Abstract

Micafungin is an effective antifungal agent useful for the therapy of invasive candidiasis. Candida albicans is the most common cause of invasive candidiasis; however, infections due to non-C. albicans species, such as Candida parapsilosis, are rising. Killing and postantifungal effects (PAFE) are important factors in both dose interval choice and infection outcome. The aim of this study was to determinate the micafungin PAFE against 7 C. albicans strains, 5 Candida dubliniensis, 2 Candida Africana, 3 C. parapsilosis, 2 Candida metapsilosis and 2 Candida orthopsilosis. For PAFE studies, cells were exposed to micafungin for 1 h at concentrations ranging from 0.12 to 8 μg/ml. Time-kill experiments (TK) were conducted at the same concentrations. Samples were removed at each time point (0-48 h) and viable counts determined. Micafungin (2 μg/ml) was fungicidal (≥ 3 log10 reduction) in TK against 5 out of 14 (36%) strains of C. albicans complex. In PAFE experiments, fungicidal endpoint was achieved against 2 out of 14 strains (14%). In TK against C. parapsilosis, 8 μg/ml of micafungin turned out to be fungicidal against 4 out 7 (57%) strains. Conversely, fungicidal endpoint was not achieved in PAFE studies. PAFE results for C. albicans complex (41.83 ± 2.18 h) differed from C. parapsilosis complex (8.07 ± 4.2 h) at the highest tested concentration of micafungin. In conclusion, micafungin showed significant differences in PAFE against C. albicans and C. parapsilosis complexes, being PAFE for the C. albicans complex longer than for the C. parapsilosis complex.

Introduction

Invasive candidiasis is a leading cause of mortality worldwide, being Candida albicans the predominant cause of candidemia and invasive candidiasis. However, candidiasis due to non-C. albicans species, such as Candida parapsilosis, Candida glabrata, Candida tropicalis, Candida krusei, Candida lusitaniae, Candida guilliermondii, are increasing. Some of these species exhibit resistance or reduced susceptibility to fluconazole and other triazoles, echinocandins or amphotericin B. C. parapsilosis is associated to infections in neonates and young adults, usually related to the presence of central venous catheter and hyperalimentation [1]. C. parapsilosis is usually susceptible to most antifungal agents, but there are reports of infections caused by isolates with decreased susceptibility to azoles and echinocandins [2]. Molecular identification methods have unveiled new cryptic species within C. albicans and C. parapsilosis species complexes, such as Candida dubliniensis and Candida africana within the C. albicans complex or Candida metapsilosis and Candida orthopsilosis within C. parapsilosis complex. These cryptic species show differences in antifungal susceptibility and virulence, being their epidemiology and antifungal susceptibility a matter of increased interest [3–5].

Micafungin inhibits the synthesis of 1,3-β-D-glucan, an essential molecule of many pathogenic fungi wall architecture, and exhibits an excellent activity against a great number of Candida species many resistant to azoles [6]. Thus, micafungin is a very useful drug for the first line therapy of invasive candidiasis [7].

Postantifungal effect (PAFE) allows for sustained killing of fungus when it is exposed briefly to an antifungal, being a concentration-dependent process [8]. The existence of PAFE depends on both the fungal species and the class of the antifungal drug. Whereas antifungal drugs that have long PAFE may be given less frequently, the antifungal drugs with short PAFE may require a frequent administration [9]. For this reason, the PAFE may have a main clinical relevance in the design of dosing regimens for antifungal agents, such as micafungin. The PAFE of micafungin against various species of Candida has been evaluated in a few studies [10–13]. The aim of this study was to determinate the PAFE of micafungin against the species inside of the C albicans and C parapsilosis complexes.

Materials and Methods

Microorganisms

A total of 21 Candida strains were selected for testing: 14 strains from the C. albicans complex (C. albicans: 5 blood isolates [UPV/EHU 99–101, 99–102, 99–103, 99–104 and 99–105] and 2 reference strains [NCPF 3153 and 3156]; C. dubliniensis: 4 blood isolates [UPV/EHU 00–131, 00–132, 00–133, 00–135] and 1 reference strain [NCPF 3949]; C. africana: 1 vaginal isolate [UPV/EHU 97–135] and 1 reference strain [ATCC 2669]) and 7 strains from the C. parapsilosis complex (C. parapsilosis sensu stricto: 1 blood isolate [UPV/EHU 09–378] and 2 reference strains [ATCC 22019 and ATCC 90018]; C. metapsilosis: 1 blood isolate [UPV/EHU 07–045] and 1 reference strain [ATCC 96143]; C. orthopsilosis: 1 blood isolate [UPV/EHU 07–035] and 1 reference strain [ATCC 96139]). Fungal isolates were obtained from the culture collection of the Laboratorio de Micología Médica, Universidad del País Vasco/Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea (UPV/EHU), Bilbao, Spain. Isolates were identified by their metabolic properties using the ATB ID 32C method (bioMérieux, Marcy l’Étoile, France) and by molecular methods, as previously described [14,15].

Antifungal Agents

Micafungin (Astellas Pharma, Madrid, Spain) was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), to obtain a stock solution of 5120 μg/ml. The dilutions were prepared in RPMI 1640 medium with L-glutamine, 0.2% glucose and without NaHCO2 buffered to pH 7 with 0.165 M morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (MOPS) (Sigma-Aldrich, Madrid, Spain). Stock solutions were stored at – 80°C until use.

In Vitro Susceptibility Testing

MICs, defined as minimum concentrations that produce ≥50 growth reduction, were determined following M27-A3 and M27-A3 S4 documents [16,17]. All MICs were measured in RPMI 1640 medium buffered to pH 7.0 with 0.165 M MOPS and results were read after 24 h of incubation.

Time-Kill Procedures

Time-kill studies (TK) were performed as previously described [18–20]. Strains were subcultured on Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA) plates prior to testing. Cell suspensions were prepared in sterile water by picking 3 to 5 colonies from a 24 h culture and the resulting suspension was prepared at 1 McFarland (≈ 106 CFU/ml). One milliliter of the cell suspension was added to vials containing 9 ml of RPMI. TK were carried out on microtiter plates for the BioScreen C computer-controlled microbiological incubator (BioScreen C MBR, LabSystems, Helsinki, Finland) in RPMI (final volume 200 μl) by using an inoculum of 1–5 x 105 CFU/ml. On the basis of MICs, micafungin concentrations tested were 0.12, 0.5 and 2 μg/ml for the C. albicans complex and 0.25, 2 and 8 μg/ml for the C. parapsilosis complex. These micafungin concentrations are achieved in serum after standard therapeutic doses [21]. Inoculated plates were incubated 48 h at 36 ± 1°C (30 ± 1°C for C. africana). At predetermined time points (0, 2, 4, 6, 24, and 48 h), 10 μl (0–6 h) or 6 μl (24–48 h) were collected from each culture well (control and test solution wells), serially diluted in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and aliquots plated onto SDA. The lower limit of accurate and reproducible detectable colony forming units (CFU) counts was 200 CFU/ml. When the CFUs were expected to be less than 200 per milliliter, samples of 5 μl were taken directly from the test solution and plated. After incubation of the plates at 36 ± 1°C for 48 h (30 ± 1°C for C. africana), Candida colonies were counted. Each experiment was performed twice for each isolate. Plots of averaged colony counts (log10 CFU/ml) versus time were constructed and compared against a growth control (in the absence of drug). Also the antifungal carryover effect was determined as formerly reported [22].

PAFE

PAFE studies were performed as described previously with slight differences [23]. Standard 1 McFarland turbidity cell suspensions were prepared in sterile distilled water, from which 1 ml was added to 9 ml of RPMI. Micafungin concentrations were the same as described for the TK. Following an incubation of 1 h, micafungin was removed by a process of 3 cycles of repeated centrifugations (2000 rpm, 10 min) and washed with PBS. After the final centrifugation, the fungal pellet was suspended in 600 μl of RPMI. All samples were incubated on microtiter plates for the BioScreen C at 36 ± 1°C, with a final volume of 200 μl. At the same predetermined time points described for the TK, samples were serially diluted in PBS and inoculated onto a SDA plate for CFU counting. When the colony counts were expected to be less than 200 CFU/mL, samples of 5 μl were taken directly from the test solution and plated. After incubation of the plates at 36 ± 1°C for 48 h, Candida colonies were counted. The lower limit of accurate and reproducible detectable colony counts was 200 CFU/ml. PAFE was calculated for each isolate as the difference in time required for control (in the absence of drug) and treated isolates to grow 1 log10 following drug removal. PAFE was also determined using the following equation: PAFE = T-C, where T = time required for counts in treated cultures to increase by 1 log10 unit above that seen following drug removal and C = time required for counts in control to increase by 1 log10 unit above that following the last washing.

PAFE and TK data comparison

Fungicidal activity was described as a ≥ 3 log 10 (99.9%) reduction, and fungistatic activity was defined as a < 99.9% reduction in CFU from the starting inoculum size [24]. Plots of averaged colony counts (log10 CFU per milliliter) versus time were constructed and compared against a growth control. The ratios of the log killing during PAFE experiments to the log killing during time kill experiments were calculated. Time-kill and PAFE experiments were performed simultaneously.

Statistical Analysis

Analysis of variance was performed to determine significant differences in PAFE (in hours) among species and concentrations, using GraphPad Prism 5.01 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA; USA). A p value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

No antifungal carryover effect was detected in TK. Micafungin MICs for isolates from C. albicans and C. parapsilosis complexes are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Micafungin MICs for C. albicans and C. parapsilosis complex strains.

| Strain | MIC (μg/ml) |

|---|---|

| C. albicans NCPF 3153 | 0.25 |

| C. albicans NCPF 3156 | 0.12 |

| C. albicans UPV/EHU 99–101 | 0.25 |

| C. albicans UPV/EHU 99–102 | 0.25 |

| C. albicans UPV/EHU 99–103 | 0.12 |

| C. albicans UPV/EHU 99–104 | 0.25 |

| C. albicans UPV/EHU 99–105 | 0.12 |

| C. dubliniensis NCPF 3949 | 0.25 |

| C. dubliniensis UPV/EHU 00–131 | 0.25 |

| C. dubliniensis UPV/EHU 00–132 | 0.12 |

| C. dubliniensis UPV/EHU 00–133 | 0.12 |

| C. dubliniensis UPV/EHU 00–135 | 0.06 |

| C. africana UPV/EHU 97–135 | 0.12 |

| C. africana ATCC 2669 | 0.06 |

| C. parapsilosis ATCC 22019 | 2 |

| C. parapsilosis ATCC 90018 | 1 |

| C. parapsilosis UPV/EHU 09–378 | 2 |

| C. metapsilosis ATCC 96143 | 2 |

| C. metapsilosis UPV/EHU 07–045 | 2 |

| C. orthopsilosis ATCC 96139 | 1 |

| C. orthopsilosis UPV/EHU 07–035 | 1 |

The results of TK and PAFE experiments for C. albicans, C. dubliniensis and C. africana are shown in Table 2. Micafungin showed prolonged PAFE (≥ 37.5 h) against all strains of C. albicans complex with 2 μg/ml (p < 0.0001). With one of these strains (UPV/EHU 99–101) PAFE was > 43 h with 0.5 μg/ml. During TK tests, micafungin was fungicidal against 5 out of 14 (36%) strains of C. albicans complex (C. albicans NCPF 3156, UPV/EHU 99–101, 99–102, 99–105 and C. dubliniensis UPV/EHU 00–135). The extent of micafungin log-killing in TK ranged from 0.08 to 5.22 log at 2 μg/ml. After micafungin removal in PAFE experiments, fungicidal endpoint was achieved against 2 out of 14 (14%) strains of C. albicans complex (C. albicans UPV/EHU 99–102 and C. dubliniensis UPV/EHU 00–135). Moreover, the extent of killing during PAFE experiments ranged from 0.28 to 4.67 log with 2 μg/ml.

Table 2. PAFE results for C. albicans complex.

| Isolate | Micafungin (μg/ml) | Killing (log) | PAFE/TK 1 | PAFE (h) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TK | PAFE | ||||

| C. albicans NCPF 3153 | 0.12 | 0.21 | NA 2 | 0 | |

| 0.5 | 0.38 | NA | 0 | ||

| 2 | 0.08 | 0.28 | 100 | > 44 | |

| C. albicans NCPF 3156 | 0.12 | NA | NA | 0 | |

| 0.5 | 1.49 | NA | 0 | ||

| 2 | 5.07 | 1.55 | 0 | > 42 | |

| C. albicans UPV/EHU 99–101 | 0.12 | 2.25 | 0.56 | 2.04 | 0 |

| 0.5 | 2.85 | 1.58 | 5.37 | > 43 | |

| 2 | 5.1 | 1.81 | 0 | > 43 | |

| C. albicans UPV/EHU 99–102 | 0.12 | 1.54 | 0.65 | 12.89 | 2.4 |

| 0.5 | 2.26 | 0.42 | 1.44 | 0 | |

| 2 | 5 | 4.67 | 46.77 | > 39.46 | |

| C. albicans UPV/EHU 99–103 | 0.12 | NA | NA | 0 | |

| 0.5 | NA | NA | 0 | ||

| 2 | 1.49 | 0.52 | 10.68 | > 44 | |

| C. albicans UPV/EHU 99–104 | 0.12 | NA | 0.27 | 0 | |

| 0.5 | NA | 0.02 | 0 | ||

| 2 | 0.46 | 0.63 | 100 | > 42 | |

| C. albicans UPV/EHU 99–105 | 0.12 | 0.63 | 0.62 | 98 | 0 |

| 0.5 | 2.62 | 0.52 | 0.8 | 0 | |

| 2 | 5.22 | 0.55 | 0 | > 42 | |

| C. dubliniensis NCPF 3949 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 82.56 | 0 |

| 0.5 | NA | 0.11 | 0 | ||

| 2 | 0.5 | 0.21 | 51.27 | > 42 | |

| C. dubliniensis UPV/EHU 00–131 | 0.12 | NA | NA | 0 | |

| 0.5 | NA | NA | 20 | ||

| 2 | 0.43 | NA | 44 | ||

| C. dubliniensis UPV/EHU 00–132 | 0.12 | NA | NA | 0 | |

| 0.5 | NA | NA | 0 | ||

| 2 | 0.51 | NA | > 44 | ||

| C. dubliniensis UPV/EHU 00–133 | 0.12 | NA | NA | 0 | |

| 0.5 | 0.02 | NA | 0 | ||

| 2 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 50.1 | 42 | |

| C. dubliniensis UPV/EHU 00–135 | 0.12 | 0.86 | NA | 0 | |

| 0.5 | 2.22 | 0.24 | 1.05 | 0 | |

| 2 | 5 | 4.67 | 46.77 | > 42 | |

| C. africana ATCC 2669 | 0.12 | 0.1 | 0.12 | 100 | 0 |

| 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.12 | 100 | 0 | |

| 2 | 0.19 | 0.28 | 100 | > 37.7 | |

| C. africana UPV/EHU 97–135 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.01 | 77.27 | 0 |

| 0.5 | 0.08 | 0.24 | 100 | 3 | |

| 2 | 0.46 | 0.58 | 100 | > 37.5 | |

1 Ratio of the log killing during PAFE experiments to the log killing during time-kill experiments.

2 NA, not applicable (without any reduction in colony counts compared with the starting inoculum).

The mean value of PAFE/TK ratio was 43.25 (with 2 μg/ml) for C. albicans complex. Against 4 out of 14 strains (29%), the PAFE/TK ratio of micafungin at the highest tested concentration was 100, indicating that 1-hour exposure to micafungin accounted for up to 100% of the overall killing observed during TK. Additionally, a ratio of 100 at concentrations ≤ 2 μg/m was observed for C. africana (Table 2).

Table 3 summarizes the results of time-kill and PAFE experiments for C. parapsilosis, C. metapsilosis and C. orthopsilosis at each micafungin concentration. During TK, micafungin at 8 μg/ml caused significant reductions from the starting inoculum of each strain, with a killing activity that ranged from 1.67 to 5.43 log. However, during PAFE experiments, 1-hour exposure of the strains to micafungin did not cause important reductions in colony counts. PAFE of micafungin ranged 3.8 to 15.7 h (with 8 μg/ml); the longest PAFE (15.7 h) was reached against C. parapsilosis UPV/EHU 09–378. Micafungin at 8 μg/ml demonstrated fungicidal activity in TK against 4 out 7 (57%) strains from C. parapsilosis complex (C. parapsilosis UPV/EHU 09–378, C. metapsilosis ATCC 96143, UPV/EHU 07–045 and C. orthopsilosis ATCC 96139). However, after micafungin removal in PAFE experiments, it was not reached fungicidal endpoint against any of the tested strains. The lack of similarity between TK and PAFE data was also detected in the mean PAFE/TK ratio of 0.49, with 8 μg/ml, suggesting that 1-hour exposure to micafungin accounted for only a 2% of the overall killing observed during time-kill experiments; only one strain, C. parapsilosis UPV/EHU 09–378, showed a ratio of 100, with 2 μg/ml (Table 3).

Table 3. PAFE results for C. parapsilosis complex.

| Isolate | Micafungin (μg/ml) | Killing (log) | PAFE/TK 1 | PAFE (h) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TK | PAFE | ||||

| C. parapsilosis ATCC 22019 | 0.25 | NA 2 | NA | 0 | |

| 2 | NA | NA | 0 | ||

| 8 | 1.67 | 0.08 | 2.56 | 6 | |

| C. parapsilosis ATCC 90018 | 0.25 | 0.16 | NA | 0 | |

| 2 | 0.12 | NA | 0 | ||

| 8 | 2.12 | 0.07 | 0.89 | 5.3 | |

| C. parapsilosis UPV/EHU 09–378 | 0.25 | NA | NA | 0 | |

| 2 | 0.07 | 0.31 | 100 | 0 | |

| 8 | 5.27 | 0.22 | 0 | 15.7 | |

| C. metapsilosis ATCC 96143 | 0.25 | 0.02 | NA | 0 | |

| 2 | NA | NA | 0 | ||

| 8 | 5.42 | NA | 5.4 | ||

| C. metapsilosis UPV/EHU 07–045 | 0.25 | NA | 0.03 | 0 | |

| 2 | NA | NA | 0 | ||

| 8 | 5.24 | 0.11 | 0 | 9.3 | |

| C. orthopsilosis ATCC 96139 | 0.25 | NA | NA | 2 | |

| 2 | NA | NA | 2 | ||

| 8 | 5.43 | NA | 11 | ||

| C. orthopsilosis UPV/EHU 07–035 | 0.25 | NA | NA | 0 | |

| 2 | NA | NA | 0 | ||

| 8 | 1.91 | NA | 3.8 | ||

1 Ratio of the log killing during PAFE experiments to the log killing during TK experiments.

2 NA, not applicable (without any reduction in colony counts compared with the starting inoculum).

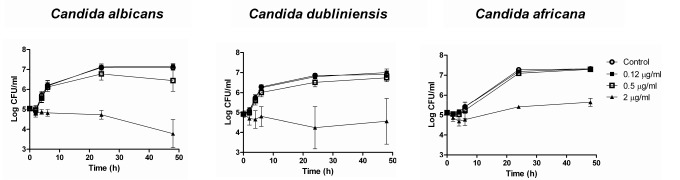

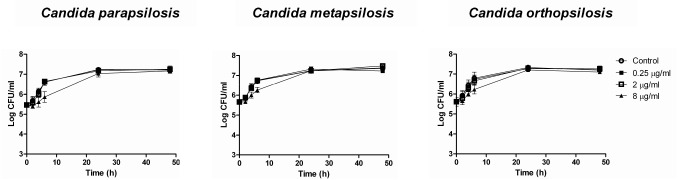

PAFE results for C. albicans complex (41.83 ± 2.18 h) differed from C. parapsilosis complex (8.07 ± 4.2 h) with the highest concentration of micafungin tested (p < 0.0001). This difference is also evident when comparing C. albicans and C. parapsilosis complexes curves from PAFE assays (Figs 1 and 2). Micafungin caused lethality (with 2 μg/ml) against C. albicans complex (Fig 1) that persisted during the 48 h testing period; however, in Fig 2 similar log (CFU/ml) slopes between micafungin and control can be observed.

Fig 1. Mean TK curves from PAFE assays against 7 C. albicans, 5 C. dubliniensis and 2 C. africana strains.

Each data point represents the mean result ± standard deviation (error bars). Open circles (○): control; filled squares (■): 0.12 μg/ml; open squares (□): 0.5 μg/ml; filled triangles (▲): 2 μg/ml.

Fig 2. Mean TK curves from PAFE assays against 3 C parapsilosis sensu stricto, 2 C. metapsilosis and 2 C. orthopsilosis strains.

Each data point represents the mean result ± standard deviation (error bars). Open circles (○): control; filled squares (■): 0.25 μg/ml; open squares (□): 2 μg/ml; filled triangles (▲): 8 μg/ml.

Discussion

TK and PAFE experiments of micafungin against Candida have usually included a low number of isolates [10–13]. This is the first study that has evaluated PAFE of micafungin against C. dubliniensis, C. africana, C. metapsilosis and C. orthopsilosis. C. dubliniensis and C. africana are cryptic species from C. albicans. Similarly C. metapsilosis and C. orthopsilosis are cryptic species from C. parapsilosis. These species have different in vitro susceptibility to antifungal agents [3,4,25]. Additionally, PAFE is an important factor in both dose interval choice and outcome.

MICs for C. albicans and C. parapsilosis complexes were consistent with other studies of micafungin activity in vitro against these species [26]. Moreover, we also found that micafungin reached fungicidal endpoint against 4 out of 7 strains of C. albicans (with 2 μg/ml) and against 1 out of 3 strains of C. parapsilosis (with 8 μg/ml), during TK experiments. This fungicidal activity has also been reported by Smith et al. [11] against both species.

After micafungin removal, Nguyen et al. [11] observed fungicidal activity against 1 out 4 strains of C. albicans, 1 out of 3 strains of C. parapsilosis, 2 out of 3 strains of C. glabrata and 1 out of 2 strains of C. krusei (with range concentrations 0.12 to 8 μg/ml). Similarly, in the current study, the fungicidal endpoint was reached against 1 out of 7 strains of C. albicans at the highest tested concentration (2 μg/ml). Nevertheless, after micafungin removal, no fungicidal endpoint was achieved against C. parapsilosis [11].

Micafungin (8 μg/ml) displayed PAFE against C. parapsilosis complex that ranged from 3.8 to 15.7 h, being the longest PAFE against C. parapsilosis UPV/EHU 09–378. These results are similar to previous reported by Smith et al. [10] Other authors have demonstrated that a short exposure (1 h) of C. albicans to low concentrations (0.125 to 1 μg/ml) of micafungin, resulted in a PAFE of 5 h [12]. Our current findings demonstrate that micafungin produced a longer PAFE against C. albicans than those previously reported, being the PAFE > 40 h with 2 μg/ml against all strains. Manavathu et al. [12] compared PAFE of different antifungal drugs against C. albicans and Aspergillus fumigatus and stated that antifungal drugs with fungicidal activity tend to possess longer PAFE than fungistatic ones. On the other hand, Ernst et al. [23] observed that fluconazole displayed no measurable PAFE against none of the studied microorganisms, while echinocandins displayed prolonged PAFE of greater than 12 h against C. albicans with concentrations ≤ 0.12 μg/ml. Our current findings differed from these ones, as no measurable PAFE was detected against C. albicans at such low micafungin concentrations (0.12 μg/ml) except for one strain, UPV/EHU 99–102. In order to investigate the effect of exposure time on the observed PAFE, Ernst et al. studied the PAFE of caspofungin and amphotericin B after 0.25, 0.5 and 1 h exposure times concluding that PAFE was not affected by the exposure time: 0.25 h exposure produced the same PAFE as 1 h exposure [23]. Similarly, Moriyama et al. reported that the maximum PAFE against Candida occurred with caspofungin exposures of 5 or 15 minutes [8]. As performed in other PAFE experiments, in which PAFE was determined after 1 h exposure [10–12], we have studied the PAFE of micafungin after 1 h exposure.

In another study, Ernst et al. also found PAFE with micafungin against C. albicans, C. krusei, C. tropicalis and C. glabrata, [13]. Micafungin and anidulafungin had greater activity than caspofungin, and none of the echinocandins depicted fungicidal activity against C. parapsilosis. However, the three echinocandins reached the fungicidal endpoint against C. orthopsilosis and C. metapsilosis [19]. Results from our study differ from these reports as we have found that micafungin was fungicidal only against one strain of C. parapsilosis.

Previous studies have evaluated PAFEs of anidulafungin and caspofungin against Candida, and have shown that anidulafungin achieved fungicidal activity against C. parapsilosis, but not against C. albicans, and caspofungin did not show fungicidal activity [27,28].

Our PAFE studies demonstrated that micafungin produced concentration-dependent, strain-dependent and complex-dependent antifungal activity following drug removal. PAFE was measurable at the higher concentration, and this effect was enhanced by increasing the concentration of the antifungal drug, with highest concentration resulting in the longest PAFE in each case. One of the most notable findings of this study was the PAFE of micafungin against C. albicans complex. Micafungin exerted prolonged PAFE against C. albicans complex, and 1 h exposure to micafungin accounted for up to 100% of the overall killing observed during TK experiments in 29% of the studied strains. The results are consistent with a rapid onset of anticandidal activity of micafungin, which might be explained by a rapid association with its target (1,3-β-D-glucan synthase). Alternatively, it has also been suggested that the drug, as a large lipopeptide with a fatty acid side chain, could rapidly intercalate with the phospholipid bilayer of the Candida cell membrane and subsequently access its target over time [29].

Recently, Ellepola et al. studied the PAFE of nystatin, amphotericin B, ketoconazole and fluconazole against oral C. dubliniensis isolates, concluding that nystatin, amphotericin B and ketoconazole produced a detectable PAFE, whereas fluconazole did no display any measurable PAFE [30,31]. This finding is consistent with previously published by Ernst et al. [23]. Kovács et al. reported caspofungin PAFE in 2 C. albicans strains [32].

In conclusion, micafungin showed significant differences in PAFE against C. albicans and C. parapsilosis complexes, being PAFE of micafungin for the C. albicans complex longer than against the C. parapsilosis complex. These differences in the PAFE could be explained by the distinct microorganism growth characteristics, the antifungal drug binding affinity to the targets, or differences in the amount of β-glucan in the fungal cell wall. These PAFE differences for C. parapsilosis and other Candida species might have important therapeutic implications. The current data could be useful in optimizing dosing regimens for micafungin against C. albicans, C. dubliniensis, C. africana, C. parapsilosis, C. metapsilosis and C. orthopsilosis. However, further animal studies and human clinical trials are needed to explore their potential clinical usefulness and applications.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by Consejería de Educación, Universidades e Investigación (GIC12 210-IT-696-13), the Departamento de Industria, Comercio y Turismo (S-PR12UN002, S-PE13UN025) of Gobierno Vasco-Eusko Jaurlaritza, and UPV/EHU (UFI 11/25). Elena Eraso and Guillermo Quindós have received grant support from Consejería de Educación, Universidades e Investigación (GIC12 210-IT-696-13) and Departamento de Industria, Comercio y Turismo (S-PR12UN002, S-PE13UN121) of Gobierno Vasco-Eusko Jaurlaritza, Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria (FIS PI11/00203), and UPV/EHU (UFI 11/25).

References

- 1. Quindós G. Epidemiology of candidaemia and invasive candidiasis. A changing face. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2014;31: 42–48. 10.1016/j.riam.2013.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Moudgal V, Little T, Boikov D, Vazquez JA. Multiechinocandin- and multiazole-resistant Candida parapsilosis isolates serially obtained during therapy for prosthetic valve endocarditis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49: 767–769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pfaller MA, Boyken L, Hollis RJ, Kroeger J, Messer SA, Tendolkar S, et al. In vitro susceptibility of invasive isolates of Candida spp. to anidulafungin, caspofungin, and micafungin: six years of global surveillance. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46: 150–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tavanti A, Davidson AD, Gow NA, Maiden MC, Odds FC. Candida orthopsilosis and Candida metapsilosis spp. nov. to replace Candida parapsilosis groups II and III. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43: 284–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lockhart SR, Messer SA, Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ. Geographic distribution and antifungal susceptibility of the newly described species Candida orthopsilosis and Candida metapsilosis in comparison to the closely related species Candida parapsilosis . J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46: 2659–2664. 10.1128/JCM.00803-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Emri T, Majoros L, Toth V, Pocsi I. Echinocandins: production and applications. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;97: 3267–3284. 10.1007/s00253-013-4761-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Quindós G, Eraso E, Javier Carrillo-Munoz A, Cantón E, Pemán J. In vitro antifungal activity of micafungin. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2009;26: 35–41. 10.1016/S1130-1406(09)70006-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moriyama B, Henning SA, Penzak SR, Walsh TJ. The postantifungal and paradoxical effects of echinocandins against Candida spp. Future Microbiol. 2012;7: 565–569. 10.2217/fmb.12.31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Oz Y, Kiremitci A, Dag I, Metintas S, Kiraz N. Postantifungal effect of the combination of caspofungin with voriconazole and amphotericin B against clinical Candida krusei isolates. Med Mycol. 2013;51: 60–65. 10.3109/13693786.2012.697198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Smith RP, Baltch A, Bopp LH, Ritz WJ, Michelsen PP. Post-antifungal effects and time-kill studies of anidulafungin, caspofungin, and micafungin against Candida glabrata and Candida parapsilosis . Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;71: 131–138. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2011.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nguyen KT, Ta P, Hoang BT, Cheng S, Hao B, Nguyen MH, et al. Characterising the post-antifungal effects of micafungin against Candida albicans, Candida glabrata, Candida parapsilosis and Candida krusei isolates. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2010;35: 80–84. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Manavathu EK, Ramesh MS, Baskaran I, Ganesan LT, Chandrasekar PH. A comparative study of the post-antifungal effect (PAFE) of amphotericin B, triazoles and echinocandins on Aspergillus fumigatus and Candida albicans . J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004;53: 386–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ernst EJ, Roling EE, Petzold CR, Keele DJ, Klepser ME. In vitro activity of micafungin (FK-463) against Candida spp.: microdilution, time-kill, and postantifungal-effect studies. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46: 3846–3853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Miranda-Zapico I, Eraso E, Hernández-Almaraz JL, López-Soria LM, Carrillo-Muñoz AJ, Hernández-Molina JM, et al. Prevalence and antifungal susceptibility patterns of new cryptic species inside the species complexes Candida parapsilosis and Candida glabrata among blood isolates from a Spanish tertiary hospital. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66: 2315–2322. 10.1093/jac/dkr298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pemán J, Cantón E, Quindós G, Eraso E, Alcoba J, Guinea J, et al. Epidemiology, species distribution and in vitro antifungal susceptibility of fungaemia in a Spanish multicentre prospective survey. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67: 1181–1187. 10.1093/jac/dks019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. M27-A3. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeast Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute, Wayne, PA: 2008;. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. M27-A3 S4. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeast Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute, Wayne, PA: 2012;. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gil-Alonso S, Jauregizar N, Cantón E, Eraso E, Quindós G. Comparison of the in vitro activity of echinocandins against Candida albicans, Candida dubliniensis, and Candida africana by time-kill curves. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2015; 82: 57–61. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2015.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cantón E, Espinel-Ingroff A, Pemán J, del Castillo L. In vitro fungicidal activities of echinocandins against Candida metapsilosis, C. orthopsilosis, and C. parapsilosis evaluated by time-kill studies. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54: 2194–2197. 10.1128/AAC.01538-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cantón E, Pemán J, Hervas D, Espinel-Ingroff A. Examination of the in vitro fungicidal activity of echinocandins against Candida lusitaniae by time-killing methods. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68: 864–868. 10.1093/jac/dks489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Catalán González M, Montejo Gonzalez JC. Anidulafungin: a new therapeutic approach in antifungal therapy. Pharmacology of anidulafungin. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2008;25: 92–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cantón E, Pemán J, Gobernado M, Viudes A, Espinel-Ingroff A. Patterns of amphotericin B killing kinetics against seven Candida species. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48: 2477–2482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ernst EJ, Klepser ME, Pfaller MA. Postantifungal effects of echinocandin, azole, and polyene antifungal agents against Candida albicans and Cryptococcus neoformans . Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44: 1108–1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lewis RE, Diekema DJ, Messer SA, Pfaller MA, Klepser ME. Comparison of Etest, chequerboard dilution and time-kill studies for the detection of synergy or antagonism between antifungal agents tested against Candida species. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2002;49: 345–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lockhart SR, Messer SA, Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ. Geographic distribution and antifungal susceptibility of the newly described species Candida orthopsilosis and Candida metapsilosis in comparison to the closely related species Candida parapsilosis . J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46: 2659–2664. 10.1128/JCM.00803-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pfaller MA, Espinel-Ingroff A, Bustamante B, Cantón E, Diekema DJ, Fothergill A, et al. Multicenter study of anidulafungin and micafungin MIC distributions and epidemiological cutoff values for eight Candida species and the CLSI M27-A3 broth microdilution method. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58: 916–922. 10.1128/AAC.02020-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nguyen KT, Ta P, Hoang BT, Cheng S, Hao B, Nguyen MH, et al. Anidulafungin is fungicidal and exerts a variety of postantifungal effects against Candida albicans, C. glabrata, C. parapsilosis, and C. krusei isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53: 3347–3352. 10.1128/AAC.01480-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Clancy CJ, Huang H, Cheng S, Derendorf H, Nguyen MH. Characterizing the effects of caspofungin on Candida albicans, Candida parapsilosis, and Candida glabrata isolates by simultaneous time-kill and postantifungal-effect experiments. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50: 2569–2572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Denning DW. Echinocandin antifungal drugs. Lancet. 2003;362: 1142–1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ellepola AN, Joseph BK, Chandy R, Khan ZU. The postantifungal effect of nystatin and its impact on adhesion attributes of oral Candida dubliniensis isolates. Mycoses. 2014;57: 56–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ellepola AN, Chandy R, Khan ZU. Post-antifungal effect and adhesion to buccal epithelial cells of oral Candida dubliniensis isolates subsequent to limited exposure to amphotericin B, ketoconazole and fluconazole. J Investig Clin Dent. 2014; 10.1111/jicd.12095 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32. Kovacs R, Gesztelyi R, Perlin DS, Kardos G, Doman M, Berenyi R, et al. Killing rates for caspofungin against Candida albicans after brief and continuous caspofungin exposure in the presence and absence of serum. Mycopathologia. 2014;178: 197–206. 10.1007/s11046-014-9799-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper.