Abstract

In the carnivorous plant genus Genlisea a unique lobster pot trapping mechanism supplements nutrition in nutrient-poor habitats. A wide spectrum of microbes frequently occurs in Genlisea's leaf-derived traps without clear relevance for Genlisea carnivory. We sequenced the metatranscriptomes of subterrestrial traps vs. the aerial chlorophyll-containing leaves of G. nigrocaulis and of G. hispidula. Ribosomal RNA assignment revealed soil-borne microbial diversity in Genlisea traps, with 92 genera of 19 phyla present in more than one sample. Microbes from 16 of these phyla including proteobacteria, green algae, amoebozoa, fungi, ciliates and metazoans, contributed additionally short-lived mRNA to the metatranscriptome. Furthermore, transcripts of 438 members of hydrolases (e.g., proteases, phosphatases, lipases), mainly resembling those of metazoans, ciliates and green algae, were found. Compared to aerial leaves, Genlisea traps displayed a transcriptional up-regulation of endogenous NADH oxidases generating reactive oxygen species as well as of acid phosphatases for prey digestion. A leaf-vs.-trap transcriptome comparison reflects that carnivory provides inorganic P- and different forms of N-compounds (ammonium, nitrate, amino acid, oligopeptides) and implies the need to protect trap cells against oxidative stress. The analysis elucidates a complex food web inside the Genlisea traps, and suggests ecological relationships between this plant genus and its entrapped microbiome.

Keywords: Genlisea, plant carnivory, lobster pot trapping, metatranscriptomics, RNA-sequencing, whole-genome gene transcription analysis, algae commensalism, plant-microbe interaction

Introduction

Carnivory, including trapping and subsequent digestion of prey, has evolved several times in plants. About 800 species from five angiosperm orders (Albert et al., 1992; Ellison and Gotelli, 2009) are known to be carnivorous. Although carnivorous plants are distributed worldwide, their occurrence is ecologically restricted to open, wet, nutrient-poor habitats. This indicates that the nutritional benefit from carnivory supports survival of carnivorous plants in such environments. On the other hand, high costs for maintenance of trapping organs and reduced photosynthetic capacity exclude botanical carnivores from most other habitats (Soltis et al., 1999; Farnsworth and Ellison, 2008; Fedoroff, 2012; Król et al, 2012).

Lentibulariaceae, the largest monophyletic carnivorous plant family, comprises three genera, Pinguicula, Utricularia and Genlisea, with three different trapping mechanisms (Jobson et al., 2003; Muller et al., 2006). Similarly to Drosera, the primitive butterwort (Pinguicula) secretes mucilagous adhesive substances in order to capture insects on its leaves (Legendre, 2000). However, Utricularia (bladderwort) and Genlisea (corkscrew plant) use modified leaves either as suction traps (Utricularia) or as lobster pot traps (Genlisea). The bladder-like suction traps of Utricularia generate a water flow that carries small prey (e.g., Daphnia species) within 10 −15 ms into the bladder (Vincent et al., 2011). The prey is digested inside the bladder by means of numerous hydrolases and reactive oxygen species. RNA-seq analysis revealed similar transcriptomes between Utricularia vegetative leaves and chlorophyll-free traps (Ibarra-Laclette et al., 2011), but traps contained more transcripts for hydrolytic enzymes for prey digestion and displayed an overexpression of genes involved in respiration compared to aerial photosynthesizing leaves. Colonizing oligotrophic white sands and moist outcrops in tropical Africa and South America, rootless Genlisea species evolved corkscrew shaped subterranean traps to catch protozoa and small metazoa (Barthlott et al., 1998; Plachno et al., 2007; Fleischmann et al., 2010). Trap inward-pointing hairs prevent prey escape and allow only one-way movement toward the “digestion chamber”. Numerous secretory glands in traps apparently produce hydrolases such as acid phosphatases, proteases and esterases in order to digest prey to gain additional N, P and minerals (Adamec, 1997; Ellison and Gotelli, 2001). In spite of detailed knowledge of Genlisea trap anatomy, the complexity of interactions within lobster traps is still not well understood, for instance whether the prey needs to be actively motile to invade traps or whether a passive invasion via a liquid turn-over is also possible. There are multiple reports on specialized organisms surviving and propagating in the traps of carnivorous plants (Siragusa et al., 2007; Peterson et al., 2008; Adlassnig et al., 2011; Koopman and Carstens, 2011; Krieger and Kourtev, 2012). Inside the Utricularia and Genlisea traps, diverse microbial communities, mainly comprising bacteria, algae, protozoa and rotifers, could live as epiphytes or parasites or might support plant fitness in the context of prey digestion before or without becoming digested themselves (Skutch, 1928; Jobson and Morris, 2001; Richards, 2001; Sirová et al., 2003, 2009; Płachno et al., 2005; Adamec, 2007; Plachno and Wolowski, 2008; Caravieri et al., 2014). So far, little is known about host-microbiome interactions other than microbe's role as source of nutrients, and about possible mutually beneficial impacts of entrapped microbes and their host species. Nevertheless, soil microbes which are associated with root systems of plants (named as root or rhizosphere microbiomes) or live inside plants (named as bacterial/microbial endophytes) have been shown to be important for plant growth and health (for review see Lugtenberg and Kamilova, 2009; Reinhold-Hurek and Hurek, 2011; Berendsen et al., 2012; Rout and Callaway, 2012; Bakker et al., 2013; Vandenkoornhuyse et al., 2015). On the other hand, increasing evidence from different plant systems suggest that plants predominantly influence and modulate the root microbial communities by the active secretion of compounds in so-called root exudates (Broeckling et al., 2008; Badri et al., 2013; Kierul et al., 2015). Moreover, specialized soil microbes with high biomass-degrading capacity could be selected or cultivated, for example in an herbivore microbiome of the leaf-cutter ant (Atta colombica) (Suen et al., 2010).

A trap dimorphism has been described for several Genlisea species (Studnicka, 1996; Fleischmann, 2012), e.g., for G. nigrocaulis, which possesses thick, short-stalked surface traps and filiform, long-stalked deep-soil traps (Figure 1A). In contrast, G. hispidula traps are all filiform. Whether different traps contain specific soil microbial communities is still an open question. Here we present, based on a metatranscriptomics approach, a comprehensive diversity characterization of microbial food webs inside the G. nigrocaulis and G. hispidula traps under homogeneous laboratory conditions. Ribosomal RNA reads, ribotags, from deep sequencing libraries were used to define an “active” community composition across kingdoms which was not achieved in previous studies on prey composition in Genlisea species. In order to investigate profound plant-microbe interactions in the Genlisea trap environment, active metabolic pathways of the entrapped microbiome were reconstructed and Genlisea trap-specific and differentially expressed transcripts were analyzed.

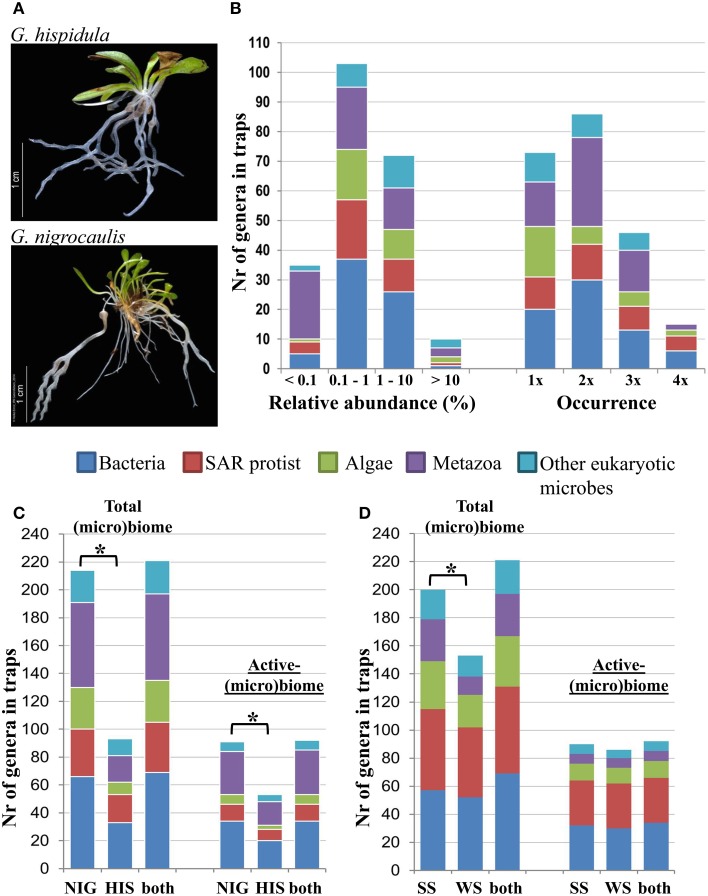

Figure 1.

Morphology and (micro)biome composition in Genlisea traps. (A) G. hispidula has only filiform rhizophylls, while G. nigrocaulis displays a trap dimorphism with thick, short-stalked surface traps and filiform, long-stalked deep-soil traps. (B) Relative abundance and occurrence of microbe genera of five categories: bacteria, SAR protists (Stramenopiles, Alveolata, and Rhizaria), metazoans and other eukaryotic microbes. Occurrence reflects the number of times a specific genus is found across the 8 different Genlisea metatranscriptome libraries. (C,D) Number of genera in Genlisea traps according to species (C) or season (D). The active-(micro)biome of Genlisea traps containing preferentially entrapped genera is defined as (i) ≥0.1% relative abundance among each of the five categories; (ii) occurred at least in two trap samples regardless of species or seasonal sampling time; and (iii) trap enrichment with ≥2-fold-change of abundance between traps and leaves. Asterisk indicates significant difference (p < 0.05, paired Student's t-Test). HIS, G. hispidula; NIG, G. nigrocaulis; SS, summer season; WS, winter season.

Materials and methods

Plant sampling, RNA isolation and sequencing

G. nigrocaulis STEYERM and G. hispidula STAPF [obtained from commercial sources: Best Carnivorous Plants (bestcarnivorousplants.com), Merzig (carnivorsandmore.de) and Nüdlingen (falle.de)] were cultivated in the greenhouse of the IPK Gatersleben, Germany. Plants were grown in pots with a mixture of peat and sand. The soil was kept wet by rain water, containing small organisms living naturally inside. Leaves and traps of both species were collected in summer season 2010 (SS) and winter season 2011 (WS) after thorough cleaning with 2 l of running cold distilled water. Total RNA samples were isolated using RNeasy Kit (Qiagen) with DNaseI treatment. The sample quality was controlled on a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent). Illumina RNA-TruSeq libraries were prepared from 1 μg RNA of each sample without mRNA enrichment or rRNA depletion. Illumina Hiseq2000 paired-end sequencing (2x100 bp reads, 200 bp insert size) resulted in at least 31 million reads per library (Table 1). The raw RNA-seq data is deposited in the project “PRJEB1867” at the European Nucleotide Archive (www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/).

Table 1.

Summary of RNA-sequencing output and read mapping analysis.

| Sample name | Species | Season | Organ | SRA IDs | Total high quality reads | Library proportion | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rRNA readsa | Genlisea readsb | Non-host mRNA readsc | ||||||||||

| Experiment | Sample | Read number | % of reads | Read number | % of reads | Read number | % of reads | |||||

| NIG_SS_t | G. nigrocaulis | Summer | Trap | ERX272583 | ERS257172 | 55,570,966 | 122,734 (218,975) | 0.22 (0.39) | 18,190,523 | 32.73 | 6,790,717 | 12.22 |

| NIG_SS_l | G. nigrocaulis | Summer | Leaf | ERX272581 | ERS257171 | 68,905,010 | 290,521 (492,631) | 0.42 (0.71) | 39,416,889 | 57.20 | 148,530 | 0.22 |

| NIG_WS_t | G. nigrocaulis | Winter | Trap | ERX272584 | ERS257172 | 39,914,128 | 195,871 (297,182) | 0.49 (0.74) | 17,107,634 | 42.86 | 2,811,952 | 7.05 |

| NIG_WS_l | G. nigrocaulis | Winter | Leaf | ERX272582 | ERS257171 | 31,504,414 | 127,178 (194,034) | 0.40 (0.62) | 21,144,415 | 67.12 | 10,564 | 0.03 |

| HIS_SS_t | G. hispidula | Summer | Trap | ERX272589 | ERS257479 | 83,721,886 | 131,033 (203,470) | 0.16 (0.24) | 13,312,311 | 15.90 | 40,547 | 0.05 |

| HIS_SS_l | G. hispidula | Summer | Leaf | ERX272587 | ERS257478 | 73,706,164 | 41,958 (72,126) | 0.06 (0.1) | 12,170,713 | 16.51 | 17,254 | 0.02 |

| HIS_WS_t | G. hispidula | Winter | Trap | ERX272590 | ERS257479 | 60,971,788 | 91,577 (133,429) | 0.15 (0.22) | 8,733,316 | 14.32 | 2,783 | 0.005 |

| HIS_WS_l | G. hispidula | Winter | Leaf | ERX272588 | ERS257478 | 60,849,726 | 80,315 (124,529) | 0.13 (0.20) | 7,471,549 | 12.28 | 538,121 | 0.88 |

SILVA LSURef_115 and SSURef_NR99_115 sequences were used as reference for read mapping with minimal 97% similarity (or minimal 80% similarity in brackets).

Annotated G. nigrocaulis genome sequences were used as reference for read mapping with minimal 80% similarity (the G. nigrocaulis genome is 18 times smaller and has one third of the gene number compared to G. hispidula).

Non-redudant and trap-specific de novo assembled contigs (≥1 kbp) of G. nigrocaulis trap libraries after filtering out rRNA or Genlisea gene containing contigs were used as reference for read mapping with at least 80% similarity.

Taxonomic assignment of RNA-seq reads

RNA-Seq reads from total RNA libraries were trimmed for sequence quality using the standard pipeline (quality limit 0.05, minimum read length 80) of the CLC Genomics Workbench v5.5.1 (CLC bio, Cambridge, MD). Using the RNA-seq module of the CLC Genomics Workbench, trimmed and high quality reads from each dataset were mapped to the non-redundant and truncated version of the ribosomal RNA SILVA reference sequences [LSURef_115 and SSURef_NR99_115, (Quast et al., 2013)]. With standard mapping parameters (minimum length 90% and minimum similarity 80%), on average 0.4% reads of each library could be mapped to rRNA reference sequences (Table 1). In order to remove potentially false assignment, more strict mapping parameters with minimum similarity 97% were applied. Mapping outputs (total mapped reads) of SILVA reference sequences which were mapped by at least one unique read were summarized for each phylotype using the SILVA taxonomy description by MEGAN software (v 5.8.6, Huson et al., 2011). Taxonomy rarefaction plot was performed in MEGAN for all bacterial taxa (Figure S1). For taxonomic affiliation, ribosomal sequences of eukaryotic cellular organelles (mitochondria, chloroplast) were not taken into account.

Relative abundance (read count per total million reads) and reoccurrence of each assigned genus were categorized as Bacteria, SAR protozoans (Stramenopiles, Alveolata, and Rhizaria), green algae (Chlorophyta), metazoan or other eukaryote groups. For each category, a relative abundance cutoff of 0.1% and at least appearance within two samples was applied at genus level for each library. Trap enrichment was calculated as the fold change in abundance of each phylotype between trap sample and its corresponding leaf sample. For every phylotype, a paired t-test was used to determine significant differences for pairwise comparisons between trap and leaf samples of each plant species, and for the winter season vs. the summer season (seasonal effect). NCBI Taxonomy IDs of assigned genera were extracted by the Tax Identifier tool (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Taxonomy/TaxIdentifier/tax_identifier.cgi) and used for drawing a phylogenetic tree by the phyloT tree generator (http://phylot.biobyte.de) and iTOL graphical editor (http://itol.embl.de/).

Clustering and phenotype enrichment analysis in comparison with reference environmental datasets

The same taxonomy assignment pipeline was applied for 18 published metatranscriptome Illumina sequencing datasets of creek, soil, feces, marine sediment, marine water body and lake habitats (Table S1, Caporaso et al., 2011). A total of 13,246 bacterial SILVA reference sequences have at least one unique mapped read in one dataset. UPMA clustering analysis of bacteria diversity in all datasets with the Bray-Curtis matrix was performed with all bacterial taxa by using MEGAN software (v 5.8.6). Bacterial phylotypes with corresponding read counts were imported into METAGENassist (Arndt et al., 2012, www.metagenassist.ca) for mapping bacterial phenotypic information. Several phenotype categories including oxygen requirement, energy source, metabolism and habitat may have multiple phenotypic traits associated with a given taxon. A paired t-test was used to examine differences in species richness and intra-group similarity between different attributes such as organs, species and seasons.

De novo assembly and analysis of trap-specific community transcriptomes

Trimmed and high quality reads from each G. nigrocaulis library were separately de novo assembled by the CLC Genomics Workbench 5.5.1 with automatic bubble and word sizes and minimal 200 bp contig length. Contigs longer than 500 bp were sequentially filtered out of G. nigrocaulis high and low confidence transcripts (Vu et al., unpublished), SILVA LSURef_115 and SSURef_NR99_115 sequences by using ublast (1E-09) of the Usearch software (v 7.0.1090_win32, (Edgar, 2010). The remaining contigs from trap samples were clustered at 80% identity by Usearch and subsequently filtered out from (ublast, 1E-09) de novo assembled contigs of leaf samples, resulting in 31,710 non-redundant microbe transcript contigs longer than 1000 bp.

The 31,710 microbe transcript contigs (in total 51.2 Mbp) served as a reference for read mapping using the RNA-seq module of the CLC Genomics Workbench v5.5.1 with standard mapping parameters (minimum length 0.9 and minimum similarity 0.8) for all 8 Genlisea mRNA-seq datasets (Table 1). Relative abundance (read count per total million reads) and fold change of abundance between trap and leaf were calculated for every contig. A similar analysis was performed using the annotated G. nigrocaulis genome (Vu et al., unpublished) as reference. Transcript amounts (in reads per kilobase of exon per million reads) were calculated for every gene and quantile-normalized. Log2 ratios were used to measure relative changes in expression level between each pair of trap and its corresponding leaf sample. Genes were considered expressed if they have (1) more than one unique mapped read and (2) have more than five total mapped reads. Absolute values of the corresponding log2 ratios higher than 2 and the p-value of a paired t-test (trap vs. leaf) lower than 0.05 are conditions for selecting differentially expressed genes.

Functional annotation of differentially transcribed genes and enrichment analysis

By using Blast2GO (Conesa and Gotz, 2008), 12,564 microbe transcripts of 1500–8000 bp length (comprising 27.9 Mbp and corresponding 54.5% of the transcribed microbial sequences) were blasted against the NCBI protein reference sequence (E-value cut off 10−3) and further annotated with default filtering parameters (E-value cutoff 10−6, Annotation cutoff 55, GO Weight 5). Generic GO-slim categories were used to provide a summary of GO annotation results. Enzyme code class assignment was exploited to define the list of hydrolases. Species information and bit score of blastx from the best blast hit result of every transcript were exported and taxonomically summarized by LCA algorithm from MEGAN software with a minimum score 50. Phyla which have been detected by ribosomal RNA assignment were used as main categories. Best hits from Chordata species were referred to as the Metazoa group. Enrichment analysis using the Fishers's Exact Test with Multiple Testing Correction of standard false discovery rate (FDR) was carried out in Blast2Go for enriched GO categories with a p-value cutoff of 0.05.

Results and discussion

The Genlisea traps primarily serve as the root-substitutes, anchoring the plant in the soil and absorbing soil-borne nutrients. Importantly, these chlorophyll-free, subterranean rhizophylls are tubular, modified leaves which resemble a lobster pot, retaining numerous and highly diverse microbes and small animals as prey in order to provide complement nutrients via carnivorous diet. To identify active players in this semi-closed food web, we examined total RNA from leaves and traps of perennial G. nigrocaulis and G. hispidula and characterized the trap microbiome by metaRNA sequencing. Extensive washing of the samples prior to RNA extraction was applied in order to remove loosely associated microbes on surfaces of plant tissues. Two winter and summer season replicates of each sample were analyzed.

Trap-specific enrichment among the highly diverse and dynamic phylotypes of Genlisea traps

Deep sequencing has been shown to be a suitable approach for large-scale comparisons of microbial communities (Caporaso et al., 2011; Yarza et al., 2014). With whole-community RNA sequencing, amplification bias and primer design limitations in rRNA amplicon sequencing approaches can be compensated. Moreover, because of the short mRNA half-life, metatranscriptomics presents abundance information on active populations in the community. By using a stringent mapping approach, we assigned on average 135,148 ribosomal RNA reads of each RNA-seq library to ribosomal RNA SILVA reference sequences with 39–188 phylotypes at genus level (Table 1, Figure 1). On average, microbial communities in G. nigrocaulis traps (144–188 genera) were more diverse than in G. hispidula (39–73 genera) traps, regardless of seasonal sampling. Overall we found in Genlisea trap samples 184 out of total 220 uniquely detected genera having at least 0.1% relative abundance of either bacteria, SAR protists (Stramenopiles, Alveolata and Rhizaria), green algae (Chlorophyta), metazoa, or other eukaryotic microbes (Figure 1B). The majority of genera (103 out of 184 = 55.9%) in Genlisea traps were rare (0.1–1% abundance), suggesting high sensitivity of the RNA-seq sequencing approach. The dominant genera with >10% of each phylogenetic group include the widespread aerobic soil bacterium Pedosphaera, the freshwater ciliate Tetrahymena, two freshwater planktonic green algae Chlamydomonas and Carteria, the minute worm Aeolosoma, the predatory flatworm Stenostomum, the cosmopolitan oribatid mite Trhypochthonius, the aquatic fungus Entophlyctis, and two amoebae (the flagellate Phalansterium and the lancet-shaped Paradermamoeba). Of 220 detected genera, 33.2% were found only in a single trap sample and only 6.8% were in all trap samples regardless of season and Genlisea species tested. The green algae Carteria and the fungus Entophlyctis were prevalent in only one sample, while eight other dominant genera appeared in more than one trap sample.

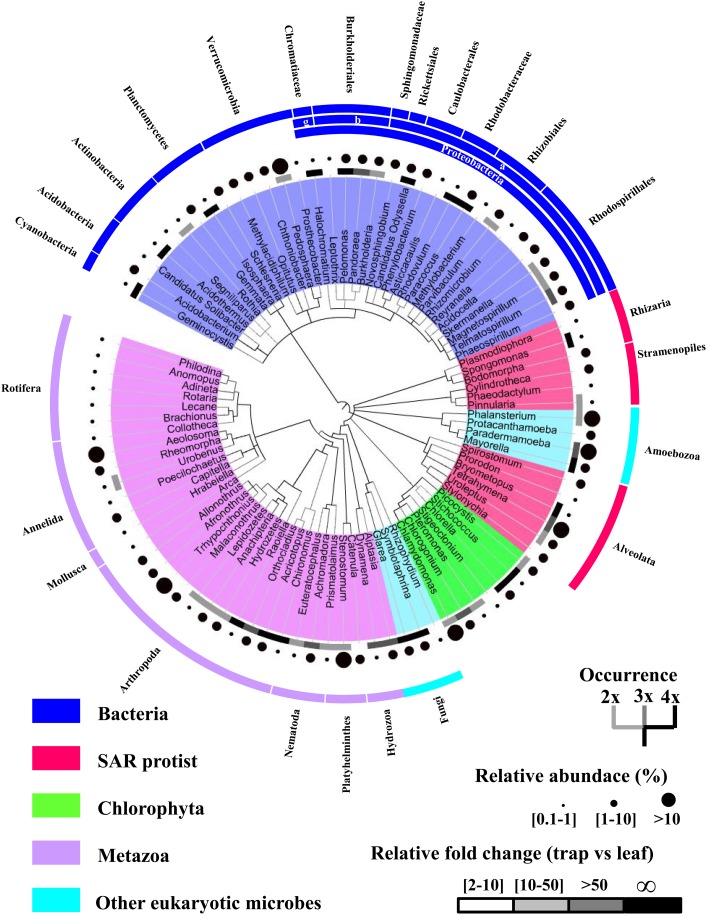

Among the 133 genera having 0.1% or higher relative abundance and being found in at least two trap samples, 92 genera belonging to 19 phyla were enriched (two-fold or higher relative abundance) in traps in comparison with corresponding leaves (Figure 2). These preferentially entrapped or trap-enriched organisms, here defined as the active-(micro)biome of Genlisea traps, consist of 34 bacteria, 12 SAR protists, 7 green algae, 32 metazoa, and 7 other eukaryotic genera. Proteobacteria, Chlorophyta (green algae) and Arthropoda represent the most diverse phyla in this community, largely extending the view of Barthlott et al. (1998). These authors proposed that Genlisea species are specialized in capturing protozoans, based on their laboratory experiments and field observations. Microscopic studies on trap content of different cultivated and field collected Genlisea species showed that mites (Acari), roundworms (Nematoda), flatworms (Platyhelminthes), annelids (Annelida) and rotifers (Rotifera) are common prey (Płachno et al., 2005; Fleischmann, 2012). In addition, unicellular algae were also frequently encountered inside of the Genlisea rhizophylls as prey and/or as commensals (Płachno et al., 2005; Plachno and Wolowski, 2008). Our data suggest an even richer bacteria community than the 10 bacterial genera including Phenylobacterium and Magnetospirillum that were found in 16S rDNA amplification libraries of Genlisea filiformis traps collected from natural habitats (Caravieri et al., 2014). Limitation in primer design and amplification bias could result in an underestimation of sequence diversity of 16S rDNA amplification libraries.

Figure 2.

The active-(micro)biome of Genlisea traps contains 92 preferentially entrapped genera. Relative abundance, frequency of appearance in samples and relative fold change of abundance in trap vs. leaf are shown. Definition of preferentially trapped genera can be found in the legend of Figure 1. ∞ indicates trap exclusive presence.

Our comparative data indicate that the prey spectrum of the uniform G. hispidula traps is less diverse than that of the dimorphic G. nigrocaulis traps, although under our cultivation conditions the microfauna composition was likely homogeneous (Figures 1C,D). In G. nigrocaulis traps, we detected 31 out of the 32 preferentially entrapped metazoans, except for the polychaete worm Capitella. Interestingly, this worm was repeatedly abundant in the filiform traps of G. hispidula, although only 17 out of the 32 metazoan genera occurred there. This corroborates the hypothesis that different Genlisea species may prefer different prey (Studnicka, 1996) or are of different attractivity for potential prey species. Nevertheless, both types of Genlisea traps captured prey of different phyla which are abundant in soil.

To test the effectiveness of our stringent mapping approach, the bacterial composition of Genlisea samples was further analyzed in comparison with published metatranscriptome datasets for various environments including soil, creek, lake, feces, marine water body and marine sediments (Table S1, Figure S1A). As expected, clustering analysis based on abundance of all bacterial taxa indicates that Genlisea samples are more similar to creek, soil, and lake samples than marine sediment, marine water or feces samples (Figure S1B). The relationship between environmental samples using our taxonomy assignment comes in line with the output from the QIIME pipeline (Caporaso et al., 2011). Notably, variation in taxonomic structures between Genlisea samples is higher than other environmental sample groups, except for marine water samples (Figure S1B). In spite of this remarkably dynamic composition, Genlisea traps from same species are more similar to each other and differentiation between Genlisea samples across sampling season is not evident from the cluster dendrogram.

Given that plant root microbiomes vary by soil type and plant species (Haichar et al., 2008; Bulgarelli et al., 2012; Turner et al., 2013; Ofek-Lalzar et al., 2014; Cardinale et al., 2015), a direct comparison with root microbiota and/or rhizosphere of other terrestrial plants might not be meaningful. Nevertheless, following interesting findings are noteworthy in Genlisea-associated bacteria. (i) Similar to microbiota in Arabidopsis' root (Bulgarelli et al., 2012), other plant rhizospheres or bulk soil (Turner et al., 2013), we identified Proteobacteria as the dominant bacterial phylum (from 54.9 to 64.2% bacterial reads) in Genlisea samples (Figure S2). However, Rhodospirillaceae represent the majority (35.9% bacterial reads, 55.9% Proteobacteria reads) in G. nigrocaulis traps, whereas these bacteria are largely underrepresented in G. hispidula traps and Genlisea leave samples (from 0.8 to 6.9% bacterial reads). Within this purple non-sulfur bacterial family, the chemoheterotrophs include the facultative anaerobic genera Skermanella, Telmatospirillum and the strictly aerobic and microoxic genera Magnetospirillum are mainly found in Genlisea samples. (ii) In Proteobacteria phylum, the acetic acid bacterium Asaia and several genera in plant growth-promoting Rhizobiales are highly enriched in G. hispidula traps and Genlisea leave samples. The abundant Asaia genus (from 6.4 to 17.8% bacterial reads) has recently recognized as bacterial symbionts of various insects (Crotti et al., 2009). (iii) Surprisingly, Planctomycetes and Verrucomicrobia, which contain few cultured representatives and are poorly understood, are highly abundant in Genlisea traps but are mostly depleted (compared to bulk soil and rhizosphere) in root-associated bacteria of Arabidopsis and rice (Lundberg et al., 2012; Edwards et al., 2015). Verrumimicrobia are more abundant than Planctomycetes in G. nigrocaulis traps (24.9 and 4.2% bacterial reads, respectively). The opposite is found in G. hispidula traps with 7.2 and 18.7% bacterial reads, respectively (Figure S2). (iv) A depletion in abundance of Acidobacteria and Firmicutes in Genlisea traps, as compared to Genlisea leaves, suggests preferences of protozoa predators in the trap. However, belonging to Acidobacteria phyla, Acidobacterium and Candidatus Solibacter in Genlisea trap's active-microbiome apparently use complex carbon sources and are well equipped to tolerate low-nutrient conditions and fluctuations in soil hydration (Ward et al., 2009).

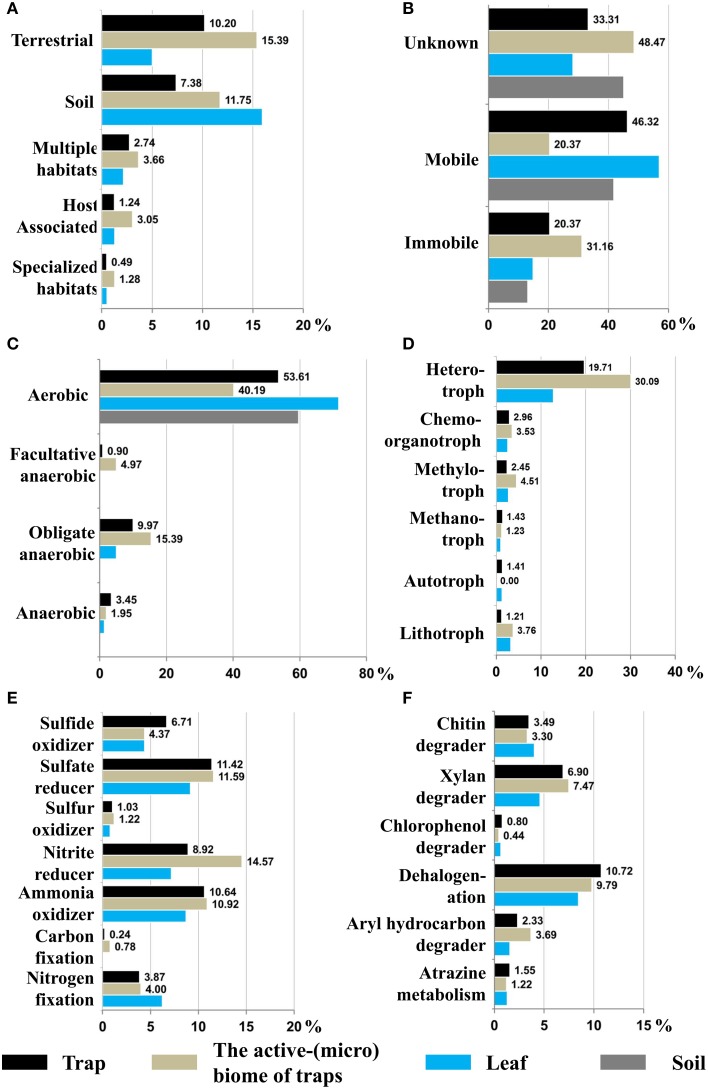

To provide an additional level of functional understanding of the bacterial active-microbiome of Genlisea traps (trap-enriched set), available phenotype information of identified genera from the METAGENassist database (Arndt et al., 2012) was employed. This data suggest that free-living bacteria from terrestrial (10.2%) and soil (7.4%) habitats are dominant in Genlisea traps, while so-called host associated bacteria comprised only 1.2% of trap residents (Figure 3A). Interestingly, among the bacterial active-microbiome of Genlisea traps, the proportions of host-associated and habitat-specific bacteria were increased to 3 and 1.3%, respectively. Of the entrapped bacteria 46.3% were motile and 20.4% were non-motile; among the preferentially trap-enriched bacteria 31.2% were not motile (Figure 3B). So far, several contradictory hypotheses have been published regarding active (Meyers-Rice, 1994; Studnicka, 2003a,c) or passive trapping (Barthlott et al., 1998; Adamec, 2003; Płachno et al., 2005; Plachno and Wolowski, 2008) in Genlisea. The presence of immobile and free-living microbes in Genlisea traps was previously considered as evidence for the hypothesis of an actively drawing bacteria into Genlisea rhizophylls systems (Studnicka, 2003a). Virtually no measurable water flow and lacking bifid glands for water pumping, as occur in Utricularia (Adamec, 2003), rather suggest a passive invasion via a liquid turn-over to explain trapping of immobile bacteria in Genlisea.

Figure 3.

Phenotype profiling of bacterial communities between Genlisea trap samples vs. Genlisea leaves or soil samples. Phenotype information of habitat (A), mobility (B), oxygen requirement (C), energy resources (D), and metabolisms (E,F) was extracted from the METAGENassist database.

Studnicka (2003b) postulated that Genlisea plants attract soil microfauna by transiently creating an oxygen-rich area in their rhizophylls. The presence of bacteria with different oxygen requirements in Genlisea traps (Figure 3C) is in accordance with this hypothesis. Although aerobic bacteria are predominant, facultative and obligate anaerobic bacteria were enriched among the preferentially trapped microbes from 0.9 and 9.97 to 4.97% and 15.39%, respectively. Therefore, bacterial commensals might be adapted to anoxia interrupted by periods of high O2. The oxygen concentration was found very small or zero in mature traps of Genlisea by a still unclear mechanism (Adamec, 2007).

Phenotype mapping of energy resources (Figure 3D) revealed that most of trapped bacteria are heterotrophic (19.7%), and that methylotrophic (2.45%) or lithotrophic (1.2%) bacteria were also enriched (Figure 3E). In terms of metabolic activity, Genlisea traps contain small fractions of bacteria with ability for nitrogen (3.87%) or carbon fixation (0.24%). Plant-associated N2 fixation has been considered as a potential source of N for carnivorous plants with pitcher or snapping traps (Prankevicius and Cameron, 1991; Albino et al., 2006). Although N2 fixing bacteria represent up to 16% of the bacterial community in Utricularia traps, N2 fixation contributed less than 1% of daily N gain of Utricularia (Sirova et al., 2014). This limited N2 fixation is likely due to the high concentration of NH4−N in the Utricularia trap fluid, resulting from fast turnover of organic matter. In Genlisea traps, bacterial ammonia oxidizing or nitrite reducing bacteria are abundant with 10.6 and 8.9%, respectively. This suggests a close interaction of nitrifying and denitrifying bacteria in the nitrogen cycling within this microbial community. In rice paddy soils, nitrite oxidizers were abundant in rice roots and its rhizospheric soil, however ammonia oxidizers were dominant in surface soil (Ke et al., 2013). Furthermore, in Genlisea rhizophylls, there are several bacteria groups with various degrading capacity (Figure 3F), including dehalogenation (10.7%), chitin degradation (3.49%), and xylan degradation (6.9%).

Contribution of microbial mRNA to the Genlisea trap meta-transcriptome

With a glimpse of mechanistic understanding of the trap microbiomes from the METAGENassist database, we further explored the contribution of microbes to Genlisea carnivory by studying mRNA transcripts of traps. The metatranscriptome of each G. nigrocaulis mRNA-seq dataset was de novo assembled and the contigs containing ribosomal RNA and Genlisea transcripts were filtered out, resulting in a set of 31,710 non-plant transcripts (51.2 Mbp). The main fraction of non-plant transcripts ranging from 1500 to 8000 bp (12,564 contigs, 27.9 Mbp) was analyzed. A total of 10,518 transcripts had significant BLAST hits (E ≤ 1.0E-3) in the NCBI protein reference database (Tables S2, S3). Of these, 10,501 transcripts could be taxonomically assigned by the LCA algorithm in MEGAN (minimal blast bit score of 50). The highest percentage of top blast hits came from metazoan species (73.6%) including Arthropoda (20.2%), Mollusca (12.8%), Nematoda (2.6%), probably indicating that Genlisea plants lack of voracious mechanisms to kill trapped large-sized preys. Interestingly, green algae, bacteria, Amoebozoa and Alveolata species contribute to 5.7, 4.3, 3.8, and 2.5% respectively, of transcripts of the Genlisea trap microbe transcriptome. In total, 16 out of 19 phyla, which, according to their rRNA, were preferentially enriched in the traps, apparently contribute to the active mRNA meta-transcriptome.

Of the 10,518 microbe transcripts, 6140 transcripts could be annotated (E-value hit filter of 1.0E-6, annotation cutoff of 55), and 1298 transcripts could be further assigned with an enzyme code. The top five KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) pathways of this microbial metatranscriptome include purine metabolism (181 transcripts, 29 enzymes), prokaryotic carbon fixation pathways (57 transcripts, 15 enzymes), pyruvate metabolism (54 transcripts, 17 enzymes), thiamine metabolism (52 transcripts, 1 enzyme as nucleoside-triphosphate phosphatase EC 3.6.1.15) and the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle (48 transcripts, 15 enzymes). In total, only 15 transcripts (1.1% of all EC assigned transcripts) with assigned enzyme codes had a significant best hit from bacterial species, although the proportion of bacterial transcripts is in the same range as those from algae, amoebes, or ciliates. In total, 408 bacterial transcripts having E-value less than 1E-3 and a bit score higher than 50, originated from 300 bacterial species of 214 genera, belonging mainly to the most abundant bacteria phyla Proteobacteria (151 transcripts), Cyanobacteria (76 transcripts) and Firmicutes (75 transcripts).

The enzyme code distribution of the microbial transcriptome showed 33.7% transcripts encoding hydrolases (Tables 2, S2). Main contributors of hydrolases were metazoans (80.1%), Alveolata (8%), green algae (5.7%), and Amoebozoa (1.14%). Especially, phosphatases (EC 3.1.3) are hydrolases of interest because prey likely provides supplemental phosphate to carnivorous plants in poor habitats (Adamec, 1997). High extracellular phosphatase activity was detected in glandular structures of Genlisea traps as well as in Chlamydomonas sp. living inside Genlisea traps (Plachno et al., 2006; Plachno and Wolowski, 2008). We found in the microbial metatranscriptome 86 phosphatases mainly from Metazoa (73 contigs), Alveolata (5 contigs), Chlorophyta (3 contigs), and Amoebozoa (2 contigs). These groups also contribute to the pool of peptidases-encoding transcripts (EC 3.4), with 77.8, 12.3, 6.2, and 1.2%, respectively. Dominant or co-dominant species for the three protist groups in terms of mRNA transcript abundance are Tetrahymena thermophila (204 transcripts, 76.7% transcripts of Alveolata), Volvox carteri f. nagariensis (247 transcripts, 41.2% transcripts of Chlorophyta), Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (196 transcripts, 32.7% transcripts of Chlorophyta), Acanthamoeba castellanii str. Neff (164 transcripts, 41.6% transcripts of Amoebozoa) and Dictyostelium purpureum (110 transcripts, 27.9% transcripts of Amoebozoa). Given the limited availability of genomic data for unicellular Eukarya, it is more likely that transcripts could have been from soil-borne related species. Among the whole microbiome, T. thermophila which is a voracious predator of bacteria (Eisen et al., 2006), showed 16 enriched GO terms, including hydrolase activity (FDR 1.0E-12), peptidase activity (FDR 4.7E-4), and pyrophosphatase activity (FDR 1.2E-3) confirmed by the Fisher's Exact Test (Table S4). From two green algae, transcripts required for photosynthesis (FDR 3.2E-6 and 3.8E-3 for V. carteri and C. reinhardtii, respectively) were accumulated. Enrichment of transcripts involved in transmembrane transport (FDR 2.7E-3) and other substance transport mechanisms (“single-organism transport,” FDR 3.8E-3) were observed in C. reinhardtii, while V. carteri produced transcripts enriched for generation of precursor metabolites and energy (FDR 2.5E-3) and for stress response (FDR 0.042). No statistically significant enrichment was found comparing transcripts of Acanthamoeba castellanii str. Neff, Dictyostelium purpureum, or of all bacteria species with the whole microbial transcriptome.

Table 2.

List of microbe hydrolases (EC:3.1.3).

| Contig ID | Trap Abundancea | Description | EC | Sequence length | Best hit from blast search | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein ID | E-value | Species name | |||||

| microbe_contig_1801 | 3.93 | Alkaline tissue-non-specific isozyme | EC:3.1.3.1 | 2305 | XP_002919566 | 2.42E-144 | Ailuropoda melanoleucab |

| microbe _contig_9779 | 3.85 | Testicular acid phosphatase | EC:3.1.3.5 | 2202 | NP_001013355 | 4.79E-25 | Danio reriob |

| microbe _contig_25278 | 2.44 | Fructose- - cytosolic-like | EC:3.1.3.11 | 1604 | XP_001007592 | 0 | Tetrahymena thermophila |

| microbe _contig_19528 | 1.62 | Fructose- - chloroplastic-like | EC:3.1.3.23 | 1848 | XP_005821930 | 1.26E-171 | Guillardia theta CCMP2712 |

| microbe _contig_69095 | 0.97 | Phosphatidylinositide phosphatase sac1 | EC:3.1.3.64; EC:3.1.3 | 2234 | XP_007505127 | 0 | Monodelphis domesticab |

| microbe _contig_47809 | 0.86 | 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase fructose- -bisphosphatase isoform x2 | EC:3.1.3.46; EC:2.7.1.105 | 1863 | XP_002404032 | 0 | Ixodes scapularis |

| microbe _contig_36107 | 0.85 | Delta-aminolevulinic acid chloroplastic | EC:4.2.1.24; EC:3.1.3.11 | 1659 | XP_001701779 | 0 | Chlamydomonas reinhardtii |

| microbe _contig_42194 | 0.71 | Phosphatidylinositol -trisphosphate 3-phosphatase tpte2-like isoform x1 | EC:3.1.3.67 | 2420 | XP_005516390 | 3.04E-129 | Pseudopodoces humilisb |

| microbe _contig_30058 | 0.65 | Ser thr phosphatase family protein | EC:3.1.3.2 | 1613 | XP_001027093 | 0 | Tetrahymena thermophila |

| microbe _contig_45862 | 0.58 | Cytosolic purine 5 -nucleotidase isoform x3 | EC:3.1.3.5 | 2114 | XP_008551228 | 0 | Microplitis demolitor |

| microbe _contig_27837 | 0.56 | 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase fructose- -bisphosphatase 1 isoform 2 | EC:3.1.3.46; EC:2.7.1.105 | 1670 | XP_001634601 | 7.44E-66 | Nematostella vectensis |

| microbe _contig_12875 | 0.51 | Enolase-phosphatase e1 | EC:3.1.3.77 | 1797 | XP_001493062 | 2.39E-79 | Equus przewalskiib |

| microbe _contig_91384 | 0.43 | Lysosomal acid phosphatase precursor | EC:3.1.3.2 | 2429 | NP_001013355 | 1.38E-56 | Danio reriob |

| microbe _contig_4435 | 0.39 | Deubiquitinating protein vcip135 | EC:3.1.3 | 2141 | XP_006006858 | 1.58E-165 | Latimeria chalumnaeb |

| microbe _contig_80314 | 0.31 | Inositol-tetrakisphosphate 1-kinase | EC:2.7.1.159; EC:2.7.1; EC:2.7.1.134; EC:3.1.3 | 2112 | XP_007252574 | 3.08E-81 | Astyanax mexicanusb |

| microbe _contig_42454 | 0.29 | Bifunctional polynucleotide phosphatase kinase-like | EC:3.1.3.32; EC:2.7.1.78 | 1958 | XP_004336369 | 9.31E-100 | Acanthamoeba castellanii str. Neff |

| microbe _contig_98753 | 0.27 | 3 (2) -bisphosphate nucleotidase-like | EC:3.1.3.7; EC:3.1.3.57 | 1535 | XP_001690049 | 1.25E-125 | Chlamydomonas reinhardtii |

| microbe _contig_105139 | 0.23 | Phosphoglycolate phosphatase | EC:3.1.3.18 | 1658 | XP_003624218 | 2.93E-104 | Medicago truncatula |

| microbe _contig_1444 | 0.18 | Fructose- - cytosolic-like | EC:3.1.3.11 | 1581 | XP_001007592 | 0 | Tetrahymena thermophila |

Trap abundance was calculated as quantile-normalized expression values (in read per kilobase of exon per million read units) for G. nigrocaulis trap samples.

Sequences were considered as from metazoan species because of lacking genomic reference sequences.

The rhizophyll transcriptome of G. nigrocaulis

Using the annotated G. nigrocaulis genome as reference, the Genlisea rhizophyll trancriptomes were characterized by RNA sequencing analysis in comparison to the corresponding leaf transcriptome. Samples of G. nigrocaulis and G. hispidula from two different seasons were included (Table 1). Relative to leaf samples, 1098 transcripts were differentially transcribed (p < 0.05) in G. nigrocaulis. Hence, 6.4% of all 17,113 G. nigrocaulis genes, corresponding to 8.5% of genes transcribed either in leaves or traps, were differentially expressed. Of the 1098 differentially expressed genes (DEGs), 69 showed an at least two-fold accumulation or reduction of transcripts (Table 3). When comparing trap and leaf samples of G. hispidula by mapping RNA-seq reads of G. hispidula to the genome of G. nigrocaulis, in total 306 differentially expressed genes were found, and 33 of these revealed an at least two-fold different abundance. The difference, compared to the situation found in G. nigrocaulis, could be explained by divergence of transcript sequences between two species, resulting in a less efficient read mapping (Table 1). The G. hispidula genome is allotetraploid and 18 times larger than that of G. nigrocaulis (Vu et al., unpublished).

Table 3.

List of the top differentially expressed genes in Genlisea traps.

| Feature ID | Trap EV | Fold change | P-value | Description | EC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRANSCRIPTION FACTORS AND CELL DIFFERENTIATION | |||||

| Gnig_g5834 | 3.24 | 71.93 | 0.01 | Bel1-like homeodomain protein 2 | – |

| Gnig_g2911 | 3.99 | 54.57 | 0.02 | Homeobox-leucine zipper protein hat14-like | – |

| Gnig_g10300 | 2.83 | 3.12 | 0.03 | Low quality protein: uncharacterized loc101213316 | – |

| Gnig_g6470 | 5.81 | 2.66 | 0.05 | Ethylene-responsive transcription factor erf113 | |

| Gnig_g13661 | 4.93 | 3.05 | 5.51E-4 | Wrky transcription factor 22 | – |

| Gnig_g7714 | 3.78 | 2.51 | 0.03 | Fasciclin-like arabinogalactan protein 11-like | – |

| Gnig_g3900 | 3.59 | 2.13 | 3.72E-3 | Homeobox-leucine zipper protein anthocyaninless 2-like | – |

| Gnig_g11132 | 1.32 | −2.88 | 0.04 | Mitochondrial import inner membrane translocase subunit tim-10 isoform 2 | – |

| Gnig_g3165 | 0.63 | −3.84 | 0.02 | Wuschel-related homeobox 1-like | – |

| Gnig_g6054 | 1.29 | −4.03 | 0.04 | Transcription factor tcp15-like | – |

| Gnig_g8736 | 2.16 | −2.11 | 0.05 | Zf-hd homeobox protein at4g24660-like | |

| DNA REPLICATION, DNA REPAIR MECHANISM, RESPONSE TO OXIDATIVE STRESS | |||||

| Gnig_g10176 | 1.44 | 6.7 | 1.07E-3 | Dna topoisomerase 2-like | EC:5.99.1.3 |

| Gnig_g6886 | 0.34 | 4.2 | 0.03 | Probable atp-dependent rna helicase ddx11-like | – |

| Gnig_g465 | 7.5 | 2.42 | 0.01 | Peroxidase 4 | EC:1.11.1.7 |

| Gnig_g6251 | 2.81 | 26.98 | 0.02 | Gag-pol polyprotein | – |

| Gnig_g7174 | 4.18 | 6.26 | 0.01 | Hypothetical retrotransposon | – |

| Gnig_g9007 | −1.24 | 5.84 | 0.04 | Retrotransposon ty3-gypsy subclass | |

| Gnig_g12518 | 2.29 | 2.09 | 0.02 | Dna primase small subunit-like | – |

| Gnig_g5726 | 0.92 | −2.12 | 0.05 | Cyclin-sds-like | – |

| HORMONE METABOLISM | |||||

| Gnig_g1638 | 4.5 | 7.84 | 0.05 | Gibberellin 20-oxidase | EC:1.14.11.0 |

| TRANSPORT ACTIVITIES | |||||

| Gnig_g2161 | 4.42 | 7.36 | 0.04 | Ammonium transporter 3 member 1-like | – |

| Gnig_g1022 | 5.46 | 4.17 | 0.04 | White-brown-complex abc transporter family | EC:3.6.3.28 |

| Gnig_g12092 | 2.61 | 3.57 | 9.65E-4 | Protein sensitive to proton rhizotoxicity 1-like | – |

| Gnig_g2102 | 3.04 | 2.39 | 0.01 | Probable metal-nicotianamine transporter ysl7-like | – |

| Gnig_g2809 | 4.19 | 2.19 | 0.04 | Mate efflux family protein dtx1-like | |

| Gnig_g2832 | 1.18 | −2.25 | 0.01 | Vacuolar amino acid transporter 1-like | – |

| Gnig_g14845 | 0.99 | −2.3 | 9.78E-3 | Cation h(+) antiporter 15-like | – |

| Gnig_g3612 | 0.85 | −4.34 | 0.02 | Peptide transporter ptr1 | – |

| HYDROLASE ACTITIVITIES | |||||

| Gnig_g53 | 4.38 | 7.07 | 0.01 | Pollen allergen | |

| Gnig_g2873 | 2.46 | 2.34 | 0.03 | Polyphenol oxidase | – |

| Gnig_g11834 | 1.22 | −4.41 | 0.03 | Subtilisin-like protease | EC:3.4.21.0 |

| ENERGY METATBOLISM, MITOCHONDRIA ACTITIVITIES | |||||

| Gnig_g71 | 4.02 | 2.59 | 0.02 | Nadph oxidase | EC:1.6.3.0 |

| Gnig_g2907 | 5.85 | 2.28 | 0.04 | Duf246 domain-containing protein at1g04910-like | – |

| Gnig_g9092 | 6.2 | 2.02 | 1.00E-3 | Cytochrome p450 86b1 | – |

| Gnig_g3919 | 1.99 | 2.22 | 0.02 | Cytochrome p450 | |

| Gnig_g69 | 5.11 | 2.01 | 0.02 | Nadph oxidase | EC:1.6.3.1; EC:1.11.1.7 |

| Gnig_g13497 | 0.95 | −4.2 | 0.02 | Formyltetrahydrofolate deformylase | EC:3.5.1.10; EC:2.1.2.0 |

| Gnig_g10196 | 0.19 | −10.66 | 0.03 | Cysteine desulfurase mitochondrial | |

| PHOTOSYNTHESIS OR CHLOROPLAST ACTIVITIES | |||||

| Gnig_g8373 | −0.05 | 56.93 | 0.04 | Ribulose- -bisphosphate carboxylase oxygenase large subunit | EC:4.1.1.39 |

| Gnig_g825 | 2.51 | −2.04 | 0.04 | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase chloroplastic-like | – |

| Gnig_g12417 | 3.06 | −2.4 | 0.01 | Lipoxygenase 2 | EC:1.13.11.12 |

| Gnig_g5094 | 0.82 | −2.4 | 0.02 | Uracil phosphoribosyltransferase-like | EC:2.4.2.9 |

| Gnig_g11978 | 0.86 | −2.81 | 0.01 | Uridine kinase -like | EC:2.7.1.48 |

| Gnig_g1617 | 1.33 | −3.08 | 0.04 | Heme-binding-like protein chloroplastic-like | – |

| Gnig_g1973 | 3.07 | −3.13 | 0.03 | Carbonic chloroplastic-like isoform x1 | – |

| Gnig_g15746 | 0.09 | −52 | 0.03 | Photosystem ii 47 kda protein | – |

| OTHER OR UNKNOWN FUCTIONS | |||||

| Gnig_g12094 | 2.42 | 5.65 | 0.05 | Ring-h2 finger protein atl57-like | – |

| Gnig_g9230 | 3.98 | 3.36 | 0.02 | Hypothetical protein POPTR_0011s00710g | |

| Gnig_g13075 | −1.73 | 3.3 | 0.01 | Low quality protein: udp-rhamnose:rhamnosyltransferase 1-like | – |

| Gnig_g5322 | 5.2 | 2.52 | 0.02 | e3 ubiquitin-protein ligase pub23-like | |

| Gnig_g11156 | 1.27 | 2.33 | 0.05 | Ubiquitin conjugating enzyme | EC:6.3.2.19 |

| Gnig_g9986 | 1.23 | 2.21 | 0.04 | Afadin- and alpha-actinin-binding protein a isoform x2 | – |

| Gnig_g7098 | 2.4 | 2.12 | 0.03 | Hypothetical protein POPTR_0001s33000g | |

| Gnig_g2799 | 2.08 | −2 | 0.04 | Conserved hypothetical protein | |

| Gnig_g5356 | 2.1 | −2.14 | 0.04 | PREDICTED: uncharacterized protein LOC100254610 | |

| Gnig_g7417 | 2 | −2.14 | 8.02E-4 | Structural constituent of ribosome | |

| Gnig_g12123 | 0.9 | −2.14 | 0.02 | Hydroxycinnamoyl-coenzyme a shikimate quinate hydroxycinnamoyltransferase | – |

| Gnig_g5731 | 1.86 | −2.26 | 0.04 | Probable inactive receptor kinase at1g48480 | – |

| Gnig_g15181 | 2.52 | −2.34 | 0.03 | ||

| Gnig_g15672 | 1.29 | −2.37 | 2.35E-3 | Low quality protein: promoter-binding protein spl10 | – |

| Gnig_g7001 | 0.96 | −2.42 | 0.04 | Histone acetyl transferase gnat myst 101 | – |

| Gnig_g10961 | 1.04 | −3.16 | 0.01 | Une1-like protein | |

| Gnig_g5918 | 1.03 | −3.24 | 0.05 | Probable gpi-anchored adhesin-like protein pga55 | |

| Gnig_g8882 | 1.1 | −3.42 | 9.24E-3 | Probable serine threonine-protein kinase rlckvii-like | – |

| Gnig_g7495 | 0.55 | −4.1 | 0.04 | e3 ubiquitin-protein ligase ring1-like isoform 1 | |

| Gnig_g10879 | 0.3 | −12.68 | 1.66E-3 | PREDICTED: uncharacterized protein YNL011C | – |

| Gnig_g13974 | 3.32 | −46.21 | 0.01 | Tetratricopeptide repeat-like superfamily protein | |

| Gnig_g9460 | 0.02 | −69.06 | 0.03 | Kinesin-1-like | – |

| Gnig_g8274 | 0.33 | −137.05 | 0.02 | Desiccation-related protein pcc13-62-like | – |

Among the 69 most differentially expressed genes, GO term annotations in either “biological process”, “molecular function” or “cellular component” could be assigned to 63 genes. Comparison of the biological processes represented by the genes with up- or down regulated expression between G. nigrocaulis traps and leaves indicates a switch from photosynthesis and chloroplast activities in leaves toward respiratory and mitochondrial activities in traps (Table 3). In chlorophyll-free rhizophylls, we observed a down-regulation of photosystem II protein (Gnig_g15746) and 6 other genes working in chloroplast (Gnig_g825, Gnig_g12417, Gnig_g5094, Gnig_g11978, Gnig_g1617, and Gnig_g1973). The only strongly up-regulated chloroplast gene encodes the large subunit of ribulose-biphosphate carboxylase oxygenase (Rubisco, Gnig_g8373), which participates in CO2 fixation in the Calvin cycle. On the other hand, two cytochrome P450 (Gnig_g9092, Gnig_g3919) and two NADH oxidases (Gnig_g71, Gnig_g69), which contribute to generate ATP via the respiratory pathway, were up-regulated. Interestingly, NADH oxidases are probably used to generate superoxide and further reactive oxygen species for prey digestion in Genlisea traps (Albert et al., 2010). Similar to other higher plants (Mittler et al., 2004), in response to oxidative stress, Genlisea trap cells display a high expression level of cytochrome P450 (Gnig_g9092, Gnig_g3919), peroxidase (Gnig_g465). Oxidative stress, as shown in C. reinhardtii, confers translational arrest of Rubisco (Cohen et al., 2005). This may explain the high abundance of Rubisco (Gnig_g8373) transcipts in Genlisea trap cells. Interestingly, in response to DNA damage, DDX11-like RNA helicase (Gnig_g6886), DNA topoisomerase (Gnig_g10176) and DNA primase (Gnig_g12518) together with genes required for retrotransposition (Gnig_g6251, Gnig_g7174, and Gnig_g9007) were elevated. A retrotransposition burst can be induced by different endogenous and environmental challenges including oxidative stress in plant (Mhiri et al., 1997) and other systems such as human (Giorgi et al., 2011) and yeast (Ikeda et al., 2001). Under oxidative stress, elevated DNA double strand break (DSB) repair sites at retrotransposon positions and signatures of non-homologous end joining repair (NHEJ) were uncovered in mouse (Rockwood et al., 2004). Surprisingly, the cyclin-SDS (SOLO DANCERS)-like gene (Gnig_g5726) which is involved in DSB repair via homologous recombination (De Muyt et al., 2009) was suppressed in Genlisea traps, suggesting that NHEJ is the main repair mechanism for DSBs in Genlisea trap cells.

It has been suggested that Utricularia traps serve to enhance the acquisition of P rather than of N (Sirová et al., 2003, 2009; Ibarra-Laclette et al., 2011). This was used to explain why N concentrations (both NH4-N and organic dissolved N) in Utricularia traps are consistently high, even in species growing in highly oligotropic waters with low prey-capture rates (Sirova et al., 2014). In G. nigrocaulis traps, however, we detected high up-regulation for ammonium transporter (Gnig_g2161), nitrate transporter (Gnig_g12092), amino acid transporter (Gnig_g1022), and oligopeptide transporter (Gnig_g2102) transcripts. Moreover, three transcription factors (Gnig_g5834, Gnig_g2911, and Gnig_g10300), likely involved in cellular nitrogen metabolism were the most up-regulated genes in Genlisea traps. Likely, Genlisea plants absorb N-nutrients via carnivory. For P-nutrient demand of Genlisea plants, there are four up-regulated genes, of which proteins are predicted to have acid phosphatase activity (EC:3.1.3.2/0), including Gnig_g15303, Gnig_g1090, Gnig_g9666 and Gnig_g2820. Although six (inorganic) phosphate (co)transporters (Gnig_g10119, Gnig_g1924, Gnig_g1927, Gnig_g1929, Gnig_g6455 and Gnig_g6456) were expressed in Genlisea traps, these genes do not show a significant differential expression (Table S5). We speculate that inorganic phosphates were delivered to and actively consumed in leaf cells similarly as in rhizophyll cells. In addition to four acid phosphatases, Genlisea trap cells up-regulate seven other hydrolases (EC:3.1), but only pectinesterase (Gnig_g4571) was predicted to be secreted into extracellular region. Furthermore, the gene Gnig_g53 with similarity to extracellular pollen allergen, a member of the glycoside hydrolase family, was found to be highly up-regulated. The limited number of hydrolases found to be up-regulated, suggests that in Genlisea carnivory requires additional digestive enzymes from entrapped microbes.

Concluding remarks

Metatranscriptomic data of Genlisea traps uncovered the diverse entrapped and alive microbe community including Bacteria, protists of the SAR group (heterokont Stramenopiles, Alveolata, and Rhizaria), green algae, microbial fungi and a large range of minute metazoans. Ribosomal RNA profiling indicates a highly dynamic structure of the trap bacterial community, reflecting their ecological importance mainly as prey of the one-way food web inside Genlisea traps. The enrichment in facultatively anaerobic bacteria suggests an occasionally interrupted anoxia environment in Genlisea digestive chambers. A high amount of superoxide and other reactive oxygen species is likely generated in Genlisea traps for killing prey and stimulates different oxidative stress responses in trap cells.

The opportunistic feeding behavior, to catch and utilize various prey, provides Genlisea plants alternative N- and P- macronutrient sources from microbes. The abundance of bacteria involved in nitrogen cycling (ammonia oxidizing, nitrite reducing and nitrogen fixation) indicates their importance for the gain of N- nutrients. In addition, various transporters for different N- forms such as ammonium, nitrate, amino acids and oligopeptides together with transcription factors involved in cellular nitrogen metabolism are highly up-regulated in Genlisea rhizophylls. Except for acidic phosphatases, only a limited range of Genlisea hydrolases were found up-regulated in the traps, suggesting that Genlisea plants rely on digestive enzymatic systems from microbes. Indeed, various hydrolases were identified from entrapped metazoan microbes, Alveolata protists, green algae and amoeboid protozoa. Among them, the cilliate T. thermophila is a voracious bacterial predator, while green algae, such as C. reinhardtii, seem to stay as commensals or inquilines inside Genlisea traps. A variety of mites, nematodes, rotifers and annelids are similarly entrapped and ingest in turn protozoans until they perish and their corpses serve themselves as nutrient. Further studies using microcosm experiments with less complex microbial community may be interesting to understand contributions of each microbe to the carnivory.

Author contributions

HC and GV conceived and designed the study. HC and GV performed the experiments and analyzed the data. HC and GV wrote the paper with contributions from IS. AP, TS, US, and IS contributed reagents/ materials/ analysis tools. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Birgit Voigt, Thomas Schweder (Ernst-Moritz-Arndt-University, Greifswald) and Frank Oliver Glöckner (Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology, Bremen) for critical reading of the manuscript; Andrea Kunze, IPK Gatersleben for excellent technical assistance. This work was supported by Max-Planck-Institut für Züchtungsforschung and IPK, and a grant of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SCHU 951/16-1) and the European Social Fund (CZ.1.07) to IS.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmicb.2015.00526

References

- Adamec L. (1997). Mineral nutrition of carnivorous plants: a review. Bot. Rev. 63, 273–299. 10.1007/BF02857953 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adamec L. (2003). Zero water flows in Genlisea traps. Carniv. Pl. Newslett. 32, 46–48. [Google Scholar]

- Adamec L. (2007). Oxygen concentrations inside the traps of the carnivorous plants Utricularia and Genlisea (Lentibulariaceae). Ann. Bot. 100, 849–856. 10.1093/aob/mcm182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adlassnig W., Peroutka M., Lendl T. (2011). Traps of carnivorous pitcher plants as a habitat: composition of the fluid, biodiversity and mutualistic activities. Ann. Bot. 107, 181–194. 10.1093/aob/mcq238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert V. A., Jobson R. W., Michael T. P., Taylor D. J. (2010). The carnivorous bladderwort (Utricularia, Lentibulariaceae): a system inflates. J. Exp. Bot. 61, 5–9. 10.1093/jxb/erp349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert V. A., Williams S. E., Chase M. W. (1992). Carnivorous plants: phylogeny and structural evolution. Science 257, 1491–1495. 10.1126/science.1523408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albino U., Saridakis D. P., Ferreira M. C., Hungria M., Vinuesa P., Andrade G. (2006). High diversity of diazotrophic bacteria associated with the carnivorous plant Drosera villosa var. villosa growing in oligotrophic habitats in Brazil. Plant Soil 287, 199–207. 10.1007/s11104-006-9066-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arndt D., Xia J., Liu Y., Zhou Y., Guo A. C., Cruz J. A., et al. (2012). METAGENassist: a comprehensive web server for comparative metagenomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, W88–W95. 10.1093/nar/gks497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badri D. V., Chaparro J. M., Zhang R., Shen Q., Vivanco J. M. (2013). Application of natural blends of phytochemicals derived from the root exudates of Arabidopsis to the soil reveal that phenolic-related compounds predominantly modulate the soil microbiome. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 4502–4512. 10.1074/jbc.M112.433300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker P. A., Berendsen R. L., Doornbos R. F., Wintermans P. C., Pieterse C. M. (2013). The rhizosphere revisited: root microbiomics. Front. Plant Sci. 4:165. 10.3389/fpls.2013.00165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barthlott W., Porembski S., Fischer E., Gemmel B. (1998). First protozoa-trapping plant found. Nature 392, 447–447. 10.1038/330379548248 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berendsen R. L., Pieterse C. M., Bakker P. A. (2012). The rhizosphere microbiome and plant health. Trends Plant Sci. 17, 478–486. 10.1016/j.tplants.2012.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broeckling C. D., Broz A. K., Bergelson J., Manter D. K., Vivanco J. M. (2008). Root exudates regulate soil fungal community composition and diversity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 738–744. 10.1128/AEM.02188-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulgarelli D., Rott M., Schlaeppi K., Ver Loren Van Themaat E., Ahmadinejad N., Assenza F., et al. (2012). Revealing structure and assembly cues for Arabidopsis root-inhabiting bacterial microbiota. Nature 488, 91–95. 10.1038/nature11336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caporaso J. G., Lauber C. L., Walters W. A., Berg-Lyons D., Lozupone C. A., Turnbaugh P. J., et al. (2011). Global patterns of 16S rRNA diversity at a depth of millions of sequences per sample. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 4516–4522. 10.1073/pnas.1000080107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caravieri F. A., Ferreira A. J., Ferreira A., Clivati D., De Miranda V. F. O., Araújo W. L. (2014). Bacterial community associated with traps of the carnivorous plants Utricularia hydrocarpa and Genlisea filiformis. Aquat. Bot. 116, 8–12. 10.1016/j.aquabot.2013.12.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cardinale M., Grube M., Erlacher A., Quehenberger J., Berg G. (2015). Bacterial networks and co-occurrence relationships in the lettuce root microbiota. Environ. Microbiol. 17, 239–252. 10.1111/1462-2920.12686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen I., Knopf J. A., Irihimovitch V., Shapira M. (2005). A proposed mechanism for the inhibitory effects of oxidative stress on Rubisco assembly and its subunit expression. Plant Physiol. 137, 738–746. 10.1104/pp.104.056341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conesa A., Gotz S. (2008). Blast2GO: a comprehensive suite for functional analysis in plant genomics. Int. J. Plant Genomics 2008, 619832. 10.1155/2008/619832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crotti E., Damiani C., Pajoro M., Gonella E., Rizzi A., Ricci I., et al. (2009). Asaia, a versatile acetic acid bacterial symbiont, capable of cross-colonizing insects of phylogenetically distant genera and orders. Environ. Microbiol. 11, 3252–3264. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.02048.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Muyt A., Pereira L., Vezon D., Chelysheva L., Gendrot G., Chambon A., et al. (2009). A high throughput genetic screen identifies new early meiotic recombination functions in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Genet. 5:e1000654. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R. C. (2010). Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics 26, 2460–2461. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards J., Johnson C., Santos-Medellin C., Lurie E., Podishetty N. K., Bhatnagar S., et al. (2015). Structure, variation, and assembly of the root-associated microbiomes of rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, E911–E920. 10.1073/pnas.1414592112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen J. A., Coyne R. S., Wu M., Wu D., Thiagarajan M., Wortman J. R., et al. (2006). Macronuclear genome sequence of the ciliate Tetrahymena thermophila, a model eukaryote. PLoS Biol. 4:e286. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison A. M., Gotelli N. J. (2001). Evolutionary ecology of carnivorous plants. Trends Ecol. Evol. 16, 623–629. 10.1016/S0169-5347(01)02269-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison A. M., Gotelli N. J. (2009). Energetics and the evolution of carnivorous plants–Darwin's ‘most wonderful plants in the world’. J. Exp. Bot. 60, 19–42. 10.1093/jxb/ern179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farnsworth E. J., Ellison A. M. (2008). Prey availability directly affects physiology, growth, nutrient allocation and scaling relationships among leaf traits in 10 carnivorous plant species. J. Ecol. 96, 213–221. 10.1111/j.1365-2745.2007.01313.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fedoroff N. V. (2012). Presidential address. Transposable elements, epigenetics, and genome evolution. Science 338, 758–767. 10.1126/science.338.6108.758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleischmann A. (2012). Monograph of the Genus Genlisea. Poole; Dorset; England: Redfern Natural History Productions. [Google Scholar]

- Fleischmann A., Schaferhoff B., Heubl G., Rivadavia F., Barthlott W., Muller K. F. (2010). Phylogenetics and character evolution in the carnivorous plant genus Genlisea A. St.-Hil. (Lentibulariaceae). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 56, 768–783. 10.1016/j.ympev.2010.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi G., Marcantonio P., Del Re B. (2011). LINE-1 retrotransposition in human neuroblastoma cells is affected by oxidative stress. Cell Tissue Res. 346, 383–391. 10.1007/s00441-011-1289-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haichar F. Z., Marol C., Berge O., Rangel-Castro J. I., Prosser J. I., Balesdent J., et al. (2008). Plant host habitat and root exudates shape soil bacterial community structure. ISME J. 2, 1221–1230. 10.1038/ismej.2008.80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huson D. H., Mitra S., Ruscheweyh H.-J., Weber N., Schuster S. C. (2011). Integrative analysis of environmental sequences using MEGAN4. Genome Res. 21, 1552–1560. 10.1101/gr.120618.111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibarra-Laclette E., Albert V. A., Perez-Torres C. A., Zamudio-Hernandez F., Ortega-Estrada Mde J., Herrera-Estrella A., et al. (2011). Transcriptomics and molecular evolutionary rate analysis of the bladderwort (Utricularia), a carnivorous plant with a minimal genome. BMC Plant Biol. 11:101. 10.1186/1471-2229-11-101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda K., Nakayashiki H., Takagi M., Tosa Y., Mayama S. (2001). Heat shock, copper sulfate and oxidative stress activate the retrotransposon MAGGY resident in the plant pathogenic fungus Magnaporthe grisea. Mol. Genet. Genomics 266, 318–325. 10.1007/s004380100560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jobson R. W., Morris E. C. (2001). Feeding ecology of a carnivorous bladderwort (Utricularia uliginosa, Lentibulariaceae). Austral. Ecol. 26, 680–691. 10.1046/j.1442-9993.2001.01149.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jobson R. W., Playford J., Cameron K. M., Albert V. A. (2003). Molecular phylogenetics of Lentibulariaceae inferred from plastid rps 16 intron and trn LF DNA sequences: implications for character evolution and biogeography. Syst. Bot. 28, 157–171. [Google Scholar]

- Ke X., Angel R., Lu Y., Conrad R. (2013). Niche differentiation of ammonia oxidizers and nitrite oxidizers in rice paddy soil. Environ. Microbiol. 15, 2275–2292. 10.1111/1462-2920.12098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kierul K., Voigt B., Albrecht D., Chen X. H., Carvalhais L. C., Borriss R. (2015). Influence of root exudates on the extracellular proteome of the plant growth-promoting bacterium Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB42. Microbiology 161, 131–147. 10.1099/mic.0.083576-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koopman M., Carstens B. (2011). The microbial phyllogeography of the carnivorous plant Sarracenia alata. Microb. Ecol. 61, 750–758. 10.1007/s00248-011-9832-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger J. R., Kourtev P. S. (2012). Bacterial diversity in three distinct sub-habitats within the pitchers of the northern pitcher plant, Sarracenia purpurea. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 79, 555–567. 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2011.01240.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Król E., Płachno B. J., Adamec L., Stolarz M., Dziubiñska H., Trẽbacz K. (2012). Quite a few reasons for calling carnivores ‘the most wonderful plants in the world’. Ann. Bot. 109, 47–64. 10.1093/aob/mcr249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legendre L. (2000). The genus Pinguicula L. (Lentibulariaceae): an overview. Acta Bot. Gall. 147, 77–95. 10.1080/12538078.2000.10515837 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lugtenberg B., Kamilova F. (2009). Plant-growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 63, 541–556. 10.1146/annurev.micro.62.081307.162918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg D. S., Lebeis S. L., Paredes S. H., Yourstone S., Gehring J., Malfatti S., et al. (2012). Defining the core Arabidopsis thaliana root microbiome. Nature 488, 86–90. 10.1038/nature11237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers-Rice B. (1994). Are Genlisea traps active? A crude calculation. Carniv. Pl. Newslett 23, 40–42. [Google Scholar]

- Mhiri C., Morel J. B., Vernhettes S., Casacuberta J. M., Lucas H., Grandbastien M. A. (1997). The promoter of the tobacco Tnt1 retrotransposon is induced by wounding and by abiotic stress. Plant Mol. Biol. 33, 257–266. 10.1023/A:1005727132202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittler R., Vanderauwera S., Gollery M., Van Breusegem F. (2004). Reactive oxygen gene network of plants. Trends Plant Sci. 9, 490–498. 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller K. F., Borsch T., Legendre L., Porembski S., Barthlott W. (2006). Recent progress in understanding the evolution of carnivorous Lentibulariaceae (Lamiales). Plant Biol. (Stuttg.) 8, 748–757. 10.1055/s-2006-924706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ofek-Lalzar M., Sela N., Goldman-Voronov M., Green S. J., Hadar Y., Minz D. (2014). Niche and host-associated functional signatures of the root surface microbiome. Nat. Commun. 5, 4950. 10.1038/ncomms5950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson C. N., Day S., Wolfe B. E., Ellison A. M., Kolter R., Pringle A. (2008). A keystone predator controls bacterial diversity in the pitcher-plant (Sarracenia purpurea) microecosystem. Environ. Microbiol. 10, 2257–2266. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01648.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plachno B. J., Adamec L., Lichtscheidl I. K., Peroutka M., Adlassnig W., Vrba J. (2006). Fluorescence labelling of phosphatase activity in digestive glands of carnivorous plants. Plant Biol. (Stuttg.) 8, 813–820. 10.1055/s-2006-924177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Płachno B. J., Adamus K., Faber J., Kozłowski J. (2005). Feeding behaviour of carnivorous Genlisea plants in the laboratory. Acta Bot. Gall. 152, 159–164. 10.1080/12538078.2005.10515466 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Plachno B. J., Kozieradzka-Kiszkurno M., Swiatek P. (2007). Functional utrastructure of Genlisea (Lentibulariaceae) digestive hairs. Ann. Bot. 100, 195–203. 10.1093/aob/mcm109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plachno B. J., Wolowski K. (2008). Algae commensal community in Genlisea traps. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 77, 77–86. 10.5586/asbp.2008.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prankevicius A. B., Cameron D. M. (1991). Bacterial Dinitrogen Fixation in the Leaf of the Northern Pitcher Plant (Sarracenia-Purpurea). Can. J. Bot. 69, 2296–2298. 10.1139/b91-289 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quast C., Pruesse E., Yilmaz P., Gerken J., Schweer T., Yarza P., et al. (2013). The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D590–D596. 10.1093/nar/gks1219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhold-Hurek B., Hurek T. (2011). Living inside plants: bacterial endophytes. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 14, 435–443. 10.1016/j.pbi.2011.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards J. (2001). Bladder function in Utricularia purpurea (Lentibulariaceae): is carnivory important? Am. J. Bot. 88, 170–176. 10.2307/2657137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockwood L. D., Felix K., Janz S. (2004). Elevated presence of retrotransposons at sites of DNA double strand break repair in mouse models of metabolic oxidative stress and MYC-induced lymphoma. Mutat Res. 548, 117–125. 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2004.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rout M. E., Callaway R. M. (2012). Interactions between exotic invasive plants and soil microbes in the rhizosphere suggest that ‘everything is not everywhere’. Ann. Bot. 110, 213–222. 10.1093/aob/mcs061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siragusa A., Swenson J., Casamatta D. (2007). Culturable bacteria present in the fluid of the hooded-pitcher plant Sarracenia minor based on 16S rDNA gene sequence data. Microb. Ecol. 54, 324–331. 10.1007/s00248-006-9205-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirová D., Adamec L., Vrba J. (2003). Enzymatic activities in traps of four aquatic species of the carnivorous genus Utricularia. New Phytol. 159, 669–675. 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2003.00834.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirová D., Borovec J., Èerná B., Rejmánková E., Adamec L., Vrba J. (2009). Microbial community development in the traps of aquatic Utricularia species. Aquat. Bot. 90, 129–136. 10.1016/j.aquabot.2008.07.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sirova D., Santrucek J., Adamec L., Barta J., Borovec J., Pech J., et al. (2014). Dinitrogen fixation associated with shoots of aquatic carnivorous plants: is it ecologically important? Ann. Bot. 114, 125–133. 10.1093/aob/mcu067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skutch A. F. (1928). The capture of prey by the bladderwort. New Phytol. 27, 261–297. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1928.tb06742.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Soltis P. S., Soltis D. E., Wolf P. G., Nickrent D. L., Chaw S. M., Chapman R. L. (1999). The phylogeny of land plants inferred from 18S rDNA sequences: pushing the limits of rDNA signal? Mol. Biol. Evol. 16, 1774–1784. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studnicka M. (1996). Several ecophysiological observations in Genlisea. Carniv. Pl. Newslett. 25, 14–16. [Google Scholar]

- Studnicka M. (2003a). Further problem in Genlisea trap untangled. Carniv. Pl. Newslett. 32, 40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Studnicka M. (2003b). Genlisea traps - A new piece of knowledge. Carniv. Pl. Newslett. 32, 36–39. [Google Scholar]

- Studnicka M. (2003c). Observations on life strategies of Genlisea, Heliamphora, and Utricularia in natural habitats. Carniv. Pl. Newslett. 32, 57–61. [Google Scholar]

- Suen G., Scott J. J., Aylward F. O., Adams S. M., Tringe S. G., Pinto-Tomas A. A., et al. (2010). An insect herbivore microbiome with high plant biomass-degrading capacity. PLoS Genet. 6:e1001129. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner T. R., Ramakrishnan K., Walshaw J., Heavens D., Alston M., Swarbreck D., et al. (2013). Comparative metatranscriptomics reveals kingdom level changes in the rhizosphere microbiome of plants. ISME J. 7, 2248–2258. 10.1038/ismej.2013.119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenkoornhuyse P., Quaiser A., Duhamel M., Le Van A., Dufresne A. (2015). The importance of the microbiome of the plant holobiont. New Phytol. 206, 1196–1206. 10.1111/nph.13312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent O., Weisskopf C., Poppinga S., Masselter T., Speck T., Joyeux M., et al. (2011). Ultra-fast underwater suction traps. Proc. Biol. Sci. 278, 2909–2914. 10.1098/rspb.2010.2292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward N. L., Challacombe J. F., Janssen P. H., Henrissat B., Coutinho P. M., Wu M., et al. (2009). Three genomes from the phylum Acidobacteria provide insight into the lifestyles of these microorganisms in soils. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75, 2046–2056. 10.1128/AEM.02294-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarza P., Yilmaz P., Pruesse E., Glockner F. O., Ludwig W., Schleifer K. H., et al. (2014). Uniting the classification of cultured and uncultured bacteria and archaea using 16S rRNA gene sequences. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 12, 635–645. 10.1038/nrmicro3330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.