Abstract

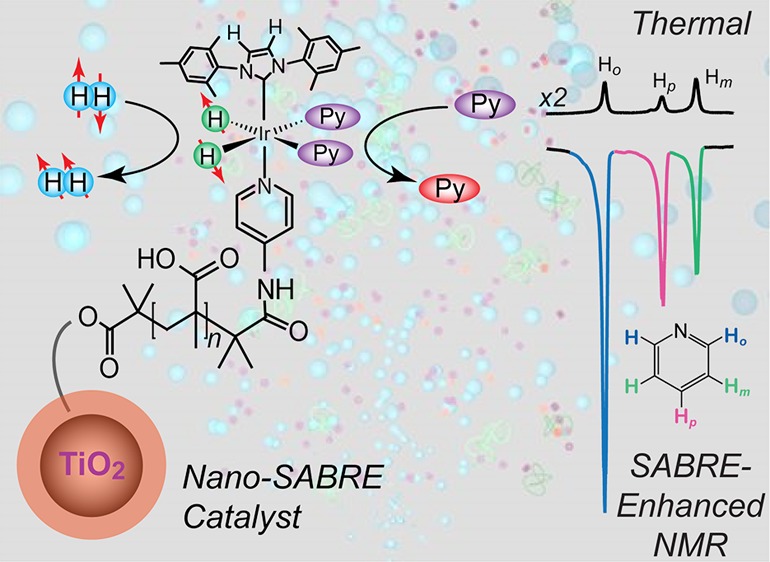

Two types of nanoscale catalysts were created to explore NMR signal enhancement via reversible exchange (SABRE) at the interface between heterogeneous and homogeneous conditions. Nanoparticle and polymer comb variants were synthesized by covalently tethering Ir-based organometallic catalysts to support materials composed of TiO2/PMAA (poly(methacrylic acid)) and PVP (polyvinylpyridine), respectively, and characterized by AAS, NMR, and DLS. Following parahydrogen (pH2) gas delivery to mixtures containing one type of “nano-SABRE” catalyst particle, a target substrate, and ethanol, up to ∼(−)40-fold and ∼(−)7-fold 1H NMR signal enhancements were observed for pyridine substrates using the nanoparticle and polymer comb catalysts, respectively, following transfer to high field (9.4 T). These enhancements appear to result from intact particles and not from any catalyst molecules leaching from their supports; unlike the case with homogeneous SABRE catalysts, high-field (in situ) SABRE effects were generally not observed with the nanoscale catalysts. The potential for separation and reuse of such catalyst particles is also demonstrated. Taken together, these results support the potential utility of rational design at molecular, mesoscopic, and macroscopic/engineering levels for improving SABRE and HET-SABRE (heterogeneous-SABRE) for applications varying from fundamental studies of catalysis to biomedical imaging.

1. Introduction

Conventional NMR and MRI suffer from low detection sensitivity, owing in large part to the weak (∼10–4–10–6) equilibrium nuclear spin polarization attained even in the strongest available magnets. However, in a growing number of systems, hyperpolarization has been shown capable of transiently elevating the nuclear spin polarization far above its thermal equilibrium value. The corresponding increases in NMR detection sensitivity1−6 have enabled access to a range of previously inaccessible experiments from in vivo imaging and spectroscopy of low-concentration species,6,7 to studies of surfaces,8 proteins,2,9,10 and catalysis,3 to low-field11,12 and remotely detected13,14 NMR and MRI. Such NMR hyperpolarization techniques include spin-exchange optical pumping (SEOP) of noble gases5,15 and semiconductors,16,17 dynamic nuclear polarization (DNP),18−20 chemically21 and photochemically induced DNP,2,3,22 and optical nuclear polarization,23,24 among many others.

Whereas most hyperpolarization methods rely on polarization transfer from unpaired electron spins, parahydrogen (pH2)-based approaches harness the pure singlet spin state of parahydrogen (pH2) as the source of nuclear spin order.4 Conventional parahydrogen-induced polarization (PHIP)25−27 involves concerted hydrogenation of pH2 across asymmetric unsaturated bonds,28 allowing hyperpolarization to be manifested by nascent magnetically inequivalent 1H pairs or in longer-lived adjacent heteronuclear sites.4,29−35 A promising new PHIP-based approach called signal amplification by reversible exchange (SABRE) was recently pioneered by Duckett and co-workers:36,37 Like conventional PHIP, SABRE utilizes an organometallic catalyst to colocate pH2 and the target molecule to be hyperpolarized. However, SABRE does not require irreversible alteration of unsaturated precursor molecules; instead, spin order is transferred via spin–spin couplings from transiently bound pH2 to target molecules during the lifetime of the complex.4 Although polarization values achieved via SABRE have generally been lower than those attained via other modalities, SABRE is cost-effective, potentially continuous, and scalable. In addition to achieving 1H polarizations of several percent,37 recent progress has included studies of different catalysts and reaction conditions,38,39 low-field spectroscopy and imaging,40,41,12 enhancement of biomedically relevant substrates42 (including in water-containing43−45 and purely aqueous environments45), in situ high-field SABRE45,46 (enhanced via the application of novel pulse sequences47,48), and the creation of 10% polarization on heteronuclear (15N) spins via SABRE in microtesla fields.49

An additional complication for many applications of hyperpolarization is the need to separate the hyperpolarized (HP) agents from auxiliary substances prior to agent use. Such substances—including alkali metals for SEOP,5,15 radicals for DNP,18 and catalysts for PHIP/SABRE4,36−39—are often required to mediate the hyperpolarization process but may also be expensive, toxic, or otherwise incompatible with the experiment. For example, the vastly different physical properties of alkali metals and noble gases enable facile agent separation in SEOP;50−52 in Overhauser DNP, radicals can be immobilized on beds through which target substances flow during hyperpolarization.20,53 In the context of PHIP, Koptyug and co-workers have shown that separable heterogeneous catalysts such as supported metal nanoparticles, despite their expected reliance on nonmolecular hydrogenation mechanisms, can actually lead to a significant fraction of reactions to proceed through effectively “pairwise” addition of pH2—permitting pure HP products to be obtained.54−58 Following in these efforts, SABRE under conditions of heterogeneous catalysis (“HET-SABRE”) was recently demonstrated utilizing a variant of the standard Ir-based NHC-SABRE catalyst immobilized on solid supports (microscale polymer beads).59 Although the resulting NMR enhancements were modest (up to |ε| ∼ 5 at 9.4 T), the catalysts were easily separated from the supernatant liquid and the results demonstrated the general feasibility of the approach while highlighting areas for future improvement.

A common approach in heterogeneous catalysis is to improve the efficiency of catalysts and increase the effective concentration of solvent-accessible, catalytically active sites through rational design (e.g., by increasing the surface-area-to-volume ratio).60−64 Thus, in the present work two new SABRE catalysts were synthesized with nanoscale dimensions by tethering variants of Ir-based NHC organometallic catalysts to TiO2/PMAA (poly(methacrylic acid)) core/shell nanoparticles and PVP (polyvinylpyridine) “comb” polymers, respectively, in order to investigate the possibility of improved SABRE enhancement. Up to |ε| ∼ 40-fold and ∼7-fold 1H NMR signal enhancements were observed for pyridine substrates using the nanoparticle and polymer comb catalyst supports, respectively, following transfer to a 9.4 T NMR magnet. The enhancements are consistent with HET-SABRE from intact nanoscale catalysts, and the catalyst properties are further distinguished from those of homogeneous SABRE by the absence of in situ high-field SABRE effects; the feasibility of HET-SABRE catalyst separation and reuse is also demonstrated. Taken together, these results support the potential utility of rational catalyst design for improving HET-SABRE for a wide range of NMR/MRI applications.

2. Experimental Approach

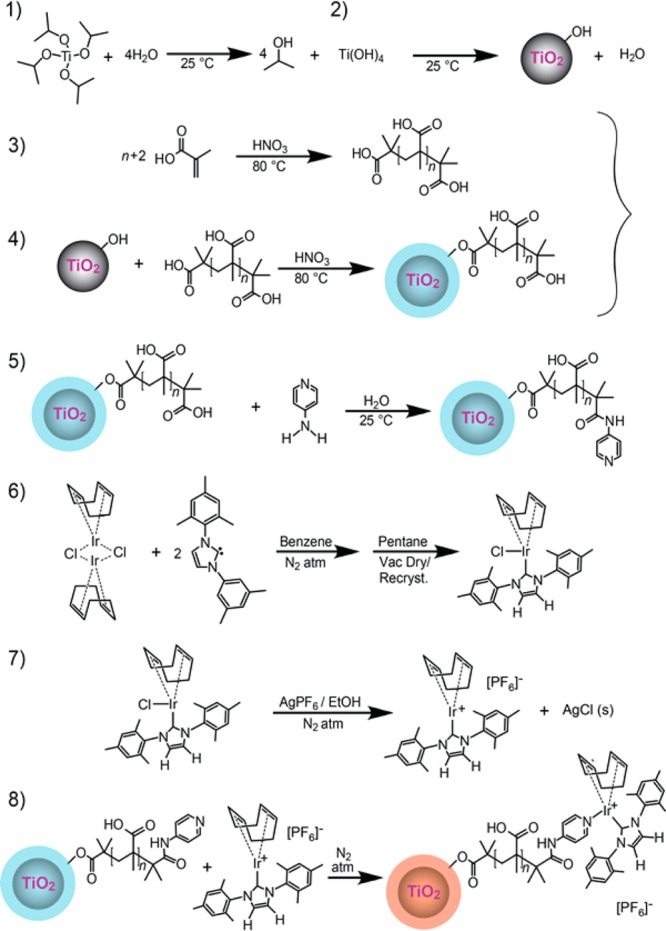

Synthesis of TiO2/PMAA core/shell nanoparticle SABRE catalysts is summarized in Figure 1; additional details concerning SABRE catalyst syntheses and characterization are provided in the Supporting Information. TiO2 cores were chosen not only because they present an easy-to-prepare form of nanoscale supports but also because they are nonmagnetic and catalytic (facilitating shell formation). The procedure for synthesizing the TiO2 cores was adapted from a related approach in ref.65 In step 1, titanium hydroxide is prepared from titanium isopropoxide and water under ambient conditions; Ti(OH)4 will further undergo dehydration condensation (step 2) to form the nanoscale TiO2 cores. Catalyzed by TiO2, methacrylic acid separately undergoes a polymerization (step 3) procedure to give PMAA; the resulting PMAA chains were covalently attached to the TiO2 nanoparticle surfaces, thereby generating an outer shell layer (step 4). The PMAA shells were then functionalized with 4-aminopyridine (step 5) under mild conditions without need for any additional catalysts (as opposed to more traditional methods using organic solvents and higher temperatures66,67). Separately (step 6), the N-heterocyclic carbene complex-based Ir catalyst [abbreviated as IrCl(COD)(IMes)]68—the standard catalyst used in most homogeneous SABRE experiments4,37,39,41−46,48,69—was synthesized according to previously described procedures.59,68 Then, following the approach utilized in our original HET-SABRE catalyst synthesis59,70 (inspired by ref (71)), the above homogeneous catalyst was primed for addition to the solid support (step 7) by reaction with AgPF6 in THF under an Ar atmosphere; AgCl precipitation provides the driving force for Cl– abstraction. The previously prepared surface-modified TiO2/PMAA core–shell nanoparticles were added to the solution within a glovebox (step 8) to yield the completed SABRE nanoparticle catalysts (NPCs).

Figure 1.

Summary of synthetic steps for the preparation of the TiO2/PMAA nanoparticle SABRE catalysts (NPCs). The ratio of aminopyridine/catalyst moieties to polymer strands is expected to be ∼1:1; the final structure is depicted with one possible configuration, with the catalyst moiety bound to a terminal aminopyridine group; aminopyridine/catalyst moieties may also functionalize repeat units. Bare TiO2 NPs, NPs coated/infused with PMAA, and final functionalized NPCs are shown in gray, light blue, and orange/red, respectively. Components are not drawn to scale.

Synthesis of PVP polymer comb SABRE catalysts is summarized in Figure 2. The same [IrCl(COD)(IMes)] homogeneous SABRE catalyst was synthesized, and its Cl– moiety was eliminated as described above. Commercial PVP polymer combs were suspended in ethanol and reacted with the primed (Cl-abstracted) Ir SABRE catalyst within a glovebox to enable covalent linking of the Ir catalytic moieties to the polymer comb support structures. The polymer suspension was dried in the open air prior to characterization to give the final polyvinylpyridine catalysts (PVPCs).

Figure 2.

Summary of the synthesis of the PVP comb polymer SABRE catalysts (PVPCs), shown structurally (top) and schematically (bottom). Components are not drawn to scale.

Catalyst Characterization

Successful immobilization of the Ir complex onto the TiO2/PMAA core/shell NPs and the polymer combs was supported by NMR, AAS, and DLS experiments (see Supporting Information). A strong Ir signal from the intact particles indicated the presence (and hence successful linkage) of Ir on the NPs; according to an estimate based on the AAS results, the Ir complex comprises roughly 25% of the total nano-SABRE catalyst particles by weight. AAS on the filtrate solution (resulting from the final NP washing step) did not detect the presence of Ir within the sensitivity limits of the experiment, before or after catalyst activation in the presence of H2. According to the information provided by 1H NMR, the average polymerization degree of the PMAA shell outside of the titanium dioxide core is ∼20 monomer units. DLS characterization of the two intact (completed) nanosized SABRE catalysts (NPCs and PVPCs) found average particle size/hydrodynamic radii of ∼8 and ∼57 nm, respectively; DLS measurement of the initial TiO2/PMAA core–shell particles indicates an average hydrodynamic radius of ∼6.4 nm. Supplemental molecular dynamics (MD) and quantum chemistry calculations were also performed on the shell moieties of the NP catalysts: these simulations showed that the average length of the polymer chain is just over 3 nm. The estimated contribution to the NP diameter of the PMAA shell is therefore roughly ∼6.1 nm (in turn, suggesting an estimated average diameter of the TiO2 cores of roughly ∼6–7 nm). Based on all those calculations, a 100% occupancy of the Ir catalyst moieties on the polymer chains (i.e., in a ∼1:1 ratio) would predict a mass percentage of ∼30% for the Ir catalyst moiety (with respect to the other shell components and ignoring the contribution from the TiO2 core); thus, a ∼25% weight percentage for the Ir catalyst moiety would be consistent with the TiO2 component contributing roughly 10% of the total particle mass.

SABRE NMR Experiments

All NMR experiments were performed on at 9.4 T (400 MHz); ex situ SABRE experiments were performed at ∼100 G within the fringe field of the NMR magnet. pH272 gas bubbling was regulated by a manual flow meter; the gas was delivered to the NMR sample via Teflon tubing. Like the pH2 delivery line, an exhaust line of Teflon tubing was fed through a simple hole in the cap of the NMR tube to maintain constant (near-ambient) overpressure.

3. Results and Discussion

Before a SABRE catalyst can be used, it must first be activated with H2 gas in the presence of excess substrate (e.g., refs (3) and (45)); failure to properly activate the catalyst can result in irreversible loss of catalytic activity.45In situ stopped-flow pH2 bubbling enables the catalyst activation process to be monitored via 1H NMR, particularly through the observation of time-dependent changes to HP hydride resonances. Typical hydride spectra of the nanoscale SABRE catalysts studied here are shown in Figure 3, which may be compared with previous results obtained with homogeneous SABRE catalysts. For example, activation of the standard Ir-IMes homogeneous catalyst gives rise to three characteristically upfield-shifted HP hydride resonances: two transient (typically dispersive) peaks at −12.3 and −17.4 ppm associated with intermediate structures and a strong absorptive peak at −22.8 ppm associated with the final activated catalyst.37,45

Figure 3.

(a) Typical 1H NMR spectrum from the hydride region of PVP comb polymer SABRE catalysts (PVPCs), exhibiting emissive and absorptive character for the three spectral regions of interest; spectrum was acquired in situ during catalyst activation, following ∼330 s of total pH2 bubbling. (b) Selected spectra taken from the same spectral region of TiO2/PMAA core–shell nanoparticle catalysts (NPCs), acquired with varying durations of pH2 bubbling during catalyst activation and use (note the significantly greater spectral complexity). (c) Typical 1H NMR spectrum from the same spectral region of a homogeneous variant of the SABRE catalyst, with 4-aminopyridine bound to Ir in the preactivated structure.59,73 The spectrum was acquired in situ during catalyst activation, following ∼150 s of total pH2 bubbling. (d) Plots showing the decay (normalized integrated NMR signal in magnitude mode) of intermediate species in spectral regions of ∼(−)12.4 ppm and ∼(−)17.2 ppm for the data in (b), along with corresponding data showing the rise of HP Ir-hydride resonances at ∼(−)22.8 ppm—likely indicating the presence of activated catalyst. The trend lines/eye guides are exponential fits. Data points taken at 450 s and earlier were acquired with in situ (high-field) bubbling within the magnet (filled symbols); later points were acquired with ex situ (low-field) bubbling and subsequent sample transfer to the NMR magnet (and thus the ex situ signals may be weaker because of relaxation during sample transit).

In our previous work demonstrating HET-SABRE with microscale SABRE catalysts using polymer bead supports,59 it was difficult to observe any hydride signals—likely the result of both reduced density of catalyst moieties and much larger particle sizes (and hence slower tumbling times and much broader lines). Here, strong HP 1H hydride signals are observed for both the polymer comb SABRE catalysts (e.g., Figure 3a) and the NP catalysts (e.g., Figure 3b): Like the previous Ir-IMes homogeneous catalyst,45 three regions of peaks are observed for both catalysts, with similar average shift values. However, for the polymer comb catalysts the first two peaks are emissive and absorptive (respectively) instead of dispersive. Moreover, greater spectral differences are observed for the NP catalysts: two lines are observed at each of the first two regions near ∼(−)12.4 and ∼(−)17.2 ppm, and a complex multiplet pattern comprising ∼9–10 peaks is observed for the region at ∼(−)22.8 ppm that changes over time (the peaks also appear to reside on a broad baseline). The corresponding hydride region obtained from a similar homogeneous SABRE catalyst [Ir(4-aminopyridine)(COD)(IMes)] (“4AP-cat”)—created via addition of 4-aminopyridine after chloride abstraction (step 7 of Figure 1)73—is shown in Figure 3c. Thus, given the similarity of the spectra in Figure 3b,c, the complex spectral appearance of their hydride regions may originate from the presence of the amine moiety immediately adjacent to the pyridine group tethering the Ir complex to the NP supports (as neither the PVP comb catalysts nor the standard SABRE catalyst possess corresponding amine groups) as well as possible differences in the on/off rates for exchanging ligands for these catalyst species—the subject of future study.

Activation of the SABRE catalysts with pH2 and pyridine involves hydrogenation (and subsequent loss) of the COD moiety, formation of a hexacoordinate Ir complex (here, with ligands expected to comprise the IMes group, two classical hydrides, two exchangeable substrate pyridine groups, and the nonexchangeable pyridine derivative linker group), and concomitant change in the Ir oxidation state from +1 to +3;3,45 solutions of the standard Ir IMes catalyst also undergo a corresponding color change from bright orange-yellow to clear.37 The time dependence of the HP signals from the hydride region of the NP catalyst is shown in Figure 3d, plotted as a function of total pH2 bubbling time (flow rate: ∼20 cm3/min). Simplistic exponential fits of the appearance of signals at the −22.8 ppm region and loss of signals at −12.4 and −17.2 ppm give time constants of 140 ± 50, 300 ± 90, and 200 ± 90 s, respectively—in rough agreement with the activation of the PVP comb catalysts and 4AP-cat as well as the original Ir-IMes SABRE catalyst;45 thus for all of these catalysts, activation should be essentially complete within ∼10–15 min under these experimental conditions.

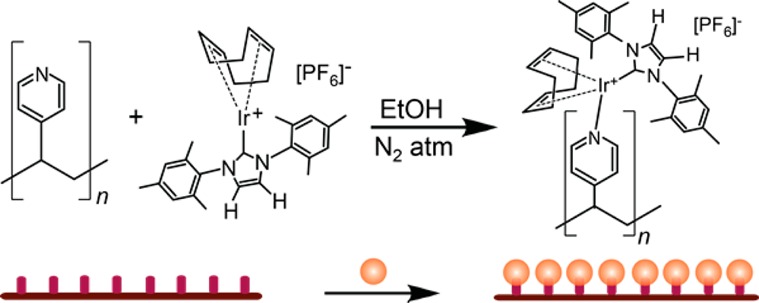

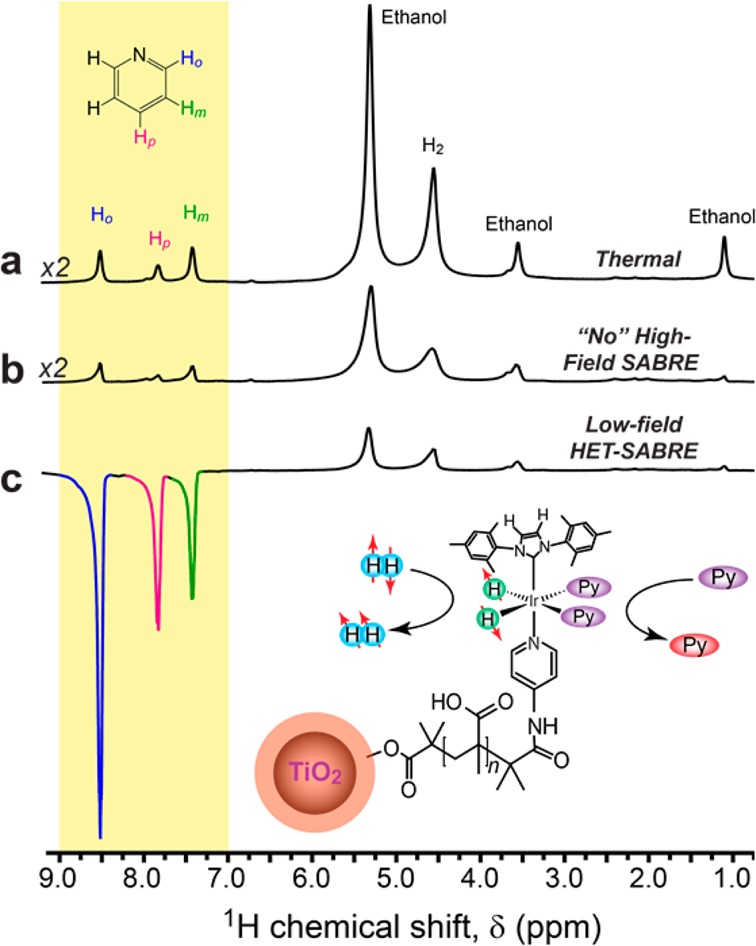

Following activation, the capability of both of the nanoscale catalysts to provide SABRE enhancement was investigated. Results for the polymer comb catalysts (PVPCs, synthesized first) are shown in Figure 4; the same sample from Figure 3a was studied, comprising ∼4 mg of PVPCs (corresponding to an estimated 0.0031 mmol of the Ir complex) dissolved in 400 μL of d6-ethanol along with 0.05 mmol of pyridine substrate (giving a substrate concentration of 125 mM and a substrate to catalyst–moiety ratio of ∼16:1). A typical thermally polarized 1H NMR spectrum from the sample (here, prior to acquisition) is provided in Figure 4a. A spectrum obtained after activation and 30 s of pH2 bubbling (∼93% pH2 fraction) at high field (in situ) is shown in Figure 4b. Unlike the case with most homogeneous SABRE catalysts we have investigated (see below), virtually no high-field SABRE enhancement is observed in the spectrum—with the possible exception of a miniscule emissive peak that may originate from bound pyridine (ortho-H position, ∼8.0 ppm). However, when the sample was removed to allow for 30 s of pH2 bubbling within the weak fringe field (∼100 G) and then rapidly reinserted into the NMR magnet, a HET-SABRE-enhanced 1H NMR spectrum was acquired (Figure 4c). Indeed, the HET-SABRE spectrum is clearly manifested by both the stronger signal and the emissive peaks for the pyridine substrate, whose appearance follows the pattern typically obtained with homogeneous SABRE.37,45,59 Although quantification of the resulting SABRE effects is impeded by relatively poor shim quality (owing to the effects of sample bubbling, rapid sample transfer, etc.), estimated values for the signal enhancement, ε = (Senhanced – Sthermal)/Sthermal (where S is a given integrated spectral intensity), for ortho, para, and meta1H positions around the pyridine ring were ∼(−)7, ∼(−)6, and ∼(−)3, respectively—in good agreement with simple peak-height measurements. However, these results embody only a slight improvement over what was achieved with the original HET-SABRE catalysts.59

Figure 4.

(a) 1H NMR spectrum from a mixture containing d6-ethanol solvent, the PVP polymer comb catalyst particles (PVPCs), and the (fully protonated) pyridine substrate thermally polarized at 9.4 T following activation with pH2 bubbling. (b) 1H NMR spectrum of the sample in (a) obtained after PVPC activation but with pH2 bubbling occurring at high field, acquired immediately after cessation of pH2 gas bubbling; for the most part, no high-field (in situ) SABRE effect was observed. (c) 1H (ex situ) HET-SABRE NMR spectrum obtained from the same sample, acquired immediately after 30 s of pH2 bubbling at low field (∼100 G) and rapid transfer of the sample into the NMR magnet. All spectra shown were acquired with a single scan (90° pulse). Peaks at about δ ≈1.1, ≈3.6, and ≈5.2 ppm are from residual protons from the deuterated ethanol solvent. The peak at ≈4.5 ppm is from (ortho-)hydrogen (oH2) gas. The inset shows the expected hexacoordinate structure of the activated catalytic moiety, exchanging with pH2 and the substrate pyridine (Py).

Results for the NP catalysts are shown in Figure 5. Here, the same sample from Figures 3b,d was studied, comprising ∼8 mg of TiO2/PMAA core–shell NP catalysts (corresponding to an estimated 0.0031 mmol of the Ir complex) suspended in 400 μL d6-ethanol along with 0.05 mmol of pyridine substrate. A number of thermally polarized 1H NMR spectra were acquired over the course of the experiment, including one following catalyst activation at high field (Figure 5a). Ex situ bubbling of pH2 (∼95% fraction) for 30 s followed by rapid manual transfer of the sample into the magnet gave rise to significant enhancements of the substrate 1H NMR signals (Figure 5c), with ε values of ∼(−)18, ∼(−)17, and ∼(−)7 estimated for ortho, para, and meta positions, respectively. Subsequent acquisition following 300 s of ex situ pH2 bubbling yielded larger enhancements of ∼(−)26, ∼(−)39, and ∼(−)11 compared to a thermally polarized scan taken afterward (bubbling does lead to some loss of liquid from the sample, necessitating a fresh thermal scan). As before with the studies using PVPCs, reduced shim quality made precise quantification of the enhancements challenging, but the values reported are again in good agreement with estimates based on simple peak-height analyses performed on peaks with similar line widths. Moreover, on the SIUC setup (with a pH2 bubbler that is limited in operation to near-ambient pressure), typical enhancements obtained with homogeneous catalysts rarely exceed ∼50–100-fold (also reflecting nonoptimal conditions with respect to concentrations, temperature, magnetic field, etc.). Thus, it is likely that significantly larger HET-SABRE enhancements can be achieved in the future not only by improving the experimental methodology but also through further optimization of the catalyst syntheses and structures. Enhancement values for both nanoscale catalysts tested here are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 5.

(a) 1H NMR spectrum from a mixture containing d6-ethanol solvent, the nanoSABRE catalyst particles (NPCs), and the (fully protonated) pyridine substrate thermally polarized at 9.4 T following activation with pH2 bubbling. (b) 1H NMR spectrum of the sample in (a) obtained after nanoSABRE catalyst activation but with pH2 bubbling occurring at high field, acquired immediately after cessation of pH2 gas bubbling; no high-field (in situ) SABRE effect was observed. (c) 1H (ex situ) HET-SABRE NMR spectrum obtained from the same sample, acquired immediately after 30 s of pH2 bubbling at low field (∼100 G) and rapid transfer of the sample into the NMR magnet. All spectra shown were acquired with a single scan (90° pulse). Peaks at about δ ≈1.1, ≈3.6, and ≈5.2 ppm are from residual protons from the deuterated ethanol solvent. The peak at ≈4.5 ppm is from oH2. The inset shows the expected hexacoordinate structure of the activated catalytic moiety, exchanging with pH2 and the substrate (Py).

Table 1. Polarization Enhancement (ε) Values for Three Aromatic Proton Sites of Pyridine (Figures 4, 5, and 7) Achieved via Conventional (ex Situ, Low-Field) SABRE and Detected by High-Resolution 1H NMR Spectroscopy Using the Nanoscale Catalysts (PVPCs or NPCs) in d6-Ethanol or d4-Methanola.

| catalyst | ε(Ho) | ε(Hp) | ε(Hm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PVPCs (30 s) | –7 | –6 | –3 |

| NPCs (30 s) | –18 | –17 | –7 |

| NPCs (300 s) | –26 | –39 | –11 |

| NPCs recycled | –11 | –9.7 | –3.2 |

Reported ε values are calculated from spectral integrals and are approximate, with estimated uncertainties of ∼10%. Numbers in parentheses are pH2 bubbling times.

Similar to the results with the PVPCs in Figure 4, no clear, qualitative signatures of high-field SABRE could be discerned from the spectra for the NP catalysts (Figure 5b). As first reported in ref (46), the standard homogeneous Ir-IMes SABRE catalyst can give rise to 1H NMR enhancements at high field, contrary to original expectation. The high-field SABRE effect appears to result from nuclear spin cross-relaxation with HP hydride spins45 similar to the SPINOE,74,75 as opposed to the conventional SABRE effect, which relies on scalar couplings to efficiently transfer spin order when the external field becomes low enough to match the frequency differences between substrate and hydride resonances to the magnitudes of relevant scalar couplings. While high-field SABRE enhancements are generally much smaller than those achieved via conventional low-field SABRE, significantly larger in situ SABRE enhancements can be observed at high field with the application of recently reported pulse sequences.46,48 In any case, we note that we have observed high-field SABRE effects with nearly every homogeneous catalyst variant that we have studied (including 4AP-cat),45,46,59,73 with the one notable exception being a variant that exhibited only dispersive hydride signals76 (and hence no net hyperpolarized z-magnetization in the hydride spin bath). Thus, the virtual absence of high-field SABRE effects with the nanoscale catalysts reported here manifests a significant difference in NMR properties from their (much smaller) homogeneous counterparts. This absence of high-field SABRE effects may reflect intrinsically reduced efficiencies in the nuclear spin cross-relaxation mechanism (e.g., because of altered correlation times) as well as mass-transport limitations expected for heterogeneous/nanoscale catalysts; for example, the possible observation of a weak negative peak in Figure 4b (likely for an ortho-H resonance of bound pyridine substrate molecules) for the PVPCs may indicate that high-field SABRE is indeed occurring to at least some degree, but at far too inefficient of a rate (particularly when additionally limited by the ligand exchange rates and macroscale transport of substrates within the sample) for it to overcome the headwinds of the thermal (Boltzmann/equilibrium) polarization processes.

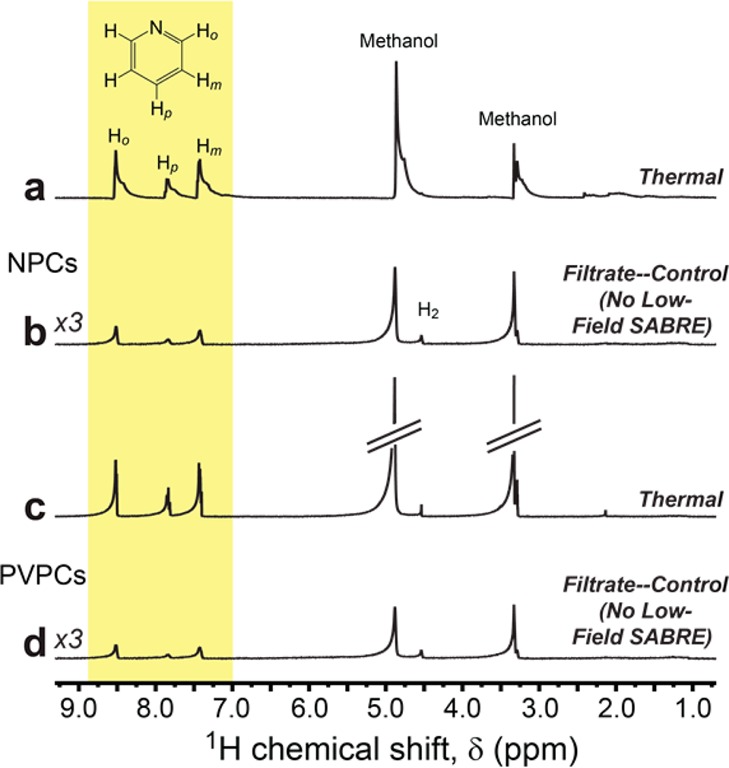

Other evidence supports that the SABRE enhancements in Figures 4 and 5 are endowed by intact nanoscale catalysts and are not, say, from freely floating catalyst molecules leached from the polymers or nanoparticles. Following SABRE experiments, the solutions respectively containing the polymer comb catalysts and nanoparticle catalysts were each centrifuged with ultrafilters (see Experimental Approach and Supporting Information). Small portions of the filtrate solutions were tested by AAS, and the presence of Ir was not observed within the detection limits of the instrument. The remaining filtrate solutions were dried and reconstituted in 400 μL of a different solvent (d4-methanol) with ∼0.05 mmol of added pyridine substrate. As shown in Figure 6, no SABRE enhancement was observed in either reconstituted filtrate solution following 30 s pH2 bubbling (∼93% pH2 fraction) within the ∼100 G fringe field and rapid sample transfer to the NMR magnet for detection.

Figure 6.

Control 1H NMR spectra obtained from filtrate liquids obtained from reconstituted solutions of NPCs (b) and PVPCs (d) in d4-methanol; corresponding thermal spectra of the filtrate solutions are in (a) and (c). Both samples contained added pyridine substrate, and pH2 bubbling was performed ex situ (∼100 G), as was done in Figures 4 and 5; note the absence of SABRE enhancement in (b) and (d). The reduced signal strengths in (b) and (d) are the result of rapid transfer of the samples into the NMR magnet; given the apparent absence of SABRE enhancement from within the filtrate samples, more time is required for the spins to fully (thermally) magnetize in the external field, as occurred for the acquisition of the corresponding thermally polarized reference spectra in (a) and (c). Peaks at about δ ≈3.3 and ≈4.9 ppm are from residual protons from the deuterated methanol solvent; the peak at ≈4.5 ppm is from oH2.

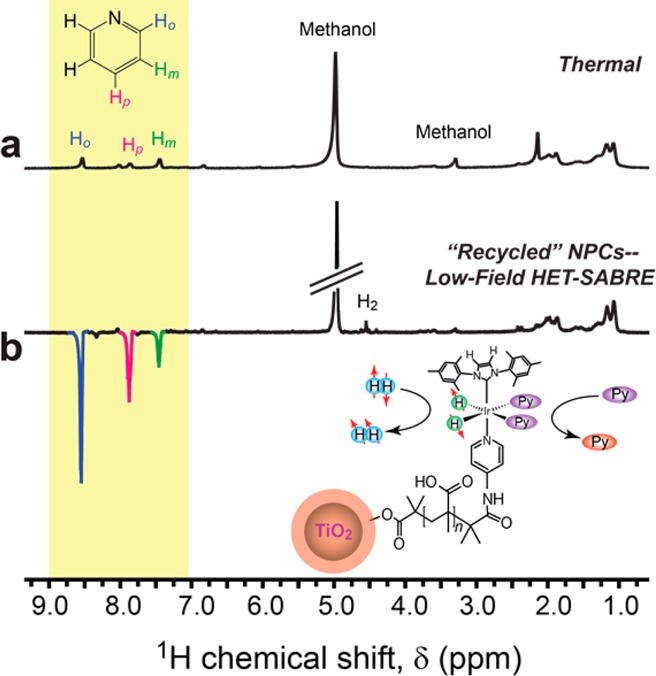

Although the present nanoscale catalysts were not designed with facile separation or rapid HP-agent recovery in mind (but rather for investigating different design approaches for enhancing HET-SABRE), the above experiment afforded an opportunity to investigate the potential of recovery and recycling/reuse of such supported SABRE catalysts. For example, following the above SABRE experiments and ultrafilter centrifugation, a portion of the NPCs were carefully recovered from the ultrafilter cartridge, dried, and resuspended in 0.4 mL of an alternative solvent (again, d4-methanol) with ∼0.05 mmol of added pyridine substrate. Following low-field bubbling with pH2 (∼85% pH2 fraction) for 30 s and rapid transfer to high field, HET-SABRE enhancements of the substrate 1H NMR signals are clearly observed from the recycled and reconstituted NPCs (Figure 7). Although these enhancements (up to ∼(−)11-fold) are smaller than what was achieved in the first experiments with these catalysts—likely because of reduced catalyst concentration and slightly reduced pH2 fraction (in addition to any loss of catalytic activity suffered during the recovery/reconstitution process)—these results demonstrate the feasibility of recovering and recycling supported SABRE catalysts for reuse in NMR applications.

Figure 7.

(a) 1H NMR spectrum from a mixture containing d4-methanol solvent, “recycled” NPCs, and the pyridine substrate thermally polarized at 9.4 T. (b) Corresponding 1H (ex situ) HET-SABRE NMR spectrum obtained from the same sample of “recycled” NPCs, acquired immediately after 30 s of pH2 bubbling at low field (∼100 G) and rapid transfer of the sample into the NMR magnet. All spectra shown were acquired with a single scan (90° pulse). Peaks at about δ ≈3.3 and ≈4.9 ppm are from residual protons from the deuterated methanol solvent. The peak at ≈4.5 ppm is from oH2; broad peaks ∼1–2 ppm are primarily from the PMAA of the catalyst particles.

4. Conclusion

In summary, we have reported the preparation and demonstration of two novel nanoscale catalysts—respectively composed of PVP polymer combs and TiO2/PMAA core–shell nanoparticles, tethered to Ir-based catalytic moieties—for 1H NMR enhancement by SABRE at the interface between truly heterogeneous and homogeneous conditions. Enhancements of up to ∼7- and ∼40-fold were observed for the PVP comb catalysts and NP catalysts, respectively. The latter value represents nearly an order-of-magnitude improvement over previous results obtained with microscale HET-SABRE catalysts and corresponds to a 1H polarization of ∼0.13% at 9.4 T and 300 K. The feasibility of recovery and recycling of such catalysts to achieve SABRE enhancement was also demonstrated. Taken together, these results demonstrate the utility of rational design for improving NMR enhancements via supported SABRE catalysts. Future efforts will concern further improvements in polarization enhancements (including fundamental studies of processes governing HET-SABRE enhancement under different conditions) as well as efforts to allow preparation of pure, physiologically relevant HP substrates in aqueous or biologically compatible solutions for a wide range of biomedical spectroscopic and imaging applications.

Acknowledgments

B.M.G. and F.S. thank Elizabeth Porter (UNC) and Greg Zimay (SIUC) for assistance. We thank for funding support NSF CHE-1416268, NIH 1R21EB018014-01A1, and 2R15EB007074-02, DoD CDMRP Breast Cancer Program Era of Hope Award W81XWH-12-1-0159/BC112431, and SIUC OSPA. F.S. gratefully acknowledges support from a doctoral fellowship of the Graduate School of SIUC. B.M.G. is a member of the SIUC Materials Technology Center.

Supporting Information Available

Additional information concerning catalyst synthesis, characterization, sample preparation, and experimental methods. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Nikolaou P.; Goodson B. M.; Chekmenev E. Y. NMR Hyperpolarization Techniques for Biomedicine. Chem.—Eur. J. 2015, 21, 3156–3166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. H.; Okuno Y.; Cavagnero S. Sensitivity Enhancement in Solution NMR: Emerging Ideas and New Frontiers. J. Magn. Reson. 2014, 241, 18–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn L. T.; Akbey Ü.. Hyperpolarization Methods in NMR Spectroscopy; Springer: Berlin, 2013; Vol. 338. [Google Scholar]

- Green R. A.; Adams R. W.; Duckett S. B.; Mewis R. E.; Williamson D. C.; Green G. G. The Theory and Practice of Hyperpolarization in Magnetic Resonance Using Para Hydrogen. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 2012, 67, 1–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodson B. M. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance of Laser-Polarized Noble Gases in Molecules, Materials, and Organisms. J. Magn. Reson. 2002, 155, 157–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurhanewicz J.; Vigneron D. B.; Brindle K.; Chekmenev E. Y.; Comment A.; Cunningham C. H.; DeBerardinis R. J.; Green G. G.; Leach M. O.; Rajan S. S.; et al. Analysis of Cancer Metabolism by Imaging Hyperpolarized Nuclei: Prospects for Translation to Clinical Research. Neoplasia 2011, 13, 81–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson S. J.; Kurhanewicz J.; Vigneron D. B.; Larson P. E.; Harzstark A. L.; Ferrone M.; van Criekinge M.; Chang J. W.; Bok R.; Park I. Metabolic Imaging of Patients with Prostate Cancer Using Hyperpolarized Pyruvate. Sci. Transl. Med. 2013, 5, 108–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jänsch H.; Gerhard P.; Koch M. 129Xe on Ir (111): NMR Study of Xenon on a Metal Single Crystal Surface. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004, 101, 13715–13719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maly T.; Cui D.; Griffin R. G.; Miller A.-F. 1H Dynamic Nuclear Polarization Based on an Endogenous Radical. J. Phys. Chem. B 2012, 116, 7055–7065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landon C.; Berthault P.; Vovelle F.; Desvaux H. Magnetization Transfer from Laser-Polarized Xenon to Protons Located in the Hydrophobic Cavity of the Wheat Nonspecific Lipid Transfer Protein. Protein Sci. 2001, 10, 762–770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai L.; Mair R.; Rosen M.; Patz S.; Walsworth R. An Open-Access, Very-Low-Field MRI System for Posture-Dependent He Human Lung Imaging. J. Magn. Reson. 2008, 193, 274–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey A. M.; Kovtunov K. V.; Barskiy D. A.; Koptyug I. V.; Shchepin R. V.; Waddell K. W.; He P.; Groome K. A.; Best Q. A.; Shi F.; et al. High-Resolution Low-Field Molecular Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Hyperpolarized Liquids. Anal. Chem. 2014, 86, 9042–9049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telkki V.-V.; Zhivonitko V. V.; Ahola S.; Kovtunov K. V.; Jokisaari J.; Koptyug I. V. Microfluidic Gas-Flow Imaging Utilizing Parahydrogen-Induced Polarization and Remote-Detection NMR. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 8363–8366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X.; Graziani D.; Pines A. Hyperpolarized Xenon NMR and MRI Signal Amplification by Gas Extraction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009, 106, 16903–16906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker T. G.; Happer W. Spin-Exchange Optical Pumping of Noble-Gas Nuclei. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1997, 69, 629–642. [Google Scholar]

- Tycko R. NMR at Low and Ultralow Temperatures. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 46, 1923–1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yesinowski J. P.Solid-State NMR of Inorganic Semiconductors. In Solid State NMR; Springer: Berlin, 2012; pp 229–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardenkjær-Larsen J. H.; Fridlund B.; Gram A.; Hansson G.; Hansson L.; Lerche M. H.; Servin R.; Thaning M.; Golman K. Increase in Signal-to-Noise Ratio of >10,000 Times in Liquid-State NMR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003, 100, 10158–10163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weis V.; Bennati M.; Rosay M.; Bryant J.; Griffin R. High-Field DNP and ENDOR with a Novel Multiple-Frequency Resonance Structure. J. Magn. Reson. 1999, 140, 293–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingwood M. D.; Siaw T. A.; Sailasuta N.; Ross B. D.; Bhattacharya P.; Han S. Continuous Flow Overhauser Dynamic Nuclear Polarization of Water in the Fringe Field of a Clinical Magnetic Resonance Imaging System for Authentic Image Contrast. J. Magn. Reson. 2010, 205, 247–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward H. R. Chemically Induced Dynamic Nuclear Polarization (CIDNP). I. Phenomenon, Examples, and Applications. Acc. Chem. Res. 1972, 5, 18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Mok K. H.; Hore P. J. Photo-CIDNP NMR Methods for Studying Protein Folding. Methods 2004, 34, 75–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodson B. M. Applications of Optical Pumping and Polarization Techniques in NMR: I. Optical Nuclear Polarization in Molecular Crystals. Annu. Rep. NMR Spectrosc. 2005, 55, 299–323. [Google Scholar]

- Tateishi K.; Negoro M.; Nishida S.; Kagawa A.; Morita Y.; Kitagawa M. Room Temperature Hyperpolarization of Nuclear Spins in Bulk. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014, 111, 7527–7530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers C. R.; Weitekamp D. P. Transformation of Symmetrization Order to Nuclear-Spin Magnetization by Chemical-Reaction and Nuclear-Magnetic-Resonance. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1986, 57, 2645–2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenschmid T. C.; Kirss R. U.; Deutsch P. P.; Hommeltoft S. I.; Eisenberg R.; Bargon J.; Lawler R. G.; Balch A. L. Para Hydrogen Induced Polarization in Hydrogenation Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987, 109, 8089–8091. [Google Scholar]

- Salnikov O. G.; Kovtunov K. V.; Barskiy D. A.; Khudorozhkov A. K.; Inozemtseva E. A.; Prosvirin I. P.; Bukhtiyarov V. I.; Koptyug I. V. Evaluation of the Mechanism of Heterogeneous Hydrogenation of α, β-Unsaturated Carbonyl Compounds via Pairwise Hydrogen Addition. ACS Catal. 2014, 4, 2022–2028. [Google Scholar]

- Bowers C. R.; Weitekamp D. P. Para-Hydrogen and Synthesis Allow Dramatically Enhanced Nuclear Alignment. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987, 109, 5541–5542. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya P.; Harris K.; Lin A. P.; Mansson M.; Norton V. A.; Perman W. H.; Weitekamp D. P.; Ross B. D. Ultra-Fast Three Dimensional Imaging of Hyperpolarized 13C in Vivo. Magn. Reson. Mater. Phys. 2005, 18, 245–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman M.; Johannesson H.; Axelsson O.; Karlsson M. Hyperpolarization of C-13 Through Order Transfer from Parahydrogen: A New Contrast Agent for MRI. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2005, 23, 153–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day S. E.; Kettunen M. I.; Gallagher F. A.; Hu D. E.; Lerche M.; Wolber J.; Golman K.; Ardenkjaer-Larsen J. H.; Brindle K. M. Detecting Tumor Response to Treatment Using Hyperpolarized C-13 Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Spectroscopy. Nat. Med. 2007, 13, 1382–1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chekmenev E. Y.; Hovener J.; Norton V. A.; Harris K.; Batchelder L. S.; Bhattacharya P.; Ross B. D.; Weitekamp D. P. PASADENA Hyperpolarization of Succinic Acid for MRI and NMR Spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 4212–4213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai C.; Coffey A. M.; Shchepin R. V.; Chekmenev E. Y.; Waddell K. W. Efficient Transformation of Parahydrogen Spin Order into Heteronuclear Magnetization. J. Phys. Chem. B 2013, 117, 1219–1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman M.; Jóhannesson H. Conversion of a Proton Pair Para Order into C-13 Polarization by RF Irradiation, for Use in MRI. C. R. Phys. 2005, 6, 575–581. [Google Scholar]

- Haake M.; Natterer J.; Bargon J. Efficient NMR Pulse Sequences to Transfer the Parahydrogen-Induced Polarization to Heteronuclei. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 8688–8691. [Google Scholar]

- Adams R. W.; Aguilar J. A.; Atkinson K. D.; Cowley M. J.; Elliott P. I. P.; Duckett S. B.; Green G. G. R.; Khazal I. G.; Lopez-Serrano J.; Williamson D. C. Reversible Interactions with Para-Hydrogen Enhance NMR Sensitivity by Polarization Transfer. Science 2009, 323, 1708–1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowley M. J.; Adams R. W.; Atkinson K. D.; Cockett M. C.; Duckett S. B.; Green G. G.; Lohman J. A.; Kerssebaum R.; Kilgour D.; Mewis R. E. Iridium N-Heterocyclic Carbene Complexes as Efficient Catalysts for Magnetization Transfer from Para-Hydrogen. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 6134–6137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes A. J.; Rayner P.; Cowley M. J.; Green G. G.; Whitwood A. C.; Duckett S. B. The Reaction of an Iridium PNP Complex with Parahydrogen Facilitates Polarisation Transfer Without Chemical Change. Dalton Trans. 2014, 1077–1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Weerdenburg B. J.; Glöggler S.; Eshuis N.; Engwerda A. T.; Smits J. M.; de Gelder R.; Appelt S.; Wymenga S. S.; Tessari M.; Feiters M. C. Ligand Effects of NHC–Iridium Catalysts for Signal Amplification by Reversible Exchange (SABRE). Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 7388–7390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glöggler S.; Müller R.; Colell J.; Emondts M.; Dabrowski M.; Blümich B.; Appelt S. Para-Hydrogen Induced Polarization of Amino Acids, Peptides and Deuterium–Hydrogen Gas. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011, 13, 13759–13764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barskiy D. A.; Kovtunov K. V.; Koptyug I. V.; He P.; Groome K. A.; Best Q. A.; Shi F.; Goodson B. M.; Shchepin R. V.; Truong M. L.; et al. In Situ and Ex Situ Low-Field NMR Spectroscopy and MRI Endowed by SABRE Hyperpolarization. ChemPhysChem 2014, 15, 4100–4107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng H.; Xu J.; Gillen J.; McMahon M. T.; Artemov D.; Tyburn J.-M.; Lohman J. A.; Mewis R. E.; Atkinson K. D.; Green G. G.; et al. Optimization of SABRE for Polarization of the Tuberculosis Drugs Pyrazinamide and Isoniazid. J. Magn. Reson. 2013, 237, 73–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hövener J.-B.; Schwaderlapp N.; Borowiak R.; Lickert T.; Duckett S. B.; Mewis R. E.; Adams R. W.; Burns M. J.; Highton L. A.; Green G. G. Toward Biocompatible Nuclear Hyperpolarization Using Signal Amplification by Reversible Exchange: Quantitative in Situ Spectroscopy and High-Field Imaging. Anal. Chem. 2014, 86, 1767–1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng H.; Xu J.; McMahon M. T.; Lohman J. A.; van Zijl P. C. Achieving 1% NMR Polarization in Water in Less Than 1 min. Using SABRE. J. Magn. Reson. 2014, 246, 119–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truong M. L.; Shi F.; He P.; Yuan B.; Plunkett K. N.; Coffey A. M.; Shchepin R. V.; Barskiy D. A.; Kovtunov K. V.; Koptyug I. V.; et al. Irreversible Catalyst Activation Enables Hyperpolarization and Water Solubility for NMR Signal Amplification by Reversible Exchange. J. Phys. Chem. B 2014, 118, 13882–13889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barskiy D. A.; Kovtunov K. V.; Koptyug I. V.; He P.; Groome K. A.; Best Q. A.; Shi F.; Goodson B. M.; Shchepin R. V.; Coffey A. M.; et al. The Feasibility of Formation and Kinetics of NMR Signal Amplification by Reversible Exchange (SABRE) at High Magnetic Field (9.4 T). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 3322–3325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pravdivtsev A. N.; Yurkovskaya A. V.; Vieth H.-M.; Ivanov K. L.; Kaptein R. Level Anti-Crossings Are a Key Factor for Understanding Para-Hydrogen-Induced Hyperpolarization in SABRE Experiments. ChemPhysChem 2013, 3327–3331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theis T.; Truong M. L.; Coffey A. M.; Chekmenev E. Y.; Warren W. S. LIGHT-SABRE Enables Efficient in-Magnet Catalytic Hyperpolarization. J. Magn. Reson. 2014, 248, 23–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theis T.; Truong M. L.; Coffey A. M.; Waddell K. W.; Shi F.; Goodson B. M.; Warren W. S.; Chekmenev E. Y. Microtesla SABRE Enables 10% Nitrogen-15 Nuclear Spin Polarization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 1404–1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaou P.; Coffey A. M.; Walkup L. L.; Gust B. M.; Whiting N.; Newton H.; Barcus S.; Muradyan I.; Dabaghyan M.; Moroz G. D.; et al. Near-Unity Nuclear Polarization with an ’Open-Source’ 129Xe Hyperpolarizer for NMR and MRI. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013, 110, 14150–14155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driehuys B.; Cates G.; Miron E.; Sauer K.; Walter D.; Happer W. High-Volume Production of Laser-Polarized 129Xe. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1996, 69, 1668–1670. [Google Scholar]

- Ruset I. C.; Ketel S.; Hersman F. W. Optical Pumping System Design for Large Production of Hyperpolarized. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 96, 1–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingwood M. D.; Siaw T. A.; Sailasuta N.; Abulseoud O. A.; Chan H. R.; Ross B. D.; Bhattacharya P.; Han S. Hyperpolarized Water as an MR Imaging Contrast Agent: Feasibility of in Vivo Imaging in a Rat Model. Radiology 2012, 265, 418–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koptyug I. V.; Zhivonitko V. V.; Kovtunov K. V. New Perspectives for Parahydrogen-Induced Polarization in Liquid Phase Heterogeneous Hydrogenation: An Aqueous Phase and ALTADENA Study. Phys. Chem. 2010, 11, 3086–3088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovtunov K. V.; Beck I. E.; Bukhtiyarov V. I.; Koptyug I. V. Observation of Parahydrogen-Induced Polarization in Heterogeneous Hydrogenation on Supported Metal Catalysts. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 1492–1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovtunov K. V.; Beck I. E.; Zhivonitko V. V.; Barskiy D. A.; Bukhtiyarov V. I.; Koptyug I. V. Heterogenation Addition of H2 to Double and Triple Bonds over Supported Pd Catalysts: A Parahydrogen-Induced Polarization Technique Study. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2012, 14, 11008–11014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovtunov K. V.; Barskiy D. A.; Shchepin R. V.; Coffey A. M.; Waddell K. W.; Koptyug I. V.; Chekmenev E. Y. Demonstration of Heterogeneous Parahydrogen Induced Polarization Using Hyperpolarized Agent Migration from Dissolved Rh (I) Complex to Gas Phase. Anal. Chem. 2014, 86, 6192–6196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reineri F.; Viale A.; Ellena S.; Boi T.; Daniele V.; Gobetto R.; Aime S. Use of Labile Precursors for the Generation of Hyperpolarized Molecules from Hydrogenation with Parahydrogen and Aqueous-Phase Extraction. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 7350–7353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi F.; Coffey A. M.; Waddell K. W.; Chekmenev E. Y.; Goodson B. M. Heterogeneous Solution NMR Signal Amplification by Reversible Exchange. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 126, 7625–7628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuenya B. R. Synthesis and Catalytic Properties of Metal Nanoparticles: Size, Shape, Support, Composition, and Oxidation State Effects. Thin Solid Films 2010, 518, 3127–3150. [Google Scholar]

- Mane R. B.; Hengne A. M.; Ghalwadkar A. A.; Vijayanand S.; Mohite P. H.; Potdar H. S.; Rode C. V. Cu: Al Nano Catalyst for Selective Hydrogenolysis of Glycerol to 1, 2-Propanediol. Catal. Lett. 2010, 135, 141–147. [Google Scholar]

- Jin S.; Lukowski M. A.; Daniel A. S.; English C. R.; Meng F.; Forticaux A.; Hamers R. Highly Active Hydrogen Evolution Catalysis from Metallic WS2 Nanosheets. Energy Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 2608–2613. [Google Scholar]

- Lu W.; Wei Z.; Gu Z.-Y.; Liu T.-F.; Park J.; Park J.; Tian J.; Zhang M.; Zhang Q.; Gentle T. III Tuning the Structure and Function of Metal–Organic Frameworks via Linker Design. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 5561–5593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rioux R.; Song H.; Hoefelmeyer J.; Yang P.; Somorjai G. High-Surface-Area Catalyst Design: Synthesis, Characterization, and Reaction Studies of Platinum Nanoparticles in Mesoporous SBA-15 Silica. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 2192–2202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenaglia A.; Brun P.; Waegell B. Nickel-Catalyzed Oligomerization of Functionalized Conjugated Dienes. J. Organomet. Chem. 1985, 285, 343–357. [Google Scholar]

- Zi G. Asymmetric Hydroamination/Cyclization Catalyzed by Group 4 Metal Complexes with Chiral Biaryl-Based Ligands. J. Organomet. Chem. 2011, 696, 68–75. [Google Scholar]

- Pohlki F.; Doye S. The Catalytic Hydroamination of Alkynes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2003, 32, 104–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez-Serrano L. D.; Owens B. T.; Buriak J. M. The Search for New Hydrogenation Catalyst Motifs Based on N-Heterocyclic Carbene Ligands. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2006, 359, 2786–2797. [Google Scholar]

- Dücker E. B.; Kuhn L. T.; Münnemann K.; Griesinger C. Similarity of SABRE Field Dependence in Chemically Different Substrates. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2012, 214, 159–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kownacki I.; Kubicki M.; Szubert K.; Marciniec B. Synthesis, Structure and Catalytic Activity of the First Iridium (I) Siloxide Versus Chloride Complexes with 1, 3-Mesitylimidazolin-2-ylidene Ligand. J. Organomet. Chem. 2008, 693, 321–328. [Google Scholar]

- Torres O.; Martin M.; Sola E. Labile N-Heterocyclic Carbene Complexes of Iridium. Organometallics 2009, 28, 863–870. [Google Scholar]

- Feng B.; Coffey A. M.; Colon R. D.; Chekmenev E. Y.; Waddell K. W. A Pulsed Injection Parahydrogen Generator and Techniques for Quantifying Enrichment. J. Magn. Reson. 2012, 214, 258–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi F.; Porter E.; Truong M. L.; Coffey A. M.; Waddell K. W.; Chekmenev E. Y.; Goodson B. M., Interplay of Catalyst Structure and Temperature for NMR Signal Amplification by Reversible Exchange. In preparation.

- Navon G.; Song Y. Q.; Room T.; Appelt S.; Taylor R. E.; Pines A. Enhancement of Solution NMR and MRI with Laser-Polarized Xenon. Science 1996, 271, 1848–1851. [Google Scholar]

- Song Y. Q. Spin Polarization-Induced Nuclear Overhauser Effect: An Application of Spin-Polarized Xenon and Helium. Concepts Magn. Reson. 2000, 12, 6–20. [Google Scholar]

- He P.; Best Q. A.; Groome K. A.; Coffey A. M.; Truong M. L.; Waddell K. W.; Chekmenev E. Y.; Goodson B. M.. A Water-Soluble SABRE Catalyst for NMR/MRI Enhancement. In 55th Exptl. Nucl. Magn. Reson Conf., Boston, MA, March 23–28, 2014. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.