Abstract

Patient: Female, 34

Final Diagnosis: Ocular syphilis

Symptoms: Painful unilateral vision loss

Medication: Benzylpenicillin

Clinical Procedure: Lumbar puncture

Specialty: Infectious Diseases • Ophthalmology

Objective:

Rare disease

Background:

Syphilis is often known as the “Great Imitator”. The differential diagnosis of posterior uveitis is broad with ocular syphilis being particularly challenging to diagnose as it presents similarly to other ocular conditions such as acute retinal necrosis.

Case Report:

A 34-year-old woman with multiple sexual partners over the past few years presented with painful and progressively worsening unilateral vision loss for 2 weeks. Several months prior, she had reported non-specific symptoms of headache and diffuse skin rash. Despite treatment with oral acyclovir for 3 weeks, her vision progressively declined, and she was referred to the university ophthalmology clinic for further evaluation. On examination, there was concern for acute retinal necrosis and she was empirically treated with parenteral acyclovir while awaiting further infectious disease study results. Workup ultimately revealed ocular syphilis, and neurosyphilis was additionally confirmed with cerebrospinal fluid studies. Treatment with intravenous penicillin was promptly initiated with complete visual recovery.

Conclusions:

Ocular syphilis varies widely in presentation and should be considered in all patients with posterior uveitis, especially with a history of headache and skin rashes. However, given that acute retinal necrosis is a more common cause of posterior uveitis and can rapidly result in permanent vision loss, it should be empirically treated whenever it is suspected while simultaneous workup is conducted to evaluate for alternative diagnoses.

MeSH Keywords: Eye Infections, Bacterial; Neurosyphilis; Retinal Necrosis Syndrome, Acute; Syphilis; Uveitis, Posterior

Background

The differential diagnosis of posterior uveitis is broad and includes ocular syphilis, which poses a significant diagnostic challenge given its various presentations that mimic many other ocular conditions [1]. Fortunately, prognosis for ocular syphilis is generally favorable, with the potential for complete visual recovery with appropriate treatment [2–4]. However, severe ocular syphilis mimics acute retinal necrosis, which, unlike ocular syphilis, carries a poor prognosis as its clinical course is fulminant and can result in rapid permanent vision loss. Hence, whenever acute retinal necrosis is suspected, it must be empirically treated while workup for other causes of posterior uveitis is conducted [5–8]. We report a case of a patient who presented with fulminant posterior uveitis, initially managed with empiric treatment for acute retinal necrosis to protect against vision loss, whose workup ultimately revealed ocular syphilis and neurosyphilis.

Case Report

A 34-year-old white female initially presented to her ophthalmologist with conjunctival injection and blurry vision. A recent history of herpes labialis led to a presumptive diagnosis of ocular herpes simplex virus infection. Following initial improvement with oral acyclovir, her vision declined over the next 2 weeks, with progressive development of left eye pain and vision loss. She endorsed increased lacrimation and presence of floaters. She denied purulent discharge or blind spots. Her right eye was asymptomatic. Given these symptoms, she was referred to the university ophthalmology clinic and immediately referred to the emergency department.

Her sexual history was significant for 15 heterosexual partners in the last 5 years with inconsistent barrier protection use. She additionally revealed a recent history of new-onset headaches, and the development of a diffuse non-pruritic rash that spontaneously resolved. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), gonorrhea, and chlamydia studies obtained 6 months prior were negative. She denied any prior history of syphilis or genital ulcers.

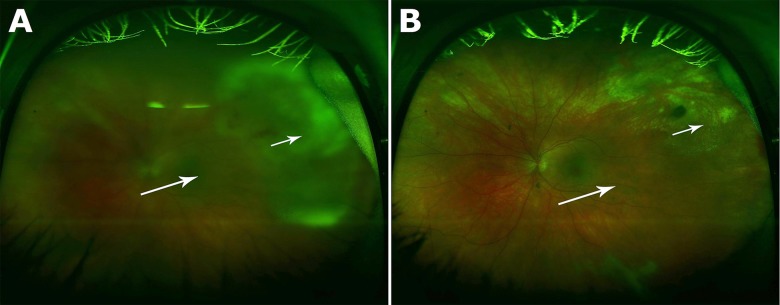

Initial left eye visual acuity obtained in the emergency department was 20/50. Fundoscopy revealed severe posterior uveitis with dense vitreous inflammation, and white focal retinal infiltrates at the superotemporal retina (Figure 1A). She had normal visual acuity in her right eye, and fundoscopy was grossly normal.

Figure 1.

(A) Wide field color fundus photography showing the patient’s left eye at initial presentation with dense vitreous inflammation (large arrow) and focal retinal infiltrates in the superotemporal quadrant (small arrow). (B) The patient’s left eye at 3-month follow-up visit with resolution of vitreous inflammation (large arrow) and isolated chorioretinal atrophy in the supertemporal quadrant (small arrow).

Given the concern for acute retinal necrosis, she was admitted to the hospital and treated empirically with intravenous acyclovir and intravitreal ganciclovir. Simultaneous workup was conducted to rule out other etiologies. Prednisolone eye drops were initiated due to significant ocular inflammation, but oral steroids were withheld until bacterial and fungal infections could be excluded. On hospital day 4, 180-degree peripheral necrosis was noted without evidence of retinal detachment. Despite aggressive antiviral therapy, her left eye visual acuity declined to 20/800 by hospital day 6. Serological test results for herpes simplex virus (HSV), toxoplasmosis, sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, and HIV were negative. Vitreal polymerase chain reaction (PCR) studies for HSV, varicella zoster virus (VZV), and cytomegalovirus (CMV) were also negative. Serum rapid plasma reagin (RPR) returned positive at a titer of 1:128, followed by a confirmatory positive serum fluorescent treponemal antibody-absorption (FTA-ABS) test. A lumbar puncture was performed and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) studies returned positive for Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL). CSF cell count was significant for an elevated 22 white blood cells per microliter with a differential of 97% lymphocytes and 3% monocytes. CSF glucose level was normal at 46 mg/dL and CSF protein level was mildly increased at 60 mg/dL. CSF studies for HSV, VZV, and CMV were negative, as were CSF bacterial and viral cultures.

Given the finding of neurosyphilis and presumed ocular syphilis, she was immediately treated with a 14-day course of intravenous benzylpenicillin. Given rapid improvement, oral steroids were never initiated, and the patient was continued on prednisolone eye drops. Visual acuity at discharge was 20/400. Ophthalmologic exam at 3 months revealed only isolated chorioretinal atrophy in the superotemporal quadrant (Figure 1B) with resolution of symptoms and complete recovery of vision to 20/20 by 4 months.

Discussion

The differential diagnosis of posterior uveitis can be categorized as infectious or non-infectious, with auto-inflammatory and neoplastic etiologies accounting for the majority of non-infectious causes. Infectious causes, including syphilis, herpes family viruses, toxoplasmosis, and tuberculosis, should be ruled out because the treatment for non-infectious causes often involves steroids [1,9]. Among infectious etiologies, the most common cause of posterior uveitis is a herpes family virus infection [1]. Herpetic posterior uveitis is often fulminant and can result in rapid permanent vision loss from acute retinal necrosis and retinal detachment if not treated promptly [1,6].

Acute retinal necrosis is one of the clinical presentations of ocular herpetic disease. Acute retinal necrosis is a viral infection of the eye characterized by fulminant panuveitis and retinal periarteritis that can rapidly progress to full-thickness necrotizing retinitis and permanent vision loss. Typically affecting immunocompetent individuals, it is most frequently caused by VZV, followed by HSV 1 and 2, and rarely CMV; however, the culprit virus is often difficult to isolate in studies [5]. The prognosis is poor, with 50% of patients left with vision of 20/200 or worse [5,7]. Given its rapid progression and poor prognosis, whenever ARN is clinically suspected, such as with fulminant uveitis, empiric treatment against herpetic retinitis should be promptly initiated while workup is concurrently performed to confirm the diagnosis and/or evaluate for other possible etiologies [5,6,8].

Ocular syphilis can present at any stage but is most commonly associated with secondary syphilis. Ocular involvement occurs in 4.6% of patients with secondary syphilis, typically after resolution of other signs of secondary syphilis [2,3]. It varies widely in presentation; one or both eyes may be affected, and it can involve most parts of the eye from the conjunctiva to the extraocular cranial nerves [2]. Uveitis in either the anterior or posterior segment is the most common presentation and can occur as early as 6 weeks after initial infection [2]. Anterior uveitis can be nongranulomatous or granulomatous, mimicking ocular sarcoidosis and tuberculosis [10]. Posterior uveitis often presents as chorioretinitis but can also occur with retinitis alone. Ocular syphilis can also present with necrotizing retinitis and retinal vasculitis similar to ARN. Retinal vasculitis may present in isolation, mimicking retinal vein occlusions. Ocular nerve involvement may manifest as Argyll-Robertson pupil, extraocular palsies, or loss of visual acuity depending on the extent of damage [2].

Given its variable presentation, ocular syphilis presents a significant diagnostic challenge as it can mimic most other causes of uveitis and must be considered especially when an infectious etiology is suspected [1]. A comprehensive history including family, travel, and social history may provide important diagnostic clues. The United States Center for Disease Control and Prevention recommends performing a lumbar puncture to evaluate for neurosyphilis in all individuals with ocular syphilis as the concurrence rate is high [9]. Definitive diagnosis of syphilis requires visualization of T. pallidum under darkfield microscopy or with direct fluorescent antibody. However, this requires tissue samples or exudates, which are difficult to obtain. Thus, it is more commonly diagnosed indirectly with serological testing. Non-treponemal tests such as VDRL and RPR are sensitive but non-specific, with 1% to 2% of the United States population testing positive from conditions such as autoimmune diseases, HIV infection, and tuberculosis. Treponemal tests including FTA-ABS and T. pallidum particle agglutination (TP-PA) are more specific and are used as confirmatory tests following positive non-treponemal test results. Treponemal tests can rarely be falsely positive in other spirochetal infections, HIV infection, leprosy, and malaria [2]. There is no criterion standard test used to diagnose neurosyphilis; however, in clinical practice, a positive CSF VDRL is considered diagnostic. Unlike its serum counterpart, CSF FTA-ABS is highly sensitive but non-specific and is used to exclude neurosyphilis [2,11].

Treatment of ocular syphilis is identical to that of neurosyphilis. The preferred treatment consists of intravenous benzylpenicillin given at a dose of 18–24 million units (MU) per day for 10–14 days as a continuous infusion or as 3–4 MU every 4 hours [2,10]. Alternatively, 2.4 MU of intramuscular procaine penicillin per day with 500 milligrams of oral probenecid every 4 hours for 10–14 days can be given. CSF should be evaluated every 6 months until cell counts normalize [2]. Alternatively, ceftriaxone, administered as 2 grams daily intravenously for 10 days, has also been shown to be effective in the treatment of neurosyphilis [12,13]. The Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction may occur with treatment, and may worsen ocular syphilis, in which case pre-treatment with corticosteroids should be considered [10]. Adjunctive corticosteroid eye drops can be considered in patients with disease in anterior portions of the eye such as interstitial keratitis and anterior uveitis, and systemic corticosteroids in patients with deeper involvement such as posterior uveitis, scleritis, and optic neuritis [2]. Unlike ARN, ocular syphilis carries a favorable prognosis with a greater degree of visual recovery as inflammation subsides rapidly with treatment [2–4].

Conclusions

In summary, the diagnosis of ocular syphilis is challenging because the disease varies widely in presentation and presents similarly to other more common ocular conditions such as acute retinal necrosis [9,10]. Given the risk of permanent vision loss, patients who present with fulminant posterior uveitis should be empirically treated for herpetic acute retinal necrosis whenever suspected while simultaneous workup is conducted to evaluate alternative diagnoses such as ocular syphilis. When diagnosed, ocular syphilis is effectively treated with intravenous benzylpenicillin and carries a favorable prognosis if adequately treated.

Footnotes

Conflict of interests

No conflict of interests to disclose.

References:

- 1.Sudharshan S, Ganesh SK, Biswas J. Current approach in the diagnosis and management of posterior uveitis. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2010;58(1):29–43. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.58470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kiss S, Damico FM, Young LH. Ocular manifestations and treatment of syphilis. Semin Ophthalmol. 2005;20(3):161–67. doi: 10.1080/08820530500232092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parc CE, Chahed S, Patel SV, Salmon-Ceron D. Manifestations and treatment of ocular syphilis during an epidemic in France. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34(8):553–56. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000253385.49373.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Puech C, Gennai S, Pavese P, et al. Ocular manifestations of syphilis: recent cases over a 2.5-year period. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2010;248(11):1623–29. doi: 10.1007/s00417-010-1481-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong RW, Jumper JM, McDonald HR, et al. Emerging concepts in the management of acute retinal necrosis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2013;97(5):545–52. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2012-301983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wensing B, de Groot-Mijnes JD, Rothova A. Necrotizing and nonnecrotizing variants of herpetic uveitis with posterior segment involvement. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129(4):403–8. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sims JL, Yeoh J, Stawell RJ. Acute retinal necrosis: a case series with clinical features and treatment outcomes. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2009;37(5):473–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2009.02083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bansal R, Gupta V, Gupta A. Current approach in the diagnosis and management of panuveitis. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2010;58(1):45–54. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.58471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mandelcorn ED. Infectious causes of posterior uveitis. Can J Ophthalmol. 2013;48(1):31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2012.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doris JP, Saha K, Jones NP, Sukthankar A. Ocular syphilis: the new epidemic. Eye (Lond) 2006;20(6):703–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6701954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Timmermans M, Carr J. Neurosyphilis in the modern era. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75(12):1727–30. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.031922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghanem KG, Workowski KA. Management of adult syphilis. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(Suppl.3):S110–28. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marra CM, Boutin P, McArthur JC, et al. A pilot study evaluating ceftriaxone and penicillin G as treatment agents for neurosyphilis in human immunodeficiency virus-infected individuals. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30(3):540–44. doi: 10.1086/313725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]