Abstract

Mitochondrial disease can present with a wide range of clinical phenotypes, and knowledge of the clinical spectrum of mitochondrial DNA mutation is constantly expanding. Leigh syndrome (LS) has been reported to be caused by the m.13513G>A mutation in the ND5 subunit of complex I (MT-ND5 m.13513G>A). We present a case of a 12-month-old infant initially diagnosed with tachyarrhythmia requiring defibrillation, subsequent presentation with hypertension and hyponatraemia secondary to renal salt loss and presumed inappropriate ADH secretion. Complex I activity in the muscle tissue was 54%, and mutation load in the muscle and lymphocytes was 50%. This case of Leigh syndrome caused by the m.13513G>A mutation in the ND5 gene illustrates that hyponatraemia due to renal sodium loss and inappropriate ADH secretion and hypertension can be features of this entity in addition to the previously reported cardiomyopathy and WPW-like conduction pattern and that they present additional challenges in diagnosis and management.

Keywords: Arrhythmia, Cardiomyopathy, Complex I, Hypertension, Hyponatraemia, Leigh syndrome, MT-ND5 m.13513G>A

Introduction

Leigh syndrome caused by mutations of genes affecting complex I of the respiratory chain has been increasingly recognized. We describe a case of Leigh syndrome caused by the m.13513G>A mutation in the ND5 subunit of complex I with previously unreported aspects including tachyarrhythmia requiring electrical cardioversion, hypertension and hyponatraemia. This case adds new facets to the spectrum of disease manifestation of the MT-ND5 m.13513G>A mutation.

Case Report

A male infant was born by spontaneous vaginal birth at 39 weeks to a gravid 4 para 4 mother. He was the first child born to a non-consanguineous couple; maternal age at the time of birth was 39 years. The perinatal course was unremarkable. Of interest the infant was diagnosed on antenatal ultrasound with bilateral periventricular cysts, which were confirmed by early postnatal ultrasound and cranial MRI.

At the age of 2 and 3 months, respectively, the infant was admitted to hospital with episodes of broad-complex tachycardia with a left bundle branch block pattern and inferior axis. Both episodes required electrical cardioversion after failed attempts at pharmacological cardioversion. Echocardiography at that time suggested an apical area of possible LV non-compaction/hypertrabeculation (no images available). The infant was commenced on sotalol and subsequently propranolol. Blood pressure at that point of time was within normal limits. There was no family history of structural cardiac disease or arrhythmia and in particular no history of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome (WPW).

Subsequently the infant displayed failure to thrive with weight gradually falling below the third percentile for age; frequent episodes of choking were reported, which were attributed to gastro-oesophageal reflux. Mild hypotonia and inability to sit independently at 12 months suggested developmental delay. Moreover, constipation and new-onset intermittent right-sided exotropia were noted. Ophthalmological examination demonstrated that the infant followed a silent toy; media and fundus were unremarkable. Barium swallow study three days prior to the acute presentation was unremarkable as were electrolytes and blood pressure as documented 10 days prior to admission.

He then presented to our emergency department with a 2-day history of poor feeding and increasing intermittent lethargy and drowsiness. Spontaneous eye opening with response to tactile stimulation but without clearly fixing and a right-sided exotropia were noted. His skin was clammy and peripherally dusky. Capillary refill time was normal. Temperature was 34.5°C; SaO2 in air was 99%; and respiratory rate was 22/min with irregular “sighing” respirations. Heart rate was 133/min and regular. A noninvasive blood pressure of 122/88 mmHg (mean BP 99 mmHg) was obtained (systolic, mean and diastolic blood pressure >95th percentile) (Kent et al. 2007). Cardiac examination revealed a soft ejection systolic murmur with strongly palpable pulses in both upper and lower limbs. His abdomen was soft without palpable masses.

Initial laboratory values (capillary sample, reference range in brackets) showed a serum sodium of 125 mmol/L (135–145 mmol/L), lactate of 3.4 mmol/L (0.6–2.4), glucose of 9.3 mmol/L (2.5–7.1 mmol/L), pH of 7.34 (7.32–7.42), pCO2 of 40 mmHg (35–45), HCO3 of 21.1 mmol/L (20–28) and base deficit of 3.8 mmol/L (–2 to +2); urea and creatinine were within normal range. Urinalysis showed glycosuria, mild proteinuria and a specific gravity of 1.020 (normal range: 1.005–1.030).

Serum osmolality was 257 mmol/kg. Serum lactate was normal on subsequent specimens (0.8–1.2 mmol/L). Blood cultures were negative after 48 h. Nasopharyngeal aspirate for respiratory pathogens, and a stool test for viral pathogens were negative.

A cranial CT performed in the emergency department during the acute presentation excluded an intracranial space-occupying lesion.

The patient developed generalized tonic-clonic seizures 8 h after admission and required intubation and ventilation for prolonged apnoeas following irregular sighing respirations. Hypertension was confirmed once arterial access had been obtained, reaching systolic levels of 120–140 mmHg and diastolic levels between 90 and 100 mmHg (both greater than 10 mmHg above 95th percentile for age).

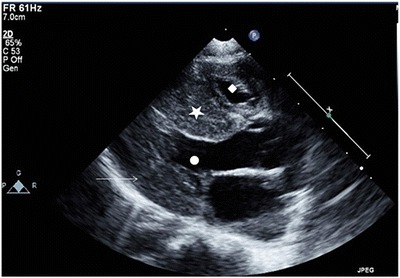

Antihypertensive treatment with amlodipine, captopril and intermittent nifedipine was initiated in addition to regular propranolol, which was continued. A repeat echocardiogram showed marked left ventricular hypertrophy, which had developed precipitously over 2 weeks since the previous echocardiogram (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Echocardiogram: parasternal long-axis view demonstrating septal (filled star) and left ventricular posterior wall thickening (arrow) with crowding of both the left (filled circle) and right ventricular cavity (filled diamond)

The child was extubated on day 6 of admission but required reintubation 2 days later (day 8 of admission) for hypopnoea and respiratory failure. Neurological signs at this point included generalized hypotonia and new-onset bilateral supranuclear facial nerve palsy. Ophthalmology review confirmed the previously noted exotropia and a new-onset downbeat nystagmus with unremarkable retinae and optic nerve discs.

Clinical course

Hyponatraemia reached a minimum serum sodium of 123 mmol/L with maximum urinary sodium concentration of 286 mmol/L and maximum estimated sodium losses of 14 mmol/kg/day based on urine output. Central venous pressure was normal, and a weight gain of 730 g was recorded over 72 h. Serum sodium normalized by day 9 following admission with fludrocortisone at 0.1 mg twice daily, fluid restriction and sodium supplementation. Antihypertensive treatment with amlodipine, captopril and nifedipine was continued.

Serum catecholamines were elevated as were spot urine catecholamines (Table 1). Collection of urinary catecholamines over 24 h demonstrated a similar pattern (values not shown). The remaining endocrine investigations including renin, aldosterone and a toxicology screen were unremarkable (Table 1).

Table 1.

Endocrine investigations, plasma and urine catecholamines and toxicology

| Direct renin | 10.2 uIU/mL | Normal range (5–100) |

| Aldosterone | 400 pmol/L | 300–1,500 |

| Cortisol | Normal | |

| Thyroid function tests | Normal | |

| Plasma free metanephrines | ||

| Metanephrine | 700 pmol/L | <500 |

| Normetanephrine | 1,200 pmol/L | <900 |

| Urine spot catecholamines | ||

| MHMA | 44 μmol/mmol creatinine | <13 |

| HVA | 30 μmol/mmol creatinine | <23 |

| Adrenaline | 534 μmol/mmol creatinine | <90 |

| Noradrenaline | 1,232 μmol/mmol creatinine | <371 |

| Dopamine | 3,140 μmol/mmol creatinine | <2,280 |

| Urine toxicology screen | Negative | |

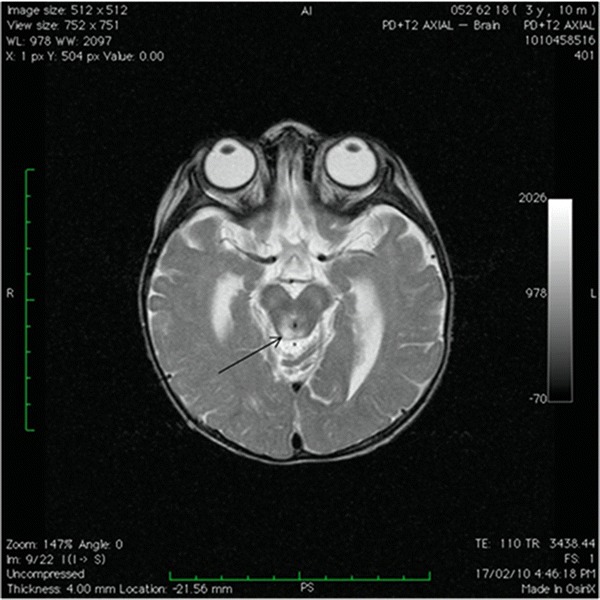

Urinalysis demonstrated marked generalized aminoaciduria, glycosuria and lactic aciduria along with elevated urinary orotic acid and Krebs cycle intermediates. A thoracic-abdominal CT angiography excluded aortic and renal artery stenosis and renal, adrenal and paraaortic masses. Cranial MRI was performed on day 5 of admission and demonstrated symmetrical hyperintensities on T2 weighted images in the tegmental area and in the peri-aqueductal grey matter (see Fig. 2). This was thought to represent changes characteristic of Leigh syndrome, which was confirmed by mtDNA mutation screening. This demonstrated the m.13513G>A mutation in the MT-ND5 gene of complex I; mutation load from leukocytes was 50%. Coenzyme Q10, thiamine, carnitine and idebenone were commenced

Fig. 2.

Cranial MRI: Axial T2 weighted image showing hyperintensities in the peri-aqueductal grey matter (arrow)

Muscle biopsy demonstrated nonspecific lymphoid aggregates without evidence of small- or large-group atrophy. Histochemistry (ATP-ase pH 4.6, NADH, cytochrome oxidase, myodenylate deaminase, phosphorylase) was unremarkable as was immunohistochemistry.

Complex I activity was 54% of control mean value relative to citrate synthase in the muscle; analysis of complex II, II + III, III, and IV and citrate synthase were within normal range. Mutation load in muscle was also 50%. A CSF examination was not performed at the parents’ request.

In view of the repeated unsuccessful extubation attempts, a decision was made to withdraw life-sustaining treatment in agreement with the parents’ wishes, and the infant died 44 days following admission. An autopsy was not performed as per the parents’ requests.

Testing of maternal tissues revealed that the MT-ND5 m.13513G>A mutation was either not present or below the threshold of detection (~1%) in lymphocytes but was reliably detected at an estimated mutation load of 5–10% in urine sediment.

Discussion

Several case series and reports delineating features associated with the MT-ND5 m.13513G>A mutation have been published including presentation as MELAS and Leigh syndrome and recently fatal neonatal lactic acidosis (Chol et al. 2003; Shanske et al. 2008; Ruiter et al. 2007; Van Karnebeek et al. 2011; Sudo et al. 2004; Wang et al. 2008; Monlleo-Neila et al. 2013).

Although a Wolff-Parkinson-White-like conduction pattern, paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia, incomplete right bundle branch block and AV block have been described as a feature of this mutation, documented arrhythmia requiring electrical cardioversion has not been described as the initial manifestation with the MT-ND5 m.13513G>A mutation (Chol et al. 2003; Ruiter et al. 2007; Sudo et al. 2004; Wang et al. 2008; Monlleo-Neila et al. 2013).

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy has been previously associated with this mutation (Chol et al. 2003; Sudo et al. 2004; Wang et al. 2008). In one case this was transient; in a second case a change over time to a dilative type of cardiomyopathy was observed (Chol et al. 2003; Wang et al. 2008). The precipitous change in left ventricular morphology over the course of 2 weeks such as in this current case has also not been previously reported; no trigger such as a viral infection could be identified on routine testing to explain this acute presentation.

A recently reported case with the MT-ND5 m.13513G>A mutation presented with gastro-oesophageal reflux and later paralytic ileus, which is similar to our patient, who had poor weight gain due to frequent and severe episodes of regurgitation and later developed constipation (Monlleo-Neila et al. 2013). We hypothesize that the choking episodes in this current case could have been a manifestation of gastro-oesophageal dysmotility associated with the MT-ND5 m.13513G>A mutation and that this was further complicated by involvement of the brainstem area that is central to coordination of the swallowing reflex (Monlleo-Neila et al. 2013; Saito 2009).

Hyponatraemia has been documented with other mitochondrial disorders such as MELAS and Kearns-Sayre syndrome and in these cases was thought to be secondary to transient or recurrent renal salt loss and inappropriate ADH secretion (SIADH) as evident by a positive fluid balance such as in this current case (Swiderska et al. 2010; Southgate and Penney 2000). Our case also illustrates that differentiation between SIADH and other pathologies such as cerebral salt wasting (CSW) can be difficult in the acute setting in the presence of hypertension and concurrent renal salt wasting (Rivkees 2008).

Hypertension was another presenting feature in this case and has not been described previously with the MT-ND5 m.13513G>A mutation. Overall, hypertension has only rarely been reported as a presenting sign in mitochondrial respiratory chain disorders. Three cases reaching hypertensive crisis level with fatal outcome have been described, one of which was subsequently diagnosed with complex I deficiency (Lohmeier et al. 2007; Pamphlett and Harper 1985; Narita et al. 1998). Similarly to the patient in Lohmeier’s report, our patient presented with signs of autonomic dysfunction and altered vasomotor tone such sweatiness and dusky extremities, which could support the hypothesis of centrally mediated vasomotor dysregulation (Lohmeier et al. 2007; Zelnik et al. 1996). Interestingly, two of these reported cases displayed normal catecholamine levels, whereas in our case levels were elevated.

It seems plausible to assume a neurogenic blood pressure dysregulation as the areas of necrosis in the brainstem comprise the nucleus tractus solitarii, an area central to cardiorespiratory reflex integration (Saito 2009; Lohmeier et al. 2007). This functional area has also been implicated in the characteristic pattern of sighing respirations and post-sigh apnoeas often seen in Leigh syndrome (Saito 2009). Whether the significantly elevated catecholamine levels in our patient are indicative of this central dysregulation remains speculative. Interestingly, the onset of hypertension had coincided with onset of respiratory dysfunction and sighing respirations in the reported cases similarly to ours.

The MT-ND5 m.13513G>A mutation has been reported to cause abnormalities at a low mutation load; in the series reported by Brautbar et al., mutation load was 20–40% and five out of their six patients positive for the mutation had normal complex I activity as had our patient (Brautbar et al. 2008).

In conclusion we report the first documented case of Leigh syndrome caused by the MT-ND5 m.13513G>A mutation presenting with renal salt loss, proximal tubular dysfunction and SIADH in association with rapidly progressive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, WPW-like conduction defect requiring electrical cardioversion and arterial hypertension, further extending the spectrum of presentation of this mutation.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Dr C.J. Turner, paediatric cardiologist, the Children’s Hospital at Westmead, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, for providing additional clinical information.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Conflict of Interest

Marcus Brecht, Malcolm Richardson, Ajay Taranath, Scott Grist, David Thorburn and Drago Bratkovic declare that they have no conflict of interest.

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by the any of the authors.

Consent

Additional informed consent was obtained from the carers of the patient for whom potentially identifying information is included in this article.

Details of the Contributions of Individual Authors

Dr Brecht managed the patient during admission, conceived the article and wrote the first draft of the manuscript; Dr Richardson performed and interpreted serial echocardiograms, provided the echocardiogram and edited the manuscript; Dr Taranath interpreted the cranial MRI, selected the MRI image and edited the manuscript; Dr Grist oversaw mitochondrial DNA analysis and edited the manuscript; Prof Thorburn oversaw and interpreted the respiratory chain enzymology assay and tissue mitochondrial DNA analysis and edited the manuscript; Dr Bratkovic oversaw overall patient management, coordinated testing, discussed and revised the manuscript.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared

Contributor Information

Marcus Brecht, Email: marcus_brecht@web.de.

Collaborators: Johannes Zschocke

References

- Brautbar A, Wang J, Abdenur JE, et al. The mitochondrial 13513G>A mutation is associated with Leigh disease phenotypes independent of complex I deficiency in muscle. Mol Genet Metab. 2008;94(4):485–490. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chol M, Lebon S, Bénit P, et al. The mitochondrial DNA G13513A MELAS mutation in the NADH dehydrogenase 5 gene is a frequent cause of Leigh-like syndrome with isolated complex I deficiency. J Med Genet. 2003;40:188–191. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.3.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent AL, Kecskes Z, Shadbolt B, Falk MC. Blood pressure in the first year of life in healthy infants born at term. Pediatr Nephrol. 2007;22(10):1743–1749. doi: 10.1007/s00467-007-0561-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohmeier K, Distelmaier F, van den Heuvel LP, et al. Fatal hypertensive crisis as presentation of mitochondrial complex I deficiency. Neuropediatrics. 2007;38:148–150. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-985903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monlleo-Neila L, Toro MD, Bornstein B, Garcia-Arumi E, Sarrias A, Roig-Quilis M, Munell F. Leigh syndrome and the mitochondrial m.13513G>A mutation: expanding the clinical spectrum. J Child Neurol. 2013;28(11):1531–1534. doi: 10.1177/0883073812460580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narita T, Yamano T, Ohno M, Takano T, Ito R, Shimada M. Hypertension in Leigh syndrome–a case report. Neuropediatrics. 1998;29(5):265–267. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-973572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pamphlett R, Harper C. Leigh’s disease: a cause of arterial hypertension. Med J Aust. 1985;143(7):306–308. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1985.tb123019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivkees SA. Differentiating appropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion, inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion and cerebral salt wasting: the common, uncommon, and misnamed. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2008;20:448–452. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e328305e403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiter EM, Siers MH, van den Elzen C, et al. The mitochondrial 13513G4A mutation is most frequent in Leigh syndrome combined with reduced complex I activity, optic atrophy and/or Wolff–Parkinson–White. Eur J Hum Genet. 2007;15:155–161. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito Y. Reflections on the brainstem dysfunction in neurologically disabled children. Brain Dev. 2009;31(7):529–536. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanske S, Coku J, Lu J, et al. The G13513A mutation in the ND5 gene of mitochondrial DNA as a common cause of MELAS or Leigh syndrome: evidence from 12 cases. Arch Neurol. 2008;65(3):368–372. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2007.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southgate HJ, Penney MD. Severe recurrent renal salt wasting in a boy with a mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation defect. Ann Clin Biochem. 2000;37:805–808. doi: 10.1258/0004563001900002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudo A, Honzawa S, Nonaka I, Goto Y. Leigh syndrome caused by mitochondrial DNA G13513A mutation: frequency and clinical features in Japan. J Hum Genet. 2004;49(2):92–96. doi: 10.1007/s10038-003-0116-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swiderska N, Appleton R, Morris A, Isherwood D, Selby A. A novel presentation of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion in Leigh syndrome with the myoclonic epilepsy and ragged red fibers, mitochondrial DNA 8344A>G mutation. J Child Neurol. 2010;25(6):782–785. doi: 10.1177/0883073809347594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Karnebeek CD, Waters PJ, Sargent MA, et al. Expanding the clinical phenotype of the mitochondrial m.13513G>A mutation with the first report of a fatal neonatal presentation. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2011;53(6):565–568. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2010.03907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang SB, Weng WC, Lee NC, Hwu WL, Fan PC, Lee WT. Mutation of mitochondrial DNA G13513A presenting with Leigh syndrome, Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome and cardiomyopathy. Pediatr Neonatol. 2008;49(4):145–149. doi: 10.1016/S1875-9572(08)60030-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelnik N, Axelrod FB, Leshinsky E, Griebel ML, Kolodny EH. Mitochondrial encephalomyopathies presenting with features of autonomic and visceral dysfunction. Pediatr Neurol. 1996;14(3):251–254. doi: 10.1016/0887-8994(96)00046-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]