Abstract

Prediction errors are central to modern learning theories. While brain regions contributing to reward prediction errors have been uncovered, the sources of aversive prediction errors remain largely unknown. Here we used probabilistic and deterministic reinforcement procedures, followed by extinction, to examine the contribution of the dorsal raphe nucleus to negative, aversive prediction errors in Pavlovian fear. Rats with dorsal raphe lesions were able to acquire fear and reduce fear to a non-reinforced, deterministic cue. However, dorsal raphe lesions impaired the reduction of fear to a probabilistic cue and fear extinction to a deterministic cue – both of which involve the use of negative prediction errors. The results point to an integral role for the dorsal raphe nucleus in negative prediction error signaling in Pavlovian fear.

Keywords: rat, conditioned suppression, omission, learning

Introduction

Modern learning theories emphasize the role of prediction errors (Rescorla & Wagner, 1972; Esber & Haselgrove, 2011). While prediction errors have been extensively studied in situations of reward (Waelti et al., 2001; Fiorillo et al., 2003; Roesch et al., 2007), fewer studies have examined their role in Pavlovian fear (Iordanova, 2009). This can be directly assessed with probabilistic reinforcement. For example, a cue predicting shock on 50% of trials generates a shock prediction of 0.5. On reinforced trials the shock predicted (0.5) is less than the shock received (1.0), resulting in a ‘positive’ prediction error. This positive prediction error (PPE) can increase both shock prediction and cued fear on subsequent trials. By contrast, on non-reinforced trials the shock predicted (0.5) is more than the shock received (0.0), resulting in a ‘negative’ prediction error (NPE). This NPE can act to reduce both shock prediction and cued fear on subsequent trials. Employing prediction errors allows for appropriate levels of fear to be demonstrated to probabilistically reinforced Pavlovian cues.

Aversive prediction errors have been hypothesized to originate in serotonergic neurons of the dorsal raphe nucleus (DRN) (Daw et al., 2002). In addition to serotonin, the DRN contains many non-serotonergic neurons including: dopaminergic, GABAergic, glutamatergic and peptidergic populations (Michelsen et al., 2007). Both non-serotonergic and serotonergic neurons densely project to the basolateral and central amygdala (Vertes, 1991; Halberstadt & Balaban, 2008), areas essential to Pavlovian fear (Campeau & Davis, 1995; Killcross et al., 1997; Goosens & Maren, 2001; Lee et al., 2005; McDannald, 2010; McDannald & Galarce, 2011). Non-serotonergic populations are likely to work in concert with (Challis et al., 2013) and independent of serotonergic neurons (Bouwknecht et al., 2007), making the entire DRN a candidate source of prediction errors. Outside of the DRN, prediction error signaling in Pavlovian fear has been reported in the ventrolateral periaqueductal grey (vlPAG). Interestingly, vlPAG neurons only reflect aversive PPEs (Johansen et al., 2010; McNally et al., 2011). This leaves open the question what brain region contributes to aversive NPEs.

Here we tested the hypothesis that the DRN as a whole is necessary to reduce Pavlovian fear via aversive NPEs. To do this we gave rats neurotoxic DRN lesions and assessed fear to a probabilistic cue, and two deterministic cues: one always reinforced with shock and one never reinforced with shock. If the DRN is selectively necessary to reduce Pavlovian fear via NPEs, DRN lesions should result in higher levels of fear to the probabilistic cue compared to Controls. By contrast DRN lesions should leave intact fear to the reinforced, deterministic cue and the reduction of generalized fear to the non-reinforced, deterministic cue. This is because fear reduction to the deterministic cue can be achieved by resolving the sensory differences between the cues – a process that does not require the use of a NPE. To further test this hypothesis we examined fear extinction with a focus on the reinforced deterministic cue. In extinction, shock omission on deterministic trials would be expected to generate a NPE. If the DRN is necessary to reduce fear through aversive NPEs, DRN lesions should result in slower extinction to the deterministic cue. By using probabilistic reinforcement and extinction procedures we are able to directly assess a role for the DRN in two separate settings, both of which require the use of aversive NPEs to reduce Pavlovian fear.

Methods and Materials

Subjects

Subjects were 14 male, experimentally naïve Long Evans rats (Charles River Laboratories), approximately 300 g at the beginning of the experiment. Seven rats served as DRN lesions, four rats surgical controls and three rats as non-surgical controls. Rats were individually housed in and maintained at 90% of their ad libitum weights; water was freely available at all times. All protocols were approved by the National Institute on Drug Abuse Animal Care and Use Committee and experiments were carried out in accordance with the Guidelines laid down by the NIH in the US regarding the care and use of animals for experimental procedure.

Apparatus

The apparatus consisted of two individual chambers with aluminum front and back walls, clear acrylic sides and top, and a grid floor. Each grid floor bar was electrically connected to an aversive shock generator (Med Associates, St. Albans, VT). An external food cup and a central nose poke opening, equipped with infrared photocells were present on one wall. Auditory stimuli were presented through two speakers mounted on the ceiling.

Surgical procedures

All surgeries were performed under aseptic conditions using isoflurane gas anesthesia and a stereotaxic frame (Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA, USA). Neurotoxic DRN lesions (n=7) were made using infusions of quinolinic acid (QA; 20 μg/μl; Sigma) in phosphate vehicle. Infusion volume and location was: 0.5 μl: AP, −8.0; ML, 0.0 mm; DV, −6.2 mm. For surgical controls (n=4) the needle was lowered to: AP, −8.0; ML, 0.0 mm; DV, −4.2 mm; but no infusion was given. All rats that underwent surgery received a single subcutaneous injection of 0.01 mg/kg carprofen for amelioration of pain. Three rats served as non-surgical controls.

Behavioral procedures

Nose poke acquisition

A summary of behavioral procedures can be found in Figure 1. Rats were shaped to nose poke for pellet delivery in the experimental chamber using a fixed ratio schedule in which one nose poke yielded one pellet. Shaping sessions lasted 30 minutes or until ~50 nose pokes. Over the next three days rats were placed on variable interval (VI) schedules in which nose pokes were reinforced on average every 30 s (day 1) or 60 s (days 2–3). Throughout the remainder of training nose pokes were reinforced on a VI-60 schedule, independent of any Pavlovian contingencies.

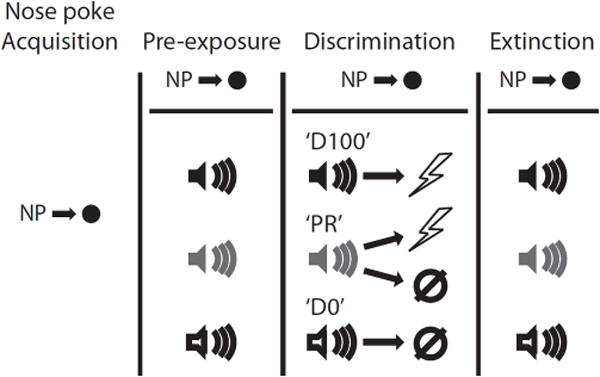

Figure 1. Summary of behavioral procedures.

A summary of behavioral procedures is shown. Briefly, each rat was trained to nose poke for pellet delivery which was maintained for the entirety of pre-exposure, discrimination and extinction. Following pre-exposure to the three auditory cues each rat received discrimination sessions in which one cue deterministically predicted shock occurrence ‘D100’, a second deterministically predicted shock absence ‘D0’, and a third probabilistically predicted occurrence or omission ‘PR’. In extinction all cues were presented in the absence of shock.

Pre-exposure

Rats were pre-exposed to the three auditory cues to be used in the Pavlovian discrimination procedure in two separate sessions. Each 70-min session consisted of eight presentations of each cue (24 total presentations) with a mean inter-trial interval (ITI) of 2.5 min. For this and all subsequent sessions, order of trial type presentation was randomly determined by the behavioral program and differed each session.

Discrimination

Over the next eight sessions each rat underwent Pavlovian discrimination training. Each 96-min session consisted of 32 trials, mean ITI of 2.5 min. All auditory cues were 10 s in duration. On the eight ‘D100’ trials, a foot shock (0.5 ms, 0.5 mA) was delivered 1 s following cue offset. On 8 ‘D0’ trials, a cue was presented but no shock delivered. On 8 ’PR’ trials, the cue was followed by shock but on the remaining 8 ’PR’ trials no shock was delivered – resulting in 50% reinforcement. Previous studies have shown that probabilistic cues support higher-than-expected levels of fear (Erlich et al., 2012); meaning a 50% reinforced cue will suppress instrumental actions by more than 50%. To further probe shock omission sensitivity we reduced the probability of shock on PR trials from 50% to 38% (6 reinforced and 10 non-reinforced trials per session). This study was performed in two replications, with rats in the first replication (3 DRN-lesions and 3 Non-Surgical Controls) receiving eight 38% sessions and rats in the second replication (4 DRN-lesions and 4 Surgical Controls) receiving four sessions. A complete breakdown of the specific training and group numbers for each replication can be found in Table 1.

Table 1. Experimental Information.

The experiment consisted of three total groups: Non-Surgical Controls, Surgical Controls and neurotoxic DRN lesions. The first replication consisted of 3 Non-Surgical Controls and 3 DRN lesions while the second replication consisted of 4 Surgical Controls and 4 DRN lesions. ANOVA found no differences between the two Control groups and they were combined for all analyses. Rats in both replications received eight sessions of 50% shock reinforcement. Owing to circumstances beyond the authors’ control, rats in the first replication received eight sessions of 38% reinforcement while rats in the second replication received four sessions of 38% reinforcement.

| Group | Replication | n | #PR50 | #PR38 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Surgical Control | 1 | 3 | 8 | 8 |

| Surgical Control | 2 | 4 | 8 | 4 |

| DRN Lesion | 1 | 3 | 8 | 8 |

| DRN Lesion | 2 | 4 | 8 | 4 |

Extinction

Extinction sessions were given on the next four days. A brief reminder of the initial discrimination was given 15 minutes prior to the first extinction session. This session consisted of 16 total trials: 4 – ‘D100’ trials, 3 –‘PR’ reinforced trials, 5 – ‘PR’ non-reinforced trials and 4 – ‘D0’ trials; all occurring exactly as described above. In extinction the auditory cues were presented eight times each in random order and in the absence of shock. ANOVAs for extinction found no significant effects of the number of discrimination sessions, thus rats from the two replications were collapsed into single Control and DRN-lesioned groups.

Histological procedures

Rats were anesthetized with an overdose of isoflurane and perfused intracardially with 0.9% saline. Brains were collected and stored in 4% (v/v) paraformaldehyde and 10% (w/v) sucrose. 40 μm sections were collected on a sliding microtome and Nissl stained to verify lesion placement.

Statistical Analysis

Data were acquired using Med Associates Med-PC IV software. Raw data were processed in Matlab to extract nose poke rates during two periods: baseline (20 s prior to cue onset) and cue (entire 10 s). A suppression ratio was calculated: (baseline − cue) / (baseline + cue). A ratio of ‘1’ indicated complete suppression of nose poking during the cue and a high level of fear. A ratio of ‘0’ indicated no suppression and no fear (Pickens et al., 2009). Suppression ratios were then analyzed with ANCOVA, with baseline nose poke rate as a covariate, and t test in Statistica. A significance level of p<0.05 was used.

Results

Histological Results

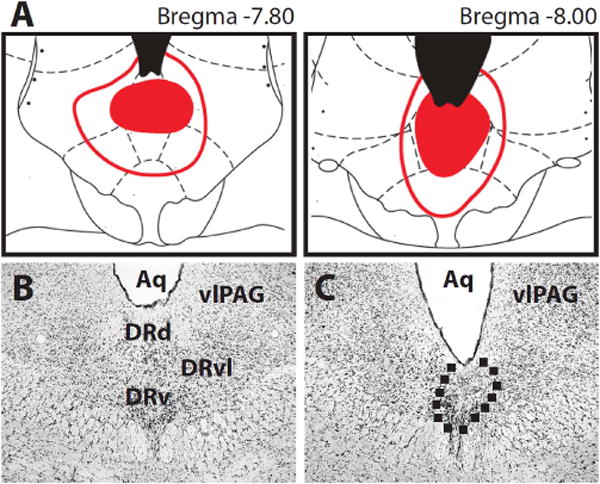

We quantified neurotoxic damage (cell loss and gliosis) to the dorsal (DRd), ventral (DRv) and lateral subdivisions (DRvl) of the DRN as well as the adjacent vlPAG. Mean ± sem percent damage for each region: DRd − 94.3 ± 3.8, DRv − 40.0 ± 10.2, DRvl − 11.5 ± 4.3 and vlPAG − 1.4 ± 1.0. ANOVA revealed significant differences in percent damage between the regions (F3,18 = 63.92, p < 0.01). Post-hoc comparisons with Tukey’s HSD found significant differences in damage as follows: DRd > DRv > DRvl = vlPAG. The minimal/maximal lesion extent for DRN-lesioned rats is indicated in Figure 2A (Paxinos & Watson, 1996). Surgical control lesions showed no evidence of damage. Representative photomicrographs from a surgical control rat (Figure 2B) and DRN-lesioned rat (Figure 2C) are shown.

Figure 2. Histology.

Rats were first randomly assigned to the Control or DRN lesion condition. (A) Sections 7.80 mm (left) and 8.00 mm (right) posterior to bregma are shown. Minimal lesion extent is indicated by the filled red areas. Maximal lesion extent is indicated by red outlines. Representative photomicrographs of (B) surgical Control and (C) DRN lesion are shown. The area outlined contains gliosis and cell loss – evidence of neurotoxic damage. Abbreviations: Aq – aqueduct, DRd – dorsal raphe dorsal, DRv – dorsal raphe ventral, DRd – dorsal raphe ventrolateral, and vlPAG – ventrolateral periaqueductal grey.

Nose poke performance

Control and DRN-lesioned rats readily acquired nose poking and by the extinction sessions rats had reach high baseline rates: Con − 57.7 ± 9.2, DRN − 66.6 ± 20.7. ANOVAs for baseline nose poke rates during pre-exposure and discrimination sessions (1–13) or reminder and extinction sessions (1–5) revealed no effect of or interaction with group (Fs < 1, ps > 0.4). Variations in baseline nose poke rates did not contribute to differences in suppression ratios between Control and DRN-lesioned rats (see ANCOVAs below).

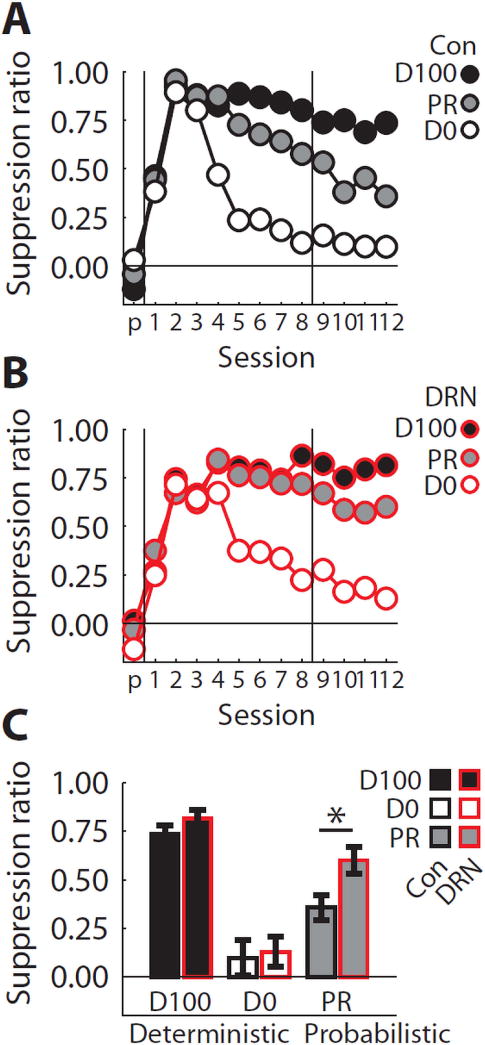

Fear discrimination

In pre-exposure sessions neither Control nor DRN-lesioned rats demonstrated fear to any of the to-be-conditioned cues. Control and DRN-lesioned rats initially acquired high levels of fear to all cues. These levels were maintained to the ‘D100’ cue. DRN-lesioned rats showed a reduction of fear to the ‘D0’ cue that was equivalent to Controls but were impaired in their reduction of fear to the ‘PR’ cue (Figure 3A,B). This difference was especially apparent when the probability of shock shifted from 50% to 38% (second vertical line in 3A,B). In support, ANCOVA for suppression ratios [covariate: mean baseline nose poke rate on sessions 9–12, factors: group (control vs. lesion), trial type (4) and session (1–13)] found significant effects of trial type, session, the trial type × session interaction (Fs > 2.0, ps < 0.05) but most importantly, the trial type × session × group interaction (F36,360 = 1.54, p < 0.05). Consistent with this interaction, t tests comparing Control and DRN suppression ratios to each cue on the twelfth discrimination session (shown in Figure 3C) found only a significant difference to the ‘PR’ cue (p = 0.015).

Figure 3. Fear in discrimination.

(A) Mean suppression ratios to the ‘D100’ (black fill), ‘PR’ (grey fill) and ‘D0’ cues (white fill) are shown for Control (black outlines) rats on the final pre-exposure session (‘p’ on x axis) and the 12 discrimination sessions. The horizontal line indicates a suppression ratio of 0.0, meaning no fear is observed to the cue. The first vertical line separates the last pre-exposure session from the first discrimination session. The second vertical line marks the transition from 50% shock reinforcement of the ‘PR’ cue to 38% reinforcement. (B) Conditioned suppression data from DRN-lesioned (red outlines) rats plotted exactly as in (A). (C) Mean ± SEM suppression ratios for discrimination session 12 are shown for each group and cue. Meaning of colors maintained from (A & B). Asterisk indicates a significant, between-subject t test result comparing Control and DRN-lesioned rats. *p<0.05.

Fear extinction

A brief discrimination reminder was given just prior to the first extinction session. As was found at the end of discrimination, DRN-lesioned rats showed greater fear to the ‘PR’ cue than did Controls. This was true even when only the first reminder trial was analyzed. In support, ANCOVA for suppression ratios [covariate: mean baseline nose poke rate on sessions 1–5 (reminder + 4 extinction sessions), factors: group (control vs. lesion) and cue (3)] found significant effects of cue and group (Fs > 5, ps < 0.05), but most critically a group × cue interaction (F2,22 = 6.18, p <0.01). Like in discrimination, a t test comparing ‘PR’ suppression ratios found a significant difference between Control (0.43 ± 0.08) and DRN-lesioned rats (0.68 ± 0.06).

Because Control and DRN-lesioned rats showed different levels of fear to the ‘PR’ cue in reminder, and our hypothesis was specific to the ‘D100’ cue, we focused our extinction analysis on the ‘D100’ cue. Visual inspection of the extinction data (Figure 4A, left) suggests that while Control and DRN-lesioned rats showed equivalent levels of fear in reminder, DRN-lesions were slower to extinguish ‘D100’ fear compared to Controls. This is supported by ANCOVA for suppression ratios [covariate: nose poke baseline, factors: group (control vs. lesion) and sessions 1–5 (reminder + 4 extinction sessions)] which found a significant effect of session (F1,11 = 4.11, p < 0.05) but critically, a session × group interaction (F4,44 = 2.84, p < 0.05). DRN-lesioned rats showed significantly higher levels of fear in the first two extinction sessions compared to Controls (t test, p < 0.05; Figure 4A, right).

Figure 4. Fear in extinction.

(A, left) Mean suppression ratios to the ‘D100’ cue are shown for Control (black outlines) and DRN-lesioned rats (red lines) on the reminder session (‘r’ on x axis) and the four extinction sessions. The horizontal line indicates a suppression ratio of 0.0, meaning no fear is observed to the cue. The vertical line separates the reminder session from the first extinction session. (A, right) Mean ± SEM suppression ratios to the ‘D100’ cue for extinction sessions 1 and 2 are shown for Control and DRN-lesioned rats. Meaning of colors maintained from (A). Asterisk indicates a significant, between-subject t test result comparing Control and DRN-lesioned rats. (B) The correlation between mean suppression ratio to the ‘PR’ cue on discrimination session 8 (x axis) and to the ‘D100’ cue on the first two extinction sessions is plotted for Control (Con, black) and DRN-lesioned rats (DRN, red). Each marker represents an individual. Trend line, R2 and p-value of correlation are shown. (C) The correlation between mean suppression ratio to the ‘PR’ cue on discrimination session 12 (x axis) and to the ‘D100’ cue on the first two extinction sessions is plotted. Formatting same as (B). *p<0.05.

An identical ANCOVA for ‘PR’ suppression ratios returned the same effect of session and session × group interaction (Fs > 3, ps < 0.05), but also a significant effect of group (F1,11 = 12.92, p < 0.05). However, the ‘PR’ extinction deficit in DRN-lesioned rats is difficult to interpret given that ‘PR’ fear in reminder was already higher than Controls.

Relationship between fear to the probabilistic cue and extinction

So far the effects of DRN lesions have aligned with our hypothesis. However, if the DRN is contributing to NPEs in discrimination and extinction, then fear to these separate cues at different times should be related. To directly examine this we plotted the mean suppression ratio to the ‘PR’ cue on the eighth (Figure 4B) or twelfth discrimination session (Figure 4C) versus the mean suppression ratio to the ‘D100’ on the first two extinction sessions for all rats (as shown in Figure 4A). A robust, significant relationship was found for both comparisons (Figure 4B; R2 = 0.45, p < 0.05; Figure 4C; R2 = 0.56, p < 0.01). Rats that showed greater fear to the probabilistic cue in discrimination also showed higher levels of fear to the deterministic cue in extinction. The positive relationship was not spurious; the same significant correlation was found when comparing any of the following combination of sessions: mean of discrimination sessions 8–12, 8 only, or 12 only vs. the first, second or both first and second extinction sessions (all R2 > 0.3, ps < 0.05).

One could argue the significant correlation between fear to the probabilistic and deterministic cues found across all rats is not valid, as we have already shown fear to be higher to both cues in DRN-lesioned rats. Thus, one would expect to see two separate clusters for Control and DRN rats on the scatter plot, forcing a correlation to arise. If there is truly a correlation between probabilistic fear in discrimination and deterministic fear in extinction this should be apparent when only the Controls are analyzed. This is because the DRN is intact in Control rats, allowing it to contribute to fear reduction in both settings. In support, analysis restricted to PR fear on discrimination session 8 (n = 7; R2 = 0.72, p < 0.01) or session 12 (n = 7; R2 = 0.67, p < 0.05) with ‘D100’ fear in extinction found significant correlations for both. Such robust correlations point to a common role for the DRN in fear reduction via NPEs to the probabilistic cue in discrimination and the deterministic cue in extinction.

Discussion

In the current experiment, DRN-lesioned rats demonstrated greater fear to a probabilistic cue compared with Controls and were also slower to extinguish fear to a deterministic cue. The level of fear demonstrated to a probabilistic cue reflects a balance between opposing prediction errors; with PPEs working to increase Pavlovian fear and NPEs working to reduce fear. One interpretation of our finding is that DRN-lesioned enhanced the efficacy of PPEs. If this was the case, DRN-lesioned rats should have more rapidly acquired fear and/or shown higher terminal levels of fear to the reinforced, deterministic cue. This did not occur despite the fact that ceiling levels of fear were not reached in either group at the end of discrimination training. Moreover, if DRN lesions enhanced PPE signaling it is unclear how this would work to slow fear extinction. PPEs should be almost entirely absent in extinction sessions.

A more parsimonious account is that DRN lesions impaired rats’ ability to reduce Pavlovian fear via aversive NPEs. Because all cues initially acquired high levels of fear, emphasis was placed fear reduction over the course of discrimination. NPE signaling was intact in Control rats, allowing them to appropriately reduce fear to the probabilistic cue. DRN lesions diminished NPE signaling, but left PPE signaling intact, biasing DRN-lesioned rats towards greater fear to the probabilistic cue. By contrast, the DRN was not necessary to reduce fear when this could be achieved through resolving the sensory differences between cues, as was the case for the non-reinforced, deterministic cue. A specific role for the DRN in NPE is supported by the results from extinction. In Control rats, shock omission following the deterministic cue would result in a NPE, which would work to reduce fear to this cue on subsequent trials. In DRN-lesioned rats the NPE was diminished, resulting in slower extinction. Perhaps most striking was that the level of fear demonstrated to the probabilistic cue at the end of discrimination was tightly linked to the level of fear demonstrated in the early extinctions sessions. The common deficit in reducing fear to the probabilistic cue in discrimination and to the deterministic cue in extinction, coupled with the strong correlation between levels of fear in these two different settings, points to a central role for the DRN in reducing Pavlovian fear through aversive NPEs.

Our proposed role for the DRN in aversive NPEs fits well in a neural circuit for predictive fear learning (McNally et al., 2011), in which the basolateral and central amygdala nuclei work in concert to provide a prediction to the vlPAG (McNally & Cole, 2006; Cole & McNally, 2007). VlPAG neurons calculate an aversive PPE by comparing the central amygdala prediction signal and a spinal shock receipt signal. The vlPAG-derived PPE is then fed back to the amygdala to update the shock prediction and display of fear. The DRN also receives projections from the central amygdala (Hermann et al., 1997) and in turn directly projects to the basolateral and central amygdala (Vertes, 1991; Halberstadt & Balaban, 2008). A DRN NPE signal could be sent directly to the basolateral and central amygdala to modify subsequent shock prediction and reduce the display of Pavlovian fear. Of course, the DRN may not generate a NPE de novo, but may instead serve as an obligatory relay for a NPE generated elsewhere. In either case the DRN is critical to its use.

Further supporting the specificity of our findings, the DRN does not directly encode positive or negative reward prediction errors (Nakamura et al., 2008; Miyazaki et al., 2011), which have been repeatedly demonstrated in dopaminergic neurons of the ventral tegmental area (VTA) (Waelti et al., 2001; Fiorillo et al., 2003; Roesch et al., 2007). However, the strong, anatomical connectivity between the DRN and VTA (Beckstead et al., 1979; Vertes, 1991) would allow DRN-based, aversive NPEs to influence the expression of VTA-based reward prediction errors and vice versa.

The present results are consistent with, and add to, an existing neural circuitry for fear extinction learning. Studies of fear extinction have repeatedly found an important role for infralimbic, prefrontal cortex (ilPFC) in the storage of fear memories (Milad & Quirk, 2002; Sierra-Mercado et al., 2011). The ilPFC enjoys reciprocal connectivity with the DRN and studies of behavioral control have found ample evidence of a functional projection from the ilPFC to the DRN (Amat et al. 2005). While speculative, it is possible that in Pavlovian fear extinction; the DRN provides the ilPFC with a negative prediction error during omission of an expected shock. The ilPFC would use this NPE to build up a fear extinction memory and convey this new, inhibitory memory to the DRN, amygdalar nuclei and other regions on future presentations of the cue. Such ilPFC memory could work to reduce DRN NPE signaling with continued Pavlovian fear extinction.

The current experiment was designed to test a negative prediction error hypothesis of DRN function. However, because so little is known of the DRN contribution to Pavlovian fear it may also play roles unrelated to NPE signaling. For example, the DRN may be recruited when there is uncertainty about future events or when there is internal competition between fearful states and rewarding states, as in conditioned suppression. Future work on the DRN in Pavlovian fear will be needed to specify its contribution.

Here we have demonstrated a critical role for the DRN in generating or using negative prediction errors to reduce Pavlovian fear. These results provide a novel player that may be important for understanding disorders of persistent fear, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). An inability to generate and/or use NPEs to reduce fear may be a central deficit in PTSD. For example, in experimental settings PTSD patients can typically acquire Pavlovian fear (Milad et al., 2008) but are impaired in fear extinction (Milad et al., 2009) and inhibition (Jovanovic et al., 2012). Common to both is the need to reduce fear through the generation and use of NPEs. Our present results demonstrate a role for the DRN in this form of prediction error, providing a potential brain target for therapies aimed at improving fear extinction and inhibition.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Antonello Bonci for NIDA-IRP support, Dr. Yavin Shaham and Dr. Donna Calu for laboratory space, Dr. Peter Holland for discussion of the results, Dr. Thomas Stalnaker for extensive comments on early drafts, Dr. Bruce Hope and Klil Babin for microphotograph assistance, Dr. Charles Pickens for programming assistance and Aaron Mirenzi for histological assistance. This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program at the National Institute on Drug Abuse and DA034010 (MAM).

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures

We report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Amat J, Baratta MV, Paul E, Bland ST, Watkins LR, Maier SF. Medial prefrontal cortex determines how stressor controllability affects behavior and dorsal raphe nucleus. Nature Neuroscience. 2005;8:365–371. doi: 10.1038/nn1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckstead RM, Domesick VB, Nauta WJH. Efferent Connections of the Substantia Nigra and Ventral Tegmental Area in the Rat. Brain Research. 1979;175:191–217. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)91001-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouwknecht JA, Spiga F, Staub DR, Hale MW, Shekhar A, Lowry CA. Differential effects of exposure to low-light or high-light open-field on anxiety-related behaviors: Relationship to c-Fos expression in serotonergic and non-serotonergic neurons in the dorsal raphe nucleus. Brain Research Bulletin. 2007;72:32–43. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campeau S, Davis M. Involvement of the central nucleus and basolateral complex of the amygdala in fear conditioning measured with fear-potentiated startle in rats trained concurrently with auditory and visual conditioned stimuli. J Neurosci. 1995;15:2301–2311. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-03-02301.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Challis C, Boulden J, Veerakumar A, Espallergues J, Vassoler FM, Pierce RC, Beck SG, Berton O. Raphe GABAergic Neurons Mediate the Acquisition of Avoidance after Social Defeat. Journal of Neuroscience. 2013;33:13978–U13384. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2383-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole S, McNally GP. Temporal-difference prediction errors and Pavlovian fear conditioning: Role of NMDA and opioid receptors. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2007;121:1043–1052. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.121.5.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daw ND, Kakade S, Dayan P. Opponent interactions between serotonin and dopamine. Neural Networks. 2002;15:603–616. doi: 10.1016/s0893-6080(02)00052-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erlich JC, Bush DEA, LeDoux JE. The role of the lateral amygdala in the retrieval and maintenance of fear-memories formed by repeated probabilistic reinforcement. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 2012;6 doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2012.00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esber GR, Haselgrove M. Reconciling the influence of predictiveness and uncertainty on stimulus salience: a model of attention in associative learning. Proceedings of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences. 2011;278:2553–2561. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2011.0836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorillo CD, Tobler PN, Schultz W. Discrete coding of reward probability and uncertainty by dopamine neurons. Science. 2003;299:1898–1902. doi: 10.1126/science.1077349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goosens KA, Maren S. Contextual and auditory fear conditioning are mediated by the lateral, basal, and central amygdaloid nuclei in rats. Learning & Memory. 2001;8:148–155. doi: 10.1101/lm.37601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halberstadt AL, Balaban CD. Selective anterograde tracing of nonserotonergic projections from dorsal raphe nucleus to the basal forebrain and extended amygdala. Journal of Chemical Neuroanatomy. 2008;35:317–325. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann DM, Luppi PH, Peyron C, Hinckel P, Jouvet M. Afferent projections to the rat nuclei raphe magnus, raphe pallidus and reticularis gigantocellularis pars alpha demonstrated by iontophoretic application of choleratoxin (subunit b) Journal of Chemical Neuroanatomy. 1997;13:1–21. doi: 10.1016/s0891-0618(97)00019-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iordanova MD. Dopaminergic modulation of appetitive and aversive predictive learning. Rev Neurosci. 2009;20:383–404. doi: 10.1515/revneuro.2009.20.5-6.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen JP, Tarpley JW, LeDoux JE, Blair HT. Neural substrates for expectation-modulated fear learning in the amygdala and periaqueductal gray. Nature Neuroscience. 2010;13:979–U102. doi: 10.1038/nn.2594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jovanovic T, Kazama A, Bachevalier J, Davis M. Impaired safety signal learning may be a biomarker of PTSD. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62:695–704. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killcross S, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. Different types of fear-conditioned behaviour mediated by separate nuclei within amygdala. Nature. 1997;388:377–380. doi: 10.1038/41097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JL, Dickinson A, Everitt BJ. Conditioned suppression and freezing as measures of aversive Pavlovian conditioning: effects of discrete amygdala lesions and overtraining. Behavioral Brain Research. 2005;159:221–233. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDannald MA. Contributions of the amygdala central nucleus and ventrolateral periaqueductal grey to freezing and instrumental suppression in Pavlovian fear conditioning. Behavioural Brain Research. 2010;211:111–117. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDannald MA, Galarce EM. Measuring Pavlovian fear with conditioned freezing and conditioned suppression reveals different roles for the basolateral amygdala. Brain Research. 2011;1374:82–89. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.12.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally GP, Cole S. Opioid receptors in the midbrain periaqueductal gray regulate prediction errors during Pavlovian fear conditioning. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2006;120:313–323. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.120.2.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally GP, Johansen JP, Blair HT. Placing prediction into the fear circuit. Trends in Neurosciences. 2011;34:283–292. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelsen KA, Schmitz C, Steinbusch HWM. The dorsal raphe nucleus – From silver stainings to a role in depression. Brain Research Reviews. 2007;55:329–342. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milad MR, Orr SP, Lasko NB, Chang YC, Rauch SL, Pitman RK. Presence and acquired origin of reduced recall for fear extinction in PTSD: Results of a twin study. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2008;42:515–520. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milad MR, Pitman RK, Ellis CB, Gold AL, Shin LM, Lasko NB, Zeidan MA, Handwerger K, Orr SP, Rauch SL. Neurobiological basis of failure to recall extinction memory in posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66:1075–1082. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milad MR, Quirk GJ. Neurons in medial prefrontal cortex signal memory for fear extinction. Nature. 2002;420:70–74. doi: 10.1038/nature01138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki K, Miyazaki KW, Doya K. Activation of Dorsal Raphe Serotonin Neurons Underlies Waiting for Delayed Rewards. Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;31:469–479. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3714-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura K, Matsumoto M, Hikosaka O. Reward-dependent modulation of neuronal activity in the primate dorsal raphe nucleus. Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;28:5331–5343. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0021-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Academic Press; San Diego: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Pickens CL, Golden SA, Adams-Deutsch T, Nair SG, Shaham Y. Long-lasting incubation of conditioned fear in rats. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:881–886. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rescorla RA, Wagner AR. A theory of Pavlovian conditioning: Variations in the effectiveness of reinforcement and nonreinforcement. In: AH B, WF P, editors. Classical Conditioning II: Current Research and Theory. Appleton Century Crofts; New York: 1972. pp. 64–99. [Google Scholar]

- Roesch MR, Calu DJ, Schoenbaum G. Dopamine neurons encode the better option in rats deciding between differently delayed or sized rewards. Nature Neuroscience. 2007;10:1615–1624. doi: 10.1038/nn2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sierra-Mercado D, Padilla-Coreano N, Quirk GJ. Dissociable roles of prelimbic and infralimbic cortices, ventral hippocampus, and basolateral amygdala in the expression and extinction of conditioned fear. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:529–538. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vertes RP. A PHA-L analysis of ascending projections of the dorsal raphe nucleus in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1991;313:643–668. doi: 10.1002/cne.903130409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waelti P, Dickinson A, Schultz W. Dopamine responses comply with basic assumptions of formal learning theory. Nature. 2001;412:43–48. doi: 10.1038/35083500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]