Abstract

Focal cortical dysplasia (FCD) is the most common cause of pediatric epilepsy and the third most common lesion in adults with treatment-resistant epilepsy. Advances in MRI have revolutionized the diagnosis of FCD, resulting in higher success rates for resective epilepsy surgery. However, many histologically confirmed FCD patients have normal pre-surgical MRI studies (‘MRI-negative’), making pre-surgical diagnosis difficult. The purpose of this study is to test whether a novel MRI post-processing method successfully detects histopathologically-verified FCD in a sample of patients without visually appreciable lesions. We applied an automated quantitative morphometry approach which computed five surface-based MRI features and combined them in a machine learning model to classify lesional and non-lesional vertices. Accuracy was defined by classifying contiguous vertices as “lesional” when they fell within the surgical resection region. Our multivariate method correctly detected the lesion in 6 of 7 MRI-positive patients, which is comparable with the detection rates that have been reported in univariate vertex-based morphometry studies. More significantly, in patients that were MRI-negative, machine learning correctly identified 14 out of 24 FCD lesions (58%). This was achieved after separating abnormal thickness and thinness into distinct classifiers, as well as separating sulcal and gyral regions. Results demonstrate that MRI-negative images contain sufficient information to aid in the in-vivo detection of visually elusive FCD lesions.

Keywords: epilepsy, focal cortical dysplasia, machine learning, structural MRI

1. Introduction

Despite advances in pharmacotherapy for the treatment of epilepsy, approximately one third of patients remain refractory to medications [1]. For patients with treatment-resistant epilepsy (TRE), the best option for achieving seizure freedom is often surgical resection. In patients where a focal seizure onset is identified through a comprehensive presurgical evaluation, surgical resection results in seizure freedom rates ranging from 30–80% [3]. Despite a growing number of studies demonstrating that surgery is effective for patients with focal TRE, it remains underutilized [4]. Patients who lack an MRI-visible lesion are less likely to be referred to specialized epilepsy center by neurologists5 and many epilepsy specialists are reluctant to operate without a well-defined lesion.

Focal cortical dysplasia (FCD), a malformation of cortical development (MCD), is the most common epileptogenic lesion in children and the third most common in adults with TRE [6, 7]. Typical MRI features of FCD include cortical thickening or thinning, blurring of the gray-white matter junction, increased signal intensities on FLAIR and/or T2-weighted images, a transmantle stripe of T2 hyperintensity, and localized brain atrophy [8]. However, 45% of histologically confirmed FCD lesions go undetected by routine visual inspection of the MRI [47], which may be in part due to the anatomical complexity of cortex. This makes FCD the most common histopathological finding in patients with no visible lesion on MRI [11, 12].

The feasibility of utilizing quantitative MRI methods for detecting visually apparent (i.e., MRI-positive) FCD lesions has been established using voxel-based morphometry [13–16]. Cortical surface-based methods have been combined in a multivariate approach with high accuracy in classifying small, visually subtle FCD lesions [17, 48]. Surface-based measures of cortical thickness, gray and white matter blurring, and sulcal depth contribute the most predictive weight in multivariate linear discriminant analyses, with cortical thickness offering the greatest specificity to the primary lesion [48]. This approach provides class II evidence that automated machine learning of MRI patterns can accurately identify FCD lesions that were radiologically diagnosed as MRI-negative, although these lesions were ultimately found to be visually apparent and manually traceable when texture-based maps were provided to expert reviewers.

Here we present a quantitative morphometry approach that combines surface-based MRI processing methods with machine learning algorithms to detect FCD lesions in patients classified as MRI-negative following conventional radiological analysis of scans acquired through a standard epilepsy protocol. The novelty of our approach is that it utilizes specific strategies to model the biological features of FCD lesions. For example we train separate classifiers on abnormally thick versus abnormally thin lesional regions to model these features separately, which can vary by FCD lesion subtype [8]. Additionally, we train separate classifiers for the gyral wall, sulcus, and crown to optimize detection of bottom-of-the-sulcus lesions [18].

2. Materials and Methods

A. Participants

Participants were selected from a large registry of patients with epilepsy treated at the New York University School of Medicine Comprehensive Epilepsy Center who signed consent for a research MRI scanning protocol. Criteria for inclusion in this study included: (1) completion of a high resolution T1-weighted MRI scan; (2) surgical resection to treat focal epilepsy; (3) diagnosis of FCD on neuropathological examination of the resected tissue. This selection criteria resulting in a sample of 31 patients with FCD. Demographic and seizure-related information for these participants is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and seizure-related information of both MRI positive and MRI negative patients.

| Patient | Location | Age (years) | Sex | Seizure Onset Age (years) | Seizure Frequency (per year) | Engel Class |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MRI-Positive Subjects

| ||||||

| NY49 | R Temporal | 39 | M | 20 | 6 | 1 |

| NY53 | L Frontal | 18 | F | 10 | 44 | 1 |

| NY123 | L Parietal | 14 | M | 7 | 730 | 2 |

| NY143 | R Frontal | 38 | F | 4 | 1248 | 1 |

| NY156 | L Temporal | 20 | M | 7 | 182 | 2 |

| NY187 | L Temporal | 45 | F | 5 | 14 | 1 |

| NY194 | R Temporal & R Occipital | 40 | F | 7 | 9 | 1 |

|

| ||||||

| Mean | 31 | 8.6 | 319 | |||

|

| ||||||

| MRI-Negative Subjects

| ||||||

| NY46 | R Temporal | 41 | M | 3 | 52 | 1 |

| NY51 | L Frontal & L Insular & L Temporal | 14 | F | 1 | 365 | 4 |

| NY67 | R Temporal | 27 | M | 13 | 1825 | 1 |

| NY68 | L Temporal | 26 | M | 15 | 12 | 2 |

| NY72 | R Temporal | 46 | M | 74 | 2 | 2 |

| NY98 | L Frontal & L Insular | 20 | M | 14 | 42 | 4 |

| NY116 | R Temporal | 30 | M | 22 | 84 | 1 |

| NY130 | L Temporal | 22 | M | 14 | 3 | 3 |

| NY148 | L Temporal | 37 | M | 35 | 3 | 2 |

| NY149 | R Frontal | 32 | F | 11 | 1460 | 1 |

| NY169 | R Temporal | 26 | M | 3 | 1277 | 1 |

| NY171 | R Temporal | 26 | F | 19 | 5 | 4 |

| NY177 | L Temporal | 38 | F | 19 | 5 | 3 |

| NY207 | R Temporal | 30 | F | 25 | 1 | 1 |

| NY212 | L Temporal | 37 | M | 21 | 166 | 1 |

| NY226 | R Temp | 40 | F | 5 | 8 | 1 |

| NY241 | L Temporal | 21 | M | 11 | 27 | 1 |

| NY255 | R Temporal | 20 | F | 15 | 48 | -* |

| NY259 | L Temporal | 26 | F | 9 | 288 | 2 |

| NY294 | R Temporal | 51 | F | 1 | 12 | 1 |

| NY297 | R Temporal | 51 | F | 8 | 52 | 1 |

| NY299 | R Temporal | 28 | F | 13 | 37 | 2 |

| NY312 | L Temporal | 43 | F | 6 | 24 | 1 |

| NY322 | R Frontal & R Insular & R Temporal | 24 | F | 9 | 12 | 1 |

|

| ||||||

| Mean | 31 | 15.3 | 242 | |||

M = male and F = female,

Patient lost during follow-up.

In addition, MRI scans using identical imaging parameters from a total of 62 neurotypical controls were acquired (31 females; ages 17–65; mean age = 33; SD = 12.5). Exclusion criteria for the control group included any history of psychiatric or neurological disorders.

B. Image Acquisition

Imaging for research

Imaging for the research protocol was performed at the New York University Center for Brain Imaging on a Siemens Allegra 3T scanner. Image acquisitions included a conventional 3-plane localizer and a T1-weighted volume pulse sequence (TE=3.25 ms, TR =2530 ms, TI =1100 ms, flip angle =7 deg field of view (FOV) = 256 mm, matrix = 256×256, vertex size =1×1×1.3 mm, scan time: 8:07 min). Acquisition parameters were optimized for increased gray/white matter image contrast. The T1-weighted image was reoriented into a common space, roughly similar to alignment based on the AC-PC line. Images were corrected for nonlinear warping caused by no-uniform fields created by the gradient coils.

Clinical imaging

Clinical imaging sequences for radiological review were acquired at the NYU Department of Radiology on a 3-Tesla Siemens scanner. Clinical sequences were variable across patients but commonly included a high-resolution T1-weighted MPRAGE (magnetization-prepared rapid gradient echo), T2-weighted images (axial and coronal, varying slice thickness from 1 to 3 mm), and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images (2–6 mm slice thickness). The research T1-weighted MPRAGE images used in our analyses were included in the set of images reviewed by the clinical radiology team. Conventional visual analysis of the clinical scans resulted in an MRI diagnosis of FCD in 7 patients (MRI-positive) and a “normal” report in 24 patients (MRI-negative). The higher number of MRI-negative patients in this sample may be due to a tendency for patients with more complex, MRI-negative epilepsy to be referred to our Level 4 epilepsy treatment center.

C. Surface Reconstruction

The research MRI sequences were processed using the FreeSurfer software package (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/), which performs automated tissue segmentation to recreate 3D representations of the cortical surfaces from structural MRI scans [19]. Briefly, after skull striping, the method [19] involves: (i) segmentation of the white matter, (ii) tessellation of the gray/white matter boundary, (iii) inflation of the folded surface, and (iv)correction of topological defects. Once the surface was reconstructed it was further refined by classifying all white matter vertices in the MRI volume to create the gray/white matter boundary. The gray/white matter junction was delineated up to submillimeter accuracy by further refining the white matter surface. After refining the gray/white matter junction the pial surface was located by deforming the surface outward. Each segmentation and reconstruction underwent manual inspection and editing, when necessary. However, the high image quality and gray-white contrast in the initial images resulted in minimal editing requirements for both patient and control scans. Surface reconstruction was followed by a registration process that involved morphing the reconstructed surface to an average spherical representation that accurately matched sulcal and gyral features across individual subjects while minimizing metric distortion [20].

D. Morphometric Feature Extraction

Five cortical features were computed at each vertex. These included: (i) cortical thickness; (ii) gray/white matter contrast; (iii) sulcal depth; (iv) mean curvature; and (v) Jacobian distortion.

Cortical thickness (CT): CT was assessed at each location by using an average of two measurements: (a) the shortest distance from the white matter surface to the pial surface; and (b) the shortest distance from the pial surface at each point to the white matter surface.

Gray/white matter contrast (GWC): was estimated by calculating the non-normalized T1 image intensity contrast at 0.5mm above and below the gray/white interface with trilinear interpolation of the images. The range of GWC values was [−1, 0], with values near zero indicating a higher degree of blurring of the gray/white boundary.

Sulcal depth: was estimated by calculating the dot product of the movement vectors with the surface normal [21], and results in the calculation of the depth/height of each point above the average surface. The values of sulcal depth lie in the range [−2, 2] with lower values indicating a location in the sulcus whereas higher values indicate a location on the gyral crown. We used the sulcal depth measure to stratify the classification into sulcus, wall and gyrus, because these areas differ in cortical thickness and gray-white contrast distribution [22], and there is evidence that FCD occurs predominantly in sulcal regions [9, 23].

Curvature: Curvature is measured as 1/r, where r is the radius of an inscribed circle and mean curvature represents the average of two principal curvatures with a unit of 1/mm [24]. Mean curvature quantifies the sharpness of cortical folding at the gyral crown or within the sulcus, and can be used to assess the folding of small secondary and tertiary folds in the cortical surface.

Jacobian distortion: In the registration process, as defined above, each subject’s gyral and sulcal features are aligned by warping the entire brain to a spherical average surface (i.e., the ‘standard brain’). During this process, each vertex is subjected to a nonlinear spherical transform. Jacobian distortion measures the magnitude of the nonlinear transform at each vertex needed to warp each vertex on the subject’s brain to a target vertex on the average surface. It is a measure of global brain deformation and has also been applied at the vertex-level in various neurological disorders [25].

E. Normalization of parameters

For preparing the data for the machine learning classifier, the cortical features from each patient are z-score normalized using the mean and standard deviation calculated from the control population, on a vertex-by-vertex basis.

F. Lesion and resection tracing

For MRI-positive patients, an expert board-certified in neurology and neurophysiology (RK) reviewed the clinical MRI report and manually traced the outer regions of the visible lesions on the morphometric T1-weighted 3D volume scan based on the lesional areas identified in the initial clinical report. When available, the visual detection was aided by T2 FLAIR images from the standard clinical epilepsy MRI protocol. For MRI-negative patients, the post-operative T1-weighted image (with the resection area removed) was rigid-body coregistered to the (intact) pre-operative T1-weighted image using FLIRT [26]. The brain resection area was manually traced on the post-surgical MRI scan by a trained technician blinded to patient diagnosis and reviewed by a board-certified neurologist. For both lesion and resection tracings, the manual masks in vertex-space were subsequently projected onto the cortical surface by assigning each vertex to the nearest surface vertex. Because the surface has sub-vertex resolution, a morphological closing operation was used to fill in any unlabeled vertices.

G. Univariate (z-score) analysis

In order to compare the machine learning approach to a univariate approach that uses surface based morphometry [10], a Z-score statistic was calculated for cortical thickness which was found to be the most informative feature in Thesen et al. [10], at each vertex between a single patient and the control group. Cluster-thresholding at p<.05 was applied to correct for multiple comparison [27]. Images were thresholded at z = 2.1 (p= .035) [10].

H. Machine learning classification

Machine learning algorithms are ideally suited for dysplasia detection, in that they can incorporate multiple quantitative MRI measures, making maximum use of all relevant data available. The goal of the machine learning classification model was to accurately differentiate contiguous clusters of lesional vertices from non-lesional vertices in a single patient. Accuracy was defined by classifying contiguous vertices as “lesional” when they fell within the manually traced lesion or resection region for MRI-positive and MRI-negative patients, respectively, and “non-lesional” when they fall outside of these regions.

Designing an appropriate classification scheme for detecting FCD under these constraints has three important challenges. First, class label noise arises from subjectivity in delineating the lesion zone (either a manually-traced MRI-visible zone or resection-defined zone). Second, the anatomic complexity and heterogeneity in folded cortical tissue reduces the ability to discern lesional tissue from normal cortex, which is one of the reasons why a large number of lesions remain elusive to human perception in routine radiological evaluation [28]. Third, class imbalance [29] results from a ratio of substantially fewer lesional to non-lesional vertices for a particular patient. The class imbalance problem is further compounded by the higher availability of healthy control data as compared to patient data. We address each of these challenges in turn.

Addressing class label noise

Optimizing classifiers for detecting FCD lesions relies on accurately labeling vertices as “lesional” or “non-lesional” in the training data. Class label noise can arise from errors in human decision-making and subjectivity, in addition to the anatomical complexity of the brain itself. For example, labeling “lesional” vertices in MRI-positive cases involves subjective tracing of the FCD lesion. Moreover, in the absence of a MRI-visible lesion, lesional vertices are delineated by the extent of the tissue removed in surgery, which may include a gradation from abnormal to normal tissue. From a supervised machine learning perspective, treating all the resected vertices in the case of MRI-negative patients as being lesional introduces substantial false positives into the training data, which can have adverse effects on classifier accuracy [30].

The fact that the resection zones in MRI-negative patients include both lesional and non-lesional tissue is problematic for training classifiers. Hong et al., [48] address this problem by utilizing a pre-processing step that includes the generation of texture maps [53, 54] and also requires human expertise and intervention to visually identify and trace lesions. In our approach we used cortical thickness to reduce the impact of false-positive label noise. Cortical thickness is the most prominent feature on T1-weighted imaging in FCD [8, 10, 49]. We therefore, trained the classifier on the vertices inside the resection zone that showed the highest degree of thickness abnormality, both in terms of thickening and thinning.

Normal tissue classification was performed on data from control subjects in order to control false negatives in the labeled data that can arise because the lifetime seizure burden of a given patient can lead to cortical abnormalities outside the seizure onset zone [43, 50–52] or the possibility of additional non-epileptogenic dysplastic lesions [42]. In addition, patients who are suffering from epilepsy due to developmental factors may have additional lesions that are either not epileptogenic or have latent epileptogenicity. Based on these considerations, we chose not to include non-lesional vertices from the subjects as negative instances in our training data.

Reducing cortical complexity

Anatomical complexity of the cortical convolution may account for why many lesions remain undetected in radiological MRI evaluations. The folding of the cortex varies across individuals and it can hinder the visibility of subtle FCD lesions that may be hidden deep within the folds. Recent studies have shown that subtle FCD lesions occur with higher frequency at the bottom of the sulcus [23]. Given these observations, we designed a stratified classification scheme composed of different classifiers that were trained separately for sulcal, wall, and gyral regions. We separated the data into three non-overlapping levels where: (i) sulcal depth in the range [−2, −1] represents vertices that are part of the sulcus, (ii) [1, 2] represents vertices residing on the gyrus and, (iii) the vertices in-between (i.e., with a sulci depth of [−1, 1]) were labeled as wall vertices. Partitioning the vertices into these three groups meant that we needed to calculate the two thresholds for mitigating label noise per sulci-level, which resulted in a total of six distinct thresholds (i.e., 1. thin/sulcus, 2. thick/sulcus, 3. thin/gyrus, 4. thick/gyrus, 5. thin/wall, 6. thick/wall). In other words, for each sulcus level X, we trained two separate classifiers, which differed in how the training data for lesional vertices was collected. Specifically, one classifier was based on vertices of sulcal depth X and thinning values less than our threshold “τ-thin”, whereas the other classifier was based on vertices of sulcal depth X with cortical thickening greater than our threshold “τ-thick”. Note that although we used cortical thickness to reduce the lesion area, our classifiers employed all four cortical metrics to represent each vertex (i.e., cortical thickness, GWC, cortical curvature and Jacobian distortion).

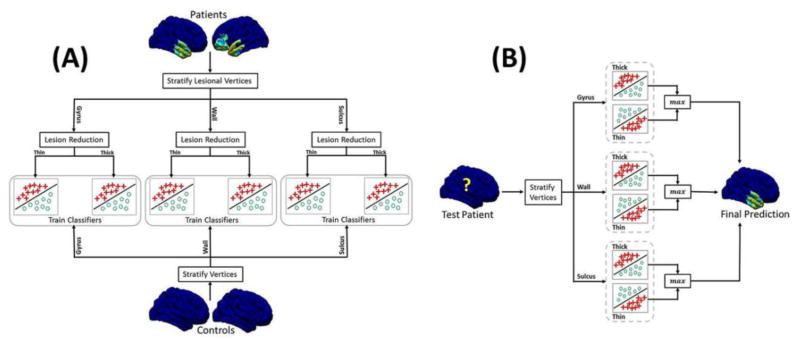

Addressing class imbalance

This problem arises out of having substantially fewer vertices labeled as “lesional” than vertices labeled as “non-lesional.” Such an imbalance in training data can result in classifiers that are biased towards the majority class [29]. To address this issue, we used a “bagging” approach [31]. We construct a set of “base-level” classifiers, each trained using logistic regression, using iterative-reweighted least squares (IRLS) algorithm [32]. Each base-level classifier is trained on all of the minority class instances (lesional vertices) and an equal-sized random sample of majority class instances (non-lesional instances). A “bag” of ten “base-level” classifiers was trained for each of the resulting six subsets of vertices. To classify a vertex as lesional or non-lesional, we first used its sulcal depth to choose the two correct bags of classifiers (e.g., if the sulcal depth was “sulcus” we use the “thin/sulcus” and “thick/sulcus” classifiers). Next, each of the ten base-level classifiers was applied for each bag. The final classification was obtained by a majority vote of their predictions. The overall training and testing phases of the proposed classification scheme are shown in Figure 1A and 1B, respectively.

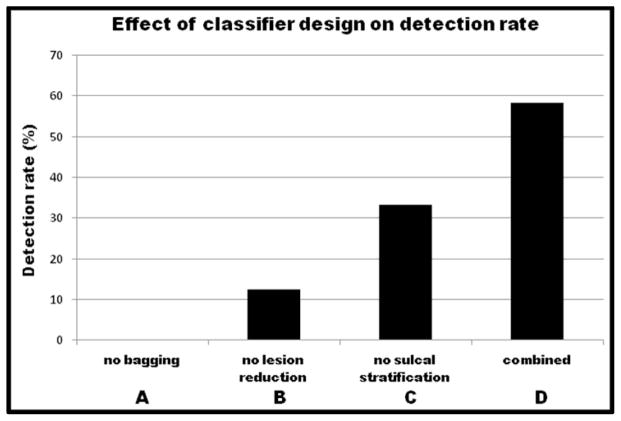

Figure 1.

Different steps involved in the (A) training and (B) test phase of the proposed classification scheme. Note that the lesion reduction step is applied only to the training patients. For a test subject we calculate two labels per vertex: one from each thick/thin classifier. The final label of the vertex is calculated as the maximum of both predicted labels.

I. Experimental Method

A leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV) strategy was used to test the performance of the classifier on unseen data. In each run we left out a single subject from the data and trained a classifier on vertices belonging to all the remaining subjects and the controls. The output of each logistic regression classifier within the bag is the probability that the given input vertex belongs to the positive (lesional) class. To convert this probability into a class label, we defined a threshold ρ = 0.95 for the output values such that the vertices that have a predicted probability above ρ were deemed lesional and those that fall below ρ were considered normal. After classifying each vertex of the test subject, the results were post-processed [10] to remove spurious detections by defining the detected cluster as a set of contiguous lesional vertices having a surface area greater than or equal to 50 mm2, an approach similar to [33], where the threshold was determined as the area of the largest cluster detected by the classifier in the control population.

To determine detection values, patients were regarded as true positives if any of the remaining clusters partially or completely overlapped with the lesion/resection area. Outside clusters were considered false positives. It should be kept in mind that the resulting detection outside the lesion/resection zone may actually represent other malformations in the cortex that have either escaped visual inspection or were not part of the seizure-onset zone. Thus, the statistics provided here represent a lower bound on actual classifier performance. Performance evaluation metrics: We use three metrics to quantify and contrast the performance of our classification scheme with the baseline univariate approach. These include the true positive rate (TPR), the false positive rate (FPR) and the Dice Coefficient (DC) [34]. DC is a set similarity metric that is a special case of the kappa statistic [35]. It is commonly used to measure the accuracy of segmentation in medical images when ground truth is available [36, 37]. We use DC to measure the overlap between the final detected clusters (after post-processing) with the resection or expert-traced lesion for a test patient.

Let, the resection/lesion zone be represented by a binary vector Mlabel ∈ {0,1}, and let Mpred ∈ {0,1} be the binary vector representing the detection results. The metrics are then defined as:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

where, |M| represents the first norm of the binary vector, and in our case translates to the number of vertices marked as lesional and M̄ represents an inverted mask, such that the original 0 values are replaced with 1, and vice versa.

3. RESULTS

In this section we review the performance of our proposed classification scheme and contrast it with the baseline z-score based method. We also provide empirical evidence to support our design decisions i.e., classifier stratification, mask reduction and bagging.

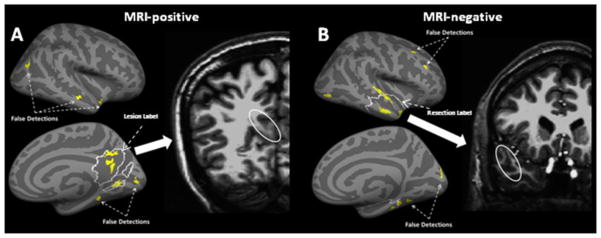

Overview of the detection results

For MRI-positive patients, both the z-score and machine learning approaches were found to perform identically, and accurately detected lesions in 6 out of 7 patients, yielding an 86% detection rate (Table 2). Machine learning correctly identified a significantly larger proportion (t(7)=3.3, p<0.05) of the lesional area (mean=20.14%) compared to the z-score approach (mean=16.03%) as quantified by the TPR. However, the differences in the DC values were found to be not statistically significant. The false positive rate was significantly lower for the z-score approach (mean=1.4%) compared to the machine learning approach (mean=2.4%; (t(7)= 5.1, p<.01) (see Table 2). Figure 2A shows an example of a detected lesion in an MRI-positive patient. Detailed results for both approaches are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Detection results for both MRI-positive and MRI-negative subjects. For each subject the true-positive rate (TPR) and false-positive rate (FPR) are calculated as the percentage of lesional vertices correctly labeled, and the percentage of non-lesional vertices incorrectly labeled, respectively. The dice coefficient (DC) is also shown as a percentage to quantify the overlap between the detected clusters and the resection on the cortical surface.

| Subject Id | Z-Score | ML | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPR | FPR | DC | TPR | FPR | DC | |||||

|

MRI-Positive

| ||||||||||

| NY49 | 11.85 | 1.00 | 19.92 | 24.76 | 2.27 | 34.58 | ||||

| NY53 | 20.28 | 2.60 | 29.60 | 27.72 | 4.46 | 35.42 | ||||

| NY123 | 29.80 | 3.68 | 27.61 | 31.33 | 4.50 | 26.36 | ||||

| NY143 | 16.38 | 0.60 | 12.28 | 20.03 | 2.00 | 5.81 | ||||

| NY156 | 26.12 | 1.20 | 38.69 | 25.65 | 2.11 | 36.14 | ||||

| NY187 | - | 0.50 | - | - | 0.90 | - | ||||

| NY194 | 7.79 | 0.14 | 14.00 | 11.48 | 0.58 | 18.18 | ||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Mean | 16.03 | 1.40 | 20.30 | 20.14 | 2.41 | 22.36 | ||||

|

| ||||||||||

|

MRI-Negative

| ||||||||||

| NY46 | - | 0.34 | - | 0.95 | 0.74 | 1.78 | ||||

| NY51 | 2.86 | 1.00 | 5.11 | 4.15 | 1.02 | 7.24 | ||||

| NY67 | 4.35 | 0.26 | 8.13 | 8.30 | 0.65 | 14.45 | ||||

| NY68 | 0.09 | 1.33 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 1.69 | 0.15 | ||||

| NY72 | - | - | - | 0.55 | 0.25 | 1.07 | ||||

| NY98 | - | 0.33 | - | - | 0.81 | - | ||||

| NY116 | - | - | - | - | 0.39 | - | ||||

| NY130 | - | 0.16 | - | - | 0.25 | - | ||||

| NY148 | - | 0.10 | - | - | 0.12 | - | ||||

| NY149 | - | 0.84 | - | - | 1.68 | - | ||||

| NY169 | - | 1.02 | - | 9.41 | 1.98 | 8.97 | ||||

| NY171 | 2.45 | 1.00 | 2.93 | 2.94 | 1.80 | 2.57 | ||||

| NY177 | 1.88 | 0.14 | 3.59 | 3.20 | 0.32 | 5.80 | ||||

| NY207 | - | 0.05 | - | - | 0.60 | - | ||||

| NY212 | - | 1.01 | - | - | 1.60 | - | ||||

| NY226 | - | 0.50 | - | 1.09 | 0.60 | 1.88 | ||||

| NY241 | - | 0.33 | - | - | 0.40 | - | ||||

| NY255 | 3.23 | 0.42 | 6.01 | 6.18 | 1.30 | 10.30 | ||||

| NY259 | - | 0.50 | - | - | 0.58 | - | ||||

| NY294 | - | 0.50 | - | - | 1.40 | - | ||||

| NY297 | 2.98 | 0.14 | 5.64 | 7.98 | 0.56 | 13.30 | ||||

| NY299 | - | 3.13 | - | 3.30 | 4.86 | 4.32 | ||||

| NY312 | 6.10 | 0.50 | 10.05 | 9.04 | 0.97 | 12.83 | ||||

| NY322 | 1.74 | 0.31 | 3.25 | 2.02 | 0.49 | 3.66 | ||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Mean | 1.07 | 0.58 | 1.87 | 2.47 | 1.04 | 3.68 | ||||

Figure 2.

Detection results for the ML based approach for (A) an MRI-positive and (B) an MRI-negative patient. The inflated lateral and medial cortical surfaces show the original expert-traced lesion (A) or the resection zone (B) as the regions outlined by the white solid curve. The significant lesional clusters discovered by the ML are shown in yellow. The MRI slice on the right shows the abnormal area corresponding to the clusters discovered inside the lesion/resection on the actual brain volume.

For patients with MRI-negative lesions, the machine learning approach significantly outperformed the z-score based method. The z-score based method correctly detected lesions in 9 out of the 24 patients (37%), whereas the machine learning approach correctly detected clusters inside the resection zone for 14 patients (58%) (see Table 2). Figure 2B shows an example of a detected lesion in an MRI-negative subject. The overall true-positive rate was significantly higher (t(23) = 3.04, p<0.01) in the machine learning approach (mean = 2.5 %) compared to the z-score approach (mean = 1.1%). The DC values for the machine learning approach (mean = 3.68%) were also significantly superior (t(23) = 3.04, p<0.01) to the baseline (mean = 1.87%). However, the false positive rate was also significantly higher (t(23) = 5.65, p<.001) in the machine learning approach (mean = 1.0%) compared to the z-score approach (0.6%). Detailed results are shown in Table 2.

Sensitivity Analysis of Design Decisions

In order to determine whether correcting for cortical complexity by stratifying classifiers by sulcal depth results in improved detection rates, we re-ran the training phase in the leave-one-patient-out cross-validation without this correction (note that we retain bagging and mask reduction). As depicted in Tables 3 and 4 (compare the ML column to column “A”), the true positive rate dropped from 20.1% to 12.9%, in the MRI-positive group, and lesion detection dropped from 58% to 33% in the MRI-negative group. This suggests that different feature combinations might be more prevalent in specific regions (e.g., sulcus, gyrus, wall), which is consistent with the observation of region-specific dysplasia subtypes (e.g., bottom-of-the-sulcus dysplasia) [23].

Table 3.

A comparison of detection results using the z-score based method and the ML methods only for MRI-positive subjects with different variations in the design of the ML approach. (A) no stratification along the sulcal values, (B) stratifies the data based on the sulcal depth values, but does not reduce the lesion mask. (C) uses stratification, lesion reduction by calculating a threshold for each sulcal level using cortical thickness values, but it does not use bagging. (The TPR and FPR are measured as a percentage.)

| Patient | z-Score | ML | (A) | (B) | (C) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPR | FPR | TPR | FPR | TPR | FPR | TPR | FPR | TPR | FPR | |

| NY49 | 11.8 | 1.0 | 24.8 | 2.3 | 8.7 | 0.6 | - | - | 0.6 | - |

| NY53 | 20.3 | 2.6 | 27.7 | 4.5 | 23.5 | 4.2 | 10.6 | 1.2 | 4.3 | 0.2 |

| NY123 | 29.8 | 3.7 | 31.3 | 4.5 | 31.4 | 4.6 | 25.2 | 1.2 | 7.4 | 0.1 |

| NY143 | 16.4 | 0.6 | 20.0 | 2.0 | - | 0.4 | - | - | - | 0.1 |

| NY156 | 26.1 | 1.2 | 25.7 | 2.1 | 26.4 | 1.8 | 20.1 | 0.4 | 2.1 | - |

| NY187 | - | 0.5 | - | 0.9 | - | 0.6 | - | 0.4 | - | - |

| NY194 | 7.8 | 0.1 | 11.5 | 0.6 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

|

| ||||||||||

| Mean (%) | 16.0 | 1.4 | 20.1 | 2.4 | 12.9 | 1.7 | 8.0 | 0.5 | 2.1 | 0.1 |

Table 4.

A comparison of detection results using the z-score based method and the ML method only for MRI-negative subjects with different variations in the design of the ML approach. (A) no stratification along the sulcal values, (B) stratifies the data based on the sulcal depth values, but does not reduce the lesion mask. (C) uses stratification, lesion reduction by calculating a threshold for each sulcal level using cortical thickness values, but it does not use bagging. (FPR is given as a percentage.)

| Patient | z-Score | ML | (A) | (B) | (C) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Detected | FPR | Detected | FPR | Detected | FPR | Detected | FPR | Detected | FPR | |

| NY46 | n | 0.34 | y | 0.74 | n | - | n | - | n | - |

| NY51 | y | 1.00 | y | 1.02 | y | 0.95 | y | 0.30 | n | - |

| NY67 | y | 0.30 | y | 0.65 | y | 0.19 | n | - | n | - |

| NY68 | y | 1.33 | y | 1.69 | y | 1.56 | y | 0.81 | n | - |

| NY72 | n | - | y | 0.25 | n | - | n | - | n | - |

| NY98 | n | 0.33 | n | 0.81 | n | 0.56 | n | - | n | - |

| NY116 | n | - | n | 0.39 | n | - | n | - | n | - |

| NY130 | n | 0.16 | n | 0.25 | n | 0.16 | n | - | n | - |

| NY148 | n | 0.10 | n | 0.12 | n | 0.10 | n | - | n | - |

| NY149 | n | 0.84 | n | 1.68 | n | 0.18 | n | - | n | 0.06 |

| NY169 | n | 1.02 | y | 1.98 | n | 0.09 | n | - | n | - |

| NY171 | y | 1.00 | y | 1.80 | y | - | n | - | n | - |

| NY177 | y | 0.14 | y | 0.32 | y | 0.30 | n | - | n | - |

| NY207 | n | 0.05 | n | 0.60 | n | - | n | - | n | - |

| NY212 | n | 1.01 | n | 1.60 | n | 1.13 | n | 0.53 | n | 0.06 |

| NY226 | n | 0.50 | y | 0.60 | n | 0.46 | n | 0.20 | n | - |

| NY241 | n | 0.33 | n | 0.40 | n | 0.35 | n | 0.08 | n | - |

| NY255 | y | 0.42 | y | 1.30 | y | 0.08 | n | - | n | - |

| NY259 | n | 0.50 | n | 0.58 | n | 0.50 | n | 0.17 | n | - |

| NY294 | n | 0.50 | n | 1.40 | n | 0.20 | n | - | n | - |

| NY297 | y | 0.14 | y | 0.56 | y | - | n | - | n | - |

| NY299 | n | 3.13 | y | 4.86 | n | 0.30 | n | - | n | - |

| NY312 | y | 0.50 | y | 0.97 | y | 0.73 | y | - | n | - |

| NY322 | y | 0.31 | y | 0.49 | y | 0.12 | n | - | n | - |

|

| ||||||||||

| Mean (%) | 9/24 (38%) | 0.58 | 14/24 (58%) | 1.04 | 8/24 (33%) | 0.33 | 3/24 (12%) | 0.09 | 0/24 (0%) | 0.005 |

In order to correct for the class label noise problem, we employed a strategy to reduce vertices labeled as “lesional” to those that were significantly thicker or thinner than “non-lesional” vertices. We tested the improvement in detection rates when utilizing this strategy by re-running our analysis without mask reduction (note that we retain stratification and bagging for this experiment). The results are again depicted in Tables 3 and 4 (compare the ML column to column “B”) and show a drop in detection rates for both the MRI-positive group (from 6/7 to 3/7) and the MRI-negative group (from 14/24 to 3/24 detections). This indicates that class label noise is a significant issue for both groups that can be corrected by utilizing a mask reduction strategy with a separate threshold for cortical thickening and cortical thinning.

Our last experiments examined the impact of bagging on the results (we eliminated bagging and retained stratification and mask reduction). We see from Tables 3 and 4 that eliminating bagging resulted in the most substantial drop in performance; the TPR of MRI-positive group dropped from 20.1% to 2.1% and for the MRI-negative group the detection rate dropped from 14/24 to 0/24. In other words, failing to correct for the class imbalance problem resulted in zero detection of MRI-negative FCD lesions. This strongly supports the use of such bagging and stratified classifiers in future machine learning models for FCD detection. Figure 3 summarizes our results and contrasts the rate of detection for MRI-negative patients under different variations in the design of the machine learning approach.

Figure 3.

A comparison of detection results in MRI-negative subjects with different variations in the design of the ML approach, including (A) without bagging (c.f. section H-3), but with sulcal stratification and lesion reduction, (B) without lesion reduction (c.f. section H-1) but with bagging and sulcal stratification, (C) without stratification (c.f. section H-2) but with bagging and lesion reduction, and (D) using all including bagging, lesion reduction and sulcal stratification.

4. DISCUSSION

Our results demonstrate that surface-based morphometry, coupled with a multivariate classification scheme that is adapted for FCD lesion data, can successfully detect epileptogenic FCD lesions on MRIs that were previously interpreted as normal by neuroradiologists. This approach correctly identified epileptogenic regions in 58% of MRI-negative patients compared to 37% when using univariate statistics. A separate analysis showed that while the best detectors of FCD lesions were cortical thickness and GWC, features commonly used in the visual diagnosis of FCD, measures of cortical complexity, such as curvature and Jacobian distortion also contributed strongly to lesion detection. This finding suggests that MRI images contain ample information about focal epileptogenic lesions, but do so to a degree and in a complexity that may not be appreciable by visual inspection alone.

Malformations of cortical development are the third most frequent disease entity associated with TRE and FCD is the underlying pathology in 75% of these cases [38]. Resection of FCD tissue is critical to seizure control; therefore, it is an important target for MRI evaluation during pre-surgical assessment. The pre-surgical detection of a lesion informs intracranial electrode placement and provides a valuable target that, when surgically resected, can lead to a substantial improvement in post-surgical outcome [39, 40]. Indeed, surgical success in patients with neocortical epilepsy and a concordant MRI lesion is drastically improved (66%) compared tonon-lesional cases (29%) [41].

The application of machine learning algorithms to the detection of FCD lesions resulted in a unique set of challenges that are specific to this clinical population, requiring innovative solutions. The existence of these challenges and the improvement in classification when solutions were implemented offer a unique perspective on the biological complexity of focal cortical dysplasia. One such challenge was the presence of abnormal vertices outside of the histopathologically confirmed focal dysplastic region. Although these are considered to be statistical false positives, alternative explanations must also be considered, such as: (1) the presence of dysplastic cortex outside of the seizure onset zone that may or may not have latent epileptogenic potential [42]; and/or (2) the burden of intractable seizures on brain structure could result in subtle abnormalities (e.g., atrophy, gliosis) that may be difficult to distinguish from developmental aberrations [43, 44, 50–52]. Both of these possibilities could impact post-surgical outcomes and are thus worth further exploration. For example, magnetoencephalography or intracranial electroencephalography could be used to determine whether there is abnormal electrophysiology in these “false positive” regions. Tracking post-surgical outcomes could determine whether a greater extent of “extralesional” abnormalities is associated with suboptimal post-surgical seizure control or functional outcomes.

An additional challenge for machine learning algorithms is the heterogeneity of pathological and MRI features in FCD. For example, FCD lesions might contain small diameter cells that may result in abnormally thin cortex on MRI [45] or large dysmorphic cells that may result in abnormally thick cortex on MRI [8]. We observed improved classification rates when we stratified labeling of “lesion” vertices in the lesion zone/resection zone based on separate thresholds for cortical thickening and thinning. Additionally, specific regions of the cortical architecture may be more vulnerable to dysplastic pathology. FCD lesions occur with higher frequency at the bottom of the sulcus, potentially reflecting different “micromechanic” tensions that enhance pathophysiological vulnerability in the sulcal bottom [9, 23]. We observed improvement when we stratified classifiers trained separately for sulcal, wall, and gyral regions. The improvement in our model after implementing such solutions suggests that similar stratification strategies should be employed in future FCD lesion detection efforts.

The resection zones of MRI-negative patients include both lesional and non-lesional tissue, therefore, the resection zone cannot be treated as a gold-standard for training classifiers. Hong et al., [48] utilize a mask reduction step in which texture maps [53, 54] are used to manually trace the lesion for MRI-negative patients that have type-II FCD. This pre-processing entails the generation of texture maps and also requires specific human expertise to identify lesions. In the proposed approach we use cortical measures to reduce the resection mask, such that the resected regions that are not significantly different from the regions outside the resection zone are not used for training the classifier. We hypothesize that this approach will accurately classify FCD lesions in a sample of patients with verified MRI-negative FCD lesions.

The methodological approach used in the current study to improve lesion detection of MRI-negative images has a number of significant advantages. First, it works with most existing scanners and sequences, and does not require advanced imaging technologies. Second, as we learn more about FCD, stratification of larger datasets into distinct FCD subtypes [46] can be incorporated into future training sets to help the system learn specific subtype features, and potentially classify FCD by subtype. Third, such a method can be fully automated and thus, with minimal effort, can augment visual inspection by yielding targets for closer evaluation by neuroradiologists. This latter point is important, given the fact that the visual detection of FCD on MRI varies widely among raters, and is highly dependent on the experience of the evaluator.

Limitations

In the current study, training data in MRI-negative cases were derived from resection areas that were defined by intracranial electrophysiology. FCD pathology was present in the resection area in all patients; however, non-lesional tissue may have also been resected. We reduced this problem by applying a mask reduction step and this increased performance. In future research studies, this step can be improved by accurately co-registering the pathological sample with the MRI, allowing the matching of pathological and MRI slice.

In addition, our sample of MRI-negative patients was disproportionately higher than MRI-positive patients, which may not reflect the proportions seen at other neurological clinics. This likely represents a bias in patient referrals to our Level 4 epilepsy center, which offers intensive neurodiagnostic monitoring for patients with treatment resistant epilepsy that is difficult to localize. Our results offer a potential advancement of neurodiagnostic tools for this more challenging population. However, the case-control methods we utilize in our approach require a large normal control MRI data set with identical scanning parameters as those of the patient and thus cannot be readily applied in any clinical center. Further investigations with combined data sets from different scanners and institutions are needed to create methods for making these analyses feasible with different scanning sequences across centers. Finally, automated detection and classification of lesions should not replace careful visual analysis of a trained expert. Rather, the quantitative approach can be used to supplement visual analysis by highlighting areas with a high lesional probability. These results should always be interpreted in the context of all available patient information collected during pre-surgical evaluation.

Conclusion

In summary, we have demonstrated that a quantitative morphometric method using surface-based brain modeling, combined with machine learning algorithms and novel strategies to deal with the complexity of cortical malformations, results in improved detection of FCD. Improved detection of neocortical structural lesions is likely to increase the number of patient referrals to specialized tertiary epilepsy centers for surgical consideration, and in many cases, may decrease the delay between initial diagnosis and surgery. This has significant implications for improved seizure and cognitive outcomes in patients with FCD and concomitant epilepsy.

Highlights.

We develop a classification scheme to identify structural lesions in FCD.

We use surface based morphometry to model the cortex.

Detection tested on both MRI-negative and positive patients.

We achieve higher detection rate (58%) for MRI-negative patients.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank John Brumm, Omar Khan and Christine Chao for help with data processing, and Rachel Jurd for comments. This research is supported by FACES-Finding a Cure for Epilepsy & Seizures (T. T.) and the Epilepsy Foundation (K. E. B., B.A. and C. C.).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kwan P, Brodie MJ. Early identification of refractory epilepsy. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(5):314–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200002033420503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strzelczyk A, Reese JP, Dodel R, et al. Cost of epilepsy: a systematic review. Pharmacoeconomics. 2008;26(6):463–76. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200826060-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tellez-Zenteno JF, Dhar R, Wiebe S. Long-term seizure outcomes following epilepsy surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain. 2005;128(Pt 5):1188–98. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benbadis SR, Heriaud L, Tatum WO, et al. Epilepsy surgery, delays and referral patterns-Are all your epilepsy patients controlled? Seizure. 2003;12(3):167–70. doi: 10.1016/s1059-1311(02)00320-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hakimi AS, Spanaki MV, Schuh LA, et al. A survey of neurologists’ views on epilepsy surgery and medically refractory epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2008;13(1):96–101. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuzniecky RI, Barkovich AJ. Malformations of cortical development and epilepsy. Brain & Development. 2001;23(1):2–11. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(00)00195-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lerner JT, Salamon N, Hauptman JS, et al. Assessment and surgical outcomes for mild type I and severe type II cortical dysplasia: a critical review and the UCLA experience. Epilepsia. 2009;50(6):1310–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01998.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muhlebner AR, Kobow CK, Feucht M, et al. Neuropathologic measurements in focal cortical dysplasias: validation of the ILAE 2011 classification system and diagnostic implications for MRI. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;123(2):259–72. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0920-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Besson P, Andermann F, Dubeau F, et al. Small focal cortical dysplasia lesions are located at the bottom of a deep sulcus. Brain. 2008;131(Pt 12):3246–55. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thesen T, Quinn BT, Carlson C, et al. Detection of epileptogenic cortical malformations with surface-based MRI morphometry. PLoS One. 2011;6(2):e16430. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alarcon G, Valentin G, Watt C, et al. Is it worth pursuing surgery for epilepsy in patients with normal neuroimaging? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77(4):474–80. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.077289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wetjen NM, Marsh WR, Meyer FB, et al. Intracranial electroencephalography seizure onset patterns and surgical outcomes in nonlesional extratemporal epilepsy. J Neurosurg. 2009;110(6):1147–52. doi: 10.3171/2008.8.JNS17643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kassubek J, Huppertz HJ, Spreer J, et al. Detection and localization of focal cortical dysplasia by vertex-based 3-D MRI analysis. Epilepsia. 2002;43(6):596–602. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2002.41401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Colliot O, Bernasconi N, Khalili N, et al. Individual vertex-based analysis of gray matter in focal cortical dysplasia. Neuroimage. 2006;29(1):162–71. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bonilha L, Montenegro MA, Rorden C, et al. Vertex-based morphometry reveals excess gray matter concentration in patients with focal cortical dysplasia. Epilepsia. 2006;47(5):908–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pail M, Mareček R, Hermanová M, et al. The role of voxel-based morphometry in the detection of cortical dysplasia within the temporal pole in patients with intractable mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2012;53(6):1004–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2012.03456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Besson P, Bernasconi N, Colliot O, Evans A, Bernasconi A. Surface-based texture and morphological analysis detects subtle cortical dysplasia. Med Image Comput Comput Assist Interv. 2008;11(Pt 1):645–52. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-85988-8_77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hofman PA, Fitt GJ, Harvey AS, et al. Bottom-of-sulcus dysplasia: imaging features. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196(4):881–5. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.4423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dale AM, Fischl B, Sereno MI. Cortical surface-based analysis. I. Segmentation and surface reconstruction. Neuroimage. 1999;9(2):179–94. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1998.0395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fischl B, Dale AM. Measuring the thickness of the human cerebral cortex from magnetic resonance images. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(20):11050–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.200033797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fischl B, Sereno MI, Dale AM. Cortical surface-based analysis. II: Inflation, flattening, and a surface-based coordinate system. Neuroimage. 1999;9(2):195–207. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1998.0396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blackmon K, Halgren E, Barr WB, et al. Individual differences in verbal abilities associated with regional blurring of the left gray and white matter boundary. J Neurosci. 2011;31(43):15257–63. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3039-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hofman PA, Fitt GJ, Harvey AS, et al. Bottom-of-sulcus dysplasia: imaging features. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196(4):881–5. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.4423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pienaar R, Fischl B, Caviness B, et al. A Methodology for Analyzing Curvature in the Developing Brain from Preterm to Adult. Int J Imaging Syst Technol. 2008;18(1):42–68. doi: 10.1002/ima.v18:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Good CD, Ashburner J, Frackowiak RS. Computational neuroanatomy: new perspectives for neuroradiology. Rev Neurol. 2001;157(8–9 Pt1):797–806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jenkinson M, Bannister PR, Brady JM, et al. Improved optimisation for the robust and accurate linear registration and motion correction of brain images. Neuroimage. 2002;17(2):825–41. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(02)91132-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hagler DJ, Jr, Saygin AP, Sereno MI. Smoothing and cluster thresholding for cortical surface-based group analysis of fMRI data. Neuroimage. 2006;33(4):1093–103. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.07.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tassi L, Colombo N, Garbelli R, et al. Focal cortical dysplasia: neuropathological subtypes, EEG, neuroimaging and surgical outcome. Brain. 2002;125(8):1719–32. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Japkowicz N, Stephen S. The class imbalance problem: A systematic study. Intell Data Anal. 2002;6(5):429–49. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brodley CE, Friedl M. Identifying mislabeled training data. J AI Res. 1999;11:131–67. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wallace BC, Small K, Brodley CE, et al. Class imbalance, redux. Proc IEEE Int Conf Data Mining. 2011:754–63. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bishop CM. Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Antel SB, Collins DL, Bernasconi N, et al. Automated detection of focal cortical dysplasia lesions using computational models of their MRI characteristics and texture analysis. Neuroimage. 2003;19(4):1748–59. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00226-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dice LR. Measures of the amount of ecologic association between species. Ecology. 1945;26(3):297–302. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zijdenbos AP, Dawant BM, Margolin RA, Palmer AC. Morphometric analysis of white matter lesions in MR images: method and validation. IEEE Tran Med Imag. 1994;13(4):716–724. doi: 10.1109/42.363096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zou KH, et al. Statistical validation of image segmentation quality based on a spatial overlap index. Acad Rad. 2004;11(2):178–189. doi: 10.1016/S1076-6332(03)00671-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Babalola KO, et al. Comparison and Evaluation of Segmentation Techniques for Subcortical Structures Brain MRI. Med Image Comput Comput Assist Interv. 2008;11(Pt 1):409–416. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-85988-8_49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blumcke I, Spreafico Cause matters: A neuropathological challenge to human epilepsies. Brain Pathol. 2012;22:347–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2012.00584.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sisodiya SM. Surgery for malformations of cortical development causing epilepsy. Brain. 2000;123(6):1075–91. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.6.1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sisodiya SM. Surgery for focal cortical dysplasia. Brain. 2004;127(11):2383–4. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bell ML, Rao S, So EL, et al. Epilepsy surgery outcomes in temporal lobe epilepsy with a normal MRI. Epilepsia. 2009;50(9):2053–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02079.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fauser S, Sisodiya SM, Martinian L, et al. Multi-focal occurrence of cortical dysplasia in epilepsy patients. Brain. 2009;132:2079–90. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McDonald CR, Hagler DJ, Jr, Ahmadi ME, et al. Regional neocortical thinning in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2008;49:794–803. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Garbelli R, Milesi G, Medici V, et al. Blurring in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy: clinical, high-field imaging and ultrastructural study. Brain. 2012;135:2337–2349. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Casanova MF, El-Baz AS, Kamat SS, et al. Focal cortical dysplasias in autism spectrum disorders. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2013;1(1):67. doi: 10.1186/2051-5960-1-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Blumcke I, Thom M, Aronica E, et al. The clinicopathologic spectrum of focal cortical dysplasias: a consensus classification proposed by an ad hoc Task Force of the ILAE Diagnostic Methods Commission. Epilepsia. 2011;52(1):158–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02777.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang ZI, Alexopoulos AV, Jones SE, et al. The pathology of magnetic-resonance-imaging-negative epilepsy. Mod Pathol Off J U S Can Acad Pathol Inc. 2013;26:1051–1058. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2013.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hong SJ, Kim H, Schrader D, Bernasconi N, Bernhardt BC, Bernasconi A. Automated detection of cortical dysplasia type II in MRI-negative epilepsy. Neurology. 2014 Jul 1;83(1):48–55. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bernasconi A, Bernasconi N, Bernhardt BC, Schrader D. Advances in MRI for ‘cryptogenic’ epilepsies. Nat Rev Neurol. 2011;7(2):99–108. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2010.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bernhardt BC, Worsley KJ, Besson P, Concha L, Lerch JP, Evans AC, Bernasconi N. Mapping limbic network organization in temporal lobe epilepsy using morphometric correlations: insights on the relation between mesiotemporal connectivity and cortical atrophy. Neuroimage. 2008 Aug 15;42(2):515–24. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.04.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mueller SG, Laxer KD, Barakos J, Cheong I, Garcia P, Weiner MW. Widespread neocortical abnormalities in temporal lobe epilepsy with and without mesial sclerosis. Neuroimage. 2009 Jun;46(2):353–359. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Labate A, Cerasa A, Aguglia U, Mumoli L, Quattrone A, Gambardella A. Neocortical thinning in “benign” mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2011 Apr;52(4):712–717. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bernasconi A, Antel SB, Collins DL, et al. Texture analysis and morphological processing of magnetic resonance imaging assist detection of focal cortical dysplasia in extratemporal partial epilepsy. Ann Neurol. 2001;49:770–775. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Antel SB, Bernasconi A, Bernasconi N, et al. Computational models of MRI characteristics of focal cortical dysplasia improve lesion detection. Neuroimage. 2002;17:1755–1760. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]