Abstract

Background

Previous studies have shown that open cranial vault remodeling does not fully address the endocranial deformity. This study aims to compare endoscopic-assisted suturectomy with postoperative molding helmet therapy to traditional open reconstruction by quantifying changes in cranial base morphology and posterior cranial vault asymmetry.

Methods

Anthropometric measurements were made on pre- and 1-year postoperative three-dimensionally reconstructed computed tomography scans of 12 patients with unilateral lambdoid synostosis (eight open and four endoscopic-assisted). Cranial base asymmetry was analyzed using: posterior fossa deflection angle (PFA), petrous ridge angle (PRA), mastoid cant angle (MCA), and vertical and anterior-posterior (A-P) displacement of external acoustic meatus (EAM). Posterior cranial vault asymmetry was quantified by volumetric analysis.

Results

Preoperatively, patients in the open and endoscopic groups were statistically equivalent in PFA, PRA, MCA, and A-P EAM displacement. At one year postoperatively, open and endoscopic patients were statistically equivalent in all measures. Mean postoperative PFA for the open and endoscopic groups was 6.6 and 6.4 degrees, PRA asymmetry was 6.4 and 7.6 percent, MCA was 4.0 and 3.2 degrees, vertical EAM displacement was −2.3 and −2.3 millimeters, and A-P EAM displacement was 6.8 and 7.8 millimeters, respectively. Mean volume asymmetry was significantly improved in both open and endoscopic groups, with no difference in postoperative asymmetry between the two groups (p=0.934).

Conclusions

Patients treated with both open and endoscopic repair of lambdoid synostosis show persistent cranial base and posterior cranial vault asymmetry. Results of endoscopic-assisted suturectomy with postoperative molding helmet therapy are similar to those of open calvarial vault reconstruction.

Keywords: lambdoid synostosis, endoscopic repair, cranial base, cranial vault

INTRODUCTION

Unilateral lambdoid synostosis represents the least common form of single-suture craniosynostosis, with an incidence of 1 in 40,000 live births.1, 2 Majority of reports in the literature address diagnostic differentiation of lambdoid synostosis from deformational plagiocephaly, with few reports explicitly quantifying the postoperative course of established surgical treatments for this rare craniofacial malformation.3, 4

Conventional surgical treatment of patients with unilateral lambdoid synostosis is focused on correction of the external deformity of posterior cranial vault and generally does not address dysmorphology of the cranial base. Characteristic cranial base features include: deviation of the foramen magnum to synostotic side, asymmetry of petrous ridges and external acoustic meatus, and a mastoid bulge ipsilateral to the synostosis. These features have been shown to persist after traditional posterior cranial vault remodeling and are implicated in continued asymmetric development of the craniofacial skeleton.4 Endoscopic-assisted suturectomy combined with postoperative molding helmet therapy, as introduced by Jimenez and Barone in 1998,5 has shown promising qualitative results in improving the appearance of children with unilateral lambdoid synostosis.6,7 When performed under 6 months of age, the endoscopic procedure and subsequent helmet therapy are intended to take advantage of the rapid growth phase of the brain and drive the cranium towards normocephaly. Perioperative blood loss, intraoperative time, length of hospital stay, and cost of treatment are also lessened with endoscopic-assisted procedures.7,8

The open and endoscopic approaches have been shown by qualitative assessment to improve the most apparent deformities caused by lambdoid synostosis, but no current literature quantitatively compares the postoperative outcomes of the two techniques. In this study, we present a quantitative analysis of both cranial base and posterior cranial vault morphology after surgical correction of lambdoid synostosis. This review of our institution’s 30-year database represents an opportunity to assess the effectiveness of two surgical techniques in the treatment of patients with unilateral lambdoid synostosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

After obtaining Institutional Review Board approval, a retrospective chart review of patients treated at the Cleft Palate and Craniofacial Institute of Saint Louis Children’s Hospital between 1990 and 2012 identified 25 children with isolated unilateral lambdoid synostosis (ULS). Patients with multiple suture involvement and/or syndromic craniosynostosis were excluded from this study. Inclusion criteria were the presence of unilateral lambdoid synostosis confirmed by computed tomography (CT) and availability of preoperative and ≥1 year postoperative CT scans suitable for three-dimensional reconstruction and anthropometric analysis (slice thickness ≤2mm). Of the 25 patients with isolated ULS, nine were excluded due to inadequate CT data; four were excluded due to lack of consent. A total of 12 patients met inclusion criteria: eight underwent posterior cranial vault remodeling and four were treated by endoscopic-assisted strip suturectomy with postoperative molding helmet therapy. The endoscopic technique began at our institution in 2006 and was offered to patients younger than 6 months of age.

All 8 patients in the open group underwent posterior cranial vault reconstruction involving the parietal and occipital bones. The 4 patients in the endoscopic group underwent endoscopic-assisted suturectomy, which involves resection of the fused lambdoid suture followed by molding helmet therapy till one year of age.

Two patients in the open reconstruction group were excluded in the analysis of the posterior cranial vault, due to motion artifact above the level of the cranial base. Thus, assessment of the posterior cranial vault asymmetry arm of this study included six patients in the open reconstruction group and four in the endoscopic group.

Anthropometric measurements were made using Analyze 11.0 image analysis software (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, 2012). Axial slices from pre- and postoperative CT scan data were reconstructed for three-dimensional analysis. Each scan was oriented to a modified Frankfort horizontal plane defined by three points: the left and right inferior orbital rims and the external acoustic meatus (EAM) contralateral to the affected suture. The traditional Frankfort horizontal (defined as the plane passing through the left inferior orbital rim and both the left and right external acoustic meatus)9 was modified because inferior displacement of the EAM ipsilateral to the fused lambdoid suture makes it an unreliable landmark for orientation purposes.2, 3 Frontal orientation was defined by setting left and right endocanthia in the same coronal plane.

Cranial Base

A threshold for bone visualization was defined for each scan. An endocranial view was created by removing the axial CT slices above the orbits. Cranial base asymmetry between synostotic and nonsynostotic sides was analyzed using previously defined measures: posterior fossa deflection angle (PFA), petrous ridge angle (PRA), mastoid cant and vertical and anterior-posterior displacement of the external acoustic meatus (EAM) ipsilateral to the fused suture (Fig. 1).10,11 The mastoid cant angle was reported relative to the horizontal plane of orientation, and displacement of the ipsilateral EAM was reported relative to the contralateral EAM. Measurements were obtained twice by a single observer. The mean of the two values for each measure was used in the final analysis.

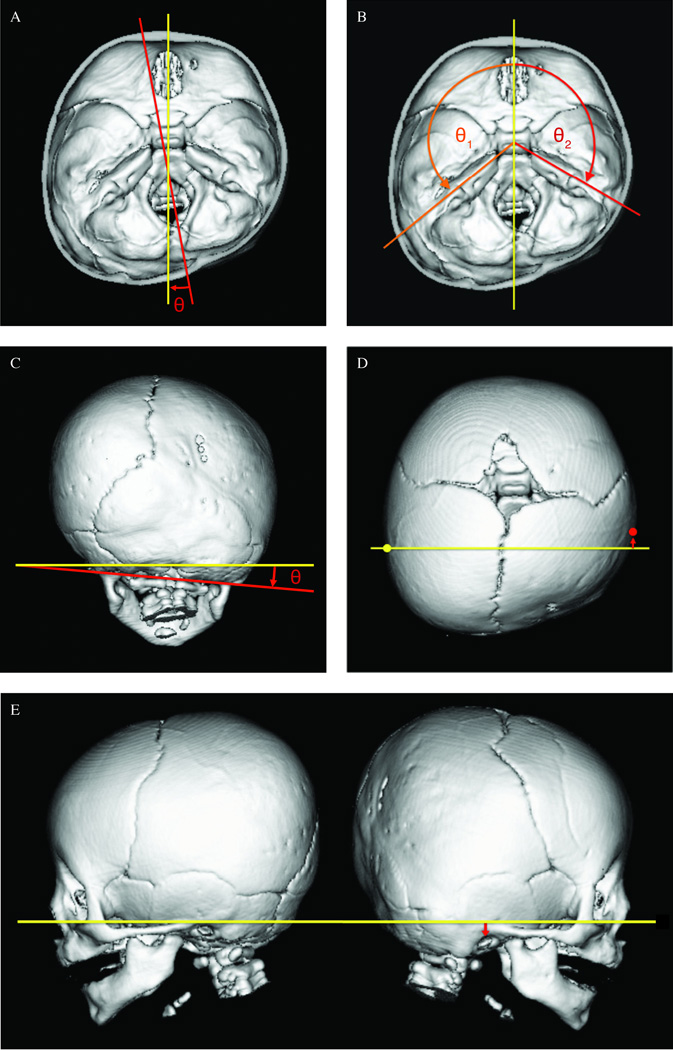

Figure 1.

A. Posterior Fossa Deflection Angle (PFA): The PFA represents the lateral deviation of the foramen magnum. The angle was defined by the intersection of the line bisecting the foramen magnum (red), and the line bisecting the cribriform plate (yellow).10 A positive angle indicates deviation towards the synostotic side.

B. Petrous Ridge Angle (PRA): The PRA for each side was measured from the line bisecting the cribriform plate (yellow) to the line of each petrous ridge (orange, red).10,11 The asymmetry between the synostotic (affected) and nonsynostotic (unaffected) sides was calculated as a percent difference, defined as 100*[(affected-unaffected)/((affected+unaffected)/2)].12

C. Mastoid Cant: Mastoid cant was defined as the angle between the Frankfort Horizontal plane (yellow) and the line connecting the left and right mastoid processes (red). A positive angle represents canting towards the synostotic side.

D. Anterior-Posterior External Acoustic Meatus Displacement: The A-P displacement of the ipsilateral EAM (red arrow) was measured relative to a coronal plane through the contralateral EAM (yellow), parallel to the frontal plane of orientation.

E. Vertical External Acoustic Meatus Displacement: The vertical displacement of the ipsilateral EAM (red arrow) was measured relative to the Frankfort Horizontal plane of orientation (yellow).

In order to account for cranial growth and allow for comparison between pre- and postoperative measurements of petrous ridge angle (PRA) asymmetry, the difference between the petrous ridge angles of the affected and unaffected sides on each scan was calculated as a percent relative difference, defined as 100*[(affected-unaffected)/((affected+unaffected)/2)].12 Absolute angles were also analyzed in a comparison between open and endoscopic groups.

For analysis of ear position, negative values indicate an inferior or posterior displacement, and positive values indicate anterior or superior displacement of the ipsilateral EAM relative to the contralateral EAM.

Posterior Cranial Vault

To facilitate volume measurements of the posterior cranial vault, each three-dimensional reconstruction was divided along a midsagittal plane including the line connecting sella to nasion and perpendicular to the horizontal plane of orientation. Each hemisphere created by this midsagittal division was further divided along a coronal plane at the level of the EAM contralateral to the fused suture. Because the most voluminous and prominent deformity caused by unilateral lambdoid synostosis is concentrated in the parietal region, only the quadrant posterior to this coronal plane was used in the volume analysis. The mastoid process was excluded in order to show the full extent of the asymmetry between the parietal regions of the two hemispheres. For this reason, the inferior limit of the quadrant of interest was defined at the level of the horizontal plane of orientation (Fig. 2). Volume measurements were made on each scan at a threshold for skin visualization in order to best approximate the presentation of the posterior cranial vault in a clinical setting.

Figure 2. Quadrants of Posterior Cranial Vault Comparison.

The left (yellow) and right (orange) posterior quadrants isolated for volumetric analysis. In this patient, the left lambdoid suture is fused.

For each patient’s pre- and postoperative scan, the respective volumes of the left and right posterior cranial segments were calculated in cubic centimeters. To allow comparison of pre- and postoperative scans and account for cranial growth over time, as for the PRA cranial base measurement, a percent asymmetry was calculated for each scan between the synostotic (affected) and nonsynostotic (unaffected) sides, defined as 100*[(affected-unaffected)/((affected+unaffected)/2)].12 Preoperative asymmetry and postoperative change was recorded.

Statistics

All data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 19, (Chicago, IL). Mean pre- and postoperative values were compared within the open and endoscopic groups using a 2-tailed Student’s t-test. Postoperative outcomes were compared between the open and endoscopic groups using linear regression analysis to account for pre-operative severity. The effect of age at surgery on postoperative outcomes and correlations between cranial base and volume asymmetries were analyzed using 2-tailed Student’s t-tests. Intra-rater reliability was analyzed using one-way average measures intra-class correlation coefficients. Detectable differences were determined using the PS Power and Sample Size Program version 3.0.13,14 These tests set open case results as the controls, were two-sided, and fixed power to 0.80 and type I error to 0.05. The standard deviation of the open cases and correlation coefficients between the pre- and postoperative results were used to estimate sigma in these calculations.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Given small sample size, no statistically significant difference in age was found between open and endoscopic groups at either time point (p≥0.177). In a bivariate analysis, age at surgery was not significantly correlated to either preoperative or postoperative asymmetry of any cranial base or volume measurements (p≥0.255). Intra-rater reliability testing showed intra-class correlation coefficients ≥0.985 for all five cranial base measures and ≥0.949 for volume measures.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Case | Age at pre-op scan (months) |

Age at Surgery (months) |

Age at post-op scan (months) |

Operative Time (min) |

Estimated Blood Loss (mL) |

Transfusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Open | ||||||

| 1 | 15.4 | 17.4 | 29.6 | 225 | 300 | Yes |

| 2 | 6.1 | 7.7 | 22.5 | 217 | 200 | Yes |

| 3 | 30.7 | 35.0 | 84.0 | 330 | 1000 | Yes |

| 4 | 12.5 | 13.3 | 32.4 | 312 | 175 | Yes |

| 5 | 6.9 | 8.5 | 21.0 | 315 | 500 | Yes |

| 6 | 5.6 | 10.2 | 25.1 | 335 | 350 | Yes |

| 7 | 5.7 | 6.2 | 17.4 | 285 | 80 | Yes |

| 8 | 3.8 | 4.6 | 19.0 | 375 | 200 | Yes |

| Mean | 10.8 | 12.8 | 31.4 | 300 | 350 | |

| Endoscopic | ||||||

| 9 | 4.2 | 4.4 | 16.6 | 65 | 10 | No |

| 10 | 5.9 | 6.4 | 19.7 | 58 | 20 | No |

| 11 | 5.8 | 6.4 | 20.0 | 56 | 10 | No |

| 12 | 4.4 | 4.8 | 17.7 | 55 | 20 | No |

| Mean | 5.1 | 5.5 | 18.5 | 59 | 15 |

Cranial Base

In an analysis of all 12 patients together, measures of posterior fossa deflection angle, mastoid cant angle, and vertical EAM displacement were significantly improved postoperatively (p≤0.029). Petrous ridge angle asymmetry and anterior-posterior EAM displacement remained statistically unchanged (p≥0.131).

Open Reconstruction

Seven out of eight patients had a posterior fossa deflection towards the synostotic suture. Mean preoperative and postoperative PFA were 9.4° ± 2.2° and 6.6° ± 1.5°, respectively, towards the affected side (p=0.050). Preoperatively, the contralateral petrous ridge angle (129.3° ± 1.5°) was significantly wider than the ipsilateral angle (119.1° ± 1.6°, p=0.004). This asymmetry persisted postoperatively: mean contralateral PRA was 129.1° ± 1.3° and mean ipsilateral PRA was 121.2° ± 1.9°, (p=0.003). Neither the ipsilateral nor the contralateral petrous ridge angle significantly changed after surgical repair (p≥0.164). Correspondingly, a nonsignificant improvement in petrous ridge angle asymmetry occurred postoperatively (p=0.179). The mastoid cant angle significantly improved (p=0.006); however, downward sloping towards the synostotic side remained in all patients. All patients had inferior and anterior ipsilateral EAM displacement pre- and postoperatively. Anterior-posterior position of the ipsilateral EAM did not significantly change (p=0.792), but improvement in vertical position was seen postoperatively (p=0.009).

Endoscopic Group

Given the scarcity of endoscopic data (n=4), significant differences between measurements pre- and post-repair were not to be expected. This expectation was validated by the data; pre- and post-operative comparisons for all measures yielded p-values ≥ 0.185. Due to small sample size, we looked for trends in the data. Posterior fossa deflection, petrous ridge angle asymmetry, and mastoid cant decreased in three of the four cases. The contralateral petrous ridge angle was significantly wider than the ipsilateral angle in both pre- and postoperative measurements. Preoperatively, mean contralateral PRA was 129.3° ± 1.5° and mean ipsilateral PRA was 118.9 ° ± 2.4° (p=0.018). Postoperatively, the mean contralateral and ipsilateral PRA was 130.3° ±1.1° and 120.8° SE ±1.8° (p=0.022). Neither the ipsilateral nor the contralateral petrous ridge angle was significantly changed postoperatively (p≥0.268). Vertical EAM displacement did not show any trend, with two subjects’ results increased and two decreased post-surgery. Anterior-posterior EAM displacement decreased in one of four cases. Both pre- and postoperatively, three of four patients in the endoscopic group had inferior and anterior displacement of the ear; one had superior and anterior displacement.

Comparison of Open and Endoscopic Groups

The results of anthropometric measurements are displayed in Table 2 with representative examples from each group in Figure 3. Preoperatively, patients in the open and endoscopic groups were statistically equivalent in the measures of PFA (p=0.720), PRA (p=0.958), MCA (p=0.085), and A-P EAM displacement (p=0.591). The open group had more inferior EAM displacement preoperatively (p=0.043). Postoperatively, there were no statistical differences in any of the five cranial base measures between open and endoscopic groups (p≥0.387).

Table 2.

Cranial base measurements of 8 open and 4 endoscopic cases of lambdoid synostosis

| Case | Posterior Fossa Deflection Angle (PFA) (degrees) |

Petrous Ridge Angle Asymmetry (PRA) (degrees) |

Mastoid

Cant (MCA) (degrees) |

Vertical Displacement of Ipsilateral EAM (mm) |

Anterior- Posterior Displacement of Ipsilateral EAM (mm) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | |

| Open | ||||||||||

| 1 | 12.8 | 11.4 | 4.5 | 4.8 | 6.9 | 4.5 | −5.8 | −3.0 | 6.3 | 4.5 |

| 2 | 9.8 | 6.8 | 6.3 | 7.4 | 5.6 | 3.8 | −4.3 | −1.5 | 6.8 | 10.5 |

| 3 | 10.1 | 6.0 | 13.6 | 5.8 | 3.7 | 3.4 | −5.5 | −1.5 | 7.0 | 4.8 |

| 4 | −3.6 | −0.5 | 5.7 | 10.6 | 11.7 | 6.0 | −11.5 | −3.0 | 3.8 | 7.8 |

| 5 | 9.3 | 8.8 | 6.9 | 5.8 | N/A | 3.2 | N/A | −1.8 | N/A | 8.0 |

| 6 | 18.2 | 12.2 | 25.0 | 18.3 | 7.6 | 3.6 | −6.0 | −2.8 | 8.5 | 10.0 |

| 7 | 7.8 | 5.0 | 12.9 | 9.4 | 6.4 | 3.3 | −3.0 | −0.5 | 6.5 | 5.0 |

| 8 | 11.0 | 3.1 | 7.2 | 1.2 | 10.7 | 4.5 | −5.0 | −4.3 | 6 | 4.3 |

| Mean | 9.4 | 6.6 | 10.2 | 7.9 | 7.5 | 4.1* | −5.9 | −2.4* | 6.4 | 6.7 |

| Endoscopic | ||||||||||

| 9 | 12.3 | 6.9 | 13.4 | 10.5 | 3.3 | 1.9 | −1.5 | −3.5 | 9.0 | 8.0 |

| 10 | 2.5 | 7.8 | 8.3 | 12.8 | 3.7 | 4.6 | −1.8 | −3.0 | 5.8 | 9.0 |

| 11 | 12.8 | 9.8 | 14.6 | 11.4 | 4.3 | 1.8 | 0.3 | 1.0 | 5.3 | 6.0 |

| 12 | 4.9 | 4.2 | 5.3 | 3.1 | 6.7 | 4.6 | −5.3 | −3.5 | 3.0 | 8.0 |

| Mean | 8.1 | 6.4 | 10.4 | 9.5 | 4.5 | 3.2 | −2.1 | −2.3 | 5.8 | 7.8 |

Foramen magnum deviation: positive values indicate deviation toward affected suture; negative values indicate deviation away from affected suture.

Petrous ridge angle asymmetry: positive values indicate a wider ipsilateral petrous ridge angle.

Mastoid cant: positive values indicate a downward tilting ipsilateral mastoid bulge.

Vertical displacement of ipsilateral EAM: Negative values indicate inferior position of ipsilateral ear.

Anterior-Posterior displacement of ipsilateral EAM: Positive values indicate anterior position of ipsilateral ear.

Values are means of two measurements taken by a single observer.

N/A: data not available

p<0.05

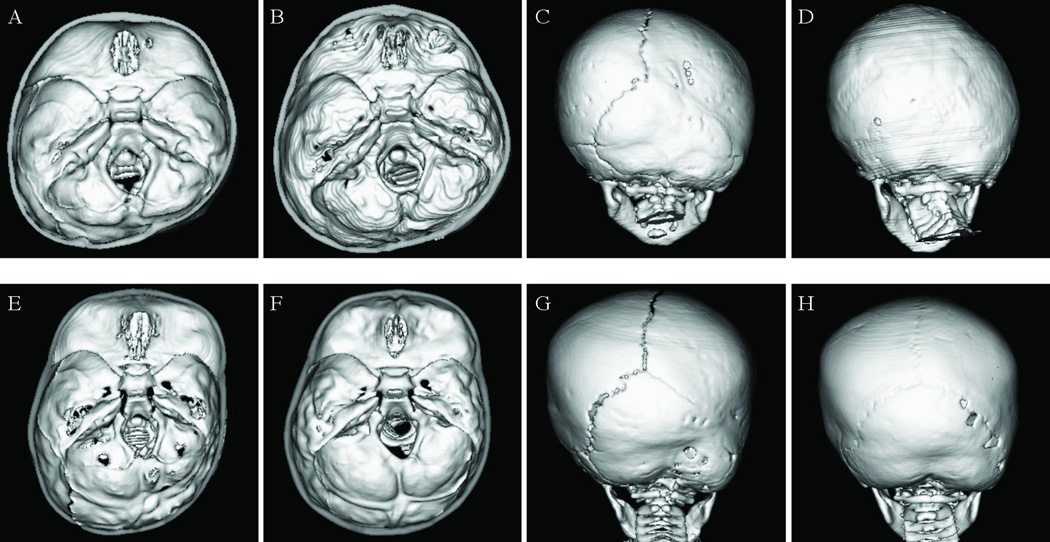

Figure 3. Pre- and postoperative CT images of 2 patients with right-sided lambdoid synostosis.

Panels A–D (top row) show Case 2, treated with open reconstruction, and panels E-H (bottom row) show case 11, treated with endoscopic-assisted suturectomy and molding helmet therapy.

After adjusting for preoperative asymmetry in a linear regression model, open and endoscopic groups had equivalent postoperative measurements in PFA (R=0.844, β=0.542, p=0.691), PRA (R=0.745, β=1.090, p=0.551), MCA (R=0.705, β=−0.030, p=0.967), vertical EAM displacement (R=0.521, β=−1.141, p=0.359), and anterior-posterior EAM displacement (R=0.288, β=1.207, p=0.459). Preoperative asymmetry, regardless of surgery type, was a significant predictor for PFA (p=0.001), PRA (p=0.010), and MCA (p=0.047), and not significant for vertical EAM displacement (p=0.123), and A-P EAM displacement (p=0.644). In order to detect differences between the groups, the slopes of the regression lines (β) would have to have differed by the following: PFA=0.80, PRA=1.33, MCA=0.59, vertical EAM=1.06, and A-P EAM=2.62.

Posterior Cranial Vault

Posterior cranial vault volume measurements are summarized in Table 3. Preoperative cranial vault asymmetry of the two groups was statistically equivalent (p=0.548). Average percent asymmetry between the nonsynostotic and synostotic sides was 27.9 ± 1.8 % in the open group and 30.9 ± 5.2 % in the endoscopic group. Postoperatively, asymmetries were significantly reduced to 16.7 ± 3.3 % and 17.1 ± 3.3 %, respectively, in the open and endoscopic groups (p≤0.021) (Fig. 4). In a linear regression model adjusted for preoperative severity, the two groups had equivalent postoperative volume asymmetry of the posterior cranial vault (R=0.541, β=−1.237, p=0.792), β to detect difference = 2.72.

Table 3.

Posterior cranial vault volume measurements

| Case | Preoperative | Postoperative | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Synostotic (cm3) |

Nonsynostotic (cm3) |

Asymmetry (%) |

Synostotic (cm3) |

Nonsynostotic (cm3) |

Asymmetry (%) |

Improvement** (%) |

p | |

| Open | ||||||||

| 1 | 416 | 533 | 24.8 | 483 | 614 | 24.0 | 0.8 | |

| 2 | 201 | 274 | 30.6 | 284 | 356 | 22.5 | 8.1 | |

| 3 | 391 | 516 | 27.5 | 433 | 542 | 22.3 | 5.2 | |

| 6 | 192 | 269 | 33.3 | 349 | 428 | 20.5 | 12.8 | |

| 7 | 259 | 321 | 21.5 | 397 | 400 | 0.7 | 20.7 | |

| 8 | 222 | 301 | 30.3 | 448 | 504 | 11.9 | 18.4 | |

| Mean* | 27.9 | 16.7 | 11.2 | 0.016 | ||||

| Endoscopic | ||||||||

| 9 | 174 | 275 | 45.2 | 330 | 435 | 27.6 | 17.6 | |

| 10 | 225 | 315 | 33.1 | 362 | 408 | 12.0 | 21.2 | |

| 11 | 257 | 329 | 24.5 | 380 | 429 | 12.1 | 12.4 | |

| 12 | 228 | 278 | 20.0 | 393 | 451 | 13.7 | 6.3 | |

| Mean* | 30.8 | 17.1 | 13.7 | 0.021 | ||||

| p | 0.548 | 0.934 | 0.601 | |||||

Mean absolute asymmetries (cm3) are not reported to avoid comparison between children of different ages. % asymmetry values are size-adjusted and facilitate comparison of morphology between children of varying cranial vault volumes.

% Improvement = (preoperative % asymmetry) – (postoperative % asymmetry)

Cases 4 and 5 were excluded due to motion artifact.

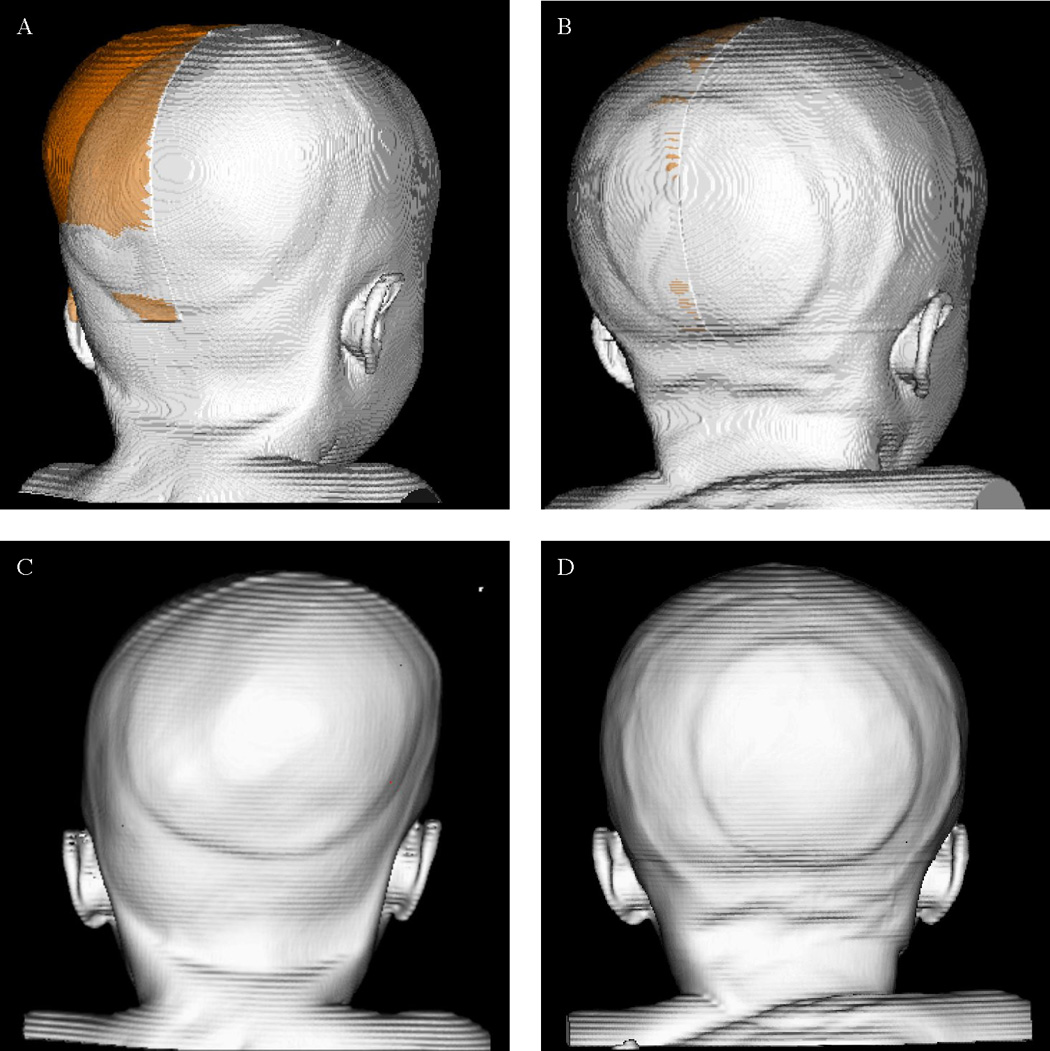

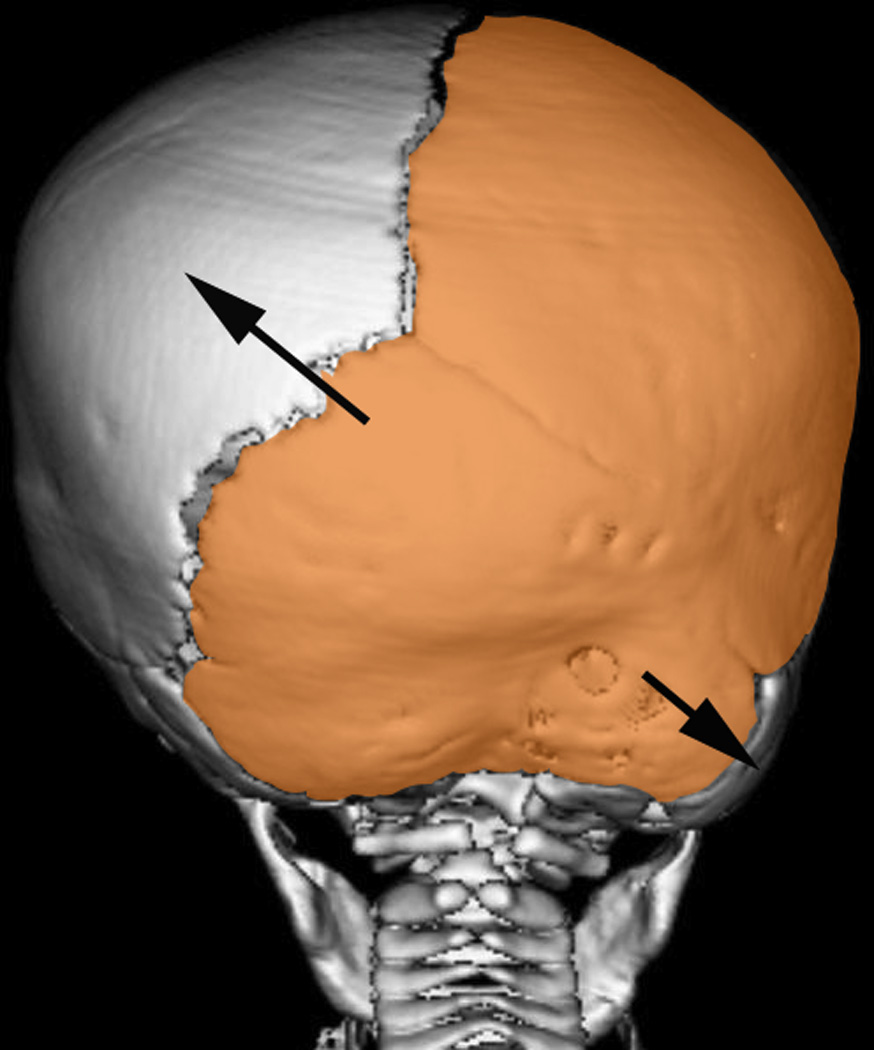

Figure 4. Volume Asymmetry & Postoperative Improvement.

Panels A–D represents a single patient with left lambdoid synostosis.

A. Preoperative asymmetry: The right posterior quadrant volume is reflected across the midsagittal plane and superimposed on the left side. The volume in orange represents the volume asymmetry between the two sides, where the right (nonsynostotic) side is larger and protrudes past the contour of the left (synostotic).

B. Postoperative asymmetry: The volume of asymmetry (orange) is markedly reduced.

C & D: Posterior views of pre- and postoperative morphology.

Cranial Base and Posterior Cranial Vault Asymmetry

Petrous ridge angle asymmetry and posterior cranial vault volume asymmetry were used for comparison of cranial base and posterior cranial vault outcomes, as both measures were calculated as percent asymmetries. There was no significant correlation between PRA and cranial vault asymmetry preoperatively (p=0.368) or postoperatively (p=0.911).

DISCUSSION

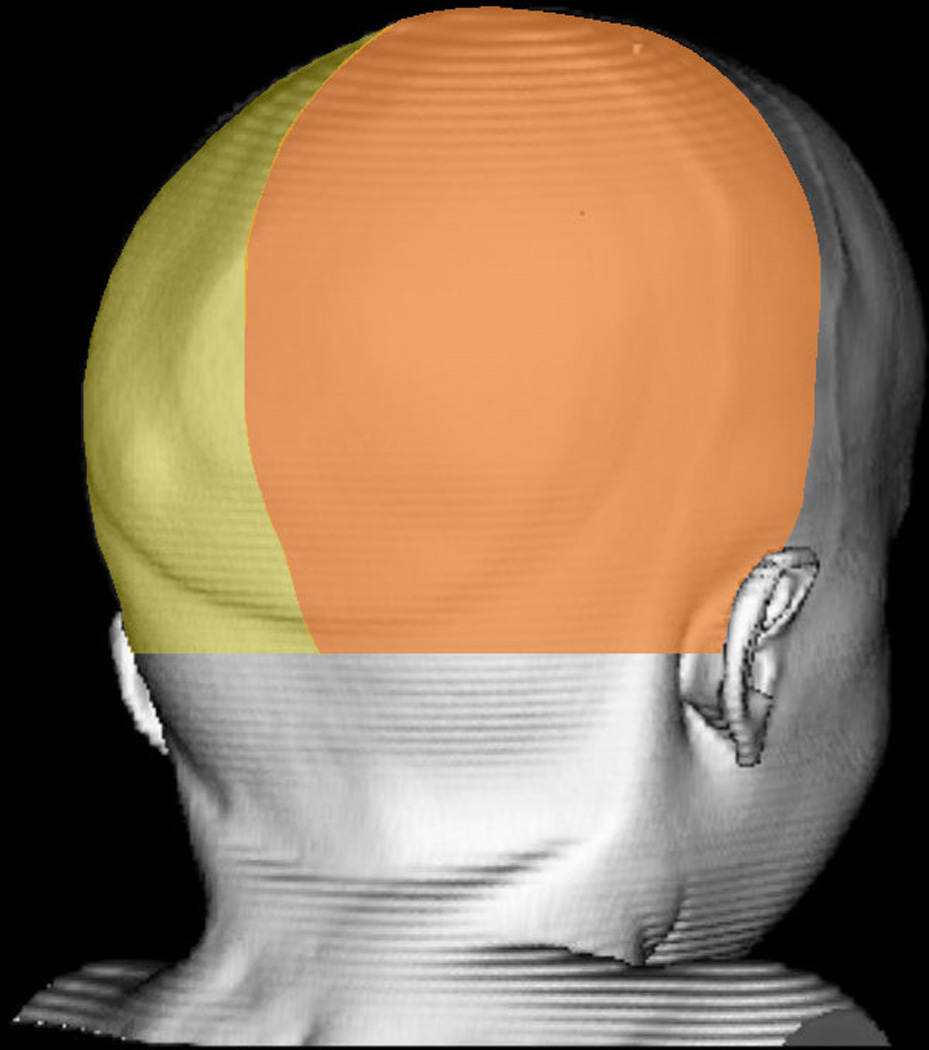

Driven by the necessity for clear diagnostic criteria in differentiation of true lambdoid synostosis from deformational plagiocephaly, characteristic head shape of lambdoid synostosis, as defined by Huang and colleagues in 1996 and revised several times since, has been the primary subject of available literature on the topic.1 Most consistent phenotypic signs of true lambdoid synostosis are (1) occipital flattening on the synostotic side with contralateral parietal bossing and (2) ipsilateral occipitomastoid prominence.2,3 Surgical correction of the synostosis is indicated to correct these dysmorphologies, as conservative management of lambdoid synostosis has been shown to result in severe cranial asymmetry.3 Delashaw and colleagues in their theory described the compensatory cranial vault growth patterns seen in patients with craniosynostosis, not explained by Virchow’s model.15, 16 Their hypothesis is based on the following rules: (1) fusion of the suture creates a single bone plate with decreased growth potential, (2) increased bone deposition away from the bone plate, (3) perimeter sutures adjacent to the fused suture compensate in growth more than distant sutures. Applying this theory to patients with lambdoid synostosis creates a parieto-occipital bone plate ipsilateral to the fused suture (Fig. 5). This bone plate, with its decreased growth potential, occupies the majority of the posterior cranial fossa on the synostotic side causing ipsilateral occipitoparietal flattening. Increased bone formation away from the parieto-occipital bone plate causes contralateral parietal bossing. Also, formation of the mastoid bulge is explained by increased bone deposition away from the bone plate along the occipitomastoid suture.

Figure 5. Application of Delashaw’s theory for calvarial growth in lambdoid synostosis.

(Orange area) Parieto-occipital bone plate ipsilateral to the fused suture. (Arrow) Increased bone deposition away from the bone plate creating contralateral parietal and ipsilateral mastoid bossing.

Cranial Base

Unilateral lambdoid synostosis causes a distinct cranial base deformity.10, 17 Lo and colleagues described an “overt dysmorphology of the endocranial base” affecting mainly the posterior fossa, characterized by an anteriorly displaced petrous ridge ipsilateral to the fused suture, inferiorly displaced ipsilateral posterior cranial fossa, and posterior fossa midline deviation towards the synostotic side.17 Smartt et al.10 and Ploplys et al.11 further quantified the cranial base asymmetry that defines lambdoid synostosis, measuring posterior fossa deflection angle toward the affected side, petrous ridge asymmetry reflecting an enlarged contralateral posterior cranial fossa, mastoid cant towards the affected side, and displacement of the external acoustic meatus. Most recently, Elliott and colleagues demonstrated in a group of five patients that endocranial asymmetry is not significantly improved by traditional calvarial vault remodeling.4

The preoperative pattern of endocranial asymmetry in our series of patients was consistent with previous reports.4, 10, 17 The findings of Elliott and colleagues of persistent postoperative cranial base asymmetry were also evidenced in our data, though tendencies towards small improvements were observed.4 The one exception was case #10 who had an increase in PFA, PRA, and MCA postoperatively; however, the patient’s posterior cranial vault volume asymmetry was reduced from 33% preoperatively to 12% postoperatively. Postoperative anthropometric analysis of cranial base morphology, despite revealing persistent asymmetries, showed remarkably similar outcomes between the open and endoscopic groups: one year after surgery, no average measure of asymmetry varied more than 1 mm or 1.6 degrees between open and endoscopically treated patients.

Posterior Cranial Vault

Quantitative reduction in volume asymmetry in our series of patients supports previous reports of qualitative head shape improvement.3,6,7,18 The significant improvement in posterior cranial vault asymmetry for both open and endoscopic groups is consistent with the surgical approaches used, as both open reconstruction and endoscopic suturectomy with postoperative molding helmet therapy aim to manipulate the posterior cranial vault. However, similar to cranial base asymmetry, posterior cranial asymmetry was not entirely eliminated in either the open or endoscopic group. Aside from one patient in the open reconstruction group, all patients had a postoperative volume asymmetry of >10%.

Open and Endoscopic Groups

This study provides a detailed quantitative postoperative comparison of open calvarial vault reconstruction and endoscopic-assisted strip craniectomy for lambdoid synostosis. While neither procedure achieved complete symmetry of the posterior cranial vault and base, both produced equivalent postoperative outcomes in our series of patients.

Cranial base asymmetries are expected postoperatively as this region is not directly corrected during either operation. Theoretically, the endoscopic technique has a better chance of correcting cranial base asymmetry, as it is relies on the rapid growth phase of the brain to improve the dysmorphology during early childhood. We offer this procedure between 2 to 6 months of age, with the ideal patient being closer to 2 months of age to take full advantage of rapid brain growth. No differences in outcome measures were seen based on age in the endoscopic group; however, the patients ranged between 4.4 and 6.4 months of age.

Limitations

The main limitations of this study are the small sample size and age discrepancy between open and endoscopic groups. The scarcity of patients with lambdoid synostosis did not allow for age-matching of the two groups, but statistical analysis showed that age at surgery was not significantly related to either preoperative severity or postoperative outcome in cranial base or volume measurements. Our analysis does not support the concern that the older patients undergoing open reconstruction may have had more severe preoperative asymmetries or inferior postoperative outcomes.

Another limitation of this study is that not all of the reconstructions were performed by the same surgeon over the 22-year reported institutional experience. Techniques in open cranial vault reconstruction may vary more than endoscopic repairs between surgeons; this heterogeneity should be considered, but given the rarity of presentation of lambdoid synostosis, should not preclude the reporting of these patients’ outcomes.

The small sample size reflects the infrequent occurrence of lambdoid synostosis and precludes definitive conclusions based on statistical analysis, but our series of 12 cases is among the largest in the recent literature. There has previously been concern in the literature about unwarranted operative intervention for nonsynostotic plagiocephaly, but all cases in this study were confirmed lambdoid synostoses by preoperative CT scan. Future directions would be to perform multicenter studies to accurately assess outcomes and evaluate the benefit of early correction (2 months of age) in patients treated by endoscopic-assisted suturectomy and helmet molding therapy.

CONCLUSIONS

Posterior fossa deflection, petrous ridge asymmetry, mastoid cant, and anteroinferior ipsilateral ear displacement are characteristic features of lambdoid synostosis and are not fully corrected by open reconstruction or endoscopic-assisted suturectomy. Endoscopic repair under 6 months of age with orthotic therapy obtained comparable cranial base asymmetry outcomes to open reconstruction. Posterior cranial vault asymmetry is significantly improved by both procedures.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the Children’s Surgical Sciences Institute for their support.

This research was supported by the Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences grants UL1 TR000448 and TL1 TR000449 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

The authors have no financial disclosures or commercial associations that might suggest a conflict of interest in relation to this work.

Presented at the American Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Association (ACPA)

Annual Meeting, Indianapolis, IN, March 24–29, 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Huang MH, Gruss JS, Clarren SK, et al. The differential diagnosis of posterior plagiocephaly: True lambdoid synostosis versus positional molding. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;98:765–774. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199610000-00001. discussion 775–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Menard RM, David DJ. Unilateral lambdoid synostosis: Morphological characteristics. J Craniofac Surg. 1998;9:240–246. doi: 10.1097/00001665-199805000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smartt JM, Jr, Reid RR, Singh DJ, Bartlett SP. True lambdoid craniosynostosis: Long-term results of surgical and conservative therapy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120:993–1003. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000278043.28952.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elliott RM, Smartt JM, Taylor JA, Bartlett SP. Does conventional posterior vault remodeling alter endocranial morphology in patients with true lambdoid synostosis? J Craniofac Surg. 2013;24:115–119. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e318270fb4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jimenez DF, Barone CM. Endoscopic craniectomy for early surgical correction of sagittal craniosynostosis. J Neurosurg. 1998;88:77–81. doi: 10.3171/jns.1998.88.1.0077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Proctor MR. Endoscopic cranial suture release for the treatment of craniosynostosis—is it the future? J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23:225–228. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e318241b8f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berry-Candelario J, Ridgway EB, Grondin RT, Rogers GF, Proctor MR. Endoscope-assisted strip craniectomy and postoperative helmet therapy for treatment of craniosynostosis. Neurosurg Focus. 2011;31:E5. doi: 10.3171/2011.6.FOCUS1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jimenez DF, Barone CM, Cartwright CC, Baker L. Early management of craniosynostosis using endoscopic-assisted strip craniectomies and cranial orthotic molding therapy. Pediatrics. 2002;110:97–104. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daboul A, Schwahn C, Schaffner G, et al. Reproducibility of Frankfort horizontal plane on 3D multi-planar reconstructed MR images. PLoS One. 2012;7:e48281. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smartt JM, Jr, Elliott RM, Reid RR, Bartlett SP. Analysis of differences in the cranial base and facial skeleton of patients with lambdoid synostosis and deformational plagiocephaly. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127:303–312. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181f95cd8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ploplys EA, Hopper RA, Muzaffar AR, et al. Comparison of computed tomographic imaging measurements with clinical findings in children with unilateral lambdoid synostosis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123:300–309. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31819346b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Netherway DJ, Abbott AH, Gulamhuseinwala N, et al. Three-dimensional computed tomography cephalometry of plagiocephaly: Asymmetry and shape analysis. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2006;43:201–210. doi: 10.1597/04-174.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dupont WD, Plummer WD., Jr Power and sample size calculations. A review and computer program. Controlled clinical trials. 1990;11:116–128. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(90)90005-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dupont WD, Plummer WD., Jr Power and sample size calculations for studies involving linear regression. Controlled clinical trials. 1998;19:589–601. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(98)00037-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Delashaw JB, Persing JA, Broaddus WC, Jane JA. Cranial vault growth in craniosynostosis. J Neurosurg. 1989;70:159–165. doi: 10.3171/jns.1989.70.2.0159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Virchow R. Über den Cretinismus namentlich in Franken, und über pathologische Schädelformen. Verh Phys Med Ges Wurzburg. 1851;2:230. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lo LJ, Marsh JL, Pilgram TK, Vannier MW. Plagiocephaly: Differential diagnosis based on endocranial morphology. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;97:282–291. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199602000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clayman MA, Murad GJ, Steele MH, Seagle MB, Pincus DW. History of craniosynostosis surgery and the evolution of minimally invasive endoscopic techniques: The University of Florida experience. Ann Plast Surg. 2007;58:285–287. doi: 10.1097/01.sap.0000250846.12958.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]