the periodic result indicates that different sides of the amphipathic M0 helix face the membrane in the closed and open conformations. Thus, the result indicates that the M0 helix revolves around the helix axis upon gating, leading to the alternate exposure of the helix side to the membrane interface at neutral and acidic pH (Fig.17B).

Figure 17.

The roll-and-stabilize model of the M0 helix

A, the periodic pattern of the hydrophobici environment for residues in the M0 helix. Scanning labelling of the fluorescence probe [tetramethylrhodamine (TMR)] along the M0 helix from residue 10 to 17 was introduced. These TMR-labelled KcsA channels were reconstituted into liposomes composed of either phosphatidylglycerol (PG) or phosphatidylcholine (PC). Fluorescence intensity was measured at acidic and neutral pH, and the relative fluorescence intensity (RFI) was plotted for each labelled site (red, PG liposome; green, PC liposome). In the PG liposome, RFI demonstrated a periodic pattern of 3.6 residues per turn, whereas no periodic pattern was observed in the PC liposome. B, the revolving of the amphipathic M0 helix. The M0 helix faces the opposite helix sides in open and closed conditions, and in the open state the positively charged residues interact with the negatively charged lipids. This interaction stabilizes the open conformation. This M0 dynamic action is called the roll-and-stabilize model. [Adapted from Iwamoto & Oiki (2013).]

Similar experiments with PC liposomes were performed (green symbols in Fig.7A), and RFI did not exhibit the periodic pattern. In PC membrane, the open probability of the activation gate is low even at acidic pH. Thus, the results indicate that the revolution of the M0 helix is tightly coupled to the activation gating. In the PG membrane, the revolving motion renders the charged residues on the M0 helix (Arg11 and Lys14) interacting with the negatively charged head groups, which stabilize the open state of the activation gate. In contrast, the oppositely revolved M0 helix is buried in the hydrophobic environment of the membrane in the closed state. Gating-related revolving of a membrane-surface helix had been neither anticipated nor reported. We call this revolution of the M0 helix coupled to the activation gate the roll-and-stabilize mechanism.

Most cell membranes contain negatively charged lipids in the inner leaflet, and one may consider that the lipid sensing by the M0 helix might be futile as a regulatory process. However, the membrane is neither static nor homogeneous, and local depletion of negatively charged lipids may occur. The effect of lipid dynamics on channel activity is a challenging issue for future research.

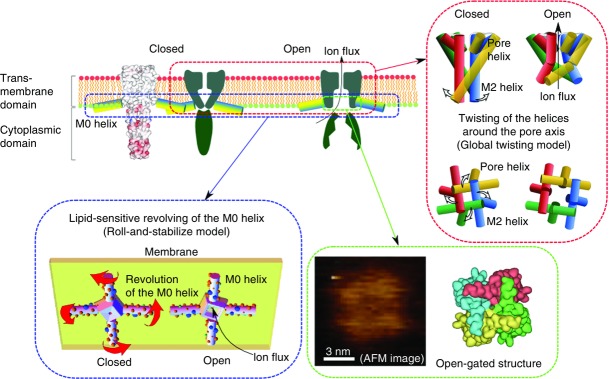

Integrated gating motion

Three modes of gating motions have been elucidated in the KcsA channel: global twisting; elongation and contraction; and M0 revolution. I am currently integrating the various aspects of these gating motions. The twisting and shortening motions are simply an outcome of the conformational change of the pore domain. These two modes along and around the channel axis for activation gating can be expressed as a spring-like motion. In contrast, the revolving action of the M0 helix was observed using macroscopic fluorescence measurements, and the coupling between the twisting motion of the pore and the revolving motion of the M0 helix has not been examined. More sophisticated single-molecule measurement techniques will be required to answer this question. Here, I present other aspects of dynamic behaviour of the KcsA channel in the membrane.

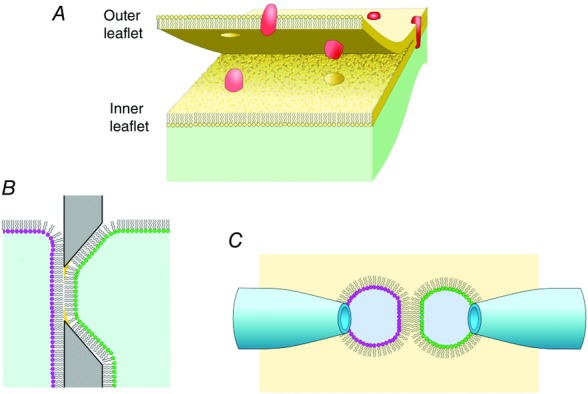

Collective dynamic behaviour in the membrane

In the cell membrane, proteins diffuse ceaselessly except in certain conditions, such as in lipid rafts (Edidin, 2003; Lingwood & Simons, 2010). The two-dimensional diffusion is more pronounced in the lipid bilayer membrane because of the more uniform membrane phase without the cytoskeleton. Using AFM, we have demonstrated the static picture of the membrane-embedded KcsA channel structure. A closer inspection of the AFM image (Fig.3) revealed that the KcsA channels are clustered at neutral pH. Several closed channels are resolvable within a cluster. However, at acidic pH the channels are dispersed on the membrane with the gates open. These observations suggest that clustering and dispersion occur in parallel to the gating conforma-tional changes of individual channels (Sumino et al. 2014).

Clustering of channel proteins on the cell membrane is frequently observed, such as for the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor at the muscle endplate (Wu et al. 2010) and the voltage-gated sodium channel at the node of Ranvier in neurons (Hedstrom & Rasband, 2006). In these cases, other molecules have been demonstrated to help assemble or maintain the clustering. In contrast, the KcsA channel forms clusters without the contribution of any other molecules (self-assembly).

The open channels at acidic pH are dispersed. The nearest neighbour distance between channels was 14 nm, indicating that the neighbouring channels never contact each other even if the M0 helices were to be extended radially. They may have repulsive interactions, either electrostatic in origin or mediated by the deformation of the membrane in the vicinity of each channel.

The AFM image of Figure 3 was measured more than 30 min after the pH of the electrolyte solution was neutralized, and the size of the cluster is not likely to grow further. The limited size of the cluster suggests that the channel–channel and channel–membrane interactions underlie the cluster formation. For the channel–channel interaction, SDS-PAGE demonstrated formation of supramolecular assembly exclusively at neutral pH (Sumino et al. 2014). Thus, the gating conformational change alters the channel–channel interaction.

Even at acidic pH, while most of the channels are dispersed, a fraction of the channels forms small clusters, in which the open gate structure could not be resolved. In these clusters, the height of the channel was substantially higher than that of an isolated open channel, whereas the height was substantially shorter than that of the closed channel at neutral pH. We consider that the clusters in acidic pH are in equilibrium with the dispersed channels, and the channels take on an intermediate conformation in these clusters.

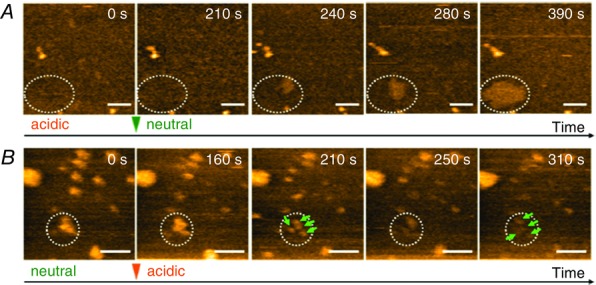

High-speed AFM is an appropriate method for investigating the dynamics of clustering and dispersion (Ando et al. 2001). We found that clustering and dispersion are reversible (Sumino et al. 2014). Each time the solution pH was changed, the channels became either clustered or isolated within 10 min (Fig.18). The clustering–dispersion dynamics will be investigated further with ongoing advancement of the high-speed AFM technology.

Figure 18.

Clustering–dispersion dynamics captured with high-speed atomic force microscopy

A, when the solution was changed from acidic to neutral pH, channels gradually clustered (white dotted oval) in the time scale of minutes. The dispersed channels are not clearly seen because of their low profile. B, acidification rendered the small clustered channels dispersed in a stepwise fashion. The channels shortened upon dispersion, which made the dispersed channels less visible. The number at the upper right corner indicates the recording time in seconds. (Reprinted with permission from Sumino et al. J Phys Chem Lett 2014, 5, 578–584. Copyright 2014 American Chemical Society.)

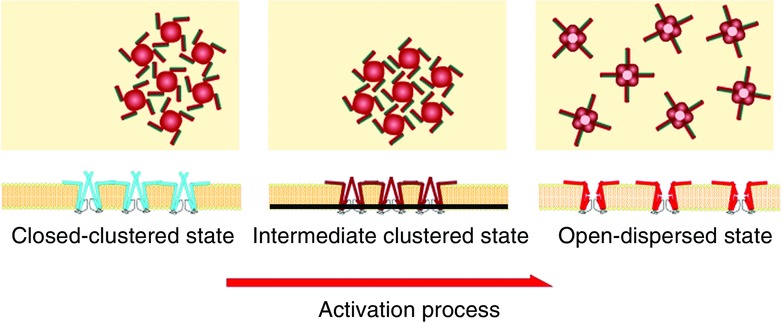

Reconstitution of re-animation

The dynamic behaviour of the KcsA channel on the membrane is summarized schematically (Fig.19). The closed channels at neutral pH are clustered. The interchannel distance indicates that the channels are interacting closely. At acidic pH, the channels are mostly dispersed such that they do not contact each other. Additionally, at acidic pH a fraction of the channels forms clusters, in which they take the closed, intermediate conformation. A hypothetical scenario is proposed for the channel dynamics. The presence of the cluster at acidic pH suggests that these clustered channels are intermediate products of the transition between closed-clustered channels and the individually dispersed open channels. By changing to acidic pH, the channels in the cluster change their conformation but still remained in the cluster. Then, channels become dispersed and the gate opens. The channel gating and the clustering–dispersion seem to be coupled tightly. Thus, dynamic interplay between submolecular gating conformational changes, involving global twisting, shortening–elongation and the M0 revolution, and supramolecular clustering–dispersion should be examined and integrated to draw a dynamic picture of the functioning channels.

Figure 19.

Gating-related clustering–dispersion dynamics

In the side view, the channels are shown upside down. In the top view, hypothetical orientations of the M0 helix in relation to the gating states are shown. The KcsA channels are clustered at neutral pH, at which the channels are closed. At acidic pH, most of the channels are dispersed with the activation gate open, whereas a fraction of the channels are clustered with the gate closed. In our hypothetical model, upon acidification the channel changes its conformation within the cluster, and then dispersed channels open the activation gate.

Concluding remarks

The molecular world of ion channels is dynamic. We begin with the crystal structure of the minimal functional unit, and the dynamic behaviours ranging from the intramolecular conformational changes to supramolecular clustering and dispersion in the membrane were reconstituted and re-animated (Fig.20).

Figure 20.

The gating dynamics of the KcsA channel

Upon activation, the helices in the pore domain rearrange, which leads to the global twisting motion with the activation gate open. At the same time, the pore domain shortens its longitudinal length. In parallel, the M0 helix revolves and interacts with the negatively charged lipids to stabilize the open state of the activation gate. The open-gated structure is resolved in membrane-embedded conditions. These conformational changes in the individual channels are related to the collective clustering–dispersion dynamics on the membrane. Abbreviation: AFM, atomic force microscopy.

To understand channel dynamics, capturing the molecular motion, ranging from the conformational changes to random diffusive motion in the membrane, is essential. However, we are still observing only a subset of the dynamics. Given that no single method can reveal all the dynamic aspects of functioning channels, we have applied various techniques. In addition to the structural elements to be reconstituted, the animations of the parts are now subject to reconstitution to obtain a dynamic picture of the functioning channel.

During the course of study, we have discovered unprecedented molecular events, such as the rolling of the M0 helix and the clustering–dispersion dynamics. Are these events specific to the KcsA channel? Are these events extreme and non-physiological and thus not worth examining in other channels? We believe that physiologically relevant events related to our findings will be found.

In molecular biology, many receptor proteins have been found, to which the intrinsic ligands frequently remain elusive. Finding native ligands for orphan receptors requires diverse screening and is generally considered a hopeless task. In most cases, the ligands are found accidentally. Our discovery of the gating-related clustering–dispersion dynamics of the KcsA channel is a similar case. This is an ‘orphan function’.

Interestingly, there has been a recent report of the function-related clustering of an ion channel on a plant cell (Eisenach et al. 2014). The guard cell outward-rectifying K+ channel is expressed on the guard cells in plant leaves. These channels are clustered when they are not active, and they are dispersed upon activation. Although the clustering of these channels was observed using fluorescence methods, dynamic clustering and dispersion occur on the cell membrane. Similar phenomena are likely to be found in animal cells.

The approach by physiologists of capturing moving objects is indispensable in the postcrystal age. With available techniques, including single-molecule measurement techniques, we are addressing challenging issues, through which the re-animated picture of the functional channel can be reconstituted into whole-channel dynamics.

Acknowledgments

I thank my collaborators, and thank Hirofumi Shimizu, Masayuki Iwamoto, Takashi Sumikama, Ayumi Sumino, Yuka Matsuki and Kenichiro Mita. I also thank Taeko Goto for her secretarial work.

Glossary

- AFM

atomic force microscopy

- CBB

contact bubble bilayer

- CPD

cytoplasmic domain

- CRw-i

water–ion coupling ratio

- DIB

droplet interface bilayer

- DXT

diffracted X-ray tracking

- PC

phosphatidylcholine

- PDB

protein data bank

- PG

phosphatidylglycerol

- PLB

planar lipid bilayer

- RFI

relative fluorescence intensity

- TMR

tetramethylrhodamine

Biography

Shigetoshi Oiki completed his doctorate at Kyoto University Faculty of Medicine in 1986. From 1986 to 1989, he studied model peptide channels using planar lipid bilayers in Mauricio Montal's laboratory at the Roche Institute of Molecular Biology and in Olaf S. Andersen's laboratory at Cornell University Medical College. Returning to Kyoto University, he started molecular biological studies of channel proteins. In the National Institute for Physiological Sciences (1992–1998), he studied the structure–function relationships of an inward rectifier K+ channel using the Xenopus oocyte expression system. Since 1998 in the University of Fukui, he has investigated the molecular mechanism of channel gating and permeation at the single-molecule level.

Shigetoshi Oiki completed his doctorate at Kyoto University Faculty of Medicine in 1986. From 1986 to 1989, he studied model peptide channels using planar lipid bilayers in Mauricio Montal's laboratory at the Roche Institute of Molecular Biology and in Olaf S. Andersen's laboratory at Cornell University Medical College. Returning to Kyoto University, he started molecular biological studies of channel proteins. In the National Institute for Physiological Sciences (1992–1998), he studied the structure–function relationships of an inward rectifier K+ channel using the Xenopus oocyte expression system. Since 1998 in the University of Fukui, he has investigated the molecular mechanism of channel gating and permeation at the single-molecule level.

Additional information

Competing interests

The author declares no competing financial interests.

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 26253014.

References

- Ando H, Kuno M, Shimizu H, Muramatsu I. Oiki S. Coupled K+–water flux through the HERG potassium channel measured by an osmotic pulse method. J Gen Physiol. 2005;126:529–538. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ando T, Kodera N, Takai E, Maruyama D, Saito K. Toda A. A high-speed atomic force microscope for studying biological macromolecules. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:12468–12472. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211400898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashcroft FM. Ion Channels and Disease. London: Academic Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S. Nimigean CM. Non-vesicular transfer of membrane proteins from nanoparticles to lipid bilayers. J Gen Physiol. 2011;137:217–223. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201010558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayburt TH. Sligar SG. Membrane protein assembly into Nanodiscs. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:1721–1727. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayley H, Cronin B, Heron A, Holden MA, Hwang WL, Syeda R, Thompson J. Wallace M. Droplet interface bilayers. Mol Biosyst. 2008;4:1191–1208. doi: 10.1039/b808893d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berneche S. Roux B. Energetics of ion conduction through the K+ channel. Nature. 2001;414:73–77. doi: 10.1038/35102067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezanilla F. Armstrong CM. Negative conductance caused by entry of sodium and cesium ions into the potassium channels of squid axons. J Gen Physiol. 1972;60:588–608. doi: 10.1085/jgp.60.5.588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blunck R, Cordero-Morales JF, Cuello LG, Perozo E. Bezanilla F. Detection of the opening of the bundle crossing in KcsA with fluorescence lifetime spectroscopy reveals the existence of two gates for ion conduction. J Gen Physiol. 2006;128:569–581. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200609638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall WA. Ion channel voltage sensors: structure, function, and pathophysiology. Neuron. 2010;67:915–928. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrapani S, Cordero-Morales JF. Perozo E. A quantitative description of KcsA gating II: single-channel currents. J Gen Physiol. 2007;130:479–496. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200709844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chill JH, Louis JM, Miller C. Bax A. NMR study of the tetrameric KcsA potassium channel in detergent micelles. Protein Sci. 2006;15:684–698. doi: 10.1110/ps.051954706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung SH, Allen TW, Hoyles M. Kuyucak S. Permeation of ions across the potassium channel: Brownian dynamics studies. Biophys J. 1999;77:2517–2533. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77087-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordero-Morales JF, Cuello LG. Perozo E. Voltage-dependent gating at the KcsA selectivity filter. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:319–322. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordero-Morales JF, Cuello LG, Zhao Y, Jogini V, Cortes DM, Roux B. Perozo E. b Molecular determinants of gating at the potassium-channel selectivity filter. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:311–318. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortes DM, Cuello LG. Perozo E. Molecular architecture of full-length KcsA: role of cytoplasmic domains in ion permeation and activation gating. J Gen Physiol. 2001;117:165–180. doi: 10.1085/jgp.117.2.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuello LG, Cortes DM, Jogini V, Sompornpisut A. Perozo E. a A molecular mechanism for proton-dependent gating in KcsA. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:1126–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuello LG, Jogini V, Cortes DM, Pan AC, Gagnon DG, Dalmas O, Cordero-Morales JF, Chakrapani S, Roux B. Perozo E. b Structural basis for the coupling between activation and inactivation gates in K+ channels. Nature. 2010;466:272–275. doi: 10.1038/nature09136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuello LG, Jogini V, Cortes DM. Perozo E. c Structural mechanism of C-type inactivation in K+ channels. Nature. 2010;466:203–208. doi: 10.1038/nature09153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dart C. Lipid microdomains and the regulation of ion channel function. J Physiol. 2010;588:3169–3178. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.191585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das U, Kumar J, Mayer ML. Plested AJR. Domain organization and function in GluK2 subtype kainate receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:8463–8468. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000838107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle DA, Morais-Cabral J, Pfuetzner RA, Kuo A, Gulbis JM, Cohen SL, Chait BT. MacKinnon R. The structure of the potassium channel: molecular basis of K+ conduction and selectivity. Science. 1998;280:69–77. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5360.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edidin M. Lipids on the frontier: a century of cell-membrane bilayers. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:414–418. doi: 10.1038/nrm1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egwolf B. Roux B. Ion selectivity of the KcsA channel: a perspective from multi-ion free energy landscapes. J Mol Biol. 2010;401:831–842. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenach C, Papanatsiou M, Hillert E-K. Blatt MR. Clustering of the K+ channel GORK of Arabidopsis parallels its gating by extracellular K+ Plant J. 2014;78:203–214. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler PW, Tai K. Sansom MSP. The selectivity of K+ ion channels: testing the hypotheses. Biophys J. 2008;95:5062–5072. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.132035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funakoshi K, Suzuki H. Takeuchi S. Lipid bilayer formation by contacting monolayers in a microfluidic device for membrane protein analysis. Anal Chem. 2006;78:8169–8174. doi: 10.1021/ac0613479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furutani Y, Shimizu H, Asai Y, Fukuda T, Oiki S. Kandori H. ATR-FTIR spectroscopy revealing the different vibrational modes of the selectivity filter interacting with K+ and Na+ in the open and collapsed conformations of the KcsA potassium channel. J Phys Chem Lett. 2012;3:3806–3810. doi: 10.1021/jz301721f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosman C, Zhou M. Auerbach A. Mapping the conformational wave of acetylcholine receptor channel gating. Nature. 2000;403:773–776. doi: 10.1038/35001586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen SB, Tao X. MacKinnon R. Structural basis of PIP2 activation of the classical inward rectifier K+ channel Kir2.2. Nature. 2011;477:495–498. doi: 10.1038/nature10370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedstrom KL. Rasband MN. Intrinsic and extrinsic determinants of ion channel localization in neurons. J Neurochem. 2006;98:1345–1352. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heginbotham L, Kolmakova-Partensky L. Miller C. Functional reconstitution of a prokaryotic K+ channel. J Gen Physiol. 1998;111:741–749. doi: 10.1085/jgp.111.6.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heginbotham L, LeMasurier M, Kolmakova-Partensky L. Miller C. Single Streptomyces lividans K+ channels: functional asymmetries and sidedness of proton activation. J Gen Physiol. 1999;114:551–560. doi: 10.1085/jgp.114.4.551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B. Ion Channels of Excitable Membranes, 3rd edn. Sunderland: Sinauer Associates Inc; 2001. , MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Hille B. Schwarz W. Potassium channels as multi-ion single-file pores. J Gen Physiol. 1978;72:409–442. doi: 10.1085/jgp.72.4.409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkin AL. Huxley AF. A quantitative description of membrane current and its application to conduction and excitation in nerve. J Physiol. 1952;117:500–544. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1952.sp004764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkin AL. Keynes RD. The potassium permeability of a giant nerve fibre. J Physiol. 1955;128:61–88. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1955.sp005291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]