Abstract

In developing countries threat of cholera is a significant health concern whenever water purification and sewage disposal systems are inadequate. Vibrio cholerae is one of the responsible bacteria involved in cholera disease. The complete genome sequence of V. cholerae deciphers the presence of various genes and hypothetical proteins whose function are not yet understood. Hence analyzing and annotating the structure and function of hypothetical proteins is important for understanding the V. cholerae. V. cholerae O139 is the most common and pathogenic bacterial strain among various V. cholerae strains. In this study sequence of six hypothetical proteins of V. cholerae O139 has been annotated from NCBI. Various computational tools and databases have been used to determine domain family, protein-protein interaction, solubility of protein, ligand binding sites etc. The three dimensional structure of two proteins were modeled and their ligand binding sites were identified. We have found domains and families of only one protein. The analysis revealed that these proteins might have antibiotic resistance activity, DNA breaking-rejoining activity, integrase enzyme activity, restriction endonuclease, etc. Structural prediction of these proteins and detection of binding sites from this study would indicate a potential target aiding docking studies for therapeutic designing against cholera.

Keywords: cholera, computational tools, docking, drug discovery, Vibrio cholerae O139

Introduction

Vibrio cholerae is a gram-negative, highly motile, curved or comma-shaped rod with a single polar flagellum [1]. V. cholerae is transmitted by the fecal-oral route, mainly found in unhygienic environment. V. cholerae secretes enterotoxin that induces a life-threatening secretory diarrhea called cholera. Cholera is a major epidemic disease. The cholera toxin binds to the plasma membrane of intestinal epithelial cells and releases an enzymatically active subunit which causes a escalation in cyclic adenosine 5-monophosphate (cAMP) production. The resulted high cAMP level inside the cell causes massive secretion of electrolytes and water into the intestinal lumen. Other Vibrios may also be clinically significant for human and some are well-known to cause diseases in domestic animals as well. Nonpathogenic Vibrios are widely dispersed in the environment, mostly in estuarine waters and seafood's [2]. V. cholerae comprises nearly 200 serogroups based on the O antigenic structures [3]. Among them two serogroups of V. cholerae O1 and O139 cause widespread cholera epidemics [4]. The emergence in 1992 of a V. cholerae non-O1 serovar, labeled V. cholerae synonym O139 Bengal, in Bangladesh and India and its subsequent appearance in Southeast Asia, displacing V. cholerae O1 El Tor, was well known causative agent in the history of cholera [5]. In the autumn of 1993, V. cholerae serogroup O139 (Bengal), was implicated in outbreaks of cholera in Bangladesh and India. V. cholerae serogroup O139 (Bengal), causes characteristic severe cholera symptoms and has been implicated in a case of a traveler returning from India to the United States [6]. V. cholerae O139 serogroup strains showed susceptibility to 22 anti-bacterials in various regions of the world and an increase in resistant markers with resistance to fluoroquinolones [7].

During recent years, hundreds of bacterial genomes are available, while their annotation is of interest [8]. However, many of these protein functions are still unknown. For this reason, there is an increasing demand for the annotation of the functions of uncharacterized proteins, called "hypothetical proteins" [9], but the structures of which are known though. Structural genomics initiatives deliver plenty of structures of hypothetical proteins at a constantly growing rate. However, without function annotation, this huge structural storage is of little use to biologists who are interested in particular molecular systems. Additionally some of the proteins, which are known to be sound annotated, may have further functions beyond their listed archives. About half of the proteins in genomes are candidates for hypothetical proteins (HPs) [10]. Many of the "hypothetical proteins" occur in fact in more than one bacterial species, which increases the probability that they are indeed protein coding genes and not the consequence of erroneous gene predictions. Proteins that occur in diverse species can be combined into orthologous groups, which are known to be suitable for functional analyses and annotations of newly sequenced genomes [11].

Improving the functional annotation is of great importance for many follow up studies and we here apply computational tools for function prediction for one of the most devastating human pathogens V. cholerae O139, the causative agent of cholera especially in Southeast Asia. Therefore an improved functional annotation of its proteome is of particular urgency. The annotation of these HPs may be helpful as markers and pharmacological targets. With the overall faith that the majority of hypothetical proteins are the product of pseudogenes, it is necessary to have a tool with the capability of analyzing the minority of hypothetical proteins with a high probability of being expressed [10]. So far, there is no classification of HPs and functioning terms are swapping definitions of hypothetical proteins. Here, we combined physiochemical properties with protein-protein interaction (PPI) based function predictions. Our present study is mainly aimed to predict the structure, function and binding sites of these HPs which are important for docking studies for drug designing.

Methods

Sequence retrieval

Six randomly selected HPs which contain standard number of amino acids sequences of V. cholerae O139 were randomly retrieved from NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) for annotation. Moreover these were supposed to find out interactions between these proteins as they are both from chromosomal and plasmid DNA. The sequence IDs of those 6 HPs were gi|84095108, gi|163644906, gi|163644912, gi|163644916, gi|84468567, and gi|84468557. Various computational tools and databases were used to analyze the different properties i.e., physicochemical, functional, and structural characteristics of HPs.

Physicochemical and functional categorization

By using the Expasy's Protparam server (http://us.expasy.org/tools/protparam) physicochemical characterization, molecular weight, theoretical isoelectric point (pI), total number of positive and negative residues, extinction coefficient [12], instability index [13], aliphatic index (AI) [14] and grand average hydropathy (GRAVY) [15] of HPs were analyzed.

Pfam

Pfam (http://pfam.sanger.ac.uk/) is designed as a comprehensive and accurate collection of protein domains and families [16,17]. Pfam families are typed as Pfam-A and Pfam-B. Each Pfam-A family possess a curated seed alignment containing a small set of envoyed members of the family and an automatically created full alignment which contains all noticeable protein sequences belonging to the family, as defined by profile Hidden Markov Models searches of primary sequence databases. On the other hand, Pfam-B entries are automatically created from the ProDom database and are shown by a single alignment [18].

CDD-BLAST

CD-Search (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi/) was done to find out the conserved domain of these protein sequences. This was performed with the use of RPSBLAST, a modified version of PSI-BLAST, to quickly scan a set of predetermined position-specific scoring matriceswith a protein query [19].

PPI prediction

STRING (http://string.embl.de/) is a database of known and predicted protein interactions by using four sources: Genomic Context, (Conserved) Co-expression, High-throughput Experiments, and Previous Knowledge. STRING currently contains the databases of 5,214,234 proteins from 1,133 organisms [20].

Proteins location prediction

PSORTB (http://www.psort.org/psortb/) server was used to predict the cellular locations of HPs and then SOSUI server was used to find out whether the protein is soluble or trans-membrane in nature (http://bp.nuap.nagoya-u.ac.jp/sosui/sosui_submit.html).

Detection of disulfide bridges

DISULFIND (http://disulfind.dsi.unifi.it/) server was used to predict the presence of any disulfide bond state between cysteine residues in the amino acid sequences of HPs. Moreover, disulfide bridges play a key role in the stabilization of the folding process for many proteins. We analyzed the data using this software. The disulfide bridges are very important finding in the study of structural and functional properties of specific proteins [21].

Protein structure prediction

(PS)2 (pronounced PS square) was used for the prediction of the tertiary structures of HPs (http://www.ps2.life.nctu.edu.tw/). This method combined PSI-BLAST [22,23], IMPALA [24], and T-Coffee [25] by using an effective accord strategy in both target-template selection and target-template alignment. Three dimensional structures were constructed further using the modeling package MODELLER [26,27,28]. The predicted structures obtained from the PS square were saved in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) formats.

Active site prediction

Q-SiteFinder (http://www.modelling.leeds.ac.uk/qsitefinder/) was used to find out the ligand binding sites. It works by finding clusters of probes and binding hydrophobic (CH3) probes to the protein with most favorable binding energy. Q-SiteFinder requires uploading a PDB file or selecting one from the Protein Database. Proteins are primarily scanned for ligands and it uses the interaction energy between the protein and a simple van der Waals probe to locate vigorously favorable binding sites [29]. We used this tool for evaluating these features including the active site in the desired sequence.

Results and Discussion

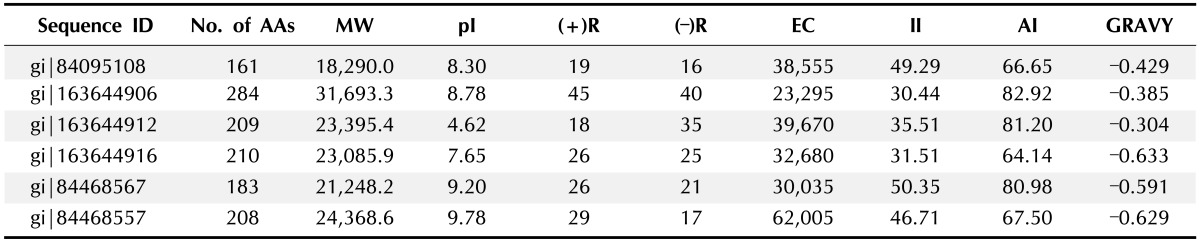

We analyzed the physiochemical properties of these HPs of cholera for the first time. In Table 1 the physicochemical properties of HPs are tabulated. Isoelectric point (pI) of the HP ranges from 4.62 to 9.78. pI is the pH at which the amino acid of protein tolerates no net charge and hence does not move in a direct current electrical field. The determined pI will be handy as solubility is minimum and in an electro focusing system mobility is zero at pI. Moreover proteins become stable and compact at isoelectric pH, for this reason computed pI will be helpful for developing a buffer system for purification by isoelectric focusing method.

Table 1. Physicochemical properties of hypothetical proteins of Protparam tool.

AA, amino acid; MW, molecular weight; pI, isoelectric point; (+)R, total number of positively charged residues (Arg + Lys); (-)R, total number of negatively charged residues (Asp + Glu); EC, extinction coefficient; II, instability index; AI, aliphatic index; GRAVY, grand average hydropathy.

At 280 nm, the extinction co-efficient of HPs ranges from 23295 to 62005 M cm computed by Expasy's Protparam instead of 276, 278, 279, and 282 nm. The presence of high concentration of Cys, Trp, and Tyr indicates a higher extinction coefficient of HPs. The quantitative study of protein-protein and protein-ligand interactions in solution can be done by using this computed extinction coefficients. The instability index value of the HP was found to be ranging from 30.44 to 50.35. It is predicted that a protein will be stable whose instability index is smaller than 40, a value above 40 predicts that the protein will be unstable [13].

Another parameter of structure identification of protein is instability index. Proteins, gi|163644906, gi|163644912, and gi|163644916 were stable and others were unstable. The instability index indicates an approximate stability of proteins in a test tube.

The AI is the relative volume of a protein occupied by aliphatic side chains (A, V, I, and L) and is considered as a positive factor for the raise of thermal stability of globular proteins. The range of the AI for the HPs is from 64.14 to 82.92. The proteins with very high AI may show stability in a wide temperature range where lower AI proteins are not thermal stable and show more flexibility.

The GRAVY of HPs is ranging from -0.304 to -0.633. The better interaction of protein and water is occurring in low GRAVY. The GRAVY value for a protein is calculated by adding the values of hydropathy of all the amino acids and dividing it by the number of residues in the sequence [14].

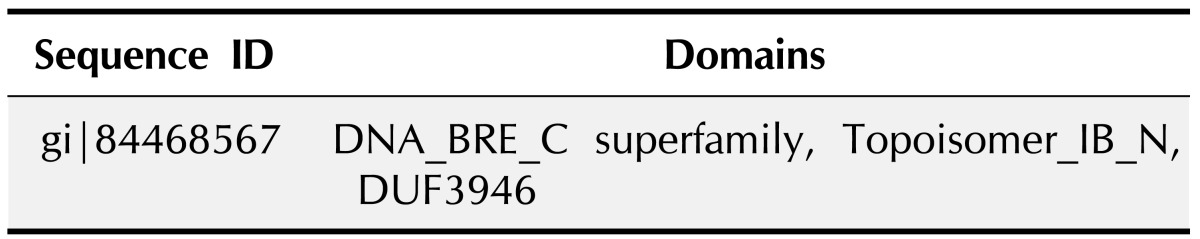

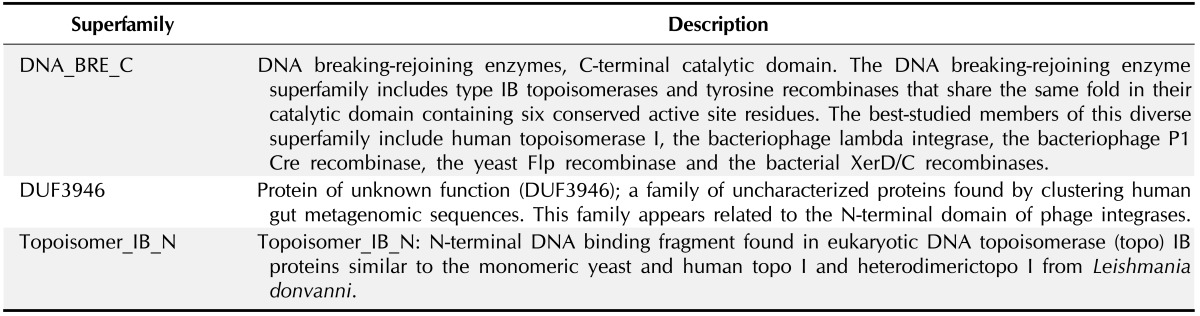

To study the functional analysis conserved domains were observed because conserved domains are functional units within a protein that act as building blocks in molecular evolution and recombine in various arrangements to make proteins with different functions. The data are then used for putative functional annotation of protein query sequences based on matches to specific super-families history, identification of proteins with similar domain. The proteins have been classified into particular families based on the presence of specific domains in the sequence [19]. In our study we used 6 HPs but found only 1 protein gi|84468567 possessing specific domains which were DNA_BRE_C super-family, Topoisomer_IB_N, DUF3946 domains and they were classified as super-families accordingly. The presence of these domains in the HPs indicates that the protein might do the same function. The domains of the HP gi|84468567 and their super-family is given by function in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2. Identification of domains by CDD-BLAST.

Table 3. Functional description of superfamilies of hypothetical proteins.

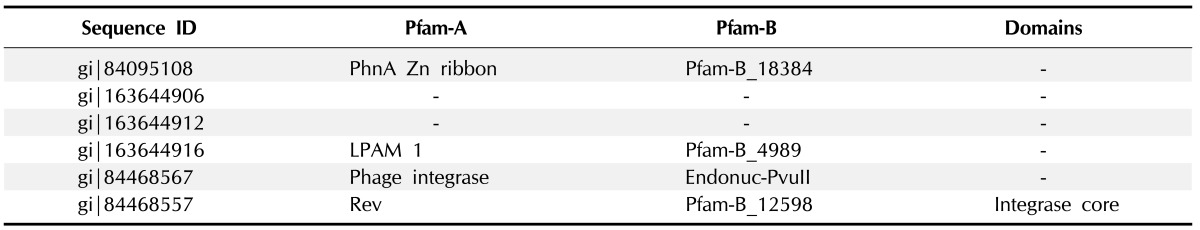

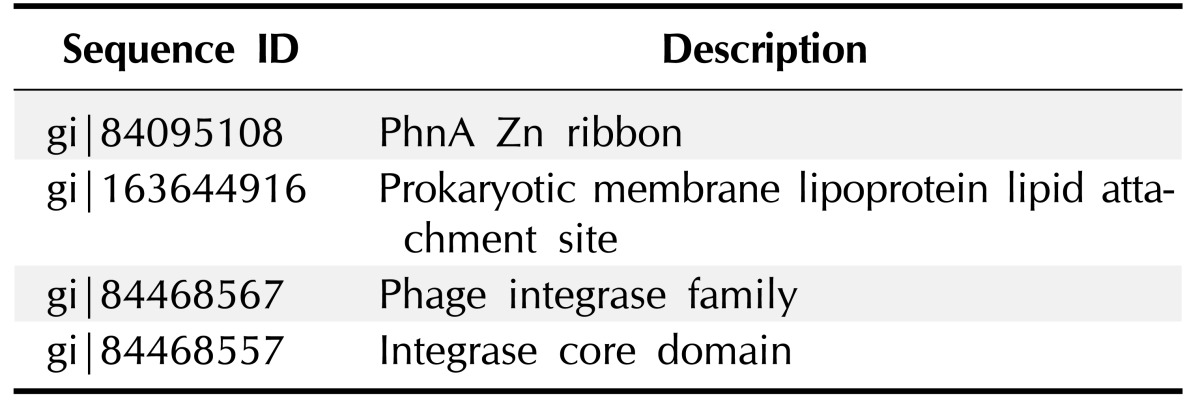

Domains and families present in HPs were identified by the Pfam database research (Tables 4 and 5). They are PhnA Zn ribbon, prokaryotic membrane lipoprotein lipid attachment site, Phage integrase family and integrase core domain.

Table 4. Families found in Pfam database.

Table 5. Descriptions of Pfam families of hypothetical proteins.

To explain the protein functions involved in various cellular processes it is important to know the sub-cellular localization of that protein. During the drug discovery process knowledge of the sub-cellular localization of a protein play a very significant role in target identification.

In our study, we have found two proteins gi|163644906, gi|184468567 are cytoplasmic as their best performing sites. The remaining other protein localization was not found. The server SOSUI differentiates whether the HPs are membranous or soluble. No trans-membrane protein was found and all were soluble.

Moreover, DISULPHIND server revealed no disulphide bonds were present in any of those proteins which indicate that they were thermally unstable. Moreover, disulfide bridges play a major role in stabilizing the folding process of many proteins. Disulfide bridges are very important finding in the study of structural and functional properties of specific proteins [21].

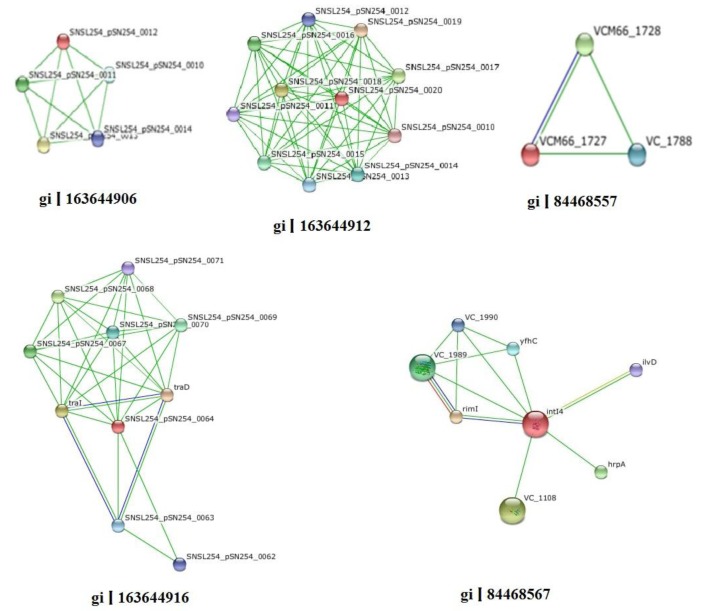

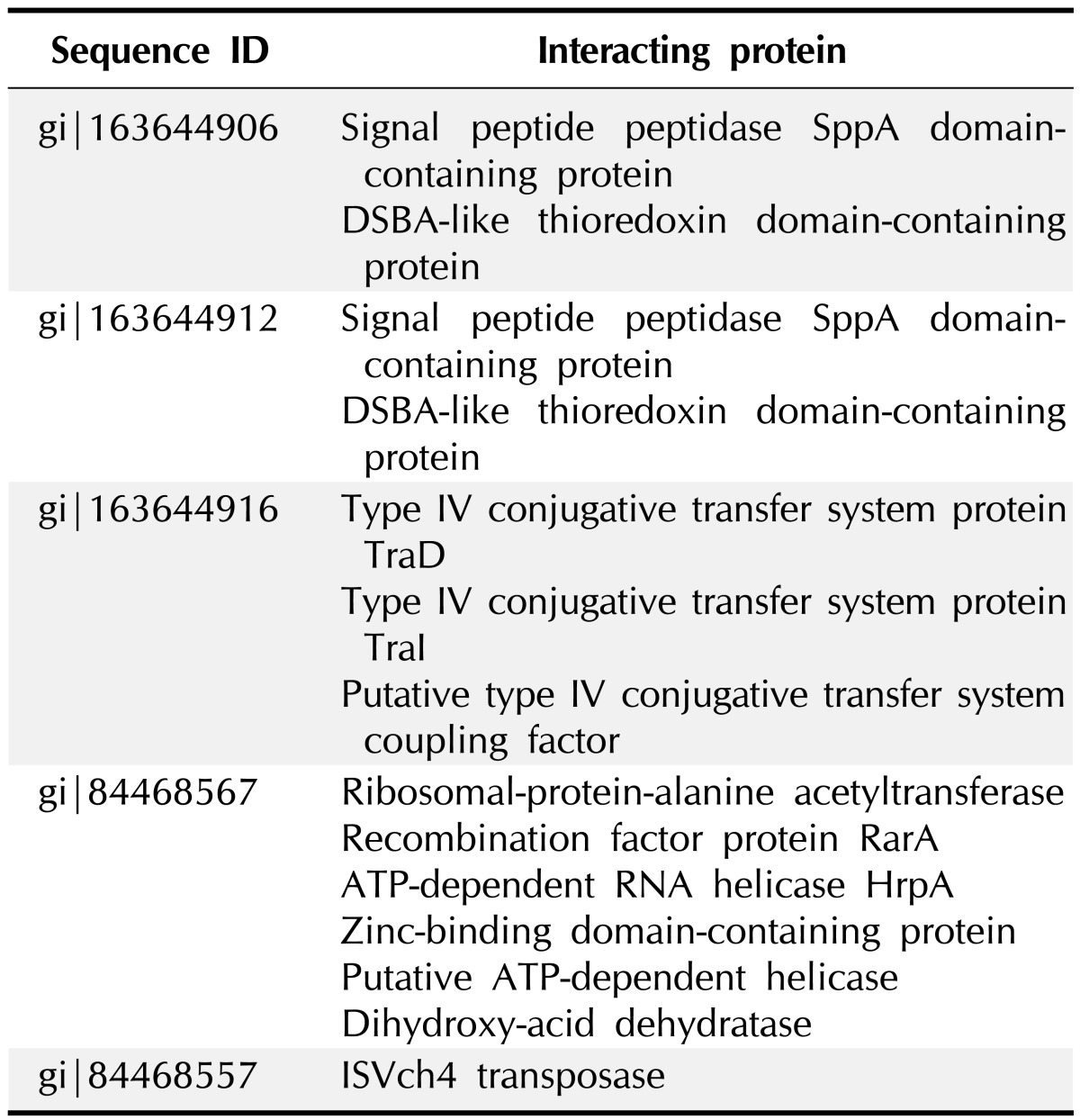

For performing almost all the cellular functions the PPI are important. Proteins often interact with one another in a mutually dependent way to perform a common function. It is notable that translational factors interact among themselves to carry out the whole translation. The function of protein is predictable from this based on their interaction with other proteins. It is very rare that proteins bring out function with any interactions with other biomolecules. For this reason, in this post genomic era PPI databases have turned as a most important resource for searching biological networks and pathways in cells [29]. The proteins gi|163644906 and gi|163644912 were found to have interaction with 2 proteins signal peptide peptidase SppA domain-containing protein and DSBA like thioredoxin domain containing protein. gi|163644916 had interacted with 3 proteins such as IV conjugative transfersystem protein TraD & TraI, putative type IV conjugative transfer system coupling factor. gi|84468567 showed interaction with 6 proteins which were (1) ribosomal protein-alanine acetyl transferase, (2) recombination factor protein RarA, (3) ATP-dependent RNA helicase HrpA, (4) Zinc-binding domain-containing protein, (5) putative ATP-dependent helices, and (6) dihydroxy-acid dehydrates. gi|84468557 protein interacted only one protein ISVch4 transposes. Other HPs do not interact with any other proteins. Fig. 1 and Table 6 indicate the protein-protein interacting networks of HPs, which might have functions of their interacting proteins [30, 31].

Fig. 1. Protein-protein interaction of hypothetical proteins.

Table 6. Hypothetical proteins interacting with functionally important proteins.

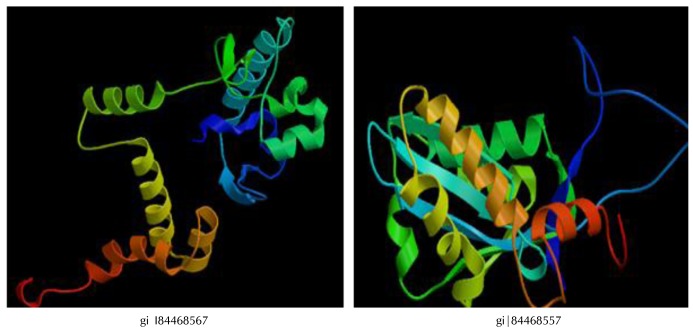

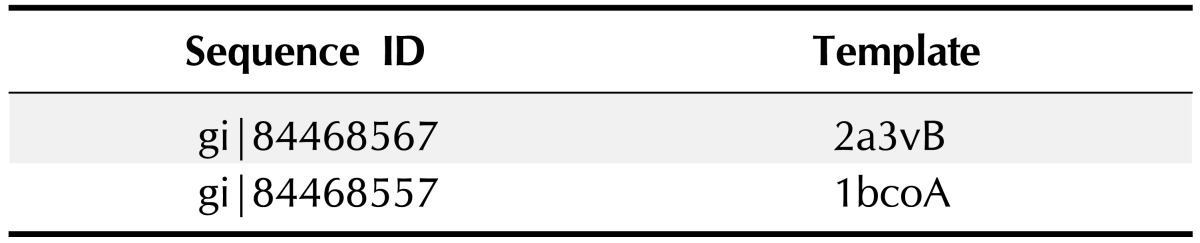

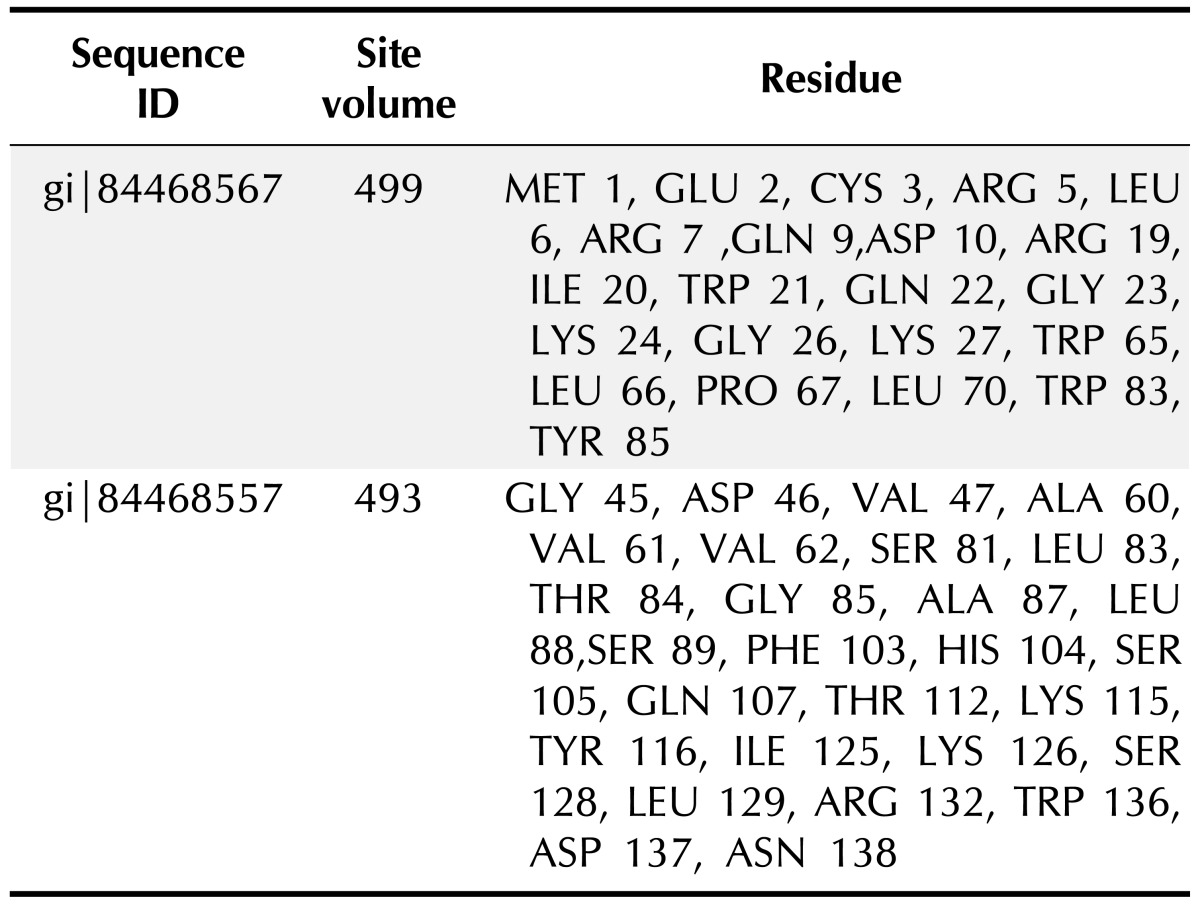

PS square server (Fig. 2) was used to determine the three dimensional structure of the HPs. Out of 6 HPs, the PS square server could model only 2 proteins. Due to low sequence identity, the other four proteins could not be modeled. The server used templates to model those proteins which were tabulated in Table 7. The location of ligand binding site identification on protein is important for a wide range of applications including structural identification, comparison of functional sites, molecular docking and de novo drug design. Active site residues of the HPs are mentioned in Table 8. This data of active binding site residues will give insight into identifying binding interactions and docking with specific ligand.

Fig. 2. Three-dimensional structure of hypothetical protein by PS square.

Table 7. Templates used by PS square server for modeling.

Table 8. Residues involved in ligand binding sites predicted by QSITE finder.

We have retrieved 6 HPs from NCBI database and determined their physicochemical properties and identified domains and families using various Bioinformatics tools and databases. The three dimensional structure of those HPs were modeled (only 2) and their ligand binding sites were identified. Among them we have found domains and families of only one HP, analysis showed that the domains and families are involved in DNA breaking-rejoining activities, integrase activity. All of these features from our findings may be used to design new potential drugs against this infectious bacterium.

References

- 1.Reidl J, Klose KE. Vibrio cholerae and cholera: out of the water and into the host. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2002;26:125–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2002.tb00605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Finkelstein RA. Cholera, Vibrio cholerae O1 and O139, and other pathogenic Vibrios. In: Baron S, editor. Medical Microbiology. 4th ed. Galveston: University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston; 1996. pp. 158–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shanan S, Abd H, Hedenström I, Saeed A, Sandström G. Detection of Vibrio cholerae and Acanthamoeba species from same natural water samples collected from different cholera endemic areas in Sudan. BMC Res Notes. 2011;4:109. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-4-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siddique AK, Baqui AH, Eusof A, Haider K, Hossain MA, Bashir I, et al. Survival of classic cholera in Bangladesh. Lancet. 1991;337:1125–1127. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)92789-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alam AN, Alam NH, Ahmed T, Sack DA. Randomised double blind trial of single dose doxycycline for treating cholera in adults. BMJ. 1990;300:1619–1621. doi: 10.1136/bmj.300.6740.1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Large epidemic of cholera-like disease in Bangladesh caused by Vibrio cholerae O139 synonym Bengal. Cholera Working Group, International Centre for Diarrhoeal Diseases Research, Bangladesh. Lancet. 1993;342:387–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krishna BV, Patil AB, Chandrasekhar MR. Fluoroquinoloneresistant Vibrio cholerae isolated during a cholera outbreak in India. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2006;100:224–226. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roberts RJ. Identifying protein function: a call for community action. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:E42. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galperin MY, Koonin EV. 'Conserved hypothetical' proteins: prioritization of targets for experimental study. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:5452–5463. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedberg I. Automated protein function prediction: the genomic challenge. Brief Bioinform. 2006;7:225–242. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbl004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eisen JA. Phylogenomics: improving functional predictions for uncharacterized genes by evolutionary analysis. Genome Res. 1998;8:163–167. doi: 10.1101/gr.8.3.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gill SC, von Hippel PH. Calculation of protein extinction coefficients from amino acid sequence data. Anal Biochem. 1989;182:319–326. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90602-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guruprasad K, Reddy BV, Pandit MW. Correlation between stability of a protein and its dipeptide composition: a novel approach for predicting in vivo stability of a protein from its primary sequence. Protein Eng. 1990;4:155–161. doi: 10.1093/protein/4.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ikai A. Thermostability and aliphatic index of globular proteins. J Biochem. 1980;88:1895–1898. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kyte J, Doolittle RF. A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. J Mol Biol. 1982;157:105–132. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90515-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sonnhammer EL, Eddy SR, Durbin R. Pfam: a comprehensive database of protein domain families based on seed alignments. Proteins. 1997;28:405–420. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0134(199707)28:3<405::aid-prot10>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Finn RD, Mistry J, Schuster-Böckler B, Griffiths-Jones S, Hollich V, Lassmann T, et al. Pfam: clans, web tools and services. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D247–D251. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bru C, Courcelle E, Carrère S, Beausse Y, Dalmar S, Kahn D. The ProDom database of protein domain families: more emphasis on 3D. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D212–D215. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marchler-Bauer A, Lu S, Anderson JB, Chitsaz F, Derbyshire MK, DeWeese-Scott C, et al. CDD: a Conserved Domain Database for the functional annotation of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D225–D229. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Szklarczyk D, Franceschini A, Kuhn M, Simonovic M, Roth A, Minguez P, et al. The STRING database in 2011: functional interaction networks of proteins, globally integrated and scored. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D561–D568. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ceroni A, Passerini A, Vullo A, Frasconi P. DISULFIND: a disulfide bonding state and cysteine connectivity prediction server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W177–W181. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schäffer AA, Aravind L, Madden TL, Shavirin S, Spouge JL, Wolf YI, et al. Improving the accuracy of PSI-BLAST protein database searches with composition-based statistics and other refinements. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:2994–3005. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.14.2994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Notredame C, Higgins DG, Heringa J. T-Coffee: a novel method for fast and accurate multiple sequence alignment. J Mol Biol. 2000;302:205–217. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marti-Renom MA, Stuart AC, Fiser A, Sánchez R, Melo F, Sali A. Comparative protein structure modeling of genes and genomes. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2000;29:291–325. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.29.1.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fiser A, Do RK, Sali A. Modeling of loops in protein structures. Protein Sci. 2000;9:1753–1773. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.9.1753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hasan MA, Alauddin SM, Al Amin M, Nur SM, Mannan A. In silico molecular characterization of cysteine protease YopT from Yersinia pestis by homology modeling and binding site identification. Drug Target Insights. 2014;8:1–9. doi: 10.4137/DTI.S13529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen CC, Hwang JK, Yang JM. (PS)2: protein structure prediction server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W152–W157. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laurie AT, Jackson RM. Q-SiteFinder: an energy-based method for the prediction of protein-ligand binding sites. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:1908–1916. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peri S, Navarro JD, Amanchy R, Kristiansen TZ, Jonnalagadda CK, Surendranath V, et al. Development of human protein reference database as an initial platform for approaching systems biology in humans. Genome Res. 2003;13:2363–2371. doi: 10.1101/gr.1680803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hasan A, Mazumder HH, Khan A, Hossain MU, Chowdhury HK. Molecular characterization of legionellosis drug target candidate enzyme phosphoglucosamine mutase from Legionella pneumophila (strain Paris): an in silico approach. Genomics Inform. 2014;12:268–275. doi: 10.5808/GI.2014.12.4.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]