Abstract

There is growing evidence that metabolic stressors increase an organism’s risk of depression. Chronic mild stress is a popular animal model of depression and several serendipitous findings have suggested that food deprivation prior to sucrose testing in this model is necessary to observe anhedonic behaviors. Here, we directly tested this hypothesis by exposing animals to chronic mild stress and used an overnight two bottle sucrose test (food ad libitum) on day 5 and 10, then food and water deprive animals overnight and tested their sucrose consumption and preference in a 1h sucrose test the following morning. Approximately 65% of stressed animals consumed sucrose and showed a sucrose preference similar to non-stressed controls in an overnight sucrose test, while 35% showed a decrease in sucrose intake and preference. Following overnight food and water deprivation the previously ‘resilient’ animals showed a significant decrease in sucrose preference and greatly reduced sucrose intake. In addition, we evaluated whether the onset of anhedonia following food and water deprivation corresponds to alterations in corticosterone, epinephrine, circulating glucose, or interleukin-1 beta expression in limbic brain areas. While all stressed animals showed adrenal hypertrophy and elevated circulating epinephrine, only stressed animals that were food deprived were hypoglycemic compared to food deprived controls. Additionally, food and water deprivation significantly increased hippocampus IL-1β while food and water deprivation only increased hypothalamus IL-1β in stress susceptible animals. These data demonstrate that metabolic stress of food and water deprivation interacts with chronic stressor exposure to induce physiological and anhedonic responses.

Keywords: Chronic Mild Stress, Depression, Anhedonia, Interleukin-1β

Introduction

Exposure to major life stressors are associated with the onset of major depression while more recently it has been revealed that individuals suffering from metabolic syndrome also have increased rates of depression. There is growing evidence that stressor exposure promotes obesity and insulin resistance due to the physiological effects of chronically elevated glucocorticoids (e.g. cortisol in humans, corticosterone in laboratory rodents) and both stressor exposure and obesity are associated with elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines that are now known to play an important role in the etiology of depression (Chrousos, 2000; Martinac et al., 2014).

Chronic mild stress (CMS) is a popular rodent model of depression which has high predictive, face and construct validity(Willner, 2005). During CMS, rodents are exposed to a variety of mild stressors over several weeks, and sucrose intake and preference is examined as a measure of anhedonia. Many parameters have been identified that influence anhedonic responses following chronic stress including rat strain (Wu & Wang, 2010), time of sucrose testing (D’Aquila, Newton, & Willner, 1997), social status(Strekalova, Spanagel, Bartsch, Henn, & Gass, 2004), and the presence of context cues (Camp, Remus, Kalburgi, Porterfield, & Johnson, 2012). More intriguing has been the consistent observation that food deprivation within the stress paradigm impacts anhedonic responses (Reid, Forbes, Stewart, & Matthews, 1997). It was first suggested that weight loss due to food deprivation could account for differences in sucrose intake since smaller animals would be expected to drink less sucrose (Matthews, Forbes, & Reid, 1995; Muscat & Willner, 1992; P. Willner, Towell, Sampson, Sophokleous, & Muscat, 1987), however even when correcting for weight differences researchers have found that stressed animals show a decrease in sucrose intake (Muscat & Willner, 1992; Willner, Moreau, Nielsen, Papp & Sluzewaska, 1996). Interestingly, if food deprivation was eliminated or separated by at least 24 hours from the sucrose testing in a chronic stress paradigm then no changes in sucrose intake was observed in stressed animals (Forbes, Stewart, Matthews, & Reid, 1996; Hagan & Hatcher, 1997; Reid et al., 1997), suggesting there may be an interaction between CMS and metabolic stressors to facilitate the onset of depression-like symptoms.

In many CMS paradigms, food and water deprivation is a necessary component because studies utilize a one-hour sucrose preference test to measure anhedonic responses. Overnight food and water deprivation motivates rodents to consume liquid during a limited amount of time during the light cycle where their liquid intake is typically low(Stephan & Zucker, 1972). However, the presence of food and water deprivation prior to sucrose testing may itself act as a stressor that facilitates the anhedonic response. In fact, it has been established that rats that undergo food deprivation have elevated levels of corticosterone(Mcghee, Jefferson, & Kimball, 2009) and adrenocorticotropin hormone (Hanson, Levin, & Dallman, 1997). While some have argued that all animals, including control animals, are food and water deprived, it is well recognized that animals exposed to chronic stress are often more sensitive to future stressors(Jedema, Sved, Zigmond, & Finlay, 1999). For example animals exposed to chronic stress show a sensitized HPA axis response (McGuire, Herman, Horn, Sallee, & Sah, 2010; Pardon, Ma, & Morilak, 2003), and an increase in release of dopamine and norepinephrine following a novel stressor(Gresch, Sved, Zigmond, & Finlay, 1994). Thus, rodents exposed to chronic mild stress may have differential responses to the food and water deprivation that results in changes in sucrose intake compared to control animals.

We have previous demonstrated that animals exposed to acute severe stressors or chronic mild stressor show enhanced brain cytokine production to subsequent stimulation. Elevated inflammatory cytokines in limbic brain areas are potentially critical for the onset of depressive behaviors. The cytokine theory of depression was developed as researchers’ noted that many features of depression are similar to those of sickness-like behaviors that are induced by pro-inflammatory cytokines. It has also been reported that rodents exposed to chronic mild stress show elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines in both plasma and limbic brain regions (Grippo, Francis, Beltz, Felder, & Johnson, 2005), and chronic administration of the proinflammatory cytokine interleukin-1 (IL-1β) into the brain causes a decrease in sucrose preference (Goshen et al., 2008). It is unclear what effect food and water deprivation may have on the production of brain cytokines, particularly in animals exposed to chronic stress that may have sensitized cytokine responses.

Here, we utilized a within subjects design to directly examine the effects of food and water deprivation on anhedonic responses in rodents exposed to CMS. Animals were exposed to CMS and sucrose preference (and total intake) was measured following an overnight sucrose test when food and water is available and during a 1h trial following overnight food and water deprivation. We hypothesized that the stressed animals would show a greater degree of anhedonia following food and water deprivation than when in a satiated state. Additionally, we utilized a between subject design to test if food and water deprivation augments brain IL-1β protein production in limbic brain regions of animals exposed to chronic stress.

Methods

Animals

Adult, male Fischer-344 rats (mean weight=231 grams +/−33.9) were purchased from Harlan Laboratories (Indianapolis, IN). Animals were housed individually in Plexiglas cages (60 × 30 × 24cm) with food and water ab libitum. The animals were kept on a 12:12 hour light/dark cycle (lights on at 0700h). Upon arrival, animals were acclimated to the environment for 7 days, and then handled for three days prior to the onset of the experiment. All animals were handled according to the Animal Welfare Act and The Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The Kent State University Institutional Animal and Care Committee approved all procedures.

Chronic Mild Stress Procedure

Animals underwent 10 days of our chronic mild stress procedure. The procedure is a 5-day protocol with a morning and evening stressor each day. On the first day, animals were placed into decipacone rodent restrainers (Braintree Scientific, Braintree, MA) for 60min and then food deprived overnight (approximately 18h). The following day rodents were placed into an operant chamber (Lafayette Instrument, Layfaette, IN) for 30min and received two shocks (1.5mA; 2s each, ITI 2min). That evening animals were exposed to constant light. On the third morning, animals were placed in a Plexiglas cage for 30min with a piece of filter paper attached to the top with 35μl of predator odor [2,5-dihydro-2,4,5-trimethylthiazoline (TMT), Contech Enterprises Victoria B.C, Canada] applied to the filter paper. At 1400h on day 3, approximately 1L of water was added to the animals’ home cage and was left unchanged for 18h. On the morning of the fourth day, animals underwent foot shock stress (same as described above), and that evening the animals’ sucrose preference was tested without the presence of a stressor. The following morning (day 5) sucrose preference was calculated. This 5-day pattern of stressors was repeated to give 10 total days.

Sucrose Preference Test

A two-bottle, overnight preference test was given to all animals three days prior to the start of the stress regimen to serve as a baseline. Animals were presented with a 1% sucrose solution bottle and a water bottle at 1400h, and the bottles were taken off the following morning (0800h). Sucrose and water levels were measured before and after the sucrose test and a difference score for each solution was recorded. The sucrose preference was determined by taking the amount of sucrose consumed and dividing it by the total amount of liquid consumed. Animals received an overnight sucrose preference test on day 4–5, and day 9–10. On the evening of the 10th day, food and water was removed from a portion of the control and stressed animals and the following morning (day 11) animals were given a two-bottle sucrose test for one hour (from 0800–0900h).

Organ Weight, IL-1β Measurement

Immediately following the one-hour sucrose preference test, animals were sacrificed via decapitation (between 0900–1100h). The brains were removed and the prefrontal cortex, amygdala, brainstem, hippocampus and hypothalamus were dissected out and flash frozen as previously reported in Porterfield (Porterfield, Gabella, Simmons, & Johnson, 2012). The brains were stored at −80° C until tissue processing occurred. Both right and left adrenal glands were removed, cleared of fat, and weighed. The adrenal glands are expressed in ratio to body weight.

Brain tissue was diluted in Iscove’s solution containing 2% aprotinin (250μl for amygdala, prefrontal cortex and hypothalamus and 500μl for hippocampus and brainstem) and homogenized by a sonic dismembrator. The samples were centrifuged at 10,000rpm at 4° C for 10min. The supernatant of each sample was collected, and was processed for IL-1β protein expression using a commercially available ELISA (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). The IL-1β assay was conducted according to the manufacturer’s instruction with two exceptions. The standards were diluted further than instructed to allow the lowest measurement to be approximately 3.9 pg/ml. In addition, the substrate was given an additional 15min (totaling 45min) to incubate. Bradford Assays were conducted for each brain region to determine total protein concentration. The amount of IL-1β was divided by the total amount of protein (obtained from the Bradford assays), to adjust for variation in dissection size.

Plasma Glucose, Corticosterone and Epinephrine Measurements

Glucose was measured using a handheld glucose meter (AlphaTRAK) with glucose strips (AlphaTRAK, #32109-46-50). After decapitation, a small amount of trunk blood was dropped onto the glucose strip, and a reading was collected.

Immediately following decapitation trunk blood was collected in EDTA vaccutainer tubes (BD Pharmigen Franklin Lakes, NJ) and placed on ice during tissue sample collection. Samples were centrifiuged for 10min at 4000rpm, and the plasma was collected and stored at −80° C until appropriate assays were conducted. Plasma corticosterone levels were measured as previously described (Camp et al., 2012). Briefly, the plasma samples were diluted 1:50 and placed in a 70° C water bath for 1 hour. Commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits determined corticosterone (Enzo Life Sciences, Plymouth Meeting, PA) and epinephrine plasma concentrations (Rocky Mountain Diagnostics). Assays were run according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Procedure

Three days prior to the onset of the experiments, all animals had an overnight sucrose preference test to determine their baseline preference. The CMS animals then underwent 10 days of stress and all animals had two additional sucrose preference tests (Day 5 and Day 10). Note, animals had free access to food/water during each overnight sucrose preference test. On the evening of day 10, food and water was removed from the animals’ cages at 1400 hours. The following morning (day 11) animals received a two-bottle, one-hour sucrose preference test. The stressed animals were broken into stress ‘resilient’ versus stress ‘susceptible’ animals based on day 10 drinking preferences. Animals were labeled as ‘susceptible’ if their sucrose consumption on day 10 were two standard deviations lower than the control’s mean sucrose preference, while animals with sucrose preference less than two standard deviations away from controls were labeled as ‘resilient’. Here we found that approximately 65% of the animals were resistant and showed sucrose preferences similar to that of controls. Some animals were sacrificed immediately after the sucrose test, and brains and blood were collected for analysis of IL-1β protein levels.

Statistical Analysis

Repeated measure ANOVAs were used to analyze data that were collected over multiple time points (weight, sucrose preference, sucrose intake) across both treatment (Stress v. Control) and group (Resilient v. Susceptible v. Control). A one-way ANOVA was used to compare sucrose intake, water intake and total consumption on day 11 between groups. In some measures, the two stressed groups (resilient and susceptible) were collapsed because they did not significantly differ from each other (adrenal glands, glucose, epinephrine and corticosterone). A two-way ANOVA was used to compare plasma glucose, adrenal gland hypertrophy, epinephrine, corticosterone, and IL-1β levels. Significance was set at 0.05 for all statistical measures.

Results

Animals that Underwent Chronic Mild Stress Gained Significantly Less Weight than Controls

Animals that underwent chronic mild stress (n=46) gained significantly less weight over the 10 day period as compared to controls (n=33) (Figure 1). Control animals gained weight over the 10 day period, whereas stress animals did not significantly change from their baseline weight. A repeated measures ANOVA found a significant main effect of time [F(1,77)=(25.114, p<0.001], treatment [F(1,77)=4.339, p=.041], and an interaction between time and treatment (Stress V. Control) [F(1,77)=39.484, p<0.001]. Post hoc comparisons found control animals and stressed animals did not differ significantly at baseline, but control animals weighed significantly more on day 5 (t=−2.548, p=0.013) and day 10 (t=−4.124 p<0.001) than stress animals.

Figure 1.

The effect of stress on weight gain over a 10 day period. Fischer rats were exposed to chronic mild stress for 10 days. During these 10 days, stressed animals did not significantly gain weight while control animals weight significantly increased. * Signify significant (p ≤ 0.05) difference from controls

Chronic Mild Stress Animals Had Significantly Lower Sucrose Preference & Intake Compared to controls During Overnight Sucrose Preference Tests

At baseline, control and stressed animals did not significantly differ in sucrose preference. Over the course of the 10 days, stressed animals showed a significantly lower level of preference compared to the control animals (Figure 2A). A repeated measures ANOVA found a significant main effect of time [F (1,77)=20.458, p<0.001], and an interaction of time and treatment [F(1,77)=7.077, p=0.009] on sucrose preference. Post hoc analysis found that stress animals had a significantly lower sucrose preference than control animals on day 10 (t=2.782, p=0.007).

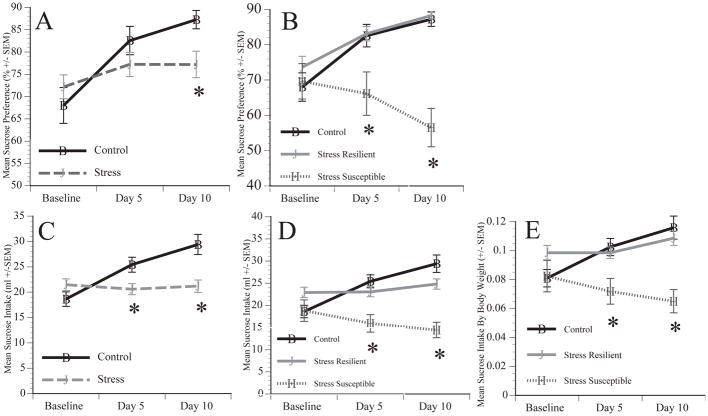

Figure 2.

The effects of stress on sucrose preference and sucrose intake over a 10 day period. Rodents were given an overnight, two-bottle sucrose preference test with free access to food on both day 5 and day 10 to determine sucrose intake and preference. The stressed animals showed a significantly lower sucrose preference on day 10 compared to control animals(A). When stressed animals were broken into resilient versus susceptible, we found that the susceptible animals showed a decrease in sucrose preference compared to both the control and stress resilient animals (B). Sucrose intake followed a similar pattern, where control animals showed a higher intake of sucrose intake over the course of the 10 day stress period than the stress animals (C). Susceptible animals showed a decrease in sucrose intake over time, while the resilient and control animals had similar levels of sucrose intake (D). To ensure that the differences in sucrose intake were not due to weight changes we adjusted sucrose intake by body weight, and our results continue to show that resilient animals and control animals show high levels of sucrose intake whereas the stress susceptible animals showed a decrease over the 10 day period (E). * Signify significant (p ≤ 0.05) difference from controls.

While control animals consumed slightly less sucrose compared to stressed animals at baseline the groups were not significantly different. By day 5 stressed animals consumed significantly less sucrose compared to control animals (Figure 2C). A repeated measures ANOVA confirmed a significant main effect of time [F(1,77)=21.585, p<0.001], an interaction between time and treatment [F(1,77)=23.977, p<0.001], and a main effect of treatment [F(1,77)=4.744, p=0.032]. Control animals increased their sucrose intake over time, whereas the stress animals’ sucrose intake did not change over the 10 days. Post hoc analysis found that control animals had significantly greater sucrose intake on day 5 [ p=0.009] and day 10 [ p<0.001] compared to stress animals.

Chronic Mild Stress Only Decreased Sucrose Preference and intake in Stress Susceptible Animals in Overnight Sucrose Preference Test

Interestingly, upon examining the data it was observed that approximately 35% of chronic stress animals showed a significant decrease in sucrose preference after 10 days. These animals were labeled as stress ‘susceptible’ (n=16) (see methods for criteria used), while the remaining portion of stressed animals (n=30) continued to show high levels of sucrose preference similar to controls and were labeled stress ‘resilient’ (Figure 2B). The control and stress resilient animals increased their sucrose preference over the 10 day period while the stress susceptible animals decrease their sucrose preference. A repeated ANOVA showed a main effect of group (Resilient v. Susceptible v. Control) [ F(1,76)=10.729, p<0.001], and a significant interaction between time x group [F (2,76)=13.185, p<0.001] and a significant main effect of time [F(1,76)=7.552, p=0.007]. Bonferroni post hoc comparisons determined that sucrose preference at baseline were not significantly different between groups, and control and stress resilient animals had significantly greater sucrose preference compared to stress susceptible animals on day 5 (p=0.007 vs. control, p=0.009 vs. stress resilient) and day 10 (p<0.001 vs. control, p<0.001 vs. stress resilient).

Resilient and control animals showed a similar increase in total sucrose consumption over the 10 day period while stress susceptible animals showed a slight decrease in sucrose intake over the 10 days (Fig 2D). A repeated measures ANOVA found that there was a significant effect of time [F(1,76)=5.813, p=0.018], an interaction between group and time [F(2,76)=14.712, p<0.001], and a main effect of group [F(2,76)=9.458, p<0.001]. Post hoc analyses found that the sucrose intake of stress susceptible animals was significantly less than both stress resilient animals (p=0.009) and control (p<0.001) on day 5 and day 10 (p=0.001; p<0.001). In addition, we examined sucrose intake in proportion to body weight to account for variations in weight (Fig 2E). Our results show that even when accounting for differences in weight the same pattern in sucrose intake is observed. Specifically, the stress susceptible animals show a significant decrease in sucrose intake, and control and resilient animals show greater levels of sucrose intake on day 5 and day 10. A repeated measures ANOVA confirmed a significant interaction between group and time [F(2,76)=7.402, p=0.001] and a main effect of group [F(2,76)=7.606, p=0.001]. Post hoc analysis found that there were no significant differences between groups at baseline, but significant differences at day 5 and day 10 [F(2,78)=5.767, p=.005; F(2,78)=10.403, p<0.001]. The stress susceptible animals had significantly lower sucrose intake by weight on both day 5 and day 10 from the control and stress resilient animals (p=0.002, p=0.007, day 5; p=0.001, p=0.003, day 10).

Food and Water Deprivation Significantly Decreases Sucrose Preference in Resilient Animals During One-Hour Sucrose Preference Test

Following overnight water and food deprivation on day 10, resilient animals (n=16) showed a significant decrease in sucrose preference, whereas no significant change in sucrose preference was seen in either the stress susceptible (n=9) or control animals (n=17) (Fig 3A). A repeated-measures ANOVA found a significant main effect of time [F(2,39)=9.623, p=0.004], a main effect of group [F(2,39)=23.856, p<0.001], and an interaction effect [F(2,39)=6.440, p=0.004]. Post hoc analysis confirmed that control animals had significantly greater sucrose preference than the stress susceptible on both day 10 and day 11, and the stress resilient on day 11. While a slight decrease in sucrose preference was observed on day 11 in control animals, this was not statistically significant from their preference on day 10. Similarly, the sucrose preference of the stress susceptible animals did not significantly change from day 10 to day 11. In contrast, food and water deprivation significantly reduced sucrose preference on day 11 in animals previously labeled as stress resilient (t=5.114, p<0.001).

Figure 3.

Effects of overnight food and water deprivation (day 11) on sucrose preference (A) and sucrose intake (B). Animals that underwent the chronic mild stress paradigm were divided into two groups based on their sucrose preference on day 10. Animals with sucrose preference significantly different than controls were labeled as stress susceptible, while animals that had a similar sucrose preference as controls were labeled stress resilient. On the evening of day 10, both control and stressed animals were deprived of food and water. On the morning of day 11, a one-hour, two-bottle sucrose preference test was conducted. Food and water deprivation decreased sucrose intake in both control and stress resilient animals. However, the stress resilient animals showed a greater decrease in sucrose preference and intake compared to controls (A). (B) Control animals had significantly higher levels of sucrose intake as compared to stress susceptible animals and trending toward significance compared to the stress resilient animals. * Signify significant (p ≤ 0.05) difference from controls.

Sucrose intake was also measured following food and water deprivation. A one way ANOVA confirmed groups had consumed significantly different amounts of sucrose [F (2,41)=10.583, p<0.001; See Figure 3B]. Bonferroni post hoc analysis revealed that controls consumed a significantly greater amount of sucrose than stress susceptible (p<0.001) and approached significance for the stress resilient animals (p=0.060). Groups also differed significantly in total liquid intake [F(2,41)=9.035, p=0.001], and Bonferroni post hoc analysis found that the stress susceptible animals had significantly lower total liquid intake than both control (p<0.001) and resilient animals (p=0.035). We evaluated water intake between groups, and no significant differences were found between groups (p=0.632). We observed a significant decrease in sucrose intake and no significant change in water intake demonstrating the decrease in total liquid intake in the stress susceptible animals was due to reduced sucrose intake.

Food and Water Deprivation Increases IL-1β Levels in all Animals in the Hippocampus, and a Significant Increase in Hypothalamus for Stress Susceptible Animals

Immediately following the one-hour sucrose test on day 11, animals were sacrificed and brains were collected to examine changes in IL-1β protein levels in limbic brain regions. Additional control and stressed animals were euthanized at the same time that did not undergo food and water deprivation to assess the interaction of chronic stress with overnight deprivation. We found that food and water deprivation significantly increased IL-1β protein equally in all groups within the hippocampus (Fig 4A). A two-way ANOVA (Group X Deprivation Status) confirmed a main effect of food deprivation [F(1,40)=5.835, p=0.020], but no main effect of stress or interaction in the hippocampus.

Figure 4.

Effect of stress and overnight food & water deprivation on IL-1β protein levels in the hippocampus (A) and hypothalamus (B). Immediately following the one-hour sucrose preference test on day 11, animals were sacrificed and brain tissue was collected. IL-1 protein levels in the hippocampus were significantly higher for animals that underwent food deprivation, but no effect of stress was found. Stress susceptible animals showed a significant increase in IL-1 protein levels following overnight food and water deprivation. * Signify significant (p ≤ 0.05) difference from controls (B) and main effect of food deprivation (A).

Similar to the hippocampus, when animals were not food and water deprived there were no significant differences in IL-1β protein expression in the hypothalamus between groups. However, following the deprivation, we found that the stress susceptible animals had increased IL-1β protein levels while no changes were detected in either the resilient or control groups. A two-way ANOVA found that there was a main effect of food deprivation [F(2,40)=3.332, p=0.046] and group [F(1,40)=4.782, p=0.035], and also a significant interaction between group and deprivation status in the hypothalamus [F(1,40)=6.719, p=.003].

In addition, we examined IL-1β protein expression in the prefrontal cortex, amygdala and brainstem. Two-way ANOVAs found no effect of stress group, food deprivation status or interaction effects in these regions (data not shown).

Chronic Mild Stress Increases Adrenal Gland Weight

The stress susceptible and stress resilient groups were pooled for the analysis of adrenal size and plasma glucose levels as the groups did not significantly differ. The adrenal glands are responsible for the production and release of glucocorticoids following stress. Previous studies have demonstrated that animals that undergo chronic stress have increased adrenal size compared to control animals (Chappell et al., 1986; Garcia et al., 2009). Animals that underwent the chronic mild stress procedure showed a significant increase in adrenal weight as compared to the control groups regardless of food and water status (Figure 5A). A two-way ANOVA (Group: Stress V. Control X Deprivation status: Satiated V. Deprived) found that there was a main effect of group on adrenal size [F(1,42)=24.747, p=0.001], and post hoc analysis confirmed that stressed animals (n=29) adrenals weighed significantly more than control animals (n=18).

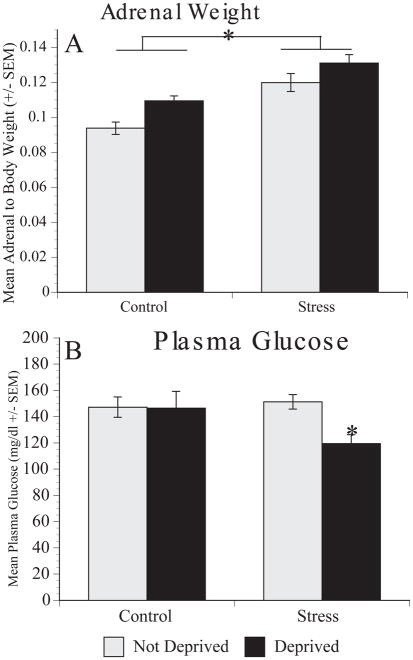

Figure 5.

Effect of stress and food & water deprivation on adrenal size (A) and plasma glucose levels (B). (A) Animals exposed to chronic mild stress showed a significant increase in adrenal weight compared to control groups. (B) Control and stressed animals did not significantly differ in blood glucose levels if food and water were present, however when stressed animals were food deprived their glucose plasma levels decreased. A significant interaction between stress and food deprivation status was obtained. * represents a main effect of stress

In addition, food deprivation and stressor exposure can both alter plasma glucose levels (Landmann et al., 2012; Márquez, Belda, & Armario, 2002). Here, we examined how plasma glucose levels were altered in chronically stressed animals that underwent food and water deprivation. Control (n=24) and stressed (n=32) animals that did not undergo food and water deprivation showed similar levels of plasma glucose (Figure 5B). However, following food and water deprivation, control animals continued to maintain normal levels of glucose while stressed animals showed a significant decrease. A two-way ANOVA (Group: Stress V. Control X Deprivation status: Satiated V. Deprived) confirmed a main effect of food deprivation [F(1,52)=4.300, p=0.043] and a significant interaction between group and deprivation status [F(1,52)=3.910, p=.05] on plasma glucose levels. Post hoc analyses revealed a significant decrease in plasma glucose levels in stressed animals deprived of food and water compared to stressed animals not deprived (p=0.001).

Chronic Mild Stress Increases Plasma Epinephrine In Stress Animals, but Does Not Alter Plasma Corticosterone

Stress susceptible and stress resilient animals were pooled together when analyzing plasma epinephrine and corticosterone as the groups did not significantly differ. Animals exposed to chronic stress showed elevated plasma levels of epinephrine compared to control animals regardless of whether or not they were food and water deprived (Fig 6A). A two-way ANOVA (Group: Stress V. Control X Deprivation status: Satiated V. Deprived) confirmed a main effect of stress [F(1,47)=7.22, p=0.01], and found no significant effect of deprivation status or interaction effect.

Figure 6.

Effect of stress and food and water deprivation on plasma epinephrine (A) and corticosterone (B). Stressed animals showed a significant increase in plasma epinephrine levels while either satiated or after food and water deprivation compared to control animals. However, stressed animals did not significantly differ from control animals in corticosterone levels. * represents a main effect of stress

Plasma corticosterone levels did not significantly differ between groups (Fig 6B), and there was no effect of food deprivation status or interaction effect.

Discussion

In the present study, we found that approximately 35% of animals that undergo chronic mild stress for 10 days show a decrease in sucrose preference and sucrose intake while 65% of animals are resilient and consume sucrose levels similar to control animals. Furthermore, our results demonstrate that food and water deprivation is sufficient to decrease sucrose preference in animals previously resilient to stress-induced changes in sucrose intake. We hypothesized that a larger anhedonic response would be observed in chronic stress animals following food and water deprivation due to a sensitized stress response. While animals exposed to chronic stress showed adrenal hypertrophy and elevated basal levels of circulating epinephrine, there was no evidence that overnight food and water deprivation significantly elevated stress hormones (i.e. corticosterone or epinephrine). Food and water deprivation did cause a significant increase in IL-1β protein levels in the hippocampus but it did so in all animals equally, regardless of whether they were previously exposed to chronic stress. Interestingly, IL-1β in the hypothalamus only increased in stress susceptible animals following food and water deprivation, however, in neither brain area did elevations in brain IL-1β correlate with changes in sucrose intake.

One response that was differentially regulated between control and chronic stress animals following food and water deprivation was circulating levels of glucose where animals exposed to chronic stress were significantly hypoglycemic compared to control animals following overnight food deprivation. Our data support previous reports that a portion of stressed animals are resilient and do not show anhedonia or depressive-like behaviors (Bergström, Jayatissa, Mørk, & Wiborg, 2008; Bergström, Jayatissa, Thykjær, & Wiborg, 2007; Bisgaard et al., 2007; Burke, Davis, Otte, & Mohr, 2005; Christensen, Bisgaard, & Wiborg, 2011; Delgado y Palacios et al., 2011; Henningsen et al., 2009). Researchers using the chronic mild stress paradigm have reported between 30–60% of stressed animals show resiliency (Bergström et al., 2008; Wood, Walker, Valentino, & Bhatnagar, 2010). Bergstrom et al. demonstrated that resilient animals have higher levels of brain derived neurotrophic factor and vascular endothelial growth factor in the hippocampus compared to susceptible animals (Bergström et al., 2008), while others have reported that vulnerable animals show larger adrenal weights or less weight gain compared to resilient animals (Li et al., 2014; Schmidt et al., 2010). We did not observe significant differences in adrenal weight or body weight between the stress susceptible and resilient animals. However, we separated animals into resistant and susceptible groups based on sucrose preference and not other physiological data. While other studies have used sucrose preference or intake as the parameter to determine susceptible and resilient animals, the exact methods have varied. For example one group labeled animals susceptible if their sucrose preference was below 65%. This parameter was chosen because none of the control animal’s displayed sucrose preference below that number(Strekalova et al., 2004). In the present study, animals were labeled as susceptible if their sucrose preference were greater than two standard deviations lower than the controls. Our cut off value was 68%, which was close to the previous studies cut off value. In addition, we did not observe any differences in plasma corticosterone levels in stressed animals (resilient or susceptible) as compared to control animals. Several studies have reported increased basal corticosterone levels following chronic mild stress(Bielajew, Konkle, & Merali, 2002; Garcia et al., 2009; Grippo et al., 2005). However, many of these studies were longer than the current protocol used (3–6 weeks as compared to our 10 days of stress). It is possible that a shift in basal corticosterone would be observed if stressed animals were maintained on this regimen for a longer period.

Food deprivation influences sucrose preference and intake following chronic mild stress (Hagan & Hatcher, 1997; Matthews et al., 1995; Reid et al., 1997). Matthews et al. reported that when food deprivation is eliminated from the paradigm there are no significant changes in sucrose consumption between stressed and control groups (Matthews et al., 1995). Likewise, Hatcher et al. have reported that if food deprivation and sucrose testing is separated by at least 24 hours no such alterations in sucrose intake were observed (Hatcher, Bell, Reed, & Hagan, 1997). Our results demonstrate that a portion of stressed animals show significant reductions in both sucrose preference and intake when sucrose testing occurs without food deprivation, and accounting for differences in body weight between control and stressed animals did not eliminate these differences. This is similar to the findings reported by Willner et al. and others(Willner, Moreau, Nielsen, Papp, Sluzewaska, 1996). In addition, we found that food and water deprivation interacts with stressor exposure to result in anhedonia in previously resilient animals. We are the first to report discrete responses of resilient and susceptible animals to food and water deprivation, which may help explain some of the variability in the literature as some animal strains may show greater resilience to the initial stressor exposure but succumb to the added metabolic stress of food deprivation.

One possible explanation for the greater decrease in sucrose preference following food and water deprivation was that prior stressor exposure sensitized the resilient animals to the metabolic stress of food and water deprivation. Exposure to chronic stress can augment both neurochemical (Nisenbaum, Zigmond, Sved, & Abercrombie, 1991) and behavioral (Zurita, Martijena, Cuadra, Brandão, & Molina, 2000) responses to subsequent exposure to novel stressors. While, our chronic mild stress paradigm did expose animals to overnight food deprivation as part of the stress procedure, the rodents were only exposed to both food and water deprivation on the night of day 10. It is possible that previous exposure to overnight food deprivation reduced the novelty of the stress. However, other studies have found that altering context or other parameters of a stressor is enough to reverse habituation to a stressor(Grissom, Iyer, Vining, & Bhatnagar, 2007).

Surprisingly, we did not observe any significant changes in corticosterone or epinephrine following food and water deprivation to indicate an enhanced stress response. Since blood samples were collected after animals were given access to the sucrose solution, it is possible that consumption of sucrose blunted stress hormone responses to food deprivation (Yoo, Lee, Ryu, & Jahng, 2007; Zanquetta et al., 2006). We did observe a significant drop in blood glucose levels in stressed animals following overnight food and water deprivation that was not observed in non-stressed controls. These data suggest stressed animals were unable to adequately maintain their blood glucose levels. While there were no differences between stress susceptible and resistant animals, hypoglycemia may have contributed to the overall stress burden on chronic stress animals that led to anhedonic responses in previously stress resilient animals. We have since repeated this study without giving animals access to sucrose following the food and water deprivation and observe the same findings, that chronic stress animals are hypoglycemic compared to controls (data not shown). This demonstrates the hypoglycemia observed in chronic stress animals is not due to differential sucrose consumption between stress and control animals, but a physiological difference in the ability to maintain euglycemia.

Elevations in hippocampal IL-1β are thought to lead to the onset of depression (Goshen et al. 2008), however, in this study brain IL-1β levels did not correlate with sucrose preference. If hippocampal IL-1β mediated anhedonic behavior, then one would have expected elevations in IL-1β following stressor exposure in stress susceptible animals and following food and water deprivation in stress resistant animals. We found that chronic stress exposure was not sufficient to elevate hippocampal IL-1β in satiated animals and overnight food and water deprivation increased hippocampal IL-1β in all animals. If hippocampal IL-1β is important in mediating anhedonic responses, then it is unclear why sucrose preference was not significantly reduced in control animals following food and water deprivation unless control animals are less sensitive to the overall effects of IL-1β compared to stressed animals. To our knowledge changes in sensitivity to IL-1β has not be examined in stressed animals. The fact that food and water deprivation selectively increased IL-1β in the hypothalamus of stress susceptible animals is interesting and could explain some reports of chronic stress increasing brain IL-1β. For example, Grippo et al. reported an increase in IL-1β expression in the hypothalamus following chronic mild stress procedure(Grippo et al., 2005); however, the animals were euthanized following overnight food and water deprivation in order to examine sucrose preference. Our data suggest it was not chronic stressor exposure itself that led to the increase in brain IL-1β but the combination with food and water deprivation.

The relationship between hypothalamic IL-1β and depressive behaviors is less studied than hippocampal IL-1β. However, Grippo et al. has reported a negative correlation between hypothalamic IL-1β protein levels and sucrose consumption in rodents exposed to chronic mild stress (Grippo et al., 2005) which suggests that elevated IL-1β protein in the hypothalamus correspond to severity of anhedonia. Likewise, it has been known that IL-1β administration can activate the HPA response(Besedovsky et al., 1991; Matsuwaki, Eskilsson, Kugelberg, Jönsson, & Blomqvist, 2014), which is dysfunctional in depressed patients and may contribute to depressive-behaviors (Barden, 2004). In fact, Goshen & Yirmiya (2009) has proposed that IL-1 may contribute to stressed-induced depression through activation of the HPA system(Goshen & Yirmiya, 2009), implying an important role for IL-1 in the hypothalamus.

In sum, we report that the metabolic challenge of food and water deprivation significantly interacts with previous stressor experience to contribute to anhedonic behavior. Animals exposed to chronic stress are unable to maintain their circulating glucose levels following overnight food deprivation, which may add to their overall allostatic load. While food and water deprivation increased IL-1β protein levels in the hippocampus and selectively in the hypothalamus of stress susceptible animals, IL-1β levels did not correlate with expression of anhedonic behavior. These data add to the growing evidence that metabolic stressors may increase an individual’s risk of depression.

References

- Barden N. Implication of the hypothalamic – pituitary – adrenal axis in the physiopathology of depression. Rev Psychiatr Neurosci. 2004;29(3):185–193. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergström a, Jayatissa MN, Mørk a, Wiborg O. Stress sensitivity and resilience in the chronic mild stress rat model of depression; an in situ hybridization study. Brain Research. 2008;1196:41–52. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergström a, Jayatissa MN, Thykjær T, Wiborg O. Molecular Pathways Associated with Stress Resilience and Drug Resistance in the Chronic Mild Stress Rat Model of Depression—a Gene Expression Study. Journal of Molecular Neuroscience. 2007;33(2):201–215. doi: 10.1007/s12031-007-0065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besedovsky HO, del Rey a, Klusman I, Furukawa H, Monge Arditi G, Kabiersch a. Cytokines as modulators of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 1991;40(4):613–618. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(91)90284-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielajew C, Konkle aTM, Merali Z. The effects of chronic mild stress on male Sprague-Dawley and Long Evans rats: I. Biochemical and physiological analyses. Behavioural Brain Research. 2002;136(2):583–92. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(02)00222-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisgaard CF, Jayatissa MN, Enghild JJ, Sanchéz C, Artemychyn R, Wiborg O. Proteomic Investigation of the Ventral Rat Hippocampus Links DRP-2 to Escitalopram Treatment Resistance and SNAP to Stress Resilience in the Chronic Mild Stress Model of Depression. Journal of Molecular Neuroscience. 2007;32(2):132–144. doi: 10.1007/s12031-007-0025-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke HM, Davis MC, Otte C, Mohr DC. Depression and cortisol responses to psychological stress: a meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30(9):846–56. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camp RM, Remus JL, Kalburgi SN, Porterfield VM, Johnson JD. Fear conditioning can contribute to behavioral changes observed in a repeated stress model. Behavioural Brain Research. 2012;233(2):536–44. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2012.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chappell PB, Smith Ma, Kilts CD, Bissette G, Ritchie J, Anderson C, Nemeroff CB. Alterations in corticotropin-releasing factor-like immunoreactivity in discrete rat brain regions after acute and chronic stress. The Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1986;6(10):2908–14. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.06-10-02908.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen T, Bisgaard CF, Wiborg O. Biomarkers of anhedonic-like behavior, antidepressant drug refraction, and stress resilience in a rat model of depression. Neuroscience. 2011;196:66–79. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrousos G. The role of stress and the hypothalamic ± pituitary ± adrenal axis in the pathogenesis of the metabolic syndrome: neuro-endocrine and target tissue-related causes. International Journal of Obesity. 2000;6:S50–S55. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Aquila PS, Newton J, Willner P. Diurnal Variation in the Effect of Chronic Mild Stress on Sucrose Intake and Preference. Physiology & Behavior. 1997;62(2):421–426. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(97)00042-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado y Palacios R, Campo A, Henningsen K, Verhoye M, Poot D, Dijkstra J, Van der Linden A. Magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy reveal differential hippocampal changes in anhedonic and resilient subtypes of the chronic mild stress rat model. Biological Psychiatry. 2011;70(5):449–57. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes NF, Stewart CA, Matthews K, Reid IANC. Chronic Mild Stress and Sucrose Consumption: Validity as a Model of Depression. Physiology & Behavior. 1996;60(6):1481–1484. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(96)00305-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia LSB, Comim CM, Valvassori SS, Réus GZ, Stertz L, Kapczinski F, Quevedo J. Ketamine treatment reverses behavioral and physiological alterations induced by chronic mild stress in rats. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 2009;33(3):450–5. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goshen I, Kreisel T, Ben-Menachem-Zidon O, Licht T, Weidenfeld J, Ben-Hur T, Yirmiya R. Brain interleukin-1 mediates chronic stress-induced depression in mice via adrenocortical activation and hippocampal neurogenesis suppression. Molecular Psychiatry. 2008;13(7):717–28. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goshen &, Yirmiya Interleukin-1 (IL-1): a central regulator of stress responses. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology. 2009;30(1):30–45. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gresch PJ, Sved AF, Zigmond MJ, Finlay JM. Stress-Induced Sensitization of Dopamine and Norepinephrine Efflux in Medial Prefrontal Cortex in Rat. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1994;63(2):575–583. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.63020575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grippo AJ, Francis J, Beltz TG, Felder RB, Johnson AK. Neuroendocrine and cytokine profile of chronic mild stress-induced anhedonia. Physiology & Behavior. 2005;84(5):697–706. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grissom N, Iyer V, Vining C, Bhatnagar S. The physical context of previous stress exposure modifies hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal responses to a subsequent homotypic stress. Hormones and Behavior. 2007;51:95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagan JJ, Hatcher J. Revised CMS model. Psychopharmacology. 1997;134:354–356. doi: 10.1007/s002130050466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson ES, Levin N, Dallman MF. Elevated corticosterone is not required for the rapid induction of neuropeptide Y gene expression by an overnight fast. Endocrinology. 1997;138(3):1041–7. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.3.4995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatcher J, Bell DJ, Reed T, Hagan JJ. Chronic mild stress-induced reductions in saccharin intake depend upon feeding status. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 1997;11(4):331–338. doi: 10.1177/026988119701100408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henningsen K, Andreasen JT, Bouzinova EV, Jayatissa MN, Jensen MS, Redrobe JP, Wiborg O. Cognitive deficits in the rat chronic mild stress model for depression: relation to anhedonic-like responses. Behavioural Brain Research. 2009;198(1):136–41. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jedema HP, Sved aF, Zigmond MJ, Finlay JM. Sensitization of norepinephrine release in medial prefrontal cortex: effect of different chronic stress protocols. Brain Research. 1999;830(2):211–7. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01369-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landmann EM, Schellong K, Melchior K, Rodekamp E, Ziska T, Harder T, Plagemann A. Short-term regulation of the hypothalamic melanocortinergic system under fasting and defined glucose-refeeding conditions in rats: a laser capture microdissection (LMD)-based study. Neuroscience Letters. 2012;515(1):87–91. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2012.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Wang H, Wang X, Liu Z, Wan Q, Wang G. Differential expression of hippocampal EphA4 and ephrinA3 in anhedonic-like behavior, stress resilience, and antidepressant drug treatment after chronic unpredicted mild stress. Neuroscience Letters. 2014;566:292–7. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2014.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Márquez C, Belda X, Armario A. Post-stress recovery of pituitary-adrenal hormones and glucose, but not the response during exposure to the stressor, is a marker of stress intensity in highly stressful situations. Brain Research. 2002;926(1–2):181–5. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)03112-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinac M, Pehar D, Karlovic D, Babic D, Marcinko D, Jakovljevic M. Metabolic syndrome, activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and inflammatory mediators in depressive disorder. Acta Clin Croat. 2014;53(1):55–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuwaki T, Eskilsson A, Kugelberg U, Jönsson JI, Blomqvist A. Interleukin-1β induced activation of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis is dependent on interleukin-1 receptors on non-hematopoietic cells. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2014;40:166–173. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews K, Forbes NF, Reid IC. Sucrose Consumption as an Hedonic Measure Following Chronic Unpredictable Mild Stress. Physiology & Behavior. 1995;57(2):241–248. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(94)00286-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcghee NK, Jefferson LS, Kimball SR. Elevated Corticosterone Associated with Food Deprivation Upregulates Expression in Rat Skeletal Muscle of the mTORC1 repressor, REDD1. Journal of Nutrition. 2009;139(5):828–34. doi: 10.3945/jn.108.099846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire J, Herman JP, Horn PS, Sallee FR, Sah R. Enhanced fear recall and emotional arousal in rats recovering from chronic variable stress. Physiology & Behavior. 2010;101(4):474–82. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muscat R, Willner P. Suppression of sucrose drinking by chronic mild unpredictable stress: a methodological analysis. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 1992;16(4):507–17. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(05)80192-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nisenbaum LK, Zigmond MJ, Sved aF, Abercrombie ED. Prior exposure to chronic stress results in enhanced synthesis and release of hippocampal norepinephrine in response to a novel stressor. The Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1991;11(5):1478–84. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-05-01478.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardon MC, Ma S, Morilak Da. Chronic cold stress sensitizes brain noradrenergic reactivity and noradrenergic facilitation of the HPA stress response in Wistar Kyoto rats. Brain Research. 2003;971(1):55–65. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02355-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porterfield VM, Gabella KM, Simmons Ma, Johnson JD. Repeated stressor exposure regionally enhances beta-adrenergic receptor-mediated brain IL-1β production. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2012;26(8):1249–55. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid I, Forbes N, Stewart C, Matthews K. Chronic mild stress and depressive disorder: a useful new model? Psychopharmacology. 1997;134(4):365–7. doi: 10.1007/s002130050471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt MV, Scharf SH, Sterlemann V, Ganea K, Liebl C, Holsboer F, Müller MB. High susceptibility to chronic social stress is associated with a depression-like phenotype. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010;35(5):635–43. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephan FK, Zucker I. Circadian Rhythms in Drinking Behavior and Locomotor Acticity of Rats are Eliminated by Hypothalamic Lesions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1972;69(6):1583–1586. doi: 10.1073/pnas.69.6.1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strekalova T, Spanagel R, Bartsch D, Henn Fa, Gass P. Stress-induced anhedonia in mice is associated with deficits in forced swimming and exploration. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29(11):2007–17. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willner P. Chronic mild stress (CMS) revisited: consistency and behavioural-neurobiological concordance in the effects of CMS. Neuropsychobiology. 2005;52(2):90–110. doi: 10.1159/000087097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willner P, Towell a, Sampson D, Sophokleous S, Muscat R. Reduction of sucrose preference by chronic unpredictable mild stress, and its restoration by a tricyclic antidepressant. Psychopharmacology. 1987;93(3):358–364. doi: 10.1007/BF00187257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willner P, Moreau JL, Nielsen CK, Papp M, Sluzewaska A. Decreased Hedonic Responsiveness Following Chronic Mild Stress is Not Secondary to Loss of Body Weight. Physiology & Behavior. 1996;60(1):129–134. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(95)02256-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood SK, Walker HE, Valentino RJ, Bhatnagar S. Individual differences in reactivity to social stress predict susceptibility and resilience to a depressive phenotype: role of corticotropin-releasing factor. Endocrinology. 2010;151(4):1795–805. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu HH, Wang S. Strain differences in the chronic mild stress animal model of depression. Behavioural Brain Research. 2010;213(1):94–102. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo SB, Lee JH, Ryu V, Jahng JW. Ingestion of non-caloric liquid diet is sufficient to restore plasma corticosterone level, but not to induce the hypothalamic c-Fos expression in food-deprived rats. Nutritional Neuroscience. 2007;10(5):261–267. doi: 10.1080/10284150701723859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanquetta MM, Nascimento MEC, Mori RCT, D’Agord Schaan B, Young ME, Machado UF. Participation of beta-adrenergic activity in modulation of GLUT4 expression during fasting and refeeding in rats. Metabolism: Clinical and Experimental. 2006;55(11):1538–45. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2006.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zurita a, Martijena I, Cuadra G, Brandão ML, Molina V. Early exposure to chronic variable stress facilitates the occurrence of anhedonia and enhanced emotional reactions to novel stressors: reversal by naltrexone pretreatment. Behavioural Brain Research. 2000;117(1–2):163–71. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(00)00302-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]